ABSTRACT

The relevance of scientific research to local challenges and the need to produce actionable knowledge that benefits local development have not been evaluated. This study evaluates whether scientific research focused on the Amazonas region is framed within its five regional components of the Concerted Regional Development Plan (CRDP) to achieve sustainable development. In this study, 386 scientific articles published during 1960–2021 focusing on the Amazonas region were evaluated. Although Amazonas is the third poorest region in Peru, scientific production in this region has largely increased (CAGR2001-2021 = 16.4%). However, women and indigenous authors are underrepresented suggesting a unilateral knowledge transfer. The highest scientific contribution was reported for component 1 of the CRDP (58%), centering on topics about the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem services. Scientific research focusing on the Amazonas region fails to fully aboard the overall sustainable components of the CRDP. Social sciences are clearly understudied. It is the role of regional institutions (government, universities, industry, non-profit, etc.) to ensure the extension of research topics covering other dimensions of scientific knowledge and social needs. Conclusively, it is pending that local policymakers take into consideration emerging disciplines that can provide an updated perspective in developmental policies in the Amazonas region.

Introduction

Economic and social development of nations rely on their ability to transform scientific and technological knowledge into new products or processes (Mormina Citation2019). Scientific research provides important information on a range of areas and is expected to engage constructively with other actors in society to respond to humanitarian, societal, and global challenges, including the welfare of the community and equitable distribution of income (Smith and Todaro Citation2015; Bell and Willmott Citation2019; Nielsen Citation2021; Cicea et al. Citation2021). Scientific information is also valuable for policymaking and public policy decisions based on objective science (Haller and Gerrie Citation2007; Song Citation2008; More Citation2019). Furthermore, science is hailed as a significant basis for innovation (i.e. new technologies) that foster market success and prosperity and support global competition in a socially acceptable and sustainable way (Simon et al. Citation2019). However, the capacity to produce scientific and technological knowledge is highly variable globally (Mormina Citation2019).

According to citation impact and scientific quality indicators, scientific research worldwide is dominated by China, the United Kingdom, and the United States (Erfanmanesh, Tahira, and Abrizah Citation2017). In recent years, Israel, Singapore, and South Korea have considerably improved their research indicators due to the implementation of active research and development (R&D) policies that include sociocultural, geostrategic, and financial factors (Jiménez Citation2013; Baldeón Egas, Albuja Mariño, and Rivero Padrón Citation2019). R&D policies have generated well-trained academic personnel, improved quality of life standards, and increased gross domestic product (GDP) (Castelblanco Gómez and RobledoVelásquez Citation2014). The average national R&D expenditures of OECD countries during 2018 was 2.4% of the national budget (Nielsen Citation2021). In Latin America, scientific research is dominated by Chile, Brazil, and Mexico (Ocegueda et al. Citation2017; Forero et al. Citation2020), countries that reflect a direct relationship between the improvement of economic indicators and scientific production (Ynalvez and Shrum Citation2011).

Low and middle-income countries require (i) new ways of knowledge production and decision-making to build research capacity beyond individual training/skills building and, (ii) tools based on transdisciplinary, community-based, interactive, or participatory research approaches to involve actors outside of academia, that reflect real-world problems and create ownership of problems and solution options (Lang et al. Citation2012). Since development is a process of empowerment (Edwards Citation1989), these strategies will meet local needs and circumstances, and provide implementation of evidence-based policies (Schmalzbauer and Visbeck Citation2016; Salvia et al. Citation2019).

In Peru, although research is considered a key tool for the design of development strategies and policies, scientific production is at a concerning low (Huamaní and Mayta-Tristán Citation2010; Moquillaza Citation2019). However, compared to other countries worldwide (0.06% in 2012–0.1% in 2017) and to Latin America (1.25% in 2012–1.87% in 2017), gradual and consistent growth of scientific production has been observed in recent years (CONCYTEC Citation2019), mainly motivated by the increase in investment of GDP in R&D (0.108% in 2014–0.127% in 2018) (Limaymanta et al. Citation2020; World Bank Citation2021). Most of the scientific production belongs to the fields of medicine (40%), agricultural sciences (18%), and biological sciences (18%) (CONCYTEC Citation2019). These studies have been performed mainly in the Lima region (79.2%) (CONCYTEC Citation2019).

In northern Peru, the Amazonas region ranks 21st (out of 24) in the national ranking of scientific production (CONCYTEC Citation2019). Amazonas is a remote and unexplored region where the availability of historical records and biological information are poor, especially in rural areas and indigenous communities (Reátegui et al. Citation2018; Altea Citation2020; Mick et al. Citation2021). The pluricultural heritage of the Amazonas region is conducive to social research, while the ecological characteristics of the region involve vast biodiversity and natural resources for biological and environmental studies (Walentowski et al. Citation2018). Hence, the use of these resources under a technological and innovational scope, in addition to a critical mass of qualified researchers, policymakers, stakeholders, and of efficient government policies, might contribute to the development and welfare of the Amazonas region (CONCYTEC Citation2016a; Calderón-Vargas, Asmat-Campos, and Carretero-Gómez Citation2019).

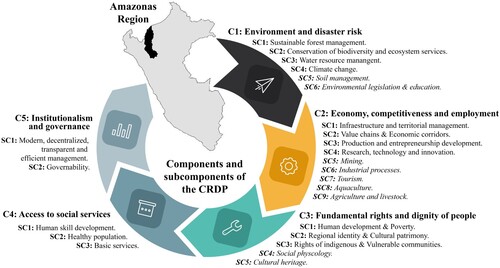

The concerted regional development plan (CRDP) is a management instrument of the Peruvian State for medium- and long-term strategic planning that guides comprehensive and sustainable development in the territory. This CRDP seeks coordination between urban and rural zones and promotes synergies with the private sector and civil society at the regional level (Anderson et al. Citation2018; CEPLAN Citation2021). The CRDP is developed with the participation and collaboration of the regional government (RG) and the National Center for Strategic Planning (CEPLAN) (CEPLAN Citation2021). The RG formulates and approves the CRDP with municipalities and civil society. To this end, the leadership of regional governors is important to meet the immediate needs of the population and to promote the development of the territories through strategic planning (Anderson et al. Citation2018). On the other side, CEPLAN advises State entities (including RG) in the formulation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and strategic development plans (Galloso and Ospino Citation2020). Accordingly, the CRDP from the Amazonas region during 2014–2021 framed the following five development components: (i) environment and disaster risk (C1); (ii) economy, competitiveness and employment (C2), (iii) fundamental rights and dignity of people (C3); (iv) access to services social (C4); and (v) institutionalism and governance (C5) (GOREA Citation2014; CEPLAN Citation2021).

Although Amazonas is the third poorest region in Peru, it has shown accelerated progress in scientific production (SUNEDU Citation2017) mainly due to the increase of funding in R&D areas by national agencies and the incorporation of specialized researchers (Moquillaza Citation2019). Nevertheless, the relevance of such research to local challenges and the need for such research to produce actionable knowledge that benefits local development have not been evaluated. Accordingly, the present study evaluates whether scientific research by academia focused on the Amazonas region (northern Peru) is framed within the five components of the CRDP to achieve sustainable development in Amazonas region. For such purposes, indexed articles in Web of Science, SCOPUS and SciELO focused on Amazonas region are analyzed to determine publication trends (by country, year, province, strategic objective, authorship gender, and scientific contribution networks) and contribution to the five regional strategic components of the CRDP in order to provide a more comprehensive view of the role of research in the pursuit of those components.

Material and methods

Articles indexed in SciELO, Scopus and Web of Science were analyzed for this study. These databases were selected as they support a broad array of scientific tasks across diverse knowledge domains and contain datasets for large-scale data-intensive studies (Li, Rollins, and Yan Citation2018). Although grey literature may record findings in niche or emerging research areas, it was not included as the study is focused on the scientific impact of academia is aimed. Therefore, only scholarly publications that passed through a formal and rigorous peer review process were selected. Articles from 1960 to 2021 involving different research areas and focusing on the Amazonas region were compiled according to Zhao, Li, and Li (Citation2005). Briefly, Boolean operators (‘AND’ & ‘OR’) and keywords referring to the provinces of the Amazonas region (‘Amazonas, Peru’, ‘Chachapoyas’, ‘Luya’; ‘Rodriguez de Mendoza’, ‘Utcubamba’, ‘Bagua’, ‘Bongara’, and ‘Condorcanqui’) were used. This time period (1960−2021) was chosen as it is contiguous with the first publication focusing on Amazonas. Besides the query terms, the data was limited to include research and review articles written in English, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish. It is worth mentioning that Amazonas region refers to one of the 24 second level administrative areas of Peru. During our search, the term ‘Amazonas region’ was discriminated from others such as ‘Amazon region’ or ‘Amazonia’ or ‘Alto Amazonas’ referring to either Amazon river Basin or the Brazilian state.

The database (Table S1, doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17161358.v2) grouped publications into the five regional components (C) and subcomponents (SC) of the CRDP () (GOREA Citation2014). To investigate in which component each article should be placed, we analyzed the words that are grammatically connected to each of the five regional components of the CRDP in the titles, abstract and key words of all the sampled articles. To this end, only terms that are directly relevant to the statements and overall vision of each component were analyzed (Klein and Manning Citation2003; Li, Rollins, and Yan Citation2018). Additionally, although this study focuses on the evaluation of research according to the current CRDP document, new subcomponents were added to include publications that are not included in this CRDP. Adding the new subcomponents avoids forcing the placement of the sampled articles in areas where they are not related.

Figure 1. Regional strategic components (C) and subcomponents (SC) of the CRDP of the Amazonas region. New subcomponents have been added in italics to group publications that were not included in the current CRDP.

Descriptive analyses of items associated with the five regional components of the CRDP (e.g. country, year, gender, ethnicity, province) were performed using tidyverse packages in R v4.1 software (Wickham Citation2017). Although the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) is an indicator commonly used to describe economic growth, the CAGR has also been reported to measure scientific growth (Hassan, Sarwar, and Muazzam Citation2015; Castillo and Powell Citation2019). The CAGR for the Amazonas region was calculated for periods of 20 years (1960–1980, 1981–2000, and 2001–2021) following the procedures of Castillo and Powell (Citation2019). Cross-tabulation matrices and histograms were performed to analyze the relationship between CRDP components and research production. Additionally, a heatmap combining the five regional components of the CRDP with their own subcomponents was constructed to visualize a number of scientific articles. The subcomponents with the highest scientific production were correlated with their own environmental and socioeconomic indicators to analyze the impact of research on these subcomponents (Tables S2–S3).

Network maps were constructed using the ‘full count’ method of VOSviewer v.1.6.17 software (Van Eck and Waltman Citation2010) to explore coauthorship (by countries, Peruvian regions, and institutions) and co-occurrence (words in article titles).

Results

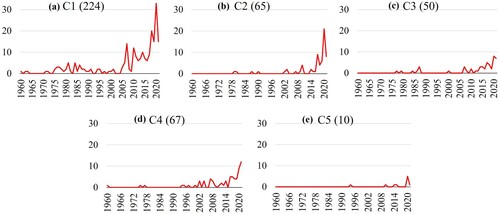

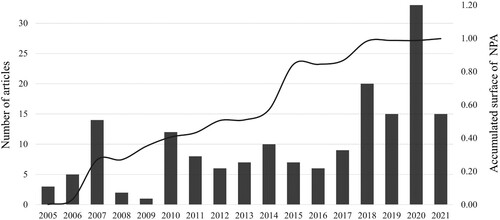

A total of 386 scientific articles focused on the Amazonas region were published from 1960 to 2021 in high-impact journals indexed in SciELO (75) and Scopus/Web of Science (311) (Figure S1). The lowest number of published articles was reported from 1960 to 2006 (ranged 0–6 publications). Conversely, there has been a considerable increase in scientific production in recent years (∼183 articles in the last four years) (), and these articles have been published mainly in international journals (77%). This result is consistent with the values of CAGRs for the periods 1960–1980, 1981–2000, and 2001–2021, which were 5.6%, 0.0% and 16.4%, respectively. Analyses of corresponding authors regarding gender indicated that scientific publications focused on the Amazonas region were dominated by male researchers (75%) (Figure S2). However, this trend is slowly reversing, as there has been a visible increase in women as corresponding authors in the last two years (). Unfortunately, there were no corresponding authors having an indigenous background, especially considering that indigenous communities Awajun, Wampi, and Quechua represent 16.5% of the population in Amazonas region (INEI Citation2020).

Figure 2. Temporal dynamics of publications from 1960 to 2021 within the Amazonas Region highlighting the gender of the corresponding author. Note the increase in scientific production during the last two decades [CAGR(1960-1980) = 5.6%, CAGR(1981-2000) = 0%, CAGR(2001-2021) = 16.4%].

![Figure 2. Temporal dynamics of publications from 1960 to 2021 within the Amazonas Region highlighting the gender of the corresponding author. Note the increase in scientific production during the last two decades [CAGR(1960-1980) = 5.6%, CAGR(1981-2000) = 0%, CAGR(2001-2021) = 16.4%].](/cms/asset/7b579cbe-edd9-407f-8fda-04081c8817cb/rdsr_a_2074492_f0002_oc.jpg)

Regarding the five regional components of the CRDP, the highest scientific contribution was reported for C1 (environment and disaster risk) (224 articles) ((a)). Additionally, significant contributions were reported for C2 (economy, competitiveness and employment) (65 articles), C3 (fundamental rights and dignity of people) (50 articles), and C4 (access to social services) (67 articles) ((b–d)). Conversely, the lowest contribution was recorded for C5 (institutionalism and governance) (10 articles) ((e)).

Figure 3. Temporal dynamics of publications from 1960 to 2021 within the Amazonas Region for each CRDP component. C1: Environment and disaster risk; C2: Economy, competitiveness and employment; C3: Fundamental rights and dignity of people; C4: Access to social services; and C5: Institutionalism and governance.

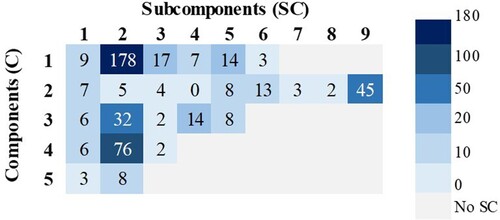

Nine additional subcomponents were added to the components of the CRDP to include some of the sampled articles. Two subcomponents were added to C1, five to C2 and two to C3. Heatmap analyses confronting the five regional components of the CRDP to its own subcomponents identified that the subcomponent biodiversity conservation (SC2) within C1 encompasses the highest number of scientific articles (178), whereas the subcomponent research, technology and innovation (SC4) within C2 did not record any articles ().

Figure 4. Heatmap contrasting scientific contributions by components (C1-C5) and subcomponents (SC = up to 9) of the CRDP within the Amazonas region.

To assess the impact of scientific findings on public policies in the Amazonas region, correlation analyses were performed among the number of published articles and each indicator contained in every component. The highest correlations found were those among the number of articles and four indicators (i.e. per capita family income, r = 0.791; accumulated surface of natural protected areas (NPA), r = 0.728; population affiliated with the Integral Health System, r = 0.699; flow of national and foreign tourists, r = 0.511) (Tables S2–S3). However, only the indicator ‘Accumulated surface of NPA’ (within SC2 and C1) was impacted and favored by the increase in publications focused on the conservation of biodiversity (). It is worth mentioning that although the other three indicators are correlated to the increase of publications, these are spurious correlations as they are associated but not causally related, due to the presence of a certain third factor (e.g. GDP).

Figure 5. Correlation of the indicator accumulated surface of NPA with the number of articles focused on conservation of biodiversity (SC2) in C1 of the CRDP.

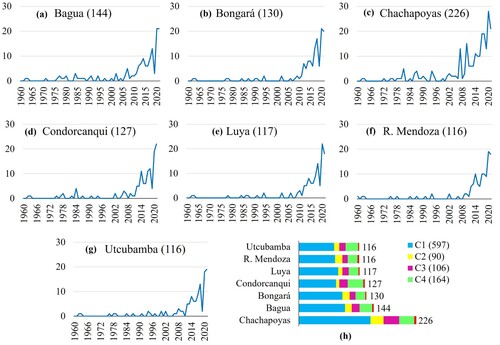

Regarding the studied provinces of the Amazonas region, the highest number of articles was focused on Chachapoyas (226 articles), whereas approximately half of the publications were focused on the remaining provinces (Bagua, 144; Bongará, 130; Condorcanqui, 127; Luya, 117; Rodríguez de Mendoza, 116; Utcubamba, 116) ((a–g)). Most of these articles encompassed research on components C1 and C4 of the CRDP ((h)).

Figure 6. Number of articles focused on the provinces of the Amazonas region from 1960 to 2021 (a-g) and proportion of articles according to each component of the CRDP (h).

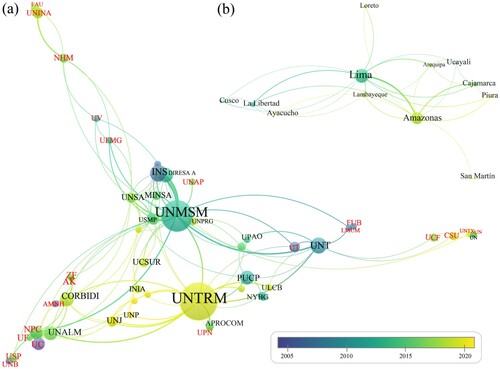

Over the last ∼60 years, 116 Peruvian institutions have performed research focusing on the Amazonas region ((a)). Of these, only two national universities Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodriguez de Mendoza, UNTRM and Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, UNMSM have contributed significantly, with 86 and 61 publications, respectively. The National Institute of Health (INS) and Universidad Nacional de Trujillo (UNT), with 17 and 11 publications, respectively, are other institutions with a significant scientific contribution. A temporal analysis showed that INS, UNT and UNMSM have been pioneers regarding scientific contribution, while UNTRM has produced a striking number of articles in recent years ((a)). Additionally, 222 foreign institutions have collaborated with Peruvian entities to perform research in the Amazonas region, such as the Neotropical Primate Conservation (10 articles), University of California (9), Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II (7), and University of Texas (6). In Peru, research institutions located in Lima and Amazonas have contributed significantly to the study of the Amazonas region ((b)), as they have produced 144 and 111 articles, respectively. Other regions neighboring Amazonas, such as La Libertad, Cajamarca and Lambayeque, made minor contributions by publishing 18, 13, and 10 articles, respectively.

Figure 7. Network map for (a) institutions having publications focused on the Amazonas region with at least three coauthored articles and (b) regions where institutions are located with at least two coauthored articles. Larger circles represent a larger number of publications, and nearby lines represent institutional collaborations.

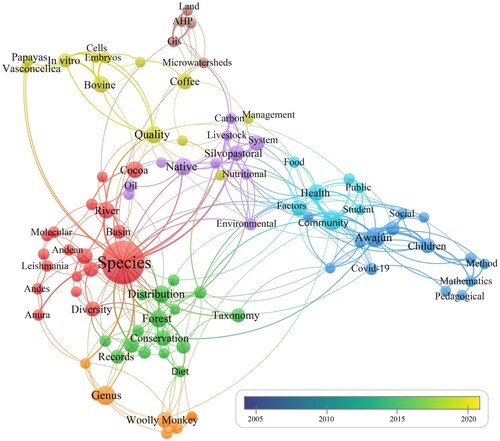

A total of 1286 words were identified in the titles, of which 148 appeared more than three times (). The words with the highest occurrence in publications belonging to component C1 were ‘species’ (65 articles), ‘genus’ (14), and ‘forest’ (10) (Figure 3S). Articles grouped in component C2 had the highest occurrences (five articles) for the words ‘bovine’, ‘native’, ‘cocoa’; ‘species’, ‘silvopastoral’, ‘invitro’, ‘coffee’, and ‘zinc’ (Figure 4S). In C3, ‘history’, ‘awajun’, ‘community’, and ‘archaeological’ occurred in six, five, four and three articles, respectively (Figure 5S). In C4, the keywords ‘community’ (9), ‘awajun’ (7), ‘health’ (7), ‘factors’ (6), ‘COVID-19’ (5), and ‘Leishmania’ (5) were the top-listed (Figure 6S), while in C5, the words ‘politics’, ‘management’, ‘children’, and ‘awajun’ occurred in two articles (Figure 7S).

Discussion

Scientific production has largely increased in the last 20 years in the Amazonas region (CAGR2001-2021 = 16.4%), especially in the last four years, where 183 articles have been published (). This publication rate is higher than the national average (11.2%) and that of other countries in the region, such as Ecuador (15.7%), Colombia (14.8%), Brazil (6.6%), Argentina (5.2%), and Mexico (4.6%), during the same period of time (Barreto, Rodríguez, and Chávez Citation2021).

Historically, UNMSM has been the institution with the largest scientific production in the Amazonas region; however, in the last 15 years, UNTRM (a national university located in Chachapoyas) has taken leadership in terms of scientific contribution (). This striking progress in the publication of scientific articles is a consequence of a major investment in GDP in R&D policies (Limaymanta et al. Citation2020), which is reflected mainly in (i) the increase of project funding and funders and (ii) the incorporation of specialized researchers (Moquillaza Citation2019). For instance, CONCYTEC (Peruvian National Council for Science, Technology and Technological Innovation), PNIA (National Agricultural Innovation Program), and FINCYT (Fund for Innovation, Science and Technology) granted a total of over 2 million USD for 10 projects to UNTRM in 2017 (UNTRM Citation2021a). Currently, this university is conducting 34 new projects from the above-mentioned sources (UNTRM Citation2021b). Additionally, the Law for the Promotion of the Development of Scientific Researchers promotes the work of highly specialized scientific researchers through the recognition of their professional careers and achievements. This policy also encourages the establishment of mechanisms to attract and retain national and foreign investigators (CONCYTEC Citation2019; Citation2021). These two mechanisms were allowed after SUNEDU (National Superintendence of Higher University Education) granted licensing to universities from the Amazonas region (SUNEDU Citation2017).

The large gender gaps regarding corresponding authorship (25% female researchers) have not been overcome in the high rate of publications in the Amazonas region. Currently, in Peru, only 31.9% of women enter in science-related careers, with sociocultural conflicts and stereotypes being the main factors limiting their participation (CONCYTEC Citation2016b). However, this scenario might change drastically as more female participation is encouraged in research projects by granting additional points for STEM proposals. Currently, one woman awarded a national science prize is currently conducting STEM research in the Amazonas region (CONCYTEC Citation2021). Additionally, this work reveleaed the absence of indigenous representation in research and encourages the incorporation of local actors outside of academia to create ownership in research agendas and break up the unilateral knowledge transfer.

This study indicates that a larger number of publications are related to the environment and disaster risk component (C1) of the CRDP, specifically associated with the subcomponent of biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services (SC2) ( and ). Additionally, ‘species’ was the main word for this component, with topics regarding organisms of economic and ecological importance. This scenario highlights the environmental and ecological value of the Amazonas region, which registers 11 out of 39 different ecosystems of the country (MINAM Citation2019; BCRP Citation2021) and includes 27 natural protected areas (SERNANP Citation2020). This region encompasses areas from low- and high-rainforests to highlands (Andes) and currently hosts abundant biodiversity (i.e. 36.6% mammals, 19.7% amphibians and reptiles, and 53.2% birds registered in Peru) (MINAM Citation2009), making it an attractive research hotspot (Jones and Solomon Citation2013; Cook, Edwards, and Lacey Citation2014; Boiral and Heras-Saizarbitoria Citation2015; Funk Citation2018).

Moreover, the recent increase in scientific production for the components regarding economy, employment, social services, population rights and cultural diversity (i.e. C2, C3, C4; ) reveals researchers’ commitment to understanding their impact on the development of the Amazonas region (Reátegui et al. Citation2018; Altea Citation2020; Mick et al. Citation2021). For instance, the main words for articles grouped in component C2 were ‘bovine’, ‘cocoa’, and ‘coffee’ corresponding to studies on biotechnology, zoometrics, silvopastoral systems, and agriculture (Cortez et al. Citation2017; Oliva et al. Citation2017; Pizarro et al. Citation2020). These publications are looking to maximize the growth of livestock and farming sectors in the region. ‘History’ was the main word in publication in component C3, with articles focusing on cultural richness (Leiva-González et al. Citation2019). This highlights the importance of the Chachapoyas and Awajun cultural heritage, ideas that are reinforced by the presence of over 900 tourist centers along the Amazonas region (MINCETUR Citation2017). In component 4, ‘community’, ‘awajun’, and ‘health’ were the main words based on issues regarding the formalization of rights, legal strategies in the defense of Amazonian territories, and the impact of COVID-19 on the economy and health of people from Amazonas (García, Veneros, and Tineo Citation2020; Aguilar León et al. Citation2021). On the other hand, the limited article contribution for the component of institutionalism and governance (C5) should empower researchers from the social and political science to embrace topics regarding public management, transparent administration, and efficient use of resources (GOREA Citation2014).

Despite the increase in scientific production in recent years in the Amazonas region, there is no strong linkage between the number of articles published and component indicators of the CRDP [i.e. per capita family income (2001−2017) (Liceras Citation2020), flow of domestic and foreign tourists (2010–2019) (Sánchez Citation2020), and the population affiliated with the Integral Health System (SIS) (Guerrero-Ojeda Citation2020)]. Only the indicator named accumulated area of NPA revealed a significant correlation (r = 0.728) with scientific production (). The increase in natural protected areas in recent years is a consequence of numerous articles aiming to propose the conservation of ecosystems (Scullion et al. Citation2021; Valqui et al. Citation2021), describe and report new and endemic taxa (Reátegui et al. Citation2018; Bustamante et al. Citation2019; Citation2021; Tineo et al. Citation2020), and monitor forests (Potapov et al. Citation2014; Anderson et al. Citation2018; Rojas-Briceno et al. Citation2019). These protection policies are looking to preserve the singular environment and biota from the Amazonas region.

Although the contribution of national institutions is higher than foreign institutions, these are focused mainly on publishing articles regarding topics of the C1 of the CRDP, specially on the conservation of biodiversity. The strategy of increasing the accumulated surface of NPA has positively impacted in the sustainable management of natural resources. since the Amazonas region comprised 28 protected areas covering 901,052.7 ha (∼21.4% of Amazonas region) by 2021 (SERNANP Citation2020). It is also noteworthy that 12 private conservation areas (out of 20) have been created in the last 10 years. This type of conservation strategy is promoting the involvement of organized local communities in resources management, the implementation of payments for environmental services, and sustainable and experiential tourism (Salvia et al. Citation2019). For instance, the creation of the Tilacancha Private Conservation Area (TPCA) in 2010 has secured the water source and supply to Chachapoyas, the capital city of Amazonas region through the protection of the watershed of Osmal and Cruzpata rivers (SERNANP Citation2020). TPCA also guarantees the conservation of grasslands, montane forests and biological diversity of the area. TPCA is managed by peasant communities namely San Isidro de Mayno and Levanto (SERNAMP Citation2020; Law RMA N° 118-2010-MINAM), representing a successful approach of social and environmental responsibility.

The spurious correlations of the other three indicators and the increase of publications confirm the presence of a third factor (Gea et al. Citation2013). Accordingly, the increase of publications causes the other three indicators when, in reality, both are caused by an additional factor. It is speculated that the increase of the Peruvian GDP per capita growth, that oscillated 2.2–8.3% annually in the last 10 years, has directly affected the per capita family income, flow of tourists and the population with the Integral Health System. It is established that GDP per capita rose faster than median household income and other indicators affecting them substantially (Nolan, Roser, and Thewissen Citation2016). Therefore, it is confirmed that increase in article publication is not responsible of the improvement in other indicators of the CRDP, except in the accumulated surface of NPA.

The almost double number of articles focused on Chachapoyas Province compared to the other provinces of the Amazonas region suggests that this city has strongly contributed to scientific production (). A city’s publishing efficiency is high if, for instance, the city is home to universities and research institutions and researchers affiliated with these institutions collaborate with researchers affiliated with cities of developed countries (György Citation2018). Accordingly, Chachapoyas is home to UNTRM, which is composed of 13 research institutions where ∼50 researchers are collaborating with researchers from the USA, South Korea, and Germany (CONCYTEC Citation2021). These collaborations focus mainly on biodiversity, biotechnology, genetics, and industrial technology. This finding suggest that Chachapoyas is further ahead in scientific development compared to the other provinces. This potentiality should be canalized to achieve the aims of the five components of the CRDP.

Although Amazonas is the third poorest region in Peru, it has shown accelerated progress in scientific production as a consequence of the establishment and licensing of two national universities (UNTRM, UNIFSLB) (SUNEDU Citation2017; Citation2018). This has greatly improved the quality of education (i.e. higher rates of access to education at university, reduction in illiteracy rate; INEI Citation2020) and has generated knowledge for maximizing economic activities such as productive chains of cocoa, coffee, rice, and the tourism and bovine sector (DIRCETUR Citation2010; GOREA Citation2014; MINCETUR Citation2017). However, the continuous increase in scientific production requires policies with financial programs that ensure the sustainability of research projects over time (García, Veneros, and Tineo Citation2020). Additionally, increasing funding, recognition of researchers (especially women and natives), and empowerment of vigilant institutions (e.g. CONCYTEC, SUNEDU) have shown to be key factors for scientific development, which might impact quality of life standards and regional indicators. Moreover, scientific research should be promoted in collaborative networks among universities, research centers, and the private sector with a holistic and multidisciplinary vision to reduce the current separation of sociocultural, geostrategic, and financial factors (Boiral and Heras-Saizarbitoria Citation2015; Salvia et al. Citation2019; Millones-Gómez et al. Citation2021).

Academia tends to focus on generating scientific knowledge highlighting scientist’s technical competences (through training and collaboration) without including transdisciplinary research that facilitate the identification of societally relevant problems, mutual learning processes from different disciplines, and transferable solution-oriented knowledge (Lang et al. Citation2012). Accordingly, scientific research performed by academia focusing on Amazonas region is failing to fully aboard the overall sustainable components of the CRDP. Social sciences are clearly understudied (e.g. rights of indigenous & vulnerable communities; basic services; modern, decentralized, transparent and efficient management), while research focused on innovation and technology has no published articles. However, this last finding can be underestimated due to innovation and technology is an emerging discipline in Amazonas region where researchers prioritize patents over the publication of scholarly articles.

The prevalence of research focused mainly on natural science (C1) reflects how Amazonas region is perceived by national and international scientists, as an unexplored area with a large biodiversity potential that is awaiting the discovery of natural resources. It is the role of regional institutions (government, universities, industry, non-profit, etc.) to ensure the extension of the research topics that cover other dimensions of scientific knowledge and social needs. Additionally, national and regional governments are missing the investments to develop and sustain the socioeconomic and political structures that facilitate knowledge creation (Mormina Citation2019) reducing unequal opportunities for research between scientific and social actors (Parker and Kingori Citation2016). Thereby, it is important that local policymakers take into consideration emerging disciplines (i.e. new sub-components of this study such as soil management, social psychology, industrial legislation, environmental legislation) that can provide an updated perspective in developmental policies in the Amazonas region.

RDSR_2074492_Supplementarymaterial

Download Zip (7.3 MB)Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to Stefhany Valdeiglesias Ichillumpa and Ananco Ahuananchi Oswaldo for their translations to Quechua and Awajun languages, respectively. Additionally, authors would like to thank Elizabeth Gill from University of New Hampshire for language editing/polishing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguilar León, P., K. Moreno Huaccha, J. D. Carpio Venegas, and F. Solano Zapata. 2021. “Impact of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) on Public Health, Environment and Economy: Analysis and Evidence from Peru.” In Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreaks, Environment and Human Behaviour, edited by R. Akhtar, 405–422. Cham: Springer.

- Altea, L. 2020. “Perceptions of Climate Change and its Impacts: A Comparison Between Farmers and Institutions in the Amazonas Region of Peru.” Climate and Development 12 (2): 134–146.

- Anderson, C. M., G. P. Asner, W. Llactayo, and E. F. Lambin. 2018. “Overlapping Land Allocations Reduce Deforestation in Peru.” Land Use Policy 79: 174–178.

- Baldeón Egas, P. F., P. A. Albuja Mariño, and Y. Rivero Padrón. 2019. “Las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación en la gestión estratégica universitaria: experiencias en la Universidad Tecnológica Israel.” Conrado 15 (68): 83–88.

- Barreto, I. B., H. P. E. Rodríguez, and W. O. Chávez. 2021. “Context of Scientific Publications in Regionally Indexed Journals Versus Global Publications.” Revista Digital de Biblioteconomia e Ciencia Da Informacao 19: e021009.

- BCRP (Banco Central de Reserva del Perú). 2021. Caracterización del Departamento de Amazonas. Obtenido de: https://www.bcrp.gob.pe.

- Bell, E., and H. Willmott. 2019. “Ethics, Politics and Embodied Imagination in Crafting Scientific Knowledge.” Human Relations 73: 1–22.

- Boiral, O., and I. Heras-Saizarbitoria. 2015. “Managing Biodiversity Through Stakeholder Involvement: Why, Who, and for What Initiatives?” Journal of Business Ethics 140 (3): 403–421.

- Bustamante, D. E., M. S. Calderon, S. Leiva, J. E. Mendoza, M. Arce, and M. Oliva. 2021. “Three New Species of Trichoderma in the Harzianum and Longibrachiatum Lineages from Peruvian Cacao Crop Soils Based on an Integrative Approach.” Mycologia 113: 1–17.

- Bustamante, D. E., M. Oliva, S. Leiva, J. E. Mendoza, L. Bobadilla, G. Angulo, and M. S. Calderon. 2019. “Phylogeny and Species Delimitations in the Entomopathogenic Genus Beauveria (Hypocreales, Ascomycota), Including the Description of B. peruviensis sp. nov.” MycoKeys 58: 47–68.

- Calderón-Vargas, F., D. Asmat-Campos, and A. Carretero-Gómez. 2019. “Sustainable Tourism and Renewable Energy: Binomial for Local Development in Cocachimba, Amazonas, Peru.” Sustainability 11 (18): 4891.

- Castelblanco Gómez, J., and J. RobledoVelásquez. 2014. “Relación entre el PIB y algunos indicadores de Ciencia y Tecnología: Colombia vs. Corea del Sur.” Escenarios: Empresa y Territorio 3: 3.

- Castillo, J. A., and M. A. Powell. 2019. “Análisis de la producción científica del Ecuador e impacto de la colaboración internacional en el periodo 2006–2015.” Revista Española de Documentación Científica 42 (1): 225.

- CEPLAN. 2021. “Guía para el Plan de Desarrollo Regional Concertado CRDP”. CEPLAN: Lima, Perú.

- Cicea, C., L. Tsoulfidis, C. Marinescu, C. S. Popa, and C. F. Albu. 2021. “Applying Text Mining Technique on Innovation-Development Relationship: A Joint Research Agenda.” Economic Computation and Economic Cybernetics Studies Research 55: 5–21.

- CONCYTEC. 2016a. Crear para Crecer, Política Nacional para el Desarrollo de la Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Tecnológica. Lima: Consejo Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación. 5–27.

- CONCYTEC. 2016b. I. Censo Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo a Centros de Investigación 2016. Lima: Consejo Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación. 5–27.

- CONCYTEC. 2019. Principales indicadores bibliométricos de la actividad científica peruana 2012-2017. CONCYTEC: Lima, Perú. ISBN: 978-9972-50-192-0.

- CONCYTEC. 2021. Investigadores en el Registro Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología y de Innovación Tecnológica. Consejo Nacional de Ciencias, Tecnología e Innovación Tecnológica. https://ctivitae.concytec.gob.pe/renacyt-ui/#/registro/investigadores.

- Cook, J., S. Edwards, and E. A. Lacey. 2014. “Natural History Collections as Emerging Resources for Innovative Education.” BioScience 64: 725–234.

- Cortez, J. V., N. Murga, G. Segura, L. Rodríguez, H. Vásquez, and J. Maicelo. 2017. “Capacidad de Dos Líneas Celulares para la Producción de Embriones Clonados mediante Transferencia Nuclear de Células Somáticas.” Revista de Investigaciones Veterinarias del Perú 28 (4): 928–938.

- DIRCETUR (Dirección Regional de Comercio Exterior y Turismo). 2010. Amazonas Guía Turística, 1–130. Lima: Dircetur press.

- Edwards, M. 1989. “The Irrelevance of Development Studies.” Third World Quarterly 11 (1): 116–135.

- Erfanmanesh, M., M. Tahira, and A. Abrizah. 2017. “The Publication Success of 102 Nations in Scopus and the Performance of Their Scopus-Indexed Journals.” Publishing Research Quarterly 33 (4): 421–432.

- Forero, D. A., M. L. Trujillo, Y. González-Giraldo, and G. E. Barreto. 2020. “Scientific Productivity in Neurosciences in Latin America: A Scientometrics Perspective.” International Journal of Neuroscience 130 (4): 398–406.

- Funk, V. 2018. “Collections-based Science in the 21st Century.” Journal of Systematics and Evolution 56: 175–193.

- Galloso, P. E. M., and E. J. J. Ospino. 2020. “Desarticulación del planeamiento estratégico y la programación presupuestaria y su efecto en la gestión del CEPLAN.” Pensamiento Crítico 25 (2): 69–106.

- García, L., J. Veneros, and D. Tineo. 2020. “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV-2): A National Public Health Emergency and its Impact on Food Security in Peru.” Scientia Agropecuaria 11 (2): 241–245.

- Gea, M. M., C. Batanero, G. R. Cañadas, and P. Arteaga. 2013. “La estimación de la correlación: variables de tarea y sesgos de razonamiento.” In Educación Estadística en América Latina: Tendencias y Perspectivas, edited by A. Salcedo, 361–384. Programa de Cooperación Interfacultades. Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela.

- GOREA (Gobierno Regional de Amazonas). 2014. Plan de Desarrollo Regional Concertado Actualizado: Amazonas al 2021. Obtenido de: https://www.gob.pe/regionamazonas.

- Guerrero-Ojeda, G. A. 2020. “Gasto de bolsillo en salud y riesgo de pobreza en hogares peruanos: Perú 2017.” Salud & Vida Sipanense 7 (2): 27–40.

- György, C. 2018. “Factors Influencing Cities Publishing Efficiency.” Journal of Data and Information Science 3: 43–80.

- Haller, S. F., and J. Gerrie. 2007. “The Role of Science in Public Policy: Higher Reason, or Reason for Hire?” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 20: 139–165.

- Hassan, S. U., R. Sarwar, and A. Muazzam. 2015. “Tapping Into Intra- and International Collaborations of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation States Across Science and Technology Disciplines.” Science and Public Policy 43 (5): 690–701.

- Huamaní, C., and P. Mayta-Tristán. 2010. “Producción científica peruana en medicina y redes de colaboración, análisis del Science Citation Index 2000-2009.” Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública 27 (3): 315–325.

- INEI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática). 2020. Indicadores de Educación por Departamento, 2009-2019. https://ctivitae.concytec.gob.pe/renacyt-ui/#/registro/investigadores.

- Jiménez, R. 2013. “Comparación de políticas de desarrollo: Irlanda, Corea del Sur, Finlandia y Costa Rica.” Revista Rupturas 3 (1): 112–138.

- Jones, M. J., and J. F. Solomon. 2013. “Problematising Accounting for Biodiversity.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 26 (5): 668–687.

- Klein, D., and C. D. Manning. 2003. Accurate unlexicalized parsing. In Proceedings of the 41st annual meeting on association for computational linguistics-volume 1 (pp. 423–430). Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Lang, D. J., A. Wiek, M. Bergmann, M. Stauffacher, P. Martens, P. Moll, M. Swilling, and C. J. Thomas. 2012. “Transdisciplinary Research in Sustainability Science: Practice, Principles, and Challenges.” Sustainability Science 7: 25–43.

- Leiva-González, S., E. F. Rodríguez-Rodríguez, L. E. Pollack-Vel, J. Briceño-Rosario, J. Jiménez-Saldaña, G. Gayoso-Bazán, and J. Rascón-Barrios. 2019. “Diversidad natural y cultural del Complejo Arqueológico Kuélap (provincia Luya, región Amazonas): la fortaleza de los hombres de las nubes.” Arnaldoa 26 (3): 883–930.

- Li, K., J. Rollins, and E. Yan. 2018. “Web of Science use in Published Research and Review Papers 1997–2017: A Selective, Dynamic, Cross-Domain, Content-Based Analysis.” Scientometrics 115: 1–20.

- Liceras, A. N. 2020. “Desigualdad y hambre en el Perú: 2001-2017.” Investigaciones Sociales 22 (42): 287–301.

- Limaymanta, C. H., H. Zulueta-Rafael, C. Restrepo-Arango, and P. Álvarez-Muñoz. 2020. “Análisis bibliométrico y cienciométrico de la producción científica de Perú y Ecuador desde Web of Science (2009-2018).” Información, cultura y sociedad 43: 31–52.

- Mick, C., M. E. Fernández, C. Alvarado-Chuqui, C. A. Amasifuen-Guerra, M. Kleiche-Dray, A. P. López-Minchán, and J. O. Silva-López. 2021. “Regional Development in Amazonas, Peru: Science-Society Interactions for Sustainability.” The Anthropocene Review 8 (1): 3–20.

- Millones-Gómez, P. A., J. S. Yangali-Vicente, C. M. Arispe-Alburqueque, O. Rivera-Lozada, K. M. Calla-Vásquez, R. D. Calla-Poma, and C. A. Minchón-Medina. 2021. “Research Policies and Scientific Production: A Study of 94 Peruvian Universities.” PloS one 16 (5): e0252410.

- MINAM (Ministerio del Ambiente). 2009. Indicadores Ambientales Amazonas. Available from http://localhost:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/240.

- MINAM (Ministerio del Ambiente). 2019. Mapa Nacional de Ecosistemas del Perú - Memoria Descriptiva. Available from https://geoservidor.minam.gob.pe/informacion-institucional/publicaciones/.

- MINCETUR (Ministerio de Comercio Exterior y Turismo). 2017. Reporte Regional de Comercio Amazonas. Available from https://www.mincetur.gob.pe.

- Moquillaza, A. V. H. 2019. “Producción científica asociada al gasto e inversión en investigación en universidades peruanas.” Anales de la Facultad de Medicina 80 (1): 56–59.

- More, S. J. 2019. “Perspectives from the Science-Policy Interface in Animal Health and Welfare.” Frontiers in Veterinary Science 6: 382.

- Mormina, M. 2019. “Science, Technology and Innovation as Social Goods for Development: Rethinking Research Capacity Building from Sen’s Capabilities Approach.” Science and Engineering Ethics 25: 671–692.

- Nielsen, K. H. 2021. “Book Review of Science and Public Policy.” Metascience 30: 79–81.

- Nolan, B., M. Roser, and S. Thewissen. 2016. “GDP per Capita Versus Median Household Income: What Gives Rise to Divergence Over Time?” Social Macroeconomics 5: SMWP2016.

- Ocegueda, J., M. Miramontes, P. Moctezuma, and A. Mungaray. 2017. “Análisis comparado de la cobertura de la educación superior en Corea del Sur y Chile: una reflexión para México.” Perfiles Educativos 39 (155): 141–159.

- Oliva, M., L. Culqui-Mirano, S. Leiva, R. Collazos, R. Salas, H. V. Vásquez, and J. L. Maicelo-Quintana. 2017. “Reserva de carbono en un sistema silvopastoril compuesto de Pinus patula y herbáceas nativas.” Scientia Agropecuaria 8 (2): 149–157.

- Parker, M., and P. Kingori. 2016. “Good and Bad Research Collaborations: Researchers’ Views on Science and Ethics in Global Health Research.” PLoS ONE 11 (10): e0163579.

- Pizarro, D., H. Vásquez, W. Bernal, E. Fuentes, J. Alegre, M. S. Castillo, and C. Gómez. 2020. “Assessment of Silvopasture Systems in the Northern Peruvian Amazon.” Agroforestry Systems 94 (1): 173–183.

- Potapov, P. V., J. Dempewolf, Y. Talero, M. C. Hansen, S. V. Stehman, C. Vargas, and B. R. Zutta. 2014. “National Satellite-Based Humid Tropical Forest Change Assessment in Peru in Support of REDD+ Implementation.” Environmental Research Letters 9 (12): 124012.

- Reátegui, R. C., L. Pawera, P. P. V. Panduro, and Z. Polesny. 2018. “Beetles, Ants, Wasps, or Flies? An Ethnobiological Study of Edible Insects among the Awajún Amerindians in Amazonas, Peru.” Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 14 (1): 1–11.

- Rojas-Briceno, N. B., E. Barboza-Castillo, J. L. Maicelo-Quintana, S. M. Oliva-Cruz, and R. Salas-López. 2019. “Deforestación en la Amazonía peruana: índices de cambios de cobertura y uso del suelo basado en SIG.” Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 81: 2538a.

- Salvia, A. L., W. L. Filho, L. L. Brandli, and J. S. Griebeler. 2019. “Assessing Research Trends Related to Sustainable Development Goals: Local and Global Issues.” Journal of Cleaner Production 208: 841e849.

- Sánchez, M. M. 2020. “Inestabilidad, violencia y turismo en Perú: una aproximación desde el papel del Estado.” Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política, Humanidades y Relaciones Internacionales 22 (43): 367–392.

- Schmalzbauer, B., and M. Visbeck. 2016. “The Contribution of Science in Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals.” German Committee Future Earth, Stuttgart/ Kiel. http://futureearth.org/sites/default/files/2016_report_contribution_science_sdgs.pdf. (Accessed 23 March 2022).

- Scullion, J. J., J. Fahrenholz, V. Huaytalla, E. M. Rengifo, and E. Lang. 2021. “Mammal Conservation in Amazonia’s Protected Areas: A Case Study of Peru’s Ichigkat Muja-Cordillera del Cóndor National Park.” Global Ecology and Conservation 26: e01451.

- SERNANP (Servicio Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas por el Estado). 2020. Sistema de Áreas Naturales Protegidas del Perú: Áreas Naturales Protegidas de administración nacional con categoría definitiva. Available from https://old.sernanp.gob.pe/sernanp/contenido.jsp?ID = 119.

- Simon, D., S. Kuhlmann, J. Stamm, and W. Canzleret. 2019. Handbook on Science and Public Policy, 1–584. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Smith, S. C., and M. Todaro. 2015. Economic Development. Pearson: George Washington University.

- Song, J. 2008. “Awakening: Evolution of China’s Science and Technology Policies.” Technology in Society 30 (3–4): 235–241.

- SUNEDU (Superintendencia Nacional de Educación Superior Universitaria). 2017. Resolución del Consejo Directivo N° 033-2017-SUNEDU/CD: Otorga la Licencia Institucional a la Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas, para ofrecer el servicio educativo superior universitario.

- SUNEDU (Superintendencia Nacional de Educación Superior Universitaria). 2018. Resolución del Consejo Directivo N° 095-2018-SUNEDU/CD.: Otorgan la Licencia Institucional a la Universidad Nacional Intercultural Fabiola Salazar Leguía de Bagua, para ofrecer el servicio educativo superior universitario.

- Tineo, D., D. E. Bustamante, M. S. Calderon, J. E. Mendoza, E. Huaman, and M. Oliva. 2020. “An Integrative Approach Reveals Five New Species of Highland Papayas (Caricaceae, Vasconcellea) from Northern Peru.” Plos One 15 (12): e0242469.

- UNTRM. 2021a. Proyectos de Investigación financiados con fondos externos - UNTRM. Available from https://www.untrm.edu.pe/es/proyectos-financiados-con-fondos-externos.html.

- UNTRM. 2021b. Más de 9 millones de soles en proyectos de investigación, ciencia y tecnología para la UNTRM. Available from https://www.untrm.edu.pe/es/noticias/647-mas-de-8-millones-de-soles-en-financiamiento-de-proyectos.html.

- Valqui, B. K. G., A. García-Bravo, E. E. A. Salazar, I. A. M. Castillo, C. T. Guzmán, and S. M. O. Cruz. 2021. “Endemism of Woody Flora and Tetrapod Fauna, and Conservation Status of the Inter-Andean Seasonally Dry Tropical Forest of the Marañón Valley.” Global Ecology and Conservation 28: e01639.

- Van Eck, N. J., and L. Waltman. 2010. “Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping.” Scientometrics 84 (2): 523–538.

- Walentowski, H., S. Heinrichs, S. Hohnwald, A. Wiegand, H. Heinen, M. Thren, and S. Zerbe. 2018. “Vegetation Succession on Degraded Sites in the Pomacochas Basin (Amazonas, N Peru)—Ecological Options for Forest Restoration.” Sustainability 10 (3): 609.

- Wickham, H. 2017. Tidyverse: Easily Install and Load the ‘Tidyverse’. Available from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dplyr/index.html.

- World Bank. 2021. Gasto en investigación y desarrollo (% del PIB). Available from https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicador/GB.XPD.RSDV.GD.ZS?end=2017&most_recent_year_desc=true&start=1996&type=shaded&view=map.

- Ynalvez, M. A., and W. M. Shrum. 2011. “Professional Networks, Scientific Collaboration, and Publication Productivity in Resource-Constrained Research Institutions in a Developing Country.” Research Policy 40 (2): 204–216.

- Zhao, S., Z. Li, and W. Li. 2005. “A Modified Method of Ecological Footprint Calculation and its Application.” Ecological Modelling 185: 65–75.