ABSTRACT

This study seeks to investigate firm-level innovation, exploring whether social relationships located in knowledge networks influence the transfer of university knowledge to Ghanaian firms. Firms’ informal relationships with universities have been under-researched in developing economies. The extant literature suggests that informal relationships in the context of economies with advanced regional and national innovation systems have a positive association with firm level innovation performance. The research project employs a cross-sectional survey of 245 firms in Ghana. The aim of the project is to explore the influence of informal mechanisms of university knowledge transfer on firm level innovation performance in Ghana. The study adopts a structural model with partial least squares as an analytical technique. The findings reveal that to deliver positive results in a firm’s innovation performance by informal means, a well-coordinated social system to attract research knowledge from all aspects of the university system is required. The research project’s implications for Ghana’s innovation system include a need to be aware of the impact of corruption and lack of intellectual property rights on the efficacy informal knowledge transfer.

Introduction

The transfer of knowledge from universities to industry is important for firms’ market competitiveness (Lam Citation2000; Victoria et al. Citation2015). As a result, there is the need for university generated knowledge to be more industry focused to support economic growth (Gibbons et al. Citation1994). Accordingly, universities are now under pressure to account for public investment and cannot therefore continue to be ‘Ivory Towers’ (Caniels and Van den Bosh Citation2011). Extant knowledge generation in universities and subsequent effective transfer to industry literature is typically undertaken in economically advanced nations (Hobday Citation2005; Léger and Swaminathan Citation2007). Further, most research undertaken in university knowledge generation typically adopts a qualitative paradigmatic approach, this may limit the generalisability of research findings. This leaves a knowledge gap in the literature on universities’ impact on industry in developing economies (Barnes, Pashby, and Gibbons Citation2002; Hobday Citation2005). Another issue is that university knowledge transfer literature (Hamilton and Philbin Citation2020; Cheng Citation2020) tends to concentrate on formal collaboration, contract research and joint research involving patents, licencing, and spinoffs, once again, conducted in economically advanced nations (Cohn Citation2013; Hughes and Kitson Citation2012). Furthermore, Mendoza-Silva (Citation2020) identifies the need to undertake research into the relationship between informal networks and the innovation capability of firms.

Historically, Ghana’s budget statements link knowledge and innovation requirements to actual global economic trends in an environment of persistent international trade deficits (Minister for Finance Citation2015). Amidst improvement in the knowledge of the market and a constant influx of foreign products and services, the Government of Ghana has called for private sector involvement in economic growth and development. These pleas hinge on the need for new technological solutions to help grow the economy. In addition, there is pressure on knowledge generation actors to ensure that academia and industry work closely together in a productive co-ordinated manner.

Social capital is omnipresent in Ghana, permeating through every facet of society (Adjargo Citation2012). Adjargo (Citation2012) states, Ghanaians employ social capital as a means to support informal mechanisms of innovative technology being transferred to, and being adopted by, Ghanaian farmers. Indeed, given the low level of literacy in Ghana (69.8%), particularly in the rural areas (Ghana Population and Housing Census Citation2021), informal mechanisms of university knowledge transfer, supported by social capital, may facilitate knowledge transfer. For instance, Ghanaians live in communities, clans, groups and tribes, and adopt a community-based approach for issues of security, information sharing and knowledge dissemination (Bonye, Thaddeus, and Owusu-Sekyere Citation2013). University researchers form part of the communities and traditionally are typically duty bound to informally offer guidance given their access to university research knowledge. Dissemination of knowledge through informal means and networks may help increase levels of innovative activity. Research undertaken into how such dissemination can be more efficiently and effectively undertaken will be beneficial for Ghana and other developing economies. Through informal mechanisms, university knowledge may trickle down to communities and help work towards resolving global inequalities.

Idea exploitation and the commercial interest of industry, universities and the Government of Ghana have shaped the focus of this research. Namely, to provide empirical data relating to the influence of social relations and knowledge networks on firm level innovation performance. For instance, social networks are documented as enablers of interpersonal relationships among firms and a fertile ground for intellectual capital creation, as an outcome of social capital (Huggins and Johnson Citation2012). In the knowledge generation infrastructure, universities often form the hub around which exchange of knowledge revolves. In view of this, the study seeks to analyse the significance of social relations and knowledge networks in university knowledge transfer for Ghanaian firms’ innovation performance. The study also intends to offer empirical explanations on the roles of social relations and knowledge networks in the knowledge transfer process in developing West African countries per se. Indeed, social networks resultant of of social capital are said to contribute to network capital, that helps tie firms together in inter-organizational knowledge networks (Huggins and Johnson Citation2012). To explore this, the study uses partial least squares structural equation modeling to investigate the influence of informal knowledge transfer mechanisms and knowledge networks on firms’ innovation in Ghana, with the research focus on incremental dimensions rather than radical. To underpin the study objectives, three hypotheses are created from extant literature to investigate empirical data with a resulting structural model as our conceptual framework.

For the rest of the paper, the second section covers a critical review of available literature where a conceptual model is developed with three proposed hypotheses for analysis. In the third section, data collection, methods of sampling and use of analytical tools are discussed leading to findings in section four and discussions in section five. The final section is the conclusion which also contains the policy implications, limitation, and recommendations for further studies.

Literature review

Universities’ interactions with industry are essential for their mutual good (D’Este and Patel Citation2007; Rossi and Rosli Citation2013) and for value creation (Van Horne, Poulin, and Frayret Citation2010). Such interactions with firms helps universities gain industry experience, obtain data, develop new methods and extend the boundaries of knowledge, and crucially, attract private funding from industry. Consequently, firms achieve their business objectives through improved business practices and more efficient use of technology to solve their production problems (Kaymaz and Eryiğit Citation2011; Bradley et al., Citation2013). Universities traditionally have been the providers of mass education, development of a skilled workforce and involved in curiosity-driven research. Notably, World economic crises in recent decades have led to universities employing a third stream of responsibility by engaging industry to transfer knowledge for commercial benefit and wealth generation (Guimon Citation2013; Abdulai, Murphy, and Thomas Citation2015).

Accordingly, governments have also encouraged this paradigm shift and influenced university involvement with industry through knowledge transfer initiatives. Here, there have been interventions to strengthen entrepreneurial activities with procedural machinery such as technology transfer offices and innovation centers. Finally, current global economic development policies encourage an increase in universities’ interactions with businesses to be able to self-fund their research projects (Etzkowitz et al. Citation2000; Hagedoorn et al. Citation2000). A test case is the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 in the US, which formed a policy framework where proprietorship of university research outcomes is explicitly clear in its conditions, resulting in federal government funded research project outcomes a university bona fide (Deiaco, Hughes, and McKelvey Citation2012). In the Ghanaian context, political independence from British rule in 1957 led the young sovereign nation to set up universities primarily to train a more skilled and productive workforce for the new state Research was also encouraged to support significant technological development for its then comparatively fragile economy. From this time, economic development and industrialization were top of the government agenda. For the Ghana government and its business community, knowledge, science and technology would drive government machinery for economic growth leading to an expected ‘trickledown’ effect on the social lives of citizen (Sawyerr Citation2004; MEST Citation2010).

Unfortunately, several decades after the declaration of independence, a report by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in Citation2013 described co-operation and co-ordination among institutional players set up by the Ghana Government to govern science, technology, and innovation as weak and dysfunctional (OECD Citation2013). Similarly, policy frameworks over the years, designed for science, technology and innovation lacked the needed focus on economic growth and development priorities. It follows then, that policy makers in Ghana did not have the necessary awareness and capacity to set national goals (OECD Citation2013). As a consequence, science, technology and innovation (STI) strategies implemented by past Ghana governments, according to MEST (Citation2010), made limited impact on the lives of ordinary Ghanaians.

Other Ghanaian context concerns include levels of corruption and intellectual property rights. Comparatively high levels of corruption in Ghana (Transparency International Citation2021) typically negatively impact on Ghana’s development (Forson et al. Citation2015; Asomah Citation2021). Intellectual property rights are also a principle factor influencing knowledge transfer and innovation levels. The application of intellectual property rights is open to interpretation in developing countries. A strict application of intellectual property rights may stifle a country like Ghana’s development (De Beukelaer and Fredriksson Citation2019). A conflicting view presented by Lui (Citation2016) is the development of lower-income countries such as Ghana would benefit from robustly implemented intellectual property rights. To reconcile these different viewpoints, Adams (Citation2008) states intellectual property rights should be designed to complement a country’s stage of development. Consequently, Ghanaian intellectual property legislation should reflect its stage of development.

In line with the Ghanaian practical situation describes above, critics of innovation frameworks, particularly that of the Bayh-Dole Act (1980) in the USA, have contended that there is no convincing evidence of any direct impact of such policies (Janz, Lööf, and Peters Citation2004; Mowery and Sampat Citation2005). Notwithstanding, this policy framework has been adopted as a model instrument for a number of governments. For instance, some governments in OECD countries such as Denmark and Germany (Geuna and Muscio Citation2009) have replicated it to encourage their universities to work together with industry to strengthen regional and national innovation systems and facilitate social and economic growth and development (Mowery and Sampat Citation2005). This study seeks to offer guidance to Ghanaian policy makers on how informal knowledge access may be harnessed to increase firms’ level of innovative activity and consequently, Ghana’s economic development.

Knowledge transfer is a fundamental determinant of firms’ innovative activity which consequently may accelerate economic growth and social development (Tekic et al. Citation2013). As a result, scholars of knowledge of the firm (Kogut and Zander Citation1992, Citation1993) and university knowledge transfer (Hamilton and Philbin Citation2020; Cheng Citation2020) recognize the significance of different types of mechanisms available to firms to influence knowledge production. Additionally, informal interactions between university faculty members and firms are known to lead to innovation in firms and further to formal collaborations and productive partnerships (Bradley et al., 2013). Informal mode of university knowledge transfer is the transfer of knowledge through personal contacts between university researchers and entrepreneurs and facilitated by interactions within social networks, for example, meetings, and at conferences. It is known for its extensive tacit characteristics in its mode of diffusion and believed to facilitate the flow of technological knowledge through informal communication process (De Wit de Vries et al. Citation2019). However, the difference between formal and informal mechanisms is blurred and difficult to identify. A reason for this is personal agreements may lead to formal relationships and therefore becomes legally binding on consenting parties. Known for its extensive codification prominence and strict procedural machinery for generation, studies show that formal mode of university knowledge transfer typically encompasses a legal contract between a university and a firm. The definition remains ambiguous though, inviting controversies among researchers (Thomas, Brooksbank, and Thompson Citation2009). Nonetheless, in most formal university knowledge transfer there are specific target outcomes to be achieved (Muscio, Quaglione, and Vallanti Citation2013). It is stated in the literature that firms which use both formal and informal mechanisms of knowledge are more likely to benefit from external knowledge sourced at universities (Howells, Ramlogan, and Cheng Citation2012; Grimpe and Hussinger Citation2013).

Typically, any informal process through which knowledge is transferred to firms from universities is often referred to as ‘gray market’ in the technology transfer literature (Bradley et al., 2013). de Wit, Dankbaar, and Vissert (Citation2007) explain that the grey market is under-researched and claim though that firms cannot rely totally on interpersonal relations with university researchers for innovation and competence development. Internal firm R&D they suggest should be enhanced to support absorptive capacities for external knowledge inflow and not rely only on freely disseminated knowledge, which has little or no substantial evidence of innovation outcomes. It is expected that most firms, particularly in developing economies, use informal interactions to strengthen their knowledge capability (Mowery and Sampat Citation2005). Evidence from the US manufacturing sector indicates that 90% of university partnerships in a corporate research environment are initiated through informal contacts (Hagedoorn et al. Citation2000). Although, Hagedoorn et al. (Citation2000) warns that the informal mode of knowledge transfer can at times be difficult to evidence. Rossi and Rosli (Citation2013) add that open disseminated sources of knowledge have no substantial of impact on firms’ intellectual property nor national economic growth and development. In Ghana, informal mechanisms of knowledge transfer are typically used by firms because the majority of them are small, with comparatively fewer resources and lack of capacity to absorb higher level technology developments (Fu et al. Citation2014).

In summary, irrespective of the mechanism (formal or informal means), knowledge transfer from universities to industry may now be considered to be a fundamental aspect of firms’ knowledge and learning process, and a start point of economic success for regions and nations (Abdulai, Murphy, and Thomas Citation2015). Geuna and Muscio (Citation2009) assert that workshops, conferences, seminars, and other informal mechanisms of knowledge transfer, in general, are recognized as interactions which facilitate the sharing of knowledge. They argue that most formal collaborations and all sorts of partnerships gain their routes from informal links. In effect, universities need industry for financial support for research projects, and industry also needs university-generated research outcomes to create wealth and remain competitive in the market. With the mechanisms discussed, stakeholders have an eminent role to play to improve the effectiveness of university-industry interactions (Siegel et al. Citation2003). Consequently, this research paper focuses on how social interactions can be harvested in the knowledge generation space for the benefit of Ghanaian firms’ innovation performance.

Firm-based knowledge is often considered to be a source of competitive advantage (Cooke and Leydesdorff Citation2006). Firms as social entities, generate knowledge internally, exchange with other firms and institutions through several mechanisms in a complex network (Kogut and Zander Citation1992, 1993). Moreover, within the firm exists a knowledge-base and it is predominantly tacit; residing in individual employes and is difficult to replicate by competitors (Smith Citation2001; Su, Lin, and Chen Citation2015). Also, explicit knowledge is another form of a firm’s knowledge, a resource that is codified and easy to emulate through social contacts and externalities (Smith Citation2001; Takeuchi Citation2013).

Additionally, from an epistemological point of view, individuals are essentially the primary agents of the firm’s knowledge capability (Smith Citation2001; Audi Citation2011). However, people often move within their social networks due to labor mobility and this may impact on firm-level knowledge (Kogut and Zander Citation1992). This indicates that firms should ideally be the custodians of their own knowledge. Thus, they preserve the knowledge, norms, beliefs, behaviors, cultures, and values, thereby maintaining the organisational innovative momentum which may contribute to competitive advantage (Edelman et al. Citation2004).

Firms learn through codified knowledge that is scientific and technical in content – known as the Science, Technology, and Innovation (STI) mode of learning (Smith Citation2001). Other firms may learn through the experienced-based mode of learning; thus, Doing, Using, and Interacting (DUI) mode (Smith Citation2001). Depending on the context, extant literature shows that the two have been effective in firm competence building at both the regional and national economic development levels (Smith Citation2001). Even with either modes of knowledge in firms, evidence further suggests that firms can no longer survive in isolation (Pittaway et al. Citation2004). This is because the growing demand of complex knowledge-based economies requires firms to take full advantage of knowledge stockpile found in knowledge networks (Cooke and Leydesdorff Citation2006). As Chesborough (Citation2003) states; ‘ … not all of the smart people in the world work for us’. This suggests that effective interaction with other institutions is vital for firm-level innovation (Abdulai, Murphy, and Thomas Citation2015). Note also, that Pittaway et al. (Citation2004) warn of network failures and limitations, showing that inter-firm conflicts could arise among firms. Further, when firms join local, national, or international networks they may benefit from lower transaction costs and risk sharing search for knowledge (Murphy, Huggins, and Thompson Citation2015). A study by Cadger et al. (Citation2016) reveals that knowledge transfer and exchange are effective among farmers who develop good social ties and belong to social networks. Farmers have more exposure to new and innovative agro-ecological practices in Ghana (Cadger et al. Citation2016).

Innovation may be considered to be a key driver of economic growth and development. Consequently, both public and private organizations may benefit from connecting with individuals, experts, firms, and institutions to enhance innovative performance (OECD Citation1997; Clancy and Moschini Citation2013). Governments have played the role of facilitation in industry-university interactions as proposed by Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff (Citation1997, Citation2000). Such interactions may take place in the context of the Triple Helix framework where an interface is created amongst industries, universities and governments to co-produce knowledge for innovation. In this framework, actors assume the traditional role of each other in an ‘innovation space’ (Etzkowitz Citation2002). Although, the Triple Helix framework is heavily criticized for both theoretical and practical reasons, Tunnainen (Citation2002) suggests that the framework has yielded empirical data that calls for future research. For instance, the UK Government is an example with its Research Excellence Framework (REF), which brings in substantial funding for highly ranked universities in areas that yield research results for direct application in industry. Universities can help improve levels of technological innovation and increase the innovative momentum of firms. (Kaymaz and Eryiğit Citation2011).

Innovation happens in a complex network of interconnected structures and institutions interacting in feedback loops seeking relevant innovation for social growth and economic development (Edquist Citation2001). A loop made of institutions, universities, firms and government agencies. Innovation system theory seeks to explain the generation and transmission of knowledge and technology for firm’s innovation performance (Mosey, Wright, and Clarysse Citation2012). For instance, a national innovation system is the purposive formal interactions that take place among firms, universities, and other stakeholders for the purpose of gaining commercialization, patents, and co-publications. In this system, knowledge exchange for innovation in firms also emanates from informal linkages, where technology and information diffusion, personnel mobility, and technical staff move between public and private sector firms are common (Dooley and Kirk Citation2007). For Nelson and Winter (Citation1982) and Rosenberg (Citation1982) innovation is a process that brings improvement in solving problems whether business or social, for example, newness in method. Unfortunately, the lack of full understanding on how and whether innovation really affects firms’ performance is due to lack of bespoke framework to help determine that in the existing body of knowledge. Nevertheless, Geroski (Citation1994) explains the impact of innovation on firm’s performance to manifest in, among other things, its introduction of new processes, product differentiation and marketing, and the ability of a firm to enhance its internal capabilities to respond to market pressures.

For innovation performance, there is a wide variety of university knowledge transfer mechanisms and activities that firms strategically select depending on which suits their area of operation, discipline, industry and even interest (Bradley et al., 2013). Mostly, micro and small enterprises, even start-ups, particularly in low-income countries, rely on their casual contacts with university researchers, which are considered informal form of university knowledge transfer (Bailey, Cloete, and Pillay Citation2011). Other recognised informal sources available in the literature are knowledge spillovers, conferences, student placements, workshops, and labour mobility where they acquire knowledge or absorb new ideas to achieve incremental changes (Pittaway et al. Citation2004).

In addition, networks offer seemingly limitless opportunities in the knowledge value chain for new products and services to be developed (Chesborough Citation2003). Indeed, the development of network theory has enriched further understanding of the relevance of knowledge networks in knowledge transfer process including knowledge from universities. However, our understanding of their formations and relevance to firms’ innovation performance in developing countries still remains largely unknown. Arguably, knowledge networks are central to university knowledge transfer that often leads to increased organisational efficacy and economic sustainability (Huggins and Johnson Citation2012). To a large extent, firms in specific geographical areas and disciplines are encouraged to form networks to absorb university knowledge and re-enforce innovation processes (Huggins and Johnson Citation2012). Network theory places emphasis on network members’ exploitation of low transaction costs advantages and risk sharing (Murphy, Citation2011). It may be statedthat no individual organisation holds all expertise and resources to exclusively develop successful innovation and will require supportive network input at some point (Chesborough Citation2003). To further support this, in a review of evidence of networking for innovation, Pittaway et al. (Citation2004) indicates that firms that do not network either formally or informally stand little chance of accumulating competitive organisational knowledge base to stand competition in the twenty-first century.

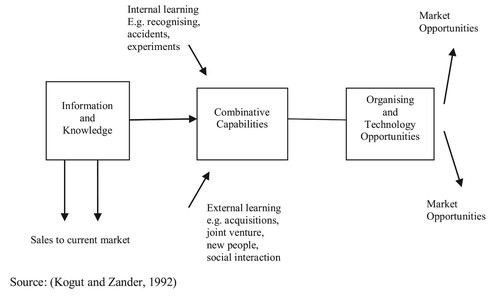

shows how firms accumulate both tacit and explicit knowledge internally and externally to gain competitive advantage and remain profitable (Smith Citation2001). The hypotheses below are created within the remits of firm’s knowledge acquisition process as documented in extant literature. In their argument, Kogut and Zander (Citation1992) support the claim that knowledge within a firm is a combination of internal and external learning processes that serve as a foundation upon which economically valuable products and services can be realized. A pragmatic approach on how firms generate new knowledge suggests that firms combine their capabilities to learn new skills and increase their core competence. The combined capabilities encompass several elements including know-how based on internal and external learning mechanisms. In principle, this supports the creation of a research model to help interpret the relevance of social interactions through knowledge networks and inter-organisational links in an innovation system (Lam Citation1997).

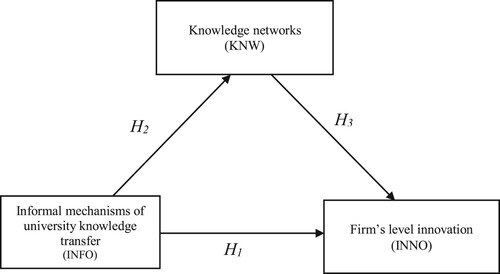

Our conceptual model in is sourced broadly in the innovation systems theory (Lundvall Citation1992; Freeman Citation1995), network theory (Huggins, Johnson, and Steffenson Citation2008; Huggins and Johnson Citation2012), organisational learning theory (Smith Citation2001), the theory of the firm (Kogut and Zander Citation1992, 1993) and the theory of social capital (Edelman et al. Citation2004; Murphy, Huggins, and Thompson Citation2015). We integrate these theories to help explain firm-based knowledge and how informal university knowledge transfer mechanisms and knowledge networks (Hamilton and Philbin Citation2020; Cheng Citation2020), support internally generated knowledge. We eventually draw these from the framework by Kogut and Zander (Citation1992) in to explain the significance of interpersonal relationships, knowledge networks and their impact on the knowledge base of the firm.

To empirically examine the theory, we adopt the structural model in with the aid of our research hypotheses drawn from extant literature. In their framework, Kogut and Zander (Citation1992) link the knowledge-base of the firm to external social institutions to include both private and public research organisations and universities. Purposely, this is an attempt to explain how firms acquire knowledge from the networks within which they are embedded. Our primary concern here is the benefit of social capital; thus, informal interactions through which firms learn and equip themselves with knowledge to remain competitive.

Naturally, the knowledge of firms is socially embedded (Adler and Kwon Citation2000; Nahapiet and Ghoshal Citation2000) and invariably accounts for the diverse nature of business activities across varying firms in different geographic locations (Lam Citation2000; Howells, Ramlogan, and Cheng Citation2012). As a social community, firms are a repository of knowledge and influenced by internal operational structures and the capacity to acquire knowledge from external sources for their combinative capabilities (Kogut and Zander Citation1993; Autio, Hameri, and Vuola Citation2004). Significantly, external social organisations, networks and sub-networks may determine what happens to knowledge acquisition in firms Kogut and Zander (Citation1992). There is little understanding in economically developing economies on how innovation affects business performance. On this basis, the following hypotheses are developed from the literature to empirically investigate the link between the social dynamics of knowledge transfer and firms’ innovation performance in Ghana:

H1: Informal mechanism of university knowledge transfer is positively associated with innovation in firms in Ghana.

H2: Informal mechanism of university knowledge transfer is positively associated with knowledge networks in Ghana.

H3: Knowledge networks are positively associated with innovation performance in firms in Ghana.

Research methodology

The data is collected through a primary source in a cross-sectional survey in Ghana and involved firms across three sectors of the Ghanaian economy, namely primary, manufacturing and service sectors. In the absence ofan innovation database with well-defined indicators in Ghana, an instrument has been designed taking into consideration the requisite conditions to reduce all forms of biases for validity and reliability. The self-administered survey was completed by senior-level staff at the firms in the sample. The instrument was a 5-point Likert scale questionnaire which was pretested (Punch Citation2005) and reliability test values were as high as 0.82 (Cronbach α). It is designed to obtain information based on the experiences and knowledge of respondents on forms of informal relationships their firms had with universities and other knowledge sources, for innovation performance (Gorard Citation2003).

To measure innovation performance, both soft and tangible elements were considered to ensure validity. Responses are elicited on innovation such as changes made to products and processes, and budgetary allocation for R&D. Then, changes in marketing strategies, general newness in methods, capacity building and management style are considered. For informal mechanism, a relationship with at least one university academic is included, as is, interest in published academic literature and general association with university research staff at personal level. Finally, with knowledge networks, firms’ connections with groups and associations available for knowledge dissemination are rated by respondents, another is firms’ openness to external sources knowledge consortia and strategic partnerships.

All firms in the survey were private and included: wholesale, retail and processing firms, knowledge delivery and ICT organisations. Stratified simple random sampling method was employed for the sectors, intended to obtain a well-represented sample of data (Cohen and Manion Citation1985; Krippendorff Citation2004). Two databases from the Association of Ghana Industries (AGI) and National Small Scale Industries (NBSSI) were accessed to obtain a sample frame of 800 firms. The three industry sectors are considered and 245 usable questionnaires were collected with two follow-ups to obtain a 30.63% response rate (Podsakoff et al. Citation2003). For a medium effect size of 0.10, a sample size of 100 was estimated a priori for a power of 0.80 (Cohen Citation1992).

On non-response bias checks, there was no statistically significant difference between early and late respondents in their responses with respect to all the variables and can be seen in , thus; t(243) = −0.598, p = 0.550 for INFO, the associated Levene’s test for equal variance is F(243) = 0.489, p = 0.485. For KNW; t(243) = −1.35, p = 0.178, Levene’s is not significant; F(243) = 0.389, p = 0.529 and for INNO, t(243) = 0.006, p = 0.995 and Levene’s test is F(243) = 0.054, p = 0.817. Normality assessment with a Shapiro–Wilk test results were acceptable with the exception of KNW, which, on graphical inspection was good. Also, Herman’s single-factor test with Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using unrotated loadings showed no evidence of common method bias as no single factor accounted for all the variances in the variables nor more than 50% of the variances in the variables either.

Table 1. Assessment of non-response bias with 2-tailed t-test at 5% level.

Results – partial least squares structural equation modelling

Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) is employed with WarpPLS v5.0 statistical package and PLS regression algorithm to explore the conceptual relationships between the variables (Urbach and Ahlemann Citation2010). It is a technique specifically designed to analyse causal relationships between theoretical concepts or models involving multiple constructs with multiple measures as in this study. In typical PLS-SEM-based research, researchers formulate theories where effects or relationships are hypothesized to manifest in a certain direction for empirical testing and is currently widely used (Henseler Citation2018). It is typically employed for its ability to manage various forms of constructs, thus, both reflective measurement and composite models, it is broadly regarded as the ‘‘most fully developed and general system’’ (McDonald Citation1996, 240) among variance-based estimators for structural equation modelling.

Missing data are managed with multiple regression imputation and the measurement models are reflectively measured (Groenland and Stalpers Citation2012). Significantly, a bootstrapping algorithm was used to estimate the model parameters and standard errors with 5000 resamples in 5 iterations (Gefen and Straub Citation2005; Christian, Roldan, and Gabriel Citation2016).

The measurement model is assessed for fitness to the data and constructs internal consistency and reliability, for which composite reliability is recommended in dealing with reflective measurements (Hair et al. Citation2014). Suggested at 0.80 for a reflective construct, the values obtained for composite reliability indicate a high level of internal consistency and reliability for all the constructs in , thus; INFO is 0.842, KNW is 0.832 and INNO is 0.830, respectively. For convergent validity between latent variables and their observable indicators, the high outer loadings obtained are consistent with the recommended threshold of 0.50 or higher (Urbach and Ahlemann Citation2010). For discriminant validity, the square roots of their Average Variance Extracted (AVE) in are greater than their highest correlation coefficients with other latent variables (Chin Citation1988) and VIF reported are less than 3.3 showing no multicollinearity (Kock and Lynn Citation2012). Finally, for unidimentionality the manifest variables loaded rightly (more than 0.60) only on their respective constructs (Gefen and Straub Citation2005). In the Table, the correlation among the variables is high enough to guarantee the use of the chosen technique for reliable results.

Table 2. Combined loadings of the measurement model.

Table 3. Correlations among latent variables and square root of AVEs.

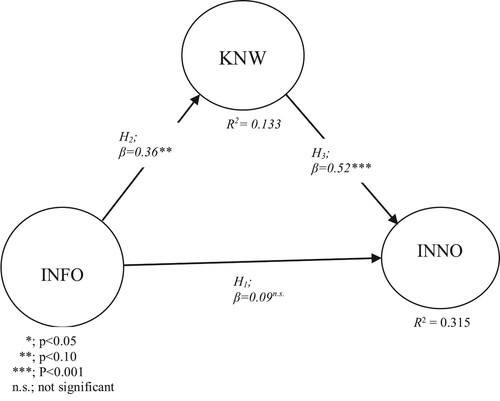

In , the path coefficients (β) evaluate and explain the relationship between the latent variables in the model and here H1 is too weak (0.09) meaning statistically, there is no relation between informal mechanisms of university knowledge transfer and innovation performance in firms as shown in . Hypotheses H2 and H3 show a strong relationship of 0.36 and 0.52 respectively in their response variables due to unit changes in their predictor variable as a result of unit changes in their response variables. The coefficient of determination (R2) reveals a very low explanatory tendency of 0.024 for HI as well, low of 0.131 for H2 and average of 0.286 for H3. The effect sizes (f2) are fine for all models although theoretically low (0.052) for H1. Lastly, Q2 for the predictive relevance of the observable indicator variables are above zero as required (Q2 > 0.00) indicating their weight and influence in the models (Fornell and Cha Citation1994).

Table 4. Structural model validation.

presents the model results and shows a statistically non-significant relationship (H1:β = 0.087, p > 0.05) between INFO and INNO but a statistically significant and positive relationship (H2:β = 0.362, p < 0.05) between INFO and KNW and again between KNW and INNO (H3:β = 0.520, p < 0.05). Notably, the significant and positive indirect effect of 0.188 (p < 0.001) for KNW as a mediator is found to perform a full mediating role between INFO on INNO. The total effect (β = 0.275, p < 0.006) is not only equally significant and positive but also reasonably strong. gives a structural and statistical representation of the relationships.

Table 5. Path coefficients for latent variables.

Discussion

The study was built on the premise that informal mechanisms of university knowledge transfer and knowledge networks have a positive influence on innovation performance in firms (Nielsen Citation2020; Silva and Cirani Citation2020). With this focus, the study adopted a structural model with partial least squares as an analytical technique. However, from the results, it is noted that informal mechanisms of university knowledge transfer do not directly influence innovation in Ghanaian firms as proposed. Implicitly, when firms develop relationships with universities in Ghana through informal mechanisms; knowledge is typically not transferred directly to facilitate changes in business practices and products. Conversely, we find in previous studies that proximity to universities fosters social relations and familiarity with researchers, in turn, supports business processes and services improvements with new knowledge (Brown-Luthango Citation2012; Ponds, Oort, and Frenken Citation2010). The findings infer that efforts to make use of published research from universities and other freely disseminated new knowledge do not enhance innovation performance directly in Ghanaian firms. It will also be logical to suggest that innovative activities in firms in Ghana may be influenced by knowledge generated from other mechanisms. It could be generated from other sources such as industry-based research or technology transfer offices. Consequently, links that establish direct contracts with universities, with more procedural aspects, but not through informal interactions, positively impact firm level innovation performance.

Overall, our findings have not corroborated with extant literature on the effects of social interactions, the benefits of social capital and informal knowledge channels on organisational progress, wealth creation and economic growth (Huggins and Johnson Citation2012; Thomas and Murphy Citation2019). Yet, in reference to researchers, such as de Wit, Dankbaar, and Vissert (Citation2007), we know that sometimes external sources, including openly disseminated knowledge are not particularly reliable for firms to source innovative ideas from. Indeed, Howells, Ramlogan, and Cheng (Citation2012) contend that both formal and informal mechanisms of university knowledge transfer produce positive innovative results.

In other research, Abreu et al. (Citation2008) and Meyer-Krahmer and Schmoch (Citation1998) have observed the positive effects of firms’ informal interactions with universities directly on firms’ core competence, and sometimes indirectly as a viable platform for further collaborations and partnerships to evolve in the long run. The position of this research is that, given the literature is in the context of advanced economies, our findings in this study are a contribution to knowledge in the context of Ghana. This contribution is primarily founded on the principles of relational theory, the theory of social capital and network literature (Hitt, Lee, and Yucel Citation2002; Edelman et al. Citation2004), where it is apparent that a firm’s relationships may have both positive and negative consequences. To elaborate further, mistrust in a social system and even in administrative and political structures of a society, if not managed well, particularly by leaders and people in responsible positions and positions of trust, can erode the positive effects of social capital. Possibly, this finding is an outcome of a system in Ghana that has lost faith in institutions that are supposed to create and sustain social norms, beliefs and rules that should be collectively self-reinforcing. The loss of trust in institutions is likely to have been initiated and sustained by corrupt practices. In turn, corruption states Forson et al. (Citation2015) acts as an inhibitor to development in Ghana. Due to contracts not being strictly enforced by formal institutions, trust is considered an important economic exchange lubricant in West African economies (Kuépiéa, Tenikuea, and Walther Citation2016). The findings of (Kuépiéa, Tenikuea, and Walther Citation2016) may suggest that an impact of a loss of trust may be magnified given a lack of formal contracts, especially among the poorer members of society. As a result, instead of social capital facilitating access to valuable and innovative knowledge, informal relationships in Ghana appear not to support to increased levels of innovative activity. This is evident in a lower factor loading of 0.646 in for the construct dealing with trust among actors in the university knowledge generation and transfer system and could be said to manifest a similar scenario in the Asian economies noted in the literature (for example, Adler and Kwon Citation2000). One other set-back noticed, could be what Hitt, Lee, and Yucel (Citation2002, 357) called ‘ … conscientious exploitation of eminent relationship with political, regulatory, and government posts’, where only firms and business executives that have links with certain power sources have the benefit of social capital to the neglect of others. In support, Asomah (Citation2021) warns of the negative impact corruption can have on Ghana’s development.

The findings further reveal that knowledge networks have been empirically found to have a form of mediating influence between informal mechanisms of university knowledge transfer and innovation performance in firms (Nielsen Citation2020; Cheng Citation2020). Thus, our second (H2) and third (H3) hypotheses suggest direct relationships between knowledge networks and both informal mechanisms of university knowledge transfer and innovation performance in Ghana are supported. Meanwhile, despite informal mechanisms not appearing to influence innovation performance directly, according to the results, there is evidence of its influence on knowledge networks resulting in a cumulative effect of the two, leading up to a 27% increase in innovation performance in firms in Ghana. In this case, it can be interpreted that as stated in the literature (Hagedoorn et al. Citation2000), business owners’ informal links and social interactions with universities in Ghana eventually strengthen weak ties. Consequently, the result creates more trust and long-term productive knowledge networks that support the transfer of university knowledge to firms for innovation and wealth creation. This is how the outcome of social capital really impacts on firms’ competence and yields commercial benefits (Adler and Kwon Citation2000). Undeniably, knowledge networks create informal interactions and social capital which may lead to increased levels of innovative activity. Therefore, the findings indicate that firms which are active in connecting with knowledge sources in networks, clusters and innovation systems stand to gain knowledge and subsequently increase levels of innovative activity.

Conclusion

The results of the research reveal that Ghanaian firms are supported in increasing levels of innovative activity by university knowledge transfer, part of which is via knowledge networks, but not directly from informal mechanisms per se. The implication here is that firms in Ghana gain little from their casual/social relationships with universities as knowledge sources. At the firm level, university knowledge via formal contacts, which are mainly based on procedural machinery are generally more productive. However, open access information or knowledge may not help firms become more competitive in Ghana as absorptive capacities are generally low. This is exacerbated by comparatively poorly resourced research teams found in most universities (Kamien and Zang Citation2000; Ponds, Oort, and Frenken Citation2010). Also, few well-resourced researchers and their university departments may not be ready to share relevant knowledge. A possible reason for this is a need to keep control of their intellectual property to claim royalties. University scientists may need to be engaged by firms on more official terms to be committed to generating knowledge for firms.

Corruption typically negatively impacts on Ghana’s development (Forson et al. Citation2015; Asomah Citation2021). Consequently, it may be the case that if there is a lack of trust in informal knowledge exchange in Ghana, this may in part be due to the country’s level of corruption (Transparency International Citation2021). This has important implications for other developing countries, which may also have comparatively high levels of corruption. Such corruption may limit the efficacy of informal knowledge exchange in countries like Ghana and negatively impact on Ghana’s development. The implications for Ghanaian development are to create bespoke anti-corruption policies and bespoke intellectual property rights. Crucially, both sets of policy should be empathetic to Ghana’s stage of development.

As evident in the data analysis, knowledge networks by no means constitute effective means to increase levels of innovation in firms. They remain as strong contenders for predictive knowledge generation and provide ease of access to new knowledge in Ghana. As a result, their formation and subsequent activities need to be supported by policy makers at local, national, and international levels. The government of Ghana can encourage the development of social capital and support its effect on firms’ level innovation in Ghana. Again, governments of less technologically advanced nations, including Ghana, can facilitate R&D either directly or indirectly by adopting a modified form of the Bayh-Dole Act (1980) to encourage firms’ formal links with universities, support knowledge networks and community spirit that can lead to firms benefiting from informal means in university knowledge transfer. The Ghanaian government can offer more support for university research or offer total sponsorships as practised in other economies to stimulate innovation and support wealth creation and economic growth. Finally, to foster economic growth, the institution and implementation of effective licencing and patent systems could encourage both firms and universities in Ghana to engage in effective collaborations and knowledge transfer.

The study is not without limitations and the main one has been the data collection process, which did not cover all the Ghanaian regional administrative capitals to capture data on the use of informal mechanisms of university knowledge transfer. We, therefore, admit a potential response bias during the data collection process. It is recommended to undertake a further study that will cover all the regions in Ghana, increasing the level of generalization of the findings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abdulai, A.-F., L. Murphy, and B. Thomas. 2015. “The Influence of Industry-University Interaction on Industrial Innovation in Ghana: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach.” International Journal of Arts and Science 8 (4): 229–244.

- Abreu, M., V. Grinevich, A. Hughes, M. Kitson, and P. Ternouth. 2008. Universities, Business and Knowledge Exchange, Council for Industry and Higher Education, and Centre for Business Research.

- Adams, S. 2008. “Globalization and Income Inequality: Implications for Intellectual Property Rights.” Journal of Policy Modelling 30: 725–735.

- Adjargo, G. 2012. “Social Capital: An Indispensable Resource in Ghana.” Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa 14 (3): 219–227.

- Adler, P., and S.-W. Kwon. 2000. “Social Capital: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.” In Knowledge and Social Capital: Fundamentals and Applications, edited by E. L. Lesser, 287–115. Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Asomah, J. Y. 2021. “What Can be Done to Address Corruption in Ghana? Understanding Citizens’ Perspectives.” Forum for Development Studies 48 (3): 519–537.

- Audi, R. 2011. Epistemology: A Contemporary Introduction to the Theory of Knowledge. 3rd ed. New York: Rouledge.

- Autio, E., A.-P. Hameri, and O. Vuola. 2004. “A Framework of Industrial Knowledge Spill Overs in the Big-Science Centres.” Research Policy 33: 107–126.

- Bailey, T., N. Cloete, and P. Pillay. 2011. “Universities and Economic Development in Africa, Case Study: Ghana and University of Ghana.” HERANA, CHET.

- Barnes, T., I. Pashby, and A. Gibbons. 2002. “Effective University–Industry Interaction: A Multi-Case Evaluation of Collaborative R&D Projects.” European Management Journal 20 (3): 272–285.

- Bonye, S. Z., A. Thaddeus, and A. E. Owusu-Sekyere. 2013. “Community Development in Ghana: Theory and Practice.” European Scientific Journal 9 (17): 79–101.

- Bradley, S. R., C. S. Hayter, and A. N. Link. 2013. “Models and Methods of University Technology Transfer.” Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship 9 (6): 571–650.

- Brown-Luthango, M. 2012. “Community-University Engagement: The Philippi CityLab in Cape Town and the Challenge of Collaboration Across Boundaries.” Higher Education 65 (3): 309–324.

- Cadger, K., K. Andrews, A. K. Quaicoo, E. Dawoe, and M. E. Isaac. 2016. “Development Interventions and Agriculture Adaptation: A Social Network Analysis of Farmer Knowledge Transfer in Ghana.” Agriculture 6 (32): 1–14.

- Caniels, M. C., and H. Van den Bosh. 2011. “The Role of Higher Education Institutions in Building Regional Innovation Systems.” Papers in Regional Science 90 (2), 271–286.

- Cheng, E. C. K. 2020. “Knowledge Transfer Strategies and Practices for Higher Education Institutions.” VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems,’ 51(2): 288–301. In Print, doi:10.1108/VJIKMS-11-2019-0184.

- Chesborough, H. 2003. Open Innovation: The new Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Chin, W. W. 1988. “Partial Least Square to Structural Equation Modelling.” In Modern Methods for Business Research, edited by G. A. Marcoulide, 1295–1336. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Christian, N. L., J. Roldan, and C. Gabriel. 2016. “Mediation Analysis in Partial Least Squares Path Modelling: Helping Researchers Discuss More Sophisticated Models.” Industrial Management & Data Systems 116 (9): 1849–1864.

- Clancy, M. S., and G. C. Moschini. 2013. “Incentives for Innovation: Patents, Prices, and Research Contracts.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 35 (2): 206–241.

- Cohen, J. 1992. “Quantitative Method in Psychology: A Power Premier.” Psychological Bulletin 112 (1): 115–159.

- Cohen, L., and L. Manion. 1985. Research Methods in Education, 2nd ed. London: Croom Helm.

- Cohn, S. 2013. “A Firm-Level Innovation Management Framework and Assessment Tools for Increasing Competitiveness.” Technology Innovation Management Review, 3: 6–15.

- Cooke, P., and L. Leydesdorff. 2006. “Regional Development in the Knowledge-Based Economy: The Construction of Advantage.” Journal of Technology Transfer 31: 5–15.

- De Beukelaer, C., and M. Fredriksson. 2019. “The Political Economy of Intellectual Property Rights: The Paradox of Article 27 Exemplified in Ghana.” Review of African Political Economy 46 (161): 459–479.

- de Wit, J., B. Dankbaar, and G. Vissert. 2007. “‘Open Innovation: The New Way of Knowledge Transfer?” ’ Journal of Business Chemistry 4 (1): 11–19.

- De Wit de Vries, Esther, Wilfred A. Dolfsma, Henny J. van der Windt, and M. P. Gerkema. 2019. “Knowledge Transfer in University–Industry Research Partnerships: A Review.” Journal of Technology Transfer 44: 1236–1255.

- Deiaco, E., A. Hughes, and M. McKelvey. 2012. “University as Strategic Actors in the Knowledge Economy.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 36 (3): 525–541.

- D’Este, P., and P. Patel. 2007. “University–Industry Linkages in the UK: What are the Factors Underlying the Variety of Interactions with Industry?” Research Policy 36 (9): 1295–1313.

- Dooley, L., and D. Kirk. 2007. “University-industry Collaboration: Grafting the Entrepreneurial Paradigm Onto Academic Structures.” European Journal of Innovation Management 10 (3): 1460–1060.

- Edelman, L. F., M. Bresnen, S. Newell, H. Scarbrough, and J. Swan. 2004. “The Benefits and Pitfalls of Social Capital: Empirical Evidence from Two Organisations in the United Kingdom.” British Journal of Management 15: 59–69.

- Edquist, C. 2001. “The Systems of Innovation Approach and Innovation Policy: An Account of the State of the Art.” The DRUID conference Aalborg, June 12–15: DRUID, Aalborg.

- Etzkowitz, H. 2002. “The Triple Helix of University-Industry-Government: Implication for Policy and Evaluation.” Working Paper, Social Science Policy institute ISSN 1650-3821.

- Etzkowitz, H., and L. Leydesdorff. 1997. Universities in the Global Knowledge Economy: A Triple Helix of University-Industry-Government Relations. London: Cassel.

- Etzkowitz, H., and L. Leydesdorff. 2000. “The Dynamics of Innovation: From National Systems and ‘Mode 2’ to a Triple Helix of University-Industry-Government Relations.” Research Policy 29 (2): 109–123.

- Etzkowitz, H., A. Webster, C. Gebhardt, and B. R. C. Terra. 2000. “The Future of the University and the University of the Future: Evolution of Ivory Tower to Entrepreneurial Paradigm.” Research Policy 29: 313–330.

- Fornell, C., and J. Cha. 1994. Partial Least Squares. Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Forson, J. A., P. Buracom, T. Y. Baah-Ennumh, G. Chen, and E. Carsmer. 2015. “Corruption, EU Aid Inflows and Economic Growth in Ghana: Cointegration and Causality Analysis.” Contemporary Economics 9 (3): 299–318.

- Freeman, C. 1995. “The National System of Innovation in Historical Perspective.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 19: 5–24.

- Fu, X., G. Zanello, G. Essegbey, J. Hou, and P. Mohnen. 2014. Innovation in Low Income Countries: A Survey Report, Growth Research Programme.

- Gefen, D., and D. Straub. 2005. “A Practical Guide to Factorial Validity Using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and Annotated Examples.” Communication of the AIS 16: 91–109.

- Geroski, P. A. 1994. Market Structure, Corporate Performance and Innovative Activity. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Geuna, A., and A. Muscio. 2009. “The Governance of University Knowledge Transfer: A Critical Review of the Literature.” Minerva. 47: 93–114.

- Ghana Population and Housing Census. 2021. General Report Volume 3D: Literacy and Education, Ghana Statistical Service. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service.

- Gibbons, M., C. Limoges, H. Newotny, S. Schwartzman, P. Scott, and M. Trow. 1994. The new Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. London: Sage.

- Gorard, S. 2003. Quantitative Method in Social Science: The Role of the Numbers Made Easy. UK: Continuum.

- Grimpe, C., and K. Hussinger. 2013. “Formal and Informal Knowledge and Technology Transfer from Academia to Industry: Complementarity Effects and Innovation Performance.” Industry & Innovation 20 (8): 683–700.

- Groenland, E., and J. Stalpers. 2012. “Structural Equation Modelling: A Verbal Approach.” Nyenrode Research Paper Series 12 (2): 1–39.

- Guimon, J. 2013. “Promoting University-Industry Collaboration in the Developing Countries.” The Innovation Policy Platform, Policy Brief.

- Hagedoorn, J., A. N. Link, and N. S. Vonortas. 2000. “Research Partnerships.” Research Policy 29 (4-5): 567–586.

- Hair, J. F., G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2014. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Hamilton, C., and S. P. Philbin. 2020. “Knowledge Based View of University Technology Transfer – A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis.” Administrative Sciences 10 (3): 62–89.

- Henseler, J. 2018. “Partial Least Squares Path Modelling: Quo Vadis?.” Quality and Quantity International Journal of Methodology.

- Hitt, M. A., H.-U. Lee, and E. Yucel. 2002. “The Importance of Social Capital in the Management of Multinational Enterprises: Relational Networks among Asian and Western Firms.” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 19: 353–372.

- Hobday, M. 2005. “Firm-level Innovation Models: Perspectives on Research in Developed and Developing Countries.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 17 (2): 121–146.

- Howells, J., R. Ramlogan, and S.-L. Cheng. 2012. “Innovation and University Collaboration: Paradox and Complexity Within the Knowledge Economy.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 36: 703–721.

- Huggins, R., and A. Johnson. 2012. “Knowledge Alliances and Innovation Performance: An Empirical Perspective on the Role of Network Resources.” International Journal of Technology Management 57 (4): 245–265.

- Huggins, R., A. Johnson, and R. Steffenson. 2008. “‘Universities, Knowledge Networks and Regional Policy.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 1 (2): 321–340.

- Hughes, A., and M. Kitson. 2012. “Pathways to Impact and the Strategic Role of Universities: New Evidence on the Breadth and Depth of University Knowledge Exchange in the UK and the Factors Constraining its Development.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 36 (3): 723–750.

- Janz, N., H. Lööf, and B. Peters. 2004. ‘Firm Level Innovation and Productivity-Is There a Common Story Across Countries?; Problems and Perspectives in Management.

- Kamien, M. I., and I. Zang. 2000. “Meet me Halfway: Research Joint Ventures and Absorptive Capacity.” International Journal of Industrial Organization 18: 995–1012.

- Kaymaz, K., and K. Y. Eryiğit. 2011. “Determining Factors Hindering University-Industry Collaboration: An Analysis from the Perspective of Academicians in the Context of Entrepreneurial Science Paradigm.” International Journal of Social Inquiry 4 (1): 185–213.

- Kock, N., and G. S. Lynn. 2012. “Lateral Collinearity and Misleading Results in Variance- Based SEM: An Illustration and Recommendations.” Journal of the Association for Information Systems 13 (7): 546–580.

- Kogut, B., and U. Zander. 1992. “Knowledge of the Firm and the Evolutionary Theory of the Multinational Corporations.” Journal of International Business Studies 4: 265–245.

- Kogut, B., and U. Zander. 1993. “Knowledge of the Firm, Combinative Capabilities, and the Replication of Technology.” Organisation Science 3 (3): 383–397.

- Krippendorff, K. 2004. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication Ltd.

- Kuépiéa, M., M. Tenikuea, and O. J. Walther. 2016. “Social Networks and Small Business Performance in West African Border Regions.” Oxford Development Studies 44 (2): 202–219.

- Lam, A. 1997. “Embedded Firms Embedded Knowledge: Problems of Collaboration and Knowledge Transfer in Global Cooperative Ventures.” Organisational Studies 18 (6): 973–996.

- Lam, A. 2000. “Tacit Knowledge Organisational Learning and Social Institutions: An Integrated Framework.” Organisational Studies 21 (3): 487–513.

- Léger, A., and S. Swaminathan. 2007. “Innovation Theories: Relevance and Implications for Developing Country Innovation.” Discussion Paper 743, DIW. Berlin.

- Lui, W.H. 2016. “Intellectual Property Rights, FDI, R&D and Economic Growth: A Cross-Country Empirical Analysis.” World Economy 39 (7): 983–1004.

- Lundvall, B,A. 1992. National Systems of Innovation: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning. London: Pinter Publishers.

- McDonald, R. P. 1996. “Path Analysis with Composite Variables.” Multivariate Behavioural Research 31 (2): 239–270.

- Mendoza-Silva, A. 2020. “Innovation Capability: A Systematic Literature Review.”

- Meyer-Krahmer, F., and U. Schmoch. 1998. “Science-based Technologies: University–Industry Interactions in Four Fields.” Research Policy 27: 835–851.

- Minister for Finance. 2015. The Budget Speech of the Budget Statement and Economic Policy of the Government of Ghana for the 2016 Financial Year. Accra: Ghana Government.

- Ministry of Environment, Science and Technology. 2010. National Science, Technology, and Innovation Policy. Ghana: Ghana Government.

- Mosey, S., M. Wright, and B. Clarysse. 2012. “Transforming Traditional University Structures for the Knowledge Economy Through Multidisciplinary Institutes.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 36 (3): 587–607.

- Mowery, D. C., and B. N. Sampat. 2005. “The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 and University-Industry Technology Transfer: A Model for Other OECD Governments?” Journal of Technology Transfer 30 (1/2): 115–127.

- Murphy, L. 2011. “An Analysis of Innovation Programmes in Wales Along a ‘Hard – Soft’ Policy Continuum – A Case Study Approach.” PhD thesis, University of Glamorgan, now University of South Wales.

- Murphy, L., R. Huggins, and P. Thompson. 2015. “Social Capital and Innovation: A Comparative Analysis of Regional Policies.” Government and Policy 0 (0): 1–33.

- Muscio, A., A. Quaglione, and G. Vallanti. 2013. “Does Government Funding Complement or Substitute Private Research Funding to Universities?” Research Policy 42 (1): 63–75.

- Nahapiet, J., and S. Ghoshal. 2000. “Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organisational Advantages.” In Knowledge and Social Capital: Fundamentals and Applications, edited by E. L. Lesser, 119–157. Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Nelson, R., and S. Winter. 1982. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Nielsen, C. 2020. “From Innovation Performance to Business Performance: Conceptualising a Framework and Research Agenda.” Meditari Accountancy Research 27 (1): 1–20.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 1997. National Innovation Systems. Paris: OECD-Publications, 2.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2013. Governance of Higher Education, Research and Innovation in Ghana, Kenya, and Uganda. SIDA.

- Pittaway, L., M. Robertson, K. Munir, D. Denyer, and A. Neely. 2004. “Networking and Innovation: A Systematic Review of the Evidence.” International Journal of Management Reviews 5/6 (3&4): 137–168.

- Podsakoff, P., M. NacKenzie, J.-Y. Lee, and N. Podsakoff. 2003. “Common Method Biases in Behavioural Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies.” Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (5): 879–903.

- Ponds, R., F. v. Oort, and K. Frenken. 2010. “Innovation, Spillovers and University-Industry Collaboration: An Extended Knowledge Production Function Approach.” Journal of Economic Geography 10 (2): 231–255.

- Punch, K. F. 2005. Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publication Ltd.

- Rosenberg, N. 1982. Inside the Black box: Technology and Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rossi, F., and A. Rosli. 2013. “Indicators of University-Industry Knowledge Transfer Performance and Their Implication for Universities: Evidence from the UK’s HE-BCI Survey.” CIMR Research Working Paper Series 13: 1–24.

- Sawyerr, A. 2004. “Challenges Facing African Universities: Selected Issues.” African Studies Review 47 (1): 1–59.

- Siegel, D. S., D. A. Waldman, L. E. Atwater, and A. N. Link. 2003. “Commercial Knowledge Transfers from Universities to Firms: Improving the Effectiveness of University-Industry Collaboration.” Journal of High Technology Management Research 14: 111–133.

- Silva, J. J., and C. B. S. Cirani. 2020. “The Capability of Organizational Innovation: Systematic Review of Literature and Research Proposals.” Gestão & Produção 27 (4): 1–16. doi:10.1590/0104-530X4819-20.

- Smith, E. A. 2001. “The Role of Tacit and Explicit Knowledge in the Workplace.” Journal of Knowledge Management 5 (4): 311–321.

- Su, C.-Y., B.-W. Lin, and C.-J. Chen. 2015. “Technological Knowledge co-Creation Strategies in the World of Open Innovation.” Innovation 17 (4): 485–507.

- Takeuchi, H. 2013. “‘Knowledge-Based View of Strategy.” Universia Business Review 40: 68–79.

- Tekic, Z., I. Kovacevic, P. Vrgovic, A. Orcik, and V. Todorovic. 2013. “iDEA Lab: Empowering University-Industry Collaboration Through Students’ Entrepreneurship and Open Innovation.” International conference on technology transfer, Navi sad Serbia.

- Thomas, B., D. Brooksbank, and R. J. H. Thompson. 2009. “A Study of Optimising the Regional Infrastructure for Higher Education Global Start-ups in Wales.” International Journal of Globalisation and Small Business 3 (2): 220–237.

- Thomas, B. C., and L. J. Murphy. 2019. Innovation and Social Capital in Organizational Ecosystems. Hershey: IGI Global.

- Transparency International. 2021. “Corruption Perceptions Index” Accessed 22 May 2022. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021

- Tunnainen, J. 2002. “Reconsidering Mode 2 and Triple Helix: A Critical Comment Based on a Case Study.” Science Studies 15 (2): 36–58.

- Urbach, N., and F. Ahlemann. 2010. “‘Structural Equation Modelling in Information Systems Research Using Partial Least Squares.” Journal of Information Technology, Theory and Practice 11 (2/2): 5–40.

- Van Horne, C., D. Poulin, and J.-M. Frayret. 2010. “Measuring Value in the Innovation.”

- Victoria, G.-M., S. Peter, G. Peter, and B. Thomas. 2015. “‘Nurture Over Nature: How do European Universities Support Their Collaboration with Business?” Journal of Technology Transfer 42: 184–205.