?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Despite the successful transition into democracy in South Africa, poverty and inequality levels remain consistently high for an upper-middle-income country. The pace of human capital development continues to be inadequate to solve the socio-economic challenges. The objective of the study is to examine the effect of human capital formation represented by education attainment, on poverty and inequality in the Eastern Cape province. Using the Pooled Mean Group (PMG) estimator, the study investigates the long-run relationship between the variables. The study found that an increase in human capital leads to a decline in poverty levels. However, human capital is positively related to income inequality which is an indication of unequal economic opportunities and inequality in the education system. The study recommends that policies be introduced to reduce inequality in schools. Community involvement in improving the quality of schools is of utmost importance. Education policies such as school choice may have contributed to education inequality.

1. Introduction

Technological developments coupled with globalization have changed the functioning of economies and skills requirements for future work (World Economic Forum and PricewaterhouseCoopers Citation2021). Human capital development has therefore been prioritized in government policies worldwide, and more so in developing countries which have a history of low levels of human capital (Keese and Tan Citation2013). The prioritization of human capital formation, however, has not successfully promoted the development of required skills for successful participation in the twenty-first century economy.

Despite the successful transition into democracy in South Africa, poverty and inequality levels remain consistently high for an upper-middle-income country (StatsSA Citation2020a). Furthermore, low-quality education received by a significant proportion of the population has perpetuated a persistently high unemployment rate. One of the priorities of the National Development Plan (NDP) and the Eastern Cape Provincial Development Plan (PDP) is to improve the quality of education and to promote skills development. However, the progress in enhancing human development in the areas of education remains inadequate to solve the socio-economic issues.

Significant amount of expenditures on education and health in South Africa and Eastern Cape have not been translated into higher levels of human capital (StatsSA Citation2020a). In spite of the improvements in promoting access to education since the advent of democracy, the low quality of education continues to hinder progress in skills development. The low progression of students in the further education and training (FET) phase, which represents Grades 10–12, attests to the low quality of basic education. This has been one of the contributors to the low levels of tertiary education attainment (StatsSA Citation2019a). According to the World Bank (Citation2020), the productivity of a child born in South Africa in 2020 is estimated to be 43% of maximum attainable level in the event of complete education and health. The quality-adjusted expected years of schooling is 5.6 years compared to the unadjusted figure of 10.2 years.

The problems of low-quality education and high poverty and inequality are more pronounced in the Eastern Cape compared to other provinces in South Africa due to its rural nature. The performances of students from the province in National Senior Certificate (NSC) and international examinations are amongst the worst from a provincial perspective (Amnesty International Citation2020). The poor performance of learners is linked to low-quality education, high poverty and inequality levels. Due to high poverty levels, most students from poor households attend no-fee schools plagued by low-quality education (StatsSA Citation2020b). Therefore, despite the rise in education attainment over the years, education inequality continues to be a major contributor to perpetuated poverty traps.

The objective of the study is to examine the effect of human capital formation on poverty and inequality in the Eastern Cape province.Footnote1 The component of human capital that is of interest in this study is education attainment. As such, the phrases ‘human capital’ and ‘education attainment’ will be used interchangeably. There is scant evidence on the effect of human capital on poverty and inequality in developing countries. A number of recent studies focus on the human capital-economic growth nexus (Bhorat, Cassim, and Tseng Citation2016; Altiner and Toktas Citation2017; Ogundari and Awokuse Citation2018; Karambakuwa, Ncwadi, and Phiri Citation2020). However, economic growth though necessary is insufficient for the achievement of some of the socio-economic goals. The structure of the study is as follows: section two discusses the reviewed theoretical and empirical literature, section three provides an overview of human capital, poverty and inequality in the Eastern Cape while section four outlines the methodology and describes the data. Section five presents the results of the empirical analysis and lastly, section six concludes the study.

2. Literature review

2.1 . Theoretical literature

The nexus between human capital, poverty and inequality can be traced back to Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations textbook. Adam Smith distinguished between skilled and unskilled workers (also referred to as common labour) (Chiswick Citation2003). Skilled workers due to their investments in education and training, earn higher incomes in comparison to unskilled workers. Mincer (Citation1957) initiated the theoretical analysis of the relationship between human capital and inequality. In his model, human capital represented by on-the-job training, is the major determinant of uneven or skewed distribution of income. Models developed by Schultz (Citation1961) and Becker (Citation1962) also emphasize the positive impact of human capital on income distribution.

According to Chiswick (Citation1968), the relationship between education/schooling and income inequality is not straightforward. This notion was supported by Knight and Sabot (Citation1983) who argued that the effect of schooling on inequality is dependent on variables such as the rate of return to education (Abdullah, Doucouliagos, and Manning Citation2015). An increase in human capital formation sets in motion two opposing effects; the composition and wage compression effects (Knight and Sabot Citation1983; Gregorio and Lee Citation2002). The composition effect increases inequality initially as the number individuals with more education expands. However, the wage compression effect reduces inequality by reducing returns to education as the number of educated workers increases. Therefore, the effect of education on income distribution is ambiguous.

The ambiguity in the relationship between average schooling and inequality can be specified by the following equation:

(1)

(1) where Y indicates the level of earnings, r is the rate of return to schooling, S is the years of schooling and u comprises the other factors that impact earnings besides the level of education.

The variance or distribution of earnings can be shown as follows:

(2)

(2)

Educational inequality results in an increased income inequality given the rate of return of schooling and the level of schooling (Gregorio and Lee Citation2002; Chiswick Citation1968). A reduction in the returns to education indicated by a negative covariance between r and S, suggests that higher levels of schooling mitigate against income inequality. However, independence between r and S, causes a positive relationship between schooling levels and inequality. This finding may be in line with a priori expectations for a developing economy such as South Africa with lower levels of human capital. Despite the improvements in education and schooling over the last two decades, inequality remains persistently high. Access to education may have contributed to high inequality as richer households have been able to access higher quality education compared to the poor majority.

The phenomenon of higher levels of schooling increasing inequality can be explained by high poverty levels which prevent low-income households/individuals from investing or accessing quality education. Galor and Zeira (Citation1988, Citation1993) and Galor and Tsiddon (Citation1997) and Ceroni (Citation2001) developed models that highlight the negative impact of inequality and poverty on human capital accumulation. Galor and Zeira (Citation1988) suggested that in the presence of credit market imperfections, poverty traps prevent investments in human capital. According to this theory, higher returns to education encourage the wealthy and skilled individuals to invest in education compared to low income and unskilled individuals. Galor and Tsiddon (Citation1997) developed a model which proposed that parental education is a major determinant of an individual’s level of education. This theory is applicable in developing countries such as South Africa where low levels of parental education perpetuate poverty traps due to lack of investments in quality education. Ceroni (Citation2001) showed that individual preferences ensure that the poor require higher returns in order to invest in education. As such poverty traps are more prevalent in the presence of high inequality.

2.2. Empirical literature

Empirical studies investigating the relationship between human capital, poverty and inequality, present contradictory results to some extent. Lee and Lee (Citation2018) found that higher levels of education are associated with lower income inequality in Asian countries. However, education inequality increases income inequality. Menezes Filho and Kirschbaum (Citation2019) showed that an increase in secondary education graduates has a negative impact on inequality in Brazil. Ismail and Yussof (Citation2010) found that human capital variables (which included schooling, training and health) reduced income inequality in Malaysia. In line with Lee and Lee (Citation2018), Yang and Qiu (Citation2016) found that education inequality is a major determinant of income inequality. Children from richer families are able to access higher quality education compared to those from poor families.

Coady and Dizioli (Citation2018) concluded that an increase in average years of schooling decreases income inequality through its negative effect on inequalities in education. Furthermore, an increase in average years of schooling for younger individuals is vital for reducing inequality especially in developing countries. Tchamyou (Citation2020) reached a conclusion similar to Coady and Dizioli (Citation2018) and advocated for improvements in primary school education as a means to reduce inequality through financial access. Shimeles and Nabassaga (Citation2018) reported that higher education is negatively related to consumption inequality, and this is association is driven by decreasing education returns. Furthermore, returns to higher education increase asset inequality. Abrigo, Lee, and Park (Citation2018) found that human capital expenditures result in a decline in inequality by increasing labour income for low-income households.

Some studies suggest that the relationship between human capital and inequality is not straightforward. Lam, Finn, and Leibbrandt (Citation2015) reported that declines in schooling inequality have contributed to reductions in income inequality in Brazil. However, for South Africa, rising returns to tertiary education have offset the effect of equality in schooling on income inequality. Castelló-Climent and Doménech (Citation2021) found results similar to Lam, Finn, and Leibbrandt (Citation2015). They concluded that the decline in human capital inequality has not contributed significantly to a similar reduction in income inequality as returns to education are positively correlated with the level of education. Gruber and Kosack (Citation2014) highlighted that primary school enrollment only reduces income inequality for countries that spend more on primary education. Chani et al. (Citation2014) found that there is a long-run relationship between human capital inequality and income inequality. However, the causality runs from income to human capital inequality.

According to literature, poverty and human capital have a two-way causal relationship. On one end, poverty hinders the accumulation of human capital. Zhang (Citation2014) reported that high costs of education in Western China prevent low-income households from accessing education which perpetuates the poverty trap. Hai and Heckman (Citation2017) highlighted the presence of credit constraints which negatively affect human capital accumulation, especially for permanently poor households. The authors stressed the need for more equality in cognitive and non-cognitive ability in order to reduce inequality. Attanasio et al. (Citation2017) reported that cognitive deficits caused by ill health also perpetuate poverty. Furthermore, investment in education by high-income parents for children at lower education levels causes human capital inequality.

A significant portion of empirical literature highlights the effect of human capital on poverty levels. Studies by Hong and Pandey (Citation2007) and Arias, Giménez, and Sanchez (Citation2016) employed Logistic and Probit models respectively to show that human capital reduces the likelihood of an individual being poor. Hong and Pandey (Citation2007) suggest that tertiary education is a major determinant of the poverty levels of minorities and for those with less than tertiary education, training and health are crucial for their poverty status. Arias, Giménez, and Sanchez (Citation2016) found that human capital is more effective in reducing the likelihood of poverty in rural communities.

Ali and Ahmad (Citation2013), Janjua and Kamal (Citation2014) and David et al. (Citation2018) found that human capital has a negative impact on poverty levels in developing countries. Collin and Weil (Citation2020) are of the view that investment in human capital accumulation is more effective in reducing poverty compared to physical capital. Winters and Chiodi (Citation2011) concluded that higher levels of education result in structural transformation where workers move from agricultural to non-agricultural employment with higher wages. This may have the effect of reducing poverty and inequality levels. Similarly, Arsani, Ario, and Ramadhan (Citation2020) found that education (especially tertiary education) improves the wealth status of individuals, and reduces poverty levels.

3. Overview of human capital, poverty and inequality in the Eastern Cape

This section provides a description of the trends in human capital, poverty and inequality in the Eastern Cape. Eastern Cape’s PDP is drawn from the NDP to a large extent, and advocates for a knowledgeable and healthy citizenry that can contribute to the growth and development of province and South Africa at large. Education, training and innovation are regarded as key instruments in an attempt to achieve socio-economic goals of poverty alleviation and inequality reduction. To achieve growth and development, the PDP advocates for the promotion of early childhood development (ECD) and basic education, which prepare students for further education. Furthermore, the growth of technical and vocational education and training (TVET), community colleges and higher education institutions is envisioned in order to impart vocational skills, foster innovation and broaden access to education and training (Republic of South Africa Citation2014).

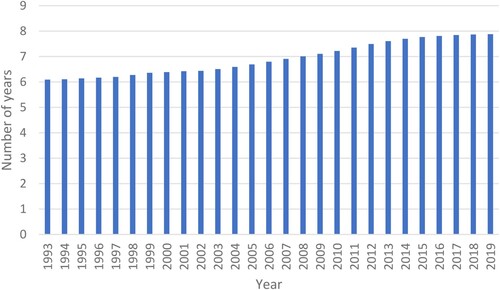

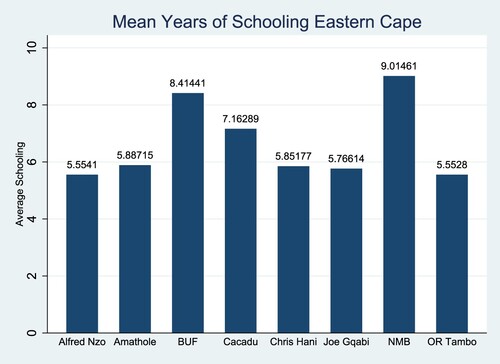

shows the trend in mean years of schooling in the Eastern Cape. Mean years of schooling is defined by UNESCO as the average number of completed years of schooling for the population aged 25 and above, excluding repeated grades. An upward trend is observed in average years of schooling from around 6 years in the early 1990s to just below 8 years in 2019. The increase in education attainment can be viewed as a success story, however, several factors should be considered. The rise in average years of schooling has been driven by the two metropolitan municipalities, also known as metros (Nelson Mandela Bay and Buffalo City) and Cacadu District. As highlighted by , the smaller and more rural districts have low levels of education attainment with average years of schooling lower than 6 years for the period 1993–2019. The problem of low-quality education in the Eastern Cape is also concealed by the upward trend in the number of years of education. According to StatsSA (Citation2020b), school attendance of students aged 5 years and above is the highest (92%) in the Eastern Cape in comparison with other provinces possibly due to the fact that are more no-fee schools. However, with regards to the percentage of students attending higher education institutions and TVET colleges, the Eastern Cape province is the worst performing province in South Africa. This is an indication of low-quality basic and secondary education, which negatively affects student progression rates. Furthermore, problems of lack of teachers and books are more profound in the Eastern Cape, which also attests to low student progression rates.

According to Roodt (Citation2018), Eastern Cape learners along with those in North-West were the worst performers in Trends in International Mathematics and Science (TIMMS) assessments. Learners at no-fee schools (which are more prevalent in Eastern Cape rural areas) were 25% worse than their peers from fee-paying schools. According to the Progress in International Reading and Literacy Study (PIRLS) conducted in 2017, 85% of Grade 4 learners in the Eastern Cape could not read for meaning (Amnesty International Citation2020). Students from poor households with lack of running water and flush toilets performed poorly which is an indication that high poverty levels are a hindrance to education attainment. Biney, Selebalo, and Borman (Citation2021), Roodt (Citation2018) and Daniel (Citation2021) highlighted infrastructure problems such as access to water and sanitation and classrooms in rural schools as one of the reasons for poor school performance and low average years of schooling.

Despite the reduction in poverty levels in South Africa between the period 2001 and 2016, the number of people with incomes below the poverty line remains high. Furthermore, poverty levels have been on an upward trajectory between 2011 and 2016 (World Bank Citation2018). The Eastern Cape has one of the highest provincial poverty levels with a multidimensional poverty rate of 12.7% recorded in 2016 (StatsSA Citation2017). According to StatsSA, high inequality has been one of the major determinants of the high poverty rate (StatsSA Citation2019b).

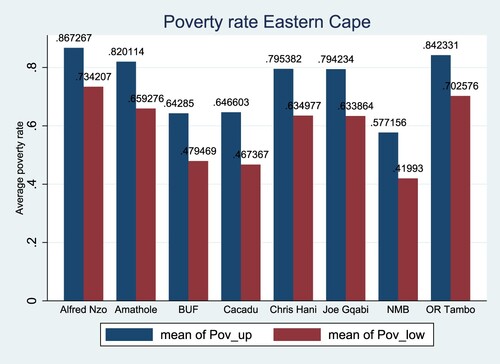

shows that during the period 1996–2018, poverty levels have been higher in Alfred Nzo, OR Tambo and Amathole districts. This finding is similar to that of the World Bank (Citation2018). Poverty rates in the metros and Cacadu are significantly lower due to higher economic activity. Furthermore, the three regions have higher education attainment levels.

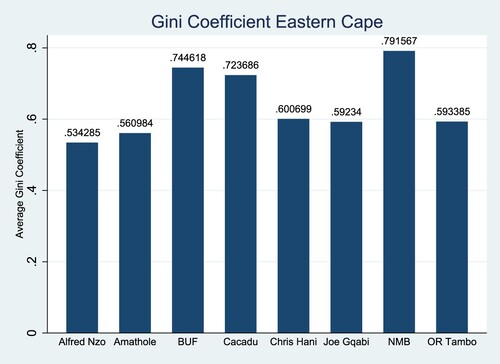

shows that inequality is higher in areas with higher economic activity and higher levels of education attainment. This can be explained by the migration of individuals from the rural communities to the metros in search of opportunities. Furthermore, this could be an indication of education inequality which has been a major challenge in the Eastern Cape and South Africa as a whole (Amnesty International Citation2020). Inequality can be traced to the distinction between no-fee and fee schools. As stated earlier, the Eastern Cape has the largest number of no-fee schools in South Africa which has contributed to the rise in inequality in education. Fee schools have resources to improve the quality of education through hiring more teachers and improving schooling infrastructure compared to the no-fee schools (International Monetary Fund Citation2020).

4. Data and methodology

4.1. Data properties

The data used for the empirical analysis in the study is obtained from ‘Quantec Easy data’ and covers the period 1993–2019. The sample selection is based on the availability of data.

Descriptive statistics are shown in . The average for mean years of schooling in the Eastern Cape is 6.65 which is significantly lower than the South African average recorded during the same period of just below 8 years. This is indicative of the low levels of human capital which have hindered the achievement of the socio-economic goals in the province. The Gini coefficient averages 0.643 which signifies high inequality in the Eastern Cape. Close to 60% of the population earns an income below the lower-bound poverty line. When using the upper-bound poverty line, the figure increases to just below 75%. The descriptive statistics show that ELECT, TRADE, INV, DISP and GNI have large standard deviations, and thus will be used in logarithmic form in the regression models.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Cross-sectional dependence is a phenomenon common with panel data especially when the number of cross-sectional units, N, is small (Pesaran Citation2004). This study contains only eight cross-sectional units and therefore, testing for cross-sectional dependence is necessary. The cross-sectional dependence test proposed by Pesaran (Citation2004) is employed in the study. shows the presence of cross-sectional dependence as the null of independence is rejected at the 1% level of significance.

Table 2. Cross-sectional dependence test.

The presence of cross-sectional dependence renders inappropriate the conventional unit root tests used to determine the order of integration of variables. As such the Pesaran (Citation2007), CIPS unit root test is utilized. The results of the test shown in and , suggest that the variables are either stationary in levels or at first difference. HC, ELECT and INV are stationary at level while the rest of the variables are stationary at first difference.

Table 3. Pesaran (Citation2007) CIPS unit root test: Levels.

Table 4. Pesaran (Citation2007) CIPS unit root test: First difference.

4.2. Methodology

The study estimates two specifications, the first of which examines the effect of human capital on poverty. In the second equation inequality will be dependent on human capital. The human capital-poverty nexus can be specified as follows:

(3)

(3)

Shyu (Citation2014) showed that electricity consumption is a crucial determinant of human development and poverty reduction. Trade contributes to poverty alleviation through the increase in employment, wages and standards of living (Santos-Paulino Citation2017). However, Topalova (Citation2007) suggests that trade openness may not have an impact on poverty alleviation in areas with labour immobility. Gross fixed capital formation is included as an independent variable to capture the effect of investments in infrastructure, technological development, on poverty (Thorat and Fan Citation2007). The unemployment rate is expected to be positively related to poverty as incomes decline (Meo et al. Citation2018). Life expectancy is an indicator of the health status of the population. The variable is expected to have a negative coefficient as health contributes to poverty by decreasing productivity, employment and income (Arsani, Ario, and Ramadhan Citation2020).

The human capital and inequality equation is presented as follows:

(4)

(4)

Trade is expected to have an ambiguous effect on inequality. Its impact on inequality is dependent on labour mobility, earnings and employment Pavcnik (Citation2017). GNP per capita is included to capture the Kuznets Inverted U-curve hypothesis that states that economic growth may increase inequality initially, however, over time inequality is expected to decline (Bahmani-Oskooee and Gelan Citation2008). Investment is expected to reduce inequality through its effect on economic growth (Hooper, Peters, and Pintus Citation2017). Unemployment is introduced as a control variable in line with Furceri and Ostry (Citation2019) who found that the variable is a significant determinant of income inequality.

The study adopts the panel approach for the empirical analysis due to a short time series dataset. . The panel approach has the advantage of improved estimation precision due to a large number of observations and degrees of freedom (Baltagi Citation2005). The cross-sectional units in the panel are the eight major regions in the Eastern Cape which include the two metros and the six districts. As a result of the cross-sectional dependence detected, the panel data techniques such as the Pooled OLS, Fixed Effects (FE) and Random Effects (RE) are not appropriate for the analysis (Henningsen and Henningsen Citation2019; Lau et al. Citation2019). These will be presented for comparison purposes in the study. The Pooled Mean Group (PMG) estimator is more robust compared to the above-mentioned techniques in the presence of cross-sectional dependence and thus is utilized in the study (Lau et al. Citation2019). The PMG estimator was developed by Pesaran, Shin, and Smith (Citation1999) and assumes homogenous long-run coefficients. The estimator can be used with variables integrated of orders zero or one. Prior to the estimation by the PMG technique, the Kao (Citation1999) test is employed to test for cointegration. Cointegration is detected in all the models as shown in , which supports the use of the PMG technique. For robustness purposes, the study employs the Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS) technique. The FGLS technique can be estimated in the presence of first-order autocorrelation in panels as well as heteroscedastic errors (Greene Citation2018).

Table 5. Empirical results.

As a delimitation of the study, it should be noted that as much as regression does not imply causation on its own, the regression models in the study are based on theoretical considerations. Furthermore, according to Wooldridge (Citation2016), the ceteris paribus notion in economics and econometrics allows us to analyse the causal effect. However, to identify causation, the inclusion of controls variables is of utmost importance. This approach has been adopted in the empirical analysis of this study.

5. Empirical results

The results of the PMG estimations shown in indicate that human capital has a negative effect on poverty (for both lower and upper bound levels). An extra year of education has a larger effect on the lower bound poverty rate. The result is supported by findings of Ali and Ahmad (Citation2013), Janjua and Kamal (Citation2014) and David et al. (Citation2018). The Eastern Cape has a low average of mean years of schooling and one of the highest poverty rates in South Africa. Therefore, promoting human capital is of utmost importance in order to ensure more inclusivity of the economy. Access to electricity reduces poverty levels which is in line with theoretical expectations. Access to electricity and other services such as water and sanitation, is crucial for human development and the reduction in poverty. The Eastern Cape is largely a rural province with significant part of the population still without access to electricity and water. Access to essential services is one of the factors that have impacted negatively on the quality of education.

Unemployment increases poverty as indicated by the positive and significant coefficient. The effect of unemployment is similar for individuals below both the lower and upper bound poverty lines. High unemployment has been a major problem for Eastern Cape and South Africa as a whole. This has hindered efforts made to eradicate poverty as a substantial number of people are not able to participate in the economy. Investment and trade have a positive effect on poverty for those below the lower bound. Investment in infrastructure is expected to grow the economy which in turn should reduce poverty, while trade is expected to foster technological development and create employment. However, possibly due to high inequality, investments in infrastructure and the subsequent economic growth only benefit well-off individuals. Ensuring growth and development is inclusive is of paramount importance. GNI has an insignificant effect on poverty which could be a result of the low income in the province.

The error correction term is negative and significant which is an indication of model stability. The short-run coefficients are in line with those of the long-run. Human capital retains its negative and significant coefficient. Investment maintains its positive coefficient, while GNI is negatively signed and significant. The coefficients of access to electricity and unemployment are insignificant in the short-run.

The PMG results for the human capital-inequality nexus are also shown in . Human capital increases income inequality in line with the composition effect outlined by Knight and Sabot (Citation1983). The finding is supported by those of Lam, Finn, and Leibbrandt (Citation2015) and Castelló-Climent and Doménech (Citation2021) who suggested that higher returns to education at high levels hinder the achievement of income equality. The result is supported by the trends in the data as inequality has been on an upward trend since the early 1990s despite the increase in the mean years of schooling. The problems of inequality in schooling seem to be a challenge for the province with a significant proportion of the students receiving low-quality education which perpetuates poverty traps. This finding is in line with those of Lee and Lee (Citation2018) and Yang and Qiu (Citation2016). Access to electricity is associated with higher inequality levels, which is against a priori expectations. However, it should be noted that the increase in the number of people with access to water and electricity in the province has coincided with an increase in inequality.

The negative coefficient of unemployment is not in line with theoretical expectations as higher unemployment is expected to impact positively on inequality. The negative effect could be caused by the unequal opportunities for employment in the province. Employment opportunities are more accessible to skilled and well-off individuals compared to the unskilled. Therefore, as unemployment increases inequality declines. In order for employment creation to reduce inequality, the opportunities for employment should spread across the population. GNI reduces inequality in the long run as shown by the negative coefficient. The result is in line with the Kuznets inverted U-curve which suggests that economic growth may increase inequality initially but reduces it eventually. Trade and investment have a negative effect on inequality, suggesting that infrastructure improvements and technological diffusion are vital for efforts to reduce inequality. The error correction term is negative and significant as expected. In the short run, unemployment and GNI retain their negative coefficients. However, trade and investment are positive and significant. In the short term both variables may cause alterations or disruptions in the economy that may cause inequality to rise.

presents results of the FGLS technique, which support those of the PMG. Therefore, the empirical results of the PMG technique are robust. The human capital coefficient in the poverty specification retains its negative coefficient. The positive effect of human capital on human capital is also found when the FGLS technique is used. The signs of the control variables are also in line with those of the PMG technique to a large extent.

Table 6. Robustness checks.

6. Conclusion and recommendations

Human capital formation has been prioritized worldwide due to the changing nature of the world economy driven by technological advancements. Economies have become more knowledge-based with skills and innovation vital for future economic development. South Africa and in particular the Eastern Cape, has been negatively affected by low levels of human capital. Low quality basic and secondary education, and high poverty levels have prevented investments in post-school education. Furthermore, low levels of human capital have contributed to high inequality and poverty levels. The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of human capital (measured by education attainment) on poverty and inequality in the Eastern Cape province, using the PMG technique.

The results of the study showed that human capital reduces poverty levels in line with a priori expectations. Human capital increases inequality which is contrary to expectations as education attainment is viewed as a tool to reduce inequality. This supports the notion that educational inequality has contributed to the rise in income inequality as individuals from poor households are only able to access lower-quality education. Low-quality education especially from no-fee schools contributes to low education progression rates and impacts negatively on employment.

Several recommendations can be drawn from the study. Inequality in schools should be reduced in order achieve the socio-economic goals of poverty alleviation and inequality reduction. A significant proportion of the population (poor households) is only able to access low-quality education from no-fee schools which often struggle to attract teachers. Despite the large amounts of government expenditures on education, a large number of schools lack adequate infrastructure and basic services such as running water, sanitation, electricity and libraries. Furthermore, a significant number of school buildings are outdated and in need of renovations. There is a need for monitoring and evaluation of expenditure in education to ensure effectiveness. The country should be able to achieve education outcomes commensurate with the expenditures (Centre for Development and Enterprise Citation2017).

Community involvement in improving the quality of schools is of utmost importance. The post-apartheid education policies that involved enhancing school choice have contributed to the rise in inequality in education (Ndimande Citation2016; Msila Citation2011). The wealthy and middle-class have the means to send their children to higher-quality schools whilst the poor have had to contend with low-quality schools (Sayed Citation2016). The involvement of parents, businesses and the broader community is important for the development of plans and procedures to shape the quality of education. Policies such as school choice usually perpetuate inequalities by driving a wedge between community members of different classes, which often leaves low-quality schools neglected.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Eastern Cape Socio Economic Consultative Council (ECSECC) in their collaboration with the Department of Economics at Nelson Mandela University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Eastern Cape comprises on two metropolitan (metro) municipalities namely Nelson Mandela Bay and Buffalo City and six district municipalities, Alfred Nzo, Amathole, Cacadu, Chris Hani, Joe Gqabi and OR Tambo.

References

- Abdullah, Abdul, Hristos Doucouliagos, and Elizabeth Manning. 2015. “Does Education Reduce Income Inequality? A Meta-Regression Analysis.” Journal of Economic Surveys 29 (2): 301–316.

- Abrigo, Michael R. M., Sang-Hyop Lee, and Donghyun Park. 2018. “Human Capital Spending, Inequality, and Growth in Middle-Income Asia.” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 54 (6): 1285–1303. doi:10.1080/1540496X.2017.1422721.

- Ali, Sharafat, and Najid Ahmad. 2013. “Human Capital and Poverty in Pakistan: Evidence from the Punjab Province.” European Journal of Science and Public Policy 11: 36–41.

- Altiner, Ali, and Yilmaz Toktas. 2017. “Relationship Between Human Capital and Economic Growth: An Application to Developing Countries.” Eurasian Journal of Economics and Finance 5 (3): 87–98.

- Amnesty International. 2020. “Broken and Unequal: The State of Education in South Africa.” Peter Benenson House London.

- Arias, Rafael, Gregorio Giménez, and Leonardo Sanchez. 2016. “Impact of Education on Poverty Reduction in Costa Rica: A Regional and Urban-Rural Analysis.” Contemporary Rural Social Work Journal 8 (1): 3.

- Arsani, Ade Marsinta, Bugi Ario, and Al Fitra Ramadhan. 2020. “Impact of Education on Poverty and Health: Evidence from Indonesia.” Economics Development Analysis Journal 9 (1): 87–96.

- Attanasio, Orazio, Costas Meghir, Emily Nix, and Francesca Salvati. 2017. “Human Capital Growth and Poverty: Evidence from Ethiopia and Peru.” Review of Economic Dynamics 25: 234–259.

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M., and A. Gelan. 2008. “Kuznets Inverted-U Hypothesis Revisited: A Time-Series Approach Using US Data.” Applied Economics Letters 15 (9): 677–681. doi:10.1080/13504850600749040.

- Baltagi, B. H. 2005. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data. Chichester: Wiley.

- Becker, Gary S. 1962. “Investment in Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis.” Journal of Political Economy 70 (5, Part 2): 9–49.

- Bhorat, Haroon, Aalia Cassim, and David Tseng. 2016. “Higher Education, Employment and Economic Growth: Exploring the Interactions.” Development Southern Africa 33 (3): 312–327.

- Biney, Elizabeth, Hopolang Selebalo, and Jane Borman. 2021. “A Perfect Storm: The Struggle for School Infrastructure in the Eastern Cape.” News24, 08 April 2021. https://www.news24.com/news24/columnists/guestcolumn/opinion-a-perfect-storm-the-struggle-for-school-infrastructure-in-the-eastern-cape-20210408.

- Castelló-Climent, Amparo, and Rafael Doménech. 2021. “Human Capital and Income Inequality Revisited.” Education Economics 29 (2): 194–212. doi:10.1080/09645292.2020.1870936.

- Centre for Development and Enterprise. 2017. “No Longer Business as Usual: Private Sector Efforts to Improve Schooling in South Africa.” Accessed 23 June 2021.

- Ceroni, Carlotta Berti. 2001. “Poverty Traps and Human Capital Accumulation.” Economica 68 (270): 203–219.

- Chani, Muhammad Irfan, Sajjad Ahmad Jan, Zahid Pervaiz, and Amatul R. Chaudhary. 2014. “Human Capital Inequality and Income Inequality: Testing for Causality.” Quality & Quantity 48 (1): 149–156. doi:10.1007/s11135-012-9755-7.

- Chiswick, Barry R. 1968. “The Average Level of Schooling and the Intra-Regional Inequality of Income: A Clarification.” The American Economic Review 58 (3): 495–500.

- Chiswick, Barry R. 2003. “Jacob Mincer, Experience and the Distribution of Earnings.” Review of Economics of the Household 1 (4): 343–361.

- Coady, David, and Allan Dizioli. 2018. “Income Inequality and Education Revisited: Persistence, Endogeneity and Heterogeneity.” Applied Economics 50 (25): 2747–2761.

- Collin, Matthew, and David N Weil. 2020. “The Effect of Increasing Human Capital Investment on Economic Growth and Poverty: A Simulation Exercise.” Journal of Human Capital 14 (1): 43–83.

- Daniel, Luke. 2021. “99% of Public Schools in the Eastern Cape Aren’t Properly Fenced – and Pit Latrines Abound.” Business Insider South Africa, 03 March 2021. https://www.businessinsider.co.za/99-of-public-schools-in-the-eastern-cape-arent-properly-fenced-and-pit-latrines-abound-2021-5.

- David, Anda, Nathalie Guilbert, Nobuaki Hamaguchi, Yudai Higashi, Hiroyuki Hino, Murray Leibbrandt, and Muna Shifa. 2018. “Spatial Poverty and Inequality in South Africa: A municipality level analysis.” Working Paper 221. http://hdl.handle.net/11090/902.

- Eberhardt, M. 2011a. XTCD: Stata Module to Investigate Variable/Residual Cross-Section Dependence. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:boc:bocode:s457237.

- Eberhardt, M. 2011b. MULTIPURT: Stata Module to Run 1st and 2nd Generation Panel Unit Root Tests for Multiple Variables and Lags. Statistical Software Components. Boston College Department of Economics. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457239.html.

- Furceri, Davide, and Jonathan D Ostry. 2019. “Robust Determinants of Income Inequality.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 35 (3): 490–517.

- Galor, Oded, and Daniel Tsiddon. 1997. “Technological Progress, Mobility, and Economic Growth.” The American Economic Review 87 (3): 363–382.

- Galor, Oded, and Joseph Zeira. 1988. Income Distribution and Investment in Human Capital: Macroeconomic Implications. Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Department of Economics.

- Galor, Oded, and Joseph Zeira. 1993. “Income Distribution and Macroeconomics.” The Review of Economic Studies 60 (1): 35–52.

- Greene, W. H. 2018. Econometric Analysis, 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

- Gregorio, Jose De, and Jong–Wha Lee. 2002. “Education and Income Inequality: New Evidence from Cross-Country Data.” Review of Income and Wealth 48 (3): 395–416.

- Gruber, Lloyd, and Stephen Kosack. 2014. “The Tertiary Tilt: Education and Inequality in the Developing World.” World Development 54: 253–272.

- Hai, Rong, and James J. Heckman. 2017. “Inequality in Human Capital and Endogenous Credit Constraints.” Review of Economic Dynamics 25: 4–36. doi:10.1016/j.red.2017.01.001.

- Henningsen, Arne, and Géraldine Henningsen. 2019. “Chapter 12 – Analysis of Panel Data Using R.” In Panel Data Econometrics, edited by Mike Tsionas, 345–396. Cambridge: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2017-0-01562-8.

- Hong, Philip Young P, and Shanta Pandey. 2007. “Human Capital as Structural Vulnerability of US Poverty.” Equal Opportunities International 26 (1): 18–43.

- Hooper, Emma, Sanjay Peters, and Patrick Pintus. 2017. “To What Extent Can Long-Term Investment in Infrastructure Reduce Inequality?”. Banque de France Working Paper No. 624. doi: http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2952365.

- International Monetary Fund. 2020. South Africa July 2020 Request for Purchase Under the Rapid Financing Instrument – Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for South Africa. In IMF Country Report No. 20/226. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund (IMF).

- Ismail, Rahmah, and Ishak Yussof. 2010. “Human Capital and Income Distribution in Malaysia: A Case Study.” Journal of Economic Cooperation & Development 31 (2): 25–46.

- Janjua, Pervez Zamurrad, and Usman Ahmed Kamal. 2014. “The Role of Education and Health in Poverty Alleviation a Cross Country Analysis.” Journal of Economics, Management and Trade 4 (6): 896–924.

- Kao, Chihwa. 1999. “Spurious Regression and Residual-Based Tests for Cointegration in Panel Data.” Journal of Econometrics 90 (1): 1–44.

- Karambakuwa, Roseline Tapuwa, Ronney Ncwadi, and Andrew Phiri. 2020. “The Human Capital–Economic Growth Nexus in SSA Countries: What Can Strengthen the Relationship?” International Journal of Social Economics 47 (9): 1143–1159. doi:10.1108/IJSE-08-2019-0515.

- Keese, Mark, and Jee Peng Tan. 2013. “Indicators of Skills for Employment and Productivity: A Conceptual Framework and Approach for Low Income Countries.” A report for the Human Resource development pillar of the G20 multi action plan on development. OCDE.

- Knight, John B, and Richard H Sabot. 1983. “Educational Expansion and the Kuznets Effect.” The American Economic Review 73 (5): 1132–1136.

- Lam, David, Arden Finn, and Murray Leibbrandt. 2015. “Schooling Inequality, Returns to Schooling, and Earnings Inequality: Evidence from Brazil and South Africa.” WIDER Working Paper.

- Lau, Lin-Sea, Cheong-Fatt Ng, Siew-Pong Cheah, and Chee-Keong Choong. 2019. “Chapter 9 – Panel Data Analysis (Stationarity, Cointegration, and Causality).” In Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC), edited by Burcu Özcan and Ilhan Öztürk, 101–113. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2018-0-00657-X

- Lee, Jong-Wha, and Hanol Lee. 2018. “Human Capital and Income Inequality*.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 23 (4): 554–583. doi:10.1080/13547860.2018.1515002.

- Menezes Filho, Naercio, and Charles Kirschbaum. 2019. “Education and Inequality in Brazil.” In Paths of Inequality in Brazil, edited by Marta Arretche, 69–88. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78184-6.

- Meo, Muhammad Saeed, Vina Javed Khan, Tella Oluwatoba Ibrahim, Shabnam Khan, Shahzad Ali, and Kashif Noor. 2018. “Asymmetric Impact of Inflation and Unemployment on Poverty in Pakistan: New Evidence from Asymmetric ARDL Cointegration.” Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development 28 (4): 295–310.

- Mincer, Jacob. 1957. “A Study of Personal Income Distribution.” PhD diss., Columbia University.

- Msila, Vuyisile. 2011. “School Choice – as if Learners Matter: Black African Learners’ Views on Choosing Schools in South Africa.” Mevlana International Journal of Education (MIJE) 1 (1): 1–14.

- Ndimande, Bekisizwe S. 2016. “Pedagogy of Poverty: School Choice and Inequalities in Post-Apartheid South Africa.” Global Education Review 3 (2): 33–49.

- Ogundari, Kolawole, and Titus Awokuse. 2018. “Human Capital Contribution to Economic Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Does Health Status Matter More Than Education?” Economic Analysis and Policy 58: 131–140. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2018.02.001.

- Pavcnik, Nina. 2017. “The Impact of Trade on Inequality in Developing Countries.” National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper 23878. doi:10.3386/w23878.

- Pesaran, H. M. 2004. “General Diagnostic Tests for Cross-Sectional Dependence in Panels.” University of Cambridge, Cambridge Working Papers in Economics 435.

- Pesaran, M. Hashem. 2007. “A Simple Panel Unit Root Test in the Presence of Cross-Section Dependence.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 22 (2): 265–312. doi:10.1002/jae.951.

- Pesaran, M. Hashem, Yongcheol Shin, and Ron P. Smith. 1999. “Pooled Mean Group Estimation of Dynamic Heterogeneous Panels.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 94 (446): 621–634. doi:10.2307/2670182.

- Republic of South Africa. 2014. “Eastern Cape Vision 2030 Provincial Development Plan: Flourishing People in a Thriving Province.” Eastern Cape Planning Commission.

- Roodt, Marius. 2018. “The South African Education Crisis: Giving Power Back to Parents.” South African Institute of Race Relations.

- Santos-Paulino, Amelia U. 2017. “Estimating the Impact of Trade Specialization and Trade Policy on Poverty in Developing Countries.” The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 26 (6): 693–711.

- Sayed, Yusuf. 2016. “The Governance of Public Schooling in South Africa and the Middle Class: Social Solidarity for the Public Good Versus Class Interest.” Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa 91 (1): 84–105.

- Schultz, Theodore W. 1961. “Investment in Human Capital.” The American Economic Review 51 (1): 1–17.

- Shimeles, Abebe, and Tiguene Nabassaga. 2018. “Why Is Inequality High in Africa?” Journal of African Economies 27 (1): 108–126.

- Shyu, Chian-Woei. 2014. “Ensuring Access to Electricity and Minimum Basic Electricity Needs as a Goal for the Post-MDG Development Agenda After 2015.” Energy for Sustainable Development 19: 29–38.

- StatsSA. 2017. “Poverty Trends in South Africa: An Examination of Absolute Poverty between 2006 and 2015.” Report No. 03-10-06. Accessed 10 April 2021.

- StatsSA. 2019a. Education Series Volume V: Higher Education and Skills in South Africa, 2017. Accessed 15 March 2021.

- StatsSA. 2019b. Inequality Trends in South Africa: A Multidimensional Diagnostic of Inequality. (Report No. 03-10-19). Accessed 20 May 2021.

- StatsSA. 2020a. Education Series Volume VI: Education and Labour Market Outcomes in South Africa, 2018. Accessed 10 January 2021.

- StatsSA. 2020b. General Household Survey 2019. 20. Accessed 20 February 2021.

- Tchamyou, Vanessa Simen. 2020. “Education, Lifelong Learning, Inequality and Financial Access: Evidence from African Countries.” Contemporary Social Science 15 (1): 7–25.

- Thorat, Sukhadeo, and Shenggen Fan. 2007. “Public Investment and Poverty Reduction: Lessons from China and India.” Economic and Political Weekly 42 (8): 704–710.

- Topalova, Petia. 2007. “Trade Liberalization, Poverty and Inequality: Evidence from Indian Districts.” In Globalization and Poverty, edited by Ann Harrison, 291–336. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/9780226318004

- Wooldridge, J. M. 2016. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. Boston: Cengage learning

- Winters, Paul Conal, and Vera Chiodi. 2011. “Human Capital Investment and Long-Term Poverty Reduction in Rural Mexico.” Journal of International Development 23 (4): 515–538.

- World Bank. 2018. “Overcoming Poverty and Inequality in South Africa: An Assessment of Drivers, Constraints and Opportunities.” Washington, DC.: World Bank.

- World Bank. 2020. “The Human Capital Index 2020 Update: Human capital in the Time of COVID-19.” Washinton DC.: World Bank.

- World Economic Forum, and PricewaterhouseCoopers. 2021. “Upskilling for Shared Prosperity.” Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Yang, Juan, and Muyuan Qiu. 2016. “The Impact of Education on Income Inequality and Intergenerational Mobility.” China Economic Review 37: 110–125.

- Zhang, Huafeng. 2014. “The Poverty Trap of Education: Education – Poverty Connections in Western China.” International Journal of Educational Development 38: 47–58.