ABSTRACT

Expatriates constitute 89% of Qatar’s total population, and are becoming important factors in the economic dynamism by satisfying employment sectors. The theoretical framework of this paper is based on Gordon’s theory which distinguishes between migrants: housing streams and employment streams. The objectives are to: 1) Investigate housing distribution for the expatriate population based on governmental regulations for the blue-collar, and housing preferences for the white-collar workers and 2) Develop a recommendation for expatriates’ housing distribution in Doha. The research tools are: 1) Content analysis of recent census data, 2) Questionnaire survey for white-collar workers in different sectors, and 3) Interview with real estate experts to present insights about the expatriates housing distribution in Doha. The paper concludes that housing streams in Doha are dynamic, whereas employment streams are static. The governmental approach shows that a qualitative change in the demographic composition for Doha’s population will take place; namely, white-collar workers would gradually replace blue-collar workers in future.

Background and objectives

Over the recent years, a considerable attention has been paid to the relationship between migration and housing, and how it affects housing typologies and distribution across the city. Migration also has several effects on economic variables in the city. It can create externalities by changing the composition of the population and affecting the real estate industry (Castles, Citation2010; Forstenlechner & Rutledge, Citation2011).

The theoretical framework of this paper is structured based on Gordon’s theory. Ian Gordon (Citation1975) has distinguished between two kinds of migrants: those who are merely changing address (housing streams) and those who are changing employment (employment streams). The two-stream models of migration emphasize the commuting trade-off in terms of housing and employment motives (Lindley, Citation1980). According to Gordon’s theory, migration related to housing streams is mainly associated with housing prices and congestion effects. Migration related to employment streams is mainly associated with employment growth and amenity. This reflects the correlation between housing and employment streams as affecting the economic conditions and spatial distribution of urban densities (Levitt, Citation1998). In this paper, housing streams are analysed based on housing typologies to include economic influences such as housing prices, and housing distribution. Employment streams are analysed based on employment sectors which reflect the employment growth, and employment locations which reveal urban amenity and services.

The terms migration and expatriation seem to be overlapping. Migration can be defined as the physical movement from one geographic place to another, crossing national borders. Expatriation refers to the physical movement to accomplish a job or an organizational-related goal (Peltokorpi, Citation2008; Zabel, Citation2012). Therefore, expatriation implies a movement across different organizations whereas migration is characterized by a movement across geographical borders (Andresen, Bergdolt, & Margenfeld, Citation2012).

Doha has become part of the global, financial, and technological flows which rely on the expatriates and their contribution to urban productivity. In the case of Doha, the mechanism of migration does not exist; instead the government provides expatriation. Expatriates arrive for an international intra-company transfer with an income and benefits packages based on the employment opportunities available in the country (Santos & Postel-Vinay, Citation2003; UN Habitat, Citation2004). The expatriate population is becoming an important factor in managing the economic dynamism by satisfying employment sectors (Baker, Bentley, Lester, & Beer, Citation2016). With respect to the employment motives for the expatriate population in Doha, white-collar and blue-collar workers classification is attempted to implement the two-stream model: housing and employment streams.

Workers are considered to be expatriates if their work duration exceeds one year in a foreign location (Abdul Salam et. al., Citation2014). Expatriates are temporary workers who work in a foreign location under contracts which are of limited duration (Thiollet, Citation2011). The work contracts may be renewed multiple times thus prolonging the stay of the expatriate worker in a foreign country (Fincher, Iveson, Leitner, & Preston, Citation2014). Increasing numbers of expatriate workers are now accompanied by their spouse and/or children, therefore necessitating the need of not only workplace adjustment but also social and cultural adjustment of single and family residence (Babar, Citation2013). The expatriate population is categorized based on employment sectors (blue-collar and white-collar workers). The terms of blue-collar and white-collar are occupational classifications that distinguish workers who perform manual labours from workers who perform professional jobs (Scott, Citation2018).

Population growth has started in Qatar since 1939, where expatriates have flowed to work in oil production and export processes (Baldwin-Edwards, Citation2011; Wiedmann, Salama, & Thierstein, Citation2012). The demographic structure has evolved in which diverse cultures have flowed to Doha creating cultural diversity, and imbalances in terms of gender and age. As the economy flourishes, a continuous requirement for disproportionately large numbers of male workers (blue-collar workers) has taken place.

According to Bel-Air (Citation2017), the percentage of expatriates has constituted 59% of the total population and has increased to 73% in 1986, which is reflecting the continuous growth. During the period from 1986 to 1997, expatriate arrivals were affected by the steady economic growth of Qatar. Since the 2000s, the percentage of expatriates has increased until it reached 89% of the total population in 2017 (Snoj, Citation2017) ().

Figure 1. Population growth in Qatar (Source: Bel-Air, Citation2017; Snoj, Citation2017).

In 2017, the construction sector in Qatar stood out as the main employer for the expatriate population, where 52% of expatriates were recorded as working in construction activities (Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, Citation2017). This is followed by 23% of expatriates employed in the manufacturing sector (). This is due to the construction boom that took place in 2000, in preparation for hosting mega sporting events. The construction boom has continued towards winning the bid for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in 2010 (Diop, Tessler, Trung-Le, Al-Emadi, & Howell, Citation2012; Naithani, Citation2010). Therefore, it can be stated that a total of 75% expatriates are working in industrial activities (construction and manufacturing) in Qatar, which approves the current demographic structure where blue-collar workers are the majority.

Figure 2. Employment sectors, educational level, and social status for the expatriate population in Qatar (Source: Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, Citation2017; Bel-Air, Citation2017; developed by the authors).

In terms of the level of education, 67% of the expatriates have basic education till the secondary schooling level; whereas 13% are illiterate with no formal education. This corresponds to the fact that 69.7% of the total expatriates are blue-collar workers who are manual skilled and don’t require formal education for their work (Bel-Air, Citation2017; Snoj, Citation2017). However, 19% of the expatriates have a university degree, and 1% have higher education. This reflects the minority of white-collar workers who require specialized knowledge and technical experience for their work (). In terms of the marital status, 81% of the expatriates are singles, whereas 19% have their families living in Qatar ().

The distribution of population in Qatar has primarily been confined to the areas well developed in terms of infrastructure, areas along major transport routes, and coastal areas. Among the most populated areas is Doha city which includes the highest population growth, especially in the industrial area and in the fringe areas of Doha municipality (Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, Citation2018). This has made Doha the economic centre of Qatar, which includes most of the mega projects, and considered as the major employment locations. These mega-projects include: New Doha International Airport (NDIA), Education City, The Pearl, Aspire Zone, Qatar University, and the West Bay.

The objectives of this paper are to: 1) Investigate housing distribution for the expatriate population based on governmental regulations for the blue-collar, and housing preferences for the white-collar workers and 2) Develop a recommendation for expatriates’ housing distribution in Doha.

Research strategy

The research is based on an investigation of housing and employment streams for the expatriate population in Doha. The magnitude of expatriation across the years is traced based on the analysis of urban and population growth rates.

From 1987 through 1998, Doha’s development came in the form of an expansion across the north area, and to a lesser extent along the east. By this time, ring roads have evolved and automobiles have been introduced for the first time in Doha (Shandas, Makido, & Ferwati, Citation2017). New building typologies have emerged. Expatriates have started to inflow in response to the rapid urbanization. Since the 2000s, Doha has witnessed 6.6% growth rate in expatriate population (Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, Citation2017). In 2003, the urban development pattern has heavily increased in the centre of Doha and towards the north, west, and south. The city centre has been characterized by overcrowding and a high number of single male expatriates. In 2009, the amount of urban lands have increased mainly in the form of mega-projects along the coast line of Doha. Mega projects are located far from the city centre which drives the rapid expansion and the sprawling land use patterns (Rizzo, Citation2014). In 2013, the urban lands have increased in the northern, western, and southern directions indicating the future direction for urban expansion ().

Figure 3. Urban growth of Doha (Source: Shandas et al., Citation2017).

Shandas et al., Citation2017)

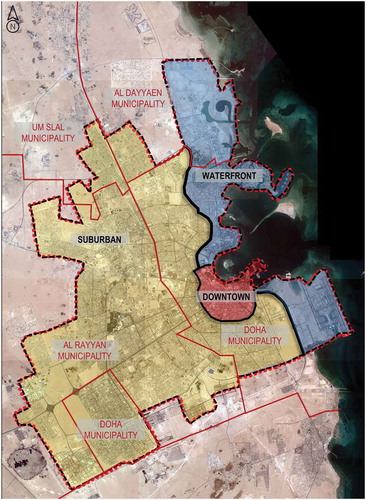

The study area is defined to include the urban limits where housing and employment streams are presented and to include: Doha, part of Al Rayyan, Al Dayyaen, and Um Slal municipalities. The study area is divided into three locations: downtown, suburban, and waterfront. The downtown location represents the old centre of Doha. The suburban location represents all urban areas beyond the downtown and towards the west. The waterfront location represents the coastal line of Doha, except the part attached to the downtown neighbourhoods ().

Figure 4. The study area including the urban limits of Doha city (source: Ministry of Municipality and Environment, Citation2015; edited by the authors).

The used research tools in the study are:

Content analysis of recent census data: is used to analyse blue-collar workers’ housing and employment streams.

Questionnaire survey: is conducted for 388 white-collar workers in different sectors to collect data about their housing and employment streams. The targeted samples were planned for 400 that are approximately 0.018% of the total number of expatriates in Qatar (≈2,200,000), and 388 responds were valid and completed. The samples are distributed across Doha to ensure the coverage of large and various populations. The samples include questions related to personal information, existing housing conditions, and housing preferences.

Interview with real estate experts: is conducted to present insights about the patterns of expatriates housing in Doha.

Analysis of housing distribution for the expatriate population in Doha

This section presents the analysis of housing and employment streams of the expatriate population in Doha. Housing streams are analysed based on housing typologies and distribution. Employment streams are analysed based on employment sectors and locations. The analysis is divided based on blue-collar and white-collar workers, to understand the effects of employment on housing distribution.

Analysis of census data for housing distribution for the blue-collar workers

Content analysis of census data is used to investigate housing and employment streams for the blue-collar workers.

According to Gardner et al. (Citation2013), different housing typologies for blue-collar workers have been surveyed including: a) dormitories; b) porta-cabins; c) stand-alone villas; d) villa compounds; and e) shared apartments. Considering the marital status of the blue-collar workers, the government is seeking to limit their housing typologies to dormitories that are located away from family housing and neighbourhoods (Ministry of Municipality and Environment, Citation2018). In 2010, the government announced a law that effectively banned blue-collar workers from living in certain parts of the city ‘Family Zones’ (Balbo & Marconi, Citation2005).

According to the Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics (Citation2017), the number of housing blocks for blue-collar workers have been decreased significantly in Doha, Al Rayyan and Al Dayyaen municipalities (). This indicates the governmental vision of replacing the existing scattered units all over Doha city with permanent housing typologies in the peripheries for blue-collar workers.

Figure 5. Number of housing blocks for the blue-collar workers within the study area (source: Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, Citation2017).

Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, Citation2017)

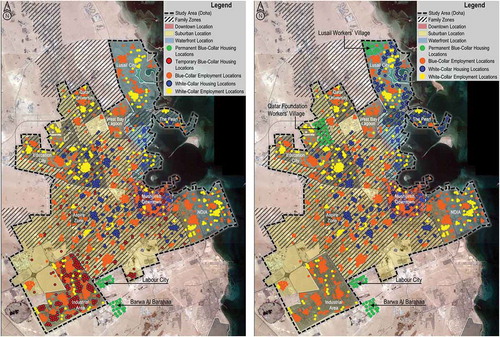

Currently, there are a number of blue-collar workers’ housing blocks distributed randomly across Doha. However, two permanent worker dormitories are approved by the government: Labour City, and Barwa Al Baraha. Two other permanent dormitories are being developed in the west (Qatar Foundation Workers’ Village) and north (Lusail Workers’ Village).

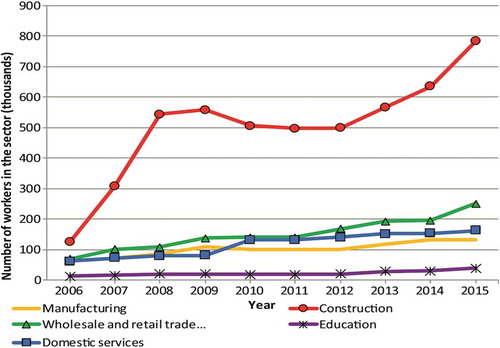

According to Bel-Air (Citation2017), 42% of blue-collar workers are employed in the construction, which corresponds to the FIFA 2022 preparation. The number of blue-collar workers in domestic services and manufacturing has doubled during the years 2006 to 2015. The number of blue-collar workers employed in education and in retail trade has trebled, which reflects the recent orientation of Qatar’s economy towards a knowledge-based economy ().

Figure 6. Employment sectors for the blue-collar workers in Doha (Source: Bel-Air, Citation2017).

Bel-Air, Citation2017)

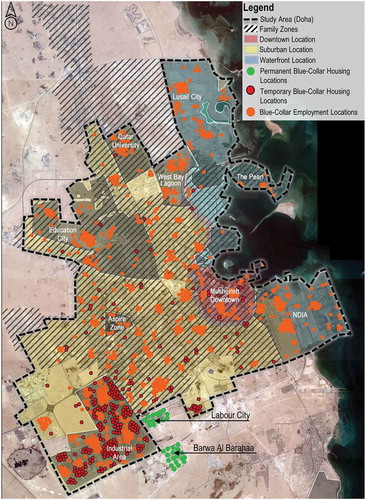

Blue-collar workers are found to be employed in mega projects based on employment hubs. New malls, grand parks, residential developments, educational institutions, office buildings, and service centres are continuously emerging in Doha which suggest the work of many construction labourers. Housing streams of the blue-collar workers are adapted based on the employment streams in mega projects, and based on the government distribution decisions. The mega projects are: Lusail City, The Pearl, West Bay Lagoon, and the New Doha International Airport (NDIA) in the waterfront location; Education City, Aspire Zone, Qatar University, and the Industrial Area in the suburban location; Mushiereb Downtown project in the downtown location. The housing and employments streams of blue collars workers are shown in ().

Questionnaire survey analysis of white collars housing distribution

The questionnaire survey is used to collect data about housing and employment streams for the white-collar workers. Questionnaire samples are 388 white-collar workers across the downtown, suburban, and waterfront locations in Doha. The main objective is to explore the existing housing typologies and locations in order to assess housing distribution in Doha. The questionnaire also considers the housing preferences which give insights about future housing distribution in Doha.

In terms of housing distribution, the white-collar housing locations are distributed throughout Doha city, and are not limited to specific location. According to the analysis of the questionnaire survey, 53% of the white-collar workers live in suburban locations, 33% live in the downtown, and 14% live in waterfront locations (). The analysis shows the preferences of the white collars as follows: 39% prefer to live in waterfront locations, 34% in suburban locations, and 27% in the downtown ().

Figure 8. Existing and housing locations preferences for the white-collar workers in Doha (Source: based on the questionnaire survey).

based on the questionnaire survey)

In reference to the housing typology, the majority of the white-collar workers live in apartments (61%) and villas (35%) (). In terms of typology preferences, 50% of the white-collar workers prefer to live in villas and 24% prefer to live in apartments (). This can be related to the marital status of the white-collar workers in which the villa typology supports the family living.

Figure 9. Existing and housing typologies preferences for the white-collar workers in Doha (Source: based on the questionnaire survey).

In terms of employment streams, 38% of the white-collar workers are employed in the construction sector, followed by 25% in the wholesale and retail trade sector, and 21% in the education sector (). The majority are employed in the private sector which plays a major role in the economic growth.

Figure 10. Employment sectors for the white-collar workers in Doha (Source: based on the questionnaire survey).

based on the questionnaire survey)

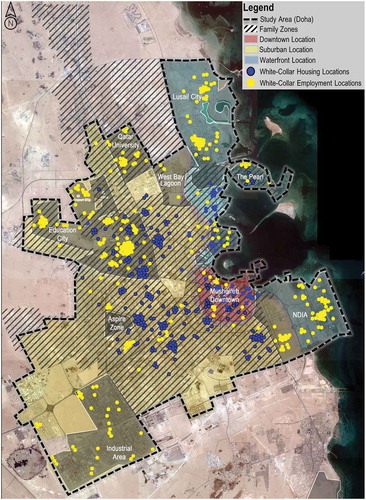

White-collar workers are found to be employed in mega projects such as: Education City, Qatar University, Lusail City, New Doha International Airport (NDIA), Mushiereb Downtown project, Industrial Area, etc. These employment locations are distributed across the suburban location in which most of the white-collar housing is located ().

Perception of the real estate experts

The interview has targeted real estate experts including: developers, architects, urban planners, and academics in the field. The interview aims at understanding the perceptions of expatriates’ housing dynamics in Doha. This leads to investigate the role of government and real estate developers in adapting housing distribution for the expatriate population. The main points and concluding statements of the interview are summarized in :

Table 1. The interview topics, main points, and conclusions (Source: the authors).

After the upcoming sporting events, experts have given emphasis to the selected path of development by the government showing that a qualitative change in the demographic composition for Doha’s population will take place. The number of the total population would not decrease but would change qualitatively in which white-collar workers would gradually replace blue-collar workers. This comes in line with achieving the Qatar National Vision 2030 of transforming the oil-based economy into a knowledge-based economy. The experts have highlighted the fact that recruitment of the right mix of expatriate workforce, protecting their rights, and securing their safety is a governmental priority for the future growth of Doha.

In terms of housing typologies distribution, the real estate experts have highlighted the majority of housing units in Doha municipality are apartments followed by villas. In Al Rayyan municipality, the majority of housing units are villas followed by apartments, while the waterfront areas exemplified in The Pearl Qatar and Lusial City have a wide variety of villas and apartments. Um Slal municipality is still developing in terms of villas, apartments, and other typologies that suit the needs of the nationals, such as traditional Arab houses. The majority of housing units are concentrated in Doha and Al Rayyan municipalities, whereas Um Slal contains the lowest number of housing units as compared to other municipalities. It can be declared that Doha contains the highest rate of Qatar’s population and urban infrastructure where it contains all of the major housing and employment locations.

Experts have referred to the diverse cultural backgrounds of the expatriate population which reflect their diverse preferences in the selection of housing typologies. However, experts have emphasized on the role of the marital status of expatriates which influences their housing decisions in Doha. Based on the employment levels, white-collar workers who are likely to have their families prefer villa typologies in well-serviced neighbourhoods to satisfy their living requirements. This implies a strong preference of housing distribution in suburban and waterfront locations where the concentration of villas typologies is located.

The current pattern of housing distribution for housing units for white-collar workers is mostly connected to their employment locations. Despite the fact that they prefer different typologies to settle in, they choose certain locations to reduce work travel distances to their employment locations. Currently, most of the employment sectors for white-collar workers are located in Doha municipality (downtown). Therefore, it is found to be the most dominant housing units, especially apartment towers. The experts have elaborated on the upcoming plans of white-collar workers’ housing as being re-distributed in downtown and waterfront locations. Mega mixed-use projects such as Mushiereb Downtown project in the centre of Doha and Lusail City in the north of Doha are being developed to provide diverse housing options for the expatriate population satisfying their diverse preferences. Therefore, endless housing options are agreed to be the best approach towards a diverse housing environment for the future of Doha city.

The majority of Blue-collar workers are singles, and their housing is linked to their employment location. In this case, housing preferences do not apply as most of Doha municipality is marked and bounded as family zone, which prohibits single workers’ settlements. Apartment and dormitory-style accommodations are appealed to satisfy blue-collar workers housing and employment requirements based on the distributed mega projects. According to the experts, the existing housing typologies for the blue-collar workers is largely unorganized. In some cases, random accommodations, portacabins, villa compounds, and stand-alone villas accommodate groups of blue-collar workers in the middle of family neighbourhoods.

The blue-collar workers are largely employed in the employment sectors of construction, manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, and domestic services in family homes. Construction sector has the highest number of blue-collar workers, which is mostly concentrated in the Industrial Area, one of the densest employment and housing locations in Doha. Experts emphasized on the existing housing units located in the industrial areas as the dormitory-style accommodations and portacabins for the blue-collar workers, which are temporary settlements. Family houses of nationals, in form of stand-alone and compound villa typologies, accommodate special rooms for the domestic workers, which is considered a permanent accommodation for blue-collar housing. The experts have highlighted the housing blocks of blue-collar workers’ is being organized by the government in specific locations which are close to mega employment locations such as the Industrial Area in the south, Education City in the west, and Lusail City in the north of Doha.

After the upcoming sporting events, experts have concluded the selected path of development by the government, showing that a qualitative change in the demographic composition for Doha’s population will take place. The number of the total population would not decrease but would change qualitatively in which white-collar workers would gradually replace blue-collar workers. This comes in line with achieving the Qatar National Vision 2030 of transforming the oil-based economy into a knowledge-based economy. The experts have highlighted the fact that recruitment of the right mix of expatriate workforce, protecting their rights, and securing their safety is a governmental priority for the future growth of Doha.

Recommendation for expatriates’ housing distribution in Doha

Expatriates constitute the majority of Qatar’s population who move to Doha for better employment opportunities. Population growth had tended both to increase the density in the downtown locations and to cause an outward urban growth. This has been affecting the high concentration of employment locations and housing typologies for both white-collar and blue-collar workers. Housing streams in Doha are dynamic, in the sense that it is dependent on the expatriate population, whereas employment streams are static, which is independent of personal preferences.

Housing streams of the blue-collar workers are unorganized in Doha. However, the governmental policies have been structured to replace the temporary blue-collar workers’ housing blocks with the permanent dormitories that are well serviced and secured. Therefore, the housing streams of the blue-collar workers are profoundly relying on their employment locations (mega-projects). In this manner, the government has approved four major permanent housing locations dedicated only for blue-collar workers; Lusail Worker’ Village in the waterfront location, and Labour City, Barwa Al Baraha, and Qatar Foundation Workers’ Village in the suburban location. The standardized dormitories suit the martial status of the single workers which prospects a more controlled housing distribution based on the governmental regulations.

The housing streams of the white-collar workers are more organized, as housing is dependent on their personal preferences. The current housing typologies and distribution do not meet their preferences. The major concentration of apartments is in the downtown areas while villas are located in the suburban. According to the white-collar preferences, villas are more preferred to be located in suburban and waterfronts, and away from the dense downtown.

Expatriates constitute the majority of Qatar’s population who move to Doha for better employment opportunities. Population growth had tended both to increase the density in the downtown locations and to cause an outward urban growth. This has been affecting the high concentration of employment locations and housing typologies for both white-collar and blue-collar workers. It can be implied that housing streams in Doha are dynamic, in the sense that it is dependent on the expatriate population, whereas employment streams are static, and is independent of personal preferences.

Since white-collar workers would constitute the majority of the expatriate population in the future, housing standardization should be avoided to meet the diverse preferences and needs of the diverse multi-cultures. Endless opportunities should be explored in terms of housing typologies. The existing housing distribution should be adapted based on the expatriates’ preferences through developing an outline for a proper housing in relation to employment locations. Based on the analysed preferences, housing would be distributed mostly in waterfront and suburban locations to meet the diverse preferences of the white-collar workers ( and ).

Figure 12. Cumulative map for the current and assessed housing and employment locations of the blue-collar and white-collar workers in Doha (Source: the authors).

Table 2. Investigation of housing and employment streams for the expatriate populations (Source: the authors).

The investigation reflects the dynamic nature of housing in Doha which is significantly influenced by employment locations. This investigation is considered as a guidance for the government for future housing adaptations.

Conclusion

The paper has presented an investigation of current housing distribution approaches for the expatriate population in Doha. It is based on Gordon’s theory which distinguished between two kinds of migrants: those who are merely changing address (housing streams) and those who are changing employment (employment streams). In the case of Doha, the mechanism of migration does not exist; instead the government provides expatriation. The theory supports the objectives of the paper which are to: 1) Investigate housing distribution for the expatriate population based on governmental regulations for the blue-collar workers, and housing preferences for the white-collar workers and 2) Develop a recommendation for expatriates’ housing distribution in Doha. Three tools have been used: Content analysis of census data related to the blue-collar workers, questionnaire survey for data related to white-collar workers, and interview for real estate experts’ perceptions.

The expatriate population, who constitutes 89% of the total population of Qatar, is becoming an important factor in managing the economic dynamism by satisfying employment sectors. The expatriate population were divided into: blue-collar and white-collar workers. The investigation was based on analysing the housing and employment streams that shape housing distribution in terms of typologies and locations with respect to the employment location.

The housing of the blue-collar workers is concentrated mainly beside mega projects in Doha in the form of worker accommodations and should be standardized by the government as permanent locations along suburban neighbourhoods in the future. The standards that have been issued by the government are very much driven around creating high-quality, safe and secure neighbourhoods, which provide long-term benefits, and can be retrofitted in the future. The housing stream of the blue-collar workers is profoundly relying on their employment locations (mega-projects). The four housing locations are approved by the government: Lusail Worker’ Village in the waterfront location (future), and Labour City (existing), Barwa Al Baraha (existing), and Qatar Foundation Workers’ Village (future) in the suburban location.

The housing of the white-collar workers is relatively distributed across suburban locations. The tangible recognition by the government is that the value of improving workers’ welfare is a direct improvement for Qatar. This is a significant factor in reconsidering housing distribution in Doha. The analysed preferences show that waterfront and suburban locations would require diverse housing typologies to suit the diverse preferences of the white-collar workers. This corresponds to the predicted qualitative change in the demographic composition in population in which white-collar workers would gradually replace the blue-collar workers as Qatar is gradually transforming into a knowledge-based economy. This supports the real estate experts’ perception who have highlighted the need for the skilled expatriates’ workforce who are capable of providing high-quality services in the different employment sectors. The future economic vision for Doha would continuously demand the expatriates’ workforce, especially the white-collar workers.

It was concluded that housing and employment streams of the expatriate population in Doha are generally similar and specifically different. The difference between the blue-collar and white-collar workers is related to the freedom of distribution. The white-collar workers have more control over relocating their housing away from their employment locations. However, blue-collar workers have less control over their housing locations and should be linked to their employment locations. The study has concluded that housing distribution for the blue-collar workers is currently unregulated, but is being seriously restructured by the government in future. Housing distribution for the white-collar workers is more controlled as it depends on personal preferences. This suggests providing endless housing options to successfully accommodate the white-collar workers. A qualitative approach to future housing for the expatriate population considers their preferences and needs.

The significant insights derived from this study will be of importance in revising housing distribution in Doha for the expatriate population. It could provide qualitative data on the issues of housing dynamics in Doha in relation to employment. It has provided baseline information for the expatriate housing distribution and the demographic dilemma in terms of gender and age imbalances and cultural diversity. The authors have conducted the interviews to get the perceptions of real estate market opinion on current and future housing in Doha. This study could also be a review of urban and demographic changes in Doha across the years which have been stimulated by mega sporting events and the governmental visions.

This study can be further developed in a number of ways. Housing distribution for the expatriate population in Doha can be investigated quantitatively, in which a comparable measure of housing and employment streams can solidly guide the recommendations and actions. Another possibility of conducting the study is expanding the findings further to a list of planning codes or guidelines for blue-collar and white-collar workers. This would enable a regulated housing distribution of housing in Doha, and a solid compliance for housing standards.

Furthermore, the 2022 FIFA World Cup is expected to reshape the city of Doha and it requires a cohesive cross-sectoral engagement strategy to be considered by the government as a post-FIFA 2022 assessment. The strategy is not only concerned with housing preferences in the next census but also to identify which typologies contribute to a more integrated, sustainable or efficient city.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdul Salam, A., Elsegaey, I., Khraif, R., & Al-Mutairi, A. (2014). Population distribution and household conditions in Saudi Arabia: Reflections from the 2010 Census. Springerplus, 3(1), 530.

- Andresen, M., Bergdolt, F., & Margenfeld, J. (2012). What distinguishes self-initiated expatriates from assigned expatriates and migrants? A literature-based definition and differentiation of terms. International Journal of Human Resource Management. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.877058.

- Babar, Z. (2013). Labor Migration in the State of Qatar Policy Making and Governance. Center for Migrations and Citizenship (Institut Français des Relations Internationals – ifri). ISBN: 978-2-36567-230-6.

- Baker, E., Bentley, R., Lester, L., & Beer, A. (2016). Housing affordability and residential mobility as drivers of locational inequality. Applied Geography, 72, 65–75.

- Balbo, M., & Marconi, G. (2005). Global migration perspectives: Governing International migration in the city of the South. Italy: Global Commission on International Migration, Università Iuav di Venezia.

- Baldwin-Edwards, M. (2011). Co-Director, Mediterranean Migration Observatory, Institute of International Relations (IDIS) Panteion University, Athens, Labor immigration and labor markets in the GCC countries: National patterns and trends. In Kuwait programe on development, governance and globalization in the Gulf States, 15, P7. London, UK: The London School of Economics and Political Science. Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/55239/1/Baldwin-Edwards_2011.pdf

- Bel-Air, F. (2017). Demography, migration, and labor market in Qatar – Gulf labor markets and migration (GLMM). European University Institute (EUI) and Gulf Research Center (GRC). Retrieved from http://gulfmigration.eu/media/pubs/exno/GLMM_EN_2017_03.pdf

- Castles, S. (2010). Understanding global migration: A social transformation perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(10), 1565–1586.

- Diop, A., Tessler, M., Trung-Le, K., Al-Emadi, D., & Howell, D. (2012). Attitudes towards expatriate workers in the GCC: Evidence from Qatar. Journal of Arabian Studies, 2(2), 173–187.

- Fincher, R., Iveson, K., Leitner, H., & Preston, V. (2014). Planning in the multicultural city: Celebrating diversity or reinforcing difference? Progress in Planning, 92, 1–55.

- Forstenlechner, I., & Rutledge, E. (2011). The GCC’s “Demographic imbalance”: Perceptions, realities and policy options, Middle East Policy, 18(4), 25–43.

- Gardner, A., Pessoa, S., Diop, A., Al-Ghanim, K., Le Trung, K., & Harkness, L. (2013). A portrait of low-income expatriates in contemporary Qatar. Journal of Arabian Studies, 3(1), 1–17.

- Gordon, I. (1975). Employment and housing streams in British inter-regional migration. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 22(2), 161–177.

- Levitt, P. (1998). Social remittances: Migration driven local-level forms of cultural diffusion. International Migration Review, 32(4), 926.

- Lindley, R. (1980). Economic change and employment policy. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 9780333287507

- Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. (2017). Quarterly bulletin population and social statistics: The second Quarter 2017. Retrieved from http://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/General/StatisticalAbstract/2017/population-chapters/Quarterly_Bulletin_Social_and_Population_AE_Q2_2017.pdf

- Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. (2018). Qatar atlas: Qatar population concetration. Retrieved from https://mdpsqatar.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?appid=87f9995a11e34f3bb9bd8d1df290816a

- Ministry of Municipality and Environment. (2015). GIS imagery and archive department. Satellite Imagery of Greater Doha in 2015.

- Ministry of Municipality and Environment. (2018). Family zone houses. Retrieved from http://www.mme.gov.qa/cui/view.dox?id=1181&siteID=2

- Naithani, P. (2010). Challenges faced by expatriate workers in Gulf cooperation council countries. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(1), 98–103.

- Peltokorpi, V. (2008). Cross-cultural adjustment of expatriates in Japan. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19, 1588–1606.

- Rizzo, A. (2014). Rapid urban development and national master planning in Arab Gulf Countries: Qatar as a case study. Cities, 39, 50–57. Elsevier Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2014.02.005.

- Santos, M., & Postel-Vinay, F. (2003). Migration as a source of growth: The perspective of a developing country. Journal of Population Economics, 16(1), 161–175.

- Scott, S. (2018). What is a blue-collar worker and a white-collar worker? Retrieved from http://smallbusiness.chron.com/bluecollar-worker-whitecollar-worker-11074.html

- Shandas, V., Makido, Y., & Ferwati, S. (2017). Rapid urban growth and land use patterns in Doha, Qatar: Opportunities for sustainability? European Journal of Sustainable Development Research, 1(2), 1–13.

- Snoj, J. (2017). Population of Qatar by nationality. Priya DSouza Consultancy, Retrieved from http://priyadsouza.com/population-of-qatar-by-nationality-in-2017/

- Thiollet, H. (2011). Migration as diplomacy: Labor expatriates, refugees, and arab regional politics in the oil-rich countries. International Labor and Working-Class History, 79(1), 103–121.

- UN Habitat. (2004). Globalization and Urban Culture: Expatriates and Multicultural Cities: Problem or Possibility? ISBN: 92-1-131705-3.

- Wiedmann, F., Salama, A., & Thierstein, A. (2012). Urban evolution of the city of Doha: An investigation into the impact of economic transformations on urban structures. METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture, 29(2), 35–61.

- Zabel, J. (2012). Migration, housing market, and labour market responses to employment shocks. Journal of Urban Economics, 72(2–3), 267–284.