ABSTRACT

The Design Thinking (DT) mindset, a fundamental aspect of User-Centred Design (UCD), is often presented as a powerful and accessible trigger for innovation. There is much discussion in the extant literature on the communication of the DT concept to non-design practitioners to encourage broader use of design-led innovation. The present study expands this discussion by exploring which DT mindset attributes are considered meaningful for non-design professionals in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). It presents a UCD intervention that embeds the DT mindset attributes to introduce design-led innovation to SMEs of the Welsh creative industries. Semi-structured interviews, non-participatory observation, and reflective open-ended questioning are utilised to analyse the impact of the intervention in supporting creative industry practitioners’ understanding of the DT mindset and design-led innovation approaches. Our findings demonstrate that the intervention has prompted participants to (i) challenge the idea of ‘ideas,’ (ii) frame failure as an option, (iii) learn to trust the process, (iv) acquire innovation self-efficacy, (v) view collaboration = learning, and (vi) change their perception of innovation. We discuss how these identified ‘mindset shifts’ are valuable toward building individual innovation capacities in non-design industries.

1. Introduction

The last decade has seen a significant increase in the implementation of Design Thinking (DT) in non-design organisations (see, e.g., Altman et al., Citation2018; Bell, Citation2018; Chia & Lee, Citation2019). This is largely due to its effective role in enabling disruptive innovation strategies (Radnejad et al., Citation2022) and leveraging the innovation capabilities of organisations including Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) (Mesa et al., Citation2022). The implementation of DT across various industry sectors has also demonstrated its capacity to boost competitive advantage (Pham et al., Citation2022), organisational agility (Fischer et al., Citation2020) and digital transformation of organisations (Magistretti et al., Citation2021).

Nevertheless, it has been acknowledged that putting DT into practice can be challenging. Its non-linear nature is deemed difficult to align with conventional business practices, causing a disconnect with common existing organisational structures (Kupp et al., Citation2017). This has attracted criticism surrounding the applicability of DT in the Research and Development (R&D) activities of non-design industries. Critics have described it as a simplified, ‘formulaic, and naive view of the design process using buzzwords and corporate jargon’ to benefit non-designers (Hernández-Ramírez, Citation2018, p. 46). However, it can be argued that such criticism may have stemmed from the common misunderstanding of the fundamental concept of DT (Matović, Citation2019). Its meaning tends to shift across different discourses and fields (Johansson‐Sköldberg et al., Citation2013) and has often been misinterpreted as a rigid methodology (Gray, Citation2016). Moreover, an ad-hoc adoption of the methods may have also led to its core defining concept being lost in translation, contributing further to the claims of its impracticality in non-design industries.

Considering this, the present study intends to explore how DT can be appropriately introduced to non-design industries, by focusing on the mindset attributes embedded in the concept. It is posited that the mindset shifts resulting from engaging in DT could potentially nurture innovation capacities in non-design industries. Through an appropriate introduction of DT, the potential misuse of designers’ methods – where DT is equivalent to an open-access ‘toolbox’ – can be avoided (Johansson‐Sköldberg et al., Citation2013). Despite the increasing number of online resources and toolkits that are publicly accessible, it is suggested that designers should lead the process to gain the intended results (Liedtka & Ogilvie, Citation2012). The lack of understanding of design and confidence to effectively apply DT suggest that external facilitation is necessary (Teso & Walters, Citation2016, p. 90). We begin this exploration with a clear notion that effective execution of DT relies prominently on understanding the mindset and reasoning that guide designers’ actions, more than just identifying and replicating the tools or methods designers apply. Implementing the diluted version of DT, where the underlying cognitive processes and actions are detached from the methods, may be impractical for R&D and innovation. Therefore, we posit that in the first introduction to the concept, designers should lead the process of guiding and facilitating non-designers in understanding how DT is used for R&D and innovation processes.

Such an awareness of suitable facilitation and understanding of DT to achieve innovation has seen large organisations investing in ideation spaces or design teams, which may not be possible in the case of resource-limited, smaller organisations such as SMEs (Heck et al., Citation2015). Although there are overlapping challenges in implementing DT for both large and small organisations regarding cultural and operational shifts, SMEs’ apparent lack of dedicated resources is one of the major barriers to its implementation (Fischer et al., Citation2019). Limited resources also heighten SMEs’ level of risk aversion, which is a distinct innovation barrier, where ‘incremental innovation through smaller improvements’ is preferred over radical innovation (Nil Gulari & Fremantle, Citation2015, p. 558). Such restrictions determine that SMEs may be more inclined toward a more time-efficient alternative to understanding how DT and a design-led approach may support their innovation needs. Communicating DT’s ability to support innovation by encouraging experimentation and risk-taking opportunities can be more efficiently delivered through external short-term ideation workshops (e.g., Heck et al., Citation2018) or design sprints (e.g., Bordin, Citation2022). When DT is introduced in off-site interventions or non-work environments to SMEs, it allows for a better focus on innovative processes and activities (Lockwood et al., Citation2012).

More importantly, it must be acknowledged that such external facilitation should focus on demonstrating how DT applies to SMEs’ R&D and innovation activities. Especially for SMEs in the creative industries, an additional challenge is to show the relevance of undertaking R&D activities for their businesses. In a survey conducted with 625 creative industries organisations in the UK, it was found that 38% of respondents deemed R&D activities as ‘not relevant to their business activities’ while 15% claimed that there is ‘no need for R&D’ (Bird et al., Citation2020, pp. 18–19). The authors propose that the barrier to encouraging innovation in creative industry practitioners can potentially be addressed by 1) introducing the mindset behind DT, displaying how DT is applied to R&D and design-led innovation and 2) showing how this approach is relevant to the type of non-linear activities and projects carried out in their industries. In the next sub-section 1.1, the authors will first discuss how the DT mindset is applied to R&D and design-led innovation. This is followed by an overview of innovation in the creative industries, highlighting the context and scope of the present study.

1.1. Increasing innovation capacities through the DT mindset

1.1.1. The DT ‘mindset’

A continued dialogue on what defines Design Thinking is perhaps worthwhile; however, it is not the intent of this study to attempt to formulate and offer a new definition of the concept. The literature has already established that there is currently no consensus definition of DT that is widely accepted (Nakata & Hwang, Citation2020, Liedtka, Citation2015). This study aims to focus on communicating the traits that frame the concept of DT as a way of propagating and benefiting from it (Zheng, Citation2018). In introducing and facilitating the adoption of the concept, the study essentially focuses on communicating the DT mindset attributes for effective and successful implementation of design-led innovation (Vignoli et al., Citation2023).

This study draws on Dosi et al. (Citation2018) definition of mindset, which refers to a ‘set of attitudes, opinions, beliefs and behaviours that characterise an individual, a group, or an organisation, mostly developed by experience’ (p. 1992). In achieving innovation, DT ‘blends an end-user focus with multidisciplinary collaboration and iterative improvement’ (Meinel et al., Citation2011, p. xiv). DT is social in nature, and innovation resulting from it would always lead back to a human-centric perspective, acknowledging the values and needs of people (Meinel et al., Citation2011). The DT mindset also describes designers’ cognitive strategies and approaches in formulating problems and generating solutions (Cross, Citation1992). These core groundings echo the early works of DT that are rooted in overcoming the impossible and wicked problems, through ‘new integrations of signs, things, actions and environment that address the concrete needs and values of human beings in diverse circumstances’ (Buchanan, Citation1992, p. 21). In a study that investigates the adoption of DT’s mindset for innovation with non-designers, it was proposed that ‘putting people at the center of the innovation challenge,’ a key element of User-Centred Design (UCD), was regarded as ‘the most valued mindset attribute’ (Groeger et al., Citation2019, p. 5).

An empirical approach toward classifying the DT mindset has identified 11 constructs that primarily show the UCD approach behind DT. Among the constructs include being empathetic toward people’s needs and context, being inquisitive and open to new perspectives and learning, and having a desire and determination to make a difference (Schweitzer et al., Citation2016). A more recent conceptualisation of the DT mindset outlines nine attributes including empathy, collaboration and diversity, learning-oriented, experimentation, critical questioning, uncertainty and risk, abduction, creative confidence, and optimism (Vignoli et al., Citation2023). This multidimensional conceptualisation summarises previous works on the DT mindset constructs, based on an extensive literature review and empirical analysis. The present study will therefore adopt these nine attributes in exploring how the DT mindset can be introduced to support individual innovation capacities.

1.1.2. Individual innovation capacities

A review of the different facets that influence individual innovation has shown that the DT mindset can be used to nurture individual characteristics that play a key role in innovativeness, such as confidence and fear of failure (Standing et al., Citation2016). In the DT mindset, creative confidence and working with uncertainties and risks describe designers’ approach toward innovation (Vignoli et al., Citation2023). It relates to designers’ articulation of how they ‘possess or seek to improve in the way they think, feel and emote in their practice’ which ‘determines how they will interpret and respond to situations’ (Sobel et al., Citation2019, 1696). This combination of both ‘divergent and convergent thinking’ helps designers identify the various aspects of users’ needs and values (Brenner et al., Citation2016, p. 3). It is also suggested that in terms of organisational-related innovation competencies, personal development and values including improved empathetic mindset and leadership skills can also be developed using the DT mindset (Carlgren et al., Citation2014).

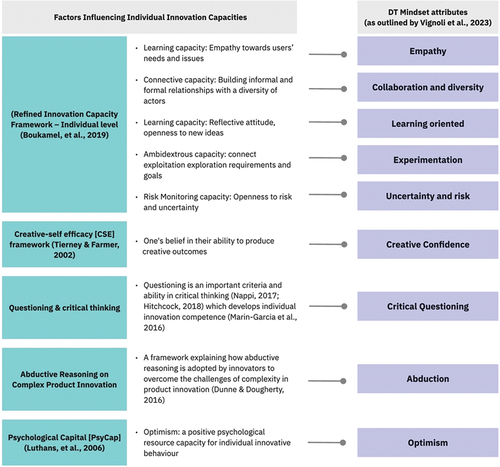

maps how each DT mindset attribute can be used to address different factors that may lead to the increase of individual innovation capacities. Based on this, the authors posit that instilling the DT mindset in individuals is one of the ways that can nurture individual innovativeness, thus supporting an industry’s overall innovation capacity. As much as a top-down macro approach may boost the scale of innovation for an industry or region, it is equally valuable to investigate how a bottom-up approach, such as focusing on an individual’s strength can increase innovation capacities. According to Carlgren et al. (Citation2014), increasing individual employees’ innovation capacity is a critical factor that contributes toward the overall organisation’s innovation capabilities. This bottom-up approach resonates well with the structure and resources of smaller organisations such as SMEs, where innovation is focused on building individual innovation capacities, as opposed to focusing on organisational innovation as practiced by larger counterparts. With an industry that is made up mostly of SMEs such as the Welsh creative industries, such an approach would fit the current effort of increasing the overall industry’s development.

Figure 1. A mapping of the factors influencing individual innovation capacity on the DT mindset attributes (Boukamel et al., Citation2019; Dunne & Dougherty, Citation2016; Hitchcock, Citation2018; Luthans et al., Citation2006; Marin-Garcia et al., Citation2016; Nappi, Citation2017; Tierney & Farmer, Citation2002).

1.2. Innovation in the creative industries of Wales

Researchers and policymakers of different economies including the UK have focused on constructing new strategies to address the ongoing debate about embedding innovation in the development of the creative industries (Mateos-Garcia & Bakhshi, Citation2016). This is partly due to the heightened awareness that innovation for the creative industries encompasses the industries’ societal and cultural growth potential and impact on the economy (Gerlitz & Prause, Citation2021; Gohoungodji & Amara, Citation2022). The UK’s creative industry has demonstrated its strength as ‘an engine of economic growth’ (Department for Media, Culture and Sport, Citation2023, p. 4). It is acknowledged that not all creative clusters in the UK grow the same way, particularly for creative challengers such as the capital of Wales, Cardiff, which may experience rapid growth and ‘are on track to become central nodes within the UK’s creative geography’ (Garcia et al., Citation2018, p. 7).

As opposed to traditional innovation, innovation for the creative industries is not bounded by the introduction of new technologies, systems, and processes (Benghozi & Salvador, Citation2016). The non-linear form of innovation is not limited to having inventions as inputs and market success as outputs (Wijngaarden et al., Citation2019) and intensifies the need for a different approach to stimulate innovation. From the perspective of creative industry workers, innovation is defined as ‘a continuous recombination of new and existing elements’ (Wijngaarden et al., Citation2019, p. 392), which may not fit the standardised approaches and strategies for increasing innovation capacities. It is, therefore, more relevant for the creative industries to approach innovation through the lens of design, as design-led innovation does not focus only on ‘introducing new technologies’ but ‘facilitates the adoption of new meanings’ and creates ‘new markets’ (Klein et al., Citation2021, p. 5).

In the context of Wales, it is estimated that 99% of the overall industry consists of SMEs or micro-organisations with employees numbering less than 50 people (Fodor et al., Citation2021). Further, freelancers make up a very large proportion of the overall Welsh creative industries, numbering over 40,000 individuals (Komorowski & Lewis, Citation2020). Increasing the innovation capacities of the Welsh creative industries relies heavily on addressing the challenges and barriers to innovation and increasing the accessibility toward design-led innovation approaches. A recent UK Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded programme, Clwstwr, focusing on cultivating innovation in the media sector of the Cardiff Capital Region, looked to address the barriers faced by micro-organisations by providing support in training and funding for Research and Development activities (Clwstwr, Citationn.d.). Over the course of 5 years (2018–2023), Clwstwr was shown to increase both the number of innovative outputs generated and the innovation capabilities of Cardiff.

Taking the experience that the authors and their organisation have gained from delivering the R&D training and support in Clwstwr, this paper presents the authors’ exploration into how the DT mindset can be introduced to individual creative industry practitioners, in the effort of further contributing toward the overall innovation capacities of the Cardiff Capital Region and Wider Wales. The research is enabled through a new consortium, Media Cymru, that seeks to increase innovation capacities for the creative industries of Wales (Cymru, Citationn.d.). In Media Cymru, the support focuses on supporting innovation for the emerging creative industries, largely consisting of smaller creative organisations that support other companies and organisations across the region as well as internationally. Based on the measures of different innovation maturity models (Inków, Citation2019), this industry possesses a lower level of maturity, where emerging innovative practices can still be nurtured to cultivate a higher level of innovation maturity in the future. This study is therefore configured around the research question: How can we use a UCD approach to determine the DT mindset attributes that resonate with creative industry practitioners and nurture their innovation capacities?

2. Method

This study investigates a UCD intervention that embeds the nine DT mindset attributes as identified by Vignoli et al. (Citation2023) to introduce a design-led innovation approach for the creative industries. This section will outline the details of the first set of training delivered by UCD experts to Wales-based creative industry practitioners (n = 27).

2.1. Research settings

The training was conducted within a design and research consultancy space and facilitated by a UCD expert with more than 20 years of experience in the product and service design industry and academia. It was co-facilitated by a senior designer with 7 years of experience in UCD and the service design industry. This training series is part of a funded opportunity under Media Cymru that aims to support innovative practices in the creative industries of Wales and address the barriers to innovation for micro-organisations and freelancers. Written consent was obtained from the participants before the start of the training for data collection purposes and was granted ethical approval by PDR Ethics Committee, Cardiff Metropolitan University to conduct all research activities (e.g., interview, observation and reflective sessions). All research activities were conducted by Author 1 who was not involved in the facilitation and delivery of the training.

2.2. User-centred design training + DT mindset

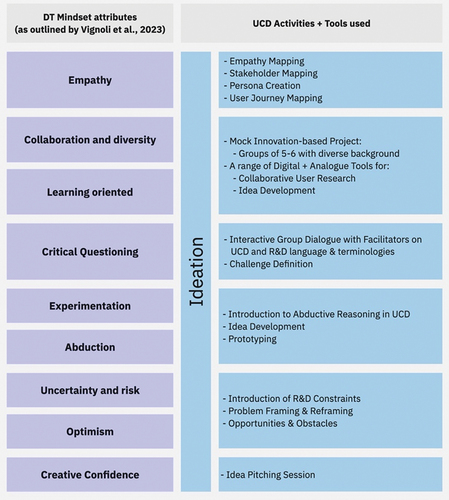

Participants were introduced to the UCD approach for R&D and design-led innovation through an exploration of different user research tools and techniques, while engaging and collaborating with other creative practitioners. The training structure was intended to provide hands-on interactive and collaborative learning opportunities. The nine DT mindset attributes were embedded in the training, as shown in .

2.2.1. Attribute 1 – empathy

Empathy in UCD includes understanding users’ needs and designing products or services based on their responses, interactions, and what would be of value to them. The training presented how empathising with target users, or target audiences in the case of the creative industry, is a process of problem identification and definition (Kim et al., Citation2023). This influences how ideas and solutions are developed. User research tools to promote empathy as listed in were used in different activities to better communicate the value of empathy. More importantly, the training emphasised how ideas should rarely be developed based on the creator’s personal preferences, as users’ needs and values are central to the practice of UCD. As an important element that shapes DT’s fundamental concept, this attribute is nurtured throughout different activities and tools designed in the training.

2.2.2. Attributes 2 and 3 – collaboration and diversity and learning-oriented

The format of the training combined interactive discussions between facilitators and participants and collaborative group activities. Participants were divided into groups of 5 to 6 people with diverse backgrounds and skills in the creative industries (e.g., age, ethnicity, industry experience, neurodiversity, and creative field). A combination of a digital whiteboard tool (Miro), as well as other analogue tools such as flipcharts, post-it notes, and sketches on the whiteboard, were used as collaborative design tools throughout the training to allow mutual learning and knowledge sharing. It was identified that a ‘shared cause’ may enhance and drive a collaborative mindset (Maciel & Fischer, Citation2020). Each group explored the understanding of the collaborative mindset in pursuing innovation through collaborative user research processes and ideation techniques that allow practice-based learning.

2.2.3. Attribute 4 – critical questioning

Interactive two-way discussions in the training encouraged the exploration of critical questioning. Critical inquiry relates closely to how critical thinkers approach a problem, by probing ‘into traditional beliefs’ and ‘challeng[ing] received dogmas and doctrines’ (Schafersman, Citation1991). A session was designed to debunk the current perceptions of concepts and terminologies including innovation and sustainability, as well as how terms such as ‘users’ and ‘ideas’ are viewed through the lens of UCD. It is intended that critical questioning, or the practice of viewing and reviewing simple concepts through multiple perspectives or layers, enabled participants to adopt these techniques to approach any future projects. As part of a mock innovation project, participants embarked on a critical enquiry phase of defining the challenge at hand and identifying potential opportunities and obstacles within the scope of the project.

2.2.4. Attributes 5 and 6 – experimentation and abduction

The concept of experimentation in design was introduced through ideation activities as part of the mock innovation project, as well as in interactive discussions between facilitators and participants. Its iterative nature in testing new ideas, processes, or systems, to identify what does and does not work (Thomke, Citation2003) plays a fundamental role in problem-solving and innovation activities (Thomke, Citation1998). Abduction, a type of design reasoning and iterative process that ‘experimentally frames and reframes’ a problem and solution (Dorst, Citation2019, p. 120), was also introduced to better articulate the importance of testing and trying out solutions, reducing anxiety around not getting it right the first time. Participants collaboratively explored and developed their ideas in their assigned groups, and exercised the process of iteration, experimentation, and applying abductive reasoning in the prototyping creation activity.

2.2.5. Attributes 7 and 8 – uncertainty and risk and optimism

The culture of working with uncertainties, risks, and different possibilities was introduced to participants throughout the mock innovation project. It is proposed that a project can be inspired by a problem or an opportunity, and ‘a set of mental constraints’ can act as an initial framework to kick off the project (Brown & Wyatt, Citation2010, p. 33). It is intended that this will motivate participants to be willing to approach a project with an optimistic view of learning from any mistakes, failures, or shortcomings. We exposed how the concept of framing and ‘reframing problems iteratively’ in working with uncertainties and risks ‘promotes the acceptance of changing goals and not knowing the outcome in advance’ (Carlgren & BenMahmoud‐Jouini, Citation2022, p. 54). This included an ideation brainstorming activity that specifically explored all possible opportunities and obstacles related to ideas.

2.2.6. Attribute 9 – creative confidence

Creative confidence was nurtured by incorporating several activities that allowed participants to present and pitch their ideas as a means of practicing both the visualisation and articulation of ideas and potential solutions. The collaborative element throughout the activities is intended to enhance the participants’ confidence in taking creative leaps in developing ideas and in the decision-making processes involved in R&D. At the end of the activities, participants were provided with a platform to pitch their ideas in a pitching session designed for collaborative learning.

2.3. Participants

The participants consisted of creative industry practitioners, with backgrounds ranging from TV and video production to music and theater. The majority were based in the Cardiff Capital Region with some representation from across Wales. Under Media Cymru, an open call for funded training opportunities was broadcast to all creative industries’ practitioners based in Wales to support their R&D activities. Twenty-seven applications were successful and supported to attend the training. The participants were split into two training groups according to whether they had any self-declared prior experience in non-design R&D and individuals who are new to R&D. Training for both groups ran across 2 weeks in January 2023. Both groups received the same format of training delivery, type and flow of activities. provides an overview of the participants for each respective creative industry background.

Table 1. Overview of the training participants and their industries.

2.4. Instrumentation, data collection, and data analysis

2.4.1. Data collection methods

2.4.1.1. Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews were held several weeks after the completion of the training to gain participants’ feedback on their overall experience. Interview sessions were only held with all participants from the smaller group, Group 1 (n = 10). Sessions were conducted via online conferencing (n = 9) and an e-mail interview (n = 1). The interview protocol is included in our supplementary material (Appendix A).

2.4.1.2. Reflective open-ended questioning

While interviews provide a deeper insight into participants’ overall experience, it is equally important to gain the immediate feedback of participants, where influences from other external factors could be minimised as much as possible. Therefore, we opted for reflective open-ended questioning, held on the final day of the training. This method was selected as it promotes a ‘better free recall, over and above the provision of detail’ (Nicholas et al., Citation2015, p. 72) and allows participants to reflect on their experience. As this reflection session was designed as part of the training, the same platform was used for this session to maintain the flow of activities. Therefore, facilitators used a digital whiteboard (Miro) to share the reflective open-ended questions with participants. Three short prompts focusing on their learning and understanding of innovation were used. To maintain consistency, these same questions were also used for the semi-structured interviews with Group 1. These prompts are included in our supplementary material (Appendix B). This activity was done with the larger group (Group 2). Participants did not engage in any form of discussion and wrote their anonymous answers individually on physical postcards. These were then submitted in a ‘post-box’ (n = 17) before they left the training venue.

2.4.1.3. Non-participatory observation

To analyse the long-term impact of the training on the practice and mindset shift of participants, non-participatory observation was conducted several months after the completion of the training. Three participants from Group 1 and five participants from Group 2 were successful in gaining funding from Media Cymru to undertake a media innovation feasibility study of their own (n = 9). For these successful applications, one-to-one consultations were held with UCD designers and researchers to support the participants’ R&D journeys. These sessions were observed by a non-participatory researcher, and any references made by participants relating to their learnings or experiences from the training were noted. Verbatim quotations were recorded as ‘rich and thick verbatim descriptions of participants’ and are valuable to support the findings (Noble & Smith, Citation2015, p. 35).

2.4.2. Data analysis methods

We approached the analysis using a reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) approach, with the multidimensional conceptualisation of the DT mindset framing the central framework of how themes were generated from the datasets. Using RTA, themes are not pre-determined and are developed from identified codes and ‘patterns of shared meaning underpinned by a central organising concept’ (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021a, p. 3). Such an approach is mediated by the researcher’s engagement with the data, their experience and training in design research and their core understanding of the DT mindset conceptualisation. With this, codes may ‘evolve to capture the reflexive researcher’s deepening understanding of the data’ (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021a, p. 3). Compared to the use of a codebook in ‘coding reliability’ thematic analysis, or a structured coding framework used in ‘codebook’ thematic analysis, RTA’s coding process is open and organic; fully embracing the researcher’s values and skills in the process (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021b). As opposed to using measures to minimise bias, researchers’ subjectivity is central to RTA and is crucial for making sense of the dataset.

A pseudonymied dataset was generated to identify and analyse how the intervention has impacted participants’ mindsets toward R&D and innovation. The dataset involves multiple data sources including intelligent verbatim transcripts from semi-structured interviews, reflective answers, and descriptive field notes from observations. For each data source, the analysis started with the first step of data familiarisation. Next, codes were identified and generated. This coding process considered the interpretation of the researcher, determining how participants’ way of describing their experiences, learnings, and takeaways from the training connect to their understanding of the DT concept and ‘mindset.’ The codes were then developed into key themes that describe the collective dataset. Themes, here, refer to patterns of shared meaning underpinned by a central concept (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021b). Triangulation of data from multiple sources that were used in this process is used ‘to develop a comprehensive understanding’ and ‘test validity through the convergence of information from different sources’ (Carter et al., Citation2014, p. 545). In reporting the findings, the following coding is used for all participants (n = 27):

Group 1’s interview responses (Participants 1–10) are coded as I1, I2, I3;

Group 2’s reflective answers (Participants 11–27) are coded as R11, R12, and R13; and

Both groups’ quotes from the observation (Participants 1–27) are coded as O1, O2, O3, and so forth.

3. Findings

The analysis has produced six themes that encapsulate the key takeaways of participants’ learning from the UCD training. Although it was designed to adopt a hands-on, interactive learning format in introducing how DT works in R&D and innovation (as outlined in Section 2.1), we are particularly interested in identifying how such practical experience influences participants’ understanding of DT and their mindset toward innovation. Each theme below is discussed with supporting excerpts from the pseudonymised dataset. Findings from interview responses and reflective answers are discussed under ‘Immediate Reflections,’ while observation quotes are discussed under ‘Long-term Impact.’

3.1. Challenge the idea of ‘ideas’

3.1.1. Immediate reflections

Almost a third of the participants discussed the impact of the training on their understanding and conceptualisation of ideas. Before the training, they were ‘quite protective over creative ideas [they] come up with’ (I6) as ideas were previously considered particularly valuable to oneself (I2). The mindset that ideas can be ‘expandable’ (I6) and ‘[broken] down [to] offer alternative opportunities’ (R13) has allowed participants to experiment, explore, and iterate their ideas and ‘be open to change and talk about [their] own ideas’ (I2) with others. They acknowledged that the training’s imparted message that ideas can come in a dozen, quickly and cheaply has helped ‘taken the pressure off ideas and onto iteration’ (R14). I4 stated that:

It definitely changed my way of thinking, and it allowed me to not be so difficult on myself right at the beginning. In the past, [I would think] that I needed to innovate and come up with a great idea and there was a lot of pressure. [Now it is about] allowing yourself time to have some rubbish ideas and just flush them and see what happens. That has definitely changed the way I think about innovation.

3.1.2. Long-term impact

O-24 shared that they applied the ideation technique learnt for a brainstorming session conducted as part of applying for a new contract: ‘ … in my studio, I cleared the wall and got the post-it notes up!.’ They emphasised their approach toward ideas, being mindful to come up with as many ideas as possible, taking pressure off finding the ‘right’ idea before moving forward.

3.2. Frame failure as an option

3.2.1. Immediate reflections

In contrast to the notion that failure is not an option, more than a third of the participants have specified that they now recognise failure as ‘part of the process’ toward innovation (I1, I5) and that the training has given a positive outlook of what failure means (I2, I4). It addressed their fear of failure in projects as they learnt ‘constructive ways of identifying failures and solutions for [them]’ (R18). Bold statements of ‘constant failure is excellent’ (R24), and ‘failure is sometimes success’ (I9) have shown an increase in participants’ confidence in framing failure as an option in approaching ideas, projects, and innovation. The learnings have ‘broadened [their] thought processes’ to be ‘more comfortable exploring novel approaches and ideas’ (R12). I9 has also begun to recognise a more sophisticated understanding of failure as a learning step toward an innovation opportunity:

Sometimes you are going through a process, and you did not reach the end goal that you wanted to, but you have learned something from it.

I have quite a strong relationship to a fear of failure, but it was described in a way that made it really clear what it meant. It was put in a context and framework that made sense.

3.2.2. Long-term impact

Compared to the previous theme, there were no explicit mentions of framing failures captured in the observed sessions.

3.3. Learn to trust the process

3.3.1. Immediate reflections

It was evident that the training has changed the thinking behind approaching innovative projects with nearly half of participants referencing the importance of process in innovating. The introduction of user research and its processes has nurtured a mindset that ‘process is more important than product’ (R23). They understood that ‘there are needs and practices that need to be explored deeply and research has to be more thorough’ (I10) before delving straight into prototyping or focusing on solutions (R11). It is through ‘demystifying the process’ (R14, R24) and ‘immediate practice of the method’ (R17) in the training that allowed participants to visualise and understand the process of approaching any innovative project from inception to delivery (I3, R16, R18, R21). I2 reflected on their learning about the UCD process:

… Just starting from a problem and building from it allowed you to avoid assumptions. I love the methodology, asking questions, and essentially using information to help shape products. [These are] practical ideas in how we can find solutions.

Previously I would have always envisioned that I’d need to have a finished or a very near finished product to be able to show somebody, whereas in reality it [can also be] a concept of a potential product.

3.3.2. Long-term impact

Three participants have been noted to reference their learnings in the observed sessions. O21 and O25 both emphasised their understanding of the importance of user research before delving into any technicalities or potential solutions. O15 has referenced the training, explaining how they now learn to allow themselves to trust the process:

… remembering the double diamond and divergent thinking, we have been looking at a lot, all very varied [options] … I think that’s a good thing. We just looked at as much as possible and went down a few routes that maybe we did not expect to go down. There are lots of different threads … and there’s a thread which has actually gone really well …

3.4. Acquire innovation self-efficacy

3.4.1. Immediate reflections

More than a third of the participants’ innovation self-efficacy has reportedly increased, including their confidence and motivation to use the innovation concept that they learnt ‘as an integral part of the ideation process’ (R21). According to I1, learning about the processes, the new perspective of innovation and how it works has increased their confidence in using innovation:

I have a far greater grasp now of being able to communicate ideas and figure out how to present them. I have been given the key thought processes to work through and know [that] obviously it is not always gonna [sic] be straightforward.

3.4.2. Long-term impact

It was explicitly mentioned by three participants that practical knowledge, including a better grasp of applying and using the language and terminologies learnt in the training, has helped them in the process of writing applications and securing funding for innovation-based projects (O15, O24, O25).

3.5. Collaboration = learning

3.5.1. Immediate reflections

About a third of the participants have reported that the arrangement of working in groups of diverse backgrounds, skills, and industries has nurtured collaborative learning opportunities. This includes allowing them to step outside their usual field, interests and skills (I4, R24). I9 shared that the:

Different ethnicities and everything was eye-opening to see … the diversity in the kind of innovation’s spectrum or field … being in that program with people from all different backgrounds and who are ready to go, I felt inspired to keep following my path, my inspiration and my motivation because I’m seeing people in real-time pursuing that.

3.5.2. Long-term impact

For this theme, there were no explicit mentions captured around collaborative learning in the observed sessions.

3.6. Change the perception of innovation

3.6.1. Immediate reflections

About a third of participants have reported a shift in how they see innovation. Participants’ perception of innovation before the training includes how innovation is ‘tied up to ideas’ (I4), ‘needs to equal originality’ (R11) and that it can also be defined by how ‘geniuses or someone with (several) degrees create something and they become rich’ (I9). Participants pointed out that they ‘did not really know what innovation means in the context of what [they are] doing’ (I3), and that the training has changed their understanding and perspective of innovation (I6, I8, R17, R20). R11 described how the training showed another side of innovation that is ‘more of a process of answering a question,’ which aligned with R14’s remarks that the training has ‘given new emphasis on [the] constant challenge[s] of own idea[s] and conclusions.’ It was effective in giving a new understanding of innovation, including the formation of a ‘personal theoretical definition of innovation’ (I9) and ‘think of innovation as something that comes later’ (I4).

3.6.2. Long-term impact

The continuous impact of the training regarding the change of mindset toward innovation was noted by O14 who explained their newfound view of innovation now:

Innovation can sometimes be like it is fickle to chase it. Sometimes just having research developed, [make sure it is] robust and feasible, that is enough. That is innovation itself.

4. Discussion

Our findings provide insights into which DT mindset attributes are meaningful to creative industry SMEs. These attributes have been identified to effectively encapsulate the value of applying DT for R&D and design-led innovation that applies to their industries. When introducing the DT concept for the first time to non-design practitioners, design facilitators should focus on the attributes that resonate with non-design practitioners. Based on our analysis, it was identified that certain learnings were retained longer than others. These include the understanding of benefitting from the generation of many ideas for iteration and development, as opposed to focusing and working on getting that one ‘right’ idea. The training’s message about the importance of delving into ‘research processes before solutions’ also came across as something that remained in participants’ mindsets. Similarly, some participants have acknowledged the value of having been equipped with the language and terminologies that they can now use for innovation-focused ventures. Most importantly, the new-found perspective of what innovation is, which is considered a useful motivator for pursuing innovation, also remained one of the longer-term impacts of the training.

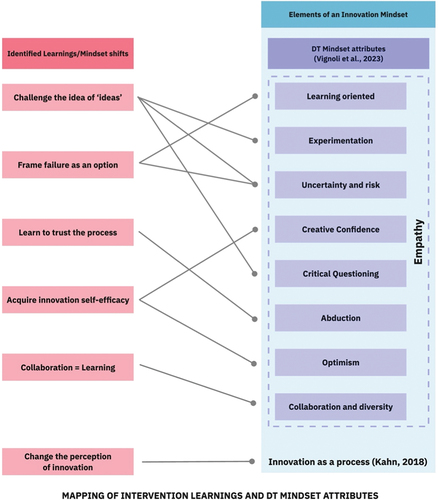

While all DT mindset attributes have been proposed to address different factors that could influence and increase individual innovation capacities (see ), in this section we will highlight and discuss how the identified ‘mindset shifts’ that occur after the training may potentially be effective in supporting individual innovation capacities in the creative industries. As argued in this paper, innovation for the creative industries is not bounded by the introduction of ‘newness’ and is not limited only to inventions and market outputs. Standardised approaches focusing on organisational innovation to increase an industry’s innovation capacities are deemed less suitable for the creative industries, more so in the context of an emerging industry majorly consisting of creative individuals and SMEs. We began our study with a proposal that increasing innovation capacities in the creative industries of Wales should start with a bottom-up approach, focusing on leveraging individual skills and capabilities. We posit that design-led innovation is a suitable approach as it echoes the creative industries’ innovation style and needs, where the focus is on internalising innovation and its characteristics in individual members to support the innovation ambitions of the creative sector (Kahn, Citation2018). Hence, focusing on the DT mindset attributes to introduce the concept can be one of the ways to encourage the implementation of design-led innovation by creative industry practitioners.

presents our mapping of the identified ‘mindset shifts’ and the DT mindset attributes, proposing that the combination of interactive and collaborative UCD activities and discussions (as outlined in Section 2.2) presented in the study could be an effective way to communicate and address the DT attributes that frame design-led innovation. Activities across our training were structured based on the core element of UCD, which is empathy, where the focus is on empathising toward users or audiences and generating outputs that address their values and needs. We, therefore, propose that empathy is an overarching element that encompasses all other DT mindset attributes. Structuring the UCD training to follow a hands-on approach of engaging with practical methods and processes of design-led innovation has also nurtured an important element of an innovation mindset, where the concept of ‘innovation’ itself is perceived in a new light.

4.1. Elements of an innovation mindset

Innovation can be viewed as an outcome, a process, or a mindset (Kahn, Citation2018); however, this study shows that the training shifted participants’ pre-conceived perception of innovation from being outcome-driven or solution-focused to process-driven. The change in participants’ perception of innovation shows that the experience enabled participants to identify innovation as an iterative process, where the journey is just as important or if not more so than the intended destination. Having an innovation mindset is also about being aware that innovation is not an innate ability, but a learnable and developable skill and process which aligns with an individual’s growth, aspirations, and goals (McLaughlin & McLaughlin, Citation2021).

The ability to challenge the idea of ‘ideas’ describes the DT attributes of experimentation, critical questioning and working with uncertainty and risk. It has prompted participants to understand the value of sharing ideas with others to gain feedback and allow an idea to go into an experimental, iterative development phase such as a creative revision. In a creative revision for innovation, ideas are shared by creators to test, assess, and improve their potential. New information gained will stimulate ‘divergent thinking, expand cognitive schema, reveal new perspectives and reframe problems’ (Toivonen, et al., Citation2023, pp. 5–6). As opposed to the practice of ‘gatekeeping’ ideas, it was understood that for innovation, ideas can and should be critically challenged, questioned, and iterated collaboratively.

The mindset that ideas are not set in stone also encourages a different perspective of what an innovative outcome can be, and what failure is in the context of R&D and innovation. The shift of perspective from viewing failure as a negative connotation to framing failure as an option explains how participants gained a learning-oriented mindset embedded in uncertainty and risk. Such framing is important, as being resilient in the discovery, testing, and exploration phase early in the innovation process helps individuals to value the idea of learning from mistakes or shortcomings, and supports an individual’s productivity in innovative projects following a failure (Moenkemeyer et al., Citation2012). In the case of innovation for organisations, it is posited that failure is positioned as more than just a form of learning but encompasses ‘the incremental advancement’ or a ‘representation of admirable and appropriate effort’ (Smith et al., Citation2023, p. 992). Failure is embraced as an asset that is inherent and intrinsic to innovation (Hartley & Knell, Citation2022; Smith et al., Citation2023) and the capacity to redefine and work around it can be one of the crucial factors that help increase an individual’s innovation capabilities.

Being able to learn and tolerate uncertainties also allows individuals to embark on R&D journeys with a learn-as-you-go mindset, understanding that innovation is not a linear process, and ideas may venture into unexpected directions and possibilities. It is by learning to trust the process that one can endure innovation’s ‘nonlinear cycle of divergent and convergent activities.’ It describes the DT attribute of abduction, where there is a clear understanding that one needs to endure iterative processes and layers of experimentation, while also trusting one’s instinctive guts in search of solutions. This resilience is crucial in approaching innovative projects that ‘require a high level of persistence to overcome setbacks’ (Gerber et al., Citation2012, p. 3).

The training has also nurtured innovation self-efficacy which resonates with the attributes of creative confidence and optimism. It is about having the belief, self-trust, and confidence to follow through any innovation process, and being optimistic that each process is valuable and there is always something to learn from it. An increase in motivation toward revisiting innovation-based projects and undertaking innovation ventures has also demonstrated a positive outlook toward one’s ability and capabilities. In the case of innovation for creative industries SMEs, understanding that Collaboration = Learning may be a useful way forward in approaching innovation ventures, especially for an industry that has been identified to work in silos and mainly relies on internal sources for innovation (Bird et al., Citation2020). This shift has shown how the format and structure used for the training is a good example of how we can encourage collaboration and diversity to nurture innovation capabilities.

5. Practical implications

The findings of our study present several important parameters that need to be considered in the process of introducing DT to non-design practitioners. In an attempt to facilitate the understanding of how the concept works in design-led innovation, it is implied that design facilitators should focus on communicating the mindset attributes that have been identified to resonate with non-design practitioners. We posit that focusing on these mindset attributes and exposing the way designers think and frame their reasoning surrounding design processes and decisions will deliver the message of why DT is a valuable approach for innovation in non-design industries.

In our study, we applied a UCD approach in our training to demonstrate how DT can be implemented in R&D and innovation processes. Alongside the exposure of different tools, methods, and practical processes to participants, we focused on instilling the DT mindset attributes via facilitated discussion and interactive activities to effectively communicate the concept to non-design practitioners. The mindset shifts that occurred post-intervention suggest that this hands-on approach allows non-design practitioners to understand the purpose of design toolkits and methods, and how they might fit into their R&D development process, which may support a better implementation of DT in their industries. More importantly, the intervention’s ability to nurture a different perception of innovation, where it is identified as a process, may be regarded as an important takeaway that can encourage confidence and support individual innovation capacities. Future design facilitators may apply the proposed structure to introduce and encourage DT implementation in other industries, especially industries which can benefit from a non-linear innovation approach.

6. Conclusion

This study offers a way forward in cultivating innovation practices in the creative industries, where the bottom-up approach of empowering individuals is suggested as a suitable method to increase the innovation capacities in an industry highly driven by creative SMEs. It outlines a UCD framework that can be implemented to introduce design-led innovation approaches to non-design practitioners, including those who are new to R&D. Our study presents the DT mindset attributes that need to be considered when introducing the concept, which have been identified as effective in showing the value of DT in R&D and innovation.

Our study has limitations that also need to be addressed. While non-participatory observation was put into place to analyse the longer-term impact of the training toward the practice of participants, it would be beneficial to also track how these mindset shifts impact participants’ practice while engaging in new R&D ventures, innovation-based projects or their day-to-day work. Future research may include expanding our work to include a further assessment of the long-term impact of DT-focused interventions toward non-design practitioners’ practice. This may be done through a mixed-method longitudinal study that keeps track of participants’ journeys over several years, or by following the process undertaken for a specific project in which they were involved. The measures of impact, however, should consider the non-linear nature of innovation in the creative industries, and the constraints of SMEs and individual practitioners. While the focus is on leveraging individual innovation capacities, future research can attempt to track the impact of DT-focused training on several larger groups of creative industry individuals, which may be able to provide more insights into how the DT mindset attributes influence mindset shifts of industry practitioners.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (101.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2024.2383410

Additional information

Funding

References

- Altman, M., Huang, T. T., & Breland, J. Y. (2018). Peer reviewed: Design thinking in health care. Preventing Chronic Disease, 15, 15. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.180128

- Bell, S. J. (2018). Design thinking + user experience = better-designed libraries. Information Outlook, 22(4), 4–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.34944/dspace/96

- Benghozi, P. J., & Salvador, E. (2016). How and where the R&D takes place in creative industries? Digital investment strategies of the book publishing sector. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 28(5), 568–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2015.1122184

- Bird, G., Gorry, H., Ropers, S., & Love, J. (2020). R&D in the Creative Industries Survey. UK Government Department for Culture, Media & Sports. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/rd-in-the-creative-industries-survey

- Bordin, S. (2022). Design sprint: Fast problem-solving through collaboration. ICSOB ’22: 13th International Conference on Software Business, Bolzano, Italy (Vol. 3316). https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3316/industry-paper3.pdf

- Boukamel, O., Emery, Y., & Gieske, H. (2019). Towards an integrative framework of innovation capacity. The Innovation Journal, 24(3), 1–36. https://serval.unil.ch/resource/serval:BIB_61EF194278EB.P001/REF.pdf

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021a). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern‐based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021b). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Brenner, W., Uebernickel, F., & Abrell, T. (2016). Design thinking as mindset, process and toolbox. In W. Brenner & F. Uebernickel (Eds.), Design thinking for innovation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26100-3_1

- Brown, T., & Wyatt, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. Development Outreach, 12(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1596/1020-797X_12_1_29

- Buchanan, R. (1992). Wicked problems in design thinking. Design Issues, 8(2), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511637

- Carlgren, L., & BenMahmoud‐Jouini, S. (2022). When cultures collide: What can we learn from frictions in the implementation of design thinking? Journal of Product Innovation Management, 39(1), 44–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12603

- Carlgren, L., Elmquist, M., & Rauth, I. (2014). Design thinking: Exploring values and effects from an innovation capability perspective. Design Journal, 17(3), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.2752/175630614X13982745783000

- Carlgren, L., Elmquist, M., & Rauth, I. (2014). Exploring the use of design thinking in large organizations: Towards a research agenda. Swedish Design Research Journal, 11, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.3384/svid.2000-964x.14155

- Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545–547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

- Chia, A. J. H., & Lee, J. J. (2019). Banking outside-in: How design thinking is changing the banking industry. Proceedings of The International Association of Societies of Design Research (IASDR).

- Clwstwr. (n.d.). Where ideas thrive. Retrieved May 15, 2024, from. https://clwstwr.org.uk

- Cross, N. (1992). Research in design thinking. In N. Cross, K. Dorst, & N. Roozenburg (Eds.), Research in design thinking (pp. 3–10). Delft University Press.

- Cymru, M. (n.d.). Leading media innovation in Wales. Retrieved October 15, 2023, from https://media.cymru

- Department for Media, Culture and Sport. (2023). Creative industries sector vision: A joint plan to drive growth, build talent and develop skills. UK Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/creative-industries-sector-vision

- Dorst, K. (2019). Design beyond design. The Journal of Design Economics and Innovation, 5(2), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2019.05.001

- Dosi, C., Rosati, F., & Vignoli, M. (2018). Measuring design thinking mindset. DS 92: Proceedings of the DESIGN 2018 15th International Design Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia (pp. 1991–2002).

- Dunne, D. D., & Dougherty, D. (2016). Abductive reasoning: How innovators navigate in the labyrinth of complex product innovation. Organization Studies, 37(2), 131–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615604501

- Fischer, S., Lattemann, C., Redlich, B., & Guerrero, R. (2020). Implementation of design thinking to improve organizational agility in an SME. Die Unternehmung, 74(2), 136–154. https://doi.org/10.5771/0042-059X-2020-2-136

- Fischer, S., Redlich, B., Lattemann, C., Gernreich, C., & Pöppelbuß, J. (2019). Implementation of design thinking in an SME. ISPIM Conference Proceedings, Florence, Italy (pp. 1–14). The International Society for Professional Innovation Management (ISPIM).

- Fodor, M. M., Komorowski, M., & Lewis, J. (2021). Clwstwr creative industries report No 1.2: Report update. The size and composition of the creative industries in Wales in 2019. https://clwstwr.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-02/Creative%20Industries%20Report%20No%201.2_Final_compressed.pdf

- Garcia, J. M., Klinger, J., & Stathoulopoulos, K. (2018). Creative nation: How the creative industries are powering the UK’s nations and regions. London: Nesta.

- Gerber, E., Martin, C. K., Kramer, E., Braunstein, J., & Carberry, A. R. (2012). Work in progress: Developing an Innovation Self-efficacy survey. 2012 Frontiers in Education Conference Proceedings, Seattle, Washington, USA (pp. 1–3). USA: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE.2012.6462435

- Gerlitz, L., & Prause, G. K. (2021). Cultural and creative industries as innovation and sustainable transition brokers in the Baltic sea region: A strong tribute to sustainable macro-regional development. Sustainability, 13(17), 9742. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179742

- Gohoungodji, P., & Amara, N. (2022). Historical roots and influential publications in the area of innovation in the creative industries: A cited-references analysis using the reference publication year spectroscopy. Applied Economics, 54(12), 1415–1431. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2021.1976388

- Gray, C. M. (2016, May). “It’s more of a mindset than a method” UX practitioners’ conception of design methods. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 4044–4055).

- Groeger, L., Schweitzer, J., Sobel, L., & Malcom, B. (2019, June). Design thinking mindset: Developing creative confidence. Conference of the Academy for Design Innovation Management 2019: Research Perspectives In the era of Transformations, London, UK (pp. 1401–1413). Sydney, Australia: University of Technology Sydney.

- Hartley, J., & Knell, L. (2022). Innovation, exnovation and intelligent failure. Public Money & Management, 42(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2021.1965307

- Heck, J., Rittiner, F., Meboldt, M., & Steinert, M. (2018). Promoting user-centricity in short-term ideation workshops. International Journal of Design Creativity & Innovation, 6(3–4), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2018.1448722

- Heck, J., Rittiner, F., Steinert, M., & Meboldt, M. (2015). Impact dimensions of ideation workshops on the innovation capability of SMEs. Proceedings of Continuous Innovation Network (pp. 400–409).

- Hernández-Ramírez, R. (2018). On design thinking, bullshit, and innovation. Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts, 10(3), 2–57. https://doi.org/10.7559/citarj.v10i3.555

- Hitchcock, D. (2018). Critical thinking. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/critical-thinking

- Inków, M. (2019). Measuring innovation maturity–literature review on innovation maturity models. Informatyka Ekonomiczna, 1(51), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.15611/ie.2019.1.02

- Johansson‐Sköldberg, U., Woodilla, J., & Çetinkaya, M. (2013). Design thinking: Past, present and possible futures. Creativity and Innovation Management, 22(2), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12023

- Kahn, K. B. (2018). Understanding innovation. Business Horizons, 61(3), 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.01.011

- Kim, H. J., Yi, P., & Ko, B. W. (2023). Deepening students’ experiences with problem identification and definition in an empathetic approach: Lessons from a university design-thinking program. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 15(3), 852–865. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-03-2022-0083

- Klein, M., Gerlitz, L., & Spychalska-Wojtkiewicz, M. (2021). Cultural and creative industries as boost for innovation and sustainable development of companies in cross innovation process. Procedia Computer Science, 192, 4218–4226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.09.198

- Komorowski, M., & Lewis, J. (2020). The covid-19 self-employment income support scheme: How will it help freelancers in the creative industries in Wales. https://www.creativecardiff.org

- Kupp, M., Anderson, J., & Reckhenrich, J. (2017). Why design thinking in business needs a rethink. MIT Sloan Management Review. http://mitsmr.com/2eSnTHA

- Liedtka, J. (2015). Perspective: Linking design thinking with innovation outcomes through cognitive bias reduction. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(6), 925–938. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12163

- Liedtka, J., & Ogilvie, T. (2012). Helping business managers discover their appetite for design thinking. Design Management Review, 23(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7169.2012.00165.x

- Lockwood, J., Smith, M., & Mcara-Mcwilliam, I. (2012). Work-well: Creating a culture of innovation through design. 2012 International Design Management Research Conference, Boston, USA. Design Management Institute. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1055.9043

- Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2006). Psychological capital: Developing the human competitive edge. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195187526.001.0001

- Maciel, A. F., & Fischer, E. (2020). Collaborative market driving: How peer firms can develop markets through collective action. Journal of Marketing, 84(5), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242920917982

- Magistretti, S., Pham, C. T. A., & Dell’era, C. (2021). Enlightening the dynamic capabilities of design thinking in fostering digital transformation. Industrial Marketing Management, 97, 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.06.014

- Marin-Garcia, J. A., Andres, M. A. A., Atares-Huerta, L., Aznar-Mas, L. E., Garcia-Carbonell, A., González-Ladrón de Guevara, F., & Watts, F. (2016). Proposal of a framework for innovation competencies development and assessment (FINCODA). Working Papers on Operations Management, 7(2), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.4995/wpom.v7i2.6472

- Mateos-Garcia, J., & Bakhshi, H. (2016). The geography of creativity in the UK. Nesta.

- Matović, I. M. (2019). Design thinking as innovative management method. RAIS Journal for Social Sciences, 3(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3549448

- McLaughlin, L., & McLaughlin, J. (2021). Framing the innovation mindset. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 18, 083–102. https://doi.org/10.28945/4793

- Meinel, C., Leifer, L., & Plattner, H. (2011). Design thinking: Understand-improve-apply (pp. 100–106). Springer.

- Mesa, D., Renda, G., Iii, R. G., Kuys, B., & Cook, S. M. (2022). Implementing a design thinking approach to De-risk the digitalisation of manufacturing SMEs. Sustainability, 14(21), 14358. MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114358

- Moenkemeyer, G., Hoegl, M., & Weiss, M. (2012). Innovator resilience potential: A process perspective of individual resilience as influenced by innovation project termination. Human Relations, 65(5), 627–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726711431350

- Nakata, C., & Hwang, J. (2020). Design thinking for innovation: Composition, consequence, and contingency. Journal of Business Research, 118, 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.038

- Nappi, J. S. (2017). The importance of questioning in developing critical thinking skills. Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin, 84(1), 30.

- Nicholas, M., Van Bergen, P., & Richards, D. (2015). Enhancing learning in a virtual world using highly elaborative reminiscing as a reflective tool. Learning & Instruction, 36, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.12.002

- Nil Gulari, M., & Fremantle, C. (2015). Are design-led innovation approaches applicable to SMEs? DS 82: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education (E&PDE15), Great Expectations (pp. 556–561). Design Teaching, Research & Enterprise, Loughborough, UK.

- Noble, H., & Smith, J. (2015). Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evidence Based Nursing, 18(2), 34–35. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102054

- Pham, C. T. A., Magistretti, S., & Dell’era, C. (2022). The role of design thinking in big data innovations. The Innovation, 24(2), 290–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2021.1894942

- Radnejad, A. B., Sarkar, S., & Osiyevskyy, O. (2022). Design thinking in responding to disruptive innovation: A case study. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 23(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/14657503211033940

- Schafersman, S. D. (1991). An introduction to critical thinking. https://www.smartcollegeplanning.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Critical-Thinking.pdf

- Schweitzer, J., Groeger, L., & Sobel, L. (2016). The design thinking mindset: An assessment of what we know and what we see in practice. Journal of Design, Business and Society, 2(1), 71–94. https://doi.org/10.1386/dbs.2.1.71_1

- Smith, W. R., Treem, J., & Love, B. (2023). When failure is the only option: How communicative framing resources organizational innovation. International Journal of Business Communication, 60(3), 976–999. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488420971693

- Sobel, L., Schweitzer, J., Malcom, B., & Groeger, L. (2019). Design thinking mindset: Exploring the role of mindsets in building design consulting capability. Conference of the Academy for Design Innovation Management 2019: Research Perspectives In the era of Transformations, London, United Kingdom (pp. 1695–1701). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43683-022-00093-0

- Standing, C., Jackson, D., Larsen, A. C., Suseno, Y., Fulford, R., & Gengatharen, D. (2016). Enhancing individual innovation in organisations: A review of the literature. International Journal of Innovation and Learning, 19(1), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIL.2016.073288

- Teso, G., & Walters, A. (2016). Assessing manufacturing SMEs’ readiness to implement service design. Procedia CIRP, 47, 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2016.03.063

- Thomke, S. H. (1998). Managing experimentation in the design of new products. Management Science, 44(6), 743–762. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.44.6.743

- Thomke, S. H. (2003). Experimentation matters: Unlocking the potential of new technologies for innovation. Boston, USA: Harvard Business Press.

- Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1137–1148. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069429

- Toivonen, T., Idoko, O., Jha, H. K., & Harvey, S. (2023). Creative jolts: Exploring how entrepreneurs let go of ideas during creative revision. Academy of Management Journal, 66(3), 829–858. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2020.1054

- Vignoli, M., Dosi, C., & Balboni, B. (2023). Design thinking mindset: Scale development and validation. Studies in Higher Education, 48(6), 926–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2172566

- Wijngaarden, Y., Hitters, E., & V. Bhansing, P. (2019). ‘Innovation is a dirty word’: Contesting innovation in the creative industries. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 25(3), 392–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2016.1268134

- Zheng, D. L. (2018). Design thinking is ambidextrous. Management Decision, 56(4), 736–756. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-04-2017-0295