ABSTRACT

Since the 2000s, the proliferation of Global Health Initiatives such as the Global Fund have dramatically changed the field of global health. The European Union and several of its Member States have played an important role in the development of the Global Fund and have contributed considerable budgets to it. While the Fund has been successful in fighting priority diseases, it has also been criticized for impacting negatively on countries’ health systems, which provoked a debate on health system strengthening (HSS) within the organization. Drawing on a literature review, aid statistics, interviews at headquarter and field level, and document analysis, this article researches the relation between EU donors and the Global Fund, with an explicit focus on the HSS debate. The findings indicate a ‘love-hate relationship’. EU donors have loved the Global Fund’s innovative institutional set-up and its ‘saving lives’ approach involving quick results. However, over the years they have become more critical about its narrow focus, advocating a shift towards more HSS. Whereas this has been partly successful at headquarters level, most notably the incorporation of concrete HSS commitments in the Global Fund’s strategic documents, challenges at local level constrain their translation into funding and implementation measures.

Introduction

The European Union (EU) and its Member States (hereafter ‘EU donors’) provided 25.5% of all Development Assistance for health (DAH) in the period 2002–2016 (IHME Citation2018). In addition to aid through bilateral programs of Member States, the European Commission and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), a considerable part of European DAH is channeled through multilateral funding. In the past, the major health-related multilateral organizations were the World Health Organization, UN Agencies, like UNICEF and UNFPA, and the World Bank. However, since 2000, the proliferation of so-called Global Health Initiatives (GHIs) has dramatically changed the global health scene. These initiatives focus on disease-specific interventions and are funded and governed by multiple public and private entities. One of the most important GHIs is the Global Fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria (hereafter ‘the Global Fund’ or ‘Fund’), which was launched in 2002.

At the beginning of the 2000s, the launch and success of Global Health Initiatives such as the Global Fund drew renewed attention for the longstanding debate on vertical (disease-specific) versus horizontal (overall strengthening of health systems) approaches within international health assistance (Mills Citation2005). The vertical approach implies that most funding and attention goes to disease-specific interventions. This often involves setting up parallel structures that focus on that disease, by using ‘planning, staffing, management, and financing systems that are separate from other services’ (Travis et al. Citation2004, 901). The advantage of this approach is that it delivers quick, visible and measurable results. Within the horizontal approach, the focus lies on strengthening basic health care needs and the wider health system. Here, the idea is to ‘work through existing health-system structures’ (Ibid.) and to strengthen them. This is claimed to be more sustainable in the long term, although results are less easy to measure.

While the Global Fund has been effective in fighting disease, its focus has also come under scrutiny. Critics stressed the unintended negative consequences of the GHIs on the health systems of poor countries (Garrett Citation2007; Lancet Infectious Diseases Citation2007; Biesma et al. Citation2009). This has led to renewed attention to HSS (Hafner and Shiffman Citation2013) and specifically also to a debate within the Global Fund on the extent to which it should focus on HSS.

This article explores the relationship between the EU donors and the Global Fund with an explicit focus on the debate on Health System Strengthening (HSS). The Global Fund has transformed the way (European) donor assistance for health is channeled to developing countries (Brugha Citation2005). The EU and several of its Member States have played an important role in the Fund’s development and have contributed considerable budgets to it. Of all the multilateral organizations, the Global Fund received the most DAH from EU donors: between 2002 and 2016, 48% of all European DAH has been transferred through multilateral organizations, of which 30% went to the Global Fund (IHME Citation2018).

At the same time, however, EU donors tend to incorporate HSS as a priority in their policy strategies on health and development (Belgian Directorate General for Development and Be-cause Health Platform Citation2008; Danida Citation2009; Council of the European Union Citation2010; European Commission Citation2010; HM Government Citation2011; Ministère des Affaires Etrangères et de Développement International Citation2017). The conclusions of the Council of Ministers about the ‘EU role in global health’ even explicitly state that EU donors should ‘act together in all relevant internal and external policies and actions by prioritizing their support on strengthening comprehensive health systems in partner countries’ (Council of the European Union Citation2010, 2)

European pleas for HSS seem to contradict their major role in the Global Fund, as the latter has a disease-specific approach and its efforts on HSS have been limited. This ambiguity in the European approach towards the Fund constitutes the main puzzle addressed in this article. Rollet and Amaya (Citation2015) touch upon this ambiguity, stating that ‘the EU’s progressive move to such an [horizontal] approach could have jeopardized its engagement with the Global Fund’ (p.12). They suggest a potential explanation, by anticipating a ‘progressive move’ of the Global Fund towards HSS, which could strengthen the coherence of the EU’s policy and the interaction between both organizations. However, the authors have not elaborated on this and the suggestion of an EU ‘progressive move’ within the Global Fund has not been substantiated. While considerable research has been done on the Global Fund, research into its relation with the EU, and specifically the question of horizontality versus verticality, has been scarce. In this article, we aim to take the debate one step further by examining more systematically and empirically the relation between the EU and the Global Fund, and specifically the question on the ‘progressive move’ towards the ‘horizontalization’ of the Fund.

Methods

Given the near-absence of literature on this topic, we have opted for an abductive research approach. Abduction stems from the pragmatist research tradition, which advocates problem-driven and complexity-sensitive research (Cornut Citation2009). Abduction reasons at an intermediate level between deduction (where a framework is imposed) and induction (where findings build on empirics) (Friedrichs and Kratochwil Citation2009). It involves a continuous interaction between theory and empirics, whereby literature review, data generation, data analysis and research design mutually influence each other in a cyclical research process. Abductive research often starts from an empirical puzzle. In this case the research builds on puzzling observations during the lead author’s field research for a broader study on EU donors’ approaches on international health assistance, where interviewees at European agencies complained about the negative effects of the Global Fund on countries’ health systems. As EU donors themselves contribute significantly to the Global Fund, we wanted to better understand this relation.

This research process involved several methods that were used during two phases. During a first, explorative phase, interviews were conducted with 31 donor representatives: three at headquarters level (March–April 2015 and December 2016) and 28 at local level of which eight were in the DRC (November 2015, December 2016 & February–April 2017), seven in Ethiopia (December 2015), seven in Uganda (February–March 2017) and six in Mozambique (March–April 2017). The local level concerns four Sub-Saharan African countries that are relevant because the discussion on HSS is highly prominent in these countries, given the fragile nature of their public health system and their high dependency on aid for health financing. Also, a significant number of EU donors are heavily involved in the health sector in these countries. Most interviewees were EU and MS officials, and three were officials from non-EU donor countriesFootnote1. These explorative interviews were recorded and fully transcribed.

In a second phase, additional and more specific information was gathered on the EU donors’ relationship with the Global Fund. We decided to mainly focus on the European Commission, the UK, France, Germany, Denmark and Belgium, not only for reasons of feasibility but also because these include the biggest European contributors to the Global Fund (infra ) and also some smaller donors which from the exploratory phase appeared to have a clear vision on health assistance. Together, these six donors cover all the five European constituencies within the Global Fund.Footnote2

This phase involved several methods. A literature review was conducted to better understand the launch and development of the Global Fund and the debate on HSS within it. Furthermore, we made a descriptive statistical analysis of DAH by the EU donors and the Global Fund, based on data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). To analyze EU donors’ role in the HSS debate, we conducted a document-analysis of relevant policy and background papers of the selected EU donors and the Global Fund. Lastly, additional semi-structured interviews were conducted in May-June 2017 with eight people at headquarters levelFootnote3. Again, interviews were recorded and fully transcribed. Interviewees generally express the views of their employer, although their evaluations are sometimes more explicit and less diplomatic than in official documents.

Based on the empirical information gathered during these two phases, several themes were identified that express certain arguments about the European engagement with the Global Fund. These smaller themes were then grouped into bigger themes, such as ‘reasons to fund the Global Fund’, ‘discussions on HSS at headquarters level’, ‘perceptions of Global Fund and HSS at country level’. This initial analysis was done through a close reading by the lead author, while the empirical data and the resulting findings were extensively discussed, refined and elaborated with the co-authors. Subsequently, these findings were presented at two international conferences involving experts in EU development and Global Health policy respectively, and the article was finalized taking into account relevant peer feedback.

The remains of this paper are organized as follows. First, we elaborate on the HSS debate within the Global Fund. Thereafter, we focus on the relationship between EU donors and the Global Fund, claiming that EU donors have been attracted by the Fund’s innovative institutional set-up and its ‘saving lives’ approach, but that over the years they have become more critical about its vertical approach and have attempted to ‘horizontalize’ the Fund. The third part discusses some remaining challenges, including limited implementation and limited European coordination. Finally, we summarize and discuss the main findings.

The HSS debate in the Global Fund

As mentioned above, there has been a longstanding but unresolved debate in international health between horizontal and vertical approaches. In response to the technical, vertical programs in the 1960s and 1970s, the WHO’s Alma Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care of 1978 articulated the need to focus on basic healthcare systems to reach ‘health for all’ by 2000 (World Health Organization Citation1978). This comprehensive primary healthcare approach was quickly criticized for being too broad and idealistic and was replaced by a focus on selective primary health care, involving a limited number of cost-effective interventions (Cueto Citation2004). During the 1990s, the switch from earmarked project funding to supporting the whole health sector through Sector Wide Approaches (SWAps) marked a new shift towards horizontality. Around 2000 however, the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the launch of GHIs made the pendulum swing back to vertical programs.

The Global Fund, launched in the light of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, has been the most successful GHI. With the availability of antiretroviral therapies since 1996, HIV/AIDS became a treatable disease in North America and Europe, bringing an end to ‘AIDS exceptionalism’ in the West. However, as antiretrovirals were not affordable in developing countries, the case for exceptionalism shifted to the international stage (Smith and Whiteside Citation2010). Advocacy groups and CSOs profoundly influenced the international mobilization for the epidemic, stressing the human rights of affected people (De Cock, Jaffe, and Curran Citation2011; Smith Citation2017). In addition, the securitization of HIV/AIDS as a global threat also increased attention to the epidemic (Smith and Whiteside Citation2010). All this created a favorable context in which Western politicians wanted to make antiretrovirals available for all, which entailed the launch of the Global Fund in 2002. While the fund originated in the context of AIDS exceptionalism, it was decided to focus on malaria and TB as well.

As the Global Fund became an influential organization over the years, some unanticipated adverse side effects on countries’ health systems became apparent. Several authors claimed that the GHIs had negative consequences on poor countries’ health systems, by fragmenting their health systems and distorting their national health policies (e.g. Garrett Citation2007; Lancet Infectious Diseases Citation2007; Biesma et al. Citation2009). A few years after their launch, proponents of HSS thus started to argue that GHIs have picked the ‘low hanging fruit’ and that their focus should be extended towards strengthening the broader health system (Hill et al. Citation2011). Although it has been recognized that in some cases the Global Fund’s vertical approach can have positive spillover effects on the wider health system (Atun et al. Citation2011; Rasschaert et al. Citation2011), several studies find that the overall impact on the wider health system has been limited or even negative (Biesma et al. Citation2009; Marchal, Cavalli, and Kegels Citation2009; WHO Maximizing Positive Synergies Collaborative Group Citation2009). Whatever the outcome of this (yet unresolved) debate may be, our point in this article is not to provide evidence for the extent to which the Global Fund might have strengthened or weakened recipient countries’ health systems, but rather to understand how EU donors deal with the common criticism that the Global Fund’s vertical approach is detrimental for HSS.

In reaction to the critiques, and following the example of the Vaccines Alliance GAVI, Round 5 of the Global Fund (in 2005) included for the first time a specific category for HSS. However, there was a lot of debate on this within the Global Fund Board. For opponents of HSS, the allocations towards HSS went too far, while proponents of HSS claimed that the ‘health system activities’ contributed only to specific programs, rather than strengthening the system as a whole (Hill et al. Citation2011). Only three out of 30 HSS applications were approved and according to the Technical Review Panel, there was insufficient clarity and guidance about the development and evaluation of HSS proposals (McCoy et al. Citation2012). At the same time, other actors influenced the debate as well. At the request of the World Bank, a comparative study of the Global Fund and the World Bank AIDS programs was conducted, which argued that both organizations should focus on their comparative advantages, recommending that the Global Fund focus on disease-specific interventions, leaving HSS interventions to the World Bank (Shakow Citation2006). Despite CSOs urging to keep HSS interventions as a specific category, the separate channel for HSS funding disappeared again in 2006 (Ooms, Van Damme, and Temmerman Citation2007; Hill et al. Citation2011). However, the topic remained on the agenda and suggestions were tabled to transform the Global Fund to fight HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria into a Global Health Fund (Ooms et al. Citation2008; Cometto et al. Citation2009). In 2009, plans were made to set up a Health System Funding platform between the Global Fund, GAVI and the World Bank ‘to coordinate, mobilize, streamline and channel the flow of existing and new international resources to support national health strategies’ (Hill et al. Citation2011, 1). This plan faced significant opposition as well and in the end the platform was never implemented. According to McCoy et al. (Citation2012), this failure was also due to the global financial crisis and ‘skepticism about the credibility of HSS strategies, interventions and measurements of progress’ (p.11).

Over the years, there has thus been a constant struggle within the Global Fund on the issue of HSS. This has gradually entailed more attention for this issue. However, despite a number of steps to slowly ‘de-verticalize’ its structure and activities, HSS mostly remained a secondary concern for the Fund during the first decade of the 2000s, due to internal opposition as well as opposition from other organizations (McCoy et al. Citation2012). Several authors have claimed that GHIs like the Global Fund interpret HSS in a narrow, instrumental way, using well-targeted and specific interventions with clear, measurable outcomes (Marchal, Cavalli, and Kegels Citation2009; van Olmen et al. Citation2012; Storeng Citation2014). This is in strong contrast to a broader conceptualization of HSS focusing on social, societal and political dimensions (van Olmen et al. Citation2012).

The limited progress on HSS is also apparent from the aid budgets. Based on the IHME database we calculated the Fund’s contribution to HSS. The DAH for HSS in this database falls into two categories (IHME Citation2017). First, sector-wide support (HSS/SWAP) that goes into a pooled fund for the health sector and includes non-earmarked funds that contribute to the broad national health sector such as improving monitoring and evaluation of a health issue or better coordination among all stakeholders. Second, aid that improves the health system but is nevertheless targeted towards specific health-focused areas such as HIV/AIDS or maternal, newborn, and child health. The latter could be named health system support, which should be distinguished from health system strengthening as it concerns less comprehensive changes to the health system and all its building blocks (Chee et al. Citation2013).

From these data, it appears that in 2016 only 2% of DAH of the Global Fund went to HSS/SWAP (IHME Citation2018). Although the Fund contributes an important share of its budget to health systems support (20%), its relative importance has not changed over the years (it was already 23% in 2003 and has remained stable since then).

More recently, however, the Global Fund made more substantive strategic changes. In 2012, a new funding model was introduced, which would align better to the needs, plans and processes of the partner countries compared to the previous round-based model. While the new funding model led to an increase in funding requests and approvals for HSS programs, there were nevertheless remaining challenges at country level, due to the lack of operational support mechanisms and processes (Abejero Citation2015). The Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014–2016 created a window of opportunity for the horizontalization of the Global Fund, as it clearly demonstrated that strengthening health systems is necessary for future epidemic preparedness. Consequently, there was more attention for HSS in the discussions on the Global Fund’s new strategy for 2017–2022. In response to the challenges raised concerning HSS in the New Funding Model, the Technical Evaluation Reference Group (TERG) of the Global Fund commissioned the Danish-based consultancy company Euro Health Group for a thematic review of HSS (Abejero Citation2015). Building on this review and other inputs, the TERG developed recommendations towards the Global Fund. These were taken into account in the new strategy, which arguably meant a big leap forward towards HSS (Abejero Citation2016).

EU donors and the Global Fund

EU donors have played an important role in the development of the Global Fund and have contributed considerable budgets to it. Interestingly, this seems to contradict European pleas for HSS, as the Global Fund has a disease-specific approach and its efforts on HSS have been limited. In this part, we aim to understand this puzzle by pointing at two main aspects. Firstly, we claim that EU donors have been attracted by the Fund’s innovative institutional set-up and its ‘saving lives’ approach, through which quick results could be attained in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Secondly however, Eu donors have attempted to ‘horizontalize’ the Fund, by making their voice heard in the HSS debate in the Global Fund outlined above.

The attractiveness of the Global Fund

As mentioned above, both the successful activism on HIV/AIDS and the language of securitization and globalization created a favorable political environment in which Western politicians wanted to make antiretrovirals available for all. EU donors wanted to take the lead in this but realized that this required a huge scale-up of resources which would not be possible through bilateral efforts only (interviews HQ 4, 8 & 10). Consequently, they wanted to create an international dynamic that also incorporated important non-European partners such as the US and the private sector.

In a context of growing critique on the effectiveness of aid and on ‘traditional’ development aid through bilateral and UN agencies, as well as the credibility problems that had plagued the WHO, the Global Fund appeared to be an attractive and innovative alternative. Its model was considered to be concrete and ambitious. There was the intention to ‘not (do) business as usual, i.e. to be a quicker financing mechanism than the traditional bilateral and multilateral donor agencies’ (Brugha Citation2005). In line with the increased trend of using cost-effectiveness analysis as a basis for international health priority-setting, it adopted a performance-based funding model (McCoy et al. Citation2012). Furthermore, it was considered to be less bureaucratic than UN organizations, given its ‘light-touch’ it does not have in-country offices (Brugha and Walt Citation2001; interviews HQ 6 & 10). Instead, local Country Coordination Mechanisms (CCMs) - consisting of representatives from government, the private sector, donor agencies, civil society and communities living with HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria - were developed to identify, manage and evaluate the priorities and funding needs. The Global Fund was also lauded for its inclusiveness, given the structured participation of civil society and the involvement of the private sector both in the amongst its board members and in the CCMs (interviews HQ 7, 10 &11).

This innovative funding model proved to be successful: given its specific focus, the Fund succeeded in achieving quick results. Donors also welcomed the public visibility of the organization (Brugha Citation2005; interviews HQ 7 & 11). The Global Fund secretariat has been very successful in demonstrating its impact by calculating for example how many lives are saved. As mentioned by one respondent, they are ‘highly skilled marketeers’ (HQ 6). This ‘saving lives’ approach has made it even more attractive for donors to continue investing in the organization, as they can easily get ‘value for money’ and the results can easily be communicated as successes to the general public. The transparency of the Global Fund has also been considered a great asset, including the set-up of the Office of the Inspector General, an independent control instance (Brugha Citation2005, interviews HQ 7 &11). More recently, the Global Fund has started to work a lot on scaling-up domestic resources in partner countries, which is supported as well by the European partners (interviews HQ 9 &11). All these factors contributed to the success story of the Global Fund, which became far more popular than the World Health Organization. Arguably, the latter has struggled for decades to convince its member states of its effectiveness and its reputation deteriorated further after its slow response to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014–2016.

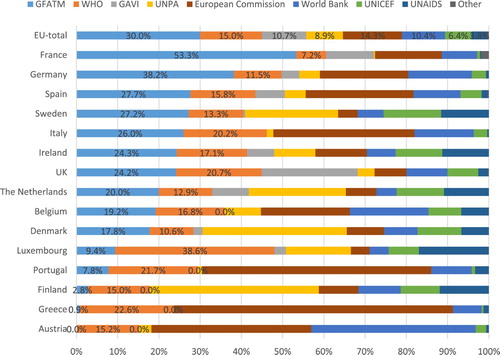

Being such an attractive organization, EU donors have channeled a considerable part of their DAH through the Global Fund. shows the distribution of multilateral DAH. In total, 30% of all European multilateral DAHFootnote4,Footnote5 has been channeled through the Global Fund, which makes it by far the biggest multilateral channel for EU donors. Germany and France have even contributed respectively 53.3% and 38.2% of all their multilateral DAH through the Global Fund. Remarkably, the WHO has only received 15% of multilateral DAH, as 10 EU donors have provided more money to the Global Fund than to the World Health Organization.

Figure 1. Multilateral DAH per Channel. Data from IHME Citation2018.

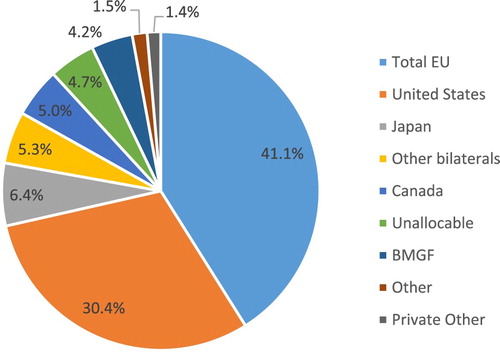

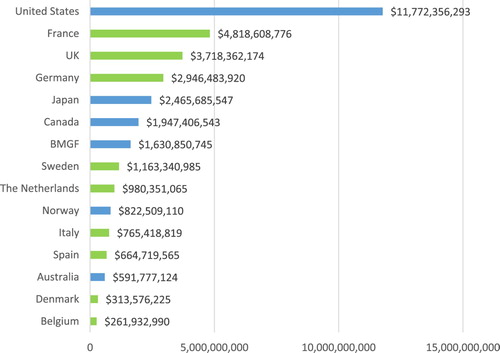

Given their considerable contributions, the EU and EU Member States have been responsible for 41.1% of all DAH channeled through the Global Fund over the period 2002–2016 (). shows the top 15 donors who have contributed the most DAH through the Global Fund between 2002–2016, including nine EU Member States.

Figure 2. DAH distributed through the Global Fund 2002–2016. Data from IHME Citation2018.

Figure 3. Top 15 donors of the Global Fund 2002–2016. Data from IHME Citation2018.

Increasing critique on the vertical stance of the Global Fund

Already at the start of the Global Fund, there were varying positions among the board members on HSS. While most of the EU donors supported HSS in their bilateral programs by promoting the SWAPs since the mid-1990s, HSS was less of a priority for the United States and the private sector. However, these tensions did not seem to be problematic at that time, as the Global Fund funding was meant to be ‘additional’ and ‘complementary’ to existing aid from multilateral and bilateral agencies (Brugha and Walt Citation2001; interview HQ 10 & 11). Consequently, HSS could still be a priority of EU donors through their bilateral support.

However, as the Global Fund became such an influential organization, these tensions soon became more problematic. Already in 2005, research by Brugha et al. (Citation2004) briefly described how several country representatives working for EU donors were critical about the Global Fund. As they themselves were supporting the SWAPs, they claimed that the Fund was ‘reverticalising health systems and forcing a disease-specific approach’ (p. 97). This critique is still present, as became apparent during our field research in the DRC, Uganda, Mozambique and Ethiopia. Several interviewees working for European agencies expressed frustrations about the Global Fund’s negative impact on countries’ health systems. As illustrated in the quotes below, some explicitly stated that the Global Fund has been undermining or even ‘destroying’ the efforts of EU donors on HSS. Consequently, they also criticized the incoherence of their headquarters by supporting HSS in bilateral programs and at the same time funding an organization that is undermining it.

What is a tragedy is that many of the same EU donors that are saying this is unacceptable are also funders to the Global Fund that actually undermines what we are doing. (MOZ 3).

[And we should] be able to say to the Global Fund, well, we give you money, but this destroys what we have done in our programme here in Congo. We should be coherent. (DRC 7)

While originating at country level, these critiques have also reached the headquarters. EU donors have increasingly criticized the vertical approach of the Global Fund and made it a priority to reform it from within by trying to ‘horizontalize’ it. Several relevant policy documents emphasize the objective to promote the HSS approach within the Global Fund. The European Commission stresses that ‘a comprehensive approach including all priorities is the only efficient one’ and that ‘the EU should promote this approach in global financing initiatives such as the GFATM and the GAVI’ (European Commission Citation2010). The Belgian strategy mentions that although ‘the decision to support programmes which combat specific diseases may be justified in certain cases’, it is needed to take several principles into account in supporting them, including ‘the level to which these programmes offer a long term guarantee that they reinforce the local healthcare system rather than destabilise it’ (Belgian Directorate General for Development and Be-cause Health Platform, Citation2008, 25–26). Denmark underlines that it ‘supports some of the GHPs but will condition its support on increasing adherence to the Paris Declaration principles’ (Danida Citation2009, 19). In their organizational strategy for the Global Fund 2014–2017 they furthermore explicitly point out that they ‘would welcome a gradual development in the direction of GFATM becoming a more general and less vertical health development fund’ (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark Citation2014).

The topic of HSS and GHIs has also been the subject of discussion at parliamentary level. In its resolution on ‘health care systems in Sub-Saharan Africa and global health’, the European Parliament (Citation2010) argues that a ‘vertical approach can under no circumstances be a substitute for a sustainable horizontal approach to basic health’. Furthermore, the resolution urges the Commission ‘to supplement its aid for vertical funds with recommendations designed to encourage ‘diagonal’ measures to support basic health care in the countries concerned’. The International Development Committee of the UK House of Commons (Citation2014) states that ‘DFID’s main international partners do not give the development of health systems the same priority as DFID does’. As Department for International Development (DFID) increasingly relies on multilaterals, DFID was recommended to ‘conduct a detailed assessment, by country, of the extent to which existing funding arrangements enable its health systems strengthening objectives to be met’.

Also, most European respondents at headquarters-level were very vocal on this objective, as can be illustrated with the following quotes.

The approach with these Global Health Initiatives is to develop the health systems angle or format, or mandate. Pushing and building coalitions in the Global Fund, and GAVI, to do that. (HQ2)

But Germany also expects very strongly from the Global Fund and GAVI that they are enhancing their contribution towards system strengthening. And this means that the two organizations should find ways to target more of the money they have into HSS work. But they should also be careful about how they do their business. […] to make sure that the way they operationalize the money does not harm with regards to HSS. (HQ4)

European efforts to horizontalize the GF

As EU donors had a preference for more HSS, they have tried to make use of their presence in the board of members to influence the Global Fund’s strategies to move more in this direction. When the new funding model was discussed in 2011–2012, one of the priorities of European partners was to make sure that the budget would be better aligned with the national health strategies and the planning cycles of partner countries (The Federal Government of Germany Citation2013, 13; interviews HQ 1 & 3). These efforts paid off as the new funding model is indeed based more on country needs, plans and processes than the previous rounds-based model.

Also during the discussions on the new strategy for 2017–2020, EU donors were among the main advocates to urge the Global Fund to further refine its approach to HSS. France and Germany were particularly vocal on this issue. They published a non-paper claiming that comprehensive HSS should not be treated as a byproduct, but as an integral part of the Global Fund’s strategy and activities (interviews HQ 3, 5 &7). These efforts proved to be successful, as HSS for the first time has been elevated to the level of a Global Fund strategic objective. Although using different wording, ‘building resilient and sustainable systems for all’ became one of the four priorities in the strategy for 2017–2022 (The Global Fund Citation2017c). The new strategy thus clearly reflected the Global Fund’s evolving approach towards HSS (Abejero Citation2016). According to several respondents, it meant a big leap forward towards HSS (interviews HQ 4, 5, 8 & 9).

On top of advocating for more HSS at the board of members level, another, more indirect way of influencing the Global Fund’s HSS activities has been the German and French specific Technical Assistance programs. France developed the so-called 5% initiative, whereby 5% of total French contributions to the Fund is earmarked for projects in French-speaking African countries, managed by French technical agencies. The reason behind this initiative was the realization that French-speaking countries often had difficulties with accessing the funds of the Global Fund, not only because the latter’s templates and log-frames are in English, but also because they are ‘designed in a very American way’ (interview DRC 4). The objective of the 5% initiative is therefore to mobilize expertise from the French-speaking world to ‘facilitate the implementation of grants, support the definition of strategies in those countries and promote good grant governance, with an overall focus on capacity-building’ (Citation5% Initiative n.d.). Very often, the technical assistance is linked to HSS (interview HQ 8, DRC 4). The German technical assistance program is called BACKUP and has three components: support to the CCM, support for risk and grant management and support for HSS (GIZ Citationn.d.). Through this program, German technical assistance has been used to develop funding requests, in which there is special attention for HSS (interview HQ 4).

Continuing challenges at local level

Despite the above-mentioned efforts to focus more on HSS, challenges remain, mainly at the local level. Firstly, the implementation of the HSS commitments seems limited. Secondly, European involvement and coordination on the follow-up of the Global Fund’s activities at the local level has been limited.

Lip service versus implementation

Following the increased attention for HSS at strategic level, one respondent rightly stated that ‘now the devil really lies in the detail of the operationalization’ (interview HQ 4). Changes at the local level have continued to be difficult. The New Funding Mechanism that was launched in 2012 resulted in a significant increase in funding requests and approvals for cross-cutting HSS programming. However, as became clear in the reviews of the concept notes by the Technical Review Panel, there was a large variety in the quality of HSS proposals and there were challenges ‘specifically with respect to ensuring that the necessary support mechanisms and processes are operational at the country level’ (Abejero Citation2015). Consequently, there was a missed opportunity in most countries to address wider health system constraints.

This has been corroborated during our field work at the country level, which revealed that there still is a perception among several respondents that the HSS efforts of the Global Fund remain lip service:

Even the Global Fund now has a special fund for strengthening health systems, but if you see how the money is utilized, it is just to strengthen the vertical programs, like malaria. (UG 4)

In the end it is also their own policy that they want to align and harmonize, but in practice it is not so much. (MOZ 1)

The interviews were conducted in March-April 2017, only shortly after the new strategy was launched. Perhaps these perceptions might change following the full implementation of the new strategy. Nonetheless, while most interviewees at headquarters’ level were positive about this strategy, some interviewees were rather skeptical (interviews HQ 6,7 & 11). More specifically, they held a critical stance towards the Global Fund’s preference for the term ‘RSSH’ instead of the more commonly used ‘HSS’. As clarified in their documents, ‘systems for health, differently from health systems, do not stop at a clinical facility but run deep into communities and can reach those who do not always go to health clinics, particularly the most vulnerable and marginalized’ (The Global Fund Citation2017a, 4). The Global Fund thus envisages to focus beyond the formal health system (the Ministry of Health, subnational bodies of governance and the clinical services), bringing its products ‘to the last mile’ (interviews HQ 5 & 8). Some interviewees claimed that the choice for this term once again shows the Global Fund’s narrow, technical interpretation of HSS, only focusing on the ‘hardware’ that is needed to bring the products to the last mile, instead of a holistic approach towards the health system (interviews HQ 6, 7 & 11). While stating that it aims to work beyond the formal health system, there is thus a risk that the Global Fund ignores the formal health system.

Limited European involvement and coordination at the local level

In case the EU donors want the Global Fund to walk the talk about HSS, they will also have to follow up and influence the activities of the Global Fund at local level. Switzerland, France and Germany released a discussion paper in November 2016, in which they recommended a review of the role and functions of the CCM (The delegations of Switzerland, France and Germany Citation2017). Among other things, they claim that country dialogues should reach beyond disease-specific stakeholders and that HSS experts should play a more prominent voice in CCMs. They also see a role for themselves, claiming that ‘Germany, Switzerland and France will promote health systems strengthening through their bilateral programmes in-country, their direct involvement as CCM members in certain countries and as Board members of multilateral institutions’ (Delegations of Switzerland, France and Germany Citation2017, 5).

However, our data signal mixed experiences with regards to the local follow-up by and influence of EU donors on the Global Fund. One way to influence the Fund’s local activities is to have a seat at the CCM. The specific set-up of the CCM differs in each country, but in most countries, only one or two bilateral donors are represented within the platform. One of these seats usually goes to the United States, who were present in 71 CCMs in 2016 (The Global Fund Citation2017b). When it comes to the EU donors, the French delegations are the most active, as they were present in 30 CCMs. France has several regional health cooperation counselors who are based at the French embassies and have the specific task to follow-up the multilateral funding for the country and neighboring countries (interview HQ 8). The EU is also relatively active with a seat in 16 CCMs. However, as can be seen in the , other EU donors very often do not participate in the CCMs. Donors such as Denmark and Sweden were not present in any of the CCMs.

Table 1. CCM presence. Data from The Global Fund Citation2017b.

These numbers do not tell the whole story, as donors could also be involved in discussions on the Global Fund without having a seat in the CCM. This was for example the case in the DRC, where the EU delegation has been quite actively following the Fund’s activities (interviews HQ 11, DRC 2 & 7). The delegation was concerned about the ‘destructive’ effects of the Global Fund supply chain policies on the national system for the procurement and distribution of medicines. They raised these concerns with their colleagues in Brussels, who then made it an issue of concern in Geneva, which led to a profound debate on this topic. Furthermore, the Belgian delegation in the DRC has made it a priority to engage the Global Fund as much as possible in the donor-wide coordination group in the health sector (the GIBS; interview DRC 2). However, these seem to be exceptions. Moreover, the examples of active involvement without having a seat illustrate that much depends on dedicated individuals who have a specific commitment to this issue. The majority of local respondents stated that it has been very challenging to closely follow the activities of the Global Fund, simply because of time constraints and lack of human resources (interviews DRC 2, 3 & 6; MOZ 1,2,4 & 5; UG 1, 2, 3 & 5; ETH 1 & 2). Except for France, there seem to be few institutional incentives and expectations from headquarters to be involved in Global Fund processes and/or to coordinate for this purpose. As a result, the Fund does not seem to be a priority within people’s busy schedules. Several respondents agreed that EU donors’ influence in the Global Funds’ decisions and activities at the local level remains limited and needs to be strengthened, as can be illustrated with the following quote.

I think we also have to become better in really engaging in the CCM. And because only if we are there and if we dedicate staff, resources and time to being really engaged in CCM and country dialogues around the Global Fund, we can make the change happen. (HQ 4)

Conclusion and discussion

This article has focused on the relation between EU donors and the Global Fund, with a specific focus on the debate on HSS, illustrating the ‘love-hate relationship’ between both actors. On the one hand, EU donors have always loved the Global Fund, as they prefer the innovative, institutional set-up of the organization as well as their ‘saving lives’ approach that generates quick results. However, over the years EU donors have become more critical about the Fund’s narrow focus, which is why they started advocating for a progressive shift towards more HSS. This had led to some successes at headquarters' level, resulting in clear commitments towards HSS in the Global Fund’s strategic documents. We have shown how EU donors struggle because of the tension between the attractiveness of the Global Fund’s bias towards ‘verticalism’ and the (perceived) need of a more horizontal approach.

This article aimed to understand this ambiguity. In essence, the key tension is that ‘horizontalizing’ the Fund remains challenging, because the ‘specificities’ that make the Global Fund so successful and attractive, are precisely those that also impede moves towards HSS. First, the inclusive partnership model of the Fund has been lauded because it brought together a large variety of actors to fight together against infectious diseases. However, since the Fund’s establishment it has been clear that this partnership of multiple stakeholders with different agendas and priorities embodies internal dissonance and ambiguity around issues such as HSS (McCoy et al. Citation2012). Over the years, progress on this domain has been hampered partially because important board members – mainly the US and the private sector - were not that much involved in HSS. Second, the ‘saving lives’ and ‘value for money’ approaches certainly contributed to the success story of the Global Fund. However, as raised already by McCoy et al. (Citation2013), ‘quantifying the saving of lives’ could lead to a narrow focus on selected, measurable interventions, undermining investment in interventions that cannot easily be measured in terms of saved lives, such as capacity building and institutional development. As one of the respondents claimed, the idea that one needs to strengthen national systems clashes with a quite dominant idea within the Global Fund that ‘we have no time for that because we have to save lives’ (interview HQ 11). Lastly, the ‘light’ structure of the Global Fund, without in-country offices, is part of its core identity (Brugha Citation2005). However, the absence of in-country offices also has its downsides as it limits participation in relevant forums such as health sector planning meetings or donor coordination groups, and hence limits knowledge of the local context.

As it is unlikely that these factors and tensions will change, HSS seems a topic for ‘an ongoing and probably endless debate’ (interview HQ 5). Nevertheless, EU donors can still successfully influence this endless debate, as became apparent in the discussions on the new funding model and new strategy which made HSS a more prominent priority. In order for this rhetorical commitment to translate into concrete funding and implementation, EU donors should also follow-up and influence the Fund’s activities at the local level. For the moment, this does not seem to be happening for most EU donors as it depends on the commitment of individuals. Neither is there significant and institutionalized European coordination on this issue.

Although we have attempted to create a balanced and comprehensive image of the role of EU donors in the Global Fund and the debate on HSS within it, based on a variety of empirical data sources, the exploratory nature of this research means that we could not elaborate on all aspects. While addressing some limitations of this study, we therefore propose some suggestions for future research. Firstly, the image of an overarching vision on HSS among all EU donors might have to be nuanced. While our data clearly show a general preference for HSS among all EU donors, which constitutes one of the major findings of this article, it has also been suggested that not all EU donors are as outspoken on this issue. For instance, while Germany and France have recently been very vocal on HSS, the UK appears to be less so (partly because of its focus on ‘value-for-money’), and some other Europeans might be situated somewhere in between. This issue, which will become all the more relevant in the context of Brexit, should be analyzed more deeply in future research. Moreover, although we have focused on the most relevant donors in terms of vision and budget, further research could analyze the remaining EU donors. Secondly, a closer look at the domestic politics and institutions within European donor countries may also reveal different opinions on the Global Fund and HSS. For example, interviewees with experience in countries with fragile health systems seem to have more outspoken views on these issues than those who have only worked at headquarters level. How exactly divergent opinions within countries synthesize into aggregate country positions is beyond the scope of this article. Further research could therefore go beyond the general finding of a European preference for HSS and how this entails a love-and-hate relationship with the Global Fund, and zoom in on more nuanced differences between and within EU Member States.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The three HQ interviewees were representatives from the EU and Belgium and an academic researcher. For the partner countries, it concerned officials who are active in the health sector. More specifically, for the DRC: representatives from Belgium, the UK, France, the EU (two), Sweden and USAID, as well as a former official of the EU delegation in the DRC; for Uganda: representatives from Sweden (two), Belgium (two), the Netherlands, the UK and USAID; for Mozambique: the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, the UK and Switzerland, and a former official of the Danish delegation; for Ethiopia: the EU (three), the Netherlands, the UK and Italy (two).

2 EU donors are represented at the Global Fund through their presence in the board of members, which consists of 28 constituencies: 10 donor constituencies, 10 implementer constituencies and eight non-voting members. The EU donors are spread among five constituencies: (1) the European Commission, Belgium, Italy, Portugal and Spain, (2) France, (3) Germany, (4) the United Kingdom and (5) the Point Seven constituency (Denmark, Norway, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, and Sweden).

3 We interviewed six representatives of the selected EU donors who are closely involved in their country’s relations with the Global Fund (from Belgium (two), the European Commission, France, Germany and Denmark), in addition to a former European Commission official and a staff member of the Global Fund secretariat. The relevant department of DFID (UK) was not able to accept my (repeated) requests for an interview. While this is regrettable, information on the UK’s involvement with the Global Fund could be found through other documentation, including policy documents and external perceptions.

4 The numbers only include the funding of 15 EU donors, as the IHMI database does not provide separate data for other EU donors. However, their contributions can be considered negligible in relation to the total amount of European DAH.

5 The European Commission is not considered to be a source in the IHME database, but a channel. However, in case a funding flow has two intermediary agencies, only the ultimate agency is defined as the channel. Consequently, it is not possible to track how much money from European Member States is going to the Global Fund via the European Commission.

References

- 5% Initiative. n.d. “The Global Fund and the 5% Initiative.” http://www.initiative5pour100.fr/en/about-us/the-global-fund-and-the-5-initiative/.

- Abejero, Nathalie. 2015. “The TERG Recommends Measures to Enhance Health Systems Strengthening.” Global Fund Observer, no. 278 (24 Dec 2015).

- Abejero, Nathalie. 2016. “New Strategy for 2017-2022 Reflects The Global Fund’s Evolving Approach to Health Systems Strengthening.” Global Fund Observer, no. 278 (13 Jan 2016).

- Atun, Rifat, Sai Kumar Pothapregada, Janet Kwansah, D. Degbotse, and Jeffrey V Lazarus. 2011. “Critical Interactions Between the Global Fund – Supported HIV Programs and the Health System in Ghana.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 57 (Supplement 2): 72–76. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318221842a

- Belgian Directorate General for Development and Be-cause Health Platform. 2008. “Policy Note: The Right to Health and Healthcare”.

- Biesma, Regien G., Ruairí Brugha, Andrew Harmer, Aisling Walsh, Neil Spicer, and Gill Walt. 2009. “The Effects of Global Health Initiatives on Country Health Systems: A Review of the Evidence from HIV/AIDS Control.” Health Policy and Planning 24 (4): 239–252. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp025

- Brugha, Ruairí. 2005. “Editorial: The Global Fund at Three Years - Flying in Crowded Air Space.” Tropical Medicine and International Health 10 (7): 623–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01437.x

- Brugha, Ruairí, and Gill Walt. 2001. “A Global Health Fund: A Leap of Faith?” BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 323 (July 2001): 152–154. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7305.152

- Brugha, Ruairí, Martine Donoghue, Mary Starling, Phillimon Ndubani, Freddie Ssengooba, Benedita Fernandes, and Gill Walt. 2004. “The Global Fund: Managing Great Expectations.” Lancet 364 (9428): 95–100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16595-1

- Chee, Grace, Nancy Pielemeier, Ann Lion, and Catherine Connor. 2013. “Why Differentiating between Health System Support and Health System Strengthening Is Needed.” The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 28 (July 2012): 85–94. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2122

- De Cock, Kevin M., Harold W. Jaffe, and James W. Curran. 2011. “Reflections on 30 Years of AIDS.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 17 (6): 1044–1048. doi: 10.3201/eid/1706.100184

- Cometto, Giorgio, Gorik Ooms, Ann Starrs, and Paul Zeitz. 2009. “A Global Fund for the Health MDGs?” The Lancet 373 (May 2009): 1500–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60835-7

- Cornut, Jérémie. 2009. “Pluralism in IR Theory : An Eclectic Study of Diplomatic Apologies and Regrets Pluralism in IR Theory : An Eclectic Study of Diplomatic Apologies and Regrets”.

- Council of the European Union. 2010. Council Conclusions on the EU Role in Global Health. Brussels: Council of the European Union.

- Cueto, Marcos. 2004. “The Origins of Primary Health Care and Selective Primary Health Care.” American Journal of Public Health 94 (11): 1864–1874. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.11.1864

- Danida. 2009. “Health and Development, a Guidance Note to Danish Development Assistance to Health”.

- Delegations of Switzerland France and Germany. 2017. “The Global Fund Country Coordinating Mechanism - Fit for Implementing the New Strategy within the SDGs Area? Position Paper by Switserland, Germany and France.” http://www.aidspan.org/gfo_article/three-board-donor-constituencies-call-global-fund-review-role-ccms.

- European Commission. 2010. “Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: The EU Role in Global Health”.

- European Parliament. 2010. “Resolution of 7 October 2010 on Health Care Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa and Global Health”.

- The Federal Government of Germany. 2013. “Shaping Global Health, Taking Joint Action, Embracing Responsibility - The Federal Government’s Strategy Paper.” http://www.bmg.bund.de/fileadmin/dateien/Publikationen/Gesundheit/Broschueren/Screen_Globale_Gesundheitspolitik_engl.pdf.

- Friedrichs, Jörg, and Friedrich Kratochwil. 2009. “On Acting and Knowing: How Pragmatism Can Advance International Relations Research and Methodology.” International Organization 63 (4): 701–731. doi: 10.1017/S0020818309990142

- Garrett, Laurie. 2007. “The Challenge of Global Health.” Foreign Affairs 86 (1): 14–38.

- GIZ. n.d. “BACKUP Health.” https://www.giz.de/expertise/html/7195.html.

- The Global Fund. 2017a. “Building Resilient and Sustainable Systems for Health through Global Fund Investments Information Note”.

- The Global Fund. 2017b. “Country Coordinating Mechanism 2016 Composition Data.” https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/archive/country-coordinating-mechanism/.

- The Global Fund. 2017c. “The Global Fund Strategy 2017-2022: Investing to End Epidemics”.

- Hafner, Tamara, and Jeremy Shiffman. 2013. “The Emergence of Global Attention to Health Systems Strengthening.” Health Policy and Planning 28 (1): 41–50. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs023

- Hill, Peter S, Peter Vermeiren, Katabaro Miti, Gorik Ooms, and Wim Van Damme. 2011. “The Health Systems Funding Platform: Is This Where We Thought We Were Going?” Globalization and Health 7 (16): 1–10.

- HM Government. 2011. Health Is Global: An Outcomes Framework for Global Health 2011–2015. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_125671.pdf.

- IHME. 2017. Financing Global Health 2016: Development Assistance, Public and Private Health Spending for the Pursuit of Universal Health Coverage. Seattle, WA: IHME.

- IHME. 2018. “Development Assistance for Health Database 1990–2017”.

- International Development Committee - House of Commons. 2014. “Strengthening Health Systems in Developing Countries”.

- Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2007. “The Global Fund : Growing Pains.” Lancet Infectious Diseases 7 (November 2007): 695.

- Marchal, Bruno, Anna Cavalli, and Guy Kegels. 2009. “Global Health Actors Claim to Support Health System Strengthening - Is This Reality or Rhetoric?” PLoS Medicine 6 (4): 1–5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000059

- McCoy, David, Carlos Bruen, Peter Hill, and Dominique Kerouedan. 2012. “The Global Fund: What Next for Aid Effectiveness and Health Systems Strengthening?” Global Health Observer, no. April.

- McCoy, David, Nele Jensen, Katharina Kranzer, Rashida A Ferrand, and Eline L Korenromp. 2013. “Methodological and Policy Limitations of Quantifying the Saving of Lives : A Case Study of the Global Fund ‘ S Approach.” PLoS Medicine 10 (10): e1001522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001522

- Mills, Anne. 2005. “Mass Campaigns Versus General Health Services: What Have We Learnt in 40 Years about Vertical Versus Horizontal Approaches?” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83 (4): 315–316.

- Ministère des Affaires Etrangères et de Développement International. 2017. “La Stratégie de La France En Santé Mondiale”.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. 2014. “Danish Organisation Strategy for The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria 2014-2017,” 1–17. http://fngeneve.um.dk/en/~/media/fngeneve/Documents/Health/Organisation Strategy GFATM Final.pdf.

- van Olmen, Josefien, Bruno Marchal, Wim Van Damme, Guy Kegels, and Peter S Hill. 2012. “Health Systems Frameworks in Their Political Context: Framing Divergent Agendas.” BMC Public Health 12 (774): 1–13.

- Ooms, Gorik, Wim Van Damme, Brook K Baker, Paul Zeitz, and Ted Schrecker. 2008. “The ‘Diagonal’ Approach to Global Fund Financing: A Cure for the Broader Malaise of Health Systems?” Globalization and Health 4 (6): 1–7.

- Ooms, Gorik, Wim Van Damme, and Marleen Temmerman. 2007. “Medicines Without Doctors: Why the Global Fund Must Fund Salaries of Health Workers to Expand AIDS Treatment.” PLoS Medicine 4 (4): 605–608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040128

- Rasschaert, Freya, Marjan Pirard, Mit P Philips, Rifat Atun, Edwin Wouters, Yibeltal Assefa, and Bart Criel. 2011. “Positive Spill-over E Ects of ART Scale up on Wider Health Systems Development : Evidence from Ethiopia and Malawi.” Journal of the International AIDS Society 14 (Suppl 1): 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-S1-S3

- Rollet, Vincent, and Ana B Amaya. 2015. “The European Union and Transnational Health Policy Networks: A Case Study of Interaction with the Global Fund.” Contemporary Politics 21 (3, SI): 258–272. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2015.1061245

- Shakow, Alexander. 2006. “Global Fund – World Bank HIV/AIDS Programs: Comparative Advantage Study.” Prepared for the Global Fund and The World Bank Global HIV/AIDS Program.

- Smith, Julia H. 2017. Civil Society Organizations and the Global Response to HIV/AIDS. New York: Routledge.

- Smith, Julia H., and Alan Whiteside. 2010. “The History of AIDS Exceptionalism.” Journal of the International AIDS Society 13 (1): 1–8, BioMed Central Ltd. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-47

- Storeng, Katerini T. 2014. “The GAVI Alliance and the ‘Gates Approach’ to Health System Strengthening.” Global Public Health 9 (8): 865–879. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.940362

- Travis, Phyllida, Sara Bennett, Andy Haines, Tikki Pang, Zulfiqar Bhutta, Adnan A Hyder, Nancy R Pielemeier, Anne Mills, and Timothy Evans. 2004. “Overcoming Health-Systems Constraints to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals.” Lancet (London, England) 364 (9437): 900–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16987-0

- WHO Maximizing Positive Synergies Collaborative Group. 2009. “An Assessment of Interactions between Global Health Initiatives and Country Health Systems.” Lancet (London, England) 373 (June): 2137–2169.

- World Health Organization. 1978. “Declaration of Alma-Ata: International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978”.