?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Membership in Agricultural Marketing Co-operative Societies (AMCOS) benefits farmers through strengthened bargaining power in marketing and better access to other support services including access to agricultural inputs. Despite the benefits of AMCOS, many farmers have not joined AMCOS. Some farmers are reluctant to join AMCOS while others are dropping out. This study, therefore, specifically examined socio-economic and institutional determinants of farmers’ decision to join AMCOS in Mvomero and Kilombero districts. This study adopted a cross-sectional design whereby 340 farmer respondents were interviewed. Data were analyzed through descriptive statistics, comparative, and binary regression analysis. The findings showed that age, education, credit services, the amount of credit accessed, farm input, marketing, and price information were significant determinants of farmers’ decision to join AMCOS. The study recommends that AMCOS management should improve the services they offer and reduce the cost of membership to attract more farmers to access their services. Also, the District Co-operatives Officers and AMCOS managers should carry out public awareness campaigns and educate the farmers on the importance of co-operatives as the findings showed that some farmers were not informed about co-operative societies.

1. Introduction

Agricultural production in Sub-Saharan Africa has been facing many challenges, the major one being under-performing. Furthermore, the trend is worsening as there has been a recorded declining agricultural production. Consequently, food security has become perpetual problem and farming food for subsistence purposes has been adopted as an alternative practice in many Africa countries. This problem is associated with high transaction cost, inadequate information concerning market opportunities, lack of credit facilities, and other market imperfections (Bjornlund, Bjornlund, and Van Rooyen Citation2020; Okello et al. Citation2012). Also, the farmers have been facing the problem of applying old traditional methods of farming which result in low yields; hence, leading to low income for the farmers after selling their produce (Munyaneza et al. Citation2019). This limits farmers’ chances of increasing their scale of production in order to lower transaction costs and invest in efficient and value addition technologies. Farmers also have inadequate technical skills, limited training on production, processing, and marketing. Lastly, farmers lack bargaining powers which result in unfair distribution of the value added among the actors in the market chain (Nkurunziza Citation2014).

Smallholder farmers can deal with the above problem by cooperating each other through agricultural cooperative societies which will strengthen them through collective action rather than acting individually. By doing so, farmers can overcome poverty and increase their bargaining power in the market place (Gashaw and Kibret Citation2018). A co-operative society is an autonomous union of people who are united by their own free will to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a collectively owned and democratically controlled organization (ICA Citation2005). Agricultural co-operatives fall into conventional activities of agricultural practices that involve supply of farm inputs, collective production, and transportation and marketing of agricultural produce. The focus in this study, however, is on the co-operative societies which deal with marketing of agricultural produce. These co-operatives are commonly known as Agricultural Marketing Co-operative Societies (AMCOS) (Nugusse and Buysse Citation2013; Seimu Citation2015; Maghimbi Citation2010).

Co-operatives have been proposed as an efficient tool for increasing market access and improving members’ wellbeing (Maghimbi Citation2010). For example, the government of South Africa has underscored the role of co-operatives in enhancing economic and social development of a country through creation of employment opportunities, generating income, empowering small-scale farmers, and reducing poverty (RSA Citation2005). Generally, it is believed that production and productivity can be improved through the expansion of co-operatives as a basis for development (Gebremichael Citation2014).

Like in other African countries, co-operatives were introduced in Tanzania during the colonial era as an instrument of achieving the socio-economic goals of the colonial government. Peasant farmers in the then Tanganyika formed the first co-operatives around 1925 that aimed at enabling native farmers to benefit from commercial farming of cash crops such as coffee, sisal, tobacco, and cotton (Seimu Citation2015). The co-operatives continued to expand, for example, by 1966, there were 1616 registered formal co-operatives out of which 1339 dealt with the marketing of agricultural produce. Currently, there are about 10,990 registered co-operatives of which 3413 are AMCOS (Maghimbi Citation2010; TCDC Citation2017). Due to frequent complaints regarding mismanagement and corruption in the co-operatives, the Tanzania government issued a decree abolishing the AMCOS in May 1976. However, these societies were reintroduced in 1982 and were followed by the enactment of the Co-operatives Law in 1991. They performed poorly as a result of the implementation of the Co-operatives Law which was too restrictive (Maghimbi Citation1992). Another challenge faced by the agricultural co-operative’s movement was the introduction of crop boards which took over the marketing role of the co-operatives; hence, leading to the overlapping and conflicting responsibilities between co-operatives and crop boards (ADF Citation2002). In addressing this problem, the Government of Tanzania introduced a new Co-operatives Policy of 2002 to enable the co-operatives recover their role in promoting economic gains of the people (TFC Citation2006).

Farmers who choose to be members of agricultural co-operative societies enjoy several advantages such as low transaction costs, adequate farm inputs, and access to credit facilities and marketing services. However, despite the advantages of membership in co-operative societies, some of the smallholder farmers are unwilling to join co-operatives while some of the existing members want to withdraw their membership from these societies (Kigathi Citation2016). Nevertheless, the factors influencing farmers’ decision to join co-operatives have not been well defined in the past and this has, to a great extent, affected co-operatives movements in Tanzania (Kigathi Citation2016; Nkuhi and Mbuya Citation2017).

According to the United States Overseas Co-operatives Development Council (2007), the resurgence of agricultural co-operatives in developing countries is associated with many changes including the abandonment of planned economies, globalization of production, and democratization. The findings of a study done by Asante and Afari-Sefa (Citation2011) on the determinants of farmers’ decision to join farmers’ organizations in Ghana showed that the size of the farm, kind of agriculture practiced, credit access and availability of agro-mechanization services influenced smallholder farmers’ decision to join farmers’ cooperative organizations in Ghana. A study by Kayitesi (Citation2019) which was conducted in Rwanda showed that farmers’ membership to cooperative societies was influenced by prospects of access to credit and the farmers’ engagement with off-farm income. Additionally, the study findings revealed that those framers with large agricultural land size were more likely to be members of agricultural cooperative societies. The study concludes that education, size of farm, and total income were important determinants of farmers’ membership choices in co-operatives. The findings of a study by Frayne, Theron, and Gary (Citation1998) revealed also that smallholder farmers were more likely to become members of agricultural co-operative societies compared to those who were large-scale farmers. Another study by Okwoche, Osogura, and Ckukwudi (Citation2012) showed that farmers joined agricultural co-operative societies mostly in order to access credit facilities and other services. Similar results are reported in a study by Nkurunziza (Citation2014) whose findings showed that socio-economic and institutional reasons were the driving force for farmers’ decision to join co-operatives.

Conversely, a study by Balgah (Citation2019) that was done in Cameroon found that age, education attained by a farmer, access to credit and sex of the farmer negatively influenced farmers’ decisions on their membership in agricultural co-operatives. The study further showed that income of the farmers had no influence on farmers’ membership in cooperative societies. Another study that was conducted in China by Zheng, Wang, and Awokuse (Citation2012) found that the factors which determined the farmers’ membership in agricultural co-operatives included perceived uncertainty of prices for their produce and production, future extension of farm land, the type of cash crops grown, and the practice of subsistence farming. The study showed further that there was a higher probability for cash crop farmers to join co-operatives than was the case with grains producers.

According to Njiru et al. (Citation2015), smallholder farmers’ likelihood to join co-operatives revolved around social influence. Another study by Ollila, Nilsson, and Bromssen (Citation2011) revealed that the motivation for smallholder farmers’ decision to join co-operatives was mainly influenced by ideological and economic reasons. Lastly, a study done by Karl, Bilgi, and Elik (Citation2006) showed that the likelihood of farmers to join agricultural co-operatives decreased with the increase in the size of the farms. Conflicting findings by researchers over the factors influencing farmers’ decision to join agricultural co-operatives necessitated a similar study in the context of Tanzania. However, there are few studies in Africa, and specifically in Tanzania, on the determinants that compel the smallholder farmers to join agricultural co-operatives. Therefore, the current study fills this knowledge gap by focusing on exploring the socio-economic and institutional determinants of farmers’ membership in AMCOS in the Tanzania and specifically in Mvomero and Kilombero districts.

2. Literature review

2.1. Empirical review

There are different categories of farmers’ organizations which include farmers’ groups, farmers’ associations, AMCOS which are formed, controlled and owned by farmers, and non-governmental organizations (NGOS) dealing with agricultural development activities (Pinto Citation2009). Agricultural co-operatives in Tanzania are commonly known as AMCOS and are made up of four tier (level) co-operatives systems, namely primary, secondary, unions and federations. Primary societies are those that are at the lowest level and operate at the village level whereas secondary co-operatives are at the district level. Co-operative unions are at the regional level and the federation at the national level. However, in practice, co-operatives in Tanzania are operating with two tiers (levels) which are the primary societies at the village level and the unions at the regional level. Primary societies are organized regionally under the umbrella of co-operative unions (URT, Citation2013).

This study focused on the primary AMCOS in Tanzania. International organizations such as the International Labour Organization and FAO and the government of Tanzania have been urging farmers to be organized in order to access services through either internal or external support sources (Maghimbi Citation2010; FAO, Citation2015; Schwettmann, Citation2014). Also, the National Agriculture Policy of 2013 and Agricultural Sector Development Program phase II (ASDP II) have emphasized smallholder farmers to join AMCOS as important vehicles for them to access agricultural services support (URT, Citation2013; URT, Citation2017). A study conducted in the region by Msangya and Yihuan (Citation2016) showed that the major challenges facing small-scale farmers were unfavorable markets, inadequacy of agricultural inputs, inadequate extension services, lack of credit facilities as well as lack of improved crop varieties. These challenges are supposed to be solved through AMCOS. In addition to that, majority of the farmers are selling their crop production at the farm gate instead of doing so through AMCOS and at better prices (EPINAV, Citation2012).

2.2. Theoretical framework

This study was guided by Collective Action Theory by Olson (Citation1965). According to this theory, an institution refers to a public entity with a system of rules that provide assurance and respect for the actions of others by making possible greater cooperation and coordinated actions. It is imperative to note that farmers usually struggle to increase the price of their farm produce and access farm inputs (Gillinson, Citation2004). Therefore, any organization that focuses on the farmers’ needs will be serving the needs of an individual and that of the group. The shortcoming of the Collective Action Theory is that some members of the group use/consume more than their share or pay, and contribute less than the required contribution agreed by the collective group, which does not reflect the concept of the collective aspect among members (Lewis, Citation2006). Being in AMCOS, farmers who are members will benefit from the organization’s economies of scale such as lower transaction costs, access to extension service and price negotiation for their crops produce. Hence, a group of individuals will best work for their interests as a group rather than working for personal interests (Yau Citation2011). The theory was applicable in this study since it reflects how AMCOS can work on behalf of its members through collective actions; thereby, enabling members to reap a number of benefits.

2.3. Conceptual framework of the study

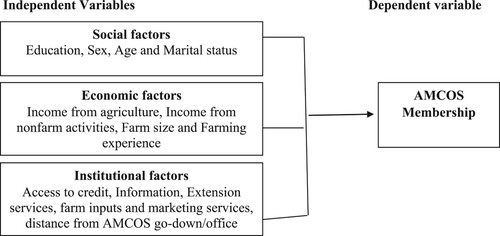

The farmers’ membership to AMCOS is determined by some interrelated factors within the decision-making domain of the smallholder farmers such as inadequate credit, inadequate access to information, inadequate farm for cultivation, the challenges faced in the supply of farm inputs, and inefficient transportation. These are the key determinants of the farmers’ membership in a collective organization. However, some factors differ among the farmers in different socio-economic settings. Empirically, socio-economic situations of smallholder farmers are the major determinants which influence their membership in co-operatives. The variables under socio-economic conditions include farmers’ age, level education, household size, and farm size. Other determinants include the wealth status of farmers and institutional factors as indicated in .

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study area

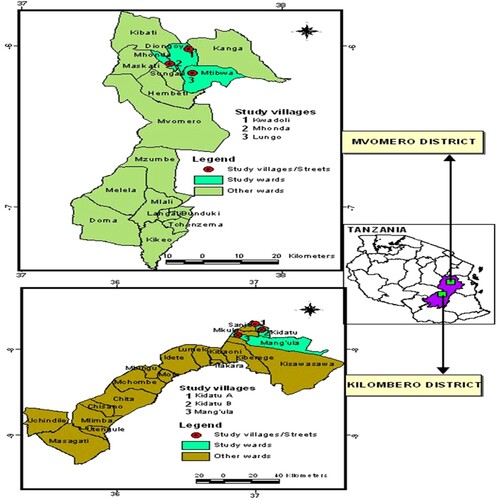

This study was conducted in Mvomero and Kilombero districts in Tanzania (). The population of districts were 312,109 and 407,880 in Mvomero and Kilombero, respectively. Kilombero and Mvomero districts in the Morogoro region whose main crops and source of livelihoods are paddy, maize and sugarcane. The rationale for selecting these study areas was based on three key reasons. Firstly, the two districts had more active AMCOS compared to other districts in Morogoro region. Secondly, AMCOS in these two districts had been in operation for more than seven years and, therefore, had a long experience; hence, the researcher expected to access rich data concerning AMCOS. Thirdly, the selected study areas had AMCOS dealing with sugarcane and cocoa cash crops. Given the fact that these were not part of the crops previously covered by AMCOS, they, therefore, presented a new and perhaps, unique context for research on this topic in order to come up with new insights.

3.2. Research design

This study employed a cross-sectional research design. The design was adopted as it allows the use of both qualitative and quantitative data. According to Creswell (Citation2013), this research design allows comparison of more than one group based on their attitudes, opinions, beliefs and practices. In the context of this study, the design facilitated the researcher’s comparison of two groups, members and non-members of AMCOS. The unit of analysis was individual members and non-members of AMCOS in Kilombero and Mvomero districts.

3.3. Sampling approach

The study adopted multi-stage sampling technique to select the study area, the 17 AMCOS and 340 respondents of which 151 were members of AMCOS while 189 were non-members. To collect qualitative data, four focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted, two from each district for members and non-members of AMCOS and six key informants were interviewed, two managers of co-operative societies from each district and one co-operative officer from each district.

3.4. Data collection methods

The study used the questionnaire survey method, FGDs and in-depth interview with key informants to collect data. The questionnaire was used to collect quantitative data. Checklists were used to collect qualitative information during FGDs and for in-depth interviews with key informants. Qualitative data collected included the opinions of leaders on why farmers joined AMCOS while others did not. Data from FGDs and in-depth interviews were recorded using a voice recorder.

3.5. Data analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, compare means, and binary logistics regression model. Descriptive statistics were used to make cross tabulations, frequency tables, charts and to compute averages and percentages. Compare means was computed to compare socio-economic characteristics between members and non-members of AMCOS. Binary logistic regression in Equation (1) was used to analyze the socio-economic and institutional determinants of farmers’ decisions to join AMCOS.

A binary logistic regression model showed the relationship between the dependent and the independent variables as:

(1)

(1) The probability of occurrence of the dependent outcome (decision to join AMCOS) was predicted using the following equation, which is derived from Equation (1). An antilog of both sides of the equation gives:

(2)

(2) Taking the natural log of the equation gives the following logit model in Equation (3)

(3)

(3) where, Y is the dependent variable, the subscript i refers to the ith observation in the sample, P is the likelihood that a smallholder farmer joins AMCOS and (1–P) is the likelihood that a smallholder farmer does not join AMCOS. β0 is the interception term and β1, β,2 … , β14 are the coefficients of the predictor variables X1, X2, … , X14 (age, size of farm, education, household size, extension contacts, non-farm income, access to credit and farm size). The analysis was done using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software. Qualitative data were transcribed through F4 transcription software and then coded, categorized, and grouped according to the themes and the data were analyzed using content analysis.

3.6. Research ethics

The research ethics were adhered at all stages of this study. They included obtaining a permit from the relevant government authority to conduct research, maintaining confidentiality and privacy of the respondents from whom data was collected and seeking informed consent of respondents during data collection.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents in the study area for both members and non-members of AMCOS. These characteristics included sex, age, marital status, and education levels of the respondents. Out of the 340 respondents, 210 (62.0%) were males and 130 (38.0%) females. In terms of their marital status, majority of the both the members and non-members were married. The age of members and non-members was statistically significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) with members being generally older than non-members. The average age of the members of AMCOS and non-members were 50 and 42 years respectively. This implies that, as the age of farmers increased, the likelihood of joining AMCOS also increased correspondingly. Education was the last socio-demographic information captured in this study. shows that 265 (78.0%) out of the 340 respondents attained primary school education while the rest had either not attended any formal school or had attained secondary school education, vocational training, or tertiary education. There was no statistically significant difference between members and non-members as they all attained almost the same level of education. The findings were in contrast with those in a study by Msimango and Oladele (Citation2013) done in Ngaka Modiri Molema district in South Africa which showed that most of the participants in the agricultural co-operatives had received formal education while the non-members had not.

Table 1. Respondents’ socio-demographic information (n = 340).

4.2. Respondents’ farming characteristics

As this study dealt with farmers, therefore, it was important to study the farming characteristics of the respondents. shows the farming characteristics of members and non-members in the study areas. These were farming experience in years, the size of the farms, the size of the farms under cultivation, and the rented farm.

Table 2. Respondents farm characteristics (n = 340).

4.2.1. Farming experience

The differences in farming experience between members and non-members were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) since the average farming experience for members and non-members was 27 and 18 years respectively. Therefore, on average, members of AMCOS were more experienced in farming than the non-members. This correlates with the demographic information in which revealed that co-operative societies’ members consisted mostly those who were middle-aged, implying that they had accumulated a significant experience in farming. According to Ajah (Citation2015), middle-aged people are at their productive ages in life and have the likelihood to embrace innovations faster. This is true because age, as a proxy for experience, can enhance business initiatives and efficient use of scarce resources.

4.2.2. The land owned, cultivated, and rented

Land ownership was one of the farming characteristics studied. The findings showed that the differences in terms of land ownership between the AMCOS members and non-members were highly significant (p ≤ 0.05). The average size of land owned by members and non-members was 9 and 5 hectares respectively, meaning that members of AMCOS owned more land than did the non-members. This is contrary to findings by Ajah’s (Citation2015) study which showed that farmers who were non-members of co-operatives had greater land access to land compared to the members. Consequently, the study proposed further research to be conducted in different contexts to determine whether the converse would be the case owing to the support services they got from co-operative societies.

The study also aimed at determining the size of land which was cultivated by members and non-members of AMCOS. The difference in terms of the sizes of land was statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) and the average land under cultivation for members and non-members was 6 and 3 hectares, respectively. The findings imply that AMCOS members cultivated more land than that of the non-members. The finding is similar to that of a study by Hoken and Su (Citation2015) in China which showed similar results.

Only 7.0% of the members of AMCOS rented land for cultivation while 28.0% of non-members rented land for cultivation. The averages of land rented were 3 hectares for members and 4 hectares for non-members of the co-operatives. The difference was not statistically significant. Based on the frequencies, it was apparent that non-members of AMCOS rented more land than their counterparts in AMCOS which is an indicator of inadequate land for non-members.

4.2.3. Distance from home to AMCOS office and go-downs

The distance from home to AMCOS office/godown was explored to determine whether it influenced farmers’ decision to join or not an AMCOS. About 74.0% and 26.0% of members reported that the distance from their homes to AMCOS office/godown was 1 and 2 km, respectively, while about 79.0% and 21.0% of non-members of AMCOS reported that it was 1 and 2 km. The average distance from household’s homes to the office was 1 km. The difference in distance from AMCOS office/godown to the households was not statistically significant. This is contrary to the findings of a study by Tesha (Citation2010) that was conducted in Mtwara, Tanzania, which revealed a statistically significant difference in terms of the distance from the homes of members and non-members to the AMCOS, which means that in some cases, long distances may limit farmers from joining AMCOS as they can use alternative markets and private shops for services related to agricultural activities.

4.3. Perceived factors influencing farmers’ participation in AMCOS

This study examined the factors that influenced farmers’ decision to join co-operatives. Majority (85.0%) of the members considered marketing arrangements and better prices as their reasons for joining AMCOS. The findings in indicated that 62.1% agreed and about 22.9% strongly agreed that marketing arrangements and better prices for their products were the factors that influenced them to join AMCOS. During FGDs, the farmers in both districts reported that they joined AMCOS in order to make harvesting and transportation of sugarcane to Mtibwa and Kilombero sugar factories easy. For cocoa growers in Mhonda ward (Mvomero district), the AMCOS facilitated marketing of the cocoa produce on behalf of their members. Farm inputs facilitation was ranked the second key factor for farmers’ decision to join AMCOS, whereby 52.1% agreed and 30.3% strongly agreed that farm inputs facilitation influenced their decision. Access to credit was ranked the third key factor that influenced their decision to join AMCOS as about 69.7% and 10.0% of the respondents agreed and strongly agreed respectively that the variable influenced their decision.

Table 3. Perceived factors influencing farmers to join AMCOS (n = 189).

Lastly, farmers indicated that fear of being cheated by buyers who were non-members of co-operatives influenced them to join AMCOS. About 50.0% of the respondents reported that having feared being cheated by non-co-operative buyers as a factor which influenced them to join AMCOS. Extension services and relationships were ranked low as factors influencing farmers’ decision to join AMCOS. More than half of the respondents strongly disagreed, while the rest disagreed that these factors influenced their decision of joining AMCOS.

In the study area, extension services were offered by agricultural extension officers who were employed by the local government authorities. Extension services were accessible by all farmers regardless of the status of their membership in AMCOS. Also, during FGDs, farmers reported to have belonged to other farmers’ associations and producers’ groups; therefore, they had established a strong relationship amongst themselves.

The findings of this study correspond with those in other studies conducted elsewhere by Nugusse (Citation2010) and Chibanda, Ortmann, and Lyne (Citation2009) in Ethiopia and South Africa respectively. These studies showed that farmers’ decisions to join agricultural co-operative societies were influenced by: (i) services provided (credit and farm inputs); (ii) relationships; (iii) attendance to meetings, training, and workshops; (iv) membership of farmer in organizations’ administrative committees; (v) social visits and access to training; (vi) access to farming and market information; and (vii) fear of falling victims of unscrupulous private companies that cheat and swindle the farmers. However, while some motivations/factors are similar or common across some of the studies cited previously, other factors are not. Becoming a member of a co-operative society was influenced not only by the personal benefits of the farmers but also by other factors such as age and education. That is why some farmers decided to become members while others did not.

4.4. Perceived factors influencing farmers’ not-participating in AMCOS

Findings in show that majority (82.7%) of non-members of AMCOS agreed and strongly agreed that they failed to join the co-operatives because of strict membership requirements such as the subscription fee, infrastructure fund, service charges, organization tax, and other types of fees which were high for them. During FGDs, farmers in Lungo ward (Mvomero) reported not to belong to TUCOPRICOS AMCOS although their wives did because, in the study area, some husbands and wives owned property differently; hence, there were cases where women were AMCOS members while their husbands joined other associations. Non-members further reported that the co-operatives were costly in terms of membership and other financial obligations. However, in the farmers’ associations and groups, membership was not costly, for instance, if one were a member of Mvomero Out-growers Association (MOA).

Table 4. Perceived factors for farmers not joining AMCOS (n = 151).

About three quarters (74.1%) of the non-members of AMCOS agreed and strongly agreed that they were not interested in joining AMCOS because of lack of information on the functions of those co-operatives. During FGDs with non-members, farmers reported not being aware of any benefits of becoming a member of a co-operative society. Similarly, they were also not aware of any disadvantage of not being a member of a co-operative society. This is also because they were members of other farmers’ organizations like MOA and farmers’ groups which were performing better than AMCOS. The findings are similar to those by Gasana (Citation2011) in a study conducted in Rwanda who found that some smallholder farmers did not join co-operatives due to poor performance of the agricultural co-operative societies and being members of other associations which performed similar activities as the agricultural co-operative societies.

Findings in showed that 51.7% and 18.5% of non-members agreed and strongly agreed respectively that they did not belong to AMCOS for fear of being cheated by the officials of the co-operatives. During FGDs, the non-members reported that there were many incidences of AMCOS being indebted to their members despite the fact that sugar factories had already released payments for farmers through AMCOS bank accounts. This matter was reported in Mvomero district but not in Kilombero district. The respondents elaborated further that when sugar factory owners (Mtibwa Sugar Estates Limited) made payments to the sugarcane growers through AMCOS’ account, the management of AMCOS delayed effecting payment to the sugarcane growers who were members of the co-operatives. This was due to the mismanagement practices and low capitalization which resulted in the accumulation of debts owed to the members of the co-operatives. In this regard, non-members opted to belong to other farmers’ organizations such as MOA to avoid inconveniences caused by the inefficient management of the AMCOS. The finding is similar to that in a study by Pinto (Citation2009) which showed that most agricultural co-operatives experienced a decline in the number of active members due to poor production, low prices, delayed payments, mismanagement of the co-operatives, and subdued capitalization.

Additionally, about half (50.9%) and a tenth (10.6%) of the non-members agreed and strongly agreed respectively that inadequate farm inputs facilitation by AMCOS to their members was a factor that discouraged non-members from joining co-operatives. During FGDs with the non-members, they explained that farm inputs provided to the members of AMCOS were inadequate and discouraging; consequently, compelling them collaborate with a private company through their association, rather than join the AMCOS. They explained further that farmers who were members of AMCOS (TUCOPRICOS) in Mvomero District had frequently complained that fertilizers and improved seeds which they had secured through AMCOS were not given to them on time, for example, during 2016/2017 season; hence, they were ineffective in crop production.

Lastly, inadequate harvesting arrangements, transportation, marketing, and delays of payments by AMCOS to members were also mentioned as the factors which discouraged some farmers not to join AMCOS. Almost half (45.6%) and 6.6% of the non-members agreed and strongly agreed respectively that the aforementioned reasons discouraged them from joining AMCOS. According to these non-members, the arrangements made by the associations were better than those by AMCOS. During the FGDs in Kwadoli wards, non-members reported that sugarcane belonging to members of TUCOPRICOS-AMCOS were sometimes left unharvested, or uncollected and ferried to the factories because of inefficient harvesting and transport arrangements. However, this was not the case with farmers who were facilitated by MOA. Also, marketing services (pricing, weighing, and quality control) arrangements by AMCOS were poorer than those offered by the associations.

These findings are similar to those reported in other studies. For instance, Hellin, Lundy, and Meijer (Citation2007) found that farmers got discouraged from joining farmers’ organizations because of various reasons including high membership fees and farmers’ lack of trust in collective action. In a study done in Sagoti in Uganda by Egeru and Majaliwa (Citation2016), the findings revealed that failure in joining agricultural co-operatives was the result of high membership costs, lack of awareness of the benefits of farmers’ associations, connectedness, and favoritism of members. Similarly, other studies (Gasana Citation2011; Spielman, Cohen, and Mogues Citation2008; Tefera and Wold Citation2015) in Rwanda and Ethiopia revealed that smallholder farmers did not join agricultural co-operatives due to the following reasons: (i) they did not know the benefits of being members; (ii) farmers doubted that they would get back their shares; (iii) they did not trust the organization’s leadership and management; (iv) unawareness on benefits and functions of co-operatives; (vii) some reported not having land in the area where the co-operatives were located; and lastly (v) some of them reported to have inadequate money to meet membership financial requirements. These findings are similar to the ones reported by farmers in the study area. For example, farmers reported high membership fees and poor performance of the co-operatives in service delivery as the factors that discouraged them from joining agricultural co-operative societies.

4.5. Socio-economic and institutional determinants of farmers membership to AMCOS

This section presents data on determinants of farmers’ membership in AMCOS. presents the results which were computed through the binary logistic regression model of the selected socio-economic and institutional factors determining the farmers’ decisions in joining AMCOS. To avoid multicollinearity problem of the model, multicollinearity diagnosis was conducted before running the regression. The range of measurement was from 1.04 to 4.403 variance inflation factor (VIF). According to Tefera and Wold (Citation2015), if VIF exceed 10, it tends to be ‘troublesome’ or cause collinearity of the variable Xi, hence multicollinearity. Therefore, this study has the acceptable VIF of below 10. The Chi square value was 179.389, with df = 15 and was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) indicating that independent variables had a statistically significant influence on the dependent variables. Also, in the test of the effectiveness of the described model, the outcome variables were conducted through Hosmer-Lemeshow test and the result was 14.56, with df = 8, p ≥ 0.05. According to Hosmer and Lemeshow (Citation2000) a P- value greater than 0.05 implies that the model was fit to describe the outcome variables. A total of 14 socio-economic determinants were included in the binary logistic model to test their influence on farmers’ decision to join AMCOS. Only 6 out of 14 variables were found to significantly influence farmers into joining AMCOS. These variables were age, education, credit access, the amount of credit accessed, access to agricultural inputs and marketing services.

Table 5. Social, economic and institutional factors that influenced farmers to join AMCOS.

The findings in showed that age had a beta coefficient of 0.048 and the variable was highly statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05). This confirms the findings in which revealed that an increase in age was directly related to an increased possibility of joining AMCOS. This implies that the longer the farmers lived, the more the financial and other resources they accumulated and the more informed they become on the importance of AMCOS; hence, they tended to be active and engage themselves in activities of the AMCOS. Also is it because older farmers were more credible in group formation compared to younger farmers who tended to be unreliable. The study results are similar to the findings of the studies done by Nkurunziza (Citation2014) and Mrema (Citation2017) in Rwanda and Tanzania respectively who found that the age of the farmers significantly influenced one’s membership in co-operatives.

Education had a positive beta coefficient of 0.414 and was statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05). This means that an increase in the level of education by farmers increased their likelihood to join AMCOS.

The findings are in contrast with the ones in which showed that there was no significant difference between the level of education attained by members and non-members of AMCOS though the variable influenced farmers’ decision to join the AMCOS. This implies that, even though members and non-members of AMCOS had similar levels of education, the variable had positive influence on the farmers’ decision to join agricultural co-operative societies. Farmers who had received formal education were more likely to become members of AMCOS than those who had not owing to the differences in their understanding and awareness about the benefits of agricultural co-operative societies and procedures involved in acquiring membership. This finding is also similar to the one in a study by Cicek et al. (Citation2007) who found that the level education could be an indicator of the farmers’ capability to embrace appropriate agricultural technologies and new farm management practices. Findings by other scholars also have showed that one’s level of education positively influences farmers in rural areas to join agricultural co-operatives as it enhances their understanding of the logistics involved in AMCOS (Vargas, Bernard, and Dewina Citation2008). However, these findings are in contrast to the findings of a study conducted by Higuchi (Citation2014) in Peru which showed that farmers with low formal education had a high probability of joining co-operatives in order to access requisite knowledge and skills in agricultural issues which could enable them improve their production. This implies that most farmers in the study area had attained basic formal education as opposed to the farmers surveyed in the study by Higuchi (Citation2014) in Peru who were less educated and were practicing farming as their only vocation.

Credit access and the amount of credit accessed/received had beta coefficients of 1.804 and 0.000 respectively and were both statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05). This implies that accessing loan facilities and the amount of loan/credit to farmers increase the likelihood of the farmers joining AMCOS. Those who were not members were attracted by the way the members were assured of access to credit and higher amounts of credit obtained than that of non-members who got the same services on individual basis. During interviews with key informants (co-operatives managers) in Mvomero District, the TUCOPRICOS manager said:

Our AMCOS has a good relationship with the National Microfinance Bank and TUCO-SACCOS which enable us members to access agricultural loans through AMCOS guarantees. Mvomero (Mtibwa) – 25/09/2018.

Therefore, the smallholder farmers were likely to become members of AMCOS so as to access credit and other financial services with fewer requirements of collateral and low interest rates since farming was their only source of income. These findings are similar to those by Nkurunziza’s (Citation2014) study which revealed that access to affordable loans and the decision to join a farmer’s organization had a positive relationship. Also, the study findings are similar to those reported in a study by Kehinde and Kehinde (Citation2020) whose findings revealed that there was a positive relationship between credit access and membership in co-operatives in northern Nigeria. Conversely, findings in a study by Ekepu, Tirivanhu, and Nampala (Citation2017) showed that credit had no significant impact on one’s membership to farmers’ associations in Soroti District in Uganda. This can be explained by asserting that access to credit by farmers in Soroti was still low and could not be a significant determinant of membership in farmers’ associations, contrary to the cases at Kilombero and Mvomero as the AMCOS, through agreement with financial institutions, made access to credit for their members easy; hence, influencing the non-member farmers to join AMCOS.

Access to pesticides, fertilizers, and improved seed varieties had a negative beta coefficient of −0.361 and the variable was statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05). This means that farmers with access to pesticides, fertilizers and improved seed varieties from the local stores and shops were less likely to join AMCOS. In other words, the findings imply that those farmers with no possibility of accessing pesticides, fertilizers, and improved seeds varieties were more likely to join AMCOS so as to get those inputs. This finding is in line with that in a study by Ajah (Citation2015) which revealed that members of agricultural co-operatives had greater access to agricultural inputs than the non-members, implying that the governmental agencies and NGOs which are interested in agricultural growth and development should emphasize establishment of viable agricultural co-operative societies for smallholder farmers.

Access to information on marketing services and market prices had beta coefficient of 0.006 and was statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05). This implies that an increase in farmers’ access to marketing services and prices information from AMCOS enhanced the likelihood of farmers in joining agricultural co-operative societies. During FGDs, the farmers in the study areas were asked to indicate whether or not they accessed information on the prices of crops and marketing services. Majority of them cited their fellow farmers, co-operative organizations, and the radio as their sources of information. However, they were dissatisfied with the information of the prices of crops conveyed on radio as they normally did not reflect the actual selling prices in their localities. Thus, the only reliable and effective way of obtaining information on marketing services and prices of crops was from their fellow farmers and AMCOS.

Members of AMCOS who were sugarcane and cocoa growers in the study areas reported that AMCOS leaders were involved in negotiating the prices of their crops with the factory owners and then informed them through meetings and local communication channels. On the other hand, information about marketing services and prices of crops for non-members of AMCOS was accessed through their associations, fellow farmers, and the members of AMCOS. The study findings are similar to those reported by Mrema (Citation2017) in Rombo District that showed that accessing market information was an important determinant in coffee marketing. This is because information on coffee prices and other types of market information was delivered to the farmers through agricultural co-operatives rather than by private traders. This means that, in general, the information on crop prices and market services was important for a member’s decision on which channel to use in marketing his or her crop production. Another study by Tesha (Citation2010) showed that access to crop prices information before participating in the AMCOS had a significant influence on farmers’ decision to join AMCOS.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

This study attempted to examine the socio-economic and institutional determinants of farmers’ membership in AMCOS. Empirical evidence from farmers’ perceptions and which was confirmed by binary regression analysis showed that institutional factors were the major determinants of the farmers’ membership in AMCOS. Those determinants were mainly the agricultural support services offered by AMCOS.

Therefore, the study recommends that AMCOS should enhance their effectiveness and efficiency in the provision of agricultural support services so as to attract more farmers to join agricultural co-operative societies. Also, AMCOS should strive to reduce the costs involved in registering new members since the problem of high costs was among the key factors which discouraged farmers from joining the AMCOS as emphasized by non-members of AMCOS during FGDs.

Furthermore, the study recommends that there should be policy reviews by integrating microfinance and agricultural services and technical support to increase farmers’ membership in co-operatives. Also, acknowledging that the potential of cooperative enterprises had not been fully utilized partly due to an unfavorable legal and regulatory framework, specifically the microfinance regulatory framework which are partly regulated by Central Bank of Tanzania, Ministry of Finance and Tanzania Cooperative Development Commission.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- African Development Bank. 2002. “Agricultural Marketing System Development Programme.” Accessed 23 December 2018. https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/documents/project-and-operations/TZ-2002-072-EN-ADF-BD-WP-Tanzania-Agricultural-Marketing-Systems-Development-programmePdf.

- Ajah, J. 2015. “Comparative Analysis of Co-Operatives and Non-Co-Operative Farmers’ Access to Farm Inputs in Abuja, Nigeria.” European Journal of Sustainable Development 4 (1): 39–50. doi:10.14207/ejsd.2015.v4n1p39.

- Asante, O. B., and V. Afari-Sefa. 2011. “Determinants of Small-Scale Farmers’ Decision to Join Farmer-Based Organizations in Ghana.” African Journal of Agricultural Research 6 (10): 2273–2279.

- Balgah, R. A. 2019. “Factors Influencing Coffee Farmers’ Decisions to Join Cooperatives.” Sustainable Agriculture Research 8 (1): 42–58.

- Bjornlund, V., H. Bjornlund, and Andre F. Van Rooyen. 2020. “Why Agricultural Production in Sub-Saharan Africa Remains Low Compared to the Rest of the World – a Historical Perspective.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 36 (S1): S20–S53.

- Chibanda, M., G. F. Ortmann, and M. C. Lyne. 2009. “Institutional and Governance Factors Influencing the Performance of Selected Smallholder Agricultural co-Operatives in KwaZulu-Natal.” Agrekon 48 (3): 293–315. doi:10.1080/03031853.2009.9523828.

- Cicek, H., M. Tandogan, Y. Terzi, and M. Yardimci. 2007. “Effect of Some Technical and Socio-Economic Factors in Milk Production Costs in Dairy Enterprises in Western Turkey.” World Journal of Dairy Food Science 2: 69–73.

- Creswell, J. W. 2013. Research Design Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. London: Sage Publication Inc. 342pp.

- Egeru, A., and M. G. J. Majaliwa. 2016. “Hostages of Subsistence Cultivation: Can They be Bailed?” Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture 14 (1): 707–717.

- Ekepu, D., P. Tirivanhu, and P. Nampala. 2017. “Assessing Farmer Involvement in Collective Action for Enhancing the Sorghum Value Chain in Soroti, Uganda.” South African Journal of Agricultural Extension 45 (1): 118–130.

- EPNAV, 2012. “Enhancing Pro-poor Innovations in Natural Resources and Agricultural Value.” Accessed 7 june 2017. https:///Silo.tips_sokoine-university-of-agriculture.pdf

- FAO, 2015. “2014 Annual Report on FAO’s Projects and Activities in Support of Producer Organizations and Cooperatives.” Accessed in 8 February 2018. www.fao.org/3/i5055e/i5055e.pdf

- Frayne, O., K. Theron, and G. Gary. 1998. “New Generation Co-operatives Membership: How Do Members Differ from Non-Members.” Extension Report No. 40. North Dakota State University. USA. 8pp.

- Gasana, G. 2011. “Exploring the Determinants of Joining Dairy Farmers co-Operatives in Rwanda: A Perspective of Matimba and Isangano Co-Operatives.” Dissertation for Award of MSc Degree at International Institute of Social Studies, The Hague, Netherlands, 63pp.

- Gashaw, B. A., and S. M. Kibret. 2018. “Factors Influencing Farmers’ Membership Preferences in Agricultural Cooperatives in Ethiopia.” American Journal of Rural Development 6 (3): 94–103.

- Gebremichael, B. A. 2014. “The Role of Agricultural co-Operatives in Promoting Food Security and Rural Women’s Empowerment in Eastern Tigray Region.” Journal of Business Management and Social Sciences Research 4 (11): 96–110.

- Gillinson, S. 2004. “Why Cooperate? A Multi-Disciplinary Study of Collective Action.” Accessed 18 july 2018. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/22664/wp234.pdf

- Hellin, J., M. Lundy, and M. Meijer. 2007. “Farmer Organization and Market Access.” Working Paper No. 67. Collective Action and Property Right, Cali, Colombia. 37pp.

- Higuchi, A. 2014. “Impact of a Marketing co-Operatives on Cocoa Producers and Intermediaries: The Case of the Acopagro Co-Operatives in Peru.” Journal of Rural Cooperation 31 (12): 80–97.

- Hoken, H., and Q. Su. 2015. “Measuring the Effect of Agricultural Co-operatives on Household Income Using PSM-DID: A Case Study of a Rice-Producing Co-operatives in China.” Discussion Paper No. 539. Institute of Developing Economies, Japan. 30pp.

- Hosmer, D. W., and S. Lemeshow. 2000. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. 397pp.

- International Co-operatives Alliance. 2005. “Annual Report.” International Co-operatives Alliance, Colombia. 23pp.

- Karl, B., A. Bilgi, and Y. C. Elik. 2006. “Factors Affecting Farmers’ Decision to Enter Agricultural Cooperatives Using Random Utility Model in the South Eastern Anatolian Region of Turkey.” Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics Volume 107 (2): 115–127.

- Kayitesi, C. 2019. “Determinants of Membership and Benefits of Participation in Pyrethrum Cooperatives in Musanze District.” Rwanda Dissertation for Award of MSc Degree at the University of Nairobi. Nairobi, Kenya, 90pp.

- Kehinde, A. D., and M. A. Kehinde. 2020. “The Impact of Credit Access and Cooperative Membership on Food Security of Rural Households in South-Western Nigeria.” Journal of Agribusiness and Rural Development 3 (57): 255–268.

- Kigathi, C. C. W. 2016. “Motivating Factors for Dairy co-Operatives Membership in Kenya: A Case of Smallholder Dairy Farmer in Kiambuu Country.” Dissertation for Award of MBA at Strathmore University, Nairobi, Kenya, 63pp.

- Lewis, J., S. 2006. “The Function of Free Riders: Toward a Solution to the Problem of Collective Action.” Dissertation for Award of Doctor of Philosophy at College of Bowling Green State University, 192pp.

- Maghimbi, S. 1992. “The Abolition of Peasant co-Operatives and the Crisis in the Rural Economy of Tanzania.” In The Tanzanian Peasantry: Economy in Crisis, edited by G. Forster, and S. Maghimbi, 81–100. Avebury: Grower Publishing Company Ltd.

- Maghimbi, S. 2010. “Co-Operatives in Tanzania Mainland: Revival and Growth.” Working Paper No. 14. International Labour Office, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. 48pp.

- Mrema, M. J. 2017. “Co-Operatives Members’ Decisions on Coffee Marketing Channels and Factors Influencing Their Choices in Rombo District, Tanzania.” Dissertation for Award of MSc Degree at Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania, 90pp.

- Msangya, B., and Yihuan, W. 2016. Challenges for Small-Scale Rice Farmers: A Case Study of Ulanga District Morogoro, Tanzania. International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology 3 (6): 65–72.

- Msimango, B., and O. I. Oladele. 2013. “Factors Influencing Farmers’ Participation in Agricultural co-Operatives in Ngaka Modiri Molema District.” Journal of Human Ecology 23 (20): 113–119. doi:10.1080/09709274.2013.11906649

- Munyaneza, C., L. R. Kurwijila, N. S. Y. Mdoe, I. Baltenweck, and E. E. Twine. 2019. “Identification of Appropriate Indicators for Assessing Sustainability of Small-Holder Milk Production Systems in Tanzania.” Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 19 (1): 141–160.

- Njiru, D. R, Bett, H., Mary C Mutai, M., M. 2015. “Socioeconomic Factors that Influence Smallholder Farmers’ Membership in a Dairy Cooperative Society in Embu County, Kenya.” Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development 6 (9): 283–288

- Nkuhi, M. S., and A. P. Mbuya. 2017. “The Co-operative Societies Act 2013 and New Trends in the Management of Co-Operatives in Tanzania Mainland.” Accessed 6 February 2019. http://www.ngmaryo.com/heading-committees-leading-corporate-meetings-and-making-powerful-presentatio ns/.

- Nkurunziza, I. 2014. “Socio-Economic Factors Affecting Farmers’ Participation in Vertical Integration of the Coffee Value Chain in Huye District, Rwanda.” Dissertation for Award of MSc Degree at Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya, 83pp.

- Nugusse, W. Z. 2010. “Why Some Rural People Become Members of Agricultural Co-Operatives While Others Do Not.” Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics 2 (4): 138–144.

- Nugusse, W. Z., and J. Buysse. 2013. “Determinants of Rural People to Join Co-Operative in Northern Ethiopia.” International Journal of Social Economics 40 (12): 1094–1107. doi:10.1108/IJSE-07-2012-0138.

- Okello, J. J., O. K. Kirui, G. W. Njiraini, and Z. M. Gitonga. 2012. “Drivers of use of Information and Communication Technologies by Farm Households: The Case of Smallholder Farmers in Kenya.” Journal of Agricultural Science 4 (2): 111–124. doi:10.5539/jas.v4n2p111.

- Okwoche, V., B. Osogura, and P. Ckukwudi. 2012. “Evaluation of Agricultural Credit Utilization by Co-Operatives Farmers in Benue State of Nigeria.” European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences 47: 18–27.

- Ollila, P., J. Nilsson, and C. Bromssen. 2011. “Characteristics of Membership in Agricultural co-Operatives.” Paper for the International Conference Co-Operatives Responses and Global Challenges, Held in Berlin, Germany, 21–23 March, 2012. 10pp.

- Olson, M. 1965. The Logic of Collection Action. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Pinto, P. C. 2009. Agricultural Co-Operatives and Farmers Organizations: Role in Rural Development and Poverty Reduction. Sweden: Swedish Co-operatives Centre. 7pp.

- RSA. 2005. “Co-operative Act, 2005.” Government Gazette, 18 August 2005, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Schwettmann, J. 2014. “The Role of Cooperatives in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals - The Economic Dimension” accessed in 23 may 2019. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/2014/coopsegm/Schwettmann.pdf

- Seimu, L. M. S. 2015. “The Growth and Development of Coffee and Cotton Marketing Co-Operatives in Tanzania, c.1932-1982.” Thesis for Award of PhD at University of Central Lancashire, UK, 375pp.

- Spielman, D. J., M. J. Cohen, and T. Mogues. 2008. Mobilizing Rural Institutions for Sustainable Livelihoods and Equitable Development: A Case Study of Local Governance and Smallholder Co-Operatives in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: International Food Policy Research Institute. 28pp.

- TCDC. 2017. “Statistics by Region and Co-Operatives Type.” Accessed 20 December 2018. https://www.ushirika.go.tz/statistics/.

- Tefera, E., and A. G. H. Wold. 2015. “Performance and Determinants of Household’s Participation in Dairy Marketing Co-Operatives: The Case of Lemu-Arya and Bekoji Dairy Marketing co-Operatives, Arsi Zone, Oromiya Region, Ethiopia.” Global Journal of Emerging Trends in e-Business, Marketing and Consumer Psychology 1 (1): 240–258.

- Tesha, J. D. 2010. “Contribution of Agricultural Marketing co-Operatives in Poverty Alleviation: A Case Study of Cashew nut Farmers in Mtwara Region.” Dissertation for Award of MSc Degree at Sokoine University Agriculture. Morogoro, Tanzania, 78pp.

- TFC. 2006. “A simplified Guide to the Co-Operatives Development Policy and the Co-operative Societies Act of Tanzania Mainland.” Accessed 5 July 2018. http://www.hakikazi.org/papers/Co-operatives.pdf.

- URT, 2013. “The Cooperative Societies Act.” Gazette of United republic of Tanzania 95 (1): 1–111.

- URT, 2017. Agricultural Sector Development Programme Phase II (ASDP II). Accessed in 6 January 2018. https://asdp.kilimo.go.tz

- Vargas, R., T. Bernard, and R. Dewina. 2008. “Co-operatives Behavior in Rural Uganda: Evidence from the Uganda National Household Survey.” Accessed February 2018. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b442/07806e0111d2955730d3a0ea67965d88d2bb.pdf.

- Yau, Y. 2011. “Willingness to Participate in Collective Action: The Case of Multi-Owner Housing Management.” European Real Estate Conference, Eindhoven, 15–17 June 2011. pp. 1–22.

- Zheng, S., Z. Wang, and T. O. Awokuse. 2012. “Determinants of Producers’ Participation in Agricultural co-Operative: Evidence from Northern China.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 34 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1093/aepp/ppr044.