ABSTRACT

In Finland, based on the Land Use and Building Act, the city has a monopoly in urban planning and design. Through the planning monopoly, the city manages the urban planning process and thus consciously develops the urban structure. Based on the Act, the number of parking spaces stipulated for the property in the local detailed plan and building permit must be provided in connection with the construction work. The obligation of providing a number of parking spaces stipulated in local detailed plans affects the society in many ways. The provision of parking spaces is a key economic factor in construction costs. Car parking is also linked to changes in people’s mobility habits and car ownership. Occupancy rates for obligation parking spaces and other parking spaces vary over time and location. Car parking also impacts urban flood management. Rainwater volumes in condense urban structure can be significant and require heavy technical stormwater management solutions. Urban design is a key action of a city’s competence in terms of preparing for future changes. The number of parking spaces and stormwater management are key tools in urban planning that can be used to define resilience in the northern context of urban planning.

1. Introduction

Car parking problems in urban areas are known to increase traffic congestion, driver frustration and increase fuel consumption. In addition, lost time due to parking leads to financial losses. At the same time, changes in people’s mobility habits and behavior affect the functioning of the urban structure. The future arrangement of car parking will have an impact on the development of urban areas and on the cost of housing. And on a larger scale, climate change is the most important factor affecting the development of the urban structure and should be taken into account in the future as a part of emerging urban mobility solutions.

The provisioned number of parking spaces stipulated in the local detailed plans affects the whole society in many ways. Car parking is one of the key factors of urban planning, as the car parking solutions affect, e.g. urban mobility decisions and housing production. Car parking is linked to changes in people’s mobility behaviour and car ownership. Car parking surveys prepared by cities (Oulun kaupunki, Citation2018a) have shown that the utilisation rate of parking spaces in city centres is below 70%. The provision in the local detailed plan for the quantity and the quality of parking spaces is a key economic factor in construction costs (Nykänen et al., Citation2013; RAKLI, Citation2015). In addition, the car parking policy affects the city’s revenue through both the fees collected for parking and the revenue generated by the land sold or leased for construction projects.

Car parking has an impact on urban flood management. Built parking spaces increase impervious surfaces on the site and thus makes it more difficult to manage stormwater with green solutions. As a result of climate change, precipitation will increase in northern Finland and the amount of stormwater floods is growing (Jylhä et al., Citation2009). It is estimated that climate change will increase precipitation in the northern regions about 20% by 2100 (Kuntaliitto, Citation2012). At the same time urbanisation continues. In Finland, total urban area has increased more than 40% over the last 25 years, and currently more than 60% of urban areas are densely populated areas (Rehunen et al., Citation2018). Due to urbanisation, the role of green infrastructure has been increasing in urban structure (Eckart et al., Citation2017). Rainwater volumes in built-up downtown areas can be significant and require new innovative grey solutions for stormwater management.

The permitted building volume and the size of the plot stipulated in the local detailed plan determine total area required for car parking. The number of obligation parking spaces to be implemented on the property is given in the local detailed plan, e.g. x parking space/y gross floor m2 (x ap/y k-m2). Obligation places are assigned to the plot as ground-level placement or structural placement. One parking space (minimum 2.5 meters x 5 meters) needs at least 27 square meters (m2) including space for reversal, and therefore, parking spaces take up a significant part of the free space left on the property. The city decides on car parking standards and has the primary responsibility for arranging public parking areas. According to a study by the Association of Finnish Municipalities (Kaikkonen, Citation2012), the municipality could compile the obligation places and other places in its area in a register, so that the parking place register managed by the municipality could centrally manage the problem of parking place demand and vacancy.

In urban planning, promoting resilience means finding new ways of adapting land use to a changing global environment threatened by risks and uncertainties such as climate change and resource depletion (Davoudi et al., Citation2013; Rantanen & Joutsiniemi, Citation2016). In this context, when assessing the changes in urban planning in the context of car parking, the concept of resilience could be considered a promising framework to interlink car parking, changes in mobility habits and urban flood management within urban planning in the context of northern cities. The concept of resilience has been applied to ecology (Holling, Citation1973, Citation1996) since the 1970s. Walker et al. (Citation2004, p. 2) defined resilience as ‘the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganise while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks’ (Walker et al., Citation2004). Converting this definition to urban planning in the context of car parking, increasing resilience would require the following aspects to be taken into consideration: the city takes necessary actions to manage the total number of parking spaces in urban structure, but also adjusts urban design to adapt to occasional changes in demand of parking spaces and changes in amount of impervious surfaces.

The aim of this paper is to convert the concept of resilience into an operational framework for urban planning. Resilience will be studied in the context of northern cities that can be used by policy- and decision-makers, for evaluating the resilience in urban planning in the context of car parking. The City’s ability to make binding decisions and to promote change is a prerequisite for the comprehensive solution this research aims to consider and the possibilities it generates. Despite the steering obligations and regulations, issued by authorities in the Land Use and Building Act (Citation1999), there is little research about resilience in urban planning in the context of car parking. Recognising the gap between the results of processes and the goals of the processes, the research question of this paper is as follows: How does the definition of resilience appear on local detailed plans in the context of car parking at three study areas in the City of Oulu?

2. Theory

2.1. Legislation of land use in Finland

In Finland, the municipality has a monopoly in urban planning and design (Planning Act, 145/Citation1931; Building Act, 370/Citation1958; Land Use and Building Act, 132/Citation1999). Through this monopoly, the city manages urban planning processes, and thus consciously develops the urban structure. Regulations used in urban planning must be based on the legislation in force at the time (). Therefore, carrying out the local detailed plan must comply with the legislation of land use in force at the time when the local detailed plan was ratified.

Table 1. Legislation of land use in force in Finland

Based on the Land Use and Building Act (Citation1999), currently in force, provisions on providing parking spaces are specified in the Act (132/Citation1999) in section 156 subsections 1 and 2 as follows:

The amount of parking spaces stipulated in the local detailed plans and in building permits must be provided in connection with the construction work.

When the local detailed plan so stipulates, the local authority may designate the required parking spaces a reasonable distance away and assign it to a property.

A building permit may be granted when it is in keeping with the local detailed plan. According to the Land Use and Building Act (Citation1999) section 130, the building permit should be applied for with the local building control authority. The content requirements of the building permit are regulated in the Land Use and Building Act (Citation1999) in section 125. Based on the provisions of the Act (132/1999), the building permit is required for construction of a building, or alteration work, which is comparable to building construction, and for increasing building gross floor area. If the building permit applied for has to deviate from the local detailed plan, e.g. in terms of number of parking spaces, gross floor area, or purpose used, the permission to deviate must be applied for separately from the local authority before it is possible to grant the building permit. However, as regulated by the Act (132/Citation1999) section 171, a right to deviate may not be granted when a deviation complicates implementation of the local detailed plan.

Through the urban planning process, the role of the urban designer, based on the Land Use and Building Act (Citation1999) section 20, is to define the physical urban environment. However, property owners and users determine how urban structure eventually comes into fruition. The legally binding local detailed plan allows for construction, but does not force it. The provisions stipulated in the local detailed plan only apply to the area delimited in the planning process, which may consist of a single real estate or multiple properties. Property-specific implementation may in addition need to be controlled through other agreements, such as land use agreements, regulated in the Land Use and Building Act (Citation1999) section 91 b, and car parking agreements. Despite the size of the local detailed plan area, the building permit, as defined in the Act (132/Citation1999) section 131, is building site-specific and granted separately.

2.2. Resilience in the context of car parking provisions

Resilience theories recall that change is both an inevitable and a necessary condition for the development of systems (Rantanen & Joutsiniemi, Citation2016). Resilience in engineering systems generally emphasizes the system’s recovery and preservation of functionality (Wied et al., Citation2019). According to Rantanen and Joutsiniemi (Citation2016, p. 205), engineering resilience approach has been highlighted in urban planning processes (Rantanen & Joutsiniemi, Citation2016). Maximum conditions have been stipulated in the local detailed plan, and new interpretations can only be provided through new planning processes. However, simply recovering from predefined disruptions to maintain functioning is not enough. The system should be able to internalise the dynamics of change and transform together with its environment (Wardekker et al., Citation2010).

Assessing the concept of resilience through parking regulations could be a step forward in discussions on promoting resilience in urban planning. Thus, in the context of car parking regulations, it is necessary to clarify the notions of ‘adaptability’, ‘transformability’ and ‘robustness’ as important definitions that several authors have suggested when discussing the concept of resilience (Davoudi et al., Citation2012; Folke et al., Citation2010; Holling, Citation1996; Rantanen & Joutsiniemi, Citation2016; Walker et al., Citation2004).‘Robustness’ in the context of the car parking provisions can be defined as an attribute of resilience when fulfilling the following criteria: a) variables of provisions should be easily identified from the local detailed plan, b) equations of variables should be easily resolved, c) used key symbols and written regulations should be binding and d) provisions be taken into account over times. Provisions that satisfy the aforementioned conditions can have a strong capacity to respond to the changes in urban planning and design because the impact assessment of provisions can be done with easily identifiable parameters from local detailed plans. The provisions based on equations such as 1 parking space/100 gross floor area (1 ap/100 k-m2) or similar exact equations could be defined as ‘robustness’, where all variables can be measured from the local detailed plan.

‘Adaptability’ in the context of the car parking provisions can be defined as attribute of resilience when fulfilling the following criteria: (a) the variables of provisions may be linked to identifiers that cannot be exactly defined from local detailed plan, (b) the provisions may include several purpose uses, (c) used key symbols and written regulations may be indicative and (d) the provisions may have vague, unclear and semantic contents and therefore may be open to interpretation. Therefore, such provisions may allow forward-looking planning but also include the risk that the plans may change. The provisions include flexibility but also uncertainty that the urban environment might not be implemented in a predetermined way. Hence, the provisions such as 1 parking space/80 gross living area (1 ap/80 as-m2) or similar exact equations could be defined as ‘adaptability’.

‘Transformability’ in the context of the car parking provisions can be defined as an attribute of resilience when fulfilling the following criteria: (a) the new provisions with the new variables must be defined to ensure that the designated solutions can take into account urban development, and (b) the provisions include conditionality as a part of the solution. Thus, the provisions may allow for shifting the responsibility of the implementation and may also require other agreements to deal with parking space arrangements. Therefore, the provisions such as [a], meaning that the required parking spaces will be addressed away from the building block and assigned to a property, could be defined as ‘transformability’.

3. Methods

This paper analyses the car parking provisions on three different types of study areas in the City of Oulu (); (a) the area of new construction – Alppila-Välivainio area, (b) the area of infill development – Taka-Lyötty area, and (c) the area of sudden change – Linnanmaa-Kaijonharju area. The research method used in this paper is content analysis well suited to typological research.

3.1. The three study areas

The area of new construction is a part of the Välivainio neighborhood. Välivainio and its surroundings belong to the Alppila boulevard development project, which is one of main objectives of the City of Oulu (Oulun kaupunki, Citation2018b). The study area is 16.75 hectares. The first local detailed plan, the ‘Taka-Tuira local detailed plan’, was drawn up in 1951 by architects Otto-Iivari Meurman and Aarne Ervi and covered the areas north of the river in the city of Oulu. In the local detailed plan Meurman and Ervi pay attention to the possibility for a rapidly increasing car fleet in the future. The first local detailed plan came into force in 28.12.1951 and the latest in 21.1.2020 (). Based on the key objectives of the Alppila boulevard development project, the nature of Kemintie will change from a fairway environment to a boulevard, which is part of the city corridor of the master plan, an urban development zone that connects the northern regional center of Oulu and the Linnanmaa campus area. In the future the car parking will be centralised in a multi-story car park that may also have other activities on the ground floor.

The area of infill development is Taka-Lyötty quarter and a part of Karjasilta quarter. The study area is 53.75 hectares. The study area includes two different kinds of city quarters; Karjasilta is the residential area built during the reconstruction period in the 1950s and has remained exceptionally wide and cohesive. The Karjasilta residential area has been assessed as a nationally significant built cultural environment (Museovirasto, Citation2009), while the Taka-Lyötty area has developed over the times in terms of purpose and land use of the area. The first local detailed plan came into force in 26.10.1944 and the latest in 9.4.2019 (). In the future the development of the Taka-Lyötty city quarter from shopping and retail districts to residential areas will continue and the car parking solutions and remaining green areas will play a significant role in creating a favourable living environment in a sustainable way.

The area of sudden change consists of a part of Linnanmaa quarter and a part of Kaijonharju quarter. Linnanmaa and its surroundings belong to the campus development area, which is one of the main objectives of the City of Oulu. The study area is 91.82 hectares and comprises part of the campus area, including parts of the University of Oulu and student housing areas next to the university, and Kaijonharju center area. The regional development of the Linnanmaa area began in the 1970s, when the city decided to move the University of Oulu away from the city centre to Linnanmaa. The first local detailed plan came into force in 22.7.1974 and the latest in 26.7.2006 (). Based on the first local detailed plans established by architect Kari Virta, the car parking areas were mainly addressed to separate parking block areas in order to make the implementation and use of parking spaces flexible, a preference due to the character of the functions in the area. The Linnanmaa-Kaijonharju area is one of the Renewable Oulu main objectives. According to the principles of the objectives of Linnanmaa-Kaijonharju area the car parking in the future will be based on regional parking garages due the development principles in the area (Oulun kaupunki, Citation2019).

3.2. Data

The research data are based on the outcome of granted local detailed plans, deviation decisions and building permits in three study areas in the City of Oulu. The research data comprise three parts. (1) Local detailed plans from the study area comprise the primary source of results. (2) Deviation decisions from the study area act as a complementary source of results for local detailed plans. (3) Building permits were not possible to receive completely because they were not available from the archive. That is why the features that could be found in all granted building permits received from archive were utilised as quantitative data. These data sources were supplemented by analysis of cause-and-effect relations in a holistic way.

3.2.1. Local detailed plans

The local detailed plan is a legally binding document to manage the legal relationship between private and public authorities in land use and urban planning. Developing the urban areas with local detailed plans, could be considered as a service, provided by public authorities, to ensure the public interest and regulate conflicts between private interest (Jalkanen et al., Citation2017, p. 76). This notion may allow us to evaluate that the local detailed plan reflects the values of the time. The development of land use and urban structure with local detailed plans also has a strong connection with land ownership. Local detailed plans must take into account the equal treatment of landowners. The local detailed plan cannot be unreasonable for the landowner. Thus, the significance of a first local detailed plan seems evident for the development of the areas.

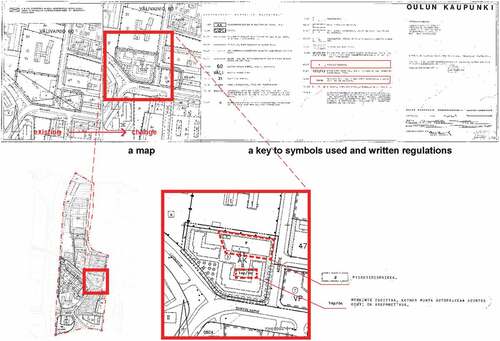

The required content to the local detailed plan is stipulated in the Land Use and Building Act (Citation1999). The local detailed plan should be presented by a map and a key to the symbols used and written regulations. The primary content to be presented on a map is based on the Act (132/Citation1999) section 55. The local detailed plan should also include a report as a supplementary document to provide the information of the aims and the impacts of the plan and the alternatives. Guidance to the use of key symbols and written regulations are given in handbook ‘Opas 12 Asemakaavamerkinnät ja -määräykset’ (Haapanala et al., Citation2003). There is the examples of regulations and symbols that are suitable for different purposes have been described and provided.

In the local detailed plan the used regulations are divided into two different main groups: system of general regulations and system of index regulations. The general regulations are the provisions related to the whole or at least several parts of the local detailed plan, and the index regulations are related to the subscription of the purpose use of either a block or other areas. In urban planning practise, in addition to legally binding symbols and regulations, indicative provision symbols may also be used in the local detailed plans. These symbols describe the urban designers’ view of the recommended solution without legally binding effect.

The necessary local detailed plans (n = 88) for the research were collected in February of 2020. Due to the legally binding role of local detailed plans, all confirmed plans were obtained from the archive, validated, and replaced. Based on the results, the urban structure in the study areas have mostly been defined in the first local detailed plans. Some of the local detailed plans are based on the Planning Act (Citation1931), repealed by the Building Act (Citation1958), and the Land Use and Building Act (Citation1999). Nevertheless, some part of those still applies (). In this paper, the focus is in the key symbols and written regulations in the local detailed plans in the context of car parking, both the provisions stipulating the number of parking spaces to be provided and the provisions stipulating the quality or location of parking spaces. The used provisions in local detailed plans are taken into account only in connection to study areas.

Table 2. The period of each local detailed plan acceptance

3.2.2. Deviation decisions

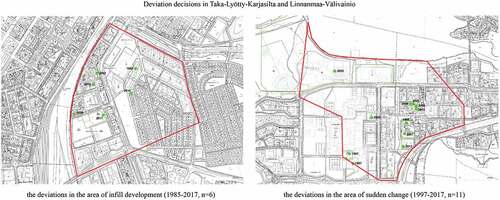

Based on the Land Use and Building Act (Citation1999) section 171, the city may allow deviation from the provisions stipulated in the local detailed plan for a particular reason. However, the deviation should not impede the implementation of the local detailed plan. Also, the local building authority may grant a minor deviation in connection with a building permit. The particular reason may be in connection with the plot or area of use, and the deviation must generally lead to a better result, e.g. in terms of a cityscape, environment or use of building. Therefore, possible deviations were explored in context of car parking provisions. The deviations from the study areas () are used as a complementary source to local detailed plans. The deviation decisions (n = 17) were collected in February of 2020.

3.2.3. Plot divisions

Based on the Land Use and Building Act (Citation1999) the urban planning Designated area may consist of building blocks, public areas, street areas and traffic areas where the building block can comprise a single plot or it can be divided into several plots. The plot division should be drawn up in conjunction with the local detail plan either binding or as a guideline. The plot division may also be carried out separately when the local detailed plan should act as a guideline in drawing it up. The plot division should be made binding in central location areas of the city with the local detailed plan. The plot division should be conducted and plot should be registered to the Real Estate Register kept by the cities (Real Estate Register Act, Citation1985) before the building permit may be granted. Thus, the property units that are the outcome of the plot divisions could be considered as a key factor to management of the link between the local detailed plan and the building permit.

In this study, the only received accesses to property identification were received from the existing cadastral index maps and property units. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic that began in March of 2020 in Finland, it was impossible to access the archives to examine the plot divisions previously made for study areas. The city could not respond to the data collection because the data were not available in collective form, and no resources were available to compile the data. Therefore, there was no certainty that all property units that belonged to the study areas could be identified. Thus, it was impossible to link changes between local detailed plans and building permits directly together.

3.2.4. Building permits

The local detailed plan is aimed at construction: its provisions will usually only be complied with when the building permit for a construction or other measure is applied for in the area. Based on the Land Use and Building Act (Citation1999), the building permit application should include master drawings of the building project. Master drawings include site plan, floor plans, section plans and elevation plans (Land Use and Building Degree, Citation1999). Content requirements of the site plan are issued in the National Building Code of Finland (Decree of the Ministry of Environment on plans and ports concerning construction, Citation2015). The calculation of gross floor area and parking spaces should be proved in the site plan unless they are not done as separate statements.

The building permits for this study were collected (photographed) during February and March 2020. As explained before, not all of the property units were identified and thus, there was uncertainty whether it was possible to know and collect all building permits. However, that was not the only obstacle that needed to be overcome. Archive visits showed that some of the building permits did not exist in the archive. Thus, the collected building permits (n = 485) should be considered and used as a randomly selected sample from the study areas.

With regard to building permits, the aim was to find out how the location, amount, and surface material of the parking spaces appear in the plans. The analysis focused mainly on the site drawing of the master drawings. As the building permits were the only documents that could obtain information about how the car parking has been arranged on each property, all received building permits were included in the study.

3.3. Typological research

Because the research data are primarily based on key symbols and written regulation stipulated in local detailed plans, the results of this study are based on exploring the definition of the characteristics of the provisions stipulated in local detailed plans, which is characteristic of typological research. De Jong and Duin (Citation2002, p. 89) states that in typological research ‘the context is variable, and this variability is, therefore, the object of typological research’ (De Jong & Duin, Citation2002). In this sense, typological research could be considered as a continuum for design research (De Jong & Engel, Citation2002).

In typological research each variable is formed around typical or pure variables. Urban areas are developed through local detailed plans in the context of car parking, and thus, the types can be considered as a summary of stipulated provisions in the local detailed plan with common characteristics. Each provision in the collected data is compared to an archetype or ideal type of exemplars and assigned to the class where it most resembles these variables.

The total of 88 local detailed plans consisted of 261 provisions that were related to car parking. Each of these provisions were studied separately, but each provision was also assessed as part of the overall solution of the local detailed plan in the context of car parking. As the planning documents were drawn up in Finnish, the content analyses are based on Finnish meanings (). Most of the provisions could work alone or were linked with other provisions that were also related to parking spaces. Only a few of the appeared provisions needed other provisions to be taken into account when assessing the characteristics of resilience. In these cases, however, the provisions were clearly identifiable from local detailed plans in the context of car parking.

Figure 6. Only the provisions related to parking spaces were taken into account from local detailed plans.

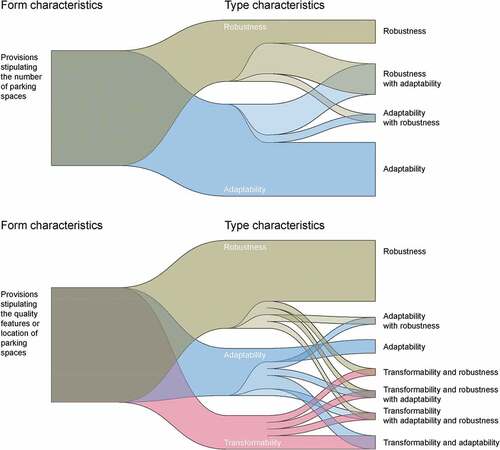

As this paper focuses only on the features of the provisions that are used in local detailed plans in the context of car parking, the provisions were classified using the three characteristics of resilience: robustness, adaptability and transformability. These characteristics were used as characteristics of form and compared to four different structure characteristics: structure: function, identify and feedback (.). Form characteristics appeared recessive or dominant depending on how structural characteristics emergence in each provision. The aim was not to precisely define a category for each provision of local detailed plan, but rather to identify the characteristics they include.

Table 3. Implicit function characteristics

4. Results

Resilience is a multi-interpretable concept referred to in interdisciplinary research and is difficult to define unequivocally. In this paper the concept of resilience in urban planning is approached in the context of car parking. Several authors’ definitions for resilience have been used to discuss the concept. The provisions stipulated in local detailed plans in the context of car parking reflect the solutions used to provide parking spaces in urban design. The characteristics of provisions that emerged in the context of car parking ranged from the independent, unequivocal, easily defined, and legally binding provisions to vague, interpretable, or conditional provisions that could not be precisely defined from the local detailed plan. The results display the manner in which the features of provisions affect these characteristics and thus the resilience of urban planning in the context of car parking.

On a general level, the findings of the provisions used in the local detailed plans showed how the appearance of resilience is affected by planned purpose use and development for the area. The results also highlighted the variations that have been used to deal with different car parking solutions in different situations and purposes.

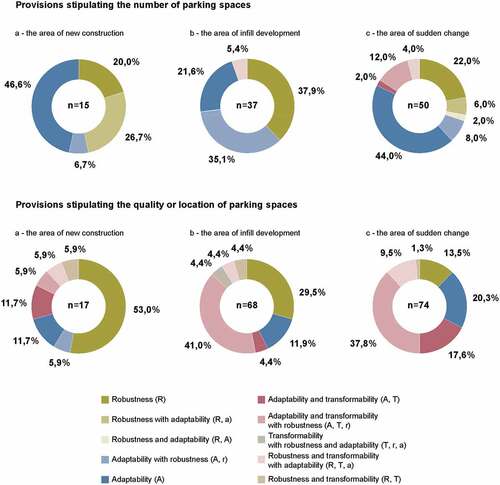

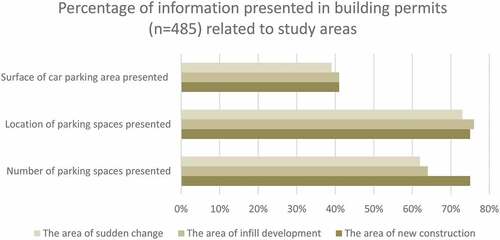

The results from all data sources have been divided according to the three study areas. At the beginning of each subchapter, general observations of how the provisions are presented in local detailed plans. Next, more detailed observations are presented about the appearance of the definition of resilience in provisions providing the number of parking spaces and stipulating the quality or location of parking spaces () in the local detailed plans. Thereafter, observations are presented of possible deviations defined in local detailed plan, including how they have affected the overall solution. Finally, observations of how precisely the car parking have been solved are presented in the site plans of the building permits ().

Figure 8. Percentage of information in the context of car parking in site plans that come up with building permits related to study areas.

4.1. The area of new construction

Of the 19 local detailed plans in the study area, 63 % included provisions related to car parking. Of these, 77 % included provisions related to determination of the number of parking spaces. The remaining 33 % stipulated only qualitative features or placements of the car parking. The local detailed plans that did not include provisions concerning car parking included only public areas, e.g. streets or parks, or were accepted when the Planning Act (Citation1931) was in force.

There were 15 provisions focusing on defining the number of parking spaces. Of these, 53 % appeared to have characteristics of robustness and 80 % characteristics of adaptability. The characteristics of the provisions used to determine the number of parking spaces provided can be defined into four types: robustness, robustness with adaptability, adaptability with robustness and adaptability (). The provisions stipulated in the most recently approved local detailed plans comprised robustness with some adaptability

Figure 9. Breakdown of resilience appearance into form characteristics and type characteristics in the area on new construction.

There were 17 provisions in connection with defining quality or location of the parking spaces. In 76 % of these provisions there appear characteristics of robustness, 41 % show characteristics of adaptability and 29 % show characteristics of transformability. The more detailed variation of provisions in terms of the definitions of the resilience characteristics were wider than in terms of number of parking spaces, and there are 7 different types of characteristics: robustness, robustness and transformability, robustness and transformability with adaptability, adaptability with robustness, adaptability, adaptability and transformability, and adaptability and transformability with robustness.

No deviations had been applied from the local detailed plans related to this study area. However, this may indicate more about the lack of development in the area than that the urban planning of the area would have been able to respond to all possible changes and further development of the area.

The data consisted of 41 building permits related to this study area, of which 32 % were in connection with new buildings and the rest were related to repair or extending the existing buildings. The calculation of the number of parking spaces was presented in 75 % of site plans as was the location. Thus, only 41 % of site plans presented the surface of the car parking areas.

4.2. The area of infill development

Only 56 % of the 43 total local detailed plans in the study area included provisions related to car parking, and 87 % of these included provisions related to providing the number of parking spaces. The development of the area with local detailed plans began during a period when the Plannign Act (Citation1931) was in force, and thus the earliest local detailed plans did not include any provisioning for car parking.

There were 37 provisions focusing on defining the number of parking spaces, with 78 % of these appearing to have characteristics of robustness, 62 % characteristics of adaptability, and 5 % characteristics of transformability. The more detailed variation in the characteristics of the provisions used to determine the number of parking spaces provided in local detailed plan can be defined into four types: robustness, adaptability with robustness, adaptability and robustness and transformability with adaptability.

There were 68 provisions in connection with defining the quality or location of parking spaces. Of these, 82 % appeared to have characteristics of robustness, 66 % characteristics of adaptability, and 57 % characteristics of transformability. Here also the more detailed variation of provisions in terms of the definitions of the resilience characteristics was wider than in terms of number of parking spaces and included 7 different types of characteristics: robustness, robustness and transformability, robustness and transformability with adaptability, adaptability, adaptability and transformability, adaptability and transformability with robustness and transformability with adaptability and robustness.

In total, six deviations were accepted for this study area. Four deviations were in connection with crossing the permitted gross floor area. The other two deviated from the footprint of the building area stipulated in the local detailed plan. Finally, in one case, the deviation affected the number of parking space.

The data consisted of 288 building permits related to the study area. Only 14 % were in connection with the new building, and 86 % were related to repairing or extending the existing buildings. The calculation of the number of parking spaces is in 64 % of site plans, and the location of parking spaces is in 76 % of site plans. Hence, only 41 % site plans of the building permits presented the surface of the car parking areas.

4.3. The area of sudden change

Of the 26 local detailed plans in this study area, 85 % included provisions related to car parking, and over 95 % of these included provisions that were related to providing the number of parking spaces. The development of the area began in the 1970s when the Building Act (Citation1958) was in force. Thus, only the local detailed plans that did not include provisions regarding the number of parking spaces were the local detailed plans which included only public areas.

There were 50 provisions focused on defining the number of parking spaces. Of these, 78 % included characteristics of adaptability, 54 % contained characteristics of robustness and 18 % contained characteristics of transformability. The more detailed variation in the characteristic of the provisions used to determine the number of parking spaces provided in local detailed plan was largest in this study area and included all types of characteristics defined earlier: robustness, robustness with adaptability, robustness and adaptability, robustness and transformability with adaptability, adaptability with robustness, adaptability, adaptability and transformability, and adaptability and transformability with robustness.

There were 74 provisions in connection with defining the quality or location of the parking spaces, and 62 % of these provisions appeared to have characteristics of robustness, 86 % characteristics of adaptability, and 68 % characteristics of transformability. The more detailed variation of provisions in terms of the definitions of the resilience characteristics was smaller than in terms of number of parking spaces and included only 6 different types of characteristics: robustness, robustness and transformability, robustness and transformability with adaptability, adaptability, adaptability and transformability, and adaptability and transformability with robustness.

A total of 11 deviations were accepted for the study area. In general, as in 63 % of cases, the reason for deviation was crossing the permitted gross floor area in connection with extension or new building. In 45 % of cases, the deviation affected the number of parking spaces. In 18 % of cases, the deviation was needed for the permitted number of parking spaces.

The data consisted of 156 building permits related to the study area, and 33 % of the building permits were for new buildings, while the others were related to repairing or extending existing buildings. The calculation of the number of parking spaces is in 62 % of site plans, and the location of parking spaces is in 73 % of site plans. Thus, only 39 % of site plans presented the surface of the car parking areas.

5. Discussion

The results highlight the variation of the characteristics of resilience, which reflects the different study areas, as the results of this study clearly pointed out. The differences and the variation in characteristics of resilience were also reflected in the definition of the number of parking spaces and the quality features or location of the car parking. The study also shows the ability to internalize changes of each study area (). The ability may vary temporally and locally.

Table 4. An overview of the development stage identified in the study areas

The findings of this study point out that when looking at the provisions stipulated in local detailed plans, it is worth noting the increasing amount of provisions stipulating parking spaces. However, in addition to that, in the reports of the latest local detailed plans, there was increasing attention drawn to surveys of car parking arrangements of the area. Thus, it seems obvious that it reflected the development of the Act steering the land use generally and in the context of car parking. It also shows the need to pay more attention to how to manage car parking within the condensed urban structure.

The reasons behind the results could be partly explained by the ambiguity and complexity related to car parking. As described early in this paper, car parking affects society in many ways, and thus, besides its functional spatial dimension, it has a strong political meaning. On the other hand, as this study points out, the present local detailed plan consists of a set of different local detailed plans drawn up with different times and objectives under the validity of different Acts. There has also been a huge change in mobility habits and urbanisation during the decades, with a significant impact on competition for free space in the urban structure, especially at the properties and in streets and other areas. All these factors have contributed to the current situation where car parking seems a cumbersome and unclear issue and thus precludes developing cities in a sustainable way in the context of car parking. Thus, parking policy has become an essential part of urban and transport planning.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents characteristics for the definition of resilience that appeared in provisions stipulated in local detailed plans in the context of car parking at three study areas in the City of Oulu. Three main results emerged. Firstly, it was seen that characteristics of provisions in the context of car parking in study areas vary in terms of quality and quantitative characteristics. Another result worth noting is that there were only little deviation decisions concerning the provisions related to parking spaces. Thirdly, the number of parking spaces to be carried out in the construction phase could not be verified from building permits in all cases due to the lack of documents. Moreover, the information obtained from building permits often turns out to be incomplete or outdated, especially in the context of car parking.

As a conclusion of the results, it is worthily the notion that when focusing only on the local detailed plans and later on granted building permits, it is impossible to know how many parking spaces there are in the study areas. Moreover, although the car parking might be managed by other agreements, the information is also fragmented, and the overall understanding is lacking. It is obvious that the lack of such critical information can cause significant problems when developing the urban structure to be more resilient. At the same time, due to urbanisation and climate change, impervious surfaces and stormwaters are increasing and thus have a critical impact on urban flood management. This does not allow urban planners to develop the urban environment in a sustainable way or to react to unexpected changes in urban structure or in mobility habits. Thus, it would be necessary to find new ways to increase resilience in urban planning in the context of car parking.

Since this study is focusing the content analysis of the planning documents, primarily the local detailed plans, the reliability of classifying the characteristics is based on the knowledge of the content and the structure of local detailed plans received through the practical planning experience and the iteration rounds conducted during the study. However, it should be noted that the size of the study areas varies, which may affect the appearance of variation in characteristics. Therefore, further studies on the matter, hopefully also with various sizes and located study areas, are needed. As the provisions related to parking spaces stipulated in the local detailed plan were the main focus target here, it would be worth comparing these findings with the views of the stormwater measurements and the mobility habits surveys to better understand the interaction of provisioning, and thus find new ways to strengthen the resilience in urban planning. These studies would allow us to internalize new approaches when discussing strengthening resilience in urban planning.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the city of Oulu for the help in data collection for research. This paper is part of the research conducted in the IPaWa project, which is a three-year research project realized between years 2019 and 2022 in the Oulu School of Architecture, University of Oulu. The project is funded by European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the City of Oulu and Oulu-based construction companies Rakennusteho Group and Lapti Group.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Building Act, 370/1958. 1958. Retrieved August 6, 2020, from https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/1958/19580370

- Building Decree, 270/1959 (1959). Retrieved August 11, 2020, from https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/1959/19590266

- Davoudi, S., Shaw, K., Haider, L. J., Quinlan, A. E., Peterson, G. D., Wilkinson, C., Fünfgeld, H., McEvoy, D., Porter, L., & Davoudi, S. (2012). Resilience: A bridging concept or a dead end? Planning Theory & Practice, 1(2), 299–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677124

- Davoudi, S., Brooks, E., & Mehmood, A. (2013). Evolutionary resilience and strategies for climate adaptation. Planning Practice & Research, 28(3), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2013.787695

- de Jong, T. M., & Duin, L. V. (2002). Design research. In T. M. de Jong & D. J. M. V. D. Voordt (Eds.), Ways to study and research: Urban, architectural, and technical design (pp. 89–94). Delft: DUP Science.

- de Jong, T. M., & Engel, H. (2002). Typological research. In T. M. de Jong & D. J. M. V. D. Voordt (Eds.), Ways to study and research: Urban, architectural, and technical design (pp. 103–106). Delft: DUP Science.

- Decree of the Ministry of the Environment on plans and reports concerning construction, 216/2015 (2015). Retrieved January 13, 2022, from https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/2015/20150216, Unofficial English translation https://www.ym.fi/download/noname/%7B5FB0E1EB-E75C-436C-9860-A27F37527EC8%7D/124804

- Eckart, K., McPhee, Z., & Bolisetti, T. (2017). Performance and implementation of low impact development – A review. Science of the Total Environment, 607-608, 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.254

- Folke, C., Carpenter, S. R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, T., & Rockström, J. (2010). Resilience thinking: integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecology and Society, 15(4), 20. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art20/

- Haapanala, A., Laine, R., Lunden, T., Pitkäranta, H., Raatikainen, E., Saarinen, T., R-L, S., & Sippola-Alho, T. (2003). Asemakaavamerkinnät ja -määräykset. Maankäyttö- ja rakennuslaki 2000, opas 12. Ympäristöministeriö. Retrieved November 26, 2020, from https://www.ym.fi/download/noname/%7B645FD511-B2FB-462E-A41F-9659F45C266C%7D/32123

- Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

- Holling, C. S. (1996). Engineering resilience versus ecological resilience. In P. C. Schulze (Ed.), Engineering within ecological constraint (pp. 31–43). National Academy Press.

- Jalkanen, R., Kajaste, T., Kauppinen, T., Pakkala, P., & Rosengren, C. (2017). Kaavoituksen kehykset. In Kaupunkisuunnittelu ja asuminen (pp. 66–87). Helsinki: Rakennustieto Oy. Finnish Meteorological Institute.

- Jylhä, R., Ruosteenoja, K., Räisänen, J., Venäläinen, A., Tuomenvirta, H., Ruokolainen, L., Saku, S., & Seitola, T. (2009). Arvioita Suomen muuttuvasta ilmastosta sopeutumistutkimuksia varten. Ilmatieteenlaitos. Rakennustieto Oy.Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/15711/2009nro4.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Kaikkonen, H. (2012). Autopaikoitus- ja pysäköintiratkaisut kunnissa. Kuntaliitto. Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://www.kuntaliitto.fi/julkaisut/2012/1486-autopaikoitus-ja-pysakointiratkaisut-kunnissa

- Kuntaliitto (2012). Hulevesiopas. Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://www.kuntaliitto.fi/julkaisut/2012/1481-hulevesiopas

- Land Use and Building Act 132/1999 (1999). Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://www.ym.fi/download/noname/%7B0AA8EC52-5A9B-4480-81DF-E6B7FB7722C1%7D/58015, Unofficial English translation http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/1999/en19990132.pdf

- Land Use and Building Decree, 895/1999 (1999). Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://www.ym.fi/download/noname/%7BF9FE33AB-677A-4ADE-9329-9A257DFEF530%7D/58016, Unofficial English translation https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/1999/en19990895.pdf

- Museovirasto (2009). Valtakunnallisesti merkittävät rakennetut kulttuuriympäristöt RKY. Karjasillan jälleenrakennuskauden asuinalue. Museovirasto. Retrieved August 14, 2020, from http://www.rky.fi/read/asp/r_kohde_det.aspx?KOHDE_ID=2092

- Nykänen, V., Lahti, P., Knuuti, A., Hasu, E., Staffans, A., Kurvinen, A., Niemi, O., & Virta, J. (2013). Asuntoyhtiöiden uudistava korjaustoiminta ja lisärakentaminen. VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland. VTT Technology No. 97. Retrieved August 14, 2020, from https://publications.vtt.fi/pdf/technology/2013/T97.pdf

- Oulun kaupunki (2018a). Pysäköintinormit. Sito Wise. Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://www.oukapalvelut.fi/tekninen/Suunnitelmat/Nayta_Liite.asp?ID=6655&Liite=Pys%E4k%F6intinormit_OuKa_RAPO.pdf

- Oulun kaupunki (2018b). Kemintien kaavarunko Serum arkkitehdit Oy. Retrieved August 13, 2020, from https://www.ouka.fi/documents/12610409/17906706/Kemintien_kaavarunko.pdf/3c311fbf-dac2-438d-90e8-be8dd1599703

- Oulun kaupunki (2019). Linnanmaan ja Kaijonharjun kaavarunko. Sito Wise. Retrieved August 14, 2020, from https://www.ouka.fi/documents/64220/1932998/564-2360_kaavarunkoraportti_P%C3%84IVITETTY_19-10-10_Optimized.pdf/5d554039-b34b-47d0-801d-26913e0079f9

- Planning Act, 145/1931 (1931). Retrieved August 6, 2020, from https://www.edilex.fi/he/fi19300046II.pdf

- RAKLI (2015). Selvitys kaavamääräysten kustannusvaikutuksista. Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://www.rakli.fi/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/kaavamaaraysten_kustannusvaikutukset_raportti_nettires.pdf

- Rantanen, A., & Joutsiniemi, A. (2016). Muutoksen epistemologia ja resilientit tilalliset strategiat: Maankäytön ja suunnittelun mukautumis- ja muuntautumiskykyä tarkastelemassa. Terra: Maantieteellinen Aikakauskirja, 128(4), 203–213. http://elektra.helsinki.fi/se/t/0040-3741/128/4/muutokse.pdf

- Real Estate Register Act, 392/1985 (1985) . Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/1985/19850392, Unofficial English translation https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/1985/en19850392_20020454.pdf

- Rehunen, A., Ristimäki, M., Strandell, A., Tiitu, M., & Helminen, V. (2018). Katsaus Katsaus yhdyskuntarakenteen kehitykseen Suomessa 1990-2016, Suomen ympäristökeskus (SYKE). Retrieved July 6, 2020, from https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/236327/SYKEra_13_2018.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Walker, B., Holling, C. S., Carpenter, S. R., & Kinzig, A. (2004). Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2):5. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-00650-090205

- Wardekker, J. A., de Jong, A. J. M., J. P, V. D. S., & van der Sluijs, J. P. (2010). Operationalising a resilience approach to adapting an urban delta to uncertain climate changes. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 77(6), 987–998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2009.11.005

- Wied, M., Oehmen, J., & Welo, T. (2019). Conceptualising resilience in engineering systems: An analysis of the literature. Systems Engineering, 23(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/sys.21491