ABSTRACT

Public transport service in Addis Ababa is provided by both public and private operators. However, the inability of the public sector to meet the increasing transport demand has given rise to the emergence of privately owned paratransit transport services. The minibus taxi sector is the dominant public transport mode which provides a means of mobility for the majority of the city’s residents. However, the service provided by the sector is still far from being efficient and has a lot of operational constraints. But, various attempts have been made by the city’s transport authority to improve service provision in the city. Thus, to carry out this study, both primary and secondary data were used. Instruments like questionnaires, interviews, as well as observation were intensively employed. Finally, the Arada sub-city was selected purposively to execute the study as it is the hub for 9 taxi terminals with 25 routes radiating into several directions of the city. A total of 50 minibus taxi drivers were selected using the convenience sampling method. Results of the study revealed that the presence of complex owner-driver relations, customary operational practices, and poor institutional organization of owners’ associations as well as inefficient regulation creates unpleasant work situations and hence profoundly affected service delivery. In addition, the study found that all of these situations are threatening the sustainability of the sector as most vehicle owners have less interest in staying in the business.

1. Introduction

The provision of adequate and appropriate public transport services is one of the most important components of the well-being of growing urban areas (Murray et al., Citation1998; Thondoo et al., Citation2020). However, the delivery of quality urban public transport and services is one area identified as faced with huge deficits and shortages in Africa (Chakwizira et al., Citation2011; Dumedah & Eshun, Citation2020; Tembe et al., Citation2019).

Paratransit transport has given different names widely used interchangeably that take many contexts and even overlap each other. For instance, Cervero (Citation2000) has given different names varyingly referred to as ‘paratransit’, ‘low-cost transport’, ‘intermediate technologies’, and ‘third world transport’ to reflect the context in which the sector operates informally and illicitly, and outside the officially sanctioned public transport sector. Golub (Citation2003) also stated that informal transport can be used equally with paratransit. According to Golub (Citation2003), 70 percent of total public transit trips are in Manila, the Philippines, 50 percent in Jakarta, Indonesia, 40 percent in Kuala Lumpur, 55 percent in Mexico City, 30 percent in Hong Kong, 33 percent in Nairobi, Kenya, and 50 percent in San Juan, Puerto Rico are supplied largely by informal paratransit modes.

Despite their importance in providing flexible urban transport services, the sector is responsible for significant negative externalities such as congestion and air pollution. Minibusses, motorized pedicabs, and for−hire station wagons are gross emitters of air and noise pollution for several reasons: diesel propulsion; absence of catalytic converters; reliance on old, decrepit vehicles with under−tuned engines; frequent acceleration and deceleration in congested traffic (Cervero, Citation2000) The disadvantages inherited particularly by the informal urban transport are making them candidates for regulations and a wide range of policy interventions from public officials. Cervero (Citation2000) outlined a spectrum of public policy responses to informal public transportation ranging from acceptance to prohibition.

Addis Ababa, like other cities in the developing world, has continued to battle mobility issues as its public transportation services are insufficient to meet the changing needs of its diverse population and economic activities. The fast growth of mobility demand precipitated by rapid urbanization and the service void left by the sole conventional public transport provider/Anbessa city bus/often contribute to the mushrooming of privately run paratransit minibus taxi transport systems. The paratransit minibus taxi service has become the dominant mode of public transport in the city. As Ethiopian Roads Authority (2005) reveals Anbessa city buses provide 40% of the public transport of the city, while minibus taxis account for 60%. Another study by the World Bank (Citation2002) also found that minibus taxis contribute 73% of the total modal choice of a city. A recent study by the Addis Ababa City Administration Road and Transport Bureau (Citation2018) reveals that there is a high demand for public transportation in the city whereby the modal share of public transportation is 31%. Walking predominates with a modal share of 54%; and private automobiles and taxis with a 15% share.

However, the service provided by paratransit minibus taxis is poor in quality to satisfy the needs of the public and experienced several operational constraints. It has been a day-to-day experience for passengers queuing for several minutes at terminals waiting for a taxi, breaking up long routes into shorter ones, arbitrary tariff increments, and overloading by paratransit minibus taxi operators. According to TilahUN (Citation2014), the service is mostly demand-driven that picks up or drops off passengers on an ad hoc basis. The city’s transport office has been drafting several laws and rules intending to improve service provision.

In addition, paratransit transport has been given little attention by scholars and policymakers to uncover its nature and operating characteristics. So far several studies and researches have been conducted on Addis Ababa’s public transport problems; such as Mekuria Wondimu (Citation2012); Meron (Citation2007); TilahUN (Citation2014), Gebeyehu and Takano (Citation2004), Ajay and Barret (Citation2008), and World Bank (Citation2002)). However, all of them were principally focused on the public transport service provider of the city in general and Anbessa city bus operations in particular except (Mekuria Wondimu, Citation2012) who tried to evaluate the performance of the newly introduced zonal minibus taxi transport system. This indicates that little or no research work has been done concerning paratransit minibus taxi service provision, especially on its nature and characteristics of operation concerning actors in the sector. Thus, this study tries to cover the gap by examining the Paratransit transport in the city in detail. Moreover, a close look and detailed investigation of the nature, operational characteristics, and organization and regulation aspects of paratransit minibus taxis with particular emphasis on drivers helps to visualize the extent to which the sector has been operating and inherent problems emanate from it. Considering that this study aims to examine the nature and operating characteristics of paratransit minibus taxis with particular inference to drivers as well as their organization and regulation. Hence, this study contributes by showing the operation of paratransit transport services in the context of developing countries emphasizing the context of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

2. Urban transport in the city

Urban transport in Addis Ababa is carried by a mixture of public and private ownership structures. The dominant public transport modes of the city include public buses, minibusses, shared minibus taxis, and more recently light rail transit. The total number of passenger vehicles in Ethiopia is 46,897, of which more than 56.1% are found in Addis Ababa (Addis Ababa City Government, Office of Mayor, Citation2011). In addition, the city has a low record private car modal share which was only 7% while it was 35% in Kampala, Uganda, and 18% in Abidjan, Nigeria (Ajay & Barret, Citation2008), showing Addis Ababa’s reliance on public transport mode.

Walking and public transport are the dominant forms of mobility in Addis Ababa, making up an estimated 85% of trips. The mode share for personal motor vehicles (PMV) is small, accounting for 15% (World Bank, Citation2002). The dominant Public transport in the city consists of conventional bus services provided by the publicly owned Anbessa City Bus Enterprise; Sheger Mass Transport Enterprise and minibus taxis operated by the private sector. According to Addis Ababa Transport Authority (AATA; Citation2017), Anbessa City Bus Enterprise is providing service with a total of 723 buses along 123 routes and transports 396,000 passengers per day. The average number of trips per day is 10 while the average waiting time of passengers to take the bus is 86 minutes.

Besides, Minibus transportation service is provided by both Code 1 blue minibus and Code 3 supporting minibusses. Code 1 blue minibus taxis provide service with a total of 3,481 vehicles along 318 routes and transport 668,352 passengers. Code 3 supporting minibusses provide service with a total of 4,392 vehicles along 303 routes. Compared to the other public transportation service providers, minibus taxis serve a higher number of routes, and the waiting time to get the service is 12 minutes (Addis Ababa Transport Authority (AATA), Citation2017).

In Addis Ababa Minibus taxi vehicles are the dominant polluters. According to Kebede (Citation2019), Code-1(Minibus Taxi) was the dominant air pollutant with an average smoke opacity value of 86.36% and only 8.57% passed the standard limit. Most of the Vehicles in this category were those with the oldest model year of 1995 and older. On the contrary, code-3 (commercial vehicles) were recorded with an average smoke opacity value of 43.31% which was less than that of Minibus Taxi by half but greater than the standard cut points.

3. Research methodology

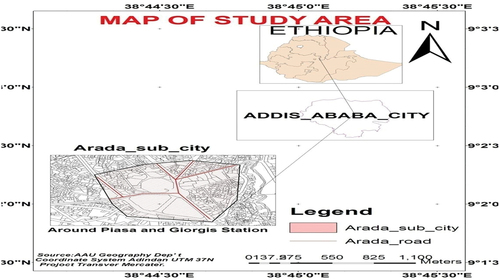

Study area

This study was conducted in one purposefully selected sub-city of Addis Ababa (i.e. the Arada sub-city, ). Addis Ababa is the hub of the Ethiopian urban economy. The GDP of the city accounts for a significant share of the National GDP. Eighty-five percent of the manufacturing industries ofin the country are located in Addis Ababa and its surrounding (Meshesha Tilahun, Citation2009). Industry accounts for 46% of the annual gross production of Addis Ababa while service and agriculture sectors cover 45% and 8.3%, respectively (Addis Ababa City Government, Office of Mayor, Citation2011). According to the interim report of the CSA (Citation2012), 28.1% and 26.1% of the residents of Addis Ababa were under general poverty and food poverty respectively.

Data and method

In exploring the nature, and operating characteristics of paratransit minibus taxis as well as their organization and regulation, the descriptive research design was adopted and relevant data were collected through primary sources, which consisted of a survey, personal observation, and key informant interviews.

It was found that neither it was possible to consider the entire number of minibus taxi drivers nor employ representative random sampling in Addis Ababa due to the difficulty of getting the list of minibus taxi drivers and identifying where they are operating as well as the high mobility nature of minibus taxi operators. Keeping this in view, the Arada sub-city was deliberately selected because its position in the city makes it among one of the city’s public transport spots containing several minibus taxi terminals. There are 9 different minibus taxi terminal sites in the area serving as loading and unloading of passengers from over 25 different routes of the city.

Once more, the study conveniently selected drivers among several stakeholders due to their role in the sector and business relations with vehicle owners. Besides, the study has involved minibus taxi drivers in all of the 9 taxi terminals operating on 25 routes. In total, 2 drivers from each route (altogether 50 participants) were conveniently selected and distributed the questionnaire. The questions include vehicle ownership, operational characteristics, and problems faced while working as a taxi driver in the city. Therefore, 50 questionnaires were collected from drivers in the sub-city for the study. The response rate for the study was 100%. Besides, an interview was conducted with four purposively selected key informants from Taxi Transport Owners Associations and the Transport Office of the sub-city.

4. Results and discussion

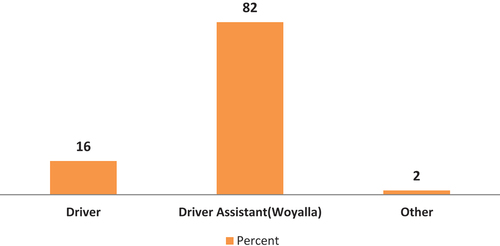

4.1. Started work type

All driver respondents were asked at which position they get started to work in the minibus taxi business. The results, summarized in , reveal that 82% of them have started the job as a driver assistant or ‘Woyala’ whereas the remaining 16% started working directly as a driver. In addition, the findings of the study reveal that they started working as an assistant to drivers mainly to make their daily living with less or no intention to become a taxi driver. However, while doing so they learned to drive and then went to driving school to get a license where they sought to be a taxi driver. Besides this working, in the same position, they get in touch with customary laws that dictate how the sector operates and establish relations with business networks inside the sector. For owner drivers instead, the situation was different. The majority of owner-drivers (14 out of 16) said that they decided to join the taxi business because of its perceived benefits observed while working for the owner as a driver.

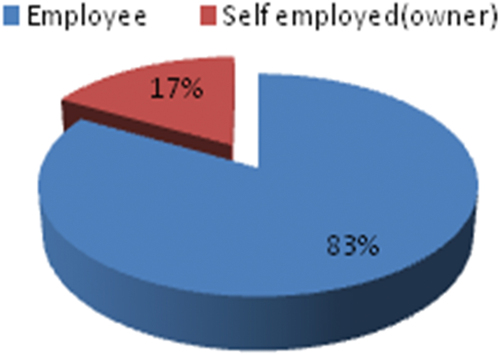

4.2. Ownership of vehicles

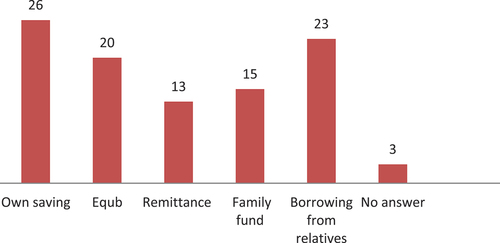

The study found that only 17% of the drivers owned the vehicles they were operating while 83% of them were employees as shown in .

Besides, as shown in , the source of capital to start the business for owner drivers include own savings, equb(informal social financial institution), remittance, family fund, and borrowing from relatives. Also, most of the respondents relied on more than one source as vehicle buying prices were so expensive to afford on their own.

In addition, the recruitment and hiring of drivers were done by vehicle owners considering their previous experience. Thus, the majority of drivers replied that social and business networks such as being from the same village, family, and friendship relations are important recruitment tools used in the sector. The drivers interviewed were also asked about the contractual agreements they had with employers. None of the driver respondents have written agreements. Instead, the common practice is through verbal agreements.

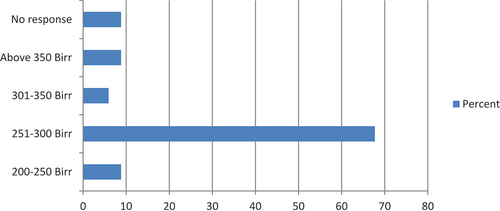

In addition regarding work relations between owner and driver, the results from the participants indicated that drivers (except owner-drivers) have to bring fixed daily revenue to the owner. Driver respondents reported that the amount of daily revenue that goes to vehicle owners ranges from the maximum of 350 Birr to the minimum of 200 Birr. The majority of drivers set a target of 250 Birr as daily revenue. Further probing revealed that the type of engine and vehicle’s technical fitness are usually taken into account to fix the amount of the owner’s daily earnings. For instance, a driver hired to work on a diesel engine vehicle earns more than those who run benzene engines. This is because the cost of diesel petrol per liter is cheaper than gasoline. The other factor that influences the daily amount collected by the owner is the technical performance of the vehicle which is also taken by drivers to negotiate the daily amount paid to the owner after test driving. For this reason, one respondent said that there are situations where drivers are forced to renegotiate with owners on daily payments as the vehicle starts to consume more fuel.

In addition, it is the responsibility of the driver to pay for daily fuel costs and fines for violations of traffic regulations. The vehicle owners on their part are responsible to cover costs related to vehicle maintenance, regular services, and annual work permit renewals as well as third-party insurance payments.

Concerning owners’ means of control of driver’s handling of a vehicle and daily revenues, drivers were asked how often their employers supervise daily operations; the responses to this question reveal that 96% of drivers have not been supervised daily by owners. Conversely, only 4% of the drivers reported that their employers supervised them as shown in . Owners closely monitor the driver’s handling of a vehicle and daily revenues by assigning a watchman ‘Emba’, their close relative working as an assistant(‘Woyala’) to the driver. However, the common practice is the driver is free to manage the vehicle consensually and based on trust.

Concerning the payment of drivers shows the detailed findings of the study. Drivers are paid monthly, and the majority of drivers (67.7%) receive a monthly salary of 251–300Birr. The amount of salary paid is governed by the concession agreement between the owners and drivers. This indicates that drivers’ monthly salary is too small to make a living unless and otherwise, they have another source of income.

In addition, drivers have a per diem mostly paid for daily meals and related costs of the taxi crew considered as part of the daily operational expense and some amount out of it is paid to their assistants for meals. The daily per diems range between 100 and 150 Birr. Interviews with the participants also indicated that drivers are not much worried about their nominal monthly salary; rather they make every effort to maximize the daily net or ‘Jornata’ out of the daily operations.

Lastly, drivers’ assistants or ‘Woyallas’ have a significant role in the minibus taxi industry. They are in charge of attracting passengers and collecting fares from passengers. Driver assistants also alert the driver when to drive and stop for passengers to alight. In addition, as field observation noted, they lead the race with other taxis to grab passengers along the route.

As mentioned earlier, business relations and operations in the taxi industry have their customary governing practices. The same customary rule applies to establishing a driver’s and assistants relationship. The responses from drivers’ interviews show that ‘Woyallas’are hired by drivers daily with a certain amount of payment. Daily earnings of ‘Woyallas’ are determined by the total amount of money collected by the taxi crew. However, daily payments are also varied with their work experience being as driver assistants. One driver respondent said that there is a tendency among more experienced driver assistants that they share the daily net equally with drivers. There are instances whereby driver assistants retain some amount of money collected from passengers without the knowledge of the driver. This is also confirmed by driver respondents that assistants take some amount from which they should give to the driver. Taking into account the work situation of drivers, there is no way for them to know exactly the amount collected. Businesses are highly reliant on trust. However, driver respondents report that some drivers attempted to control fares collected from passengers by taking the money right after each trip or ‘Biajo’.

4.3. Operational characteristics

Working days

The majority of drivers (74%) assumed that they plied all the weekdays, whereas 26% of the drivers said they worked for 6 days. Among drivers who work all days of the week, the majority of them are hired drivers and most self-employed drivers skip work Saturday afternoons and Sundays. The study further probes that hired drivers to have 1–2 days off once a month when the vehicle became not operational for scheduled vehicle servicing ().

Driver’s working hours

As can be observed from , 50% of hired drivers start work in the morning between 6a.m – 7a.m and over 53% of them cease daily operations between 7 and 8 p.m. For owner drivers, 56% and 50% of them start between 7a.m − 8 a.m. and end daily operations before 6p.m respectively. This shows that there is variation in daily working hours among hired and owner-drivers.

Table 1. Drivers’ working hour.

Hired drivers start working early in the morning and continue for several hours till evening aiming to make more money. The situation otherwise for owner drivers is different; most of the time they choose to ply in the morning and late afternoon rush hours. An interview with the owner-driver confirmed that ‘driving to snatch rare passengers during low time is a loss’. The study also observed that there are situations when drivers, mainly hired ones ply long hours until late evening to compensate for the losses they sustain due to fines and time spent on maintenance. Given the situations highlighted before, it was inferred that the sector lacks uniformity in daily working hours.

Driver idle hours

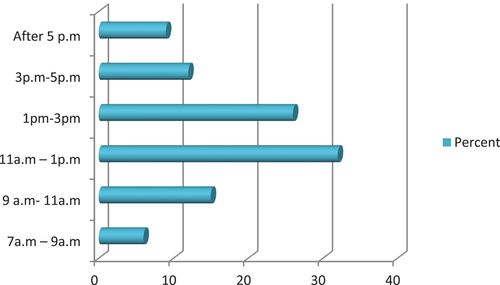

Idle hours are the time spent by drivers waiting for passengers. Time is given special attention in the business because it determines daily earnings. It is customary practice in business that drivers and their assistants (‘Woyalas’) calculate the time they have taken to cover one trip (going and return) or they call it ‘Biyajo’ and compare it with the money they can make. Consequently, for a driver queuing for a long time seeking passengers will result in a lesser trip than predicted and hence affects the daily earnings.

As shown in , most drivers have experienced long daily trips turndown from 11a.m to 3 p.m. However, field observations show that drivers face trip turn downs during morning and evening peak hours depending on the type of land use where they operate and time of operation. Drivers also added that they face trip turndown at routes both ends in different hours of the day. As mentioned earlier, trip turndown affects drivers’ income; drivers devise their way to offset the loss by executing other activities. Most of the drivers said that they spend these off-hours to have meals, rest, and other activities while queuing in their line. On the other hand, some drivers went out to empty terminals to grab rare passengers along the route and return carrying full passengers to take the advantage of time.

Condition of steady income generation

Taxi drivers are engaged in steady income generation activities. The study revealed that out of the 50 drivers, 18 of them said that they ply transport services on a contractual basis of whom the majority (13) are owner-drivers whereas the rest (5) are hired, drivers. As all of these drivers mentioned and field observation confirmed they transport school children during morning and home time hours. As explained above, owner-drivers engaged more in this business than hired drivers. This situation as reported by hired drivers greatly affects their daily earnings since the work schedule overlaps with daily peak hours and the total monthly payment directly goes to the owner. ‘Previously school transport service was a profitable business as I work it without consent of the owner and thus make use of the money for my own sake. However, it has been impossible after the introduction of a zonal taxi system that requires a special route permit from the respective owners association’ says a driver respondent. For owner drivers, this business is highly preferred because it enables them to earn a good amount of fixed monthly income with much less effort and cost compared to the regular schedule, and vehicle owners of this kind work for a few hours in a day reducing vehicle running hours and thereby minimizing maintenance cost. This shows that a significant number of vehicles become off-route as the demand for mobility increases.

Working on scheduled route

All respondent drivers (50) ply along permitted routes during most of their daily working hours. Drivers were asked their reason why they stick to work along defined routes. The responses presented in reveal that 95% of drivers work according to a formal schedule due to strict checking by route controllers and traffic police and hence discourage them to do so. While for the rest (4%) their reason behind is, that they have enough passengers along routes. However, it was learned that they start to work outside of the formally scheduled route in the evening mainly afternoon following the end of the working hour for route supervisors.

Overloading

The vehicles usually used for minibus taxis are different models of Toyota Company. The vehicles have an authorized capacity of 12 passengers, though a field observation confirms that minibus taxis carry 5–8 more passengers than the allowed load limit. However, overloading was more commonly observed among hired drivers than owner-drivers. This is because owner-drivers care more for their property. Most of the drivers said that they tend to overload passengers commonly before morning peak hour and during evening hours when the traffic police are not on duty. However, as reported by some drivers and confirmed by field observations drivers tend to overload passengers at any time of the day on less frequently visited routes by the traffic police.

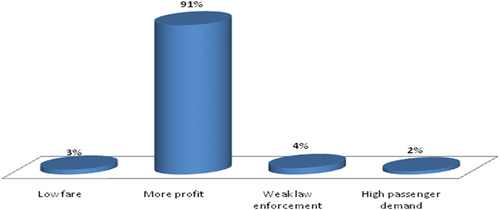

The study also attempted to see drivers’ reasons for vehicle overloading. For 91% of drivers making more profit was the reason behind overloading (). Route fares set by the regulator are not sufficient enough to pay all daily expenditures and make a profit and therefore they resort to loading more passengers than the permitted capacity.

As mentioned before, taxi drivers, mostly hired ones depend on their daily earnings to make a living and hence they aspire to earn more profit out of their daily operations. Four percent of drivers said that weak law enforcement was the reason behind overloading. Three percent of drivers also claim that high passenger demand during peak hours was too high to accommodate existing vehicles. Field observations show that passengers push the taxi crew to carry them and even did not look out sitting in a congested vehicle as they are concerned about reaching their destination on time. Overloading, on the other hand, is one among several sources of contention between passengers and taxi crew (drivers and their assistants) as the latter tends to carry more passengers in a crowded manner. Overloading is perceived as appropriate and rightful travel conditions by taxi crew.

Overcharging

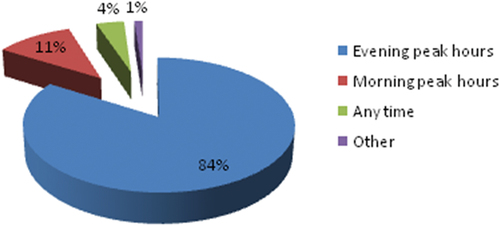

Setting unofficial trip tariffs is also one of the observed common operational practices of the business. The study revealed that all of the interviewed drivers ask passengers to pay more than the stipulated rate. They also report that the money collected through overcharging goes to subsidize operation costs to raise daily net gains. The drivers were also asked at what particular time of the day they overcharge passengers. 84% of drivers increase fares during evening hours when most vehicles are going out of operation while 11% of drivers replied that they did so during morning peak hours. Four percent of them respond that they practice it at any convenient time of the day ().

Instead of adding a certain amount directly, drivers and their assistants devise several strategies of overcharging to protect themselves from possible arguments with passengers. One of the commonly observed strategies is breaking down longer routes into smaller sections and hence producing multiple fares.

The other strategy was fixing a flat rate for all distances covered within a single trip. In this case, passengers were forced to pay the amount set for the route’s endpoint regardless of the distance they commute. Like overloading, overcharging is also another source of dispute between passengers and the taxi crew.

4.4. Problems faced by taxi drivers in the city

The study also sought to examine the challenges drivers face in their daily operations. Concerning this, it was described by drivers that they work in a very tight environment as several groups are involved within the sector to maintain their best interests.

Related to government regulation

Regulations such as route zoning, the rise in the number of fines, and keeping the record of drivers’ violations against traffic laws put pressure on daily operations and thereby reduce earnings. Most drivers said that, given the current operational and economic situations, breaking rules are inevitable practice in the sector and cannot be fully avoidable. They also felt that the government expelled them from the market as if they were solely responsible for the deterioration of the city’s transport.

‘I may get fined twice or more than in a single day for breaching rules while the new traffic regulation issued to revoke the driving permit of drivers like me having a few records of violations threatening means of livelihood. I do not want this to mess up my life, said one respondent driver. This indicates that it has raised concern among drivers about the sustainability of their job.

In connection with this, the study observed that, after the announcement of the due date for the enactment of the new traffic regulation, the city has staged a day-long mass strike called by taxi drivers against its implementation. In addition, tough regulation creates a conducive atmosphere for traffic police to harass taxi drivers even without committing an offense. In most cases, taxi drivers respect the law on the streets as long as the traffic police are present in the area. In some cases, it is common to see that the traffic police deliberately take a hide not to be easily identified by taxi drivers. Most of the driver respondents stated that the traffic police always focus on them rather than treating all with equal eyes. Even though regulations have been considered as one of the challenges to working as a driver, non-compliance has taken place as mutual benefit exists between the drivers and the traffic police.

Compliance with rules and regulations

The study revealed that all respondent drivers said that they were aware of all traffic rules and regulations. However, the majority of them choose to break them, as they claimed that it is customary in the business. The study observed that the majority of drivers were frequently fined for the offense of loading beyond vehicle capacity while few drivers were penalized for working out of the route. Field observations also found that overcharging, breaking rules and closing lanes for loading passengers are other commonly observed offenses. However, none of the respondent drivers report that they have been fined for asking passengers to pay more than official route fares.

Fines and payoffs

The payoff is a payment by the driver to the traffic police in exchange for letting him free from fines for violating traffic rules. All of the respondent drivers said that they pay payoffs to traffic police not to get fined. The drivers were asked why they chose to pay bribes to traffic police. In this regard, they replied that the high fines charged for traffic offenses that may take all of their daily earnings encouraged them to negotiate with the traffic police. One driver stated ‘I have been caught several times by traffic police while carrying more passengers beyond vehicle capacity. Each of these offenses results in a fine of 140 Birr. However, I negotiated with the traffic police to drop the case at some fee’. The other reasons cited by respondents were the presence of time-consuming and extended procedures with government offices responsible for collecting traffic fines which affect daily earnings. Drivers report that a driver should go first to one of the branch transport offices where his record is found to pay fines and then to the police station to get back his driving license.

4.5. Organization of paratransit minibus taxi transport

Owners’ associations

In Addis Ababa, minibus taxi owners are organized into several route associations after a directive issued by the regulator in 2011 as part of an effort to find a solution for the city’s public transport deadlock. According to the manual issued by the Federal Transport Authority to regulate public transportation in Addis Ababa in 2011, minibus taxi owners organized themselves into route associations with the main responsibility of designing and regulating route schedules as well as operations within their respective zones.

Organizational structure of minibus taxi owners association

Minibus taxi owners’ associations have their institutional organization to carry out route operations and members’ compliance with it. The highest decision-making body of the owners association is the general assembly composed of all vehicle owners that belong to one of the five transport zones in the city. And each of these has its charter ratified by the general assembly which is a legal document governing the general activities of associations. In addition, admittance to each association is considered based on the number of vehicles that belong to each of these associations to prevent the emergence of a monopoly. Owners’ association management board members are elected by the general assembly. The operations coordination unit, accountable to the general manager has the responsibility to run the overall activities of the association.

Despite the previously stated responsibilities and organizational structure of owner unions, key informant interviews with association heads and field observations evidenced that the organizational structure of the associations was weak and therefore less likely to influence service characteristics. For instance, route operations and monitoring are the sole responsibility of route associations. However, most of these activities are done by sub-city transport branch offices. Key informant interviews with route association officials show that they (route associations) just focus on regularly carrying out monthly route rotation and issuing route permits for member vehicles to ply contract transport services. Furthermore, among those associations contacted for an interview, all of them (6) do not strictly follow the institutional organization as shown above. This is because; all of the interviewed association officials have shared the same reason that they are financially weak and have less interest to structure accordingly.

All association officials report that the business is becoming less attractive and profitable for them as government regulations get tight. Key informant interview with driver and chairman of one owners’ association stressed that ‘increased regulation by the government, the increased price of spare parts and fuel and the amount of the tariff as well as the complexities of the relationship between vehicle owners and the drivers, are reasons why the business is disappointing for owners’. All of the respondents considered that the tariff fixed by the government is not sufficient enough to cover their expenses as it is primarily set taking into account the price of fuel which abandons other costs such as the cost of spare parts and maintenance. In addition, the minibus taxis are facing fierce competition as more minibusses (code 3) join the market without the need to register with the owners’ association. In connection with this, association leaders added that they are free to work everywhere without getting into the zoning system. Most of these vehicles have diesel-powered engines and are relatively new compared to their old-aged vehicles making them advantageous by reducing operating costs.

According to one owner-driver, most members of the association he is chairing now have less interest in staying in the business let alone thinking about strengthening associations. The sector has become less attractive to new entrants to invest. Even those already in the business are also leaving it for other options. As a result, all of the associations confirmed that neither the existing members increased investments nor they accepted new entrants in the past year. Key informant interview with an expert in transport authority evidenced that for the past 4 years from 2011 to 2014 the number of minibusses that joined the business was only 47 and no new entrants from 2015 onwards. This was also confirmed during field observation that code-3 minibusses became dominant over the white and blue code-1 minibus taxis.

4.6. Government institutions regulating minibus taxi transport

Regulatory bodies in this study refer to pertinent government organizations that enforce transport regulations. Government organizations that directly regulate taxi transport in the city are presented in .

Table 2. Government institutions regulating the minibus taxi sector.

The government has attempted to decentralize the power which was concentrated under the city’s roads and transport office which was a branch office under the Federal Transport Authority. From 2010 onwards, the office was reorganized under the Addis Ababa city administration to manage the city’s public transport. Since then the office has been handling transport planning and traffic management activities in the city, as well as assigning routes to taxis and regulating their operations. It also provides driving licenses, inspects their vehicles, and obtains certifications for driving license companies. More recently (2017), fare regulation which was the jurisdiction of the federal government has now the mandate under the city’s transport authority. The need to establish an independent institution managing the city’s public transport is, according to the Deputy General Manager of the City’s Transport Authority, for better management and control which is currently facing difficulties in controlling the entire city transport system.

According to the Addis Ababa government executive and municipal services organs re-establishment proclamation No. 35/2012, an independent transport authority was established accountable to Addis Ababa City Roads and Transport Office. The following are some of its main powers and functions:

Superiorly control, direct, issue, or suspend the license and the operation system of mass and freight transport;

Issue standards, manuals, and levels of the mass and freight transport of the city;

Cause formation of centralized mass transport system, prepare deployment schedule; study and submit tariff to the concerned body;

Study the supply and demand of mass and freight transport; and

Issue directives on the general mass and freight transport of the city and implement the same upon permission.

Furthermore, the authority has established branch transport offices at the sub-city level mainly to coordinate and control route allocation as well as distribution of public transport operators.

Even though the city’s transport authority is responsible for the functions stated above, duplication of responsibilities and lack of coordination among some government regulatory institutions are observed. For instance, the Ministry of Transport has formulated a transport policy for Addis Ababa in 2011 while the Ministry of Urban Works and Development set a national urban transport policy.

4.7. Regulation of minibus taxi transport

The study sought to see the total regulatory environment applied to the minibus taxi sector concerning entrance, fare control, service/operational characteristics and vehicle physical fitness, and degree of compliance to these regulations.

Market entry

After the deregulation of the public transport market in 1992, the minibus taxi business is free to any intending operators as long as they meet certain provisions. The vehicle must be registered before getting into operation. The vehicles pass through a few procedures such as complying with roadworthiness tests, business permit registration from the trade office, taxpayer registration, and membership with one of the taxi owner associations. In addition, exit from the market is also free. However, the city transport authority has issued a regulation to ban vehicle owners who want to change to another business alternative. One of the key informants with the city’s transport authority said that the decision was made as a short-term solution to keep the taxis as most of them were applying to shift their code-1 plate to code-3 to have better operational freedom. He also adds ‘If changing to Code-3 is allowed, no one would be left under the Code-1.``

Fare control

The minibus taxi operators of the city have tariffs subject to administrative control by the government. Neither the individual operators nor route associations are allowed to fix trip fares. Addis Ababa Transport Authority is a responsible government agency to set trip fares and their implementation. In addition, fares are subject to revision at any time based on fuel retail price adjustment by the Ministry of Trade. The tariff rate for taxis depends on the distance traveled and hence there are different fares for short, medium, and long-distance ranges ().

Table 3. Minibus taxi tariff rates.

Despite the recent (2020) city’s transport authority’s major fare adjustment that takes into consideration current price levels of vehicle maintenance and spare parts minibus taxi operators do not strictly comply with these tariff regimes on one hand, in the eyes of owners and drivers; tariff limits are too low to cover all expenses since it considers only fuel prices. On the other hand, responsible regulatory institutions have not devised a mechanism to follow up its implementation along routes. One of the key informants of the Arada transport branch office route supervisor said that, while we are on duty, special attention is given to whether the taxis ply according to assigned routes and their presence in line with the work schedule. He further explained that it is very difficult to monitor their compliances to set fares given that the current institutional organization of the minibus taxis is not suitable to make it effective.

Service characteristics /route operations

As explained before, the city’s minibus taxi transport operates based on a zoning system. Since the introduction of the minibus taxi zoning system in 2011, the city’s taxi transportation has clustered into five zones and the taxi owners which provide transport services within these zones are organized under 13 Taxi Owners Associations. According to the directive issued by the Federal Transport Authority to regulate public transport services of Addis Ababa in 2011, the main objective behind the implementation of the zonal taxi system was to create a fair service in all areas, prevent taxi operators from dividing long routes to make more money, and enable passengers to pay the appropriate fare.

The vehicles which belong to one of the owner associations are assigned to ply along specific routes of the zone by their respective route unions. Each of these vehicles is required to post signs ‘tapella’ indicating their takeoff and destinations providing service from 6:30 am until 9:00 pm and it is not allowed for them to cease operations during morning and evening peak hours (6:30 am-9:00 am and 3:30 pm-9:00 pm). Public transport route supervisors inspect whether each vehicle gets into operation within the assigned route. Vehicles should get a permit from the same association to become off-route for special cases such as school contract service, for the private use of the owner as well as for maintenance.

More or fewer taxi drivers work following the stated rules in the morning rush hours and less compliance with the same operational procedures as of mid-day. This is partly because of the presence of transport supervisors in taxi terminals. This is also confirmed by one key informant of the Arada sub-city route supervisor that the transport office deploys all of its workforces in the morning hours as the demand for transport services comes at the same time. For evening peak hours, however, he further added that it comes after the end of the regular working hours. All route operations are carried out by sub-city branch transport offices which have their limitations concerning the availability of resources and manpower.

Vehicle fitness requirements

Vehicles for the use of public transport () have to be registered by the concerned government agency. Vehicles are inspected for roadworthiness at the time of registration by the transport authority. Thereafter inspections are repeated annually. So far the authority has carried out inspections according to the parameters equally applied for non-public use. In addition, the authority conducts casual vehicle observations on the road. However, field observation showed that there were vehicles that risked the safety of passengers. According to one key respondent in Addis Ababa transport authority, the vehicles being used as taxis in the city are very old with an average age of more than 15 years, and hence escalated operating and maintenance costs which are unaffordable for owners. Most of the time these unsafe vehicles pass annual inspection tests either by giving bribes to the person in charge or temporarily replacing parts acquired through renting.

Drivers of minibus taxis are required to pass a test to obtain level 3 licenses to operate the existing fleets. Interviews with respondent taxi drivers and key informants in the transport office indicate that there is no other special criterion required to operate public transport once the driver is certified. Furthermore, there is no minimum age set for drivers who operate minibus taxis by the regulator.

5. Conclusions

Paratransit transport is a fundamental means of transport for urban inhabitants. The continuously growing demand for mobility, on one hand, and the absence of well-organized institutions for administration purposes, on the other hand, gave rise to the inability of urban centers to provide efficient public transport.

Addis Ababa as the capital city of Ethiopia has commonly shared most of the problems that urban centers face in providing efficient public transport. Among several public transport providers in the city, the code-1 white and blue minibus taxis are the dominant operators as they travel over 1 million passengers daily. However, the service struggles with inefficient operational, organizational as well as regulatory constraints.

The tightening of regulations against the sector created a conducive ground for traffic officers for payoffs, which in turn affects the operators’ daily gains. All of the participants in this study have given payoffs for traffic officers at different times. Drivers pay payoffs in exchange for not being charged by the traffic police. They choose to do to evade the high amount of traffic fines and not to waste time unnecessarily by following the right procedures that could force them to stop operations and hence affect daily revenues. They also encounter high daily operational expenses as they are forced to pay for route attendants at terminals and along with the route for loading passengers.

The paratransit taxis of the city are organized into 13 associations operated in five zones. However, the associations do not have formal organizational structures and lack the institutional and financial strength to impact service characteristics. This is because individual members show less interest in doing the business as regulations become tight and the business environment favors the driver side.

There is no entry restriction in place to get into the business. The vehicles are going to be registered after passing roadworthiness tests and route permits issued to get membership acceptance in one of the owner’s associations. However, exit restrictions are there to keep the taxis operating under code-1 plate. The tariffs are determined based on travel distance and hence different fare ranges for short, medium, and long distances. Changes to travel fares are done along with changes in retail fuel prices. However, the fare sets are violated by the taxi crew due to the absence of enforcing instruments both by the regulator and associations.

Most vehicles have an average age of more than 15 years and therefore have low technical performance even to fit the standard. Given the current economic and operational characteristics of the sector, putting strict regulations to meet road standards would accelerate the extinction of the sector that struggles for survival.

Generally, the sector can be labeled as formal as the entire operation is subject to certain regulations to follow. The paratransit minibus taxi sector is recognized by the government with enforcement rules and regulations that control market entry as well as exit. On the other hand, informality also characterizes the paratransit minibus taxi sector due to the sector’s institutional organization and its framework which is largely dominated by customary practices which cause a complex owner-driver relationship. Finally, the study deduces that, on one hand, problems related to service provision and, on the other hand, the sector’s future well-being is largely affected by its informal arrangement.

The paratransit minibus taxi transports play a significant role as a means of mobility for the city’s population. The government has formulated several directives and procedures to improve the service provided by the sector. Among the efforts made by the government, organizing vehicle owners into associations and route zoning systems are the most important ones. Despite these efforts, service quality is poor and even the sector has been facing extinction due to its semi-formal institutional organization.

Hence, the prevailing customary operational practices should be substituted by formal procedures by pushing owners’ associations to follow strict organizational structures. For owners’ associations, instead of a mere grouping of vehicle owners, it is better to organize themselves as a share company to manage resources effectively. All route operation activities such as designing, managing, and monitoring should be conducted by associations. The on-board cash payments to driver assistants have to be replaced by a system of tickets paid by users and the remuneration system of drivers and their assistants should be replaced by a wage system.

Government agencies should have a supervisory role to check if associations are working according to standards. Since public transport is a public good; the government should consider policy options such as exemption of taxes for vehicle purchase, spare parts, and subsidizing fuel costs. Finally, the study suggests reorganizing and formalization of the sector needs the involvement of all stakeholders of the sector to avoid potential challenges at the time of implementation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Addis Ababa City Administration Road and Transport Bureau (2018).

- Addis Ababa City Government, Office of Mayor. (2011). Addis Ababa city of glamorous cultures, Addis Ababa city government.

- Addis Ababa Transport Authority (AATA). (2017). Waiting time to get public transportation service at public transport terminals and survey to identify related problems.

- Ajay, K., & Barret, F. (2008). Stuck in traffic urban transport in Africa. an Africa infrastructure country diagnostic. The World Bank.

- Cervero, R. (2000). Informal transport in the developing world. UN-HABITAT.

- Chakwizira, J., Bikam, P., Dayomi, M. A., & Adeboyejo, T. A. (2011). Some missing dimensions of urban public transport in Africa: Insights and perspectives from South Africa. The Built and Human Environment Review, 4(2), 56–84.

- CSA (2012). Projected figure population on 2007 national population and housing census of Ethiopia.

- Dumedah, G., & Eshun, G. (2020). The case of paratransit - ‘Trotro’ service data as a credible location addressing of road networks in Ghana. Journal of Transport Geography, 84, 102688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102688

- Gebeyehu, M., & Takano, S. E. (2004). Evaluation of bus routes performance in the city of Addis Ababa using the stochastic frontier model. Infrastructure Planning Review, 24, 447–457. https://doi.org/10.2208/journalip.24.447

- Golub, A. D. (2003). Welfare analysis of informal transit services in Brazil and the effects of regulation. University of California.

- Kebede, L. (2019). Evaluating Quality of Service on Public Bus Transportation and Improvement Strategy in Addis Ababa: A Case Study on Sheger Mass Transport Enterprise. Unpublished masters’ thesis in Civil Engineering, Addis Ababa University.

- Mekuria Wondimu. (2012). Performance and challenges of Zonal taxi transport system in Addis Ababa. Academic Journal, 25–26.

- Meron, K. (2007). Public transportation system and its impact on urban mobility: The case of Addis Ababa. Faculty of Technology, Addis Ababa University.

- Meshesha Tilahun. (2009). Public Transportation System in Addis Ababa. Journal of Intelligent Transportation and Urban Planning, 2(3), 81–88.

- Murray, A. T., Davis, R., Stimson, R. J., & Ferreira, L. (1998). Public transportation access transportation research part D: Transport and environment. Elsevier.

- Tembe, A., Nakamura, F., Tanaka, S., Ariyoshi, R., & Miura, S. (2019). The demand for public buses in sub-Saharan African cities: Case studies from Maputo and Nairobi. IATSS Research, 43(2), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iatssr.2018.10.003

- Thondoo, M., Marquet, O., Márquez, S., & Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2020). Small cities, big needs: Urban transport planning in cities of developing countries. Journal of Transport & Health, 19, 100944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2020.100944

- UN. (2014). World urbanization trends 2014: Key facts.

- World Bank (2002).Scoping study: Urban mobility in three cities. SSATP Working Paper No. 70 Washington DC.