ABSTRACT

It can be claimed that technological systems are, in some ways, reflections of the designers’ way of thinking. These designs affect the behavior of the users and contribute to the reproduction of future designs, thus strengthening the existing human-technology relations. To address these issues critically, there is a need to challenge design ideation processes for generating a larger variety of design proposals that can contribute to varied users and user behavior. For this purpose, we propose a new method- Culture Coding, that can complement design ideation processes where generating, developing, and elaborating ideas is crucial. In this qualitative study, we explore the value of the proposed method in design by using design activities and a research-through-design approach. The experimental setup consists of two Design Cases where study participants contributed by taking part in two co-design workshops. The findings of the study indicate that Culture Coding may help to guide attention to new perspectives and challenge assumptions of the design context.

1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, a growing body of research has discussed how humans relate and interact with technological systems (Dourish, Citation2004; Lash, Citation2001; Sengers, Citation2018; Verbeek, Citation2008; Winner, Citation1980). Some authors have even considered that current societies could be even understood as technological forms of life (Lash, Citation2001). Hence, technologies are forms of life that reshape human activities (Dourish, Citation2004; Verbeek, Citation2008; Winner, Citation1980). According to Winner (Citation1980), once the use of technology becomes a repetitive pattern of life activity, we take its use for granted, and we do not very often stop to think and reflect on the implications. In other words, as technology users, we do not necessarily question our interaction, relations with it, nor the patterns of behavior that are connected to the technology use. As a result, people may end up adapting their behavior and experience of the world based on how they use technology. For this reason, we consider it necessary to question the norms and patterns of behavior that are part of technology use, through design. In this sense, one can say the designers of these systems have a great responsibility as they help define the human-technology relations which influence societies in general. Recognizing the complexity of these systems and their designs would require looking at all the parts in that system and analyzing their relations in detail, by using a rich repertoire of interrelated methods (Sevaldson, Citation2010). Here, it is essential to underline that technology designers typically represent a specific demographic group (Sengers, Citation2018). It has been claimed that to truly reflect our world’s viewpoints, the designers should come from a wider demographic, alternatively, adopt a complementary framework that would assist in the representation of a variety of perspectives (Parsons, Citation1991).

In this article we present Culture Coding, a method for diversifying design imaginations by creating variety in artifact association. We aim that the outcomes of using this method in design ideation could unfold more diverse user behavior, and on a broader scale challenge the human-technology relations. In the following sections, we introduce the theoretical background and the research-through-design approach deployed in this study. We describe the analysis of two design cases, where Culture Coding was used in co-design workshops, and consequently, we define the steps which the method offers. Based on the results, we discuss Culture Coding considering the development of new associations within a design context.

2. Theoretical background

The design solutions of everyday technology affect the world and how we behave in it (Nelson & Stolterman, Citation2014). Design movements such as anti-design and critical design (Bardzell & Bardzell, Citation2013) have highlighted that design products instill and reinforce ideology (Mazé & Redström, Citation2009). In the past couple of decades, critical voices in technology design have called attention to how the prioritized values and practices become invisible and natural, and therefore, are no longer questioned once the design is established (Feenberg, Citation2017a). Even though the emergence of a technological system is a complex matter, and a subject of various variables and distortions, the role of design has its part in affirming it as a socially embedded artifact. We know that to design is to consider the system in which the design should co-exist naturally with the environment, the situated artifacts, the involved actors and the interests that connect them to act (Hämäläinen et al., Citation2015). Often, some actors are dominant with their actions over others, leading to certain behaviors to be in some sense stronger, or more influential than others. In addition, Science and Technology Studies (STS) and critical theory of technology also acknowledge that technology is not value-neutral or universal (Feenberg, Citation2017b; Law, Citation2009; Winner, Citation1980).

In design practice, collaborative processes such as participatory or co-design processes notice a variety of ethical issues that play important roles, particularly when developing new products and in informing about design desirability (Carsten Stahl, Citation2014). On a higher level, these dynamics within the design decisions extend and end up influencing the user culture by supporting specific contexts of use to be developed in the future more than others (Feenberg, Citation2017a). Therefore, it can be said that the designers behind them have a significant role in envisioning the multiplicity of effects that specific use of technology can have. This can be described as an ethical issue.

On these grounds, it is reasonable to claim that designers of everyday technology need to be aware of the values they bring and of the conventions that they support, as the mainstream design paths are being strengthened and the upcoming design possibilities narrowed. This lack of design diversity has been acknowledged also in practice in the tech industry, which has led big ICT companies and tech design consultancies to change in some respect their approach in the design processes (Fuglerud, Citation2014). New strategies of more diverse design teams have been replacing the older ones, and a rise in adopting co-design approaches has been noted, with collective creativity and co-creation securely populating the new landscapes in design practice (Sanders & Stappers, Citation2008). In design research, the need to diversify design imaginations in creating technology has been raised concerning how it reflects on the users’ values, what they deem important and how it ties people, places and possibilities in our imaginations (Sengers, Citation2018). To create design solutions that can serve humans, but not enslave users to the culture that that technology imposes, the designer(s) would benefit from giving way to new directions for interactions by diversifying the design ideations.

According to Baron (Baron, Citation2007), people disregard possibilities, occurrences and evidence and make inferences that protect their favored ideas. Therefore, to open up a less biased perspective, one must be actively perceptive and aware of one’s subjective social reality among the other perceptive realities (Dourish, Citation2004). One approach, that has been proposed, to overcome these challenges is to expose others’ ideas to users or create more perspectives about the design context and its elements (Chan et al., Citation2017; Mackeprang et al., Citation2018). Merleau-Ponty’s ‘space of situation (Merleau-Ponty, Citation1996) highlights that the environment for which a design is developed should be regarded as the designers’ extension of their own physical body, which would serve to provide the designer with different perceptual abilities. Having an active perception means considering perception not only as embedded in the surrounding world but also as an enactment of the surrounding world. Perception is mainly based on sensory-guided action(s) and the cognitive structures are the result of the sensorimotor patterns that enable the senses to guide the action (Varela et al., Citation2017). This could particularly challenge the designer’s way of making associations, which is crucial as a form of making diverse assumptions in the design ideation process. This is discussed, for instance, by Diethlem as the processes of embodied design thinking, where the design implications are considered by the mind in the form of brain-body-in-the-world (Diethelm, Citation2019). The approach to design processes as embodied are actions toward uncovering the cognitive biases of the designer, leading to having novel understanding. In this way by using embodied perspectives, we support newly formed practices in design for technology with benefits that can be especially valuable in design that seeks to reform the human-technology relations.

When referring to technology, in this work we point to everyday technologies that are context-enabled, such as mobile or wearable technology, which is sensitive to the context of its user (Pejoska-Laajola et al., Citation2017; Salber et al., Citation1999).

Since these designs shape human experience and thus, behavior depending on the context in which they are used and developed, we consider these designs to benefit from embodied design ideation methods.

3. Introduction to the culture coding method

3.1. Background

Culture CodingFootnote1 was originally created by a creative collective in the <name> <city>, <country>. The name ‘Culture Coding’ was linked to the purpose of challenging cultural and learned behaviors through an instructive language. Initially, it was used in performative art happenings in interaction with audiences. The members of the creative collective behind it came from diverse professional backgrounds such as linguistics, computer coding languages, game design, media design theory and philosophy. The collective created so-called Culture Codes, or in short Codes (See, ), instances of the Culture Coding and performed them with audiences of between 5–120 participants per time in <name> media festivals in <city> during 2014, 2015,2016, 2017 and 2018, as well as in <country> in 2017. After 2017, Culture Coding continued to develop in different directions by different members of the collective.

3.2. Description

The Culture Coding method can be described as a step-by-step instructional method that guides the attention of its user toward new perceptions of artifacts, after which new associations of the artifacts are formed. It is communicated to the user of the Codes in a style that resembles a recipe for cognitive action. It does so by prompting the one who is performing them to reflect on their assumptions and challenge the usual way to perceive the artifact(s) and events within an embodied context. These instructions provoke changes in relating to the artifacts. Culture Coding aims to bring up mental or physical interaction schemes, by initiating physical interactions with artifacts, such as elements, objects, persons, or events, as well as mental plays with artifacts such as concepts, memories, or fantasies. The instructions also often prompt personal memories into the process.

When it comes to the dynamics of the Culture Coding method, they can be compared to the ones that gamification design methods facilitate (Mora et al., Citation2015), which contribute to a game-like experience (Calvillo-Gámez et al., Citation2015, p.). In this sense, the meaning is constructed through the powerful connection of the instructions or rules of the game and the player (Salen et al., Citation2004; See, ).

The communication style of the Codes can be also related to the expression form of the works of Instructional Art as seen in the examples of the work by Yoko Ono in “Instructional paintings“ (Ono, Citation1970) – painting for the wind or in Julio Cortázar’s narration ”Instructions on how to cry” (Cortázar, Citation1962). The Culture Codes were written in a simple text language, but they can also be conveyed through an artistic format, which is not limited to text. Each instruction is a step forward to expose assumptions about the design context, and playfully and mindfully guide the attention toward new perceptions.

3.3. Related methods

Several earlier studies have demonstrated that ideation toolkits benefit most when being facilitated through physical tools such as cards, tables, posters etc. (Mattelmäki, Citation2005),(Hornecker, Citation2010;Hildén et al., Citation2017). In the area of design for technology several toolkits have been investigated, such as the IDEO cards (Tschimmel, Citation2012), Plex card (Lucero & Arrasvuori, Citation2010), envisioning cards (Friedman & Hendry, Citation2012). These cards have proven to catalyze imagination in the designer, by guiding the designer to be playful (Lucero & Arrasvuori, Citation2010), envision (Friedman & Hendry, Citation2012) and gain a new perspective or develop a new approach (Tschimmel, Citation2012). Compared to these ideation toolkits, Culture Coding builds on these by the value it brings to the process by tightly interweaving these instructions with the designer’s personal habituated practices, also referred to as embodied memory (Fuchs, Citation2016).

Culture Coding is also drawing from known creativity concepts like defamiliarization, which promotes the idea that to make a design setting an inspiring and creative playground, we have to make it strange to the designer (Bell et al., Citation2005). Bell et al. (Citation2005) described their studies in the design of home technology, where the defamiliarization of the home technologies provided an opportunity for technology designers to actively reflect on, as opposed to passively propagate, the existing politics and culture of the life in a home.

In this direction, Culture Coding aims to develop the approach into a method that can be practically associated with existing creativity techniques such as de-contextualizing, repurposing or exaggerating certain qualities (Kaufman & Sternberg, Citation2010) and estrangement of the artifacts in a design context, with a distinction toward an embodied ideation method approach to the context (Wilde et al., Citation2017). Therefore, the embodiment in the context of Culture Coding is also related to somaesthetic qualities that may add to the ideation process (Höök et al., Citation2016). In the sphere of ideation, this method can be also compared to Collaborative ideation practices (Mackeprang et al., Citation2018) that have been used in design practice for idea generation, although not so much in idea validation. Other studies in embodied design inform about how a real-life embodying and immersing into a context can influence design inspiration (So, Citation2020). In this sense, like the approach of Culture Coding, the studies made by So (Citation2020), exemplify how design inspiration can be induced to designer participants of an immersive experience, and how it can be relevant for the design process.

4. Methodological approach

This qualitative study is based on research-through-design, a methodology used to contribute to the pool of knowledge through design activities. We chose Research-through-design as a suitable method of investigation because of its properties of being a practice-led design process where the act of making provides particular ways of knowing it (Zimmerman & Forlizzi, Citation2014). In this way, we explored Culture Coding as a method for diversifying artifact associations through embodied reflections. For this purpose, we created specific Culture Codes and applied them in use with participants in two design cases. In the process, we collected qualitative data about the method as well as the used Codes, described in more detail in the Research design section. The participants in the design cases shared several perspectives about their experiences in the design cases through discussions about their initial impressions, reflections about Culture Coding and related opportunities for use. In addition with the participants, we explored pathways for further development and validation of the method.

4.1. Research design

The first co-design workshop was the BecomeBecome art residency which took place 21–31 July 2017 at Arebyte Gallery in London, Great Britain – and to which we will refer in this work as Design Case 1. The second co-design workshop took place at the Pixelache media-art festival, in Helsinki, Finland from 21 to 23 September 2017 – here referred to as Design Case 2. The Design Case 1 informed the creation of the Design Case 2 in terms of design, distribution, and communication of the method to the participants. In both cases, people voluntarily signed up to participate in Culture Coding workshops and were introduced briefly to the method before participation. Their active participation lasted roughly 2 hours and it took place in the venues of the cultural happening. The participants were given Culture Codes which contained instructions that encouraged them to engage with the environment and artifacts through different tasks (See, )

To study the participants and their use of the method we applied autoethnography by collecting such data as field notes and documenting the participants’ actions and outcomes. After the performed actions, in both design cases we moderated group discussions about the experiences with Culture Coding and in Design case 1 there was additionally a questionnaire distributed to the participants for collecting impressions and reflections. The field and discussion notes, documentation, and questionnaires were used for shaping the formulation of the method, validating its usability, mapping out possible application areas, and informing the next design iteration. In this sense, the participants were part of a co-design process. A description of the methods and data collection are presented in .

Table 1. Methods used in the design cases.

4.2. Participant details

A total of 30 participants were involved in this study. In the Design Case 1 there were 12 participants, between 20 and 65 years old. Seven of them filled in the online Questionnaire. Six of them were self-identified women and 1 was a self-identified man. Four of seven (57,1%) were ages 36–45; two of seven (28,7%) were aged 45–60, and one (14,3%) was 20–25 old. In the Design Case 2 there were eighteen (n = 18) participants attending the workshop, between 20 and 65 years old. Out of them, 11 were self-identified females and 7 self-identified males from diverse cultural backgrounds who use digital social and communication technology daily.

In both cases, the educational level was not inquired, instead we asked the participants to describe their personal interests. All of them were highly interested in arts and humanities, and highlighted topics included culture, philosophy, communication, politics, and human senses. In addition, all of the participants had daily interaction with the internet through their personal smartphones and computers and were highly skilled in technology-mediated communication in social media, resourcing online material as well as private communication with friends and family.

4.3. Design cases

4.3.1. Design case 1: generating new associations

The main objective of the workshop was to see how new associations are generated with the help of Culture Coding. The instructions of the Codes prompted participants to interact with the environment in a way that creates different experiences, interpretations, and associations of the artifacts in the environment. Thematically we could say that the Culture Codes for Design Case 1 were designed to interrogate cultural conventions and perceptions of technological artifacts (See, and 4). In addition to generating new associations, the secondary aim of this Design Case was to explore whether this method could trigger different behaviors mediated by the new artifact associations.

During the workshop session, the participants were given five different Culture Codes to rethink everyday artifacts and technology (see, ). The Codes were distributed on paper to each participant in the group, who then acted upon the Code’s instructions individually and with an open-ended interpretation.

After performing the Codes, the participants filled in a semi-open questionnaireFootnote2 online where they gave feedback about their experience. The questionnaire consisted of 30 open-ended questions, to explore how the participants saw the value of the method and how they envisioned its use in their technology-mediated practices. It also informed the next design iteration of the Codes, as it included questions about the wishes and expectations of the participants regarding the future developments of Culture Coding. The participants’ experiences with Culture Coding are described in the Findings section.

In addition to demographic questions and study participation consent, the questionnaire was organized in four thematic groups of questions including (1) Personal relations with information and communication technology; (2) Culture Coding concept (3) Personal experience with Culture Coding; (4) The future of Culture Coding- application areas and uses.

4.3.2. Design case 2: prototyping experiences

The second design case was built on the results from the first workshop, where the qualitative analysis of the questionnaire answers revealed some aspect of how Culture Coding affected and altered the participants’ perception and thus, their experience of the context. None of the previous participants (Design case 1) were present in this second case, which happened in a different context and a different geographical location.

Consequently, the second workshop focused on prototyping experiences (Buchenau & Suri, Citation2000), where we studied how the experiences of the context change when the instructions of the Codes are delivered to the participant through mobile technology, providing the possibility to have location-based instructions. The aim was to test contextual associations so that each participant could be in a different location of their choice and could move around as desired when receiving Code instructions on their smartphone.

Thematically, while the first design case can be considered a free exploration of the potential value of Culture Codes, the second case focused on challenging the everyday behaviors which are related to the use of ubiquitous technology. These behaviors could be related to certain user tendencies, often connected with repetitive or habitual qualities such as cognitive biases, and strengthened by the mediating technology (Buss, Citation2015). These behaviors were particularly interesting because of their connection to the ideation process in design practices, and eventually, the potential impact on the design outcomes.

For these reasons, four different types of Codes were created with themes related to exploring cognitive biases, which condition bizarre (), funny, visually striking, or anthropomorphic things. These biases correspond to the cognitive bias codex (Benson, Citation2016): Self-relevance effect, Von Restorff effect, Bizarreness effect and Negativity bias.

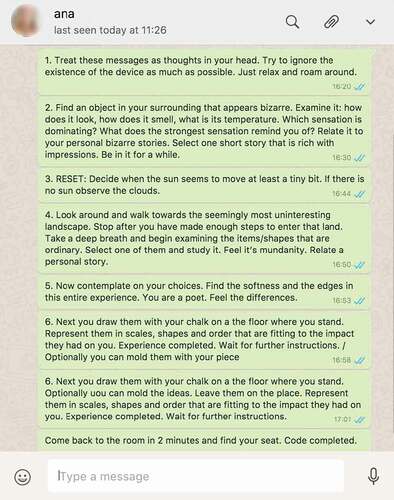

Figure 5. Snapshot of whatsapp with culture code on the bizarreness effect provided to participants in design case 2.

The participants attending the workshop (n = 18) were between 20 and 65 years old, 11 self-identified female and 7 self-identified males from diverse cultural backgrounds who use digital social and communication technology daily. The duration of the workshop was approximately 2 hours, consisting of three parts: Acting through Culture Codes (approximately 40 min); Discussion on the experiences (approximately 30 mins) and user experience design session (approximately 30 mins). The event was photo-documented, the Codes were digitally archived, and notes were taken from the discussions. The facilitators used an existing mobile social media service (WhatsApp) for distributing the Codes () to the participant’s mobile phones. The idea was to simulate an algorithm in a Wizard of Oz fashion, that could work independently with a user. Wizard of Oz prototypes have been used extensively to recreate the experience of a user interface (UI) before a system is fully functional (Dahlbäck et al., Citation1993; Klemmer et al., Citation2000; Maulsby et al., Citation1993). The Wizard of Oz can be considered experience prototyping in which people interact with a system without knowing that the responses are generated by a human instead of a computer (Bella & Hanington, Citation2012).

This medium and access to the Culture Codes digitally provided new data for the research. It enabled distribution of the Codes in consequent steps systematically to each participant while adjusting the tempo of each step remotely. The participants were instructed to roam and explore around the designated building where random artifacts were placed, and they were instructed to interact with an artifact exactly upon receiving a Code on their smartphones. In this way, the experience was customized through the Culture Codes in terms of offering new perceptions that could be triggered in the areas in which the participant happened to be when receiving the Code. This differed from the previous workshop where the participants received all the code steps at once, in one place and on a piece of paper and decided themselves when they were ready for the next step and proceeded without intermediation. Each participant had a unique experience with an artifact that they found from the environment and interacted with it mentally and physically ().

Figure 6. Image from a participant and his process in the workshop from design case 2: prototyping experiences.

The workshop ended with a group discussion about the experiences and was followed by voluntary participation in a UI/UX design challenge for the next iteration of the Culture Codes. The discussion and the design workshop were documented by taking field notes.

5. Findings

In both design cases, the workshop participants’ experiences with the Culture Codes were studied. In the research, an autoethnography approach (Marechal, Citation2010) was applied, so that the main researcher participated in the design cases and collected the data in a form of field notes, questionnaires, photos and Codes created. The data were then studied and analyzed by the researchers distancing themselves from the cases. To overcome the weaknesses that might arise from the richness of data, methodological triangulation (Biklen, Citation1992) was used by combining the researcher’s own immediate observations, field notes, questionnaire results and photos to locate the most prominent themes from the cases. The Mode 2 approach (Gibbons et al., Citation1994) was used, which is known in the design research field as a non-fragmented inclusive approach to research. This meant that the design cases were explored in a transdisciplinary manner, by valuing the inputs from all the different participants as formative to the knowledge and by the context of the research. Therefore, the data analysis took place partly already during the Cases with the participants and later with all of the researchers going through the data individually and as a team.

We inquired about different objectives in the design cases. The Design Case 1 aimed to examine cultural conventions and perceptions of technological artifacts. These outcomes were used to create the Second Design case, which investigated how the everyday behaviors related to the use of ubiquitous technology can be challenged. In this regard, we took into account that these behaviors could be related to cognitive biases as many studies suggest.

The experiences of the participants recognized during the analysis constituted the initial research insights. The research-through-design (Zimmerman & Forlizzi, Citation2014) was applied when using the insights to inform the next stages and to explore potential solutions, where our hypothesis shaped in the form of a design concept. From the findings, we drafted the insights of Culture Coding. In the beginning of the research study, the attempt was to understand if and how the Codes foster awareness of the design context and enhance perception. In some cases, this was achieved by having codes that instruct interaction with artifacts by actively engaging the use of the person’s physical senses, in an attempt to develop more significant sensory triggers and experiences. In addition, all the participants went beyond fostering awareness and enhancing perception through their Codes. The results from the questionnaire in the Design Case 1, showed that 71,4% would use Culture Coding again, 28,6% said that they are not sure/maybe use it. 57,1% were willing to create new Codes in the future, while 42,9% were not sure of it. There were no negative responses in these closed-question inquiries.

According to some of the participants’ responses in the open questions of the questionnaire, the Culture Codes enabled creative thinking by guiding attention to new directions and supporting reflection. For instance, differences in the participants’ observations before and after using the method were discovered, as reported by one of the participants: “I can think of the use of things and expand things with a different idea” (F-06). From the Design Case 2 it was found that the participants were being alert and attentive to the environment while imagining and re-creating ideas that were part of the experience of Culture Coding. These results indicated that the method supports reflection embodied in the activities and the unfolding circumstances in which the activities occur.

The thematic categorization of the data revealed two characteristics that the Culture Coding may support: New perspectives and Challenging assumptions. In the following we describe them in more detail.

5.1. New perspectives

Especially in the Design Case 1 the participants were able to develop new perceptual abilities. For all the 12 participants, Culture Coding was a new approach to questioning, acting, and perceiving. The participants emphasized that the method enabled them to see things from different angles. For instance, to the question of “How do you understand Culture Coding? What is it?“ one of the participants answered, “to have a new perspective to usual things“ (F-06). The other participants had very similar impressions of it and pointed out that Culture Coding facilitates ”the process of understanding” (F-05), and ”It facilitates negotiating with perceptions” (F-02).

When considering design practice, the ability to have new perceptions and insights in a context may have a real value. Especially in the design of products and services that are used in different contexts, the ability to change perceptions becomes valuable. The results indicate that in an early stage of design ideation, the Culture Coding method may provide product and service designers new creative ideas that are better serving the situations of use.

5.2. Challenge assumptions

Another common experience with the participants was that Culture Coding challenges assumptions, linked to context-awareness. The participants found that the environment and artifacts in it can be reexamined by challenging the way the associations are created. After taking part in the Code creation task, participants felt confident about their ability to address issues in alternative ways: “I can now find magic tools in my environment by asking the right questions“ (F-02). Examining the participants’ co-created Codes, 7 out of the 12 participants confirmed fostering unconventional thinking by slowing down and observing. Some of the co-created Codes invited users to identify patterns, which could be visual, auditory, tactile, and olfactory. After experimenting with Culture Coding, participants learned to guide attention consciously “I can observe things around me carefully” (F-06), as well as exercise self-reflection, ”(I) realized there is a pattern to the things that I notice about art” (F-02). The Codes that were co-created by the participants in the workshop made them experience their observations and awareness of affection. For instance, 7 of the 12 participants invited readers to consider their own emotions and gain self-awareness through the Codes. “I learned about the feelings and desires the other(s) have” (F-02). Similarly, as the ability to have new perspectives, challenging assumptions is useful in design practice. The ability to think and to see things differently, as well as empathy for others (users) are important design skills. In the case of technology that is used in various social and cultural situations and contexts this becomes critical.

The results deriving from the two main characteristics of using Culture Coding indicate that designers using this method may learn and apply these skills better and thus, diversify the association making of the artifacts in creative processes.

6. Using culture coding

Culture Codes instructs mental and physical interaction with contextual artifact(s) and guides the participant’s attention toward a particularity to enable different interpretations. The process finishes with a new experience, a new interpretation, a different association of the artifacts or a new viewpoint.

Our results demonstrate that Culture Coding can be useful when applied in ideation processes, where generating, developing, and elaborating ideas is crucial, while being complementary with other Creative practitioners, such as product and service designers, as well as technology developers may find value from the use of the method.

In practice, the designer of products and services leading an ideation process can choose to use a Code, modify it for the design task and context if needed or create their own Codes. Based on the description Culture Coding, the designer can freely formulate her/his own Code instructions to aid the processes. The Code can be used by one designer or many co-designers if multiple new associations are deemed helpful. The Codes can be given to the designer(s) in the form of a paper card or sent in a digital format. The user of the Code(s) can interpret the instructions freely. The time for performing the Code may be instructed in the Code or set by the facilitator. The Code could provide instructions for actions that guide a follow-up discussion. The Code may instruct the (co-)creation of other Codes and instruct to apply them further with other users/designers.

An important aspect of the Culture Codes is that anyone can create their own Codes and adapt them to the needs of the design task and the context. A general guideline that can be used in creating the Codes is presented in . The idea is to use instructional language, such as the one in food recipes, to communicate the instructions for guiding attention, interacting mentally and physically with artifacts. Follow these steps by interpreting them freely.

Table 2. A guideline for creating culture codes.

7. Discussion

The results presented in this paper indicate the potential value of the method. The current findings point to that the Culture Coding may help to guide the attention to the design context, challenge the perception of the artifacts and develop new associations.

The outcome of generating new artifact associations based on modification, repurposing and free association can be seen as part of a reflection process in which participants experimented with different types of practices. The method shares with reflective design some of its key strategies: encouraging reflection through artifacts, focusing on personal experiences and understanding technologies as culturally contextualized (Sengers et al., Citation2005). As noted by Dourish (Dourish, Citation2004), interaction is intimately connected to the environment in which the interaction occurs. A particular setting enables concrete terms for reflection on the activities and artifacts, as opposed to abstract ones. In this sense, we build knowledge through the embodied dimension that enables reflection in designers’ and artisans’ work (Groth et al., Citation2013). The person can focus on details, specifics and actual cases when exploring an idea, emotion, or experience with the everyday technologies. To a certain extent, Culture Coding might be considered similar to critical design practices, where the aim is not to problem-solve but to open up spaces for reflection, debate and speculation (Bardzell & Bardzell, Citation2013; Dunne & Raby, Citation2013). To some degree, Culture Coding echoes also with Human-Centered and Activity-Centered Design, particularly in approaches where the focus is on human experiences in action (Norman, Citation2006).

Technology designers need to consider their responsibility and anticipate the mediation role that the technology would have in the future (Verbeek, Citation2006). This can be done by carrying out a mediation analysis with the designers’ imagination (Verbeek, Citation2006), as a step toward the reformation of human-technology relations. By foreseeing these practices and imagining others, the designers reflect in an embodied way and anticipate these mediations. In addition, embodied design approaches would enable circumstances for engaging the user of that technology in an emergent design space and experience it with their full sensory capacity (Wilde et al., Citation2017). Culture Coding explored this by making associations with the artifacts, and thus encouraged its users to explore new behaviors and relations with everyday technologies.

In terms of application areas, our results indicate that Culture Coding can be useful for design ideation, particularly in design contexts of products and services where embodied ideation can bring value. With this method the designer can use new perceptual abilities to explore the design context and be able to challenge his/her own assumptions about the artifacts, thus producing diverse design solutions. We have studied the contexts of designs related to mobile everyday technology, and other areas that could benefit from the method should be investigated further. Avenues may be opened by exploring versions of the method made for designer teams.

The generalizability of these results is subject to certain limitations. Culture Coding was initially created and used as a performance with audiences in the culture sector. During several years, we witnessed experiences that have potential for being relevant in creative processes, and thus began to study design application areas. The design cases in the study involved participants mostly with creative professional backgrounds that are technologically savvy. This can be seen as both positive and negative. As creative practitioners themselves do the provided feedback on the method, it validates the usefulness of the method for design practice. The co-design workshops were both organized through cultural events, which meant that the persons involved in the study had certain interest toward performative practices. More studies are needed that involve designers and real-life ideation processes of new products and services, and to explore the practical implications of the method. Furthermore, the study could benefit from understanding the occurrence of reflection while using the method, in-depth. Although we theoretically consider that the embodied reflection occurs simultaneously with the action, this study did not consider how the reflection happens and whether it appears during the performance of the Codes, during and after the Codes, or only after the Culture Coding has been performed. In addition, future studies should explore the variables in acting through Culture Coding related to outcomes. In this sense, more research is needed before it may firmly be established that the method offers value above and beyond other methods alike. The nature of the study was to explore the potential use of Culture Codes in two Cases with the participants. More experimental study with control groups could provide better evidence on possible changes among the participants in addition to their subjective experiences. Although, experiment with a control group would be difficult to design, we see its value in the further research.

8. Conclusion

In conclusion, we see that an area of application that can benefit from using the Culture Coding method are design processes, particularly the ideation process about experience, context, and technology. The method supports new perceptual experiences of artifacts to gain insight into the properties of the things in question. In this sense, this method can contribute to the design process in creating new associations of the environment, thus diversifying perspectives on the designs that affect technology use and culture.

Acknowledgments

Regarding the concept of Culture Coding, we are grateful to Pekko Koskinen who coined the term and for the Blurrifier code which we used in part of this study. Thanks to Ari-Pekka Lappi and Agnieszka Pokrywka for their inspiration and collaboration on versions of Culture Coding created between 2014-2018. We recognize their individual developments that have continued with Culture Coding. Special thanks to Agnieszka Pokrywka for collaborative efforts in the workshops in this study and co-creating part of the Codes. We also acknowledge publications that use or refer to notions of Culture Codes and/or Culture Coding (Clotaire, Citation2006),(Coyle, Citation2018), however we do not relate to these concepts and formulations in our body of work, rather we develop our frame for Culture Coding

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. We acknowledge publications that use or refer to notions of Culture Codes and/or Culture Coding (Clotaire, Citation2006; Coyle, Citation2018), however we do not relate to these concepts and formulations in our body of work, rather we develop our frame for Culture Coding.

2. A link to this questionnaire form is provided in the Appendix section

References

- Bardzell, J., & Bardzell, S. (2013). What is” critical” about critical design? Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 3297–3306. New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Baron, J. (2007). Thinking and deciding (4th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Bell, G., Blythe, M., & Sengers, P. (2005). Making by making strange: Defamiliarization and the design of domestic technologies. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 12(2), 149–173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1067860.1067862

- Bella, M., & Hanington, B. (2012). Universal methods of design. Rockport Publishers.

- Benson, B. (2016, September 1). Better humans. Cognitive Bias Cheat Sheet. https://medium.com/better-humans/cognitive-bias-cheat-sheet-55a472476b18

- Biklen, S. K. (1992). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods. Allyn and Bacon.

- Buchenau, M., & Suri, J. F. (2000). Experience prototyping (pp. 424–433). DIS’00, Brooklyn, New York. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/347642.347802

- Buss, D. M. (2015). The Evolution of Cognitive Bias. In Haselton, Martie G., Nettle, Daniel, Andrews, Paul W., (Eds.). The handbook of evolutionary psychology, volume 2: Integrations (pp. 724–746). John Wiley & Sons.

- Calvillo-Gámez, E. H., Cairns, P., & Cox, A. L. (2015). Assessing the core elements of the gaming experience. In Bernhaupt, Regina (Eds.), Game user experience evaluation (pp. 37–62). Springer.

- Carsten Stahl, B. (2014). Participatory design as ethical practice – Concepts, reality and conditions. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 12(1), 10–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JICES-11-2013-0044

- Chan, J., Siangliulue, P., Qori Mcdonald, D., Liu, R., Moradinezhad, R., Aman, S., Solovey, E. T., Gajos, K. Z., & Dow, S. P. (2017). Semantically far inspirations considered harmful? Accounting for cognitive states in collaborative ideation. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGCHI conference on creativity and cognition, Singapore, 93–105. New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/3059454.3059455

- Clotaire, R. (2006). The culture code: An ingenious way to understand why people around the world live and buy as they do. New York.

- Cortázar, J. (1962). Historia de Cronopios y Famas. Minotauro.

- Coyle, D. (2018). The culture code: The secrets of highly successful groups. Bantam.

- Dahlbäck, N., Jönsson, A., & Ahrenberg, L. (1993). Wizard of Oz studies—why and how. Knowledge-Based Systems, 6(4), 258–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0950-7051(93)90017-N

- Diethelm, J. (2019). Embodied design thinking. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 5(1), 44–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2019.02.001

- Dourish, P. (2004). Where the action is: The foundations of embodied interaction. MIT press.

- Dunne, A., & Raby, F. (2013). Speculative everything: Design, fiction, and social dreaming. MIT press.

- Feenberg, A. (2017a). A critical theory of technology. In U. Felt, R. Fouché, & L. Smith-Doerr (Eds.), The handbook of science and technology studies (pp. 635–663). MIT press.

- Feenberg, A. (2017b). Technosystem: The social life of reason. Harvard University Press.

- Friedman, B., & Hendry, D. (2012). The envisioning cards: A toolkit for catalyzing humanistic and technical imaginations. Proceedings of the 2012 ACM annual conference on human factors in computing systems - CHI, Austin, Texas, USA.’12 (pp. 1145). New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/2207676.2208562

- Fuchs, T. (2016). Embodied knowledge–embodied memory. In Rinofner-Kreidl, S, Wiltsche, H. A (Eds.), Analytic and continental philosophy. methods and perspectives. Proceedings of the 37th International Wittgenstein Symposium 23 (pp. 215–229). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

- Fuglerud, K. S. (2014). Inclusive design of ICT: The challenge of diversity. Department of media and communication, University of Oslo. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270508482_Inclusive_design_of_ICT_The_challenge_of_diversity

- Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. sage.

- Groth, C., Mäkelä, M., & Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P. (2013). Making sense. what can we learn from experts of tactile knowledge? FormAkademisk-Forskningstidsskrift for Design Og Designdidaktikk, 6(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.656

- Hämäläinen, R. P., Jones, R., & Saarinen, E. (2015). Being better better: Living with systems intelligence. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Hildén, E., Ojala, J., & Väänänen, K. (2017). Development of context cards: A bus-specific ideation tool for co-design workshops. Proceedings of the 21st International Academic Mindtrek Conference (pp. 137–146). New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/3131085.3131092

- Höök, K., Jonsson, M. P., Staahl, A., & Mercurio, J. (2016). Somaesthetic appreciation design. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors IN Computing Systems, (pp. 3131–3142). San Jose, CA, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, United States.

- Hornecker, E. (2010). Creative idea exploration within the structure of a guiding framework: The card brainstorming game. Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (pp. 101–108). New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1709886.1709905

- Kaufman, J. C., & Sternberg, R. J. (2010). The Cambridge handbook of creativity. Cambridge University Press.

- Klemmer, S. R., Sinha, A. K., Chen, J., Landay, J. A., Aboobaker, N., & Wang, A. (2000). Suede: A wizard of Oz prototyping tool for speech user interfaces. Proceedings of the 13th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (pp. 1–10). New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/354401.354406

- Lash, S. (2001). Technological forms of life. Theory, Culture & Society, 18(1), 105–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/02632760122051661

- Law, J. (2009). Actor network theory and material semiotics. In B. Turner (Ed.), The new Blackwell companion to social theory (pp. 141–158). John Wiley & Sons.

- Lucero, A., & Arrasvuori, J. (2010). PLEX cards: A source of inspiration when designing for playfulness. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Fun and Games, 28–37. New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Mackeprang, M., Khiat, A., & Müller-Birn, C. (2018). Concept validation during collaborative ideation and its effect on ideation outcome. Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, Canada, 1–6. New York; NY; United States: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/3170427.3188485

- Marechal, G. (2010). Autoethnography. In A. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of case study research (pp. 43–45). Sage.

- Mattelmäki, T. (2005). Applying probes – From inspirational notes to collaborative insights. CoDesign, 1(2), 83–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15719880500135821

- Maulsby, D., Greenberg, S., & Mander, R. (1993). Prototyping an intelligent agent through wizard of Oz. Proceedings of the INTERACT’93 and CHI’93 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 277–284. New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Mazé, R., & Redström, J. (2009). Difficult forms: Critical practices of design and research. Research Design Journal, 1, 28–39.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1996). Phenomenology of perception. Motilal Banarsidass Publisher.

- Mora, A., Riera, D., Gonzalez, C., & Arnedo-Moreno, J. (2015). A literature review of gamification design frameworks. 2015 7th International Conference on Games and Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications (VS-Games), Skövde, Sweden, 1–8. New York, NY, USA: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1109/VS-GAMES.2015.7295760

- Nelson, H. G., & Stolterman, E. (2014). The design way. Intentional change in an unpredictable world (Second ed.). MIT press.

- Norman, D. A. (2006). Logic versus usage: The case for activity-centered design. Interactions, 13(6), 45–ff. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1167948.1167978

- Ono, Y. (1970). Grapefruit: A book of instructions and drawings by Yoko Ono. Simon and Schuster.

- Parsons, T. (1991). The social system. Psychology Press.

- Pejoska-Laajola, J., Reponen, S., Virnes, M., & Leinonen, T. (2017). Mobile augmented communication for remote collaboration in a physical work context. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(6), 11–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3622

- Salber, D., Dey, A. K., & Abowd, G. D. (1999). The context toolkit: Aiding the development of context-enabled applications. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Pittsburgh Pennsylvania USA, 434–441. New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/302979.303126

- Salen, K., Tekinbaş, K. S., & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of play: Game design fundamentals. MIT press.

- Sanders, E. B.-N., & Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068

- Sengers, P. (2018). Diversifying design imaginations. Proceedings of the 2018 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2018 - DIS ’18, Hong Kong, China, 7. New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/3196709.3196823

- Sengers, P., Boehner, K., David, S., & Kaye, J. ‘Jofish’. (2005). Reflective design. Proceedings of the 4th Decennial Conference on Critical Computing: Between Sense and Sensibility, Aarhus, Denmark, 49–58. New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1094562.1094569

- Sevaldson, B. (2010). Discussions & movements in design research. FormAkademisk-Forskningstidsskrift for Design Og Designdidaktikk, 3(1): 8–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.137

- So, C. (2020). Embodied design: Design inspiration and mood improvement depend on perceived stimulus sources and predict satisfaction with an immersion experience. International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation, 8(2), 70–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2019.1638835

- Tschimmel, K. (2012). Design thinking as an effective toolkit for innovation. ISPIM Conference Proceedings, Barcelona, Spain, 1.

- Varela, F. J., Rosch, E., & Thompson, E. (2017). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience (2nd ed.). MIT press.

- Verbeek, -P.-P. (2006). Materializing morality: Design ethics and technological mediation. Science, Technology & Human Values, 31(3), 361–380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243905285847

- Verbeek, -P.-P. (2008). Morality in design: Design ethics and the morality of technological artifacts. In Kroes, Peter, Vermaas, Pieter E., Light, Andrew, Moore, Steven A. (Eds.),Philosophy and design (pp. 91–103). Springer

- Wilde, D., Vallgårda, A., & Tomico, O. (2017). Embodied design ideation methods: Analysing the power of estrangement. Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, Colorado, USA, 5158–5170. New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025873

- Winner, L. (1980). Do artifacts have politics? Daedalus, Modern Technology: Problem or Opportunity?, 109(1), 121–136. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20024652

- Zimmerman, J., & Forlizzi, J. (2014). Research through design in HCI. In J. S. Olson & W. A. Kellogg (Eds.), Ways of knowing in HCI (pp. 167–189). Springer: New York. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-0378-8_8

Appendix

The questionnaire form used in Design case 1 can be found here: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScBg7NCHcgnB0CPrJc8g-Jeg9CZ3Cl65i9eakQ-1lc9FRlQ3g/viewform?usp=sf_link