ABSTRACT

Collaboration is now a common way to make public policy and run government, and governments often make it a requirement. This article is a qualitative study of how people work together when they must. It is based on real-world research on a stunting intervention in three regencies in Indonesia’s West Java Province. The study collected data through in-person interviews, documentation reviews, and observation. The findings revealed that a mandated collaboration had been implemented, but with limited participation from nonstate actors. This situation occurred because government agencies remained the primary owners of the process while nonstate actors were not fully engaged. As a result, the collaboration in stunting interventions became merely a government program rather than a collectively owned process. To address this issue, the study proposes a new framework of mandated collaboration that is more inclusive, collective, and participatory, using the Hansel and Gash model of collaborative governance. Furthermore, the study recommends empowering the community to make the collaborative process more equitable in decision-making and encouraging non-state actors to take ownership of collaborative governance.

1. Introduction

As governments become more aware of the limitations of classic top-down approaches, they are developing a greater appreciation for the importance of collaborative governance in policymaking and implementation (Douglas et al. Citation2020). Collaborative governance is a process of sharing decision-making power with stakeholders to govern solutions to public problems (Purdy Citation2012). At the core of this approach is collaboration, which is a process of interaction among actors to create structures that govern their interaction and decision-making on the issue that brought them together (Thomson, Perry, and Miller Citation2007). Through collaboration, actors may voluntarily work together to achieve common or private goals, thereby enriching collaborative governance with aspirations, knowledge, and resources (Castañer and Oliveira Citation2020). Although successful collaboration is difficult to achieve (Marek, Brock, and Savla Citation2015), working collaboratively is essential for tackling complex social problems and addressing social needs. Consequently, collaborative governance is widely recognized as a critical aspect of managing public issues.

Collaboration is hard to do well because it is a complicated process that often ends in failure (Marek, Brock, and Savla Citation2015). For collaboration to work, the people involved need to agree on a broad vision and common goals, set up cross-sectoral structures, make decisions based on facts, and hold each other accountable (Connors-Tadros Citation2019). Also, actors need to understand the different structures and values of organizations, build good relationships with other people, and learn how to be good leaders (DeHoog Citation2015). Despite these efforts, the success of collaboration may be uncertain. Additionally, collaboration initiatives might not spontaneously arise from interactions between actors but rather be required by higher authorities. Policymakers start a policy-mandated collaboration by defining the collaboration’s structure, goal, task, membership, and formal procedure (Krogh Citation2022). When collaboration is mandated, actors who previously had no intention of working together are instructed to do so. In this context, collaboration may be involuntary, and as a result, building blocks such as norms, trust, values, vision, goals, and structure may be compromised (Popp and Casebeer Citation2015). Collaboration may not fully function in achieving mutual goals, but instead become a task and an accountability to those receiving the mandate. Less is known, though, about how collaboration starts and grows from a mandate to a full-fledged partnership with shared power and responsibilities.

The goal of this article is to look at how a policy-mandated collaboration is set up and turned into local collaborative governance. It uses the Eight Convergence Actions framework to look at the situation of cross-sectoral collaboration in Indonesia’s West Java Province to help people who are short for their age. The research question guiding this article is: What are the factors that influence the implementation and transformation of mandated collaboration into collaborative governance? To answer this question, the article assesses the quality of collaborative stunting interventions at the local level by using the concepts of collaborative governance proposed by Ansell and Gash (Citation2007). Based on empirical data and literature, the article proposes a modified conceptual model for building collaborative governance in a mandated setting. This model aims to offer insights to collaborative governance practitioners and stunting intervention practitioners on how to shift from a policy-mandated collaboration to one where participating actors take ownership of the process.

2. Literature review

2.1. Collaboration and collaborative governance (CG)

Governance actors can engage in different forms of interaction, such as collaboration and coordination. Collaboration involves the participation of two or more actors in public policy and management. On the other hand, coordination is a top-down management process that helps prevent duplication and maintain vertical management’s tidyness, as pointed out by Peters (Citation2018). According to Martin, Nolte, and Vitolo (Citation2016) and Spann (Citation1979), coordination is a crucial part of collaboration because it ensures that activities across units or departments within one or more organizations are in line with one another, resulting in coherence and consistency. Therefore, coordination is an interaction between actors at different levels of authority that serves to ensure coherence and consistency in governance.

Coordination is an interaction that takes place among actors of different levels of authority, either within an organization or a system. Coordination, then, involves people in an organization with different roles and responsibilities, such as managers, supervisors, staff, and others. Coordination is important because it helps make sure that organizational goals are met in an effective and efficient way. Coordination refers to organizing and coordinating the activities and tasks carried out by various organizational components. This makes sure that all of the parts are working together in the same way. So, in order for tasks and activities to be done well, it’s important for people with different levels of power to work together and help each other. In short, coordination requires people with different levels of power to work together to make sure that tasks and activities are done well.

In practice, coordination can be performed vertically or horizontally. Vertical coordination is performed by leaders or managers to organize tasks and activities undertaken by subordinates or team members, whereas horizontal coordination is carried out by team members working in different parts of the organization. However, both vertical and horizontal coordination require interactions among actors with different levels of authority to achieve organizational goals. Collaboration, on the other hand, involves actors negotiating and creating a structure and rules based on shared norms and mutually beneficial interactions that bind them together, as highlighted by Thomson, Perry, and Miller (Citation2007, 25). In summary, while coordination involves top-down management and horizontal interactions among actors with different levels of authority, collaboration involves negotiation and the establishment of structures and rules based on shared norms and mutually beneficial interactions.

Collaboration is a process in which people work together to find a solution to a problem that affects them all. During this process, the actors try to come up with a structure and set of rules that hold them together. They do this by referring to shared norms or principles that everyone agrees on and by working together in ways that are good for everyone. Collaboration is done to reach common goals and improve relationships between actors. This, in turn, makes it easier to come to agreements that are good for both sides. Collaboration involves a negotiation process that takes into account everyone’s point of view and leads to agreements that are fair and good for everyone. Collaboration is a way of negotiating that involves making a structure and rules based on shared norms and interactions that are good for both sides. This leads to fair agreements that are good for everyone.

Collaboration means that two or more organizations work together over a long period of time, which can lead to high levels of interdependence and risk (Keast and Mandell Citation2014). The goals of collaboration are complicated because they are based on shared interests and require tasks that depend on each other and must be done together (Keast, Brown, and Mandell Citation2007). In other words, collaboration can be viewed as a process of long-term interactions that are governed by shared norms, interests, and mutual benefits. This process makes rules and structures that help tasks that are related to each other work together to reach complex goals that bring the actors together.

Coordination and collaboration are two distinct but related organizational management concepts. Coordination focuses primarily on organizing and synchronizing tasks or activities to promote harmony and continuity between various organizational components. Collaboration, on the other hand, emphasizes active cooperation between team members to achieve common goals by mutually supporting and enhancing the tasks of the organization. Collaboration entails active cooperation among individuals or teams to achieve shared goals, whereas coordination focuses more on task organization.

The term collaborative governance (CG) is commonly used to describe activities related to public policy that take place beyond governmental bureaucracies in the context of public administration (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015). Collaborative governance can be defined as a formal, deliberate, and consensus-oriented governing arrangement that enables public agencies and non-state stakeholders to engage in collective decision-making to make or implement public policy (Ansell and Gash Citation2007). Additionally, collaborative processes and structures are required to ‘carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished’ (Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh Citation2013, 2). This approach involves actors who cross the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and public, private, and civic spheres, including public participation and civic engagement (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015). As power is shared in decision-making, collaborative governance is the process of creating recommendations for effective and lasting solutions to public problems (Purdy Citation2012). Collaborative governance allows public institutions to work with non-state actors to solve complex social problems, which reflects a bottom-up approach and includes actors from the nonprofit sector. As the actors work together to solve these problems, the distinctions between the public, private, and nonprofit sectors become less rigid (Kettl Citation2006). In summary, collaborative governance can be defined as a set of deliberate and consensus-oriented activities related to public policymaking and management that require state and non-state actors across boundaries, levels, and spheres to engage and share power in making decisions to solve complex public problems more effectively.

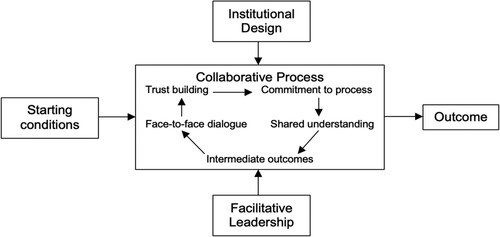

Collaboration and collaborative governance both emphasize the significance of shared norms and interests. This indicates that a horizontal approach to governance is superior to a vertical approach. This means that actors from different levels and sectors collaborate as equals to make decisions and solve problems, as opposed to taking a hierarchical approach in which one actor has more control over the others. Horizontal governance refers to processes of steering and coordination between actors with varying levels of authority, whereas horizontal governance denotes the blurring of the distinction between policymakers and policy objectives (Torfing et al. Citation2012). The terms ‘shared norms and interests’ and ‘consensus-oriented,’ as well as the participation of state and non-state actors at various levels, highlight collaboration and CG as more horizontal or diagonal governance. Additionally, the CG model that Ansell and Gash (Citation2007) developed () supports this conceptualization. The model identifies four significant variables that influence CG: initial conditions, institutional design, facilitative leadership, a collaborative process, and outcomes. When interactions are horizontal or diagonal, it is more likely that a collaborative process involving trust building, process commitment, and shared comprehension will occur. A case of strong vertical interaction, such as a mandated collaboration, has not received additional consideration within the model. When a mandate becomes part of the initial conditions and contributes to the formation of institutional design, the CG variables differ from those of a more horizontal CG in which participation is voluntary, which is the main point of this article.

Figure 1. Collaborative governance model by Ansell and Gash (Citation2007, 550).

The Collaborative Governance Model by Ansell and Gash (Citation2007, 550) is a framework that shows how collaborative governance can work in an organization or system, with a focus on how important fair, inclusive, and long-lasting collaborative governance is to achieving overall goals. Because the model is flexible, it can be used in many different settings, including the public, private, and nonprofit sectors.

2.2. Mandated collaboration and interactive governance

According to Ansell and Gash (Citation2007), public institutions frequently take the initiative for CG, which may take the form of a public policy that requires implementation by those who are required to do so. In some cases, CG is established under a mandate, commonly referred to as policy-mandated networks, particularly in local governments that receive a mandate from the central government as part of their responsibilities. Such networks are initiated by the government through a legal statute or decree that specifies the key features of the collaboration, including procedures and membership, as pointed out by Krogh (Citation2022). Typically, one or more public agencies are appointed to manage the networks under the mandate (Provan and Kenis Citation2007). Policymakers use mandated networks for various reasons, such as building community social capital, promoting information sharing across boundaries, solving complex problems, responding to natural disasters, or integrating public service delivery, as identified by Milward and Provan (Citation2006). However, in a mandated setting, some elements of successful collaboration, such as trust, shared goals, vision, and risk sharing, may be compromised, according to Popp and Casebeer (Citation2015), since the features of mandated collaboration may not always fit real-life conditions. Additionally, the mandate’s specifications may vary from case to case, influencing the formation of networks and the negotiation, commitment, execution, and activities, as noted by Segato and Raab (Citation2019).

Mandated collaboration relies on three mechanisms: bureaucratic, market-based, and clan-based, as outlined by Rodríguez et al. (Citation2007). Bureaucratic mechanisms impose constraints and rules on governance, while market-based mechanisms rely on incentives to reorient the interests of individuals and groups within an organization or network. The clan-based mechanism is the ideal form of collaboration, where interactions result in shared values and beliefs. However, when mandates come from higher government authorities, collaboration tends to adopt a bureaucratic mechanism, which leads to vertical interaction. This approach is counterproductive to the concept of CG, which emphasizes the need for state and non-state actors with horizontal relationships to work together to achieve mutual goals. To achieve its goals, mandated CG requires both vertical and horizontal interactions, forming interactive governance similar to the CG process where actors with diverging interests interact to achieve common goals, as identified by Torfing et al. (Citation2012). When governance accommodates both vertical and horizontal interactions, coordination, and cooperation lead to meaningful CG. Thus, transforming a mandate into such a CG is the central focus of this article.

2.3. The context of stunting intervention in Indonesia

Stunting is when a child’s growth and development are slowed down. This can be caused by things like not getting enough to eat, getting sick a lot, or not getting enough social stimulation (WHO Citation2015). A child is considered stunted if their height for age falls more than two standard deviations below the WHO Child Growth Standards median (WHO Citation2015). The condition has multiple causes, including illness, malnutrition, and the mother’s nutritional status during pregnancy. Additionally, Torlesse et al. (Citation2016) found that drinking water and sanitation also contribute to stunting in Indonesia. Stunting’s impact on an individual’s life is also multifaceted. According to Aguayo and Menon (Citation2016), the causes of stunting in South Asia include the lack of nutrition in the first two years of life, the mother’s inadequate nutrition during pregnancy, and poor household and sanitation practices. Children who suffer from stunting may have poor cognitive performance, face challenges with school admission, and have an increased risk of nutrition-related chronic diseases. As adults, they may experience reduced productivity and face difficulties in securing employment (Victora et al. Citation2008; WHO Citation2015). Given the severe and long-term consequences of stunting, addressing the issue has become a priority in development. Stunting is part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with Goal 2 focusing on ‘zero hunger.’

Stunting interventions become a development priority in countries like Indonesia with a high prevalence of stunting, which was 27.7% in 2019, down from 30.8% the previous year (Badan Pusat Statistik Citation2020b). These numbers are collected on a national level, and they vary from province to province. In some provinces, the number of children who are too short for their age is higher than in others. To address the issue, the Indonesian central government has implemented two types of interventions: specific and sensitive. Some interventions directly deal with the causes of stunting, such as lack of nutrition, lack of food, and lack of medicine. These interventions are closely linked to health treatments. On the other hand, sensitive interventions are broader and aim to (1) improve access to food and health services, (2) raise awareness, commitment, and practice of nutritional care for mothers and children, and (3) improve the quality of and access to clean water and sanitation. These interventions require the involvement not only of the Ministry of Health but also of other government bodies and stakeholders. They are holistic and convergent, involve cross-sectoral and multi-level collaboration, and encourage healthy behavior, leading to a decrease in stunting prevalence. In its National Medium-Term Development Plan 2020–2024, the Indonesian central government has set a target to reduce stunting prevalence to 14% in 2024, demonstrating its commitment to address the issue through targeted interventions.

Indonesia’s central government has released the Eight Convergence Actions (ECA) to speed up the reduction of stunting and reach the goal of reducing the number of people who are stunted to 14% by 2024. The ECA emphasizes cross-sectoral and multi-level collaboration to intervene against stunting. The mandate receivers of ECA are two levels of local government, with the provincial government responsible for monitoring the process and progress of stunting interventions and the city/regency governments responsible for implementing the actions in their respective jurisdictions. For each convergence action designed by the central government, local government bodies are involved, and their respective responsibilities are stipulated, which means that the recipients of the stunting convergence mandate are specified for each action. Moreover, in each city or region, there is a village administration that works closely with local communities, making the village-level administration an integral part of the actions. Additionally, there are stunting cadres who are selected by the local communities to bridge the gap between the locals and the governments during the collaborative process of stunting interventions.

This study is focused on the context of West Java province, specifically on three regencies: Garut, Sukabumi, and Kuningan. As one of the provinces in Indonesia with a high prevalence of stunting (31.1 percent in 2018 (BPS Citationn.d.)), decreasing stunting cases in this province is a priority for the central government’s stunting interventions. Additionally, West Java has the largest population in Indonesia, with 49.6 million people out of the 269.6 million Indonesian population residing in the province (Badan Pusat Statistik Citation2020a). This makes decreasing stunting cases in West Java significant compared to the national average. The National Basic Health Survey (the Riskedas) 2018 reports that the prevalence of stunting in Garut, Sukabumi, and Kuningan is 27.3, 21.9, and 18.6 percent, respectively (Kementerian Kesehatan RI Citation2018). However, the three regencies have different results in implementing the ECA in 2020, with Garut, Sukabumi, and Kuningan ranked 8th, 10th, and 16th, respectively, in West Java according to the Ministry of Home Affairs of Indonesia (Citation2020).

3. Method

This article looks at three cases to show how convergence actions are ordered and carried out at the local level. To come up with a model for mandated CG, the article looks at how collaborative efforts to stop stunting are going in the three regencies. The qualitative research method is used to get a full picture of complicated processes. First, the content of official documents and websites are analyzed, and then interviews are done. Policies, technical instructions, and reports were among the things that were chosen because they were related to the research question and the situation. Through the content analysis, we could learn about the setting and institutional design of the collaborative interventions for stunting, as well as which parts of collaboration were required, and which were not. This information from the content analysis is very important for understanding what the mandate is, and it goes well with the information gathered from the in-person interviews.

In this research, semi-structured interviews were used as the primary data collection method. The interviews followed a guide that was created to explore the collaboration processes of the convergence actions mandated by the central government. The interview guide included several key areas for exploration, including identifying the actors and their roles in convergence action, examining the institutional design and starting conditions where collaboration takes place to understand whether the conditions are supportive for collaboration or not, assessing the local level leadership that may encourage or discourage the collaborative processes, understanding the processes or mechanisms of the collaboration itself, examining the accountability mechanism of the convergence actions, discussing the challenges in implementing the collaborative processes, and identifying any best practices or lessons learned that need to be maintained.

To collect data for this research, we conducted a total of 23 interviews with various actors, including those from the provincial government, government agencies in three regions, communities, and non-governmental partners. Of these interviews, six were conducted in groups consisting of up to 10 community members. These group interviews were conducted after the individual ones and were used to cross-examine questions related to collective activities regarding stunting intervention in their community. In addition to interviews, we also collected data through observation, particularly to understand the dialogue between actors. By using interviews, documentation studies, and observation, we were able to collect and code information about the implementation of convergence actions, how the collaboration processes were conducted, and what challenges and best practices appeared. Using this information, we analyzed the data to gain a better understanding of the process of CG implementation and proposed a model of mandated CG accordingly.

4. Result and discussion

4.1. Implementation of convergence actions

West Java is a province in Indonesia that has been told to carry out convergence actions. A content analysis shows how this mandate is set up institutionally. The mandate includes eight convergence actions for stunting interventions in Indonesia, each equipped with specific goals, a scope, persons or institutions in charge, a schedule, an output, and implementation steps. These actions are carried out consecutively, starting with situation analysis and program planning in January and February (Actions 1 and 2) and ending with the annual performance review in December (Action 8). Together, these eight actions form a complete framework that establishes the ‘rule of the game’ for stunting interventions at the local level, leaving limited room for negotiation or changes by local governments and actors. However, the participation of actors in convergence actions is left open for local governments to decide, and they have the freedom to invite state or non-state actors to participate, in addition to the local agencies appointed as the coordinator(s) of each action.

illustrates the roles of the five types of stakeholders in penta-helix collaboration, which is commonly found in West Java’s stunting interventions. These stakeholders include state agencies, private businesses, academia, local communities, and mass media. Each stakeholder has a distinct role to play in the convergence actions, as outlined in .

Table 1. The role of penta-helix stakeholders in the ECA implementation.

Even though all of the stakeholders listed in Table are involved, non-state actors are not as involved in bringing about convergence in the three regencies of West Java as government agencies are. Although a commitment agreement is signed after the official stunting forum (Action 3) in all three regencies, only one has clearly defined roles and responsibilities for each participating actor. In contrast, the commitments in the other two regencies are more general and cannot be used to hold individual actors accountable by the end of the convergence cycle in December. This lack of accountability contributes to difficulties in keeping actors fully engaged throughout the process. While collaboration is mandated, the lack of real responsibility makes it challenging to engage actors directly, resulting in government bodies playing a more significant role in convergence actions than non-state actors. Government agencies receive the mandate and budget allocation to support implementation, giving them more power than non-state actors, who only have resources and discursive legitimacy, but not authority. Authority over convergence actions remains in the hands of the state, and non-state actors only have decision-making and implementation authority at the program level. This difference in power sources is related to how the rules and goals have been set by the government.

The power imbalance between actors in convergence actions affects the nature of their interactions. While formal and informal dialogues among actors occur as early as during situation analysis (Action 1) and program planning (Action 2), more intensive dialogues take place during the stunting forum (Action 3). Although the institutional design of the ECA allows actors to hold dialogues, the implementation of the ECA in West Java is still marked by coordination among regency government bodies, with monitoring and supervision from the provincial government. This power imbalance makes it difficult to achieve more meaningful collaboration where actors are more equal. To address this issue, training, especially for the Human Development Cadre (Action 5), becomes critical to the success of ECA implementation at the local level. The Regency Health Agency is responsible for providing the training, which includes educating the cadres about how the ECA works and their roles in collaboration. Additionally, the Agency for Community and Village Empowerment facilitates village governments in using their funds to support community development and stunting interventions, which are incorporated into broader community and village empowerment efforts. Policymaking (Action 4) makes it possible for village governments to use their allocated funds for ECA-related activities.

Actions 6, 7, and 8 are important parts of the ECA’s accountability system because they deal with managing data, measuring it, making it public, and reviewing the ECA. However, these activities primarily reflect vertical accountability to the central government, which monitors stunting rates across all regions to reduce the national prevalence. In turn, this narrow focus on meeting the central government’s expectations often detracts from the broader goals of reducing stunting prevalence and increasing public health awareness. Consequently, actors in West Java tend to overlook the common goals that are not explicitly outlined in the ECA, leading to a more bureaucratic approach to collaboration that emphasizes technical process over shared objectives.

4.2. Collaborative governance in stunting interventions

Through the lens of collaborative governance (CG), we can see how collaboration is put into place in the required setting. When it comes to convergence actions in West Java, the focus is on figuring out how well CG has been put into place so that problems can be fixed. Ansell and Gash (Citation2007) say that the most important parts of collaborative governance (CG) are institutional design, starting conditions, facilitative leadership, collaborative processes, and outcomes. Accountability is also an important part of CG. This means keeping track of and sharing information with different stakeholders (Douglas et al. Citation2020, 498). While it is ideal for each element to function well and promote collaboration, the reality is often different. Therefore, an analysis of the quality of CG in convergence actions is necessary to identify areas for improvement.

In West Java, convergence actions are designed and ordered by institutions. This means that institutional design is an important part of the starting conditions for collaborative governance (CG). The mandate tells the convergence actions how to work, but there are also other things that affect the starting conditions in West Java. For example, the fact that government agencies, private businesses, and local communities already work together helps CG a lot. On the other hand, CG can benefit from a lack of pre-existing conflict, while its presence may make it less likely to happen in the province. Local governments also carry out convergence actions because they are the ones who get the orders from the central government and oversee driving and running the CG. As a form of social responsibility, private businesses take part in CG, while village governments and administrators work to solve social problems in their area. Local communities are involved because stunting is an issue that matters to them, and some community members become human development cadres driven by social awareness, although the financial incentives for them are minimal. The precise amount depends on their village policy. With these starting conditions, convergence actions are feasible in West Java.

The collaborative process is one of the most important parts of collaborative governance (CG), which is affected by the starting conditions, the design of the institutions, and the leadership at the local level. The starting conditions make it possible for people to work together, and the design of the institutions makes it possible for people to talk face-to-face, especially through Action 3, which is the Stunting Forum. The Stunting Forum is a formal meeting where all parties are invited to talk about the yearly programs. Prior to the forum, informal meetings are held to brainstorm and prepare proposals. Through these interactions, stakeholders share their views, ideas, and contributions, which contributes to the trust-building process. Ultimately, the stakeholders design and agree on the programs or activities to intervene in stunting, which is documented in a public commitment agreement that is signed by all parties involved. Subsequently, the responsible parties implement the designed activities according to the agreement. If the agreement does not specify who is responsible for carrying out the activities, a government regulation is issued at the regency level.

Action 4, which is about making local policies, not only sets rules for convergence actions at the local level, but it also shows how the executive and legislative bodies in the regency are run. The regents and legislative body oversee making rules that tell village administrators what they can and can’t do when it comes to activities related to stunting, budget allocation, planning and implementing programs at the village level, training cadre, and getting people in the village involved. The regulation stresses how important it is for the village government to drive stunting interventions at the local level. It also gives a legal basis for how village funds can be managed and used for stunting interventions. Also, the regents and legislative bodies’ jobs go beyond making rules. They are also expected to give money to and support programs that fight stunting. In West Java, this is called ‘facilitating leadership.’ As a result, the regent, vice-regent, and legislative members are all involved in convergence actions and other activities that encourage healthy living.

Accountability is a key part of how convergence actions are set up institutionally, and this accountability is mostly aimed at local governments. Local governments report and monitor the implementation of convergence actions through a centrally developed website or dashboard, and stunting cases and measurements are included in this reporting process. Performance review (Action 8) is also used to hold local governments accountable, as they are evaluated and scored on their convergence actions at the end of each year by an evaluation team consisting of civil servants from the central and provincial levels. While non-state actors are not directly held accountable for the convergence actions, local governments have used their authority through the Office of Community and Rural Empowerment (OCRE) to encourage community participation in stunting interventions as an informal requirement for village fund disbursement. However, local governments do not have the same authority to impose such requirements on private business owners, academia, and mass media, so their participation in convergence actions is voluntary or the result of negotiation and partnerships.

Implementing convergence actions is a form of collaborative governance that involves state and non-state actors and has a mandated institutional design, enabling starting conditions, supportive leadership, and a clear accountability system. However, the extent of each element is constrained by three factors. Firstly, the participation of non-state actors is voluntary or by invitation, leading to the perception that convergence actions are government programs and non-state actors’ engagement is not active. Secondly, non-state actors have limited knowledge about how convergence actions work, hindering their ability to take ownership of the collaboration easily. Thirdly, local communities lack program management skills, resulting in poverty in villages where stunting cases are found. These challenges require improvements in the implementation of convergence actions to build collaborative governance in a mandated setting that translates the government’s programs into the language of people at the grassroots level.

4.3. A pathway towards collaborative governance at local level

West Java’s stunting intervention lacks collaborative governance, as it operates primarily through mandates rather than active engagement processes. Despite these limitations, the province’s CG demonstrates growth that can serve as a model for implementing CG in a mandated setting. First, the stunting agenda has been integrated into community empowerment programs with the assistance of the OCRE and village assistants from the Ministry of Villages, Development of Deprived Regions, and Transmigration (MVDDRT). This is essential because building skills and knowledge in local communities requires more processes than those provided by Action 5 (Training of Cadre). Second, one West Java regency has established a cadre organization, a non-profit community organization comprised of human development cadres. Through their interactions, the organization disseminates information and shares knowledge, enabling cadres to hone their skills and increase their understanding of stunting interventions. It establishes a peer-to-peer learning system in which members learn about stunting and program management from one another and collectively enhance their skills and knowledge.

In addition to the lessons learned from West Java, there is a proposal that we believe is essential for transforming a network mandated by policy into a more meaningful form of collaborative governance. Policy-mandated networks require a ‘network manager’ who acts as a liaison between the mandate from higher authorities and the local implementation. The network manager ‘mediates the impact of formally designed rules on the collaborative process, thereby altering or reproducing the institutional logics embedded in institutional design’ (Krogh Citation2022, 6). They are responsible for inviting participants, conducting facilitation, developing a strategic vision, and even employing various formats to achieve the objectives (Koppenjan and Klijn Citation2004). In convergence actions, the Local Development Planning Agency (LDPA) and the Office of Community and Regional Empowerment (OCRE) collaborate. The former has the authority to coordinate government agencies and form partnerships with business owners, while the latter has the authority to assist with and oversee community development. LDPA can serve as a network manager with an emphasis on public-private collaboration, whereas OCRE is responsible for encouraging communities to engage in convergence actions.

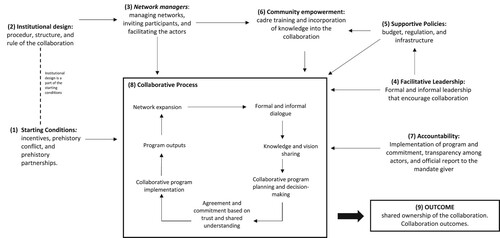

A model of collaborative governance was made by Ansell and Gash (Citation2007). It has seven parts. In this article, we use their model of collaborative governance, with changes based on the strategy for implementation and improvement in convergence actions, as shown in .

The model of collaborative governance presented in is based on the model developed by Ansell and Gash (Citation2007), with additional elements that reflect the mandate context in West Java. According to the convergence action framework, institutional design is a fundamental aspect of the initial conditions. Although it may be possible to modify the institutional design in the long run, the implementation of convergence actions in West Java over the past two years has not altered the collaboration’s fundamental building blocks. The framework of convergence actions leaves network managers with limited managerial leeway to modify the design. However, the degree of maneuvering authority does not dictate the network managers’ actual manouvering (Krogh Citation2022). Applying this logic to convergence actions, the institutional design that restricts structure and procedure changes does not determine the failure of collaborative governance, despite having an impact on the incentives that motivate non-state actors to participate. Despite their limited maneuverability, network administrators have the authority to select and invite participants. Consequently, their roles are crucial in determining whether the mandate results in meaningful collaborative governance at the local level. The convergence actions framework makes it possible to promote collaborative governance at the local level, and the key to its success in practice is how local governments manage the networks. This includes how they negotiate with non-state actors and encourage their full participation in processes. This requires the LDPA and OCRE to assume the role of network administrators. Network managers are crucial for communicating convergence actions to participating actors, inviting non-state actors, forming partnerships, and assisting the local community in gaining a deeper understanding of stunting and project management.

Figure 2. A model of collaborative governance in a policy-mandated setting. Source: own elaboration.

As convergence actions concentrate primarily on village-level interventions, it is imperative that local communities participate in the processes. The training of the Human Development Cadre (Action 5) cannot automatically increase the community’s awareness of stunting and the programs designed to combat it. Therefore, awareness-raising and knowledge expansion should be integral components of community empowerment.

To empower local communities, everyone involved needs to work together over the long term. This includes the government (through the OCRA), which manages the programs; universities, which design and offer training; and non-profit advocacy programs. Community empowerment needs help from the federal and local governments in the form of budget allocation, development policies, and infrastructure. Budget allocation, development policies, and infrastructure are also needed. These aids are viable when the central and local administrations cooperate. This indicates that formal executive leaders and legislative bodies issue policies that serve as the legal basis for executive agencies’ actions. Formal leadership is also essential for fostering collaboration, as leaders are able to implement supportive policies. On the other hand, informal leaders play a larger role at the village level. Convergence actions must invite influential informal leaders to make it easier for network managers to involve community members in the collaboration.

The collaborative process begins after local governments receive the mandate to implement convergence actions. Recipients of mandates have the option to expand networks by inviting additional actors to participate. Local governments must utilize their authority, influence, and previous partnerships to complete this process. State and non-state actors initiate a formal and informal dialogue regarding each actor’s commitment and contribution. These interactions are also a process of establishing trust and exchanging information. Actors are only fully engaged when they are treated as equal partners, so that decision-making and program planning are carried out collaboratively. Creating ownership for non-state actors and shifting the mandate to collaborative governance with shared ownership by multiple stakeholders requires full participation. This is a difficult task, not only because it requires non-state actors to be more empowered to express their opinions during dialogue, but also because institutional design may need to be modified to accommodate non-state actor’s interests. This brings us back to the significance of network managers, who must also understand the interests of non-state actors and the incentives that motivate them to participate fully in the collaboration. After two years of implementation, the convergence actions in West Java have not reached this level of collaboration, indicating that network managers and other government agencies must work harder to invite non-state actors to participate more actively. In order to create engagement, an institutional design adjustment may be necessary.

When collaborative governance is made up of people who have about the same amount of power in making decisions and planning programs, accountability in CG goes beyond what is required by law. Accountability is not only a tool for the mandate giver to monitor and evaluate the implementation but also for transparency among the participating actors themselves. When the actors take ownership of the collaborative process, accountability and transparency become even more important parts of the process. Finally, following all the elements of collaborative governance, the expected outcomes include a transformed collaboration. Collaborative governance shifts from a mandate into a more meaningful collaboration in which state and non-state actors are more equal in the process, resulting in the latter taking ownership of the process. If done correctly, convergence actions shift from ‘a government program’ into collaborative governance owned by all participants. In the long term, collaborative governance can also result in more effective public management. Achieving this is a challenging task for several reasons, including: (1) bringing about such a transformational result requires a long time, while local governments need to focus on their annual report to the central government; (2) the processes require network managers to have the ability to invite more stakeholders to actively engage; (3) raising awareness, knowledge, and power of the communities to be equal participants is a complex process; and (4) non-state actors need to understand that the issue matters to them, and such an understanding may be difficult to form if the issue does not directly affect them.

As a mandate, convergence actions provide a framework that makes local collaborative governance feasible, but achieving meaningful collaborative governance requires more collaborative governance elements than what Ansell and Gash proposed (Citation2007). Convergence actions are required to have a comprehensive institutional design as one of their initial conditions. Collaboration rules and procedures have been established. Local implementers need facilitative leadership, central and local policies that provide a legal basis for budget allocation, other forms of support, network managers, and community empowerment to transform the mandate into jointly owned collaborative governance. In addition to equality in decision-making and program planning, the collaborative process must be followed by accountability. Through this process, a network mandated by policy transitions to collaborative governance that is jointly owned by the involved actors.

5. Conclusion

Convergence actions are a request from Indonesia’s central government to its local governments to help them work together to stop stunting. The mandate has been carried out in West Java, where it has been seen that the process is mostly owned by government agencies, with only a small amount of participation from non-state actors. From the point of view of collaborative governance, convergence actions have a mandated institutional design, allow for starting conditions, and involve a collaborative process with state and non-state actors, supportive leadership, and a clear accountability system.

Non-state actors have not fully participated in the process, so each part needs to be made better. Also, non-state actors don’t know much about convergence actions, and local communities, which do most of the work at the grassroots level, need to be given more power and skills in program management. It is necessary to transform policy-mandated networks into a more practical structure for cooperative governance that belongs to all the involved actors. To do this, we need network managers, leaders who can make things easier, and central and local policymakers who can help. Communities need to be given the power to make sure that the collaborative process is fairer when it comes to making decisions and planning programs. This will encourage non-state actors to take charge of collaborative governance. Shifting a mandate into collectively owned collaborative governance will have significant implications for public health in Indonesia. Through collaborative governance, local communities become more aware of stunting interventions and the active role they can play in the process, leading to an empowering experience.

Non-state actors have not fully participated in the process, so each part needs to be made better. Non-state actors also don’t know much about the convergence actions, and local communities, which do most of the work at the grassroots level, need to be given more power and taught how to run programs. Policy-mandated networks need to be turned into a more useful CG structure that all the actors in the network own together. To do this, we need network managers, leaders who can make things easier, and central and local policymakers who can help. Communities need to be given the power to make sure that the collaborative process is fairer when it comes to making decisions and planning programs. This will encourage non-state actors to take ownership of CG. Shifting a mandate to collectively owned CG will have significant implications for public health in Indonesia. Through CG, local communities become aware of stunting interventions and the active role they can play in the process, leading to an empowering experience.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the research team who strongly supported this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguayo, V. M., and P. Menon. 2016. “Stop Stunting: Improving Child Feeding, Women’s Nutrition and Household Sanitation in South Asia.” Maternal & Child Nutrition 12: 3–11. doi:10.1111/mcn.12283.

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2007. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4): 543–571. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- Badan Pusat Statistik. 2020a. Jumlah Penduduk Hasil Proyeksi Menurut Provinsi dan Jenis Kelamin (Ribu Jiwa), 2018-2020. https://www.bps.go.id/indicator/12/1886/1/jumlah-penduduk-hasil-proyeksi-menurut-provinsi-dan-jenis-kelamin.html.

- Badan Pusat Statistik. 2020b. Laporan Indeks Khusus Penanganan Stunting 2019-2020.

- BPS. n.d. Persentase Balita Pendek Dan Sangat Pendek (Persen). https://www.Bps.Go.Id/Indikator/Indikator/View_data/0000/Data/1325/Sdgs_2/1.

- Castañer, X., and N. Oliveira. 2020. “Collaboration, Coordination, and Cooperation among Organizations: Establishing the Distinctive Meanings of These Terms through a Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Management 46 (6): 965–1001. doi:10.1177/0149206320901565.

- Connors-Tadros, L. 2019. “Why Collaboration Is Important Now and Opportunities for Future Research.” Early Education and Development 30 (8): 1094–1099. doi:10.1080/10409289.2019.1662689.

- DeHoog, R. H. 2015. “Collaborations and Partnerships across Sectors: Preparing the Next Generation for Governance.” Journal of Public Affairs Education 21 (3): 401–416. doi:10.1080/15236803.2015.12002206.

- Douglas, S., C. Ansell, C. F. Parker, E. Sørensen, P. ‘T Hart, and J. Torfing. 2020. “Understanding Collaboration: Introducing the Collaborative Governance Case Databank.” Policy and Society 39 (4): 495–509. doi:10.1080/14494035.2020.1794425.

- Emerson, K., and T. Nabatchi. 2015. Collaborative Governance Regimes. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Emerson, K., T. Nabatchi, and S. Balogh. 2012. “An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1093/jopart/mur011.

- Keast, R., K. Brown, and M. Mandell. 2007. “Getting the Right Mix: Unpacking Integration Meanings and Strategies.” International Public Management Journal 10 (1): 9–33. doi:10.1080/10967490601185716.

- Keast, R., and M. Mandell. 2014. “The Collaborative Push: Moving beyond Rhetoric and Gaining Evidence.” Journal of Management & Governance 18 (1): 9–28. doi:10.1007/s10997-012-9234-5.

- Kementerian Kesehatan RI. 2018. Hasil Utama Riskedas 2018.

- Kettl, D. F. 2006. “Managing Boundaries in American Administration: The Collaboration Imperative.” Public Administration Review 66: 10–19. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00662.x

- Koppenjan, J., and E.-H. Klijn. 2004. Managing Uncertainties in Networks: A Network Approach to Problem Solving and Decision Making. London: Routledge.

- Krogh, A. H. 2022. “Facilitating Collaboration in Publicly Mandated Governance Networks.” Public Management Review 24: 631–653. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1862288.

- Marek, L. I., D. J. P. Brock, and J. Savla. 2015. “Evaluating Collaboration for Effectiveness: Conceptualization and Measurement.” American Journal of Evaluation 36 (1): 67–85. doi:10.1177/1098214014531068.

- Martin, E., I. Nolte, and E. Vitolo. 2016. “The Four Cs of Disaster Partnering: Communication, Cooperation, Coordination and Collaboration.” Disasters 40 (4): 621–643. doi:10.1111/disa.12173.

- Milward, B. H., and K. G. Provan. 2006. A Manager’s Guide to Choosing and Using Collaborative Networks Networks (Networks and Partnerships Series).

- Ministry of Home Affairs. 2020. Peringkat Kinerja Kabupaten/Kota dalam Pelaksanakan Aksi Konvergensi Penurunan Stunting Terintegrasi Tahun 2021. Unpublished Report.

- Peters, B. G. 2018. “The Challenge of Policy Coordination.” Policy Design and Practice 1 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/25741292.2018.1437946.

- Popp, J. K., and A. Casebeer. 2015. “Be Careful What You Ask for: Things Policy-Makers Should Know before Mandating Networks.” Healthcare Management Forum 28 (6): 230–235. doi:10.1177/0840470415599113.

- Provan, K. G., and P. Kenis. 2007. “Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (2): 229–252. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum015.

- Purdy, J. M. 2012. “A Framework for Assessing Power in Collaborative Governance Processes.” Public Administration Review 72 (3): 409–417. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02525.x

- Rodríguez, C., A. Langley, F. Béland, and J. L. Denis. 2007. “Governance, Power, and Mandated Collaboration in an Inter-Organizational Network.” Administration & Society 39 (2): 150–193. doi:10.1177/0095399706297212.

- Segato, F., and J. Raab. 2019. “Mandated Network Formation.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 32 (2): 191–206. doi:10.1108/IJPSM-01-2018-0018.

- Spann, R. N. 1979. Government Administration in Australia. Sydney: George Allen and Unwin.

- Thomson, A. M., Perry, J. L., & Miller, T. K. (2007). Conceptualizing and Measuring Collaboration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 19(1), 23–56. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum036.

- Torfing, J., B. G. Peters, J. Pierre, and E. Sørensen. 2012. Interactive Governance: Advancing the Paradigm. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Torlesse, H., A. A. Cronin, S. K. Sebayang, and R. Nandy. 2016. “Determinants of Stunting in Indonesian Children: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Survey Indicate a Prominent Role for the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Sector in Stunting Reduction.” BMC Public Health 16 (1). doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3339-8.

- Victora, C. G., L. Adair, C. Fall, P. C. Hallal, R. Martorell, L. Richter, and S. Sachdev. 2008. “Maternal and Child Undernutrition: Consequences for Adult Health and Human Capital.” The Lancet 371: 340–357. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4.

- WHO. 2015. Stunting in a Nutshell. https://www.who.int/news/item/19-11-2015-stunting-in-a-nutshell.