ABSTRACT

One of the distinctive features of environmental justice theory in Latin America is its influence by decolonial thought, which explains social and environmental injustices as arising from the project of modernity and the ongoing expansion of a European cultural imaginary. The decolonization of knowledge and social relations is highlighted as one of the key challenges for overcoming the history of violent oppression and marginalization in development and conservation practice in the region. In this paper we discuss how conflict transformation theory and practice has a role to play in this process. In doing so, we draw on the Socio-environmental Conflict Transformation (SCT) framework elaborated by Grupo Confluencias, which puts a focus on building community capacity to impact different spheres of power: people and networks, structures and cultural power. We discuss this framework and its practical use in the light of ongoing experiences with indigenous peoples in Latin America. We propose that by strengthening the power of agency of indigenous peoples to impact each of these spheres it is possible to build constructive intra and intercultural relations that can help increase social and environmental justice in their territories and thus contribute to decolonizing structures, relations and ways of being.

Introduction

Over the last three decades, indigenous peoples have become central players in environmental justice struggles in Latin America. This is not fortuitous. On the one hand, it is the result of the increasing pressure being exerted by a wide variety of development, extractive and conservation initiatives over their territories. On the other hand, it is the result of the consolidation of their political agency in the region. Since the 1980s indigenous peoples have been consistent in their demands for autonomy and self-determination, and have been increasingly successful in paving their own pathway to sustainability through the construction of new environmental, cultural and collective rights in the region (Leff Citation2001).

This is reflected in the progress made over past decades in Latin America in terms of the protection of indigenous peoples’ rights, in comparison to other parts of the world: of the 22 countries that by 2011 had ratified Convention 160 of the ILO on indigenous peoples’ rights, 14 are Latin American.Footnote1 In 2007, all Latin American countries except Colombia, voted in favor of the UN Declaration of the rights of indigenous peoples. This tendency is also reflected in recent reconfigurations in the models of the Nation-State through new pluricultural and plurinational national constitutions, e.g.: Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela, which amongst other rights, acknowledge those of indigenous peoples to their territorial autonomy. And lastly, it is reflected in the expansion of indigenous peoples’ alternative development discourses and proposals, some of which have started to be incorporated into national development discourses and strategies, such as the philosophy of ‘Buen Vivir’Footnote2 (Huanacuni Mamani Citation2010).

Indigenous peoples’ movements and their struggles have also been an inspiration to the emergence of new Latin American critical thinking, such as decolonial theory, known in the region as the Decolonial Project (Lander Citation2000; Quijano Citation2000; Escobar Citation2003; Walsh Citation2007; Mignolo Citation2008). This theory identifies social and environmental injustices as arising from the project of modernity and the continual reproduction of European cultural values.

To a large extent in Latin America, in contrast to other parts of the world, environmental justice thinking has developed alongside decolonial thought, through the work, for instance, of Escobar (Citation1998, Citation2010a, Citation2010b, Citation2010c) and Leff (Citation2001, Citation2003, Citation2004). Both authors were pioneers in describing the anti-modernity and decolonial agenda of indigenous peoples’ struggle for environmental justice and positioning an environmental justice theory in the region with a ‘decolonial turn’ (Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel Citation2007). Some more recent addition to this body of knowledge from an environmental justice perspective, include Acosta et al. (Citation2011), Acosta (Citation2013, Citation2015), Gudynas (Citation2010a, Citation2010b, Citation2011, Citation2012) and also Santos (Citation2008), who although not strictly Latin American, works in close collaboration with Latin American decolonial scholars.

This strong focus on decolonization marks a difference from environmental justice thinking in the Global North, which in comparison has tended not to emphasize so much the colonial and epistemic roots of injustices in the Global South. This is partly due to the fact that in its early years environmental justice theory from the Global North had a strong focus on injustices arising from the unequal distribution of natural resource hazards in advanced capitalist political-economy. The work of Bullard (Citation1983) in particular, examining the relationship between racial discrimination and industrial and waste dumping activities in the USA, marked the start of environmental justice research in the Global North with a strong distributive focus. Thanks to the work of Pellow (Citation2007) and Schlosberg (Citation2007, Citation2013), among others, over the years environmental justice research from the Global North has been moving away from its initial focus on distributive justice. Schlosberg in particular, drawing upon detailed studies of environmental justice movements across different classes, races, ethnicities and gender, as well as on Fraser’s (Citation1998) three-dimensional definition of justice, has made a tremendous contribution to a more pluralist understanding of the meaning of environmental justice. He has consistently debated that justice is not just about equity (distributive justice), but also includes recognition and participation (procedural justice). More recently, drawing upon the work of Nussbaum (Citation2011), he added a fourth dimension to this discussion arguing that justice is also about fulfilling community capabilities, particularly in the context of indigenous peoples’ struggles (Schlosberg and Carruthers Citation2010). Another important development in environmental justice thinking from the Global North is the increasing attention paid to the regional specificities of the histories of environmental justice movements and its scholarship across the world (Lawhon Citation2013). Carruthers (Citation2008a) edited volume Environmental Justice in Latin America is a case in point, where the contributors pay attention to analyzing precisely what makes Latin American environmental justice frameworks distinct from those present in others parts of the world. The authors highlight the long tradition for social justice demands and movements in different fields (political participation, land distribution, human rights and community health) as a salient feature, as well as the central importance that cultural identity (linked to campesino, indigenous and women’s demands for justice) has historically played in environmental justice struggles in the region.

Although environmental justice literature from the Global North increasingly acknowledges the historical legacy of colonialism in environmental justice struggles in Latin America, particularly in reference to land use and distribution patterns (Carruthers Citation2008b), it rarely mentions the persistence of colonial values (coloniality) as a cause of current injustices and violence, and the need to confront it. This is precisely what South American environmental justice thinking offers through its focus on decoloniality.

Additionally, a cross-fertilization between academic fields has started to take place in the region, with decolonial theory merging with different traditions of environmental justice action-research. Such is the case of Grupo Confluencias, a group of Latin American conflict transformation practitioners and researchers who have been working since 2005 on a regionally specific approach for environmental conflict-transformation, through the development of new conceptual and methodological frameworks. Grupo Confluencias has merged Conflict Transformation theory (which originated in Peace Studies) with decolonial thought, power theory and political ecology, and developed a Socio-environmental Conflict Transformation (SCT) Framework that seeks to guide conflict transformation work for greater environmental justice in the region.

In this paper we present the SCT framework in order to show what conflict transformation practice can offer for decolonizing environmental injustices in the region. We argue that conflict transformation scholars and practitioners can and must play a role in decolonizing environmental injustices through a commitment to engage with the structural and historical forces that create marginalization and exclusion in the use of natural resources and territories. We also propose that conflict transformation can help move forward the decolonizing praxis, by engaging with a level of injustices rarely addressed in decolonial theory: the intra-community level. Despite indigenous peoples’ discourses of ‘Buen Vivir’ and their claims in environmental struggles for alternative development pathways, the intense processes of cultural change that they have been subject to from colonial to modern times, often puts them in very weak positions to successfully pursue a decolonial agenda at the community level. In conflict situations, this internal fragility often makes indigenous peoples prone to division and fragmentation, reducing the chance of successfully confronting the hegemonic powers that create injustice.

The SCT Framework is particularly aimed at strengthening the capacity of vulnerable actors to transform environmental conflicts through impacting three different types of hegemonic power: structural, cultural and actor-networks. In doing so, it can help develop differentiated strategies to challenge dominant discourses, economic, legal and political structures and practices and the relationships that give rise to environmental justice struggles. The premise is that a focus on building community capacity to transform conflicts at the intra-cultural level helps to create the conditions for more symmetrical and horizontal intercultural dialogues, which are key for decolonizing environmental injustices. To our knowledge, such an approach for engaging with environmental justice struggles is new to environmental justice work. Thus, beyond contributing to decolonizing environmental injustices, it also has something new to offer to environmental justice thinking more broadly.

In order to illustrate our framework, we draw on work carried out with indigenous peoples from different parts of Latin America (Argentina, Bolivia, Guatemala and Venezuela) to transform socio-environmental conflicts.

The text is divided into five parts. In the first section we explore the overlap and complementarity between decolonial and conflict transformation thought in terms of understanding and addressing environmental injustice in the region. This is followed by a discussion of power, paying attention first to describing how hegemonic power is exercised in environmental conflicts and later to how such power can be challenged in order to increase environmental justice. In order to illustrate the latter point, in the fourth section, we discuss different strategies that can help indigenous peoples impact on the different spheres of power and thus contribute to conflict transformation processes in the region. We close in the fifth section with a short synthesis of the main points highlighted in the paper and some ideas for further research.

Decolonial and conflict transformation theory: exploring the overlap and complementarity

Main propositions of decolonial theory:

Decolonial thought is distinct from other post-colonial critical theory through its focus on the Global South and for identifying mechanisms of subordination and marginalization in Eurocentric scientific and political worldviews. Proponents of this school of thought are largely from Latin America (Quijano Citation2000; Lander Citation2000; Leff Citation2001; Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel Citation2007; Escobar Citation2003; Walsh Citation2007; Mignolo Citation2008), but important contributions have also come from India (Visvanathan Citation1997), Portugal (Santos, Arriscado, and Meneses Citation2008; Santos Citation2010) and New Zealand (Smith Citation1999) among others.

According to decolonial theory ‘colonialism’ ended with political independence in the Global South, but ‘coloniality’ persists through dominant colonial/modern values and world views that are institutionalized and disseminated through education, the media, state-sanctioned languages and behavioral norms. Thus, ‘coloniality’ is a form of power that creates structural oppression over marginalized sectors of society, such as indigenous peoples, whose alternative worldviews become devalued, marginalized and stigmatized in development and conservation practice. From this perspective, coloniality is a particular mechanism and form of mis-recognition that must be confronted in order to achieve emancipation and social/environmental justice.

Decolonial scholars argue that modernity leads to profound psychological harm for indigenous peoples as it erodes vital conditions for their wellbeing, including cultural identity, freedom of choice and self-respect. It also has tangible impacts on the status and participation of indigenous peoples in development and conservation practice by disregarding local notions of authority and territory, frequently resulting in displacement or enforced change to livelihoods. Furthermore, they argue that psychological and physical harm is perpetuated through a matrix operating at three levels: a) power (political and economic), b) knowledge (epistemic, philosophical and scientific) and c) the self or ways of being (subjective, individual and collective identities). Thus, responses to coloniality necessarily involve decolonizing power, knowledge and the being.Footnote3 This involves moving away from a unitary model of citizenship and civilization to one that respects different local economies, politics, cultures, epistemologies and forms of knowledge.

This focus of decolonial theory on the epistemological dimension of oppression and domination adds an important new critical lens to environmental justice work. It highlights the need to engage with one of the most invisible and subtle ways in which violence is exercised in environmental justice struggles: through the imposition of particular ways of knowing the world at the expense of oppressing others, in other words, through epistemic violence. Thus, as suggested by Walsh (Citation2005b) and Santos (Citation2008), the greatest challenge for emancipation from a decolonial perspective is to move towards a situation of greater cognitive justice in the world, learning from, and making visible, alternatives forms of knowledge. Thus, the ecology of knowledge (Santos Citation2008), also termed by other decolonial theorists as dialogues of knowledge/wisdoms (Leff Citation2004) or the construction of interculturality (Walsh Citation2005a), is viewed as the core of a decolonial praxis.

But interculturality here is radically different from other more widely used functional definitions. Decolonial thinkers such as Tubino (Citation2005), Walsh (Citation2005a, Citation2005b, Citation2007) and Santos (Citation2010), approach interculturality from a critical perspective. The term ‘intercultural’ is not understood as a simple contact, but as an exchange that takes place in conditions of equality, mutual legitimacy, equity and symmetry. This encounter of cultures is a permanent and dynamic vehicle for communication and mutual learning. It is not just an exchange between individuals but also between knowledge, wisdoms and practices that develop a new sense of co-existence in their difference.

Therefore:

More than the idea of simple interrelation (or communication, as it is often understood in Canada, Europe or the United States), interculturality refers to, and means, an “other” process of knowledge construction, an “other” political practice, and “other” social (and State) power and an “other” society; an “other” way to think and act in relation to, and against, modernity and colonialism. An “other” paradigm that is thought and acted upon, through political praxis. (Walsh Citation2007, 47)

Thus, the ‘inter’ space, becomes an arena of negotiation where social, economic and political inequalities are not kept hidden, but are made visible and confronted. In this sense, the dialogue among cultures and knowledge plays an important part in a wider process of social transformation.

Intra-cultural dialogues: a missing link

One issue that has received little attention in decolonial literature is the question of cultural difference at the intra-cultural level. Environmental justice literature also has a blind spot on this issue. Despite its sensitivity to social meaning, inter-subjectivity and long-term historical contexts, decolonial literature pays little attention to the fact that culture itself is often contested at the local level. There has been a paucity of discussion about the conditions necessary for dialogue about the use of nature among different actors within communities, especially in the context of shifting local identities and rapid cultural change among indigenous peoples.

In most of the developing world indigenous peoples are undergoing rapid processes of cultural change, which may seriously constrain local reflexivity over environmental and development issues. In Latin America in particular, modern nation state building has been premised on narratives of national identity and modernity that have contributed significantly to undermining ‘traditional’ views and the values placed upon nature by indigenous people. This trend has continued even within emerging pluricultural nation-state models, such as those currently favored in Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador, where at least nominally, and with different degrees, indigenous peoples’ rights are acknowledged and recognized in foundational legal frameworks, such as national constitutions (Méndez Citation2008). In addition, this loss of traditional knowledge is uneven and varies between and within indigenous groups and communities, thus giving rise to contested and shifting views of development and knowledge of the environment at the community level. These local conflicts, in turn, may act as a strong barrier for discussing and defining sustainability pathways at the community level.

In order for intercultural dialogues to take place, it is necessary to first acknowledge the ongoing and often conflicting processes of cultural change and identity formation that are shaping, and will continue to shape, development pathways of environmental management strategies at the local level. These processes of cultural change, in turn, inform complex relations of power that tend to hinder reflexivity and dialogue at the intra-cultural level. Ultimately, a critical understanding of changing identity and local views of nature is crucial for developing more just and productive forms of deliberation, where the diverse forms of knowledge of marginalized groups are brought to the foreground in discussions about present and future development and environmental management.

Building community capacity to overcome these internal differences, through differentiated strategies that can help clarify local perspectives, knowledge as well as strengthening local organization, is essential for intercultural dialogue to take place. This is where conflict transformation practice can support a decolonial agenda in Latin America.

Conflict transformation and local capacity building

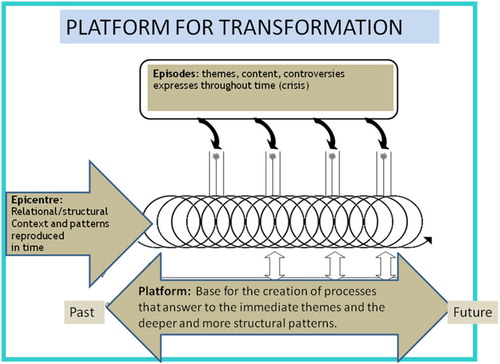

Conflict transformation theory is rooted in peace studies, specifically in post-war conflicts, with the works of authors such as Lederach (Citation1995, Citation2003, Citation2008) and Galtung (Citation1969, Citation1990, Citation2004). Unlike other approaches which see conflict as something negative that must be overcome or reduced, the transformative approach rather sees conflict as a catalyst for social change through its double dimension: conflict creates stress in social relations, but it also offers the potential to help overcome, change and transform conflicting relationships towards more harmonious, constructive and balanced ones (see ). This is because it allows unearthing injustices and making them visible, thus signaling necessary changes in society.

Table 1. Basic differences between conflict resolution and conflict transformation.

Conflict transformation involves moving away from the logic of resolving to understanding conflicts. From this perspective, the role of external actors changes from fire-fighters to architects of change who must help build transformative platforms for new social relations.

As an analytical approach, it provides tools to understand conflict dynamics and the multiple levels in which it is expressed: in people, in relationships, leadership forms, organizations, political systems, the construction of narratives, and in cultural frameworks. This means that from a descriptive perspective, conflicts are in constant change due to various reasons (contextual, structural, strategies of the actors, etc.) and we can / must engage with them in order to transcend the immediate expression of the conflict.

Similarly to decolonial theory, this approach postulates that behind a conflict episode lie relational and structural factors that determine its current expression, and which must be addressed if we are to increase justice in relationships and social structures, and avoid recurrence. In socio-environmental conflicts we can easily differentiate between a conflict episode (claims to environmental liabilities, opposition to a particular policy, mobilization against the installation of an extractive activity or the construction of infrastructure, violation of indigenous territories, etc.) and underlying causes, which are commonly found far from these events, both physically and historically. This is what Lederach calls the epicenter of a conflict (see below).

Figure 1. The transformative platform. Source: Lederach (Citation2003).

From a prescriptive perspective, conflict transformation is also a process of commitment to the transformation of relationships, patterns, discourses and, if necessary, the very shape of society that creates conflict. This requires transcending the ‘episodic’ expression of conflict, instead focusing on the relational and historical patterns in which the conflict is rooted and in those areas that generate or make inequities invisible, driving an approach that can reflect the desired changes and that also generates operational solutions to immediate problems.

Thus, the conflict transformation approach seeks to develop strategies at multiple levels and scales. It advocates the idea of platforms for transformation (Lederach Citation1995) with a view to promoting processes of constructive change at the personal, inter-group and structural levels that can generate greater justice and reduce violence in relationships and society.

Conflict transformation is therefore a long-term process of socio-political, psycho-social and cultural transformation in which key aspects of the reality are addressed in the short-term, in conjunction with structural issues that can be resolved in the medium, and long-term. Thus, the key is to have a strategic vision of transformation that articulates the needs and actions that must be taken in the short-term (addressing the specific episode) with a long-term pathway for change (addressing the epicenter).

There are two complementary components of this strategic vision. First, similar to decolonial theory, conflict transformation postulates the need to engage with power in order to overcome the structural causes of injustice. Second, and linked to the above, is the attention paid to strengthening the capacity of vulnerable actors to transform conflicts, through a variety of training and capacity building processes, as a necessary starting point in the long-term vision of transformation (Lederach Citation1995; Botes Citation2003). These processes of local capacity building are aimed precisely at promoting intra-cultural dialogues about complex issues related to the cause of conflicts in order to create the conditions for more symmetrical inter-cultural dialogues.

Yet, as conflict transformation theory was originally created to deal with conflicts in post-war scenarios, the understanding of power is not sufficiently adapted to the context of environmental conflicts. A more nuanced approach to power that can guide socio-environmental conflict transformation practice in the region is necessary. As we will see, this approach to power shares important points in common with decolonial theory.

Understanding hegemonic power

In order to understand how power is expressed in socio-environmental conflicts and to address existing asymmetries, it is useful to distinguish between two kinds of power: hegemonic power and transformative power. While the first refers to power in its coercive form (what some theorists call ‘power on’ or power as domination), the second refers to forms of power that seek to impact power of domination and bring about social change.

The notion of power as domination is the most commonly known. It implies the idea of imposing a mandate or an idea. However, power of domination is not always exercised coercively, but through subtle mechanisms. In this sense, it is important to distinguish between the visible and less visible face of domination (for the latter see Foucault Citation1971) (see ).

Table 2. Ways in domination is manifested.

In society, the visible face of power is manifested through decision-making bodies (institutions) where issues of public interest, such as legal and economic frameworks, regulations and public policies, are decided. This includes the formal political decision-making bodies, such as congresses, legislative assemblies and advisory bodies, and decision-making mechanisms used by civil society and social movements. This is the public space where different actors display their strategies in order to assert their rights and interests. This type of power is also known as institutional or structural power.

Yet most of the time, power is exercised in a hidden way, by some sectors attempting to maintain their privileged position in society, creating barriers to participation, excluding issues from the public agenda or controlling political decisions ‘behind the scene’. In other words, the power of domination is exercised also by people and power networks (Long and Van Der Ploeg Citation1989) that are organized to ensure that their interests and world-views prevail over others.

The power of domination also works in an invisible way through discursive practices, narratives, worldviews, knowledge, behaviors and thoughts that are assimilated by society as true without public questioning (Foucault Citation1971). This invisible, subtle form of power often takes the shape in practice (following Galtung Citation1990) of cultural violence, through the imposition of value and beliefs systems that exclude or violate the physical, moral or cultural integrity of certain social groups by devaluing their own value and belief systems.

These structural forms of power are materialized in state institutions, the market and civil society, giving rise to a structural bias in relationships and consequent asymmetrical power relations. Therefore, this form of invisible power is also known as cultural power. Here, people can remain ignorant of their rights or ability to enforce them, and may see certain forms of domination over them as natural or immutable, and therefore unquestionable. In this way, invisible power and hidden power often act together, one controlling the world of ideas and the other controlling the world of decisions.

This distinction between power concentrated in institutions, people and culture is very important for understanding power relationships and domination in socio-environmental conflicts and in the perpetuation of environmental injustices.

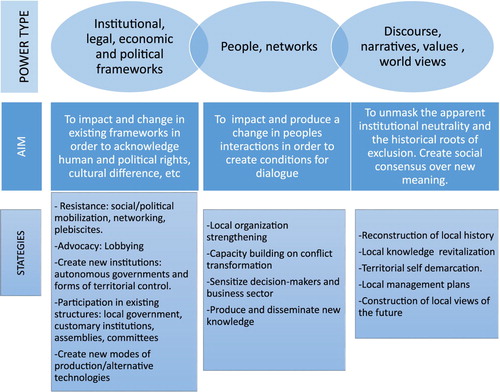

The challenge for overcoming violence, injustice (Young Citation1990) and thereby for achieving conflict transformation is to generate strategies that impact on these three areas in which power is concentrated in environmental management and territorial control: a) institutions and economic and legal frameworks, b) people and their networks, and c) discourses, narratives and wold views. This takes us to a discussion of the concept of power of agency, which will show how we can put power at the service of conflict transformation.

Impacting hegemonic power

Although there is a tendency to think of power as something negative due its coercive and hegemonic manifestations, power has also been widely described positively as a ‘force in the service of an idea’ (Burdeau Citation1985), or the ‘ability to do things and change your circumstances’ (Giddens Citation1984). This positive notion of power is commonly known as the ‘power of agency’, which is defined as ‘the ability of social partners to define social problems and political issues and mobilize resources to formulate and carry out a desired solution’ (Arts and Van Tatenhove Citation2004). Unlike power of domination, which is known as ‘power over’, power of agency is commonly known as the ‘power to’ change. The power of agency is complemented and made more effective with the ‘power with’, which is the ability to act together, and the ‘inner power’ which means relying on the sense of identity and dignity to mobilize for change (See ).

Table 3. Different ways of exercising power.

The power of agency, thus, suggests that in situations of domination, the problem is not that some people have power and others do not, but rather how those who are excluded can make use of their resources and sources of power to change their circumstances and effectively counterbalance the forces of domination in different social areas. Power is not static and un-changeable. During the evolution of a conflict, power is transformed: it is dynamic, permeable and may be influenced, because where there is domination, there is usually resistance and change (Foucault Citation1984).

Power resources include: material resources such as money and physical capital; moral support in the form of solidarity; control of information, social organization, including organizational strategies, social networks and alliances; human resources such as volunteers, staff and leaders with specific skills and knowledge; and cultural resources including previous experiences, understanding of the issues from the local perspective and the ability to initiate collective action. Success depends on the effectiveness with which agents activate these resources and direct them towards achieving their goals.

Agency is generally interpreted as the power of people to impact others. However, when power stays exclusively at the level of individuals and their interactions, it runs the risk of reproducing conditions of domination as it does not challenge rules or structures. Social transformations only occur when the power of agency impacts institutions and the world of ideas. Therefore, the power of agency must impact simultaneously on people (networks), institutions and frameworks (structures) and culture to influence a change in the different levels of domination.

Experiences in transforming environmental conflicts in Latin America

In we summarize some strategies that in our experience can help enhance the power of agency to impact on different forms of hegemonic power, thus contributing to the constructive transformation of socio-environmental conflicts. We now turn to discussing these strategies with examples from Latin America.

Figure 2. Strategies to impact the Personal (networks), Structural (institutions) y Cultural dimensions of domination. Source: Rodriguez et al. (Citation2015).

Impacting people and networks

Power networks are a common way in which dominant actors exercise their power in socio-environmental conflicts. Behind the scene negotiations, the co-optation of leaders and the divisions of local communities are part of the common tactics used by the private sector and governments in mining and/or development projects (Inturias and Aragón Citation2005; Padilla and Luna Citation2005). They are also common in the way environmental knowledge is constructed and institutionalized in environmental management through alliances between resource managers and certain sectors of the scientific community that legitimize the need for external control in environmental management (see for instance Rodríguez Citation2004). Something similar has happened in the formulation of climate change policy, where alliances between particular sectors of public policy making and the international academic community have determined the type of knowledge that is used for climate change negotiations and that which is left out (Ulloa Citation2011). Thus, one of the challenges in overcoming such power asymmetries in socio-environmental conflicts is to impact on these power networks in order for other views to have a place in decision-making and discursive formations.

A key issue in conflict transformation is capacity building on issues of social and political organization, local leadership, conflict theory and dialogue/negotiation tactics. Such was the case for instance in the widely known Water War in Bolivia in 2000, where the Bolivian government attempted to sanction a new Law on Privatization of Water and Sewage without local consultation. This law met with strong resistance and intense mobilization from the part of campesino and the indigenous peoples of Cochabamba, to the point that it could not be approved. Carlos Crespo Flores, who acted as adviser to the campesino and indigenous peoples in this conflict, explains that in this case it was crucial to work on four issues with the Cochabamba farming organizations to ensure successful negotiations: a) how to control or modify internal organization factors, b) how to increase awareness of external factors in the conflict, c) how to develop parallel actions to negotiations, and d) how to increase the technical knowledge of dialogue and negotiation procedures (Crespo Citation2005) (See for more details).

Table 4. Key factors in strengthening power of agency in the Water Way negotiations, Bolivia.

The Water War is renowned for the intense political and social mobilization that it generated through the development of press and media campaigns, lobbying, lawsuits and public demonstrations demanding respect for traditional water uses and customs (Nickson and Vargas Citation2002; Gutiérrez-Pérez Citation2014). But perhaps the most interesting aspect of this case was not the external strategies, but the internal ones developed by the local organizations to ensure negotiations in conditions of equity, and more importantly, to halt changes in the legislation.

Distinct from strategies that focus on overcoming domination in negotiations, such as the Water War, there are other initiatives in the region developing long-term political empowerment for conflict transformation. For example the ‘Diploma on conflict analysis and transformation, negotiation, advocacy and lobbying’ run by the ProPaz Foundation in Guatemala, is directed at ancestral authorities, leaders and young indigenous peoples (men and women) and seeks to strengthen local capacity to confront future conflicts, most of them socio-environmental conflicts.

ProPaz Foundation does not run the conflict transformation diploma as an academic course, but as an opportunity to contrast conflict theory with the participants’ own experience and knowledge on the topic, in order to find solutions to inequality that they experience in their daily lives. There is a follow up phase to support indigenous organizations immersed in specific conflicts in which participants receive technical assistance, advice and monitoring of their own practices and these are discussed with participating organizations as part of the capacity building process.

The entire process seeks to empower indigenous peoples to defend their territories and collective and individual rights. One strategy is to influence spheres of government and the other to legitimize leadership roles on these issues within their communities.Footnote4 Although, as in the case of the Water War in Bolivia, empowerment is aimed initially at strengthening the internal organization, the ultimate goal is to impact structural/institutional power.

Similarly, the Foundation for Democratic Change (FCD) in Argentina provides technical support to indigenous communities through workshops and joint advocacy processes, with the aim of building capacity and community organization as well as improving their conditions of participation in developing policies and resolving environmental conflicts. In particular, it supports indigenous communities in northern Argentina developing community protocols to be applied in consultations or when free, prior and informed consent is sought. Similar protocols have already been launched by other indigenous peoples in Latin America.Footnote5

Another way of impacting existing hegemonic power networks in socio-environmental conflicts is through the development of transformative knowledge networks that can challenge and help re-shape existing environmental policies through giving visibility and public legitimacy to marginaliszed knowledge.

Such is the case of knowledge networks that have been developed amongst different research institutes over the last decade in the Canaima National Park, Venezuela, in order to help reframe fire use policies in the area. Since the 1980s there has been a long-standing land use conflict in this national park related to the use of fire in the shifting cultivation and savannah burning by the Pemon indigenous peoples, both practices being considered by environmental managers as a threat to the watershed conservation functions of the protected area. Despite a variety of strategies developed by the State to change or eliminate the use of fire in agriculture and savannas (repression, environmental education, introduction of new cultivation techniques, and a fire control program) many Pemon, especially the elders and those living in more isolated communities, have continued to make extensive use of fire. In contrast, the younger Pemon have gradually become more critical of the use of fire and as a result, inter-generational tensions over this issue are becoming more frequent. The Pemon’s traditional knowledge has been key for illuminating new technical fire management knowledge that challenges conventional explanations of landscape change. This local knowledge, combined with results from studies of Pemon fire regimes, fire behavior ecology and paleo-ecological research, now inform a counter narrative of landscape change that is influencing a shift in environmental discourse and policy making towards an intercultural fire management approach (Rodríguez et al. Citation2013).

Impacting structural power (institutions)

Structural power goes beyond the exercise of power over others. It refers to more regulated modes of power that define social rules and interactions between people through institutions. Social actors are often positioned differently in relation to decision-making and procedures, which ends up affecting the interests of specific groups. The challenge is then to impact public institutions and frameworks in order to represent more fairly the different interests of society.

There are different ways to achieve this. One is through outright confrontation, as we saw above in the example of the Water War, impacting through political and social mobilization on laws, regulations and norms that have been created without consultation or that do not represent the differentiated rights of society. Although effective in the short-term, this strategy will not necessarily transform institutional structures in a profound way, unless macro legal frameworks are revised. The other way is to ensure greater representation of different sectors of society in the formulation of public policy in existing public institutions such as national and local assemblies or by creating new institutional arrangements where none exist, such as decision-making councils, co-management committees, round-tables or processes of consultation. However, the problem with this approach is that it often ends up co-opting local leaders or that participation takes place in a tokenistic way.

Therefore, in terms of conflict transformation it is important also to move towards public participation with an intercultural approach, where the focus is not to open up participation for marginalized sectors in already established institutions, but rather to acknowledge and strengthen existing customary decision-making and natural resources management approaches.

An example of this type of strategy is new instruments for territorial planning and management implemented in Bolivia since 2006, such as Indigenous and Campesino Territories (TIOCs), which were created as a result of changes in the model of the nation-state and a new form of democracy and citizenship that acknowledges cultural differences. TIOCs, apart from recognizing the ancestral ownership of land by indigenous peoples, gives them the legal mandate to manage their natural resources autonomously and with respect for their customary decision-making procedures. Yet, in order to conquer these new intercultural institutional arrangements, indigenous peoples in Bolivia have had to resort to a variety of strategies, from social and political mobilization, training and assessment with experts, advocacy strategies, to tactical negotiations with the state. As an illustration, in , we summarize the main strategies that have been used by the Monkoxi peoples in the TIOC of Lomerio, in order to transform socio-environmental conflicts in their territories, through challenging and impacting (structural) institutional power.

Table 5. Strategies used by the Monkoxi Peoples of Lomerio to impact on Institutional Power in order to transform socio-environmental conflict in their territories.

Even though since 2006, the Monkoxi peoples have had legal ownership of their lands, and are now demanding autonomous territorial rights, one of their greatest challenges continues to be strengthening their own customary territorial and natural resource governance systems in order to ensure a sustainable and just management of the territory (Inturias et al. Citation2016). Thus, in collaboration with a wide variety of partners that include Fundación Tierra, CEJIS, Universidad NUR, Grupo Confluencias and the University of East Anglia, they are currently working on strengthening their Indigenous Justice system as well as on training a new generation of leaders in indigenous autonomy related issues.

Impacting cultural power

One of the main challenges for many social groups who do not see themselves represented in dominant worldviews, is to alter the realm of social representation in order to protect and defend their own identity, through the creation of new meanings, norms and values. If over time, a sufficient number of people confirm and reaffirm the new meanings through the creation of counter-narratives or counter-discourses, systemic changes in cultural power can take place.

We refer, for example, to dominant views of development, to the way nation-state models define citizenship rights and to dominant climate change or environmental change discourses. Many actors and social movements in Latin America are creating new social meanings when they position themselves against mining or against infrastructure projects based on their own conceptions of the environment, the land and development (OSAL Citation2012). The changes that have occurred towards pluricultural nation states in Latin America in relation to development narratives like ‘Buen Vivir’ or towards new forms of territorial management, are the result of a long process of confrontation with certain sectors of society holding dominant development concepts and and of citizenship rights.

Yet, as said before, domination is continually being exercised in abstract and invisible ways, and indigenous communities themselves often have themselves controversial and shifting views of development and of environmental knowledge. Therefore, in order to impact cultural power, it is often necessary to strengthen local identity in order for alternative sustained meanings and values to emerge. The revitalization of local environmental knowledge and the reconstruction of local history are some of the actions that can help. Building visions of the future through community life plans, processes of self-demarcation or local territorial management also play a role.

In Latin America, there are valuable experiences in recovering the historical memory of indigenous peoples, made by the protagonists themselves, as part of strategies aimed at confronting the dominant development model and its tendency to erode and erase the identity of entire peoples. A case in point was the project to recover the historical memory of the Talamaqueño people in Costa Rica, led by the American historian Paula Palmer in the 1980s (Palmer Citation1994). The project sought to document the socio-economic changes experienced by the people in the region as well as conflicts with the State as lived and experienced by the Talamaqueño peoples themselves (Quezada Citation1990).

In Venezuela there is the experience of Pemon-Taurepan from Kumarakapay Village, located in Canaima National Park, Bolivar State, who in 1995, as a reaction against increasing pressure from development projects on their land, began compiling their own history through recording interviews with their elders. Later in 1999, through a process of self-reflection about their past, present and desired future, they consolidated this effort, giving birth a decade later to the first account written by indigenous peoples in Venezuela about their own history (Roroimokok Damuk Citation2010). This experience served as inspiration for the Pemon-Arekuna from Kavanayen, also from Gran Sabana, to begin a similar process in 2011, which is currently underway. Recently in Colombia, the Muinane Indigenous People underwent a similar process, which also culminated in a self-authored history book (Ancianos del Pueblo Féénemɨnaa Citation2017).

In Bolivia, there is the recent experience of the Monkoxi Peoples, in which participatory video was used to reconstruct the history of the struggle for autonomy and territorial rights, as part of a participatory analysis of conflicts in the management of the TIOC (Rodriguez and Inturias Citation2016). As a result of this process, the Union of Indigenous Peoples of Lomerio (CICOL), decided to put the history of the Monkoxi Peoples in writing thorough a community authored book that is now used as part of their communication strategy to advance their claim for territorial autonomy (Peña et al. Citation2016).

Incorporating local visions of the past and future are a cornerstone for the transformation of environmental conflicts. Contemporary environmental conflict analysis has a strong present time bias, which contributes to erasing collective identities.

Many indigenous peoples in Latin America are making these links between their past, present and future through the definition of their life plans, helping them to look ahead by reconnecting first with their past and their identity (Cabildo de Guambia Citation1994; Jansasoy and Perez-Vera Citation2006; COINPA Citation2008; Espinosa Citation2014).

In Box 1 we see for instance how the Pemon Taurepan visualized and defined a desired future, by reviving their past and carrying out a self-critical assessment of their current situation. This vision of the future has been key for them grounding a local well-being agenda that can help negotiate new development projects in their territory with greater clarity (Rodriguez Citation2016).

• A Pemon society with awareness of who we are, and with a sense of identity and of belonging.

• Knowledgeable about our history, culture, tradition and language.

• Owners of our land – territory, knowledge, culture and destiny.

• A society educated with ancestral and modern knowledge.

• A society that values its wise people (parents and grandparents).

• A respectful, hard-working, obedient, kind, courteous, cheerful, generous, harmonious, understanding society where there is love.

• A productive, autonomous society.

• A society that defends its rights and is ready to confront pressures from Venezuelan society.

Source: Roraimökok Damük (Citation2010).

In the case of socio-environmental conflicts, the reconstruction of local stories is also key in helping clarify disputes over environmental and landscape changes, which are often and simplistically attributed to local practices. Such is the case of the use of fire in Canaima National Park, noted above, where reconstruction of local histories have helped to make connect other social and environmental histories explaining how and why fire regimes have been altered over time. These include migration, the slave trade and death following colonial contact, combined with cyclical climate change, instead of current Pemon fire practices, as commonly explained in dominant narratives (Rodríguez et al. Citation2014).

Thus, affirming history from the local perspective can play an important role in developing environmental counter-narratives and counter-histories, which, in turn, by helping to change the collective way of thinking and seeing the environment, can help revalue and revitalize local knowledge and identities.

Concluding remarks

we see Ralco as the symbolic expression of the threat of modernity and progress to the indigenous people of Chile … we don’t want your progress to rub out our culture.

While we agree with Schlosberg’s and Carruthers’ argument for pushing the boundaries of environmental justice literature towards a capabilities approach, we would argue that at least in Latin America it is necessary to push the boundaries further. As clearly expressed in Namuncura’s words, and as we have argued, in Latin America indigenous peoples’ claims for the basic functioning of their communities and the integrity of their cultures are set within a wider anti-modernity agenda, which decolonial theory has managed to capture effectively. Such struggles speak of indigenous peoples’ desires to continue being different in a world dominated by modern, capitalist and individualistic values, in order to be able to continue living according to their own cosmogonies and well-being conceptions: a life centered in collective and communal values and inherited interrelations between nature and culture. This cannot be achieved within the existing dominant model of development and of production of knowledge.

Thus, as decolonial theorists would argue, at least in Latin America, environmental justice must necessarily engage with a politics of difference that is not simply based on the search for recognition or inclusion in dominant structures, such as the liberal nation state, but focused rather on the construction of ‘otherness’:

an “other” process of knowledge construction, an “other” political practice, and “other” social (and State) power and an “other” society; an “other” way to think and act in relation to, and against, modernity and colonialism. (Walsh Citation2007, 57)

As we have also argued in this paper, conflict transformation offers something additional, both to decolonial thought and to environmental justice theory and practice, to help decolonize environmental injustices. By paying particular attention to developing capacities to transform conflicts at the intercultural level in the different spheres of power, it can help to create the conditions for the construction of ‘otherness’ from the bottom up.

We have seen for instance how conflict transformation practice can help impact dominant power networks, through building counter-hegemonic networks that can enable indigenous peoples to negotiate projects or deliberate with other actors about the causes of conflicts, on a more equal standing. Capacity building in local organization, leadership and legal procedures, such as free, prior and informed consent, as well as in the conflict theory and negotiation procedures, has proven to be an indispensable first step to dialogue with others in conflict situations. Also, the development of counter-hegemonic knowledge networks, which open up spaces for local reflexivity on contested issues related to environmental change, such as the local use of fire, can play an important role in influencing a shift in environmental discourse and policy, by giving visibility to marginalized local environmental knowledge and legitimizing local environmental practices.

We have also seen that, as evidenced by the Bolivian case, it is possible to generate new intercultural political models and national environment and land management approaches, through the sustained and strategic political mobilization of indigenous peoples to impact public policy, legal, institutional or existing policy frameworks (structural power). But it is equally important to continue strengthening the customary territorial and natural resource management procedures in indigenous territories to ensure long-term sustainability and effective exercise of indigenous justice.

And finally, we have seen the important role that the revitalization of local knowledge and local identity plays in creating new meanings, values and norms (cultural power). Key strategies involve helping to rebuild local histories, revitalize environmental knowledge and build visions of the future, all indispensable for decolonization.

This approach requires a commitment from academia to participate in this transformation, undertaking as Lederach has said (Citation2008), a role in the architecture of change, knowing when and how to help impact each sphere of power, depending on the nature and dynamics of each conflict. The cases analysed here have shown that by impacting one of the spheres of power it is also possible to impact others. In some cases, depending on the nature of the conflict, it may be sufficient to concentrate efforts on a single sphere of power, while in other cases, in order to achieve the desired result, a simultaneous effort in all spheres may be necessary.

Beyond its contribution to the architecture of change with a ‘decolonial turn’, a conflict transformation approach also offers new avenues for future environmental justice research. The assessment of the impact of specific socio-environmental conflict transformation strategies (SCT) in the decolonization of power, knowledge and the being is still in its infancy. In this sense, the SCT framework can also be used in cross-country and cross-cultural comparisons to gain a deeper understanding of how transformative change happens on the ground, and which factors facilitate or limit such change. The empirical material presented in this paper offers an illustration of different types of transformative strategies that can be put into practice in order to contribute to greater environmental justice, by impacting different forms of hegemonic power. Much closer attention needs to be paid to the way in which distinct micro and macro political and economic contexts in each country affects the overall outcome of specific conflict transformation strategies.

For instance, it is no coincidence that the chances for advancing a decolonial political agenda (at least in terms of political reforms) over the last two decades have been greater in a country like Bolivia, with a majority of indigenous peoples, than for instance in Argentina or Chile, where most of its indigenous population was exterminated in the colonial period. This could mean that conflict transformation strategies that put a focus on decolonizing power can intrinsically have more traction in some countries than in others. At the same time, we need to pay attention to the complex and contradictory ways in which hegemonic power is exercised and to how this limits the effect of conflict transformation strategies.

Despite important recent structural changes in Bolivia, Ecuador and Colombia in the national constitutions in terms of restoring rights to indigenous peoples and even to Nature (e.g. Bolivia and Ecuador), such innovations have not been translated into real changes in environmental governance, such as ensuring greater local control over natural resource use. If anything, authoritarian approaches to resource extraction based on a capitalist logic of accumulation have continued or even expanded in these three countries over the last decade, through projects such as the Yasuni-ITT (Ecuador), the building of a new road in TIPNIS (Bolivia) and Arco Minero (Venezuela). In all three cases, these projects pose potentially devastating effects on the physical and cultural survival of indigenous peoples. A conflict transformation lens can help illuminate these contradictions, through a close examination of both the hegemonic and transformative power strategies used during the evolution of environmental justice struggles. Furthermore, doing this analysis with those experiencing environmental injustice can help them learn from the strategies used and the limitations encountered in the process to re-strategize and continue working towards the desired social changes.

An example of how the SCT Framework is used for this purpose can be found in the ‘Academic and Activist co-produced knowledge for Environmental Justice’ Project (ACKnowl_EJ) (http://acknowlej.org/). Here, power analysis, as outlined in this paper, combined with a new set of conflict transformation indicators, are being used in five different case studies in Bolivia, India and Turkey, to learn in conjunction with activists, the lessons experienced during environmental justice struggles (Temper et al. Citation2018). In the future we hope to share some new publications with results from this project, which should help assess further the practical use of this framework in decolonizing environmental justice in Latin America and beyond.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank our colleagues from Grupo Confluencias Juliana Robledo, Rolain Borel, Carlos Sarti, Diego Luna, Ana Cabria Mellace, Gachi Tapia, Volker Frank, Nicolas Lucas, Juan Dumas, Antonio Bernales, Jesvana Policardo and Pablo Lummerman, with whom over the years we have matured many of the ideas presented in this document. Our colleagues from the ACKnowl-EJ Project: Leah Temper, Ashish Kothari, Adrian Martin, Mariana Walter, Meena Pathak, Radhika Mulay, Daniela del Bene, Ethemcam Turhan, Cem Aidin, Begüm Özkaynak, Lena Weber and Rania Masri have provided very useful insights during project meetings and activities. The collaborative work we carry out in ACKnowl-EJ is possible thanks to the support of International Social Science Council (ISSC) through the Transformations to Sustainability Programme (Grant ISSC2015-TKN150317115354). Thanks also to Nicole Gross-Camp, Phoshendra Satyal and Saskia Vermeylen with who we have had the opportunity to discuss parts of this work and from whom we have received very useful feedback. And, last but not least, many thanks to three anonymous reviewers who provided by useful comments that significantly improved the quality of an earlier version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This includes: Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru and Venezuela.

2 The literal translation of ‘Buen Vivir’ in Quechua and Aymara languages is ‘To Live in Plenitude’. The Guari version, Teko porâ literarily means, ‘a good way of being’ or ‘a good way of life’, but as stated by the Aymara writer Fernando Huanacuni, from Bolivia, none of the literary translations of the term do justice to the depth of its meaning from an indigenous perspective. ‘Buen Vivir’ is a holistic concept rooted on principles and values such as harmony, equilibrium and complementarity, which from an indigenous perspective must guide the relationship of human beings with each other and with nature (or Mother Earth) and the cosmos.

3 Broadly speaking ‘the being’ is defined as the soul and essence of a person. The coloniality of the being refers to the impact of colonial technologies of subjectivation on the life, body, and mind of the colonized people, to the point of stripping them from their very essence and soul. Thus, the decolonization of the being involves forging new categories of thought, constructing new subjectivities and creating new modes of being and becoming that can lead to emancipation.

4 For more information see: http://www.propaz.org.gt/capacitacion-y-formacion

5 See for example the case of the Munduruku Consultation Protocol in Brasil: http://amazonwatch.org/assets/files/2014-12-14-munduruku-consultation-protocol.pdf

References

- Acosta, A. 2013. El Buen Vivir. Sumak Kawsay, una oportunidad para imaginar otros mundo. Barcelona: Icaria editorial.

- Acosta, A. 2015. Extractivismos y subdesarrollo. La maldición de la abundancia. Rebelión. 04-11-2015. Disponible en linea: http://www.rebelion.org/noticia.php?id=205247.

- Acosta, A., E. Gudynas, F. Houtart, H. Ramírez Soler, J. Martínez Alier, and L. Macas. 2011. Colonialismos del siglo XXI. Negocios extractivos y defensa del territorio en América. Barcelona: Icaria Editorial.

- Ancianos del Pueblo Féénemɨnaa. 2017. Ancianos que caminan y cuentan historias. Colombia: Consejo Regional Indígena del Medio Amazonas (CRIMA) y Forest Peoples Programme (FPP).

- Arts, B., and J. Van Tatenhove. 2004. “Policy and Power: A Conceptual Framework Between the ‘old’ and ‘new’ Policy Idioms.” Policy Sciences 37 (3–4): 339–356. doi: 10.1007/s11077-005-0156-9

- Botes, J. 2003. “Conflict Transformation: A Debate Over Semantics or a Crucial Shift in the Theory and Practice of Peace and Conflict Studies?” The International Journal of Peace Studies 8 (2): 1–27.

- Bullard, R. D., ed. 1983. Confronting Environmental Racism: Voices From the Grassroots. Boston: South End Press.

- Burdeau, G. 1985. Tratado de Ciencia Política. UNAM, México. Vol. II, tomo II.

- Cabildo de Guambia. 1994. Plan de Vida del Pueblo Guambiano. Popayan.

- Carruthers, D., ed. 2008a. Environmental Justice in Latin America. Problems, Promise and Practice. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. 329 pp.

- Carruthers, D. 2008b. “Introduction. Popular Environmentalism and Social Justice in Latin America.” In Environmental Justice in Latin America. Problems, Promise and Practice, edited by D. Carruthers. 329 pp. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Castro-Gómez, S., and R. Grosfoguel, eds. 2007. El giro decolonial Reflexiones para una diversidad epistémica más allá del capitalismo global. Bogotá: Siglo del Hombre Editores; Universidad Central, Instituto de Estudios Sociales Contemporáneos y Pontifi cia Universidad Javeriana, Instituto Pensar, 308 pp.

- COINPA. 2008. Plan de Vida Pueblos Huitoto e Inga. Documento de avance. Consejo Indígena de Puerto Alegría (COINPA): Colombia, Abril 2008.

- Crespo, C. 2005. “La negociación como dispositivo para reducir relaciones de dominación. Aspectos conceptuales y metodológicos.” En Encrucijadas Ambientales en América Latina. Entre el manejo y la transformación de conflictos por recursos naturales, edited by Hernán Correa y Iokiñe Rodríguez, 237–254. San José: Universidad para la Paz.

- Escobar, A. 1998. “Whose Knowledge, Whose Nature? Biodiversity, Conservation, and ThePolitical Ecology of Social Movements.” Journal of Political Ecology 5: 53–82. doi: 10.2458/v5i1.21397

- Escobar, A. 2003. “Mundos y conocimientos de otro modo» El programa de investigación de modernidad/colonialidad Latinoamericano.” Tabula Rasa. Bogotá - Colombia 1: 51–86, enero-diciembre de 2003. doi: 10.25058/20112742.188

- Escobar, A. 2010a. “América Latina en una encrucijada ¿Modernizaciones alternativas, postliberalismo o postdesarrollo?” En Saturno Devora a sus hijos. Mirada crítica sobre el desarrollo y sus promesas, edited by Víctor Breton, 33–84. Barcelona: Icaria Editorial.

- Escobar, A. 2010b. “Una ecología de la diferencia: igualdad y conflicto en un mundo glocalizado.” En Más allá del Tercer Mundo. Globalización y Diferencia, edited by Arturo Escobar, 123–143. Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia.

- Escobar, A. 2010c. Epistemologías de la naturaleza y colonialidad de la naturaleza. Variedades de realismo y constructivismo. Revista Cultura y Naturaleza, Jardín Botánico de Bogotá José Celestino Mutis, pp. 49–71.

- Espinosa, O. 2014. “Los planes de vida y la política indígena en la Amazonía peruana.” Anthropologica [online] 32 (32): 87–114.

- Foucault, M. 1971. “The Order of Discourse.” In Untying the Text: A Poststructuralist Reader, edited by R. Young, 48–78. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Foucault, M. 1984. “Space, Knowledge and Power.” In The Foucault Reader, edited by P. Rainbow, 239–256. New York: Penguin Books.

- Fraser, N. 1998. “Social Justice in the Age of Identity Politics: Redistribution, and Participation.” The Tanner Lectures on Human Values 19: 2–67.

- Galtung, J. 1969. “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research.” Journal of Peace Research, Vol.6, No.3, International Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO), London: Sage Publications, pp 167–191.

- Galtung, J. 1990. “Cultural Violence.” Journal of Peace Research, Vol.27, No.3, International Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO), London: Sage Publications, pp 291–305.

- Galtung, J. 2004. Trascender & Transformar. Una introducción a la resolución de conflictos. México: M&S Editores.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gudynas, E. 2010a. “La senda biocéntrica: valores intrínsecos, derechos de la naturaleza y justicia ecológica.” Tabula Rasa. Bogotá - Colombia 13: 45–71, julio-diciembre 2010.

- Gudynas, E. 2010b. Tensiones, contradicciones y oportunidades de la dimensión ambiental del Buen Vivir, En: I. Farah H. y L. Vasapollo, (coords) “Vivir bien: ¿Paradigma no capitalista?”. La Paz: CIDES-UMSA y Plural.

- Gudynas, E. 2011. “Desarrollo y sustentabilidad ambiental: diversidad de posturas, tensiones persistentes.” En La Tierra no es muda: diálogos entre el desarrollo sostenible y el postdesarrollo, edited by A. Matarán, y F. López, 69–96. Granada: Universidad de Granada.

- Gudynas, E. 2012. Estado compensador y nuevos extractivismos. Las ambivalencias del progresismo sudamericano. Nueva Sociedad, No. 237.

- Gutiérrez-Pérez, J. 2014. “Latin American Narratives of Sustainability: Opportunities for Engagement Through Films.” International Journal of Sustainable Development 17 (2): 160–175. doi: 10.1504/IJSD.2014.061790

- Huanacuni Mamani, F. 2010. Vivir Bien / Buen Vivir. Convenio Andrés Bello, Instituto Internacional de Investigación y CAOI, La Paz, 2010.

- Inturias, M., and M. Aragón. 2005. “David y Goliat. Los Weenhayek y el consorcio petrolero Transierra, Bolivia.” En Encrucijadas Ambientales en América Latina. Entre el manejo y la transformación de conflictos por recursos naturales, edited by H. Correa and I. Rodriguez, 257–270. San José: Universidad para la Paz.

- Inturias, M., I. Rodriguez, H. Valderomar, and A. Peña, eds. 2016. Justicia Ambiental y Autonomía Indígena de Base Territorial en Bolivia. Un dialogo político desde el Pueblo Monkox de Lomerio. Bolivia: University of East Anglia, Universidad Nur, Grupo Confluencias and Ministerio de Autonomía.

- Jansasoy, J., and A. Perez-Vera. 2006. “Plan de Vida: Propuesta para la supervivencia Cultural, Territorial y Ambiental de los Pueblos Indigenas.” The World Bank Environment Department 30 pp.

- Lander, E., ed. 2000. La colonialidad del saber: eurocentrismo y ciencias sociales. Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

- Lawhon, M. 2013. “Situated, Networked Environmentalism: A Case for Environmental Theory From the South.” Geography Compass 7 (2): 128–138. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12027

- Lederach, J. P. 1995. Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures. New York: Syracuse University Press.

- Lederach, J. P. 2003. The Little Book of Conflict Transformation. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

- Lederach, J. P. 2008. La imaginación moral. El arte y el alma de construir la paz. Bogotá: Grupo Editorial Norma, 284 pp.

- Leff, E., ed. 2001. Justicia ambiental: Construcción y defensa de los nuevos derechos ambientales culturales y colectivos en América Latina. México: UNEP.

- Leff, E. 2003. Latin American Environmental Thought: A Heritage of Knowledge for Sustainability. ISEE Publicación Ocasional, South American Environmental Philosophy Section, No. 9.

- Leff, E. 2004. Racionalidad Ambiental y Diálogo de saberes: significancia y sentido en la construcción de un futuro sustentable. Polis, Revista de la Universidad Bolivariana, Santiago de Chile, año/vol 2, numero 007.

- Long, N., and J. D. Van Der Ploeg. 1989. “Demythologizing Planned Intervention: An Actor Perspective.” Sociologia Ruralis 29 (3/4): 226–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.1989.tb00368.x

- Méndez, A. 2008. “Los derechos indígenas en las constituciones latinoamericanas.” Cuestiones Políticas 24 (41): 101–125.

- Mignolo, W. 2008. “Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option: A Manifesto.” Subaltern Studies: An Interdisciplinary Study of Media and Communication, 2 February. http://subalternstudies.com/?p=193.

- Nickson, A., and C. Vargas. 2002. “The Limitations of Water Regulation: The Failure of the Cochabamba Concession in Bolivia.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 21 (1): 99–120, January 2002. doi: 10.1111/1470-9856.00034

- Nussbaum, M. 2011. Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- OSAL. 2012. Número Especial de la Revista del Observatorio Social de América Latina (OSAL) sobre Movimientos socio-ambientales en América Latina. Año XIII N° 32 - Noviembre de 2012. Disponible en linea. http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/osal/20120927103642/OSAL32.pdf.

- Padilla, C., and D. Luna. 2005. “Conflictos mineros en Chile: Poder económico versus Poder social. El caso de Minera los Pelambres.” En Encrucijadas Ambientales en América Latina. Entre el manejo y la transformación de conflictos por recursos naturales, edited by Hernan Correa y Iokiñe Rodríguez, 135–146. San José: Universidad para la Paz.

- Palmer, P. 1994. “Self-history and Self-identity in Talamanca.” En Cultural Expression and Grassroots Development. Cases From Latin America and the Caribbean, edited by Charles David Kleymeyer, 39–55. Colorado: Lynne Riener Publishers, Inc.

- Pellow, D. 2007. Resisting Global Toxics: Transnational Movements for Environmental Justice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Peña, A., P. Tubari, L. Chuve, M. Chore, and C. Ipi. 2016. Historia de Lomerio. El camino hacia la libertad. Universidad de East Anglia, Universida NUR, CICOL. Bolivia, Julio 2016.

- Quezada, J. R. 1990. “Historia Oral en Costa Rica. Génesis y estado actual.” Estudios Sobre las Culturas Contemporáneas 3 (9): 173–197.

- Quijano, A. 2000. “Coloniality of Power and Eurocentrism in Latin America.” International Sociology 15: 215–232. doi: 10.1177/0268580900015002005

- Rodríguez, I. 2004. “Conocimiento indígena vs. científico: el conflicto por el uso del fuego en el Parque Nacional Canaima, Venezuela.” Interciencia 29 (3): 121–129.

- Rodriguez, I. 2016. “Historical Reconstruction and Cultural Identity Building as a Local Pathway to “Living Well” Amongst the Pemon of Venezuela.” In Cultures of Wellbeing. Method, Place and Policy, edited by S. White and C. Blackmore, 260–280. Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Rodríguez, I., R. Gasson, A. Butt-Colson, A. Leal, and B. Bilbao. 2014. “Ecología Histórica de la Gran Sabana (Estado Bolívar, Venezuela) entre los siglos XVIII y XX.” En Antes de Orellana. Actas del III Encuentro Internacional de Arqueología Amazónica, edited by Stephen Rostain, 113–121. Quito: Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Embajada de EEUU.

- Rodriguez, I., and M. Inturias. 2016. “Cameras to the People Reclaiming Local Histories and Restoring Environmental Justice in Community Based Forest Management Through Participatory Video.” Alternautas 3 (1): 32–49.

- Rodriguez, I., M. Inturias, J. Robledo, C. Sarti, R. Borel, and A. Cabria. 2015. “Abordando la Justicia Ambiental desde la Transformación de Conflictos: experiencias en América Latina con Pueblos Indígenas.” Revista de Paz y Conflictos 2 (8): 97–128.

- Rodríguez I., B. Sletto, B. Bilbao, I. Sánchez-Rose and A. Leal. 2013. “Speaking of Fire: Reflexive Governance in Landscapes of Social Change and Shifting Local Identities.” Journal of Environmental Policy Making and Planning 38 (5): 1–20. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2013.766579.

- Roroimökok Damük. 2010. La Historia de los Pemon de Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Fundación Futuro Latinoamericano, Inwent y Forest Peoples Programme. Ediciones IVIC. Caracas, Venezuela, 124 p.

- Santos, B. de Sousa. 2008. Another Knowledge is Possible: Beyond Northern Epistemologies. London: Verso.

- Santos, B. de Sousa. 2010. Descolonizar el saber reinventar el poder. Montevideo: Ediciones Trilce.

- Santos, B. de Sousa, J. Arriscado, and M. P. Meneses. 2008. “Introduction: Opening Up the Canon of Knowledge and Recognition of Difference.” En Another Knowledge is Possible: Beyond Northern Epistemologies, edited by Boaventura De Sousa, vx–ixii. London: Verso.

- Schlosberg, D. 2007. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements and Nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schlosberg, D. 2013. “Theorising Environmental Justice: The Expanding Sphere of a Discourse.” Environmental Politics 22 (1): 37–55. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2013.755387

- Schlosberg, D., and D. Carruthers. 2010. “Indigenous Struggles, Environmental, Justice, and Community Capabilities.” Global Environmental Politics 10 (4): 12–35, November 2010. doi: 10.1162/GLEP_a_00029

- Smith, L. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed books.

- Temper, L., M. Walter, I, Rodriguez, A. Kothari, E. Turhan. 2018. “A Perspective on Radical Transformations to Sustainability: Resistance, Movement and Alternatives.” Sustainability Science 13 (3): 747–764. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0543-8.

- Tubino, F. 2005. “La interculturalidad crítica como proyecto ético-político”, En: Encuentro continental de educadores agustinos. Lima, 24–28 de enero de 2005. http://oala.villanova.edu/congresos/educación/lima-ponen-02.html.

- Ulloa, A. 2011. “Políticas globales del cambio climático: nuevas geopolíticas del conocimiento y sus efectos en territorios indígenas.” En Perspectivas Culturales del Clima, edited by Astrid Ulloa, 477–493. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- Viaña, J. 2009. La Interculturalidad como Herramienta de Emancipación. Bolivia: Instituto Internacional de Integración/Convenio Andrés Bello.

- Visvanathan, S. 1997. A Carnival for Science: Essays on Science, Technology and Development. London: Oxford University Press.

- Walsh, C. 2005a. La interculturalidad en la educación. Lima: Ministerio de Educación DINEBI.

- Walsh, C. 2005b. “Interculturalidad, conocimientos y decolonialidad.” Signo y Pensamiento. Perspectivas y Convergencia 46 (24): 31–50.

- Walsh, C. 2007. “Interculturalidad y colonialidad del poder. Un pensamiento y posicionamiento “otro” desde la diferencia colonial.” En El giro decolonial Reflexiones para una diversidad epistémica más allá del capitalismo global, edited by Santiago Castro-Gómez y Ramón Grosfoguel, 308 p. Bogotá: Siglo del Hombre Editores; Universidad Central, Instituto de Estudios Sociales Contemporáneos y Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Instituto Pensar.

- Young, I. 1990. Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton, NY: Princeton University Press.