?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Regardless of the anti-discrimination policies in place, discrimination is still prevalent within the rental housing market. This poses some considerable challenges to potential accommodation seekers. Due to discrimination, securing accommodation by minority groups has become a major challenge as they are most likely to be discriminated against. This study, therefore, sought to assess discrimination in the housing rental market in the Sunyani Municipality, Ghana. Spatially, four communities namely, Nkwabeng, Penkwase, New Town/Tonsuom Estate and Sunyani Area 4 were purposively selected within the Sunyani Municipality for the study. Data was gathered from 173 landlords and 242 tenants using questionnaires and analysed using probit. The probit model showed that household size, ethnicity, marital status, gender, nationality, disability and age of tenants were the main discriminatory factors. Due to the high demand for housing facilities, there is a likelihood for property owners to discriminate against minority groups. Therefore, it is recommended that the government explores avenues to expand public housing delivery through its affordable housing projects to help address the overt or covert practice of discrimination.

1. Introduction

In Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, physiological needs which include shelter (housing) are basic needs that are critical for human lives (Aruma & Hanachor, Citation2017). To this end, housing rights are seen as universal human rights (UN General Assembly, Citation1948) and it has to be provided for without any form of discrimination. In many countries, the provision of housing is a shared responsibility between the government and private individuals with the latter dominating the rental housing market in many countries, including Ghana (Adu-Gyamfi et al., Citation2020). Considering the limited housing stock in Ghana, and the dominance of the private sector in the housing market, there is a tendency for discrimination in access to private housing facilities. The extant literature shows the existence of discriminatory practices of private housing owners and sometimes estate agents (Adu-Gyamfi et al., Citation2020; Choi et al., Citation2005; Flage, Citation2018) against tenants and potential tenants.

Discrimination in the rental housing market can take various forms – direct and indirect. Direct discrimination, is a situation whereby an individual/group of people is/are treated less favourably than another is/would have been treated in a similar scenario. That is when a prospective tenant is discriminated against based on his/her background (gender, race, among others). On the other hand, indirect discrimination is likely to occur where a criterion or practice would unintentionally put some persons at a disadvantage compared to others unless that criterion or practice can be objectively justified (Flage, Citation2018). In this situation, the person was not intended to be discriminated against, but circumstances would cause an individual to be treated unfairly (for example, the disability of a person). Housing market discrimination can be related to housing supply, dwelling occupation, and the allocation of housing facilities. With regards to housing supply, certain categories of people are excluded from occupying the available housing facilities since the facility’s characteristics are unsuitable for them. This gives room for indirect discrimination and requires authorities to ensure that housing facilities are developed to meet the needs of every person, including persons with disabilities. The difficulties an occupant encounter as a result of harassment from a landlord and co-tenants gives room for discrimination in the dwelling unit to materialize. Lastly, discrimination may also occur during the allocation of a rental property. In this case, owners and agents of rental facilities discriminate against potential clients on several issues.

Housing discrimination during the process of allocating housing properties occurs when a home seeker receives unfavourable treatment from a property owner/agent as a result of his/her race, ethnicity, religion, disability, gender, and/or sexual orientation (Choi et al., Citation2005; Flage, Citation2018). Many international bodies and legislation in Europe and other parts of the world prohibit discrimination regarding access to housing (Gusciute et al., Citation2020). For instance, Article 17 (2) of the Constitution of the Republic of Ghana 1992, explicitly states that ‘a person shall not be discriminated against on grounds of gender, race, colour, ethnic origin, religion, creed, or social or economic status’. It further indicates in Article 17 (3) that ‘to discriminate means to give different treatment to different persons’. It can be deduced from these constitutional provisions that discrimination of whatever form, including in the rental market, contravenes the laws of Ghana. Similarly, Section 804 and 805 of the Fair Housing Act, Act 42 (Fair Housing Act 42, Citation1968) make it unlawful to discriminate in the sale or rental of housing and other properties in the United States.

Regardless of the anti-discrimination policies in place, discrimination is still prevalent within the rental housing industry and this poses a greater challenge to potential accommodation seekers. Securing accommodation becomes a major challenge amid discrimination, alongside the social and economic consequences it poses. Poor access to employment and education (Flage, Citation2018), a decline in welfare and overall wellbeing (Eurofound, Citation2004), worse health outcomes (Cattaneo et al., Citation2009), and a high cost of rental search (Acolin et al., Citation2016) are the major consequences of rental discrimination on the part of an individual. On the other hand, residential segregation (Flage, Citation2018) and lower levels of integration (Gusciute et al., Citation2020) are the consequences on the societal front.

Discrimination compromises equal opportunity for all and hurts individuals and by extension society, and socially, discrimination is unacceptable (Beatty & Sommervoll, Citation2012). While several studies have elucidated discrimination in varying forms in their jurisdictions, the concept, however, has not received adequate attention in the Ghanaian scientific space, despite the anecdotal evidence of the phenomenon. This study, therefore, sought to assess discrimination in the rental housing market in the Sunyani Municipality, Ghana. The main objective driving this study is to examine the drivers of discrimination in the rental housing market. This study is important because any form of discrimination in the rental housing market will compound Ghana’s high housing deficit, a product of the rapid urbanization taking place in Ghanaian cities. The housing deficit of Ghana is estimated at 1.5 million units (Kuffour, Citation2018), requiring a minimum of 170,000 units per annum to ameliorate the situation (Afrane et al., Citation2016). Further, Ghana is one of the rapidly urbanizing countries in sub-Saharan Africa (Moriconi-Ebrard et al., Citation2016) with 52 percent of its population currently living in urban areas (Afrane et al., Citation2016). Urbanization in Ghana is also driven by high levels of rural-urban migration. This migration induced urbanization means that Ghana’s urban spaces are multi-ethnic, cultural, and religious. Coupled with the high housing deficit, discrimination in the rental housing market can lead to significant challenges and stress for urban residents and drive rental prices up. This study, therefore, examines the tendencies, overtly and covertly, for discrimination in the rental housing market, using Sunyani Municipality, a rapidly urbanizing mid-sized city as a case.

The Sunyani Municipality was chosen for the study because it is a mid-sized, growth, and transition city with a population of ≤ 200,000. The city is experiencing increasing sprawl driven largely by the quest of individuals to own their own houses. Sunyani is also a net recipient of migrants, given its central location within the north-south, east-west geographic gradient of Ghana. As a growth and transition city, Sunyani is uniquely primed to avoid the housing challenges facing already established cities like Accra and Kumasi by exploring alternative pathways to dealing with the housing deficit, and meeting the housing demands of its diverse inhabitants in a non-discriminatory and satisfactory manner.

2. Literature review

2.1. Discrimination in the rental housing market

There is a plethora of literature on discriminatory practices in the rental housing market, each examining the issue from a different perspective, using different approaches (Acolin et al., Citation2016). While most of the literature bother on discrimination in the rental housing market of developed countries, there are significant lessons for developing countries. The literature on rental housing discrimination dates back several decades. These studies (Feins & Bratt, Citation1983; Wienk, Citation1979; Yinger, Citation1986, Citation1991) have often focused on forms of housing discrimination, groups, and individuals subject to discrimination and the factors upon which people are discriminated against. Predominantly, the issue of discrimination in the rental housing market has two main features – prejudices, either of the agent or customer and the lack of important information relevant to decision making (Baldini & Federici, Citation2011).

In developed countries, discrimination in the rental housing market is largely taste-based or statistical. In all these, there is an avoidance that occurs when customers are discriminated against based on their ethnic origin, race/colour, religious orientation, nationality, or gender (Auspurg et al., Citation2017; Baldini & Federici, Citation2011; Flage, Citation2018; Gbadegesin & Ojo, Citation2013; Oh & Yinger, Citation2015). Studies on prejudice-induced rental market discrimination have been carried out by HALDE (Citation2006) for some areas in France, Yinger (Citation1986) for Boston and more recently on a larger scale in Europe and US by Oh and Yinger (Citation2015), Ondrich et al. (Citation2003), Turner (Citation2015), and Turner et al. (Citation2002). Specifically, Baldini and Federici (Citation2011) in their study in Italy observed that there is evidence in favour of discrimination against foreigners in the rental market. To them, names largely connote the nationality of people and it also forms the basis of discrimination. In their study, people with Arab names were found to have been discriminated against as compared to those from Eastern Europe.

In developing countries in Africa and other parts of the world, discrimination does not necessarily follow similar trends as in developed countries. In the West African sub-region for instance, Gbadegesin and Ojo (Citation2013) examined the relationships between the tendencies of ethnic bias of property managers in Ibadan, Nigeria. Their study established that there is a strong relationship between the ethnic status of principal managers of rental properties and the tenants selected to occupy available vacancies. They, therefore, concluded that the prejudices of principal property managers resulted in ethnic discrimination in the selection of tenants in the Ibadan area. In the same vein, statistical discrimination can occur when there is prejudice against some nationalities. A study by Datta (Citation1996) in Gaborone, Botswana also identified that discrimination based on social status in landlords’ choice of tenants was prevalent.

Discrimination based on gender has also been observed in the literature (Ahmed & Hammarstedt, Citation2008), however, due to its invariable association with ethnicity, they have mostly been modelled together. Flage (Citation2018) observed apparent gender-based discrimination in the rental market. He observed that females have higher odds than males in receiving a response from landlords, thus, females are less likely to be discriminated against in their search for rental housing facilities. Heylen and Van den Broeck (Citation2016), in their study in Belgium also observed discrimination based on disability. Several housing facilities are disabling in themselves. These facilities are not friendly to persons with disabilities (PWDs), thus, socially, these categories of persons are discriminated from the rental housing market (Hemingway, Citation2011; Verhaeghe et al., Citation2016). Other factors such as household size, and religion (Murchie & Pang, Citation2018) can also be used to discriminate against prospective tenants.

Ghana is not immune from the global and regional developments on rental housing discrimination, although the Ghanaian case may be a bit peculiar to its local circumstances. Rental housing is an important component of the housing mix in Ghana (Owusu-Ansah et al., Citation2018). Estimated to constitute 31.1 percent of the total housing stock of Ghana, only 2 percent of rental housing is under state ownership (Ministry of Water Resources, Works and Housing, Citation2015, p. 7). The implication is that the private sector has a foothold in the rental housing market in the country. Meanwhile renting is said to be more pronounced in urban areas as opposed to rural Ghana (Owusu-Ansah et al., Citation2018). Currently, 47.2 percent of all houses in Ghana are rental properties (Ehwi et al., Citation2021) and overall, 46 percent of Ghanaians live in rented houses, although this varies across cities. While Accra has 67 percent of its residents living in rented houses (Gough & Yankson, Citation2011), 57 percent of the residents in Kumasi live in rented houses (Obeng-Odoom, Citation2011) with that of Sunyani, the focus of this study is not calculated although the then Brong-Ahafo region of which Sunyani was the capital had a housing deficit of 245,779 (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014).

Ghana is noted for its high housing deficit and inadequate rental units (Arku et al., Citation2012). As such the main objective of the National Housing Policy is ‘to create an environment conducive for investment in rental housing’ (Ministry of Water Resources, Works and Housing, Citation2015, p. 17), although private property owners have since the 1980s been accused of extortionist behaviour (Ninsin, Citation1989). The government’s response to the 1980 challenge was the passage of the Rent Control Law, PNDC Law 5, which effectively reduced rent charged on buildings by 50 percent and imposed a 50 percent tax on rent exceeding 1000 cedis although, efforts to control rent in Ghana dates back to the colonial era (Ehwi et al., Citation2021). Any landlord who breached the law could lose his property to the state. When landlords tried to circumvent the law, the government introduced the Compulsory Letting of Unoccupied Rooms and Houses Law 1982, PNDC Law 7, criminalising the refusal of a landlord to rent out unoccupied houses or rooms (Ninsin, Citation1989). Some four decades since these laws were made, the rental housing situation has not improved.

Ghana currently has an estimated housing deficit of over 1.5 million, exacerbating the rental housing situation which is also driven by rural-urban migration (Kuffour, Citation2018). The combined effect of inadequate housing supply and the rapidly rising urban population is the high cost of rent (Gavu, Citation2020; Kuffour, Citation2018). The rental housing market is so exploitative that many individuals are strenuously seeking to build their own houses (Gavu, Citation2020). The inability of the state to invest in rental housing units, the rising urban population with cosmopolitan characteristics and the exploitative tendencies of landlords, have the effect of leading to discriminative tendencies in the rental housing market.

2.2. Perspectives/theories of discrimination

Three main theoretical underpinnings: ‘taste-based’ discrimination, ‘statistical’ discrimination and social identity theory have been proposed in an attempt to explain reasons for discrimination. Firstly, taste-based discrimination refers to the unequal treatment of individuals/groups which occurs as a result of fear, prejudice and hostile attitudes towards minority groups/individuals (Becker, Citation1957). To Gusciute et al. (Citation2020), taste-based discrimination is inherent in individuals who express xenophobic attitudes towards other individuals/minority groups. To Flage (Citation2018), this form of discrimination arises as a result of the fear of difference and it manifests itself when agents/landlords become hostile towards other minority groups. Becker (Citation1957) in proposing this theory also argued that the tendency of complying with the negative attitude of the group an individual belongs to/attached to against others is a manifestation of taste-based discrimination. Juxtaposing this to the rental housing market, landlords are likely to discriminate due to their personal preferences or in order not to displease their existing tenants, they tend not to accept other tenants from some minority groups. Taste-based discrimination is difficult to thwart or neutralize since it is inherent/innate in individuals based on past events or historical antecedents and several efforts are required to change such mentality or status quo.

Statistical discrimination is another theory that has been postulated to explain the concept of discrimination. To proponents of this theory (Aigner & Cain, Citation1977; Phelps, Citation1972), this discrimination is less intuitive/innate, as it is a derivative of the absence of information regarding various minority groupings. Statistical discrimination is therefore largely based on prejudice. The information received by the bigot, be it real or perceived attributes about individuals or groups, is used as the basis for discrimination. For instance, using ethnicity as a proxy, the unknown characteristics of a particular ethnic group due to lack of in-depth information can be used to discriminate. Therefore, foreign or minority ethnic groupings are likely to be discriminated against in favour of one’s own or a major ethnic group (Flage, Citation2018). In relating this to the rental housing industry, landlords may perceive some ethnic groups as not ‘hardworking’ or ‘violent’ based on some information available to them, and as such might think that they do not have the financial ability to continuously pay their rents or be peace-loving tenants, thus the likelihood to discriminate against them will exist. To curb statistical discrimination, correct and detailed information about minority individuals/groups needs to be provided for informed decision-making.

The Social Identity Theory (SIT) can be used to rationalize discrimination in the rental housing market. SIT explains why people identify with a group and the likely consequences of that attachment. SIT holds that social and psychological processes influence intergroup relations in terms of the group’s development and maintenance (Tajfel, Citation1978; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). The proponents of SIT aver that people derive esteem from the social groups they identify themselves with, and therefore they tend to favour it and allocate resources to it to maximize the difference between their identifiable group and the non-identifiable group. This claim forms the basis for ethnocentrism which can breed discrimination. From the theory, people are more likely to discriminate against others due to the empathy and positive feeling they may have developed toward their affiliation, thereby evaluating their members more favourably than non-members (Hewstone et al., Citation2002). Juxtaposing this to the rental housing industry, landlords who identify with their social groupings (ethnicity, race, nationality etc.) are more likely to rent out properties to them than those belonging to the other social groupings (Gusciute et al., Citation2020).

3. Study area and methods

3.1. Study area

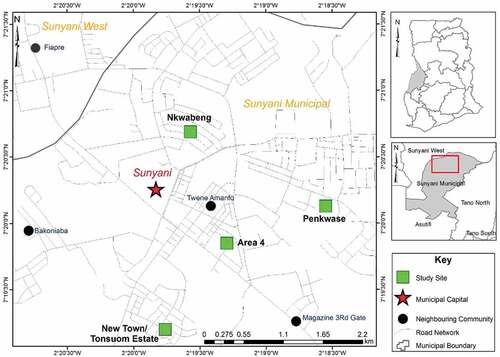

The study was carried out in the Sunyani Municipality (See, ). Sunyani is a mid-sized, growth, and transition city that serves the dual purpose of the administrative capital of the Sunyani Municipality and the newly created Bono Region of Ghana. It lies in the transitional agro-ecological belt of the country, covering a total land area of 829.3 km2. The population of the municipality was 123,224 in 2010 (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2010) and 193,595 in 2021 (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021). The capital, Sunyani, is a net recipient of migrants by virtue of its location, availability of central services such as universities, health training institutions, a referral hospital, various governmental departments and agencies, a military barracks and proximity to a major mine (Newmont Goldcorp Ghana Limited, Ahafo Operations). These diverse activities result in the influx of migrants from various parts of the country and beyond into the city in search of jobs, education, and health services.

These also have implications for the organization and performance of the rental housing market. The choice of Sunyani for this study, a multi-ethnic, cultural, religious city, populated by people of different social and economic statuses, is therefore relevant for understanding how discrimination plays out in the rental housing market. The choice of a mid-sized city also allows urban planners and managers to effectively explore ways of avoiding some of the ethno-racial and class problems being faced by established cities in Ghana and elsewhere. It also contributes to the emerging need for urban research to shift attention from established cities to emerging ones, which have been under-researched over the years.

3.2. Materials and methods

A quantitative research design was employed for this study. The target population for the study were tenants and landlords from selected households. Purposively, four communities; Nkwabeng, Penkwase, New Town/Tonsuom Estate and Sunyani Area 4 () were the selected study neighbourhoods. These four communities are located in the hub of Sunyani, which makes it prime areas where accommodation is mostly being sought by all classes of people, either low, middle or high-income earners. A criterion was used in selecting tenants to participate in this study; for tenants, household heads were selected to participate in the study, alongside the landlord or owner of the rental property.

Figure 2. Map of the study area.

A reconnaissance survey was conducted at the Regional Rent Control Department in Sunyani, a governmental body responsible for the management of landlord/tenant issues in Ghana. This survey revealed that as of 21 July 2020, only 107 housing properties have been registered within the selected study areas as rental facilities. A census was conducted for all the registered facilities located within the four selected communities. For every registered rental house, the nearest non-registered rental house was purposively selected, and the questionnaire was administered to the tenants and landlords. Upon selection of a rental house for the study, the questionnaire was administered only to tenants and landlords who were available and willing to partake in the research. In situations where tenants are more than one in a rented property, numbers were assigned to them and a simple random sampling was used to select one of the tenants to participate in the study. Under no circumstance was the questionnaire administered to more than one tenant in a particular house. Informed consent was sought from the selected tenant or landlord before the commencement of the administration of the questionnaire. The researchers administered the questionnaires mostly in English and in some cases it was administered in the dominant local language (Akan) for those who are not lettered in English. Out of the 445 questionnaires administered to landlords and tenants, 415 ‘cleaned’ questionnaires comprising 173 landlords and 242 tenants were deemed useful for further analysis.

The questionnaire used for the data collection was designed using a panel of experts from the Regional Rent Control Department and relying on literature. Questions regarding discrimination were extracted from sources such as Acolin et al. (Citation2016), Beatty and Sommervoll (Citation2012), Choi et al. (Citation2005), Flage (Citation2018), and Gusciute et al. (Citation2020). The identified variables that were deduced as converted into questions were household size, gender, age, nationality, marital status, disability and ethnic group. Landlords were asked, ‘do you mind the nationality of a potential tenant (Yes/No), do you mind the ethnic background of your potential tenant (Yes/No) among others. The questionnaire for both tenants and landlords had two sections. Section 1 contained filter questions on household characteristics and Section 2 focused on the discriminatory factors from the tenant’s perspective and factors considered when renting out facilities from the landlord’s perspective. Pre-testing of the instrument was done in Fiapre, an adjoining, peri-urban, and largely ‘dormitory’ community that has similar characteristics to the communities randomly selected for the study in the Sunyani Municipality. The choice of Fiapre for pre-testing was informed by the initial survey that sought to uncover the housing market situation for Sunyani Municipality and Sunyani West Municipality, two adjoining municipalities from the Rent Control Department. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census from the Ghana Statistical Service shows that in these two adjoining municipalities, more than half of their housing stock is made of compound houses (rooms). The selection of Fiapre for pre-testing was informed by the fact that it had similar housing conditions as the four selected communities after the reconnaissance survey was done.

3.3. Description of variables in the questionnaire

From the literature and panel of experts’ discussion, the following variables were identified as discriminatory factors in the rental housing market. The prejudice-based variables include ethnic origin, nationality, age, marital status, disability, and gender, while those based on information relevant to decision-making that is, household size were considered. To determine discrimination, respondents were asked whether they have ever felt discriminated against on any of these factors. Their responses were transformed using SPSS version 21 into a dichotomous variable, discriminated against, and not discriminated against.

3.4. Data analysis

The study investigates the determinants of discrimination in the rental housing market against tenants. Therefore, the dependent variable in this estimation was binary. Thus, if tenants have ever been discriminated against by their landlords or landlords have ever discriminated against tenants. As such, 1 is the response to being discriminated against, whiles 0 represents otherwise. In these binary situations, Gujarati (Citation2004) revealed that either the logit or probit model is preferred. In this study, the authors opted for the probit model with the likelihood of being discriminated against () considered as a non-linear function of k explanatory variables:

With a mean of 0 and a variance of 1, the represents the cumulative distribution function of a random variable. Where

are independent variables such as demographic characteristics (StataCorp, Citation2015). This yields a linear probit regression function.

If is positive, the predictor variable is likely to increase discrimination and vice versa. In estimating the probit model, variables such as age, level of education, residential status, gender etc., were used as predictor variables. See, for a detailed explanation of variables considered for the analysis.

Table 1. Explanation of variables used in the analysis

encapsulates the description of the variables used in the probit analysis. A total of 7 explanatory variables were considered for the analysis. Model 1 investigates determinants of discrimination against tenants by landlords. Thus, this model investigates tenants’ characteristics that make them susceptible to discrimination by their landlords. Tenants were asked whether they have ever been discriminated against by their landlords or otherwise. The response was binary (Yes or No).

Further information from revealed that independent variables such as household size, gender (male or female), age of tenant, nationality (Ghanaian or otherwise), marital status (married or otherwise), disability, and ethnic group (Akan or otherwise) were considered for the analysis in Model 1. Based on literature (Ahmed & Hammarstedt, Citation2008; Auspurg et al., Citation2017; Baldini & Federici, Citation2011; Flage, Citation2018; Gbadegesin & Ojo, Citation2013) it was estimated that all the variables under consideration (household size, gender, age of tenant, nationality, disability, and ethnic origin) were hypothesized to be positively related to discrimination in Model 1. Thus, all these variables are expected to increase the level of discrimination against tenants. However, marital status (married) is hypothesized to be negatively related to discrimination in this model. Hence, when a tenant has married the probability of him/her being discriminated against reduces.

Moreover, Model 2 investigates factors landlords consider before subletting their property to tenants for rental purposes. In this model, landlords’ tendency to discriminate was investigated based on the factors they consider in ‘discrimination’ against their soon-to-be tenants. The dependent variable is considered binary, whether the landlord has ever discriminated against a tenant or otherwise (Yes or No). The dependent variable for analysing the determinants of discrimination against tenants or landlords against tenants was a dummy. While the authors agree that categorisation of all kinds may cause a loss of information (see, DeCoster et al., Citation2011; MacCallum et al., Citation2002; Steegen et al., Citation2016), our objective is to know if landlords discriminate or not hence a continuous variable or categorisation of other levels would not be necessary as it will not help in the achievement of our objective. Besides, whether low, medium or high, it’s still discrimination, but non-discrimination is different hence the need to dummy the variables. Thus, the dummy variable matches this study’s research questions and assumptions. Also, the dichotomisation of the dependent variables makes it easier to explain the results to a non-scientific audience (Farrington & Loeber, Citation2000). Therefore, following Apipoonyanon et al. (Citation2020) the dependent variables were categorised.

Independent variables such as household size, gender, disability status, age of tenants, ethnic group, and nationality were considered in the analysis and were hypothesized to influence discrimination against tenants by landlords positively. These variables were envisaged to increase the level of discrimination meted out to tenants by landlords. Furthermore, landlords have a preference for married tenants, thus, the marital status of soon-to-be tenants is hypothesized to be a mitigating factor (reducing discrimination) in the rental housing market.

4. Results

4.1. Profile of the respondents

While more than half (55.5%) of the landlords are males, the opposite (54.4%, females) is the case for the tenants. As regards the age distribution; approximately 32 percent of the landlords were aged above 60 years, whereas more than 78.1% of the tenants were below 40 years. Most (59.5%) of the landlords were married, whereas 42.6 percent and 45.9 percent of the tenants were single or married, respectively. The only indicator where near parity was achieved was in the area of educational attainment (27.2% of landlords and 28.6% of tenants had attained tertiary education). The majority of the landlords (69.9%) and tenants (76.9%) are gainfully employed. Information on the income of the respondents revealed that on average most (63.1%) of the landlords earn between GH¢ 1501–2000 (US$ 251.11–334.59), whereas 68.7 percent of the tenants also earn between GH¢ 1001–1500 (US$ 167.30–250.95) (US$ 1 = 5.9774 for December 2021; [Bank of Ghana, Citation2021]). Trading was the dominant activity for both landlords (39.7%) and tenants (48.1%).

From the data, it could be deduced that data was evenly collected from four rental-dominated neighbourhoods in the municipality (Nkwabeng, Penkwase, New Town/Estate, and Area 4). The household composition of tenants varied considerably. While 41.0 percent of landlords had tenants whose household size ranges from 5 to 10 people, 39.3 percent of landlords had tenants with households of less than five people. Most tenants (44.4%) lived in houses with less than five tenants. As regards the size of households, the landlords noted that their properties are mostly (71.7%) inhabited by tenants with household sizes of between 2 and 5 people. The tenants also shared similar views, with more than two-thirds (67.8%) of them having household sizes ranging between 2 to 5 people.

4.2. Discrimination factors

Individual tenants expressed divergent views on the issue of whether they have ever been discriminated against or not in the rental housing market. While 104 respondents (60.8%) reported that they felt discriminated against, 67 respondents (39.2%) reported otherwise. In all, 7 factors were identified as potential discriminatory factors in the rental housing market (). From the perspective of the landlords, factors such as marital status (m = 0.62), household size (m = 0.53), ethnic origin (m = 0.42), and gender (m = 0.41) played significant roles in their decision to rent out their properties to tenants. The tenants corroborate the landlord’s perspective, however, with minimal variations. Tenants reported a 0.51 mean value and 0.48 for marital status and household size, respectively as grounds for discrimination. The implication is that both prejudices and information relevant to decision making are important considerations for both tenants and landlords in their rental decision making in the Sunyani Municipality and perhaps Ghana.

Table 2. Discriminating factors considered by landlords and tenants

The probit results of determinants of discrimination against tenants are found in . The Prob>chi2 = 0.000 reveals that the model is robust and significantly explains the relationship between the dependent and independent variables in a model without predictor variables. The pseudo R square of approximately 24% from attempts to provide information on the explanatory power of the independent variables; however, this should be done with caution as it is not the same as the r squared in the Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression. The linktest results (refer to in the appendix) reveal that the model has been specified correctly. The results show that the prediction squared is not significant and has no explanatory power. Meaning the model is rightly specified. Also, the probit regression’s diagnostic tests revealed that the model is well fitted (kindly refer to the LR test). Again, to test the heteroskedasticity in the model, the heteroskedasticity model was run concurrently. The results in in the appendix revealed that the Walt test insigma, which is a measure of heteroskedasticity in the probit model, is not significant hence the choice for the probit model is well fitted. Thus, there is no heteroskedasticity in the model. All other indicators as revealed in and A2 suggests that the model is robust and the choice is necessary.

Table 3. Determinants of discrimination against tenants

According to the table, household size, ethnic group, and marital status (married) were statistically significant determinants of discrimination amongst tenants. From , tenant household size and discrimination are positively associated. The results reveal that an additional increase in the household size of a tenant increases the probability of being discriminated against by 1.5%. Ethnicity is negatively associated with discrimination amongst tenants. From the table, Akan tenants (an ethnic group in Ghana) are 11% less likely to be discriminated against by landlords. Finally, the marital status of tenants was expectedly identified to be negatively related to discrimination. The result suggests that discrimination decreases, 17 percent less likely, amongst tenants who are married relative to single tenants.

presents the probit result of factors landlords consider in subletting their facilities to tenants. These results are emanating from the analysis of answers given by landlords. Like , The Prob>chi2 = 0.000 reveals that it is significant with a pseudo R square of approximately 81%. From the linktest results (refer to in appendix), the prediction squared is not significant (p-value of 0.738) and has no explanatory power indicating that the model is rightly specified. Also, the probit regression’s diagnostic tests revealed LR test is statistically significant (p < 0.001) suggesting the model is well fitted. Also, the results in in the appendix reveal that the Walt test insigma, which is a measure of heteroskedasticity in the probit model, is not significant (p > 0.1) hence the choice for the probit. Thus, there is no heteroskedasticity in the model. All other indicators as revealed in and A4 suggest that the model is robust and the choice is relevant for this study.

Table 4. Factors influencing the discrimination against tenants by landlords

From the table, household size, gender, nationality, marital status, ethnicity, disability and age of tenants were identified as significant determinants of discrimination against tenants by landlords. Specifically, household size is positively associated with discrimination against tenants, and it is significant at a 5 percent level. Thus, an increase in the number of household members of a tenant by one person is more likely to increase discrimination by landlords by 0.9 percent. Further, the results show that gender is negatively related to tenant discrimination. Thus, males are about 6.3 times less likely to be discriminated against as compared to females by landlords. Similarly, a Ghanaian national is less likely to be discriminated against by a landlord by approximately 13.3 percent compared to a foreigner. Likewise, as revealed in the tenant results in , landlords are less likely to discriminate against a married tenant than an unmarried one. Equally, a to-be tenant who is an Akan is less likely to be discriminated against than a non-Akan by approximately 24 percent. Surprisingly, the disability status of tenants and discrimination were positively associated. Thus, landlords are more likely to discriminate against tenants who are disabled, ostensibly because their facilities might not be disability-friendly. The results also reveal that the age of tenants and discrimination are positively related. This means, that as tenantsage, they are more prone to be discriminated against by landlords.

5. Discussion

The findings in this study provide evidence that there is discrimination within the Ghanaian rental housing market, in the Sunyani Municipality. Once discrimination has been confirmed by the tenants and landlords, it presupposes that both prejudices and variables relevant to decision making are inherent in the rental decision-making process. Gbadegesin and Ojo (Citation2013) made a similar finding. In their study which was carried out in Ibadan, Nigeria, they reported that discrimination is common within the rental housing market.

From the tenants’ perspective, the intensity of the discrimination is significant in terms of their household size, ethnic group, and marital status. On the other hand, landlords also consider household size, gender, age, nationality, marital status, ethnicity and disability. These indicate that there is evidence of discrimination in the rental housing market within the Sunyani Municipality of Ghana. The variables that are used in discrimination against tenants are consistent with the findings of Ahmed and Hammarstedt (Citation2008), Baldini and Federici (Citation2011), and Flage (Citation2018) among others. Baldini and Federici (Citation2011) found out that social (size of household) is a basis for which tenants are discriminated against. In expatiating this dynamic, landlords usually tend to think that tenants with larger household sizes are likely to put pressure on their facility’s amenities, thereby causing the property to deteriorate faster than a tenant who has a smaller household size. In these two scenarios, a property used by a tenant with a large household size is likely to deteriorate faster as compared to the same being used by a tenant with a small household size, ceteris paribus. Married tenants are most often preferred over ‘single’ tenants. This is because property owners are of the view that married tenants are more likely to keep their properties clean and maintain the premises, than unmarried tenants. This makes married tenants mostly to be considered by property owners when subletting their facilities.

Ethnicity has also been identified as a major factor upon which tenants are discriminated against. The findings of this study confirm those of Baldini and Federici (Citation2011), Flage (Citation2018), Gbadegesin and Ojo (Citation2013), and Gbadegesin and Ojo (Citation2013) found ethnic discrimination to be prevalent within the Ibadan housing market. Owusu and Agyei-Mensah (Citation2011), in their study in the two largest cities in Ghana (Accra and Kumasi), confirmed that there is evidence of ethnic discrimination in the rental housing market. From the study, the dominant Akan ethnic group is less likely to be discriminated against in the rental housing market. This is because Sunyani is predominantly an Akan settlement, and they are less likely to discriminate against themselves. In discriminating based on ethnicity, it could be largely a result of prejudice, where property owners might lack adequate information on the particular ethnic grouping they seem to discriminate against. In this context, discrimination based on ethnicity can be grounded in the Social Identity Theory (SIT). In this theory, it is postulated that people identify themselves with their social groups (ethnic groups) and will do everything to favour them. This might be why Akans are less likely to be discriminated against in a dominant Akan community, that is, Sunyani. Also, taste-based discrimination could be used to explain discrimination based on ethnicity. In Ghana, some people harbour fear and prejudice and have developed hostile attitudes towards other ethnic groups based on age-old disputes or perceptions between some ethnic groups. These perceptions/disputes have eaten into the ‘fabric’ of society and often form the basis upon which people perceived to belong to such ethnic groups are sometimes discriminated against.

The nationality of prospective tenants can also be used to discriminate against prospective tenants (Baldini & Federici, Citation2011). Names and accents (language) can be used to identify the nationalities of people. To some landlords, once they detect the nationality of the prospective tenant, they sometimes deny them access to their properties. In the study findings, Ghanaians are less likely to be discriminated against by landlords. Some property owners harbour animosity against other nationals as a result of the perceived nefarious activities they engage in. In this case, some property owners usually deny such people opportunities to rent their properties. The perspectives of discrimination discussed here could account for the discrimination, whether taste-based or statistical discrimination or SIT.

Furthermore, our study showed that gender (sex) is a basis upon which prospective tenants are considered when landlords tend to sublet their rental housing facilities. This outcome confirms the evidence from other studies (e.g. Ahmed & Hammarstedt, Citation2008; Baldini & Federici, Citation2011; Bengtsson et al., Citation2012). In a study by Ahmed and Hammarstedt (Citation2008) in Stockholm, the authors reported that landlords usually discriminate based on gender when renting out their facilities. In this context, landlords tend to have a preference for males as compared to females. According to Baldini and Federici (Citation2011), gender discrimination is higher among males than females within the Italian rental market which contradicts the findings of this study. Anecdotal evidence suggests that landlords in Ghana, tend to consider renting their facilities to females as against males because they tend to have the notion that females would keep the premises in a better condition since they undertake more janitorial services than males. This has usually informed landlords in their decision-making and has resulted in some males being discriminated against. However, the probit regression analysis performed in this study could not confirm such anecdotal evidence. It is therefore imperative to conduct further investigation into this finding to unearth the reasoning behind this finding.

Disability is also a ground on which landlords deny prospective tenants. In some situations, facilities are not disability friendly and thus, cannot be inhabited by persons with disabilities (PWDs; Heylen & Van den Broeck, Citation2016). In this scenario, a school of thought considers this as not a form of discrimination but rather social exclusion as a result of the lack of the required infrastructure for such people (Hemingway, Citation2011; Verhaeghe et al., Citation2016). In Ghana, buildings are usually constructed without provision for PWDs and this automatically takes such people out of the rental market. In lower-income rental markets, some facilities do not have places of convenience within the premises and tenants have to walk over a distance to access such facilities. This scenario is not ideal for PWDs, thus, they are socially ‘discriminated’ from accessing the private rental housing market. Public rental housing facilities in Ghana such as the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) and other government-owned housing facilities are also not disability friendly. Tenants with mobility and vision impairment find it difficult to access such facilities that are ‘unfriendly’ to them. These and other reasons make it difficult for PWDs to access decent housing facilities in Sunyani and Ghana.

6. Conclusion and implications for policy and theory

The purpose of this study was two-fold: to examine if there is discrimination in the rental housing market in Ghana and determine the drivers/factors, if any. In this study, evidence of the occurrence of discrimination based on factors such as household size, ethnicity, gender, nationality, marriage and disability exists in the rental housing market in Sunyani. First and foremost, the tenants feel discriminated against during the stage of renting a private accommodation facility. To them, they are often denied housing facilities based on the size of their household, ethnicity and marriage. Due to prejudice (statistical discrimination), landlords sometimes have limited knowledge concerning some ethnic groupings and yet discriminate against them. Also, as a result of the social groups they belong to, they tend to favour those social groupings as against the minority or other social groupings (ethnic groups). This makes it difficult for the minority ethnic group to access rental accommodation facilities. From the study findings also, it is estimated that a unit increase in the household size of prospective tenants has the propensity for them to be discriminated against in the rental housing market. As tenants feel discriminated against during the process of accessing rental facilities, so do landlords also have some indicators they look out for when subletting their facility. Alongside the factors that are discussed above regarding tenants, landlords also consider disability, gender, and nationality.

The findings from this study highlight some important issues for policy. Ghana is one of the countries that, as indicated earlier on in this study faces a precarious housing supply challenge. The implication is that housing demand outstrips the housing supply. This further throws up several issues alongside the affordability of the available housing units. Even though demand outweighs supply in the Ghanaian rental housing market, tenants are sometimes discriminated against when accessing the relatively small housing facilities available. Also, the high demand for housing facilities allows property owners to be sometimes selective on who to hire their facilities to. Under such circumstances, some prospective tenants are directly or indirectly discriminated against. The policy options available to the government to curb this situation of discrimination, therefore, would be to explore avenues to expand public housing delivery.

In an article published by Graphic Online on 11 April 2018, there was a call to prioritize the needs of PWDs in accessing housing facilities, since it has been noticed that housing policies have failed to address the needs of PWDs (Keddey, Citation2018). Also, the Persons with Disability Act 715 (Citation2006) has to have its tenets implemented to the letter. This will serve as a way of ameliorating the difficulties associated with access to housing for PWDs. Also, the government must continue to make provisions for its affordable housing projects to address the housing deficit in the country. This will help address the overt or covert practice of discrimination in the rental housing market. Meanwhile, the list of offences contained in the Rent Act, Citation1963(Act, 220) does not make discrimination an offence for which a fine or penal sanction could be imposed. Given the nature of the political economy of rental housing in Ghana, where the state owns only 2 percent of the rental housing stock, criminalizing discrimination is not an effective measure to curb the menace. Rather, the Rent Control Department and the National Commission for Civic Education should carry out sensitization exercises to educate the large private owners of housing on the consequences of discrimination in the renting of their properties. The government on the other hand is expected to invest more in its affordable housing projects for the citizens to have access to low-cost housing. Also, the financial sector should consider repackaging their mortgage facilities and making them more affordable for people so that they could also acquire their housing properties.

Theoretically, this study affirms the findings of various studies conducted in both developed and developing countries on the subject matter. This study supports the conclusions reached by previous researchers that discrimination is either taste-based or statistical. If property owners have in-depth information concerning minority groups, their ‘taste’ or prejudice may change.

7. Limitations and areas for further studies

A limitation of the study is not adding housing variables such as the type of house, the number of bedrooms, the rent charged, the amenities provided and the advance rent demanded in the modelling of the extent of discrimination. Therefore, it is suggested that future studies should endeavour to include these variables to validate these results. Another limitation is the method employed in soliciting information on discrimination from the perspective of property owners. Yinger (Citation1998) noted that there is a tendency for bias when asking people how they make decisions as they may be unwilling to admit they hold prejudices or withhold information from prospective tenants that may be socially condemned which might form a basis for discrimination. Subsequent studies should devise appropriate methodologies to avoid such a scenario. With the findings on gender being unusual, it’s expected that a qualitative study is conducted to elicit further information and explanation on the role of gender as a discrimination factor in the rental housing market. Again, future studies should consider comparing the most urbanised cities to less urbanised towns to extend the scope of this study. Again future studies can explore the role of law and institutions in regulating the housing market in Ghana.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the research assistants that helped in the data collection exercise. We are grateful to them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Acolin, A., Bostic, R., & Painter, G. (2016). A field study of rental market discrimination across origins in France. Journal of Urban Economics, 95, 49–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jue-2016-07-003

- Adu-Gyamfi, A., Cobbinah, P. B., Gaisie, E., & Kpodo, D. D. (2020). Assessing private rental housing in the absence of housing information in Ghana. Urban Forum, 32(1), 67–85 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-020-09407-3

- Afrane, E., Ariffian, A., Bujang, B., Shuaibu, H., & Kasim, I. (2016). Major factors causing housing deficit in Ghana. Developing Country Studies, 6(2), 139–147. http://repository.futminna.edu.ng:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/9905

- Ahmed, A. M., & Hammarstedt, M. (2008). Discrimination in the rental housing market: A field experiment on the internet. Journal of Urban Economics, 64(2), 362–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2008.02.004

- Aigner, D. J., & Cain, G. G. (1977). Statistical theories of discrimination in labour markets. ILR Rev, 30(2), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979397703000204

- Apipoonyanon, C., Kuwornu, J. K., Szabo, S., & Shrestha, R. P. (2020). Factors influencing household participation in community forest management: Evidence from Udon Thani Province, Thailand. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 39(2), 184–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2019.1632211

- Arku, G., Luginaah, I., & Mkandawire, P. (2012). You either pay more advance rent or you move out: Landlords/ladies’ and tenants’ dilemmas in the low-income housing market in Accra, Ghana. Urban Studies, 49(14), 3177–3193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012437748

- Aruma, E. O., & Hanachor, M. E. (2017). Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and assessment of needs in community development. International Journal of Development and Economic Sustainability, 5(7), 15–27.

- Auspurg, K., Hinz, T., & Schmid, L. (2017). Contexts and conditions of ethnic discrimination: Evidence from a field experiment in a German housing market. Journal of Housing Economics, 35, 26–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2017.01.003

- Baldini, M., & Federici, M. (2011). Ethnic discrimination in the Italian rental housing market. Journal of Housing Economics, 20(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2011.02.003

- Bank of Ghana. (2021). Bank of Ghana news brief: Exchange rates. Retrieved December 24 on Friday, 2021, from https://www.bog.gov.gh/treasury-and-the-markets/daily-interbank-fx-rates/

- Beatty, T. K. M., & Sommervoll, D. E. (2012). Discrimination in rental markets: Evidence from Norway. Journal of Housing Economics, 21(2), 121–130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2012.03.001

- Becker, G. (1957). The economics of discrimination. University of Chicago Press.

- Bengtsson, R., Iverman, E., & Hinnerich, B. T. (2012). Gender and ethnic discrimination in the rental housing market. Applied Economics Letter, 19(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2011.564125

- Cattaneo, M. D., Galiani, D., Gertler, P. J., Martinez, S., & Titiunik, R. (2009). Housing, health and happiness. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 1(1), 75–105. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.1.1.75

- Choi, S. J., Ondrich, J., & Yinger, J. (2005). Do rental agents discriminate against minority customers? Evidence from the 2000 housing discrimination study. Journal of Housing Economics, 14(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2005.02.001

- Datta, K. (1996). The organization and performance of a low-income rental market: The case of Gaborone, Botswana. Cities, 13(4), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/0264-2751(96)

- DeCoster, J., Gallucci, M., & Iselin, A. M. R. (2011). Best practices for using median splits, artificial categorization, and their continuous alternatives. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 2(2), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.5127/jep.008310

- Ehwi, R. J., Asante, L. A., & Gavu, E. K. (2021). Towards a well-informed rental housing policy in Ghana: Differentiating between critics and non-critics of the rent advance system. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 15(2), 315–338. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHMA-12-2020-0146

- Ehwi, R. J., Asante, L. A., & Morrison, N. (2020). Exploring the financial implications of advance rent payment and induced furnishing of rental housing in Ghanaian Cities: The case of dansoman, Accra-Ghana. Housing Policy Debate, 30(6), 950–971. doi:10.1080/10511482.2020.1782451.

- Eurofound. (2004). Quality of life in Europe. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Fair Housing Act 42. (1968, April 11). Retrieved November 29, 2021 from https://brunswickpha.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/FAIR-HOUSING-ACT.pdf

- Farrington, D. P., & Loeber, R. (2000). Some benefits of dichotomization in psychiatric and criminological research. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 10(2), 100–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.349

- Feins, J. D., & Bratt, R. G. (1983). Barred in Boston: Racial discrimination in housing. Journal of the American Planning Association, 49(3), 344–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944368308976561

- Flage, A. (2018). Ethnic and gender discrimination in the rental housing market: Evidence from a meta-analysis of correspondence tests, 2006-2017. Journal of Housing Economics, 41, 251–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2018.07.003

- Gavu, E. K. (2020). Conceptualizing the rental housing market structure in Ghana. Housing Policy Debate, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2020.1832131

- Gbadegesin, J. T., & Ojo, O. (2013). Ethnic bias in tenant selection in metropolitan Ibadan private rental housing market. Property Management, 31(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1108/02637471311309445

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2010). Population and housing census report.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2014). Housing in Ghana. Retrieved April 17, 2022, from https://www2.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/2010phc/Mono/Housing%20in%20Ghana.pdf

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2021). Population and housing census report.

- Gough, K. V., & Yankson, P. (2011). A neglected aspect of the housing market: The caretakers of peri-urban Accra, Ghana. Urban Studies, 48(4), 793–810. doi:10.1177/0042098010367861.

- Gujarati, D. N. (2004). Basic econometrics (4th ed.). The Mc-Graw Hill.

- Gusciute, E., Műhlau, P., & Layte, R. (2020). Discrimination in the rental housing market: A field experiment in Ireland. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(3). 613–634 . https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1813017

- HALDE. (2006). Deliberation no. 2011-122. 2011. http://www.halde.fr/IMG/alexandrie/6211PDF

- Hemingway, L. (2011). Disabled people and housing: Choices, opportunities and barriers. Policy Press.

- Hewstone, M., Rubin, M., & Willis, H. (2002). Intergroup bias. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 575–604. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135109

- Heylen, K., & Van den Broeck, K. (2016). Discrimination and selection in the Belgian private rental market. Housing Studies, 31(2), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2015.1070798

- Keddey, K. (2018, April 11). Prioritise needs of persons with disability in housing. Graphic Online. https://www.graphic.com.gh/features/opinion/prioritise-needs-of-persons-with-disability-in-housing.html

- Kuffour, K. O. (2018). Let’s break the law: Transaction costs and advance rent deposits in Ghana’s housing market. Global Journal of Comparative Law, 7(2), 333–354. doi:10.1163/2211906X-00702005.

- MacCallum, R. C., Zhang, S., Preacher, K. J., & Rucker, D. D. (2002). On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.19

- Ministry of Water Resources, Works and Housing. (2015). National housing policy. Accra: Ministry of Water Resources, Works and Housing.

- Moriconi-Ebrard, F., Harre, D., & Heinrigs, P. (2016). Urbanisation dynamics in West Africa 1950-2010: Africapolis I, 2015 update. OECD Publishing.

- Murchie, J., & Pang, J. (2018). Rental housing discrimination across protected classes: Evidence from a randomized experiment. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 73, 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2018.10.003

- Ninsin, K. A. (1989). Notes on landlord-tenant relations in Ghana since 1982. Institute of African Studies Research Review, 5(1), 69–76.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. (2011). Private rental housing in Ghana: Reform or renounce? Journal of International Real Estate and Construction Studies, 1(1), 71–90.

- Oh, S. J., & Yinger, J. (2015). What have we learned from paired testing in housing markets? Cityscape, 17(3), 15–60. U.S. Department of Housig and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. Retrieved on December 17, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26326960

- Ondrich, J., Ross, S., & Yinger, J. (2003). Now you see it, now you don’t: Why do real estate agents withhold available houses from black customers? Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(4), 854–873. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465303772815772

- Owusu-Ansah, A., Ohemeng-Mensah, D., Abdulai, R. T., & Obeng-Odoom, F. (2018). Public choice theory and rental housing: An examination of rental housing contracts in Ghana. Housing Studies, 33(6), 938–959. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1408783

- Owusu, G., & Agyei-Mensah, S. (2011). A comparative study of ethnic residential segregation in Ghana’s two largest cities, Accra and Kumasi. Population and Environment, 32(4), 332–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-010-0131-z

- Persons with Disability Act 715. (2006, August 9). https://sapghana.com/data/documents/DISABILITY-ACT-715.pdf

- Phelps, E. S. (1972). The statistical theory of racism and sexism. The American Economic Review, 62(4), 659–661. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1806107

- Rent Act, Act 220. (1963, December 12). https://bcp.gov.gh/acc/registry/docs/RENT%20ACT,%201963%20(ACT%20220)%20.pdf

- StataCorp. (2015). Stata: Release 14. Statistical software.

- Steegen, S., Tuerlinckx, F., Gelman, A., & Vanpaemel, W. (2016). Increasing transparency through a multiverse analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(5), 702–712. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616658637

- Tajfel, H. (Ed.). (1978). Differentiation between social groups . In Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. London: Academic Press.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

- Turner, M. A. (2015). Other protected classes: Extending estimates of housing discrimination. Cityscape, 17(3), 123–136. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26326964

- Turner, M. A., Ross, S. L., Galster, G. C., & Yinger, J. (2002). Discrimination in metropolitan housing markets: National results from phase I HDS 2000. US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

- UN General Assembly. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. Retrieved December 16, 2021, from https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

- University of Cape Coast, Cartography Section. (2018). Map of Ghana. Department of Geography and Regional Planning. Cape Coast: University of Cape Coast.

- Verhaeghe, -P.-P., Van der Bracht, K., & Van de Putte, B. (2016). Discrimination of tenants with a visual impairment on the housing market: Empirical evidence from correspondence tests. Disability and Health Journal, 9, 234–238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.10.0022

- Wienk, R. E. (1979). Measuring racial discrimination in American housing markets: The housing market practices survey (Vol. 444). Division of Evaluation, US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research.

- Yinger, J. (1986). Measuring racial discrimination with fair housing audits: Caught in the act. The American Economic Review, 76(5), 881–893. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1816458

- Yinger, J. (1991). Acts of discrimination: Evidence from the 1989 housing discrimination study. Journal of Housing Economics, 1(4), 318–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1051-1377(05)80016-6

- Yinger, J. (1998). Housing discrimination is still worth worrying about. Housing Policy Debate, 9(4), 893–927. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.1998.9521322

Appendix

Table A1. Measures of fit of probit regression for tenants

Table A2. Linktest analysis of probit regression for tenants

Table A3. Measures of fit of probit regression for landlords

Table A4. Linktest analysis of probit regression for landlords