?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In addition to performing their basic fiscal functions, governments in developing economies are constantly challenged by new and re-emerging socioeconomic issues such as insecurity, hunger, natural disaster, collapsing infrastructure and disease outbreaks which have made the competition for limited resources fierce and hence the need to mobilize funds. Revenue mobilization forms a critical crux of development plans in any economy and the public finance literature is replete with an investigation of factors that motivate revenue mobilization. In spite of the documented indisputable roles of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the economic performance of developing economies and the resultant aggression in mobilizing FDI, its implications for tax revenue have not been well investigated. This study, therefore, assessed the role of FDI in mobilizing tax revenue in South Africa. Accounting for the potential structural break, the study used time series data from 1994 to 2021 within the Autoregressive Distributed Lag–Error Correction Model (ARDL-ECM). The results showed that FDI has a statistically significant negative effect on tax revenue. Following the outcomes of this study, it is recommended that in addition to sound public finance policies, the government should prioritize efficient investment policies in its FDI mobilization drive.

1. Introduction

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has again exemplified the significance of public revenue, especially in developing economies. Fiscal buoyancy was a significant factor in how countries responded to the pandemic. Aside from the needed resources in the health sector, the aftermath socioeconomic challenges of the scourge also have huge financial implications. While the poor developing countries were waiting on development partners for assistance due to fiscal constraints imposed by lean public resources, many rich developed countries were able to actively rise to the occasion owing to buoyant fiscal capacity. Thus, the latter were able to forestall various socioeconomic challenges fueled by the pandemic, especially in the wake of the aftermath lockdowns. On the contrary, developing economies are still grappling with diverse socioeconomic woes exacerbated by the pandemic (OECD Citation2020; World Bank Citation2021b).

Although sources of public finance are diverse and vary in characteristics, due to features such as sustainability and stability, tax revenue has been pinpointed as a more reliable and efficient source of financing public expenditure compared to other sources such as foreign official development assistance (ODA), foreign investment inflows and public debt which are often rippled with unsustainability and volatility. However, owing to the prevalence of low levels of development coupled with high levels of tax evasion and avoidance, developing countries, particularly those of the African continent, are challenged in mobilizing tax revenue. Hence, low tax revenue thus constitutes both a cause and product of underdevelopment in developing economies (Besley and Persson Citation2014; World Bank Citation2021a).

Like in many developing countries, the issue of low tax revenue is very pertinent in South Africa. Aside from the challenge of recovering from the economic ruins associated with the apartheid political legacy, the South African economy is also saddled with diverse socioeconomic challenges including high unemployment, unparalleled income inequality, endemic diseases and infrastructure collapse. Thus, competition for limited financial resources has become fierce in the country. Although South Africa performs fairly well relative to other African countries in terms of tax generation (Revenue Statistics in Africa 2022) with average tax revenue as a share of GDP higher than the United Nations’ recommended tax threshold of 15 percent required for achieving the SDGs (United Nations Citation2022; Lewis and Alton Citation2015), the economy is nonetheless combatted with low revenue challenges. The progress recorded in tax collection in the post-apartheid era has somewhat stagnated, with average tax revenue as a share of GDP rising minimally from 21.1 percent in the first decade post-apartheid to 23.5 percent in the second decade (WDI Citation2022). This has been made worse with the aftermath effects of the coronavirus pandemic with significant declines recorded across all categories of taxes (National Treasury South Africa Citation2022)

Owing to the pertinence of revenue in public fiscal behavior and the relative stability of tax revenue, research effort has been geared towardunderstanding factors that are critical to mobilizing tax revenue. While the ongoing research has yielded a growing large body of evidence (Gupta Citation2007; Ade, Rossouw, and Gwatidzo Citation2018; Gnangnon Citation2019; Arodoye and Izevbigie Citation2019; Manamba and Kaaya Citation2020; Johnson and Omodero Citation2021; Arvin, Pradhan, and Nair Citation2021; Olaniyan et al. Citation2020; Camara Citation2020) empirical evidence on South Africa is lacking in spite of the significance of tax revenue in the economy. The closest study on the subject matter is the work of Ade, Rossouw, and Gwatidzo (Citation2018) which investigated the macroeconomic influencers of tax revenue in the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC). While South Africa is very relevant to SADC, being the largest economy in the trade bloc, the findings of the study cannot be generalized for individual countries making up the panel. Specifically, due to the problem of heterogeneity inherent in such studies, it is limited in offering precise insight into the roles of the investigated factors in revenue generation in South Africa. We, therefore, seek to contribute to this growing strand of the literature by evaluating the role of foreign direct investment (hereafter FDI) in tax revenue mobilization in South Africa. Our interest stems largely from the relevance of FDI in the South African economy. Since the political transition of 1994, FDI has been topical in the recovery and sustainability plans of the South African economy. The unequivocal import of FDI to the South African economy is exemplified by the post-apartheid Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) policy of 1996. FDI has been a typical influencer of the South African economy (Makhoba and Kaseeram Citation2019; Stolzenburg et al. (Citation2020)) rising from $968.8 million in 2000 to $6.5 billion and $9.8 billion in 2005 and 2008, respectively. Upon recovery from the financial crisis of 2007/2008, FDI rose to $8.2 billion in 2013 and stood at $5.1 billion in 2019 (World Bank Development Indicator (WDI) Citation2022). Moreover, following the global rebounding from the slump due to the covid-19 pandemic, South Africa was the only African country among the top ten FDI recipient economies in 2021 (UNCTAD Citation2022)

As typical of many developing countries, South Africa has been in fierce competition for FDI using various incentives including tax policies. It is thus quite surprising that in spite of the twin issues of aggressive FDI mobilization and paucity of public funds in South Africa, an empirical investigation between the two salient variables is lacking in the literature. Therefore, given the continuous intense mobilization of FDI, its associated incentivizing tax policies and the constraint of limited public resources in fiscal management, analysis of the relationship between FDI and tax revenue is worth considering for South Africa. While notable roles of FDI in South Africa have been widely investigated across diverse macroeconomic performance indicators,Footnote1 to the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt at investigating the tax revenue-FDI nexus in South Africa. The rest of the paper is couched as follows: a review of the empirical literature is presented in the next section, followed by methodology, findings and conclusion.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical review

Following prior studies such as Heller (Citation1975), Summers (Citation1981) and Leuthold (Citation1991) which offered a theoretical framework for analyzing the effect of policy variables including FDI on tax revenue, theoretical exposition on the interlinkages between FDI and tax generation has likewise been provided by Aitken and Harrison (Citation1999), Faeth (Citation2011) and Nguyen et al. (Citation2013). A general argument common to the theoretical models is that, in terms of tax revenue, host countries can either gain or lose from FDI expansion. Government can raise taxes from FDI by levying an optimum tax on foreign investments. Similarly, tax revenue can be eroded due to the competition for FDI among countries. Due to the pressure arising from international competition for FDI, the government can engage in excessive incentivizing tax policy, thereby losing potential tax revenue. The theoretical basis for the role of FDI in tax revenue was succinctly presented by Nguyen et al. (Citation2013). The authors developed a theoretical model of the role of FDI I tax revenue which identified three important pathways through which FDI may impact tax revenue – competition effect, demand creation effect and technological spillover effect.

The competition effect arises from the ensuing competition between domestic firms and foreign investment which could be positive or negative. FDI could generate positive spillover in the host economy by creating backward linkages with the rest of the economy (Faeth Citation2011). This could result in increased efficiency with attendant increased total factor productivity and a boost in domestic production, thereby generating an increase in tax revenue. Contrariwise, negative competition could harm the development of the host economy by crowding out domestic investment (Haddad and Harrison Citation1993; Nguyen et al. Citation2013) with a resultant lower output effect and shrinkage of potential tax revenue.

Meanwhile, the demand creation effect is hinged on the theoretical premise that FDI fuel tax revenue by creating direct and indirect demand. FDI creates direct demand by locally sourcing its inputs, thereby creating a secondary demand for inputs (Nguyen et al. Citation2013). FDI likewise generates an indirect demand for inputs by driving up the output level of domestic intermediate firms or spurring the entry of new firms. The surge in activities in the host economy catalyzed by the presence of MNEs, thus, implies a consequential rise in tax revenue.

As regards technological spillover, the effects could be positive or negative. The potential effect of FDI technological spillover effect on tax revenue is largely determined by the absorptive capacity of domestic firms. With strong absorptive capacity, firms are able to innovate using the transferred knowledge, thereby enhancing their production. However, firms having low absorptive capacity are crowded out due to their inability to catch up with the new technological trend.

2.2. Empirical review

The review of extant literature showed the existence of a small but growing body of empirical research on the influencing role of FDI in tax revenue mobilization. The review also showed that while there is sizeable evidence of tax revenue enhancing capacity of FDI, there also exists small-scale evidence of contradicting findings. Since the issue of paucity of public funds is relatively more prevalent in developing countries than developed, the review further showed that a larger proportion of the extant studies investigated the nexus for developing economies either within a panel or time series framework.

Bayar and Ozturk (Citation2018) examined the relationship and direction of causality between FDI and tax revenue in a pool of 33 OECD member countries. The estimated coefficients of the empirical analysis showed that unidirectional causality runs from FDI to tax revenue in the analyzed countries. Contrariwise, Gaspareniene et al. (Citation2022) showed that while outward FDI outflow stimulates tax revenue in a sample of European Union countries, FDI inflow has no significant relationship with tax revenue, in a larger dataset of 172 countries comprising both developed and developing countries, Gnangnon (Citation2017) tested the effect of FDI inflow on resource and non-resource corporate tax revenue. The system GMM estimates established that the directions of the estimated relationships are dependent on the size of the FDI inflow. Specifically, the authors found that below a threshold level of 4.43 percent, FDI inflow has a significant negative effect on total non-resource tax revenue, while for non-resource corporate tax revenue, a threshold effect of 0.33 percent exists.

Evidence also exists on panel of developing and emerging regions as well as on specific regions such as Asia, Latin and Africa. In a pool of 90 developing economies, Camara (Citation2022) tested if FDI contributes to revenue mobilization. The investigation analyzed within the framework of the system GMM corroborates the stance that FDI spurs tax revenue in developing countries. The result was, however, refuted for resource-exporting countries due to a lack of statistical significance. The same stance was earlier documented by Pratomo (Citation2020) for a panel of developing countries. Exploring the nexus in Pakistan, Mahmood and Chaudhary (Citation2013) presented evidence of a positive relationship. Meanwhile, in a later study on the Pakistani economy, Tabasam (Citation2014) argued that the direction of the relationship is negative. Analyzing the tax revenue-FDI relation using the firm-level data, the GMM estimates of Balıkçıoğ, Dalgıç, and Fazlıoğlu (Citation2016) supported the revenue spurring effect of FDI in Turkey. Moreover, Ha, Minh, and Binh (Citation2022) concluded that FDI is a significant predictor of tax revenue size in the Southeast Asian region.

For the African continent, sub-regions and countries, Olaniyan et al. (Citation2020) explored the relationship with Nigeria. the author and his colleagues found that FDI has a positive association with the size of mobilized tax revenue and the association is particularly strong for company income taxes. In a related study on the Nigerian economy, Makwe and Oladele (Citation2020) argued that the revenue generation effect of FDI is sector dependent. While FDI in the agriculture and manufacturing sector does not exert significant effects on various estimated types of tax revenue, FDI in the mining and quarrying sector was found to have a significant positive effect on company income tax and petroleum profit tax. Analyzing factors that determine tax revenue in SADC Ade, Rossouw, and Gwatidzo (Citation2018) documented that FDI constitutes a significant predictor of tax revenue size in the trade bloc. Although the study regression analysis included data on the South African economy due to the potential challenge of heterogeneity in pooled analyses, the study is limited in offering an accurate insight into the relationship in individual countries making up the panel.

Komlagan and Okey (Citation2013) similarly documented a positive effect of FDI on tax revenue in a pooled analysis of Western African countries. Contrary findings were, however, reported by Binha (Citation2021) for Zimbabwe. The regression estimates specifically established a significant negative effect in the short run, while no significant relationship was found in the long run.

Following the review of related research, we uncovered that the size of the FDI-tax revenue is particularly small in the African continent and to the best of our knowledge, no study has examined the relationship in the context of the South African economy. While Ade, Rossouw, and Gwatidzo (Citation2018) included data on FDI to investigate determinants of tax revenue in SADC, the findings of the study cannot be generalized for specific countries making up the panel due to the challenge of heterogeneity in pooled analyses, hence this study.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data source and description

For the purpose of investigating the influence of FDI on revenue mobilization efforts in South Africa, time series data were collected for 1994–2021. Our choice of the scope of the study is the post-apartheid period which we considered more appropriate given certain peculiarities of the South African economy which may have implications for our study. Aside from the consideration for political transition, the choice of an earlier period might not be suitable given the focus of our study on FDI. Apart from the fact that the periods preceding our start year were characterized by sanctions and boycotts, Namibia was part of South Africa until 1990. All these important events are capable of introducing structural breaks into our models and ignoring them in our choice of scope could render our findings invalid.

To ensure uniformity in measurement, all data employed in this study were sourced from the World Development Indicators (WDI). The following studies of influence in public finance and development economics such as Ofori, Ofori, and Asongu (Citation2021) and Olayeni et al. (Citation2022), tax revenue (TAXR) and FDI were measured by total tax revenue as a share of GDP and FDI inflow as a share of GDP, respectively.

Moreover, for the purpose of estimating a robust revenue model void of error due to omitted variables, we took the clue from empirical evidence to choose macroeconomic indicators as control variables which have been identified in the literature as significant predictors of tax revenue were adopted as control variables. While our choice of variables is motivated by data availability, we also made consideration for our study context. In particular, we incorporated into our model the level of economic growth (GDPG) and financial development (FINDEV). The level of growth of an economy does not only indicate its level of economic activities but also the level of opportunities for labor market participation, which are significant determinants of the capacity of tax authorities to impose and collect taxes (Ofori, Ofori, and Asongu Citation2021; Gnangnon Citation2022). In the same vein, financial development plays a potential key role in tax revenue mobilization. In addition to increasing the tax base through corporate and personal income taxes payable by financial institutions, financial development on one hand may boost tax revenue by fostering tax compliance and tax recovery through various banking services such as ICT-enabled platforms for seamless payment options, while it may aid multinationals in repatriating profits through the diffusion of financial technology (Hanrahan Citation2021) Moreover, in the sub-Saharan African (SSA) region, South Africa has the most developed and sophisticated financial sector which is also top-ranked globally (Akinboade and Makina Citation2006; World Bank Citation2018) Hence, we adopted data on GDP growth rate to represent the level of economic growth, while financial depth is proxied by data on the money supply to represent financial development.

In addition, data, on trade as a share of GDP (TRADE), are used to account for the openness of the South African economy evidenced by its participation in cross-border trades. Openness to trade has multifaceted links to tax generation vis-à-vis its implications for various categories of taxes including income taxes, company taxes and international trade taxes. Finally, we used household consumption expenditure (CONEXP) to represent the level of spending in the economy (Agbeyegbe, Stotsky, and WoldeMariam Citation2006; Audu Citation2020; Gnangnon Citation2022).

3.2. Technique of estimation and model specification

Time series data possess certain attributes which are critical for the selection of appropriate methods of analysis. An understanding of these unique characteristics is essential in making valid and sound decisions about the econometric estimation method (Shrestha and Bhatta Citation2018). Important examples of such attributes are the autoregressive nature of time series which dictates that the current values of a series may be correlated with its past values. Also, the order of integration of the series of interests and the existence of a cointegrating relationship among them are crucial determinants of a suitable methodological framework for a time series analysis. In terms of order of integration, a macroeconomic variable can either be stationary or non-stationary. It is stationary, if its values tend to adjust back to its long-run average values and its features are not affected by the change in time only; and in the case of reverse situations, the variable is said to be non-stationary. For a cointegrating relationship on the other hand, the series must share co-movement over a long period of time (Engle and Granger Citation1987; Pesaran, Shin, and Smith Citation2001).

3.2.1. Stationarity (Unit root) test

Application of estimation methods to time series analysis without careful consideration of the stationarity properties of the series of interest may lead to the problem of spurious regression such that the regression results will suggest significant relationships among variables when in the real sense, the variables are uncorrelated. Inferences based on the outcomes of such regressions will be misleading. Thus, we assessed the unit root property of the series. While conventional unit root tests, such as Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Philip-Perron (PP), are often used in time series studies, these methods have been criticized on the ground that they are inefficient in handling series with a structural break. While we tried to mitigate the challenge of a structural break by our choice of study period, we are not unaware that our selected study period might still be affected by structural changes due to the global financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic. Hence, we chose unit root with break test as offered by the EViews 12 statistical package which followed the framework of authors such as Perron (Citation1989), Vogelsang and Perron (Citation1998) and Zivot and Andrew (Citation1992). The results for the unit root tests are presented in .

Table 1. Unit root with a structural break.

Based on the reported t-statistics and the associated probability values, the null hypothesis of the unit root was rejected for all the series either at level or at the first difference. Specifically, the series of FDI and GDPG are stationary at the level, while others are stationary at the first difference. Thus, our variables are a combination of both the I(0) and I(1) series.

3.2.2. Cointegration-bound test

Following the confirmation of the stationarity attributes of our variables, we proceeded to test for cointegration among the variables. For this purpose, we chose the Bound cointegration test of Pesaran, Shin, and Smith (Citation2001) which has been adjudged advantageous over other cointegration tests such as Engle and Granger (Citation1987) and Johansen (Citation1991) which require that all variables of interest are integrated of order one I(1). On the contrary, the bound test is robust and efficient in testing for the cointegration either I(0) or I(1) variables and even a combination of both orders of integration. And since our model consists of combinations of I(0) and I(1) variables, it is certain that we adopt the Bound test.

The Bound cointegration test is based on F-statistics with the null hypothesis of no cointegration among the regression variables. Decisions on the existence of cointegration or otherwise are made by comparing the F-statistics with the associated lower I(0) and upper I(1) critical values. The null hypothesis of no level relationship (cointegration) between the dependent variable and the explanatory variables is accepted if the value of the F-statistics is below the lower critical bound, contrariwise, the null is rejected if the F-statistics is above the upper critical bound. The cointegration test is inconclusive if the F-statistical value lies within the lower and upper critical bound. The results of the Bound cointegration test for our adopted series are reported in . The null hypothesis of no cointegration among the series was rejected at all the reported levels of significance. In particular, the reported F-statistic (42. 91) is greater than the upper bound critical value even at 1 percent level of significance (4.68).

Table 2. Bound cointegration test.

3.2.3. Autoregressive distributed lag error correction (ARDL-ECM) approach

Since our analysis is aimed at making sound policy inferences from the analysis of past data, and our test of stationarity suggests that the series are combinations of I(0) and I(1) variables, the Autoregressive Distributed Lag Error Correction (ARDL-ECM) framework of Pesaran and Shin (Citation1998) and Pesaran, Shin, and Smith (Citation2001) was chosen for the empirical analysis. ARDL has been adjudged efficient in econometric analyses concerned with making inferences from past data. In fact, ARDL provides a robust framework for the analyses involving distributed lagged changes, i.e, change in an economic variable which is capable of causing changes in other economic variables beyond the current period (Pesaran, Shin, and Smith Citation2001; Shrestha and Bhatta Citation2018). Moreover, its ability to extract long-run relationships from short-run dynamics has also made it appealing in estimating long-run relationships in dynamic single-equation regressions (Harris and Sollis Citation2003)

Furthermore, empirical comparisons of ARDL with other similar single-equation cointegration techniques have shown strong pieces of evidence that ARDL is more advantageous (Harris and Sollis Citation2003; Panapoulou and Pittis Citation2004). Aside from its flexibility and efficiency in small sample size, it has also been found optimal and more feasible in cointegrating regressions relative to other cointegrating estimators such as the fully modified and dynamic ordinary least square (FMOLS and DOLS) (Pesaran and Shin Citation1998). As opposed to other methods in the family of parametric single-equation cointegration estimators, the ARDL model has the capacity to mitigate the second-order asymptotic effects of cointegration. Hence, it performs better in terms of estimation accuracy and sound statistical inferences even in the presence of endogenous variables (Harris and Sollis Citation2003; Panapoulou and Pittis Citation2004)

4. ARDL-ECM estimation result and discussion

Consequent upon confirmation of all ARDL pre-estimation conditions, the study proceeded to estimate an ARDL-ECM model. As earlier indicated, we sought to account for the possible effects of structural changes in our data. Since our breakpoints are known prior, we chose the Chow breakpoint test of Gregory Chow (Citation1960). Based on the reported F-statistics (2.133) and its associated level of significance (0.105), we accepted the null of no structural break. Due to our not-so-large sample size, we affirmed the robustness of the significance level of the test by testing for homoscedasticity in our model. The Breusch–Pagan-Godfrey heteroscedasticity test showed that the error term is homoscedastic. Following the establishment of the absence of a structural break in the data, the ARDL model is estimated as follows.

(1)

(1) where TAXR and FDI are as earlier defined. CTRL represents a vector of the chosen control variables including GDPG, TRADE, FINDEV and CONEXP. Δ represents the short-run, thus, ϕ, γ, and ѱ represent the coefficients of the short-run dynamics, while

account for the long-run relationships. The error term at time

is captured as

Upon confirmation of cointegration among the variables, we run an error correction model, as suggested by Pesaran, Shin, and Smith (Citation2001).

(2)

(2)

is the error correction term whose coefficient

measures the speed of adjustment of the model toward equilibrium.

The ARDL-ECM results are presented in . Based on the coefficients of the short-run dynamics, tax revenue at lag 1 has, a significant negative effect on tax revenue in the current period. Although this is unexpected in that a prior, past tax revenue is expected to have a positive effect on current revenue mobilization. The result might however be because tax revenue mobilization is a long-run phenomenon such that the immediate past value of tax revenue may not impact the current value. Except at lag zero, the influence of FDI on tax revenue is positive at both lags 1 and 2. FDI has multichannel indirect effects on tax revenue generation through its direct links to economic growth. For instance, FDI stimulates economic growth by enhancing employment generation, technological transfer and economies of scale which boosts output growth. FDI may, therefore, expand tax revenue through increased income and sale taxes as well as company income and profit taxes (Olaniyan et al. Citation2020; Camara Citation2022). The stance that the growth of an economy is crucial for tax revenue mobilization (Ofori, Ofori, and Asongu Citation2021) was only affirmed at lag zero, while the coefficient is negative and statistically significant at lag one. For our measure of financial development, the coefficient at lag zero is negative and statistically significant, while at lag one, the coefficient is positive and statistically significant. The mixed findings at different lag periods might be because tax generation is a long-run phenomenon, hence the periods are too short to uncover the real effects of the variables. Still, on the short-run results, the country’s openness to trade (TRADE) exerts a negative effect on tax revenue in both lags 0 and 1. The statistically significant negative influence of trade could be due to the removal of trade-related tariffs in a bid to promote trade. Moreover, the result could be due to the challenge of profit shifting by multinationals due to weak capacity in developing countries. Arezki et al. (Citation2021) contend that trade liberalization fuels tax competition and lowers the cost of cross-border capital mobility, thereby offering multinational opportunities to shift profits to low-tax countries, otherwise known as tax havens. Finally, the parameters of consumption expenditure (CONSEXP) reveal that while CONSEXP inhibits tax revenue at lag zero, it stimulates tax revenue at lag 1. The results might be due to the difference in the period.. Moreover, the model error correction term (ECM(-1)), which measures the speed of adjustment toward equilibrium, is correctly signed and statistically significant. This implies that in the event of short-run disequilibrium, the system is capable of reverting to the long-run equilibrium. The ECM coefficient thus indicates that all things being equal, in the event of disequilibrium, the model will adjust to long-run equilibrium with a speed of adjustment of 74 percent.

Table 3. ARDL-ECM regression results.

For the long-run estimates, the coefficient of FDI is negatively signed and statistically significant at a 5 percent level of significance. This finding suggests that in the long run, FDI has a reducing effect on mobilized tax revenue in South Africa. This is quite startling given the expectation that FDI would enhance tax revenue mobilization, as suggested by the short-run results, by enlarging the tax base through job creation, increased corporate profit and sales tax. However, while this finding negates the research outcomes of Balıkçıoğ, Dalgıç, and Fazlıoğlu (Citation2016), Olaniyan et al. (Citation2020), Pratomo (Citation2020) and Amendolagine, De Pascale, and Faccilongo (Citation2021), it resonates with those of Binha (Citation2021) and Tabasam (Citation2014).

An important line of argument for the observed result could be the challenge of profit shifting by multinational enterprises (MNEs). In spite of its active participation in the OECD-G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project (BEPS) and subsequent adherence and infusion of the recommendations to its tax legislations, South Africa like most developing economies is still plagued by MNEs’ exploitation of differences in tax rates across countries. In a bid to avoid the payment of higher tax rates in host countries, MNEs through diverse means shift profit to low-tax countries known as tax havens and this has led to significant loss of tax revenue, especially in developing countries lacking the expertise to curb the challenge (OECD Citation2015, Citation2017; Jansky and Palansky Citation2019; Reynolds and Wier Citation2016). Reynolds and Wier (Citation2016) estimated profit shifting in South Africa and the attendant implications for the Republic’s revenue. The study does not only affirm the existence of profit shifting in South Africa, but it also found that profit shifting has led to significant revenue losses in the country.

Moreover, the estimated results could be due to the unintended consequences of excessive liberal investment policies targeted at boosting FDI inflow. In competing for FDI inflows, countries offer competitive incentives including reduced tax rates, tax holidays and exemptions with potential consequences of low tax revenue (Etter-Phoya, Meinzer, and Lima Citation2020; Laudage Citation2020). Furthermore, the obtained results could also be a result of our adopted measure of tax revenue - aggregate total tax revenues This could have obscured the actual effect of FDI on mobilized revenue. While FDI might not have positively impacted aggregate tax revenue, there could be evidence of positive association with specific categories of tax revenue such as corporate taxes and value-added tax (VAT) (Amendolagine, De Pascale, and Faccilongo Citation2021; Gaspareniene et al. Citation2022)

For other correlates of tax revenue employed in this study, coefficients of our proxies of economic growth (GDPG), trade openness (TRADE), financial development (FINDEV) consumption expenditure (CONSEXP) are positive and statistically significant. This implies that all the adopted control variables have a significant positive influence on generated tax revenue. Aside from the widely documented near consensus on the pro-revenue effect of financial development (Oz-Yalaman Citation2019; Gnangnon Citation2022), the reported positive effect is not surprising given that South Africa has the most sophisticated financial system in the African continent with robust rating in various financial indices including depth, access and efficiency development (Akinboade and Makina Citation2006; IMF Citation2016; World Bank Citation2018). Hence, in addition to increasing the tax base through corporate and personal income taxes payable by financial institutions, financial development might aid in boosting tax revenue by fostering tax compliance and tax recovery through various financial services such as ICT-enabled platforms for seamless payment options.

In the same vein, positive nexuses between economic growth and tax revenue on one hand and trade openness and tax revenue on the other hand have been empirically founded. For example, Ofori, Ofori, and Asongu (Citation2021) averred the tax revenue-boosting capacity of economic development on the ground that the latter signaled by growth in GDP indicates increased productivity with attendant benefits of growing industrialization, rising employment generation, increasing income and consumption, and hence enhanced capacity to generate tax. The positive economic growth-tax revenue nexus was likewise reported in prior studies by Gupta (Citation2007) and Gnangnon (Citation2019). Although the estimated positive nexus between trade openness and tax revenue is not well supported in the literature hinging on the argument that trade openness erodes tax revenue by tariffs removal (Khattry and Rao, Citation2002; Shrestha, Kotani, and Kakinaka Citation2021), the obtained results might be due to the existing sound trade policies of South Africa. Gnangnon (Citation2022), however, argued that a higher degree of openness to trade serves as a stimulant for tax revenue generation.

4.1. Post-estimation diagnostic test

In the ARDL-ECM model, certain post-estimation tests are carried out to confirm that the regression estimates satisfy the assumption of the classical linear regression. These tests are crucial to determining the consistency and efficiency of the estimation results. They include the serial autocorrelation test, which dictates that the error term of the model, is not correlated with the regressors and the heteroskedasticity test which examines the constancy of the error term variance. The results of the post-estimation test are presented in .

Table 4. Post-estimation diagnostic test results.

We adopted the Breusch–Pagan LM test to test for serial autocorrelation. Based on the probability values of the F-statistics, the null hypothesis of no serial autocorrelation was accepted. Also, for the test of homoskedasticity of the error term variance, we employed the Arch heteroskedasticity test and the null hypothesis of homoscedasticity was accepted for the estimated regression, as suggested by the probability values of the F-statistics.

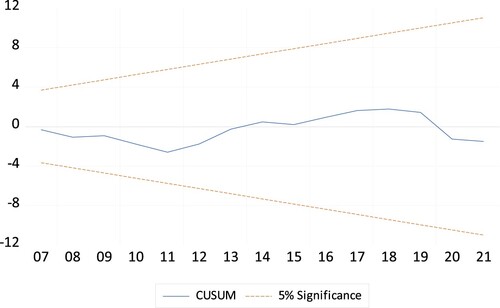

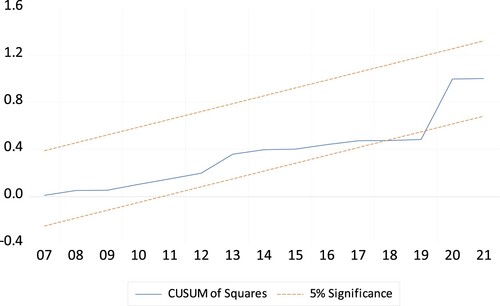

In addition, we tested for the stability of the regression model using the cumulative sum (CUSUM) test and the cumulative sum of squares (CUSUMSQ) test. The test graphs suggested that the parameters of the estimated equation are stable as the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ lines lie within the 5 percent critical lines for the model (the graphs are presented in the appendix).

5. Conclusion

Although the issue of FDI has long dominated the literature, its role in tax revenue mobilization has not been well explored, thus there is little empirical evidence on the FDI-tax revenue nexus. This study, therefore, contributes to the small but growing strand of the FDI literature by investigating the nexus for the South African economy focusing on the post-Apartheid period (1994–2021).

The empirical analysis estimated within the ARDL-ECM framework showed that FDI has a significant negative effect on tax revenue in South Africa. While the result is quite intriguing given the potential multifaceted channels through which FDI could enhance tax revenue, the findings might not be unconnected to the challenge of profit shifting by MNEs. Furthermore, the result could be connected to our adopted measure of tax revenue. The aggregate total tax revenues could have obscured the effect of FDI on specific categories of tax revenue.

Based on the outcomes of this study, it is recommended that while the South African economy continues with its aggressive foreign investment mobilization strategies, it should be very tactical in its investment policies. In a bid to attract foreign investment, the government should be cautious in the formulation of profit-based tax incentives such as tax exemptions, tax holidays and other investment-related policies to mitigate the inadvertent consequences associated with such policies. In addition, while the attraction of foreign investment remains topical in development strategies, the country should remain steadfast in its adherence to policies aimed at curbing the exploitative tendencies of MNEs, as recommended by the OECD-G20 BEPS.

Although this study has made a laudable contribution to the FDI-tax revenue literature, further examination of the relationship could be explored by testing the differential effects of FDI on specific tax categories using disaggregated tax revenue data. However, while the identified gap will certainly enrich the extant literature, it does not by any means undermine the relevance of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See Makhoba and Zungu (Citation2022) and Sunde (Citation2017) on economic growth and export Makhoba and Kaseeram (Citation2019) on employment generation Stolzenburg et al. (Citation2020) on poverty and inequality.

References

- Ade, Michael, Jannie Rossouw, and Tendai Gwatidzo. 2018. “Determinants of Tax Revenue Performance in the Southern African Development Community (SADC).” Working Paper 762 Economic Research Southern Africa (ERSA).

- Agbeyegbe, Temisan D., Janet Stotsky, and Asegedech WoldeMariam. 2006. “Trade Liberalization, Exchange Rate Changes and Tax Revenue in sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of Asian Economics 17 (2): 261–284. doi:10.1016/j.asieco.2005.09.003.

- Aitken, Brian, and Ann E. Harrison. 1999. “Do Domestic Firms Benefit from Direct Foreign Investment? Evidence from Venezuela.” American Economic Review 89 (3): 605–618. doi:10.1257/aer.89.3.605

- Akinboade, O. A., and D. Makina. 2006. “Financial Sector Development in South Africa, 1970-2002.” Studies in Economics and Econometrics 30 (1): 101–128. doi:10.1080/10800379.2006.12106402.

- Amendolagine, Vito, Gianluigi De Pascale, and Nicola Faccilongo. 2021. “International Capital Mobility and Corporate Tax Revenues: How do Controlled Foreign Company Rules and Innovation Shape This Relationship?” Economic Modelling 101: 105543. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2021.105543.

- Arezki, Rabah, Alou Adesse Dama, and Gregoire Rota-Graziosi. 2021. “Revisiting the Relationship between Trade Liberalization and Taxation.” FERDI Working Paper P293.

- Arodoye, Nosakhare Liberty, and John N. Izevbigie. 2019. “Sectoral Composition and Tax Revenue Performance in ECOWAS Countries.” Oradea Journal of Business and Economics 4 (2): 45–55. doi:10.47535/1991ojbe077

- Arvin, Mak B., Rudra Pradhan, and Mahendhiran Nair. 2021. “Are There Links Between Institutional Quality, Government Expenditure, Tax Revenue and Economic Growth? Evidence from Low-Income and Lower Middle-Income Countries.” Economic Analysis and Policy 70: 468–489. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2021.03.011.

- Audu, Solomon Ibrahim. 2020. “Pattern of Spending and the Level of Tax Revenue in Nigeria.” International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Sciences 4 (9): 561–567.

- Balıkçıoğ, Eda, Başak Dalgıç, and Burcu Fazlıoğlu. 2016. “Does Foreign Capital Increase Tax Revenue: The Turkish Case.” International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 6 (2): 776–781.

- Bayar, Yilmaz, and Omer Faruk Ozturk. 2018. “Impact of Foreign Direct Investment Inflows on Tax Revenues in OECD Countries: A Panel Cointegration and Causality Analysis.” Theoretical and Applied Economics 25 (1): 31–40.

- Besley, Timothy, and Torsten Persson. 2014. “Why Do Developing Countries Tax so Little?” Journal of Economic Perspective 28 (4). doi:10.1257/jep.28.4.99.

- Binha, Oswell. 2021. “The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Tax Revenue in Zimbabwe (1980-2015).” International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 11 (1). doi:10.29322/IJSRP.11.01.2021.

- Camara, Abradamane. 2022. “The Effect of Foreign Direct Investment on Tax Revenue.” Comparative Economic Studies. doi:10.1057/s41294-022-00195-2.

- Chow, Gregory. 1960. “Test of Equality Between Sets of Coefficients in Two Linear Regressions.” Econometrica 28: 591–605.

- Engle, Robert F., and C. W. J. Granger. 1987. “Cointegration and Error Correction: Representation, Estimation and Testing.” Econometrics 55: 251–276. doi:10.2307/1913236.

- Etter-Phoya, Rachel, Markus Meinzer, and Shanna N. Lima. 2020. “Tax Base Erosion and Corporate Profit Shifting: Africa in International Comparative Perspective.” Journal of Financing for Development 1 (2): 68–107. http://www.uonjournals.uonbi.ac.ke/ojs/index.php/ffd/article/view/560.

- Faeth, Isabel. 2011. Foreign Direct Investment in Australia: Determinants and Consequences. Australia: Custom Book Center, Department of Economics, University of Melbourne.

- Gaspareniene, Ligita, Tomas Kliestik, Renata Sivickiene, Rita Remeikiene, and Martynas Endrijaitis. 2022. “Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Tax Revenue: The Case of the European Union.” Journal of Competitiveness 14 (1): 43–60. doi:10.7441/joc.2022.01.03.

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2017. “Impact of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Inflows on Non-Resource Tax and Corporate Tax Revenue.” Economics Bulletin 37 (4): 2890–2904.

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2019. “Financial Development and Tax Revenue in Developing Countries: Investigating the International Trade and Economic Growth Channels”. ZBW – Leibniz Information Centre for Economics, Kiel, Hamburg.

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2022. “Financial Development and Tax Revenue in Developing Countries: Investigating the International Trade Channel.” SN Business and Economics 2 (1). doi:10.1007/s43546-021-00176-0.

- Gupta, Abhijit Sen. 2007. “Determinants of Tax Revenue Efforts in Developing Countries.” Working Paper 07/184 IMF. doi:10.5089/9781451867480.001

- Ha, Nguyen Minh, Pham Tan Minh, and Quan Minh Quoc Binh. 2022. “The Determinants of Tax Revenue: A Study of Southeast Asia.” Cogent Economics and Finance 10 (1). doi:10.1080/23322039.2022.2026660.

- Haddad, Mona, and Ann Harrison. 1993. “Are There Positive Spillovers from Direct Foreign Investment? Evidence from Panel Data for Morocco.?” Journal of Development Economics 42: 51–74. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(93)90072-U.

- Hanrahan, David. 2021. “Digitalization as a Determinant of Tax Revenues in OECD Countries: A Static and Dynamic Panel Data Analysis.” Athens Journal of Business & Economic 7 (4): 321–348. doi:10.30958/ajbe.7-4-2.

- Harris, Richard, and Robert Sollis. 2003. Applied Time Series Modelling and Forecasting. West Sussex: Wiley.

- Heller, Peter. 1975. “A Model of Public Fiscal Behaviour in Developing Countries: Aid, Investment and Taxation.” The American Economic Review 65 (3): 429–445.

- IMF (International Monetary Fund Staff). 2016. “Financial Development in sub-Saharan Africa: Promoting Inclusive and Sustainable Growth.”.

- Jansky, Petr, and Miroslav Palansky. 2019. “Estimating the Scale of Profit Shifting and Tax Revenue Losses Related to Foreign Direct Investment.” International Tax and Public Finance. doi:10.1007/s10797-019-09547-8.

- Johansen, Soren. 1991. “Estimation and Hypothesis Testing of Cointegration Vectors in Gaussian Vector Autoregressive Model.” Econometrica 59: 1551–1580. doi:10.2307/2938278.

- Johnson, Peace Ngozi, and Cordelia Onyinyechi Omodero. 2021. “Governance Quality and Tax Revenue Mobilization in Nigeria.” Journal of Legal Studies 28: 1–41. doi:10.2478/jles-2021-0009.

- Khattry, Barsha, and J. Mohan Rao. 2002. “Fiscal Faux Pas?: An Analysis of the Revenue Implications of Trade Liberalization.” World Development 30: 1431–1444. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00043-8.

- Komlagan, Mawussé, and Nézan Okey. 2013. “Tax Revenue Effect of Foreign Direct Investment in West Africa.” African Journal of Economic and Sustainable Development 2 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1504/AJESD.2013.053052

- Laudage, Sabine. 2020. “Corporate Tax Revenue and Foreign Direct Investment: Potential Trade-Offs and How to Address Them.” German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS) Discussion Paper 17/2020. doi:10.23661/dp17.2020.

- Leuthold, Jane. 1991. “Tax Shares in Developing Economies: A Panel Study.” Journal of Development Economics 35 (1): 173–185. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(91)90072-4.

- Lewis, Christine, and Theresa Alton. 2015. “How can South Africa's Tax System Meet Revenue Raising Challenges?” Working Papers No. 1276. OECD Economics Department. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5jrp1g0xztbr-en.pdf?expires = 1665227964&id = id&accname = guest&checksum = 3D5AD00857D4919A77B76F8CF8D7C193.

- Mahmood, Haider, and A. R. Chaudhary. 2013. “Impact of FDI on Tax Revenue in Pakistan.” Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences 7 (1): 59–69.

- Makhoba, Bongumusa P., and Irrshad Kaseeram. 2019. “The Contribution of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to Domestic Employment Levels in South Africa: A Vector Autoregressive Approach.” Journal of Economics and Behavioural Studies 11 (1): 110–121. doi:10.22610/jebs.v11i1(J).2752

- Makhoba, Bongumusa P., and Lindokuhle Talent Zungu. 2022. “Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Growth in South Africa: Is There a Mutually Beneficial Relationship?” Journal of African Business 16 (4): 101–115. doi:10.31920/1750-4562/2021/v16n4a5.

- Makwe, Emmanuel Uzoma, and Akeeb Olusola Oladele. 2020. “Foreign Direct Investment and Revenue Generation in Nigeria.” International Journal of Development and Economic Sustainability 8 (2): 10–37. https://www.eajournals.org/wp-content/uploads/Foreign-Direct-Investment-and-Revenue-Generation-in-Nigeria-1970-2018.pdf.

- Manamba, Epaphras, and Lucas E. Kaaya. 2020. “Tax Revenue Effect of Sectoral Growth and Public Expenditure in Tanzania: An Application of Autoregressive Distributed Lag Model.” Romanian Economic and Business Review 15 (3): 81–120.

- National Treasury South Africa. 2022. Republic of South Africa 2022 Budget.” Accessed October 30, 2022. http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2022/review/FullBR.pdf.

- Nguyen, Huu T., and Manh Hung Nguyen and Aditya Goenka. 2013. “How Does FDI Affect Corporate Tax Revenue of the Host Country?” 13-03 (univ-evry.fr).

- OECD. 2015. Measuring and Monitoring BEPS, Action 11 - 2015 Final Report. Paris: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.” Accessed November 9, 2022. http://www.oecdilibrary.org/content/book/9789264241343-en.

- OECD. 2017. OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. Accessed November 9, 2022. doi:10.1787/tpg-2017-en.

- OECD. 2020, April 28. “Policy Response to Coronavirus. Developing Countries and Development Cooperation: What is at Stakes?” Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/developing-countries-and-development-co-operation-what-is-at-stake-50e97915/.

- Ofori, Isaac K., Pamela E. Ofori, and Simplice Asongu. 2021. “Towards Efforts to Enhance Tax Revenue Mobilization in Africa: Exploring the Interaction Between Industrialization and Digital Infrastructure.” Telematics and Informatics 72: 101857. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2022.101857.

- Olaniyan, Niyi O, Olubunmi O. Efuntade, Ajani O. Efuntade, and Taiwo C. Dada. 2020. “Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Revenue Generation in Nigeria: Mediating on the Role of Company Tax.” Acta Universitatis Danubius: OEconomica 16 (6): 204–223.

- Olayeni, Olaolu Richard, Olufunmilayo Olayemi Jemiluyi, Kumar Tiwari Aviral, and Hammoudeh Shawkat. 2022. “The Threshold Role of FDI in the Energy-Growth Nexus: An Endogenous Growth Perspective.” The Energy Journal 44: 5. doi:10.5547/01956574.44.4.oric.

- Oz-Yalaman, Gamze. 2019. “Financial Inclusion and Tax Revenue.” Central Bank Review 19 (3): 107–113. doi:10.1016/j.cbrev.2019.08.004.

- Perron, Pierre. 1989. “The Great Crash, the Oil Price Shock and the Unit Root Hypothesis.” Econometrica 57: 1361–401.

- Panapoulou, Ekaterini, and Nikitas Pittis. 2004. “A Comparison of Autoregressive Distributed Lag and Dynamic OLS Cointegration Estimators in the Case of a Serially Correlated Cointegration Error.” The Econometric Journal 7 (2): 585–617. doi:10.1111/j.1368-423X.2004.00145.x.

- Pesaran, M. Hashem, and Yongcheol Shin. 1998. “An Autoregressive Distributed-Lag Modelling Approach to Cointegration Analysis.” In Econometrics and Economic Theory in the 20th Century. The Ragnar Frisch Centennial Symposium, Chap. 11, edited by S. Strøm, 371–413. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pesaran, M. Hashem, Yongcheol Shin, and Richard J. Smith. 2001. “Bounds Testing Approaches to the Analysis of Level Relationships.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 16 (3): 289–326. doi:10.1002/jae.616

- Pratomo, Arif Widya. 2020. “The Effect of Foreign Direct Investment on Tax Revenue in Developing Countries.” Jurnal BPPK: Badan Pendidikan Dan Pelatihan Keuangan 13 (1): 83–95. doi:10.48108/jurnalbppk.v13i1.484.

- Reynolds, Hailey, and Ludvig Wier. 2016. “Estimating Profit Shifting in South Africa Using Firm-Level Tax Returns.” UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2016/128. https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/wp2016-128.pdf.

- Shrestha, Min B., and Guna R. Bhatta. 2018. “Selecting Appropriate Methodological Framework for Time Series Data Analysis.” The Journal of Finance and Data Sciences 4 (2): 79–89. doi:10.1016/j.jfds.2017.11.001.

- Shrestha, Santosh, Koji Kotani, and Makoto Kakinaka. 2021. “The Relationship Between Trade Openness and Government Resource Revenue in Resource-Dependent Countries.” Resources Policy 74. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102332.

- Stolzenburg, Victor, Marianne Matthee, Caro Janse van Rensburg, and Carli Bezuidenhout. 2020. “Foreign Direct Investment and Gender Inequality: Evidence from South Africa.” Transnational Corporation Journal 27: 3. doi:10.18356/b025294b-en

- Summers, Lawrence. 1981. “Taxation and Corporate Investment: A q-Theory Approach.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 68–140.

- Sunde, Tafirenyika. 2017. “Foreign Direct Investment, Export & Economic Growth: ARDL and Casualty Analysis for South Africa.” Research in International Business and Finance 41: 434–444. doi:10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.04.035

- Tabasam, Farhana. 2014. “Impact of Foreign Capital Inflows on Tax Collection: A Case Study of Pakistan.” Issues (national Council of State Boards of Nursing (u S )) 2 (2): 202–212.

- UNCTAD. 2022, June 9. Press Release: Global Foreign Direct Investment Recovered to Pre-Pandemic Levels in 2021 but Uncertainty Looms in 2022.” Accessed November 9, 2022. https://unctad.org/press-material/global-foreign-direct-investment-recovered-pre-pandemic-levels-2021-uncertainty.

- United Nations. 2022. “Sustainable Development Report: A Global Plan to Finance the Sustainable Development Goals part 1.” Accessed November 9, 2022. https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/chapters/part-1-a-global-plan-to-finance-the-sdgs.

- Vogelsang, J. Timothy, and Pierre Perron. 1998. “Additional Tests for a Unit Root Allowing the Possibility of Breaks in the Trend Function.“ International Economic Review 39: 1073–100.

- World Bank. 2018, September 21. “Press Release: South Africa’s Efforts to Improve Financial Stability and Inclusion Boosted.” Accessed November 9, 2022. South Africa’s Efforts to Improve Financial Stability and Inclusion Boosted (worldbank.org).

- World Bank. 2021a, February 1. “Increasing Tax Revenue in Developing Countries.” Accessed October 30, 2022. https://blogs.worldbank.org/impactevaluations/increasing-tax-revenue-developing-countries.

- World Bank. 2021b, February 26. “Empowering the Poorest Countries Towards a Resilient Recovery.” Accessed October 30, 2022. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/immersive-story/2021/02/26/empowering-the-poorest-countries-towards-a-resilient-recovery.

- World Bank. 2022. “World Development Indicators." Accessed 2 November 2022. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

- Zivot, Eric, and Donald W. K. Andrews. 1992. “Further Evidence on the Great Crash, the Oil Price Shock and the Unit Root Hypothesis.” Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 10: 251–70.