ABSTRACT

This article examines the role of architecture and urban planning in shaping connections between European land-based mobility, cities and landscapes. It investigates the development of spaces aiming to link automobility to the everyday experience of European citizens. The planning and funding of the E-road network is related to the promotion of trans-European mobility for commodities and individuals. This attempt to link the different European nations and to overcome their separate plans has reshaped the urban landscape and the territory. The article aims to show how urban planning and architecture play a key role in implementing new types of mobilities promoting environmental sustainability. Taking into account that the EU aims to overcome regimes of petroleum-based mobility and associated architectures, it intends to demonstrate how the land-based transportation of both individuals and commodities in the E-Road network functions as an actor of planetary urbanization. It investigates three kinds of nodes within the E-Road network – the nodes encountered on the E-Roads, those to be found at the gates to cities and the new structures aiming to imitate the urban dimension but proposing a novel articulation of pedestrian and automobile circulation – and relates them to overarching approaches in the design of mobility.

1. Introduction

This article aims to examine the role played by the trans-European network in the formation of new design tools and theoretical frameworks for conceptualizing the role of highways for the articulation of the city-centres with their peripheries. It also attempts to explore how the emergence of a transnational highway system in Europe changed conceptions of the planning and design of cities and regions. The E-road network, which was formed on 16 September 1950, is a numbering system for roads in Europe developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. This network is the European analogue of the so-called Pan-American Highway. As Frank Schipper underscores, in Driving Europe: Building Europe on Roads in the Twentieth Century, ‘[o]n a European level the 1950 Declaration on the Construction of Main International Traffic Arteries created what we today call “E-roads”’. (Schipper, Citation2008, 16). Schipper has also highlighted that ‘the E-roads effortlessly connected Europe from north to south and from west to east’, underlining the fact that they ‘served as a powerful metaphor and visual symbol for international cooperation and European identity’ (Schipper, Citation2008, 190). Despite the fact that on an international scale the Route 66 is more renowned in our collective memory, there are certain highways within Europe that have played a significant role in the evolution of the phenomenon of suburbanization. The article builds on renewed interest in automobility and highways within the social sciences and contributes to studies from multiple disciplines that have focused on the role of the E-Road network in the construction of Europe. It takes into account the fact that the conception of automobile vision differs when shifting from one local, urban and national context to the other. It intends to investigate how urban planning and architecture affect the connections between mobilities, cities and landscapes, taking into consideration different scales and different national contexts, and placing particular emphasis on the connections between suburbs and the city centres. At the centre of the article lie the imaginaries produced by architects and urban planners, and their vision for highways in different national contexts and for their connections to planned new towns. The Declaration on the Construction of Main International Traffic Arteries in 1950 sketched a system that would connect Europe from Scandinavia to Sicily. The construction of a highway system for Europe was already anticipated in 1968.

To understand the complex strategies characterising the role of the E-Road network for the construction of a vision of Europe, one should take into account two layers: a layer concerning the comparison of the conception of highways within different national contexts, including the comparison of designs for the German Autobahn (Zeller, Citation2007), the Italian autostrada (Moraglio, Citation2017), the French autoroutes à péage (Hornsby & Jones, Citation2013), etc., and a layer discussing the designs and spatial imaginaries of the E-Road network. Analysing these layers will allow a better understanding of the tensions between national visions and trans-European urbanization, combining the local with the trans-European dimension, and contributing to a new understanding of the history of Europeanization. An aspect that should be taken into account is the impact of highways on the relation between urban and rural areas. Enlightening regarding this issue is Henri Lefebvre’s categorical statement that 'motorway[s] [brutalize] […] the countryside and the land, slicing through space like a great knife' (Lefebvre, Citation1991, 165)While Autobahn and autostrada systems are interpreted in conjunction with the military purposes they aimed to serve, highways, in general, are understood in relation to the development of modern capitalism.

The main objective of the article is to render explicit that there is a tension between national visions as far as the relationship between land-based mobility and architecture and urban planning is concerned, on the one hand, and some pan-European vision motivating the E-road system, on the other. In order to do so, it builds upon the existing literature on highway culture within different national contexts in order to examine, within a trans-European network, how the imaginaries concerning architecture’s automobile vision evolved within different national contexts, and how these imaginaries were expressed through the emergence of new architectural typologies and new conceptions of the highways. Another aspect that should also be taken into account is Schipper’s remark that ‘[o]vercoming the East-West divide was a central goal for the ECE and its secretary-general Gunnar Myrdal’ (Schipper, Citation2008, 189).

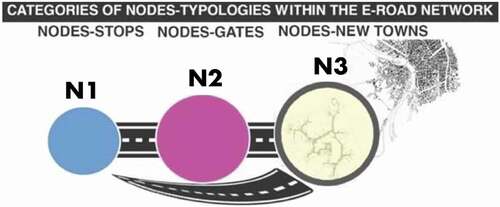

The system of lorries transporting containers from ships in order to enter cities and serve shopping centres is based on the existence of the E-Road Network. The land-based trans-European transport network, and the architectural typologies encountered on it, are part of the port cityscape and the “petroleumscape” supporting it (Hein, Citation2018). My analysis focuses on three typologies, which correspond to three kinds of nodes within the E-Road network, and are expressed within various national contexts that correspond to different European spatial planning systems (Nadin & Stead, Citation2008): a first category of nodes (N1) that corresponds to the nodes encountered on the E-Roads, including service stations, hotels, motels, gas oil stations, and café-restaurants, a second category of nodes (N2) that concerns the nodes encountered at the gates to cities, such as business centres and shopping malls, and a five category of nodes (N3) that includes the new structures aiming to imitate the urban dimension through a renewed mode of articulation between pedestrian and automobile circulation, such as the villes nouvelles in France and the New Towns in the UK, the Netherlands, and Sweden ().

The research methodology adopted is based on the intention to understand the evolution of the relationship between the land-based trans-European transport network, and the architectural typologies encountered on it through the lens of the concept of “infrastructural Europeanism”. In this sense, the E-Road network is understood here as an actor of co-construction of Europe.

2. Infrastructural Europeanism and the E-Road network as an actor of co-construction of Europe

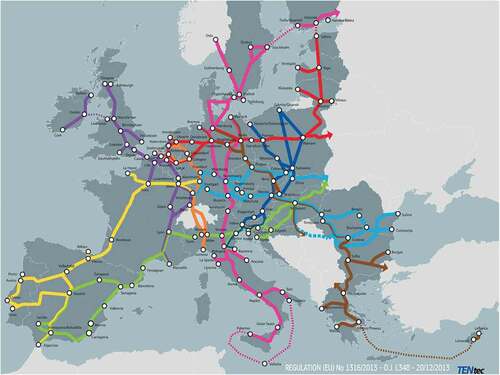

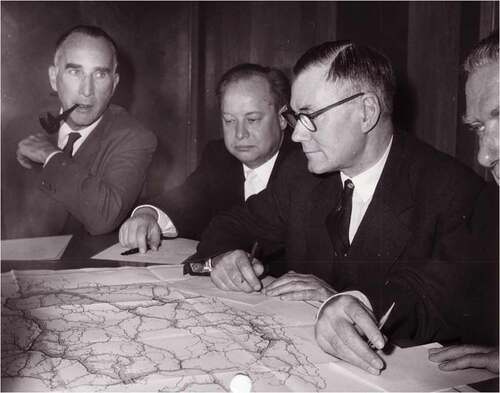

A central notion for better grasping the E-Road network as an actor of shaping visions concerning the co-construction of Europe is that of ‘infrastructural Europeanism’, developed by Frank Schipper and Johan Schot, in their article entitled ‘Infrastructural Europeanism, or the project of building Europe on infrastructures: an introduction’ (Schipper & Schot, Citation2011). Schipper and Schot drew upon Paul Edwards’ ‘infrastructural globalism’, and its emphasis on the integrationist potential of infrastructures, to refer to the co-construction of Europe and its infrastructures (). According to Edwards, ‘infrastructural globalism is about creating sociotechnical systems that produce knowledge about the whole world (…) it is a project: a structured, goal-directed long-term practice to build a world-spanning network’. (Edwards, Citation2010, 25) Useful for understanding the integrationist potential of infrastructures is the fact that ‘[h]istorians have for decades now appreciated the integrationist potential of infrastructures, studying the processes of nation-state formation and how infrastructures have shaped and are shaping globalization’ (Schipper & Schot, Citation2011, 248). Among the first countries that were connected via the E-Road network were Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden and Switzerland. The United Kingdom and the Nordic countries were reluctant towards the E-Road network. The UK, despite being among the most motorized countries in Europe in terms of car ownership, had the least E-roads per square kilometre, in contrast with Benelux, the Alpine countries and Germany, which had a high density (22–35 m/km2), coherent with their status as important transit countries.

Figure 2. Infrastructural Europeanism in practice: studying a 1955 E-road traffic census map. (Left to right) W. Moser (Switzerland), A. Agafonov (USSR) and E.D. Brant (UK) of the Transport Division of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe studying a map on the 1955 Road Traffic Census. Despite Cold War divisions, East and West continued to collaborate on infrastructure-related issues at the European headquarters of the United Nations. UN Photo.

Frank Schipper’s Driving Europe: Building Europe on Roads in the Twentieth Century, Gijs Mom’s ‘Roads without raise: European highway network building and the desire for a long-range motorized mobility’ (Mom, Citation2005), and Pär Blonkvist’s ‘Roads for flow – Roads for peace: Lobbying for a European highway system’ (Blonkvist, Citation2006) are just some of the studies that can help us better the role of the E-Roads in the construction of Europe. The E-Roads serve as a powerful metaphor and visual symbol for international cooperation and European identity (Schot, Citation2010). Some important episodes in the endeavour to co-ordinate mobility on a pan-European scale are the Declaration on the Construction of Main International Traffic Arteries, signed in Geneva on 16 September 1950, which stated that it had become ‘essential, in order to establish closer relations between European countries, to lay down a coordinated plan for the construction or reconstruction of roads suitable for international traffic’,Footnote1 the ‘Declaration on the construction of main international traffic arteries’ (1951) by Edouard Bonnefous – the president of the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the French National Assembly who was a strong advocate of greater European integration – and the foundation of the European Conference of Ministers of Transport (ECMT) in 1953. Already in 1950, Bonnefous had maintained that ‘[t]he co-ordination of transport systems is probably one of the fields in which, in the opinion of all those who have studied the rationalisation of the European economy, it is easiest to advance rapidly and obtain tangible results’.Footnote2 (Henrich-Franke, Citation2012). On 16 August 1950, the French parliamentarian had used these words to launch a plan for the foundation of a supranational European transport organisation.

3. The tensions between national visions and trans-European urbanization

To better grasp the tensions between national visions and trans-European urbanization, one should try to compare the different national contexts, focusing on the following parameters: firstly, the increase or abatement of social seclusion as an effect of highway infrastructure design; secondly, the ways in which architects and urban planners could contribute to promoting ecology-oriented strategies of regional planning, through their practice; thirdly, the use of different categories of roads for different types of mobility; finally, the extent to which highways cross the more central areas of the cities under study. Useful for understanding the planning of roads in France in relation to social seclusion is the fact that ‘in the context of the isolation of the suburban working classes, […] autoroutes à péage, or toll roads […] exclude the poorest’ (Hornsby & Jones, Citation2013, 107). Regarding the use of different categories of roads corresponding to different types of mobility, I could refer to the case of the plan of the Great Aarhus Area in Denmark of the committee that was formed in 1961 and was chaired by the Social Democrat Bernhardt Jensen who was then the mayor of Aarhus. This plan, which was published in 1966, was focused on the urban development until 1980. It included the following five categories structuring the road network: ‘boligveje’ (housing roads), ‘stamveje’ (regular roads), ‘fordelingsveje’ (distribution roads), ‘primærveje’ (primary roads) and ‘motorveje’ (motorways) (Møller, 1966). In the 1966 plan, special attention was paid to envisioning the mobility patterns of the future inhabitants. For this reason, particular emphasis was placed on reflecting upon how road infrastructure could handle the expansion of the region, on the one hand, and the increase in private car ownership, on the other. The everyday commuting of citizens was taken seriously into account. More specifically, the design of the road network was based on the idea that the urban dwellers should mon commute more than 30 minutes. Moreover, special attention was paid to providing a balance between workplaces, housing and recreational areas. The organisation of the road network in the aforementioned five categories aimed to provide this balance. What is noteworthy regarding this plan is the concern of the planners about promoting different types of mobilities on different levels. (Høghøj, Citation2020)

Constantinos Doxiadis aimed to incorporate a concept of mobility into his architectural and urban planning strategies. He employed different concepts to refer to different understandings of mobility corresponding to different historical eras. For the city of the twentieth century, he used the concept of ‘megapolis’, arguing that its main characteristic was the perpetual intensification of mobility flows, which would break the limits of the cities, altering not only their structure but also most importantly their very meaning. Doxiadis was convinced that the age of automobility demanded the founding of new urban types, which would be organized like beehives around multiple centres. (Doxiadis, Citation1962) Another concept of Doxiadis that is useful for analysing the relationship between mobility and urban planning is that of ‘Ecumenopolis’ and its relation to his understanding of highway networks. ‘Ecumenopolis’ started off with the hypothesis that urbanization, population growth and the development of means of transport and human networks would lead to a fusion of urban areas, leading to megalopolises forming a single continuous planetwide city.

Within the Italian context, the intensification of the concern about the notions of ‘città territorio’ and ‘nuova dimensione’ is closely connected to the shift from the interest in the historical city to the concern about territory (Charitonidou Citation2018). During the 1950s and 1960s, this reorientation was expressed through the emergence of a variety of competitions for Centri Direzionali, which was mediating mechanisms between city and territory, and were home to the new oil headquarters. Luigi Piccinato’s work played an important role in the emergence of the typology of the Centri Direzionali.

The concept of ‘città territorio’ appeared in a workshop organized in 1962 by Carlo Aymonino and entitled ‘La città territorio. Un esperimento didattico sul Centro direzionale di Centocelle in Roma’ (Aymonino et al, Citation1964). In the framework of this workshop, a panel on ‘città territorio’ was held with participants Alberto Samonà, Ludovico Quaroni, Carlo Aymonino and Vieri Quilici. The concept of the ‘città territorio’ is more Italian than that of the ‘città regione’, which was more influenced by the American context given that Regions in Italy were officially established in 1970. However, the Regions were included in the Constitution in 1948, and the issues related to regional planning had already been dealt with in the Planning Law in 1942. The intensification of the concerns about the notions of ‘città territorio’ and ‘nuova dimensione’ is closely connected to the shift from the interest in the historical city to the concern about the concept of territory. This reorientation, which took place in the 1950s and 1960s, was expressed through the emergence of a variety of competitions for Centri Direzionali. Centri Direzionali as programs were perceived as mediating mechanisms between city and territory. An important event for understanding how the suburbanization of the post-war Italian cities was conceptualized is the meeting of the Istituto Nazionale Urbanistica of 1959, during which the debate unfolded around the notion of ‘la nuova dimensione’ with main participants Giancarlo De Carlo and Ludovico Quaroni. The emerging and intensified interest in the concept of the ‘nuova dimensione’ was linked to the acknowledgement of the fact that the urban system was in a state of permanent transition. The question of the ‘nuova dimensione’ was also addressed at a conference entitled ‘La nuova dimensione della città’ (‘The New Dimension of the City’) organized in January 1962 by Giancarlo De Carlo in the framework of the Istituto Lombardo per gli Studi Economici e Sociali (ILSES) in the town of Stresa on Lago Maggiore (Istituto lombardo per gli studi economici e sociali, Citation1962). De Carlo defined the new city as a ‘whole of dynamic relationships … a territorial galaxy of specialized settlements’ (Tafuri, Citation1986, 98).

Within the German context, special attention should be paid to the impact of shopping centres on suburbanization. Within the Dutch context, the Dutch Randstad had an important impact on the perception of the city from the car, and on the special character of the post-war suburban living culture in Dutch New Towns (Hein, Citation2020).

Within the French context, particular emphasis should be placed on the analysis of the relationship between the French villes nouvelles project and the new highway network. Despite the fact that the villes nouvelles were conceived in relation to the new regional express network, their connection with the new highway network, which was also being constructed during the same period, was an important component of the project. The villes nouvelles project, which drew upon the lessons of the British and Scandinavian New Towns, was launched in 1965 in order to respond to the French government’s effort to decentralise Paris (Cupers, Citation2014; Merlin, Citation1991). The emergence of an ensemble of new architectural typologies in the villes nouvelles proposals is related to the promotion of the dissociation between pedestrian and automobile circulation, which is very present in the proposal for Toulouse-le-Mirail by Candilis-Jossic-Woods, which started in 1961 and constitutes one of the most iconic projects of the aforementioned team’s experimentation with mass housing in France, and was developed around two core concepts: that of ‘stem’ (trame) and that of ‘cluster’ (grappe).

The dissociation between pedestrian and automobile circulation became possible due to the design of the so-called dalle – a continuous ‘linear street’ connecting Bellefontaine, Reynerie and Mirail, offering ‘a zone of highly concentrated activities and density of collective life’. The design of the dalle was based on the intention to free the pedestrians ‘from the bondage of the automobile’, thereby ‘giving the “street” a new prestige – the street regarded as the primordial function in urban life’. As has been noted by Inderbir Singh Riar, cars arrived ‘only at the perimeter of housing blocks or […] [headed] directly to parking underneath the dalle, a resident simply never had to cross the road to engage the new city’ (Riar, Citation2018, 82). Georges Candilis developed his thoughts about the reinvention of the notion of the street in the case in 'A la recherche d’une structure urbaine', which was published in L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui in 1962 (Candilis, Citation1962).

In a collage by Candilis-Josic-Woods representing the role of the ‘stem’ in their proposal for Toulouse-le-Mirail, we can see that they repeatedly used illustrations of cars (). What is noteworthy here is Candilis-Josic-Woods’s understanding of the street ‘as a morphological structure and a social space of everyday life’, which implies a re-articulation of the relationship between the highways network and urban planning strategies. The fact that Candilis-Josic-Woods treated the street as ‘the structuring device for the urban plan of the whole development, a massive new town for 100.000 inhabitants’ (Cupers, Citation2010, 109) is symptomatic of their endeavour to reshape the connection between urban planning and mobility patterns. Toulouse-le-Mirail was the very first Zone à Urbaniser en Priorité (ZUP) – an administrative formula established in 1960 with the goal to ‘set priorities for government financing and execution of urban infrastructure, as well as for the selection of sites' (Riar, Citation2018, 77).

Figure 3. Candilis-Josic-Woods, Stem collage, 1961. Credits: Shadrach Woods papers, Avery Library, Columbia University.

An aspect that is useful for understanding the specificity of the automobile vision within the Swedish context is the relationship between architecture and corporatism. The automobile, as a physical and perceptual presence, has influenced the relationship between welfare landscapes and social housing in Sweden. During the 1950s and 1960s, when the Swedish social model achieved full employment, promoted consistent growth and maintained price stability, an innovative urban planning model known as the ‘ABC’ modelFootnote3 was developed, aiming to imitate the variety and animation of city life in newly created large-scale suburban towns. Special attention should be paid to the analysis of Vällingby, the first city designed according to this model, and to the transition from the ‘ABC’ model, which was based on a limited use of automobile transport, to a recent tendency towards a renewed role for motorways and their connection to housing design, exemplified in Järvalyftet (Mattsson, Citation2015)

Useful for analysing the specificity of the relationship between highway culture and urban planning is Simon Gunn and Susan C. Townsend’s Automobility and the City in Twentieth-Century Britain and Japan (Gunn & Townsend, Citation2019). Within the British context, the London County Council (LCC), and its Architects’ Department, was responsible for the construction of several projects that changed the image of British cities. Alison and Peter Smithson, who designed Robin Hood Gardens built by the Greater London Council (GLC), which replaced LCC in 1965, addressed the contrast between the new post-war tendencies and traditional society, reinventing the role of architecture within a context where the civic aspect became primordial. They conceived the car as an important means in this endeavour of architecture to respond to the welfare values of post-war society, proving that the emergence of a new understanding of citizens’ sensibilities due to the generalised use of the car in the post-war society should be interpreted in relation to the welfare state (Smithson, Citation1983; Charitonidou, Citation2021).

The link between the different architectural typologies under study is the fact that all of them are closely connected to the highway network. The question of suburbanization and its relation to automobile transport differs from one national context to the other: for instance, within some contexts, such as northern Italy, the existence of medieval and other urban patterns makes it necessary to conceive the network of automobile circulation in a way that extends or contradicts the existing layers of cities, since it is conceived as a new layer superimposed on top of existing networks. In Italy, suburbanization takes place over the existing pattern, extending or contradicting the latter. On the contrary, in other countries such as Sweden, suburbanization takes place in a more tabula-rasa way. Another aspect that should also be taken into account is the fact that shopping centres in France and Germany are more planned than in the case of Italy.

4. Global palimpsestic petroleumscape or planetary urbanization?

The automobile is one of the key actors in the transformation of urban form and planning, significantly affecting the political, environmental, and economic spheres as well as their interactions, but there have been no studies that have examined this impact in a complex and holistic way, placing particular emphasis on the role of urban planning, architecture, and spatial imaginaries. The automobile vision plays a primordial role within the process of suburbanization. To refine the concept of suburbanization, we could develop an understanding of the trans-European network, which is based on a polycentric idea of the urban and suburban realities challenging the dichotomies between the centre and the periphery. The concept of ‘planetary urbanization' suggests an epistemological shift in the field of urban studies, promoting an understanding of urban constellations beyond the polarities characterising the field of urban studies in the early 20th century: it is useful for treating the connections between different national contexts and the relationship between the centres and peripheries and the urban and rural landscapes (Brenner & Schmid, Citation2012). Within such a perspective, the E-Road Network is understood as an actor of planetary urbanization (Brenner & Schmid Citation2012), because it is the spine of planetary land-based transportation of both citizens and commodities.

The automobile vision plays an important role in promoting particular agendas related to the financial benefits of the use of highways for the circulation of commodities within a trans-European network. The role that oil companies play for the construction of spatial imaginaries of automobility and (sub)urban living should also be taken into account since they had an important impact on the historical transformations of the architects and urban planners’ automobile vision during the post-war period. The idea of ‘global palimpsestic petroleumscape’ employed by Carola Hein to examine how ‘petroleumscape […] shapes spatial practices and mindsets’ (Hein, Citation2020, 101) tying ‘commodity and energy flows to diverse spaces’ (Hein & Sedighi, Citation2016, 352). This concept is useful for comprehending the symbolic dimension of the modernisation of roads and the imaginaries of fast mobility, on the one hand, the relationship between architecture, urban planning and logistics concerning the circulation of commodities via the E-Road network, on the other. The logistics of the land-based transport of commodities relate to the endeavours of the countries under study to use architecture and urban planning as agents for constructing imaginaries related to car travel. They also play an important role in shaping imaginaries related to the use of the automobile. Apart from analysing the changing role of automobile transport in processes of suburbanization, one should also try to relate historical perspective to contemporary conditions.

5. Infrastructure and transformation of citizenship and selfhood

Important for realising how geopolitics and infrastructure interact is the relationship between European integration history, the history of European highway infrastructure and the history of automobile imaginaries in Europe. Kenny Cupers and Prita Meier’s remark, in ‘Infrastructure between Statehood and Selfhood: The Trans-African Highway’, that ‘[b]ecause of its scale, cost, and ambition, infrastructure is often thought of as a story of geopolitics, state building, and “big men”’ (Cupers & Meier, Citation2020, 63) is useful for understanding the impact of highway infrastructure – and of buildings erected nearby – on the relationship between citizenship and consumership. In order to reveal the interconnections between infrastructure and transformation of citizenship and selfhood, one should place particular emphasis on demonstrating the relation of highway infrastructure to social issues and identity politics. To do so, concepts drawn from the cultural history of infrastructure, and anthropology could be creatively instrumentalised. For such a purpose one could draw upon an ensemble of recent anthropological studies focusing on the role of infrastructure, such as Dimitris Dalakoglou’s The Road: An Ethnography of (Im)mobility, Space, and Cross-border Infrastructures in the Balkans (Citation2017), and Penny Harvey and Hannah Knox's Roads: An Anthropology of Infrastructure and Expertise (Citation2015).

The aim of this article is to contribute to the studies that aim to investigate the relationship between the evolution of land-based mobility and logistics, and urban and suburban transformations, while adopting an interdisciplinary approach focusing on the interactions between networks of actors. Within the international context, there is an ensemble of professional organizations that explore these issues such as the Congress for the New Urbanism (Swift, Citation2011; Talen, Citation2013). In parallel, researchers such as American urban planner, sociologist Clarence Arthur Perry (1872–1944), who was a staff member of the New York Regional Plan and the City Recreation Committee, started investigating the impact of the advent of the automobile on the shaping of turban fabric in response since the late twenties (Perry, Citation1929, Citation1939; Southworth & Ben-Joseph, Citation2003; Stein, Citation1969). The article is based on the intention to help shaping new interdisciplinary methods to address the role of automobile vision as a tool for the promotion of particular agendas relating to the financial benefits of the use of highways for the circulation of commodities within a trans-European network, and the role of architecture for the construction of imaginaries of the built environment that support automobile vision. These methods should take into account the fact that the E-Road network concerns both individuals and commodities, and that the land-based transportation functions as an actor of planetary urbanization (Brenner & Schmid, Citation2012), focusing on the organization of the land-based trans-European transport network (TEN-T). Special attention should also be paid to the Rhine–Alpine corridor of the TEN-T since it crosses Switzerland ().

6. Around the political agendas behind the pre-eminence of land-based transport

The emergence of new architectural typologies, such as shopping centres and directional centres among others, is related to the political agendas aiming to legitimise the pre-eminence of land-based transport. An analysis of the different architectural typologies at the intersection of automobile and built environments and the variations in architectural typologies encountered on certain important routes of the E-road network could help us shape a new methodology for understanding the infrastructural histories concerning the highways from a trans-European urban perspective and to establish methods permitting going beyond disciplinary studies of mobility and logistics in order to explore the nodes between mobility and locality. The comparisons of the imaginaries implemented in the architectural typologies of nodes within different national contexts give insight about how different types of highways cater to national identities, and how architects and urban planners accommodate them. The replacement of other modes of circulation of commodities by their transportation on tracks is connected to the construction of imaginaries regarding the fetish of speed. As Claire Pelgrims has highlighted, ‘fetish allows a transversal approach, interrelating with different interpretations of automobility infrastructure in mobilities studies’ (Pelgrims, Citation2020, 94). Fetish is understood here as dependent ‘on a particular order of social relations, which it in turn reinforces’ (Pietz, Citation1987, 23, Citation1985). During the postwar years, citizens sought to supplant traditional development patterns with new visions centred on the role of the automobile in daily life. Buildings, roads, nature, policy-makers, urban planners and architects should be understood as actors within a network in continuous becoming. The concept of ‘evolutionary resilience’, which has been examined by Carola Hein and Dirk Schubert, is useful for understanding the dynamic relationship between buildings, roads and nature (Hein & Schubert. Citation2021a; Hein & Schubert, Citation2021b), taking into consideration the fact that ‘[r]esilience has become a buzzword used to describe the capacity of cities to bounce back after disasters’ (Hein & Schubert, Citation2021b, 235).

7. The spatial embodiment of global economic flows

Vincent Kaufmann, in Re-thinking Mobility: Contemporary Sociology, argues that ‘the speed potentials procured by technological systems of transport and telecommunications [can] be considered vectors of social change’ (Kaufmann Citation2016, 99). He employs the term ‘motility’ to refer to the operation of transforming speed potentials into mobility potentials, arguing that ‘[t]he notion of motility allows […] to distinguish social fluidity, from spatial mobility’ (Kaufmann Citation2016, 99). The social fluidity approach, currently present in debates in the social sciences, takes into account the role of ‘transport and communication systems as actants or manipulators of time and space’ (Citation2016, 4), placing particular emphasis on the fact that ‘the automobile […] associates speed and freedom in space and time’. (Kaufmann Citation2016, 101) Particular emphasis should also be placed on the role of mobility in the formation of social positions. In parallel, the shift from the model related to contiguity to that related to connexity is pivotal for understanding the role of the E-Road network within this process of enhancing ‘the interaction of actors by cancelling […] spatial distance’ (Kaufmann Citation2016, 22).

Actor Network Theory (ANT), path dependence theory and the concept of planetary urbanization are useful for better understanding the relationship between the spatial embodiment of global economic flows and the effects of networks of trade and transport, and the relationship between global networks and local transformations. The main characteristic of ANT, originally developed by Bruno Latour, Michel Callon and John Law, is the symmetrical treatment of human, social and technical elements within a system (Latour, Citation2005). The elaboration of methods related to ANT to tackle questions concerning urban studies has already been addressed in Urban Assemblages: How Actor-Network Theory Changes Urban Studies (Cvetinovica et al, Citation2017; Farías, Citation2010; Rydin & Tate, Citation2016). An understanding of highway infrastructure based on ANT implies that highways and architectural typologies encountered in them are understood as active elements of a dynamic urban system. ANT focuses on the interaction between the different actors of the network and is a convenient theoretical framework for studying the intersection of car and built environment, and for interpreting highways, automobiles and architectural and urban assemblages as actors of a dynamic network. ANT is also useful for interpreting mobility policies based on the supremacy of the associations between them, treating highway infrastructure mostly as infrastructure process, and as being in a dynamic state of continuous transformation.

ANT is based on the idea that ‘[o]bjects, tools, technologies, texts, formulae, institutions and humans are not understood as pertains to different and incommensurable (semiotic) realms, but as mutually constituting each other’ (Farías, Citation2010, 3; Farías & Bender, Citation2010). ANT can serve to treat space as one of the agents of the network under study, and path dependence is useful for analysing the transformation of the institutional and epistemological approaches concerning urban planning related to the generalised use of cars and the promotion of highway transport of commodities within a trans-European network (Sorensen, Citation2015). Departing from Carola Hein and Dirk Schubert’s claim that ‘path dependence provides an important way to look at port cities’ (Hein & Schubert, Citation2021b, 390), what I claim here is that path dependence is equally convenient for examining the evolution of highway infrastructure and mobility policies. Taking into account that ‘[u]sing the transformation of the form, function, and location of port infrastructure as the lens for understanding resilience [within a] […] comparative framework […] can provide new insight into the complex intersection between institutional decision-making and spatial development’ (Hein & Schubert, Citation2021b, 391), what I argue is that studying the mutations regarding the form and function of highway networks within a trans-European perspective can contribute to a sharper understanding of the intersections between institutional decision-making processes and spatial development concerning mobility policies within Europe.

Vincent Kaufmann, in Rethinking Mobility: Contemporary Sociology (Citation2016), draws a distinction between the areolar model, the network model, the liquid model, and the rhizomatic model. Taking into account the fact that the E-Road network can be understood as adopting a perspective that combines different aspects of the aforementioned models, the aim is to examine its shaping an approach based on the intention to transform motility into mobility. To understand the different functions of the architectural typologies encountered on the E-Road network in the process of planetary urbanization and in the production of flows of commodities and individuals within Europe, one could compare the different forms taken in different national contexts by the three kinds of nodes (). The latter are as follows: the architectural typologies of intermediary stops on highways (service stations, hotels, motels, gas oil stations, café-restaurants), the architectural typologies encountered at the gates to cities (business centres, shopping malls) and the new urban formations that enhanced suburbanization, contributing to the creation of polycentric entities, such as the New Towns of the welfare states. This categorization of the typologies according to their function within the network of transport of commodities and individuals is useful for understanding the different approaches within each national context vis-à-vis the relationship between the automobile infrastructure and architecture and urban planning. ‘Transnational history’ and its intention to treat the connections between different national contexts as central forces within the historical processes is based on the conviction that ‘the historians must examine the specific relationships that constitute the links between concepts and their fields of emergence and evolution, in parallel with their investigation of the evolution of the concepts under study in order to understand which methods are most appropriate for the study and deepening of the objects of research object’ (Charitonidou, Citation2016, 150).

8. The shift from road to rail networks in Switzerland

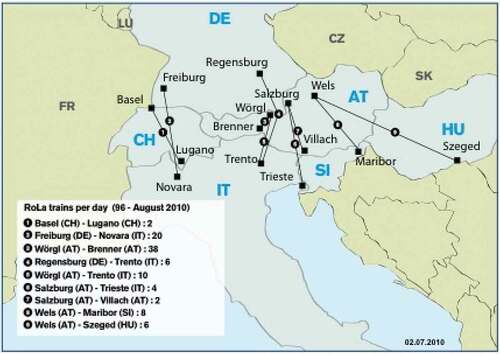

An aspect that is also interesting for better grasping the mobility patterns within the E-Road network is the shift from road to rail networks in Switzerland. The ‘rolling highway’ of Switzerland is a government-subsidized articulation between the E-Road Network and the Swiss railway network, whereby lorries are transferred onto trains in order to cross the Alps(). Gotthard Base Tunnel played an important role in increasing local transport capacity through the Alpine barrier, especially for freight, notably on the Rotterdam–Basel–Genoa corridor, and in shifting freight volumes from trucks to freight trains. Taking into consideration the fact that ‘[t]he shift of goods transport to tracks is as declared, priority goal of the EU’ (Scholl, Citation2012, 118) and ‘[m]odal shift of freight on to rail is […] part of Switzerland’s federal Constitution’ (OECD, Citation2012, 182). In 2010, upon the initiative of the Chair of Spatial Development at ETH Zürich, a strategic EU Interreg Project started with the objective to promote a dialogue regarding the relationship of the railway and spatial development, especially in connection with the North–South Link (Günther, Citation2012, 35). Departing from Felix Günther’s claim that the main objectives of the so-called NEAT project (Neue Alpen Transversale; New Railway Link through the Alps) were the banning of the circulation of commodities from roads, the use of railway infrastructure for their traffic, the reorganisation of routes and railway lines, and the improvement of the accessibility of Switzerland within Europe, one could reflect upon the role of Flachbahn tunnels within the Trans-European network. Flachbahn tunnels, including the Gotthard Base Tunnel, Lötschberg Base Tunnel and the Monte Ceneri Base Tunnel, aimed to reduce environmental pollution and to efficiently connect northern and southern Europe. Switzerland is located at the crossroads of major European transport corridors. This makes the transalpine rail freight services very central in this process of shaping patterns of mobility within a trans-European scale.

Figure 5. Rolling Highway (RoLa) trains per day (August 2010). Source: Christoph Seidelmann, Citation2010, 27.

9. Conclusions

The article presented an ensemble of key insights concerning a multi-layered analysis of the E-Road network and its relation to architecture and urban planning. Its main objective was to make explicit that it is necessary to shape methods aiming at a simultaneous investigation of the architecture of the automobile threshold spaces, the urban planning strategies and the variations of the imaginaries concerning European post-war welfare societies. In order to shape multi-layered methods, one should take seriously into consideration intertwinement of different scales, such as the architectural scale, the scale of urban planning and the territorial scale. In parallel, it is indispensable to take into account how the connection between the suburbs or the periphery and the city centre was treated within different national contexts.

A question that is dominant within the current debates concerning migrant flows is that of whether the term mobility of migration is more relevant. As Sandra Ponzanesi highlights in her article entitled ‘Migration and Mobility in a Digital Age: (Re)Mapping Connectivity and Belonging’, ‘[m]obility studies is an emergent interdisciplinary field that focuses on social issues of inequality, power, and hierarchies in relation to spatial concerns, such as territory, borders, and scales’ (Ponzanesi, Citation2019, 548). Mobility studies are understood as more socially sustainable in the sense that they are considered to relate to a more holistic approach than migration studies. A term that was recently coined by Mimi Sheller to respond to the dilemma of whether the term migration or mobility is more socially equitable is the term ‘mobility justice’ (Sheller, Citation2018). The main idea behind the use of this term is the intention to render explicit that while mobility is a fundamental right for everyone, it is experienced unequally along the lines of gender, class, ethnicity, race, religion and age.

The fictions related to automobility significantly transformed not only the relationship between the city centre and its territory but also the relationships between the different national contexts within Europe. The emergence of new models of daily life related to the model of working and living within a trans-European network contributed significantly to the perception of Europe as an expanding polycentric and dynamic entity. To address the question of the impact of the car on ‘planetary urbanization’ (Brenner & Schmid, Citation2012) in a trans-European perspective, one should examine the role of the E-Road network in suburbanization and its impact on the shift towards the model of the polycentric city. Another question that emerges and is also topical as far as the debates around the relationship between sustainability and mobility patterns are that concerning the mutations in spatial practices and mindsets that will emerge due to the shift from traditional petroleum fuels towards electric cars. Insightful for understanding the shifts concerning the sociocultural dimensions of mobility of the reorientation towards the decarbonization of cities is the recently published issue of Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy (Sonnberger & Graf, Citation2021). Special attention was paid, in the aforementioned issue, to the analysis of the importance of taking seriously the close connection of society, technology, movement and culture.

The article intended to explain why architects and urban planners as visionaries function as agents of the dominant economic and social systems. The design and promotion of road maps handed out at gas oil stations function as agents within this process of constructing imaginaries around the experience of highways and automobile transport. The distribution of free road maps and brochures by oil companies and the creation of networks of gas oil stations played an important role in suburbanization. Relevant for the investigation of the relationship between the generalised use of the automobile and the phenomenon of suburbanization is the fact that ‘[o]il companies have actively promoted the expansion of transportation systems [distributing, on the one hand] road maps designed to entice car users to destinations that were ever farther away’ (Hein, Citation2009), and expanding further the existing networks of gas oil stations, on the other.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Prof. Dr. ir.-arch. Pieter Uyttenhove, Prof. Dr. Kenny Cupers, Prof. Dr. Ir. Carola Hein, Prof. Dr. Vincent Kaufmann, and Prof. Dr. Géry Leloutre for our insightful exchanges about the ideas developed in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Declaration on the construction of main international traffic arteries, 16 September 1950, preamble, copy in registry fonds GIX, file 12.7.1.5–14,627, UNOG.

2. Archives of the Council of Europe, Strasbourg, Consultative Assembly, Second Ordinary Session, Motion recommending the creation of a European Transport Organisation, Doc. 63, 16 August 1950, 1.

3. A referred to Arbete, or work; B to Bostad, or housing; and C to Centrum.

References

- Aymonino, C., Bracco, S., Greco, S., Piccinato, G., Quilici, V., Samonà, A., Tafuri, M., Campos-Venuti, G., De Carlo, G., Samonà, G., Sylos Labini, P., et al, (1964). La Città territorio. Un esperimento didattico sul Centro direzionale di Centocelle in Roma. Leonardo da Vinci editrice, Problemi della nuova dimensione series.

- Blonkvist, P. (2006). Roads for flow - Roads for peace: Lobbying for a European highway system. In V. D. V. Erik & A. Kaijser (Eds.), Networking Europe: Transnational infrastructures and the shaping of Europe, 1850-2000 (pp. 161–168). Science History Publications.

- Brenner, N., & Schmid, C. (2012). Planetary urbanization. In M. Gandy (Ed.), Urban constellations (pp. 10–13). Jovis.

- Candilis, G. (1962). 'A la recherche d’une structure urbaine'. L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui 101, 50–51.

- Charitonidou, M. (2016). Réinventer la posture historique: Les débats théoriques à propos de la comparaison et des transferts. Espaces et Sociétés, 167(4), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.3917/esp.167.0137

- Charitonidou, M. (2018). Between Urban Renewal and Nuova Dimension: The 68 Effects vis-à-vis the Real. Histories of Postwar Architecture, 2, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2611–0075/7734

- Charitonidou, M. (2021). Autopia as new perceptual regime: mobilized gaze and architectural design. City, Territory and Architecture 8(5), 2–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-021-00134–1

- Cupers, K. (2010). Designing social life: The urbanism of the grands ensembles. Positions, 1, 94–121.

- Cupers, K. (2014). The social project: Housing postwar France. University of Minnesota Press.

- Cupers, K., & Meier, P. (2020). Infrastructure between statehood and selfhood: The Trans-African Highway. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 79(1), 61–81. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2020.79.1.61

- Cvetinovica, M., Nedovic-Budicb, Z., & Bolaya, J.-C. (2017). Decoding urban development dynamics through actor-network methodological approach. Geoforum, 82, 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.03.010

- Dalakoglou, D. (2017). The road: An ethnography of (im)mobility, space, and cross-border infrastructures in the Balkans. Manchester University Press.

- Doxiadis, C. A. (1962). Ecumenopolis: Toward a universal city. Ekistics, 13(75), 3–18.

- Edwards, P. (2010). A vast machine: Computer models, climate data, and the politics of global warming. MIT Press.

- Farías, I. (2010). Introduction: Decentring the object of urban studies. In I. Farías & T. Bender (Eds.), Urban assemblages: How actor-network theory changes urban studies. Routledge.

- Farías, I., & Bender, T. (eds.). (2010). Urban assemblages: How actor-network theory changes urban studies. Routledge.

- Gunn, S., & Townsend, S. C. (2019). Automobility and the city in twentieth-century Britain and Japan. Bloomsbury.

- Günther, F. (2012). Corridor 24 Development: Rotterdam – Genoa. In B. Scholl (Ed.), SAPONI - Spaces and Projects of National Importance (pp. 33–35). vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich.

- Harvey, P., & Knox, H. (2015). Roads: An anthropology of infrastructure and expertise. Cornell University Press.

- Hein, C. (2009). Global landscapes of oil. New Geographies, 2, 33–42.

- Hein, C. (2018). Oil spaces: The global petroleumscape in the Rotterdam/The Hague area. Journal of Urban History, 44(5), 887–929. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144217752460

- Hein, C. (2020). The global petroleumscape in the Dutch Randstad oil spaces and mindsets. In W. Zonneveld & V. Nadin (Eds.), The Randstad: A polycentric metropolis (pp. 100–124). Routledge.

- Hein, C., & Schubert, D. (2021a). Resilience, disaster, and rebuilding in modern port cities. Journal of Urban History, 47(2), 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144220925097

- Hein, C., & Schubert, D. (2021b). Resilience and path dependence: A comparative study of the port cities of London, Hamburg, and Philadelphia. Journal of Urban History, 47(2), 389–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144220925098

- Hein, C., & Sedighi, M. (2016). Iran’s global petroleumscape: The role of oil in shaping Khuzestan and Tehran. Architectural Theory Review, 21(3), 349–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/13264826.2018.1379110

- Henrich-Franke, C. (2012). Mobility and European integration: Politicians, professionals and the foundation of the ECMT. The Journal of Transport History, 29(1), 64–82. https://doi.org/10.7227/TJTH.29.1.6

- Høghøj, M. (2020). Planning Aarhus as a welfare geography: urban modernism and the shaping of ‘welfare subjects’ in post-war Denmark. Planning Perspectives Planning Perspectives 35(6),1031–1053. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2019

- Hornsby, D., & Jones, M. C. (2013). Exception française? Levelling, exclusion, and urban social structure in France. In Idem (Ed.), Language and social structure in urban France (pp. 94–109). Routledge.

- Istituto lombardo per gli studi economici e sociali. (1962) 'La Nuova dimensione della città: la città regione: Stresa 19–21 gennaio 1962 (Relazioni). ILSES.

- Kaufmann, V. (2016). Re-thinking mobility: Contemporary sociology. Routledge.

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford University Press.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. Blackwell

- Mattsson, H. (2015). Where the Motorways Meet: Architecture and Corporatism in Sweden 1968. In M. Swenarton, T. Avermaete, & D. van den Heuvel (Eds.), Architecture and the Welfare State (pp. 155–176). Routledge.

- Merlin, P. (1991). Les Villes nouvelles en France. Presses Universitaires de France.

- Mom, G. (2005). Roads without raise: European highway network building and the desire for a long-range motorized mobility. Technology and Culture, 46(4), 745–772. https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.2006.0028

- Moraglio, Massimo. Driving Modernity: Technology, Experts, Politics, and Fascist Motorways, 1922–1943 (New York; Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2017).

- Nadin, V., & Stead, D. (2008). European spatial planning systems, social models and learning. disP - the Planning Review, 172(172), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2008.10557001

- OECD. (2012) . Strategic transport infrastructure needs to 2030.

- Pelgrims, C. (2020). Fetishising the Brussels roadscape. The Journal of Transport History, 41(1), 89–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022526619892832

- Perry, C. (1929). The neighborhood unit: Neighborhood and community planning, regional survey (Vol. 7). Committee on Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs.

- Perry, C. (1939). Housing for the machine age. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Pietz, W. (1985). The problem of the fetish, I. Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 9, 5–17.

- Pietz, W. (1987). The problem of the fetish, II. Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 13, 23–45.

- Ponzanesi, S. (2019, September). Migration and mobility in a digital age: (Re)Mapping connectivity and belonging. Television & New Media, 20(6), 547–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419857687

- Riar, I. S. (2018). Ideal plans and planning for ideas: Toulouse-Le Mirail. AA Files, 63, 62–86.

- Rydin, Y., & Tate, L. (eds.). (2016). Actor networks of planning: Exploring the influence of actor network theory. Routledge.

- Schipper, F. (2008). Driving Europe: Building Europe on roads in the twentieth century. Amsterdam University Press.

- Schipper, F., & Schot, J. (2011). Infrastructural Europeanism, or the project of building Europe on infrastructures: An introduction. History and Technology, 27(3), 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/07341512.2011.604166

- Scholl, B. (ed.). (2012). SAPONI - Spaces and Projects of National Importance. vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich.

- Schot, J. (2010). Transnational infrastructures and the origins of European integration. In A. Badenoch & A. Fickers (Eds.), Materializing Europe: Transnational infrastructures and the project of Europe (pp. 82–112). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Seidelmann, C. (2010). 40 years of Road-Rail Combined Transport in Europe: From Piggyback Traffic to the Intermodal Transport System. International Union of combined Road-Rail transport companies UIRR scrl.

- Sheller, M. (2018). Mobility justice. The politics of movement in an age of extremes. Verso.

- Smithson, A. (1983). AS in DS: An eye on the road. Delft University Press.

- Sonnberger, M., & Graf, A. (2021). Sociocultural dimensions of mobility transitions to come: Introduction to the special issue. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 17(1), 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2021.1927359

- Sorensen, A. (2015). Taking path dependence seriously: An historic institutionalist research agenda in planning history. Planning Perspectives, 30(1), 17–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2013.874299

- Southworth, M., & Ben-Joseph, E. (2003). Streets and the shaping of towns and cities. Island Press.

- Stein, C. S. (1969). Towards new towns for America. The MIT Press.

- Swift, E. (2011). The big roads: The untold story of the engineers, visionaries, and trailblazers who created the American superhighways. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Tafuri, M. (1986). Storia dell’architettura italiana 1944-1985. Giulio Einaudi.

- Talen, E. (ed.). (2013). Charter of the new urbanism (2nd ed.). McGrawHill Education/Congress for the New Urbanism.

- Zeller, Thomas. Driving Germany: The Landscape of the German Autobahn, 1930–1970 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2007).