?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Although scholarly attention towards inclusive economic development is emergent, its concept and evaluation remain ambiguous since few attempts have been made to elaborate on its definitions and goals. In this study, we conceptualize and define inclusive economic development, propose a productivity perspective for evaluating it, and construct an inclusive total factor productivity index based on data envelopment analysis. According to the estimation results, we report and map the major findings of our index. The results demonstrate that although inclusive economic development is progressing globally, significant regional disparities persist.

1. Introduction

Inclusive development has drawn substantial scholarly attention from many academic disciplines due to emergent appeals for inclusiveness in the global society. Although rapid economic growth in the last few decades has significantly reduced the number of underprivileged countries, it has intensified inequality due to the limitations of the prevailing classical development paradigm. Considering economic growth as the prerequisite for achieving social inclusiveness, the classical development paradigm generally equates development to GDP growth or GDP per capita (Kuznets Citation1984; Rubin and Segal Citation2015; Woo Citation2011; Risso, Punzo, and Sánchez Carrera Citation2013). However, although economic growth is an essential and indispensable dimension of development, its dominance in understanding state and governance models is incapable of providing sufficient guidance for building flourishing and equal societies (Gupta and Pouw Citation2017). It excludes unpaid and informal activities critical for development processes, focuses exclusively on ex-post redistribution instead of active ex-ante participation and planning in resolving inequality issues, and relies on the neo-liberalistic and capitalistic framework that encourages market competition and minimizes the role of the state. These viewpoints are economically favorable but ecologically and socially destructive (Brand, Boos, and Brad Citation2017; Cabeza-García, Del Brio, and Oscanoa-Victorio Citation2019). Critiques from different perspectives have ignited a new conceptualization that emphasizes social inclusiveness by replacing the focus of development from GDP with alternative aspects, such as human wellbeing, life quality, and empowerment of marginalized people.

The concepts of inclusive growth and economic growth have been well studied and documented in the literature, as they are widely considered in policy formulation in major international institutions participating in global development, including the United Nations, the World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank. It is common for scholars to regard inclusive economic growth as interchangeable with inclusive growth and to thus equalize these two concepts. This welfare approach to development recognizes economic growth as the pathway toward job creation, which can improve the living conditions of marginalized people. It focuses on the economic performance of an economy based on the belief that uneven income distribution is the main cause of inequality. Critics of this approach emerge because this dedicated concentration ignores other dimensions of inequality, such as gender, politics, and education (Brand, Boos, and Brad Citation2017; Koralagama, Gupta, and Pouw Citation2017). Increases in income per capita or rationalization of income distribution may not be sufficient to benefit citizens and reduce inequality. For instance, education inequalities may not change, or may even be intensified as the economy grows. Thus, inclusiveness should not be confined to the narrow concept of growth, but instead should go beyond income concerns to embrace other dimensions of wellbeing (Mamat et al. Citation2016).

Embracing these opinions, the recent literature focuses more on inclusive development, emphasizing the social, political, and ecological dimensions of inclusive development by expanding the scope of development and inclusiveness (Gupta, Pouw, and Ros-Tonen Citation2015; Pouw and Gupta Citation2017). This transition aims to ensure development benefits the well-being of citizens and to acknowledge the interdependency between development initiatives and environmental sustainability (Gupta, Pouw, and Ros-Tonen Citation2015). This argument was further expanded by Johnstone (Citation2022) by accessing inclusiveness from universal-plural perspectives and social-relational perspectives, which enable the concrete identification of both the aims and intended outcomes of inclusive development initiatives.

However, although significant advances have been made in developing multidimensional measures of inclusive development, they still provide little guidance to academia or governments for achieving inclusive development due to inconsistency in methodologies and limitations in data availability (Gupta, Pouw, and Ros-Tonen Citation2015). This dilemma is caused by two problems: First, inclusive development entails development and inclusiveness, but both are broad concepts that lack conceptual scholarship. The concept of development is all-inclusive, encompassing governance, social, environmental, economic, political, educational, and other related aspects. Such a comprehensiveness of scope generates significant difficulties when evaluating inclusive development (Rauniyar and Kanbur Citation2010). Meanwhile, although many attempts have been made to define inclusiveness, they still lack rigor or criticality since inclusiveness is a politically acceptable concept that can be applied to almost any program or initiative (Johnstone Citation2022; Clifford Simplican Citation2019). Lack of specificity makes the use of these two concepts discursive and adds considerable difficulties in evaluating inclusive development. Second, there is no agreed and common definition of inclusive development, and its conceptualization is open to interpretation and debate. Indices constructed based on different theoretical frameworks and methodologies cannot be compared, nor do they provide consistent results for reference. For appraisal systems using weighting methods with pre-defined weights, evaluation bias due to subjectivity in formulating methodologies can also be problematic (Ran et al. Citation2021).

In this study, we proposed the concept of inclusive economic development as a sub-concept of inclusive development to address the abovementioned problems. Limiting the scope of development while retaining the comprehensive idea of multifaceted social inclusiveness allows for concrete conceptualization, explicit evaluation methodology and processes, and intuitive policy implications, while does not diminish the importance of the collective wellbeing and long-term sustainability embodied in inclusive development. It can thus better guide policy and practice to promote inclusive development by precisely identifying the status quo of inclusive development. Based on our comparative analysis of the existing literature concerning theoretical frameworks of inclusive development, we conceptualized inclusive economic development and propose the definition of ‘the capacity to advance economic growth, developed with the contribution of all citizens, without excluding any important group of society’. Furthermore, using data envelopment analysis, a nonparametric method for assessing the performance of decision-making units, we constructed the inclusive total factor productivity (iTFP) indices and evaluated the progress of inclusive development on a national scale.

Methodologically, the iTFP is an ideal proxy for inclusive economic development. As an interregionally and intertemporally comparable measure of inclusive economic development, this unified index enables further empirical research such as identifying regional-specific, nation-specific, or global prerequisites, determinants, and outcomes of inclusive economic development. It can also be extended to other evaluation scenarios by altering the variables or evaluation scale. Our results demonstrate that although inclusive economic development has progressed globally, significant regional disparities persist. The decrease in iTFP indices in Africa, Central Asia, and Eastern Asia calls for more robust measures to promote social inclusion in these regions during economic development.

This study contributes to the literature in the following ways. Conceptually, this study formally defines inclusive economic development by comparatively discussing and synthesizing existing viewpoints. The proposed definition may support further scholarship on the relevant topics. Methodologically, based on the definition, this study develops the iTFP as a pragmatic measurement of inclusive economic development with the DEA method. The indices can be applied in future quantitative or empirical explorations. Empirically, this study also provides a panoramic view of the status quo of global inclusive economic development, evidencing the importance of further endeavors for promoting social inclusiveness in economic development processes.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the existing literature related to inclusive economic development and the main theories of inclusive development to conceptualize inclusive economic development; Section 3 develops the model for measuring iTFP and presents the data used in the evaluation; Section 4 reports the results and major findings from our index covering the 2000–2019 period, and compares our results with other measures of inclusive development and inclusive economic development; Section 5 concludes the paper and describes possible applications of the indices.

2. Literature review and theoretical analysis

2.1. Conceptualizing inclusive economic development

The concept of inclusive economic development emerges from inclusive economic growth, which has been studied in a variety of works. For instance, Klasen (Citation2010) highlighted two distinctive characteristics of inclusive growth: expressly non-discriminatory and expressly disadvantage-reducing economic growth. Anand et al. (Citation2013) suggested that inclusive growth refers to both the pace and distribution of economic growth, and that inclusiveness is the precondition for economic growth to be sustainable and effective in reducing poverty. Fourie (Citation2014) proposed that inclusive growth is economic growth that incorporates equity and the wellbeing of all sections of the population, with poverty being considered either in absolute terms or relative terms. Barua and Sawhney (Citation2015) regarded inclusive economic growth as inducing economic growth while reducing regional income inequality, proposing that if the share of income of each region is equal to the share of its population, there will be no inequality across regions and, thus, economic growth would be inclusive among regions within a country. Ngepah (Citation2017) suggested that inclusive economic growth entails more active participation of marginalized people during the processes of wealth creation, instead of passive participation in the traditional concept of pro-poor growth. Cabeza-García, Del Brio, and Oscanoa-Victorio (Citation2018) proposed that inclusive economic growth indicates that the effort to advance a country's growth and development should be made with the contribution of all citizens. Meanwhile, some studies consider the status quo, determinants, and impacts of inclusive growth with different samples or methodologies. But these attempts are generally based on relatively vague concepts (Wang and Wang Citation2020).

These definitions of inclusive economic growth, although with minor differences, share two common features that have been criticized in the recent literature. First, for either inclusive growth or inclusive economic growth, the focus is on the outcome of economic growth, such as increases in GDP or GNI. As noted by Gupta, Pouw, and Ros-Tonen (Citation2015), this perspective exclusively focuses on economic performance indicators, so it fails to capture the multiple dimensions of poverty adequately. It is also more concerned with absolute poverty than relative poverty and thus cannot be used to analyse the local and global drivers of inequality. Second, in terms of social inclusiveness, most of the abovementioned concepts lack consistency in explaining the components of social inclusiveness, and approaches to measuring the degree of inclusiveness vary depending on the criteria for measurement (Prada and Sánchez-Fernández Citation2019).

For the first criticism, a solution is to broaden the scope of inclusive growth to encompass the inputs and processes of growth (de Haan Citation2015). In the context of economic development, this means transforming the focus from economic growth to growth capacity. For the second criticism, the conceptual framework of inclusion developed by Johnstone (Citation2022) is able to explain how the concept of inclusiveness can be used to pursue desirable outcomes in inclusive development. Compared to the idea of inclusive economic growth, inclusive economic development focuses on the capacity, rather than outcomes, of economic growth. Meanwhile, it considers social inclusiveness from universal, plural, social, and relational inclusion. Given that this concept is more concrete and better reflects the importance of long-term sustainability and collective wellbeing, a conceptual transition from inclusive economic growth to inclusive economic development is suggested.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to conceptualize inclusive economic development formally. Although this term has been mentioned in some previous studies in the literature, no exact definition of it has been provided, nor has comparative analysis among different relevant concepts been elaborated. Thus, we attemptted to define inclusive economic development by expanding the definition of inclusive economic growth of Cabeza-García, Del Brio, and Oscanoa-Victorio (Citation2018), proposing that inclusive economic development means the capacity to advance a country's economic growth is developed with the contribution of all citizens, without excluding any important groups in society. Other than being an extension of the concepts of inclusive growth and inclusive economic growth, inclusive economic development can also be treated as a sub-concept of inclusive development, as it is one of the aspects that constitute inclusive development, even in the contexts of different theoretical frameworks or research perspectives (Rauniyar and Kanbur Citation2010; Johnstone Citation2022; Pouw and Gupta Citation2017).

2.2. Measuring inclusive economic development

Although the evaluation of inclusive economic development has not been researched rigorously and thoroughly in the literature, many methodologies have been proposed to measure inclusive economic growth, such as the social opportunity function and indicator system, as demonstrated in .

Table 1. Methods for measuring inclusive economic growth.

Similar to the scenario of conceptualizing inclusive economic growth, the different measurements of inclusive economic growth also bear two shared issues that need to be addressed. Most indicators employ GDP growth (aggregated or per capita) or income growth in evaluating economic progress. This perspective, as mentioned above, still relies on the neo-liberalistic and capitalistic framework. It emphasizes individual wealth accumulation over collective well-being and highlights short-term gains over long-term sustainability. Inclusive growth and inclusive economic growth thus represent a welfare approach to development. It includes generating employment for the poor to improve their living conditions and fostering market competition in the economy (Gupta, Pouw, and Ros-Tonen Citation2015). Therefore, the relevant measurements evaluate the efforts (or the outcome achieved by the efforts) towards fostering economic growth with consideration for inclusion, which does not match the concept of inclusive economic development, which emphysise on growth capacity.

Another issue related to measuring inclusive economic growth is the range of social inclusion aspects considered in the evaluation processes. Income distribution, as the most intuitive inclusive aspect of economic growth, is considered in virtually all measurements, while other aspects, such as participation and social protection, are frequently ignored. The first five methods in exclusively consider income distribution as the embodiment of social inclusion, and the selection of inclusive factors in other methods has been inconsistent.

To address the first issue, we changed the scope of evaluation from measuring output to measuring capacity. We adopted the productivity perspective based on our definition of inclusive economic development. Total factor productivity (TFP) is the portion of the output not explained by the amount of inputs used in production. As such, its level is determined by how efficiently and intensely the inputs are utilized in production (Comin Citation2010). Social inclusion can also be considered an output in TFP estimation, and we thus developed a new indicator reflecting this: inclusive total factor productivity. Our solution to the second issue was based on the theoretical framework of inclusiveness created by Johnstone (Citation2022), which conceptualized inclusive development by identifying universality, plurality, sociality, and relationality in evaluating inclusion. By considering these inclusive aspects as outputs in the TFP estimation process, we measured the capacity to promote economic growth and social inclusiveness of a country with the iTFP indices. The construction of this measure is elaborated in Section 3.

3. Method, variables, and data

3.1. Estimation method

According to the existing literature, the current methods available for measuring TFP include Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA), Solow residual, Domar aggregation, and the index number approach. In this study, we used the DEA method to calculate the Malmquist–Luenberger productivity index, which has several advantages over other methods. The main advantage of DEA is that it does not require any information other than input and output quantities. The efficiency is measured relative to the highest observed performance rather than the average. This nonparametric nature of the DEA method promotes the intuitiveness of results and calculation as well as the flexibility in different theoretical settings and evaluation scales. Meanwhile, linear programming (LP) enabled the DEA method to analyse decision-making units based on multiple inputs and multiple outcomes (Adler, Friedman, and Sinuany-Stern Citation2002; Aldamak and Zolfaghari Citation2017). This multi-input multi-output feature is particularly critical for our definition of inclusive economic development, which includes four aspects of inclusion that consist of multiple indicators for evaluation.

There are also various settings for production technology in TFP estimation, including sequential, biennial, and global production technology settings, which have minor methodological differences. In this study, we chose to use the biennial setting for two reasons. First, although both the global setting and biennial setting can resolve the infeasible problem of linear programming, one may have to recalculate indices of all years when adding a new time period to the dataset due to changes in the technological frontier when using the global setting. In the biennial setting, such a recalculation problem can be avoided since the indices are calculated based on two-year period technological frontiers. Second, the biennial Malmquist–Luenberger productivity index allows for technological regression, which is more aligned with real-world scenarios of inclusive development (Pastor, Asmild, and Knox Lovell Citation2011). These two features enable the iTFP index constructed by biennial production technology to be particularly suitable for evaluating inclusive economic development. The methodological and technological details for estimating the biennial Malmquist–Luenberger productivity index are out of the scope of this study. Interested readers may refer to Pastor, Asmild, and Knox Lovell (Citation2011). Here, we only present the essential steps for estimation to provide an intuitive interpretation of the index.

The directional output distance function models economic growth and social inclusion performance. This function at the time period

with the biennial production technology is defined as:

(1)

(1) where

is a direction vector, and

,

, and

are labor, capital, and energy, respectively.

measures the maximum proportional expansion of both desirable and undesirable outputs

, given the input vector

and biennial technology in direction

. Based on biennial production technology, the biennial Malmquist–Luenberger productivity index is given by:

(2)

(2)

Equation (2) demonstrates that the biennial Malmquist–Luenberger productivity index can be decomposed into two components: technical efficiency change and technological change

. Technical efficiency change indicates catch-up effects, measuring the change in the distance towards the best practice frontier from the time period

to

. Technological change measures technological progress or regression, capturing the degree to which the production function shifts from period

to

by taking biennial production technology as a reference. Because biennial technology is defined as the convex hull of production technologies of the period

and

, it is unnecessary to take the arithmetic mean or geometric mean when determining the biennial Malmquist–Luenberger productivity index.

3.2. Variables

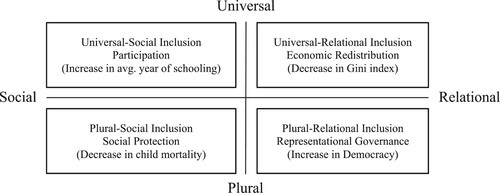

In this study, to evaluate social inclusion as a part of inclusive economic development, we refer to Johnstone (Citation2022) to include the four social inclusion aspects: universal-social, plural-social, universal-relational, and plural-relational inclusion, as desired or undesired outputs in productivity analysis.

The first aspect of inclusion, universal-social inclusion, emphasizes shared opportunities for all social participants. Participation is a suitable indicator as participation initiatives seek to widen the circle of people engaged in and may benefit from economic development. Based on the literature, we used the average year of schooling as an indicator of participation since education can be seen as a precondition of an individual's participation in social contexts based on the occupational perspective. Education enables transformations of the identity and social-economic status of the previously marginalized group through the transitional occupation of students to professionals or workers who ‘have a seat at the table’ in the decision-making processes of social programs (Whiteford Citation2017). The skills and knowledge obtained from secondary and tertiary education empower stakeholders of social development to participate in promoting social inclusion actively. Given the essential role of education in fostering individual and collective wellbeing, a number of participation-widening initiatives have targeted students from a broader range of socio-economic backgrounds to receive a better education, and an increase in the average years of schooling is an expected outcome of successful participation-widening attempts.

The second aspect of inclusion is plural–social inclusion, which aims to promote the well-being of marginalized individuals in society by supporting them to integrate into pre-existing economic systems. Social protection programs are examples of plural–social inclusion due to the targeted nature of their interventions, i.e. grants and efforts designed exclusively for marginalized individuals based on specific categorization standards that are additional benefits beyond what society already provides. In this study, due to data availability, we used child mortality as an indicator of the social protection level, as a decrease in child mortality is one of the primary targets of social protection programs. Empirical evidence has demonstrated a positive relationship between social protection programs and greater use of health services, improved health outcomes for children, and lower child mortality (Li et al. Citation2021).

For the third aspect, universal–relational inclusion, we used economic redistribution to assess progress as redistribution measures aim to promote equality in income among wide-ranging recipients with different backgrounds. We used the Gini index as the indicator, as the more successful the redistribution measures, the lower the income disparity should be. Another important aspect of relational inclusion concerns environmental degradation, as having a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment is a human right. Although many indicators are available for measuring environmental degradation, we used the mean annual exposure of the population to PM2.5 air pollution in this study due to data availability. The literature has demonstrated that higher exposure to PM2.5 particles in the air may correlate with greater negative health effects, including increased incidence of respiratory disease, worsening of respiratory disease symptoms, and cardiovascular effects that can lead to heart attacks and death (McGuinn et al. Citation2019; Xing et al. Citation2016). The guideline set by the World Health Organization (WHO) for PM2.5 is that annual mean concentrations should not exceed 10 micrograms per cubic meter, representing a lower range over which adverse health effects have been observed.

Last but not least, for plural–relational inclusion, we used the democracy and governance levels as the indicators. Intuitively, well-developed democracy and governance systems increase the voices of marginalized people in development processes and enable them to better participate in policy-making processes (Seng Citation2021). The evaluation framework is illustrated in .

Figure 1. Evaluation framework. References: Whiteford (Citation2017), Li et al. (Citation2021), Johnstone (Citation2022).

3.3. Data

The data used in this study were retrieved from a variety of databases, as shown in . Data related to the capital stock, real GDP, and the school year of countries were obtained from the Penn World Table 10.0, an economic database widely used in the literature. Employment data, the child mortality rate, and PM2.5 exposure data were acquired from the World Bank's World Development Indicators database, and the Gini indexes were retrieved from the UNU-WIDER World Income Inequality Database. Although many databases are available for the governance level, the World Governance Indicator covers most countries. By matching these databases, panel data from 80 sampled countries covering the time period 2000–2019 were obtained for further estimations. A small number of missing values were filled by linear interpolation. Summary statistics are reported in .

Table 2. Data definition and sources.

Table 3. Summary statistics of the data.

4. Results and discussion

We estimated the iTFP indices based on the method and data reported in Section 3. provides summary statistics on the indices for the full sample and for developing and developed countries. It is evident that compared to developing countries, the iTFP indexes in developed countries are significantly higher for several reasons. In terms of economic development, developed countries have technological advantages in production that promote the efficiency of the ratio of aggregate output to aggregate inputs, and thus result in a higher iTFP. Meanwhile, the social protection, education, and governance systems are generally more mature in developed economies.

Table 4. Summary statistics of the iTFP estimation results.

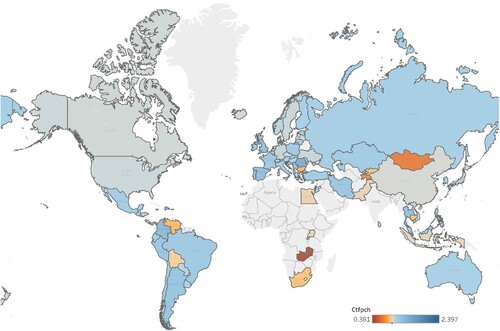

maps the iTFP indices for the year 2019, and presents the indices of five periods in different geographical regions. More detailed evidence is available from the authors on request.

Figure 2. Mapping results of the iTFP indexes.

Notes: The map is colored based on the TFP index in 2019. Source: Author’s calculations.

Table 5. Summary statistics of the iTFP estimation results, categorized by region.

The results showed that, in general, although inclusive economic development is progressing on a global scale, the regional disparity is significant. On average, the iTFP in Oceania is the highest, followed by Europe. In the Americas, although the inclusive economic development performance of Northern America is significant, the disparities across sub-regions are remarkable. The average iTFP of the Caribbean region and Southern America in 2019 was 0.32 and 0.34, respectively—only about 30% of that of Northern America. The average iTFP of Central America was 0.47, about half that of Northern America. The sub-regional disparities are also significant in Europe, but less significant in Asia. However, the overall performance of Asia in inclusive economic development is lower than that of other regions.

These conclusions are comparable to other index systems in the literature, such as the Inclusive Development Index (IDI) developed by the World Economic Forum, the Census-Based Index created by Bisht, Mishra, and Fuloria (Citation2010), and the Multidimensional Inclusiveness Index developed by Dörffel and Schuhmann (Citation2022). However, developed countries are ranked higher, and the regional disparities are more significant in this study. The main reason for these disparities is the focus of evaluation.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we proposed the concept of inclusive economic development as a sub-concept of inclusive development, which can better guide policy and practice to promote inclusive development by precisely identifying the status quo of inclusive development. Based on our comparative analysis of the existing literature concerning the theoretical frameworks of inclusive development, we conceptualized inclusive economic development and proposed its definition: ‘the capacity to advance economic growth with the contribution of all citizens, without excluding any important group of society’. Based on the four-fold conceptual framework of inclusion developed by Johnstone (Citation2022), we constructed our inclusive total factor productivity index based on the data envelopment analysis and the biennial Malmquist–Luenberger productivity index.

Our results suggest that, on average, the iTFP of all countries increased by 2.1% from 2000 to 2019. However, the geographical heterogeneity was significant, and the iTFP indices decreased in several regions, especially Western Asia and Southern America. These results call for more mature measures to promote social inclusion in these regions during economic development processes.

This study, however, has two major limitations that should be addressed in future research. The first limitation is that the biennial Malmquist–Luenberger productivity index measures the relative change in productivity, and the evaluation depends on the collective production technology set. The second limitation is that due to limited data availability, we only included 80 countries in our evaluation. The results presented in this paper must be interpreted with caution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adler, Nicole, Lea Friedman, and Zilla Sinuany-Stern. 2002. “Review of Ranking Methods in the Data Envelopment Analysis Context.” European Journal of Operational Research 140 (2): 249–265. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(02)00068-1

- Aldamak, Abdullah, and Saeed Zolfaghari. 2017. “Review of Efficiency Ranking Methods in Data Envelopment Analysis.” Measurement 106 (August): 161–172. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2017.04.028

- Alekhina, Victoriia, and Giovanni Ganelli. 2021. “Determinants of Inclusive Growth in ASEAN.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy (December): 1–33. doi:10.1080/13547860.2021.1981044

- Ali, Ifzal, and Hyun Hwa Son. 2007. “Measuring Inclusive Growth.” Asian Development Review, Asian Development Review 24 (1): 11–31.

- Anand, Rahul, Saurabh Mishra, Shanaka J. Peiris, and Paul Cashin. 2013. “Inclusive Growth: Measurement and Determinants.” IMF Working Papers 2013 (135): 3–15.

- Aoyagi, Chie, and Giovanni Ganelli. 2015. “Asia’s Quest for Inclusive Growth Revisited.” Journal of Asian Economics 40 (October): 29–46. doi:10.1016/j.asieco.2015.06.005

- Barro, Robert J., and Jong Wha Lee. 2013. “A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950–2010.” Journal of Development Economics 104 (September): 184–198. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2012.10.001

- Barua, Alokesh, and Aparna Sawhney. 2015. “Development Policy Implications for Growth and Regional Inequality in a Small Open Economy: The Indian Case.” Review of Development Economics 19 (3): 695–709. doi:10.1111/rode.12154.

- Bassier, Ihsaan, and Ingrid Woolard. 2021. “Exclusive Growth? Rapidly Increasing Top Incomes Amid Low National Growth in South Africa.” South African Journal of Economics 89 (2): 246–273. doi:10.1111/saje.12274

- Bisht, Shailendra Singh, Vishal Mishra, and Sanjay Fuloria. 2010. “Measuring Accessibility for Inclusive Development: A Census Based Index.” Social Indicators Research 98 (1): 167–181. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9537-3

- Brand, Ulrich, Tobias Boos, and Alina Brad. 2017. “Degrowth and Post-Extractivism: Two Debates with Suggestions for the Inclusive Development Framework.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 24 (February): 36–41. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.007

- Cabeza-García, Laura, Esther Del Brio, and Mery Oscanoa-Victorio. 2018. “Gender Factors and Inclusive Economic Growth: The Silent Revolution.” Sustainability 10 (2): 121. doi:10.3390/su10010121

- Cabeza-García, Laura, Esther B. Del Brio, and Mery Luz Oscanoa-Victorio. 2019. “Female Financial Inclusion and Its Impacts on Inclusive Economic Development.” Women's Studies International Forum 77 (November): 102300. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2019.102300.

- Clifford Simplican, Stacy. 2019. “Theorising Community Participation: Successful Concept or Empty Buzzword?” Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 6 (2): 116–124. doi:10.1080/23297018.2018.1503938

- Comin, Diego. 2010. “Total Factor Productivity.” In Economic Growth, edited by Steven N. Durlauf, and Lawrence E. Blume, 260–263. The New Palgrave Economics Collection. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Dollar, David, Tatjana Kleineberg, and Aart Kraay. 2016. “Growth Still Is Good for the Poor.” European Economic Review 81 (January): 68–85. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.05.008.

- Dollar, David, and Aart Kraay. 2002. “Growth Is Good for the Poor.” Journal of Economic Growth 7 (3): 195–225. doi:10.1023/A:1020139631000

- Dörffel, Christoph, and Sebastian Schuhmann. 2022. “What Is Inclusive Development? Introducing the Multidimensional Inclusiveness Index.” Social Indicators Research 162 (3): 1117–1148. doi:10.1007/s11205-021-02860-y

- Feenstra, Robert C., Robert Inklaar, and Marcel P. Timmer. 2015. “The Next Generation of the Penn World Table.” American Economic Review 105 (10): 3150–3182. doi:10.1257/aer.20130954

- Fourie, Frederick. 2014. “How Inclusive Is Economic Growth in South Africa?” Econ 3×3 September: 1–8.

- Gupta, Joyeeta, and Nicky Pouw. 2017. “Towards a Trans-Disciplinary Conceptualization of Inclusive Development.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 24 (February): 96–103. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.03.004

- Gupta, Joyeeta, Nicky R M Pouw, and Mirjam A F Ros-Tonen. 2015. “Towards an Elaborated Theory of Inclusive Development.” The European Journal of Development Research 27 (4): 541–559. doi:10.1057/ejdr.2015.30

- Haan, Arjan de. 2015. “Inclusive Growth: Beyond Safety Nets?” The European Journal of Development Research 27 (4): 606–622. doi:10.1057/ejdr.2015.47

- Jiang, Aichun, Chuan Chen, Yibin Ao, and Wenmei Zhou. 2021. “Measuring the Inclusive Growth of Rural Areas in China.” Applied Economics May: 1–14.

- Johnstone, Christopher J. 2022. “Conceptualising Inclusive Development by Identifying Universality, Plurality, Sociality, and Relationality.” Journal of International Development January: jid.3622.

- Kang, Hyojung, and Jorge Martinez-Vazquez. 2021. “When Does Foreign Direct Investment Lead to Inclusive Growth?” The World Economy December: twec.13236.

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2011. “The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues.” Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 3 (2): 220–246. doi:10.1017/S1876404511200046

- Khan, Azra, Gulzar Khan, Sadia Safdar, Sehar Munir, and Zubaria Andleeb. 2016. “Measurement and Determinants of Inclusive Growth: A Case Study OfPakistan (1990-2012).” The Pakistan Development Review 55 (4): 455–466. doi:10.30541/v55i4I-IIpp.455-466.

- Kjøller-Hansen, Anders Oskar, and Lena Lindbjerg Sperling. 2020. “Measuring Inclusive Growth Experiences: Five Criteria for Productive Employment.” Review of Development Economics 24 (4): 1413–1429. doi:10.1111/rode.12689

- Klasen, Stephan. 2010. “Measuring and Monitoring Inclusive Growth: Multiple Definitions, Open Questions, and Some Constructive Proposals.” Sustainable Development Working Papers, no. 12 (June). https://www.adb.org/publications/measuring-and-monitoring-inclusive-growth-multiple-definitions-open-questions-and-some.

- Koralagama, Dilanthi, Joyeeta Gupta, and Nicky Pouw. 2017. “Inclusive Development from a Gender Perspective in Small Scale Fisheries.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, Sustainability Science 24 (February): 1–6.

- Kuznets, Simon. 1984. “Economic Growth and Income Inequality.” In The Gap Between Rich and Poor, edited by Mitchell A. Seligson, 22–35. New York: Routledge.

- Lauth, Hans-Joachim, and Schlenkrick Oliver. 2021. Democracy Matrix Codebook. Würzburg: Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg. www.democracymatrix.com.

- Li, Zhihui, Xinyan Zhou, Shuyao Ran, and Fernando C Wehrmeister. 2021. “Social Protection and the Level and Inequality of Child Mortality in 101 Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Statistical Modelling Analysis.” Journal of Global Health 11 (04067): 1–11.

- Mamat, Mohd Zufri, Boon-Kwee Ng, Suzana Ariff Azizan, and Lee Wei Chang. 2016. “An Attempt at Implementing a Holistic Inclusive Development Model: Insights from Malaysia's Land Settlement Scheme.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 57 (1): 106–120. doi:10.1111/apv.12115.

- McGuinn, L. A., A. Schneider, R. W. McGarrah, C. Ward-Caviness, L. M. Neas, Q. Di, J. Schwartz, et al. 2019. “Association of Long-Term PM2.5 Exposure with Traditional and Novel Lipid Measures Related to Cardiovascular Disease Risk.” Environment International 122 (January): 193–200. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2018.11.001

- McKinley, Terry. 2010. “Inclusive Growth Criteria and Indicators: An Inclusive Growth Index for Diagnosis of Country Progress.” Sustainable Development Working Papers, no. 14 (June). https://www.adb.org/publications/inclusive-growth-criteria-and-indicators-inclusive-growth-index-diagnosis-country.

- Mitra, Siddhartha. 2017. “A Note on Measuring Inclusive Growth and the Inclusiveness of Growth.” South Asian Journal of Macroeconomics and Public Finance 6 (2): 194–208. doi:10.1177/2277978717727168

- Ngepah, Nicholas. 2017. “A Review of Theories and Evidence of Inclusive Growth: An Economic Perspective for Africa.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 24 (February): 52–57. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.008

- Pastor, Jesús T., Mette Asmild, and C. A. Knox Lovell. 2011. “The Biennial Malmquist Productivity Change Index.” Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 45 (1): 10–15. doi:10.1016/j.seps.2010.09.001

- Pouw, Nicky, and Joyeeta Gupta. 2017. “Inclusive Development: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 24 (February): 104–108. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2016.11.013

- Prada, Albino, and Patricio Sánchez-Fernández. 2019. “Transforming Economic Growth Into Inclusive Development: An International Analysis.” Social Indicators Research 145 (1): 437–457. doi:10.1007/s11205-019-02096-x

- Ran, Li, Xiaodong Tan, Yi Xu, Kaiyu Zhang, Xuyu Chen, Yuting Zhang, Mengying Li, and Yupeng Zhang. 2021. “The Application of Subjective and Objective Method in the Evaluation of Healthy Cities: A Case Study in Central China.” Sustainable Cities and Society 65 (February): 102581. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2020.102581

- Rauniyar, Ganesh, and Ravi Kanbur. 2010. “Inclusive Growth and Inclusive Development: A Review and Synthesis of Asian Development Bank Literature.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 15 (4): 455–469. doi:10.1080/13547860.2010.517680

- Risso, W. Adrián, Lionello F. Punzo, and Edgar J. Sánchez Carrera. 2013. “Economic Growth and Income Distribution in Mexico: A Cointegration Exercise.” Economic Modelling 35 (September): 708–714. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2013.08.036

- Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. 2020. “Energy.” Our World in Data. November 28, 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/energy.

- Rubin, Amir, and Dan Segal. 2015. “The Effects of Economic Growth on Income Inequality in the US.” Journal of Macroeconomics 45 (September): 258–273. doi:10.1016/j.jmacro.2015.05.007

- Seng, Kimty. 2021. “Inclusive Legal Justice for Inclusive Economic Development: A Consideration.” Review of Social Economy 79 (4): 749–783. doi:10.1080/00346764.2020.1720792

- Sharafutdinov, Rustam Ilfarovich, Elvir Munirovich Akhmetshin, Aleksandra Grigorievna Polyakova, Vladislav Olegovych Gerasimov, Raisa Nikolaevna Shpakova, and Mariya Vladimirovna Mikhailova. 2019. “Inclusive Growth: A Dataset on Key and Institutional Foundations for Inclusive Development of Russian Regions.” Data in Brief 23 (April): 103864.

- Sun, Caizhi, Ling Liu, and Yanting Tang. 2018. “Measuring the Inclusive Growth of China’s Coastal Regions.” Sustainability 10 (8): 2863. doi:10.3390/su10082863

- UNU-WIDER. 2021. World Income Inequality Database (WIID). Version 31 May 2021.

- Wang, Xuxia, and Shanshan Wang. 2020. “The Impact of Green Finance on Inclusive Economic Growth<br/>—Empirical Analysis Based on Spatial Panel.” Open Journal of Business and Management 08 (05): 2093–2112. doi:10.4236/ojbm.2020.85128.

- Whajah, Jennifer, Godfred A. Bokpin, and Saint Kuttu. 2019. “Government Size, Public Debt and Inclusive Growth in Africa.” Research in International Business and Finance 49 (October): 225–240. doi:10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.03.008

- Whiteford, Gail. 2017. “Participation in Higher Education as Social Inclusion: An Occupational Perspective.” Journal of Occupational Science 24 (1): 54–63. doi:10.1080/14427591.2017.1284151

- Woo, Jaejoon. 2011. “Growth, Income Distribution, and Fiscal Policy Volatility.” Journal of Development Economics 96 (2): 289–313. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.10.002

- World Bank. 2021. World Development Indicators. Washington, D.C: World Bank.

- Xing, Yu-Fei, Yue-Hua Xu, Min-Hua Shi, and Yi-Xin Lian. 2016. “The Impact of PM2.5 on the Human Respiratory System.” Journal of Thoracic Disease 8 (1): E69–E74.