?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Kenyan households, as in many rural areas in developing countries, suffer frequently from effects of shocks. Yet, they have limited access to effective coping strategies. Vulnerable households end up resorting to ineffective coping strategies such as distressed sales of farmland. Distress land sales limit household productive capacity and increase vulnerability to future shocks, thus entrenching poverty. Using a nationally representative data collected in two waves, we examine the circumstances under which rural households in Kenya sell farmland following shocks. We find that specific shock characteristics, household characteristics and the household social and physical environments are associated with distress sales of farmland. The likelihood of selling farmland was higher for idiosyncratic shocks and those that resulted in higher monetary and material losses. The likelihood of engaging in distress land sales was also higher in households with older heads, with more land holding, where land markets existed and in households that depended on social safety nets. The likelihood of distress sales was however lower in households with more educated heads, more livestock value and access to all-weather roads. These findings are thereafter discussed in the Kenyan context, and policy suggestions are offered for building rural households’ resilience to shocks.

1. Introduction

Households in many rural areas in developing countries suffer frequently from the effects of shocks, which consequently perpetuate poverty. Kenya is among the shock-prone developing economies (Eckstein, Künzel, and Schäfer Citation2017). This is manifested in households suffering frequently from unexpected and/or unpredictable events which result in adverse effects on household welfare. Climate-induced shocks such as drought and floods; crop and livestock diseases; and agricultural commodity price fluctuations are the most prevalent shocks in the country. For instance, crop production shocks have been estimated to cause an annual loss of between 2% and 4.2% to the agricultural GDP (D’Alessandro et al. Citation2015). Human diseases are also prevalent and adversely affect household welfare through pain and suffering, death, foregone labor earnings and treatment costs (Quintussi et al. Citation2015; Mwai and Muriithi Citation2016). Other shocks emanate from Kenya’s economic, social and political integration with the rest of the countries in the globe and contribute to the incidents of food price inflation, unemployment and terror activities (Kiptui Citation2008; Musyoki, Pokhariyal, and Pundo Citation2012). Mostly, it is the rural households that are more vulnerable to these shocks due to: high dependence on agricultural-based livelihoods which are likely to be adversely impacted by climate shocks and price fluctuations, limited healthcare facilities, physical isolation, and poverty.

The majority of Kenyan households, as is the case in most developing economies, usually have limited access to the recommended risk-management strategies and solutions such as insurance, credit and formal safety nets, that are necessary to address adverse effects of shocks (Eriksen, Brown, and Kelly Citation2005; Mworia and Kinyamario Citation2008; Smucker and Wisner Citation2007; Del Ninno and Mills Citation2015). The available coping strategies are mostly ineffective in restoring household welfare as well as building resilience to future shocks. The common coping strategies to shocks include: drawing down on savings and liquidating assets, relying on social and institutional support networks, enhancing household labor force and participation, and adjusting and reducing household consumption expenditure (Republic of Kenya Citation2007; Republic of Kenya Citation2018). Some of the coping strategies adopted have potential detrimental effects on both the immediate and the long-term household welfare. These include taking children off school to go to work, reducing food and other essential consumption, and selling of productive assets such as farmland. Distress selling of farmland involves significant opportunity cost because it limits household productive capacity and increases vulnerability to future shocks, thus entrenching poverty. This is especially so in Kenya given that land is an important factor of production for rural households. In this study, we find out the circumstances under which rural households in Kenya sell farmland following shocks.

Generally, Kenya has a liberalized and active land market (both tenancy and sales) in urban and rural areas. The land policy in the country has enabled private land ownership which has consequently resulted in active land markets (Burke and Jayne Citation2014). Necessary administrative procedures have been institutionalized to enhance the transparency of the land transactions, for instance, the existence of land control boards for the exchange of agricultural land. However, there are areas, mainly in pastoralist communities, where land ownership is communal and thus market land transactions are limited or completely non-existent (Lesorogol Citation2005).

2. Literature review

There is extensive literature on household response to welfare shocks in developing economies. A distinction is normally made between effective and detrimental response strategies (Heltberg, Oviedo, and Talukdar Citation2015). Effective strategies (such as use of savings, insurance, social safety nets) restore and sustain household welfare while the detrimental strategies (such as sale of productive assets, cutting down food consumption, compromising education and health obligations) increase vulnerability to future shocks and perpetuate poverty (Kenjiro Citation2005; Beegle, Dehejia, and Gatti Citation2006; Amendah, Buigut, and Mohamed Citation2014; Heltberg, Oviedo, and Talukdar Citation2015). Household response to shocks is usually influenced by a mix of shock and household characteristics, as well as the environment of the household (Cashdan Citation1985; Adams, Cekan, and Sauerborn Citation1998; Ellis Citation1998; Dercon Citation2002; Sawada Citation2007; Modena and Gilbert Citation2012).

Shocks are either idiosyncratic (meaning that only one household or few households are affected) or covariate (affect most or all households in the community). Compared to idiosyncratic shocks, covariate shocks have severer adverse effects on households because of limited sharing of risks and therefore most likely to result in detrimental responses such as the sale of productive assets (Porter Citation2008; Günther and Harttgen Citation2009). However, other studies have found that idiosyncratic shocks such as diseases are likely to require emergency and lump sum funding for treatment and therefore result in sale of productive assets (Kenjiro Citation2005). Also influencing the coping options is the severity of shocks – which is measured as the financial and material losses suffered due to the shocks (Tongruksawattana et al. Citation2013). Other studies have established that persistent shocks deplete household coping capacity over time leading to distress sales of productive assets (Devereux Citation1993 Ruben and Masset Citation2003).

Household characteristics have been found to influence response to shocks. For example, household resource endowment provides a buffer against adverse effects of shocks (Yamano and Jayne Citation2004; Cooper and Wheeler Citation2016). The probability of distress asset sales, therefore, reduces with the size of resource endowment. Studies also indicate that households tend to sell small assets first (such as goats, sheep, and household items) and prefer to protect productive assets such as ploughing oxen and farmland (Devereux Citation1993; Yamano and Jayne Citation2004; Hoddinott Citation2006). Household labor size is considered an endowment for paid work, which provides a buffer to shocks (Heltberg and Lund Citation2009; Davis Citation2015; Kim, Lee, and Halliday Citation2018). Additionally, household education endowment has been found to have a positive association with effective shock–response strategies (Rashid, Langworthy, and Aradhyula Citation2006; Berman, Quinn, and Paavola Citation2014). Studies have also found that the motive of selling productive assets increases after certain age thresholds of household heads unless there is a need to inherit the assets to younger household members (Quisumbing Citation1996; Browning and Crossley Citation2001). In addition, studies on the effect of the gender of the household head on coping strategies have produced mixed results (Glewwe and Hall Citation1998; Porter Citation2012).

Besides the shocks and household characteristics, other factors influencing response to shocks are household agro-ecological, social, political and economic environment. These include access to credit services, which offers alternative opportunities to cope with shocks and thus limit distress land sales (Deininger and Jin Citation2007). Other factors are land ownership regimes and the status of land markets. For instance, Lesorogol (Citation2005) found that local-level norms in pastoral communities in Kenya discouraged land sales in order to preserve the pastoral enterprises. Although titling eases land transaction costs, Haugerud (Citation1989) and Syagga (Citation2011) found cases of informal land transactions in Kenya, in which title deeds were not necessary. Access to public services such as tarred roads improve market linkages, promote the emergence of formal financial infrastructure and job opportunities, all of which offer opportunities for effective coping with shocks (Fan, Nyange, and Rao Citation2005; Schwarze and Zeller Citation2005).

The key determinants of distress land sales have been highlighted in the literature review. However, contextual circumstances govern these relationships and thus a need for an empirical examination of the circumstances under which rural households in Kenya sell farmland following shocks. This empirical analysis is guided by the following questions;

What are the characteristics of the shocks associated with the distress sales of farmland in rural Kenya?

What are the household and other general characteristics associated with the distress sales of farmland in rural Kenya?

3. Methods

The determinants of distress sales of farmland are empirically estimated through a logistic regression model adopted from an approach used by Deininger, Jin, and Nagarajan (Citation2009). The logistic regression model compares the characteristics of shocks that resulted in the sale of farmland with those that did not. The model also compares the characteristics and circumstances of the households which sold farmland with those that did not. According to Long and Freese (Citation2006), this amounts to estimating the conditional probability of the response variable as a function of a set of explanatory variables. The relationship is formally expressed as;

The dependent variable takes either the value of one if the household sold farmland or zero if the household did not.

represents the independent variables,

indicates the specific observations (the households or shock events), and

represents respective coefficients.

is the model’s error term, which measures the fitted model’s deviation from the true/population ‘unobservable’ value and is characterized by a population mean of zero and constant variance.

Two logistic regression models are estimated in this study. In the first model, the probability that a shock event resulted in the sale of farmland is regressed against the nature of shocks (idiosyncratic versus covariate) and loss from the shocks (monetary and material loss). This regression is carried only for households that reported distress land sales. Since households reported a maximum of three shocks, it is observed in the data that some shocks resulted in the sale of farmland while others did not. This provides the necessary variability in the data to explore the characteristics of shocks that resulted in the sale of farmland.

The other model regresses the probability of households selling farmland against characteristics such as household size, age, gender and education status of household head; household resource endowment measured in livestock, land, income; and household characteristics such as access to credit, all-weather roads and existence of land markets, and land ownership status. While the choice of the variables used in the models was informed by the literature review, only the variables whose data was available were included in the estimation models. For this estimation, we used only households in districts and counties where cases of land sales were reported.

The study uses data from two waves of the Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey (KIHBS), collected by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) – the government’s official statistical agency. The first KIHBS was conducted in 2005–2006 and the second in 2015–2016, each wave lasting 12 months. Each KIHBS, therefore, covered all the possible seasonal variations. The two surveys covered all parts of the country in both rural and urban areas, resulting in a nationally representative data. The studies were conducted amongst randomly selected primary sampling units called clusters obtained from nationally representative sampling frames known as National Sample Survey and Evaluation Program (NASSEP). These sampling frames have clusters of households chosen based on the size proportion of the enumeration areas created using the preceding national population censuses (Republic of Kenya Citation2007, Citation2018). The sampling frames are designed to produce representative surveys both at the national and sub-national levels.

The 2005/2006 KIHBS was collected from 861 rural and 482 urban clusters generated randomly from the fourth edition of NASSEP designed using the 1999 Population and Housing Census. In each cluster, a random sample of 10 households was selected with uniform chance in each cluster, giving a sample size of 13,430 households. In the 2015/2016 wave of KIHBS, 1,412 rural and 988 urban clusters were randomly selected from the fifth edition of NASSEP, generated using the 2009 Kenya Population and Housing Census. In the second stage, 16 households from each of the clusters sampled in stage one were selected, which later in the third stage, gave 10 – also randomly selected – households, totaling into 24,000 households.

Both waves of the KIHBS used questionnaires containing almost similar modules on household information, access to various services and experience with shocks. In the shocks module, households were asked if they were severely affected by shocks in the period of five years to the date of each respective survey. Households reported a maximum of three shocks and the shocks were ranked in terms of severity. Financial losses were estimated for the shocks that resulted in lost value. The module additionally provides information on when the shocks occurred and whether the shock was idiosyncratic or covariate. Finally, households were asked to indicate (in order of importance) a maximum of three strategies used to deal with the adverse effects of the shocks. Among the listed coping strategies was the option of selling farmland. Accordingly, the data indicates the shocks that resulted in sale of farmland and others which did not, as well as the households that sold farmland and those that did not. It is these variations in the responses that are utilized to answer the study’s questions.

In the 2005/2006 KIHBS, out of 25,490 shocks reported by 11,016 households, 231 resulted in the sale of farmland. In 2015/2016 KIHBS, out of 27,531 shocks reported by 13,706 households, 108 resulted in the sale of farmland. To assess the characteristics of shocks that resulted in the sale of farmland, we sampled only the shocks from households that reported selling farmland. Using this criterion, 536 shocks were reported by 210 households in 2005/2006. These households are spread across the country in 56 out of the 69 districts sampled in 2005/2006. Using the same criteria in 2015/2016, 225 shocks were reported by 98 households. These households are found in 29 out of 47 counties in the country. To assess the characteristics of households that sold farmland following shocks, we sampled only the households that were in a position to sell land. This is because, in some parts of Kenya, land ownership regimes (for example, communal lands in some pastoralist communities) prohibit the commercial exchange of land. Accordingly, for these estimations, we used only households in districts (in 2005/2006 KIHBS) and counties (in 2015/2016 KIHBS) where cases of land sales were reported. To conduct the analysis, 10,894 and 13,571 households in 2005/2006 and 2015/2016 KIHBSs respectively, were used.

4. Results

The sampled households used different coping mechanisms to respond to the various shocks reported. The households listed up to three coping mechanisms for every shock reported. Tables A1–A6 in the Appendix show the coping strategies adopted by the households in response to shocks. For the coping strategies chosen as the first option, 146 and 67 shocks resulted in distress sales of farmland in 2005/2006 and 2015/2016 respectively. In addition, 160 and 67 shocks in 2005/2006 and 2015/2016 respectively resulted in renting of farmland. Health shocks (chronic diseases and deaths) and natural climate-related shocks (drought and floods) were the main drivers of distress sales of farmland. On the other hand, analysis of the 2005/2006 data revealed that shocks such as loss of employment, end of regular assistance, damage to household dwelling facilities and birth in the household were the least likely to be associated with distress sales of farmland. In the 2015/2016 survey, we found that poor prices of agricultural produce, fire, social shocks such eviction, family break-up and jailing of household breadwinner were least likely to be associated with distress sales of farmland. Similarly, renting of farmland was used as a response mechanism mainly for health and climate shocks in both survey periods. Other shocks with significant association with distress sales of farmland included large rise in agricultural input prices, loss of livestock, crop diseases and pests, and fall in sale prices of agricultural produce.

The analysis of the relationship of the size of shocks (as measured in monetary terms) and the probability of distress sales of farmland is presented in Tables A7 and A8 in the Appendix. Shocks with monetary cost of KES. 10,000 and above constituted more than half of the cases of distress land sales, indicating a possible association between cost of shocks and distress land sales in the two survey periods.

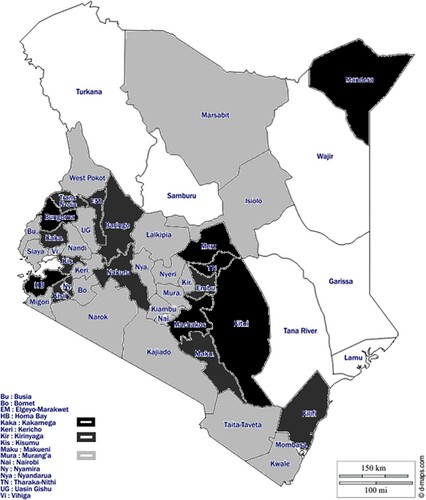

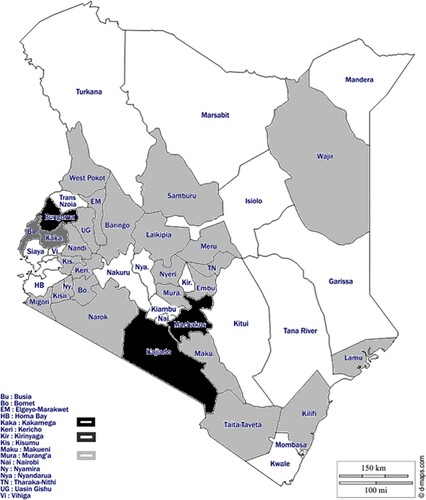

and provide a geographical representation of the incidences of distress sales of farmland in all the counties of Kenya in both 2005/2006 and 2015/2016 respectively. In counties such as Meru, Homa Bay, Kitui and Mandera, the likelihood of distress land sales reduced during the study periods. On the other hand, distress land sales increased marginally in Kajiado, Lamu and West Pokot counties.

Figure 1. Concentration of households that sold farmland in response to shocks per county – 2005/2006 KIHBS (the color density represents the spread of cases of distress land sales).

Figure 2. Concentration of households that sold farmland in response to shocks per county – 2015/2016 KIHBS (the color density represents the spread of cases of distress land sales).

As indicated in , most of the shocks reported by households that sold farmland were idiosyncratic, with the incidence greater in 2005/2006 than in 2015/2016. In addition, the estimated mean financial loss from shocks was higher in 2015/2016 compared to 2005/2006, even after factoring in the time value of money.

Table 1. Characteristics of shocks that led to distress sales of farmland.

As indicated in , the mean number of household labor force was lower in 2015/2016 compared to 2005/2006. This reflects the drop in mean household size (by one person) in the period between the two surveys. The mean age of household heads was marginally higher in 2015/2016. The number of females heading households increased in 2015/2016. This implies that there is an ongoing transformation in the Kenyan households, possibly related to women empowerment. Households with access to credit increased from 29% to 35%, possibly due to the increased supply and demand for credit over time. The mean number of households that used social support networks to cope with shocks reduced by almost half between the two study periods. Such a significant reduction could have resulted due to measurement errors in the data or could imply that households were increasingly using alternative coping options. Social safety networks in this study indicate strategies such as sending children to live with relatives, receiving help from government as well as from family and friends.

Table 2. Characteristics of households (in districts and counties where land was sold).

In 2005/2006, only 40% of sampled households owned title deeds compared to 50% in 2015/2016. Approximately 80% of households reported the presence of land markets in their communities in both study periods. This implies the existence of informal land transactions that are not necessarily pegged on ownership of title deeds.

A logistic regression model was fitted to uncover the circumstances associated with distress land sales. A chi-square test indicated that the model used was fit for the postulated relationships, which implies a correct model specification. Independent variables such as household livestock value, land size and percentage distribution of households with access to all-weather roads were found to have wide variations in their observations and were transformed into logarithms to correct for the dispersion in the observations. Other diagnostic tests conducted revealed that the residuals of the independent variables had constant variance as required for such estimation models in order to generate reliable results for statistical inference.

Estimations were done separately using 2005/2006 and 2015/2016 data, and then the pooled data, which has the combined 2005/2006 and 2015/2016 datasets on identically measured variables. The respective estimation results, described in marginal effects, are presented in and . Marginal effects provide the likelihood of selling farmland given a change in the hypothesized variables, while holding the other independent variables at their means.

Table 3. Shock characteristics influencing household decision to sell farmland as a coping mechanism (marginal effects).

Table 4. Household characteristics influencing decision to sell farmland as a coping mechanism (marginal effects).

presents the estimation results of the shock characteristics on the likelihood of distress land sales. The coefficient of nature of shocks was statistically significant in the 2005/2006 and the pooled data, indicating that idiosyncratic shocks (such as diseases, accidents, death of breadwinners and loss of employment) were more likely to be associated with distress land sales compared to covariate shocks such as droughts, floods, food price inflation, poor prices of agricultural produce and crop and animal diseases. The coefficients of financial and asset losses due to shocks were statistically significant in the two survey periods and in the pooled data, showing an increasing probability of distress sales of farmland with the magnitude of loss from the shocks. The coefficients of the nature of shocks (idiosyncratic or covariate) in the 2015/2016 data and the effect of time difference (between the two survey periods) were not significant.

The three estimations presented in produced mixed results. In the 2005/2006 model, the decision of households to participate in distress sales of farmland was found to be associated with the following variables: age (probability of selling increases with age up to a certain point, then the probability declines), education (households headed by individuals with tertiary level of education were less likely to participate in distress sales of farmland compared to households headed by those without formal education). The results also indicate that the probability of distress sales of farmland increased with household land size and in areas with functioning land markets. On the other hand, the probability of distress sales was found to be negatively associated with household livestock wealth and household access to all-weather roads.

The estimation model using the 2015/2016 data revealed that the households with access to all-weather roads and those with livestock were less likely to sell farmland due to shocks. Household land holding and the accessibility to land markets were positively associated with the probability of disposing of farmland as a coping strategy. The results also indicated that the households that depended on social safety systems were more likely to engage in distress land sales. However, characteristics such as labor size, age, gender and education status of the household head, and access to credit did not have a significant relationship with the household likelihood of engaging in distress land sales.

In the pooled data model, results revealed that the likelihood of distress land sales increased with the age of the household head (up to a certain level, then started decreasing). The probability of distress sales was high among households with more land holding, accessibility to land markets, household livestock wealth and in households that relied on social safety nets. The likelihood of distress land sales was lower for households headed by those with a secondary level of education, compared to the households headed by those without formal education. The estimation results using the pooled data revealed that the passage of time (between 2005 and 2016) had a significant association with the reduced likelihood of distress land sales.

Before discussing the study’s findings, it is useful to acknowledge key contextual issues regarding distress land sales in rural Kenya. First, some households store their wealth in form of land holdings and consciously use such holdings as a buffer against livelihood shocks. In this respect, land sales do not necessarily indicate a disadvantage to the household, but rather a conscious use of household resources to respond to shocks. The scope of the data used in this study does not allow for a complete analysis that can identify such nuances. Consequently, this study’s findings should be interpreted bearing this context in mind.

The other contextual issue is the existence of active land rental markets in the country, which moderates land sales (Jin and Jayne Citation2013). To forestall landlessness and decreased future productive capacity, distressed households can rent out their land instead of selling it off. In the 2005/2006 KIHBS, there was a higher probability of households renting out farmland in response to shocks compared to selling. In the 2015/2016 KIHBS, the incidence of renting and selling farmland was generally even. Similar to selling, renting of farmland was most prevalent as a response to climate and disease shocks, as well as crop and livestock pests and illnesses.

5. Discussion

This study sought to find out the circumstances under which households sold farmland as a response to shocks. Among the households that reported selling farmland, we assessed the characteristics of the shocks that led to the actual sale of farmland. The finding that household-specific (idiosyncratic) shocks were more likely to be associated with distress land sales implies weak risk-sharing in the sampled communities (Townsend Citation1994; Fafchamps and Lund Citation2003). This explanation, however, does not rule out other possible explanations. The results agree with those of Kenjiro (Citation2005) who found that idiosyncratic shocks led to more sales of farmland compared to covariate shocks in rural Cambodia. The author explains that such findings are also due to inefficient credit markets and the fact that responding to idiosyncratic shocks such as illnesses usually required resources in lump-sum. In addition, idiosyncratic shocks usually have severer adverse effects and therefore households respond using extreme measures such as reducing household food consumption, selling productive assets, engaging children in paid labor and bonding household labor to repay debts (Heltberg and Lund Citation2009).

The positive association between distress land sales and loss from shocks implies that shocks with huge losses are most likely to lead to destitution since households are forced to liquidate productive assets in order to cope. These findings are consistent with Yilma et al. (Citation2014) who found that shocks with intense financial consequences (such as diseases) were more likely to lead to the selling of assets (such as farmland) in a study of rural Ethiopia. Both Kenjiro (Citation2005) and Yilma et al. (Citation2014) opine that intense and severe shocks such as illnesses or loss of livelihoods are characterized by prompt financial requirements to cater for lump-sum payments needed within short lead times.

We further assessed the characteristics of households that sold farmland. For this assessment, we used the sample of households in areas where cases of land sales were reported. The coefficient of age in the 2005/2006 and pooled models indicate a positive, then negative association with the likelihood of selling farmland. The square of age has a negative coefficient implying that the effect of age on the probability of selling farmland is not strictly increasing with age, but was also reducing after certain years. This finding concurs with Gaviria (Citation2002) who found the effect of age having a non-linear association with the likelihood of household reducing consumption as a coping strategy in a sample of households from seven Latin American countries. The effect of age on household consumption response after adverse shocks was found to follow a similar pattern in a study by Wainwright and Newman (Citation2011) in rural Vietnam. Coping with shocks through reduction of consumption – just like selling of productive assets – is considered an ineffective coping strategy and has adverse long-term consequences on household welfare.

The finding that households with highly educated heads were less likely to sell farmland when hit by shocks is consistent with the findings by Rashid, Langworthy, and Aradhyula (Citation2006) in Bangladesh as well as Berman, Quinn, and Paavola (Citation2014) in Uganda. These results agree that education – as a measure of human capital – predisposes households to higher, stable and diversified incomes which consequently build resilience to shocks and prevent distress sales of productive assets. The direct association between land holding and distress land sales is consistent with the basic principle that more endowment increases land supply at the market. However, since these are distress sales, it indicates a possibility of household vulnerability to shocks, as well as absence of risk-sharing markets to mitigate the adverse effects of shocks (Deininger and Jin Citation2007). The results indicate an association between the existence of land markets and distress sales of farmland. Other studies have found that in jurisdictions where land sales are prohibited, households rely instead on non-market coping strategies such as social safety nets and support (Carter et al. Citation2006). This finding was supported by this study’s data in which the use of social safety networks was found to be marginally higher in areas where land sales did not exist.

The finding that the likelihood of selling farmland was lower in households with higher livestock wealth is supported by the postulation that ownership of easy-to-sell assets (such as livestock) reduces the likelihood of disposing of productive assets – an option that compromises household future livelihoods. This finding is consistent with the literature that households prefer sequencing interventions to shocks according to the associated costs of each intervention, and in such regard, selling of farmland is mostly adopted as a last resort (Devereux Citation1993; Janzen and Carter Citation2018). In all the estimation models, an inverse and significant association was found between household access to all-weather roads and the probability of distress land sales. This finding is consistent with the theory and empirical studies that access to public services encourages income diversification, and increases opportunities for trade and integration of community livelihoods into the mainstream transaction macro-economy, which increases household resilience to shocks (Christiaensen and Subbarao Citation2005).

Theoretically, social safety nets (both formal and informal) help households cope with shocks which, accordingly, protects liquidation of productive assets (Barrientos and Hulme Citation2009). The positive association between use of social safety nets and distress land sales implies that the existing social support systems in Kenya are inadequate in shielding households’ productive assets. The association also implies that the dependence on social support could contribute to unintended and undesired outcomes such as sale of productive assets (Dercon Citation2002). This finding is consistent with other empirical studies that social safety nets did not result in significant protection of productive assets (livestock) in times of shocks in rural Ethiopia (Andersson, Mekonnen, and Stage Citation2011). However, a meta-analysis of evidence from studies in developing economies by Hidrobo et al. (Citation2018) found that formal social protection programs helped households to protect and increase various productive assets.

The coefficient of the effect of time passage in the pooled data was significant only in the household-characteristics model. It is possible that in the ten years between 2005/2006 and 2015/2016, there were structural changes in the household characteristics that reduced the likelihood of engaging in distress land sales. However, results imply that there were no changes in the characteristics of shocks over the same period to be significantly associated with household decision on distress land sales. It is expected that while shocks adversely affecting household may remain unchanged over time (climatic shocks, diseases, economic shocks), household attributes may transform within a decade through interventions such as infrastructure development, growth of social support systems, mobile money transfer systems and reduction in poverty. Indeed, between the two study periods, poverty in Kenyan households reduced from 46.8% to 36.1% (World Bank Citation2019).

The non-existence of association between the gender of household head and the likelihood of engaging in distress land sales is consistent with empirical works such as Glewwe and Hall (Citation1998) that found no gender role in household coping mechanisms. The finding that ownership of title deeds was not significantly associated with distress sales can be explained by the prevalence of informal land transactions in Kenya (Haugerud Citation1989; Syagga Citation2011). Failing to establish an inverse relationship between household’s access to credit and likelihood of engaging in distress land sales is contrary to the existing literature that found credit access useful in aiding vulnerable households protect their assets and effectively cope with shocks (Morduch Citation1998; Beegle, Dehejia, and Gatti Citation2006; Guarcello, Mealli, and Rosati Citation2009). The zero-association found in this study could have resulted from possible measurement errors in the data. Finally, the study could not confirm the hypothesis that more labor force provides households with opportunities for income diversification which cushions households from distress sales of productive assets (Christiaensen and Subbarao Citation2005). This could imply that the sampled rural economies are less diversified and, therefore, more household labor pool does not provide any advantage because of limited employment opportunities (Jayachandran Citation2006).

6. Conclusion

Distress sales of farmland resulting from adverse effects of shocks are undesirable because they potentially reduce household future productive capacity. This is so considering that most of rural economic activities are based on land as the primary factor of production. Using a nationally representative data from Kenya, this study assessed the circumstances under which rural households engaged in distress sales of farmland. The study findings indicate that specific shock characteristics, household characteristics and the household social and physical environments were associated with the likelihood of engaging in distress sales of farmland. The likelihood of selling farmland was higher for idiosyncratic shocks and also in shocks that resulted in higher monetary and material losses. The likelihood of distress land sales was also higher in households with older heads, with more land holding, where land markets existed and in households that depended on social safety nets. The likelihood of distress sales was however lower in households headed by more educated persons, with more livestock value, and with access to all-weather roads.

Based on these results, the following policy recommendations are made in the context of Kenya. First, the government should continue supporting the unconditional cash transfer to Kenyans above 70 years to shield the aged from the pressure of distressed land sales. Second, education in the country should emphasize on the acquisition of skills that can translate into gainful employment in order to shield the rural households from the vagaries of subsistence livelihoods. Third, there is a need to examine the adequacy of the existing credit systems in the country in mitigating household vulnerability to shocks. To address this, the government should enhance the financial integration of rural households to provide them with opportunities to hedge risk through solutions such as health insurance, weather index-based insurance, savings and loan facilities. Fourth, there is a need to promote a conducive policy environment for livestock production such as management of diseases and pests, livestock feeds and nutrition, livestock marketing, research, and extension services. Livestock such as goats, sheep and cattle provide critical lifelines to rural households especially those in arid and semi-arid areas. Finally, public policy should focus on building physical infrastructure (such as roads, fresh produce and livestock markets, schools and health facilities) as a strategy for reducing vulnerability to shocks for the physically isolated communities in the country.

Acknowledgements

The study’s findings, opinions and recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the Consortium, its individual members or the AERC Secretariat. Also appreciated are comments and reviews on previous versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, Alayne M., Jindra Cekan, and Rainer Sauerborn. 1998. “Towards a Conceptual Framework of Household Coping: Reflections from Rural West Africa.” Africa 68 (2): 263–283. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1161281.

- Amendah, Djesika D., Steven Buigut, and Shukri Mohamed. 2014. “Coping Strategies among Urban Poor: Evidence from Nairobi, Kenya.” PLoS ONE 9 (1): e83428. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083428.

- Andersson, Camilla, Alemu Mekonnen, and Jesper Stage. 2011. “Impacts of the Productive Safety Net Program in Ethiopia on Livestock and Tree Holdings of Rural Households.” Journal of Development Economics 94 (1): 119–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2009.12.002.

- Barrientos, Armando, and David Hulme. 2009. “Social Protection for the Poor and Poorest in Developing Countries: Reflections on a Quiet Revolution.” Oxford Development Studies 37 (4): 439–456. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13600810903305257.

- Beegle, Kathleen, Rajeev H. Dehejia, and Roberta Gatti. 2006. “Child Labor and Agricultural Shocks.” Journal of Development Economics 81 (1): 80–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.05.003.

- Berman, Rachel J., Claire H. Quinn, and Jouni Paavola. 2014. “Identifying Drivers of Household Coping Strategies to Multiple Climatic Hazards in Western Uganda: Implications for Adapting to Future Climate Change.” Climate and Development 7 (1): 71–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2014.902355.

- Browning, Martin, and Thomas F. Crossley. 2001. “The Life-Cycle Model of Consumption and Saving.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 15 (3): 3–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.15.3.3.

- Burke, William J., and T. S. Jayne. 2014. “Smallholder Land Ownership in Kenya: Distribution Between Households and Through Time.” Agricultural Economics 45 (2): 185–198.

- Carter, Michael, Peter Little, Tewodaj Mogues, and Workneh Negatu. 2006. Shocks, Sensitivity and Resilience: Tracking the Economic Impacts of Environmental Disaster on Assets in Ethiopia and Honduras. DSGC Discussion Paper 32. Washington, DC: IFPRI.

- Cashdan, Elizabeth A. 1985. “Coping with Risk: Reciprocity Among the Basarwa of Northern Botswana.” Man 20 (3): 454. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2802441.

- Christiaensen, Luc J., and Kalanidhi Subbarao. 2005. “Towards an Understanding of Household Vulnerability in Rural Kenya.” Journal of African Economies 14 (4): 520–558. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/eji008.

- Cooper, Sarah Jane, and Tim Wheeler. 2016. “Rural Household Vulnerability to Climate Risk in Uganda.” Regional Environmental Change 17 (3): 649–663. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-1049-5.

- D’Alessandro, S., J. Caballero, S. Simpkin, and J. Lichte. 2015. Kenya Agricultural Risk Assessment. Agriculture Global Practice Technical Assistance Paper. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- Davis, D. 2015. “Consumption Smoothing and Labor Supply Allocation Decisions: Evidence from Tanzania.” Masters, University of San Francisco. https://repository.usfca.edu/thes/142.

- Deininger, Klaus, and Songqing Jin. 2007. “Land Sales and Rental Markets in Transition: Evidence from Rural Vietnam.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2007.00484.x.

- Deininger, Klaus, Songqing Jin, and Hari K. Nagarajan. 2009. “Determinants and Consequences of Land Sales Market Participation: Panel Evidence from India.” World Development 37 (2): 410–421. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.06.004.

- Del Ninno, Carlo, and Bradford Mills. 2015. Safety Nets in Africa: Effective Mechanisms to Reach the Poor and Most Vulnerable. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Dercon, S. 2002. “Income Risk, Coping Strategies, and Safety Nets.” The World Bank Research Observer 17 (2): 141–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/17.2.141.

- Devereux, Stephen. 1993. “Goats Before Ploughs: Dilemmas of Household Response Sequencing During Food Shortages.” IDS Bulletin 24 (4): 52–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.1993.mp24004006.x.

- Eckstein, David, Vera Künzel, and Laura Schäfer. 2017. Global Climate Risk Index 2018: Who Suffers Most from Extreme Weather Events? Weather-Related Loss Events in 2016 and 1997 to 2016. Bonn: Germanwatch e.V. www.germanwatch.org.

- Ellis, Frank. 1998. “Household Strategies and Rural Livelihood Diversification.” Journal of Development Studies 35 (1): 1–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220389808422553.

- Eriksen, Siri H., Katrina Brown, and P. Mick Kelly. 2005. “The Dynamics of Vulnerability: Locating Coping Strategies in Kenya and Tanzania.” The Geographical Journal 171 (4): 287–305. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2005.00174.x.

- Fafchamps, Marcel, and Susan Lund. 2003. “Risk-Sharing Networks in Rural Philippines.” Journal of Development Economics 71 (2): 261–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3878(03)00029-4.

- Fan, Shenggen, David Nyange, and Neetha Rao. 2005. Public Investment and Poverty Reduction in Tanzania: Evidence from Household Survey Data. No. 580-2016-39335. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/58373/.

- Gaviria, Alejandro. 2002. “Household Responses to Adverse Income Shocks in Latin America.” Revista Desarrollo y Sociedad, no. 49: 99–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.13043/dys.49.3.

- Glewwe, Paul, and Gillette Hall. 1998. “Are Some Groups More Vulnerable to Macroeconomic Shocks Than Others? Hypothesis Tests Based on Panel Data from Peru.” Journal of Development Economics 56 (1): 181–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3878(98)00058-3.

- Guarcello, Lorenzo, Fabrizia Mealli, and Furio Camillo Rosati. 2009. “Household Vulnerability and Child Labor: The Effect of Shocks, Credit Rationing, and Insurance.” Journal of Population Economics 23 (1): 169–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-008-0233-4.

- Günther, Isabel, and Kenneth Harttgen. 2009. “Estimating Households Vulnerability to Idiosyncratic and Covariate Shocks: A Novel Method Applied in Madagascar.” World Development 37 (7): 1222–1234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.006.

- Haugerud, Angelique. 1989. “Land Tenure and Agrarian Change in Kenya.” Africa 59 (1): 61–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1160764.

- Heltberg, Rasmus, and Niels Lund. 2009. “Shocks, Coping, and Outcomes for Pakistan’s Poor: Health Risks Predominate.” The Journal of Development Studies 45 (6): 889–910. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380902802214.

- Heltberg, Rasmus, Ana María Oviedo, and Faiyaz Talukdar. 2015. “What Do Household Surveys Really Tell Us About Risk, Shocks, and Risk Management in the Developing World?” The Journal of Development Studies, 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2014.959934.

- Hidrobo, Melissa, John Hoddinott, Neha Kumar, and Meghan Olivier. 2018. “Social Protection, Food Security, and Asset Formation.” World Development 101: 88–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.08.014.

- Hoddinott, John. 2006. “Shocks and Their Consequences Across and Within Households in Rural Zimbabwe.” Journal of Development Studies 42 (2): 301–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380500405501.

- Janzen, Sarah A., and Michael R. Carter. 2018. “After the Drought: The Impact of Microinsurance on Consumption Smoothing and Asset Protection.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 101 (3): 651–671. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aay061.

- Jayachandran, Seema. 2006. “Selling Labor Low: Wage Responses to Productivity Shocks in Developing Countries.” Journal of Political Economy 114 (3): 538–575. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/503579.

- Jin, Songqing, and Thomas S. Jayne. 2013. “Land Rental Markets in Kenya: Implications for Efficiency, Equity, Household Income, and Poverty.” Land Economics 89 (2): 246–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.3368/le.89.2.246.

- Kenjiro, Yagura. 2005. “Why Illness Causes More Serious Economic Damage Than Crop Failure in Rural Cambodia.” Development and Change 36 (4): 759–783. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155x.2005.00433.x.

- Kim, Kyeongkuk, Sang-Hyop Lee, and Timothy Halliday. 2018. Health Shocks, the Added Worker Effect, and Labor Supply in Married Couples: Evidence from South Korea. University of Hawaii Working Papers. http://www.economics.hawaii.edu/research/workingpapers/WP_18-12.pdf.

- Kiptui, Moses. 2008. “Does Exchange Rate Volatility Harm Exports? Empirical Evidence from Kenya’s Tea and Horticulture Exports.” In Workshop Paper at the CSAE Conference at Oxford University, 16–18. Oxford, UK.

- Lesorogol, Carolyn K. 2005. “Privatizing Pastoral Lands: Economic and Normative Outcomes in Kenya.” World Development 33 (11): 1959–1978. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.05.008.

- Long, Scott, and Jeremy Freese. 2006. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata. Texas: A Stata Press Publication.

- Modena, Francesca, and Christopher L. Gilbert. 2012. “Household Responses to Economic and Demographic Shocks: Marginal Logit Analysis Using Indonesian Data.” Journal of Development Studies 48 (9): 1306–1322. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2012.685723.

- Morduch, Jonathan. 1998. Review of Does Microfinance Really Help the Poor?: New Evidence from Flagship Programs in Bangladesh. Research Program in Development Studies. http://www.Citeseerx.ist.psu.edu. Woodrow School of Public and International Affairs.

- Musyoki, Danson, Ganesh P. Pokhariyal, and Moses Pundo. 2012. “The Impact of Real Exchange Rate Volatility on Economic Growth: Kenyan Evidence.” Business and Economic Horizons 7: 59–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.15208/beh.2012.5.

- Mwai, Daniel, and Moses Muriithi. 2016. “Economic Effects of Non-Communicable Diseases on Household Income in Kenya: A Comparative Analysis Perspective.” Public Health Res 6 (3): 83–90.

- Mworia, John, and Jenesio Kinyamario. 2008. “Traditional Strategies Used by Pastoralists to Cope with La Nina Induced Drought in Kajiado, Kenya.” African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2 (1): 10–14.

- Porter, Catherine. 2008. “Examining the Impact of Idiosyncratic and Covariate Shocks on Ethiopian Households’ Consumption and Income Sources.” Chapter of DPhil dissertation, Oxford University. https://www.dagliano.unimi.it/media/porter.pdf.

- Porter, Catherine. 2012. “Shocks, Consumption and Income Diversification in Rural Ethiopia.” Journal of Development Studies 48 (9): 1209–1222. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2011.646990.

- Quintussi, Marta, Ellen Van de Poel, Pradeep Panda, and Frans Rutten. 2015. “Economic Consequences of Ill-Health for Households in Northern Rural India.” BMC Health Services Research 15 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0833-0.

- Quisumbing, Agnes R. 1996. “Modeling Household Behavior in Developing Countries: Discussion.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 78 (5): 1346–1348. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1243519.

- Rashid, Arif, Mark Langworthy, and Satheesh Aradhyula. 2006. “Livelihood Shocks and Coping Strategies: An Empirical Study of Bangladesh Households.” In Presentation at the American Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, 23–26. Long Beach, CA. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/21231/.

- Republic of Kenya. 2007. Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey (KIHBS) 2005/06 (Revised Edition): Basic Report. Nairobi: Government Printer.

- Republic of Kenya. 2018. Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey (KIHBS) 2015/16: Basic Report. Nairobi: Government Printer.

- Ruben, Ruerd, and Edoardo Masset. 2003. “Land Markets, Risk and Distress Sales in Nicaragua: The Impact of Income Shocks on Rural Differentiation.” Journal of Agrarian Change 3 (4): 481–499. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0366.00063.

- Sawada, Yasuyuki. 2007. “The Impact of Natural and Manmade Disasters on Household Welfare.” Agricultural Economics 37: 59–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2007.00235.x.

- Schwarze, Stefan, and Manfred Zeller. 2005. “Income Diversification of Rural Households in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia.” Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture 44 (1): 61–74.

- Smucker, Thomas A., and Ben Wisner. 2007. “Changing Household Responses to Drought in Tharaka, Kenya: Vulnerability, Persistence and Challenge.” Disasters 32 (2): 190–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2007.01035.x.

- Syagga, Paul. 2011. Land Tenure in Slum Upgrading Projects. French Institute for Research in Africa. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00751866/.

- Tongruksawattana, Songporne, Vera Junge, Hermann Waibel, Javier Diez, and Erich Schmidt. 2013. “Ex-Post Coping Strategies of Rural Households in Thailand and Vietnam.” In Vulnerability to Poverty, edited by Klasen, Stephan, and Hermann Waibel, 216–257. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Townsend, Robert M. 1994. “Risk and Insurance in Village India.” Econometrica 62 (3): 539. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2951659.

- Wainwright, Fiona, and Carol Newman. 2011. Income Shocks and Household Risk-Coping Strategies: Evidence from Rural Vietnam. Institute for International Integration Studies Discussion paper 358. https://www.researchgate.net.

- World Bank. 2019. World Development Indicators. https://data.worldbank.org/country/kenya.

- Yamano, Takashi, and T. S. Jayne. 2004. “Measuring the Impacts of Working-Age Adult Mortality on Small-Scale Farm Households in Kenya.” World Development 32 (1): 91–119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.07.004.

- Yilma, Zelalem, Anagaw Mebratie, Robert Sparrow, Degnet Abebaw, Marleen Dekker, Getnet Alemu, and Arjun S. Bedi. 2014. “Coping with Shocks in Rural Ethiopia.” The Journal of Development Studies 50 (7): 1009–1024. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2014.909028.

Appendix

Table A1. First coping option with shocks (using 2005/2006 KIHBS).

Table A2. Second coping option with shocks (using 2005/2006 KIHBS).

Table A3. Third coping option with shocks (using 2005/2006 KIHBS).

Table A4. First coping option with shocks (using 2015/2016 KIHBS).

Table A5. Second coping option with shocks (using 2015/2016 KIHBS).

Continued

Table A6. Third coping option with shocks (using 2015/2016 KIHBS).

Size of shocks (in monetary terms) and distress sales of farmland

Table A7. Size of the shocks (in monetary terms) and the incidence of distress sales of farmland (2005–2006 KIHBS).

Table A8: Size of the shocks (in monetary terms) and the incidence of distress sales of farmland (2015–2016 KIHBS).