ABSTRACT

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has become a leading contributor of foreign aid, in terms of percentage of gross national income as well as in total amount. Historically, Emirati aid was opaque, and little was known about the foreign aid portfolio. This changed after 2009 when the UAE began to submit detailed, project-level data to the Development Assistance Committee of the OECD. Based on a decade of aid transparency, this article carries out an examination of the political economy of aid provided by the UAE, comparing its portfolio to other donor countries. Particular attention is paid to analyzing three primary recipients of its aid (Egypt, Serbia and Yemen) and the implicit motivations driving those decisions. The majority of Emirati aid to these three countries was granted as general budgetary support, often in tandem with efforts to achieve political, economic and/or military aims. Based on the findings, an evaluation is made regarding Emirati narratives of South-South cooperation and its seeking of mutual benefit as well as critiques put forward within the literature countering this. In addition to critically assessing the details of an under-researched aid portfolio, this paper highlights areas for further study to deepen our understanding of the UAE’s foreign aid.

Introduction

In 2018, the Prime Minister and Vice President of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, wrote on Twitter that ‘For the fifth year running, the (OECD) named the UAE as the world’s largest Official Development Aid donor relative to national income’. The (re)emergence of states in the Arabian Peninsula acting as global donors remains under-studied (Momani and Ennis Citation2012). While aid from the region is not new (Nonneman Citation1988; Almezaini Citation2012), one of the unique, recent changes is the level of transparency of that aid. This article focuses upon one donor country, the UAE, as it was the first country in the region to submit detailed data on its aid to the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC). A second reason that the UAE warrants additional research attention is that the country has become a leading aid donor, surpassing the majority of OECD members states both in terms of the percentage of contributions based on its gross national income (GNI) and in terms of the total amount granted.

Similar to other donors, the UAE has strategic, political, economic and military motivations influencing decisions regarding aid allocation, alongside humanitarian and developmental objectives. While there are some papers that focus on country-to-country relationships and aid flows (e.g. Bartlett et al. Citation2017; Young Citation2017), to our knowledge no papers have utilized the newly available foreign aid data, which is detailed at the project level. For the UAE, such detailed data sets were first made available via the OECD DAC in 2009, and as of this writing in December 2020, were available up until 2018. Using this data, we focus upon the political economy of Emirati aid, conducting a portfolio analysis to present a macro perspective of the trends of the UAE’s foreign aid as well as to delve more specifically into country assessments to assess the primary recipients of Emirati aid in greater detail. Specifically, we analyze aid to Egypt, Serbia and Yemen, which are three countries that stand out in the aid portfolio of the UAE and warrant detailed evaluation. The macro-level analysis and country evaluations present an opportunity to examine narratives promoted by the UAE regarding its Official Development Assistance (ODA), such as that it is a leader of South-South Cooperation seeking out opportunities of mutual benefit, which is contrasted with the conditionality of aid provided by many OECD member states.

In the section that follows we first provide a brief contextualization of ODA, the OECD DAC and the UAE as a donor country, and then explain the methods we utilize in this paper. Following that contextualization, we present an assessment of the general trends of aggregate aid, as total aid flows and the GNI percentage, which we compare to OECD member states and other countries that submit ODA data to the OECD DAC. We then draw upon project level data to conduct in-depth analyses of three nations (Egypt, Serbia, Yemen), which stand out as important recipients of Emirati aid. We also make note the sources of aid from the UAE, which is granted by over twenty different agencies. We conclude with a discussion regarding what these findings mean in relation to the stated objectives and purposes of foreign aid and its practice over the last decade and how a political economy perspective of aid contributes unique insight into analyses of donors.

Context: ODA, OECD DAC and the UAE

The concept of ‘official development assistance’ (ODA) came into usage via the DAC of the OECD in 1969, as it sought to standardize and centralize the collection of aid data and play a coordinating role. Although the original definition has changed over time, ODA that is included in the DAC database has specific criteria, including the nature of the aid itself (non-repayable grants, concessional bilateral loans and the rates thereof, etc.) as well as the origin (official agencies) and the recipient (only those on the DAC list). As such, the ODA reported in the OECD DAC is a specific subset of foreign financial flows that exclude a range of financial and non-financial flows (e.g. military assistance).

As of 2020, there were 37 member states of the OECD, 34 of which report project-level data regarding ODA to the OECD DAC. In addition to these, other countries, organizations, foundations, development banks, and intergovernmental agencies can also submit their data to the OECD DAC. The UAE was the first country from the Arabian Peninsula to submit full data to the OECD DAC, which is available since 2009. Kuwait started making its data available as of 2010 and Saudi Arabia started doing so in 2015. Regarding non-state institutions that submit data, the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (based in Kuwait), which is part of the Arab League, began submitting data in 2008 and the Islamic Development Bank (based in Saudi Arabia), began submitting data in 2012. All of this newly available data provides a level of transparency regarding aid from the region that has not previously been available, which presents a range of opportunities for research of which this study is one contribution.

In the same year that the OECD DAC coined the term ‘official development assistance’, the Pearson Commission produced a report (often called the Pearson Report), which set out a target that countries should aim to contribute 0.7% of their respective GNI as aid. Many governments pledged to work toward meeting that target, which is an objective that continues to be promoted, including by the OECD (e.g. OECD Citation2020). While the figure is not a meaningful measure of aid and has not been an effective means to increase aid flows (Clemens and Moss Citation2007), it provides some longitudinal and comparative insight into donors. Of the OECD member states, only six have surpassed the 0.7% target: Turkey, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and the UK (Mitchell and Baker Citation2019). Although not a member state of the OECD, the UAE is the only other country that submits data to the OECD DAC that has surpassed the 0.7% goal, and this is what the Vice President and Prime Minister of the UAE was referring to when the country was noted as the world’s largest donor. Although the full data for 2019 is not yet available for the UAE, early aggregate data from the OECD DAC suggests that the GNI percentage for the UAE may drop below that measure (0.548%).

The UAE attracted attention in 2013 when its aid contributions increased significantly, however, well before this point scholars has identified the UAE as being a leader in the region when it comes to ODA (Momani and Ennis Citation2012). While the aid contributions of the UAE rose rapidly 2013, it has a history of ODA contributions similar to OECD members (albeit with a relatively smaller economy and thus overall contribution). Shushan and Marcoux (Citation2011) suggest that between 1995 and 1999 UAE ODA/GNI was 0.24% and that between 2000 and 2004 it was 0.26%; at or higher than the OECD average during that time period, which ranged from 0.22% to 0.25% (OECD Citation2020). Looking deeper in historical context, Villanger (Citation2007) notes that donors from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC; Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates) were historically noteworthy for their ‘outstanding generosity’, suggesting that aid from Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the UAE averaged 4.7% of GNI from 1973 to 1978 (amidst the rapid rise of oil prices) and averaged 1.5% between 1974 and 1994, far exceeding the DAC country average of 0.3%. In this regard, the UAE as a donor is not new, nor is the level of contribution relative to its GNI.

In addition to the provision of ODA, the UAE has made strategic investments to advance its leadership role in the humanitarian and development sector, such as establishing the International Humanitarian City in 2003, which it reports as being the largest humanitarian hub in the world (IHA Citation2020). Via these initiatives, the UAE has been working to position itself, and its role as a donor, as a country acting in solidarity with fellow nations in the Global South and being a leader in South-South Cooperation (Almezaini Citation2018). This agenda has been promoted by the UAE in a range of ways, such as acting as the 2012 host of the G77 South-South High Level Conference on Science and Technology and the 2016 host of the Global South-South Development Expo, the latter being an annual event held by the United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation. The narrative of South-South collaboration is one rooted in mutual benefit and solidarity, and is made in contrast to other forms of donor imposition and donor conditionality. For some scholars, the UAE’s approach to aid challenges ‘the logic and conditionality of foreign aid’ that has been common practice by Western donors for decades, including the introduction of new modalities of aid, such as ‘non-restricted cash grants, injections to central banks, and in-kind oil and gas deliveries’ (Young Citation2017, 114). This sentiment is echoed by other scholars, such as Momani and Ennis (Citation2012) and Villanger (Citation2007).

Alongside the narrative of doing aid differently, the UAE has been actively working to present itself as a ‘role model’, as described by Pinto (Citation2014), of which its South-South partnership approach could be considered one component of. As a nation that has transformed itself into a relatively diversified and successful economy through state-led capitalism (particularly in relation to other GCC nations that also benefited from natural resource rents), the UAE presents itself as a political and governance model for others to follow, offering another counter narrative to direction and advice provided by Western donors (Young Citation2017). The UAE does so, however, while participating as a partner in international agendas, such as framing its overarching objectives as contributing to the Millennium Development Goals and Sustainable Development Goals, as described by Almatrooshi (Citation2019), a member of the UAE’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

As a counter to the positive narratives being promoted by the government and its partners, many researchers have put forward critical assessments of the intentions, justifications and uses of aid by the UAE. For example, Shushan and Marcoux (Citation2011, 1973) suggest that Arab states ‘have something to hide’, which explains the lack of transparency in their foreign aid. Villanger (Citation2007, 250) highlights a religious motivation, suggesting ‘Arab aid’ may have been granted to Sudan as a means of ‘imposing Shari’ah’ on people who are not Muslim. The granting of aid by GCC member states and their commitment to ODA is explicitly linked to oil, their supposed real intentions being clouded in ulterior motives, potentially of self-aggrandizement and profiteering (Shushan and Marcoux Citation2011). As with other claims about governments in the Middle East, accusations are often based on assumptions and have been shown to be incorrect (e.g. Smith Citation2011; Young Citation2017). In this regard, orientalist stereotypes appear to continue to influence the discourse. During this same time period, the ‘Arab cowboys’ were accused of unjustly ‘grabbing up land’ across Africa and Asia (Farrar Citation2014), narratives that turned out to be exaggerated or false (Cochrane and Amery Citation2017). All of this reminds us of the need for on-going critique, contestation and counter-narrative as stereotypes and racism continue to bias the way people and governments are depicted (Said Citation1978). That having been said, as is typical of ODA more generally, the UAE’s foreign aid choices are influenced by strategic, political, economic, military and humanitarian motivations, thus demanding perspectives on the political economy of its aid.

Methods

Given the size of the ODA portfolio of the UAE, and that detailed data of its official foreign aid has been available since 2009, the paucity of literature on it is surprising. As far as we are aware, other than non-academic reports, very little research is available. For example, on the academic search platform Web of Science combinations of search keywords of ‘ODA’, ‘Official Development Assistance’ and ‘Foreign Aid’ with UAE result in only four articles. Searches on Google Scholar, which include a much broader set of materials (e.g. theses, chapters, reports, journals not indexed by the Web of Science), results in 27 additional publications, which is still limited given the role the country has played as a donor. As far as we are aware, no detailed studies have been conducted that analyze the project-level trends of the foreign aid of the UAE (using available, verified OECD DAC data, from 2009 to present). Scholars have looked at specific recipient country partnerships (e.g. Bartlett et al. Citation2017; Young Citation2017) and have explored trends at the GCC level (Carroll and Hynes Citation2013; Momani and Ennis Citation2012; Neumayer Citation2003, Citation2004; Shushan and Marcoux Citation2011; Villanger Citation2007), the latter often resulting in brief descriptive surveys. These regional surveys, while insightful, do not provide the detailed analysis that is attempted in this paper. The works of Almezaini (Citation2012, Citation2017, Citation2018) and Almatrooshi (Citation2019) stand out as offering detailed specific analyses for the UAE, upon which this study builds and expands. Almezaini largely focuses upon the period prior to 2009, this paper focuses on the time period that follows.

For this study, we rely on two main sources of evidence. The first is the OECD DAC database, where OECD member states submit annual, project-level ODA data, which is available publicly. Non-OECD members can also submit their data and have it made available in the OECD DAC database, which the UAE has done. We analyze that data in several ways: (1) using country data, we compare the OECD member states average (those member states that report ODA to the DAC) to the UAE from 2009 to 2018, in order to contextualize the trends of foreign aid and where the UAE sits in relation to other donors; (2) using country data, we compare the percentage of GNI given to ODA by the DAC member states, including the UAE, from 2009 to 2018, based on all available data; (3) using project level data, we analyze the recipients of the UAE’s foreign aid from 2009 to 2018, based on all available data; and (4) using project level data, we analyze the complex domestic donor environment within the UAE, by outlining which domestic donors have been key actors in the foreign aid portfolio. We also draw upon available secondary literature to conduct an analysis of the findings (the 31 publications noted above), rooted in a political economy approach (as opposed to analyzing effectiveness or a host of other perspectives that might be used to assess the foreign aid portfolio), and present a detailed analyses of three recipient countries (Egypt, Serbia, Yemen).

While we have utilized all available data sources that we are aware of, the material itself presents some limitations. First, there is a time period limitation. The UAE has been a donor for decades, but we only have project-level data from 2009 onward, and at the time of writing (November and December of 2020) the most recent complete year of data in the OECD DAC database is 2018, resulting in ten years of project-level data. This limitation obscures several things. It means we cannot cover the period of time in the 1970s when the UAE (and other GCC countries) had GNI contributions at very high levels (manifold higher than what we see in the recent decade). It also means that we are unable to present a detailed analyses of the decline and rise of aid in the decades that preceded the period for which we have data. Several studies are available that attempt to trace these historical trends, from the 1970s onward, however, these are high-level (country data, not project-level) and have to grapple with a wide range of data limitation challenges. We make reference to these works, but do not attempt a re-analysis of those trends or those periods of time. The availability of data via the OECD DAC from 2009 presents an opportunity for detailed analysis, which is what we have focused upon in this paper. Almezaini’s book (Citation2012) presents a detailed historical perspective of the UAE’s foreign aid up until 2008, which is where we begin. For additional historical context, readers can refer to that work. Second, this article analyzes the ODA of the UAE, as reported to the OECD DAC. We do not, in this work, present a critical analyses of government policies, their history, or their development over time. Additional studies are required to complement this work to address those critical knowledge gaps, which may shed further insight into the political economy of aid, particularly regarding the deeper history of the UAE’s foreign aid and thereby its motivations and objectives.

The UAE as a global donor

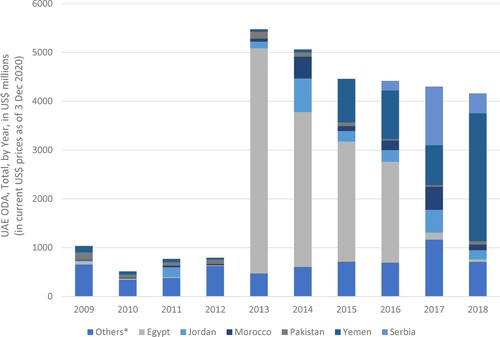

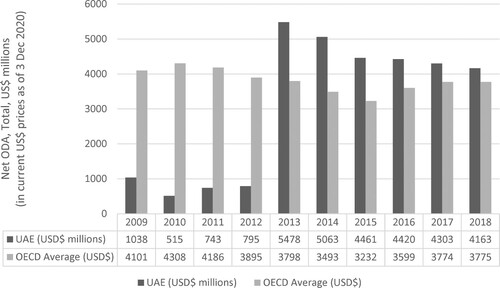

In terms of total aid granted, in 2018 the largest donor countries were the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, Japan and France. The aggregate aid flows are relative to their economy size, with only the UK of that list surpassing the 0.7% of GNI objective. In total ODA granted during 2018 in US$ value, the UAE was the 18th largest donor (of those countries submitting data, notably China is not in the OECD DAC database). However, a more meaningful measure that is less relative to economy size is comparing the total aid contributions of the UAE in comparison to the OECD average. As shown in , the OECD average ranged between US$3.2 billion and US$4.3 billion during the 2009–2018 time period. Following 2013, the UAE has had a higher ODA than the average of the OECD donors. The rise of ODA in 2013 counters some narratives suggesting that ODA from the GCC member states, including the UAE, was on the decline (e.g. Shushan and Marcoux Citation2011).

Figure 1. Total ODA US$ by year, OECD average and UAE (in current US$ prices as of 3 December 2020).

For the UAE, 2013 stands out as a marked change in its ODA contributions, with the ODA increasing by nearly 600% in US$ value. After 2013, Emirati ODA declined each year, and it appears that this declining trend will continue into 2019 (all figures are in current US$ prices, as of 3 December 2020 and comparisons should take this into account). While the government of the UAE suggested that the significant increase of foreign aid in 2013 was the UAE fulfilling its commitment to the Millennium Development Goals (MICAD Citation2014), others have suggested that this was an effort to stop the spreading unrest resulting from the Arab Spring (e.g. al-Anani Citation2020). We find, as Gokalp (Citation2020) does, that the portfolio suggests a more nuanced use of foreign aid. Consider the case of Egypt: As is explored in the country analyses below, Emirati aid was minimal at the beginning of revolution in 2011 and also minimal after the 2012 elections, however, following the military coup the UAE stepped in, significantly. This aid supported the military government that ousted the elected government led by Mohammed Morsi and the Freedom and Justice Party. The role of Egypt in 2013 is significant: in 2013 the UAE’s ODA portfolio increased by US$4.6 billion, during which year Egypt received US$4.6 billion from the UAE in ODA (previous to which Egypt was a minor ODA recipient). Parts of the portfolio, such as in Egypt and Yemen, suggest that rather than being responsive to unrest per se, the UAE acted upon specific windows of opportunity to stabilize ideologically allied governments.

There are limitations to comparing averages (e.g. it includes the major donors, such as the United States, and relatively minor donors, such as Estonia and Latvia), however, this provides some perspective. One can also compare economies of similar size to that of the UAE; for example, the UAE’s ODA has been similar in amount to Canada, but has an economy that is around four times smaller (by GDP); Austria has a similar size of economy (in terms of GDP), being slightly larger than the UAE, but in recent years the ODA of the UAE is 3–4 times higher in aggregate dollar values (as shown by the GNI% in ; World Bank Citation2020). For comparative purposes, using the percentage of GNI granted to ODA amongst OECD DAC submitting countries provides a more useful comparative measure.

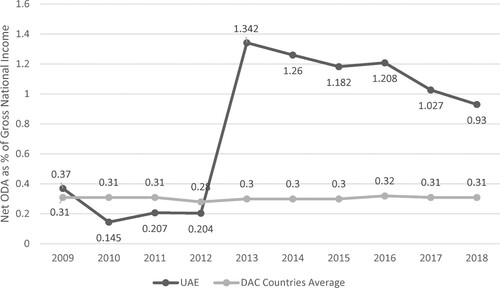

Figure 2. Total ODA as % of GNI, DAC average and UAE (OECD Citation2020).

In 2018, the UAE had the fifth highest percentage of GNI granted to ODA (following Turkey, Sweden, Luxembourg and Norway). The average for the OECD DAC is relatively stable around 0.3%. As expected from the aggregate US$ granted to ODA shown in , the percentage of GNI granted to ODA for the UAE increases substantially in 2013 (), rising to levels much higher the OECD DAC average. It was during these years after 2013 that the UAE made headlines as the most generous country, in terms of aid given relative to their economy size. While the GNI percentage has declined steadily (and early indications suggest this decline will continue into 2019), the rate remains well above the OECD DAC average.

Before the availability of project level data from the OECD DAC, Neumayer (Citation2003, Citation2004) argued that ODA from Arab states tended to be granted to other Arab states and was less targeted toward the least developed nations. Villanger (Citation2007) suggested the ODA focus was upon Islamic countries. More recent research, such as that by Shushan and Marcoux (Citation2011) and Young (Citation2017), have shown that the UAE’s focus on Arab or Muslim states, if that was once the case, has not continued (data on ODA is particularly problematic previous to the UAE submitting project-level data to the OECD as of 2009 to say much with certainty before this period). Without disputing the findings of Shushan and Marcoux (Citation2011) and Young (Citation2017), in the 2009–2018 period of study in this research, of the six largest recipients of UAE ODA, five are Muslim majority countries (only Serbia is not, which emerged as a primary recipient in recent years). That these states are Muslim-majority, however, ought not be equated with that being a condition or objective. Another explanation is geographic proximity; of the primary recipients, four nations are geographically amongst those nearest to the UAE that are in need of ODA and are on the DAC list (Jordan, Egypt, Pakistan and Yemen), each having strong ties to the UAE (as we discuss in more detail below).

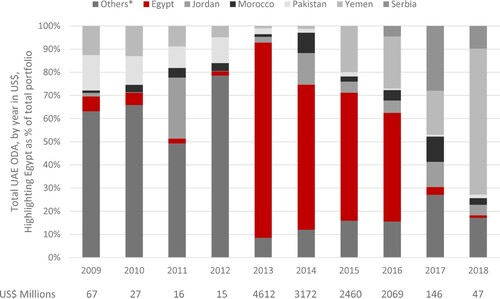

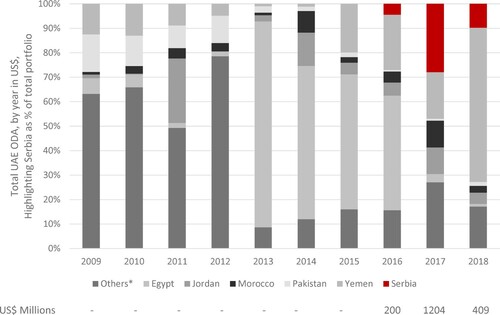

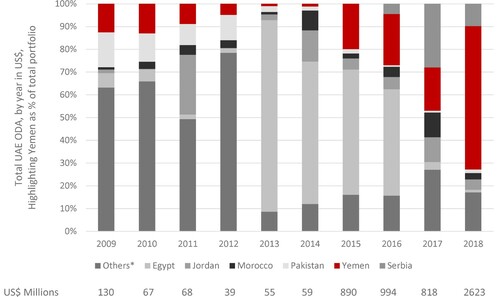

In analyzing the early decades of UAE foreign aid, Almezaini finds that the identities of Arab and Muslim were important factors for the UAE, but he also shows how these priorities have changed over time, particularly in the most recent two decades, suggesting that the largest recipients of UAE aid were in Asia and Africa, not in other Arab states (Almezaini Citation2012, Citation2017, Citation2018). By analyzing project-level data for 2009–2018, Africa is a primary destination of Emirati ODA, but primarily that goes to North African, Arab and Muslim-majority states (Egypt and Morocco). Amongst the other main destinations for Emirati ODA, Jordan, Pakistan, Serbia and Yemen stand out (see ). Based on this country breakdown of the portfolio (), we identify three recipients as accounting for the major ODA changes in the UAE: contributions made to Egypt, Serbia and Yemen, which we analyze respectively in sub-sections below.

Scholars have proposed moments of transformation for the orientation of Emirati foreign aid. Alzaabi (Citation2019) suggests the most suitable division is the Zayed (1971–2004) and post-Zayed (2004–present) eras. During the Zayed era, decisions were rooted in Arab and Muslim solidarity. Others, such as Almezaini (Citation2017), Ragab (Citation2017) and Soubrier (Citation2017), suggest that the uprisings of 2011–2012 better explain the re-orientations seen in the portfolio (size and recipients), largely transitioning from identity-based to strategic foreign aid. Building upon the latter of these theories, following the Arab Uprisings of 2011–2012, the UAE has been actively involved in a range of countries, utilizing military, economic and foreign aid to shape outcomes. This can be seen in Libya, Syria and Yemen, while foreign aid has been primary in furthering the UAE’s objectives in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Yemen (Ziadah Citation2019). Some scholars (e.g. Almezaini Citation2017; Soubrier Citation2017) identify this as a key turning point in the broader foreign policy of the UAE, including its foreign aid. Following the mass movements throughout the Middle East and North Africa, the UAE more actively utilized combinations of military, economy and assistance engagements to shape alliances in line with its priorities. The aid relationship the UAE has with Egypt and Yemen presents an example of one of its foreign policy instruments advancing strategic and political aims, while its relationships in the Balkans reflect economic and objectives.

Table 1. Diversity of ‘others’ in UAE foreign aid portfolio (excluding the 6 major recipients), totala.

Previous to 2013, the ‘others’ category (meaning all other nations excepting the 6 identified in ) was a diverse and a focal component of the UAE’s aid portfolio (). Aid in this ‘other’ category flowed to between 70 (2009) and 111 (2016 and 2017) countries, ranging from US$339 million (2010) to US$1.1 billion (2017). UAE aid before 2013 could be described as a diverse, global portfolio that did not prioritize any specific recipient country. There are consistent recipients of Emirati ODA throughout all of the years of study, including Afghanistan, Palestine, Somalia, Sudan and Syria, albeit in relatively lower terms. Afghanistan exceeded 10% of the ODA portfolio in one year (2012 at $97 million), which was the highest total amount of foreign aid given to the country in the time period. Palestine received a significant percentage of the portfolio in 2009 ($230 million) and 2010 ($87 million). There are also some notable changes within the portfolio. For example, Oman was a recipient of significant aid in 2009 ($127 million), but thereafter dropped ($12 million in 2010) and then stopped altogether (notably, in 2009, nearly all the budget was granted to road transport, $95 million). Similarly, Kazakhstan received significant aid flows in 2009 ($22 million), 2010 ($11 million) and 2011 ($80 million), but thereafter received minor amounts. Iraq, on the other hand, was a minor aid recipient until 2015 ($100 million), 2016 ($74 million) and 2017 ($390 million). Regarding how these funds flow from donor to recipient, Villanger (Citation2007) suggests that ‘Arab aid’ (Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, UAE) is mainly dispersed through bilateral forms, with low levels of contributions to multilateral institutions. The data suggests that this continues to be the case for the UAE.

Aid is a political act. The decisions of the UAE regarding how to use its foreign aid, to whom it is granted, for what purposes, in what areas of the world, in which priority areas, all reflect this reality (Almezaini Citation2012). That is not to suggest that there is no humanitarian motive in foreign aid, undoubtedly we could point to examples where the UAE has responded to humanitarian crises in benevolent ways. However, this analysis seeks to critically analyze the portfolio of foreign aid, and specifically the primary recipients of it, using a political economy perspective. Of the aid portfolio, Egypt, Yemen and Serbia stand out as unique. We explore why that is the case, and what can be learned about foreign aid from the UAE based upon that. In effect, we want to investigate why the drivers for these decisions.

Egypt

While some scholars have suggested that the 2011 and 2012 uprisings across North Africa and the Middle East sparked a change in foreign policy in the region (e.g. Almezaini Citation2017; Ragab Citation2017; Soubrier Citation2017), the case of Egypt shows that the Emirati shifts were indeed responsive, but not to mass protests per se. In the years preceding 2013, Egypt received low levels of ODA from the UAE. It was during this period that the Egyptian revolution took place (2011), which resulted in a decline of UAE ODA. In the following year, 2012, when Mohammed Morsi was elected and the Freedom and Justice Party led the nation, UAE ODA remained minimal. However, when the military coup d’etat occurred in 2013 the UAE provided massive amounts of ODA to the Egyptian government. Of the US$4.6 billion granted to Egypt in 2013, US$3 billion was direct budgetary support (to the Central Bank of Egypt with US$2 billion as a loan and US$1 billion as a grant, both granted by the Abu Dhabi Department of Finance), US$957 million was sector budgetary support (a grant to cover petroleum needs, also from the Abu Dhabi Department of Finance), and US$503 million for the construction of housing (also a grant from the Abu Dhabi Department of Finance). The remainder of the ODA provided to Egypt by the UAE were 14 smaller contributions (contributions all under US$50 million). Between 2013 and 2016 the UAE provided US$12.3 billion in ODA to Egypt. In addition, within the ‘Other Official Flows’ (OOF) transfers, the UAE provided an additional US$3.8 billion in 2015 to Egypt (also granted by the Abu Dhabi Department of Finance). Together, these reported financial flows exceed US$16.1 billion within a four-year period.Footnote1 In other words, the UAE made a significant intervention to support the military government in Egypt, using its ODA to stabilize the government and its finances as well as enable it to provide basic services for the population ().

Figure 4. Total UAE ODA, by year in US$, highlighting Egypt as % of total portfolio (in current prices as of 3 December 2020).

Young (Citation2017) analyzed the relationship between the UAE and Egypt, which included these high levels of ODA, as well as other forms of partnership, namely political, military and economic. Young (Citation2017) frames the ODA objectives in Egypt as ones that are inherently political (promoting a vision of state-led capitalism and secular governance) as well as economic (facilitating investment). This aligns with the ‘role model’ motivations that the UAE advocates, and implicitly this can be seen from a policy perspective as the UAE viewed the military government as more allied with its interests than two governments that came before it. The outcomes of the military transition may have taken a much different course had the UAE not injected billions of dollars into the government and central bank. In this way, the UAE becomes much more than a partner with the provision of aid, but a critical financer to ensure the viability of the new military government, thereby giving it significant strategic, political and economic influence. This soft power aligns with the UAE’s stance against the Muslim Brotherhood, and political Islam more broadly (Ibish Citation2017). While there is no conditionality, the forms of ODA undertaken by the UAE in its partnership in Egypt, Young (Citation2017) suggests, are such that they are flexibly designed so that course changes can be made if political priorities are not met. One might envision these as implicit conditionalities, as opposed to explicit, contractual conditionalities.

Serbia

As a country that is not geographically near to the UAE nor one that has historical or cultural ties to the country, Serbia stands out as an unexpected primary recipient of ODA. The data in the OECD DAC suggests that US$1.8 billion was provided over a three-year period (2016–2018). However, the partnership began much earlier. On 27 March 2013, it was reported that the UAE granted a US$400 million loan to Serbia, which was to be used to support the agricultural sector, a loan that was granted following an Emirati firm having had invested in 9,000 hectares of agricultural land (Barnard Citation2014). Shortly thereafter, the Serbian government granted approval for the UAE to become a partner in the national airline, and on 1 August 2013, the national airline of the UAE (Etihad) obtained a 49% stake in the Serbian national airline and was granted a five-year contract to manage it (Vasovic Citation2013). The agreement required both Etihad and the Government of Serbia to provide US$100 million of funding for the project. In the following year, 2014, the Government of Serbia began a multi-billion dollar renewal project of the Belgrade waterfront, which the Emirati firm Eagle Hills later announced that it was financing (the company is run by Mohamed Alabbar, one of the most important and influential businesspeople in the Emirates). Also in 2014, the UAE granted another loan to Serbia, reported to be US$1 billion (Barnard Citation2014). There are also reports that as early as 2014 Emirati companies had made multi-hundred-million-dollar investments into the Serbian arms industry (e.g. Donaghy Citation2015).

The loans that occurred in 2013 and 2014, although reported as concessionary, do not appear in the OECD DAC. In addition to reporting ODA data, countries also submit data on ‘Other Official Flows’ (OOF) of funding, which may not be eligible for ODA (e.g. certain types of loans). This could potentially be a place where some of the missing financial flows could be identified. The OOF dataset is not as complete as that of ODA. For example, the largest financial flow reported in 2014 is for US$500 million, granted by the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development, but the data does not specify the recipient of this bilateral non-export credit. The reported US$1 billion loan from 2014 does not appear in the 2014 or 2015 OOF data. However, there are financial flows of OOF for US$500 million in 2016 and US$1.3 billion in 2018 that were granted from the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development (funding to Egypt was granted by the Abu Dhabi Department of Finance, while funding to the government of Yemen was granted by the unspecified ‘other government entities’), which is suggestive but speculative of Serbia being the beneficiary country of this bilateral non-export credit. In either scenario, based on reports by the two governments, the relationship between Serbia and the UAE is longer-running and more financially involved than the ODA data suggests ().

Figure 5. Total UAE ODA, by year in US$, highlighting Serbia as % of total portfolio (in current prices as of 3 December 2020).

The first appearance of the reported US$1.8 billion of Emirati ODA granted to Serbia during that three-year period appears in 2016, with a US$200 million loan to the government, followed by loans in 2017 of US$1 billion and in 2018 of US$398 million. All three loans (the bulk of the ODA granted by the UAE) were provided by the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development. Research by Bartlett et al. (Citation2017) explores the relationship that the UAE has developed with Serbia. Although Bartlett et al. (Citation2017) focus upon commercial investments, it is clear that the economic interests are influencing the aid decisions. In their commercial and investment activities, Emiratis have focused their efforts in four sectors (aviation, construction, military technology, agriculture), which respectively develop areas of mutual interest. This builds upon the narrative of South-South cooperation that the UAE is promoting. However, it has also been suggested that Serbia is not only a place where there are good investments and a friendly government, it also happens to be strategically located to counter the expanding interests and influence of Turkey (Karcic Citation2020). If accurate, this motivation would add political and ideological interests to the choice of Serbia as a key partner for the UAE.

Yemen

The people of Yemen are in the greatest need for ODA in the immediate geographic proximity of the UAE. The United Nations lists Yemen as one of the ‘Least Developed Countries’, wherein nearly half of the population lives in multidimensional poverty (UNDP Citation2020). Of the total US$5.7 billion granted in ODA between 2009 and 2018, however, only US$418 million (7%) was granted between 2009 and 2014, and during those years Yemen was not a primary beneficiary of ODA in comparison to other recipient countries. Yemen became focal in 2015, the same year in which the UAE joined a coalition seeking to reinstate President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi and retake territory that had been lost to the Houthi movement. While much has been written on the conflict, including UAE’s role within it (e.g. Ardemagni Citation2016; Hokayem and Roberts Citation2016; Juneau Citation2020), little has been written on the role of ODA ().

Figure 6. Total UAE ODA, by year in US$, highlighting Yemen as % of total portfolio (in current prices as of 3 December 2020).

Focusing upon the post-2015 period, the type of ODA granted to Yemen reflects the support that was provided to both Egypt and Serbia; the majority of the financial flows are accounted for by a few, large budgetary support grants and loans. In each of the years between 2015 and 2018 many ODA disbursements were made, and the number of disbursements increased with each passing year (96 in 2015, 112 in 2016, 145 in 2017, and 252 in 2018). However, of the US$5.3 billion granted in ODA during those years, half was granted in a limited number of large transfers of budgetary support. In 2015, this accounted for US$150 million, which increased in 2016 to US$531 million and increased again in 2017 to US$557 million. The largest budgetary support was provided in 2018, with US$1.3 billion provided. Notably, all of these large disbursements that were granted as general budgetary support (totaling US$2.5 billion) were provided by ‘other government entities’. This differs from the government grants and loans made to Egypt (granted by the Abu Dhabi Department of Finance) and Serbia (granted by the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development). It remains unclear which entity granted these large sums. Also different than Egypt and Serbia, all of these funds were grants, not concessional loans.

Similar to the Egyptian case, the change of course of Emirati ODA aligns with political changes. During the years when Yemen was governed by the Abdullah Saleh government, levels of poverty were high and ODA from the UAE was an important part of the portfolio, accounting for approximately 10%. In alignment with the ending of the Abdullah Saleh government in 2011, ODA from the UAE also fell, and remained minimal until the Saudi-led coalition entered the Yemen conflict in 2015. As in the Egyptian case, the large direct budgetary support provided during these years provided more than stability, the UAE (and other coalition partners) obtained other forms of influence. After the largest Emirati ODA contributions, in 2018, wherein arguably non-military influence was bolstered to its highest level, the UAE prepared a military withdrawal, officially doing so in 2019. Unlike Serbia, and to an extent Egypt, ODA from the UAE in Yemen also provided humanitarian aid, which supported a population that was on the brink of famine. This humanitarian engagement, however, must be viewed alongside the military impact, as the escalation of the conflict by the coalition and its direct military involvement undoubtedly contributed to the dire humanitarian crisis.

Domestic donor landscape

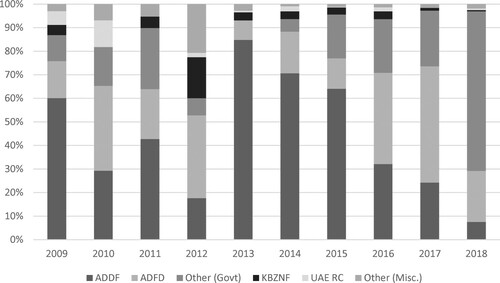

The three cases of Egypt, Serbia and Yemen raise an interesting question about Emirati ODA: who grants it? For Egypt the financial flows came from the Abu Dhabi Department of Finance, for Serbia, the financial flows came from the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development, and for Yemen the undisclosed ‘other government entities’ provided nearly half of all the funding. Unlike some donor governments, ODA from the UAE does not flow primarily through a single agency. Smith (Citation2011) suggests that before the UAE starting submitted data to the OECD DAC there were more than 20 agencies providing foreign aid. To coordinate and track foreign aid, the UAE Office for the Coordination of Foreign Aid (OCFA) was established, in 2008, by the Federal Cabinet. It is the OCFA that aggregates data and reports to the OECD in the same form used by OECD member states. To further support this work, the UAE established the Office for Coordination of Foreign Aid in 2010. The data reported to the OECD DAC does not list as large a set of donors as suggested by Smith (Citation2011), analyzing all the donors between 2009 and 2018 there are 12 donors listed.

One of the first donor institutions established was the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development, which was founded in 1971. This agency is suggested to have accounted for a relatively small amount of the overall portfolio historically; Villanger (Citation2007) posits that this ranged between 10% and 15% in the first decades of operation. For the period of study in this article (2009–2018), the largest domestic donor agencies in the UAE were the Abu Dhabi Department of Finance (ADDF) and the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development (ADFD), which together accounted for more half of the overall foreign aid spending in all years except 2018 (see ). However, a range of other donor institutions exists, including the UAE Red Crescent Authority (UAE RC), Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan Charitable and Humanitarian Foundation (ZBSNCHF), Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Humanitarian and Charity Establishment (MBRMHCR), Mohamed Bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, Khalifa Bin Zayed Al Nahyan Foundation (KBZNF), the International Humanitarian City (IHC), amongst others. Addition research is required to better assess each of these domestic donor organizations and their respective priorities and practices.

Figure 7. UAE sub-national agencies (as reported in OECD data set)* (The ‘Other (Misc.)’ category includes smaller budget lines from Noor Dubai (only in 2009 and 2011), minor budget lines from the Al Maktoum Foundation (2009–2013) and minor budget lines from Mohamed Bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund (2014–2017) and the Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan Charitable and Humanitarian Foundation, in relatively small amounts).

Discussion

Having analyzed the portfolio and project level data, it is possible to re-visit some of the claims made by scholars on Emirati ODA. Several of the accusations made about the UAE are rooted in its lack of transparency that existed before 2009 (e.g. Shushan and Marcoux Citation2011). This is no longer the case, nor is it the case for other countries and intergovernmental granting agencies in the region. With data now in hand, the only indications that the UAE might have ‘something to hide’ are the unspecified ‘other government entities’, the funds provided from which were particularly large in Yemen. Other than this, the details for which are reported in detail, in most years nearly all of the aid is fully accounted for. ‘Unspecified bilateral’ foreign aid was listed for each year, however, this tended to be less than 5% of the portfolio, with the exception of 2012, when it amounted to nearly 20% of the portfolio (note: in , this category was merged with the ‘Other’ category for the ease of readability). This might suggest that if the UAE once had something to hide, as some scholars have suggested, that is no longer the case. However, the contextual analysis of Serbia suggests that not all foreign financial flows are being reported (either as ODA or as OOF). Does this indicate there is ‘something to hide’? Not necessarily, particularly given the thousands of lines of data that has been submitted to the OECD DAC and that is available to the public. It does, nonetheless, raise questions.

Neumayer (Citation2004) and Shushan and Marcoux (Citation2011) have suggested that Arab states grant ODA with different priorities than what is typical for OECD member states; prioritizing infrastructure and investments that are aimed to ‘promote general economic growth’ (Shushan and Marcoux Citation2011, 1977) without strict conditionalities. Almezaini (Citation2018) presents this slightly differently (although not necessarily in disagreement), in arguing that the foreign aid portfolio of the UAE is in alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals, having specializations amongst the SDGs, as other OECD member states. Analyzing the project type, as per OECD DAC classifications, the UAE does not appear to prioritize infrastructure or economic growth, instead focusing on general budgetary support, basic services, social protection and humanitarian relief. What is unique amongst these ODA flows is the emphasis placed on general budgetary support, which arguably is much more aligned with the 2005 Paris Declaration and the 2008 Accra Agenda than its OECD member state counterparts because it allows a greater ability for governments to determine what needs to be prioritized. As argued by Almezaini (Citation2017), the UAE doers appear to be more willing to try different approaches to ODA, rather than simply replicate other donor models. Similar to other donors, however, it is clear that Emirati ODA is not only pursuing humanitarian and developmental aims, it is influenced by strategic, political, economic and military objectives. These other objectives – as shown in Egypt, Serbia and Yemen – challenge the narratives of South-South cooperation seeking mutual benefit, or at least contest with whom that benefit is being shared.

All of the data presented in this article says nothing about the effectiveness or impact of Emirati ODA. Much more research is required to assess and evaluate these activities to speak to those aspects. Until 2009, monitoring, evaluation and reporting of ODA was weak (Villanger Citation2007). Young (Citation2017) questions the effectiveness of GCC foreign aid, albeit using general lessons of aid, not based upon evaluation data specific to these donors. What is clear, however, is that one of the next frontiers for advancing our collective understanding of UAE ODA is conducting more rigorous evaluations of it.

Conclusion

Official development assistance from the UAE is significant in aggregated amount and as a percentage of GNI. Its contributions are higher than most OECD member states, and are higher than the average of the OECD DAC. Contrary to what some have suggested, we do not find evidence that the Emirati aid portfolio is biased toward identity or faith per se, but instead that aid flows to the largest recipients are aligned with ideological, political, economic and military aims. Analyzing three primary recipients (Egypt, Serbia and Yemen) shows that Emirati aid is unique in that general budgetary support is a key component of its aid, both as grants and as concessional loans. Yet, the largest interventions did not occur in response to humanitarian or developmental demands primarily, but rather responded to economic or political partnerships as well as military engagements that enabled the UAE to strengthen its collaboration with allied governments. While this research has provided insight into the Emirati aid portfolio and analyzed project level data, it does not assess the effectiveness or impact of such aid, which is an area that requires future research attention.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The OOF data reports another US$1.3 billion in unspecified bilateral OOF during this same four-year time period, US$334 million of which was provided by the Abu Dhabi Department of Finance, which provided all other funding to Egypt, which is suggestive of Egypt as a beneficiary but is speculative (whereas funding to Serbia was provided by the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development, which provided the other US$1 billion of unspecified bilateral OOF, suggesting it may have been granted to Serbia).

References

- al-Anani, K. 2020. “Warning to All Tyrants: The Arab Spring Lives On.” Accessed January 18 2021. https://www.middleeasteye.net/big-story/arab-spring-still-a-warning-all-tyrants.

- Almatrooshi, B. 2019. “The UAE’s Foreign Assistance Policy and its Contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals.” Open Journal of Political Science 9: 669–686.

- Almezaini, K. 2012. The UAE and Foreign Policy: Foreign Aid, Identifies and Interests. New York: Routledge.

- Almezaini, K. 2017. “From Identities to Politics: UAE Foreign Aid.” In South-South Cooperation Beyond the Myths: Rising Donors, New Aid Practices? edited by I. Bergamaschi, P. Moore, and A. B. Tickner (Chapter 9, 225–244). London: Palgrave.

- Almezaini, K. 2018. “Implementing Global Strategy in the UAE Foreign Aid: From Arab Solidarity to South-South Cooperation.” International Relations 18 (3): 579–594.

- Alzaabi, M. 2019. “Foreign Policy of the United Arab Emirates (UAE): Continuity and Change.” In Smart Technologies and Innovation for a Sustainable Future, Proceedings of the 1st American University in the Emirates International Research Conference, Dubai, 2017, edited by A. Al-Masri and K. Curran, 141–148. Cham: Springer.

- Ardemagni, E. 2016. “UAE’s Military Priorities in Yemen: Counterterrorism and the South.” ISPI-Italian Institute for International Political Studies 28, 1–3.

- Barnard, L. 2014. “Abu Dhabi Signs 1bn Loan Agreement with Serbia.” Accessed December 12 2020. https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/abu-dhabi-signs-1bn-loan-agreement-with-serbia-1.595006.

- Bartlett, W., J. Ker-Lindsay, K. Alexander, and T. Prelec. 2017. “The UAE as an Emerging Actor in the Western Balkans: The Case of Strategic Investment in Serbia.” Journal of Arabian Studies 7: 94–112.

- Carroll, P., and W. Hynes. 2013. “Engaging with Arab Donors: The DAC Experience.” IIIS Discussion Paper No 424. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2267136.

- Clemens, M. A., and T. J. Moss. 2007. “The Ghost of 0.7 Per cent: Origins and Relevance of the International Aid Target.” International Journal of Development Issues 6 (1): 3–25.

- Cochrane, L., and H. Amery. 2017. “Gulf Cooperation Council Countries and the Global Land Grab.” Arab World Geographer 20 (1): 17–41.

- Donaghy, R. 2015. “The UAE’s Shadowy Dealings with Serbia.” Accessed December 12 2020. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/uaes-shadowy-dealings-serbia.

- Farrar, S. 2014. “Arab Acquisitions in Sub-Saharan Africa: Partners in Development?” Law and Development Review 7 (2): 243–273.

- Gokalp, D. 2020. “The UAE’s Humanitarian Diplomacy: Claiming State Sovereignty, Regional Leverage and International Recognition.” CMI Working Paper 1: 1–11.

- Hokayem, E., and D. B. Roberts. 2016. “The War in Yemen.” Survival 58 (6): 157–186.

- Ibish, H. 2017. “The UAE’s Evolving National Security Strategy.” Issue Paper #4. Washington, DC: Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington.

- IHA. 2020. “International Humanitarian City – About IHC.” Accessed December 12 2020. https://www.ihc.ae/ihc-at-a-glance/.

- Juneau, T. 2020. “The UAE and the War in Yemen: From Surge to Recalibration.” Survival 62 (4): 183–208.

- Karcic, H. 2020. “Is the UAE Competing Against Turkey in the Balkans?” Accessed December 12 2020. https://research.sharqforum.org/2020/06/05/is-the-uae-competing-against-turkey-in-the-balkans/.

- MICAD. 2014. “United Arab Emirates Foreign Aid 2013.” Abu Dhabi: Ministry of International Cooperation and Development (MICAD).

- Mitchell, I., and A. Baker. 2019. Financing Development: A “Common but Differentiated” Path to 0.7%. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

- Momani, B., and C. A. Ennis. 2012. “Between Caution and Controversy: Lessons from the Gulf Arab States as (re-) Emerging Donors.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 25 (4): 605–627.

- Neumayer, E. 2003. “What Factors Determine the Allocation of Aid by Arab Countries and Multilateral Agencies?” Journal of Development Studies 39 (4): 134–147.

- Neumayer, E. 2004. “Arab-Related Bilateral and Multilateral Sources of Development Finance: Issues, Trends, and the Way Forward.” The World Economy 27 (2): 281–300.

- Nonneman, G. 1988. Development, Administration and Aid in the Middle East. New York: Routledge.

- OECD. 2020. “Net ODA (indicator).” Accessed March 2 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1787/33346549-en.

- Pinto, V. C. 2014. “From “Follower” to “Role Model”: The Transformation to the UAE’s International Self-Image.” Journal of Arabian Studies 4 (2): 231–243.

- Ragab, E. 2017. “Beyond Money and Diplomacy: Regional Policies of Saudi Arabia and UAE After the Arab Spring.” The International Spectator 52 (2): 37–53.

- Said, E. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Vintage.

- Shushan, D., and C. Marcoux. 2011. “The Rise (and Decline?) of Arab Aid: Generosity and Allocation in the Oil Era.” World Development 39: 1969–1980.

- Smith, K. 2011. United Arab Emirates Statistical Reporting to the OECD Development Assistance Committee. Paris: OECD.

- Soubrier, E. 2017. “Evolving Foreign and Security Policies: A Comparative Study of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.” In The Small Gulf States: Foreign and Security Policies Before and After the Arab Spring, edited by K. S. Almezaini and J.-M. Rickli (Chapter 8, 123–143). New York: Routledge.

- UNDP. 2020. Yemen. Accessed December 12 2020. http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/YEM.

- Vasovic, A. 2013. “UAE Approves 400 mln Loan to Serbia, Eyes Airline Deal.” Accessed December 12 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/serbia-emirates/uae-approves-400-mln-loan-to-serbia-eyes-airline-deal-idUSL5N0CJ30B20130327.

- Villanger, E. 2007. “Arab Foreign Aid: Disbursement Patterns, Aid Politics and Motives.” Forum for Development Studies 34 (2): 223–256.

- World Bank. 2020. “GDP (Current US$), United Arab Emirates, Austria, Canada.” Accessed December 12 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?end=2018&locations=AE-AT-CA&start=2009.

- Young, K. E. 2017. “A New Politics of GCC Economic Statecraft: The Case of UAE Aid and Financial Intervention in Egypt.” Journal of Arabian Studies 7: 113–136.

- Ziadah, R. 2019. “The Importance of the Saudi-UAE Alliance: Notes on Military Intervention, Aid and Investment.” Conflict, Security & Development 19 (3): 295–300.