ABSTRACT

Qatar has experienced rapid economic development in recent decades and has made large investments in the education sector to improve learning outcomes. The Qatar National Vision of 2030 also aspires to encourage life-long learning, one enabler of which is fostering a reading culture. This paper assesses one program that has aimed to enable this change and the modalities it employs, thereby contributing evidence regarding this under-studied country within rapid transition. The evidence suggests that the majority of children who participate in the program significantly improve their attitude toward reading without any gendered differences. The findings also show that compared to before joining the program, the majority of participating children spend more time reading, and the majority of parents spend more time reading with/to their children. However, these positive behavioral changes are not experienced by all children or parents. We also explore key barriers to change, relating to time limitations, challenges related to technology, and individual difficulties. Based on this case study assessment, recommendations are offered to enhance the activities of the program, particularly regarding barriers as well as for expanding the coverage of the program and broadening inclusion.

Introduction

Qatar has experienced rapid economic growth and development in the last two decades. In 2008, the government published the Qatar National Vision 2030, which aimed to guide the future of the country. The vision has four pillars: human development, social development, economic development, and environmental development (General Secretariat for Development Planning Citation2008). Alongside the aim to have a world-class education system, the vision also aspires to have supportive opportunities that enable each person to fulfill their potential, including offering accessible life-long learning programs. While rapid improvements have been made in the education system, progress on life-long learning has been slower (UNDP and MBRF, Citation2016). One of the initiatives to enable a life-long learning culture is to foster a reading culture, which differs from educational outcomes and educational attainment in that it focuses on the interest and priority that the public places on reading as a leisure activity. Qatar Reads is one community intervention that aims to do just that, and this paper analyzes the program and the behavioral changes it has fostered in making progress toward this goal. Within this unique sociocultural and socioeconomic context, wherein a rapid transformation has taken place, this study provides evidence about how a reading culture can be enabled.

This quantitative study of program participants finds that children within the Qatar Reads program significantly improve their attitude toward reading without showing any gendered differences in the results. The study finds that after joining the program, children spend more time reading, and parents spend more time reading with/to their children. A subset of survey respondents reported no change in behavior, which we analyze in relation to reported barriers. The structure of the paper is as follows: A description of the Qatar Reads program, followed by a review of relevant literature from Qatar in order to contextualize the evidence with what is known from available research. The Findings section outlines an analysis of parts of the survey data, as relevant to the research questions raised in this paper and based upon which a Discussion section presents recommendations for Qatar Reads. While this research contributes to our understanding of reading practices and how community programs such as Qatar Reads can foster a culture of reading, the survey participants are not a representative sample of the citizen or total population. Further study is needed to assess the generalizability of these results, particularly as the participated population has higher than average educational attainment and exhibits a positive interest in leisure reading (by signing up for the program).

Evidence base: Qatar and global context

With the limited available studies, family reading habits in Qatar have been mostly discussed under the broader subject of family literacy. The existing literature on family literacy in Qatar can be divided into: (1) studies that investigate the effectiveness of reading programs in supporting children’s literacy development (e.g. Al-Maadadi et al. Citation2017; Ihmeideh and Al-Maadadi Citation2020; Nasser Citation2013) and (2) studies that investigate reading interests and practices (e.g. Bendriss and Golkowska Citation2011; Chiu Citation2018; Morsy Citation2016). We begin with the former, as Qatar Reads fits within this general category of activity and integrate the broader studies where we find most relevant (particularly comparing evidence from the Global North and Global South). Notably, no literature focuses on Qatar Reads, emphasizing the unique contribution of this paper on the role of a non-governmental organization in fostering a reading culture in a rapidly developing context.

The study conducted by Al-Maadadi et al. (Citation2017) was concerned with children’s literacy acquisition and the family’s role in this regard at the pre-school level. The research focused on evaluating family literacy programs (FLPs) implemented in two selected kindergartens and exploring the perceptions and practices of such programs among the teachers and parents who participated. The study results indicated that the outcomes of FLPs in developing children’s reading and writing skills were satisfying as per the teachers and parents. The findings were consistent with previous studies on the family’s influential role in promoting children’s literacy skills (we discuss divergences on the influences below, however, Al-Maadadi et al. cite: Levine Citation2002; Hannon Citation1998). With regard to Qatar in particular and family reading habits, the teachers in the study revealed that FLPs assisted in overcoming a number of challenges related to certain family practices at home, such as the parents’ lack of interest in reading books to their children. The noted programs provided teachers with strategies on how to support parents in this regard by providing them with a list of suggested literature to be read to children in addition to other home-based literacy activities (Al-Maadadi et al. Citation2017). This important paper by Al-Maadadi et al., while open access, is not published in a journal indexed on Scopus or Web of Science, highlighting the importance of broadening literature search methods.

Ihmeideh and Al-Maadadi (Citation2020) carried out an experimental study, also focused on early literacy in kindergarten settings, to assess the effectiveness of FLPs on developing children’s literacy learning. The study involved an experiment group and a control group. The findings revealed that the performance of the experiment group, which included children whose parents have participated in FLPs, was significantly better than the control group's performance, which indicates that the FLPs that were implemented have had a positive impact on children’s early literacy skills. There were no gendered differences in these positive impacts. The results also highlighted that the programs assisted in raising parents’ awareness of their role in supporting their children’s literacy learning (Ihmeideh and Al-Maadadi Citation2020).

The evidence contributed by Al-Maadadi et al. (Citation2017) and Ihmeideh and Al-Maadadi (Citation2020) both focus on pre-school ages. The only study that analyses an intervention outside of that age group is a publication by Nasser (Citation2013), which assessed the effectiveness of a two-month extracurricular reading program that was implemented in selected primary schools in Qatar. The activities revolved around a book but included a broad range of engagement mediums, such as art, theater, home economics, reading, and discussions. This study also involved control and treatment groups. One of the areas that were covered by the study is the home literacy practices of the students and parents’ influence on their reading habits, which ‘were used to factor out and control the parents’ influence on students who have participated in the program’ (Nasser Citation2013, 65). The findings suggested that students who were enrolled in the reading program showed higher levels of interest in reading when compared to those who were not enrolled. The study concluded that the reading program assisted in improving students’ reading habits (Nasser Citation2013). As with the study by Al-Maadadi et al. (Citation2017), this unique study by Nasser (Citation2013) is open access but is not published in a journal indexed on Scopus or Web of Science.

The next set of literature we review is specific to Qatar, being related to family reading interests and practices. We present this chronologically as significant change has taken place in Qatar during the most recent decade, including in the education sector (see: Alkhater Citation2016; Zweiri and Al Qawasmi Citation2021). In 2011, Bendriss and Golkowska investigated the role of family involvement and school influence in forming reading habits among Qatari students at the pre-college level. The results indicated that the percentage of students who were told stories by their parents before entering elementary school was low and so was the percentage of students whose parents read to them. In addition, the results showed that the percentage of students who reported that they had seen their parents reading frequently was low. The findings highlighted a link between being read to and forming a habit of reading and argue that these household habits have negatively influenced students’ reading habits (Bendriss and Golkowska Citation2011). This study provides insight into a sort of baseline, of 2011, suggesting (although not a representative sample of the population, only 72 university-aged participants took part), that even amongst these academically high-achieving students, parental reading with children at home was frequent in approximately half of households.

In 2014, Cheema explored the prevalence of online reading activities among 15-year-old students in Qatar, giving consideration in the analysis to demographic factors, socioeconomic status, and the use of computers for school-related activities and entertainment purposes. The results of the study suggested small yet significant mean differences in the prevalence of online reading between males and females. Male students appeared to engage more frequently than female students in online reading activities, such as searching for certain information online and reading emails. Cheema (Citation2014) suggested that a possible explanation for this gendered result is that female students could have spent less time with online reading activities and more time in other literacy areas and activities related to academic achievement, which was posited because of the fact that female students tended to outperform male students in academics. The results also showed that most of the online reading activities by students took place at home, not at school, since the time available for students to work with computers was limited at school (Cheema Citation2014). The relevance of this study is questionable given how much has changed since 2014, particularly the expansion of technology in society and in schools, and the necessity for students to shift online during the pandemic. Nonetheless, the gendered finding is important to note, and it is something we investigate within the analysis below (regarding any differentiated gendered outcomes of the program).

Two of the most recent studies investigate specific populations: the first within a specific school setting (Morsy Citation2016) and the second across a specific age group of grade 4 students (Chiu Citation2018). Morsy’s (Citation2016) study was concerned with investigating reading interests in English among high school students in Qatar. Although the sample was considered a limitation of the study since it only included 30 female students from a secondary school in South Qatar, it provided a number of insights regarding reading habits among adolescents that can be investigated and extended further to other age groups. The results of the study showed that most students, about 70%, had little interest in reading in English, visiting the library and/or reading at home (notably, the author notes that the family’s low interest in reading at home could discourage the student’s reading efforts). Morsy (Citation2016) also suggested that the students’ limited interest to read in English could be due to the load of school assignments coupled with a busy schedule filled with extracurricular activities. It was further concluded that there was a ‘lack of reading habit as an instilled value in students’ and an absence of home libraries which could be reasons for students’ limited interest in reading in English (Morsy Citation2016, 12–13). The consequences of not having home libraries and an unwillingness or lack of interest to borrow from public libraries were also obstacles identified by Qatar Reads in its initial assessment, which was used to inform the program design.

The study that focused on a single age group, a sample of 4th-grade students, was conducted by Chiu in 2018 and investigated the link between family and school attributes and children’s reading attitudes and outcomes. The results revealed that children with more books at home read more frequently, showed better attitudes towards reading, and had higher reading scores. While other literature highlights this in the global context (e.g. Evans et al. Citation2010; Faltisco Citation1952; Hansen Citation1969), having this localized evidence emphasizes the importance of the design of Qatar Reads in building home libraries. Based on this positive correlation, it is noteworthy that Chiu found that 16% of participating students had few books in their homes (10 or less books), regardless of the parents’ high income. Chiu (Citation2018) also found that parents’ education and job status (socioeconomic status, SES) were also positively linked to their child’s reading habits and performance. The children of families with higher SES read more frequently and had better reading attitudes and test scores. Moreover, the study found that the parents’ attitude towards reading affects children’s reading attitude and performance. Children of parents with a positive perception of reading had a similar perception towards reading. The study also highlighted that parental-child home reading activities could assist in enhancing children’s reading ability and their self-conceptualization of being a reader (i.e. children’s perception about their reading ability and their perception about reading difficulty) (Chiu Citation2018).

It is worth mentioning that although family involvement in promoting children’s literacy development is well recognized in the literature (Hannon Citation1998; Timmons and Pelletier Citation2015, as cited in Ihmeideh and Al-Maadadi Citation2020), and although studies on parental involvement in children’s learning in Qatar have highlighted limitations due to lack of time and interest, many of the existing projects and programs promoting children’s literacy development and learning in Qatar are not designed to deliberately include parental or family involvement (Ihmeideh and Al-Maadadi Citation2020). Qatar Reads has a subset of projects, one of which is the focus of this study, the Family Reading Program, designed for children aged 3-13. The evaluation in this study does not cover the entirety of Qatar Reads activities, particularly the other ways in which parents are involved in its activities (e.g. the Mommy to Be program).

Qatar Reads

Qatar Reads is a program piloted by Qatar Foundation (QF), a non-profit organization creating advancements in education and research and driving positive social and human development outcomes since 1996. QF operates within Education City – the flagship of learning and community building – while also host to nine tertiary educational institutions. Through a wide range of wellness-oriented, socio-cultural programs and services, QF aims to unlock human potential and ensure citizens are set up for success. In 2016, QF established the National Reading Campaign – now known as Qatar Reads – to nurture a culture of reading and cultivate a community of knowledge seekers and life-long learners.

Qatar Reads was a direct response to an emerging community need: despite the country’s high literacy rate of 98% (UNDP and MBRF, Citation2016), the practice of reading as part of everyday life and for enhancing personal growth – particularly in Arabic – was lower than expected with issues of social access, family practice, and personal motivations presenting as dominant barriers (UNDP and MBRF, Citation2016). This, against an interesting demographic backdrop where the majority of the population in Qatar are not citizens, created a unique opportunity for a community-based intervention. The program committed to reaching Qatari families – though not exclusively. The immediate aim was to shift norms, behaviors, values, and perceptions, as opposed to increasing any specific literacy or educational outcomes. While in the longer term, these shifts would enable broader socio-cultural development. As of 2021, 370 families were subscribed to the program with roughly 800 children participating. More than 85% of participants are Qatari nationals.

The Qatar Reads program was designed for families with children between the ages of 3 and 13, with each child being placed within one of seven groups (by age range and/or reading level) to ensure the appropriate provision of reading materials. Each participating household receives a Qatar Reads mailbox (a unique feature as there are no post boxes for home mail delivery in Qatar) to which a set of books and accompanying activity sheets are provided on a monthly basis. The materials are available in Arabic and English (as of 2021, the majority of participants, 64%, have opted for bilingual packages, while 14% have selected English-only, and 22% Arabic-only). The modality of Qatar Reads was designed partly on the basis of enhancing the activities of Qatar National Library (also located in Education City) by reaching new target audiences, in this case engaging Qatari nationals. Qatar Reads was also informed by the existing evidence that having home libraries can enable reading practices for children (Evans et al. Citation2010; Faltisco Citation1952; Hansen Citation1969) and can drive positive social change (Nurdin and Saufa Citation2020; Sikora, Evans, and Kelley Citation2019). The program modality acts as a means to support households to have and expand home libraries with age- and level-appropriate materials. Having home libraries at suitable reading levels also supports parents who may read in a different language than their children in the home environment. Alongside the monthly books and activities, Qatar Reads holds events related to monthly thematic topics, providing a further means of engagement, community relationship building, and applied learning.

The Qatar Reads program has a subset of projects, each targeting different populations and outcomes. This includes the Family Reading Program, which is the focus of this paper, and focuses upon the home reading environment and parent–child relationship, as well as creating a community of young readers and families through engaging learning events. Qatar Reads also implements Mommy to Be, which benefits new mothers and provides early learning for newborns. Two other projects that Qatar Reads implements include Read to Lead, which encourages reading among adult professionals, and the School Membership Program, which targets students, teachers, and educational environments. This paper only focuses on participants in the Family Reading Program, future research is needed to explore the outcomes and behavioral changes enabled by other initiatives within Qatar Reads.

Methods

In the summer of 2021, Qatar Reads established a partnership with the College of Public Policy at Hamad Bin Khalifa University (a national university in Qatar housed in Education City) to conduct a research evaluation of the Qatar Reads program. The purpose was two-fold: (1) to assess the behavioral changes enabled by the program to date on participating families, and (2) to provide organizational learning to support program improvements and build a case to scale.

In order to create a robust evidence base for the study, a literature review was first undertaken, at different scales. There is great breadth and depth to research on reading habits among children and youth, far beyond the scope of what this paper can feasibly cover. For the purposes of this study, we focus on two aspects of the literature: relevant academic research conducted in Qatar and the region, which is the focus of the following section, and the global evidence base. This data was obtained using parallel literature searches on Scopus and Google Scholar, the latter identifying additional materials that are not indexed, but provide important context for a country that has not been the subject of vast research studies. Secondly, when analysing the findings of this study, we compare and contrast the results with a selection of relevant evidence from the broader academic literature (integrated within the findings section below). For research within the State of Qatar, few relevant studies were available (using broad search terms and inclusive criteria, nine papers were identified). To expand the scope of the literature review, additional studies were sourced from the Gulf Cooperation Council member countries (adding 23 papers). To learn from global best practices, 72 additional publications were identified, reviewed, and selectively included based on relevance to this study.

A research-based measurement framework helped ground the evaluation and drive focus in both the literature review and the examination of program surveys measuring similar outcomes and indicators that could be used in the development of an initial parent survey. An extensive list of potential survey questions and corresponding metrics was compiled, from which a subset was identified (as per their relationship to the program objectives and research evaluation goals). This data collection tool was developed in collaboration with the Community Development’s Department of Institutional Effectiveness, Qatar Reads, and the Hamad Bin Khalifa University team. The survey was translated from English to Arabic and subsequently reviewed by the Institutional Review Board Ethics Committee of Hamad Bin Khalifa University. Following approval, the survey was piloted. Participant feedback from this process was used to clarify questions and metrics, and also to improve the survey design (administered using Microsoft Forms). The survey was then distributed online to Qatar Reads participant families, for parents to complete on behalf of their child(ren) in the program.

We analyzed the survey data using a combination of descriptive and inferential methods. Descriptive methods included numerical descriptions, charts (bar graphs, pie charts), and cross-tabulation tables. On the inferential side, apart from a pretest for model assumptions such normality test, we employ various methods including Chi-squared test for correlation, and Wilcoxon signed ranks test for assessment.

This study has several limitations, which are worth considering when engaging with the findings and discussion. The first is that the population under study is not a representative sample of the population, but a case study population, as participants within the reading program under assessment. Due to the nature of this data set, we do not have a control group to compare the participant population changes with the non-participant (i.e. there may be other factors or variables beyond the Qatar Reads program that are influencing changes at the population level). The data that this study analyzes are case study analysis of the situation before joining the program and afterward, allowing for internal behavioral change assessment of before and after joining the program. However, in order to factor in the potential broader shifts in the non-participant population, future research could also use a control group. For the purposes of assessing Qatar Reads, our focus is on the changes of participants, while recognizing that these limitations do not allow for population-level generalizations to be made (and which we avoid making). A second limitation is the reliance on self-reported and recall data from participants; while this presents a limitation, since there was no baseline survey conducted at the time of intake into the program, we needed to utilize recall data to undertake the comparative assessment of before and after. A third limitation, which relates to the population included in this study, is that the survey was administered in Arabic and English, but not in other languages spoken (particularly amongst the diverse expatriate population in Qatar). Future research might address this gap by conducting studies for specific population groups, such as for the nationalities that are demographically large in Qatar.

Findings

To address our research questions, a questionnaire was designed and sent to all families in the Qatar Reads Family Reading Program. A total of 65 responses were received from the families who completed the survey on behalf of 106 children. Of the 106 children, 50 were male and 56 were female, with ages ranging from 2 to 13. Children of 4 years and above make up 94% of the sample. In Qatar, primary education continues until Grade 6, followed by preparatory (grades 7–9) and then secondary (grades 10–12). The sample population, therefore, focuses on the pre-school, kindergarten, and primary stages. There is a wide range of literature that identifies influences on children within this age group, and specifically on habits and norms (e.g. role and influence of parents, teachers, peers, media, advertising, environments, etc). Reviewing all of this material is beyond the scope of this study, instead, we focus on those aspects that are linked to Qatar Reads program activities and how they relate to the findings presented.

Of the 65 families who participated in the survey, 58% were Qatari, and 42% were non-Qatari but residents of Qatar. The demographic context of Qatar is unique in that the majority (∼88%) of the population are expatriates, while a minority (∼12%) are citizens. Another unique feature of the population in Qatar is that it is predominantly male; of the 2.5 million residents, 1.85 million are male (72%) and only 15% of the population is below the age of 15 (Planning and Statistics Authority Citation2021). The former is a product of a large, predominantly low-skill, temporary workforce tending to major construction projects (many connected to FIFA 2022), a population that has unique traits and experiences (Diop et al. Citation2019; Khalifa Citation2020) that is not captured in the focus of this study (there are, however, other literacy activities serving this population, such as those offered by Georgetown University in Qatar, the NGO Reach Out to Asia, among others). Given this, population groups who may be interested in, and accessing, the services of Qatar Reads are a specific subset of the population in Qatar.

Qatar Reads aimed, in its design, to be oriented toward enabling citizen participation (e.g. addressing barriers in the delivery modality) while also promoting and preserving the Arabic language (e.g. by offering Arabic books and materials). At the time of the survey, 354 families were enrolled in the Qatar Reads Family Reading Program, and within those families, 823 children were participating (each with individual subscriptions). Of these families, 312 were citizens (88%); a remarkable success in developing a service that attracts the primary target audience. This is particularly notable when compared to other services available in Qatar that seek to enable positive social change regarding reading and reading habits. The Qatar National Library is one such example, which is located within Education City and opened in 2017. While Qatar Reads provides books and activities to homes on a regular basis, the Qatar National Library is a place where books can be read and borrowed. The national library is widely used, particularly considering it is a relatively new institution (e.g. over 30,000 children have a membership). For many expatriates, the public library as an institution and service is not new and the processes of borrowing and returning books are familiar. This partly explains the high user uptake of expatriates, with 92% of all child memberships being expatriates. Conversely, at the Qatar National Library, only a minority (8%) of child memberships are held by Qatari citizens. Qatar Reads offers complementary services, with unique design and implementation modalities that aim to reach different target populations, ones which may not be accessing the Qatar National Library. As the Qatar Reads participation data shows, the program has been very effective at tailoring the program design to align with the needs of the target population: a reflection of its design modalities and effective outreach efforts.

The role of parents in enabling and supporting positive reading habits among children has been the topic of extensive research (e.g. De Graaf, De Graaf, and Kraaykamp Citation2000; Greaney Citation1986; Wollscheid Citation2013). In much of the literature, for example, it is argued that parents reading with children is positively correlated with better educational outcomes (e.g. Ahmad et al. Citation2020), and parental modeling of reading is correlated with higher child reading habits (e.g. McKool Citation1998). This is not always the case, however, particularly in non-western contexts. For example, in Nigeria, a study on reading habits found that parental profession was correlated with positive reading habits more so than parental educational level (Aramide Citation2015). In another example, from Vietnam, educational attainment was associated with improved reading habits, and with the mother’s educational attainment level (Le et al. Citation2019). That study, however, was specific to having a minimum of high school or university, which all study participants in the Qatar Reads data have obtained. As noted in the context section, available national evidence suggests that higher parental education level (and associated socioeconomic status) is correlated with improved child reading habits in Qatar.

For Qatar Reads, educational attainment seems to be less of a factor of differentiation between participants, and more of a factor relating to entry into the program. Of the respondents, 90.6% of families had a parent with college or university education, while only 9.4% (all of whom were citizens) had a high school diploma. There were no participants that did not complete high school. According to World Bank data (World Bank Citation2021), the total population of people who have completed post-secondary education (and who are above the age of 25) in Qatar was 41% in 2017 (latest available data). This may appear surprising, given the high income per capita in Qatar, however, it is explained because this figure is not representative of citizens but of the total population. As far as we are aware, there is no available data on educational attainment specific to citizens. Nonetheless, we can assume that the citizenry has some degree of educational attainment diversity, and those with lower levels of educational attainment are less well represented in this study sample. One reason people with lower educational attainment may not be participating is that the program has a cost of participation (QR 50/month; US$ 14). However, further research with non-participants is required to assess how significant the cost of accessing the program is a barrier to participation. Another reason why participation may be oriented towards those with higher education attainment levels is that participation is reflective of those who seek such services, and less of the general public.

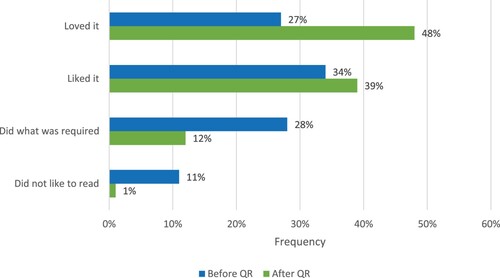

To assess the behavioral changes enabled by the program with regard to children’s reading habits, the survey asked parents about children’s attitudes towards reading before and after joining Qatar Reads. The results presented in are encouraging as there is a significant improvement in every category. Notably, a significant drop is observed among those who ‘did not like to read’, which was 11% before joining the program, a figure that has dropped to 1% after being a participant in Qatar Reads. One level up on the scale, for those who replied that their child ‘did what was required’ was 26% before joining QR, a figure that has fallen to 12% after Qatar Reads. On the positive side, children who ‘loved’ reading after joining QR increased from 27% to 48%. This could be due to the fact that the reading packages are addressed to the children by name, making the selections of the month as a celebratory or special experience. There are also events that take place that bring the books to life, which encourage children to interact with other readers (e.g. tours, exclusive access to planetariums, live storytelling, face painting). Of the families that participated in this survey, and who attended events, 62% reported that events increased their child’s interest in reading ‘a lot’ (on a scale of not really, somewhat). In addition to events, children also obtain extra materials, such as short comics, stickers and more. The short comics are usually the products of local creatives (artists and authors), who reflect on local sites and national heritage. Children are also encouraged to participate in writing competitions to see their work published in the next month’s package and to submit coloring books. These activities create new forms of engagement and motivation for increased participation as well as interest in the books of the month. As one example of the connections children are making with the books, some children even bring their monthly package along with them to the monthly events or dress up according to the monthly theme, while others recreate pictures they receive in the comics to bring stories to life.

Although the analyses above show significant positive changes of the program on children's reading habits, we conducted a statistical test to assess the significance and robustness of the results. To determine an appropriate method, we test whether the data are normally distributed. The null hypothesis for the normality test assumes the presence of normal distribution. We conducted two normality tests: Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) and Shapiro–Wilk (SW). The null hypothesis is rejected by both KS and SW tests, which suggests that data are not normally distributed (those results available not shown here but upon request). Additionally, non-parametric methods are appropriate for assessment as they are robust to non-normal data. Among the non-parametric tests, the Related-samples Wilcoxon signed-rank test is an appropriate method since the variables measured are related (i.e. the same measures are taken from the same subjects before and after the treatment (Qatar Reads program)). Hence, the Wilcoxon method is employed to assess the changes, which can be hypothesized as follows:

Ho: The median of differences between after joining Qatar Reads and before joining Qatar Reads equals 0.

H1: The median of differences between after joining Qatar Reads and before joining Qatar Reads are not equal to 0.

Results presented in suggest that null hypotheses are strongly rejected in favor of alternative hypothesis at a 1% significance level, as the corresponding p-values are smaller than 0.01. In other words, the median difference in a child’s attitudes towards reading before and after joining QR does not equal zero. The children's attitudes have significantly improved after joining the QR program. These results support and strengthen the conclusion from the descriptive analysis above that the Qatar Reads program has enabled significant positive changes on the reading attitudes of children. Parents have also recognized these changes; participants in the survey were asked if they had recommended Qatar Reads to a friend or relative, and 94% reported to have done so.

Table 1. Wilcoxon signed ranks test.

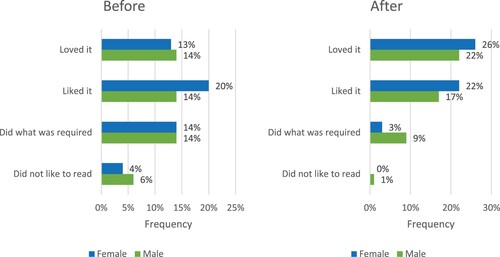

As was noted in the country-specific studies, at least one study found gendered differences in outcomes and impacts. In order to assess the gender dimension of the changes, we conducted a gender analysis in . The results shown in indicate that girls have slightly greater progress in all categories compared to boys. We conducted a Chi-squared test to determine whether these observed differences are different enough for the association between gender and children’s reading habits to be statistically significant. The analysis results (see in appendix) show that there is no statistically significant association as the corresponding asymptotic p-value is greater than 5%. Hence, we can conclude that Qatar Reads has enabled a significant positive change in the reading habits of children, and these changes do not differ significantly by gender. This is an important finding, as it suggests there are no accessibility or content barriers related to gender, as was identified in earlier intervention evaluations. This result is consistent with the findings of Ihmeideh (Citation2014). The results suggest that parents support their children’s reading regardless of their gender. The Qatar Reads program also does not distinguish between genders in reading selections for the subscribers. Male and female protagonists are featured as often as possible in the reading selections and the comics also are selected to be appealing and interesting to both genders (in other words, the program is gender sensitive with regard to content selection and seeks to reduce gendered biases). This is also reflected in the number of girls and boys who are signed up. The divide is almost equal, with 45.6% males and 54.4% females in the program.

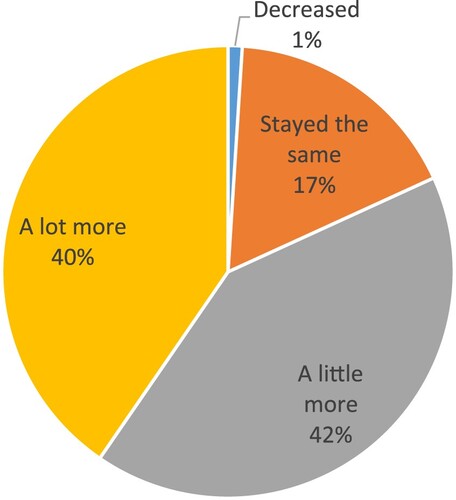

and the statistical tests in suggest that parental assessments of Qatar Reads are positive, without any gender-specific trends. Another contributor to the positive behavioral changes that Qatar Reads has enabled relates to its objective of cultivating a habit or culture of reading. This can be measured by examining how much more time children devoted to reading after participation. shows that for the vast majority of children participating in the program, 81%, their time spent reading has increased, with parents reporting that 41% read ‘a little more’ and 40% doing so ‘a lot more’ compared to before participating in Qatar Reads. In addition to time spent, participants were asked about the increased engagement of their children in the program; 84% said that their child reads all the books provided by Qatar Reads every month ‘most of the time’ or ‘always’, 47% said that their child completes all the activity sheets provided by Qatar Reads each month ‘most of the time’ or ‘always’, and 49% said that their child asks questions or shares thoughts about the books provided by Qatar Reads ‘most of the time’ or ‘always’. The findings thus suggest that while time spent reading has increased, it is occurring in parallel with engagement (activity sheets) as well as interest in the content (asking questions and sharing thoughts).

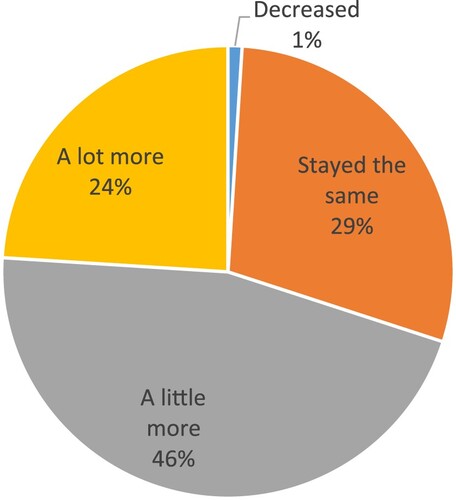

In addition to children reading more themselves, with its family focus Qatar Reads also aims to enable change within households. shows that parental time spent reading with children also increased for the majority, 70% (46% reporting ‘a little more’ and 24% reporting ‘a lot more’), highlighting the transformative change Qatar Reads has on families and their reading habits. There are two key mechanisms that enable increased parent–child interaction and bonding through reading. One, as noted above, is the community engagements, which draw parents into participating in activities with other families. The second are a wide range of guided activities that Qatar Reads provides to build intentional engagement between parent and child. For example, the monthly activity sheets that go to homes also include parental tips, while in other cases the activity sheets are designed to be completed with parents. As another example, the comics include a ‘conversation starter’ box, through which children and their parents can engage in discussions about the topics raised in the materials of the month. Also, having more books at home gives children more opportunities to be asked to be read to.

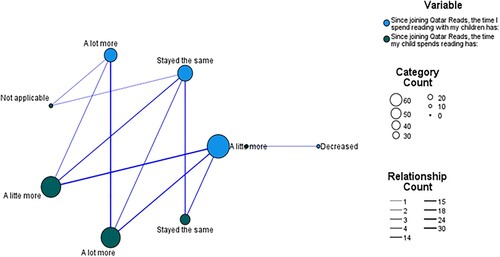

A sub-analysis of and is presented in , in order to better understand the 1% who decreased (it was the same overlapping household, which has discontinued the program) and those who reported child and parental-child reading as ‘stayed the same’ (17% and 29% respectively). This sub-analysis of relationships between responses provides insightful information regarding the connectivity, or overlap, between the two survey questions. The blue circles in represent four categories of the time spent reading with children while the green circles represent four categories of the time children spent reading after joining the program. The lines between the circles map the relationship between the corresponding categories of the two variables. The thickness of the lines represents the strength of the relationship. As such, those who indicated their children read ‘a lot more’ after joining QR are mostly the ones (thicker lines) who read ‘a lot more’ or ‘a little more’ with their children since joining QR. On the other hand, the parents who report the change in children’s time spent reading ‘stayed the same’ are the ones whose time spent reading with their children mostly ‘stayed the same’ after joining the program. However, we also see that the overlap is not complete, meaning that progress has also varied on a child-specific and parent-specific pathway, the full causes of which will require additional qualitative information to ascertain.

One of the reasons that can help explain the child- and parent-specific pathways of positive change (or lack thereof) is an analysis of the listed barriers as to why children are not reading. When the survey asked about barriers, the question was open to multiple answers, meaning that the number of responses exceeds the number of participants (as multiple responses could be entered). Parents were asked to highlight the key barriers for why their children are not reading and/or the reasons that make it challenging for their children to read. In terms of frequency, we classify these answers into three groups: (1) time limitations – as in schoolwork, extracurricular activities, other family activities, with 60 mentions; (2) competition with technology – as in TV, computer, and phone, with 29 mentions; and (3) personal difficulties – as in a lack of interest or difficulty with reading, with 28 mentions. While time limitations are difficult for a program like Qatar Reads to address, a rise in technology addictions amongst children and youth has been noted in Qatar (Doha International Family Institute Citation2021). This is particularly the case with the increased reliance on technology during the pandemic, as most schools in Qatar were fully online for the majority of the 2020–2021 school year. Like the education system, one of the ways Qatar Reads tried to keep active during the pandemic was using online tools. However, one take away lesson from this survey, as well as the broader trends, is that parents and children may need to focus more with offline tools as well as support parents and children with the skills to manage technology usage in more healthy ways. In fact, after the onset of the global pandemic, the first two gatherings were virtual and parents began expressing their interest in finding options to hold physical events instead. Unlike in-person events, which remained popular when they were implemented, virtual attendance was dropping with time – indicating digital fatigue. For example, at one popular in-person event 320 families attended (86% of all participants), however, online events had a maximum of 30 families attending (less than 10%).

Discussion

In a relatively short period of implementation time, including a time period disrupted by a global pandemic, Qatar Reads has been able to improve children’s reading attitudes, increase the amount of time children spend reading, and increase the amount of time parents spend reading with their children. Improvements were not limited to children and/or their parents but were connected to program components (events, activity sheets, resources) which provide diverse ways of engagement as well as relevant and engaging content selection. These results show that changes are occurring beyond individual children, and are indeed making progress in fostering new norms, attitudes, and behaviors within families; in other words, Qatar Reads is enabling a shift toward a reading culture within households. In addition to these positive outcomes, there were no gendered differences in the findings, suggesting that the gender sensitive approach to the content selection and resource development is appropriately including boys and girls in a similarly positive way. The improvement of parent–child engagement also suggests that the resource development, which explicitly takes this into account in the design process, is effectively changing the habits of parents, not just of children. While a majority reported positive change, not all children and parents experienced such. A minority of children and nearly a quarter of parents reported that their reading practices stayed the same as they were when compared to before joining the Qatar Reads program.

Having 370 families and 800 children in a program of this type is an excellent start, to expand these benefits to more families and children the program needs to scale, which could be done in a tailored way. Since the program was designed to reach citizens, the following focuses upon that demographic. The results of this survey specifically suggest that citizens who have completed tertiary education are attracted to joining Qatar Reads, and for this target audience the primary task may be simply expanding general awareness (such as via targeted advertising campaigns). Citizens who have not completed tertiary education are less well represented in the current program participants, for whom an informational approach might be required in order to justify why such a program is an important investment. An example of how the program might reach new audiences is via workplace campaigns (e.g. on relevant dates, such as the International Day of Education or around the start of school holidays when parents might be seeking activities for their children). In parallel to attracting individuals, workplace campaigns might approach employers (e.g. public sector partners such as the Ministry of Education and Higher Education or the Ministry of Culture, or private sector partners such as Ooredoo or Qatar National Bank) to have programs that cover the cost of their staff to join Qatar Reads.

In addition to expanding the number of participants in the program, the survey also highlighted ways in which Qatar Reads can better support those who are already in it. For example, the second most mentioned barrier as to why children are not reading was technology (e.g. technology, TV, computers, phones), as noted above there has been a rise of technology addictions to emphasize this concern. Given this specific barrier, Qatar Reads might develop resources that raise awareness about technology use and the ways in which its use can be limited (using some of the options built into the technologies as well as setting boundaries or limits for their use). The experience with digital Qatar Reads events also signaled the limits of online events for engagement, if and when possible, this should return to the primary means of events.

Conclusion

Providing the support required to have a country of life-long learners requires the involvement of diverse actors. Formal educational settings have an important role to play, as do public institutions such as the national library. In addition, the third sector of non-governmental organizations can make important contributions; Qatar Reads is one example of a program fostering norms change to enhance the culture of reading. Although not a representative sample of the population, the participants in Qatar Reads have made significant attitudinal and behavioral change in a short period of time within the program (in nearly all cases, less than 18 months). The positive changes found in this analysis include children’s improved attitudes toward reading, increased time children spend reading, and increased time parents spend reading with children. A limited amount of research is available regarding reading programs in Qatar, to which this paper makes a contribution. This research highlighted many areas for potential research: some research notes the importance of household traits, and this could be further analyzed; the mapping of specific trends of change for child and parents suggests that qualitative research is needed to better understand the enablers and barriers to change; market assessments could be conducted to support the scaling efforts of Qatar Reads in order to better understand what draws people, particularly those not inclined to such a program, to join; why certain programs appeal to some people over others and/or how those selection processes take place.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmad, Z., M. Tariq, M. S. Chaudhry, and M. Ramzan. 2020. “Parent's Role in Promoting Reading Habits among Children: An Empirical Examination.” Library Philosophy and Practice, 3958: 1–21.

- Al-Maadadi, F., F. Ihmeideh, M. Al-Falasi, C. Coughlin, and T. Al-Thani. 2017. “Family Literacy Programs in Qatar: Teachers’ and Parents’ Perceptions and Practices.” Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology 7 (1): 283–296.

- Alkhater, L. R. M. 2016. “Qatar’s Borrowed K-12 Education Reform in Context.” In Policy-Making in a Transformative State: The Case of Qatar, edited by M. E. Tok, L. Alkhater, and L. A. Pal, 97–130. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Aramide, K. A. 2015. “Effect of Parental Background Factors on Reading Habits of Secondary School Students in Ogun State.” Nigeria. Journal of Applied Information Science and Technology 8 (1): 70–80.

- Bendriss, R., and K. Golkowska. 2011. “Early Reading Habits and Their Impact on the Reading Literacy of Qatari Undergraduate Students.” Arab World English Journal 2 (4): 37–75.

- Cheema, J. 2014. “Prevalence of Online Reading Among High School Students in Qatar: Evidence from the Programme for International Student Assessment 2009.” International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology 10 (1): 41–54.

- Chiu, M. 2018. “Qatar Family, School, and Child Effects on Reading.” International Journal of Comparative Education and Development 20 (2): 113–127.

- De Graaf, N. D., P. M. De Graaf, and G. Kraaykamp. 2000. “Parental Cultural Capital and Educational Attainment in the Netherlands: A Refinement of the Cultural Capital Perspective.” Sociology of Education 73 (2): 92–111.

- Diop, A., S. Al-Ali Mustafa, M. Ewers, and T. K. Le. 2019. “Welfare Index of Migrant Workers in the Gulf: The Case of Qatar.” International Migration 58 (4): 140–153.

- Doha International Family Institute. 2021, May 24. Technology and Familial Relationships amid Covid-19. https://www.difi.org.qa/events/technology-and-familial-relationships-amid-covid-19/.

- Evans, M. D., J. Kelley, J. Sikora, and D. J. Treiman. 2010. “Family Scholarly Culture and Educational Success: Books and Schooling in 27 Nations.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 28 (2): 171–197.

- Faltisco, D. J. 1952. “A Study of the Intelligence, Achievement, Reading Habits, and Parental Occupations of Twenty Children in Orchard Park in Relation to the Home Library.” Doctoral diss., Canisius College.

- General Secretariat for Development Planning. 2008. Qatar National Vision 2030. https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/qnv1/Documents/QNV2030_English_v2.pdf.

- Greaney, V. 1986. “Parental Influences on Reading.” The Reading Teacher 39 (8): 813–818.

- Hannon, P. 1998. “How Can We Foster Children’s Early Literacy Development Through Parent Involvement.” In Children Achieving: Best Practices in Early Literacy, edited by S. Neuman, and K. Roskos, 121–143. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

- Hansen, H. S. 1969. “The Impact of the Home Literary Environment on Reading Attitude.” Elementary English 46 (1): 17–24.

- Ihmeideh, F. 2014. “The Effectiveness of a Training Program for Kindergarten Teachers to Help Families Promote Their Children Early Literacy Development and its Effect on Children Progress.” Jordanian Educational Journal 111 (28): 247–278.

- Ihmeideh, F., and F. Al-Maadadi. 2020. “The Effect of Family Literacy Programs on the Development of Children’s Early Literacy in Kindergarten Settings.” Children and Youth Services Review 118: 1–7.

- Khalifa, N. K. A. D. 2020. “Assessing the Impacts of Mega Sporting Events on Migrant Workers: A Case of the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar.” Journal of Philosophy, Culture and Religion 3 (1): 29–53.

- Le, T.-T.-H., T. Tran, T.-P.-T. Trinh, C.-T. Nguyen, T.-P.-T. Nguyen, T.-T. Vuong, T.-H. Vu, et al. 2019. “Reading Habits, Socioeconomic Conditions, Occupational Aspiration and Academic Achievement in Vietnamese Junior High School Students.” Sustainability 11 (18): 5113.

- Levine, L. 2002. Teachers’ Perceptions of Parental Involvement: How it Effects our Children’s Development in Literacy. Washington, DC: Educational Resources Information Center.

- McKool, S. S. 1998. “Factors that Influence the Decision to Read: An Investigation of Fifth Grade Students’ Out-of-School Reading Habits.” Doctoral Diss., The University of Texas at Austin.

- Morsy, W. 2016. The Reading Interests of EFL High School Students in Qatar. [Unpublished Manuscript]. College of Education, Qatar University.

- Nasser, R. 2013. “A Literacy Exercise: An Extracurricular Reading Program as an Intervention to Enrich Student Reading Habits in Qatar.” International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies 1 (1): 61–71.

- Nurdin, L., and A. F. Saufa. 2020. “Home Libraries and Their Roles in Social Changes among Rural Communities in Indonesia.” DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology 40: 6.

- Planning and Statistics Authority. 2021. Qatar Monthly Statistics of August 2021. Retrieved from https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/pages/default.aspx.

- Sikora, J., M. D. R. Evans, and J. Kelley. 2019. “Scholarly Culture: How Books in Adolescence Enhance Adult Literacy, Numeracy and Technology Skills in 31 Societies.” Social Science Research 77: 1–15.

- Timmons, K., and J. Pelletier. 2015. “Understanding the Importance of Parent Learning in a School-Based Family Literacy Programme.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 15 (4): 510–532.

- United Nations Development Programme, & Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Foundation. 2016. Arab Reading Index 2016. https://knowledge4all.com/admin/uploads/files/ARI2016/ARI2016En.pdf.

- Wollscheid, S. 2013. “Parents’ Cultural Resources, Gender and Young People's Reading Habits: Findings from a Secondary Analysis with Time-Survey Data in Two-Parent Families.” International Journal About Parents in Education 7 (1): 69–83.

- World Bank. 2021, September. Data Bank: Educational Attainment – Qatar. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.SEC.CUAT.UP.ZS?locations=QA.

- Zweiri, M., and F. Al Qawasmi. 2021. Contemporary Qatar: Examining State and Society. Singapore: Springer.

Appendix. Additional information on statistical analysis

Table A1. Chi-Squared association test between joining Qatar Reads and Gender.