?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Crime is one of the problems faced by countries worldwide. Theft, gambling, drug, fraud, persecution, and conflict are among the crimes that commonly occur in Indonesia, which may be accounted for by a range of factors, including economic ones. Land use also emerges as another factor leading to crimes. Land use at the village level can be divided into three categories: undiversified, moderately diversified, and diversified. This work applied two analysis models. First, it employed logistic regression to capture the criminal possibility of each land use category. Second, it applied Ordinary Least Square to view crimes holistically in each land use category. This paper suggests that mixed land use and public space could significantly lower crime probability. Meanwhile, using land as a business and industrial center was found to trigger crimes. The existence of prostitution areas in villages/subdistricts raises the possibility of a rise in human trafficking and sexual Harassment. This study showed that using land as a public space potentially increases conflicts in Indonesia. This study provided the Indonesian government with a new insight to consider when developing an area by taking land use diversity into account in order to minimize crime risks.

JEL:

1. Introduction

Research on criminal activity indicates that geographic and spatial arrangements affect social control (Wo Citation2019). Land use has the potential to either hinder or support crime due to activities carried out in that area (Zahnow Citation2018). Land use arrangements that attract people to gather in certain locations may prevent or support criminal activities (Brantingham and Brantingham Citation1995; P. L. Brantingham and Brantingham Citation1993).

Mixed land use may result in high road activities, creating a situation in which native people and migrants meet in the same place at the same time (Brantingham and Brantingham Citation1995; Felson and Boba Citation2010). High traffic density in mixed land appears to establish a correlation between one aspect and another, creating effective monitoring and the arrangement of undesired activities (Talen Citation1999). High population density and mixed land use can create an effective informal social control against crimes (Browning et al. Citation2010).

Mixed land use integrates various land functions, thus attracting road users at any time (Zahnow Citation2018). Mixed land use combines the various space functions of an area, such as residential, industrial, business, educational, medical, and religious. The theory of new urbanism asserts that mixed land use can create a more lively and safer environment as it triggers the presence of daily activities and economic activities, and potentially improves individual health by triggering walking activities (Grant Citation2002; Hirt Citation2016; Jacobs Citation1961). Land use diversities could potentially decrease the risk of crime by enhancing the public passive participation in maintaining security as the land use becomes more varied. Diverse land use also promote pedestrian activities, thus potentially creating passive public monitoring.

On the other hand, mixed land use results in weaker social control (Kurtz, Koons, and Taylor Citation1998). Increasing road activities may attenuate social control as foreigners come, increasing the probability of crime (Browning et al. Citation2010). It should be noted that not all foreigners potentially commit crime. However, a condition where foreigners who do not know each other gather in one place potentially reduces the degree of passive monitoring. Previous studies have reported high crime rates in commercial and entertainment areas (Block and Block Citation1984; P. Brantingham and Brantingham Citation1995), which were accounted for by the difficult social control due to dense traffic (Chang Citation2011). The nightlife, such as nightclubs, serves as a gathering place for uncommitted sexual relationships, which can lead to further crimes and violence against women (Duque et al. Citation2020).

Certain land use concentrations have been associated with the rate of crime (Wo Citation2019). The literature explains the connection between crimes against women, such as prostitution, and the existence of industrial areas, particularly mining (Garuba et al. Citation2020; Mahy Citation2011). Prostitution can be described as a kind of human trafficking which contributes to violence against women (Kovari and Pruyt Citation2012). The development of commercial and industrial areas has attracted some people to move to these areas (Taylor Citation1988). According to Jacobs (Citation1961), pedestrians could improve social control, while Taylor (Citation1988) considers that road activities tend to weaken social control, particularly in industrial and commercial areas. Taylor argues that the combination of business space and residential area may lead to gaps in the territorial spatial distribution. Business owners will find it difficult to monitor their surroundings where their business does not operate. On the other hand, abandoned commercial areas might present chances for criminal activity (Browning et al. Citation2010).

This study has analyzed the effect of certain land uses, such as mixed land use, public space, economic centers, and other land uses, on criminality in Indonesia. Does specific land usage, particularly in Indonesia, have an impact on crime? A similar previous study in the Indonesian context measured mixed land use using the cumulative value of the available public facilities (Muzayanah et al. Citation2020). In this study, mixed land use was measured using the land use mix index (Blau Citation1977). This study also compared the effects of three categories of land use: undiversified, moderately diversified, and diversified. Urban phenomena like street children, homeless people, prostitution, multiethnicity, and nightlife were used as the control variables in this study.

2. Theoretical background

A number of theories were applied, including the economic theory of crime (Becker Citation1968), Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED), routine activity theory (Cohen and Felson Citation1979), and broken windows theory (Wilson and Kelling Citation1982). According to Becker (Citation1968), an individuals’ decision to commit a crime is usually based on their benefit–cost analysis. Individuals will likely commit a crime if the expected benefit exceeds the expected cost. CPTED (Jeffery Citation1972) is an appropriate, effective environmental design used to minimize crime, which is comprised of access control, surveillance, territoriality, and maintenance.

Routine activity theory (Cohen and Felson Citation1979) sets three requirements for a crime to occur: a motivated offender, suitable targets of criminal victimization, and the absence of a guard to protect the criminal target. Broken windows theory (Wilson and Kelling Citation1982) emphasizes that crimes stem from the poor organization of society and that minor, unattended crimes could potentially turn into more serious crimes.

The mixture of land uses significantly contributes to a lower crime rate through people’s passive participation (Matijosaitiene et al. Citation2018; Wo Citation2019; Wo and Kim Citation2022; Zahnow Citation2018). The presence of public space also significantly minimizes the crime rate (Gibbons Citation2004; Matijosaitiene et al. Citation2018; Wo and Kim Citation2022; Zahnow Citation2018). Industrial land use could potentially increase the urbanization pattern and attract people to come (Lahiri-Dutt Citation2013; Matijosaitiene et al. Citation2018; Twinam Citation2017; Wo and Kim Citation2022). In addition, the geographical literature correlates industrial regions with gender identity, which can lead to gender-based violence (Lahiri-Dutt Citation2013). Meanwhile, business land use causes people to come and go, causing people with different motives to meet at the same time (Browning et al. Citation2010; Matijosaitiene et al. Citation2018; Twinam Citation2017; Weisburd et al. Citation2006; Wo and Kim Citation2022; Zahnow Citation2018; Zhang Citation2016).

Previous studies have discussed the effect of public facilities on the crime rate in their surroundings. These public facilities include hotels (Ho, Zhao, and Dooley Citation2017; Hua and Yang Citation2017; Huang, Kwag, and Streib Citation1998; Yang and Hua Citation2022), sports areas (Billings and Depken Citation2011; Kurland Citation2019; Ristea, Andresen, and Leitner Citation2018), and schools (Chen Citation2008; Hirschfield Citation2018; Jennings et al. Citation2011; Murray and Swatt Citation2013; Zahnow Citation2018). Other land uses are closely associated with urban areas, such as slums (Kamruzzaman and Hakim Citation2016; Monday, Ilesanmi, and Ali Citation2013; Teresia Citation2011), street children (Inciardi and Surratt Citation1998; Yu, Gao, and Atkinson-Sheppard Citation2019), and homeless (Baller et al. Citation2001; Pain and Francis Citation2004).

3. Methods

This study investigated the effect of land use (mixed land use, public open space, business location, industrial location, sports area, school, and slum) and other land uses in relation to five common crimes in Indonesia, i.e. theft, gambling, drugs, fraud, persecution, conflict, sexual harassment, and other crimes (include human trafficking). The presence of street children, homeless people, public facilities, prostitution, and nightclubs were among the aspects examined in this study.

Blau’s index was used to measure the land use mix. This index is commonly used to determine the diversity or heterogeneity of a social phenomenon. Zahnow (Citation2018) measured land use diversity using eight categories: residential building, entertainment building, industry, health facility, business, education, open space, and other. It was calculated using the following Equation (1):

(1)

(1)

Where p is the proportion of the total area determined for a certain i category. Blau's index ranges from 0 to 1, with lower values indicating homogeneity and higher values indicating heterogeneity (Blau Citation1977). Chimbadzwa, Dube, and Guveya (Citation2020) divided diversity into four groups: undiversified, moderately diversified, diversified, and highly diversified ().

Table 1. Blau’s index diversity categories.

The unit of analysis in this study was all villages/subdistricts in Indonesia (n = 83.931). The data was obtained from the Indonesia Statistics’ (BPS) 2018 Survey on Village Potentials (Badan Pusat Statistik Citation2018). This is a survey on the specific potentials possessed by every village/subdistrict in Indonesia, which is an important factor supporting regional planning.

This study employed two analysis models. First, it used logistic regression to analyze the probability of each crime in the villages/subdistricts. The dependent variable in this study was the dummy variable (1 = there is a crime and 0 = no crime). The dependent variables in this study included theft, gambling, drugs, fraud, persecution, conflicts, sexual harassment, and other crimes. Second, ordinary least square (OLS) was applied to analyze the total amount of crime in the unit of analysis. The OLS estimation resulted in three mixed land-use models: undiversified, moderately diversified, and diversified.

4. Results

This study explains Indonesia’s crime rates at the village/subdistrict level. Theft was the highest crime rate among the other types of crimes (). Around 37.778 (45,01%) villages/subdistricts in Indonesia reported theft. Meanwhile, gambling was the second highest offense (n = 12.842 villages/subdistricts, 15,30%), followed by drugs (12.579 villages/subdistricts, 14,99%). Other types of crime (e.g. burning, rape, murder, corruption, suicide, and human trafficking) were reported in 11.393 villages/subdistricts (13.57%).

Table 2. Percentage for rural-urban areas in terms of crime type.

In terms of land use diversity, most crimes occurred in undiversified villages. Theft occurred in 33.680 undiversified villages/subdistrict (40,13%), 4.043 (4,82%) moderately diversified villages/subdistricts, and 55 (0,07) diversified villages/subdistricts. Several other crimes were also reported in undiversified villages/subdistricts, including gambling (13.64%), drugs (13.23%), and fraud (9.19%).

In general, Indonesian villages/subdistricts do not exhibit diverse land use (). Only 13.47% of villages/subdistricts were reported to have public space. On average, each village/subdistrict had 50 business units. Most villages/subdistricts also did not have an industrial location, and only 38.31% of villages/subdistrict had hotel/inn facilities. Every village/subdistrict had a sports area and schools, and each village/subdistrict had, on average, two sport centers and 10 school units. Each village/subdistrict had 11 places of worship and 10 restaurant facilities on average.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics.

displays an overview of urban phenomena, e.g. slum locations, street children locations, and homeless people locations. Around 1.43% of villages/subdistricts had street children spots, and 0.68% of villages/subdistricts had homeless spots. Ethnic diversity is one of the characteristics of Indonesia, and 73.75% of Indonesian villages/subdistricts have a diverse range of ethnicities present. Urban phenomena are inseparable from entertainment facilities, including nightclubs (Straw Citation2004). In this regard, 3.48% of villages/subdistrict had nightclubs. Another effect of urban areas was localized prostitution (Hubbard and Sanders Citation2003), and 1.02% of the villages/subdistricts in Indonesia had prostitution sites.

4.1. Analysis of crime in Indonesia

Mixed land use in Indonesian villages/subdistricts can lower the risks of theft, gambling, drugs, fraud, and persecution (). The probability of theft, gambling, drugs, fraud, and persecution drop by 37.77%, 20.82%, 13.18%, 15.9%, and 9.61%, respectively, as the land use at the village/subdistrict level becomes more diverse. The presence of public space can reduce the crime probability in villages/subdistricts. Public space can lower the risk of theft by 3.26%, gambling by 3.04%, and drug-related crimes by 3.86% (sig. 1%). The fraud and persecution probabilities also drop along with the presence of public space in that area. The findings indicate that the presence of open space in villages/subdistricts potentially causes conflict amid the community, as the crime probability increases by 0.79% (sig. 1%) when more open spaces are built.

Table 4. Logistic regression result, marginal effect.

The presence of economic activities like what take place in industrial and business centers turned out to increase crime probability. The theft probability increases by 1.07% (sig. 1%) as the industrial center grows. The theft risk also increases by 0.08% as the business centers grow in the area of the villages/subdistrict. Gambling, drug-related crime, fraud, and persecution also increase along with the development of economic activities in both industrial and business centers.

Sport centers were found to significantly increase crime risks. The logistic regression showed that the theft probability rose by 1.78% (sig. 1%) along with the increase in the number of sports facilities in the villages/subdistricts. The gambling, drug-related crimes, and persecution probability also increased by 1.08%, 1.30%, and 0.25%, respectively. Schools were also found to increase the crime probability, as theft, gambling, drug abuse, and persecution may occur in such a setting.

Villages/subdistricts with slum areas were also at very high risk of criminal action. The logistic regression result indicates that the theft, gambling, and drug-related crime probabilities may increase by 0.96%, 0.21%, and 0.31%, respectively, as the slum area in the villages/subdistricts expands. A positive, significant relationship was noticed between the five crime categories and villages/subdistricts with street children spots, prostitution, and multiple ethnicities. The existence of nightclubs increases the number of crimes, particularly crimes against women such as human trafficking and commercial sex. The results correlate to the distance from the nightclub: a village's risk of crime decreases where there is an increased distance from the nightclub.

4.2. Crime analysis in terms of land use

shows the crime analysis in terms of land use categories. At the national level, mixed land use can lower crime risk in Indonesia. Criminal cases may drop by −1.4334% (sig. 1%) as the land use becomes more varied. Similarly, the presence of public open space may also reduce crime by 0.1376% (sig. 1%). The presence of an industrial center was found to increase the number of criminal cases by 0.0573% (sig. 1%). A positive, significant relationship between business centers, sport centers, schools, and crime probability was also noticed.

Table 5. OLS regression analysis results on crime by land use category.

Villages/subdistricts in urban areas were at risk of an increased crime rate by 0.3040% (sig.1%). The use of the land as slums, where there were street children, and as homeless spots may increase the crime risk by 0.0285% (sig. 1%), 0.9020% (sig. 1%), and 0.2175% (sig. 5%), respectively. A positive, significant relationship was also noticed among the control variables, i.e. multiple ethnicities, prostitution, and nightclubs. Comparing criminal cases in villages/subdistricts to the distance to the nearest nightclub, it was found that villages/subdistricts located 10–25 km from the nearest nightclub could lower the crime risks by 0.1416% (sig. 1%), while those located > 75 km from the nearest nightclub had lowered crime risks by 0.3334% (sig. 1%), both compared to villages/subdistricts located 0–10 km from the nearest nightclub. In other words, the crime rate appears to drop when the villages/subdistricts are located further from the nearest nightclub.

4.2.1. Undiversified

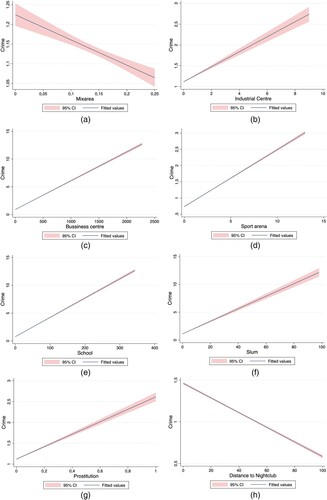

Mixed land use in undiversified areas could lower crime risks in Indonesia by 1.972% (). Meanwhile, the presence of economic centers in undiversified areas could increase the crime rate by 0.0614% (sig. 1%) (industrial centers) and 0.0022% (sig. 1%) (business centers). Public open spaces could reduce the crime rate by 13.84% (sig. 1%). Slum areas, street children, and prostitution could increase the crime rates in undiversified areas.

Sporting areas positively and significantly relate to crime (.d). Furthermore, the presence of schools (.e) and slums (.f) are positively and significantly associated with crimes in undiversified villages/subdistricts. Graph 1 two-way liftci showed that in villages with undiversified land use, industrial centers, business centers, sports areas, schools, and slums may increase the associated crime rates. In this case, prostitution areas could potentially contribute to an increase in crime (.G). The area surrounding nightclubs are a magnet for criminals. This is proven by the fact that the further a region is from a nightclub, the lower the crime rate.

4.2.2. Moderately diversified

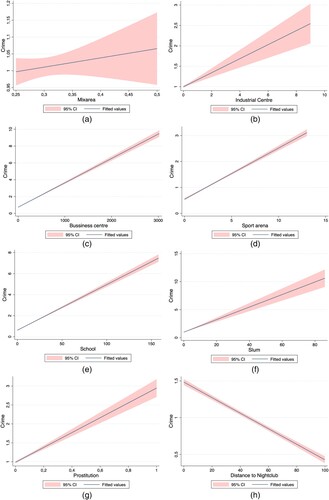

Mixed land use in moderately diversified areas could lower crime risks in Indonesia. The model indicates a negative and significant relationship between mixed land use and total crime rate. The crime rate was found to drop by 0.5013% (sig.10%) as the land was used more diversely. Although business centers may increase the crime rate in this area, the increase was insignificant. In other words, mixed land use can still be used to lower the crime rates in villages/subdistricts with moderately diversified land use.

Sporting areas are positively and significantly related to crime (.d). The presence of schools (. e) and slums (.f) are positively and significantly associated with crimes in moderately diversified villages/subdistricts. Graph 2 two-way liftci showed that, in villages with moderately diversified land use, industrial centers, business centers, sport area, schools, slums and prostitution may increase the crime rates.

4.2.3. Diversified

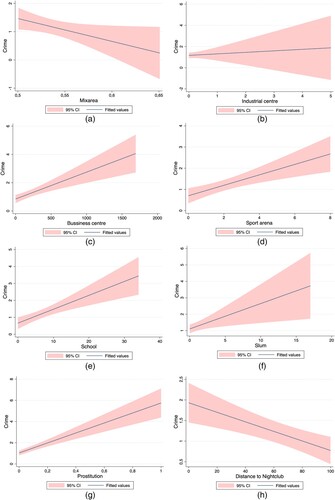

Mixed land use in diversified areas did not significantly lower crime risks in Indonesia. The land use for industrial and business centers in diversified villages/subdistricts did not significantly affect the crime risk in Indonesia. The presence of the public could lower criminal cases by 0.9104% (sig. 1%). In other words, highly mixed land use in diversified areas did not affect the crime rate in that area. Business and industrial centers also do not significantly affect the crime rate.

Sporting areas are positively and significantly related to crime (.d). The presence of schools (.e) and slums (.f) are positively and significantly associated with crimes in diversified villages/subdistricts. Graph 3 two-way liftci shows that in villages with diversified land use, industrial centers, business centers, sporting areas, schools, slums and prostitution may increase crime rates.

5. Discussion

Mixed land use potentially lowers the risks of theft, gambling, drug-related crimes, fraud, and persecution due to public passive monitoring (Zahnow Citation2018). Mixed land use can also serve as social control to prevent crimes (Wo and Kim Citation2022). Land with more diverse uses in an area will likely result in more active participation in maintaining the security of the area. This is in line with Jacob’s (Citation1961) ‘Eyes on the Streets’, depicting an informal public security guard. A negative relationship between mixed land use and crime rates was noticed in undiversified (.a) and diversified (.a) land. Mixed land use in undiversified and diversified villages/subdistricts potentially reduces the crime rates.

Land used as public space was found to potentially reduce the crime rate (). A negative, significant relationship was found between public space, land diversity, and crime categories. The presence of public space supports the CPTED, as it allows for easier social control and the monitoring of potential crimes (Bogar and Beyer Citation2016; Shepley et al. Citation2019; Sukartini, Auwalin, and Rumayya Citation2021). In addition, the presence of public space also increases the public passive participation in maintaining security. However, this study found that open space may potentially cause conflicts associated with land acquisition during the establishment of the open space. Conflicts of interest often emerge between individuals or even between individuals and the government. The establishment of open space may worsen the racial or ethnic discrimination issues in the community. Open space is also inseparable from the conflicts of interest among various parties, which leads to economic, social, political, and cultural conflicts.

Using land as an industrial center potentially increases the crime risk. The presence of foreigners and dense activities in industrial areas may attenuate public social control (Jubit et al. Citation2021). The increased crime rates due to industrial center development were noticed in all undiversified (.b), moderately diversified (2.b), and diversified (3.c) villages/subdistricts. A similar finding was also noticed in the relationship between business centers and the five crime types. This study supports Zahnow (Citation2018), who stated that non-residential land use tends to weaken social interactions and eventually weakens social control in the area. Since business locations may attract foreigners, their presence could potentially weaken social control. Industrial locations are situations that are vulnerable to causing inequality, especially related to gender (Lahiri-Dutt Citation2013).

The presence of educational facilities (e.g. schools) can increase crime, particularly in undiversified and moderately diversified areas (.e and 2.e, respectively). While schools are dynamic and serves as the main education focus in society, social interactions within this area can increase crime risks, including drug-related crimes and persecution. Billings and Depken (Citation2011) suggest that adolescents can potentially commit offenses in the school environment. Another land use examined in this study was places of worship. Places of worship are an easy target for property theft (Scheitle Citation2016). However, the presence of places of worship in villages/subdistricts can reduce gambling and drug-related crimes, which could be attributed to the moral values adhered to by those who follow the religion in that area.

Locations with high crime risks, like slum areas, street children, and spots for homeless people, may significantly increase the risk of crime as a whole. This is in line with the broken windows theory, which states that an unattended minor offense may result in more serious crimes. These areas increase the crime rates through their poor systems and the community around them (Orak and Rahaei Citation2015). The presence of street children potentially increases crime as their lifestyles are close to alcohol and drug abuse (Grinman et al. Citation2010; Neale and Stevenson Citation2015).

Other land uses highlighted in this study are prostitution and nightclubs. Prostitution is closely associated with drug-related crimes. Alcohol, illegal drugs, and brawls are typically inseparable from prostitution (Demant Citation2013; Duque et al. Citation2020), while nightclubs potentially increase the risk of persecution and conflicts in society. The risk of persecution was found to increase along with the presence of nightclubs in certain areas. Nightclubs are the most prevalent locations for violence, including sexually motivated violence (Duque et al. Citation2020). We discovered a strong connection between prostitution and human trafficking (Alvarez and Alessi Citation2012; Lee and Persson Citation2012). The legalization of prostitution influences the increase in human trafficking (Cho, Dreher, and Neumayer Citation2013). Prostitution and human trafficking are facilitated by various nightlife entertainment venues such as bars, discos, and karaoke rooms (Saat Citation2009).

The research model proves that the distance to the nightclub significantly affects crime rates in the area, where crime rates tend to be lower in villages/subdistricts located far from the nightclub. This is in line with routine activity theory which states that land used for entertainment could attract people with different motives and purposes to come, hence offenders can easily target his/her potential victims (Cochran, Bromley, and Branch Citation2000; Harper, Khey, and Nolan Citation2013; Kingma Citation2008).

6. Conclusion and policy implications of this study

Based on the results of the data analysis, mixed land use can reduce crimes through social control and passive monitoring. This implies the Indonesian people's high awareness of maintaining the security of their surroundings. Public open spaces could lower crime rates through the contribution made to public health, while land use for business, industry, and nightclubs may increase the risk of crime as they attract outsiders to enter areas with low social control.

Based on social control benefits, low-risk crime occurs in areas where there is diverse land use. We criticize the government and the business community's strategies for developing elite houses far away from the public. It is necessary to create security posts in these areas or areas with low diversity, such as setting up a security team to carry out routine patrols around the location.

Slum areas and street children were found to potentially increase the crime rate due to various disparities in terms of education, social, and economic aspects. Areas near nightclubs were also found to increase the crime rate due to poor monitoring. Nightclubs also attract offenders to commit crimes. Therefore, the government must regulate or prevent the establishment of nightlife spots such as discotheques and karaoke. The government should continue to enforce its current rules and regulations.

The existence of prostitution locations as places for sexual relations without commitment might provoke societal uproar. Another aspect of prostitution is that it may lead to violence, particularly against women, children, and domestic violence. Prostitution is directly linked to human trafficking, particularly among women and children. The government regulation has sufficient power to prohibit all types of prostitution. Besides that, civic participation is necessary for enhancing social control and increasing people's concern for their surroundings.

This study highlighted the importance of social control, especially in areas with a high number of migrants. It is necessary for the smallest unit of government apparatus (the RT/RW level) to actively check the identity of migrants. Local community participation in maintaining security is also necessary for controlling any phenomenon in their environment. This is because gender-based crimes frequently occur in public places. The government needs to pay attention to abandoned land, especially in industrial agglomerations, to ensure its economic and security merits.

It is necessary to build public open spaces in areas with poor air quality to improve the air quality. Governments are expected to pay attention to street children and equip them with the skills necessary to find a job. In this regard, the community could support the government's efforts by not giving their money to street children.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alvarez, Maria Beatriz, and Edward J. Alessi. 2012. “Human Trafficking is More than Sex Trafficking and Prostitution.” Affilia 27 (2): 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109912443763.

- Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS). 2018. Village Potentials (Podes) 2018. Jakarta: BPS-Statistics Indonesia.

- Baller, Robert D., Luc Anselin, Steven F. Messner, Glenn Deane, and Darnell F Hawkins. 2001. “Structural Covariates of U.S. Country Homecides Rates: Incorporating Spatial Effects*.” Criminology 39 (3): 561–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00933.x.

- Becker, Gary S. 1968. “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach.” Journal of Political Economy 76 (2): 169–217. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1830482.

- Billings, Stephen B., and Craig A. Depken. 2011. “Sport Events and Criminal Activity: A Spatial Analysis.” Violence and Aggression in Sporting Contests. Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6630-8_11.

- Blau, Peter M. 1977. “Inequality and Heterogeneity: A Primitive Theory of Social Structure.” Social Forces 58 (2): 677. https://doi.org/10.2307/2577612.

- Block, Carolyn Rebecca, and Richard L. Block. 1984. “Crime Definition, Crime Measurement, and Victim Surveys.” Journal of Social Issues 40 (1): 137–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1984.tb01086.x.

- Bogar, Sandra, and Kirsten M. Beyer. 2016. “Green Space, Violence, and Crime.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 17 (2): 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015576412.

- Brantingham, Patricia L, and Paul J. Brantingham. 1993. “Nodes, Paths and Edges: Considerations on the Complexity of Crime and the Physical Environment.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 13 (1): 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80212-9.

- Brantingham, Patricia, and Paul Brantingham. 1995. “Criminality of Place.” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 3 (3): 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02242925.

- Browning, Christopher R, Reginald A Byron, Catherine A Calder, Lauren J Krivo, Mei-Po Kwan, Jae-Yong Lee, and Ruth D Peterson. 2010. “Commercial Density, Residential Concentration, and Crime: Land Use Patterns and Violence in Neighborhood Context.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 47 (3): 329–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427810365906.

- Chang, Dongkuk. 2011. “Social Crime or Spatial Crime? Exploring the Effects of Social, Economical, and Spatial Factors on Burglary Rates.” Environment and Behavior 43 (1): 26–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509347728.

- Chen, Greg. 2008. “Communities, Students, Schools, and School Crime.” Urban Education 43 (3): 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085907311791.

- Chimbadzwa, Zvinaiye, Lighton Dube, and Emmanuel Guveya. 2020. “Level of Diversity of Firms Listed On The Zimbabwe Stock Exchange.” International Journal of Humanities, Art and Social Studies (IJHAS) 5 (4): 27–31.

- Cho, Seo-Young, Axel Dreher, and Eric Neumayer. 2013. “Does Legalized Prostitution Increase Human Trafficking?” World Development 41 (January): 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.023.

- Cochran, John K., Max L. Bromley, and Kathryn A Branch. 2000. “Victimization and Fear of Crime in an Entertainment District Crime ‘Hot Spot:’ A Test of Structural-Choice Theory.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 24 (2): 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02887592.

- Cohen, Lawrence E, and Marcus Felson. 1979. “Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach.” American Sociological Review 44 (4): 588. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094589.

- Demant, Jakob. 2013. “Affected in the Nightclub. A Case Study of Regular Clubbers’ Conflictual Practices in Nightclubs.” International Journal of Drug Policy 24 (3): 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.04.005.

- Duque, Elena, Javier Rodríguez-Conde, Lídia Puigvert, and Juan C. Peña-Axt. 2020. “Bartenders and Customers’ Interactions. Influence on Sexual Assaults in Nightlife.” Sustainability 12 (15): 6111. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156111.

- Felson, Marcus, and Rachel Boba. 2010. Crime and Everyday Life. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483349299.

- Garuba, Dauda, Dieter Bassi, Olubukola Moronkola, Timothy Bata, Philip Obasi, Musa Abutudu, Yunusa Ya’u, Adesoye Mustapha, and Nathaniel Goki. 2020. Impact of Mining on Women, Youth and Others in Selected Communities in Nigeria.

- Gibbons, Steve. 2004. “The Costs of Urban Property Crime.” The Economic Journal 114 (499): F441–F463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00254.x.

- Grant, Jill. 2002. “Mixed Use in Theory and Practice: Canadian Experience with Implementing a Planning Principle.” Journal of the American Planning Association 68 (1): 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360208977192.

- Grinman, Michelle N, Shirley Chiu, Donald A. Redelmeier, Wendy Levinson, Alex Kiss, George Tolomiczenko, Laura Cowan, and Stephen W Hwang. 2010. “Drug Problems among Homeless Individuals in Toronto, Canada: Prevalence, Drugs of Choice, and Relation to Health Status.” BMC Public Health 10 (1): 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-94.

- Harper, Dee Wood, David N. Khey, and Gwen Moity Nolan. 2013. “Spatial Patterns of Robbery at Tourism Sites: A Case Study of the Vieux Carré in New Orleans.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 38 (4): 589–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-012-9193-z.

- Hirschfield, Paul J. 2018. “Schools and Crime.” Annual Review of Criminology 1 (1): 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-032317-092358.

- Hirt, Sonia A. 2016. “Rooting out Mixed Use: Revisiting the Original Rationales.” Land Use Policy 50 (December): 134–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.09.009.

- Ho, Taiping, Jinlin Zhao, and Brendan Dooley. 2017. “Hotel Crimes: An Unexplored Victimization in the Hospitality Industry.” Security Journal 30 (4): 1097–1111. https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2016.11.

- Hua, Nan, and Yang Yang. 2017. “Systematic Effects of Crime on Hotel Operating Performance.” Tourism Management 60 (December): 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.11.022.

- Huang, W. S. Wilson, Michael Kwag, and Gregory Streib. 1998. “Exploring the Relationship Between Hotel Characteristics and Crime.” Hospitality Review 16 (1): 81–93.

- Hubbard, Phil, and Teela Sanders. 2003. “Making Space for Sex Work: Female Street Prostitution and the Production of Urban Space.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27 (1): 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00432.

- Inciardi, James A, and Hilary L Surratt. 1998. “Children in the Streets of Brazil: Drug Use, Crime, Violence, and HIV Risks.” Substance Use & Misuse 33 (7), https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089809069809.

- Jacobs, Jane. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

- Jeffery, C. Ray. 1972. “Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design.” Criminology 10 (2): 191–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1972.tb00553.x.

- Jennings, Wesley G., David N. Khey, Jon Maskaly, and Christopher M. Donner. 2011. “Evaluating the Relationship Between Law Enforcement and School Security Measures and Violent Crime in Schools.” Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations 11 (2): 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332586.2011.581511.

- Jubit, Norita, Tarmiji Masron, Mohd Norarshad Nordin, Azizul Hafiz Jamian, and Adibah Yusuf. 2021. “Spatial Analysis of Vehicle Theft in Kuching, Sarawak.” Malaysia Journal of Tropical Geography 47 (1 and 2): 46–66.

- Kamruzzaman, Md, and Md Hakim. 2016. “Socio-Economic Status of Slum Dwellers: An Empirical Study on the Capital City of Bangladesh.” Age (Years) 1 (December): 13–18.

- Kingma, Sytze F. 2008. “Dutch Casino Space or the Spatial Organization of Entertainment.” Culture and Organization 14 (1): 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759550701863324.

- Kovari, A., and Erik Pruyt. 2012. Prostitution and Human Trafficking: A Model-Based Exploration and Policy Analysis.

- Kurland, Justin. 2019. “Arena-Based Events and Crime: An Analysis of Hourly Robbery Data.” Applied Economics 51 (36): 3947–3957. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1587590.

- Kurtz, Ellen M., Barbara A. Koons, and Ralph B. Taylor. 1998. “Land Use, Physical Deterioration, Resident-Based Control, and Calls for Service on Urban Streetblocks.” Justice Quarterly 15 (1): 121–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418829800093661.

- Lahiri-Dutt, Kuntala. 2013. “Gender (Plays) in Tanjung Bara Mining Camp in Eastern Kalimantan, Indonesia.” Gender, Place & Culture 20 (8): 979–998. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2012.737770.

- Lee, Samuel, and Petra Persson. 2012. “Human Trafficking and Regulating Prostitution.” SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2057299.

- Mahy, Petra. 2011. “Sex Work and Livelihoods: Beyond the ‘Negative Impacts on Women’ in Indonesian Mining.” In Gendering the Field. Towards Sustainable Livelihoods for Mining Communities, ANU Press. https://doi.org/10.22459/GF.03.2011.04.

- Matijosaitiene, Irina, Peng Zhao, Sylvain Jaume, and Joseph Gilkey, Jr. 2018. “Prediction of Hourly Effect of Land Use on Crime.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 8 (1): 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi8010016.

- Monday, Eze, F. Ilesanmi, and H. Ali. 2013. “Security and Safety Planning in Slum Areas of Jimeta, Adamawa State, Nigeria.” International Journal of Multidisciplinary and Current Research 1: 134–45.

- Murray, Rebecca K, and Marc L Swatt. 2013. “Disaggregating the Relationship Between Schools and Crime.” Crime & Delinquency 59 (2): 163–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128709348438.

- Muzayanah, Irfani Fithria Ummul, Suahasil Nazara, Benedictus Raksaka Mahi, and Djoni Hartono. 2020. “Is There Social Capital in Cities? The Association of Urban Form and Social Capital Formation in the Metropolitan Cities of Indonesia.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 24 (4): 532–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2020.1730934.

- Neale, Joanne, and Caral Stevenson. 2015. “Social and Recovery Capital amongst Homeless Hostel Residents Who Use Drugs and Alcohol.” International Journal of Drug Policy 26 (5): 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.09.012.

- Orak, Mahnoosh, and Omid Rahaei. 2015. “Nalysis of Social Damages Caused by Slums of Ahvaz Metropolitan.” European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences: Proceedings 4 (3): 288–296.

- Pain, Rachel, and Peter Francis. 2004. “Living with Crime: Spaces of Risk for Homeless Young People.” Children’s Geographies 2 (1): 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/1473328032000168796.

- Ristea, Alina, Martin A. Andresen, and Michael Leitner. 2018. “Using Tweets to Understand Changes in the Spatial Crime Distribution for Hockey Events in Vancouver.” The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien 62 (3): 338–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12463.

- Saat, Gusni. 2009. “Human Trafficking from the Philippines to Malaysia.” South Asian Survey 16 (1): 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/097152310801600109.

- Scheitle, Christopher P. 2016. “Crimes Occurring at Places of Worship.” International Review of Victimology 22 (1): 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269758015610855.

- Shepley, Mardelle, Naomi Sachs, Hessam Sadatsafavi, Christine Fournier, and Kati Peditto. 2019. “The Impact of Green Space on Violent Crime in Urban Environments: An Evidence Synthesis.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (24): 5119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245119.

- Straw, Will. 2004. “Cultural Scenes.” Loisir et Société / Society and Leisure 27 (2): 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/07053436.2004.10707657.

- Sukartini, Ni Made, Ilmiawan Auwalin, and Rumayya Rumayya. 2021. “The Impact of Urban Green Spaces on the Probability of Urban Crime in Indonesia.” Development Studies Research 8 (1), https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2021.1950019.

- Talen, Emily. 1999. “Sense of Community and Neighbourhood Form: An Assessment of the Social Doctrine of New Urbanism.” Urban Studies 36 (8): 1361–1379. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098993033.

- Taylor, Ralph B. 1988. Human Territorial Functioning. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511571237.

- Teresia, Ndikaru Wa. 2011. “Crime Causes and Victimization in Nairobi City Slums.” Inter of National Journal Urrent Research 3 (12): 275–285.

- Twinam, Tate. 2017. “Danger Zone: Land Use and the Geography of Neighborhood Crime.” Journal of Urban Economics 100 (December): 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2017.05.006.

- Weisburd, David, Laura Wyckoff, Justin Ready, John E. Eck, Joshua C. Hinkle, and Frank Gajewski. 2006. “Does Crime Just Move Around The Corner? A Controlled Study of Spatial Displacement and Diffusion of Crime Control Benefits.” Criminology 44 (3), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00057.x.

- Wilson, James Q, and George L. Kelling. 1982. “Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety.” The Atlantic Monthly - THEATLANTIC 249.

- Wo, James C. 2019. “Mixed Land Use and Neighborhood Crime.” Social Science Research 78 (December): 170–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.12.010.

- Wo, James C., and Young-An Kim. 2022. “Neighborhood Effects on Crime in San Francisco: An Examination of Residential, Nonresidential, and ‘Mixed’ Land Uses.” Deviant Behavior 43 (1): 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2020.1779988.

- Yang, Yang, and Nan Hua. 2022. “Does Hotel Class Moderate the Impact of Crime on Operating Performance?” Tourism Economics 28 (1): 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816620949040.

- Yu, Yanping, Yunjiao Gao, and Sally Atkinson-Sheppard. 2019. “Pathways to Delinquency for Street Children in China: Institutional Anomie, Resilience and Crime.” Children and Youth Services Review 102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.05.012.

- Zahnow, Renee. 2018. “Mixed Land Use: Implications for Violence and Property Crime.” City & Community 17 (4): 1119–1142. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12337.

- Zhang, Wenjia. 2016. “Does Compact Land Use Trigger a Rise in Crime and a Fall in Ridership? A Role for Crime in the Land Use–Travel Connection.” Urban Studies 53 (14): 3007–3026. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015605222.