ABSTRACT

In Ghana, paratransit services (three-wheeler taxis) have gained prominence because of their role in solving urban mobility challenges in major cities. While they are good at solving urban mobility challenges, they cause accidents and create congestion and inconveniences in the central business districts of cities. However, the literature on how paratransit service operators organise and create spaces for their operations is limited. We draw on peripheral urbanisation theory to understand how the operators produce urban spaces to conduct business in Kumasi. We hope to provide information for the planning and design of infrastructure that meets the needs of the different modes of urban mobility. In doing so, we adopt interviews and focus group discussions involving 35 purposively selected operators, 16 union executives, and two officials from the Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly to elicit the data. The responses were coded and categorised into themes for presentation. Findings indicate that the operators create space through negotiation and site selection. We conclude that securing spaces to conduct business is a major challenge to operators. Therefore, Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly should partner with communities, investors, and operators to create spaces for paratransit operators as it can provide a major source of revenue for development projects.

1. Introduction

In recent times, cities in developing countries are facing the daunting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, austerity measures and the return of the state, rising disenchantment with mainstream economic development policies, and partisan politics, demographic shifts, technological change, and the climate uncertainty (Crisp et al., Citation2023). These challenges and bureaucratic obstacles create a large pool of unemployed persons in developing cities, especially the youth who have naturally gravitated toward the informal economy to seek refuge. The informal economy is a suitable option for the youth because it provides several opportunities to make a living. In this study, the informal economy is conceptualized along the thinking that it is that aspect of the national economy that operates outside official logics but makes a significant contribution to employment generation, and a source of income for several people, especially in developing countries (Ferman & Ferman, Citation1973; Hart, Citation1973; Schneider, Citation2002) albeit several challenges ranging from the lack of secured contracts, health insurance, harassment, exploitation, and worker benefits, or social security (Benjamin et al., Citation2014). Given its nature, the informal economy comprises several and varied categories of people who are engaged as casual day labourers, domestic workers, industrial workers, undeclared workers, and part-time or temporary workers as well as intermediary service providers such as paratransit operations. Paratransit transportation is a common mode of urban mobility in Asia and sub-Saharan African cities. While solving urban mobility challenges, paratransit operations are causing challenges for city authorities in their quest to maintain order and ensure the smooth conduct of business activities, especially in the central business districts (CBDs) where their presence is palpable across the sub-region((Agheyisi, Citation2021; Bamidele, Citation2016). How paratransit operators create spaces and growth in the CBDs across many cities in sub-Saharan Africa is the empirical question this study seeks to answer.

Following Kumar et al. (Citation2021), paratransit is used here to mean the three-wheeler taxis that provide unscheduled routes and stop transport services to urban and peri-urban residents. Three-wheeler paratransit transportation is a logical extension of the informal public transport services to meet urban mobility needs and at the same time a source of employment for those who cannot find jobs in the formal sectors in developing countries (Agheyisi, Citation2021; Bamidele, Citation2016). In Ghana, for example, informal urban public transport; ‘trotroFootnote1’ business are flourishing due to the limited capacity of the formal public transport system to meet the mobility needs of urbanites. However, the operations of the sector have seen little regulation, allowing for an influx of new entrants such as the three-wheelers (Dzisi et al., Citation2021). Recent scholarship shows that three-wheelers have become an essential means of transporting people and goods and delivering services in cities across developing countries in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (Agheyisi, Citation2021). They have become a preferred mode of transportation because of the ease with which they maneuver heavy traffic and bad roads, access neighbourhoods, as well as their prompt response to door-to-door services (Agheyisi, Citation2021; Obiri-Yeboah et al., Citation2022). They are also convenient, reliable, and affordable, attracting urbanites to their utilisation in meeting their everyday mobility needs (Obiri-Yeboah et al., Citation2022). By this, they are filling the urban transportation demand gap created by the simultaneous increase in urban population and horizontal expansion of cities in developing countries (Abdulai et al., Citation2022), which has resulted in increasingly long commutes, more road congestion, and increased formal transport costs. Also, the failure of governments in many developing countries to provide low-cost and reliable public urban transport services is considered an important reason for the flourishing of paratransit services in recent times (Moyo et al., Citation2021; Oteng-Ababio & Agyemang, Citation2015).

However, their operators often face harassment from city authorities in developing cities because they ply their trade on the margins of the official planning, especially in the inner city where they are accused of creating congestion and slowing down traffic. Operators are also accused of causing road accidents with high fatality rates and reports of armed robbery in Ghanaian cities (Jack et al., Citation2021). Amidst all these, previous studies have not prioritised how the operators create spaces in the CBDs to deliver services to the population in sub-Saharan African cities, creating a knowledge gap. Addressing this knowledge gap is important because it will help urban planners and policymakers gain insight into how paratransit operators create and occupy spaces through the exercise of agency and creativity and fashion out policies to accommodate them (Caldeira, Citation2017; Howe, Citation2022). In the literature, urban residents’ exercise of agency to create spaces to conduct socioeconomic activities is what Caldeira (Citation2017) and Howe (Citation2022) describe as peripheral urbanisation. From this perspective, urban residents produce and occupy spaces through their agency and creativity, which are often outside the logics of official planning (Caldeira, Citation2017). The exercise of such agency often unfolds slowly, and transversally interrupting order-making in busy areas in cities (Caldeira, Citation2017). However, Caldeira (Citation2017) avers that the process of peripheral urbanisation is not always on the blindside of city authorities. In the end, the process generates disorder, for example, by producing weakly governed spaces or destabilising local social norms and creates opportunities for local actors to enhance their influence (and, often, also profit financially) by (re)establishing order (Richmond, Citation2022).

We frame the approach adopted by paratransit (three-wheeler) operators in line with the theoretical assumption of peripheral urbanisation and argue that they impose their authority on local populations and markets, and through the practices and routines of coexistence that they establish with local state actors (Richmond, Citation2022), ingraining informal paratransit transport services into the urban fabric. We find this valuable formulation for our analytical concern because of the marginal conditions in which transport innovations from informal processes occur. However, we acknowledge that the infrastructure designs in many cities in Africa and other developing countries do not make room for these services, compelling them to rely on informal processes to access spaces within the inner-city areas. This is observed among paratransit service operators in many cities across the developing world (Doherty et al., Citation2021). Because of the growing importance of this transport mode in solving urban and peri-urban mobility problems and the contestations they have generated, several studies have been conducted on them in cities across the developing world (Agheyisi, Citation2021; Lenshie et al., Citation2022; Obiri-Yeboah et al., Citation2022). For example, the work of Doherty et al. (Citation2021) in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, indicates that these vehicles are relegated to the margins of the city through a deliberate policy of banning them from operating in the CBD. On the other hand, Lenshie et al. (Citation2022) focus on the political economy and urban mobility and report that their emergence has led to road infrastructure improvement, reduced road crashes, minimized motorcycle-induced crimes, and improved the income of informal transport operators in Nigerian cities. These studies, although necessary, should have discussed how the operations are organised, how they auto-create spaces to operate, and how formal institutional restrictions relegate them from opportunities in the CBDs.

We take up these issues in Ghana because the growth in the number of three-wheelers is happening despite the existence of legislation (Road Traffic Act Citation2004, Act 683) precluding their use for commercial purposes or transport fare-paying passengers in the country. Suffice it to say that the presence of three-wheelers on the streets of small and large cities has outpaced the capacity of local authorities to manage, as evidenced in major cities such as Accra, Kumasi, and Tamale (Jack et al., Citation2021; Mohammed & Quartey, Citation2023)., However, it appears that local authorities in many cities in the country are now seeking to enforce Act 683 by banning their operations, especially in the CBDs. For example, the Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly (KMA) banned the operations of three-wheeler taxis in the CBD of Kumasi on 25 July 2023, because their activities contravene Act 683 and at the same time impede traffic flow and the smooth operation of businesses. The ban was followed by fierce protests, leading to scuffles between the operators and law enforcement officers. Similar bans and reactions have also been reported in other cities, including Accra, the country’s capital. However, such bans are often short-lived. How did we come to this point? Previous studies have ignored how these operators auto-create spaces to conduct business. This prompts us to fill the knowledge gap by (1) analysing how the three-wheeler operators organize their activities (2) examining the mechanisms by which they autonomously produce urban spaces to conduct business in the CBD and (3) exploring how their removal from the CBD further marginalised them from the opportunities thereof.

The study is timely because, to the best of our knowledge, there are no plans to formalise and professionalise this popular urban transport mode into urban transport infrastructure. Also, their place in the city’s future needs to be more specific and clearer. Understanding the organisational structure of the operators and how they auto-produce spaces will help inform policy makers to integrate them into the urban transportation architecture not only in Kumasi but in other cities in sub-Saharan Africa. The rest of the paper is structured as follows: In section two, we discuss the theoretical framework on which the study is anchored, followed by a discussion of urban transport systems in African cities and empirical evidence from developing countries in section three. In section four, we discuss the institutional, legal, and policy frameworks on urban public transport in Ghana before proceeding to present the methodology adopted to carry out the study in section five. The methodology section covers the study area, study design, and analytical procedures before proceeding to the results in section six. Section seven discusses the results, while the implications of the findings for theory, policy, and planning constitute section eight. The conclusions, and recommendations for urban planning end the paper.

2. Theorising the autonomous production of urban spaces for paratransit services

In late October 1957, Marxist student leaders, and communist architects moved into a state property in Santiago, Chile (Reis & Lukas, Citation2022). This was in response to the housing challenges residents faced in the city and the occupation of the state property was a form of adaptable solution (Reis & Lukas, Citation2022). This event perhaps marked the turning point in urban theory in the Global South. This is because it drew the attention of urban scholars in the South that the top-down theoretical approach to urban studies is not always the case. The event in Chile is best described as peripheral urbanisation. The new urban theory is therefore inserted at the confluence of critical urban geography and planetary urbanisation frameworks that ruled urban studies discourse during most of the 20th century (Reis & Lukas, Citation2022; Vindigni et al., Citation2021). The theory projects ordinary urban dwellers as those who construct the city through their agency and creativity to claim and gain legitimacy to water, housing, land, and others. that make life comfortable (Reis & Lukas, Citation2022). In the literature, the expression of agency and creativity to claim and gain legitimacy in urban spaces is termed auto-construction. Thus, the theory describes how citizens, especially those living in poverty produce urban spaces through auto-construction, generally outside the official framing of planning but not directly confronting state agencies in their quest to achieve their objectives (Caldeira, Citation2017; Howe, Citation2022). Auto-construction can also take the form of alliances in which urban dwellers gain the right to participate in the capitalist systems (Kamath & Kotal, Citation2023).

Suffice it to say, three elements underpin peripheral urbanisation theory. To begin with, actors operate with a specific agency and temporality. This implies that residents produce urban spaces using available resources (finance, hired, or own labour) and alliances in a piecemeal and slow unending fashion (Caldeira, Citation2017; Kamath & Kotal, Citation2023). Second, they frequently unsettle official logics but do not openly contest them directly as much as they operate with them in transversal ways. Caldeira (Citation2017) argues further that residents engage in laws, regulations, occupation, planning, and speculation, and by this, they shape those logics that result in heterogeneous urbanisation and remarkable political consequences. Third, they generate new modes of politics through practices that produce new kinds of citizens, claims, circuits, and contestation, creating a political environment often characterised by unstable conditions of tenure, the skewed presence of the state, precarious infrastructures, exploitation, constant abuse by state institutions, stigmatization, and discrimination (Caldeira, Citation2017). These unfavourable conditions create a new form of democratic practices that are deployed tactically to secure legitimacy and the right to the city and enhance the influence of residents in the governance process (Caldeira, Citation2017; Narayan, Citation2023). The tactical deployment of strategy to secure legitimacy and claims to the city is captured in the work of Narayan (Citation2023). Narayan demonstrates how women ceded territorial and spatial autonomy to secure political gains in India by not resorting to protest when an auto-constructed Daycare centre was demolished. The revelation tells us that the interaction between the agents and official logics is not always contentious when agents choose to tactically engage in the production of urban spaces. However, scholars such as Caldeira (Citation2017) and Porreca and Janoschka (Citation2024) draw our attention to the fact that the activities of residents in the auto-construction process are usually not covert as they interact with state institutions but transversally; escaping the official framing of planning because each of the steps they take is carefully planned. The process by which residents secure their place and claims in the city is often through the production, modification, and remaking of urban spaces (Caldeira, Citation2017; Salazar et al., Citation2022). In acting from the margins, ordinary inhabitants of the city can be found in capitalist land markets, credit, transportation, and consumption albeit in special niches that escape the official framing of planning (Caldeira, Citation2017; Kamath & Kotal, Citation2023). However, urban dwellers’ adoption of auto-construction to claim and gain legitimacy often evokes a wide range of conflicts and tensions (Horn et al., Citation2021), leading to struggle and resistance, and organised approaches as responses (Porreca & Janoschka, Citation2024). We draw on this theory to understand how paratransit operators engage with or otherwise with the official logics to create urban spaces. In doing so, we uncover the underlying dynamics within the urban space production processes.

3. Public transport systems challenges and the emergence of urban paratransit services in African cities

This section of the paper presents a conceptual and empirical literature review of public urban transport systems in African cities and seeks to understand how their failures or otherwise engineered the emergence of paratransit services in response to urban mobility challenges. Well-functioning urban transportation system is a reliable indicator of economic development because of its potential to stimulate economic growth, generate employment opportunities, and improve the effectiveness and efficiency of businesses (Aidoo et al., Citation2013). Also, efficient urban transportation systems provide other essential benefits including reduction in travel expenses, improved access to workplaces, health facilities, schools, service infrastructure, and other places that make cities attractive and liveable (Aidoo et al., Citation2013; Kumar et al., Citation2021). Regrettably, governments in developing countries are struggling to find the most efficient ways of moving people in and around cities (Kumar et al., Citation2021). Part of the problem is the increase in urban population and subsequent demand for transport, and space for social, economic, and civic purposes (Abdulai et al., Citation2023). In recent times, the extremes of climate change and its impacts, food security, unemployment, road safety, and now the COVID-19 pandemic have fetched up a new set of challenges for decision-makers in developing cities (Crisp et al., Citation2023; Kumar et al., Citation2021). Based on these challenges, city authorities, and decision-makers, for example, in African cities are struggling to fashion out policy frameworks to provide a set of choices that meet the conflicting objectives and constraints of urban mobility (Kumar et al., Citation2021; World Bank, Citation2022). In many cities, urban mobility challenges are first, because of the increased motorisation, and second, the limited and inefficient formal public transit services that undermine the movement of people and haulage of goods (Obiri-Yeboah et al., Citation2021). The failure of the urban public transport systems to keep up with the growth of cities makes the informal transport sector an attractive and preferred mode of travel among urban residents in developing countries (Kumar et al., Citation2021; Lenshie et al., Citation2022; Obiri-Yeboah et al., Citation2022; World Bank, Citation2022). The sector thus employs a large proportion of the overall workforce in developing cities albeit with limited or non-existent regulations. Nowadays, the informal transport operators must step in to provide effective, reliable, and affordable transport modes to urbanites, with many of them spending up to 25% of their annual income on transport within the cities across the developing world (Poku-Boansi & Adarkwa, Citation2013). However, the increase in informal transport vehicles overwhelms the capacity of the roads, increasing pollution, accidents, and congestion on the roads of many cities in developing countries (Kumar et al., Citation2021; World Bank, Citation2022).

The informal public transport services are provided by private individuals who own and operate small (e.g. sedans, vans) or medium-sized used vehicles imported from high-income countries at a much lower cost (World Bank, Citation2022). Such vehicles in Africa, are usually leased to drivers on daily basis or for a particular period (World Bank, Citation2022). The arrangement makes drivers unsalaried individual entrepreneurs who pay all daily out-of-pocket expenses (e.g. fuel, minor and major repairs) in addition to the basic lease. Therefore, they have a huge incentive to compete on the street for customers. This situation leads to chaotic, erratic, unsafe driving, and congested environment, far beyond what the number of public transport vehicles in the traffic stream would suggest (World Bank, Citation2022). Recently, urban mobility challenges in developing cities have generated a pressing need for alternative transport modes to complement the efforts of conventional systems. In response, the paratransit modes of urban transport (three-wheeler taxis) in the informal transport sector contribute to solving urban mobility challenges in developing countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. The need for a paratransit mode of travel in urban areas arises from the inability of the conventional modes of public transport to adequately meet the needs of residents as cities expand and population increases (Agheyisi, Citation2021; Doherty et al., Citation2021). The physical expansion of cities has resulted in increasingly long commutes, more road congestion, and increased transport costs, necessitating alternative transport modes (Doherty et al., Citation2021). The rapid expansion of many cities also implies that certain areas will lack good roads and other infrastructure to ease urban mobility, making the three-wheeler taxis an alternative mode for moving people in and around the cities. Agheyisi (Citation2021) argues that the three-wheeler taxi mode comes in handy because of its ability to reach interior parts of urban areas that are not well linked to good roads. However, Doherty et al. (Citation2021) draw our attention to the fact that three-wheeler taxis emerged at the intersection of spatial, infrastructural, legal, regulatory, and socio-economic marginalities. These marginalities compel operators to seek adaptable solutions and one of the ways is to auto-produce operation spaces in urban areas, leading to multiple challenges such as police harassment (Obiri-Yeboah et al., Citation2022). Because they are often unorganised and unregulated, operators are also accused of causing congestion, road traffic accidents, violation of traffic regulations, and careless driving among others that in most instances portray them as lawless. This has led to bans and restrictions on their activities across sub-Saharan African cities (Agheyisi, Citation2021; Obiri-Yeboah et al., Citation2022).

The emergence of the three-wheeler taxis has different histories in sub-Saharan. In Nigeria, for example, they were introduced in Lagos as an economic empowerment mechanism as far back as 1996, and in 2004, the Federal Government imported and distributed to the youth as an employment generation strategy (Agheyisi, Citation2021). Later, businessmen and women joined the fray and imported several thousands of these modes of transport into Nigeria (Agheyisi, Citation2021). In the case of Ghana, these vehicles burst onto the urban transport space in 2015 as an addition to the vehicular mix in peri-urban and urban areas. They serve a good purpose and fill a niche in the transport market in Ghanaian cities (Adomabea et al., Citation2023) albeit Act 2004, Act 683 prohibiting their use for commercial purposes. Ghana’s urban mobility challenges have been shaped by a combination, since the 1980s of rapid urban growth (both in terms of population and surface area) and the crawling public transit systems (Ayalolo). The urban mobility challenges in Ghana are also compounded by the increasing trend in road traffic crashes, traffic congestion, and emission of carbon dioxide (Aidoo et al., Citation2013). The impact from road traffic congestion compounds carbon emission, and road crashes as well as pollution, and economic losses (Aidoo et al., Citation2013).

Previous studies on three-wheeler transport have concentrated on India and other parts of Asia, where they are mostly manufactured and used (Bagul et al., Citation2021; Harding et al., Citation2016; Xu (Citation2021). However, literature on this new form of urban transportation in sub-Saharan Africa is still evolving (Agheyisi, Citation2021; Doherty et al., Citation2021; Lenshie et al., Citation2022; Obiri-Yeboah et al., Citation2022). For instance, the work of Agheyisi (Citation2021) in Benin City in Nigeria explores the mobility practices of three-wheeler taxi riders, focusing on their organisational structure. The study revealed that the riders delineate the city into a decentralized and fragmented system of territorial monopoly and found that operators are unionised and organised into several units with each unit controlling a specific neighbourhood and confined to certain roads. In Abidjan, Ivory Coast, Doherty et al. (Citation2021) reported that they operate at urban peripheries where they provide a low-cost service to residents. Obiri-Yeboah et al. (Citation2021) characterised operators in Kumasi, Ghana, and found that the income generated is influenced by training, union membership, and type of transport activity. However, the operators do not comply with road safety and traffic regulations irrespective of the educational level and training received. Obiri-Yeboah et al. (Citation2022) further revealed that operators earn substantial amounts of money from their activities although most of them have no or limited formal education. However, operators often face harassment, high cost of fuel, and careless driving among others as challenges. On the other hand, these vehicles are allowed to operate within cities in Nigeria and this has led to the development of road infrastructure, reduced road crashes, minimized motorcycle-induced crimes, and improved the income of operators (Lenshie et al., Citation2022). Owusu-Ansah et al. (Citation2022) focused on the employment potentials of the three-wheeler taxis among mechanics and services engineers in Kumasi and reported that it provided a source of income although most of them did not receive formal apprenticeship training. Although these studies improve our understanding of the operations of these taxis in African cities, there is no sufficient knowledge of the organisation of the operations, the mechanisms by which they create urban spaces, and the adverse consequences of their removal from the CBDs. This study fills this gap in knowledge through a qualitative research approach to unearth the nuances of the operations of three-wheeler taxis in Ghanaian cities. The fashioning out of appropriate policy interventions that seek to integrate the paratransit operation for urban sustainability is the utility of this study.

4. Institutional, legal, and policy framework on public urban transport in Ghana

Ghana’s public transport institutional architecture is fragmented. The sector comprises ministries (Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development (MLGRD), Ministry of Roads and Highways (MRH), Ministry of Transport (MoT), Ministry of Finance (MoF), Ministry of Environment Science and Technology and Innovation (MESTI), and Ministry of Road Development (MRD)), national authorities (e.g. Driver and Vehicle Licencing Authority), state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and metropolitan, municipal, and district assemblies (MMDAs) and driver unions. The Ministry of Transport, for example, is responsible for policy formulation and provision of public modes of transport, while national authorities, SOEs, and MMDAs manage and maintain state transport infrastructure (African Transport Policy Programme & Republic of Ghana, Citation2020). Given the large number of ministries involved in the transport sector, the role of the MoT has not always been clearly defined: it has the responsibility for transport sector policy formulation and coordination. In recent years, the MRH drives the urban transport sector as the main provider of road transport infrastructure (mainly through the Department of Urban Roads, and Ghana Highways Authority). As a result, it manages large amounts of financing and benefits from strong technical capacity. Yet, the laws of Ghana give the MMDAs the mandate to manage urban transport. As a natural consequence, the MLGRD should be clothed with responsibility at the national level (African Transport Policy Programme & Republic of Ghana, Citation2020). However, this responsibility is yet to be supported by the ministries. Thus, the urban mobility sub-sector is currently split between various institutions and remains without a champion, making it difficult to regulate urban transport in Ghana (African Transport Policy Programme & Republic of Ghana, Citation2020). Policy-wise, the 2008 national transport policy recognizes the importance of the informal urban transport sector. This is because the sector transports 68% of the passengers in and around cities in the country (Republic of Ghana, Citation2008). Given the dominance of the informal transport sector in urban mobility, the state recognizes the importance of private sector players such as the Ghana Private Road Transport Union (GPRTU), the Progressive Transport Owners Association (PROTOA), and the Ghana Co-operative Transport Association (GCTA). Suffice it to say that there is no national body mandated to develop regulations for transport operations and services in Ghana, leading to the lack of formal coordination mechanisms of the multiple actors in the sector (African Transport Policy Programme & Republic of Ghana, Citation2020; Dzisi et al., Citation2021). Apart from that, the limited funding from the central government and the inability of the MMDAs to generate internal funds for urban transport infrastructure investment compounds the problems in the sector (African Transport Policy Programme & Republic of Ghana, Citation2020).

5. Methodology

5.1. Study setting

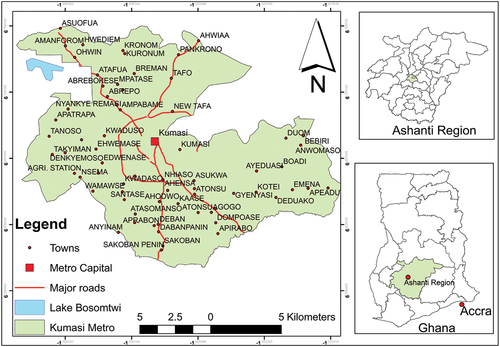

The study was conducted in the local government areas of Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly (KMA). Kumasi is the capital city of the Asante State built from a voluntary amalgamation of several city-states that existed during the precolonial period. The Asanteman Traditional Council is the traditional governing authority of the city (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014). Kumasi, the capital of the Kumasi Metropolis in the Ashanti Region of Ghana, covers an area of 214.3 km2 and is the second largest and most populous city in Ghana. Kumasi hosts one of the largest markets and transport terminals in West Africa: Kejetia Central Market and Terminal. The strategic location of Kumasi in the southern part of Ghana has given it a pivotal role in the distribution of goods and services to other cities in Ghana and other West African countries. As the commercial hub of the country, Kumasi has witnessed significant growth both in size and population. According to the Ghana Statistical Service (Citation2021), the city is host to 443,981 residents with 230,318 of them being female. The size of the population coupled with the physical expansion of the city has resulted in people living in distant areas from the CBD leading to increasingly long commutes, more road congestion, and increased transport costs. Its strategic location between Latitudes 6.35° N and 6.40° S and Longitudes 1.30° W and 1.35° E makes it the convergence point for businessmen and women from the northern and southern areas of Ghana (). It also shares administrative boundaries with eight other municipal and district assemblies including Kwabre East, Afigya Kwabre, Atwima Kwanwoma, and Atwima Nwabiagya. Others include Asokore Mampong, Ejisu-Juaben, and Bosomtwe (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014). Most of the population (66.5%) are economically active and as such are engaged in the transportation and storage activities, agriculture, manufacturing, wholesale, and retail sectors, financial and insurance activities. The rest of the sectors that employ the residents are tourism, accommodation and food services, and repair and maintenance services (Ghana Statistical Services, Citation2014). In Kumasi, road transport is the common mode of transportation, with a road network of more than 1,931 km. The road network depicts a radial structure with the Ring Road engulfing the CBD and linking Kumasi to the nation’s capital, Accra, Obuasi, Cape Coast, and Takoradi, and to the northern territories. Thus, Kumasi plays a pivotal role in the development of the country through commerce, industry, and services, attracting physical and population growth.

5.2. Study approach

A qualitative research approach was adopted to carry out the research. Qualitative research is a nuanced approach focused on exploring the richness and complexity of human experiences. In doing so, researchers using the approach delve into the subjective aspects of a phenomenon, using interviews, focus groups, and participant observation (Thorne et al., Citation2016). The approach prioritises in-depth understanding, context, and participant perspectives as they investigate an issue of interest. This approach is particularly apt for studying social phenomena, cultural contexts, and complex human behaviours. Qualitative research embraces flexibility, allowing researchers to adapt methods as they uncover new insights (Ramani & Mann, Citation2016). It provides a holistic view, often generating hypotheses for further quantitative exploration. Its strength lies in capturing the depth and diversity inherent in human experiences. Specifically, we draw on the phenomenological research design which involves understanding people’s perceptions and interpretations of an issue of interest (Christensen, Citation2017; Gee et al., Citation2013). The use of the phenomenological research design allows the researcher(s) to rely on the lived experiences of the participants to bring to the foreground knowledge and nuanced understanding of a phenomenon (Christensen, Citation2017). It also allows the researcher(s) to reflect over and interpret the life-world experiences in a nuanced and diverse way considering the context, language, culture, and politics in which the participants operate (Adams & van Manen, Citation2017). In doing so, all dimensions of the phenomenon under investigation are well articulated, allowing readers to engage with the findings meaningfully (Mortari et al., Citation2023). Here, we used interviews to elicit data on the lived experiences of the operators and relevant state agencies to reflect on the operations of the three-wheelers and their autonomous processes of creating spaces in the CBD. We adopted the design because it permitted us to provide nuanced descriptions and interpretations of the findings in ways that reflect the lifeworld of the operators to the foreground of knowledge and understanding of autonomous urban space production (Christensen, Citation2017). The design is also useful for this study because it provided the opportunity for participants to share their perspectives and in-depth insights that could enhance our understanding of their modus operando and provide guidance on how to integrate them into the urban fabric to secure sustainable livelihoods.

5.3. Sample size and sampling

The purposive sampling techniques were used to select three-wheeler operators, executives of stations (Unions), and officials of the KMA to participate in the study. This sampling technique entails the selection of research participants based on their knowledge and experiences concerning an issue under investigation. In doing so, 35 three-wheeler operators, 16 station executives, and two officials from the KMA were selected. The research participants were selected because of their rich knowledge and experiences of the issues regarding this study (organisation, space creation, and challenges encountered by the operators because of their removal from the CBD). In the case of the operators, at the 35th person interviewed, no new data were reported and thus, we terminated the conversation as prescribed in previous literature (Lowe et al., Citation2018; Mwita, Citation2022) Qualitative data collection could be stopped when the nth participant adds no new relevant data to the previous ones collected. The point at which qualitative data is terminated because of the absence of new data from an additional person interviewed is known in the literature as the data saturation point (Kerr et al., Citation2010). In all, 53 people participated in the study. Before the data collection, the data collection guides (interview guides, and focus group discussion guide) were reviewed by the Research and Ethics Board of the SD Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies. The review process lasted four months before final approval was granted to proceed with the data collection. This was after review comments were addressed and resubmitted. A letter was also written to the KMA seeking permission to interview relevant officials and approval was given. Furthermore, the operators and executives on their own accord agreed to participate in the study after the purpose and the objectives of the study were explained to them.

5.4. Data collection and analysis

Interview and focus group discussion guides were utilized to collect data from the research participants. The interview and focus group discussion questions centered on the objectives of the study. Some of the questions included, ‘How is the operation of the stations organized?’, ‘Do you have station executives?’, ‘What is the role of the station executives?’, ‘How did you secure space to conduct your business in CBD (Kejetia)?’, ‘Were the KMA officials aware of your operation in the area?’; among others. In the case of the officials from the KMA, some of the questions were, ‘How would you describe the activities of the three-wheeler operators?’, ‘Did your office grant them permission to operate from the CBD?’, ‘Do you have plans to integrate them into the urban road infrastructure design?’, ‘Why did you ban them from operating in the CBD?’ among others. All the interviews and focus group discussions were tape-recorded with the permission of the research participants and later transcribed. The interviews and focus group discussions with the operators were conducted in both English and Twi (local language), while interviews with the officials of the KMA were conducted in English language. The interviews and focus group discussions lasted for an average of 48 minutes and were later transcribed for analysis. The transcripts were then coded using NVivo version 11. Initially, 210 codes were generated. After careful reading and discussion among the researchers, codes that shared similar attributes were merged to generate 28 new codes. Thereafter, the 28 codes were merged into three themes based on the research objectives. The themes were supported by direct quotes and narrations picked from the interview transcripts for presentation. To ensure the validity and reliability of the findings, a member check was conducted. The findings of the study were presented to some of the research participants for review and confirmation. This was done after one month from the initial data collection period.

6. Results

6.1. Organisation of paratransit services

Here, we present the findings on how the operators exercise agency and creativity to organise and operate in the CBD of Kumasi also known as Kejetia. Specifically, the operations are organised around routes to several parts of the city, with members joining voluntarily based on a basic assessment of their characters, and the roadworthiness of the three-wheelers. Operators of each route are also required to purchase and paste stickers of the station on their three-wheelers. Some of the routes they ply their trade are those linking to Suame, Asawase, Suame, Aboabo, Mampongteng, and Formas. Suffice it to say, the central operation point of the three-wheelers is at Kejetia where they pick up and drop off passengers. An operator noted that

We pickup passengers from Kejetia to almost all the areas in Kumasi. However, individual operators don’t go in all directions. One must choose a particular route and operate there as soon as they join the stations. This way, operators can be located and identified by passengers. We attract the passengers by announcing where we are loading and the direction we are going.

An operator from the Asawase Station corroborates the assertion by saying.

Here in Kejetia, we operate the Asawase route. We pick up and drop off passengers at Kejetia. So, the people who patronise our services know where they can find us. We also display a signpost indicating the route we operate from Kejetia. So, it is easy for passengers to locate where they can take the three-wheelers to their destination’. (Interview with an Operator 29th September 2023)

The narration illustrates the dynamics of three-wheeler operations within the contested urban spaces not only to conduct business but also to make it easy for passengers to locate them.

Apart from the routes, the operators are organised around unions with five executives. The executives include the chairman, vice chairman, secretary, organiser, and treasurer. They are responsible for the day-to-day organisation of the station, the operators’ welfare, and the security and safety of their passengers. The executives help them to be united and at the same time promote the welfare of members. In the case of the passengers, the executives encourage them to report cases of misbehaviour and unprofessional conduct of operators when they patronise their services. They also take custody of lost but found items that belong to passengers and release them when owners show up. An executive from Mampongteng Station (12 September 2023) reveals in an interview that.

Our job is to promote the welfare of members and protect our clients. We also encourage passengers to report operators who misbehave or are involved in careless driving when they are on board so that disciplinary actions can be taken against them. Furthermore, we also ensure that passengers’ items left in the three-wheelers are brought to the station for safe keeping so that when the owner shows up, we give the items to them. This helps to build trust between us and the passengers .

The narration shows that the auto-constructed organisation of activities does not only seek the welfare of their members, but they are also interested in the safety of those they seek to serve.

On the qualification of joining the stations, the fundamental requirement is that members voluntarily elect to join. Thus, there is no compulsion to join any station. However, it is observed that people join the stations based on the areas they live. For example, most of the operators of the Suame station in Kejetia live in and around that area. According to the operators, working in areas where they reside is advantageous because they know the area well and may have built acquaintances with other residents. An operator (10 September 2021) asserts that:

We are not forced to join any station. All of us voluntarily joined the various stations based on the fact we feel safe and comfortable operating in areas where we reside. It also makes it easy for us to relate with the people and maneuver the roads to pick up and drop off passengers.

Another qualification for joining a station is good character. It is observed that operators must possess good character to be admitted to a station. The station executives assess the individual’s level of responsibility, such as his ability to remain calm, drive carefully, and adhere to road traffic regulations. They also assess the individual’s ability to ensure the safety and security of passengers through practices that help to prevent mistakes and accidents on the road.

Thirdly, the roadworthiness of the three-wheeler is also assessed before operators are permitted to join a station. According to the operators, the check is to ensure that the safety of operators and passengers alike is guaranteed on the road and that it does not break down frequently or develop mechanical failure while on the road, helping to reduce the risk of accidents. An executive from Ahodwe Station (17 August 2023) explains.

The safety of operators and passengers is important to the group. This they ensure by insisting that only roadworthy three-wheelers are admitted to the station. Three-wheelers that do not satisfy this condition are not permitted to join the station since they get involved in accidents or cause inconvenience to passengers and tarnish their image which can cost them sales .

This highlights the structures put in place by the operations not only to support territorial management but as a reflection of a self-governing body that can be utilised by the city authorities to engage with them.

Finally, each member is required to purchase and paste the station sticker on their three-wheelers. The stickers serve two purposes. First, they help to identify which station the operators belong to; so that in the event of a problem or loss of an item they can easily be traced for resolution and item collection. Second, they provide a source of funds for the administration of the station. With the funds obtained from the sale of the stickers, petty expenses such as payment of market guards, assisting members to do minor repairs, and supporting members during social ceremonies such as marriage, naming ceremonies, and funerals are taken care of.

6.2. Mechanisms of auto-construction of urban spaces for paratransit services in the CBD

Two mechanisms are adopted by the operators to produce space to conduct their businesses. First, the operators auto-produce space to conduct their businesses through negotiation with shop owners in the CBD. According to the operators, when they find a space in front of a shop that can be utilised as a loading point, they seek to negotiate with the shop owner to allow them to pick up and drop off passengers from the point. In this instance, they are not required to pay dues or charges for using the space. A station chairman (20 August 2023) intimates that:

My brother, Kejetia is congested, and it is difficult to secure space to conduct our business. But we must do this business to survive. Therefore, we must find ways to get space to do the business. One way we secure space is that when we find that there is a small space, especially in front of shops, the leaders of the said station approach the shop owner to negotiate to temporarily use the space.

The point to note here is that the auto-construction of urban spaces does not only involve public spaces, but it could also involve private spaces for the benefit of urban dwellers and businesses.

The arrangement with shop owners comes with conditions that must be abided by the operators while utilising the space. First, the operators must not block the entrance to the shop by parking directly at the entrance of the shop or dropping passengers there. Second, the operators must not engage in physical or verbal quarrels with each other or passengers. Third, only two three-wheelers are permitted to be at the frontage at a time. Finally, they should be ready to vacate the space when the need arises. Adhering to the conditions is to ensure the smooth conduct of the businesses of the shop owners and that of the operators. An operator from Aboabo Station explains this point in the following.

Some shop owners at Kejetia allow us to use their frontage to pick up and drop off passengers. However, we must adhere to some conditions to operate there. One of the conditions is that we must not park directly at the shop entrance so that clients are blocked from accessing the shops and patronising the goods and services offered (Interview with an operator 10th August 2023)

While auto-construction is often considered as an unconventional tool to produce urban spaces, there is also a wealth of dynamics involving other players in the urban space that is often overlooked.

Also, the operators do not pay charges or dues for using the space. The operators do not pay because the shop owners empathise with them for trying to make ends meet. Others also claim that they are related to some of the shop owners and as such could not be asked to pay for using their frontage. A shop owner at Kejetia (5 September 2023) corroborates the assertion made by the operators in the following statement.

Life is hard these days and everybody is struggling to make ends meet. So, when the operators approached me to use the frontage of my shop to pick up and drop off passengers so that they could also earn some income for themselves and their families, I saw no reason why I should ask them to pay money. The shop owners sometimes benefit from them because when people come to board the three-wheelers sometimes, they buy items or patronise the services offered by the shop.

However, the officials indicate that the KMA is unaware of the arrangement between shop owners and paratransit operators to utilise their frontage to conduct business. The KMA officials explain that such an arrangement is an affront to the laws governing the agreement between them and the shop owners. An official from the KMA states (16 September 2023) that

I am not aware of such an arrangement between the shop owners and the three-wheeler operators in the CBD. Indeed, if such an arrangement exists then it is illegal and violates the terms of agreement between the KMA and the shop owners.

The ‘Operate and Wait Approach’ is another way the operators adopt to produce space to conduct business. When the operators identify an open space, first, they would move in there without formal authorisation to conduct their business, as they seek informal agreements with the KMA police. From the interviews, when an open space is identified in the Kejetia Market, the operators will first move into and start using the space to conduct their business while waiting for the KMA officials to approach them for either eviction or negotiation to use the space temporarily. Often, they succeed in convincing the KMA to allow them to temporarily use the space. An executive from the Suame Station on 18 September 2023 narrates.

When the three-wheeler started coming into Ghana and we saw the business opportunities, I looked around town to find space to use for loading and dropping passengers. I did not seek permission from the KMA, I just got to the space and started the business and later others joined me. This is how we started the station. After a while when our numbers started to increase, the KMA started to harass us to vacate the place, but we are still here.

Often, the spaces occupied by the operators are undeveloped portions, and sites of demolished structures. It is observed that when neglected and unsafe infrastructure is pulled down for redevelopment and upgrade, often work stalls for some time, allowing operators to move in to use such spaces until such a time that development is ready to commence. Such spaces are therefore sites for stations for the three-wheeler operators in the Kejetia area. An operator narrates (10th September 2023) one instance in the following.

A story building in the Adum area was demolished to pave the way for the construction of a multipurpose structure. However, the redevelopment of the site stalled for some time. During that period some of the three-wheeler operators moved in there to conduct their business and turn it into the station for several areas in the Kumasi township. They were only recently evicted by the KMA. However, all that while, the KMA was charging the operators for using the space.

The approach is also adopted to occupy the shoulders of roads in and around Kejetia. The roads in Kejetia are narrow and very busy during peak periods but the paratransit operators must also find space to park to pick up and drop off passengers. As a result, the shoulders of the road are sometimes utilised. This approach often incurs the displeasure of the KMA guards compelling them to chase them from such places daily. For paratransit operators, this is a common approach to secure space to conduct business. An operator from Asawase station intimates.

The CBD is full without space for us to operate. During the construction of the Kejetia Market, I think they did not envisage that three-wheelers would become a popular mode of urban transportation, and as such did not incorporate in the project design a place for three-wheelers. Now we are here and every day, we are ‘fighting’ with KMA police over the use of the shoulders of the roads to load and drop passengers. (Interviewed with an operator on 7th September 2023)

Officials of the KMA corroborate the assertion of the operators that the operate-and-wait approach is one of the mechanisms by which paratransit operators create spaces for their activities. An official from the KMA (18th September 2023) statess the following.

They are found everywhere in the city and the CBD. They try to use every available space, especially in the CBD to pick up and drop off passengers and sometimes this happens on the shoulders of the road, thereby causing inconveniences and accidents.

Nevertheless, the operations in unauthorised spaces within the CBD require that they pay tolls to the KMA. According to the operators, although the KMA did not approve of their use of spaces in the CBD, officials collect daily tolls from them. This somehow legitimises the activities of the operators in such spaces to conduct business. An operator (18th September 2023) explains the point in the following.

Although we were not granted permission to utilise some spaces in the Kejetia Market area, officials often come to us to collect money as payment for using the space. The KMA charges operators for using a particular space but sometimes they turn around to say that we are using the space illegally.

This description shows that although the KMA is unable to provide spaces for paratransit service vehicles, it is benefiting from their activities. Further probing reveals that the operators are required to pay tolls although they operate illegally in the CBD. However, the officials were quick to add that the toll payment is not tied to their operations in the CBD, but as an internal revenue generation mechanism.

6.3. How the removal of three-wheelers from the CBD further marginalized operators

Recently, the KMA banned three-wheeler operations from entering the CBD. The ban was an enforcement of the Road Traffic Act, Citation2004 Act 683 that prohibits their use for commercial purposes. The bans was also to ease traffic congestion, enhance pedestrian safety, and restore sanity in the space for the conduct of businesses. As a result, it is important to understand how the removal of the three-wheeler operators from the CBD affected them. Officials from the KMA, however, revealed that the operators were engaged to find an amicable solution to the insanity in the CBD. The engagement did not yield the desired outcomes as the operators were not ready to move out of the place. This compelled the KMA to force them out to restore sanity on the roads in and around the CBD. An official from the KMA (18th September 2023) stated that ‘We tried to engage the operators, but they were reluctant to leave so we had to apply force to clear them off’.

However, the removal of the three-wheelers from the CBD affects them in four ways, limited access to passengers, declining incomes, limited access to social amenities, and limited access to repair and maintenance. Their removal from the CBD has led to a decline in access to passengers around which the business revolves. For the operators, it was easy to attract passengers at Kejetia because everyone goes there to do one business or the other. As a result, it was not difficult to attract passengers there. With the ban, the operators now struggle to attract passengers to patronise their services at their current locations. An operator (16th September 2023) describes the issue in the following way.

Several people go to the Kejetia area each day. This means that they will require means of transport to and from the area and the three-wheelers were also there to meet the travel needs of the people. However, with the ban, the operators have limited access to the passengers who constitute the clientele base.

An FGD session with the executives (20th September 2023) reveals the following:

When they were operating from the Kejetia area, they had access to large number of people to transport. An operator could load more than 15 times from the station in a day. There were days when some of them had to decline an invitation to load because of fatigue. But now, it is difficult to load more than three times from the current location.

The limited access to passengers contributes to a decline in the incomes and consequently sales of the operators. Because of this, their daily sales have reduced, affecting their income compared to the period they operated from the CBD. Previously, operators could make as much as GHC 300.00Footnote2 each day when they were operating from the CBD, but this has reduced to a paltry GHC 90.00. An executive from Fomas Station on 15th September 2023 lamented their situation in the following statement.

We could make a lot of money from the business when we were operating in the Kejetia area. There was no free time for us because the passengers were always available to picked and dropped and so we were making a lot of money. But now, we can’t make that much from the business. For instance, I made only GHC 80.00 yesterday which is far less than my worst day at Kejetia.

Related to this is the inability to meet the daily sales. Most of the operators do not own the three-wheelers and as such they must make daily sales to the owners. However, their ban from the Kejetia area coupled with the decline in access to passengers, and their ability to meet their daily obligations has become a challenge for most of them. An FGD session with the operators reveals (12th September 2023) their predicament in the following narration.

It is now difficult for the operators who work and pay daily sales to owners of the three-wheelers. Because they don’t own the three-wheelers, they must pay an agreed amount of money to the owners daily. The daily sales ranged from GHC 40.00 to GHC 50.00. So, when they make GHC 80.00 it is difficult to meet the obligation because fuel also consumes up to GHC 30.00.

The removal of the three-wheelers from the CBD also places a burden on them because they are struggling to access social amenities such as toilet and washroom facilities at their present location. In the CBD, there are toilets, bathrooms, and other facilities that make working in the area comfortable. However, with the ban, they are now struggling to access these facilities at their present locations. An operator laments their situation 14th September 2023) by stating.

Here, there are no toilets or bathroom facilities. If one is to attend to nature’s call, he struggles because the nearest facility is about 2 kilometres from here and one can imagine the trauma. However, at Kejetia, these facilities are there for everyone to patronise, making it comfortable to operate from there.

Access to repair and maintenance services also emerged as another lost opportunity because of the ban on three-wheelers from operating around the CBD. Repair and maintenance services are available around the CBD and as such it was easy to get to them when the need arose. However, with the ban, the operators are far removed from these services, making it difficult to reach them for their services.

7. Discussion

The operations are organized around scheduled routes, with members joining voluntarily after a basic assessment of their characters and the roadworthiness of their three-wheelers. Members of the various stations are also required to purchase and paste stickers of the station on their three-wheelers for identification. Identification is important because it helps clients locate them in the event of a loss of an item or careless driving. The station executives are responsible for the day-to-day organisation of the station, the operators’ welfare, and the security and safety of their passengers. The welfare of the operators is paramount to the station executives, given that there is no formal arrangement to meet the social security needs of the members as established in previous literature on the actors in informal economies in developing countries such as Ghana (Benjamin et al., Citation2014). The development reduces their social vulnerability. Although the operations of the three-wheelers are not formally organised, they operate an informal self-governing body that comprises executive bodies that oversee the day-to-day affairs of the welfare of members, intervene to resolve challenges, and liaise with city authorities when the need arises. The existence of these self-governing bodies should tell us that the general description of operators in the informal sector as unregistered and operating outside official logics (Benjamin et al., Citation2014, Hart, Citation1973; Schneider, Citation2002) does not preclude them from being integrated into official planning frameworks. This way, the sector can contribute more to local and national development through the numerous employment and income generation opportunities in the sector, and taxes (Benjamin et al., Citation2014; Dell’anno, Citation2022; Petrova, Citation2019). Operators’ adherence to station requirements such as maintenance of roadworthiness of three-wheelers, purchase of stickers to identify themselves, and being of good behaviours should reorient the minds of planners and policymakers about the actors in the sector and encourage us to look at them in a positive light; and fashion out ways to work with and not against them.

The operators like the others in the informal economy face a peculiar situation as their activities appear to be in travesty with the official planning framework in terms of urban infrastructure design. Urban roads and market infrastructure are designed without considering their needs and role in the urban mobility landscape. This places them in a precarious situation and compels them to adopt autonomous processes to create spaces for the conduct of their business. In doing so, they adopt two modes of space creation for their activities. First, the operators auto-produce spaces through negotiation with shop owners in the CBD to use their frontages to conduct their businesses. The approach to space production is not within the official logics of the KMA but between the operators and shop owners. The arrangements with the private businessmen and businesswomen show how the operators exercise agency and creativity to create operational spaces in the CBD which is in line with the views of Caldeira (Citation2017) and Howe (Citation2022) about space creation by urban residents in developing cities. Although the arrangement is informal, they agree with shop owners to adhere to certain conditions to be permitted to operate in such spaces. First, the operators must not block the entrance to the shop by parking directly at the entrance of the shop or dropping off passengers there. Second, the operators must not engage in physical or verbal quarrels with each other or other passengers. Third, only two three-wheelers are permitted to load from the frontage at a time. Finally, they should be ready to vacate the space when the need arises. With this arrangement, it is expected that the actors’ activities will not interfere with orderliness in the city. However, Caldeira (Citation2017) warns that the exercise of such agency on the blindside of official logics usually grows to become a nuisance and subsequently interrupts order-making in busy streets in many developing cities. This may have led to the KMA relying on the Road Traffic Act (Act 683), passed in 2004 to ban three-wheeler operations in the CBD. However, the ban did not go without struggles and resistance from the operators. The ban generated violent demonstrations and confrontations with police and law enforcement agencies in the city, which were widely publicized on mainstream and social media platforms. The posture of the operators following the ban contradicts the position taken by women to cede territorial and spatial autonomy to secure political gains in India by not resorting to protest when an auto-constructed Daycare Centre was demolished (Narayan, Citation2023).

In the second approach, they adopt the ‘operate and wait strategy’ to auto-produce space. When the operators identify an open space, first, they would move in there without formal authorization to conduct their business, as they seek informal agreements with the KMA police to temporarily use it for their business. Often, the spaces occupied by the operators are undeveloped portions, sites of demolished structures, and shoulders of roads. The use of such space in the CBD demonstrates how weak urban spaces are governed. Naturally, the unauthorised occupation, in the long run, generates disorder and creates opportunities for local actors to enhance their influence (and, often, also profit financially) by (re)establishing order outside the official logics (Richmond, Citation2022). Again, the adoption of the ‘operate and wait’ strategy demonstrates the exercise of agency and temporality by the actors not covertly but in anticipation of negotiating with official logics to lay claim to the city, a view expressed by several scholars (Caldeira, Citation2017; Kamath & Kotal, Citation2023; Reis & Lukas, Citation2022) in theorising peripheral urbanisation. However, this approach exposes the operators to unstable conditions of tenure, the skewed presence of the state, precarious infrastructures, exploitation, constant abuse by state institutions, stigmatization, and discrimination, Caldeira (Citation2017) and Porreca and Janoschka (Citation2024) tell us.

In acting from the margins (Caldeira, Citation2017), three-wheelers provide effective, reliable, and affordable transport modes to urbanites that have been confirmed by previous studies across cities in sub-Saharan Africa (Lenshie et al., Citation2022; Obiri-Yeboah et al., Citation2022; Poku-Boansi & Adarkwa, Citation2013; World Bank, Citation2022). However, the activities are prohibited at the usual operation points in the CBD. For this reason, they lose out on the opportunities they previously enjoyed. For example, the ban has limited their access to passengers as most of their clients are those who visit or conduct business in the CBD. Banning them from the CBD implies that they do not have easy and direct access to the clients, which is causing a lot of anxiety and putting pressure on them as they seek to settle daily obligations and make a living. These challenges are not unique to the operators because the informal economic actors often face discrimination, harassment, and exploitation from state institutions without recourse to the consequences of their actions for the livelihoods and well-being of those involved (Sultana et al., Citation2022). The limited access to passengers consequently affected their incomes, undermining their ability to meet their daily obligations to the owners (World Bank, Citation2022). Apart from that, the struggles to meet the out-of-pocket expenses (e.g. fuel, minor and major repairs) in addition to the basic lease compound their problems (World Bank, Citation2022), which may impoverish them. Furthermore, the ban from the CBD has led to limited access to social services such as toilet and washroom facilities as well as repair and maintenance services. These developments add to make their situation more precarious as reported in the work of Doherty et al. (Citation2021) in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. The treatment of such an important segment of the local actors limits their contribution to national and local economic development.

8. Implications of the findings for theory, policy, planning, and practice

The growth of paratransit operations in cities across the country to meet the urban mobility needs of residents has resulted in an increasing demand for infrastructure and services that meet the needs of these modes of urban mobility. This development has implications for the theory, policy, and planning of urban transport infrastructure.

We demonstrate that the exercise of agency by urban residents, albeit temporarily, is not often about the affected persons but the protection of interest of others who are directly affected by their activities.

The organisational structure of the operators provides opportunities for engagement to fashion out how they could be integrated into the urban transport infrastructure so that livelihoods are not negatively affected and at the same time sanity is restored in the CBD.

A successful urban transport infrastructure project design is based on a comprehensive (covers multiple urban transport modes), continual (plans, planning data, and tools are updated regularly), cooperative (all stakeholders develop communications plans and stakeholder analysis), and connected (capital projects are consistent with adopted long-range plans) approach.

Stakeholder engagement through two-way communication is an essential ingredient for the policy, planning, and execution of urban transport infrastructure projects that meet the needs of all modes of commercial transportation. All modes of commercial transport operators’ engagement are key in the implementation of transport infrastructure planning and design.

The demand and use of urban transport infrastructure is growing. As in many other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the planning and design of urban transport infrastructure have not considered the needs of paratransit services although they now play an important role in moving people in and around cities.

Well-maintained and regularly expanded roads also contribute to providing new economic opportunities, by helping urbanites reach their destinations for social and economic purposes, contributing to the local economic development. The benefits of accessibility could translate into a broader socioeconomic development of the country.

9. Conclusions and recommendations

Three-wheeler operations are mostly organised around informal structures that help to manage the day-to-day affairs of the stations in the CBD, with various rules and conditions under which members operate. An organisation of this sort could help to streamline the activities as they are already abiding by rules and regulations that govern their activities in the groups. Through this, the operators can auto-produce spaces for the conduct of their business, with the collaboration of shop owners. The shop owners within the CBD allow them to use their frontages on condition that they do not quarrel, or block entrances to their shops and an agreed number of the three-wheelers are permitted to park at such locations at any given time. They also adopt the operate and wait approach where they identify a space in the CBD and move in while anticipating an informal agreement with officials of KMA. This enabled them to attract passengers and subsequently earned them income. However, the ban on their activities in the CBD has led to the loss of opportunities that came with the operation there. In doing so, the operators now have limited access to passengers which culminates in declining incomes and undermines the ability of the operators to meet their daily lease payment obligations to owners. They also now have limited access to social facilities and repair and maintenance services. Although the three-wheelers are operating outside of official logics, several steps can be taken to integrate them into the local economic and social planning as the way forward. First, the infrastructure design of the road networks and markets should integrate the present and future needs of this mode of public transport since they are here to stay. Second, we recommend that while trying to decongest the CBD, city authorities in Kumasi and others in the Global South should recognise that the new mode of transport is becoming intertwined with urban mobility and should consider providing spaces near the CBD for them to access passengers who patronise their services. Finally, planning for a society without acknowledging the dynamics in its characteristics over time and probable future scenarios is a recipe for failure. Therefore, urban transport policy and planning as well as infrastructure design in Kumasi and other cities in the Global South should be able to respond to the changing demands of the different mobility modes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. trotro are privately owned minibus share taxis that travel fixed routes and leave for their destinations only when filled.

2. At the time of the study, $ 1.00 was equivalent to GHC 13.96.

References

- Abdulai, I. A., Ahmed, A., & Kuusaana, E. D. (2022). Secondary cities under siege: Examining peri-urbanisation and farmer households’ livelihood diversification practices in Ghana. Heliyon, 8(9), e10540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10540

- Abdulai, I. A., Kuusaana, E. D., & Ahmed, A. (2023). Toward sustainable urbanization: Understanding the dynamics of urban sprawl and food (in) security of indigenous households in peri-urban wa, Ghana. Journal of Urban Affairs, 1–25.

- Adams, C., & van Manen, M. A. (2017). Teaching phenomenological research and writing. Qualitative Health Research, 27(6), 780–791. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317698960

- Adomabea, O., Quaye, I., Yeboah, M., & Adarkwa, K. K. (2023). Socio-economic factors contributing to crashes involving motor tricycles in greater Kumasi Metropolitan Area, Ghana. Transportation Research Record, 2677(7), 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/03611981231153655

- African Transport Policy Programme and Republic of Ghana. (2020). Policies for sustainable accessibility and mobility in Urban areas of Ghana. https://www.ssatp.org/sites/ssatp/files/publication/SSATP_UTM_FinalReport_GHANA_1.pdf

- Agheyisi, J. E. (2021). Privileging commuters’ mobility in neighbourhood access: Analysis of tricycle taxi operations in Benin City, Nigeria. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 127, 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.10.004

- Aidoo, E. N., Agyemang, W., Monkah, J. E., & Afukaar, F. K. (2013). Passenger’s satisfaction with public bus transport services in Ghana: A case study of Kumasi–Accra route. Theoretical & Empirical Researches in Urban Management, 8(2), 33–44.

- Bagul, T. R., Kumar, R., & Kumar, R. (2021). Real-world emission and impact of three-wheeler electric auto-rickshaw in India. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(48), 68188–68211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14805-6

- Bamidele, O. (2016). The political economy of tricycle transportation business in Osogbo metropolis: Lessons for a developing economy. Emerging Economy Studies, 2(2), 156–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/2394901516665183

- Benjamin, N., Beegle, K., Recanatini, F., & Santini, M. (2014). Informal economy and the World Bank. World bank policy research working paper, (6888).

- Caldeira, T. P. (2017). Peripheral urbanization: Autoconstruction, transversal logics, and politics in cities of the global south. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 35(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816658479

- Christensen, M. (2017). The empirical-phenomenological research framework: Reflecting on its use. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 7(12), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v7n12p81

- Crisp, R., Waite, D., Green, A., Hughes, C., Lupton, R., MacKinnon, D., & Pike, A. (2023). ‘Beyond GDP’ in cities. Urban Studies, 1, 21.

- Dell’anno, R. (2022). Theories and definitions of the informal economy: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 36(5), 1610–1643. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12487

- Doherty, J., Bamba, V., & Kassi-Djodjo, I. (2021). Multiple mArginality and the emergence of popular transport: ‘Saloni’taxi-tricycles in abidjan, ivory coast. Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography. https://doi.org/10.4000/cybergeo.36017

- Dzisi, E., Obeng, D. A., & Tuffour, Y. A. (2021). Modifying the SERVPERF to assess paratransit minibus taxis trotro in Ghana and the relevance of mobility-as-a-service features to the service. Heliyon, 7(5), e07071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07071

- Ferman, P. R., & Ferman, L. A. (1973). The structural underpinnings of the irregular economy. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 8(1), 1–17.

- Gee, J., Loewenthal, D., & Cayne, J. (2013). Phenomenological research: The case of empirical phenomenological analysis and the possibility of reverie. Counselling Psychology Review, 28(3), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpscpr.2013.28.3.52

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2014). 2010 Population and housing census: District analytical report, Kumasi Metropolitant. Ghana Statistical Servcie.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2021). Ghana 2021 population and housing census general report volume 3A: Population of regions and districts. Ghana Statistical Service.

- Harding, S. E., Badami, M. G., Reynolds, C. C., & Kandlikar, M. (2016). Auto-rickshaws in Indian cities: Public perceptions and operational realities. Transport Policy, 52, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.07.013

- Hart, K. (1973). Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African sSudies, 11(1), 61–89.

- Horn, P., De Carli, B., Habermehl, V., Lombard, M., Roberts, P., & Téllez Contreras, L. F. (2021). Territorios en disputa: Diálogos interdisciplinarios sobre conflicto, Resistencia y alternativa. Lecciones desde América Latina. No. 001. Contested territories working paper series. https://www.contested-territories.net/working-papers-n01/

- Howe, L. B. (2022). Processes of peripheralisation: Toehold and aspirational urbanisation in the GCR. Antipode, 54(6), 1803–1828. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12844