?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The aftermath of over 50 years of uninterrupted conflict is not only underdevelopment and casualties. It is also the loss of social ties, the mistrust, and the difficulties to build a society where victims live with those who once were their perpetrators. These difficulties are many times linked to strong negative affect, prejudice, and skepticism towards forgiveness and reintegration. This paper uses the 2016-Americas Barometer database to provide empirical evidence of how Colombians’ attitudes towards the FARC-EP shape the probability of believing in forgiveness and supporting the reintegration process. We find that for demobilization to be successful a society needs (i) to reduce the perception of danger when surrounded by former rebels, (ii) to enhance perceptions of friendliness and hard-working on behalf of the ex-combatants, and (iii) to be more educated and allow the victims to speak up.

1. Introduction

Since the 1980s, it has become increasingly common for countries to end their armed conflicts through disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) processes. With these processes, Muggah (Citation2008) warns on how fragile peace is when the armed conflict's underlying causes are still alive. Although the violence may disappear for a time, embers continue to burn to wait for a spark to reactivate the confrontation. The fragility is due to the economic deterioration and social isolation of the ex-combatants, for which frustration and desperation may lead their way back to join armed groups (Knight and Özerdem Citation2004; Bauer, Fiala, and Levely Citation2017). As Nussio (Citation2009) points out, discrimination, life threats, and political confinement also exacerbate the former rebels’ intention to go back to combat.

DDR processes include reintegration and reconciliation. The rebel party agrees to reintegrate into society, committing to cease fire and become a productive actor, in exchange for economic, political, and judicial benefits (Muggah Citation2008). However, reconciliation is a hazardous multidimensional process in which both parties must agree with peacefully addressing any situation, triggering animosity, and discrimination of ex-combatants. In the Colombian conflict, these situations are related to social inequality, narcotraffic, and common resources’ exploitation.

Hagmann and Nielsen (Citation2002) point out that the demobilized are usually received with feelings of mistrust, resentment, and even envy when receiving public aid and benefits from governments. In a sense, efforts to facilitate their economic integration by offering them a safety net can undermine reconciliation (Annan and Patel Citation2009). Most of the DDR processes include these reconciliation initiatives carried out with extreme caution not to become the spark igniting a new confrontation (Blattman, Hartman, and Blair Citation2011). For this process to succeed, it requires both the rebels’ goodwill and society's acceptance. Nevertheless, acceptance goes beyond forgiveness and entails seeing the new actor as an equal, overcoming prejudices against ex-combatants, and the anxiety for the new status quo.

In 2016, the Colombian government and the Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces (FARC-EP) signed a peace accord to end 52 years of uninterrupted conflict between the two. This is not the only DDR experience that Colombia has had in recent times. In the last five decades, the Colombian government negotiated a permanent ceasefire with other irregular armed groups such as the M19, the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), the Quintín Lame-MAQL Armed Movement, the revolutionary workers’ party (PRT) (Pares Citation2019), and the Colombian United Self-Defense (AUC). However, previous attempts to negotiate a similar peace agreement with the FARC failed, and the prospects of ending the confrontation were rather pessimistic (Castaño Citation2019).

The FARC has a lousy reputation among Colombians for its arbitrary acts during the conflict. The long tradition of right-wing governments and conservative norms among the population made negotiation and reintegration a real challenge (Villarraga Citation2015). According to the Democracy Observatory, in 2016, the peace agreement support was below 50% among Colombians, and 46.5% of them said they did not want a demobilized person in their neighborhood. They were perceived as potential criminals, as happened with the AUC's demobilized (Muggah Citation2008). As a result, when the FARC's peace process was cast out in a plebiscite, the proportion of people voting against outweighed those in favor by less than one percentage point, and with a 38% turn-out. Despite the rejection of the peace accord in the plebiscite, a variant of the peace agreement was approved in parliament, and the DDR went through. The process meant a threat to the reconciliation possibilities, regardless of any ex-combatants’ genuine interest in reintegrating into society.

This paper tries to understand the underlying mechanisms behind the rejection of former FARC combatants from two perspectives: forgiveness and reintegration public support. Are these two variables related? What are the socioeconomic, behavioral, and demographic characteristics explaining any correlation? This analysis is essential for post-conflict countries as DDR's social acceptation is required to avoid the danger of igniting a new confrontation cycle (Muggah Citation2008; Blattman, Hartman, and Blair Citation2011).

Forgiveness has been defined as the ability to use compassion to let go of the negative affect while providing a positive response to the perpetrator (Rye and Pargament Citation2002; Menezes Fonseca, Neto, and Mullet Citation2012; Mukashema and Mullet Citation2013; López-López et al. Citation2018; Pineda-Marín, Muñoz-Sastre, and Mullet Citation2018). It is, in general, sensitive to the existence of an apology. However, it is rare and complex when there is inter-group animosity (Hornsey and Wohl Citation2013; Noor, Branscombe, and Hewstone Citation2015). In such cases, feelings of threat exacerbate collective anguish, anger, and anxiety (Wohl and Branscombe Citation2009). Additionally, it is more frequent the victimizer's dehumanization, and their actions are perceived as unforgivable (Tam et al. Citation2007; Voci et al. Citation2015). In this context, to promote inter-group forgiveness, there must be a switch in the counterpart's perceptions and emotions. For instance, friendly contact between groups might reduce prejudices and increase the likelihood of forgiveness (Pettigrew Citation1998; Swart et al. Citation2011; Noor, Branscombe, and Hewstone Citation2015). Additionally, since apologies may not be enough, the victimized group must perceive a change in attitude and regret on behalf of aggressors to be ready to forgive (Tam et al. Citation2007; Voci et al. Citation2015).

We study the extent to which attitudes towards forgiveness and reintegration support are linked. Is a DDR process possible if individuals cannot forgive ex-combatants? Are those who are more optimistic about forgiveness also willing to support the FARC-EP reintegration? What socioeconomic factors explain these two events? Do factors work separately or jointly? We contribute to the post-conflict literature by bridging three behavioral determinants of forgiveness and reconciliation (reintegration support): behavioral biases (parochialism), negative affect, and prejudices. Even when the effect of conflict exposure may generate parochial preferences (Bauer, Fiala, and Levely Citation2017), this is the first attempt to use parochialism to link forgiveness and reintegration.

Following recent work, we hypothesize that discriminatory biases (lack of trust and cooperation), negative affect (envy, fear, and anxiety), and prejudices (unfriendly, lazy, violent, dangerous perceptions) might reduce both the forgiveness perception and reintegration support (Bellows and Miguel Citation2009; Blattman, Hartman, and Blair Citation2011; Voors et al. Citation2012; Bauer, Fiala, and Levely Citation2017; Restrepo-Plaza Citation2019, among others). We also hypothesize that an apology will increase the forgiveness perception (Voci et al. Citation2015), but it will not impact reintegration. Finally, we are agnostic regarding the socioeconomic and demographic effects, except for the political orientation, which drives subjects’ opinions on the FARC. We pay special attention to the victim status due to the contradictory evidence available. While there is plenty of evidence of in-group favoritism in Burundi and Sierra Leone, new evidence points in the opposite direction in the Colombian context (Restrepo-Plaza Citation2019; Unfried, Ibañez, and Restrepo-Plaza Citation2020).

We use the 2016-Americas Barometer to test our hypotheses. The Barometer is a longitudinal database; however, the section feeding this paper was only available for 2016. Thus, ours is a cross-sectional analysis. We estimate two bivariate Probit models to measure the effect of apologies, emotions, prejudices, parochialism on forgiveness, and reintegration. Our results suggest that apologies, feelings of calm when surrounded by ex-combatants, and perceptions of friendliness and hard work play a positive role. We also find that more educated individuals and those wounded by conflict were more likely to support former FARC members’ reintegration, even when it did not mean to be open to forgiveness. Our results may shed light on the DDR process attributes for the demobilization to succeed. The rest of the paper is divided into four sections. Section 2 presents the conceptual framework. In section 3, we describe our empirical strategy. In section 4, we display parametric and non-parametric results. In section 5, we conclude.

2. Conceptual framework: parochialism, negative affect and prejudices

This section will describe the literature dialogue regarding parochialism, prejudices, and emotions, while we will stress their connection to forgiveness and reintegration support.

There is plenty of literature explaining how exposure to conflict exacerbates parochial preferences among the victims. Bauer et al. (Citation2016) brings together 20 studies and finds that in post-war societies, it is more challenging to construct social capital, collective action, and trust. However, people develop high levels of cooperation that are better profiled as parochial preferences than plane prosociality. It means that communities are more collaborative within the group, but there is more antagonism towards external groups. Such a result is replicated in the forgiveness domain, as Wohl and Branscombe (Citation2009) found that even primed and hypothetical exposure to violent threats become individuals more inclined to provide ingroup rather than outgroup forgiveness.

Our literature revision also finds that parochialism is the most frequent finding when examining the effect of exposure to conflict on prosocial attitudes. That is the case for Sierra Leone, where there is survey-based evidence for prosocial preferences formation, measured as individuals’ willingness to meet in local committees, attend parent meetings, and go out to vote (Bellows and Miguel Citation2006; Bellows and Miguel Citation2009), and experimental-based evidence for ingroup favoritism (Cecchi, Leuveld, and Voors Citation2016). The same is true for Burundi (Voors et al. Citation2012) and Northern Ireland (Silva and Mace Citation2014). However, in the latter study, authors emphasize that the ingroup donations made by members of higher social status were not driven by altruism but rather by competing against their peers in the rival group (Catholics/protestants).

Gangadharan et al. (Citation2017) conducted a study on the exposure to the genocide of the Khmer Rouge regime (1975–1979) in Cambodia to find that more than 30 years after the violence peak, those who were direct victims of the violence exhibited more antisocial behavior. Such a result departs from the parochialism mentioned before, which could be because they report a long-term effect, and the violence subjects were exposed to was directly inflicted by the government and not an external group. The regime, wanting to implant an agrarian communist utopia, massacred and tortured the population and instigated spying on and sabotaging each other, which eroded social cohesion.

The Colombian context does not necessarily fit with parochialism either. Restrepo-Plaza (Citation2019) found evidence for parochialism and outgroup discrimination among those who have not been victims of conflict in a Public good setting but also find significantly less discrimination against ex-combatants, and non-parochial behavior from the victims. Following the same line, Bogliacino, Gómez, and Grimalda (Citation2019) ran a lab-in-the-field experiment to measure the effect of exposure to violence on prosocial attitudes via a prisoner’s dilemma and a dictator game. They found That those exposed to higher levels of violence demonstrated a greater intention to cooperate in the dictator’s games and the prisoner’s dilemma compared to their peers. The authors associate this effect with the trauma of having been victims and the negative shock to their wealth, which boosts social cognition. Finally, Unfried, Ibañez, and Restrepo-Plaza (Citation2020) run a crowdfunding exercise among college students in Colombia, manipulating whether the recipient was a former rebel. They did not find evidence for discrimination against ex-combatants relative to a vulnerable population with similar socioeconomic characteristics.

Prejudice towards former rebels is the result of a cocktail mixing group identity, social norms, and resentment. The mere artificial fact of belonging to a group, say FARC, boost more negative perceptions and discrimination than ethnicity or nationality (Akerlof and Kranton Citation2000; Akerlof and Kranton Citation2005; Lane Citation2017). That is the Colombian case, where even though the proportion of Colombians against the forgiveness to ex-combatants had decreased, most individuals are still reluctant to forgive former guerrilla members (López-López et al. Citation2013; López-López et al. Citation2018). Policy-makers and the media commonly assume that former soldiers of violent armed groups are ‘social outcasts’ who remain silently in conflict (New York Times Citation2006). Unfried, Ibañez, and Restrepo-Plaza (Citation2020) found that even when college students were willing to donate equal amounts to an ex-combatant and a non-ex-combatant, there is evidence of prejudice and skepticism. They also found prejudice reduction towards former rebels through a contact intervention that seemed to diminish fear and change subjects’ expectations regarding the ex-combatants.

Nonetheless, prejudice against ex-combatants seems to be context-dependent. Bauer, Fiala, and Levely (Citation2017) explain the effect of witnessing children force recruitment in Burundi. Nine years after the conflict, there is no evidence of systematic discriminatory behavior. Moreover, the ex-combatants’ parents show higher trust levels than their neighbors as they were aware of the former rebels’ willingness to reincorporate. The authors warn about the non-generalization of these results because, in settings where the conflict's participation is voluntary, chances to develop prejudices and engage in discriminatory behavior are high.

The role of society’s emotions is non-negligible for forgiveness and a successful reintegration process. Blattman, Hartman, and Blair (Citation2011) present the Liberian reconciliation process results of a 14-year conflict. The authors stress the importance of being extremely careful when carrying out a reconciliation process. By bringing together the parties previously in conflict, there is a decadence of psychological well-being. Moreover, controversial dialogues may increase, which could put themselves at risk of reactivating the armed conflict. Other studies such as Hagmann and Nielsen (Citation2002) and Knight and Özerdem (Citation2004) acknowledge that DDR processes aggravate feelings of resentment and even envy due to the support that ex-combatants receive on behalf of the government, which may consist of vocational training and economic support. However, trying to improve their situation becomes a dilemma regarding reconciliation with the community (Annan and Patel Citation2009).

Willingness to forgive varies from person to person, and such change is associated with cultural, family, religious, and personality characteristics. Long-term feelings of resentment and a long-lasting inability to forgive are usually the most strongly correlated with demographic characteristics (such as education, gender, ethnicity, and age) and personal relations(Menezes Fonseca, Neto, and Mullet Citation2012; Pineda-Marín, Muñoz-Sastre, and Mullet Citation2018). In recent times, forgiveness has gained greater importance for political relations, ceasing to be just a religious thought and becoming an essential factor in the recovery of post-conflict societies. López-López et al. (Citation2018) find that forgiveness is a necessary but insufficient condition for reconciliation. Although the authors recognize that forgiveness and reintegration are different theoretical constructions, these are strongly associated.

The good news is that in post-conflict societies, there is evidence supporting that inter-group forgiveness and prejudice reduction is possible when there are crossed friendships or any contact between groups (Swart et al. Citation2011). According to Pettigrew (Citation1998), this is feasible because contact 1. increases learning about the external group; 2. updates the norms on external group behavior; 3. Promotes behavioral change of the group members; 4. creates positive and decreases negative affect. This evidence is consistent with reducing statistical discrimination against FARC-EP ex-combatants via a video where they presented their life-story and a business idea (Unfried, Ibañez, and Restrepo-Plaza Citation2020) and the promotion of forgiveness in the sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland (Tam et al. Citation2007). The later result is partially cast doubt by Voci et al. (Citation2015). They found that even when contact reduces prejudice, forgiveness was more challenging to achieve due to the difficulty of identifying specific offenders and the fact that some of the crimes committed were perceived as unforgivable (Exline et al. Citation2003).

3. Empirical strategy

We used the 2016-Americas Barometer and Democracy Observatory dataset. The population sample is representative of the urban label. It consists of 1,563 non-institutionalized (prisons, hospitals, and military) Colombian residents that have reached legal age. Subjects were randomly selected to participate in an interview, following a multi-stage randomization protocol. In this survey version, the observatory included questions concerning the Colombians’ perception of the FARC-EP peace process and transitional justice, which is the primary input of this document.

We used 20 variables to compute the effect of apologies, emotions, prejudices, behavioral biases, socioeconomic and demographics characteristics on forgiveness and reintegration support. in the appendix shows each variable with its description.

Our outcome variables are the forgiveness to FARC-EP perception and the support to their reintegration. The former was cast in the questionnaire by asking whether the individuals believed forgiveness and reconciliation with former FARC members were possible (forgiveness). The latter was framed as whether the respondent agreed to reintegrate FARC ex-combatants into society (reintegration). Forgiveness is a first-order belief variable that allows us to acknowledge the presence of social norms that could prevent society from reaching a general reconciliation. Reintegration comprises an individual statement that represents the subjects’ injunctive norm. Both beliefs and injunctive norms tend to be tightly linked (Bicchieri Citation2006); therefore, our empirical strategy consists of estimating a Probit models’ system to account for the errors’ correlation. This bivariate method has been used in different domains. Restrepo-Plaza (Citation2017) used it to measure the effect of red-carded captains on football team performance. Flores and Price (Citation2018) used it to estimate the determinants of searching and switching to new electricity providers.

We incorporated different variables studied in the literature, but that has not been all put together to explain forgiveness and reintegration at once. Following Voci et al. (Citation2015), we included the ‘apology’ question in our analysis. We also accounted for differences associated with fear, envy, and anxiety (Blattman, Hartman, and Blair Citation2011; Unfried, Ibañez, and Restrepo-Plaza Citation2020). Fear and anxiety were obtained through questions where the individuals reported, on a 1–7 Likert scale, how they would feel if FARC ex-combatants surrounded them. The survey directly assesses calmness, anxiety, danger, and safety. Since the literature also suggests that envy and resentment could play a fundamental role in accepting former rebels back into society (Knight and Özerdem Citation2004), we included a proxy variable that captures whether the subject believes that the government should be the one compensating the victims. Higher values of this variable imply lower envy levels. Thus, it should be inversely interpreted.

Prejudices against ex-combatants also have a non-negligible impact on forgiveness and reintegration support (Unfried, Ibañez, and Restrepo-Plaza Citation2020). In our estimations, we included the extent to which respondents perceived the FARC ex-combatants as friendly, violent, lazy, hard-workers, and dangerous. Parochialism was accounted for following the Bauer et al. (Citation2016) approach, i.e. computing a participation bias. It is the difference between the subject’s willingness to participate in peace-related activities as opposed to in-group events (religious, school meetings, community meetings). We also incorporated a novel variable that measures trust bias as the difference between FARC and the National Army Forces’ reported trust. Finally, we control for demographic and socioeconomic characteristics as they seem to affect forgiveness and reintegration support (Menezes Fonseca, Neto, and Mullet Citation2012; Restrepo-Plaza Citation2019).

Even though the demographics and the parochialism variables are available for the full sample, emotions and apologies on one side, and perceptions on the other, were respectively collected for two subsamples extracted from the main one. Since the questionnaire assignment was random, we shall no expect systematic differences between the two groups. Nonetheless, we are restricted to estimate the effects separately.

We develop a combination of parametric and non-parametric analyses to contrast our hypotheses. In the first model, we incorporate the apology effect, as well as the role of emotions, parochialism, demographic and socioeconomic controls (equations 1, 2, and 3).

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

In the second model, we remove the apology and the emotions to integrate the interviewees’ perceptions of the demobilized (prejudice). Socioeconomic and parochialism variables remain in the estimation (equations 4, 5, and 6).

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

4. Results

4.1. An overview of forgiveness and reintegration support

The Americas-Barometer database provides information for our conceptual framework: the apology existence, demographics, emotions, perceptions, and parochialism. displays a description of the apology role and socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. In contrast to our hypothesis, but consistent with Hornsey and Wohl (Citation2013) and Noor, Branscombe, and Hewstone (Citation2015), the existence of an apology does not make subjects more expectant about forgiveness (p-value = 0.1090). Instead, it makes a difference for those who promote the reintegration (p-value = 0.0012). There is a balanced sample of men and women, and the Fisher exact test suggests that the proportion of men that believe in forgiveness (59.0%) and support former FARC members (65.5%) is significantly larger (p-value < 0.0000) than the proportion of women. We counted 610 victims (38.7%), i.e. individuals who reported to have been directly or indirectly (through their families) wounded by the Colombian conflict. They did not report differences in forgiveness (p-value = 0.397); however, in line with Restrepo-Plaza (Citation2019), relative to non-victims (54.6%), victims were more willing to support the DDR process (66.0%) (p-value < 0.000). We also notice that more optimistic subjects in terms of forgiveness were four years older (p-value = 0.0018), and those willing to support the reintegration were two years older than those in an opposing stand (p-value = 0.0000). The education level did not account for forgiveness differences, but more educated fellows were more willing to stand next to the reintegration (p-value = 0.0008). Finally, even when the general sample seems to be placed in the center of the political spectrum (5.45/10), those with higher forgiving expectations and more willing to support the reintegration of the ex-combatants were slightly but significantly leaned to the right (p-value < 0.01 in both cases).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics.

Coinciding with Bogliacino, Gómez, and Grimalda (Citation2019) and Bauer, Fiala, and Levely (Citation2017), in , we find that individuals’ that believed in the possibility of forgiving former rebels and that support the reintegration of ex-combatants reported feeling significantly more calmed (p-value < 0.01), safe (p-value < 0.01), and surprisingly, more anxious (p-value < 0.05) in a hypothetical situation where the subject was to be surrounded by former FARC members. Feelings of danger did not seem to affect their support to the DDR process (p-value = 0.1455), while it diminished forgiveness expectations (p-value = 0.0075). On the contrary, envy, measured as the inverse of individuals’ agreement of the government funding the victims’ compensation (Annan and Patel Citation2009), seems to reduce the reintegration support (p-value = 0.033) but does not affect forgiveness (p-value = 0.577).

Table 2. Emotions when near an ex-combatant.

presents the averages, standard errors, and p-values for perceptions of individuals with optimistic forgiveness expectations, and those who were more skeptics, and individuals supporting the FARC-EP reintegration, and those who disagreed with it. We see that the forgiveness optimistic and the reintegration supportive perceived former guerrilla members significantly more friendly, hard-workers, and less dangerous than those who exhibit skepticism (p-values < 0.01). Interesting enough, the perception of how violent (4.53) and lazy ex-combatants were, was relatively high (3.83), yet not determinant for forgiveness nor DDR support (p-values > 0.05).

Table 3. Perceptions regarding ex-combatants.

We understand parochialism as the behavioral bias that makes a person positively leans towards the ingroup. We used participation bias as a proxy of pro-sociality bias. Here we account for those individuals who would not participate in meetings promoting the FARC-EP peace accord but would otherwise participate in events seeking the higher good through community, religious, political, and school meetings. We also computed a trust bias indicator that comprises the difference between trusting in the FARC-EP (as an irregular armed organization) and trusting the National Armed Forces (as the armed legal organization). This variable allows us to disentangle the extent to which subjects’ trust is mediated by combat or by the organization’s acceptance itself. The results point to different directions. While the reintegration support does not exhibit systematic differences in participation or trust biases, subjects who believed in forgiveness showed significantly more participation bias (−0.51 vs. −0.46, p-value = 0.0081) and less trust bias (−2.50 vs. −2.86, p-value = 0.0045) than those who were not into forgiveness ().

Table 4. Parochialism.

4.2. Between optimists and skeptics

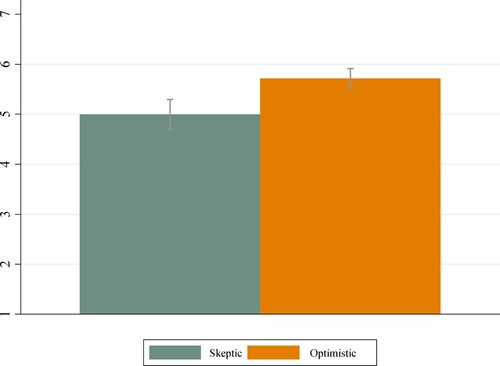

This section describes our main variables by accounting for differences in the way subjects jointly approach forgiveness and reintegration support. We focus on those who have optimistic views regarding the forgiveness possibility and, at the same time, support the ex-combatants’ reintegration (44.34%), and those who are skeptic to both forgiveness and reintegration (33.77%). We will call the first group, the optimistic and the second the skeptic. Combined, they comprise 78.10% of the population. shows that the supportive is more reliant on the apology to promote reconciliation between FARC-EP and the Colombian society (p-value = 0.0036). We shall expect better results of symbolic and commemorative events in this group.

Figure 1. The Role of Apologies by Joint Stand towards FARC-EP DDR Process. Note: presents the average of the reported role of apologies in promoting forgiveness among victims and perpetrators, and the confidence intervals at 95%. Means are categorized by the joint stand regarding forgiveness to and reintegration support of the FARC-EP former rebels.

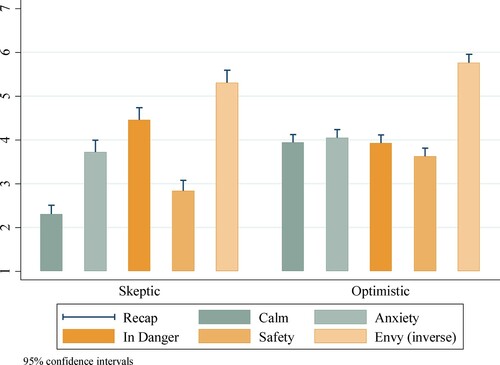

gives us three messages. The first one is that, relative to the optimistic, in the skeptic group, calmness (p-value = 0.000) and safety (p-value = 0.000) are scarce when imagining being surrounded by former guerrilla members, and anxiety (p-value = 0.0206) and fear (p-value = 0.0035) are predominant emotions. The second message is that such emotions are all present in the optimistic group, yet they are all in similar amountsFootnote1, for which we cannot discard that they are canceling each other out. Finally, we notice low envy levels in both groups, which are not significantly different to one another (p-value = 0.0993).

Figure 2. Average Emotions by Joint Stand towards FARC-EP DDR Process. Note: presents the average of the reported emotions when surrounded by ex-combatants, and envy (measured as the extent to which subjects agree with the government providing victims’ compensation), and the confidence intervals at 95%. Means are categorized by the joint stand regarding forgiveness to and reintegration support of the FARC-EP former rebels.

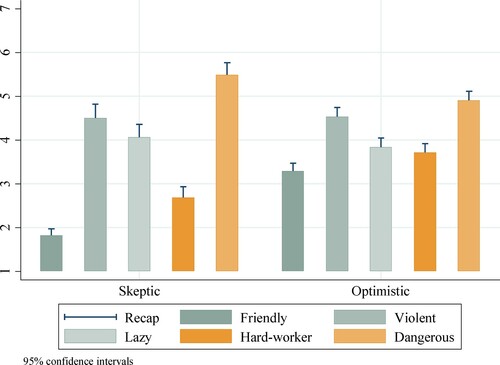

In , we can see how prejudices might affect how the interviewees report their beliefs about forgiveness and their support to the ex-combatants’ reintegration. By making a side to side comparison, we can see no many differences in how violent (p-value = 0.4401) or lazy (p-value = 0.1622) people think a demobilized is. Nonetheless, there are apparent differences in their perception of how friendly (p-value = 0.000), dangerous (p-value = 0.000), and hard-workers (p-value = 0.000) the ex-combatants are – being, of course, less prejudiced-like those in the optimistic group.

Figure 3. Average Perceptions towards Ex-combatants by Joint Stand towards FARC-EP DDR Process. Note: presents the average of the reported perceptions towards ex-combatants and the confidence intervals at 95%. Means are categorized by the joint stand regarding forgiveness to and reintegration support of the FARC-EP former rebels.

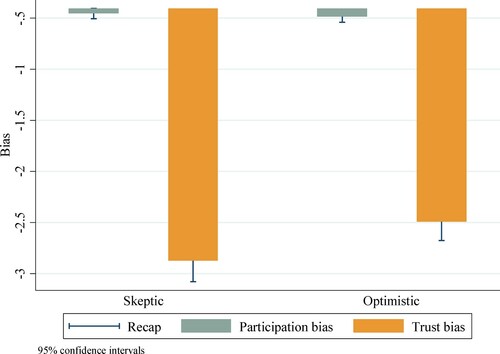

Parochialism, in , is giving us two stories. On the one hand, pro-sociality bias, measured through the participation bias, is slightly and only marginally stronger for the optimistic group (p-value = 0.0499). However, trust is indeed a profiling characteristic. Those who were more reluctant to believe in the possibility of forgiveness and disagree with ex-combatants’ reintegration into society, exhibit more considerable trust bias than those who stand on the opposite side (the optimistic, p-value = 0.0087).

Figure 4. Average Parochialist Biases by Joint Stand towards FARC-EP DDR Process. Note: presents the average of the participation and trust bias and the confidence intervals at 95%. While participation bias is the difference between an individual willingness to participate in meetings promoting the Peace Accord, Trust bias is the difference between the respondent’s trust in a FARC-EP ex-combatant and the National Armed Forces. Means are categorized by the joint stand regarding forgiveness to and reintegration support of the FARC-EP former rebels.

4.3. The determinants of forgiveness and reintegration

In this section, we shall describe the effects of our conceptual framework on subjects’ forgiveness beliefs (forgiveness), their support to the DDR process (reintegration), and the joint probability of these events happening simultaneously (optimist). The effects we observe in are robust to different model specifications. Due to the database restrictions, we can only control for the apology existence and emotions in Model 1(columns 1, 2, and 3) and for prejudice against ex-combatants in Model 2 (columns 4, 5, and 6). Parochialism and socioeconomics are present in both.

Table 5. Bivariate Probit Marginal Effects on the probability of having optimistic views regarding forgiveness and to support the reintegration process of FARC-EP members.

We find that the existence of an apology increases in 6.2 percent points (pp) the probability of an individual to believe in forgiveness, to support the FARC-EP reintegration (8.2pp), and to report optimistic views in both domains (2.9pp). Something similar occurs with feelings of Calm, which boost forgiveness, reintegration, and the joint probability, but it does so with a stronger effect (25.6pp, 23.7pp, and 10.2 pp, respectively). As already forecasted in the non-parametric description, Anxiety has an unexpected effect, i.e. it boosts forgiveness (10.2pp) and the joint probability (3.5pp). At the same time, it does not affect the reintegration support on its own. Feeling in Danger is insignificant for reintegration, but it decreases the probability of having optimistic views about forgiveness (−11.5%) and the probability of being optimistic in both domains altogether (−3.7pp). Safety and Envy have no significant impacts on our outcome variables.

The role of prejudices partially mirrors our findings in the descriptive analysis. We find that the friendliness (friendly) perception increases forgiveness (26.7pp), reintegration support (30.8pp), and the joint probability (11.6pp). Also, perceiving that ex-combatants are hard workers (hard work) increase the probability of having an optimistic belief regarding forgiveness (8.7pp) and the chance of believing in forgiveness and supporting the DDR process simultaneously (2.6pp). It does not affect, however, the reintegration support on its own. Interestingly enough, bad prejudices such as violence, laziness, and dangerousness do not drive any of the results.

The effect of parochialism is not robust nor conclusive. In Model 1, the participation bias seems to have a negative effect on forgiveness (20pp) and the joint probability (6.2pp), but it does not affect reintegration. In Model 2, the effect is insignificant for all three outcomes. Trust bias does not affect any outcome variable, regardless of the model specification.

Our results suggest that women are less likely to have optimistic views, in general. The older subjects become, seem to slightly, but significantly, increase the chances of believing in forgiveness and reintegration. Nonetheless, this effect is insignificant for reintegration support in Model 1. An additional year of education also positively impacts the DDR process support and the joint probability, while it does not affect forgiveness. The individuals’ political orientation seems to be irrelevant in this context. Finally, and consistent with Restrepo-Plaza (Citation2019), victims tend to be more supportive of the former rebels’ reintegration than non-victims in both specification models. This variable does not affect forgiveness or the joint probability.

5. Conclusions

A half-century of conflict leaves life casualties behind, and also social resentment and polarization. Restoring the social fabric relies on the possibility of addressing the underlying causes of conflict, compensating victims, and guaranteeing a peaceful reintegration of former rebels. However, emotional and social wounds might prevent the community from welcoming ex-combatants.

This paper uses the 2016-Americas-Barometer dataset to study the role of affect, prejudice, and parochialism on individuals’ beliefs regarding forgiveness to former FARC-EP members and their reintegration support. We are aware of the database limitations, as we could not consider reintegration beliefs and actual willingness to forgive. Similarly, it would have been ideal to have emotions and prejudices for the full sample (and other parochialism variables such as the cooperation bias). Nonetheless, we approach forgiveness using the survey’s question about the individual’s belief regarding the possibility of forgiving a FARC-EP ex-combatant. Reintegration is not a belief but comes from a straightforward question on the extent to which they agree with former rebels’ reintegration. We focus on these two outcomes to shed light on the FARC-EP reintegration’s social and psychological needs to succeed, building from the literature of affect, prejudice, and parochialism.

DDR processes often involve a general and symbolic apology on behalf of the group misdemeanors. Even when the non-parametric analysis exhibited partially different results, we find it a good practice once we control other variables. It raises the chances of optimistic views about forgiveness, reintegration, and both outcomes altogether (as in Voci et al. Citation2015). We find that those who feel calm and do not feel unsafe near the ex-combatants have more positive attitudes towards forgiveness and reintegration. The lesson is that interventions promoting people’s feelings of safety could reduce negative affect and improve the chances of accepting ex-combatants. As an alternative to enhancing safety using the army and in line with Unfried, Ibañez, and Restrepo-Plaza (Citation2020), inter-group contact could be enough to know ex-combatants better and let the negative affect go.

Interestingly, negative prejudices do not drive our outcome variables. A friendly and hard-working perception might be sufficient to improve the environment, facilitating ex-combatants’ reintegration. We also find a counterintuitive anxiety effect. Anxious individuals are more likely to have good vibes about forgiveness and increase the probability of forgiveness and reintegration simultaneously. This effect might be created by the subjects’ urgency for the conflict to end, even when we cannot test this hypothesis with our data.

The emergence of parochial preferences is a common finding in the literature of the behavioral consequences of exposure to conflict (Bauer et al. Citation2016). We analyze the effect of parochialism on forgiveness and reintegration and find that, when we control for emotions, the participation bias has a negative impact on both outcome variables. However, this impact turns insignificant if we control for prejudices (or when we control for neither emotions nor prejudices). This result suggests an emotional component in the participation bias, reducing the peace process’s support. The trust bias, on the other hand, does not affect the outcome variables.

Beyond age and gender, education, and victim status play a leading explanatory role in our analysis. We find that an extra year of education and having been affected by the conflict increase the chances of supporting the reintegration process (even when they do not affect forgiveness). The effect of education is also positive for the joint probability. A second policy lesson is clear. Education may increase the chances of a DDR process to succeed, as well as giving victims more room to decide.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 According to the Wilcoxon test, feelings of calm, anxiety and danger exhibit all similar results (p-value > 0.1). Safety was significantly lower than calm (p-value = 0.0005), and anxiety (p-value = 0.0026), but it was not statistically different to feeling in danger (p-value = 0.0996).

References

- Akerlof, G. A., and R. E. Kranton. 2000. “Economics and Identity.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115 (3): 715–753.

- Akerlof, G. A., and R. E. Kranton. 2005. “Identity and the Economics of Organizations.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 19 (1): 9–32.

- Annan, Jeannie, and Ana Cutter Patel. 2009. “Critical Issues and Lessons in Social Reintegration: Balancing Justice, Psychological Well Being, and Community Reconciliation.” Paper presented at the CIDDR in May 2009.

- Bauer, M., C. Blattman, J. Chytilová, J. Henrich, E. Miguel, and T. Mitts. 2016. “Can war Foster Cooperation?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30 (3): 249–274.

- Bauer, M., N. Fiala, and I. Levely. 2017. “Trusting Former Rebels: An Experimental Approach to Understanding Reintegration After Civil war.” The Economic Journal 128 (613): 1786–1819.

- Bellows, J., and E. Miguel. 2006. “War and Institutions: New Evidence from Sierra Leone.” American Economic Review 96 (2): 394–399.

- Bellows, J., and E. Miguel. 2009. “War and Local Collective Action in Sierra Leone.” Journal of Public Economics 93 (11-12): 1144–1157.

- Bicchieri, C. 2006. The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

- Blattman, C., A. Hartman, and R. Blair. 2011. “Can we Teach Peace and Conflict Resolution?: Results from a Randomized Evaluation of the Community Empowerment Program (CEP) in Liberia: A Program to Build Peace, Human Rights, and Civic Participation.” Innovations for Poverty Action.

- Bogliacino, F., C. E. Gómez, and G. Grimalda. 2019. “Crime-related Exposure to Violence and Social Preferences: Experimental Evidence from Bogotá.” Documentos FCE-CID Escuela de Economía (101).

- Castaño, G. M. 2019. “Colombia: Un Proceso de paz Irreversible Pero de Alcance Incierto.” Análisis del Real Instituto Elcano (ARI) 2 (1).

- Cecchi, F., K. Leuveld, and M. Voors. 2016. “Conflict Exposure and Competitiveness: Experimental Evidence from the Football Field in Sierra Leone.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 64 (3): 405–435.

- Exline, J. J., E. L. Worthington Jr, P. Hill, and M. E. McCullough. 2003. “Forgiveness and Justice: A Research Agenda for Social and Personality Psychology.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 7 (4): 337–348.

- Flores, M., and Price, C. W. 2018. “The Role of Attitudes and Marketing in Consumer Behaviours in the British Retail Electricity Market.” The Energy Journal 39 (4).

- Gangadharan, L., A. Islam, C. Ouch, and L. C. Wang. 2017. “The Long-Term Effects of Genocide on Social Preferences and Risk.” Unpublished Results.

- Hagmann, Lotta, and Zoe Nielsen. 2002. A Framework for Lasting DDR of Former Combatants in Crisis Situations. New York: United Nations.

- Hornsey, M. J., and M. J. Wohl. 2013. “We are Sorry: Intergroup Apologies and Their Tenuous Link with Intergroup Forgiveness.” European Review of Social Psychology 24 (1): 1–31.

- Knight, M., and A. Özerdem. 2004. “Guns, Camps and Cash: Disarmament, Demobilization and Reinsertion of Former Combatants in Transitions from war to Peace.” Journal of Peace Research 41 (4): 499–516.

- Lane, T. 2017. “Experiments on Discrimination and Social Norms.” (Doctoral dissertation). University of Nottingham.

- López-López, W., C. P. Marín, M. C. M. León, D. C. P. Garzón, and E. Mullet. 2013. “Forgiving Perpetrators of Violence: Colombian People’s Positions.” Social Indicators Research 114 (2): 287–301.

- López-López, W., G. Sandoval Alvarado, S. Rodríguez, C. Ruiz, J. D. León, C. Pineda-Marín, and E. Mullet. 2018. “Forgiving Former Perpetrators of Violence and Reintegrating Them Into Colombian Civil Society: Noncombatant Citizens’ Positions.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 24 (2): 201.

- Menezes Fonseca, A. C., F. Neto, and E. Mullet. 2012. “Dispositional Forgiveness among Homicide Offenders.” Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 23 (3): 410–416.

- Muggah, R. 2008. Security and Post-Conflict Reconstruction: Dealing with Fighters in the Aftermath of war. Routledge.

- Mukashema, I., and E. Mullet. 2013. “Unconditional Forgiveness, Reconciliation Sentiment, and Mental Health among Victims of Genocide in Rwanda.” Social Indicators Research 113 (1): 121–132.

- New York Times. 2006. “Armies of Children.” New York Times, Editorial Page, 12.

- Noor, M., N. R. Branscombe, and M. Hewstone. 2015. “When Group Members Forgive: Antecedents and Consequences”.

- Nussio, E. 2009. “¿Reincidir o no? Conceptos de la Literatura Internacional Aplicados al Caso de Desarme, Desmovilización y Reintegración de las Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia.” Pensamiento Jurídico 26: 213–236.

- Pares. 2019. “Procesos de paz en Colombia.” https://pares.com.co/2019/01/04/procesos-de-paz-en-colombia/.

- Pettigrew, T. F. 1998. “Intergroup Contact Theory.” Annual Review of Psychology 49 (1): 65–85.

- Pineda-Marín, C., M. T. Muñoz-Sastre, and E. Mullet. 2018. “Willingness to Forgive among Colombian Adults.” Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología 50 (1): 71–78.

- Restrepo-Plaza, L. 2017. “Essays in the Political Economy of Organisations: Power, Leadership and Coordination.” Doctoral dissertation, University of East Anglia.

- Restrepo-Plaza, L. M. 2019. “Cooperación con Excombatientes: el Reto Social del Posacuerdo.” Análisis Político 32 (95): 125–143.

- Rye, M. S., and K. I. Pargament. 2002. “Forgiveness and Romantic Relationships in College: Can it Heal the Wounded Heart?” Journal of Clinical Psychology 58 (4): 419–441.

- Silva, A. S., and R. Mace. 2014. “Cooperation and Conflict: Field Experiments in Northern Ireland.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281 (1792): 20141435.

- Swart, H., R. Turner, M. Hewstone, and A. Voci. 2011. Achieving Forgiveness and Trust in Postconflict Societies: The Importance of Self-Disclosure and Empathy”.

- Tam, T., M. Hewstone, E. Cairns, N. Tausch, G. Maio, and J. Kenworthy. 2007. “The Impact of Intergroup Emotions on Forgiveness in Northern Ireland.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 10 (1): 119–136.

- Unfried, K., M. Ibañez, and L. Restrepo-Plaza. 2020. “Discrimination and Inter-Group Contact in Post-Conflict Settings: Experimental Evidence from Colombia.” Working Paper.

- Villarraga, A. 2015. “Biblioteca de la paz 1980-2013 Los procesos de paz en Colombia, 1982-2014”.

- Voci, A., M. Hewstone, H. Swart, and C. A. Veneziani. 2015. “Refining the Association Between Intergroup Contact and Intergroup Forgiveness in Northern Ireland: Type of Contact, Prior Conflict Experience, and Group Identification.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 18 (5): 589–608.

- Voors, M. J., E. E. M. Nillesen, P. Verwimp, E. H. Bulte, R. Lensink, and D. P. Van Soest. 2012. “Violent Conflict and Behavior: a Field Experiment in Burundi.” The American Economic Review 102: 941–964.

- Wohl, M. J., and N. R. Branscombe. 2009. “Group Threat, Collective Angst, and Ingroup Forgiveness for the war in Iraq.” Political Psychology 30 (2): 193–217.

Appendix

Table A1. Variables.