?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Existing literature argues that political competition and electoral participation influence government efficiency. However, empirical evidence on the matter for developing countries is scant and mixed. This paper contributes to the literature by exploring the impact of political competition and electoral participation on the fiscal performance of 1,098 Colombian municipalities during four government periods (2000-2015). Using a fixed effect panel data model, we find a significant positive relationship between political competition and electoral participation and a composite fiscal performance index. To be more precise, our results indicate that municipalities that have a lower concentration of council seats in the hands of few parties (i.e. a lower Herfindahl-Hirschman Index) and higher voter turnout rates tend to perform better. These results are explained by the positive impact of political competition and electoral participation on operating expenses, local revenue generation, investment and savings. Overall, these findings support political accountability theories, which argue that electoral participation and political competition incentivize career-concerned politicians to perform well and to reduce rent-extraction behavior.

1. Introduction

Standard economic theory argues that competitive markets allocate resources more efficiently than markets in which agents have some form of market power. Similar arguments are frequently proposed in the public choice literature, which assumes that political competition and electoral participation enhance the accountability of politicians and thus discourage rent-extraction behaviorFootnote1, enhance government efficiency and increase the provision of public goods (Stigler Citation1972; Barro Citation1973).

The main channel through which political competition and electoral participation is expected to influence accountability positively is oversight coupled with career concerns. Politicians have an incentive to get re-elected, given that a political career provides income and status benefits. When competition and electoral participation are high, and politicians do not show sufficient abilities in office, they face the credible threat that their constituents do not re-elect them. Accordingly, they have an incentive to behave in a way that convinces citizens that they are ‘apt for office’. Contrarily, when competition is lacking it is more likely that politicians will serve their self-interests and engage in rent extraction, which in turn has negative effects on fiscal performance (Ferejohn Citation1986; Lake and Baum Citation2001; Besley and Preston Citation2002).

The weak government hypothesis, on the other hand, argues that political competition can have negative effects on fiscal performance. This is because governments that are comprised of many political parties are less likely to carry out necessary fiscal reforms, because coalition partners often have the power to prevent changes (i.e. they have a veto power) but not the power to actively implement them. Single-party majorities, on the contrary, are expected to be able to reduce spending or increase taxes when necessary, and thus to achieve better fiscal performances (Roubini and Sachs Citation1989; Perotti and Kontopoulos Citation2002). Moreover, fragmented governments might not be able to prevent powerful interest groups extracting fiscal resources (Tornell and Lane Citation1999), or each coalition partner tries to please their electorate with the supply of public goods (Ashworth Citation2005).

All of these theories apply to both the policies of the executive branch and the willingness and ability of the legislative branch to comply with their oversight function (Persson, Roland, and Tabellini Citation1997). On the local level, for example, typically all laws and budgets need to be accepted by the council, and there is a general tendency of increasing council responsibilities and public participation in councils (Lowndes, Pratchett, and Stoker Citation2001). It can be expected that political competition and pressure from the electorate influence the likeliness of the council representing the interests of the citizens and controlling and questioning the actions of the executive branch, which in turn influence the fiscal performance of the municipality positively or negatively.

To verify empirically how electoral participation and political competition affect fiscal performance, papers increasingly perform single-country case studies with sub-national data, which has the advantage that the institutional context is homogenous, i.e. electoral rules, timing of elections and budget rules are identical for all units of observation (Ashworth Citation2005). However, these studies provide mixed evidence. Some results reveal a positive impact of voter turnout and political competition on local fiscal performance (e.g. Besley and Preston Citation2002; Ashworth et al. Citation2014; Chamon et al. Citation2019), some studies do not find a robust statistically significant relationship (e.g. Rattso and Tovmo Citation2002; Rodriguez Bolivar et al. Citation2018; Suzuki and Han Citation2019) and others discover a negative impact (e.g. Borge Citation2005; Hagen and Vabo Citation2005). A further limitation of this literature is that it tends to concentrate on developed countries, with the noteworthy exception of various case studies about Brazil.

This brief summary of the theoretical and empirical literature shows the complexity of the relationship between fiscal performance and political competition and electoral participation, as well as the need for further research to broaden our understanding of this important matter. This is especially true for developing countries for which little empirical evidence exists and for which the need to employ their scarce resources more efficiently is a pressing issue. This paper contributes to the literature by exploring the impact of electoral participation and political competition in local councils on the fiscal performance with a rich panel dataset of 1,098 Colombian municipalities over four government periods (2000-2015).

The obtained fixed effect regression results indicate that municipalities that have a lower concentration of council seats in the hands of few parties (i.e. a lower Herfindahl-Hirschman Index) and higher electoral participation rates tend to have a better fiscal performance. This result is explained by the positive impact of political competition and electoral performance on operating expenses, revenue generation, investment and savings. These findings support the aforementioned political accountability theories that argue that electoral participation and political competition incentivize career-concerned politicians to perform well and to reduce rent-extraction behavior.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 gives an overview of the existing empirical evidence on the impact of political competition and electoral participation on fiscal performance; Section 3 describes the institutional setting in Colombia; Section 4 presents the methodology and data used to estimate the impact of political concentration on the fiscal performance in Colombian municipalities; Section 5 discusses the obtained regression results; Section 6 draws conclusions from the main findings.

2. Existing empirical evidence

A wide array of studies have tried to verify the impact of political competition and electoral participation on fiscal performance. While most of these studies agree that voter turnout is a suitable proxy for electoral participation, less consensus has been reached with regard to political competition. Most studies use variables that consider the electoral outcome, like the number of parties that form the government (Roubini and Sachs Citation1989; Schaltegger and Feld Citation2009), the excess number of seats above the amount that is necessary for majority (Volkerink and de Haan Citation2001), the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index of seat concentration (Rattso and Tovmo Citation2002; Hagen and Vabo Citation2005; Borge, Falch, and Tovmo Citation2008), the percentage of votes that a governor/party receives (Remmer and Wibbels Citation2000; Gosh Citation2010), the margin of victory (Cleary Citation2007; Boulding and Brown Citation2014), the volatility of vote shares over time (Ashworth et al. Citation2014), or the alternation of parties in office (Rumi Citation2009).

However, some studies also use variables that consider competition during the election process, like the number of parties contesting the election (Ashworth et al. Citation2014) or the number of effective candidates (Arvate Citation2013; Chamon et al. Citation2019). More unusual proxies employed are composite indices (Holbrook and van Dunk, Citation1993), the Polity IV index (Aidt and Eterovic Citation2011) –which is designed to measure democratic vs. autocratic country regimes– and the probability that two randomly picked parliamentary representatives will be of the same party (Yogo and Ngo Njib Citation2018). This ambiguity in the use of political competition proxies in part can be explained by the specific theoretical framework that each study considers but is also due by the fact that the literature tends to mix different concepts of competition (Bartolini Citation1999).

Nevertheless, the empirical literature can be grouped into studies that focus on the national, state or municipal level. Most studies that consider national governments present evidence suggesting that governments comprised of large coalitions tend to have higher budget deficits. For example, Roubini and Sachs (Citation1989) show that between 1960 and 1985 minority governments in 14 OECD countries had significantly higher deficits than majority governments. This finding is mainly explained by larger deficits during the economic slowdown after 1974. They interpret these results as evidence that multiple coalition governments are too weak to implement necessary structural reforms (due to the veto power of the coalition members).

De Haan, Sturm, and Beekhuis (Citation1999) and Volkerink and de Haan (Citation2001) present similar findings. They show that OECD countries with larger coalitions had higher deficits in OECD countries during the 1970s to 1990s. According to the results of Perotti and Kontopoulos (Citation2002) the negative impact of large coalitions on OECD country budget deficits is explained by higher transfer payments. In terms of single country studies, Galli and Padovano (Citation2002) find that the fragmentation of the Italian government partly explains the federal budget deficits that the country had between 1950 and 1998. However, not all national tier studies find significant effects. De Haan and Sturm (Citation1997), for example, do not find any evidence that OECD countries’ debt growth and spending are influenced by the number of governing parties.

In the case of developing countries, Aidt and Eterovic (Citation2011) study the impact of electoral participation on government size for an unbalanced panel of 18 Latin American countries during the period 1920-2000. They find that in these countries an increase in political competition decreases both tax revenue and government expenditure, while an increase in electoral participation has the opposite effect. Yogo and Ngo Njib (Citation2018) come to the opposite conclusions. To be more precise, their results suggest that political competition increased the tax revenue of developing countries during the period 1988-2010.

Next to the effects on national fiscal performance, many studies verify the impact of polticial competition at the state level at certain times. For example, Holbrook and van Dunk (1993) construct an electoral competition indicator for US states. Their results indicate that between 1982 and 1986 states with higher electoral competition provided more public goods, from which they conclude that higher competition leads to more accountability. Using the same indicator, Barrilleaux, Holbrook, and Langer (Citation2002) find that between 1971 and 1990 Democrat controlled state legislatures engaged in more welfare spending when electoral competition was relatively high, while the latter had no impact on Republican welfare spending. However, with regard to government fragmentation, Schaltegger and Feld (Citation2009) and Baskaran (Citation2013) do not find robust evidence that the size of coalitions affects state level government spending in Germany and Switzerland, respectively. Schaltegger and Torgler (Citation2007), on the other hand, provide evidence that Swiss cantons with a higher direct participation of voters showed a higher fiscal discipline (i.e. lower indebtedness) between 1981 and 2001.

With regard to evidence in developing countries, Remmer and Wibbels (Citation2000) study the impact of political competition on the fiscal performance of 23 Argentinean provinces for the year 1995. They find that provinces with governors that were voted with a large majority have higher public wage expenditure and thus an inferior fiscal performance (measured as fiscal balance and per capita debt). Using panel data for the period 1984–1999 and a different measure of political competition, Rumi (Citation2009) presents contrary results. She finds that Argentinean provinces with a high alternation of the party that is in power (i.e. with high competition) had larger fiscal deficits.

In line with the latter finding, Gosh’s (Citation2010) results suggest that higher competition increased the economic expenditure of 14 Indian states between 1980 and 2004. To be more precise, a lower concentration of assembly seats or election votes led to more expenditure and higher deficits (given that tax revenues were not positively influenced by competition). Similarly, Datta (Citation2020) finds that during the period 1991–2011 the public healthcare expenditure of 16 Indian states depended positively on the amount of political competition.

Increasingly, studies use even more disaggregated national data by looking at the impact of political competition on local councils or mayoral elections. For example, Besley and Preston (Citation2002) use data of 364 English District Councils for the year 1995, and find that a greater vote/seat bias in favor of one party is associated with higher levels of public spending, less efficiency and higher levels of public employment. Ashworth (Citation2005) verify the impact of political fragmentation in councils on long-term municipal debt of 298 municipalities in Flanders (Belgium) during the period 1977-2000. They conclude that fragmentation has no effect on public debt in the long-run, whereas a greater number of coalition parties leads to higher budget deficits in the short-run.

In a follow-up study, Ashworth et al. (Citation2014) consider the effect of political competition on the expenditure efficiency of 308 municipalities in Flanders for the year 2000 by using two proxies of electoral competition and three proxies of party fragmentation in the council. Their measurement of efficiency is the provision of public goods in terms of total expenditure. Their main finding is that electoral competition increases efficiency, whereas the impact of government fragmentation is negative. Despite these opposing effects, they argue that their results indicate that overall political competition leads to higher efficiency because the positive electoral competition effect is larger in magnitude than the negative fragmentation effect.

Borge (Citation2005) and Hagen and Vabo (Citation2005) measure the impact of political fragmentation in local councils on municipal budget deficits in Norway. They find that a council in the hands of few parties and a council majority that is aligned with the mayor lead to lower local budget deficits during the 1990s. Democratic participation (i.e. voter turnout), on the other hand, leads to higher efficiency. Rattso and Tovmo (Citation2002), reach different conclusions for another Scandinavian country. They find that during the period 1984–1996 the Herfindahl index of local councils of 275 Danish municipalities did not influence significantly local government revenue or spending.

More recently, Rodriguez Bolivar et al. (Citation2018) study the impact of political competition on the current budget of 138 Spanish municipalities during the period 2006-2014. They use three variables as proxies for political competition: a dummy variable that considers if one party has the absolute majority in the council, the Herfindahl index of the parties in the council, and the number of political parties in the council. They find that councils in which no party has the majority and in which many parties are present tend to have lower fiscal deficits; but, they also find that councils with a higher Herfindahl index tend to have lower deficits. Hence, the relationship between political competition and budget deficits is not clear from these results. Similarly, Suzuki and Han (Citation2019) do not present robust empirical evidence that (un)contested mayoral elections affected the fiscal performance of Japanese municipalities between 2006 and 2012.

Compared with first and second tier government studies, much less evidence for developing countries on the municipal level exists. A notable exception are case studies about Brazilian municipalities. Ferraz and Finan (Citation2011) study the impact of re-election incentives on local government corruption. Theoretical models argue that term limits remove responsiveness to voters demands (Ashworth Citation2012, 185) and Brazilian mayors can only be re-elected once. In line with the theoretical prediction, they find that during the government period of 2001–2004 Brazilian mayors who were in their second term misappropriate 27 percent more resources than mayors who were in their first term. Chamon et al. (Citation2019) also find that political competition improves local fiscal performance in Brazil. To be more precise, they find that municipality investment improves when the number of candidates is higher and loosing candidates receive a higher vote share.

In the same vein, Arvate (Citation2013) finds that a higher number of competitors in the election increased the provision of local public goods, but he does not find evidence that the margin of victory of the winner in a mayoral election in Brazil is significant. Boulding and Brown (Citation2014), on the contrary, find that a decrease in the margin of the winning party leads to higher deficits and lower social spending in Brazilian municipalities, whereas higher levels of voter turnout tend to increase social spending and reduce budget deficits. These results are partially in line with those from an early study about Mexico: Cleary (Citation2007) finds that voter turnout is a significant determinant of public good provision in Mexican municipalities, whereas the margin of victory of the winner in the election is not significant. He therefore concludes that the participation of citizens is more important for local government performance than the competition of parties.

With regard to Colombia, we are only aware of one existing study that explicitly aims to explore the impact of political competition on fiscal performance. Sánchez Torres and Pachón (Citation2013) study the link between cadastral updates and political competition between 1994 and 2009. They find that local political competition is not significant, while a higher number of local candidates and parties competing for House votes at the national level leads to more frequently updated cadastres. These updates help to build-up local fiscal capacity, which in turn results in better education and water coverage in Colombian municipalities. Another interesting result is reported by Ramírez, Díaz, and Bedoya (Citation2017), who control for political participation (voter turnout in departmental elections) and political competition (Herfindahl index of the votes that mayoral candidates receive and of the council seats from parties) when studying the effect of property tax revenue on multidimensional poverty in Colombia for the year 2005. They find that political participation in departmental elections is an important determinant to explain differences in multidimensional poverty gaps between Colombian municipalities but does not affect poverty rates. Local political competition, on the contrary, affected neither multidimensional poverty rates nor gaps.

3. The institutional setting of political and fiscal decentralization in Colombia

During most of the twentieth century Colombia was characterized by a very centralized system, in which the national government was not only the main tax collector and provider of local public goods and services but also appointed local administrations. Over the last three decades, however, the system has become more decentralized. The two most important reforms in this regard have been the Legislative Act 01 of 1986 and the new political constitution that was signed in 1991 (Gaitán Citation1988; Iregui, Ramos, and Saavedra Citation2001; Bonet, Pérez-Valbuena, and Montero-Mestre Citation2018). The Legislative Act 01 amended the constitution of 1886 by allowing the popular election of mayors and councilors in municipalities, while the new constitution establishes that Colombia is organized in the form of a unitary Republic, decentralized, with autonomy of its territorial entities, democratic, participatory and pluralistic (Const Citation1991, Art. 1).

Accordingly, local politicians are elected by their constituents (Art. 312), and departments, districts and municipal councils are allowed to levy their own fiscal and parafiscal contributions (Art. 338). To be more specific, municipal governments consist of a mayor (executive branch) and the local council (legislative branch). Mayors and councillors are elected every four years; mayors can only serve for a single term, while councillors have no term limits. The elections of the mayor and councillors are independent from each other (i.e. the party of the mayor can have a mayority in the council or not be represented at all).

Municipal councils play a key role in public administration at the local level in Colombia, exersing political control over the executive branch. In accordance with the constitution (Art. 313), important administrative decisions in the municipality, such as the local development plan, the municipal fiscal budget and changes to the land registry system, need to be discussed and aproved by the council. Hence, the implementation of local taxes and the use of govenrment expenditure depend on the decisions of the council. Local administrations mainly generate revenue through taxes on private real estate (predial), bussines income (industria y comercio), fuel sales (sobretasa a la gasolina) and vehicle tax (impuesto vehicular), and income that is generated from local public firms.

In addition to the right for municipalities to raise their own funds, the new constitution establishes a system that ensures the transfer of funds from the central government to local administrative units. These transfers are earmarked for the financing of the services for which the local governments are responsible according to the current law, with a general priority of covering health and educational services (Art. 356). After 1991 several fiscal reforms were enacted that aimed at decentralizing government expenditure and at improving coverage and efficiency of the provision of public goods (Iregui, Ramos, and Saavedra Citation2001). These reforms were overhauled in 2001 by the General Participation System (GPS) (Law 715, 2001).

The GPS establishes the general responsibilities of the national government and local governments in the provision of local public goods. Morover, it establishes the distribution of the transfers between different spending categories. It consists of two main funds: special assignments (4% of total funds) and sectoral distribution (the remaining 96%). Special assignments comprise transfers to indigenous reservations, the riverside area of the Magdalena River, territorial pension funds and school feeding programs. Sectoral distribution funds are designated to education, health, drinking water, basic sanitation and general purpose spending at the muncipality level. The size of GPS funds that each municipality receives depends mainly on its population size, its urbanization rate, and administrative and fiscal efficiency indicators.

Small and low-income municipalities especially have exhibited some difficulties in managing these resources efficiently. Accordingly, the central government has established certain criteria regarding indebtedness and fiscal sustainability (Law 358, 1997) and the maximum percentage of current income of free destination that is allowed to be used for operating expenses (Law 617, 2000). This percentage depends on the category of each municipality which is established according to the population level and the current income of free destination.

Next to the GPS, local administrations receive funds that stem from royalties derived from the exploitation of non-renewable natural resources (mainly oil, coal and gold). These transfers were first made under the National Royalty Fund (Law 141, 1994) and only applied to the regions that were involved in the exploitation or maritime transport of the resources. In 2012 (Law 1530) the criteria for the distribution of these royalities was changed into the General System of Royalties (GSR). GSR resources can now be used by all departments to finance local projects with special destinations so that the royality transfer to regions that are directly involved in the exploitation has decreased to about 10% of total royalties (Bonet, Pérez-Valbuena, and Montero-Mestre Citation2018). To receive funding, regions have to apply with projects that are related to local economic and environmental development, local investments in science, technology and innovation, and the improvement of the social conditions of the local population.

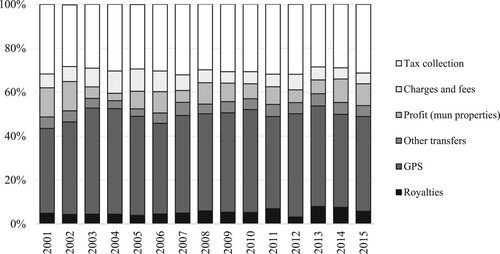

With regard to the relative importance of these different revenue sources for Colombian municipalities, shows that between 2001 and 2015, on average, local tax collection accounted for approximately 30% of total revenues, charges and fees for 7%, and revenue income from municipality-owned properties for 8.5%. The remaining 55.5% represents transfer income that stemmed mainly from the GPS funds (44%) and royalty payments (5.5%). The share of the different income sources has fluctuated somewhat but without any clearly visible trend changes. However, in absolute terms, both local spending and local revenue income have increased significantly during our period of analysis – municipal revenue from their own resources increased from 1.5% to 2.5% of GDP during the period 1994-–2009 (Sánchez Torres and Pachón, Citation2013).

Figure 1. Structure of municipal revenues in Colombia (2001-2015). Source: Own construction with data from DNP (2020).

This brief overview shows that transfers from the national government have been a fundamental part of the financial structure of municipalities over the last three decades. Given that these transfers are earmarked for specific spending categories, the degree of fiscal autonomy of municipalities in Colombia has been somewhat limited. However, the constitutional reforms at the beginning of the century enabled Colombian municipalities to increase their degree of fiscal autonomy to a substantial degree.

4. Methodology and data used

For estimating the impact of political competition and electoral participation on fiscal performance we use an unbalanced panel data fixed effects model, which allows us to control for unobserved time-invariant local institutional arrangements. To consider unobservable differences between municipalities is important to avoid biased estimation of the parameter of interest. The econometric specification is as follows:

(1)

(1) where

represents the fiscal performance of the municipality i during the government period t.

represents a variable of political competition, Z is a set of control variables, φ captures municipality fixed effects and

is the disturbance term.

It is important to note that the fiscal performance () represents the arithmetic mean of each of the four government periods (t) during the years 2000-2015, while the value of the political competition variable (

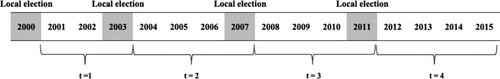

) depends on the elections that took place in the year before each government period began. During the sample period, local elections took place in October 2000, 2003, 2007, 2011 and 2015, while each government period began in January of the following year (see ).Footnote2 This setup helps us to account for potential endogeneity problems, given that the fiscal performance during each t could not influence the election results that defined the council seats prior to each t.

Figure 2. Local election years and government periods in Colombia (2000-2015).

Note: This diagramm gives an overview about the Colombia’s local election dates and government periods.

To make sure that this research design is valid and that the dependent variable does not follow an autoregressive process, we undertook unit root tests. We do not expect that the panel variables are cointegrated, given that we have a dataset with a small T and large N, but the above discussed dependence on national transfer payments and the monitoring that the national government exerts on the fiscal situation of local governments might imply that their fiscal performance does not reflect changing political realities but rather is path dependent. Nevertheless, the unit root tests indicate that the used fiscal performance variable is stationary (see in the Appendix), so that the proposed fixed effect regression is a valid method.

Regarding the variables used, our measure for the fiscal performance of municipalities is a readily available composite Fiscal Performance Index (Índice de Desempeño Fiscal) that has been constructed annually by Colombia’s National Planning Department (DNP) since 2001; to address the fiscal imbalances of local governments in Colombia the law 617 of 2000 established that the DNP has to evaluate the fiscal performance of all territorial entities and publish the obtained results on a yearly basis. Local fiscal performance can be analysed by various variables related to public finances, like revenue, fiscal balance, spending, investment, etc., however, it is not easy to establish which is the most appropriate indicator, since each one accounts for different but relevant aspects of fiscal management. Hence, we decided to use this composite indicator that is widely accepted and used in Colombia.

The index is calculated with Principal Components Analysis (ACP) and considering six aspects of municipal public finances: (i) the proportion of current income used for operating expenses, (ii) the proportion of disposable income that is supporting debt service, (iii) the proportion of total income stemming from transfers, (iv) the proportion of current income stemming from own resources, (v) the proportion of total expenditure for investment and, (vi) the savings capacity of the municipality.Footnote3 To get a better idea which of the subcomponents is mostly affected by political competition, we also provide regressions that consider each of these six variables as the dependent variable.

With respect to our two variables of interest, political competition and electoral participation, we use three different measures that are widely used in the literature: (i) the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) – normalized to 100 – as a measure of concentration (dispersion) of council seats; (ii) the share of the mayor's party of the total number of council seats as a measure of the influence of the administrative branch on the decisions of the legislative branch; and (iii) voter turnout, as a proxy for the willingness of citizens to monitor and sanction politicians. Higher values of the first two variables are related to greater concentration of political power, while a higher voter turnout is assumed to show that the population has a higher interest in the efficient provision of public goods and services (Borge, Falch, and Tovmo Citation2008). The council seat data was retrieved from the Center for Economic Development Studies (CEDE), while the voter turnout data was retrieved from the National Civil Registry Office.

In terms of control variables, we consider the following variables: (i) the political alignment of the mayor with higher levels of government, (ii) the education of constituents, (iii) incidence of violence, (iv) income and (v) population density. We account for educational quality by using as a proxy the average score of a national secondary education assessment test (Saber Pro 11). The literature argues that better-educated citizens tend to be more informed about politics, more politically active and to have a higher capacity to articulate their demands (Cleary Citation2007).

The political alignment of the mayor with higher tier governments, on the other hand, might negatively affect the fiscal performance of municipalities by discouraging their effort to generate own resources, given that their partizan ties might relax their budgetary restriction by allowing them access to other income sources. However, it can also have positive impacts if the partisanship translates into higher transfer payments from the state or national government. With respect to the latter, Bonilla Mejía and Higuera Mendieta (Citation2017) provide evidence that Colombian mayors that are aligned with the presidential coalition receive more transfers for road investments. The political alignment of the mayor with the party of the respective state governor and the president is treated as follows: it takes 0 if the political party of the mayor, governor and president are different; 1 if the mayor and governor belong to the same party; 2 if the mayor, governor and president belong to the same party.

Unfortunately, in the Colombian context it is also necessary to account for the prevalence of violence. For this we use the Armed Conflict Incidence Index (ACII) of the National Planning Department that considers the presence of illicit crops, the involvement of attacks made by illegal groups and the magnitude of crimes such as kidnapping. Their effects on local institutions and their fiscal performance are expected to be negative. Additionally, it is important to control for municipal income. The income of a municipality tends to be positively related with fiscal performance, given that citizens with higher income often more effectively demand that governments increase efficiency and because revenue collection tends to be easier so that governments can afford to provide more public services (Lake and Baum Citation2001). Unfortunately, as in most developing countries, in Colombia no local GDP per capita data is available. Instead we use the urbanization rate of each municipality as a proxy; previous studies show a close relationship between the level of economic development and urbanization rates (e.g. Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson Citation2005).Footnote4 Population density, on the other hand, is used to capture the fact that public goods provision is more difficult and expensive in sparsely populated rural areas (Lake and Baum Citation2001). Data for these two variables were retrieved from the CEDE database.

shows the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the regressions. The average Fiscal Performance Index of the sample is 62 (out of 100), with a standard deviation of 8. According to the classification of DNP, this implies that a representative Colombian municipality is in a vulnerable fiscal position. In addition, it is clear that a relatively high heterogeneity exists regarding the six fiscal performance subcategories. With regard to our three main variables of interest, all of them show an important heterogeneity between municipalities, either reaching the maximum or minimum values or being close to them. The HHI and share of the seats of the mayor’s party in the council mean value of 34 indicates a moderate concentration of power, while the average voter turnout of 63% shows that in most municipalities electoral participation is relatively high.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

The descriptive statistics of the control variables show that most Colombian municipalities are rural with a low population density: on average, the urban population rate is 43% and the population density is 144 inhabitants per square kilometre in absolute numbers. The education level has a low standard variation and the mean and maximum score is relatively low (the highest possible score a student can achieve in the test is 100); this indicates that in all municipalities the education levels are relatively low. Finally, the mean score of the armed conflict index is below 2, which shows that conflicts are concentrated in a small number of municipalities.

5. Results

shows the regression results of the impact of electoral participation and political competition on the fiscal performance of Colombian municipalities during the period 2000-2015. The results of regressions (i) and (ii) indicate that both the HHI of council parties and the share of council seats of the mayor’s party have a negative and statistically significant impact on the composite fiscal performance index. More specifically, the results indicate that one additional unit of the HHI (normalized to 100) lowers the average fiscal performance index during the government period by 0.12 points, while one additional unit in the share of the mayor’s party of total council seats lowers the fiscal performance index by 0.05 points. Regression (iii) shows that electoral participation also has the expected positive sign. That is to say, each additional percentage point of voter turnout leads to an increase of 0.22 points of the fiscal performance index of the municipality. All of these results are in line with political accountability theories, which argue that political competition and oversight from constituents incentivize career-concerned politicians to perform well and to reduce rent-extraction behavior.Footnote5

Table 2. The impact of political competition on the composite fiscal performance index.

The greater sensibility of the fiscal performance index to changes in the HHI relative to the seat share of the mayor’s party indicates that the concentration of political power in the hands of few parties is more important than the council’s alignment with the mayor’s party. This interpretation is confirmed in regression (iv). When all of the political competition variables are included in the same regression, the seat share of the mayor’s party loses its statistical signifcance. An explanation for this finding could be that the mayor is more likely to build alliances with the council when the political power within the council is more concentrated. Another explanation could be that the political affiliation is not very strong, which is evident in the fact that it is common that Colombian politicians are members of various political parties during their careers.

Most of the control variables are statistically significant and all have the expected sign. The positive coefficient of the education quality proxy suggests that citizen oversight might be important,| but this variable is not significant in most regressions. As expected, and in line with previous findings, the political alignment with the president or the state governor has positive effects on fiscal performance, most likely due to larger transfer payment receipts (see Bonilla Mejía and Higuera Mendieta Citation2017). The incidence of armed conflict, on the contrary, has the expected negative effect on fiscal performance. Finally, urbanization rates and population density have the expected positive effect, and their coefficients show that they play an important role in explaining fiscal performance differences.

Previous literature has established that the effect of political competition and electoral participation on fiscal performance can change with the popoulation size of municipalities. The polulation size of municipalities is strongly related with economic activity, which in turn affects levels of public goods provision, campaining resources and the motivation of voters to engage in elections and oversight (Boulding and Brown Citation2014). Consequently, the fact that many Colombian municipalities have a relatively low population size might influence the results. To explore this aspect, the regressions in split the muncipalities into quartiles, according to their population size in the year 2000. The sign, significance, and magnitude of the political competition variables and voter turnout are similar within each quartile, showing that the above results are not influenced by the population size of the municipality.

Table 3. Regression results by population quartiles

Finally, we verify the impact of political competition and electoral participation on each of the subcategories of the composite fiscal performance index (). The results indicate that a higher concentration of council seats affects five of the six categories negatively. To be more precise, municipalities with a lower HHI generate more own resources, invest more, have a higher saving capacity and lower operating expenses and debt service costs. The only subcomponent that is not affected by the HHI is the dependence on national transfers. Voter turnout, on the contrary, affects above all the generation of own resources positively. In line with the results from , the share of the mayor’s party in the council is less significant than the other two variables, having only a significant negative impact on the generation of own resources.

Table 4. The impact of political competition on fiscal performance subcomponents

6. Conclusions

Previous literature has provided mixed evidence with regard to the impact of electoral participation and political competition on fiscal performance. This paper has contributed to this literature by broadening the evidence base for developing countries by performing a case study for Colombia. Using a rich panel dataset of 1,098 municipalities and four government periods between 2000 and 2015, we provide evidence that the seat concentration in the council and the voter turnout have a significant positive impact on local fiscal performance in Colombia, whereas the alignment of the council with the mayor is less important.

A probable theoretical explanation for our empirical findings is that the veto power of parties in the council fends off rent extraction because it prevents the local administration reaching strategic alliances with the majority of the council. Our results, moreover, indicate that the weakening of the significance of the country’s two traditional parties (Liberals and Conservatives) and the emergence of various new parties over the last two decades has had positive effects on local fiscal performance in Colombia.

Having said all this, an important limitation needs to be pointed out. Our empirical approach is limited by the capacity of the used variables to capture the degree of political competition fully. The Colombian political system has the particularity that politicians tend to change parties relatively frequently (i.e. their party identification is often limited). Accordingly, the country is characterized by informal agreements that cannot be traced fully using data about electoral participation and the distribution of council seats. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to address this issue, readers should be aware of this limitation.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the VIII Jornadas Iberoamericanas de Financiación Local and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Rent extraction can be understood as the effort of politicians to extract existing rents instead of creating new rents (see e.g. McChesney Citation1987).

2 Please note that between 1991 and 2000 local councils were elected for three-year periods (Const., Citation1991, Art. 312). In 2002 the local government period was modified to four years (Legislative Act 02).

3 DNP calculates these six measures as follows: (i) Operating expenses ⁄Free destination budget*100; (ii) Debt Services⁄Disposable Income*100; (iii) National Transfer⁄Total Income*100; (iv) Tax Income⁄Current Income*100; (v): Investment⁄Total Expenditure*100; (vi) Current Savings⁄Current Income*100.

4 Please note that the main results are robust when municipal night-time lights are used as the income proxy instead of urbanization rates.

5 Please note that the main results are robust when we control for transfer payments from the central government. We choose not to include this variable in the main regressions due to endogeneity issues, given that one of the subcomponents of the fiscal performance index is the proportion of total income stemming from transfers.

References

- Ashworth, J. 2005. “Reputational Dynamics and Political Careers”. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 21 (2): 441–466.

- Acemoglu, D., S. Johnson, and J. A. Robinson. 2005. “The Rise of Europe: Atlantic Trade, Institutional Change, and Economic Growth.” American Economic Review 95 (3): 546–579.

- Aidt, T. S., and D. S. Eterovic. 2011. “Political Competition, Electoral Participation and Public finance in 20th Century Latin America.” European Journal of Political Economy 27: 181–200.

- Arvate, P. R. 2013. “Electoral Competition and Local Government Responsiveness in Brazil.” World Development 43: 67–83.

- Ashworth, J. 2005. “Reputational Dynamics and Political Careers.” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 21 (2): 441–466.

- Ashworth, J., B. Geys, B. Heyndels, and F. Wille. 2014. “Competition in the Political Arena and Local Government Performance.” Applied Economics 46 (19): 2264–2276.

- Ashworth, S. 2012. “Electoral Accountability: Recent Theoretical and Empirical Work.” Annual Review of Political Science 15: 183–201.

- Barrilleaux, C., T. Holbrook, and L. Langer. 2002. “Electoral Competition, Legislative Balance, and American State Welfare Policy.” American Journal of Political Science 46 (2): 415–427.

- Barro, R. 1973. “The Control of Politicians: An Economic Model.” Public Choice 14-14: 19–42.

- Bartolini, S. 1999. “Collusion, Competition and Democracy: Part I.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 11 (4): 435–470.

- Baskaran, T. 2013. “Coalition Governments, Cabinet Size, and the Common Pool Problem: Evidence from the German States.” European Journal of Political Economy 32: 356–376.

- Besley, T., and I. Preston. 2002. “Accountability and Political Competition: Theory and Evidence”. Mimeo. London School of Economics.

- Bonet, J., G. Pérez-Valbuena, and J. Montero-Mestre. 2018. “Las finanzas públicas territoriales en Colombia: dos décadas de cambios”. Documentos de Trabajo sobre Economía Regional y Urbana, No. 267.

- Bonilla Mejía, L., and I. Higuera Mendieta. 2017. “Political Alignment in the Time of Weak Parties: Electoral Advantages and Subnational Transfers in Colombia”. Banco de la Republica Documento de Trabajo sobre Economía Regional y Urbana, No. 260.

- Borge, L., T. Falch, and P. Tovmo. 2008. “Public Sector Efficiency. The Roles of Political and Budgetary Institutions, Fiscal Capacity, and Democratic Participation.” Public Choice 136: 475–495.

- Borge, L. E. 2005. “Strong Politicians, Small Deficits: Evidence from Norwegian Local Governments.” European Journal of Political Economy 21: 325–344.

- Boulding, C., and D. S. Brown. 2014. “Political Competition and Local Social Spending: Evidence from Brazil.” Studies in Comparative International Development 49: 197–216.

- Chamon, M., S. Firpo, J. M. P. de Mello, and R. Pieri. 2019. “Electoral Rules, Political Competition and Fiscal Expenditures: Regression Discontinuity Evidence from Brazilian Municipalities.” Journal of Development Studies 55 (1): 19–38.

- Cleary, M. R. 2007. “Electoral Competition, Participation, and Government Responsiveness in Mexico.” American Journal of Political Science 51 (2): 283–299.

- Const. 1991. Constitución Política de Colombia. 25ª ed. Legis.

- Datta, S. 2020. “Political Competition and Public Healthcare Expenditure: Evidence from Indian States.” Social Science & Medicine 244: 112429.

- De Haan, J., and J. E. Sturm. 1997. “Political and Economic Determinants of OECD Budget Deficits and Government Expenditures: A Reinvestigation.” European Journal of Political Economy 13: 739–750.

- De Haan, J., J. E. Sturm, and G. Beekhuis. 1999. “The Weak Government Thesis: Some new Evidence.” Public Choice 101: 163–176.

- Ferejohn, J. 1986. “Incumbent Performance and Electoral Control.” Public Choice 50: 5–25.

- Ferraz, C., and F. Finan. 2011. “Electoral Accountability and Corruption: Evidence from the Audits of Local Governments.” American Economic Review 101: 1274–1311.

- Gaitán, M. d. 1988. “La elección popular de alcaldes: un desafío para la democracia.” Análisis Político 3: 94–102.

- Galli, E., and F. Padovano. 2002. “A Comparative Test of Alternative Theories of the Determinants of Italian Public Deficits (1950–1998).” Public Choice 113: 37–58.

- Gosh, S. 2010. “Does Political Competition Matter for Economic Performance? Evidence from Sub-National Data.” Political Studies 58: 1030–1048.

- Hagen, T. P., and S. I. Vabo. 2005. “Political Characteristics, Institutional Procedures and fiscal Performance: Panel Data Analyses of Norwegian Local Governments, 1991–1998.” European Journal of Political Research 44: 43–64.

- Holbrook, T., and E. van Dunk. 1993. “Electoral Competition in the American States”. American Political Science Review 87: 955–962.

- Iregui, A. M., J. Ramos, and L. A. Saavedra. 2001. “Análisis de la descentralización fiscal en Colombia”. Borradores de Economía, No. 175.

- Lake, D. A., and M. A. Baum. 2001. “The Invisible Hand of Democracy: Political Control and the Provision of Public Services.” Comparative Political Studies 34 (6): 587–621.

- Lowndes, V., L. Pratchett, and G. Stoker. 2001. “Trends in Public Participation: Local Government Perspectives.” Public Administration 79 (1): 205–222.

- McChesney, F. S. 1987. “Rent Extraction and Rent Creation in the Economic Theory of Regulation.” Journal of Legal Studies 16 (1): 101–118.

- Padovano, F., R. Ricciuti, S. P. Choice, and N. Mar. 2013. “Political Competition and Economic Performance: Evidence from the Italian Regions.” Public Choice 138 (3): 263–277.

- Perotti, R., and Y. Kontopoulos. 2002. “Fragmented Fiscal Policy.” Journal of Public Economics 86 (2): 191–222.

- Persson, T., G. Roland, and G. Tabellini. 1997. “Separation of Powers and Political Accountability.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 112 (4): 1163–1202.

- Ramírez, J. M., Y. Díaz, and J. G. Bedoya. 2017. “Property Tax Revenues and Multidimensional Poverty Reduction in Colombia: A Spatial Approach.” World Development 94: 406–421.

- Rattso, J., and P. Tovmo. 2002. “Fiscal Discipline and Asymmetric Adjustment of Revenues and Expenditures: Local Government Responses to Shocks in Denmark.” Public Finance Review 30 (3): 208–234.

- Remmer, K. L., and E. Wibbels. 2000. “The Subnational Politics of Economic Adjustment. Provincial Politics and Fiscal Performance in Argentina.” Comparative Political Studies 33 (4): 419–451.

- Rodriguez Bolivar, M. P., A. Navarro Galera, M. D. Lopez Subires, and L. Alcaide Muñoz. 2018. “Analysing the Accounting Measurement of Financial Sustainability in Local Governments Through Political Factors.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 31 (8): 2135–2164.

- Roubini, N., and J. Sachs. 1989. “Political and Economic Determinants of Budget Deficits in the Industrial Democracies.” European Economic Review 33 (5): 903–933.

- Rumi, C. 2009. “Political Alternation and the fiscal Deficits.” Economics Letters 102: 138–140.

- Sánchez Torres, F., and M. Pachón. 2013. “Decentralization, fiscal effort and social progress in Colombia at the municipal level, 1994-2009: Why Does National Politics Matter?” IDB Working Paper, No. 396.

- Schaltegger, C., and L. P. Feld. 2009. “Do Large Cabinets Favor Large Governments? Evidence on the Fiscal Commons Problem for Swiss Cantons.” Journal of Public Economics 93: 35–47.

- Schaltegger, C. A., and B. Torgler. 2007. “Government Accountability and Fiscal Discipline: A Panel Analysis Using Swiss Data.” Journal of Public Economics 91: 117–140.

- Stigler, G. J. 1972. “Economic Competition and Political Como.” Public Choice 13: 91–106.

- Suzuki, K., and Y. Han. 2019. “Does Citizen Participation Affect Municipal Performance? Electoral Competition and Fiscal Performance in Japan.” Public Money and Management 39 (4): 300–309.

- Tornell, A., and P. R. Lane. 1999. “The Voracity Effect.” American Economic Review 89 (1): 22–46.

- Volkerink, B., and J. de Haan. 2001. “Fragmented Government Effects on fiscal Policy: New Evidence.” Public Choice 109: 221–242.

- Yogo, U. T., and M. M. Ngo Njib. 2018. “Political Competition and Tax Revenues in Developing Countries.” Journal of International Development 30 (2): 302–322.

Appendix

Table A1. Unit root test of the fiscal performance index.