Abstract

Although the literature covers the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), well-being, and Global Public Goods (GPGs) extensively, there is very little work on connecting these with Southern concepts in order to make the underlying inspiration for policy processes truly inclusive. Hence, this paper focuses on how such links can be made. It argues in favor of linking the Ubuntu – ‘I am because we are’ – to modern ideas of well-being and African communitarian philosophy to GPGs. These two concepts of human well-being and the need to govern GPGs are intrinsically linked to the MDGs post 2015 and could help to make the MDGs truly inclusive.

1. Introduction

Many have concluded that the inception of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) was everything but inclusive. They were drawn up by the United Nations (UN), after an initial launch by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD-DAC Citation1996), the club of rich industrial countries, of its development goals. Only after the formulation of MDG8, dealing amongst others with trade, debt and aid issues, did the developing nations sign up for it. An unprecedented international consensus emerged, which has now been fully embraced by developing countries, and to which the numerous national and regional MDG progress reports testify.

Progress on the goals has been uneven and not all of them will be reached by 2015. Discussions have begun on the follow-up, the post 2015 period. The UN has carried out a consultative process and appointed a high-level panel of wise (wo)men from developing and developed countries which has published its findings (High Level Panel Citation2013). This is a multidisciplinary exercise where economics, law, philosophy, political science, and even psychology are involved. Theories of well-being (objective, subjective, and future well-being) and how to measure it play an important role, as well as ideas on governance and economic theories such as Global Public Goods (GPGs) and Global Commons. To do justice to the perspectives of all people, however, one should take into account not only Western philosophical concepts, but also indigenous concepts of development. Even though most developing countries have signed up to the MDGs, it does not necessarily follow that indigenous concepts were incorporated, as those countries were not involved in the drafting process. Moreover, the school of thought in Third World Approaches to International Law criticizes international law for not taking alternative thoughts from developing countries adequately into account. Or as Naicker (Citation2011, 456) puts it: ‘what is lacking is information on how different cultures and practices envision collective responsibility for human wellbeing’ (in the context of global sustainable development negotiations). An important attempt to incorporate indigenous ideas in the development debate is the (non-binding) Earth Charter (2000), which refers to ‘one human family and one Earth community with a common destiny’ (preamble). It calls for recognition ‘that peace is the wholeness created by right relationships with oneself, other persons, other cultures, other life, Earth and the larger whole of which all are part’. (Art 16)

Bhutan has successfully introduced a resolution in the UN General Assembly in 2011 to include the Buddhist concept of happiness in the post 2015 system.Footnote1 Ecuador and Bolivia promote the concept of ‘Buen Vivir’ (living well). As Gudynas (Citation2011, 1) indicates ‘it refers to alternatives to development emerging from indigenous traditions, and in this sense the concept explores possibilities beyond the modern Eurocentric tradition’.

Different conceptions of well-being inspired the Fitoussi, Sen, and Stiglitz report (Citation2009), commissioned by the Sarkozy Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, which considered both objective and subjective well-being as important. These individualistic ontologies in well-being and capability theory have, however, been criticized (Deneulin and McGregor Citation2010). Sen's idea of ‘living well’ has been modified by Deneulin and McGregor into ‘living well together’ which includes consideration of the social structure and institutions which enable people to pursue individual freedoms in relation to others. The underlying power structures and the reality of conflict cannot simply be changed by reasoning (some peoples' losses after all are other people's gains) and reasoning in itself rests on values. These meanings and values are constructed through our relationships in society. Humans are social and adapt their ideas through negotiations with others; what we deem valuable freedoms (capabilities) are not established at the individual level. Douglas and Ney (Citation1998) discuss personhood from a different perspective, criticizing utility thinking, the ‘homo economicus’ and the lack of ‘social personhood’ in Western social sciences which look primarily at rational individuals. ‘Culture is the selective screen through which the individual receives knowledge of how the world works, and how people behave. For humans, nothing is known from scratch, everything is transmitted through other persons, and they are not isolated influences’ (91) And:

Cultures incorporate their implicit agendas by framing selected issues, setting agendas, labeling and foregrounding, backgrounding, and fading out … if we allow for cultural diversity in the public sphere, we must acknowledge that there is bound to be systemic disagreement over fundamental principles. Whole social persons will not be able to resolve disagreement as easily as will the abstract, unsocial persons of the market model … . (124)

This article focuses on a non-western collective ontology: African philosophy and one of its main tenets of Ubuntu. The contribution of Africa to the international well-being debate post 2015 has been somewhat muted, though lively debates exist in African legal and philosophical journals. This article examines whether Ubuntu has a contribution to make to the academic well-being debate and if it should be considered in post MDG policy-making. To this end, the following questions will be addressed: What is Ubuntu and is it relevant as a living concept amongst (South) African people? Does Ubuntu withstand criticism of utopianism? Does Ubuntu offer more than human rights theory, and if so what? What political weight does Ubuntu have? If these are answered in the affirmative, what role can Ubuntu play in development theory, i.e. is there a link with GPGs? How can Ubuntu inform the post 2015 agenda?

2. What is Ubuntu and is it a relevant living concept amongst Africans?

Ubuntu is a South African word that is commonly associated with the Zulu/XhosaFootnote2 saying ‘umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu’: a person is a person through other persons.Footnote3 This proverb appears in other Southern African languages as well, sometimes referred to as Hunhu (Shona) or Botho (Sotho/Tswana). It also appears in Venda, Swahili, Tsonga, Shangaan, and in languages in Uganda (Broodryk Citation2002). The translation into Western philosophy is difficult, as Mokgoro puts it, ‘because the African world view is not easily and neatly categorized.., any attempt to define Ubuntu is merely a simplification of a more expansive, flexible and philosophically accommodative idea’ (Mokgoro Citation1997, 16). It can be called ‘humaneness’ (not to be equated with humanism which is fixed and not in motion) and ‘humaneness regards being or the universe as a complex wholeness involving multilayered and incessant interaction of all entities’ (Ramose Citation1999, 105). It can be summarized as ‘I am because we are and since we are, therefore I am’ (Mbiti Citation1990, 106). This represents a relational world view where nothing can be viewed in isolation; individuality is a relative concept that does not exist without the community (as well as the ecosystems and the spiritual world) of which the individual is part. Connecting this with capability theory, Cornell articulates this as ‘freedom to be together in a way that enhances everyone's capability to transform themselves in their society’ (Cornell Citation2005, 195–220). Ubuntu could thus be considered as a (Southern-) African concept of well-being.

Common (South) African sayings highlight other dimensions of this philosophy such as ‘the source and justification of all power is in the people’ and ‘we may go our own way, whenever urgent and vital issues arrive, we still have the obligation to come together and try and find a common solution’ (highlighting consensus politics); ‘if faced with a choice between wealth and the preservation of life of another human being, one should choose the life of the other’ (sharing goes above wealth) and ‘no single human being can be thoroughly and completely useless’ (e.g. the criminal, ill or handicapped are part of humanity); ‘God exercises vengeance in silence’ and ‘If it were not for God I would be dead by now’ (illness is also a spiritual affliction); ‘If God dishes you rice in a basket, do not wish to eat soup’ (acceptance of one's fate); and ‘no one shows a child the Supreme Being’ (spirituality is self-evident) (Mbiti Citation1990, 43, 205, 41, 29; Ramose Citation1999, 70, 98, 100; Coetzee and Roux Citation2002, 544).

Concepts similar to Ubuntu have significance not only in Southern Africa but also in the rest of Africa as is testified by, for example, Western African writers such as the Senegalese philosopher Diagne, who quotes the Akan saying ‘when a human being descends upon earth he lands in a town’ (Diagne Citation2009) or Wingo (Citation2008) who asserts that: ‘For the Akan, personhood is the reward for contributing to the community and the basis of the individual's moral worth is located in an independent source – a common humanity’. Mofuoa quotes the Nigerian (Bini) saying ‘a tree cannot make a forest’ (Mofuoa Citation2010, 281). African ethics are defined by Wiredu ‘as the observance of rules for the harmonious adjustment of the interest of the individual to those of others in society’ (Wiredu [1998] Citation2003, 337). Wiredu concludes that

in traditional Akan society it [Ubuntu] was so much and so palpably a part of working experience that the Akans actually came to think of life (obra) as one continuous drama of mutual aid (nnoboa). Obra ye nnoboa: Life is mutual aid, according to an Akan saying. (Wiredu [1998] Citation2003, 293; Ramose Citation2007, 350)

Gyekye cites the Akan proverb ‘Humanity has no boundary’ as the expression of unity or brotherhood of all human beings (Gyekye Citation2004, 98). Masolo (Citation2001) speaks of ‘communitarian theory indigenous to African culture’. Gade (Citation2011, 305) mentions the Swahili concept of Ujamaa, promoted by former President Nyerere of Tanzania, regarding all human beings as members of an extended family, an ‘African socialism’ based on harmony rather than class struggle.

Whether one can categorize a people and its philosophical outlook on a continent as vast as Africa with all its cultural differences is subject to debate. Ramose (Citation1999) defines Ubuntu as an African philosophy (see also Outlaw and Lucius Citation2010). Metz (Citation2007, 375) constructs it as an African moral theory, which Ramose finds a too limited concept. Metz defends himself, inter alia, that his (perceived) ‘Western’ analytical method does not exclude his theory from being African. However, Metz's concept does not include the metaphysical. The issue of Pan-Africanism is beyond the scope of this article, but suffice it to say that if any African concept relevant to the development debate is sought, Ubuntu seems to be well placed to be amongst them.

3. Criticism at Ubuntu: can it withstand it?

Criticism of the ‘misuse’ of Ubuntu for all kinds of purposes (business ventures and political expediency) or the romanticizing of tribal pre-colonial values (van Binsbergen Citation2001) abounds. In order to know whether Ubuntu can play a significant role in post 2015 development thinking, the criticism leveled at it is briefly reviewed.

3.1. Ubuntu is not universal and limited to Africans

Not all accounts of Ubuntu are mutually compatible. Some say the delineation of community in ‘we’ (I am because we are) is unclear (based on kinship, geography, ethnicity, and nationality?). Some ask (i.e. Jabuvu and Thompson and Butler): does it include non-Africans?Footnote4 In other words what is the relevance outside Africa? There seems to be no reason why Ubuntu should be limited to Africa merely because it emerged there, nor does it need to be an exclusively African idea (perhaps there are similar concepts in other cultures which Metz (Citation2007, 376), for example, acknowledges). The exclusion of a certain group, separating ‘us’ from ‘them’ (e.g. black from white), seems contradictory to the idea of interlinkage that is the essence of Ubuntu. One could counter this argument by asking what the universal application of Western philosophy is (see also Gade Citation2012).

3.2. Ubuntu has no relevance for today

Some argue that Ubuntu is linked to past rural village life and taken out of context; it is therefore an obsolete concept today. In this view, African philosophers like Ramose are imposing their own ideals on African culture. van Binsbergen (Citation2001, 71), for example, criticizes the current debate on Ubuntu as an idealized, largely intuitive, integrated, and unified academic concept as opposed to the ‘systematic, expert and loving reconstruction of African systems of thought’ that anthropologists use. My question would be whether that in itself is not a Western rationalist approach to science, dismissing a parallel intuitive approach to knowledge of other cultures that van Binsbergen himself defends. In another context, van Binsbergen argues that ‘wisdom’ from non-western traditions is complementary to ‘science’;

the lessons are implied to be worth giving, and taking, because they are claimed to capture something of the human condition in general … so in fact we are, with such wisdom texts, rather closer to scientific knowledge than is suggested by the inverted formula ‘subjective, a-rational, and, in its practicality, particularizing. (van Binsbergen Citation2008a, 82)

It is refreshing to see how African ethics … can be invoked as a vantage point from which to take a critical distance from Kant's rationalistic lack of social and humanitarian considerations. This points to another, largely unexplored way which the transcontinental connection in the context of African philosophy can take: the way in which African philosophy can contribute significant new, identifiably African, viewpoints and modes of analysis to globally circulating philosophical … debates. (van Binsbergen Citation2008b, 12)Footnote5

Eze (Citation2010, 140) therefore reproaches van Binsbergen's polemic approach and calls his essay ‘a residue of colonial reason’. Whether African intellectuals speak for themselves or for their culture as a whole is a question that could be asked of Western scientists too. Here, I agree with Bewaji: he reproaches van Binsbergen's ‘afrophilophobia’ (fear of African philosophy) and comments: ‘Where did philosophers like Locke, Hobbes and Rousseau get their ideas of social contract? Was it latent in the views of their societies or a distillation of concepts present in nebulous form in their cultures ( … )?’ (Bewaji and Ramose Citation2003, 381). Perhaps one could argue that opposition to ‘romanticist’ Ramose is aimed at the idea that pre-colonial African life was better because it was based on Ubuntu; it would be better to submit that pre-colonial African life was based on a different set of ideas (the merit of which is subjective).

Wood (Citation2007) (see below) also sees Ubuntu as merely an instrumental value that was useful for survival at that time and thereby seems to concur with van Binsbergen. Metz in my opinion successfully defies Wood in referring to several contemporary African intellectuals (Wiredu, Tutu, Nkondo, and Khoza) who use this concept in seeking for a more humane market economy, thus making it a current concept and not merely historical.

3.3. There is no homogeneous African philosophy (that could inform post 2015 agenda)

Eze tries to bridge the arguments of the proponents and the opponents. He contends that concerns about dislocating the concept from its historical experience are only true if one takes consensus as the core of Ubuntu, but not if one sees the relationship between the individual and community as one of creative dialogue and conversion, leading to new insights (Eze Citation2008, 114). In his book Intellectual history of contemporary South Africa, he makes a distinction between the essentialist approach of Ubuntu, rooted in an unchangeable (but unprovable oral) past, and a performative approach of Ubuntu which asks what Ubuntu can do in the present-day context. He chooses the latter by postulating that national identity necessarily needs a narrative to overcome differences and that Ubuntu can be such a narrative. He, however, qualifies this by stating that Ubuntu needs to be located in its context, that is, different communities may have a different interpretation. He thus grants Ubuntu its status as a living philosophy, but does question a homogenized African Ubuntu identity. He claims to take a middle position between proponent Ramose and Ubuntu critics like van Binsbergen who sees Ramose as essentialist (Eze Citation2010).

Eze's questioning of a homogenized African philosophy might be countered by asking whether there is such a thing as Western/European philosophy; despite all its divergence in cultures and differences between North and South Europe, it seems taken as a given. Eze does, however, point to the fact that denying Africans their own philosophy is ‘smacking of intellectual racism’ (Eze Citation2010, 127).

3.4. Human rights (dignity) are (more) relevant for post 2015 and encompass Ubuntu

Some compare Ubuntu to seemingly similar concepts that can be found in Western philosophical thinking, such as dignity and respect for human rights, and argue that Ubuntu does not add anything new. Human rights should be part of the post 2015 agenda, not Ubuntu. This, however, negates the fact that community-based thinking is radically different from individual (Western) based thinking. Van Niekerk (Citation2007), for example, posits that one's basic moral reason for action is only one's self-development. Metz responds to what he calls ‘Van Niekerk's autocentric conception of Ubuntu’ and argues that our basic moral reasons are other-regarding and not merely self-regarding. Metz also posits harmony as a goal in itself, regardless of whether this is constructed as good for the individual's dignity (Metz Citation2007, 373–374 and 382–383). Metz's position makes sense, as it seems rather odd to want to construct Ubuntu as derived from individual self-development if that is exactly the tenet it tries to defeat: life is mutual aid, not individual pursuance. One could ask whether it is possible to come to the same universal truths from a different starting position, taking either self-development or the value of relationships as the basis of human life. Perhaps one theory without the other does not offer the complete picture. Ubuntu does not need to replace Western values (although some may think it should). Ubuntu seems rather an essentially different way of approaching the problems a society faces, global or local, that the world could benefit from and is already moving toward, in its conceptualization of GPGs (see para 6).

3.5. Ubuntu inspires cultural relativism; it is not beneficial to upholding human rights in a post 2015 agenda

In its debates on one of the first reports worldwide concerning the post 2015 agenda, the Advisory Council for International Affairs (2011) decided against a reference to Ubuntu out of fear of cultural relativism.Footnote6 It is a well-known debate in human rights theory that cultural relativism may undermine human rights. This may explain some of the hesitance within the human rights community to embrace Ubuntu. Wood argues amongst others that Ubuntu is a cultural value that has emerged in the context of the necessity of African societies at the time: ‘that there are objective truths …, and that cultural variations in ethical values result from the fact that different cultures perceive those truths partially’ (Wood Citation2007, 341). He then appeals to the objectivity of reason to establish those truths. He sees no difference in Ubuntu and values such as human dignity and therefore prefers the latter. He thereby implicitly assumes that for Africans (and the rest of the world), human dignity in the Western sense of reasoning is a term they also feel more comfortable with than their own terminology. At the same time, he acknowledges that cultures may beneficially influence one another. Could Ubuntu, rather than undermining human rights, complement it?

3.6. Ubuntu is not implemented and is therefore irrelevant for development

Skeptics of Ubuntu (such as Van Kessel, in conversation) claim that African countries, the African Union, and even proponent South Africa, are not adhering to their own Ubuntu concept. Therefore, they assert that such a concept does not exist and is an idealistic fantasy, or ideology, invented by so-called African philosophers. They cite criticisms of the South African elite enriching themselves, arms sales to repressive regimes such as Syria and poor governance in Africa. At the same time, they acknowledge that South Africa has also become a donor country and is an active participant in peacekeeping missions.Footnote7 Cornell (Citation2008, 8) confirms that ‘(Ubuntu) is belittled as an ethic that black South African's do not live up to’. As Ramose argues, it is precisely the lack of Ubuntu that has created the current political reality in Africa. He pleads for a return to traditional constitutional thought instead of Western style democracy that is adversarial in nature (Ramose Citation1999, 98). Even if (South) Africa is only partially adhering to Ubuntu, it does not make the idea itself redundant. Christian and enlightenment ideals after all inspired many a European government, without them always living up to their ideals. Ubuntu is, other than an ideal, a way of representing life, a perspective on life that is different from the European one.

3.7. Ubuntu is communist and not compatible with Western development theory

Some (such as Van Kessel, in conversation) oppose the perceived egalitarian notion of Ubuntu and equate it with communism or at least think it is not compatible with Western notions of achieving excellence by competition. Ubuntu is rather a complementing concept, a counterbalance in a competitive world that struggles to address issues such as access to resources, intellectual property rights, and redistributive justice. It may be said that communal societies stress cooperation over competition; Ubuntu merely acknowledges that we are part of the others and the others are part of us.

3.8. Ubuntu is anti-communist and does not empower people to improve their position

Marxists reject Ubuntu, because it would not take into account the ‘class struggle’. As McDonald remarks, they have largely ignored the concept, which he sees as a missed opportunity (McDonald Citation2010, 149). Empowerment is an important notion in development thinking (including post 2015). Solidarity is ultimately empowering as in the Ubuntu mind you cannot exist without the other.

3.9. Ubuntu undermines justice and the rule of law, important concepts for the post 2015 agenda

Skeptics criticize the use of Ubuntu in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). van Binsbergen claims that this was based more on the Christian idea of forgiveness than any traditional concept; all traditional sages were excluded from the process. (The question here is whether the culture of a people is constituted by traditions or rather a general awareness amongst them, in which case there are also modern sages.) This attempt to mollify apartheid injustice may dangerously conceal real conflicts, just like it may conceal class differences (van Binsbergen Citation2001, 76). Krog (Citation2008) dissents, arguing ‘this thing called reconciliation … forgiveness (is) … part of an interconnectedness-towards-wholeness’. Others are also of the opinion that, especially in the sphere of restorative justice – as opposed to retributive justice – there might be scope for further explorations of the Ubuntu concept. Eze explores the question of when forgiveness constitutes a denial of justice and concludes that Ubuntu is ‘a responsive nationalistic ideology’ and it ‘offers a common ground where different memories ( … ) potentially converge for a new memory and consciousness’ (an aim which is expressly acknowledged in the interim constitution). He quotes Chukwudi Eze in saying that the TRC process is ‘a moral and ethical suspension of justice for an equally moral and ethical, more universal aim of societal transformation’ (Eze Citation2010, 171–172).

The above criticisms on the (mis)use nowadays of the concept of Ubuntu do not defeat the concept itself. The fundamental criticism of Ubuntu as a philosophy furthermore seems to deny the relational world viewers (be it African or others) a place in the debate. Perhaps, in a dualistic model, both have their value, in balancing ‘the self’ and ‘self in relation to the other’. Because it is at the conceptual level that true changes first take place, before they translate into the ‘real’ world, I therefore continue to explore the usefulness of Ubuntu for global thinking, especially in relation to GPGs.

4. The application of Ubuntu in South African foreign politics

In assessing elements for the post 2015 agenda, it is important to know whether South Africa, as the leading economy of the continent, attaches any political weight to Ubuntu. There is evidence that South Africa is beginning to project its idea of Ubuntu not only in domestic policies, but also abroad, especially in the G77 and the BASIC group (Brazil, South Africa, India, and China). Lagging behind the other BASIC countries economically, it is not so much its weight in world economics that matter, but whether it manages to operationalize its African leadership. Indeed as an observer puts it: ‘If there is Ubuntu in South African politics, this is the time to encourage it.’ (Martins Citation2011, 2). Not only did the South African government explicitly found its diplomacy on Ubuntu (Building a better world: the diplomacy of Ubuntu Citation2011), but it also consistently refers to it in its exchange with embassies around the world:

Ubuntu reflects the belief that it is in our national interest to also promote and support the positive development of others. South Africa is multifaceted, multicultural and multiracial, and embraces the concept of Ubuntu to define who we are and how we relate to others; We adhere to the following values: human rights, democracy, justice, international peace, reconciliation, and the eradication of poverty and underdevelopment. (South African Embassy Citation2011, 5)

Here, we see the explicit link made with human rights, civil and political as well as economic and social rights.

Its public diplomacy magazine UBUNTU, while referring to the basic principles that should underlie the post 2015 agenda, makes a direct link between Ubuntu and the old South–South solidarity idea in which

development must be an expression of own aspirations, civilization and determination … Ubuntu diplomacy must mean a multifarious approach to diplomacy, pursuing humanistic goals globally … making people the key focus … and including people's voices. South Africa would need to raise this point in the African Union and G77+China platforms until 2015. (Zondi Citation2014, 24–25)

South Africa's Humanity's Team promotes consciousness about Ubuntu, calling it ‘Africa's ancient gift of Oneness to the world’ and the ‘indigenous knowledge of Africa’ and ‘we find ourselves today: at the threshold of THE ERA OF UBUNTU, an idea whose time has come’. The movement is present in 100 countries. One of its aims is the proclamation of a Global Oneness Day by the UN (Pieterse Citation2014). The death of Mandela gave attention to Ubuntu an extra impetus (e.g. the Ubuntu walk in honour of Madiba, November 2013 (Jiyane Citation2014)). In his article ‘Human Rights: Central to South Africa's Foreign Policy’, Deputy Minister Ebrahim declares in the context of the importance of the MDGs that ‘consolidation of South Africa's democracy over the last 19 years is accompanied by efforts to regenerate respect for human values’, which is why ‘the UN Women's regional representative is established in Pretoria’ (Ebrahim Citation2013). In the article titled ‘South Africa, BRICS and Global Governance’, the Foreign Minister is quoted as having

recognized the catalytic role that the G20 … could play … to show leadership in working together, based on the values … [of] the UN Charter … , this is again derived from and linked to the core values of our foreign policy notably the philosophical concept of Ubuntu to define who we are and how we relate to others. Ubuntu is the very essence of our being. (Sooklal Citation2012, 37)

At the end of 2013 South Africa's diplomacy established its Ubuntu Radio, echoing American public diplomacy.

5. Ubuntu: the grandmother of Human Rights

If Ubuntu is to be an informative principle for the post 2015 agenda, one needs to address the question: Does Ubuntu add to human rights theory? South African jurisprudence shows that according to African judges it does. Jurisprudence also shows that Ubuntu is not merely an obsolete philosophy from the past, but has practical relevance. It will be argued that Ubuntu can serve both as overarching principle as well as specifically informing a possible cluster on institution building/rule of law.

Judges link their invocation of Ubuntu to the interim constitution of South Africa (1993) in which a reference was made to Ubuntu, which was omitted in the final constitutionFootnote8 for unclear reasons.Footnote9 Nevertheless, Minister Fransman (Citation2013, 46)Footnote10 and South African judges refer to ‘the spirit of Ubuntu’ underlying the constitution. A debate has evolved about whether Ubuntu can be a founding principle of law (Cornell Citation2012, 326). Judge Mokgoro (Citation1997, 10) claims that the values of Ubuntu can provide the South African law with the necessary indigenous impetus, as the law is under the scrutiny of the constitution. In her view, Ubuntu is in line with the founding values of democracy established by the new constitution and the bill of rights. Two cases support this view: in Albutt versus Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation as well as Azanian's People's Organisation versus TRC, the court respectively held that South Africa's participatory democracy was in fact an ancient principle of traditional African methods of government; and in the latter that amnesty under the TRC (which was Ubuntu inspired) was a crucial component of the negotiated settlement itself and could thus not be challenged by the political party AZAPO (Bennett Citation2011, 32).

The Ubuntu literature stresses that rights also entail duties, a concept that we also find in the African Charter of Human Rights (‘duties toward his family and society, the state and other legally recognized communities and the international community’, Article 27 (1)). Closely related is the notion of sacrifice for group interests. Ubuntu cannot be translated into an individual right, because it goes beyond the notion of individual entitlement (whereas human dignity can be linked to an individual). As McDonald (Citation2010, 148) puts it ‘unlike the notion of self-interest that lies at the heart of liberal moral philosophy, Ubuntu world views are not driven by such individualism and appear fundamentally at odds with the market's homo economicus’. Metz and Gaie (Citation2010, 273–290) point out the different consequences of Ubuntu versus Kantian and Utilitarian moral theory in relation to, inter alia, property (equal distribution), criminal justice (restorative), medical confidentiality (transparent to group members), family life (duty to wed and have children), and moral education (developing personhood). Ubuntu according to Metz and Gaie is relating to others in a positive way, seeking out community (or living in harmony) combined with a moral obligation to be concerned with the good of others and defining oneself as a member of a group. Or as Mokgoro (Citation1997, 8) states: ‘the original conception of law not as a tool for personal defense, but as an opportunity given to all to survive under the protection of the order of the communal entity’. Some of these features become apparent in South African court cases discussed below. For an overview of other cases, see also Cornell and Muvangua (Citation2012).

Judge Mokgoro claims that in a hierarchy of legal principles, Ubuntu stands higher than ‘human dignity’, considered to be the mother principle of law. Mokgoro says:

Human dignity is usually said to be the mother of all rights … in that respect I would regard Ubuntu as the grandmother of all rights … ; to me Ubuntu goes even deeper than human dignity … we regard our beingness as related to the beingness of others, those we associate with, the community we live in … it is others who regard you with humaneness. (Interview, Wewerinke Citation2007, 37)

In State versus Makwanyane,Footnote11 the relationship with human dignity is underlined:

An outstanding feature of Ubuntu in a community sense is the value it puts on life and human dignity. The dominant theme of the culture is that the life of another person is at least as valuable as one's own. Respect for the dignity of every person is integral to this concept. During violent conflicts and times when violent crime is rife, distraught members of society decry the loss of Ubuntu. (Para 225)

In this judgment of the constitutional court, the concept was used to justify the abolition of capital punishment ‘to be consistent with the value of Ubuntu (our commitment) should be a society that wishes to “prevent crime … (not) to kill criminals simply to get even with them” (para 131)’.

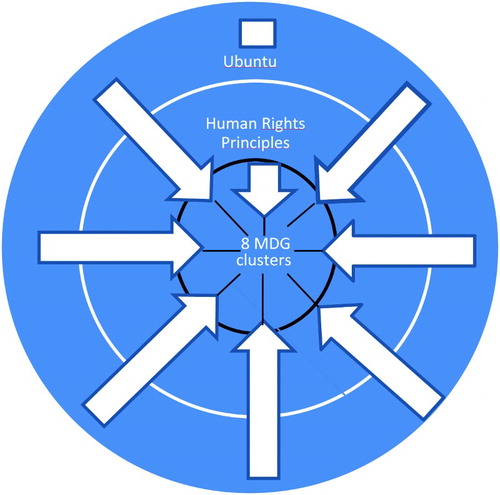

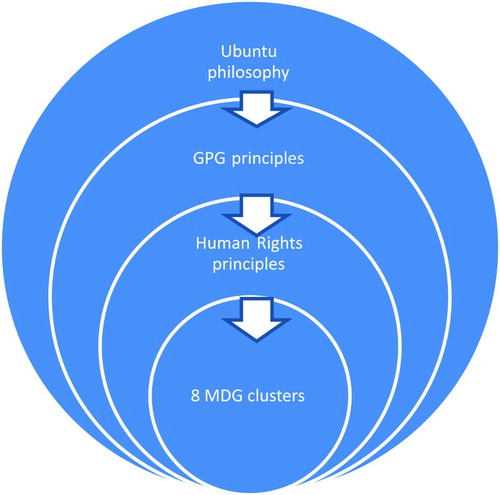

One could thus say that Ubuntu can function as a founding principle underlying the new development agenda, in the same way that human rights principles, such as participation, non-discrimination, and accountability, can ().

More concretely, Ubuntu stresses the principle of (a) social justice, (b) restorative justice in criminal and family law, (c) fair (relational) administrative proceedings, and (d) social justice in property rights.

In Khosa versus Minister of Social DevelopmentFootnote12 judge Mokgoro states (para 74):

And (para 52): ‘The right of access to social security ( … ) for those unable to support themselves ( … ) is entrenched because as a society we value human beings and want to assure that people are afforded their basic needs. A society must seek to ensure that the basic necessities of life are accessible to all if it is to be a society in which human dignity, freedom and equality are foundational.’ Interestingly, this South African case, in which a non-citizen Mozambican permanently resident in South Africa was afforded certain welfare grants, touches upon and operationalizes the idea of the ‘global social floor’, which appeared in the 2010 Millennium Review Summit Declaration. The Global Social Floor also coincides with the idea of minimum levels in economic and social rights. As Wewerinke (Citation2007, 43) concludes, ‘this is where the “greater environing wholeness and human individuality” may have really been thought of as connected. As soon as Ubuntu starts to penetrate arbitrary, but institutionalized lines that separate people (and thereby touches on kinds of inequality that are to be seen as unfairness, precisely because of the arbitrariness they are based upon) such as nationality, health, gender, race etcetera, its potentials start to take definite form’.Sharing responsibility for the problems ( … ) of poverty equally as a community represents the extent to which wealthier members of the community view the minimal well-being of the poor as connected with their personal well-being and the well-being of the community as a whole. In other words, decisions about the allocation of public benefits represent the extent to which poor people are treated as equal members of society.

The emphasis of Ubuntu on social harmony leads to restorative justice rather than retributive justice and is one of the central aims of the South African sentencing system, which upends the common law system aiming at retribution (Bennett Citation2011, 35). He points at the Traditional Courts Bill (2008), the Child Justice Act (2008), and two more court cases in this regard as well as a family law case describing consensus seeking in family meetings for the prevention and resolution of disputes (Bennett Citation2011, 43).

In administrative law, fair and respectful administrative action and the relational nature of rights are highlighted, moving beyond the common law conception of rights as strict boundaries of individual entitlement (Bennett Citation2011, 36–40, for case law).

In property law, Ubuntu is also used to combat social injustice. In Port Elizabeth Municipality versus Various OccupiersFootnote13 Judge Sachs says: ‘In a society founded on human dignity, equality and freedom it cannot be presupposed that the greatest good for many can be achieved at the cost of intolerable hardships for the few ( … ). The spirit of Ubuntu, part of the deep cultural heritage of the majority of the population suffuses the whole constitutional order. It combines individual rights with a communitarian philosophy. It is a unifying motif of the Bill of Rights, which is … a declaration in our evolving society of the need for interdependence, respect and concern. ( … ) Our society as a whole is demeaned when state action (of evicting people) intensifies rather than mitigates their (the poor's) marginalization.’

Other than asserting Ubuntu in relation to the Prevention of Illegal Evictions from and Unlawful Occupation of Land Act (PIE), the use of Ubuntu in private law as well as in contract law is limited (Bennett Citation2011, 40–41). While mention has been made of Ubuntu and/or equity in contracts, the courts have been reluctant to develop these norms any further; principles of legal certainty and private autonomy prevail: ‘a sad reflection on the law that provides ground rules for the economic structure of South Africa's fragmented and unequal society’ (Bennett Citation2011, 46). The question remains what an African legal system based entirely on Ubuntu would have looked like.

6. The correlation between Ubuntu and GPGs

After having concluded that Ubuntu is a living concept amongst Africans, which is not merely utopian, but has political and legal relevance, this article will now link it to the MDGs. In a previous article (Van Norren Citation2012), I argued that the definition of GPGs as goods from which no one can be excluded (non-exclusion) and whose use by one is not at the expense of others (non-rivalry), should imply that no-one may be excluded. The main argument for this is the fact that technically it may well be possible to exclude people in the future from common resources such as sunlight or oxygen, but it is not desirable. This normative GPG concept was derived from a definition of Kaul and Mendoza (Citation2003, 92) of GPGs as those goods that are public in consumption, and in their distribution of benefits and decision-making. Even for those who believe in a more restricted notion of public goods, the overriding GPG idea is one of interdependence and a need for a cooperative framework for their management, as markets and polycentric governance cannot solve these issues on their own.

This notion of normative GPGs comes close to Ubuntu with its idea of mutual responsibility (after all Wiredu stated ‘life is mutual aid’). Thus (dominant) European philosophy, with its deeply rooted individualism and roots in social contract theory, is reaching the same point of reflection that African philosophy takes as its basic starting point. The difference between the several schools of GPGs seems to be that some see a form of cooperation in the spirit of Ubuntu as necessary only in certain restricted areas such as climate, financial stability, or food security,Footnote14 while others believe in an Ubuntu interdependence in all areas of life. The Western social contract school takes the competitive human being and homo economicus as its starting point and the African Ubuntu school the cooperative human being; neither excludes the other but merely seem to take it as the exception rather than the rule. Examples of cooperation in Ubuntu are shosholoza (‘work as one’, team work) and collective enterprises, stokvels, in which profits are equally shared and may never be gained at the expense of the other (Louw Citation1998). The logical conclusion seems to be that debates over GPGs must engage with and give space for the notions of development that underpin other cultural systems.

A first attempt has been made by the Ubuntu declaration for a just and sustainable world economy of 2009 (under the patronage of Desmond Tutu and Cherie Blair) highlighting issues of, inter alia, financial system reform, green economy, women's economic empowerment, growth and jobs as well as climate change and sustainability, calling for a holistic response. It claims as its inspiration ‘the concept of Ubuntu … the spirit of cooperation which is so vital as we tackle these global issues ( … )’. Unfortunately, the statement remains vague and the document does not elaborate on the philosophical underpinnings. It does, however, call for a ‘new economic paradigm … to be shaped from the perspective of human rights and environmental responsibilities’ and which ‘should draw on the wisdom of our world's religions and the stewardship practices of indigenous people’ (Rights and Humanity Global Leaders Congress Citation2009, 14–15).

In ‘Reflections on Botho as a resource for a just and sustainable economy’, Mofuoa elaborates on this idea, specifically targeting Africa as a continent (Mofuoa Citation2010). However, Ubuntu stresses our interconnectedness as humans (and nature) and thus development in Africa is intrinsically linked with that of other parts of the world. Underdevelopment in Africa seems to rather be a consequence of a lack of Ubuntu in the rest of the world in an artificial separation of continents and countries that are responsible ‘for their own development’, even though Africa takes part in a globalized economy. As UNCTAD puts it in relation to the MDGs:

the fundamental problem is … not so much the lack of economic goals in the MDG framework, as the lack of a more inclusive strategy of economic development that could integrate and support its human-development ambitions ( … ) There will have to be a renewed emphasis on … reform of the international governance architecture to build coherence across trade, financial and technology flows in support of inclusive development. (UNCTAD Citation2010, 1, italics added)

7. Environmental GPGs and Ubuntu

Protection of the environment is paramount in the GPGs discussion. In the concept of Ubuntu, the environment is part of the communitarian concept of life. One way of making this connection is through the concept of seriti, which is translated as aura, dignity, personality or shadowFootnote15 (in my interpretation: the clearer the aura, the more dignity the person possesses or the longer the shadow you cast). Those who believe in it refer to seriti not only as a personal field, but also as ‘a field which connects all living beings’. According to Cornell ‘Ubuntu is associated with seriti, which names the life force by which a community of persons are connected to each other. In a constant mutual interchange of personhood and community, seriti becomes indistinguishable from Ubuntu in that the unity of the life force depends on the individual's unity with the community.’ She quotes Setiloane (Citation1976, 52): ‘it is as if each person were a magnet creating together a complex field. Within that field any change in the degree of magnetization, any movement of one, affects the magnetization of all’ (Cornell Citation2012, 331 and note 23). Behrens (Citation2014, 1 and 5) deducts from this belief a moral ‘considerability’ (responsibility) to include all things that are part of the web of life, including inanimate natural objects.

8. GPGs, MDGs, and Ubuntu

I have argued before that the MDGs should be seen as GPGs, goods that affect everyone and from which no one may be excluded (Van Norren Citation2012). The term Global Community Goods may reflect this better than GPG, in order to avoid the confusion with the word ‘public’, which to many denotes ‘provided by the state’. (Some prefer the term ‘global commons’ which strictly speaking deals with common resource pool management at a global level). Combining the MDGs with a GPG notion gives it an Ubuntu quality. Ubuntu in relation to the MDGs would then signify the wholeness and interrelation of the MDG concept; neither subject of the goals can be treated on its own.

Ubuntu is thus an overarching principle that can inform the clusters of goals and indicators (although also a Western result based management system that, however, may well be adopted again) (High Level Panel Citation2013) ().

How to operationalize this could be a subject of further research. Ubuntu above all can underpin the cluster on global partnership (MDG8) that was inserted in the framework by developing countries. Ubuntu ties in with social clusters on health (MDG4, 5, 6) and education (MDG2) by seeming to support the notions of the global social floor. Literature on the African philosophy of education (Nafukho Citation2006; Le Roux Citation2000; Waghid Citation2004) as well as moral education of personhood (Horsthemke Citation2009) can inform a new MDG2. Though contentious in some feminist circles (Roberts Citation2010), gender specialists may find inspiration as well.Footnote16 Ubuntu has a distinctive view of environmental protection (MDG7) by considering nature and man as a whole. Ubuntu can inspire a future cluster on peace and security with its emphasis on restorative justice. It can inspire a future cluster on institution building and rule of law by its jurisprudence on public law.

To reduce a philosophy as expansive as Ubuntu to targets and indicators is, however, somewhat contrary to what it tries to achieve: namely to infuse humans with a consciousness of wholeness and interdependence, on each other and their natural surroundings, including a spiritual level of being. This may offend the secular Western science, but does justice to the people, ‘the professional experts’ are trying to develop (on processes see e.g. Armstrong Citation2013; Boyte Citation2013). If they are to be the agents of change, the question once more is ‘whose development?’ and ‘aiming at what?’ Does the West have something to gain too by incorporating indigenous views into the development narrative? Post 2015 should first and foremost be a platform for debate on how to solve the world's most pressing problems. And ‘how’ starts at the conceptual level.

9. Conclusion

Having concluded that Ubuntu is an African concept of well-being that has thus far not been sufficiently taken into account by dominant well-being theories, it seems worthwhile to do so and link it to the post 2015 debate. Ubuntu aligns with theories on social personhood, which stretch beyond the capability theory with its focus on individual objective well-being that influenced the MDGs. It has political and legal relevance. It ties up with the notion of South–South solidarity. It is closely related to human rights theory, adding a relational dimension and emphasizing the role of duties in relation to rights.

A relationship between Ubuntu and GPGs theory has been established. The normative as opposed to the strict economic GPG theory should inform the post 2015 agenda, which in turn needs to be multicultural in order to have significance for the people it concerns. Besides contributions from Latin America (Buen Vivir) and Asia (Happiness), Africa and its Ubuntu can inform the development debate in terms of what measures are important and above all what processes are required. Moreover, it can emphasize the interrelationship of the current goals.

This is not merely window-dressing, but a fundamental reshaping of our thinking, where market competition is complemented by cooperation; and where acting out of ‘self-interest’ is balanced by the notion of ‘not existing without the other’. Or as Behrens (Citation2014, 18) puts it ‘So many African voices claim that the fact that we are interconnected entails that we are morally responsible for one another.’

Ubuntu thereby is not an ideal model of life – which for some is a reason to relegate it to the land of fairytales – it rather encourages us toward better self-realization as a community, to come closer to the ideal, and to reach our full human potential as society and as individuals.

Acknowledgements

This article is written as part of a PhD thesis supervised by Prof Dr. W.J.M. van Genugten, Law Faculty, University of Tilburg, and Prof. Dr. J. Gupta, Governance and Inclusive Development (GID), Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research, University of Amsterdam.

Notes

1. UN General Assembly, 65th session, Happiness, towards a holistic approach of development, Resolution A/65/L.86, New York, (July 13, 2011), www.2apr.gov.bt/images/stories/pdf/unresolutiononhappiness.pdf

2. Also in Ndebele and Swati (Nguni language family), (van Binsbergen Citation2001, 1).

3. According to Gade, the connection between Ubuntu and the proverb only emerged in the period 1993–1995 (Gade Citation2011).

4. Some stated it is a quality blacks possess and whites lack, Gade refers to Jabavu in 1960 and Thompson & Butler in 1975 (Gade Citation2011, 308); others use it to overcome the black–white divide (Teffo Citation1996, 101–108).

5. I take support in Metz and Gaie's statement that

… this sketch of an Afro-communitarian moral perspective should not be taken to represent anthropologically the beliefs of Africans about the right way to live. It is, rather a theoretical reconstruction of themes that are recurrent among many peoples below the Sahara desert ( … ) (Metz and Gaie Citation2010, 277)

6. The Post-2015 Development Agenda: The Millennium Development Goals in Perspective, No. 74, April 2011, www.aiv-advice.nl

7. Derived from discussions with I. Van Kessel.

8. The concluding provision on National Unity and Reconciliation contains the following commitment:

The adoption of this Constitution lays the secure foundation for the people of South Africa to transcend the divisions and strife of the past, which generated gross violations of human rights, the transgression of humanitarian principles in violent conflicts and a legacy of hatred, fear, guilt and revenge. These can now be addressed on the basis that there is a need for understanding but not for vengeance, a need for reparation but not for retaliation, a need for ubuntu, but not for victimisation. (Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act 200 of 1993: Epilogue after Section 251)

It was done to justify the necessity of a National Truth and Reconciliation Commission (see Ramose Citation2001).

9. Eze (Citation2010, 103) dismisses speculations that the omission was an attempt by ANC to distance itself from Inkatha, as Ubuntu appears in the 1975 Inkatha Constitution.

10. ‘..constitution based on the spirit of Ubuntu, compromise, consensus, reconciliation and nation building.’

14. The EU chooses as priorities: trade and investment, climate change, food security, migration, and peace and security, in her Policy Coherence for Development (European Union Citation2009).

15. Northern Sotho –English dictionary, http://africanlanguages.com/sdp/

16. Indeed Ramose remarks ‘the ineffable [greatest of the great or world of metaphysics] is neither male nor female. But if it must be genderized at all it is female-male (hermaphroditic)(..)’ (Ramose Citation1999, 46).

References

- Armstrong, J. 2013. Improving International Capacity Development: Bright Spots. Hampshire: Palgrave McMillan.

- Azenabor, G. 2008. “African Golden Rule Principle and Kant's Categorical Imperative.” Quest: An African Journal of Philosophy XXI: 229–240.

- Behrens, K. 2014. “An African Relational Environmentalism and Moral Considerability.” Environmental Ethics (Special Issue on African Environmental Ethics) 36 (1): 63–82. https://www.academia.edu/1188836/An_African_Relational_Environmentalism_and_Moral_Considerability

- Bennett, T. W. 2011. “Ubuntu: An African Equity.” Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal PER/PELJ 14 (4): 30–61.

- Bewaji, J. A. I., and M. B. Ramose. 2003. “The Bewaji, van Binsbergen en Ramose Debate on Ubuntu.” South African Journal of Philosophy 22 (4): 378–414.

- van Binsbergen, W. 2001. “Ubuntu and the Globalization of Southern African Thought and Society.” Quest: An African Journal of Philosophy XV (1–2): 53–89.

- van Binsbergen, W. 2008a. “Traditional Wisdom, its Expressions and Representations in Africa and Beyond, Exploring Intercultural Epistemology.” Quest: An African Journal of Philosophy XXII: 49–120.

- van Binsbergen, W. 2008b. “Lines and Rhizomes: The Transcontinental Element in African Philosophies.” Quest: An African Journal of Philosophy XXI: 7–22.

- Boyte, H. 2013. Reinventing Citizenship as Public Work: Citizen-Centered Democracy and the Empowerment Gap. Dayton, OH: Kettering Foundation Press.

- Broodryk, J. 2002. Ubuntu Life Lessons from Africa. Pretoria: School of Philosophy.

- Coetzee, P. H., and A. P. J. Roux. 2002. Philosophy from Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cornell, D. 2005. “Exploring Ubuntu; Tentative Reflections.” African Human Rights Journal 5 (2): 195–220.

- Cornell, D. 2008. “Ubuntu, Pluralism and the Responsibility of Legal Academics to the New South Africa.” Inaugural Lecture, Department of Private Law, University of Capetown (UCT). http://www.uct.ac.za/usr/lectures/Drucilla_Cornell.pdf

- Cornell, D. 2012. “A Call for a Nuanced Constitutional Jurisprudence: South Africa Ubuntu, Dignity and Reconciliation.” In Ubuntu and the Law: African Ideals and Post-Apartheid Jurisprudence, edited by N. Muvangua and D. Cornell, 323–333. New York: Fordham University Press. http://www.newschool.edu/uploadedFiles/TCDS/Democracy_and_Diversity_Institutes/Cornell_Ubuntu,Dignity,Reconciliation.pdf

- Cornell, D., and N. Muvangua. 2012. Ubuntu and the Law: African Ideals and Post-Apartheid Jurisprudence. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Deneulin, S., and J. A. McGregor. 2010. “The Capability Approach and the Politics of a Social Conception of Wellbeing.” European Journal of Social Theory 13 (4): 501–519. doi: 10.1177/1368431010382762

- Diagne, S. B. 2009. “Individual, Community and Human Rights, a Lesson from Kwasi Wiredu's Philosophy of Personhood.” Transition 101: 8–15.

- Douglas, M., and S. Ney. 1998. Missing Persons: A Critique of the Social Sciences. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Ebrahim, E. 2013. “Human Rights: Central to South Africa's Foreign Policy.” UBUNTU Diplomacy in Action 3: 36–38.

- European Union. 2009. Policy Coherence for Development. Council Conclusions 16079/09, 17/11/2009.

- Eze, M. O. 2008. “What is African Communitarianism? Against Consensus as a Regulative Ideal.” South African Journal of Philosophy 27 (4): 386–399.

- Eze, M. O. 2010. Intellectual History of Contemporary South Africa, chapters 6–9. New York: Palgrave McMillan, St Martin's Press.

- Fitoussi, J. P., A. Sen, and J. E. Stiglitz. 2009. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. http://www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr/en/index.htm

- Fransman, M. 2013. “Securing Democracy, Securing Business – Building a Prosperous South Africa for All.” UBUNTU Diplomacy in Action 3: 46–48 (Deputy Minister of International Relations and Cooperation).

- Gade, C. B. N. 2011. “The Historical Development of the Written Discourses on Ubuntu.” South African Journal of Philosophy 30 (3): 303–329. doi: 10.4314/sajpem.v30i3.69578

- Gade, C. B. N. 2012. “What is Ubuntu? Different Interpretations among South Africans of African Descent.” South African Journal of Philosophy 31 (3): 484–503.

- Gudynas, E. 2011. “Buen Vivir, Todays Tomorrow.” Development 54 (4): 441–447. doi: 10.1057/dev.2011.86

- Gyekye, K. 2004. Beyond Cultures, Perceiving a Common Humanity: Ghanaian Philosophical Studies III, Washington, DC: Council for Research in Values and Philosophy.

- High Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post 2015 Development Agenda. 2013. A New Global Partnership: Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economies through Sustainable Development. http://www.post2015hlp.org/

- Horsthemke, K. 2009. “Rethinking Humane Education.” Ethics and Education 4 (2): 201–214. doi: 10.1080/17449640903326813

- Jiyane, F. 2014. “Ubuntu Walk in Honour of Madiba.” UBUNTU Diplomacy in Action 5: 86.

- Kaul, I., and R. U. Mendoza. 2003. “Advancing the Concept of Public goods.” In Providing Global Public Goods: Managing Globalization, edited by I. Kaul, P. Conceição, K. Le Goulven, and R. U. Mendoza, 78–112. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://web.undp.org/globalpublicgoods/globalization/pdfs/kaulmendoza.pdf

- Krog, A. 2008. “This Thing Called Reconciliation … ’ Forgiveness as Part of an Interconnectedness-Towards-Wholeness.” South African Journal of Philosophy (SAJP) 27 (4): 353–366.

- Le Roux, J. 2000. “The Concept of ‘Ubuntu’: Africa's Most Important Contribution to Multicultural Education?” Multicultural Teaching 18 (2): 43–46.

- Louw, D. J. 1998. “Ubuntu: An African Assessment of the Religious Other.” 20th World Congress of Philosophy, Boston, http://www.bu.edu/wcp/Papers/Afri/AfriLouw.htm

- Martins, V. 2011. “South Africa Goes BRICS: the Importance of Ubuntu in Foreign Policy.” IPRIS Viewpoints 52, Portuguese Institute for International Relations and Security (IPRIS).

- Masolo, D. A. 2001. “Communitarianism, An African Perspective” In The Proceedings of the Twentieth World Congress of Philosophy, Vol 12, Intercultural Philosophy, edited by S. Dawson and T. Iwasawa, 209–228. https://www.pdcnet.org/pdc/bvdb.nsf/purchase?openform&fp=wcp20&id=wcp20_2001_0012_0209_0228.

- Mbiti, J. S. 1990. African Religions and Philosophy. 2nd ed. Oxford: Heinemann Educational Publishers (first published 1969).

- McDonald, D. A. 2010. “Ubuntu Bashing: The Marketization of ‘African Values’ in South Africa.” Review of African Political Economy 37 (124): 139–152. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2010.483902

- Metz, T. 2007. “Ubuntu as a Moral Theory: Reply to Four Critics.” South African Journal of Philosophy 26 (4): 369–387.

- Metz, T., and J. B. R. Gaie. 2010. “The African Ethic of Ubuntu/Botho: Implications for Research on Morality.” Journal of Moral Education 39 (3): 273–290. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2010.497609

- Mofuoa, K. V. 2010. “Refections on Botho as a Resource for a Just and Sustainable Economy towards Africa's Development Path in Modern History.” World Journal of Enterpreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 6 (4): 273–291.

- Mokgoro, Y. 1997. “Ubuntu and the Law in South Africa.” In Seminar Report Constitution and the Law, organized by Faculty of Law, Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education, Johannesburg: Conrad Adenauer Stiftung Edited Version in 1998, Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal PELJ/PER 1 (1): 15–26, www.ajol.info/index.php/pelj/article/.../27090

- Nafukho, F. M. 2006. “Ubuntu Worldview: A Traditional African View of Adult Learning in the Workplace.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 8 (3): 408–415. doi: 10.1177/1523422306288434

- Naicker, I. 2011. “The Search for Universal Responsibility: The Cosmovision of Ubuntu and the Humanism of Fanon.” Development 54 (4): 455–460. doi: 10.1057/dev.2011.84

- Northern Sotho – English dictionary, online since April 2003, http://africanlanguages.com/sdp/

- OECD-DAC (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development – Development Assistance Committee). 1996. Shaping the 21st Century: The Contribution of Development Cooperation. http://www.oecd.org/dac/2508761.pdf

- Outlaw, J. R., and T. Lucius. 2010. “Africana Philosophy.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2010 Edition), edited by E. N. Zalta. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2010/entries/africana/

- Pieterse, A. M. 2014. “Ubuntu: The Original Vision for South Africa, Our Continent and the Whole World.” UBUNTU Diplomacy in Action 5: 85 (National Coordinator Humanity's Team).

- Ramose, M. B. 1999, 2005 revision. African Philosophy through Ubuntu. Harare: Mond Books.

- Ramose, M. B. 2001. Polylog. http://them.polylog.org/3/frm-en.htm#f27

- Ramose, M. B. 2007. “But Hans Kelsen Was Not Born in Africa: A Reply to Thaddeus Metz.” South African Journal of Philosophy 26 (4): 347–355.

- Rights and Humanity Global Leaders Congress. 2009. Ubuntu Declaration for a Just and Sustainable World Economy. London. http://www.rightsandhumanityglc.org/UserFiles/file/Ubuntu_Declaration_for_a_Just_and_Sustainable_World_Economy_F7.pdf

- Roberts, A. 2010. “South Africa: A Patchwork Quilt of Patriarchy.” Skills at Work: Theory and Practice Journal 3: 59–69.

- Setiloane, G. 1976. The Image of God among the Sotho-Tswana. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema.

- Sooklal, A. 2012. “South Africa, BRICS and Global Governance.” UBUNTU Diplomacy in Action 2: 35–38 (Ambassador Asia and Middle East Department).

- South African Embassy in The Hague. 2011. Presentation available to author. See also speech Minister of international relations and cooperation Ms Maite Nkoana-Mashabane in Sofia, Bulgaria, September 3.

- South African Government. 2011. “Building a Better World: the Diplomacy of Ubuntu.” www.gov.za/documents/download.php?f=149749

- Teffo, L. J. 1996. “The Other in African Experience.” South African Journal of Philosophy 15 (3): 101–108.

- UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). 2010. “Follow up to the Millennium Summit and Preparations for the High-Level Plenary Meeting of the General Assembly on the Millennium Development Goals: New Development Paths.” Forty-ninth Executive Session, Geneva, 8–9, June 2010. http://unctad.org/en/Docs/tdbex49summary-MDGs_en.pdf

- Van Niekerk, J. 2007. “In Defense of an Autocentric Account of Ubuntu.” South African Journal of Philosophy 26 (4): 364–368.

- Van Norren, D. E. 2012. “The Wheel of Development: The Millennium Development Goals as a Development and Communication Tool.” The Third World Quarterly 33 (5): 825–836. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2012.684499

- Waghid, Y. 2004. “African Philosophy of Education: Implications for Teaching and Learning: Perspectives on Higher Education.” South African Journal of Higher Education 18 (3): 56–64.

- Wewerinke, M. 2007. “Human through Others, Towards a Critical Participatory Debate.” Masterthesis, Radboud University Nijmegen. http://www.socsci.ru.nl/maw/cidin/bamaci/scriptiebestanden/641.pdf

- Wingo, A. 2008. “Akan Philosophy of the Person.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2008 Edition), edited by E. N. Zalta, http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/akan-person

- Wiredu, K. [1998] 2003. “The Moral Foundations of an African Culture.” In The African Philosophy Reader. Updated ed., edited by P. H. Coetzee and A. P. J. Roux, 337–348. London: Routledge.

- Wood, A. 2007. “Crosscultural Moral Philosophy: Reflections on Thaddeus Metz: ‘Toward an African Moral Theory’.” South African Journal of Philosophy 26 (4): 336–346.

- Zondi, S. 2014. “Principles of South Africa's Development Diplomacy. The Case of its Post 2015 Agenda.” UBUNTU Diplomacy in Action 5: 24–25 (Director Institute for Global Dialogue).