ABSTRACT

Streets function as the place for interaction and communication, transportation, social and commercial activities for the general public. The concept of ‘complete street’ is gaining popularity worldwide. This study has assessed the current conditions of various functional streets’ categories in selected neighborhoods in Riyadh to examine the applicability of complete streets concept on streets within and outside neighborhoods. Recent policy shift in Saudi Arabia includes huge government outlays for public transportation, humanizing neighborhoods, promoting walking as a healthy lifestyle and rising fuel prices would create a positive atmosphere for the implementation of complete streets’ concept. Reclaiming streets to all users would be an important objective especially in cities that have been characterized as auto-dependent for decades. There is a need to reprioritize community development objectives for a more sustainable and livable environment.

Introduction

The complete streets concept is defined as streets’ design that can safely accommodate all transport modes for all segments of the society (Smart Growth America, Citation2012). It also aims to achieve other community objectives that are related to the environment, social integration, healthy lifestyle, entertainment and economic prosperity (Anderson et al., Citation2015; LaPlante & McCann, Citation2011; Smart Growth America, Citation2016; Shu, et. al., Citation2014) Litman, Citation2014. There have been numerous attempts to devise new and innovative policies to ameliorate the staggering transportation problems faced globally. Most of these policies are designed to emphasize the efficient utilization of Transportation Demand Management (TDM) and Transportation Supply Management (TSM) solutions. The ultimate goal of these policies is to curtail the continuous dependence on automobile travel within cities. Since the emergence of the automobile, policies were designed to ease vehicular travel within cities at different urban levels, such as at the city, district, and neighborhood levels. These policies have resulted in overwhelming automobile trips, traffic congestion, reduction in traffic safety, unsustainable energy use, increased air pollution and diminished economic growth, among others (Al-Mosaind, Citation2007). A study by Carlson et al. (Citation2017) indicated that only 25% of municipalities had a proper street policy.

Context sensitive design concepts along with differential techniques must be developed to ensure the implementation of the complete streets concept (McCann, Citation2008). The resolutions passed by city councils play a significant role in directing transportation agencies towards considering the needs of their users (McCann & Rynne, Citation2005). For instance, Bakersfield implemented the complete streets concept within communities, through strategic approaches aimed at the development of stronger networks (George, Citation2013). Failure to implement proper and innovative policies to provide efficient mobility options may exaggerate the current transportation problem. It is the responsibility of city planning departments to work alongside community members for the achievement of complete street goals, through devising comprehensive plans (Plummer, Citation2011).

During its relatively short history of modern development, the city of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia has grown from a small, organically developed city to a modern mega-city. Its population has grown from less than one million inhabitants in the mid-1970s to more than 6 million in 2017 (Al-Hathloul, Citation2017). The city is characterized by fast population growth, uncontrolled urban sprawl and total dependence on automobile travel for local and city-wide trips. Its first Master Plan done by Doxiadis Associates in the early 1970s was built on the automobile phenomenon and horizontal expansion to accommodate population growth (Al-Hathloul, Citation2017). No clear measures in the Plan to encourage or accommodate other modes of travel at any of the city’s levels.

Consequently, Riyadh is facing a mounting level of traffic congestion on most of its road network. In addition to traffic problems and pollution, a heavy social cost represented by the high number of car accidents, resulting in one of the world’s highest rates in death and casualties (Al-Mosaind, Citation2007). The absence of credible public transport system, a network of pedestrian pathways and suitable infrastructure for non-motorized means of travel has augmented the transportation problem. Local and major streets are designed solely to accommodate automobile users’ needs.

The city however has seen some modest effort to tackle this issue. Even though there are no streets designed nor implemented to accommodate all transport modes’ requirements and act as a place for social interaction and economic vitality, Riyadh has seen various attempts to encourage walking by retrofitting or constructing new walkways around major city landmarks; such as, public facilities, neighborhood parks and major commercial streets. These projects were designed to achieve multiple objectives related to healthy lifestyles, social interaction and city beautification. A prominent example is Al-Tahlia Street in the upscale community of AlSulaimaniah, situated at the north of Riyadh. The municipality retrofitted the street to encourage walking and social interaction by widening sidewalks, thus reducing the space allocated for vehicular movement and parking. Nonetheless, these projects are fragmented, spread randomly around the city and do not lead to a complete network.

Theoretically, the design of complete streets, tailored to accommodate all modes of travel, would enhance balanced mobility patterns in cities and neighborhoods. It would encourage the use of more efficient modes; such as, walking and bicycling, enhanced public transport potential and increased safety levels for all roadway users (Keippel et al., Citation2017; Litman, Citation2014). These benefits are meant to augment mobility and accessibility for all city residents, especially non-drivers. Additionally, these benefits are aimed at enhancing the economic viability of urban activities and businesses (Litman, Citation2014; McCann, Citation2011). Al-Tahlia project was a success because it increased the attractiveness of its commercial activities and land value, attracted more pedestrians and provided enough space for human interaction (Al Mahmood et al., 2017). Similar small-scale projects have imitated this example of Al-Tahlia street on some commercial and residential streets. However, they fell short of achieving the full spectrum of objectives of the complete streets concept. Instead of implementing dispersed projects around the city, an effective step in this regard lies in the incorporation of the complete streets concept in transportation master plans. This will aid in assuring the needs of all users pertaining to transportation and mobility (Plummer, Citation2011; Sears, Citation2014; Seskin & Gorden-Koven, Citation2013).

Despite the efforts made in areas such as Al-Tahlia Street, there is still a steady decrease in pedestrian-friendly street spaces within Riyadh. The over-dependence of city residents on automobile usage coupled with a dearth in effective street policies aimed at enhancing walkability, have contributed to a decrease in the livability and sustainability scales in Riyadh. Eschewing the use of walking and biking as modes of public transportation have additionally led to a decrease in the health and well-being of citizens. The heavy use of automobiles has contributed to a sedentary lifestyle for many Saudi citizens.

It is often said that the extreme heat and harsh weather conditions in Riyadh could impede efforts to enhance non-auto related trips. Nonetheless, experiences in other world cities with similar weather conditions have shown positive outcomes (Nelson, Citation2015). It is also worth mentioning that harsh weather conditions did not stop some northern European cities (very cold and windy) from accommodating pedestrians and cycling spaces on their roads. Sensible treatment of streets’ furniture to cater for and protect users, integrating road and modal networks and retrofitting and redesigning current and future road network led to an enhanced balance of modal use (Abu Dhabi Municipality, Citation2015; Delbosc, et. al., Citation2018; Nelson et al., Citation2015).

Furthermore, the notion of cultural dependence on automobiles by Saudis needs to be readdressed. Prior to the economic boom in the late 1970s, most Riyadh residents relied on walking and primitive public transportation means to fulfil their mobility needs. Even today, in well-designed universities’ campuses and medical cities, non-automobile dependent traffic can be seen. The vast urban sprawl and intentional public policies to modernize the city by designing it solely for the car have formed the base for the current transportation problem. Working on measures of incentives and disincentives for more sustainable forms of travel could divert gradually this trend of over-dependence on the automobile in the short and long run.

This study explores the applicability of complete streets concept at various city levels in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. When applicable, it will highlight the need for implementing the complete streets concept in the city, so that the continuous dependence on automobiles is reduced. Moreover, the study proposes the redesign of different streets’ functional classification to achieve complete streets’ objectives. Since there are numerous challenges (both physical and cultural) associated with modifying lifelong policies to reduce automobile travel, this study addresses how to overcome such challenges. Lastly, the study builds on current opportunities of roadway design and public awareness and support for other modes of travel to make positive changes towards the implementation of the complete streets concept.

Why complete streets?

Historical development of complete streets concept

The automobile revolution was brought about following World War II, and since then created a new paradigm in transportation planning and engineering. The rapid evolution of automated modes of public transportation has led to the adoption of metro buses, light rail, local and express buses; these have modestly altered the urban landscape and shaped the environment. In their long history in urban development, streets play an important role in the urban scape through their multi-uses that include (IPWEAQ, Citation2010):

Pedestrian traffic, including people with a disability;

Motorized & non-motorized vehicular traffic (bicycles and scooters);

Vehicular parking & loading spaces;

Refuse Collection;

Commercial activities;

Vehicular & pedestrian access to premises;

Street dining;

Community interaction;

Seating;

Play & entertainment;

stormwater system;

Lighting & utility services;

Public transport shelters;

Micro-climate mitigation measures;

Streetscape treatment (soft & hard);

Street art and Signage

The concept of complete streets was initiated in the early 1970s in Oregon, which was the first complete streets-like policy in the United States. The policy required new or rebuilt roads to accommodate bicycles and pedestrians and required state and local governments to fund pedestrian and bicycle facilities in the public right-of way (Oregon Department of Transportation, Citation2011). Later, more than 16 additional state legislatures adopted Complete Streets laws (Smart Growth America, Citation2012). In 2010, the U.S. Department of Transportation issued a policy statement on bicycle and pedestrian accommodation in support of complete streets concept in federal-aid transportation projects. It also encouraged community organizations, public transportation agencies, and state and local governments to adopt similar policies (U.S. Department of Transportation, Citation2010).

The popularity of automobiles inspired many communities in the US and other nations to facilitate easy and fast automobile access to destinations. Automobiles became the centerpiece of transportation, infrastructure and land use policies in most cities worldwide. However, the complete streets’ policy is gaining rapid momentum and popularity globally (Nelson, Citation2015). Nearly 500 jurisdictions in the US have adopted a complete streets policy (Car Free America, Citation2017). Worldwide, cities and nations are embarking new transportation policies that reflect or imitate the US example. For instance, Australia is launching smart streets policy while Singapore is working on policies that promote multimodal streets. Both policies resemble the complete streets concept (Delbosc et al., Citation2018; Ho & Isaac, Citation2018). Other examples are observed in Mexico, Brazil, Turkey and India (Sharpin, Welle, & Luke, Citation2017). Some of US cities passed legislation enacting complete streets policies into law, others implemented their policies by executive order or internal policy, and the rest either passed non-binding resolutions in support of complete streets or created transportation plans that incorporated complete streets principles (Smart Growth America, Citation2012). It is worthy to note here that many of the above-mentioned cities have weather conditions like Riyadh’s and many of their citizens also have a similar car dependency problem.

Mobility vs. accessibility

The notion of mobility versus accessibility has dominated road design standards in many cities. Road functional classification divided city streets into three or four categories; major and/or minor arterial, collector and local (AASHTO, Citation2004). Streets that are classified as arterials are intended to provide mobility to different parts of a city. The design of these roads emphasizes operating speed and traffic capacity (LaPlante & McCann, Citation2011). It means that more emphasis is required on access control for various urban activities. Meanwhile, collector streets provide mobility both within and between neighborhoods; and at the same time, provide access to urban activities like commercial facilities and homes. Finally, local roads are designed to provide direct access to homes and shops with very limited mobility functions. These classifications rely heavily on accommodating automobiles and trucks and overlook the more efficient means of travel such as public transportation, bicycling, and walking (Burden & Litman, Citation2011; LaPlante & McCann, Citation2011). The principles of complete streets consider such requirements of mobility and accessibility not only for automobiles, but also for other modes of travel.

Road space requirements

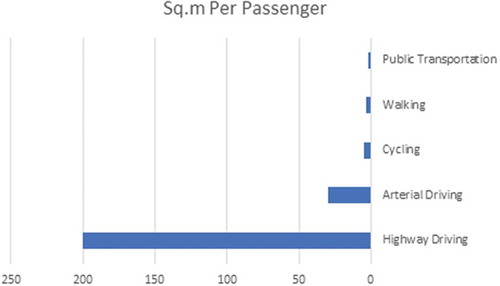

Various modes of travelling require different space arrangements in cities. By far, automobiles consume the highest space requirements in terms of driving corridors and parking. shows that in US cities, highway driving space requirements for solo driving are 100 times that for public transportation, 60 times for walking and 40 times for cycling (Litman, Citation2014).

Figure 1. Road space required for various travel modes (Source: Litman, Citation2014).

Cities need to utilize urban spaces more efficiently. Kevin Lynch in his book ‘Good City Form’ contends that the degree of good city performance relies on its achievement of five dimensions; vitality, sense, fit, accessibility and control (Lynch, Citation1984). In fact, economic efficiency, livability, affordability and environment sustainability objectives are achieved through curtailing automobile use in denser cities and optimizing alternate modes of travel (Al-Mosaind, Citation2007). Complete streets policies incorporate most of these objectives and have become one of the most important planning concepts that promote new directions in urban transportation.

Typical complete streets designs

Complete streets design intends to safely accommodate all modes of travel, users and activities, with design elements varying based on context and project goals. As shown in , they may include pedestrian infrastructure inclusive of sidewalks; traditional and raised crosswalks; median crossing islands; landscaping, and; measures for disabled people (LaPlante & McCann, Citation2011; Litman, Citation2014; National Complete Street Coalition, 2016). Similarly, traffic calming measures are employed to lower speeds of automobiles and define the edges of automobile travel lanes. Accommodations are additionally made for bicycles, such as the development of protected or dedicated bicycle lanes, wide paved shoulders and bicycle parking. Public transit accommodations such as Bus Rapid Transit, bus pullouts, transit signal priority, bus shelters and dedicated bus lanes are additionally of importance.

Figure 2. Typical complete street layout that include provisions for public transportation, bicycling and wider sidewalks (Source: Author, extracted from Car Free America, Citation2017).

The complete streets layout emphasizes an equal treatment of all modes of transportation with a preference for walking and social interaction of residents. These arrangements mean minimizing automobile space in terms of number and width of vehicle lanes and automobile on-street parking. Smart Growth America (Citation2016) has presented complete streets policies to identify the accommodations for citizens. Similarly, the introduction of walkable areas for citizens is also helpful in addressing the specified needs of certain users (Southworth, Citation2005). Therefore, complete streets are designed to assure pedestrian and public transit accommodations (Tennessee Transportation Planning Organization, Citation2009). Similar outcomes presented in the policy of the Toledo Metropolitan Area Council of Governments (Citation2014) have supported the impact of public transport accommodations on revolutionizing transportation systems and the perspectives of citizens.

The case study: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

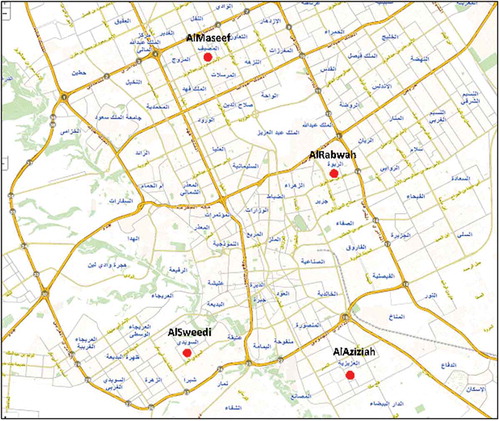

This study was conducted in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and involves a field survey of four categories of streets’ functional classification in 4 matured neighborhoods; that is, neighborhoods that have an age of less than 30 years. The location of the selected neighborhoods has been illustrated in . The four types of functional classifications were local, collector, minor arterial and major arterial. Like Riyadh, the use of these four types of functional classification was seen earlier in a study by Lowry, Furth, and Hadden-Loh (Citation2016) where they were described as the standard employed by most state DOTs and US cities. The use of a field survey was seen in earlier literature, where its significance in the measurement of the influence of complete streets was highlighted. Field surveys are helpful in preliminary testing of the field of interest (Lenker, Maisel, & Ranahan, Citation2016).

The selected neighborhoods are spread out on four city sectors, that are inclusive of north, east, south and west sectors. The streets of these neighborhoods are fully developed and in complete operation. The objective behind including different neighborhoods of Riyadh was to capture locational differences, even though they were subjected to similar street guidelines.

The study employed the field survey approach to capture the layouts of existing streets. Even though this study is not focused on specific streets; rather, emphasis is placed by this study on assuring the presence of different streets’ functional classification. The study used four steps to complete the field survey, listed as follows:

Sightseeing and visual documentation of streets in each neighborhood to assure the process of streets’ selection.

Assessment of activities’ interaction between streets, land uses and users.

Measurement of a typical street’s cross-section in each functional classification type that included pavement width, parking spaces, car & bike lanes, sitting areas, street plantation, traffic calming measures and any other street furniture elements.

Contextual analysis of the selected streets by applying the universal requirements of complete streets concept. These requirements, sketched by the complete streets concept, include wider sidewalks, universal design elements such as curb cuts and ramps, crosswalks with pedestrian refugee, bike lanes and paths, bus lanes and sheltered stations, lower traffic speeds, and landscaping (Litman, Citation2014).

Existing streets’ layouts

All four types of streets were surveyed in the four neighborhoods to capture any locational differences in the application of complete streets concept requirements. The first outcome of the initial assessment of current streets was the striking similarity of four streets’ types regardless of their locations. As shown in , streets’ cross-sections are similar in all four neighborhoods in terms of the distribution of street elements. The differences are seen in two elements: streets’ width and street landscape. The former shows that streets’ width vary according to their physical geography, development patterns and real estate market. For instance, major arterial streets could have a width of 100 or 80 meters in plain geographical neighborhoods and would not exceed 60 meters in neighborhoods with rough terrains. Similarly, minor arterial streets’ width could range between 30 and 40 meters, collector streets range from 18 to 25 meters and local streets could be as low as 6 meters up to 20 meters. Also, the study observes slight differences in streets’ landscaping with more plantation at upscale neighborhoods compared to less affluent ones.

Table 1. Streets’ cross-sections based on their functional classifications in the Four City Neighborhoods.

, , and show the existing layout of four different selected streets’ functional classification (local, collector, minor arterial, major arterial) known to be typical in Riyadh’s neighborhoods. Streets’ design guidelines are unified all over the city. Mayoralty (Amana) of Riyadh is the authorized entity to enact planning rules and regulations where the final approval of the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs is pending (MOMRA, Citation2005). The urban management structure in Saudi Arabia incorporates four levels of authority. The highest legislative and executive layer is the National Council of Ministers headed by the King supported by the Consultative Council (Shura). Both councils are responsible for enacting planning laws and regulations that govern urban development in urban and rural areas. Secondly, MOMRA is responsible for devising national urban planning strategies and structure plans. It prepares national policies, directive and technical guidelines and approves regional and local structure plans (The High Commission for the Development of Arriyadh, Citation2003). The third level is represented by the Riyadh Regional Council and the High Authority for the Development of Riyadh. The former is responsible for approving regional plans, whereas the latter is responsible for preparing and approving Riyadh’s metropolitan strategies and plans (The High Commission for the Development of Arriyadh, Citation2003). The high commission works on city-wide policies and planning regulations. Finally, Amanah (Municipality of Riyadh) is the execution arm of planning rules and regulations. It devises planning guidelines for neighborhoods, streets and buildings. Sub-municipalities in Riyadh have limited roles and capacities as they work merely on monitoring the implementation of these rules and regulations. Therefore, it is of no surprise that the streets’ characteristics resulting from existing guidelines are similar all over the city.

As shown in the four Figures, most of the complete streets’ requirements are not present in existing city streets of Riyadh. shows the outcomes of the assessment process of how existing streets in Riyadh adhere to these requirements. Failure is clearly shown in issues related to traffic safety and traffic calming, provisions for public transportation and biking and suitable greening of sidewalks to shelter pedestrians from extreme weather. Conversely, most major and minor arterial streets enjoy enough street width, presence of pedestrian refugee during street crossing and sometimes curb cuts and ramps. Even though MOMRA published a handbook in 2005 named ‘Design Manual for Sidewalks and Islands in Roads and Streets’, it lacks the provisions for public transportation and biking networks. Moreover, traffic calming measures are not well addressed in the manual, and it only includes provision for the design of speed pumps. Furthermore, the manual does not discuss issues related to environment, livability and economic vitality. It relies on engineering principles that promote engineering efficiency, unified standards and city beautification (Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs (MOMRA), Citation2005).

Table 2. Street assessment of complete streets requirements.

Proposed complete streets sections

– illustrate the possibility of redesigning selected streets in most of Riyadh’s neighborhoods to achieve complete streets’ objectives, without negatively impacting the existing transportation system.

Riyadh’s streets were designed with enough width all over the city, especially in modern areas. Streets’ standards used by the municipality for the last forty years focus on widening them to accommodate the increased space needs of automobiles. Riyadh’s Doxiadis Master Plan, which was approved in 1973, was the starting point of the city’s move towards automobile dependency. It designed future neighborhoods to be car-accessible with almost a complete absence of public transportation (Al-Hathloul, Citation2017). To achieve that, the city worked on widening existing roads, developing high speed expressways penetrating the city old quarters and most importantly adopted land subdivision regulations that were tailored only for the automobile.

Although it was deemed necessary, changing these practices to a more sustainable and balanced form of development could prove to be a tough task. As shown in above Figures, the complete streets layout emphasizes the equal treatment of all transport modes with a preference for walking and social interaction of residents. The latter is severely lacking in most Riyadh’s neighborhoods, since they are designed solely for automobile travel. These arrangements mean that automobile space should be minimized with respect to number and width of vehicle lanes and on-street parking. Furthermore, the complete streets’ layout should aim to reduce vehicular speed, so that the streets are made safer for both residents and businesses. In collector and arterial streets, the proposed street layout provides for sufficient and safe space for bikers and public transportation users. Finally, the new concept provides sufficient room for human interaction of road users and commercial facilities, so that urban livability is enhanced.

Discussion

The results obtained from the field survey indicated that Riyadh’s existing city streets do not comply with the requirements stipulated by complete streets policies. Specifically, failure was noted pertaining to traffic safety and traffic calming, provisions for public transportation and biking and suitable greening of sidewalks for sheltering against harsh weather. This was reflected in earlier studies by Alabdullah (Citation2017) and Kala and Martin (Citation2015), which discussed the detrimental effect of street widening on the ability of citizens to walk or bike in Dammam and Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Alabdullah’s study further discussed a significant dearth in public infrastructure facilities and a loss in the environmental quality of street space. In fact, results of the study found that the primary reason attributed to the decrease in walking or biking lay in the high temperatures and humidity levels present in this geographical region. Therefore, future street designs should emphasize the importance of sidewalk greening; which was found to be severely lacking in most Saudi cities.

Alabdullah study (Citation2017) suggested the implementation of urban wind towers on streets to increase the thermal comfort experienced by pedestrians. These help in reducing heat stress in outdoor environments and in elevating the comparatively low wind velocity within urban environments (Alabdullah, Citation2017).

In Riyadh with its arid-hot environment, there is a need to adopt variety of measures to increase the comfort zone of pedestrians and bikers in city streets. Those measures coincide with complete streets concept requirements and advanced them regardless of locational differences. They include the following:

provide shades by trees, buildings and artificial covers for streets and walkways.

Construct cool air towers in selected streets’ locations such pedestrian refuges’ areas and intersections.

Use water coolers (sprays) in some walkways to reduce the effect of heat and dry winds.

Enhance neighborhood and street designs to reduce walking distances to public facilities, residents’ activities and public transportation stops and stations.

Reduce waiting times for traffic lights for pedestrian’s street crossing.

Use weather-friendly (heat-reduction) street pavements and pedestrian furniture.

A convenient and an appropriate choice of these measures (economically and visually) would be implemented considering the function of the street and the facilities located on it. These measures would certainly help a good percentage of neighborhood residents to use walking in shorter trips to streets and neighborhood facilities. Also, they will encourage many residents to walk to nearby public transportation stops and metro stations once become operational in couple years.

The notion of cultural dependence of Saudis on automobiles may not hold forever. People make rational decisions about their travel behavior. When automobile travel become difficult or unattainable due to excessive congestion time, cost or lack of convenience, complete streets could provide a sensible alternative to encourage people to use other modes of travel. In additions to the drastic increase in oil prices in Saudi Arabia, the commencement of the comprehensive public transportation network in Riyadh in a couple years would create a new city development paradigm that could alter decades of inefficient development patterns. The new Riyadh would be more sustainable, humane, and efficient not only in its transportation network but also in its development patterns. Additionally, the introduction of this new modern and convenient public transportation system would help to alter people’s perception of public transport and open the way for a wider acceptance of other modes of travel such as walking and biking. Residents in areas near and around metro stations would consider metros and express buses a better option compared with increased traffic delays in major roads and limited parking spaces around major facilities.

The question of street retrofitting in line with complete streets requirements is a very challenging one. Certainly, there is no ‘one design fits all’ (Tennessee Transportation Planning Organization, Citation2009). The most significant drawback of existing guidelines of streets’ design and development is its generalization to all city sections. Logically, different city neighborhoods could have different development patterns and requirements that necessitate flexible and innovative guidelines. Flexibility in street design should consider overall city form and structure through reprioritizing users’ needs, so that the community objectives are achieved. In some areas, the need to ease and accommodate automobile traffic may force communities to minimize, rather than eliminate, walking space for pedestrians. Conversely in other areas, road design may promote walking and bicycling at the cost of easing vehicular travel; thereby, resulting in the need for planned traffic congestion to lure people away from using their automobiles. Complete streets principles emphasize the need to make existing and future streets accommodative to all; nonetheless they do not mean that there are no other factors, which could affect the ultimate design of streets. Factors such as right-of-way, existing improvements, existing and future land uses, community desires, available budget, parking requirements and utilities are significant factors in this context (Hui, et al., Citation2018; Tennessee Transportation Planning Organization, Citation2009).

The complete streets layout indicated that walking should be emphasized as the preferential mode of transportation over automobile use by minimizing the width and number of available vehicle lanes and on-street parking. Additionally, the street layout should be such that vehicular speed is decreased greatly, making the streets safer for residents and businesses (Kale & Martin, 2018). In this respect, a study suggested that street designs in Riyadh should incorporate a greater use of speed bumps, street signals, roundabouts and curb extensions (Ledraa, Citation2015). Such actions can be a major step in improving transportation network performance and enhancing city livability.

Various opportunities currently support the implementation of complete streets concept. With respect to its urban context, Riyadh is entering a new transportation era after the adoption and the commencement of one of the largest public transportation projects in recent history, costing nearly $22.4 billion. The project is estimated to be fully operational by 2021. Further, Saudi cities can afford the gradual transformation of their streets and public plazas to fulfil complete streets requirements. The Saudi government generously fund municipalities to achieve their goals for enhancing the city’s well-being and providing innovative solutions to urban problems. The government has allocated nearly 14 billion US dollars in 2018 budget for municipal services. Municipalities can allocate some of these projects to gradually fund street retrofitting based on their importance to the transportation network.

However, the power of the automobile culture and beneficiaries could be an impeding factor to pro-pedestrian policies that may lead to the decrease of automobile use in Saudi cities. Furthermore, there is no current success story of complete streets policy in Saudi cities to comfort public officials and city residents on its potential success. The fear of failure could be an impeding factor for the adoption of complete streets policies since it involves spending money to retrofit current streets with no guarantees for success.

The subsequent policy shift to promote the use of new buses and metro networks coincides with complete streets principles. New guidelines are in the preparation stage for areas near the new public transportation stations, that call for applying transit-oriented development (TOD) principles. Both TOD and complete streets concepts share similar guidelines that aim to enhance transportation mode balance, walkability and livability. Furthermore, the existing large width of current streets at the four functional classification categories allow for sufficient redesign of existing road networks to accommodate modal space requirements. The updated Master Plan of Riyadh (MEDSTAR) and the follow-up local plans call for a balanced approach of transportation modal use to curtail the growing transportation problem in Riyadh. Complete streets principles largely coincide with MEDSTAR recommendations and with new developed urban paradigms such as smart growth and new urbanism. However, changing urban policies in most cities could take several years because of the slow public action in non-emergency related issues. Saudi municipalities are slow in devising and implementing new policies because of the lengthy process of review and acceptance by higher authorities such as MOMRA and the national government.

From the societal perspective, there has been an increase in the level of public awareness regarding health and well-being in recent years. Public pressure on municipalities is mounting to enhance walkways and pedestrian boulevards to facilitate walking for movement, health and entertainment purposes. Previous efforts by municipalities like Diriyah, a suburban city at the western edge of Riyadh, showed a clear support from residents to make streets for people, not cars.Footnote1 Riyadh’s Municipality (Amanah) is working on several projects to widen streets around gardens and public parks to allow for more pedestrian space.

However, these projects do not have the transportation dimension since most of these walkways do not serve as transportation links to city and neighborhood facilities. Riyadh’s residents are to a large extent dependent on automobile travel because of the near-complete absence of public transportation modes. Convincing people to eschew the use of cars and use more friendly transportation modes such as walking and biking, among others, needs extensive efforts by authorities. These efforts would rely on incentives and discouragements to lure people away from using their cars. Secondly, existing knowledge in road engineering and planning are set on easing vehicular travel as a de-facto approach to solve transportation problems. Shifting this approach requires re-educating existing and future city planners and road engineers on the objectives and requirements of a balanced model share and thus community objectives of sustainability, livability, and economic viability. Thirdly, the success of complete streets policies relies on widespread public support and participation in urban issues. Unfortunately, this approach is still in its infancy in Saudi Arabian cities. The only form of public participation in urban affairs is present in the form of municipal councils. These councils are compromised from elected and government nominated members from the general society. Unfortunately, these councils still have limited capacities. Finally, there are no community associations or NGOs that could advocate on behalf of residents for complete streets policies. Current potential support of these policies is fragmented and done on an individual basis. The Diriyah municipality example shows clearly that many initiates would fade slowly once there is a change in city management.

Conclusions & implications

Complete streets principles interact largely with new urban development objectives that emphasize the need for sustainable, efficient, environmentally-sensitive and innovative development patterns. The long-standing linkages of land development and transportation decisions highlighted the need for a major shift in the provision of transportation infrastructure especially roads. Roads need to accommodate not only mobility, accessibility and safety of users, but also to achieve sustainable, viable, and livable communities.

The success of complete streets policies lies in linking them to broader urban development policies. There is a need to integrate complete streets initiatives with development Master Plans to ensure the successful implementation of complete streets principles. This will ensure the continuity of such policies in space and time.

Riyadh needs to benefit from world experiences in adopting and implementing successful transportation initiatives. Some Australian cities, Singapore, Turkey, India and Brazil are clear examples for the new move a balanced use of travel modes that rely on policies such as or similar to complete streets concept. Riyadh should be no exception. There is a need to revive existing streets’ network to achieve complete streets objectives and the broader transportation and community objectives. The assessment of existing road network in Riyadh’s neighborhoods shows the possibility of redesigning and retrofitting to achieve complete streets objectives. An incremental approach would encourage small and gradual streets’ retrofitting without disturbing existing residents and visitors and current traffic movement.

The perceived obstacles to this policy shift can be resolved through sensible and sincere efforts by government entities, such as the municipalities, transportation agencies, organizations and residents. There is a need to reprioritize community development objectives to obtain a more sustainable and livable environment. Saudi cities need to change their current practices of transportation decisions and streets’ design. They need to integrate future development patterns with new planning and transportation ideas such as complete streets, new urbanism, smart growth and transit-oriented development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. The author has worked on similar attempts in the city of Diriyah when serving as a Mayor. City residents supported various efforts to make their streets and neighborhoods safe and liveable. Unfortunately, some of these initiaves were put on hold later after management changed.

References

- AASHTO. (2004). A policy guide on geometric design of highways and streets. AASHTO: Washington, D.C.

- Abu Dhabi Municipality. (2015). Abu Dhabi urban street and utility design tool. Retrieved from https://usdm.upc.gov.ae/USDM

- Alabdullah, M. (2017). Reclaiming urban streets for walking in a hot and humid region: the case of Dammam city, the kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

- Al-Hathloul, S. (2017). Riyadh development plans in the past fifty years (1967–2016). Current Urban Studies, 5, 97–120.

- Al Mahmood, M., Scharnhorst, E., Cartensen, T., Jorgensen, G. (2017). Mapping the gendered city: investigating the socio-cultural influence on the practice of walking and the meaning of walkscapes among young Saudi adults in Riyadh. Journal of Urban design, 22(2), 1–20. January 2017.

- Al-Mosaind, M. (2007). Factors Influencing Travel Patterns in A Dynamic City: Arriyadh, Saudi Arabia (Vol.18). Architecture & Planning Journal - Beirut Arab University.

- Anderson, G., Searfoss, L., Cox, A., Schilling, E., Seskin, S., & Zimmerman, C. (2015). Safer streets, stronger economies: complete streets projects outcomes from across the United States. Institute of Transportation Engineers, ITE Journal, 85(6), 29–36.

- Burden, D., & Litman, T. (2011). America needs complete streets. Institute of Transportation Engineers. ITE Journal, 81(4), 36–43.

- Car Free America. (2017). Complete Streets Policies.

- Carlson, S., Paul, P., Kumar, G., Watson, K. B., Atherton, E., & Fulton, J. E. (2017). Prevalence of complete streets policies in US municipalities. Journal of Transport & Health, 5, 142–150.

- Delbosc, A., Reynolds, J., Marshall, W., & Wall, A. 2018. American complete streets and Australian smartroads: What can we learn from each other? Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 036119811877737. Published online June 8, 2018.

- George, S. L. (2013). A complete streets analysis and recommendations. Report for the City of Bakersfield, California. DOI: 10.15368/theses.2013.47.

- The High Commission for the Development of Arriyadh. (2003). Urban management plan. MEDSTAR Final Reports (Vol. 11–13).

- Ho, C., & Isaac, M. (2018). Streets for all: Designing multimodal streets for a car-lite Singapore. Singapore: Center for LiveableCities.

- Hui, N., Saxe, S., Roorda, M., Hess, P., & Miller, E. J. (2018). Measuring the completeness of complete streets. Transport Reviews, 38(1), 73–95.

- Institute of Public Works Engineering Australasia, Queensland (IPWEAQ). (2010). Street Planning and Design Manual. Queensland.

- Kala, B., & Martin, P. (2015). Comprehensive complete streets planning approach. Washington, D. C.: Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting 2015, Paper # 15-1177.

- Keippel, A., Henderson, M. A., Golbeck, A. L., Gallup, T., Duin, D. K., Hayes, S., … Ciemins, E. L. (2017). Healthy by design: Using a gender focus to influence complete streets policy. Women’s Health Issues, 27, S22–S28.

- LaPlante, J., & McCann, B. (2011). Complete streets in the United States. 90th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC, USA.

- Ledraa, T. (2015). Evaluating walkability at the neighborhood and street levels in Riyadh using GIS and environment audit tools. Emirates Journal for Engineering Research, 20(2), 1–13.

- Lenker, J. A., Maisel, J. L., & Ranahan, M. E. (2016). Measuring the impact of complete streets projects: preliminary field testing (No. C-14-58). State University of New York. Research Foundation. Institute for Traffic Safety Management and Research.

- Litman, T. (2014). Evaluating complete streets: The value of designing roads for diverse modes, users and activities. Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

- Lowry, M. B., Furth, P., & Hadden-Loh, T. (2016). Prioritizing new bicycle facilities to improve low-stress network connectivity. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 86, 124–140.

- Lynch, K. (1984). Good city form. Boston: MIT Press.

- Macleod, K. E., Sanders, R. L., Griffin, A., Cooper, J. F., & Ragland, D. R. (2017). Latent analysis of complete streets and traffic safety along an urban corridor. Journal of Transport & Health 8: 15–29.

- McCann, B. (2008). Complete streets: We can get there from here. Institute of Transportation Engineers. ITE Journal, 78(5), 24.

- McCann, B. (2011). Perspectives from the field: Complete streets and sustainability. Environmental Practice, 13(1), 63–64.

- McCann, B., & Rynne, S. (2005). Complete the streets. Planning, 71(5), 18–23.

- Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs (MOMRA). (2005). Design Manual for Sidewalks and Islands in Roads and Streets.

- Nelson, D. (2015). Imagining complete streets for developing Africa. In Energy, Clinmate and Air Quality Challenges: The Role of Urban Transport Policies in Developing Countries, CODATU2015 Conference, Istanbul, Turkey

- Oregon Department of Transportation. (2011). Bike Bill and Use of Highway Funds. Page updated February 4, 2007.

- Plummer, A. (2011). Complete Streets.

- Sears, B. (2014). Incorporating complete streets into transportation master plans. ITE Journal, 84(4), 33–36.

- Seskin, S., & Gorden-Koven, L. (2013). The best complete streets policies of 2012, Smart Growth America.

- Sharpin, A., Welle, B., & Luke, N. (2017). The CityFix: What Make a Complete Street? A Brief Guide. World Resource Institute: Ross Center.

- Shu, S., Quiros, D. C., Wang, R., & Zhu, Y. (2014). Changes of street use and on-road air quality before and after complete street retrofit: An exploratory case study in Santa Monica, California. California Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 32, 387–396.

- Smart Growth America. (2012). Complete Streets Policy Analysis.

- Smart Growth America. (2016). Complete Streets Policies Nationwide.

- Southworth, M. (2005). Designing the walkable city. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 131(4), 246–257.

- Tennessee Transportation Planning Organization. (2009). Complete Streets Design Guidelines.

- Toledo Metropolitan Area Council of Governments. (2014). Complete Streets Policy.

- U.S. Department of Transportation. (2010). Policy Statement on Bicycle and Pedestrian Accommodation.