ABSTRACT

This paper maps the distribution of post-conflict violence in Belfast and how it has restructured socially, economically and spatially. An end to hostilities and stable transition produces and is produced by a more complex set of distinctly urban assemblages, actors, resources and places. Bringing the ideas of ‘ordering’ into relation with assemblage theory, the paper suggests that explanations for the survival, volume, type and distribution of violence cannot be understood within exclusively ethnonational frames, identarian politics or military logics. In Belfast, the data reveal a more variegated map of peace and consumption; inner-city alienation and the intensification of division; as well as the emergence of new geographies of displaced violence. The paper concludes by emphasising the need to understand how urban processes and competing ethnic orders create highly differentiated spaces that explain the resilience of violence after hostilities have formally closed.

Introduction

The city has been an important site for understanding the nature of conflict, ethnic contestation and peacebuilding and how they are spatialised.Footnote1 How peace, peace processes and actors impact on cities coming out of conflict is also important in explaining the survival of violence after war. The end of war enables new possibilities for reconstruction, modernisation and development and crucially, how institutions, economic interests and investors are encouraged into the city by more secure and de-risked environments.Footnote2 In particular, neoliberal peace processes enable fresh opportunities for accumulation, backed by new rules favouring markets and a central role for the private sector, whilst simultaneously marginalising (and rolling back) the local state.Footnote3

Cities are global nodes for these transitional processes and how they intersect spatially with legacies of conflict, segregation and destruction. All cities are divided by a mix of processes including gender, social class, and religion, thereby making the concept of contestation a useful lens for understanding the socio-spatial (re)ordering of places affected by war.Footnote4 Politically contested cities (such as Brussels or Montreal) naturally persist without producing violence, but where ethnonational disputes spill over into war, the city often occupies a central role in its formation, distribution, and potential for resolution.Footnote5 This is especially the case in the post-warpost-war city and how and where conflict persists in relation to space, new economic realities and the resilience of former infrastructures of violence. Developing the idea of ethnonational contestation, Gusic argues that the

label postwar cities is much more precise since it captures the core of what makes these cities stand out: they have experienced war, no longer do, but are stuck in transitions to peace because they continue to be disputed along conflict lines of war.Footnote6

This paper explores how these temporal processes are spatialised and how specifically urban dynamics impact on overlapping and contradictory trajectories of violence in uncertain peace. The next section looks more closely at what we mean by the city and its role in such processes. DanielakFootnote7 argues that ‘current peacebuilding approaches fail to make explicit the impermanent, ever-changing nature of space – especially in the face of conflict and the oscillating nature of destruction and production in the city’. The paper responds by defining the city, not as a material or economic space, nor one inevitably locked into irreducible ethno-national competition, but as a complex ‘assemblage’ of practices, institutions and actors.Footnote8 The central contribution of the analysis is that it brings this strand of peacebuilding work into relation with assemblages to better explain the urban processes that mediate, reproduce or undercut regimes of violence in the post-war city. In doing so, it builds on a strand of conflict research that examines orders in post-conflict and conflict-affected cities,Footnote9 the distinction between order and securityFootnote10 and how such processes are spatialised.Footnote11

Belfast is especially interesting as it marks 25 years since the signing of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement that brought an end to nearly 30 years of violence in Northern Ireland (often referred to as ‘the Troubles’). In broad terms, Protestants/Unionists/Loyalists want to remain part of the United Kingdom and Catholics/Nationalists/Republicans, in general, want to reunify Ireland, which was partitioned at the end of the Irish War of Independence in 1921.Footnote12 The Troubles broke out in 1969, after years of civil rights protests around discrimination against Catholics in housing and employment and their lack of basic voting rights in a Protestant-dominated society.Footnote13 Internecine violence in the early 1970s, led to the flight of both Protestants and Catholics into more secure heartlands, reinforced territorial segregation and created nearly 90 physical barriers separating the two communities, especially in working-class neighbourhoods to the north and west of the city.Footnote14 This framed the context for the re-formation of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), which was committed to the violent overthrow of British rule and re-energised Loyalist paramilitaries including the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), who aimed to maintain the union with Great Britain. By 1998, 3,720 people had died and 47,541 had been injured in the conflict.Footnote15

The Agreement set up a new power-sharing Assembly, all-island institutions (encompassing both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland), and east-west structures (between the UK and the Republic of Ireland) to strengthen links between Ireland and the devolved regions of the UK. In turn, this was underpinned by the demilitarisation of British army installations (including checkpoints and observation points), disarmament of the main paramilitary groups, especially the PIRA and the formation of a new Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI). Deaths due to conflict declined dramatically but segregation, paramilitary activity and sectarian incidents continued at the same time as the city has both modernised and mixed.Footnote16

The next section examines urban restructuring and how the city is explained as a structurally bound assemblage of resources, organisations and actors. It then connects assemblage thinking with ideas of ‘ordering’ and how both aim to understand the spatial distribution of violence through localised ‘security arenas’ and extra-local economic processes, actors and agencies. The paper argues that such analysis needs a stronger urban foundation in order to explain why cities are significant nodes in both the reproduction and resolution of war. To understand how violence has persisted and restructured in post-war Belfast, we conduct a multivariate statistical analysis using small-area data to explore how a range of urban processes connect economic development, residential integration, and poverty to the survival of low-level sectarian violence and how it is distributed across the city. Our analysis indicates that it is economics such as the impact of inward investment and connected labour and housing markets that shape this post-war city, thereby unsettling ethno-national structures but also failing to penetrate into some of the poorest people and divided places. The conclusion highlights the implications for economic development and its distributional effects as part of peacebuilding strategies in general and urban reconstruction more specifically.

The production of space and the post-war city

A central argument of this paper is that work on post-war cities needs a stronger conceptual grounding in what the city is, how urban space is reproduced and in particular, how place-making processes intersect with regimes of violence. For Harvey,Footnote17 these are linear as well as spatial and he sees the city evolving through industrial waves in which opportunities for value extraction, accumulation and surplus constantly remake space and spatial relations. These shifts involve the movement of capital into secondary and tertiary circuits of capital including real estate, financialization and technology, that replace old sites of production with new opportunities for consumption and profit. This economic transition has been enabled by a range of neoliberal measures including rolling back the state, cutting welfare protection, undermining labour power and disciplining municipal government in favour of flexible forms of governance, better suited to the needs of a more mobile capital regime.Footnote18 In its rollout phase, the market (not the state) is the most efficient means for organising collective consumption (housing, education, health and so on) and public goods; new and increasingly unstable financial instruments and deregulated credit drive development; and cities are encouraged to be more entrepreneurial, competitive and rebranded to cover over evident violence and the potential risks it projects.Footnote19 Time and space have been compressed as national economies are inexorably integrated into a global system and governed increasingly by supra-level institutions such as the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).Footnote20 These discipline cities in former Communist states, totalitarian regimes and the global South into the neoliberal coda and for countries coming out of war, desperate for international credit, reconstruction investment and basic infrastructure, the power to resist is limited.Footnote21

As well as changing the functions of cities, these processes restructure the material fabric of post-war spaces. This involves ‘reterritorialization’ with gated communities, an increase in the private and semi-private public realm and a wider set of actors, especially business interests, enabled by new forms of governance to bypass democratic government, particularly at the municipal level. Footnote22 Regime theorists go further to try and understand how they are produced, especially in conditions of crises, where war and in particular peace, create opportunities for new assemblages to assert their influence, because they have the capital necessary to rebuild shattered urban economies.Footnote23 Regimes that embrace private and public actors, institutions and planning processes form as ‘growth coalitions’ with a focus on downtowns, old industrial sites and waterfronts abandoned in the shift to a service economy.Footnote24 In war, the state and its spending capacity is much reduced so the private sector and specifically property capital has assumed a central role in reconstruction, aided by tax breaks, fiscal incentives, relaxed planning and land assembly programmes.Footnote25 Former war-torn and often, industrial communities, are ignored, removed or co-opted in a process of ‘creative destruction’ in which degraded areas are replaced by new circuits of capital and elite consumption.Footnote26

Moreover, these processes are planetary as neoliberal peace processes provide infrastructure and foreign currency, but also predatory asset grabbing in the guise of reconstruction.Footnote27 Inter-governmental organisations (IGOs) including the WB, IMF and the European Union have fronted complex measures conflating grant aid, fiscal reform, disciplining (local state) spending and crucially, a central role for the private sector in urban renewal.Footnote28 Since local capital is scarce (or non-existent), external investment and its connections with wider geopolitical interests, tend to dominate. As Harvey noted ‘accumulation by dispossession’ is hardly new to colonial and neo-colonial regimes, but brings with it, its own form of violence, segregation and exclusions as corporate interests, military complexes and ethnic logics intersect in the complex arenas of post-war cities.Footnote29

Peck et al.Footnote30 accept that neoliberalism is variegated and locally contingent, in that it is reconfigured (even resisted) where capitalist expansion is curtailed by ethnic violence. To suggest, therefore, that it moves effortlessly from city to city, regardless of their ethnic condition, history of war or cultural memory is too simplistic:

Urban theory should move beyond the numbing theoretical dominance of ‘globalizing’ or ‘neoliberal’ capitalism, and deal seriously with simultaneous forces, movements, agents and politics that co-produce the nature of contemporary urbanism.Footnote31

Yiftachel rejects the academic colonialism of the global North, arguing that Southern contexts are fundamentally different to the liberal-democratic tradition that produces universalist neoliberal explanations of the city. The survival of violence after formal hostilities have ended cannot, however, be understood by descriptions of different configurations of ethnic, contested or divided spaces. Here, Yiftachel and Ghanem (2004) focus on regimes of overlapping power, values and resources shaped by the identity goals as well as the practices of political communities, factions, business groups and NGOs. The state, in its various forms – autocratic, militarised, open or semi-open democracy – is central to the regime because it controls the regulatory environment (laws and fiscal rules), security, including ‘legitimized forms of violence’,Footnote32 institutions, policies and investment programmes. The state, especially in ethno-national form, is not an impotent bystander but has agency in such conditions, which place limits on the political economy of post-war regimes.Footnote33 In its purest form, ‘neonationalism, with its emphasis on the supremacy of ‘native’ groups and rejection of migrants and other minorities, has exacerbated urban conflicts created by contemporary capitalism through oppressive urban practices such as ‘bordering’, ‘gray spacing’, “displacement, ‘economic cleansing’ and ‘racial banishment’’.Footnote34 Political disenfranchisement, economic precarity and aggressive forms of policing further marginalise the ‘otherised’ from urban services, land and decent housing. There are, wider structures, including geopolitical and economic interests that shape cities. How these are assembled, disassembled and reassembled in the transition from violence to peace brings together the structure of security arenas with economic processes, enabled by conditions of relative peace.

The city as assemblage

YiftachelFootnote35 develops an alternative Aleph epistemology to neoliberalism, drawing on the global South, which recognises the interplay between ethnocratic, economic, global and institutional processes. It emphasises ‘the multiplicity of powers working on the city, and the manifold, uneven and unstable social, violent, economic and identity forces together with numerous individuals and agents co-shaping space’.Footnote36 Rejecting an overbearing structural explanation, it focuses on meso-level dynamics that provide room for post-colonial, gendered and governmental approaches in a more dynamic processual understanding of urban change. The heavy impact of global capitalism, networked technologies or the relative weight of IGOs are not denied, but they are not the only source of power and how they explain the different trajectories of cities coming out of conflict. This means seeing ‘the city as an endless composition of changing assemblages’Footnote37 in which macro processes intersect with local agency to shape place in the uncertain transition between violence and peace. This cuts across the concern for orders and arenas but focuses on how they are constituted and put to work, which in turn, implies an understanding of the city and an understanding of conflict. Here, assemblage writers offer frameworks for evaluating such regimes that leaves room for the mix of conflict-driven and for us, economic forces, that shape the post-war city.

Deleuze and ParnetFootnote38 define urban assemblages as a ‘multiplicity constituted by heterogeneous terms (and) which establishes liaisons, relations between them’. This shifts the empirical focus to the interaction between humans, institutions, policy scripts and material infrastructure and how they are persistently in motion across time and space. LatourFootnote39 breaks these processes down, arguing that we can understand how they are constructed, maintained and disassembled in specific urban arenas by studying:

The nature of groups; there exist many contradictory ways for the actors to be given an identity (as policymakers, investors, ethno-national communities, paramilitaries, state security and so on).

The nature of action; in each course of action, a variety of agents can ‘barge in’ and displace the original goals of a previous assemblage.

The nature of objects; the type of agencies participating in interactions seems to remain wide and open and peace can enable new, specifically economic interests, to enter an arena in more pluralist conditions.

The nature of facts is a source of continuous dispute as new cognitive logics (the need for reconstruction) and rationality (about the restoration of market conditions) often edge out previously fixed sources of authority (colonialism, dictatorship, pluralist democracy and so on).

The nature of associations, which can be vertical (connected to global actors and resources) and/or horizontal (how interests relate to each other, say at the urban scale) but externalities (war and peace) can realign these networks in unpredictable ways.

Brenner et al.Footnote40 see such prescription as empirical but argue that it lacks the theoretical foregrounding that neoliberal political economy offers and BenderFootnote41 concedes that the approach levels out actors, when in reality some start with more resources and legitimacy than others. Here, McFarlaneFootnote42 argues that multiple structures shape the arena, but that it needs ‘thick description’ and detailed process tracing to understand how they relate to different sources of power and thus become spatialised. In searching for a ‘more equal urbanism’,Footnote43 ethnic processes cannot be discounted in the city any more than capital interests can, so how they come together is considered next.

Assembling and ordering the ethnocratic city

How then these distinctly urban processes intersect with ethnocratic spaces requires an understanding of the characteristics of violent cities and which forces drive their post-war trajectory. For Yiftachel, the former assemblages of war are resilient, keeping in place the ethnocratic regimes more likely to reproduce violence. Disassembling such structures (by peace accords, security interventions and investment) releases different forces that may not in themselves be peaceful or peace-producing and can leave violent spaces untouched or even create new forms of injustice.Footnote44 For example, in conditions of crises (ethnic volatility, peace and post-settlement violence), the state activates a range of ‘steering mechanisms’Footnote45 to maintain some form of legitimacy. This means reconfiguring the regime to maintain the ethnocratic hegemony, which can take the form of ethnic cleansing, the exclusion of minorities, apartheid and labour market discrimination. The purpose is the reproduction of ‘ethnocracy as a regime facilitating the expansion, ethnicization and control of contested territory and state dominated by the ethnic nation’.Footnote46 But as Yiftachel argues, this is also far from predictable and the complexities of transitional processes bring together multiple forces and how they relate to urban space. Some ethnocracies might be comparatively open, allowing a free press, political competition and citizen rights, which are themselves steering mechanisms designed to maintain or at least not interfere with the overall character of the ethnic nation. But democratisation, especially where it is central to peace accords, unsettles the regime and creates different assemblages, access for new entrants and potential for non-ethnic alliances and networks to secure a territorial foothold. The more post-war cities are de-risked as sites for accumulation, the less traditional ethnocratic regimes can replicate territorial order and control.

More oppressive ethnocracies, autocratic states or military dictatorships foreclose such possibilities and enable state-sanctioned or militia violence to persist, even where hostilities might have formally closed. Yiftachel and Ghanem define the characteristics of such ethnocratic assemblages to include:

The maintenance of ethnic identity as the basis of resource distribution (such as jobs, housing and infrastructure).

The dominant ethnic nation re-assembles and reasserts state apparatus (such as security and surveillance) to deepen its control over territory.

Political boundaries are vague, allowing the dominant ethnic group to marginalise minorities in the absence of weak class alignments.

Ethnic segregation, stratification and discrimination are maintained, but can also be disrupted by economic liberalisation, protective rights or administrative reform.Footnote47

However, these conditions are not confined to the global South nor are they coherent in any single urban regime. In transitional processes, multiple possibilities and how they are assembled as constitutive of space, compete with each other in the same city. Yiftachel and Ghanem argue that

In ethnic regimes, the notion of the ‘demos’ is crucially ruptured. That is, the community of equal resident-citizen (the demos) does not feature high on the country’s policies, agendas, imagination, symbols or resource distribution and is therefore not nurtured or facilitated.Footnote48

Territorial control, ownership, maintenance and defence are intimately connected in the ethnocratic assemblage. The sovereign state and defence of national borders in pursuit of self-determination often obscure more devolved processes in which places are contested, lost and won in the transition from war to peace.Footnote49 For example, Pullan shows that the removal or rejection of the ‘other’ involves selective urban technologies including ‘borders, boundaries, walls, buffer zones, frontiers, security areas, infrastructural systems, dead zones, enclaves, warlord domains, religious bastions, gated communities and so on’. Here, Yiftachel sees ‘gray spaces’,Footnote50 which act as reservoirs for the ethnically excluded, the poor, economic migrants and easily otherized stateless non-citizenry. They form in the deep shadows of the ‘legitimate’ city and its projection of economic, ethnic and moral progress. The regulation of land use and the role played by planning professionals, real estate agents and housing providers are also integral to the property market and the spatial outcomes it creates. In this respect, investment and whether it is controlled by, sits outside or even resists the ethnocracy, underscores the unpredictable nature of capital flows and the limitations of a purely neoliberal reading of the city. At best these processes ‘patch up a broken system of peace’Footnote51 but at worst, they represent a different form of objective violence shaped by poverty and spatial exclusion.Footnote52

The capacity to dismantle the ethnocratic assemblage and to reassemble more civic alternatives thus explains, in part, the durability and spatial distribution of post-warpost-war violence. CaplanFootnote53 argues that the consolidation of peace involves a combination of motivation, the feasibility of further war and the resilience of national institutions. Grievance factors over relative deprivation or ethnic insecurity can motivate combatants, but this needs to extend beyond elites and military groups to properly destabilise emergent democracies and civic institutions. Feasibility is dependent on materials and logistics, which disarmament and dismantling paramilitary structures might weaken, if not end, the capacity for further violence. Both are variable and mediated by the resilience of post-warpost-war political structures, state institutions and security arrangements. The strength of the assemblage to survive internal and external pressures and the capacity of governance structures to cope puts stress on the adaptive capacity of the peace regime. Resilience

places the emphasis on the characteristics of a society – its norms, practices, culture and institutions – that serve to insulate it from the threats rather than on an intrinsic condition (stable peace) and what is required to achieve and maintain it.Footnote54

Unravelling the assemblage in transitional processes also shows that the causes of conflict, its reoccurrence and/or peace are not linear.Footnote56 Whilst war and peace share several risk factors, the transformative quality of violence itself creates threats and new possibilities.Footnote57 Reflecting the debate on internal and external orders, Cummings et al.Footnote58 distinguished between attitudes at the micro or community level and the extent to which violence is tolerated publicly, while the meso level focuses on the structures, motivations and logistics of combatant groups. Macro forces, then, relate to the influence of political parties, policy processes, business elites and international actors and the extent to which they can exercise influence over subordinate layers. But the macro is often described as a range of various non-local processes, when it is argued in this paper, that they are far more coherently organised as an economic assemblage aimed at accumulation and surplus in moments of destruction.

Waterman and WorrallFootnote59 considerably advance this conceptual framing by focusing on ordering as a way of understanding violence, peace and transitional processes. Internal orders, such as around the organisation of sites of enduring spatial violence, are ‘nested within the wider social order, different components and actors within the organisation each have their own forms of capital, have their own interests and are connected to different parts of the wider social order’.Footnote60 HillsFootnote61 uses order to examine post-conflict transition, arguing that residual conflict-era ordering practices and power relations can shape continuities into the post-war period. However, these dynamics interact with, resist and/or are re-formed by new and modified patterns as cities move into relative peace. GlawionFootnote62 also attempts to understand contexts of violence by distinguishing between the state, non-state and international levels in order to position combatants and civic actors in overlapping institutional regimes. Understanding the legitimacy, relative power and access to resources that each possesses builds an understanding of their spatial expression in ‘security arenas’. This focuses on the operation of state and non-state actors (paramilitary groups, officials, politicians); rationalities of violence (rooted in economic exclusion and discrimination); practices of disorder (intimidation and coercion); and the creation of rules (including the distribution of public goods) that reproduce the arena across time and space. Glawion expands on Hills to recognise spatial variations in these processes by distinguishing between the inner circle where violence survives and an outer circle where democratic institutions, regularised decision-making and non-violent bargaining create new possibilities for stability. But there is a fluid continuum rather than a binary in which a range of economic, institutional, social and military structures compete and interact in a more complex urban assemblage. This specifically adds to the sources of power that explain the scope and structure of a particular assemblage. How this multi-level structure is assembled and interacts, helps to explain variations in peace outcomes after war and recognises that each level might be characterised by its own dynamics – liberal peace at the macro scale failing to connect with enduring sectarianism at the micro. The point is that these macro processes, whilst not exclusive, are dominated by capital interests and how they assemble growth regimes that increasingly shape urban governance and space. Such assemblages as noted may not penetrate the most violent spaces where the security arena both hold ethnocracy together, but also ensures that it does not infect new sites of investment and privilege. Not everything is explained by the growth machine, but it emerges as a coherent source of power at the macro and the local level. Understanding these scalar processes and how they are configured spatially is attempted to some extent, in the limited context of one city. The next section thus takes a macro approach to Belfast and how socio-spatial patterns reveal the multiple economic processes at work in a drawn-out peace process.

Methodology

The purpose of the data analysis is to understand the organisation of the post-war city and how and where violence is distributed. This involved two related stages. In the first, a comprehensive geocoded dataset was constructed to map where deaths and injuries happened after violence had formally ended. This identified spatial concentrations but also complexity in the emergence of new geographies of displaced violence. The second stage aimed to provide a deeper explanation of these trends by integrating socio-economic variables that reflect how the city has restructured in post-conflict conditions. Such macrostatistical analysis has limitations but also responds to criticisms of ‘telescopic urbanism’Footnote63 that focus on essentialist cases without a deeper understanding of the processes that structure violence and how it moves across time and place. It is not a case of one or the other and the data presented here are about one scalar approach that aims to explain, in part, how conflict, labour and housing markets and the production of place intersect.

The first stage was to understand the distribution of post-war violence in Belfast, which was conducted as part of a cross-national data collection study on conflict-related violence in post-war cities.Footnote64 This involved manually coding violent events using the Factiva news sources database, complemented by academic materials (such as https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/sutton/), online forums, local press, research reports and historical maps. These were categorised and mapped using longitude and latitude coordinates across the city and sorted into different levels of geo-precision and conflict-related clarity, based on the information available. Violence is understood as the use of direct physical force exerted by one actor against another and includes shootings, beatings, torture, and rape; that is, violence with the presumed intent to cause major bodily harm resulting in physical injury.Footnote65 This coding was based on the Uppsala Conflict Data Program’s (UCDP) Conflict Termination Dataset, which includes conflicts terminated by agreement or where battle-related deaths decline to less than 25 per year for at least 5 years. In Belfast, the data collection covered the periods between the 25th of November 1991 (when fighting dropped below levels of active warfareFootnote66) until renewed fighting in 1998, and then from the end of armed confrontations the same year until the 31st of December 2019. In this analysis, the data used covered the period between the 25th of November 1991 and the 31st of December 2019 and included 1,042 unique post-war violence events involving 206 deaths and 2,795 injuries. This covers the period of a substantial decrease in violence, two PIRA ceasefires in 1994 and 1996 and makes the point that transitional processes are not bound into formal peace agreements and fixed dates, such as that in 1998. Moreover, we make the point that space is reordered by global economic processes, national policies and local planning regimes that are not dictated by the formalities of peace agreements, but by the changing dynamics of risk and uncertainty, instability and local guarantees (in planning, security, investor confidence and so on). It is useful therefore to see violence, economics and social changes and how they move across place as a less determined temporal-spatial fix.

The analysis aims to explore the relationship between a mix of ethnocratic, economic and social processes and how they connect spatially in a post-war city. Large-scale quantitative description is, of course, only one methodology to understand the dynamics of change but given the focus on the urban assemblage, it offers a way of framing space and violence and how it can be understood in a particular case. To do this, we use exploratory factor analysis, which is a method for synthesising a wide range of variables across cases (or geographic units) to identify the associations that can explain variations in the overall dataset.Footnote67 The unit of analysis is the electoral ward, where there is the most comprehensive range of data collected on a routine basis and made available in an open government statistical repository.Footnote68 There are 224 electoral wards in the Belfast Metropolitan Area (BMA) with an average of around 3,000 people that comprise the unit of analysis for the model. The BMA has a population of 760,000 people and the city region dynamic is important to understand the geosocial distribution of violence after war.

Statistical indicators that describe the condition of cities during and after war are complex given the decline in deaths, military engagements and the use of arms. Surrogate indicators reflective of the process that connects in the post-war city are restricted by what is available, the level of spatial analysis and the comparability of measurement units. Therefore, the variables aim to reflect (not precisely) the competing strands of change – economic, housing market, enduring sectarianism, poverty and crime – that connect across post-war Belfast. An array of 24 variables at the electoral ward level was subject to Pearson’s correlation analysis to show connections, overlapping predictors, swamping variables, outliers and indicators with weak covariance that would not add to the explanation of the data. The correlation analysis helped to reduce the number of variables to 12 and these are included in the full factor analysis (see ). These measure crime over time as well as sectarian and racist incidents reported to the police. Average and Maximum Capital Value reflected house prices and high (and low value) neighbourhoods, whilst Income Support is a welfare benefit that supplements household incomes and Housing Benefit helps the poorest individuals with rental costs. Steps to Success is a specific programme aimed at young people who are not in school, training or employment, whilst people with a Degree Level (or higher) qualification reflected the upper end of the labour market. Interestingly, Newcomer Pupils also indicate changes in the housing market and are correlated with racist incidents to show the effects of migrants and immigration attracted to a largely peaceful and growing economy and particular places within it. These are also correlated with School Suspensions and Multiple Deprivation, which is a composite indicator reflecting the extent of socio-economic disadvantage by area.

Table 1. Component matrix.

The distribution of post-war post-war violence

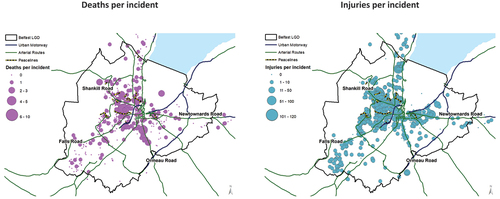

maps the distribution of the 1,042 deaths (by incident) between November 1991 and December 2019. In broad terms, it shows a high degree of correlation between violence during the Northern Ireland conflict and incidents in the inner-city, west Belfast as well as interface areas dividing Protestant and Catholic communities. However, it also shows dispersal, especially in public sector housing estates that ring the city in both Republican (south and west) and Loyalist (east) neighbourhoods.

This pattern is repeated when the 2,795 injuries are mapped, despite clear correlations with the spatial distribution of deaths. Traditional hotspots in the inner east, west and north are evident along with the arterial routes in the south that reflect tensions around traditional Loyalist parades, which were restricted as part of the peace Agreement. Peace brings emergent tensions around a sense of loss (territory, identity and resources), accommodation on the use of symbols and restrictions on parades that stimulated different forms of violence across the city.Footnote69 Similarly, suburban locations are also profiled, emphasising a degree of dislocation and complexity to the pattern of violence (and peace), especially after 1998. To understand such restructuring and its socio-spatial effects, the analysis draws on a wider range of macro indicators in which to situate deaths and injuries in the city and over time.

Patterns of violence and peace

In short, violence after peace cannot be read apart from the range of socio-economic, demographic and material processes that comprise the urban assemblage in transition from war. Factor analysis enables such integration by reducing the variables, different types of data and the scores for each of the 224 electoral wards to a smaller number of summary indicators (or factors). The analysis produced three factors as set out in . In short, each factor is distinguished by a particular correlation pattern, although as the coefficients show, there are overlaps and these should not be seen as mutually exclusive categories. The model explains 82.23% of the variation, which is a high level of cumulative score and these are now considered in turn.Footnote70

Factor 1 urban splintering and the gray city

Factor 1 accounted for 38.12% of the variance and shows that these tended to be the wards with the highest rates of sectarian incidents (.782) and all crime (.678). The table also shows the high correlation scores with poverty-related variables including the multiple deprivation index (−.840), welfare benefits (for housing rent [.957] and income support [.884]) and referrals to Steps to Success (.919). Few gain a higher education qualification (−.138) and pupils suspended from school (.850) reflect the complex structure of the social challenges faced by young people in these wards. Gallaher and ShirlowFootnote71 make the point that such conditions have enabled the transition from political to criminalised violence and related paramilitary restructuring. Alienated young people with few economic alternatives are inducted into gang cultures, drug dependency and easy money from which there is little or no prospect of escape.Footnote72 Rickard and BakkeFootnote73 also explain the coercive and violent discipline imposed by Loyalist paramilitaries including punishment beatings and shootings, murders and exclusion from the community. Drug dealing and money lending have expanded in which territorial control is critical to the operation of a pervasive black economy. Space and rehabilitated paramilitary structures go hand-in-hand but segregation and peace lines are performatively different. Whilst their origins might be rooted in the fear and violence of the late 1960s and early 1970s (and whilst such processes have endured), criminal logics now also maintain territorial boundaries and enable communities to be controlled and exploited.Footnote74 Paramilitary structures, place, gang members and materials in the form of weaponry and supply chains, distribution networks and debt collection systems are all part of the factor 1 assemblage.

This is not Arjona’sFootnote75 ‘rebelocracy’ as paramilitary groups do not exercise total control over the neighbourhoods in factor 1. Rather, it is more reflective of conditions of a drawn-out, but spatially focused disorder in which opportunism, intra- and inter-gang competition and criminal networks attempt to reassert a form of rebel governance. Indeed, Rickard and BakkeFootnote76 point out that such structures are always unstable, due to persistent top-down and bottom-up processes. Top-down factors include criminal operations, materials and weapons and socialising new members within the norms of armed groups, all vital in the ‘internalization’ of territorial control.Footnote77 But bottom-up practices are also critical and the maintenance of a particular paramilitary assemblage relies on both. The reform of policing in Northern Ireland was critical in the establishment of a less partisan force and part of the re-formed counter-assemblage following the Agreement in 1998. However, as Rickard and Bakke show, informal paramilitary policing, especially in Nationalist areas, where acceptance of the new police service has been patchy, has been maintained by a degree of community legitimacy.

In this respect, violence cannot be easily codified into acceptable or unacceptable, which is part of its very survival.Footnote78 It is, however, wrong to assume that responses at the neighbourhood level are framed within an exclusive paramilitary (reformist or criminal) security arena. Community groups and civic society organisations have developed local assets and created social enterprise models in response to changing economic realities. Many work across communities, build facilities on interfaces or deliver common services to segregated neighbourhoods in some of the most divided and formerly violent areas of the city.Footnote79 Similarly, Gallaher and ShirlowFootnote80 point out that it would be wrong to see Loyalist violence as purely criminalised. They argue that, as with Republicans, there are many Loyalists who refused the Agreement because of the emphasis on power-sharing, a guaranteed role for the Irish state in the affairs of Northern Ireland and the right to a referendum on the border. Similarly, GanielFootnote81 points out there are countermoves, structures and practices that compete with criminal assemblages, often pitting former comrades against each other.

Here, a more class-conscious Loyalist identity has embraced a community development approach, supported local businesses and formed alliances across the interface on education, training and providing welfare services. The conflicts within and between these re-forming movements are also spatialised. shows that the heartlands of violence are reproduced in north and west Belfast as well as in the inner city. However, there are new concentrations of violence as paramilitaries have relocated (or been forcibly removed) out of such neighbourhoods to assert a new power base in housing estates in Bangor, Newtownards, Larne and Carrickfergus. Such sites and their attendant poverty enable a rapid reassembly of paramilitary structures often with loose connections to each other, to reach the scale necessary to assert control, fend off rivals and maintain security. As Waterman and WorrallFootnote82 note, threatening, supportive and protective practices are simultaneously enacted to shape a distinct place-based security arena. But such practices are inherently unstable and where rebels are extractive or fail to improve local lives (by providing services, education or work) their hold on place is short-lived and persistently disordered.

Republican paramilitaries have also restructured and re-spatialised although not in the same way nor to the same extent. The PIRA ceasefires in the 1990s were relatively disciplined and despite a lack of initial commitment, independent observers state that the decommissioning of weaponry, organisational structures and member networks was comprehensive.Footnote83 However, splinter groups that refused the 1998 Agreement, remained committed to the armed struggle. They are not well resourced nor militarily sophisticated and lacked the legitimacy across working-class Catholic communities that sustained the PIRA campaign.Footnote84 Some former Republican criminal entrepreneurs do operate and Brexit has re-energised demands for a Border Poll, especially among disaffected young people in which the peace process has done little to improve their lives.Footnote85 shows that this type of Republican violence is evident in suburban housing estates and poorly serviced commuter towns in the urban fringe, such as Crumlin and Antrim, where Republican paramilitaries still have a foothold.

In factor 1, combatants can retain control over the internal territory and albeit imperfectly keep external security actors out, insulate the order from reformist politics and deny capital access. But, where they cannot, a distinct set of external and multi-scaler processes, linked to the global economy and mobile investors, can penetrate the internal order and displace or remove altogether, territorial structures of violence. The point about post-war cities is that we see these simultaneous contests acted out within increasingly complex and unstable, but geographically proximate processes. Orders of violence and orders of peace co-exist, reflected in the emergence of the cosmopolitan city.

Factor 2 the cosmopolitan city

shows that factor 2 is more complex with a comparatively high crime rate (.567) but lower levels of sectarian-motivated incidents (.208). The distribution of violence (and its relative absence) has less to do with territorial heartlands and more with restructuring in the housing and labour market, especially in the urban core and along a band of wards that extend southeast from the city centre. These are areas, shown in , with the highest average capital value for domestic property (.584), some of the most expensive housing in the city (.524) and persons with a university qualification (.769). However, the statistics also show that there are a relatively high number of newcomer pupils (.407) and racist motivated attacks (.552), showing that these are also places where new immigrants are living. There are migrants in factor 1, attracted by cheap rents in poor neighbourhoods that have set off a degree of competition between residualizing Protestant communities and incomers. In factor 2, however, skilled and key workers, live in higher-value private renting which shows the increasingly integrated nature of global labour markets and how they impact on Belfast.

In his analysis of re-emergent violence, WorrallFootnote86 draws attention to other drivers of ordering including civic society, external actors and processes operating well beyond the influence of rebel groups. In post-war cities, these external ordering processes are invariably about the making of urban space. Here it is capital dynamics, the property economy and new investment that have restructured spatial relations and the prospects for continuing violence within them. The post-conflict economy of Belfast has developed remarkably with inward investment, tourism and the development of knowledge-intensive, high-growth labour markets.Footnote87 Urban regeneration policies have prepared new sites for development in which old industrial areas, including the former shipyard, have been redesigned for back-office services, tech businesses and science parks.Footnote88 New, young professionals, increasingly occupy such spaces encouraged by apartment developments and gated housing projects. Urban branding is speculatively mobilised to attract visibility, investors and tourists, simultaneously ‘silencing local perspectives and avoiding controversial issues’ in working to their globalising objectives.Footnote89 In this context, we can also see the continuity – albeit in a restructured form – of Belfast’s defensive architecture (such as walls, barriers, roads, fences and gates) that additionally hinders those who are socioeconomically deprived from regenerated parts of the city.Footnote90

Ulster University has moved its main campus into the Northside of the city centre and the impact of studentification and youthification is reflected in increasing ageing in the suburbs in factor 3. Moriarty et al.Footnote91 show that between 1991 and 2011, the proportion of household heads in the highest Socio-Economic Groups (SEGs 1, Employer/Manager/Professional) increased from 22% to 36%; but at the same time, the proportion of the lower SEG 3 (Routine/Manual/Unemployed), increased from 31% to 39%. The middle class (Intermediate SEG 2) has been squeezed the most, declining from 47% to 26% as a result of the loss of work in manufacturing, the public sector and security forces. What is most interesting from the analysis is that those who find their way into SEG 1 are mainly male, educated to a degree standard and whose parents were in professional occupations. Religion has been effectively removed as a determinant of social destination and critically, where people live in emerging spaces to the centre, south and east of the city. The boundaries are fuzzy, but increasingly, factor 1 and factor 2 are disconnected, not just by walls and territoriality but by a skills mismatch and a spatial mismatch. Deprived communities, where segregation and violence persist, lack the skills and even basic education to access knowledge-intensive labour markets; and new investment sites are no longer centred on traditional working-class neighbourhoods but along the waterfront, in Northside and in the recovering Central Business District. Violence is still present in these spatial dichotomies in which mobility, economics and the securitisation of space run hand-in-hand as Gayer and RussoFootnote92 found in Karachi:

The new urban arrangement has turned freedom of movement into a corporate privilege, proclaiming the domination of capital through an asymmetry of mobility. The enforcement of industrial order through the control of urban space and circulations resulted in the formation of industrial enclaves regulated by extralegal violence, including on the part of private guards recruited for the protection of industrial assets.

Whether (and how) such socio-spatial processes ultimately create less violent, sectarian or exclusive identities are, of course, empirically difficult to assert. Abrams and VasiljevicFootnote93 draw on Social Identity Theory to show how the macroeconomy impacts on individual identities; interpersonal relationships; small and local group membership; and in social organisations and institutional systems. Identities can be ascribed (religion), elective (say a political party) or involuntary (unemployment) but these are negotiable and deeply influence socio-cognitive processes that link the self with a particular group or category (and vice versa). At times of economic downturn, identities are affected by uncertainty, enhanced anxiety and heightened mortality salience, reproducing in-group favouritism and the certainties it provides. Abrams and Vasiljevic look at consumerism, consumption patterns and customer confidence to reflect macro-economic trends, although as has been argued here, production and how labour markets (and then housing market mobility) shape socio-spatial identification are equally important. Higher social cohesion is encouraged because lower transaction costs enable the economy to expand outside the in-group (and its territory); higher investment leverage; innovation; more effective institutions; and reduced social costs (such as welfare subsidies) as jobs and wages increase. Recession causes pessimism, inter-group bias and malign antipathy but growth produces diversity, necessary interdependencies in work, market exchanges and education and ‘wider acceptance of shared values and tolerance of different values, greater flexibility and responsiveness to opportunities, more ambitious and creative activity, secure national identity, pride etc’.Footnote94 The economics of peace and its externalities is, to some extent a site of potential for the most divided and deprived communities where violence disconnects them from the post-conflict growth regime.

Factor 3 the suburbs

shows that factor 3 is the smallest component at 17.93% and that these areas have negative overall crime rates (−.268), low multiple deprivation scores (−.153) and a near-zero rate of sectarian motivated incidents (.052). There is also a negative correlation between new school pupils (−.398) and racist-motivated incidents (−.328) suggesting that these are housing markets not accessed by migrant groups. However, there are (albeit weak) correlation coefficients with Steps to Success (.220), Housing Benefit (.211) and Income Support (.337). shows that this factor is concentrated in the comparatively wealthy suburbs to the south and east of the city and prosperous coastal towns including Crawfordsburn and Hollywood. However, there are also peripheral housing estates such as Poleglass and Rathcoole in the west and north, respectively. Despite the evident prosperity of much of the area, students gaining a Higher Education Qualification is low (.232), which reflects population ageing rather than poor economic performance. In their analysis of demographics, Murtagh et al.Footnote95 showed that between 2001 and 2018, the proportion of people aged 65 and over increased from 15.3% to 17.6% in Belfast’s suburbs and from 14.7% to 18.5% in the metropolitan fringe beyond these neighbourhoods. At the same time, the percentage in the inner-city declined from 14.1% to 11.7% encouraged by the youthification and studentification characteristic of factor 1. It is important, therefore, to recognise the multiple processes around ageing, immigration and ethnic identities that change the post-war city. The various strands and how one set of processes (youth and ageing) intersect with ethnicity and economics do, as McFarlane suggests, need to be unravelled to understand the distribution of violence and the distribution of peace.

Conclusions

This paper aimed to bring work on orders of conflict into relation to concepts of urban assemblage to better understand geographies of violence in cities coming out of war. Here, the conclusions draw out three implications on the interface between orders and urban assemblages. It then reflects on the limitations of the methods and on the need to move beyond normative data representations to understand the political economy of post-war cities. First, security arenas highlight the structures that reproduce violent orders, especially where armed groups can retain their legitimacy, re-form militarily and assert influence through different modes of control and coercion. The inner circle, where violence is concentrated, is held in place by well-organised military and paramilitary actors. It is the ‘conflict researcher’s comfort zone’.Footnote96 However, how a wider set of multi-scalar urban processes impact on tightly defined security arenas and an inner-outer binary is less clear. The outer circle and higher-level orders need to be understood as economic assemblages with well-articulated objectives (the pursuit of surplus), logics (stable market conditions) and institutional regimes (that preference private accumulation). Peace enables these assemblages to organise by reducing risk, providing a degree of security and aligning government and governance with the needs of the market. These scalar processes, of course, contain a range of actors and resources, but when we focus on space, it is the way in which the political economy is enabled that helps to explain the configuration of differentiated post-war geographies.

Assemblages of violence also survive and are capable of resisting the insertion of re-formed neoliberal regimes. But here, economics is also important. Such assemblages are reproduced, at least in the deprived neighbourhoods of Belfast, because they are poor. Peace has not trickled down, the material benefits are limited and levels of violence have merely stabilised or even increased. It is economics that helps to explain why assemblages of violence are reproduced, rather than simply the capacity of internal orders to survive peace. The security arena is also then, about containing such processes to ensure that they do not risk the accumulation regime remaking part of the post-war city. The containment of violence and confining it to more manageable spaces, is thus vital for the extension of the post-war growth machine and the form of economics and politics that comes with it.

This relates to a second understanding of orders and ordering. These are not categories to be understood empirically but are active regimes with clear structures and aims, modes of working and network capacity. The operation of such regimes points us to the way in which arenas – security are otherwise – are assembled in the pursuit of political and economic (and increasingly political-economy) aims. Enduring paramilitary infrastructures are often re-formed (not always) for exploitation via deviant (black and grey) economies and in resource competition with criminal (non-political) gangs and territories. This means understanding legitimation tactics within the place community by, for example, providing public goods and local services, exercising force and coercion and connecting with other extant paramilitaries. Of course, as the evidence from the case study shows, economic logics do not always penetrate places where assemblages of violence persist, but they persist, in Belfast at least, because poverty allows them to.

The third point is about empiricism and in particular about understanding how specific orders work in practice. Process tracing, in the remaking of the city, is about arenas, who is in them, what legitimacy and power they exercise, their motivation and capacity to act, their ability to outmanoeuvre or out-muscle others and so on. Here, assemblages ask us to look at specific variables including actors and for the city, their ability to create, destroy or remake space; their actions, practices and ways of working; what capital leverage they possess, which might be military as well as financial hardware; how they make their case in the use of knowledge and propaganda; and how practically and tactically they connect with higher orders or other stakeholders in the arena. The point about assemblage thinking is that it focuses on the constitution of the arena and how competing urban regimes create alternative futures within the same city.

To be clear, these issues are only touched upon in this paper. The data presents a large-scale description of metropolitan change that reveals the multiple processes shaping different spatial trajectories after war, but its normative base is, to some extent, part of its limitation. Factor analysis can indicate the nature of restructuring in relation to a range of variables reflective of a mix of predetermined processes. But what assemblage thinking permits, is a contingent analysis of the production of these spaces and how specific economic, social and cultural processes favour a more dominant form of ethnic or capital space. The relationships embedded in these assemblages need to be unpacked empirically as well as conceptually to explain their actually existing condition. The data can indicate a certain configuration but does not explain how assemblages work in practice and why some socio-spatial processes variously create ‘orders’ of peace and stability, new types of economic violence or rehabilitate old forms of war. How orders are structured in relation to economic processes in the making of space offers important interdisciplinary opportunities between conflict researchers and urban studies. Urban governance and the assemblage of growth regimes have made for unstable and contradictory spatial processes in post-war cities and can disrupt as much as they can anchor peace processes themselves. A deeper understanding of the realities of economic violence, the multiple sources of ethnic power and local legitimation tactics are also important in creating a just and inclusive peace.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Brendan Murtagh

Brendan Murtagh is Professor of Urban Planning at Queen’s University Belfast (United Kingdom). He has researched and written widely on contested cities and is currently leading grant projects on the economics of peacebuilding; social economics and the city; and community wealth building in vulnerable urban areas. Email: [email protected].

Emma Elfversson

Emma Elfversson Associate Professor at the Department of Government at Uppsala University. Her research concerns urban/rural dimensions of organized violence, ethnic politics and communal conflict, and the role of state and non-state actors in addressing conflicts. She is leading international research projects on ‘The Urban Dilemma: Urbanization and ethnocommunal conflict’ and ‘The Continuation of Conflict-related Violence in Postwar Cities: Mapping Violence at the Street Level’. Email: [email protected].

Ivan Gusic

Ivan Gusic Assistant Professor at the Department of Government at Uppsala University. Ivan’s research interests include war-to-peace transitions, postwar cities, urban peacebuilding, and the spatiality of war, peace, and violence. He has built a strong empirical understanding of postwar cities, especially Belfast, Beirut, Jerusalem, Kirkuk, Mitrovica, Mostar, Nicosia and Sarajevo and is engaged in a long-term project on post-Yugoslav spaces and urban restructuring. Email: [email protected].

Marie-Therese Meye

Marie-Therese Meye is a PhD student in Political Science (CDSS) at the Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of the University of Mannheim (Germany). Her research interests include ethnic conflict, militant fragmentation, social movements and the temporal and spatial dynamics of violence. She has conducted extensive research on the Northern Ireland conflict and has previously worked as a research assistant in ‘The Continuation of Conflict-related Violence in Postwar Cities’ project with Dr Elfversson and Dr Gusic. Email: [email protected].

Notes

1 Annika Björkdahl, ‘Urban Peacebuilding’, Peacebuilding 1, no. 2 (2013): 207–221.

2 Ruben Gonzalez-Vicente, ‘The Liberal Peace Fallacy: Violent Neoliberalism and the Temporal and Spatial Traps of State-based Approaches to Peace’, Territory, Politics, Governance 8, no. 1 (2020): 100–116.

3 Ibid.

4 Emma Elfversson, Ivan Gusic, and Brendan Murtagh, ‘Postwar Cities: Conceptualizing and Mapping the Research Agenda’, Political Geography 105 (2023).

5 Jonathan Rokem and Camillo Boano, ‘Introduction: Towards Contested Global Geopolitics on a Global Scale’, in Urban Geopolitics: Planning in Contested Cities, ed. Jonathan Rokem and Camillo Boano (London: Routledge, 2018), 1–13.

6 Ivan Gusic, ‘Divided Cities’, in The Palgrave Encyclopaedia of Peace and Conflict Studies, ed. Oliver Richmond and Gëzim Visoka (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2020), 1–9.

7 Silvia Danielak, ‘Conflict Urbanism: Reflections on the Role of Conflict and Peacebuilding in Post-apartheid Johannesburg’, Peacebuilding 8, no. 4 (2020): 447–459, 449.

8 Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

9 Alex Waterman and James Worrall, ‘Spinning Multiple Plates under Fire: The Importance of Ordering Processes in civil wars’, Civil Wars 22, no. 4 (2020): 567–590, 567.

10 Alice Hills, Policing Post-Conflict Cities (London: Zed Books, 2009).

11 Tim Glawion, The Security Arena in Africa: Local Order-Making in the Central African Republic, Somaliland, and South Sudan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

12 Brendan O’Leary and John McGarry, The Politics of Antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016).

13 Ibid.

14 Ivan Gusic, Contesting Peace in the Postwar City: Belfast, Mitrovica, and Mostar (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2019).

15 David McKittrick, Seamus Kelters, Brian Feeney, Chris Thornton and David McVea, Lost Lives (Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 2007), 1552.

16 Mary Murphy and Jonathan Evershed, ‘Contesting Sovereignty and Borders: Northern Ireland, Devolution and the Union’, Territory, Politics, Governance (2021): 1–17.

17 David Harvey, The Limits to Capital (London: Verso Books, 2006).

18 Neil Brenner, Jamie Peck and Nik Theodore, ‘Variegated Neoliberalization: Geographies, Modalities, Pathways’, Global Networks 10, no. 2 (2010): 182–222.

19 Jamie Peck, ‘Explaining (with) Neoliberalism’, Territory, Politics, Governance 1, no. 2 (2013): 132–157.

20 Manuel Castells, The Power of Identity (London: Wiley, 2011).

21 Amartya Sen, Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny (Delhi: Penguin, 2007).

22 Neil Brenner, Jamie Peck and Nik Theodore, Nik, ‘Towards Deep Neoliberalization?’ in Neoliberal Urbanism and its Contestations: Crossing Theoretical Boundaries, eds. Jenny Künkel and Margit Mayer (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 27–45.

23 Clarence Stone, Regime Politics: Governing Atlanta, 1946–1988 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1989).

24 John Logan and Harvey Molotch, Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

25 Harvey, Limits to Capital.

26 Ibid.

27 Ananya Roy, ‘Ethnographic Circulations: Space – Time Relations in the Worlds of Poverty Management’, Environment and Planning A 44, no. 1 (2012): 31–41.

28 Sen, Identity and Violence.

29 See note 25 above.

30 Jamie Peck, Nik Theodore and Neil Brenner, ‘Postneoliberalism and its Malcontents’, Antipode 41 (2010): 94–116.

31 Oren Yiftachel, ‘The Aleph-Jerusalem as Critical Learning’, City 20, no. 3 (2016): 483–494, 483.

32 Oren Yiftachel, ‘Understanding “Ethnocratic” Regimes: The Politics of Seizing Contested Territories’, Political Geography 23, no. 6 (2004): 647–676.

33 Tom Baker and Pauline McGuirk, ‘Assemblage thinking as methodology: Commitments and Practices for Critical Policy Research’, Territory, Politics, Governance 5, no. 4 (2017): 425–442.

34 Oren Yiftachel and Jonathan Rokem, ‘Polarizations, Exclusionary Neonationalisms and the City’, Political Geography 86, no. 4 (2021):1–3, 2.

35 Yiftachel, The Aleph.

36 Ibid., 485.

37 Ibid., 491.

38 Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet, Dialogues II (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 52.

39 Latour, Assembling the Social, 22.

40 Neil Brenner, David Madden, and David Wachsmuth, ‘Assemblage Urbanism and the Challenges of Critical Urban Theory’, City 15, no. 2 (2011): 225–240.

41 Thomas Bender, ‘Reassembling the City; Networks and Urban Imageries’, in Urban Assemblages: How Actor-Network Theory Changes Urban Studies, eds. Ignacio Farías and Thomas Bender (London: Routledge, 2012), 303–323.

42 Colin McFarlane, ‘Encountering, Describing and Transforming Urbanism: Concluding Reflections on Assemblage and Urban Criticality’, City 15, no. 6 (2011): 731–739, 737.

43 Ibid., 737.

44 See note 28 above.

45 Joana Conill, Manuel Castells, Amalia Cardenas and Lisa Servon, ‘Beyond the Crisis: The Emergence of Alternative Economic Practises’, in Aftermath: The Cultures of the Economic Crises, eds. Manuel Castells, João Caraça, and Gustavo Cardoso (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 210–248.

46 Yiftachel and Ghanem, Ethnocracy, 649.

47 Based on Yiftachel and Ghanem, Ethnocracy, 650.

48 Ibid., 649, italics authors original.

49 Annika Björkdahl and Ivan Gusic, ‘The Divided City – A Space for Frictional Peacebuilding’, Peacebuilding 1, no. 3 (2013): 317–333.

50 Oren Yiftachel, ‘Theoretical Notes on Gray Cities’: The Coming of Urban Apartheid?’ Planning Theory 8, no. 1 (2009): 88–100.

51 Emma van Santen, ‘Identity, Resilience and Social Justice: Peace-making for a Neoliberal Global Order’, Peacebuilding (2021): 1–22, 15.

52 Slavoj Žižek, Violence: Six Sideways Reflections (London: Profile Books, 2008).

53 Richard Caplan, Richard, Measuring Peace: Principles, Practices and Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

54 Caplan, Measuring Peace, 27.

55 Karin Dyrstad, Kristin M. Bakke and Helga M. Binningsbø, ‘Perceptions of Peace Agreements and Political Trust in Post-war Guatemala, Nepal, and Northern Ireland’, International Peacekeeping (2021): 1–26.

56 Caplan, Measuring Peace.

57 Žižek, Violence.

58 Cummings, E. Mark, Christine E. Merrilees, Alice C. Schermerhorn, Marcie C. Goeke-Morey, Peter Shirlow, and Ed Cairns, ‘Testing a Social Ecological Model for Relations between Political Violence and Child Adjustment in Northern Ireland’, Development and Psychopathology 22, no. 2 (2010): 405–418.

59 Waterman and Worrall, Ibid., 567.

60 Ibid., 574.

61 Hills, Policing Post-Conflict Cities.

62 Glawion, The Security Arena.

63 Ash Amin, ‘Telescopic Urbanism and the Poor’, City 17, no. 4 (2013): 476–492.

64 Emma Elfversson, Ivan Gusic and Marie-Therese Meye, ‘The Bridge to Violence – Mapping and Understanding Conflict-related Violence in Postwar Mitrovica’, Journal of Peace Research (2023): 00223433221147942.

65 Ibid.

66 Uppsala Conflict Data Program, ‘Northern Ireland’, UCDP Conflict Encyclopedia: www.ucdp.uu.se, Uppsala University.

67 Andrew Field, Discovering Statistics (London: Sage, 2017).

69 Gusic, Contesting Peace.

70 Field, Discovering Statistics.

71 Carol Gallaher and Peter Shirlow, ‘The Geography of Loyalist Paramilitary Feuding in Belfast’, Space and Polity 10, no. 2 (2006): 149–169.

72 Gavin Hart and Camilo Tamayo Gomez, ‘Is Recognition the Answer? Exploring the Barriers for Successful Reintegration of Ex-combatants into Civil Society in Northern Ireland and Colombia’, Peacebuilding (2022).

73 Kit Rickard and Kristin M. Bakke, ‘Legacies of Wartime Order: Punishment Attacks and Social Control in Northern Ireland’, Security Studies (2021): 1–34, 5.

74 Gallaher and Shirlow, Loyalist Paramilitary.

75 Ana Arjona, Rebelocracy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

76 Rickard and Kristin, Legacies of Wartime, 5.

77 Ibid., 5.

78 Jacqueline Parry and Olga Aymerich, ‘Reintegration of Ex-combatants in a Militarized Society’, Peacebuilding (2022).

79 Brendan Murtagh, Social Economics and the Solidarity City (London: Routledge, 2019).

80 See note 74 above.

81 Gladys Ganiel, ‘Ex-combatants and Post-liberal Peacebuilding in Northern Ireland: Challenging Cultures of Militarism’, Peacebuilding 8, no. 3 (2020): 344–362.

82 Waterman and Worrall, Spinning Multiple Plates.

83 Brendan O’Leary and John McGarry, The Politics of Antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016).

84 Marisa McGlinchey, Unfinished Business: The Politics of ‘Dissident’ Irish Republicanism (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019).

85 Murphy and Evershed, Contesting Sovereignty.

86 James Worrall, ‘(Re-) Emergent Orders: Understanding the Negotiation(s) of Rebel Governance’, Small Wars and Insurgencies 28, no. 4–5 (2017): 709–733.

87 Hadrien Herrault and Brendan Murtagh, ‘Shared Space in Post-conflict Belfast’, Space and Polity 23, no. 3 (2019): 251–264.

88 Ibid.

89 Ophélie Véron, ‘Neoliberalising the divided city’, Political Geography 89 (2021): 1–12, 4.

90 See note 69 above.

91 John Moriarty, David Wright, Dermot O’Reilly and Allen Thurston, Economic Opportunities, Occupational Class Status and Social Mobility in Northern Ireland: Linked Census Data from the Northern Ireland Longitudinal Study (NILS) (Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast, 2017).

92 Laurent Gayer and Sophie Russo, ‘”Let’s Beat Crime Together”: Corporate Mobilisations for Security in Karachi’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 46, no. 4 (2022): 594–613, 611.

93 Dominic Abrams and Milica Vasiljevic, ‘How does Macroeconomic Change Affect Social Identity (and vice versa?): Insights from the European Context’, Analysis of Social Issues and Public Policy 14, no. 1 (2014): 311–338.

94 Ibid., 328.

95 Brendan Murtagh, Sara Ferguson, Claire Lyne Cleland, Geraint Ellis, Ruth Hunter, Ruibing Kou, Ciro Rodriguez Añez, Adriano Akira Ferreira Hino, Leonardo Augusto Becker and Rodrigo Siqueira Reis, ‘Planning for an Ageing City: Place, Older People and Urban Restructuring’. Cities and Health 6, no. 2 (2022): 375–388.

96 Tim Glawion, ‘Cross-case Patterns of Security Production in Hybrid Political Orders: Their Shapes, Ordering Practices, and Paradoxical Outcomes’, Peacebuilding 11, no. 2 (2023): 169–184, 175.