ABSTRACT

How can and should post-conflict cities be rebuilt after traumatic violence and forced displacement? Five years following Mosul’s liberation from the extremist reign of Islamic State, controversy surrounds attempts to revive the city’s rich cultural heritage and pluralistic past. This paper examines Mosul’s ongoing reconstruction initiatives, shaped by competing memory narratives and actors (local and international) vying for the right to reimagine the city. It explores how violent urbicide has ruptured Moslawi's identity and belonging, contributing to fragmented memories of the past and diverging aspirations for the future. Drawing on diverse perspectives from inhabitants within the city and its periphery, the article suggests that urban recovery must balance heritage restoration as a means to reviving traditions of co-existence while still acknowledging the traumatic memories of destruction and erasure. The opportunities for ‘building back better’ must navigate fine margins between local sensibilities, international support and the illusive search for social recovery.

Introduction

The deliberate destruction of Mosul’s cultural heritage by the Islamic State (IS) between 2014 and 2017– 47 structures including shrines, mosques, churches and heritage housesFootnote1 – was both a demonstration of radical Salafist iconoclasm and a strategic commitment to urbicide,Footnote2 the purposeful targeting of the city’s plural history and the precarious co-existence of its diverse communities. The challenge of reversing such processes and rebuilding Mosul as a vibrant cosmopolitan city invariably leads to questions about funding, political will, displacement, social re-integration, and the key role of memory in post-conflict recovery. What type of new Mosul is being imagined and what is selectively forgotten? How can the traumatic past be navigated without embedding social grievances or romanticising tolerance discourses? This paper examines Mosul’s ongoing reconstruction initiatives, shaped by competing memory narratives and actors both local and international vying for the right to reimagine Mosul. It observes how violent urbicide has ruptured Moslawi's identity and belonging, contributing to fragmented memories of the past and diverging aspirations for the future. Drawing on a plurality of perspectives from inhabitants within the city and its periphery, the article suggests that urban recovery must balance heritage restoration as a means to reviving traditions of co-existence while still acknowledging the traumatic memories of destruction and erasure.

This paper contributes to a growing literature around memory and post-war reconstruction with a particular focus on how psychosocial recovery requires the intersection of urban and communal interventions.Footnote3 This paper offers three key findings. First, Mosul’s reconstruction process cannot be solely based on a popular romanticism and nostalgia for the city’s cosmopolitan past that does not reflect critically on the urban fractures and communal suspicions that enabled and empowered the Islamist insurgency and IS control of the city. There must be more opportunities and spaces for minority voices (Yezidis, Shabaks, Kurds, Christians and Turkmen) to be heard and reflected in the city’s urban rehabilitation and collective memory. Second, large-scale reconstruction and memorialisation projects of key cultural and religious sites (i.e. al-Nouri Mosque) must also be supplemented by support and acknowledgement of local sites imbued with memories of violence, loss and suffering. These traumatic everyday spaces provide reminders of persecution and death and continue to impact on future peacebuilding within Mosul and Iraq. Jaspar Chalcraft differentiates between ‘Charismatic heritage’ – the highly visible symbolic icons which often align with international donor values but may be critiqued as ‘monumental virtue-signalling’ and ‘Careful heritage’ – difficult, ambiguous and often intangible forms of heritage which ‘eschews clear narratives in favour of trying to open up the past and make it work for communities traumatised by conflict’.Footnote4 Third, Mosul must avoid the sectarian splintering and exploitation of Iraqi cultural heritage in which religious sites are being reimagined and reconstructed to serve sectarian muhasasa politics.Footnote5 This will require international actors (such as UNESCO) to support and build up the capacity of the Iraqi national heritage institutions and involve all segments of Mosul’s urban society and its hinterland, including displaced and exiled communities.

Methods and outline

The city of Mosul provides a timely and original frame, as a site of international focus and heritage funding aimed at supporting Iraqi national recovery and reversing IS’ destructive legacy. The research is based on interviews with over 40 individuals from Mosul and Nineveh, including activists, scholars, religious leaders, tribal sheikhs, politicians, community representatives, as well as ordinary citizens across religion, ethnic, gender, and class divides. Interviews were conducted in Arabic, during February–December 2022, mostly online with some in-person interviews conducted by the authors in Baghdad. A diverse sample was achieved by relying on the authors’ Iraqi research networks and through snowballing techniques. All interviewees provided informed consent and have been anonymised to protect identities and pseudonyms used to reflect the diversity of the sample. The authors have also integrated secondary source data as reflected in policy reports, news articles, academic journals, as well as social media in Arabic and English.

The paper first provides a theoretical discussion on the interplay between memorialisation and reconstruction, followed by a specific focus on the historical context of Mosul’s post-war re-imagining. The subsequent sections draw on the interview material to explore Mosul’s dominant memory narratives and then the urban sites and spaces in which diverse actors compete to shape Mosul’s development trajectory. In the words of one Mosul civil activist, ‘Whoever is controlling the narrative of the [City’s] history is controlling the past and the future’.Footnote6

‘Building back better’: memory and post-conflict reconstruction

All post-conflict and divided societies confront the need to establish a delicate balance between forgetting and remembering. It is crucial that memorialisation processes do not function as empty rhetoric commemorating the dead, while losing sight of the reasons and the context for past tragedies and obscuring contemporary challenges.Footnote7

The role of memory in post-conflict reconstruction and recovery is increasingly recognised by scholars and practitioners alike, yet with limited consensus around what makes good practice. The delicate balancing of learning from and moving beyond the past is often complicated by fragile socio-political contexts and competing ‘regimes of memory’ that vie for interpretative power and legitimating authority.Footnote8 In the case of Mosul, memory debates are imperilled by unresolved Iraqi national dilemmas – the legacy of IS, Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), sectarian politics – and the pragmatic challenges of urban rehabilitation. How should one prioritise and manage the rebuilding of a devastated city from which one million citizens were displaced and of which 60% to 70% of its infrastructure was destroyed, requiring an estimated $1.1 billion to rebuild the western side of the city?Footnote9

In Mosul, traumatic memories remain etched on streets and broken walls, embedded within everyday stories of death, survival, and loss. The fragile war-scarred city is replete with ‘traumascapes’,Footnote10 fusing wounded spaces and conflict narratives, connecting people to past violence and perpetuating ongoing prejudices and communal mistrust. The stalled reconstruction process stirs prescient questions concerning Mosul’s recovery: Can urbicide be reversed through strategic planning and to what extent can sites of traumatic violence (buildings, memorials) become spaces for collective recovery?

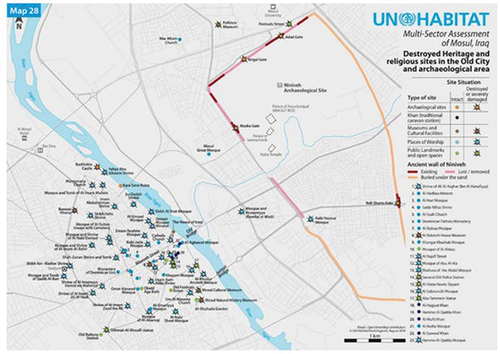

The concept of urbicide, defined as the deliberate killing of the city, has been increasingly applied to the strategic targeting of cities and architecture (homes, cultural heritage and infrastructure) through war to create mass displacement, ethnic cleansing and homogenous enclaves.Footnote11 IS’s deliberate killing and forced expulsion of Mosul’s religious and ethnic minority communities and destruction of diverse religious sites and monuments − 37 Muslim mosques, tombs and shrines; 35 Christian churches and monasteries; 22 Yazidi shrines in Bashiqa and Bahzany and 10 Shabak shrines in Nineveh plain () – certainly fits within this rubric. IS’s actions were an unequivocal attempt to crush Mosul’s plural history and produce an exclusive subjugated Islamist order.Footnote12 Urbicide not only captures the genocidal intent of such violence but also its rural/urban dimensionFootnote13; some observe this as the ‘revenge of the countryside’ or an attack on a cosmopolitan elite by marginalised rural (riif) communities. Footnote14 This is a recurring theme of many Moslawi narratives: the post-2003 influx of rural IDPs and migrants from the Nineveh plains, Salaheddin and Anbar contributed to and exacerbated the divides within Mosul as these vulnerable newcomers settled in the poorest parts of the city and were susceptible to Islamist recruitment and later supported IS in taking over the city in June 2014. As one interviewee explained ‘Extremism and inner conflict is not rooted in the society of Mosul … Extremism and fundamentalism occurred mostly in the periphery (villages and countryside surrounding Mosul) and those who joined IS came from there’.Footnote15

Figure 1. Mosul’s destroyed religious and cultural heritage in the old city, UN-HABITAT multi-sector assessment, 2017.

Despite growing research on the effects and legacy of urbicide in cities such as Sarajevo, Jerusalem, Beirut and Aleppo, little attention has been directed towards how this process can be reversed. This is not merely a question of urban reconstruction but how to restore multiculturalism in post-war contexts of displacement and erasure. Scholars have rightly highlighted the dangers of ‘destructive reconstruction’ processes, which can lead to property seizure, restrictive urban planning laws, selective erasure and neoliberal interventions, all of which ‘radically transform the social, cultural and spatial fabrics in war-torn cities’.Footnote16 Another problematic approach may be termed ‘heritage as healing’, with international donors prioritising ambitious restoration projects of religious buildings and historic sites as a means to facilitate social reconciliation. This has been critiqued for favouring ‘world heritage’ over local residential and economic needs, reifying divisions rather than reuniting communities, exacerbating class divides (for instance Soldiere’s Downtown Beirut) and consolidating sectarian narratives and competitive territorial claims.Footnote17 Bruce Stanley explains that the dynamic politicisation of memory in urban post-war recovery reminds us that ‘the how of reconstruction and who recovers which aspects of the city and by what mechanisms, are shaped by the temporal and spatial aspects of power and marginalisation’.Footnote18 In the case of Mosul, international visions for resurrecting the city’s past must equally address the present concerns and needs of its diverse citizens and their ‘right to the city’.Footnote19

The second post-war memory challenge facing Mosul is how to navigate traumatic urban sites of violence. Numerous comparative studies testify to the persistence and political malleability of physical traces of past conflict: the explicit, such as graves, martyrs’ posters, murals and local inscriptions, and the implicit including derelict homes, graffiti, bullet-scarred walls and checkpoints.Footnote20 These visual reminders help to spatialise social identities and shape narratives of victimhood and suffering, linking killings and massacres to unresolved grievances and divisions.Footnote21 In a sense, past trauma is inscribed onto contemporary lives, reproducing feelings of guilt, shame and injustice and legitimising ongoing hostilities.Footnote22 Frazer Hay’s Internal Organization for Migration (IOM) report on the impact and legacy of violent memory in Mosul and Tal Afar warns that everyday trauma sites remain potential ‘timebombs’ that cannot be ignored, silenced or subsumed under large-scale urban development plans. He explains that such an approach dangerously ‘underestimates the impact a community’s smouldering memories of religious and ethnic violence can have on future social cohesion, and reinforces the notion that reconstruction brings about reconciliation’.Footnote23 According to Hay, Mosul would benefit from a comprehensive mapping of such trauma sites, which would provide a more balanced approach to memorialisation that acknowledges, records and authenticates ‘past atrocities’ and empowers local inhabitants to share their stories. The political sensitivity and timing of such an initiative is undeniably problematic but Iraq in general and Mosul in particular must find ways of memorialising their collective suffering or accept the inevitable proliferation and splintering of memorials and sectarian narratives. Before delving deeper into the data analysis, the authors will provide a brief historic context for Mosul’s post-war re-imagining, highlighting key episodes which contribute to the city’s turbulent trajectory.

Mosul: a cosmopolitan and contested city

Translated as ‘linking point’, Mosul carries the historic legacy of a junction city, serving as an important economic and cultural hub on the ancient Silk Road. The target of consecutive imperial conquests, the city has witnessed as many violent encounters as it has done competing empires: Assyrian, Umayyad and Rashidun Caliphate, Ottoman Villayet and the capital of Nineveh province as part of the Iraqi state. Contested boundaries and substate loyalties have resulted in geopolitical struggles – the 1926 Mosul question mediated by the League of NationsFootnote24 – and popular uprisings (Mosul’s al-Sahwaf revolt, 1959) leading to violent state repression. Nevertheless, Mosul has remained multicultural, polylingual and religiously diverse, a home for Arabs, Kurds, Turkmen, Shabak, Yezidis and Christians.Footnote25

The 2003 Allied invasion forever transformed both Mosul and Iraq, resulting in a breakdown of state structures and employment (de-baathificationFootnote26) and unleashing waves of communal, sectarian and Islamist violence. Within Mosul, the political power vacuum was filled by a Sunni insurgency and popular protests, with many Moslawis rejecting the new sectarian order. They felt excluded, oppressed and mistrustful of growing Kurdish and Shi’a political and military power. The escalation of violence between 2006 and 2008 resulted in waves of displacement of Mosul minorities from the city and absorption of Muslim (Arab and Turkmen) villagers from districts south and west of Mosul.Footnote27 Amid the chaos and disorder, al-Qaeda’s presence (a precursor to IS) began to make its presence felt by way of public protests, the occupation of police stations, kidnappings and the assassinations of journalists, priests, doctors and sheikhs, as well as the infiltration of security apparatuses. A 2016 UN-HABITAT report on Mosul explains,

Known as Mosul’s ‘Shadow Government’, these armed groups gained power and control over the city’s public institutions, administrative system, economic establishments and businesses. They imposed royalties of all sorts on projects and services taking place within the city. Those who did not abide were disciplined or punished. ISIL cannot be separated from these armed groups, even if its name emerged much later.Footnote28

The IS takeover of Mosul was a decade in the making. Moslawi activist Saleem explains, ‘Mosul did not fall suddenly in 2014. This was a coup that was deliberately planned over the years’. Ultimately, the goal was suppression and coercion: ‘the plan was to empty the city of Mosul from all moderate voices from all backgrounds and professions’.Footnote29 For many ordinary Moslawis, the dramatic degradation of their city matched their increasing dislocation from the Iraqi state, culminating in their paralysis in the face of the IS take-over. Moreover, their fading confidence in the state can also help explain their reluctance to leave the city and entrust their fate to the mercy of al-Maliki’s already shaky administration. Mosul residents’ decision to remain and take a chance on life under IS cannot be assumed to be an endorsement of IS’s vision; however, it has given rise to an array of prejudices and generalisations about Moslawis and their presumed tolerance for violent religious extremism. Even after the costly liberation of Mosul from IS in July 2017, Mosul’s residents have been collectively accused of being bystanders or active enablers of the atrocities perpetrated by the terrorist organisation.

In summary, Mosul has witnessed multiple cycles of rise and fall, destruction and reconstruction, always finding a way to resurrect itself. Each of those cycles has left a historic imprint on the psyche and communal identity of Moslawis and, perhaps most importantly, on their susceptibility to recurring attempts to rewrite their city’s history and reimagine its future. The following section will provide an overview of the ongoing public discourse around the city’s contested memory and the ways in which competing narratives may often obscure grievances and simmering tensions and undermine future aspirations for inter-communal solidarity.

Mosul’s memory debates

Mosul’s destruction and its ongoing reconstruction have evoked competing and conflicting urban memory discourses. Three dominant narratives identified in the course of empirical research stand out: nostalgic co-existence and diversity; resistance and resilience; betrayal and exclusion.

Nostalgic co-existence and diversity

Mosul’s diverse and pluralist past is a constant theme of many interviews: ‘Mosul is a city with a big heart. A mother to all of its children’.Footnote30 For those born and raised in Mosul, the city’s multiculturalism is much more than just a historical myth; it is a vision they subscribe to, one which is deeply enshrined in their identity, and which still affords them a sense of pride. Many want to remember and, most importantly according to Adeel, ‘to rebuild Mosul as an idea, not just as a physical structure’.Footnote31 The idea of Mosul is reaffirmed in popular Moslawi tales of commercial co-operation, religious reciprocity during festivals and inter-communal solidarity.

Adeel recollects a famous story set in the 1930s involving a dangerous fault in the iconic Al-Hadba minaret which

nobody could manage to fix except for a Christian mason, Abu al-Tambourshi. It was only the Christian mason, who made it up to the minaret and fixed it. And he insisted that he will not go down unless he left his clenching mark on the minaret.Footnote32

Is this diversity, inclusivity, coexistence today up to the level required? No. Is it at the same level that was prevalent during the times of my father and grandfather? I would say there is no way of making a comparison because during their time it was the zenith of coexistence and diversity; a golden age between different components of society. Nonetheless, our generation today should work hard and strive to revive Mosul and bring back its soul just like before.Footnote33

The nostalgic longing to revive Mosul’s soul is linked to personal stories of dislocation and physical rupture, and the ongoing recovery of home and self. As one displaced Moslawi explains, ‘I have a very strong relationship with Mosul like the relationship between the soul and body. Mosul is geographically part of my identity’.Footnote34

Resistance and resilience

A second dominant memory theme is that of Moslawi resistance against IS propaganda narratives of death and erasure. As one local resident reflected, ‘sometimes we don’t care about the value of things until we are about to lose them. We almost lost our city’.Footnote35 By crafting powerful counter-narratives focusing on life, restoration, and pluralism, Mosul’s residents have sought not only to distance themselves psychologically from the terrorist entity and its extremist ideology but also to shed the misleading image of perpetrators or complacent bystanders, which still casts a shadow over their own victimhood. Committed to reclaiming Mosul’s legacy of tolerance and multiculturalism, outspoken members of the city’s intellectual vanguard such as Omar Mohammed worked diligently to discredit and undermine IS teachings and to prove that none of those takfiristFootnote36 principles resonated with the popular culture and mentality of Moslawis: ‘My battle since June 2014 has been to reverse what ISIS has tried to implant in the consciousness of Mosul’s residents with the only weapon I have as a historian – writing history’.Footnote37

In countering the IS footprint, local historians such as Mohammed have taken on the moral responsibility of rewriting the city’s history by highlighting its legacy as a multicultural enclave. Mohammed is convinced that in order to disarm and neutralise IS as a threat to the country’s stability, Iraqis will first have to re-establish control over the historical narrative: ‘the battle on the historical narrative is still there, and we have to win this by making more public records and archives, building museums, reminding people through all different forms of communication to keep this memory from being damaged by ISIS.Footnote38

To this end, Mohammed has pioneered an ‘Oral histories of Mosul – Resilience and Recovery’ project, collecting and documenting Moslawi stories that was exhibited at Mosul University's Central Library in May 2023.Footnote39 Such initiatives have great potential to uncover hidden narratives and forgotten stories, linking historic events through personal recollections. The challenge, however, remains curation and selection – will such narratives also reflect on the thorny issues of communal grievances, IS support and recruitment and forced displacement? For the sake of the city’s forward-looking reconstruction, scholars and practitioners carry a joint responsibility to investigate the factors which precipitated Mosul’s take-over by IS, as well as the initial acceptance rate among local residents of the terrorist group.

Betrayal and exclusion

The third theme identified in interviews with representatives of the city’s minorities, particularly Christians and Yezidis, is the perception of marginalisation and betrayal. This is believed to have been directed at minorities from both their neighbours and the state authorities. Ibrahim, a Yezidi activist and NGO director explains:

The first blame is towards the Iraqi central government and the government of Kurdistan because they abandoned the Yezidis. Both withdrew without even firing a bullet against the enemy and left Yezidis on their own to face ISIS. This is a fact, and no one can refute it – not even history. The second blame is on the Arabs that lived in the areas inhabited by a Yazidi majority. They helped ISIS to kill and murder Yezidis … Of course, we cannot make generalisations about all Arabs, but a big number of them helped ISIS and there are many proofs and indications, such as the mass graves, in which many Yezidis found their end.Footnote40

As a promoter of cultural dialogue, Ibrahim similarly protests the lack of support for the restoration of Yezidi heritage, despite the important role played by the Yezidi community in the history of Mosul, which in 1649 was even ruled by a Yezidi governor, the famour Ezidi Mirza. The disinterest in restoring Yezidi cultural sites may reflect the fact that Yezidis have no powerful Baghdad allies. Having lost confidence in central government, many disillusioned Yezidis prefer to take matters into their own hands in order to salvage their community’s identity:

Throughout history, the Yezidis were exposed to hundreds of genocides and mass killings and rape, but we did not leave our lands even if we lost 90% of our geography. We continue to preserve our identity and we have confidence that this identity and culture will remain alive…Footnote41

Yezidi persecution blurs temporal boundaries and unites collective feelings of abandonment, victimhood and exclusion. Left unaddressed, these negative sentiments can widen the gap not just between the Yezidis and their Moslawi neighbours but can also deepen divisions within the Yezidi community regarding the most appropriate and beneficial mode of engagement with and within the Iraqi federal state. Moslawi Christian interviewees also have serious doubts regarding both the credibility and the capability of Iraqi authorities to provide communal safety and security. Christian theatre director and activist Saleem explained that since 2005, Mosul had been a prisoner in the hands of competing armed groups and that he himself had on many occasions feared for his life and that of his friends and peers, many of whom had been assassinated. However, when he witnessed IS taking control of Mosul, he experienced a surprisingly strong emotive re-connection to the city:

When Mosul fell, I started to feel a sense of belonging to Mosul. I began to identify myself as a Moslawi. IS premeditatedly bombed very important historic religious sites, such as the tomb of the Prophet Yunus (Jonah) and that of the Prophet Shiyt (Seth). IS also destroyed the shrine of Yahya Abu Al Qasim, Al Hadba Minaret, in addition to many museums and archaeological sites. IS bombed every part that belongs to our identity. We are now left without identity. We are bereft of our history.Footnote42

Saleem’s narrative demonstrates the interwovenness of the memory themes. Finding himself abandoned by the Iraqi authorities, once his native Mosul fell to IS, he felt an individual responsibility to return and reclaim his heritage and place within the city. What Ibrahim and Saleem have in common, however, following the liberation of their city, is not just a lack of confidence in the state but also a genuine trust in youth-led grassroots initiatives to rebuild a version of Mosul that reflects more strongly the nostalgic memories of its resilient residents rather than the fragile urban realities of the time before the IS invasion in 2014.

Reconstruction and memory: ‘revive the Spirit of Mosul’

At the International Conference for the Reconstruction of Iraq in February 2018, UNESCO launched its ambitious ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’ initiative targeting urban restoration through heritage preservation, educational development and the protection of cultural life. The objectives were further clarified at a planning workshop in August 2018, in which officials confirmed, ‘simply returning Mosul to its status before ISIL is not good enough – now is a unique opportunity to “build back better” and develop a people-centred urban vision for the future’.Footnote43

The strategic priority of UNESCO, working alongside the Iraqi State and its religious endowments, has been the reconstruction of Mosul’s religious sites (al-Nouri Mosque and Tahera Church funded by a donation of $50.4 million from the United Arab Emirates); heritage homes; old souks (Bab al-Saray market) and Mosul University’s library. Such an approach exemplifies a ‘heritage as resilience’ policy, which imagines recovering Mosul’s key cultural and religious sites will help renew shared values, collective memories and communal solidarity. In UNESCO’s own words, the aim is to provide a ‘strong message of hope and resistance to Iraq and to the world, a message that an inclusive, cohesive and equitable society is the future that Iraqis deserve’.Footnote44 While initial progress has been hampered by political wrangling, municipal corruption and security dynamics, these projects are underway and have involved local collaboration and specific training of over 1,000 trainees through construction workshops. The prioritisation of elite driven heritage restoration projects, set against a backdrop of Mosul’s stalled economy, limited housing reconstruction and lack of municipal service provision has garnered local frustration and critique. As one Mosul resident explains, ‘The most important thing is to rehabilitate the souls, rather than the stones … in order to spread peace and love instead of terrorism and killings’.Footnote45 Isakhan and Meskell’s study of the UNESCO-led project similarly points to the importance of building in more holistic humanitarian and development features, while providing space to gauge changing local perceptions and responses to heritage restoration. Drawing on UNESCO’s heritage projects in the aftermath of the Balkans Wars, they further warn of the danger of championing heritage reconstruction ‘as a symbol of peace at the expense of enacting meaningful post-conflict reconciliation and stabilisation’.Footnote46

Reviving the Holy: al-Nouri mosque, al-Saa’a, and al-Tahera church

The controversial public discourse surrounding the rebuilding of the iconic al-Nouri Mosque and al-Hadba minaret reveals substantial challenges facing local and international stakeholders, who have taken on the task of its reconstruction. For instance, despite its intentions to bring back to life the original spirit of the mosque, the architectural design endorsed by UNESCO provoked a lot of criticism on behalf of native Moslawis. Criticisms were levelled at the political timing, the foreign involvement and the lack of local engagement. The majority of the city’s residents did not feel adequately involved in the planning process and maintained that the envisioned design differed from the mosque’s original structure and failed to reflect its organic character. Some Moslawis were also suspicious of funding and involvement of the UAE, accusing the UAE of having previously financed Islamist fighters in Syria and Iraq, which helped destroy both countries’ cultural heritage. Lastly, other citizens, while strongly affirmative of the restoration plans, still questioned the appropriate timing; ‘It is useless to rebuild the mosque if there is no real peace and security. It would be terrible if it was destroyed again in a few years’.Footnote47

A key component of UNESCO’s heritage campaign in Mosul also involves the restoration of some of the city’s Christian churches, destroyed and desecrated by IS, who often used the buildings as Islamic courts, prisons and administrative centres. Within the Old City, a complex of four historic churches – Syriac Catholic, Syriac Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox and Chaldean Catholic – now lie in ruins. Collectively they form a Christian square (Hosh al-Bieaa), symbolically emptied of Mosul’s 35,000 Christian community which is estimated to have dwindled to less than 400. Despite the plans and funding to rebuild al-Tahera and al-Saa’a churches, the goal of encouraging the return of Mosul’s Christian community remains elusive. The joint UNESCO and UAE project to rebuild both churches and al-Nouri Mosque draws on the city’s plural heritage and envisages ecumenical cooperation – Muslim and Christian labourers working side by side. However, many Christians question how they can ever return to the scene of their traumatic expulsion or learn to trust neighbours who either participated or were complicit in their persecution. As one Moslawi Christian explains, ‘There is this inherited trauma that it could happen again. How can people go back when some of your own neighbours perpetrated crimes?’Footnote48 Even an Iraqi UNESCO engineer working on al-Tahera church site, questions the limited symbolic value of rebuilding a cathedral without providing social, economic and security safeguards for displaced communities. ‘If Christians visit al-Tahera once it is complete, they will see all the destruction around it. They won’t want to come back and live here’.Footnote49 Such fears raise important questions around the reconstruction’s timing and priorities: should churches or shrines be rebuilt if there is no longer a religious urban community to participate in worship there? Is it enough to have cosmopolitan urban fabric without the actual presence of diverse communities? One Mosul resident captures the inherent dichotomy, ‘while the spirit of coexistence is present in the urban outline of the old city, it is no longer part of its living social fabric’.Footnote50

Everyday sites of trauma and suffering

The reconstruction of post-conflict cities is not only about preserving cultural heritage but also about how to navigate the informal war-scarred landscapes and the detritus of conflict. How should forms of ‘negative heritage’ – ‘a conflictual site that becomes the repository of negative memory in the collective imaginary’Footnote51 be purposefully preserved within reconstruction plans? Some scholars suggest that ruined buildings may serve pedagogical functions, reminding inhabitants of the horrors of war and supporting a ‘never again’ narrative.Footnote52 Karen Till proposes ‘wounded cities’ may offer the potential for collective witnessing, the opportunity to ‘transform memories of violence to shared stories of relevance and critical self-reflection’.Footnote53 Other scholars argue that a tabula rasa approach is needed to create a clean break that encourages social cohesion and therapeutic collective forgetting.Footnote54 The traumatic past is rarely erased or forgotten; however, within Mosul both approaches have been tested and residents remain divided as to whether significant sites connected with local memories of violence should be demolished, repurposed or transformed into memorials.

Reflecting on the city’s dark heritage, Ayoob, founder of the Mosul Heritage House, stresses the importance of sensitive rebuilding programmes which incorporate symbolic sites of destruction, as visible and poignant cues to the very recent urban trauma. As he explains, such spaces ‘will constantly remind Moslawis of the horrific past and make sure that they will never allow for such a war to occur again in the future’.Footnote55 For Ayoob, there is instructive power in the detritus of war, to raise awareness ‘that religious extremism can be fatal’. Hamza, a Moslawi peacebuilding practitioner, instead suggests a unifying memorial, such as the Freedom monument in Tahreer Square in central Baghdad, would be a fitting symbol in central Mosul to unite the city’s communities. For Hamza, the memorial must be positive, forward-looking and emphasising resilience, rather than focusing on past tragic events, by listing the names or portraits of IS victims. He reflects critically, ‘The number of those who died is in the thousands so how can we place all these images? [at the memorial site] This is ridiculous. Why do we want to keep manifesting sadness and agony?’Footnote56 Hamza, is keen to distinguish between life affirming memorials and those that fixate on death, suffering and martyrdom. He is further concerned that such memorials could enflame and invoke calls for revenge against IS family members and even ‘the children of those families who joined IS would pay the price’.Footnote57 These reflections are of particular relevance when deciding the fate of some of Mosul’s most controversial sites associated with IS atrocities.

Probably the most infamous of these sites is the Iraqi National Insurance Company Building, simply known as al-Ta’meen. The height and centrality of the building was exploited by IS as a site for public executions; with victims, often accused of homosexuality or disloyalty, thrown to their deaths below. Built in 1966 and designed by Iraqi architect Rifat Chadirji, the structure was an emblem of Iraqi modernism. Under IS’s brutal reign, this building was rapidly transformed into a symbol of barbarism and inhumanity, with executions filmed and shared locally and internationally. Despite the building’s gruesome past, Moslawis differed on how it should be treated in the future. For some, the war-torn shell should remain as ‘a witness to the ugliness of Daesh’s crimes in Mosul’;Footnote58 others suggest it should be used ‘as a museum to document crimes of ISIL in Nineveh’.Footnote59 The majority, however, struggle to imagine the site without reliving the memories of death, suffering and pain and thus advocate for the complete erasure of the building from the face of the city. One Moslawi interviewee was adamant that any such IS-tainted building or ‘public display that will have a psychological impact on another person must be removed. We should remove any display so it will not be used for political reasons in the future’.Footnote60 The al-Ta’meen building has been recently demolished due to issues over structural integrity, but there are no clear plans on what should be built in its place. Before its destruction, the building was used as an iconic backdrop for a musical concert conducted by Karim Wasfi and sponsored by USAID and Qintara cultural café.Footnote61 The performance was an act of defiance and resilience – a celebration of Mosul’s musical culture suppressed and forbidden under IS – that was made all the more dramatic by its strategic setting. These types of subversive cultural resistance suggest an untapped opportunity in al-Ta’meen’s preservation, which could potentially contribute to forging a new narrative of unity and revival against the background of ruins and destruction. Amra Hadžimuhamedović writing on the post-war recovery of Sarajevo reflects on the power and potential of such forms of culture-based urban resilience:

These cultural rituals in destroyed libraries and museums provided a kind of archaeological backdrop of a disappeared world from before and beyond the siege and invoked a new aesthetic dimension where reality and the surreal switched places. They also served to defend the dignity of the people and, at the same time, to encode symbolic meaning of heroic sacrifice into the remains of destroyed buildings.Footnote62

A second and equally significant trauma site in Mosul is the al-Zinjily, Pepsi Factory Wall massacre. On 1 June 2017, 84 Moslawis were killed by IS snipers as they tried to flee the conflict along a corridor assigned by the liberating forces. For hours, IS fighters kept shooting, killing women, children and men, and sheltering behind the Pepsi factory wall. The local community created a simple painted mural, listing in Arabic ‘The Names of Martyrs of the Massacre of the Pepsi Factory’. This informal response is a clear attempt to acknowledge and memorialise the innocent victims and communal loss embedded in the urban fabric. A local football club who plays on the vacant land next to the site has named the area ‘The Martyrs of Al Zinjily Stadium’, a gesture of respect and honour for those who perished under IS gunfire.Footnote63

While Mosul is replete with posters and images of fallen militia fighters and soldiers, this informal memorial wall is the only collective commemoration directed towards a specific massacre. It raises the question how should those who died during Mosul’s violence be remembered. Should there be an official state-led martyrs’ memorial for all of Mosul’s victims or should local expressions and communal manifestations be supported? A museum of remembrance is currently planned for Sinjar’s Yezidi victims, where a school in the village of Kocho, a site of IS brutality, will serve as a future ‘genocide museum centre’.Footnote64 Challenges remain around the exclusivity and sacrality of such martyr memorials; should they be linked to the mass grave sites still to be uncovered, such as the Khafsa sinkhole in Mosul’s suburbs, believed to contain around 5,000 bodies of IS victims?Footnote65 Perhaps, Mosul’s minorities should share a unified memorial to reflect their collective suffering under IS, but this would also surely lead to friction and tension with Sunni Moslawis who also suffered under IS’s brutal rule. One Moslawi interviewee suggests massacre sites like Khafsa have the potential to be inclusive sites of shared suffering:

In the south of Mosul there is a mass grave where thousands are buried from all different religions. This illustrates the fact that all communities were exposed to communal violence by IS. I am not sure why the UNESCO does not offer to work on exploring this mass grave? It is important for all communities to remember that they all suffered and not a single community won at the expense of the other. They all were affected by war and violence.Footnote66

Questions of commemoration in Mosul remain sensitively linked to unresolved issues of justice, security, property rights and the possibility of return. Nevertheless, everyday sites and spaces of violence and trauma continue to stir narratives of loss and dislocation.

Discussion: prospects for Mosul’s future revival

A number of Moslawi interviewees maintained that they are currently witnessing a unique revival of civil-society activism around the joint cause of rebuilding the city. Interviewees pointed to tree-planting and the restoration of heritage homes, expressing confidence that such youth-driven initiatives have the potential to help to ‘strengthen social cohesion’.Footnote67 In the words of one activist, ‘Youth in Mosul are most capable of restoring and maintaining the cultural heritage of the city. The older generation is not eligible because they have inherited the problems that Iraq struggles with. Youth can be trained and developed to be capable of advancing the city’.Footnote68 This optimism in the potential and malleability of Moslawi youth may be overstated, but there is an opportunity for further investment by international organisations in local youth projects and capacity building. As one female Yezidi Moslawi activist shared, small projects can help reconnect communities and attempt to relink Mosul to important hinterland villages and displaced minorities. Interventions, she warns, must, however, be contextually sensitive, avoid loaded terms such as ‘reconciliation’ and ‘peace’ and garner the buy-in of local leaders, leading to the emergence of diverse and organic ‘projects based on the needs of every area that will strengthen social ties’.Footnote69

The living memories of IS atrocities have nevertheless left deep scars not only on the city’s physical infrastructure but also on the psychology of Mosul’s residents. Mistrust between the different communities, despite being buried under mutual reassurances of empathy and solidarity, still remains an issue. For instance, large parts of the city’s exiled Christian population do not find enough guarantees for their security in order to plan their return. Furthermore, members of the Yezidi community do not feel that their victimhood is being properly acknowledged or commemorated. Indeed, despite the increased awareness of the plight of the Yezidis as citizens, this community demands that its identity is more adequately represented both in the urban politics of the country and in the field of cultural production. As long as the government in Baghdad is perceived as absent or wilfully negligent, representatives of Iraq’s ethnic and religious minorities are bound to disengage even more from the state and draw on ‘competitive victimhood’Footnote70 claims. For precisely that reason, Mosul’s reconstruction offers a golden opportunity to tackle the multi-layered grievances of Nineveh’s disenfranchised communities and restore their confidence in Iraq as their shared homeland. Instead of outsourcing the responsibility for reviving the city’s proud heritage entirely to international organisations such as UNESCO or to donors from the Gulf states, the Iraqi authorities should seize the momentum and re-enter the stage by initiating an inclusive discussion with members of different communities – residing in both Mosul and the surrounding areas – about their visions, ideas, and priorities regarding the reconstruction process.

Our research confirms little consensus exists on how to deal with landmarks of atrocities such as the notorious al-Ta’meen building or the al-Zanjili Pepsi factory wall. However, residents speak of the urgent need for functioning infrastructure such as well-equipped hospitals, schools, and administrative buildings meant to facilitate the provision of welfare and services. On the other hand, the living witnesses of IS atrocities and of the violent acts of vengeance against suspected IS affiliates insist that these events should not be buried under the carpet or erased from the collective memory of the city. Diverging voices in the reconstruction debate deserve to be heard, acknowledged, and engaged with in order for them to develop ownership over the process, regardless of whether the end result reflects their initial preferences. While public consultation does not always lead to consensus, particularly in post-conflict settings, restoring and rebuilding co-existence necessitates the inclusion of all communities. As one female interviewee remarked, dialogue between tribal or communal elites such as Arabs, Yezidis and Shabaks is all well and good, but groups need ‘to hold sessions to listen to the stories of victims’.Footnote71 A number of interviewees confirmed the importance of a varied approach to consultation, which provides spaces for communal priorities and sensitivities to emerge and which can be navigated and integrated within a more holistic strategy.

Conclusions

In Iraq and Mosul, the legacy of undigested historical wrongs has often been wilfully ignored in the hope of breaking cycles of hatred and revenge. Yet for many Iraqis, the past continues to haunt the present, forgiveness is not possible, victimhood is multi-generational, and justice cannot be surrendered on the altar of peaceful co-existence. The challenge of how to navigate such uncomfortable truths is embedded within the daunting task of reimagining Mosul’s future without misrepresenting its past.

Our research suggests Mosul’s long-term recovery must be people-centred, context specific and link cultural memory to everyday life within the city. Grand-scale heritage reconstruction projects cannot be merely historical reminders of co-existence but should also encourage pluralistic everyday encounters and exchanges. The restoration process must not be allowed to serve as a bargaining chip in the political schemes of power-hungry elites, who still tend to use the landmarks of history to divide and rule rather than to unite and protect. Post-war reconstruction therefore requires a delicate balancing of ‘cosmopolitan heritage’ alongside symbolic urban acknowledgement of ‘communal suffering’. To some extent the resurrected city must bear witness to its urban scars.Footnote72

Finally, Mosul’s success ultimately rests on Iraq’s broader political stability, which will require clearer policies around resettlement, compensation and justice. As evidenced in the post-war reconstruction of Sarajevo, ‘establishing the link between physical recovery and the undisputed right of displaced persons to repossess their property is of utmost importance in the restoration of urbanity and its heterogeneity’.Footnote73 In Mosul, future justice may help assuage minority fears but only security, economic investment and viable livelihoods will facilitate long-term minority returns to Mosul and with it the renewal of urban diversity.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by the SSPP Research Ethics Subcommittee at King’s College London (HR/DP-21/22–28252).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Craig Larkin

Craig Larkin is a Reader in Middle East Politics and Peace and Conflict Studies, and Director of the Centre for the Study of Divided Societies at King’s College London. He is author of Memory and Conflict in Lebanon: Remembering and forgetting the past (2012); co-author of The Struggle for Jerusalem’s Holy Places (2013) and co-editor of The Alawis of Syria: War, Faith and Politics in the Levant (2015). He is Research Lead on Memory and Conflict for the XCEPT (Cross-Border Conflict Evidence/Policy/Trends) Consortium.

Inna Rudolf

Inna Rudolf is a Senior Research Fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR) and a postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Centre for the Study of Divided Societies at King’s College London. She has written extensively on Iraqi politics and the evolution of the Popular Mobilisation Forces (al-hashd). Within the XCEPT consortium, she is analysing the implications of identity politics and the mobilisation of violent memories in conflict-affected borderlands.

Notes

1 Karel Nováček, ‘Mosul: Systematic Annihilation of a City’s Architectural Heritage, Its Analysis and Post-crisis Management’, Archaeology of Conflict/Archaeology in Conflict – Documenting Destruction of Cultural Heritage in the Middle-East and Central Asia, Routes de l’Orient Actes II (2019): 249–60.

2 Martin Coward argues, ‘Urbicide entails the destruction of buildings as the constitutive elements of urbanity … Firstly, the conditions of possibility of heterogeneity are destroyed, followed by the imposition of homogeneity’, in Urbicide: The politics of urban destruction (Oxon: Routledge, 2008), 43.

3 Aseel Sawalha, Reconstructing Beirut: Memory and Space in a post-war Arab city (University of Texas Press, 2010); Bruce Stanley, ‘The City-Logic of Resistance: Subverting Urbicide in the Middle East City’, Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 12, no. 3 (2017): 10–24; and Zeynep Ece Atabay et al., ‘Destruction, Heritage and Memory: Post-Conflict Memorialisation for Recovery and Reconciliation’, Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development (2022).

4 Chalcraft, Jasper. ‘Into the Contact Zones of Heritage Diplomacy: Local Realities, Transnational Themes and International Expectations’, International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 34 (2021): 487–501, 488.

5 Mehiyar Kathem, Eleanor Robson and Lina G. Tahan, ‘Cultural Heritage Predation in Iraq: The Sectarian Appropriation of Iraq’s Past’, Chatham House MENA Research Paper, March 2022.

6 Omar Mohammed, an Iraqi historian who ran the blog (MosulEye) documenting life in Mosul under ISIS. The quote is taken from an Interview with Human Rights Foundation - https://twitter.com/HRF/status/1369663584091901952.

7 F. Shaheed, ‘UN Report of the Special Rapporteur in the Field of Cultural Rights. Memorialization processes’, General Assembly, 2014, 4–19, http://undocs.org/A/HRC/25/49

8 Katharine Hodgkin and Susannah Radstone, eds. Regimes of Memory (London: Routledge, 2003).

9 UNDP (2017) Scaling Up in Mosul. UNDP.

10 Maria M. Tumarkin, Traumascapes: The Power and Fate of Places Transformed by Tragedy (Melbourne University Publishing, 2005).

11 From the Balkans, to Beirut, Jenin, Aleppo, to Mosul – See Stephen Graham, Cities, War, and Terrorism: Towards an Urban Geopolitics (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004); Nurhan Abujidi, Urbicide in Palestine: Spaces of oppression and resilience (London: Routledge, 2014); and E. K. DiNapoli, ‘Urbicide and Property under Assad: Examining Reconstruction and Neoliberal Authoritarianism in ‘Post-war’ Syria’, Columbia Human Rights Law Review 51, no. 1 (2019): 253–312.

12 ‘City Profile of Mosul, Iraq, Multi-sector Assessment of a City under Siege’ UN-HABITAT, October 2016, https://unhabitat.org/city-profile-of-mosul-iraq-multi-sector-assessment-of-a-city-under-siege.

13 UN Reports document that 69 of the 202 mass graves found in formerly IS-controlled parts of Iraq belong to Yezidis of Sinjar, leading to the UN’s formal recognition that Yezidis were victims of a genocide. UN Assistance Mission for Iraq report 2018, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23831&LangID=E.

14 Martin Shaw, ‘New Wars of the City: “Urbicide” and “Genocide”’, in Cities, War, and Terrorism: Towards an Urban Geopolitics, ed. S. Graham (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 141–53.

15 Interview with authors, 4 April 2022.

16 Ammar Azzouz, ‘Re-Imagining Syria: Destructive Reconstruction and the Exclusive Rebuilding of Cities’, City 24, no. 5–6 (2020): 723.

17 Kathem et al., Cultural Heritage Predation in Iraq.

18 Bruce Stanley, ‘Conflict and the Middle East city’, in Routledge Handbook on Middle East Cities, ed. H. Yacobi and M. Nasasra (London: Routledge, 2019), 290.

19 Henri Lefebvre, Le Droit à la ville [The right to the City] (Paris, France: Anthropos, 1968).

20 Danielle Drozdzewski, Sarah De Nardi, and Emma Waterton, eds. Memory, Place and Identity: Commemoration and Remembrance of War and Conflict (London: Routledge, 2016); Craig Larkin, Memory and Conflict in Lebanon: Remembering and Forgetting the Past (London: Routledge, 2012); and Scott Bollens, ‘Bounding Cities as a means of Managing Conflict: Sarajevo, Beirut and Jerusalem’, Peacebuilding 1, no. 2 (2013): 186–206.

21 Gusic Ivan, Contesting peace in the post-war city: Belfast, Mitrovica and Mostar (Springer Nature, 2019); and Craig Larkin, ‘Ethnic Identity, Memory, and Sites of Violence’, in The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of the Middle East, ed. A. Salvatore, S. Hanafi and K. Obuse (Oxford: OUP, 2022),609-625.

22 Daniel Bar-Tal, ‘Culture of Conflict: Evolvement, Institutionalisation, and Consequences’, in Personality, Human Development, and Culture: International Perspectives on Psychological Science, Vol. 2, ed. R. Schwarzer and P. A. Frensch (Psychology Press, 2012), 183–198.

23 Frazer Hay, ‘Everyday Sites of Violence and Conflict: Exploring Memories in Mosul and Tal Afar, Iraq’, IOM Iraq, April 2019, 46, https://changingthestory.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/110/2019/07/IOM-Iraq-Everyday-sites-of-violence-and-conflict-April-2019.pdf.

24 Sarah Shields, ‘Mosul, the Ottoman Legacy and the League of Nations’, International Journal of Contemporary Iraqi Studies 3, no. 2 (2009): 217–230.

25 Ibid.

26 De-baathification refers to policy undertaken by the Coalition Provisional Authority and subsequent Iraqi governments to remove the Ba’ath Party’s influence in the new Iraqi political system after the US-led invasion of 2003.

27 UN-HABITAT, ‘City Profile of Mosul’, 11.

28 Ibid.

29 Interview with authors, 5 April 2022.

30 Interview with authors, 17 March 2022.

31 Interview with authors, 10 March 2022.

32 Ibid.

33 Interview with authors, 4 April 2022.

34 Ibid.

35 Interview with authors, 10 March 2022.

36 Takfirism is an extreme, minority Islamist doctrine, applied by IS which permits the killing of other Muslims who they accuse of apostacy.

37 Omar Mohammed, ‘Eye of the Storm: The Historian Known as Mosul Eye on Documenting What Isis Were Trying to Destroy’, Index on Censorship 47, no. 1 (April 2018): 47–49.

38 Putting Mosul on the Global Map: Omar Mohammed of Blog ‘Mosul Eye’ Gives a Voice to Moslawis Reclaiming the Narrative of their City from Daesh”, The Global Coalition, 21 July 2020, https://theglobalcoalition.org/en/mosul-eye-voice-to-moslawis/.

40 Interview with authors, 5 April 2022.

41 Interview with authors, 5 April 2022.

42 Ibid.

43 Roha W. Khalaf, ‘Cultural Heritage Reconstruction after Armed Conflict: Continuity, Change, and Sustainability’, The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 11, no. 1: 4–20.

44 Revive the Spirit of Mosul’, UNESCO, https://en.unesco.org/fieldoffice/baghdad/revivemosul.

45 Sinan Mahmoud, ‘Memories of Mosul: As Papal Visit Approaches, Iraqi Christians Still Worry for Safety’, The National, December 17, 2020.

46 Benjamin Isakhan and Lynn Meskell, ‘UNESCO’s project to “Revive the Spirit of Mosul”: Iraqi and Syrian opinion on heritage reconstruction after the Islamic State’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25, no. 11 (February 2019): 1189–1204, 1200.

47 Isakhan and Meskell, ‘UNESCO’s Project’, 1196.

48 Paul Gadalla, ‘Three years after the Caliphate, Iraq’s Christians find Little Incentive to Return’, Atlantic Council, August 4, 2020.

49 Cited in Lemma Shehadi, ‘The Clock and the Hunchback’, Disegno 29, https://disegnojournal.com/newsfeed/mosul-rebuilding-unesco-iraq.

50 Shehadi, ‘The Clock and the Hunchback’.

51 See Lynn Meskell, ‘Negative Heritage and Past Mastering in Archaeology’, Anthropological Quarterly 75, no. 3 (2002): 557–574.

52 William Logan and Keir Reeves, Places of Pain and Shame: Dealing with ‘Difficult Heritage’ (Oxon: Routledge, 2009); and J. John Lennon and Malcolm Foley, Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster (London: Continuum, 2000).

53 Karen Till, ‘Wounded Cities: Memory-Work and a Place-Based Ethics of Care’, Political Geography 31, no. 1 (2012): 3–14, 12.

54 Tovi Fenster and Haim Yacobi, eds. Remembering, Forgetting and City Builders (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010).

55 Interview with authors, 4 July 2022.

56 Interview with authors 6 July 2022.

57 Ibid.

58 ‘Mosul destroys Iconic Building used by ISIS for Gruesome Killings’, The National, 19 January 2019.

59 Hay, IOM report, 27.

60 Interview with authors, 4 April 2022.

61 ‘Music in Mosul: A Concert Shows that Art can Triumph over the Rubble and Ashes left behind by ISIS’, Middle East Center for Reporting and Analysis, 13 November 2018,

62 Amra Hadžimuhamedović, ‘Culture-Based Urban Resilience: Post-War Recovery of Sarajevo’, UNESCO Paper, 6–7, file:///C:/Users/k1100559/Downloads/activity-953–1.pdf.

63 Hay, IOM Report, 25.

64 Saad Salloum, ‘Planning for Yazidi Genocide Museum Underway in Iraq’, Al-Monitor, 10 March 2019.

65 ‘Unearthing Atrocities: Mass Graves in Territory Formerly Controlled by ISIL’ UNAMI/OHCHR, 6 November 2018.

66 Interview with authors, 20 August 2022.

67 Interview with authors, 7 July 2022.

68 Interview with authors, 22 August 2022.

69 Interview with authors, 4 October 2022.

70 Cagla Demirel, ‘Re-Conceptualising Competitive Victimhood in Reconciliation Processes: The Case of Northern Ireland’, Peacebuilding 11, no. 1 (2023): 45–61.

71 Interview with authors, 4 October 2022.

72 Gruia Bădescu, ‘Making Sense of Ruins: Architectural Reconstruction and Collective Memory in Belgrade’, Nationalities Papers 47, no. 2 (2019): 182–197.

73 Hadžimuhamedović, ‘Culture-Based Urban Resilience’, 22.