ABSTRACT

The major objective of this study is to assess the complementarities of the measures adopted by Nigeria vis-à-vis the Economic Community of West African States Agricultural Policy and the Comprehensive Africa Agricultural Development Program (ECOWAP/CAADP). Within this context, the study examines the extent to which Nigeria has leveraged its agricultural sector to roll away food insecurity in terms of increased productivity and competitiveness. In 2003, African leaders initiated the CAADP to revitalize and leverage the agricultural sector to drive development on the continent. Consistent with the CAADP, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) developed its agricultural policy named ECOWAP in 2005. In the same vein, Nigeria developed a number of policy documents in line with the overarching thrusts of the ECOWAP/CAADP to boost the productivity and competitiveness of its agricultural sector. This study employs both primary and secondary data, which are analyzed through logical inductive method to evaluate the extent to which Nigeria has achieved the ECOWAP/CAADP commitments. It finds that despite the various programs evolved by the Nigerian government to leverage its enormous agricultural potentials, the country is neither on track to achieving food security nor becoming a major player in the global food market.

1. Introduction

Food and nutrition security issues occupy a central place on the global agenda for sustainable development. Despite global efforts to ensure adequate availability of food for the purpose of ending hunger and improving overall nutrition of the people through the instrumentality of sustainable agricultural practices, food insecurity is still pervasive in Africa. FAO et al (Citation2019) report that the food situation in Africa has been most alarming since 2015 as almost all the sub-regions have high prevalence of undernourishment (PoU). The steady increase in the prevalence of undernourishment has tended to reverse the gains recorded as at 2015 with the possibility of derailing the projections for the attainment of zero hunger on the continent by 2030. This scenario, thus, constitutes a great challenge to the continent and threatens the actualization of Malabo Goals 2025 as well as the achievement of the various benchmarks of Goal 2 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Recent United Nations estimates put the number of people suffering from chronic under-nutrition in Africa at 257 million with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for 237 million of this number (FAO and ECA. Citation2018). This figure indicates a worsening food security scenario. An analysis of the current figure of undernourished people showed an exponential rise as 32.6 million more people slipped into undernourishment in sub-Saharan Africa with more than half of this figure residing in West Africa (FAO and ECA Citation2018).

The food security situation in West Africa is even more alarming. It is estimated that between 36 and 40 million people in the West African sub-region are food insecure, which means that they suffer from both undernourishment and chronic malnutrition. The prevalence of undernourishment rose from 10.4 percent in 2010 to 14.7 percent in 2018 (FAO et al. Citation2019). The picture is even more dismal if the fast increasing population of the sub-region with attendant expansion in food demand and the reduction in food productivity are factored into the equation. The total population of the West African sub-region is projected to reach 420 million in 2020 (Zoungrana Citation2013). The projected population growth would definitely widen the sub-region’s food deficit and lead to the deterioration of its nutritional status. This food security gap constitutes a great challenge to the sub-regional body, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS),Footnote1 in view of the thrust of the Chapter 4, Article 25 of its treaty, which recognizes agriculture and food security as one of the main areas of cooperation among member-states (ECOWAS Commission Citation2010).

It was principally to deal with food insecurity and achieve some level of food sovereignty that ECOWAS floated its common agricultural policy, ECOWAP in 2005. The idea was to build on the tenets of the ECOWAS treaty, the then Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the Comprehensive Africa Agricultural Development Program (CAADP), as basis to mobilize sub-regional collaboration to actualize food security. Thus, the thrust of the ECOWAS Common Agricultural Policy (ECOWAP) in tandem with CAADP centres on the promotion of modern and sustainable agriculture that would enhance productivity and competitiveness, guarantee food security and provide decent incomes to farmers and other agricultural workers (ECOWAS Commission Citationn.d.; Crola Citation2015). The achievement of these lofty objectives is anchored on regional integration, which is driven by the harmonization of national interventionist plans in the agricultural sector.

A major mechanism for national buy-in to ECOWAP/CAADP is the formulation and implementation of a national agricultural investment plan (NAIP). Nigeria has been making efforts in this direction. It has evolved a number of programs aimed at restructuring the agricultural sector to achieve two interrelated objectives, namely to be food secure and to convert agriculture into a major foreign exchange earner for the country. The underlying idea is to diversify and boost the Nigerian economy so that it would not be overly dependent on crude oil for its foreign exchange earnings. Undoubtedly, Nigeria has formulated and flagged off several agricultural programs even before the articulation of continental agenda for agriculture.

Although there is an appreciable number of studies on food security in relation to Africa and the West African sub-region, their focus tends to be general and with emphases on manmade or nature-induced impediments to achieving food sufficiency and sovereignty on the continent (Sasson Citation2012; Jalloh et al. Citation2013; Mbow et al. Citation2014; Bini Citation2016). Studies with narrower focus on countries in the West African sub-region as well as Nigeria have often evaluated food security within the context of national and subnational efforts at food production without holistic linkages to sub-regional and continental agricultural initiatives and policies (Abu Citation2012; Dupraz and Postolle Citation2013; Simson and Tang Citation2016; Bini Citation2016; Nwozor, Olanrewaju, and Ake Citation2019). Thus, there is a dearth of studies on how sub-regional and continental agricultural initiatives have affected the trajectory of government policies on agricultural productivity and by extension the prospects of leveraging on agriculture to achieve food security and roll back poverty.

This paper undertakes the key task of assessing the complementarities of the measures that Nigeria has formulated and implemented under the auspices of its national agricultural programs vis-à-vis the overall objectives of ECOWAP/CAADP. Furthermore, the paper evaluates the extent to which Nigeria’s subscription to the tenets of ECOWAP/CAADP has driven its national programs in agriculture and food security as well the overall contributions of these programs to the actualization of food security in the country. The important contribution of this paper in line with its key problematique of assessing the trajectory of Nigerian government’s policy towards food security within the context of ECOWAP is the finding that there is a disconnect between expectations and outcomes in terms of meeting both national and sub-regional food security goals. Thus, despite the various programs evolved by the Nigerian government to leverage its enormous agricultural potentials in the implementation of ECOWAP/CAADP, it has not met the critically important minimum benchmarks in the key areas necessary to modernize its agricultural sector and thus achieve food sufficiency and security.

The paper is structured into 6 sections. While section 1 introduces the problematique of the paper and the knowledge gap it envisages to fill, section 2 presents an overview of ECOWAP/CAADP. A brief literature review is captured in section 3. The methodology is discussed in section 4. The assessments of findings and results are presented in section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes and presents relevant policy implications.

2. Brief overview of the ECOWAP/CAADP

The discussions that eventually crystallized into the ECOWAS Agricultural Policy (ECOWAP) started in the early 2000s and involved a wide spectrum of stakeholders ranging from ECOWAS member-states, socioprofessional actors, civil society organizations and development partners. Thus, ECOWAP is a product of broad dialogues that emerged from a thorough review of the sub-region’s agricultural sector, its development potentials, its areas of strength and weakness. The discussions on all of these issues were tailored to deal with the challenges faced by the agricultural sector, with a view to transforming it into an engine of economic growth, and a sustainable means of eradicating poverty and achieving food and nutrition security in the sub-region (ECOWAS Commission Citation2009; Badiane, Odjo, and Wouterse Citation2018). Thus, at the twenty-eighth ordinary session of the conference of the ECOWAS Heads of State and Government held in Accra, Ghana, on 19 January 2005, the decision to adopt the ECOWAP document was taken.

The ECOWAP is integrally linked to the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program (CAADP) of the NEPAD. The CAADP was adopted by the African Union Heads of State and Government (AUHSG) in 2003 in Maputo. The key target of the CAADP is to revitalize the agricultural sector of African states so that it can achieve 6 percent growth in productivity. The major responsibility of African states is to devote at least 10 percent of their annual national budgets to agriculture within 5 years. The CAADP is envisaged to be driven by sub-regional groups through the instrumentality of regional and national agricultural investment plans (RAIP/NAIPs). The ECOWAS facilitated the development of NAIPs among its 15 member-states in the sub-region using a common framework. The essence of evolving a standardized framework was to ensure that issues transcending national borders received adequate attention (NEPAD Citation2003; ECOWAS Commission Citation2009; Staatz, Diallo, and Dembélé Citation2017). Thus, the ECOWAP is not only the sub-regional instrument for the implementation of CAADP in West Africa but also a unified framework to facilitate planning and intervention in the agricultural sector.

The five pillars outlined by CAADP to undergird the actualization of agricultural growth on the continent include the following: (i) land and water management; (ii) improvement in rural infrastructure as well as trade-related capacities in order to access the market; (iii) reduction of hunger through increased food supply; (iv) investment in agricultural research, including dissemination and adoption of technology; and, (v) pursuit of sustainable development of livestock, fisheries and forestry resources (NEPAD Citation2003; ROPPA and ECDPM Citationn.d; Kolavalli et al. Citation2010). Although the CAADP document had only four pillars, however, there was a fifth pillar dealing with the development of livestock, fisheries, and forestry resources, which is sometimes referred to as CAADP 2. This fifth pillar was a product of the ‘recommendation of the AU Heads of State [and Government] during a pre-adoption discussion of the program in Maputo in July 2003’ (Kolavalli et al. Citation2010, 1). The justification for CAADP focusing on these areas was based on the depth of the crisis in the agricultural sector in Africa and the need to prioritize actions that would make earliest difference while making use of existing knowledge, capacity and institutional arrangements (NEPAD Citation2003).

These pillars provided the basis for the vision of the ECOWAP, which was to birth a modern and sustainable agriculture anchored on the private sector (ECOWAS Commission Citation2009). The projection of ECOWAP was that the modernization of the agricultural sector would make it not only productive and competitive but also engender such rewards as food security and better quality of life as a result of commensurate remunerative incomes for the sector’s workers (ECOWAS Commission Citation2009). The various aspects of continental commitments as outlined in the CAADP have been undergoing continuous scrutiny, modifications and reaffirmation. This is demonstrated by numerous declarations and the annual CAADP Partnership Platform that serves as a continental forum for addressing the challenges faced by the agricultural sector in order to keep the goal of consolidating and accelerating its transformation in Africa on track (Kolavalli et al. Citation2010; AU Commission Citation2017; Hendriks Citation2018).

Based on the vision of ECOWAP/CAADP to modernize agriculture for long-term productivity, it developed the broad objective that aimed at making four-pronged contributions, namely, satisfy the food requirements of the population, contribute to socioeconomic development, reduce poverty in the sub-region and deal with inequalities among countries. Seven specific objectives were derived from this broad objective and they dealt with issues ranging from achieving food security and sovereignty by reducing food dependency; integrating producers into markets for enhanced remunerative incomes for agricultural workers; intensifying the production systems; reducing the vulnerability of West African economies to adopting appropriate funding mechanisms. These specific provisions in the ECOWAP/CAADP documents were expected to spawn uniformity in the policy thrusts of the NAIPs produced by member-states.

The operationalization of ECOWAP/CAADP at the regional level targeted six themes, which included (i) management of water; (ii) management of shared natural resources; (iii) development of farms in sustainable ways; (iv) development of markets and supply chains; (v) prevention and management of food crises and other natural disasters; and (vi) institutional strengthening (ECOWAS Commission Citation2009). However, these themes were revised following the adoption of the Regional Initiative for Food Production and the Fight Against Hunger by the Heads of States in June 2008. The necessary consequence of this was the rejigging of intervention priorities leading to the formulation of three mobilizing and federating programs. These programs included the promotion of food sovereignty by developing strategic food value-chains; the promotion of regional agricultural development; the reduction of vulnerability to food crises and the promotion of access to food in a stable and sustainable way (ECOWAS Commission Citation2009).

At the 23rd ordinary meeting of the AU Assembly in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea between 26 and 27 June 2014, a new declaration in the furtherance of continental commitment to agricultural development was adopted and that was how the 2014 Malabo declaration was birthed. The Malabo declaration incorporated the various thrusts of development initiatives being pursued by African leaders. Essentially, the Malabo declaration was a reaffirmation of, and recommitment to, African development. The Malabo declaration has seven areas of commitments, namely, renewed dedication to the principles and values of CAADP, pledge to end hunger and halve poverty in Africa by the year 2025 through the instrumentality of inclusive agricultural growth and transformation. Other commitments include: boosting intra-African trade in agricultural commodities and services, enhancing the resilience of livelihoods and production systems to climate-related risks, and ensuring mutual accountability to actions and results through a systematic regular review process (AU Citation2014). With the Malabo declaration, assessment of sub-regions and countries are now based on their progress in the seven commitments.

3. Brief literature overview

Food plays a central and important role in human existence, as it constitutes one of the basic essentials of life. Thus, providing access to food to citizens is one of the important functions that contemporary governments are expected to guarantee to ensure societal maintenance. It is now generally recognized that freedom from hunger constitutes part of basic rights to which humanity is entitled (Beuchelt and Virchow Citation2012). As a result of this recognition, the global community has been paying great attention to issues of food and nutrition security as exemplified by the prominence given to it in both the MDGs, SDGs and Agenda 2063 (Molteldo et al. Citation2014; AU Citation2015; Pradhan and Rao Citation2018).

Food security as a concept has attracted a lot of scholarly interest and in the course of its dissection, various divergent meanings have been attributed to it (Vance Citation2018). Before food security came into popular usage in the 1990s, the emphasis was on food self-sufficiency (Sasson Citation2012). The multiple divergences in the conceptualization of food security have led some scholars to consider it analytically unhelpful and thus, advocate its replacement with the concept of food sovereignty (Molteldo et al. Citation2014; Vance Citation2018). Food sovereignty emphasizes the right that communities, peoples and states possess to evolve their own policies on food and agricultural practices (Beuchelt and Virchow Citation2012). According to Vance (Citation2018), the value of food sovereignty is its encompassing character and preoccupation with questions of economic and cultural control over food systems. The whole thrust of food security centers on meeting basic criteria of availability, accessibility, utilization and stability irrespective of whether the food is produced locally, imported or provided through humanitarian food aid arrangements (Sasson Citation2012; Gibson Citation2012).

In recent times, the meaning of food security has expanded with emphasis placed on the nutritional aspects of food security by the international community. This emphasis has thrown up such terms as ‘food security and nutrition’ and ‘food and nutrition security’ (FAO Citation2012; Capone et al. Citation2014). Molteldo et al. (Citation2014) have pointed out that the difference in these two concepts is that while food security and nutrition is ‘used to distinguish between actions needed at the global, national, and local levels from actions needed at the household and individual levels’, food and nutrition security underscores nutrition considerations throughout the food chain. Thus, food and nutrition security is now used and it is assumed to exist

when all people at all times have physical, social and economic access to food, which is safe and consumed in sufficient quantity and quality to meet their dietary needs and food preferences, and is supported by an environment of adequate sanitation, health services and care, allowing for a healthy and active life. (FAO Citation2012, 8)

Food insecurity is much more than hunger as it encapsulates various nuances of deprivation. According to FAO et al (Citation2019), the main indicator deployed to monitor progress made with respect to the eradication of hunger in the world is the prevalence of undernourishment (PoU). Within the context of PoU, people could experience moderate or severe food insecurity. Moderate food insecurity encompasses uncertainties about sourcing food, inconsistent access to food, diminution of dietary quality and disruption of established eating patterns. It refers generally to situations, within the year, in which people have inconsistent access to food with the consequence that the quality and/or quantity available to them may not keep up with their nutritional requirements and therefore their overall wellbeing. Severe food insecurity refers to extreme situations where people run out of food, which leads to unavailability of food with the likelihood that they go without food for periods of time. This situation jeopardizes their health and puts their overall well-being in serious danger. FAO et al. (Citation2019) estimate that 26.4 percent of the global population or 2 billion people experience a combination of moderate and severe levels of food insecurity.

The food dependence of many developing countries has increased exponentially. Africa is worst hit considering that it accounts for, at least, one-fourth of the total number of underfed population in the world (Sasson Citation2012). For decades, the agricultural sector in Africa has been witnessing serious downward trend as agricultural production per capita declined and policy interventions proved to be grossly inadequate or inappropriate to reverse the trend (Sasson Citation2012; FAO et al. Citation2019). The African situation is equally reflected in its sub-regions, including West Africa. In order to deal with the situation, African leaders evolved the Comprehensive Africa Agricultural Development Program (CAADP) in 2003 (NEPAD Citation2003). The idea of CAADP is motorized by the centrality of agriculture in the matrix of livelihood in Africa: most of Africa’s population are, more or less, dependent on agriculture for their livelihood. The relevance of the agricultural sector is underscored by its contributions to the economies of African countries as it employs about 60 percent of the population and accounts for some 20 percent of the continent’s gross domestic product (GDP) as well as provides more than 10 percent of the export revenues (Sasson Citation2012). Thus, fostering agricultural growth is central to continental development strategies aimed at reducing poverty and hunger and boosting the quality of life of the people (Brzeska et al. Citation2012).

Essentially, CAADP embodies the continental commitment to reducing poverty, hunger and malnutrition through the instrumentality of agriculture-led growth. Thus, it is envisaged to serve as a framework that coordinates, complements and adds value to national and regional strategies targeted at developing agriculture (Kolavalli et al. Citation2010). One of the major principles of CAADP is the projection of the benchmark of 6 percent annual growth rate in agriculture through the allocation of 10 percent of the national budget to the agricultural sector (NEPAD Citation2003; Brzeska et al. Citation2012).

Despite the overall importance of agriculture to the economies of countries of West Africa, the sub-region suffered the same declining productivity in the agricultural sector, which underpinned the motivation for the launch of ECOWAP by West African leaders. The agricultural sector provides employment and livelihood to 60 percent of the population of the West African sub-region. It also accounts for 16.3 percent of exports and 35 percent of the sub-region’s domestic product (ECOWAS Commission Citation2009; Dupraz and Postolle Citation2013). Notwithstanding the potentials of agriculture, its contributions to the economies of West African countries have been suboptimal. The agricultural sector has not been well-positioned to produce sufficient levels of food resources, both in quantity and quality, to meet national requirements necessary to achieve food security. Thus, most countries in the sub-region rely on food importation to bridge the shortfalls.

The ECOWAP represents a regional strategy to strengthen agriculture bearing in mind its importance in enhancing poverty alleviation and ensuring food security. The ECOWAP initiative recognized that for agriculture to contribute to boosting the sub-region’s economies the hindrances posed ‘by small markets, inefficient transportation and communications infrastructure and lack of irrigation, technical know-how and financial resources' must be resolved (Olayiwola et al. Citation2015, 32). Thus, the major themes of the framework of ECOWAP revolve around three key issues, which include: to increase productivity and competitiveness of agriculture to achieve food security and alleviate poverty; implement trade regimes that would take advantage of the sub-region’s large market and thus allow for economies of scale; and to adapt the trade regime to relations with other regions such that the sub-region would be well positioned in global trade negotiations (Jalloh et al. Citation2013; Olayiwola et al. Citation2015). Under the auspices of ECOWAP/CAADP, a regional action plan with six priorities was drawn for joint implementation by West African countries through their national agricultural investment plans (NAIPs) (Jalloh et al. Citation2013).

In furtherance of the ECOWAP/CAADP regional action plan, Nigeria has formulated a number of programs to reorganize its agricultural sector and place it on the path of productivity. Despite the potentials of agriculture to boost Nigeria’s economy, it has not been sufficiently productive (Hassan et al. Citation2013). While Nigeria had relied on the agricultural sector for its foreign exchange earnings in the immediate post-independence period in the 1960s, the oil boom of the early 1970s led to policy neglect of the agricultural sector, which railroaded the Nigerian economy into being oil-dependent. The neglect of the agricultural sector has had serious consequences on the Nigerian economy ranging from lack of modernization of the sector, dependence on food importation, rise in poverty to food insecurity and malnutrition (Diao et al. Citation2012; Smith Citation2018; Nwozor, Olanrewaju, and Ake Citation2019).

Nigeria has designed a number of strategies to take advantage of its highly favorable agro-ecological conditions and accord agriculture a place in its development agenda. The overall aim is to accelerate agricultural growth with expectations of positive multiplier effect on food security, nutrition, and livelihood expectations. In addition to the National Economic Empowerment Development Strategies (NEEDS) and the National Food Security Program (NFSP), there have been a number of presidential initiatives on crop modifications and improvements with such crops as cassava, cocoa and rice among others receiving utmost attention (Diao et al. Citation2012).

4. Methodology

This study employed both primary and secondary data in assessing Nigeria’s implementation strategies of the priorities contained in the ECOWAP/CAADP. The primary data were generated from key informant interviews (KIIs). The study used two genres of non-probability sampling methods, namely snowball and convenience sampling to determine the key informants. While the snowball sampling technique (identifying initial respondents and drawing on their own networks based on their recommendations to expand the total number of respondents) was used to draw experts from relevant government ministries, convenience-sampling technique (choosing participants based on their easy accessibility, ready availability and convenience) was used to select other interviewees. In total, ten experts were interviewed comprising four officials of the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and six experts chosen from higher institutions of learning. Semi-structured question format was the interview instrument used to elicit responses from the respondents. This provided the respondents the opportunities to elaborate on their answers where necessary.

The secondary data for this study were generated from archival materials ranging from government gazettes relating to agricultural policies, documents from relevant intergovernmental organizations, journal articles, textbooks and relevant web-based materials. The data generated were analyzed using logical induction method.

5. Discussion

Policy Affinity: The Content and Programmatic Concerns of ECOWAP/CAADP and Nigeria’s Agricultural Policies

The aggregated West African sub-regional data have shown improvements in the agricultural sector since the ECOWAP/CAADP was flagged off. Between 2005 when the ECOWAP was midwifed and 2014, data showed significant increases in agricultural productivity. Within this period, several crops such as cereals, maize and rice recorded high productivity. According to FAO (Citation2016), more positive results were recorded in the production of strategic crops such as cereals which achieved productivity increase of about 21 percent, rice paddy production, which increased by about 96 percent and maize production, which rose by about 68 percent. However, there were mixed results for the roots and tubers as well as the livestock and fisheries sub-sectors. Notwithstanding the encouraging aggregated data for the sub-region, important disparities among West African countries in terms of food production were evident (FAO Citation2016).

The ECOWAP/CAADP mandates member-states to design and implement a national policy to boost the productivity and competitiveness of their agricultural sector under the aegis of the National Agricultural Investment Plan (NAIP). Nigeria subscribes to the ECOWAP/CAADP vision of boosting its agricultural sector as it possesses the right combination of resources to achieve more than 6 percent growth in this sector. Out of Nigeria’s total landmass of 92.4 million hectares, about 79 million hectares are arable and only 32 million hectares are under cultivation (FMARD Citation2010). Apart from the desire to diversify its oil-dependent, monocultural economy, there were several other factors that made agriculture an escapable policy choice for the Nigerian government. These included the potential of agriculture to contribute to alleviating the unemployment challenge, and the need to tackle the food insecurity and undernourishment in the face of burgeoning population, deepening poverty profile and unsustainable food import bill (CBN Citation2011).

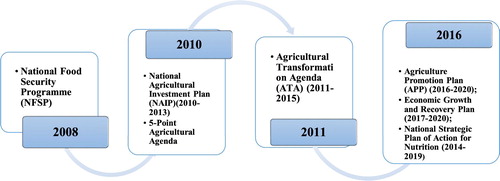

Successive administrations in Nigeria bought into the ECOWAP/CAADP vision and pursued various national programs in which they integrated its core priorities. Thus, Nigeria has developed some strategic plans under the auspices of NAIP, with the latest national agricultural plan designed to span between 2016 and 2020. The administration of Umaru Musa Yar’Adua (2007-2010) had initiated a Seven-Point-Agenda (SPA) to drive national economic growth and development. A critical component of the agenda was food security and agriculture.Footnote2 In other words, the Federal Government made agriculture one of the seven major pillars of its strategic vision to revitalize the national economy for growth and development. Out of the SPA, the focus on agriculture was consolidated into the 5-Point Agriculture Agenda. The challenges faced by the Nigerian economy, especially those of diversification, poverty alleviation and generation of employment opportunities, placed agriculture at the epicenter of any genuine quest for the revitalization of its economy.

The Yar’Adua administration envisioned agriculture to play a critical role in four dimensions, namely, facilitate the attainment of national food and nutrition security; increase agricultural productivity; contribute to employment generation and boost the income of workers in the agricultural sector; and ensure massive reduction in food importation as well as boost the country’s exports profile (FMARD Citation2010; Gadzama Citation2013). Although the SPA did not have a specifically dedicated document to drive its implementation, the global food crisis of 2007–2008 led to the development of the National Food Security Program (NFSP) document in 2008. The NFSP document was essentially developed to address food deficit and insecurity in the country, including the entire agriculture value-chain for crops, livestock and fisheries. The NFSP was a comprehensive and encompassing program as it incorporated and accommodated the thrusts of MDGs on poverty reduction, the CAADP principles and the agriculture and food security focus of the SPA (Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources Citation2008). The National Food Security Program (NFSP), with its broad concern of significantly improving Nigeria’s agricultural productivity, formed the basis for Nigeria’s NAIP.

Technically speaking, the first NAIP by Nigeria in pursuit of ECOWAP/CAADP was developed in 2010 with projections to guide the country’s agricultural development between 2011 and 2014. It addressed the broad spectrum of the agriculture value-chain for crops, livestock (including poultry) and fisheries (FMARD Citation2010). Its key emphases were anchored on five core components consisting of: enhancement of agricultural productivity; support to commercial agriculture; land and water control; linkages and support to inputs and products markets; and program coordination, monitoring and evaluation. In order to achieve the goals of NAIP, two strategies were recognized, namely the medium-term sector strategy (MTSS) comprising all projects that would be initiated, funded and executed by the representatives of the Nigerian government; and, the partnership programs, which comprised projects fully or partly financed by donor agencies and executed by them fully or jointly with the government and the private sector. The overall agricultural development targets were listed to include: reducing poverty level by 50 percent from its 2006 level by 2015; reducing the proportion of under-nourished people by 50 percent from its 2006 level by 2015 and achieving real agricultural GDP growth rate of at least 8 percent per annum (FMARD Citation2010).

NAIP and its expected outcomes were superseded by the Agricultural Transformation Agenda (ATA) as the key program for the agricultural sector. The implementation of ATA at both the national and state levels replaced the NAIP as the medium term plan of the government for the period, 2011–2015 and attempts to merge the NAIP and the ATA were unsuccessful. What really transpired that led to these policy changes was the death of Umaru Yar’Adua. It was through his SPA that the 5-Point Agriculture Agenda came into existence and contributed to the formulation of NAIP. He was still the president when all the formalities for NAIP were completed and at his demise on 5 May 2010, his deputy then, Goodluck Jonathan completed his tenure, which expired in 2011. While completing the tenure of Yar’Adua, Jonathan felt obligated to continue with his policies. However, that was to change in 2011, when Jonathan secured a mandate through the ballot box to be president. Thus, the new mandate brought changes, including new policy trajectories in the agricultural sector. Jonathan floated a new agricultural policy, the ATA, which replaced NAIP. Our respondents argued that what principally motivated the change was the quest of the Jonathan administration to appear original and take all accolades that might accompany a successful implementation of the policy.

The Agricultural Transformation Agenda was launched in 2011 as the flagship of Nigeria’s efforts at restoring the agricultural sector to the driver’s seat in the country’s economy. The ATA was envisioned to provide the needed platform to realize food and nutrition security as well as generate employment and transform Nigeria into a major food producer in global context (FMARD Citation2011). The ATA was a departure from the way in which previous policy instruments conceptualized government intervention in the agricultural sector. It conceived agriculture as a business and not a development project and as such the primary role of the government would be to create an enabling environment for the private sector leadership in providing all the necessary inputs and services (FMARD Citation2011; ROPPA/ECDPM Citationn.d.). As a result of this change in orientation, the ATA undertook the restructuring of the protocol for fertilizer procurement and distribution, marketing institutions, financial value-chains and agricultural investment framework through six major institutional frameworks (FMARD Citation2011). below displays the six major operational components of ATA. These components targeted various aspects of the agricultural sector and had key deliverables and projected outcomes.

Table 1. Major operational components of ATA.

The ATA represented a change in approach in the agricultural sector. This change in approach focused on the adoption of a commodity value-chain approach, policy and institutional reforms, opening the door wider for private sector participation and plugging inefficiency and wastages in public expenditure to enhance competiveness and productivity. The key sectoral focus included: revamping the fertilizer procurement and distribution model, improving the operations of marketing institutions, enhancing the financial value-chains and reorganizing the agricultural investment framework. Beyond the key expectations of attaining food security, diversifying the economy, creating more jobs, and generating foreign exchange from this interventionist agenda, positive multiplier expectations included the transition of farmers from subsistence to commercial levels through the financing of agricultural value-chain, fostering rural infrastructure improvement and economic growth, and enhancing farmer access to markets, technologies, extension services, and finance through an investor-friendly framework for agricultural investment (FMARD Citation2011; CBN Citation2011).

The ATA was administered and driven by a plethora of bodies under the aegis of the Agricultural Transformation Implementation Council (ATIC). These groups included the Agricultural Industry Advisory Group (AIAG), which represented the voice of the private sector; the Agricultural Investment Transformation Implementation Group (AITEG) saddled with the task of creating the right settings to grow private and public sector investment along strategic value-chains; the Agricultural Value-Chain Transformation Implementation Group (AVCTEG) charged with the primary function of increasing agricultural productivity and links to the markets; the NIRSAL Implementation Group (NIRSALEG) with responsibility to execute partnership between Nigeria’s Central Bank and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD) to unlock US$3 billion in agricultural financing; and the Agricultural Transformation Policy Group (ATPG) whose role was to determine and institutionalize policy support to the Agenda.

These implementation groups complemented each other in the overall policy expectations of employing a commodity value-chain approach to achieve food security, create employment, respond to the raw-material needs of agro-allied industries, encourage value addition, evolve efficient storage systems for agricultural produce and develop effective marketing outlets. The ATA designated five crops, namely, cassava, rice, sorghum, cotton and cocoa as priority agricultural commodities and encouraged the six geopolitical zones to focus on their production. Several policy initiatives were flagged off to realize the various aspects of these key programs. below shows the key programs of action enunciated by the Nigerian government to actualize the objectives of ECOWAP/CAADP.

Figure 1. Key operational programs for the realization of the agricultural agenda of ECOWAP/CAADP (Source: Adapted by the author from various documents).

The Agriculture Promotion Policy (APP) (also referred to as the Green Alternative) was designed and launched in August 2016 and is currently the policy framework driving agricultural development in Nigeria. The NAIP 2 to drive this policy is still in the works, although the draft version was released in 2017 for further input from stakeholders (Hendriks Citation2018). The policy thrusts of APP revolve around four key themes, namely, food security, import substitution, job creation, and economic diversification. It is more or less the continuation of ATA in a new name, as the APP did not break away from its predecessor’s overarching goals. The APP document explicitly acknowledged that it is a product of the successes and lessons learnt in the course of implementing the ATA. Thus, the APP’s core mission is to build an agribusiness economy with focus on meeting domestic food security goals of the country and delivering sustained prosperity to workers and investors in agricultural sector (FMARD Citation2016). In order to achieve this mission, the APP recognized the ubiquity of constraints and therefore identified interventionist strategies and targeted outcomes. summarizes these thematic areas of intervention and targets. The projection is that dealing with these constraints would contribute to the overhauling of the agricultural sector for greater efficiency and productivity.

Table 2. Organizing themes for APP to deal with constraints in the agricultural sector.

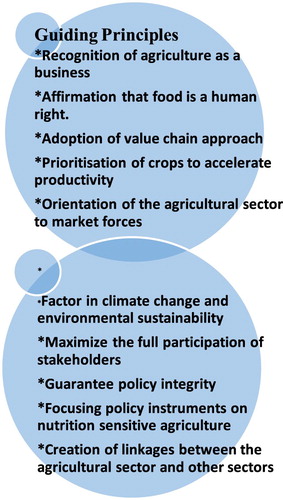

The APP expanded the guiding principles in ATA to demonstrate policy continuity and stabilization and to reflect emerging priorities in the development of Nigeria’s agricultural sector. These guiding principles are anchored on, and reflect, the shift in policy perception. captures the 11 guiding principles of APP.

(ii) Targeting Food Security: Assessing Nigeria’s Agricultural Policy Outcomes in the Matrix of Sub-Regional Benchmarks

Figure 2. The guiding principles of APP (Source: Adapted from FMARD Citation2016).

The major impetus underpinning the adoption of ECOWAP by West African leaders as the flagship of the sub-region’s efforts at poverty reduction is the centrality of agriculture in its basket of foreign exchange earnings and its strong prospects as a major vehicle for regional market integration (ECOWAS Commission Citation2009). The agricultural sector is indispensable to the economies of West African countries despite its underdevelopment. Under the auspices of ECOWAP/CAADP, the ECOWAS Commission has overseen and coordinated the preparation of NAIPs by its member-states by providing needed support and fostering national roundtable dialogues among actors in each country.

The NAIPs encompass the national visions, aspirations and priorities of states in the furtherance of their agricultural agenda in line with ECOWAP/CAADP. Thus, they represent the referential framework for programming activities in the agricultural sector as well as for mobilizing and coordinating international assistance and partnerships. Nigeria has been in the forefront of mainstreaming its agricultural sector to retake its erstwhile position in the matrix of its foreign exchange earnings since it formulated NEEDS (Smith Citation2018). Since then, Nigeria has been upbeat in its quest to restructure and modernize its agricultural sector within the context of ECOWAP/CAADP. There have been significant policy interventions and reforms in Nigeria’s agricultural sector since the adoption of ECOWAP/CAADP. These interventions include the 5-point agriculture agenda, ATA, numerous presidential initiatives, many international partnerships and the current APP.

Nigeria has recorded a mixed bag of achievements in its quest to build a more productive, efficient, and effective agricultural sector capable of reducing capital flight from food importation as well as generating foreign exchange earnings. Under the auspices of government’s policy interventions, several successes have been recorded in some aspects of institutional processes in the sector. The hitherto inefficient federal fertilizer procurement system was restructured. The restructuring made it possible for the development of database on smallholder farmers through the Growth Enhancement Scheme (GES). This facilitated the provision and smooth disbursement of targeted input subsidies. While only 11 percent of subsidized fertilizer reached the intended farmers under the old regime, the new reform involving the use of vouchers led to about 94 percent of actual farmers receiving the subsidized fertilizer (Adesina Citation2012). There were also other achievements like the concession of federal warehouses and storage assets, the reestablishment of commodity marketing boards for select commodities and the reform of the Agricultural Research Coordination Network (ARCN) (ROPPA and ECDPM Citationn.d; Adesina Citation2012). Although policy prescriptions appear to be in place, there are several areas that Nigeria performed well and many others where more work still needs to be done. below shows Nigeria’s key areas of strong and weak performances. In the areas of strong performance, there is no policy issue that recorded up to 70 percent, which is an indicator that more efforts still need to be expended in transforming the agricultural sector. The low public expenditure profile and the mix of negative trends in annual growth of agriculture and value-added to arable land generally resulted in low productivity with serious implications for price stability. Interestingly, even with these negative trends, domestic food price volatility was just 5 percent. Our respondents contended that the shortfall that would have pushed up prices were contained through food importation.

Table 3. Key areas of strong and weak performances of the country.

The overall picture from key indicators such as agricultural productivity, poverty, hunger, and malnutrition, does not seem to suggest that there is a strong improvement yet. According to NEPAD sources, Nigeria is not on track in terms of meeting the benchmarks stipulated in the Malabo Declaration on agricultural transformation in Africa. The country’s overall score is 3.4 on a 10-point scale. The cornerstone of Nigeria’s poor performance is the low percentage of its national budget allocated to agriculture. Notwithstanding that ECOWAP/CAADP recommended the deployment of a minimum of 10 percent of national budgetary allocation to the agricultural sector, Nigeria only allocates a mere 2.2 percent to agriculture, which is a far cry from the minimum public expenditure benchmark. presents Nigeria’s performance based on the Malabo Declaration. Out of the seven areas of commitment in the Declaration, Nigeria is on track in two areas, namely commitment to CAADP processes and boosting intra-African trade in agricultural commodities. The country is off-track in five areas of commitment that are critically important to boosting agricultural productivity and competitiveness.

Table 4. Nigeria’s 2017 scorecard based on the implementation of Malabo Declaration.

The overall poor performance of Nigeria in meeting the national, sub-regional and continental aspirations in the agricultural sector is not strange considering the low public expenditure committed to the sector. The agricultural sector is underperforming and, therefore, requires massive inflow of investment. The underinvestment in the sector has also sustained the culture of food importation as Nigeria continues to spend billions of dollars on food importation every year with attendant huge economic opportunities for food security and improved remunerative package by agricultural workers lost (Adesina Citation2012; Vanguard Citation2017). Recently, the Nigerian government partially closed its border with Benin Republic to check massive smuggling of commodities, especially rice (Ameh Citation2019). The concern of the government was that large-scale smuggling of commodities, especially rice, was going on through the border and would reverse the gains recorded in the rice sector. Interestingly, the border closure induced a spiraling inflation in the Nigerian economy with a sharp spike in the prices of food items, especially rice, which skyrocketed to N30,000 per bag of 50 kilograms, making it unaffordable to millions of Nigerians (Nwozor and Oshewolo Citation2020). The critical issue thrown up by the border closure is that Nigeria is still far from food self-sufficiency. The large-scale smuggling in commodities is a necessary fallout of underinvestment in the agricultural sector, which has created a huge demand gap yearning to be filled.

6. Conclusion

As part of the quest for continental development, African leaders initiated CAADP in 2003 to revitalize and leverage the agricultural sector to drive development on the continent. The leadership of ECOWAS towed the same line in 2005 through ECOWAP. Nigeria has formulated several agricultural policies in line with the overall objectives of ECOWAP/CAADP to reposition its agricultural sector.

The emphasis of the Nigerian government on agriculture is more like an agricultural renaissance. Before the Nigerian economy became overly dependent on oil, agriculture was the major source of foreign exchange earnings. Nigeria was reasonably self-sufficient in food production and quite prominent as a major producer of a number of commodities including groundnuts, palm oil, cocoa and cotton (Smith Citation2018). Everything about agriculture changed when it went into neglect as a result of the discovery and ascendancy of oil. Despite the dominance of oil in the Nigerian economy, agriculture is recognized as the key solution to food and nutrition insecurity, mass unemployment and poverty. The updated version of CAADP, known as Malabo Declaration identified seven deliverable commitments that would serve as parameters for evaluating whether countries are on track or not.

Although Nigeria has been implementing ECOWAP/CAADP through its ATA and now APP programs, the scorecard shows that more still needs to be done. Out of the seven commitments contained in the 2014 Malabo Declaration, Nigeria is only on track in two areas. The country is underinvesting in the agricultural sector and it is having negative multiplier effects. Modest success recorded a few years back, which led to a reduction in the country’s food import bill is under risk of reversal. Nigeria’s monthly food import bill fell from US$665.4 million in January 2015 to US$160.4 million as at October 2018, representing a cumulative fall of 75.9 percent and a saving of US$21 billion for the period (Popoola Citation2018).

The underinvestment in agriculture has opened the door to importation to bridge the gap in food availability due to decline in productivity. Recently, the Nigerian government took two interrelated actions to checkmate food importation: it directed the Nigerian Central Bank to stop processing foreign exchange for food imports, and it closed down its border with Benin Republic (Ameh Citation2019; Onuah Citation2019). These measures are mere palliatives that lack long-term capacity to effectively check smuggling. As long as there is gap in food production and as long as inefficient production creates profit margins for smugglers, food importation and smuggling will persist (Nwozor and Oshewolo Citation2020). Thus, the panacea is for Nigeria to return on ECOWAP/CAADP track by setting up a roadmap for increased investment in the agricultural sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is an economic union domiciled in the West African sub-region with 15 member-states namely: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape-Verde, Cote d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo.

2 In addition to food security and agriculture, the Seven-Point-Agenda covers: power and energy, wealth creation and employment, mass transportation, land reform, security, and qualitative and functional education.

References

- Abu, O. 2012. “Food Security in Nigeria and South Africa: Policies and Challenges.” Journal of Human Ecology 38 (1): 31–35. doi:10.1080/09709274.2012.11906471.

- Adesina, A. 2012. “Agricultural Transformation Agenda: Repositioning Agriculture to Drive Nigeria’s Economy.” https://queenscompany.weebly.com/uploads/3/8/2/5/38251671/agric_nigeria.pdf.

- Ameh, J. 2019. “Nigeria-Benin Border Closed to Stop Smuggling – Buhari.” Punch, August 28. https://punchng.com/nigeria-benin-border-closed-to-stop-smuggling-buhari/.

- AU (African Union). 2014. “Malabo Declaration on Accelerated Agricultural Growth and Transformation for Shared Prosperity and Improved Livelihoods.” https://www.resakss.org/sites/default/files/Malabo%20Declaration%20on%20Agriculture_2014_11%2026-.pdf.

- AU (African Union). 2015. “Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want First Ten-Year Implementation Plan 2014–2023.” https://www.un.org/en/africa/osaa/pdf/au/agenda2063-first10yearimplementation.pdf.

- AU Commission. 2017. “The 13th CAADP Partnership Platform on ‘Strengthening Mutual Accountability to Achieve CAADP/Malabo Goals and Targets’: Delegates’ Brief.” https://www.nepad.org/file-download/download/public/15736.

- Badiane, O., S. P. Odjo, and F. Wouterse. 2018. “Macro-Economic Models: Comparative Analysis of Strategies and Long Term Outlook for Growth and Poverty Reduction among ECOWAS Member Countries.” In Development Policies and Policy Processes in Africa: Modeling and Evaluation, edited by C. Henning, O. Badiane, and E. Krampe, 21–48. Cham: Springer Nature.

- Beuchelt, T. D., and D. Virchow. 2012. “Food Sovereignty or the Human Right to Adequate Food: Which Concept Serves Better as International Development Policy for Global Hunger and Poverty Reduction?” Agriculture and Human Values 29 (2): 259–273. doi:10.1007/s10460-012-9355-0.

- Bini, V. 2016. “Food Security and Food Sovereignty in West Africa.” African Geographical Review 37 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/19376812.2016.1140586.

- Brzeska, J., X. Diao, S. Fan, and J. Thurlow. 2012. “African Agriculture and Development.” In Strategies and Priorities for African Agriculture: Economywide Perspectives From Country Studies, edited by X. Diao, J. Thurlow, S. Benin, and S. Fan, 1–16. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Capone, R., H. El Bilali, P. Debs, G. Cardone, and N. Driouech. 2014. “Food System Sustainability and Food Security: Connecting the Dots.” Journal of Food Security 2 (1): 13–22. doi:10.12691/jfs-2-1-2.

- CBN (Central Bank of Nigeria). 2011. Central Bank of Nigeria Annual Report. Abuja: CBN.

- Crola, J. 2015. “ECOWAP: A Fragmented Policy.” Oxfam Briefing Paper. https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/bp-ecowap-fragmented-policy-131115-en.pdf.

- Diao, X., M. Nwafor, V. Alppuerto, K. T. Akramov, V. Rhoe, and S. Salau. 2012. “Nigeria.” In Strategies and Priorities for African Agriculture: Economywide Perspectives From Country Studies, edited by X. Diao, J. Thurlow, S. Benin, and S. Fan, 211–244. Washington, DC: International Food policy Research institute.

- Dupraz, C. L., and A. Postolle. 2013. “Food Sovereignty and Agricultural Trade Policy Commitments: How Much Leeway Do West African Nations Have?” Food Policy 38: 115–125. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.11.005.

- ECOWAS Commission. 2009. “Regional Partnership Compact for the Implementation of ECOWAP/CAADP”. http://www.oecd.org/swac/publications/44426979.pdf.

- ECOWAS Commission. 2010. Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Revised Treaty. Abuja: ECOWAS Commission. https://www.ecowas.int/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Revised-treaty.pdf.

- ECOWAS Commission. n.d. “Regional Agricultural Policy for West Africa: ECOWAP.” https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/01_ANG-ComCEDEAO.pdf.

- FAO. 2016. “Has Ten-Year Implementation of the Regional Agriculture Policy of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAP) Contributed to Improve Nutrition?” http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5859e.pdf.

- FAO and ECA (Economic Commission for Africa). 2018. Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition: Addressing the Threat From Climate Variability and Extremes for Food Security and Nutrition. Accra: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 2012. “Committee on World Food Security: Coming to Terms with Terminology.” Thirty-ninth session, Rome, Italy, 15–20 October. http://www.fao.org/3/MD776E/MD776E.pdf.

- FAO, IFAD (International Fund for Agricultural Development), UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund), WFP (World Food Programme) and WHO (World Health Organization). 2019. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019: Safeguarding Against Economic Slowdowns and Downturns. Rome: FAO.

- Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources. 2008. “National Food Security Programme.” http://www.inter-reseaux.org/IMG/pdf_Food_security_Document-Nigeria.pdf.

- FMARD (Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development). 2010. “ECOWAP/CAADP Process: National Agricultural Investment Plan (NAIP) 2010–2013.” http://www.inter-reseaux.org/IMG/pdf_NATIONAL_AGRIC-_INVEST-_PLAN_FINAL_AUG17.pdf.

- FMARD (Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development). 2011. “Agricultural Transformation Agenda: We Will Grow Nigeria’s Agricultural Sector.” http://unaab.edu.ng/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Agricultural%20Transformation%20Blue%20Print.pdf.

- FMARD (Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development). 2016. “The Agriculture Promotion Policy (2016–2020): Building on the Successes of the ATA, Closing Key Gaps.” https://fscluster.org/sites/default/files/documents/2016-nigeria-agric-sector-policy-roadmap_june-15-2016_final1.pdf.

- Gadzama, I. U. 2013. “Effects of President Umaru Musa Yar’adua’s 7-Point Agenda on Agricultural Development and Food Security in Nigeria.” European Scientific Journal 9 (32): 448–462.

- Gibson, M. 2012. “Food Security-A Commentary: What is it and Why is it so Complicated?” Foods 1 (1): 18–27. doi:10.3390/foods1010018.

- Hassan, S. M., C. E. Ikuenobe, A. Jalloh, G. C. Nelson, and T. S. Thomas. 2013. “Nigeria.” In West African Agriculture and Climate Change: A Comprehensive Analysis, edited by A. Jalloh, G. C. Nelson, T. S. Thomas, R. Zougmoré, and H. Roy-Macauley, 259–290. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Hendriks, S. L. 2018. “A Review of the Draft Federal Government of Nigeria’s National Agriculture Investment Plan (NAIP2).” Policy Research Brief 59. https://www.canr.msu.edu/fsp/publications/policy-research-briefs/policy_brief_59.pdf.

- Jalloh, A., M. D. Faye, H. Roy-Macauley, P. Sereme, R. Zougmore, T. S. Thomas, and G. C. Nelson. 2013. “Overview.” In West African Agriculture and Climate Change: A Comprehensive Analysis, edited by A. Jalloh, G. C. Nelson, T. S. Thomas, R. Zougmoré, and H. Roy-Macauley, 1–36. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Kolavalli, S., K. Flaherty, R. Al-Hassan, and K. O. Baah. 2010. “Do Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program (CAADP) Processes Make A Difference to Country Commitments to Develop Agriculture? The Case of Ghana.” IFPRI Discussion Paper 01006. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.226.2918&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Mbow, C., M. Van Noordwijk, E. Luedeling, H. Neufeldt, P. A. Minang, and G. Kowero. 2014. “Agroforestry Solutions to Address Food Security and Climate Change Challenges in Africa.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 6: 61–67. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2013.10.014.

- Molteldo, A., N. Troubat, M. Lokshin, and Z. Sajaia. 2014. Analyzing Food Security Using Household Survey Data: Streamlined Analysis with ADePT Software. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648-0133-4

- NEPAD (New Partnership for Africa’s Development). 2003. Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP). Midrand: New Partnership for Africa’s Development. https://www.nepad.org/file-download/download/public/15057.

- Nwozor, A., J. S. Olanrewaju, and M. B. Ake. 2019. “National Insecurity and the Challenges of Food Security in Nigeria.” Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 8 (4): 9–20. doi:10.36941/ajis-2019-0032.

- Nwozor, A., and S. Oshewolo. 2020. “Nigeria’s Border Closure Drama: The Critical Questions.” The Round Table 109 (1): 90–91. doi:10.1080/00358533.2020.1715106.

- Olayiwola, W., E. Osabuohien, H. Okodua, and O. Ola-David. 2015. “Economic Integration, Trade Facilitation Agricultural Exports Performance in ECOWAS Sub-Region.” In Regional Integration and Trade in Africa, edited by M. Ncube, I. Faye, and A. Verdier-Chouchane, 31–46. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Onuah, F. 2019. “Nigeria Closes Part of Border with Benin to Check Rice Smuggling.” Reuters, August 29. https://af.reuters.com/article/topNews/idAFKCN1VJ0PH-OZATP.

- Popoola, N. 2018. “Nigeria Cut Food Imports, Saved $21bn in 34 Months – Emefiele.” Punch, December 3. https://punchng.com/nigeria-cut-food-imports-saved-21bn-in-34-months-emefiele/.

- Pradhan, M., and N. Rao. 2018. “Gender Justice and Food Security: The Case of Public Distribution System in India.” Progress in Development Studies 18 (4): 252–266. doi:10.1177/1464993418786795.

- ROPPA/ECDPM. n.d. “Ten Years after Maputo Declaration on Agriculture and Food Security: An Assessment of Progress in Nigeria.” https://www.roppa-afrique.org/IMG/pdf/nigeria_maputo_study_draft_final_report__kf.pdf.

- Sasson, A. 2012. “Food Security for Africa: An Urgent Global Challenge.” Agriculture & Food Security 1 (2): 1–16. doi:10.1186/2048-7010-1-2.

- Simson, R., and V. T. Tang. 2016. “Food Security in ECOWAS.” In Comparative Regionalisms for Development in the 21st Century: Insights From the Global South, edited by E. Fanta, T. M. Shaw, and V. T. Tang, 159–177. New York: Routledge.

- Smith, I. 2018. “Promoting Commercial Agriculture in Nigeria Through a Reform of the Legal and Institutional Frameworks.” African Journal of International and Comparative Law 26 (1): 64–83. doi:10.3366/ajicl.2018.0220.

- Staatz, J. M., B. Diallo, and N. Dembélé. 2017. “Policy Responses to West Africa’s Agricultural Development Challenges.” In Strengthening Regional Agricultural Integration in West Africa: Key Findings and Policy Implications, edited by J. M. Staatz, B. Diallo, and N. M. Me-Nsope, 223–239. Basel: Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture. https://www.syngentafoundation.org/sites/g/files/zhg576/f/strength_reg_ag_integ_w_africa_key_findings_policy_implic.pdf#page=263.

- Vance, C. 2018. “‘Food Security’ Versus Cash Transfers: Comparative Analysis of Social Security Approaches in India and Brazil.” Journal of Human Security 14 (1): 5–10. doi:10.12924/johs2018.14010005.

- Vanguard. 2017. “In Nigeria’s Steady Progress in Agriculture, Potential History in the Making.” https://www.vanguardngr.com/2017/03/nigerias-steady-progress-agriculture-potential-history-making/.

- Zoungrana, D. T. 2013. “Who is More Protective of Food Security: The WAEMU or ECOWAS?” Bridges Africa, 2(2). http://www.ictsd.org/bridges-news/bridges-africa/news/who-is-more-protective-of-food-security-the-waemu-or-ecowas.