ABSTRACT

The job of designers and business consultants features undeniable commonalities: focus on complex organizational problems, nearly constant exposure to ambiguity, difficulty in measuring performance and need to leverage knowledge and other intangible assets. Synergies between the disciplines of design and business consulting have increased in the last couple of decades. Design Thinking has emerged as an approach to solve business problems by thinking like a designer to leverage creativity and innovation. Despite its success, this has also raised some criticism: a diffused skepticism toward a public relation term that entails expensive invoices to simply apply old-fashioned creative thinking. What do the real protagonists think of Design Thinking and its application in the business world? We explored the perceptions of designers and business consultants on the theory and practice of Design Thinking. We interviewed 11 such professionals and our findings identified significant differences in perceptions around the essence, practicality and value of Design Thinking. Our research supports calls in the literature for establishing stronger connections between the principles of designerly thinking and the practice of Design Thinking in business.

1. Introduction

As a methodology to creatively solve complex problems and foster innovation (Brown, Citation2008; Dell’Era et al., Citation2020), Design Thinking (DT) has in recent years attracted particular interest in consulting firms. After times in which outsourcing of design expertise was widespread (Bruce & Docherty, Citation1993), vertical integration of design functions has become more common. In a series of strategic moves, some of these firms have acquired design agencies and made them their creative arms. Examples include Accenture’s acquisition of London-based service design agency Fjord (Accenture Newsroom, Citation2013), McKinsey’s purchase of design firm Lunar (McKinsey & Company, Citation2015), KPMG Australia’s acquisition of UX, web and mobile development firm Love Agency (KPMG, Citation2019), Deloitte’s purchase of creative agency Brandfirst and EY’s acquisition of strategic design consulting Citizen (Consultancy.uk, Citation2018). Business and management communities have increased their interest in DT as they started dealing with more open-ended, ambiguous, organizational problems, those same problems that designers have been facing for decades (Dorst, Citation2011).

From an ontological perspective, the development of the theory and practice of design has led to the identification of two parallel discourses around design and DT (Johansson‐Sköldberg et al., Citation2013): on the one hand, designerly thinking, enrooted in the academic field of design (e.g., Design Schools and Schools of Arts), which indicates the academic construction of the practice of designers and the theories they mobilize; a discourse that is specific to the design discipline; on the other hand, DT, in which design practice and theory are utilized beyond the design realm, in contexts such as, for example, management, business and social sciences, by individuals that do not necessarily have a design background. In the present research, we use the ‘designerly thinking – DT’ conceptual distinction as our theoretical grounding and we aim at testing its value in practice. We therefore focus on the latter, as an expression of the former, namely as the operationalization of designerly ways of thinking in business consulting.

DT as a way of igniting creativity and fostering confidence in problem-solvers (Tripp, Citation2013) entails drawing inspiration from designerly thinking methods and techniques, without the need for a designer background. DT as a problem-solving approach is therefore attractive to practicing managers willing to solve indeterminate organizational problems and, hence, becomes a milestone also in management education (Dunne & Martin, Citation2006).

The diffusion of DT and design-led methods in the business world has also had some adverse consequences on this approach itself. Award-winning designer Natasha Jen has described DT as a ‘buzzword’ that lacks criticism in conversations by the design community (Jen, Citation2017). Also, Norman appears to criticize the value of DT as a ‘powerful myth’, which serves more as a ‘public relations term for good, old-fashioned creative thinking’ (Norman, Citation2010). Dorst (Citation2011) confirms that DT is often treated as a label to tag disparate, vaguely creative activities, to the point in which, designers themselves, conscious of the true value associated with design activities, would prefer not to use the expression DT at all.

In the present paper, based on the acknowledged absence of an established definition of DT (Dell’Era et al., Citation2020; Goldschmidt & Rodgers, Citation2013), we simply recognize that, among others, there is a lexical issue with it, one that requires further exploration. Moreover, the lack of an agreed definition of DT does not impair our capacity to study it in depth. Our study intends therefore to cast light on its essence, practicality, and value from the perspective of design professionals and business consultants. We aim at addressing an acknowledged gap in the literature around the scarcity of studies on how DT materializes in practice (Carlgren et al., Citation2016). This gap has been confirmed in recent work. Knight et al. (Citation2020), for example, recognized how previous studies primarily concentrated on traditional topics in strategic planning with little attention on what DT could add from a practical standpoint, a view echoed by Micheli et al. (Citation2018), who acknowledged that DT’s strategic significance is only being noticed and acted upon in recent years by many large companies.

In an attempt to demonstrate how DT takes form in practice, we interviewed 11 professionals: half of them have received extensive education in DT and design-led methods (the ‘designers’), whilst the other half has a business and management background (the ‘consultants’). All of them, in their organizations, practice DT as a method to solve organizational problems through creativity. We adhere to Adams, Daly, Mann, and Dall’Alba’s suggestion that DT is ‘what designers understand about design and how they go about the act of designing’ (Adams et al., Citation2011, p. 588). This suggestion allows us to clarify recurring doubts about the fact that DT is not in fact just ‘about thinking’, but also, and mainly, about ‘doing’.

2. Research background

2.1. Design Thinking and design thinkers: ontological issues

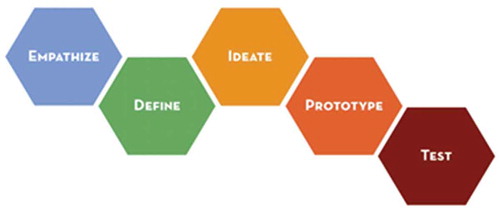

DT has recently emerged as an approach to facilitate innovative problem-solving in public and private organizations alike, with several main goals: from the improvement of services for citizens and other constituencies (service design), through the betterment of products (product design), to the streamlining of existing processes (process design) or customer experiences (UX), the fields of application of DT are potentially endless. Business communities have recently increased their interest in this ‘paradigm for dealing with problems’ (Dorst, Citation2011, p. 521) and, as a management concept, DT can nowadays be interpreted as a way to manage the creative process that leads to innovation (Carlgren et al., Citation2016). illustrates the DT process in one of its formulations.

Figure 1. One version of the DT process (Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford)

Interest for design in business and management disciplines started to emerge as the association between design and innovation (hence, competitiveness) became clearer. From around the 1990s, in what has been dubbed ‘a third wave of change’ (Cooper, Citation2019, p. 11), and together with the emergence of theories such as open innovation and open design, the practice and theory of design experienced a development toward innovation and productivity and, in general, toward addressing industry and economic challenges. This was accompanied by the diffusion of new subdisciplines such as, for example, service design (Cooper, Citation2019; Sun & Runcie, Citation2016). A fourth wave followed, which consolidated the role of design outside its natural milieu: critically, in this phase, researchers and practitioners outside the design realm started using it, emphasizing its value for creative innovation and service improvement (Cooper, Citation2019).

The cognitive model adopted by DT is enrooted in abduction (Kolko, Citation2010; Martin, Citation2009), whereby designers focus on possible states of the world, rather than on existing ones, to expand knowledge on problems and on solutions to such problems. As a pragmatic approach, abduction is the cornerstone of any creative process: after setting an objective, hypotheses are formulated as to how to achieve such objective. Testing of the hypotheses leads to either attaining the intended goal or formulating other hypotheses for further testing (Itō, Citation1996). In DT, the objective is the solution of a complex problem and the creative process starts with the designers formulating hypothetical solutions for such problem. Testing follows, until appropriate solutions are identified. Testing can also be articulated as ‘field experiments’ on actual customers rather than artificial settings. This adds value to outcomes beyond revenue numbers alone, encompassing, for example, value creation, execution, defensibility, and scalability (Liedtka, Citation2015). Cognitively speaking, abduction is therefore the trait-d-union that connects DT and business consulting (Dell’Era et al., Citation2020; Liedtka, Citation2006).

We postulate that designers and business consultants conceive DT as theory and practice in different ways. For now, however, we focus on the role of the design thinkers (being them designers or business consultants), the facilitators in DT projects that act as agents of change. As a paradigm to foster creativity and innovation (Johansson‐Sköldberg et al., Citation2013), DT comes in fact in a structured format that makes it suitable to virtually all organizational problems (Dell’Era et al., Citation2020). What is then the role of design thinkers in DT projects? Liedtka (Citation2020) argues that DT tools, methods, and mind-sets result in far more than tangible outputs that enhance the quality of designs, but more importantly, social and emotional experiences which help overcome psychological barriers that impede dynamic capability building and innovation. This is where the role of design thinkers come into play. As drivers of the change process attached to DT exercises, and facilitators of the DT process, these professionals are often perceived to be third parties who only step into an organization to learn the issue at hand, and then derive a solution to fix that issue. However, as cornerstones of DT, human-centeredness and user-centricity (Heck et al., Citation2018) shift a design thinker’s perceived role from that of a ‘teacher’ (teaching the client organization a new approach to solve problems) to a facilitator, a ‘learner’ (mastering organizational issues and testing solutions until the best one is agreed upon).

Central to the role of design thinkers is the concept of empathy. According to McDonagh and Thomas (Citation2010), design thinkers widen their ‘empathic horizon’ to experience user’s emotions, hopes and fears, in order to generate functional and practical solutions. DT lies in the motivation to solve an organizational or a societal problem in a manner that fits with their vision. It is therefore imperative that a design thinker empathizes with a client in order to feel their problems, rather than observing with a third party’s point of view. Along these lines, Liedtka (Citation2018, p. 73) highlights how DT differs from other problem-solving methods as it concentrates on ‘living the customer’s experience’. A shift in the innovators’ mind-set from that of experts to that of users (through empathy building) enables the convergence of diverse perspectives through dialog-based conversations and leads to clarity about what matters (Liedtka, Citation2020).

Wrigley (Citation2016, p. 149) introduced the concept of ‘transitional developers’ to exemplify the role of these professionals: design thinkers are responsible for translating the language of design research into the context of business and vice versa. McDonagh and Thomas (Citation2010) provide a more rounded function for them, one that stretches beyond the role of transitional developers. In order to effectively empathize with a user, a design thinker must also engage as a collaborator with users, so that both these parties cooperatively develop a coherent understanding of the situation and a more effective solution to the problems at stake (Kummitha, Citation2019).

2.2. The role of the designer

Researchers have investigated the role of designers, in order to understand how these professionals are influenced by their background, studies, past experiences and by the adopted methodology. In their study on DT approaches, Goldschmidt and Rodgers (Citation2013) noticed that designers are progressively more required to have an entrepreneurial spirit, which helps them stay ahead of the harsh competition, by adopting processes that are systematic, but also flexible enough to cater for exploration ‘into unchartered territories’ (p. 468).

In their investigation on how designers experience design across different disciplines, Adams et al. (Citation2011) identified six such ways, including as evidence-based decision-making, organized translation, personal synthesis, intentional progression, directed creative exploration, and freedom. This variety of experiences translates into very different meanings for design, which in turn can result in misaligned project processes and outcomes. Consequently, further investigating the concepts, assumptions and definitions that design professionals attach to their practice is of utmost importance to understand, and manage, the design process itself.

According to Pombo and Tschimmel (Citation2005), the creativity of the design expert generally derives from prior ideas and experiences. As such, a design expert who can distinguish a pattern on previous events or projects underpins their ability to derive solutions for the client. On the contrary, Buchanan (Citation1992) notes how a designer’s prior experience might sometimes act as a class of thinking that restricts potential solutions. Rather than eliciting innovation for a new situation, a designer may mimic previous resolutions. Moreover, this bias may compel the use of these solutions for a new situation and limit the ability of the designer to think outside the box. Liedtka (Citation2015), in echoing the views of Buchanan (Citation1992), asserts how DT practices improve innovation outcomes by mitigating obvious cognitive flaws whereby ‘humans often project their own world view onto others, limit the options considered, and ignore disconfirming data’ (p. 937). New sub-disciplines have emerged as a result, among which is speculative design, the exploration of solutions for the future, without pre-conceptions from the past and the present (Auger, Citation2013).

Chisholm claims that crucial to the success of innovations produced through design-led methods, is the designer’s ability to ‘interpret, understand and influence how people give meaning to things’ (Chisholm, Citation2015). A designer’s capacity to produce innovative solutions for a client organization would be inhibited by prior prejudices and limited consideration of the vision of the client organization. Eventually, the success of this method lies in the designer’s ability to adjust the innovation to one that is appropriate to the distinctive cultural context of the new situation (Brown & Wyatt, Citation2010).

Extensive research has also been dedicated to singling out the different characteristics and ways of working typical of designers. Owen (Citation2007), for example, has identified the following qualities in a designer: conditioned inventiveness (creativity toward invention), human-centered focus (client-orientation), environment-centered concern (environmental interests as a constraint), ability to visualize, tempered optimism, bias for adaptivity (taste for adaptive products and services to fit users’ needs), predisposition toward multifunctionality, systemic vision (a holistic approach), view of the generalist, ability to use language as a tool, affinity for teamwork, facility for avoiding the necessity of choice (leaving decisions to decision-makers), self-governing practicality, and ability to work systematically with qualitative information. Dorst (Citation2011) argues that the most experienced designers understand the importance of framing by not addressing complex paradoxes underlying problems to be solved headfirst but focus instead on issues surrounding them. In this way, they facilitate the emergence of new frames for problem-solving, with which the central paradox can then be tackled.

In order to better elicit the role of designers in organizational problem-solving, our research investigates how professionals with a background in design see their role, and compares and contrasts this with the same perceptions by professionals who practice design for consulting, but do not have design education. The following sub-section concludes our review of the relevant literature by analyzing several studies on the usage of DT in consulting projects.

2.3. Design Thinking in business consulting

Just like business consulting, the design profession is centered around personal relationships, personal chemistry, mutual trust and respect and understanding. For design to become in modern organizations an influential perspective, with a strategic value, consistency in ‘pragmatic and moral arguments’ is key to engrain design in an organization’s fabric, without taking for granted its contributions to value creation (Micheli et al., Citation2018). Similarities between the job of a designer and that of a business consultant are evident. From external consultants invited into a large organization to inspire employees on the value of design-led methods (Rauth et al., Citation2014) to the role of design consultants within SMEs (Ford & Terris, Citation2017; Nunes, Citation2015), this similarity has evolved toward the unfolding of progressively more strategic roles for designers within client companies (Bruce & Docherty, Citation1993).

The potential for a strategic role by DT is emphasized also by Knight et al. (Citation2020), who refer to several world-leading strategic consulting firms (e.g., Boston Consulting Group, McKinsey & Company, Bain & Company, etc.) as examples of firms that have recognized the value of including DT as an organizational function, into their strategic offering. Seidel (Citation2000) has investigated how consultants that practice DT participate in strategic planning and identified four potential roles: as strategy visualizers, designers can visually shape a company’s strategy in physical artifacts giving clarity to what that company’s future strategic directions would look like; as core competence prospectors, designers can identify internal resources and capabilities that a firm can strategically exploit; as market exploiters, design consultants can look at what market positioning would best benefit the company; and, finally, as design process providers, designers can provide expertise in implementing processes intended to manage design and associated business strategy. Interestingly, the author found that the impact produced by most of the designers involved in his study materialized at the functional-level and business-level strategies: that is to say, where decisions have to be made as for functional resource allocation (the former) and where competition involves individual business units (the latter).

In their recent study on how consulting organizations practice different interpretations of the DT paradigm, Dell’Era et al. (Citation2020) reviewed work done by 47 such organizations (design studios, digital agencies, strategic consultants, and technology developers) in Italy. This investigation has led to the identification of four kinds of DT, namely: creative problem solving (solution of wicked problems through analytical and intuitive thinking); sprint execution (delivery and testing of viable products to learn from customers and improve solutions); creative confidence (increasing stakeholders’ confidence in creative processes); and innovation of meaning (re-shaping the meaning that users attach to experiences). The core actors in these four kinds of DT differ: naïve mind people foster creative problem solving; experts lead sprint execution; key stakeholders promote and develop creative confidence; and interpreters unlock innovation of meaning. In the footpath of the study by Dell’Era et al. (Citation2020), which significantly casts light on the different nuances that DT encompasses in consulting organizations, the present investigation unpacks the perceptions that designers and consultants, respectively, have around DT, vis-à-vis one major contextual factor, their background as designers or business consultants. This is an acknowledged gap in the literature (Dell’Era et al., Citation2020).

Designers and consultants generally start their careers as technical specialists with functional expertise. As a result, they must be able to fully participate in cross-functional teams, whilst being aware of commercial considerations typically attached to their work practices (Micheli et al., Citation2018). In their study on the involvement of consultant designers in New Product Development (NPD), Maciver and O’Driscoll (Citation2010) found out that designers’ remit in NPD is broadening toward the more authoritative role of planning opportunities for clients and providing more ample suggestions around not only the final product specifications, but also new market opportunities and a greater scope for involvement. The researchers also emphasized how designers were taking the lead on NPD projects, in which they were involved early and extensively, and not simply as executors of clients’ instructions. These findings are consistent with Owen’s characteristics and ways of working of modern designers, predisposition toward multifunctionality, systemic vision, view of the generalist, affinity for teamwork, and facility for avoiding the necessity of choice (Owen, Citation2007).

The affinity between DT and consulting is acknowledged in several academic articles (Bruce & Docherty, Citation1993; Cooper, Citation2019; Johansson‐Sköldberg et al., Citation2013; Owen, Citation2007), which emphasize the power of creativity and innovativeness in the business world. Rylander (Citation2009, p. 11) has brilliantly synthesized these similarities aggregating them around a common challenge: ‘highly qualified people engaging in creative problem solving’. The area at the intersection between DT and strategic management has been defined ‘design-led strategy’ (Knight et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the diffusion of DT in business consulting and a growing academic interest in the role of consultants as advisors in creativity and innovation processes are not a surprise (Wrigley, Citation2017). However, without more solid groundings in designerly thinking (that is to say, with the theory and practice of design as originally conceived by designers), there is a risk for DT to quickly become just another approach proposed by consultants, valid and appreciated until another, more attractive perspective, replaces it (Johansson‐Sköldberg et al., Citation2013).

We will not delve extensively into the criticism that DT and design-led methods have stimulated, especially in the last two decades, but a brief mention of the key elements of such criticism, and some counterarguments, are necessary. An interesting overview on this topic is offered by Iskander (Citation2018) who basically argues that, counterintuitively, DT is indeed conservative and bound to preserve the status quo. Among its limitations, the author lists its lack of definitions; its weak evidence-base; its similarity to basic commonsense; and the hefty price tags often associated with it by consulting companies. On a similar note, world renowned designer Natasha Jen has defined it ‘bullsh*t’ (Jen, Citation2017), equally pointing her finger at some of its practices, opportunistically drawn from fields typical of ‘canonical’ design disciplines such as industrial design. Jen has also criticized the concept of DT as a diagram, a process that can be easily replicated, but that does clarify what its end goals are.

Countering these arguments is outside the scope of our study, but we can nonetheless offer some ideas around the reasons for such criticism. It is hard not to notice how, in her article, Iskander has idealized the figure of the designer as a ‘gatekeeper for innovation’, one that filters all creative efforts in an attempt of preserving the status quo. Our experience in design-led projects suggests that this view is at best skewed: we rarely took part in design projects in which the designer did not act as a mere facilitator of the creative process, an individual whose presence is certainly not attached to a gatekeeping function. To push things further, we could argue that, like during a football match the referee, a good indication of a designers’ skills resides in their ability to ‘disappear’ from the picture and simply steer the creative process with little touches here and there. The co-creation process is the real ‘star’ of the show, not the designer. Iskander also mentions the concept of interactive engagement as a better approach than DT in stimulating ‘changes that we cannot yet imagine’. Again, one has to wonder what types of DT projects the author has been exposed to, as the co-creation of innovative solutions through engaged interactivity among various stakeholders (end-users, design facilitators, project managers, etc.) is typical of DT. Similarly, we could hypothesize that Natasha Jen’s remark around the emptiness of DT could derive from two elements: the first one, objective, is the lack of agreed definitions from which DT undeniably suffers (Johansson‐Sköldberg et al., Citation2013); the second one, possibly subjective, is the author’s background as a ‘pure’ designer. During a recent conversation with a designer educated in a School of Art in the UK, at the successful design agency that she founded, our reference to DT was welcomed with some criticism. In particular, the designer pointed out that, in her agency, they did not ‘think’ but ‘created’ products, processes, and services. Although anecdotical, this example serves to illustrate the tension that seems to characterize the already mentioned relationship between designerly thinking and DT (Johansson‐Sköldberg et al., Citation2013).

Regardless of which position one may take, perceptions around DT and its success cause very different reactions in professionals in the field. For this purpose, the present research aims at casting light on views around DT, its usefulness and potential for the creation of value by professionals who practice it daily. The next section reviews the research methods adopted in the present investigation.

3. Research methods

This research is constructivist, in that it is enrooted in the belief that social reality is constructed by its actors (Costantino, Citation2008). As such, the interaction and dialog between the researchers and the participants underpin the development of new knowledge with regard to the explored phenomenon (their perceptions vis-à-vis DT). We adopted a qualitative approach and selected semi-structured interviews as the data collection method to tease out distinctive patterns and processes to create meanings of DT as a social phenomenon. Semi-structured interviews are a common method in phenomenographic design studies, as they enable researchers to gauge rich, reflective and context-specific data around participants’ experiences and meanings associated with such experiences (Adams et al., Citation2011).

Participants were selected by means of a purposeful sampling strategy (Marshall & Rossman, Citation2011). Quality of the research sample was ensured by selecting participants who had sufficient knowledge of DT and applied it in their line of work for at least 5 years. The 11 participants were divided in designers (6), who had a background, in terms of both education and prior professional experiences, in DT and design-driven methods; and consultantsFootnote1 (5), who had backgrounds in areas different from design (in business disciplines, such as accounting, risk management, innovation and technology management), but had daily experience with adopting DT in their profession. This distinction represents the designerly thinking vs. DT taxonomy, where the former refers to professionals educated and trained in typical design disciplines (e.g., industrial design, service design, product design, etc.) and the latter to professionals with different backgrounds, but who had a chance to learn DT by practicing it through the mediation of a role in business consulting (Johansson‐Sköldberg et al., Citation2013). This constitutes the epistemological grounding of our study: ascertaining perceptions around DT’s nature, and practice from these two categories of participants allowed us to cater for the current debate about the value of DT.

The sample, with its two categories of participants, was selected for two reasons. First, we needed professionals who had practiced DT for a sufficient time, to be able to report on their experience and perceptions around this approach. Second, to account for potentially contrasting viewpoints, we needed to have equal representation of professionals with a design background and with other backgrounds. This allowed us to control for potentially biased perceptions around the usefulness and suitability of DT is consulting-like roles. illustrates the research sample adopted in our study.

Table 1. Research sample

Participants in our sample were selected across four countries as a control for bias potentially deriving from their education and training with DT and design-led methods. Anticipating on our findings, we noted that country of origin did not appear to influence their answers. Interviews were not recorded, but detailed notes were taken by the researchers during the interviews, at the end of which, responses were revised to ensure no relevant information was omitted. Interviews lasted between 33 and 56 minutes.

Abductive reasoning (Timmermans & Tavory, Citation2012) was employed to perform analysis of the interview materials. This allowed the researchers to investigate participants’ viewpoints on the topics, based on their experience and their personal stances. The researchers carried out content analysis by, first, carefully reading the notes from the interviews to identify critical themes and categorize them and, second, by closely examining cases of misalignment, which were then discussed and solved. This allowed researchers to avoid interpretive bias (Marshall & Rossman, Citation2011). For an overview of the interview questions, please see Appendix 1. The following section presents the findings emerged from our semi-structured interviews.

4. Findings

Data showed that our interviewees were able to tap into a significant reservoir of experience (and expertise) in DT. Responses were based on a mix of prior design-led consulting experiences, individual projects delivered to clients, but also educational background, integrative readings and studies. Our interviewees typically work with clients ranging from start-up companies to large multinational corporations, as well as government bodies and NGOs. This provided a high degree of richness in the collected data. Based on interview responses, the researchers identified three main emerging themes: definition, practicality, and value of DT. To explore commonalities and similarities between the viewpoints of designers and consultants, each theme is divided in two parts.

4.1. Definition of Design Thinking

Opinions differed as to how DT was implemented and executed in the context of a real-client problem. The designers explained DT in terms of the thinking process behind the use of the concept, whilst the consultants seemed to explain DT more in terms of a methodology to be followed.

4.1.1. Definition of Design Thinking: the perspective of designers

Most designers agreed that DT is effective as a human-centered approach to both solve existing problems and discover untapped opportunities. In numerous instances, designers also found DT to be a targeted way of discovering what their client’s needs and wants were, regardless of type (e.g., public vs private) and size (e.g., start-up vs incumbent). Human-centeredness was also described as an enabler to systematically unearth the root cause of problems and reframe them into a single, pertinent, eye-opening narrative for the clients. One designer, however, provided a more skeptical definition. This was particularly interesting given that this participant, who had formal training in design, highlighted how DT has become an elusive marketing term which leaves clients with idealistic expectations:

‘I don’t know what DT means anymore. It seems to be an evolution of a term in the industry into a mere craft that links managers and makers of an organization’ (Participant F).

This participant frustratingly criticized the current hype surrounding DT, which has made it almost ‘a fad’. The main concern expressed about this issue was that users of DT only seem to ‘pay lip service’ to it, having altered its meaning into an intuitive problem-solving method, to be coupled with a few principles extracted from other disciplines.

4.1.2. Definition of Design Thinking: the perspective of consultants

Like the designers, two consultants also emphasized the human-centeredness of DT, and the relevance that the human factor has in it, as a process:

‘You can call DT a human-centered or user-centered or even a user-focused approach to enable design’ (Participant 1).

However, most of the consultants explained DT in terms of a targeted methodology. They explained that DT assists businesses in better identifying, understanding and addressing their problems. This holds true, however, only if each step of the process is followed:

‘DT is going out to find actual targeted customer needs, and then analyzing their needs and wants to realize a best offering that meets those needs and wants’ (Participant 4).

Unlike the designers, who explained DT in terms of the thinking process, the consultants seemed to feel that the methods of DT, including its different tools, enabled them to identify the client’s exact problem. One participant quoted the famous Henry Ford maximFootnote2 to exemplify how, in DT, user research moves beyond asking clients what they want. Discussions around the definition of DT quickly led respondents to elicit their views on the different phases in which the DT approach is usually described. One interviewee noted that adherence to the different steps of DT would facilitate discovery of the root causes of a problem, ideation of possible solutions, prototyping, and finally testing solutions to select the most viable one.

‘DT is an interesting and beneficial process. However, the client must be made aware of the constant iterations involved in the DT process. The client must be able to deal with this method from the start’ (Participant 5).

Another consultant, however, expanded the methodological aspect of DT by emphasizing that the use of DT is largely dependent on the client’s need. The DT process should be adapted according to such need, and some steps can at times be omitted:

‘The use of DT always depends on the client’s need. You don’t necessarily go through all steps in the DT process for every situation’ (Participant 1).

Collected data highlighted how for several consultants the degree to which the methodology matches the client organization’s requirements necessitates careful preliminary consideration, before embarking on a DT project.

4.2. Practicality of Design Thinking

The second theme that emerged from the interviews relates to the practicality of DT (i.e., the effectiveness of DT in tangibly achieving intended objectives). All participants were unanimous in the view that, at the start of the process, empathy sessions are an effective technique to deeply probe the ‘whats’ and ‘whys’ of a given situation/problem presented by clients. This was reported to be one of the key phases of the DT process, one permeated by practical value, as acknowledged in the business world, beyond mere theoretical speculation:

‘Since people like to have their voices, thoughts and opinions heard, the Empathize phase was often a success because it gave raw and blunt insights into the daily challenges and dilemmas of staff or end-users’ (Participant 1).

Thus, empathy sessions with all levels of staff provided the participants with a complete view of the culture, attitude and problems within the client organization. With a deep understanding of both top-down and bottom-up perspectives, participants were not only able to systematically locate areas for change but were also able to identify untouched opportunities that could possibly give their clients competitive advantage.

‘DT is not a reductionist approach to thinking, but one that focuses on a creative and inductive understanding of a problem in its wider context. It is in fact a more holistic point of view, rather than a reductionist point of view’ (Participant B).

4.2.1. Practicality of Design Thinking: the perspective of designers

Designers appeared to be more optimistic about the use and acceptability of design-led methods for consulting. They suggested that their use of DT in a client-problem context was because the use of DT was driven by their employer’s organizational culture. When asked to justify why this was the case with design firms, the designers noted that it was because their employers primarily seek client organizations that have embraced the power of creativity in their businesses:

‘My organization pushes us to DT in solving all client issues. In fact, it is a culture applied within my organization. We don’t only practice what we preach, but we also teach DT to our clients as we believe in the benefits it brings’ (Participant C).

Interestingly, designers said that although DT was used in all projects, the term Design Thinking was not always explicitly mentioned. While discussing the application of DT, Participant B highlighted the role that endorsement of design principles by government organizations can play in driving a design-led organizational culture:

‘The adoption of DT principles in the UK government’s Service Standard demonstrates that the UK community is cognizant of the value that design-led methods bring to the business world.’ (Participant B).

Other perspectives introduced by designers included the fact that the practicality of DT is heightened by its acceptance by clients. Several designers argued that the influence by senior management to allow a ‘design mind-set’ to trickle down through to the rest of the organization is central to effective application and practicality of DT:

‘It is important that the client’s management influences others to think in a design way and coaches a change of culture’ (Participant A).

Participant F partially challenged this view, noting that it is also the designer’s responsibility to create an environment that proves the practicality of DT:

‘Clients do not always know what would be the right thing to do, what changes to make […] we as designers step in with an open mind, take time to explore, learn and understand the client’s situational context, and only then, we respond to their need.’ (Participant F).

Some designers also argued that the practicality of DT in deriving viable solutions for clients is particularly enhanced when collaborative efforts are involved. They explained that in a technology-rich world and in a business landscape that is constantly evolving, the application of DT through collaboration with various groups of stakeholders enables a better understanding of their needs.

4.2.2. Practicality of Design Thinking: the perspective of consultants

Unlike designers, who felt that DT is relevant for business issues with high complexity, responses from consultants suggested that there seemed to be certain variables in the client scenario that influenced the adoption of DT, one being a priority and appetite for developing products and services. Others acknowledged that, at times, the use of DT in a project is strongly encouraged by their employer, to the point in which it is almost always recommended to clients during a pitch. However, the decision to ultimately adopt DT depends on client’s need:

‘My organization’s culture is slightly different than the rest. We are selective in the kinds of projects that we take on. We choose projects where the client agrees to use DT and ones that make significant contributions or developments to Scotland’ (Participant 1).

Interestingly, one consultant argued that the concept of DT is naturally encapsulated in the way in which people generally approach problem-solving. This participant explained how the specific phases of DT are often practiced within organizations, without calling it DT. Although DT is believed to be an effective problem-solving method, its tools and techniques are used with much caution. DT is adopted only when a client is willing to accept that, despite rigorous testing (which requires investments), not all solutions are implemented.

‘DT works for clients whose risk tolerance is higher […] the concept does not sit with large, old-school organizations who can’t afford to test and fail with DT because in these organizations, everything that you show the Board of Directors must reflect in dollars and cents.’ (Participant 5).

In resistant organizations, clients would expect the consultant to provide the solution based on their own analysis, instead of co-designing. Surprisingly, all consultants who reported this problem further emphasized the benefits of applying DT in consulting. Data revealed that consultants attributed sub-optimal DT acceptance to the skewed and somehow naïf understanding of its principles and value by the clients.

4.3. Value of Design Thinking

The third theme related to the value that designers and consultants place on DT and its effectiveness when conducting their consulting projects. In this respect, both parties seemed to agree on one key strength and one key weakness of this approach. As for the former, respondents generally agreed that DT provides designers/consultants and clients with the tools and context to investigate the potential root causes of problems at play:

‘The DT process is fantastic at allowing you to look at a problem in its context, and through that, finding the root cause of an issue’ (Participant D).

Several respondents agreed that often clients misinterpret the nature of their problems and fail in understanding the bigger issues at stake. This is primarily where the value of DT emerges through problem framing and reframing and building a single, clear narrative that is relevant and eye-opening for clients.

‘When we have a conversation with a client, I try to probe on what they think is successful, understand the limits and edges of the work, and then have a more defined scope. So we know what we want to achieve, but we’ll go through the process of exploring and then decide what to do - DT allows this’ (Participant F).

As for the weakness, all participants agreed that the value of DT is curtailed by several external variables that are not easily addressable under traditional business contexts. These, according to the participants, include the client organization maturity, the effectiveness of their change management processes, and the presence of incentives to motivate user involvement in the DT process.

4.3.1. Value of Design Thinking: the perspective of designers

Interestingly, some designers felt that part of the value of DT resides in its link to the formulation of strategy for clients. Data show that when various organizational departments work together, ideas can freely overlap and management can channel the intellectual capital in the organization, as seen in the following passage:

‘As different silos and departments in an organization breakdown and begin working together, this helps inform the strategy formulation for the client’ (Participant C).

DT can aid strategy formulation by helping narrow down the various strategic options, gain information on the best one, to then formulate a strategy:

‘An effective strategy should be simple and short. So out of 100 options, a client may pick the top 2. This is where DT is seen to enable the investigation of the strategy landscape’ (Participant E).

Designers also underlined the issue that emerges when identified problems cause frustrations in clients and their managers (for example, problems on which management prefers to procrastinate). This often results in discouragement and disengagement:

‘I have noticed that when Empathy sessions reveal issues that the client does not want to acknowledge, they are often discouraged to continue using DT to solve their problems’ (Participant C).

4.3.2. Value of Design Thinking: the perspective of consultants

The consultants shared that the goals of DT activities are best accomplished when clients are prompted to tell their stories. This in fact enables participants to extract meaning from the stories and ‘connect the dots’:

‘Clients may not always see a solution, but the designer may see it. Thus, the designer can frame a problem according to the client’s strategic needs and use different approaches at different times to meet the client’s needs’ (Participant 1).

Consultants expressed their concerns that, in a DT project, several factors could distract clients from the effective implementation of each stage of the DT process. At times, due to the flexibility and freedom that comes with the usage of DT, clients expect more areas to be addressed by the consultant. This makes agreeing on the scope of projects a particularly problematic task. Additionally, some consultants highlighted that over-emphasizing a phase of the process often pushes clients to stall on that same phase. This is commonly noted during empathy sessions, when clients could become overly focused on complaining and struggle to move into ideating solutions:

‘Clients may lose sight of the actual problem if we as consultants over-empathize.’ (Participant 4).

provides a synthetic overview of the three main themes emerged during the interviews, grouped by designers’ and consultants’ perspectives, with notable variations on the general findings.

Table 2. Themes emerging from the collected data

5. Discussion

5.1. Design Thinking as seen by designers and consultants

As Porcini (Citation2009) states, central to the successful application of DT in consulting is the ability of the designer/consultant to dialog with every level of the client company and adapt their language to be understood by various internal target audiences. This position aligns with the creative confidence kind of DT (Dell’Era et al., Citation2020). Our research confirms this as, regardless of their background, our participants almost unanimously agreed that the Empathize phase of DT is crucial in the whole process. It in fact provides a holistic view of the organizational problems and facilitates rich conversations among oft-siloed teams through an understanding of the skills and values each team offers. Overall, the findings from our research enrich our understanding of the Empathize phase of the DT process in two directions: 1) Empathy sessions need carefully crafted execution; 2) Since the innovative solution comes as a result of a collaborative effort, the client buy-in is dependent on the empathic relationship that the designer/consultant develops from the beginning of the project.

Our data revealed that the relationship between DT as an approach and the activity of business consulting is not always a straightforward one, mainly due to two orders of problems: first, DT suffers from some intrinsic language issues (e.g., lack of agreed definitions; improper usage of design terminology by non-designers; consumerization of DT language; etc.); second, its understanding by non-designers can be, at best, incomplete. These two issues relate to the difference between designerly thinking and Design Thinking, and in particular to the two first origins of the latter: on the one hand, DT as a way of working with design and innovation; on the other hand, DT as a problem-solving approach to tackle complex organizational problems (Johansson‐Sköldberg et al., Citation2013). Interestingly, our research demonstrates that, while the interviewed designers seemed to aggregate more around the first origin, the consultants’ words seemed closer to the second origin. The designers, who were trained to designerly thinking but also have significant experience in offering their advice to business clients (i.e., consulting) represent the meeting point between the need to practice design according to its theory and discipline and the need of businesses to find innovative problem-solving approaches. The consultants represent the very last portion of this turning point: trained in areas other than design, they mainly represent the need to facilitate the production of innovative solutions for their clients, and they do so by adopting DT. In this sense, they seem to have a more instrumental approach to DT, one that seem to best align with the creative problem solving and sprint execution kinds of DT (Dell’Era et al., Citation2020).

Our research also confirmed that, in our sample, the designers were the ones more prone to establish a connection between the practice of DT and organizational strategies. This seems to confirm literature that suggests designers’ proneness to be more involved in higher-level decision-making, even around strategy conceptualization (Bruce & Docherty, Citation1993), an area that we recommend for further investigation. Defined as innovation driven by users’ needs, technological affordances and a firm’s vision about the potential for new product meanings and languages, design-driven innovation (Verganti, Citation2009) represents the trait d’union between design and strategy. The designers we interviewed reinforced the value of DT in redesigning value propositions and therefore potentially changing the meaning that organizations attribute to their product and services (Verganti, Citation2009). This seems to best align with the innovation of meaning kind of DT (Dell’Era et al., Citation2020), which can be defined as the most strategic kind, given its potential to produce competitive advantage for organizations that master it.

A caveat was raised, to different degrees, by all our participants: to be effectively applied, DT requires to be endorsed by the appropriate organizational mind-set or culture. This mind-set, when not naturally engrained in an organization, can at least be promoted through training and ‘learning by doing’.

5.2. Language issues and the role of designers

As we discussed in our literature review, several critics have vigorously challenged the value of DT, claiming it to be a business hype (Jen, Citation2017). Lack of agreed definitions and somehow elusive concepts contribute to the incomplete understanding that, designers and non-designers, have of DT’s dynamics. Resistance is therefore increased through misunderstanding.

Our findings support this view, as both designers and consultants in our sample acknowledged that mismatching definitions and a lack of common grounding on the more ontological aspects of DT (e.g., is it more a culture or a methodology?) can lead to misunderstandings and inaccurate usage of words. Designers, by virtue of their background, seemed particularly keen on considering DT as a set of principles, more than a succession of steps. As a result, their focus is strong on the role of the designer, as an individual that manages to impersonate those principles (or traits, which include, among other, empathy, creativity, holistic approach to problems, etc.).

On the other hand, the consultants appeared more focused on understanding their clients’ needs and adapt their method accordingly. We can conclude that the designers in our sample featured an introspective approach to DT, one that justifies the usage of the word thinking to describe their perspective. The consultants, on the contrary, showed an extrospective (i.e., outward-looking) viewpoint, one for which usage of the word thinking may not be completely appropriate. We argue that this could explain why, especially in the consulting environment, the concept of DT is at times met with skepticism and resistance (Norman, Citation2010; Woudhuysen, Citation2011), feelings that can be corroborated by clients’ attitude.

If we were to single out one feature that our data showed as being most relevant in a designer, this would be, unsurprisingly, a human-centered focus. Despite the evolution that DT has experienced across these last decades, the focus on humans and what really matters for them is, still, a key component of DT as a culture, a method, and a process (Brown, Citation2008). In this sense, our study confirms the undeniable value that DT can bring to business consulting, a field in which, often, technologies and budgets are the key drivers to innovation. We welcome the recommendation by Johansson‐Sköldberg et al. (Citation2013) on complementing DT with theoretical and practical groundings derived from designerly thinking: without this incorporation, the risk of having DT portrayed as just another ‘fancy’ approach that consultants ‘sell’ to their clients is real.

5.3. Research contributions, limitations and areas for future investigation

Several practical contributions emerge from this research. First, since the language of DT suffers from an acknowledged vagueness, especially in consulting, we recommend firms that intend to offer DT to preliminarily raise awareness on it. This can be done through training and requires endorsement by senior management in the client organization. Clients who are inexperienced in DT could be initially involved in standalone, bite-sized DT projects as a taster of the approach. A focus on the creative confidence kind of DT could be, in this direction, particularly fruitful (Dell’Era et al., Citation2020). Interesting synergies can also be created between designers and consultants. In order to strengthen the designerly thinking in Design Thinking (Johansson‐Sköldberg et al., Citation2013), we urge in particular designers to take advantage of their roles as ‘transitional developers’ (Wrigley, Citation2016) and educate consultants on how to effectively translate the language of design research into the context of business, in an easily consumable way.

From a theoretical perspective, our research demonstrates an excessive emphasis on the concept of DT as a step-by-step methodology, which has led, among others, to the proliferation of ‘how to DT’ playbooks and courses. We argue that, while the focus on the methodology is necessary to demonstrate the validity of this approach, more efforts must be put toward further understanding the principles governing designerly thinking as the theoretical foundation of Design Thinking. To do so, we believe in the direction taken by several scholars; exploring key principles guiding the practice of design (Owen, Citation2007; Wrigley, Citation2016) and addressing questions such as what makes a good designer?, how do we shape a design-led organization?, etc.

The present research has several limitations. First, the bounded scope of investigation, with a relatively small sample of participants from two professional categories, limits the generalizability of our findings. Second, the countries of our participants may significantly differ in terms of diffusion and understanding of DT practices. Moreover, the presence of three Anglo-Saxon contexts and one Asian may skew our findings. Further research is recommended, with a more homogeneous sample. Third, our semi-structured interviews allowed us to investigate a broad range of topics, without catering for depth. We suggest other researchers to couple qualitative research methods with quantitative ones (e.g., surveys and questionnaires), in order to expand scope of investigation, as suggested in work on similar topics (Dell’Era et al., Citation2020).

6. Conclusion

This research presented a comprehensive study on definitions, practicality and value of DT from the perspective of designers and business consultants. Our study followed recommendations by Dell’Era et al. (Citation2020) on the need for research that examines contextual factors in influencing DT practices, by focusing on the background of the design thinkers. Our data determined that DT does not only serve as a method to solve organizational problems through creativity but can also yield innovations possibly leading to strategic changes within the same organizations. Both designers and consultants were unanimous in stressing the human-centric aspect in the DT process and the importance of the Empathize phase. Intrinsic language issues (e.g., lack of agreed definitions; consumerization) emerged, which were found to be possibly conducive of lack of confidence among clients in the practicality and value of DT to their organizations. Our study also underlines the existence of an introspective approach to DT (the thinking behind the use of DT), typical of professionals with a designerly thinking background; and an extrospective perspective (DT as a series of steps), typical of consultants. In our paper, we have addressed the ambiguity surrounding DT as a step-by-step methodology, which, according to our interviewees, has led to down watering the foundations of designerly thinking.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The term ‘consultants’ should be here considered in its broader sense, referring to business professionals providing managerial advice to external companies, but also senior managers in a position to tackle strategic organizational problems through DT and, in general, DT brokers without a DT background.

2. ‘If I asked people what they wanted, they would say faster horses.’

References

- Accenture Newsroom. (2013). Accenture completes acquisition of Fjord, expanding digital and marketing capabilities. https://newsroom.accenture.com/industries/communications/accenture-completes-acquisition-of-fjord-expanding-digital-and-marketing-capabilities.htm

- Adams, R. S., Daly, S. R., Mann, L. M., & Dall’Alba, G. (2011). Being a professional: Three lenses into design thinking, acting, and being. Design Studies, 32(6), 588–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.004

- Auger, J. (2013). Speculative design: Crafting the speculation. Digital Creativity: Design Fictions, 24(1), 11–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2013.767276

- Brown, T. (2008). Design Thinking. Harvard Business Review, 86(6), 84–92.

- Brown, T., & Wyatt, J. (2010). Design Thinking for social innovation. Development Outreach, 12(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1596/1020-797X_12_1_29

- Bruce, M., & Docherty, C. (1993). It’s all in a relationship: A comparative study of client-design consultant relationships. Design Studies, 14(4), 402–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-694X(93)80015-5

- Buchanan, R. (1992). Wicked problems in Design Thinking. Design Issues, 8(2), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511637

- Carlgren, L., Rauth, I., & Elmquist, M. (2016). Framing Design Thinking: The concept in idea and enactment. Creativity and Innovation Management, 25(1), 38–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12153

- Chisholm, J. (2015). What is design-driven innovation. http://designforeurope.eu/what-design-driven-innovation

- Consultancy.uk. (2018). Deloitte and EY acquire design agencies Brandfirst and Citizen. https://www.consultancy.uk/news/15831/deloitte-and-ey-acquire-design-agencies-brandfirst-and-citizen

- Cooper, R. (2019). Design research – Its 50-year transformation. Design Studies, 65, 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2019.10.002

- Costantino, T. E. (2008). Constructivism. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods (pp. 117–121). Sage Publications.

- Dell’Era, C., Magistretti, S., Cautela, C., Verganti, R., & Zurlo, F. (2020). Four kinds of Design Thinking: From ideating to making, engaging, and criticizing. Creativity and Innovation Management, 29(2), 324–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12353

- Dorst, K. (2011). The core of ‘design thinking’ and its application. Design Studies, 32(6), 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.006

- Dunne, D., & Martin, R. (2006). Design Thinking and how it will change management education: An interview and discussion. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 5(4), 512–523. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2006.23473212

- Ford, P., & Terris, D. (2017). An intimate approach to the management and integration of design knowledge for small firms. Design Management Journal, 12(1), 58–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmj.12036

- Goldschmidt, G., & Rodgers, P. A. (2013). The Design Thinking approaches of three different groups of designers based on self-reports. Design Studies, 34(4), 454–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2013.01.004

- Heck, J., Rittiner, F., Meboldt, M., & Steinert, M. (2018). Promoting user-centricity in short-term ideation workshops. International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation, 6(3–4), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2018.1448722

- Iskander, N. (2018). Design thinking is fundamentally conservative and preserves the status quo. In Harvard Business Review (Vol. 5). Harvard Business Publishing. https://hbr.org/2018/09/design-thinking-is-fundamentally-conservative-and-preserves-the-status-quo#

- Itō, T. (1996). A New Approach to Future Enterprises: Abduction for Creativity. Ohmsha.

- Jen, N. (2017). Design Thinking Is Bullsh*t: 99U Conference. In. New York: Adobe

- Johansson‐Sköldberg, U., Woodilla, J., & Çetinkaya, M. (2013). Design Thinking: Past, present and possible futures. Creativity and Innovation Management, 22(2), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12023

- Knight, E., Daymond, J., & Paroutis, S. (2020). Design-led strategy: How to bring Design Thinking into the art of strategic management. California Management Review, 62(2), 30–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125619897594

- Kolko, J. (2010). Abductive thinking and sensemaking: The drivers of design synthesis. Design Issues, 26(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1162/desi.2010.26.1.15

- KPMG. (2019). KPMG falls in love with digital agency. https://home.kpmg/au/en/home/media/press-releases/2019/05/kpmg-falls-in-love-with-digital-agency-14-may-2019.html

- Kummitha, R. K. R. (2019). Design Thinking in social organizations: Understanding the role of user engagement. Creativity and Innovation Management, 28(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12300

- Liedtka, J. (2006). Using Hypothesis-Driven thinking in strategy consulting. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?Abstract_id=907959

- Liedtka, J. (2015). Perspective: Linking Design Thinking with innovation outcomes through cognitive bias reduction. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(6), 925–938. https://doi.org/doi:10.1111/jpim.12163

- Liedtka, J. (2018). Why Design Thinking works. Harvard Business Review, 96(5), 72–79.

- Liedtka, J. (2020). Putting technology in its place: Design Thinking’s social technology at work. California Management Review, 62(2), 53–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125619897391

- Maciver, F., & O’Driscoll, A. (2010). Consultancy designer involvement in new product development in mature product categories: Who leads, the designer or the marketer? Paper presented at the Design Research Society (DRS) Conference, Montreal, Canada.

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2011). Designing qualitative research (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Martin, R. (2009). The design of business: Why design thinking is the next competitive advantage. Harvard Business Press.

- McDonagh, D., & Thomas, J. (2010). Rethinking Design Thinking: Empathy supporting innovation. Australasian Medical Journal, 3(8), 458–464. https://doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2010.391

- McKinsey & Company. (2015). Landing LUNAR. https://www.mckinsey.com/about-us/new-at-mckinsey-blog/landing-lunar

- Micheli, P., Perks, H., & Beverland, M. B. (2018). Elevating design in the organization. The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 86(6), 629–651. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12434

- Norman, D. (2010). Design Thinking: A useful myth. Core77. https://www.core77.com/posts/16790/design-thinking-a-useful-myth-16790

- Nunes, V. G. A. (2015). What does design and innovation mean for MSEs? A case study of eight Brazilian furniture firms. Design Management Journal, 10(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmj.12018

- Owen, C. (2007). Design Thinking: Notes on its nature and use. Design Research Quarterly, 2(1), 16–27.

- Pombo, F., & Tschimmel, K. (2005). Sapiens and demens in design thinking–perception as core. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of the European Academy of Design EAD,Bremen, Germany.

- Porcini, M. (2009). Your new design process is not enough—Hire Design Thinkers. Design Management Review, 20(3), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7169.2009.00017.x

- Rauth, I., Carlgren, L., & Elmquist, M. (2014). Making it happen: Legitimizing Design Thinking in large organizations. Design Management Journal, 9(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmj.12015

- Rylander, A. (2009). Design Thinking as knowledge work: Epistemological foundations and practical implications. Design Management Journal, 4(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1942-5074.2009.00003.x

- Seidel, V. (2000). Moving from design to strategy the four roles of design-led strategy consulting. Design Management Journal (Former Series), 11(2), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7169.2000.tb00017.x

- Sun, Q., & Runcie, C. (2016). Is service design in demand? Design Management Journal, 11(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmj.12028

- Timmermans, S., & Tavory, I. (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: From Grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory, 30(3), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275112457914

- Tripp, C. (2013). No empathy–No service. Design Management Review, 24(3), 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/drev.10253

- Verganti, R. (2009). Design driven innovation: Changing the rules of competition by radically innovating what things mean. Harvard Business Press.

- Woudhuysen, J. (2011). The craze for Design Thinking: Roots, A critique, and toward an alternative. Design Principles and Practices: An International Journal—Annual Review, 5(6), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.18848/1833-1874/CGP/v05i06/38216

- Wrigley, C. (2016). Design innovation catalysts: Education and impact. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics and Innovation, 2(2), 148–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2016.10.001

- Wrigley, C. (2017). Principles and practices of a design-led approach to innovation. International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation, 5(3–4), 235–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2017.1292152

Appendix 1

Semi-structured Interviews: Guiding Questions

How would you define DT?

Do you use DT in consultancy?

How often have you used DT in consultancy and why?

What DT methods have you used for your projects? Do they differ based on the project type i.e. strategy, operations, marketing, etc.?

Could you provide a brief description of your experience i.e. how many sessions, what kind of employees (managerial or lower-level staff), size of group. Etc.

Do you feel that DT strengthens or weakens the consultancy process, and why?

Which phase of DT (Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test) would you say is most crucial in deriving a pragmatic solution/recommendation for the client? Why?

Do you think DT is useful for shaping your client’s strategy? If yes, how? If not, why?