ABSTRACT

Cross-sectoral collaboration between actors is essential when planning station districts for transit-oriented development. However, power relations and the resulting dominance of selected actors complicate collaborative processes and the necessary integration between transportation and urban planning. Despite the previous problematization of power in planning, dedicated research is lacking on station districts. This article aims to tackle this literature gap through qualitative case studies of two station districts in Switzerland. The findings suggest that municipalities and public transport providers use power resources to assume institutional roles outside their traditional planning domains, partly as a tactical response to initiatives that they contest. For planning practice, the article proposes that process organizers grasp actors’ power potentials early and, if mobilized, integrate them in favor of broadly supported station district development.

Introduction

Collaboration is vital in harnessing station districts’ potential for transit-oriented development (Bertolini et al., Citation2012). Numerous actors (organizations and their representatives) become involved (e.g. public authorities, public transport providers, and property owners) due to station districts’ expanded development scope. This scope may encompass projects in transit stations, their access points, and surrounding neighborhoods (Brons et al., Citation2009; Van Acker & Triggianese, Citation2020). Furthermore, station district planning requests the integration of different sectors (e.g. urban planning, public transport, and real estate) whose actors typically operate at various planning scales (e.g. local, regional, and national scales; Reusser et al., Citation2008; Toro López et al., Citation2021). Consequently, planning process organizers should prioritize coordination and synchronization among actors (and their respective projects within the scope) to facilitate consistent and broadly supported station district development (Bertolini et al., Citation2012; Rongen et al., Citation2022).

However, overarching process governance typically is nonexistent in station district planning, and shared collaboration trajectories are not well-framed among the various sectors, organizations, and persons involved (Hickman et al., Citation2021; Zemp et al., Citation2011b). Instead, sectoral and local planning cultures may enhance and constrain actors’ power resources differently during collaborations, including sectoral/local planning artifacts, processes, and tools with their socially shared, underlying meanings (Knieling & Othengrafen, Citation2015; Reimer, Citation2013). Previous research frequently has distinguished between structural and behavioral power resources (e.g. Chatterjee & Kundu, Citation2020; Fritz & Binder, Citation2020; Pfetsch & Landau, Citation2000; Wolff, Citation2020). Structural power denotes given power resources based on intellectual, material, and financial assets, as well as privileging laws and regulations (i.e. structures; Wolff, Citation2020). However, actors deploy behavioral power using negotiation and leadership skills, procedural and expert knowledge, and alliance-forming capacities (i.e. behaviors) during collaborations (Pfetsch & Landau, Citation2000). Understanding power relations in planning is crucial for organizers, as power tends to dominate collective negotiations and rational decision-making unilaterally, rather than symmetrically (Flyvbjerg, Citation1998; Frimpong Boamah, Citation2022). Consequently, abuse of power may hinder broad-based alignment among actors and lead to suboptimal planning outcomes (Wolff, Citation2020).

Research on power in station district planning is lacking, and this gap is problematic because power relations might elicit unpredictable process dynamics for organizers, complicating the communication and synchronization needed among persons, organizations, and sectors. Consequently, planning outcomes primarily could consider the interests of those using power resources, which do not necessarily view station districts as public goods and harness their potential for transit-oriented development. Therefore, this article inductively examines power resources in station district planning and aims to clarify the corresponding relations and actors’ responses when facing power during collaborations. To this end, the article aims to answer the following research questions (RQs):

RQ-1: Which power resources are characteristic of station district planning?

RQ-2: How do actors respond when they face power in station district planning?

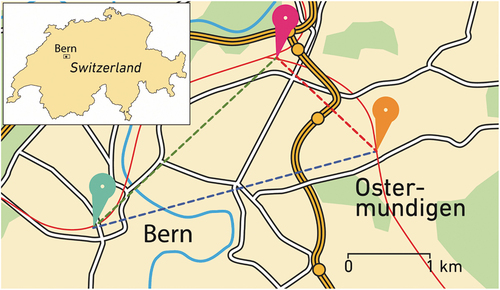

I conducted a qualitative analysis for this article, comprising case studies of the station districts in Bern Wankdorf and Ostermundigen, Switzerland. Both station districts lie in the Bern agglomeration and are undergoing substantial transformations due to land-use intensifications and public transport infrastructure renewals that various actors manage. Despite its case-specific analysis, this article provides planners facing analogous collaborative processes with insights into (1) how individual actors might mobilize power resources and (2) how organizers can stay abreast of power relations and still enhance coordination and guidance. The article is structured as follows. First, I give an overview of the relevant theory to substantiate and clarify further the study’s RQs. Second, I present the methods used in this research. Third, I introduce the case studies of Bern Wankdorf and Ostermundigen and describe the results from the analyses. Finally, I discuss the findings and limitations and conclude the article with implications for planning practice.

Theoretical background

Multi-actor collaboration at the nexus of urban and transportation planning

Station districts represent the nexus of spatial and transportation planning in the urban fabric and other compact spaces (Toro López et al., Citation2021; Zemp et al., Citation2011a). As gateways to regional or long-distance transit networks, they can integrate local settlement structures with public transport services and infrastructures at the regional and national scales (Reusser et al., Citation2008; Zemp et al., Citation2011b). The concept of transit-oriented development expands on this potential by suggesting that planners intensify urban and settlement development in territories where people can access mass transit easily (Calthorpe, Citation1993). For station districts, land-use intensification typically focuses on a catchment area with a perimeter radius of approximately 400 to 800 meters around transit stations (Guerra et al., Citation2012). Within this development scope, urban and transportation planners jointly foster public spaces and mixed-use attraction centers, e.g. areas with high employment and housing concentrations, with improved spatial connectivity to multimodal transport, including mass transit and inner-city transportation modes (Bertolini, Citation1996; Papa & Bertolini, Citation2015).

The alignment of developments within and beyond transportation and urban planning’s sectoral structures complicates station district development (Toro López et al., Citation2021; Zemp et al., Citation2011b). The development scope may encompass multiple projects concerning transit stations and their access points, adjacent neighborhoods, and inner-city transportation infrastructure (Brons et al., Citation2009; Lu et al., Citation2021; Van Acker & Triggianese, Citation2020). Accordingly, organizers might find numerous organizations eligible to participate in collaborative processes with their representatives (Bertolini et al., Citation2012; Hickman et al., Citation2021). With different sectoral backgrounds and local mindsets, these actors work with various frameworks and assign diverse values and assumptions to their planning practice, which can be referred to as sectoral and local planning cultures (Knieling & Othengrafen, Citation2015; Nostikasari & Casey, Citation2020). The resulting cross-sectoral multi-actor collaborations typically are not reflected adequately in current transportation and urban planning policies and practices (Banerjee, Citation2022; Rongen et al., Citation2022). Thus, station district planning may lack effective governance among the numerous actors involved, rendering collaboration more susceptible to unpredictable dynamics exposed by power relations (Reimer, Citation2013; Thomas et al., Citation2018).

Power resources and relations in collaborative processes and planning

Power is a multilayered concept and can be defined as ‘ … persons, assets, materials or capital used to realize a certain goal, including human, mental, monetary, artifactual and natural resources … ’ (Avelino & Rotmans, Citation2011, p. 798). When collaborating, actors’ exchanges and communications depict how they wield power over and with others (Forester, Citation2021; Partzsch, Citation2015). They dominate and wield power over others by causing them to behave in uncharacteristic ways (Partzsch, Citation2017). However, using power with others describes productive collective learning and the behavioral capacities employed to attain shared goals (Allen, Citation1998; Fritz & Binder, Citation2020). In both contexts, power predominantly denotes a relational force – partly rigid, e.g. material-based power, and partly fluid, e.g. evolving during collaborations (Eskafi et al., Citation2019; Fritz & Meinherz, Citation2020; Reimer, Citation2013). Thus, actors’ power may vary across collaborative processes based on the respective constellations of organizations and their representatives (Pfetsch & Landau, Citation2000; Wolff, Citation2020).

Power in planning can be classified under structural and behavioral resources (Wolff, Citation2020). The former describes power resources given to actors based on institutional structures – e.g. financial, material, and intellectual assets – as well as laws, regulations, rules, and assignments that endow these actors with legitimacy (Fritz & Binder, Citation2020; Reimer, Citation2013; Wolff, Citation2020). Structural power resources are context-dependent, but precede actual collaborations between actors. They constitute power potentials that selected actors can activate and use when exchanging and communicating with others. However, behavioral power resources denote actors’ tactical options, i.e. active responses in a primary relational setting (provided by institutional structures) during collaborations (Frimpong Boamah, Citation2022; Habeeb, Citation1988). Actors likely respond with tactical behaviors using the following resources when facing power, particularly if institutional structures endow them with poor resource potentials (Pfetsch & Landau, Citation2000; Wolff, Citation2020):

Negotiation skills and knowledge

Coalition-building capacities

Rule and agenda-setting knowledge

Strategies to create package deals and reach compromises and alternatives

Methods

Case study selection

This study used in-depth case analysis based on qualitative empirical research in planning. I conducted case studies of two station districts in Switzerland: Bern Wankdorf and Ostermundigen. This study was part of Co-Creating Mobility Hubs, a transdisciplinary research project (Müller et al., Citation2022). I selected Bern Wankdorf and Ostermundigen because both districts currently are undergoing various area and public transport infrastructure projects and experiencing land-use intensifications, which actors aim to orchestrate and synchronize, rendering them ideal for in-depth case analysis. Located in the agglomeration of Bern, Switzerland’s federal city, Bern Wankdorf and Ostermundigen are part of the regional transit network connecting the midland with Bernese Oberland. Whereas Bern Wankdorf belongs to the City of Bern (with a permanent resident population of approximately 135,000 in 2020) at the municipal scale, Ostermundigen’s station district is affiliated with the Municipality of Ostermundigen (with a permanent resident population of roughly 18,000 in 2020; AUSTA der Stadt Bern, Citation2021; BFS, Citation2022). illustrates the locations of the stations in Bern Wankdorf (magenta pin), Ostermundigen (orange pin), and Bern (mint pin). The red dotted line corresponds to approximately two kilometers, whereas the green and blue dotted lines represent roughly three kilometers of linear distances.

Figure 1. Map with the locations of the stations in Bern Wankdorf, Ostermundigen, and Bern, including the linear distances between these stations (adapted from OpenStreetMap, Citation2022; CC BY-SA 2.0).

Data collection

For both case studies, I collected the data between May 2020 and December 2021 to pursue a research strategy that uses the following data source mix:

A body of documentation to dive into the case study contexts with their (statutory) planning groundwork and current development projects, and to prepare for the interviews, including recruiting initial conversation partners (cf. next point). The collected documents included five mass media reports and 16 public relations and official reporting pieces that public agencies produced, comprising six press releases, five mission statements, four land-use plans, and a parliamentary intervention. I also gathered nine documents comprising actors’ internal correspondence, including five presentations, material from two workshops, a workshop’s minutes, and a memo. The files were received via web research or personal e-mail (within Co-Creating Mobility Hubs). I viewed any document that dealt with a planning process involving one or both station districts studied as cases, and I did not apply any further selection criteria (Scott, Citation1990). Appendix A includes detailed information on the collected documents.

Semi-structured expert interviews to understand power resources and relations inductively, including actors’ responses when facing power. Due to these constructs’ informality and latency, conversations were structured minimally through a few generic open questions from an introductory guide used by Co-Creating Mobility Hubs, which I complemented with spontaneous queries to trace selected narratives (Charmaz, Citation2002; Kvale, Citation1996). I conducted 32 interviews in German, with 16 lasting 60 minutes each (explorative interviews) and 16 lasting 90 minutes each (in-depth interviews). The explorative interviews were conducted when the experts’ roles in the case studies still needed to be clarified. However, I conducted in-depth interviews when I was confident about the interviewees’ significant involvement in one of the station districts, and when they were available for a conversation of that duration. The interviewees represented public authorities (N = 10), local property owners (N = 5), public transport infrastructure providers (N = 9), public transport service providers (N = 7), and a local stakeholder group (N = 1). Based on preliminary document analysis, I identified an initial case-specific set of interviewees relevant to my RQs, encompassing the myriad actors involved in the station districts’ current projects. Oriented toward a snowball sampling strategy, I interviewed persons afterward that previous interviewees explicitly recommended to me or mentioned multiple times during our conversations (Coleman, Citation1958). Appendix B offers more information on the interviewees and the primary interview guide.

Participant observations in the closed settings of three meetings and a workshop in Ostermundigen’s station district to validate and complement preliminary results from the interviews regarding this case. An interviewee invited me to attend this planning workshop and the three preparatory meetings, during which I assumed the role of a nonparticipating observer and had very little interaction with anyone (Adler & Adler, Citation1987). I focused on which power resources became perceptible during these settings (because actors used them) and what responses followed from other participants (Murphy, Citation1980). Appendix C contains the template that I used to establish protocols for my observations. Unfortunately, no comparable observation opportunities were available for the Bern Wankdorf case.

Data analysis

I coded the interview transcripts and observational protocols to analyze the data. The coding approach followed an inductive and qualitative content analysis focusing on themes and narratives signaling power resources (addressing RQ-1) and actors’ responses to exercised power in station district planning (addressing RQ-2; Kohler Riessman, Citation2008; Ryan & Bernard, Citation2003). My coding included written memos, and I used the operationalization provided in to align the primary level of analysis with the conceptual framework of this research (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022; Brooks et al., Citation2015).

Table 1. Qualitative content analysis: Conceptual operationalization and subcodes from the inductive data analysis (adapted from Brooks et al., Citation2015; Meijer & Van Der Krabben, Citation2018).

NVivo software (March 2020 release) was used to conduct the data analysis. To consider the identified themes and narratives’ potential to suggest sequences of events that contribute to causal inferences, I employed process tracing within single case studies. Process tracing helped carve out case-specific cause-and-effect relationships and, thus, a thorough understanding of the case study contexts (Bengtsson & Ruonavaara, Citation2017; Bennett & Checkel, Citation2014).

Results

Bern Wankdorf case study

Case study context

Bern Wankdorf’s station district (see ) is a central public transport junction within the larger Wankdorf perimeter that has been a cantonal focus of development since 1989. While the station district is located within the City of Bern, the Wankdorf perimeter further contains areas of the Municipalities of Ittigen and Ostermundigen, with a permanent resident population of roughly 3,500 in 2015 and a workforce of about 24,000 in 770 workplaces in 2013 (BVD des Kantons Bern, Citation2022). Appendix D lists recent and current planning processes and critical events that specifically have concerned Bern Wankdorf’s station district perimeter, including the involved actors (December 2021).

During the explorative data collection for the Bern Wankdorf case study, one planning process stood out and qualified for analysis within the theoretical framework for this research because it covered the entire station district, not just a single project within the perimeter. This is the first iteration of the novel Entwicklungszielplan (EZP) process between 2019 and 2020, organized by Swiss Federal Railways (SBB). With this process, SBB attempts to push forward the orchestration and synchronization of the station district’s projects that included area developments, motorway and railway infrastructure extensions and renewals, and the redevelopment of the railway station at that time. Therefore, SBB met with selected actors during two workshops in March 2019 to draw up the first EZP version for Bern Wankdorf, which would be a legally nonbinding coordination plan and instrument for station district development (Interviewees 6, 7).

Power resources: First iteration of the Entwicklungszielplan process

The analysis of the first EZP iteration offers evidence of how SBB pressured others under the guise of collective action. While the communicated purpose of the process vouches for horizontal process integration to attain shared goals in station district planning, SBB designed the methodology and format for this first iteration predominantly without consulting actors who then were invited to the workshops as participants (Interviewee 6). Accordingly, participants felt that the process design was imposed on them and primarily met SBB’s requirements and administrative structures (Interviewees 1, 3, 8, 16). These actions were formally legitimate because SBB created and designed the EZP process that neither produces a legal obligation nor claims democratic legitimacy. However, one SBB representative noticed confusion among participants when starting the first workshop (translated from German):

Many participants wondered: What does SBB want with this? They seemed unsettled, perhaps because we had not done this before and suddenly came up with this proposal to take an active role in coordinating this joint planning, which goes beyond our property perimeter (Interviewee 7).

Based on the formal legitimacy and self-assigned task to foster alignment within the station district, SBB wielded power and put other actors in a tight spot. Specifically, the EZP process addressed an item that already had been on the canton and city’s agendas: The integration of developments around mass transit stations to create dense and vibrant districts to make public transport and human-powered mobility more attractive (BVD des Kantons Bern, Citation2019; Interviewees 3, 4; SPA und VP der Stadt Bern, Citation2017). Moreover, considering that the process was the first initiative to gather actors in the station district around a table, invited participants still joined the workshops even if SBB had not involved them in commenting on the format or the methodology. For SBB, increasing public transport attractiveness and pioneering integrated planning were only one side of the coin in choosing Bern Wankdorf’s station district to pilot the EZP process. The station district hosts its current headquarters (within the WankdorfCity area); thus, SBB management specifically views Bern Wankdorf’s railway station as the public law corporation’s calling card (Interviewee 13).

Actors’ responses when faced with power: The City of Bern and the other Entwicklungszielplan participants

SBB’s initiative for integration within the station district in particular took the city by surprise and put specific participants on the spot, considering that at that time (around 2019), they were at a critical project impasse with SBB in the railway station redevelopment due to disagreements regarding cost coverage (Interviewees 1, 2, 10, 13). Although different SBB representatives managed the EZP process, compared with those of the railway station redevelopment, city representatives expressed their irritation over SBB’s alleged two-sided practice of, on one hand, advocating for planning the station district collectively further within the EZP process, while on the other hand, SBB would not follow up on the city’s requirements for railway station redevelopment with financial contributions (Interviewees 1, 2). More fundamentally, the city could not grasp the nontraditional institutional role that SBB played in Bern Wankdorf as organizer of the EZP process and, thus, station district planning, which was the basis on which the public transport infrastructure provider ‘left’ the station, its traditional jurisdiction (Interviewees 3, 7, 11). Moreover, that SBB did not assume a similar role (in cost-covering terms) in the railway station redevelopment project may have intensified this impression on the city’s part, as one representative suggested (translated from German):

Just imagine: SBB invites you to a strategic, conceptual round, and the same organization does not bring its projects in the perimeter to the discussion table, which are advanced and have numerous interfaces with the urban fabric and other development projects (Interviewee 1).

Consequently, the City of Bern became more vocal during the second EZP workshop and openly expressed skepticism toward essential methodological aspects. For instance, representatives questioned the emphasis on qualitative locations for future uses and offerings in the station district, which were viewed as overly abstract, and corresponding quantified space requirements, which were viewed as overly detailed (Interviewees 1, 3). Other issues included the plan’s nonbinding character and the timing for its implementation, which partly was viewed as a fait accompli (Interviewees 2, 3, 26). The city may have used this power resource strategically to strengthen its position during the planning process, but most actors viewed it as a constructive process that created a common understanding among actors (Interviewees 2, 7, 16). After SBB released the first EZP version at the beginning of 2020, the prospect lead for the subsequent annual iterations was extended to the city, resulting in a coordinating partnership between SBB and the City of Bern in Bern Wankdorf (Friedli, Citation2020; Interviewees 6, 14).

While other EZP participants benefitted from the city’s reaction (as it created a shared understanding of the process), a similar response was not evident from Bern-Lötschberg-Simplon Railway (BLS), BERNMOBIL, the Canton of Bern, or Energie Wasser Bern (ewb) (Interviewees 7, 8, 16). Although they partly shared the initial irritation over SBB’s initiative and judgment of imposition, the canton, BERNMOBIL, and BLS participated somewhat free of emotion during the process, assuming they were only marginally affected by the plan’s outcomes (Interviewee 7). However, ewb, a property owner in the station district, used the workshop to point out its space requirements based on future construction projects and its reduced willingness to offer services in favor of other transportation infrastructure in Bern Wankdorf (Interviewee 1).

Ostermundigen case study

Case study context

The station district in Ostermundigen (see ) functions as one of the municipality’s focal points of local spatial development (Interviewee 17). This is a so-called Zentrale Baustelle (ZBS), defined within Ostermundigen’s ongoing total revision of local zone plans (O’mundo, Citation2021). The comprehensive revision of subregional spatial planning was triggered by two significant area developments in the station district: BäreTower in 2011 and Poststrasse Süd in 2014. Private developers mainly pursued both projects, ending a decade during which development in the station district was at a standstill (Interviewee 24). Appendix D outlines the planning processes that have involved the station district since development took off in this perimeter.

The Ostermundigen case analysis focused on the ZBS planning process because it functioned as a conduit through which to coordinate and synchronize multiple ongoing developments in the station district, thereby corresponding to this study’s theoretical frame. During data collection, these initiatives comprised several area developments, as well as tramway and railway infrastructure projects. On one hand, the ZBS framed a test-planning study between nine actors in 2019 for comprehensive area developments within the station district (Interviewee 19). On the other hand, it denoted a venue for coordination between SBB, the Municipality of Ostermundigen, and the tramway infrastructure provider BERNMOBIL, all representing ongoing track infrastructure and station/stop redevelopment projects (Interviewees 23, 29).

Power resources: Zentrale Baustelle coordination frame

The analysis of evidence emphasizes the ZBS frame’s function as a coordination venue for the track infrastructure and station/stop projects. These projects contain far-reaching interdependencies, as there will be one transit station in the district eventually that includes Ostermundigen’s sole railway station and the associated tramway stop. To ensure alignment between these projects, the approval authority – the Federal Office of Transport (FOT) – requested a joint submission of planning documents from the project teams (Interviewees 22, 23, 29). Although the teams mainly operate in the same sector (public transport infrastructure), integrating planning practices was cumbersome and provides evidence of how SBB dominated BERNMOBIL and the municipality. This was because representatives of the tramway infrastructure project were unfamiliar with professional requirements under federal law (according to which SBB operates) (Interviewees 18, 28). One municipal representative described the experience as follows (translated from German):

Railway law at the federal scale is a whole new ballgame. They have many more project requirements: How does it have to be designed? What level of detail and at what stage? But above all, there are other needs. And even though you try to overlay everything, there is an unambiguously hierarchical story behind it (Interviewee 18).

Tramway infrastructure project members felt that a combination of their counterpart’s actions between 2019 and 2020 led to a problematic relationship between the teams facing extended decision-making periods and varying commitments to previous decisions due to the necessary cross-scale alignment. SBB did not take a proactive stance toward BERNMOBIL and the municipality, which typically were informed on short notice about approved change requests in the railway infrastructure project, affecting the joint planning approval process with FOT (Interviewees 22, 23). Furthermore, SBB did not provide project managers with the resources needed to manage the tramway infrastructure project as a stakeholder critical to successful station district development. Accordingly, an active professional knowledge transfer to BERNMOBIL and the municipality was nonexistent, which would have helped with understanding SBB’s ‘infrastructure world’ (Interviewees 28, 29). These railway infrastructure project members’ practices may signal activated power resources through adherence to the status quo project lifecycle, for whose management they primarily were supplied with resources. Thus, SBB representatives used power to shield the railway infrastructure project’s basic progress, which the tramway infrastructure project still viewed as stalling.

Actors’ responses when faced with power: BERNMOBIL and the Municipality of Ostermundigen

The tramway infrastructure project reacted in two ways in response to its power relations with the other project. First, it asked FOT in 2019 to approve plans for two separate processes: one for the railway and another for the tramway developments in the station district. FOT rejected the request because it viewed the projects’ interdependencies as overly strong and was cautious about creating constructional prejudice (Interviewees 22, 23). BERNMOBIL representatives then attempted to improve their relationship with SBB within their projects’ existing institutional structures, and they succeeded in 2021. Specifically, they tried to elicit empathy from railway infrastructure project members, demonstrating that they understood their issues and emphasizing that ‘they are all in the same boat’ (Interviewees 22, 28, 29). The path to this newfound alliance displays how the tramway infrastructure project worked actively toward a relational setting in which one actor’s dominance yields collective learning and action. One tramway project member described this progress as follows (translated from German):

Despite changes in the railway infrastructure project management, we noticed that our needs had been increasingly considered and that it is coordinating both our needs and not always us initiating everything, and that mutual understanding is shown going forward (Interviewee 22).

The municipality’s institutional role within this relational setting was less reactive than that of BERNMOBIL for two reasons. First, coordinating the station district’s infrastructure projects was only one among several process settings within the ZBS frame that, in turn, constituted one among three developmental perimeters of the total revision of local spatial planning (Interviewees 17, 18). Second, for a municipality the size of Ostermundigen, in trying to lead this revision, the resources and professionalization available at the local scale are lacking (Interviewees 19, 22, 23). Consequently, the Municipality of Ostermundigen did not respond to the power it may have faced within the ZBS coordination frame with any tactical behavior.

Discussion

Power resources characteristic of station district planning

Responding to RQ-1, the findings from the case studies suggest that actors in station district planning might wield power by assigning themselves the task of planning integration, exploiting procedural and expert knowledge, hoarding specialist professional knowledge, and implementing alliance-building strategies.

First, the Bern Wankdorf case study exemplifies how actors who decide to position themselves as organizers in station district planning might opt to dominate the corresponding process designs, possibly because this role is typically not formally defined and, thus, not bound further to legally binding planning frameworks and liabilities (Hickman et al., Citation2021; Toro López et al., Citation2021). Consequently, an intervention to bring together the relevant actors is essentially legitimate as long as it does not trespass on the statutory planning authorities’ sovereign jurisdiction. However, such an initiative still may be viewed as an imposition or domination based on structural power over other actors, as demonstrated by actors’ mixed feelings regarding SBB’s nontraditional institutional role during the first EZP iteration (Partzsch, Citation2015).

Second, expert and procedural knowledge at the core of power resources is perceptible in Bern Wankdorf, laying the basis for the City of Bern to express critical judgment toward essential aspects of the EZP process, which might be viewed as a tactically motivated practice (cf. next section). Previous research has found similar behavioral power wielded in cases in which citizen groups involved in local spatial planning drew on procedural knowledge to share legitimacy concerns for collaborative processes with municipalities (Meijer & Van Der Krabben, Citation2018; Wolff, Citation2020). However, in station district planning, municipalities might express concerns themselves and question the legitimacy of public transport infrastructure providers’ cross-sectoral initiatives that soften traditional jurisdictions.

Third, the Ostermundigen case study provides evidence of how specialized professional knowledge might be deployed as a structural power resource when actors decide not to share that knowledge with others who otherwise could have benefitted from more inclusive collaboration (Frimpong Boamah, Citation2022; Habeeb, Citation1988). Suggesting that this decision by SBB’s railway infrastructure project mostly was due to resource constraints tends to align with earlier planning studies emphasizing how institutional structures might constitute barriers to knowledge transfer (Nostikasari & Casey, Citation2020; Taufiq et al., Citation2022). Due to these structures, certain actors may view a particular piece of knowledge as self-evident and, thus, place it in a ‘black-box’, even though sharing it would be critical to sustaining mutual exchange and communication with others (Nostikasari & Casey, Citation2020, p. 686).

Fourth, my findings concerning coordination activities within the ZBS frame in Ostermundigen shed light on how encumbered collaboration conditions might induce actors to seek alliances based on collective learning and action (cf. next section) and, thus, increasingly seek power with others (Allen, Citation1998; Fritz & Binder, Citation2020). In this regard, national and regional planning studies have found that actors might employ alliance-building capacities in spatial planning for multiple reasons, including attempts to improve social relationships (Reimer, Citation2013). However, the reasons also may involve aligning conditions and exchanging favors between approving statutory authorities and property developers, which do not apply to the motivation behind the behavioral power resources deployed by BERNMOBIL and SBB (Pfetsch & Landau, Citation2000; Sanli & Townshend, Citation2018).

Actors’ responses when facing power in station district planning

Concerning RQ-2, the study results imply that actors might respond to exercised power in station district planning by scrutinizing novel processes’ methodological soundness and informal legitimacy, improving social relationships with power-wielding actors, and not reacting specifically. The findings addressing RQ-1 also partly provide answers to RQ-2, as some reactions to exercised power again might be based on using power resources.

First, city representatives’ reaction to SBB’s positioning outside its traditional jurisdiction in the Bern Wankdorf case study points to an interesting characteristic of station district planning: Municipalities might face difficulties finding their appropriate institutional roles. On one hand, they may want to be and should be involved actively as local statutory planning authorities (Valler & Phelps, Citation2018). On the other hand, municipalities tend to be highly dependent on public transport providers at the cantonal and federal scales to integrate local settlement structures with regional and long-distance transit networks toward transit-oriented development (Reusser et al., Citation2008; Zemp et al., Citation2011b). Previous research has found similar dilemmas at the root of skeptical views of novel initiatives at the regional scale, which recently have received greater attention in strategic spatial planning (e.g. Meijer & Van Der Krabben, Citation2018; Purkarthofer, Humer et al., Citation2021; Purkarthofer, Sielker et al., Citation2021; Zimmermann & Momm, Citation2022). In responding to the potential loss of statutory competence due to formal regional planning empowerment, both actors at traditionally subordinate and superordinate scales may question the methodologies and formats used in these frameworks and their practical legitimacy (Reimer, Citation2013; Sanli & Townshend, Citation2018). However, these findings are not in a position to clarify why actors might take tactical action when facing power in station district planning, in which no legal empowerment has occurred, and statutory competencies have not been at stake.

Second, BERNMOBIL representatives’ tactical response to exercised power by SBB in the Ostermundigen station district reinforces how integrating public transport infrastructure planning across multiple planning scales might intensify the need for mutual empathy and understanding (Nostikasari & Casey, Citation2020). In this regard, improving social relationships based on collective learning and action might lay the groundwork for change, particularly when alternations in planning frameworks are less promising (or, as in the case of Ostermundigen, rejected by the relevant statutory planning authorities). Previous planning studies have provided partial evidence of actors’ agency in using power resources to converge with others (Meijer & Van Der Krabben, Citation2018; Wolff, Citation2020). However, power-wielding actors might reciprocate with suggested coalitions to signal convergence only on the surface. They may draw on tactical behaviors to preserve, rather than alter, power relations and selectively support change requests in novel planning frameworks, albeit without sustained convergence in underlying values and assumptions (Reimer, Citation2013; Sanli & Townshend, Citation2018). These findings may carry implications for the next EZP iteration in Bern Wankdorf regarding the question of how the partnership between SBB and the City of Bern will transform from the acquired shared understanding into actual shared leadership, or merely remain a rule change ‘on paper’.

Third, the case study results found that actors might not respond specifically to exercised power in station district planning. This absence of a reaction due to the municipality’s insufficient resources within the ZBS frame in Ostermundigen again raises the question of which institutional role municipalities should or can take. Specifically, the Municipality of Ostermundigen may have more difficulty facing regional and national transport providers on an equal footing than the City of Bern. Switzerland’s federal city employs a thoroughly professionalized administration with a clear political brief, in which more attractive public transport and human-powered mobility are high on the agenda. In this respect, earlier research on local statutory planning authorities’ role in sustainable mobility suggests differentiating leaders from enablers (Wallsten et al., Citation2021). The Municipality of Ostermundigen might view its role mainly as enabling other public law and private actors to complete their projects and keep the threads together, including providing networking platforms and appropriate incentive schemes.

Limitations and suggestions for further research

This article may continue the hitherto-short examination of power in station district planning for transit-oriented development, but I acknowledge that my analysis is limited to case-specific pathways and how urban and transportation planning are conducted in Switzerland. For example, Swiss public transport infrastructure planning increasingly occurs at the federal scale, while cantons and municipalities play more formative and autonomous roles in spatial and settlement planning (ARE, Citation2021; Schenkel & Plüss, Citation2021). Accordingly, more case studies are needed to improve our current understanding of the collaborative integration of space and settlement with transit, particularly for station districts.

Furthermore, the selected research methods and periods limited the ability to capture actors’ power resources in the article’s case studies and how power relations may change over time. While the results from the analysis may apply to the selected cases, they cannot be generalized due to the sample size and the qualitative, explorative empirical approach. However, the pathways and outcomes that the case-specific analyses elicited might be transferable to planning problems in other countries within similar cultural contexts, embracing analogous tenets in urban planning and its alignment with mass transit (Przeworski & Teune, Citation1970).

Theoretically, the presented findings mainly focus on actors wielding power over and with others (Partzsch, Citation2015). This focus was a conceptual simplification that neglected other power theories, e.g. power to, which might be a promising direction for further research to examine why actors wield power and the specific goals they pursue (Haugaard, Citation2012). Furthermore, differentiating behavioral from structural power resources presents another simplification that ignores poor selectivity and should be expanded further. Finally, the article’s results point out how station district planning might become contested because actors leave their traditional jurisdictions, creating novel power relations. In this respect, future research should clarify institutional interactions between local statutory planning authorities and public transport providers at superordinate scales. Both play critical roles in transit-oriented development, which needs to be understood more thoroughly to facilitate cross-sectoral collaboration.

Conclusion

This article addressed the research gap in station district planning power and attempted to characterize the power resources used during cross-sectoral collaboration and how actors react when facing power. Beyond these characterizations, the study may contribute to broader research discourses on actors’ willingness and readiness to collaborate and, thus, align planning for transit-oriented development. In this context, my findings demonstrate how local statutory planning authorities and public transport infrastructure providers may interact while leaving usual jurisdictions and assuming nontraditional institutional roles in each other’s planning domains. From the perspective of power resources and relations, the in-depth case analyses shed light on potential structures and behaviors, as well as the underlying assumptions and values concerning why actors jeopardize integration and, thus, broadly supported planning outcomes.

This article concludes with implications for practice, addressing process organizers in station district planning with a direction of impact to achieve the necessary coordination and guidance. Understanding process dynamics induced by power requests the capture of corresponding resources and relations at the beginning of a collaboration and again after the first round of substantial negotiations and decision-making. I assert that it is crucial first to grasp the primary relational settings that various actors encounter and shape with selected power potentials that institutional structures provide. It may help organizers imagine which resources might be mobilized once collaboration begins, or soon afterward. To examine these initial expectations, organizers then should target a temporal reference point, e.g. after completing the first ‘hard’ negotiations. This would help refine actors’ institutional roles that they likely assume by wielding power during collaborations. Moreover, organizers would be able to capture tactical behaviors that some actors might have activated in response to exercised power, including more person-centered resources. Eventually, organizers should attempt to integrate actors’ power potentials and already activated resources in favor of collective action and station districts’ development as public goods.

Ethics declarations

The ETH Zurich Ethics Commission (Proposal 2020-N-93) reviewed and approved this research, and the study’s participants provided appropriate informed consent.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (186.9 KB)Acknowledgments

I am indebted to the interviewees and the Co-Creating Mobility Hubs project team for sharing their time, experience, and knowledge. I also wish to warmly thank the reviewers, particularly Prof. Dr. Michael Stauffacher and Dr. Bianca Vienni Baptista, for their constructive suggestions and invaluable feedback. Finally, I want to thank Sandro Bösch for his pivotal help with the graphical figures and Swiss Federal Railways and ETH Zurich for supporting this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, this study’s participants did not agree to allow their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data were not available.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adler, P. A., & Adler, P. (1987). Membership roles in field research. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984973

- Allen, A. (1998). Rethinking Power. Hypatia, 13(1), 21–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1998.tb01350.x

- ARE. (2021). Schweizerische Verkehrsperspektiven. Schlussbericht https://www.are.admin.ch/dam/are/de/dokumente/verkehr/publikationen/verkehrsperspektiven-schlussbericht.pdf.download.pdf/verkehrsperspektiven-schlussbericht.pdf

- AUSTA der Stadt Bern. (2021). Agglomeration Bern https://www.bern.ch/themen/stadt-recht-und-politik/bern-in-zahlen/katost/00gruube/downloads/g-00-00-010.pdf/download

- Avelino, F., & Rotmans, J. (2011). A dynamic conceptualization of power for sustainability research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 19(8), 796–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.11.012

- Banerjee, I. (2022). Railopolis: City Within a City. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2022.2074523

- Bengtsson, B., & Ruonavaara, H. (2017). Comparative process tracing: Making historical comparison structured and focused. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 47(1), 44–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0048393116658549

- Bennett, A., & Checkel, J. T. (2014). Process tracing. From philosophical roots to best practices. In A. Bennett & J. T. Checkel (Eds.), Process tracing. From metaphor to analytic tool (pp. 3–38). Cambridge University. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139858472

- Bertolini, L. (1996). Nodes and places: Complexities of railway station redevelopment. European Planning Studies, 4(3), 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654319608720349

- Bertolini, L., Curtis, C., & Renne, J. L. (2012). Station area projects in Europe and beyond: Towards transit oriented development? Built Environment, 38(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.38.1.31

- BFS. (2022). Statistischer Atlas der Schweiz. Ständige Wohnbevölkerung, 2020 https://www.atlas.bfs.admin.ch/maps/13/de/16214_72_71_70/25203.html

- Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196

- Brons, M., Givoni, M., & Rietveld, P. (2009). Access to railway stations and its potential in increasing rail use. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 43(2), 136–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2008.08.002

- Brooks, J., McCluskey, S., Turley, E., & King, N. (2015). The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

- BVD des Kantons Bern. (2019). Richtplan ESP Wankdorf (Stand Vorprüfung) https://www.espwankdorf.bvd.be.ch/content/dam/espwankdorf_bvd/dokumente/de/kommunikation/1613_350_VP_ESP_Wankdorf_RP_2019_V191217_Vers200113_bereinig.pdf

- BVD des Kantons Bern. (2022). ESP Wankdorf: Der ESP https://www.espwankdorf.bvd.be.ch/de/start/der-esp.html

- Calthorpe, P. (1993). The Next American Metropolis. Ecology, Community, and the American Dream. Princeton Architectural.

- Charmaz, K. (2002). Stories and Silences: Disclosures and Self in Chronic Illness. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(3), 302–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040200800307

- Chatterjee, S., & Kundu, R. (2020). Co-Production or contested production? Complex arrangements of actors, infrastructure, and practices in everyday water provisioning in a small town in India. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2020.1852408

- Coleman, J. (1958). Relational analysis: The study of social organizations with survey methods. Human Organization, 17(4), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.17.4.q5604m676260q8n7

- Eskafi, M., Fazeli, R., Dastgheib, A., Taneja, P., Ulfarsson, G. F., Thorarinsdottir, R. I., & Stefansson, G. (2019). Stakeholder salience and prioritization for port master planning, a case study of the multi-purpose port of Isafjordur in Iceland. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 19(3), 214–260. https://doi.org/10.18757/ejtir.2019.19.3.4386

- Flyvbjerg, B. (1998). Rationality and Power. University of Chicago.

- Forester, J. (2021). Our curious silence about kindness in planning: Challenges of addressing vulnerability and suffering. Planning Theory, 20(1), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095220930766

- Friedli, B. (2020). Abschluss Phase 2 “Konkretisierung Mobilitätshubs Knoten Bern”. Internal Memo (SBB).

- Frimpong Boamah, E. (2022). Planning as polycentric: Institutionalist lessons for communicative and collaborative planning in Global South contexts. Planning Theory, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952221115871

- Fritz, L., & Binder, C. R. (2020). Whose knowledge, whose values? An empirical analysis of power in transdisciplinary sustainability research. European Journal of Futures Research, 8(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40309-020-0161-4

- Fritz, L., & Meinherz, F. (2020). Tracing power in transdisciplinary sustainability research: An exploration. GAIA – Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 29(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.29.1.9

- Guerra, E., Cervero, R., & Tischler, D. (2012). Half-mile circle: Does it best represent transit station catchments? Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2276(1), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.3141/2276-12

- Habeeb, W. M. (1988). Power and tactics in international negotiation: How weak nations bargain with strong nations. Johns Hopkins University.

- Haugaard, M. (2012). Rethinking the four dimensions of power: Domination and empowerment. Journal of Political Power, 5(1), 33–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379x.2012.660810

- Hickman, R., Garcia, M. M., Arnd, M., & Peixoto, L. F. G. (2021). Euston station redevelopment: Regeneration or gentrification? Journal of Transport Geography, 90(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102923

- Knieling, J., & Othengrafen, F. (2015). Planning culture—A concept to explain the evolution of planning policies and processes in Europe? European Planning Studies, 23(11), 2133–2147. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1018404

- Kohler Riessman, C. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage.

- Kvale, S. (1996). Interview views: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Sage.

- Lu, Y., Prato, C. G., & Corcoran, J. (2021). Disentangling the behavioural side of the first and last mile problem: The role of modality style and the built environment. Journal of Transport Geography, 91(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102936

- Meijer, M., & Van Der Krabben, E. (2018). Informal institutional change in De Achterhoek region: from citizen initiatives to participatory governance. European Planning Studies, 26(4), 745–767. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1424119

- Müller, S. M., Stadler Benz, P., Wehrle, C., & Wicki, M. (2022). Co-Creating Mobility Hubs (CCMH) – Ein transdisziplinäres Forschungsprojekt der SBB zusammen mit der ETH Zürich und der EPF Lausanne. Internal Report (SBB)

- Murphy, J. T.(1980). Getting the Facts: A Field Work Guide for Evaluators and Policy Analysts. Goodyear.

- Nostikasari, D., & Casey, C. (2020). Institutional barriers in the coproduction of knowledge for transportation planning. Planning Theory & Practice, 21(5), 671–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2020.1849777

- O’mundo. (2021). Räumliche Entwicklungsstrategie RES. Gesamtbericht https://www.omundo.ch/wAssets/docs/downloads/2021_Omundo_RES_Gesamtbericht_Web.pdf

- OpenStreetMap. (2022). Default Map Layer https://www.openstreetmap.org

- Papa, E., & Bertolini, L. (2015). Accessibility and transit-oriented development in European metropolitan areas. Journal of Transport Geography, 47(1), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.07.003

- Partzsch, L. (2015). Kein Wandel ohne Macht ‐ Nachhaltigkeitsforschung braucht ein mehrdimensionales Machtverständnis. GAIA – Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 24(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.24.1.10

- Partzsch, L. (2017). ‘Power with’ and ‘power to’ in environmental politics and the transition to sustainability. Environmental Politics, 26(2), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2016.1256961

- Pfetsch, F. R., & Landau, A. (2000). Symmetry and asymmetry in international negotiations. International Negotiation, 5(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718060020848631

- Przeworski, A., & Teune, H. (1970). The logic of comparative social inquiry. Wiley.

- Purkarthofer, E., Humer, A., & Mattila, H. (2021). Subnational and dynamic conceptualisations of planning culture: The culture of regional planning and regional planning cultures in Finland. Planning Theory & Practice, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2021.1896772

- Purkarthofer, E., Sielker, F., & Stead, D. (2021). Soft planning in macro-regions and megaregions: Creating toothless spatial imaginaries or new forces for change? International Planning Studies, 27(2), 120–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2021.1972796

- Reimer, M. (2013). Planning cultures in transition: Sustainability management and institutional change in spatial planning. Sustainability, 5(11), 4653–4673. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5114653

- Reusser, D. E., Loukopoulos, P., Stauffacher, M., & Scholz, R. W. (2008). Classifying railway stations for sustainable transitions – balancing node and place functions. Journal of Transport Geography, 16(3), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2007.05.004

- Rongen, T., Tillema, T., Arts, J., Alonso-González, M. J., & Witte, J.-J. (2022). An analysis of the mobility hub concept in the Netherlands: Historical lessons for its implementation. Journal of Transport Geography, 104(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103419

- Ryan, G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to Identify Themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569

- Sanli, T., & Townshend, T. (2018). Hegemonic power relations in real practices of spatial planning: The case of Turkey. European Planning Studies, 26(6), 1242–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1448755

- Schenkel, W., & Plüss, L. (2021). Spatial planning and metropolitan governance in Switzerland. disP – the Planning Review, 57(4), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2021.2060571

- Scott, J. (1990). A matter of record: documentary sources in social research. Polity.

- SPA und VP der Stadt Bern. (2017). STEK 2016. Gesamtbericht https://www.bern.ch/themen/planen-und-bauen/stadtentwicklung/stadtentwicklungsprojekte/stek-2016/unterlagen/downloads/stek2016-berngesamt-161207-grb-web.pdf

- Taufiq, M., Suhirman, S., Sofhani, T. F., & Kombaitan, B. (2022). Power dynamics in collaborative rural planning: The case of Pematang Tengah, Indonesia. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/23996544221092668

- Thomas, R., Pojani, D., Lenferink, S., Bertolini, L., Stead, D., & Van Der Krabben, E. (2018). Is transit-oriented development (TOD) an internationally transferable policy concept? Regional Studies, 52(9), 1201–1213. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1428740

- Toro López, M., Scheers, J., & Van Den Broeck, P. (2021). The socio-politics of the urbanization - transportation nexus: Infrastructural projects in the department of Antioquia in Colombia through the lens of technological politics and institutional dynamics. International Planning Studies, 26(3), 321–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2020.1850238

- Valler, D., & Phelps, N. A. (2018). Framing the future: On local planning cultures and legacies. Planning Theory & Practice, 19(5), 698–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1537448

- Van Acker, M., & Triggianese, M. (2020). The spatial impact of train stations on small and medium-sized European cities and their contemporary urban design challenges. Journal of Urban Design, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2020.1814133

- Wallsten, A., Henriksson, M., & Isaksson, K. (2021). The role of local public authorities in steering toward smart and sustainable mobility: Findings from the Stockholm metropolitan area. Planning Practice & Research, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2021.1874638

- Wolff, A. (2020). Planning culture – dynamics of power relations between actors. European Planning Studies, 28(11), 2213–2236. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1714553

- Zemp, S., Stauffacher, M., Lang, D. J., & Scholz, R. W. (2011a). Classifying railway stations for strategic transport and land use planning: Context matters! Journal of Transport Geography, 19(4), 670–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.08.008

- Zemp, S., Stauffacher, M., Lang, D. J., & Scholz, R. W. (2011b). Generic functions of railway stations—A conceptual basis for the development of common system understanding and assessment criteria. Transport Policy, 18(2), 446–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.09.007

- Zimmermann, K., & Momm, S. (2022). Planning systems and cultures in global comparison. The case of Brazil and Germany. International Planning Studies, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2022.2042212