?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study aimed to investigate the association between post-materialist values and subjective well-being in European countries, while examining the complex relationships between the diffusion of post-materialist values, economic development, and democratization. This study analyzed data from the European Values Study and World Values Survey between 1981 and 2022 using finite mixture models and fixed-effects models. The results show that the positive association between diffusing post-materialist values and changes in average life satisfaction was mediated by social changes, including economic development and democratization. However, a negative association between economic development and democratization emerged; although both were positively associated with changes in national life satisfaction, their associations could be offset by each other. This implies that while social change is intertwined with social values and subjective well-being, the relationships between them are highly intricate.

Introduction

This study aimed to examine the association between social changes, such as economic development and democratization, and changes in national subjective well-being (i.e. subjective well-being at the country level). Previous research has clarified that subjective well-being is determined personally and socially. Therefore, subjective well-being is predicted to vary depending on social changes. Graham and Pettinato (Citation2001) demonstrated that inflation and unemployment were negatively associated with subjective well-being, whereas preference for democracy was positively associated with it. Spruk and Kešeljević (Citation2016) revealed that countries with better economic institutions and a higher level of economic freedom were more likely to experience greater subjective well-being. Thus, a good economy and democracy appear to be positively associated with subjective well-being.

However, social changes (economic development and democratization) might not have a simple linear relationship with subjective well-being. For instance, although income is associated with individual subjective well-being, economic prosperity is not necessarily positively correlated with national subjective well-being in developed countries (Easterlin Citation2001; Citation1974; Citation1995; Easterlin et al. Citation2010). The associations between economic prosperity and national subjective well-being may be highly complicated. Income inequality could contribute to this complex association. Individuals who compare their income to that of others tend not to be happy (Alderson and Katz-Gerro Citation2016). Therefore, income inequality reduces the self-perception of social status and individual subjective well-being (Schneider Citation2019). Consequently, income inequality is negatively associated with national subjective well-being (Graafland and Lous Citation2018). In other words, increased income inequality due to economic development increases average income and reduces average happiness in society (Gardarsdottir et al. Citation2018; Wilkinson Citation2005; Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010). However, Schröder (Citation2016) indicated that as people become accustomed to long-term inequality, only short-term increases in inequality can cause dissatisfaction with their lives.

Similarly, the association between political regimes and national subjective well-being is complex and multifaceted. Previous studies have reported that social democratic regimes are positively associated with individual and national subjective well-being (Frey and Stutzer Citation2000; Graafland and Compen Citation2015; Pacek, Radcliff, and Brockway Citation2019). Good governance is a general requirement for happiness (Ott Citation2010). However, the associations between political regimes and national subjective well-being vary depending on social factors. Furthermore, this complicated relationship may have been caused by evaluations of political processes (Christmann and Torcal Citation2017). Rode (Citation2013) demonstrated differences in the evaluation criteria for political regimes between developing and developed countries. Dorn et al. (Citation2007) observed a significant positive relationship between democracy and happiness, with a stronger influence in countries with an established democratic tradition. However, direct democracy did not exhibit a robust relationship with subjective well-being in Switzerland, one of the wealthiest and most democratic countries (Dorn et al. Citation2008; Stadelmann-Steffen and Vatter Citation2012). Therefore, social researchers should consider differences in social contexts between countries. Orviska, Caplanova, and Hudson (Citation2014) noted that the association between democratic satisfaction and subjective well-being was less evident among wealthy people and in rich countries. Furthermore, Radcliff and Shufeldt (Citation2016) demonstrated that the positive relationships between direct democracy and subjective well-being were more pronounced among people in the lowest income group. Thus, the lack of significant association between direct democracy and national subjective well-being in Switzerland does not necessarily mean that direct democracy is unrelated to subjective well-being.

The complicated relationships between economic development, democratization, and changes in national subjective well-being imply that these factors are correlated to changes in social values. Shifting from materialist to post-materialist values could change the criteria for happiness in that society (Delhey Citation2010). Similarly, generalized trust related to democratization might be associated with national subjective well-being (Ekici and Koydemir Citation2014). Moreover, modernization, with the rise of individualism and emancipative values, might strengthen the significance of freedom in subjective well-being (Minkov, Welzel, and Schachner Citation2020). In summary, the complicated relationships between economic development, democratization, and national subjective well-being should be examined, and to do so, the role social values play in national subjective well-being should be specified.

Theory and hypotheses

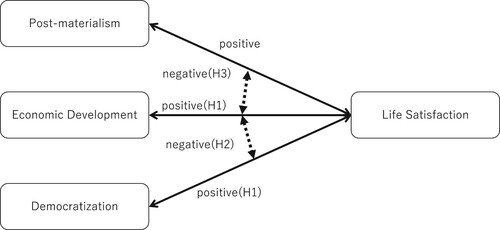

This study examined the relationships between economic development, democratization, social values, and national life satisfaction. De Simone et al. (Citation2022) observed that economic development and democratization were correlated. Nevertheless, the association between economic development and democratization is thought to be negative. Berggren, Bjørnskov, and Nilsson (Citation2018) observed a positive association between social equity and general happiness, particularly in countries without high levels of economic freedom. Orviska, Caplanova, and Hudson (Citation2014) revealed that the positive associations between democracy and subjective well-being were more pronounced among economically poor countries. Radcliff and Shufeldt (Citation2016) found that the positive correlation between direct democracy and subjective well-being was mostly observed among the poorest individuals. These findings imply that there is a negative association between economic development and democratization. Researchers believe that sound democratic regimes strengthen the economy and that democracy is, therefore, positively associated with subjective well-being (Daoust and Nadeau Citation2021; Loveless and Binelli Citation2020; Quaranta and Martini Citation2016; Citation2017). In other words, people tend to support democracy because they perceive it as indirectly contributing to social wealth within society (Daoust and Nadeau Citation2021). However, once a nation achieves economic prosperity, its support for democracy tends to decline. Consequently, for changes in national life satisfaction, the association between economic development and democratization will become negative.

Therefore, the following hypothesis was deduced:

Hypothesis 1. Individuals residing in democratic countries are more likely to get satisfaction from their lives than those in non-democratic countries. Similarly, individuals residing in affluent countries are more likely to get satisfaction from their lives than those in poor countries.

Hypothesis 2. The association between democratization and changes in national life satisfaction is weaker among economically developed nations.

Furthermore, national life satisfaction is not determined only by economic prosperity. The association between economic development and subjective well-being is assumed to be mediated by social values. People devalorize material concerns and valorize non-material concerns by shifting from materialist to post-materialist values because of economic development (Delhey Citation2010). As people seek economic freedom, there is a correlation between subjective well-being and economic prosperity (Graafland Citation2019; Schyns Citation1998). However, the association between economic prosperity and subjective well-being declines gradually and relatively with economic development, and people tend to have more interest in social capital, such as social trust, rather than material concerns (Delhey and Dragolov Citation2014). According to Zagrebina (Citation2018), the association between social capital (i.e. marital status, church attendance, and participation in sports organizations) and subjective well-being is more pronounced in democratic countries, whereas the association with material concerns (i.e. income and educational level) is more pronounced in non-democratic countries.

Therefore, the following hypothesis was deduced:

Hypothesis 3. Shifting from materialist to post-materialist values weakens the association between economic development and changes in national life satisfaction.

Data and methods

Data

This study used data from the European Values Study (EVS) (Citation2022) and World Values Survey (WVS) (Haerpfer et al. Citation2022). The EVS and WVS data are available to researchers via the official websites (https://europeanvaluesstudy.eu and https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/) and are fully anonymized. The EVS provides repeated cross-sectional social surveys to investigate social value among Europeans. Additionally, each social survey in the EVS has common inquiry items related to social values with other EVS surveys. Therefore, the EVS data are suitable for examining changes in the association between life satisfaction, economic prosperity, and democracy among European countries. Moreover, to reflect recent trends among European countries in this study, I added data from WVS Wave 7 (2017–2022) to the data from the EVS.

The EVS has been conducted five times since 1981, namely, in 1981, 1990, 1999, 2008, and 2017, with varying numbers of countries in each wave. Consequently, some countries were included in all five waves (e.g. France, Germany, or Great Britain), whereas others were included in only one wave (e.g. Cyprus, Kosovo, or Moldova). As data from the latter could not be used to examine changes in national life satisfaction, they were excluded from the analyses. Additionally, the data for Armenia, Czechia, Germany, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, and Ukraine from the WVS Wave 7 were added to the data from the EVS.

The latent structure of individual life satisfaction was analyzed using information collected from 176,088 respondents in Waves 1–5 of the EVS and Wave 7 of the WVS after excluding respondents with missing values for the variables used in this study. The data included 168 surveys of the EVS and WVS Wave 7. Changes in national life satisfaction were analyzed using data from 149 surveys in 43 countries (see Table S1 in the Supplemental Material). Although not all data from the EVS could be utilized due to various limitations, the data in this study were suitable for analyzing changes in social values among European countries.

Variables

Dependent variables. Life satisfaction was treated as a dependent variable in this study. In all waves of EVS and WVS Wave 7, life satisfaction was calculated using the following query: ‘All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?’ Responses were rated on a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 10. The variable was treated as a continuous variable (Sullivan and Artino Citation2013), and average life satisfaction at the country level was also considered as a dependent variable. It should be noted that life satisfaction is not equal to subjective well-being, but rather a part of it. Therefore, this study could not analyze subjective well-being itself, typifying a limitation of this study.

Independent variables at the country level. To specify the latent structure for subjective well-being among Europeans and examine changes in national subjective well-being, this study used the Liberal Democracy Index (LDI) and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (current US$) for the survey year (see Table S1 in the Supplemental Material). The LDI, published by the Varieties of Democracy Project (V-dem), is the most reliable and comprehensive index for measuring democracy (Varieties of Democracy Citation2022). Compared to the democracy score published by Freedom House, the LDI published by V-dem has a larger variance and is more helpful in estimating the level of democracy of each country. Additionally, unlike the Democracy Index published by the Economic Intelligence Unit, the LDI by V-dem contains long-term data on democracy levels worldwide. Therefore, the LDI published by V-dem is considered one of the most reliable and comprehensive indexes for democracy. Furthermore, this study collected information on the GDP per capita for each country from the World Bank website (The World Bank Citation2022) and used it as an index of national economic prosperity. Although GDP per capita is one of the most intuitive measures of a country’s wealth and economic prosperity, the distribution of GDP per capita was highly skewed. Thus, it was log-transformed before being used as an independent variable in the regression models of this study. According to the results of the Shapiro – Wilk normality tests, the null hypothesis for GDP per capita could be statistically rejected (0.84, p < 0.001), while the null hypothesis for log-transformed GDP per capita could not be statistically rejected at the 0.01 level.

Independent variables at the individual level. To specify the latent structure of subjective well-being among Europeans, this study used the following variables: sense of freedom, relative income (1–11), employment status (self-employed, full-time employed, part-time employed, unpaid, or unemployed), age, gender (male or female), and marital status (married, unmarried, or widowed/bereaved). Income is a strong predictor of subjective well-being (Diener and Seligman Citation2004); its significance is not assumed to be absolute but relative, depending on the income level of society (Wolbring, Keuschnigg, and Negele Citation2013). As the EVS and WVS collected information on relative income, I used relative income as an independent variable after standardizing its values to 1–11. Considering that previous studies have noted that freedom is significantly associated with subjective well-being (Graafland Citation2019; Minkov, Welzel, and Schachner Citation2020; Welsch Citation2003), this study also uses the sense of freedom as an independent variable. In the EVS and WVS, the sense of freedom was calculated using a 10-point Likert scale based on the following inquiry: ‘Some people feel they have completely free choice and control over their lives, and other people feel that what they do has no real effect on what happens to them. Please use the scale to indicate how much freedom of choice and control you feel you have over the way your life turns out.’ Furthermore, as previous studies have suggested that some demographic variables are relevant to subjective well-being, including employment status (Clark and Oswald Citation1994), age (Yang Citation2008), gender (Stevenson and Wolfers Citation2009), and marital status (Waite and Gallagher Citation2000), I treated them as independent variables in the statistical models of this study.

Analytic strategy

To specify the latent structure of relationships between life satisfaction, economic affluence, and democracy at the individual level, this study analyzed data from the EVS and WVS using finite mixture models as a type of a latent class regression model (Grün and Leisch Citation2015; Citation2007; Leisch Citation2004). Finite mixture modeling assumes that there are latent groups within a population, and a dependent variable for each one is predicted by a different regression model for each latent group. For instance, a population can be divided into two latent groups: a group with materialist values and that with post-materialist values. The group to which a respondent belongs is probabilistically determined and life satisfaction is predicted using different regression models for each group. Specifically, respondents’ life satisfaction with materialist values is predicted using socioeconomic status, whereas that with post-materialist values is predicted using their sense of freedom. Finite mixture modeling can be represented by the following probabilistic model that combines two or more density functions:

(1)

(1) where

represents a dependent variable from

distinct latent classes

in ratios

;

refers to the conditional probability density function for the dependent variable in the

th class model;

means independent variable’s vector; and

means coefficient’s vector in the

th class model.

Furthermore, to examine changes in national life satisfaction, this study analyzed data from the EVS and WVS using fixed effects regression models, a method for analyzing panel data. The fixed effects regression model predicts the difference in a dependent variable from the average of the dependent variable between time points using the differences in independent variables from the average of independent variables between time points. As such, all influences of time-invariant variables can be controlled. Hence, the fixed effects regression model can be written as follows:

(2)

(2) where

represents an individual,

represents a time point,

represents a dependent variable,

represents an intercept for each time point,

represents a vector of time-variant variable’s coefficients,

represents time-variant variable’s vector,

represents a vector of time-invariant variable’s coefficients,

represents time-invariant variable’s vector,

represents an intercept for each case, and

represents an error term. Moreover, this equation can be rewritten as follows:

(3)

(3)

To estimate the coefficients and proportions of latent classes in finite mixtures of regression models, this study utilized the R software and its flexmix package (Core Team Citation2018; Grün and Leisch Citation2015; Leisch Citation2004). Similarly, for estimating coefficients of time-variant variables in fixed effects models, the plm package was employed (Croissant and Millo Citation2008). If the statistically positive association between democracy and life satisfaction and the statistically positive association between economic prosperity and life satisfaction are observed, Hypothesis 1 will be supported. Furthermore, if statistically significant and negative association between democratization and economic development is observed, Hypothesis 2 will be supported. Finally, if statistically significant and negative association between emerging post-materialist values and economic development is observed, Hypothesis 3 will be supported.

Results

Descriptive statistics

First, this study recorded descriptive statistics for the target variables. presents the descriptive statistics of the targeted variables at the individual level. Europeans are more likely to be satisfied with their lives and to hold a high sense of freedom. However, the standard deviations were greater than 2.00, indicating that the inequality of life satisfaction and sense of freedom among European people were relatively high.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Variables at the Individual Level.

presents the descriptive statistics for the target variables at the country level. The numbers of countries for each variable were not identical because of missing values for each variable (especially GDP per capita). The minimum (maximum) value of average life satisfaction was 4.68 (8.37). These large differences in national life satisfaction among European countries seemed to imply that differences in social contexts might account for the significant differences in life satisfaction among European countries.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Variables at the Country Level.

As independent variables at the country level, LDI and GDP per capita [log] were treated. They had a statistically significant and positive correlation with each other (r = 0.512, p < 0.001). Therefore, if LDI and GDP per capita affect national life satisfaction simultaneously, their interactions should be considered.

Results of finite mixture regression models

shows the results of the finite mixture regression models for individual life satisfaction based on pooled data from the EVS from Waves 1–5 and WVS Wave 7. Model 1 in represents a simple-regression model that does not consider the differences between latent groups. Conversely, Model 2 in incorporates differences between two latent groups: Classes 1 and 2. With reference to the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) values, Model 2 was deemed more appropriate for the data compared to Model 1. Therefore, the assumption that European people could be categorized into distinct latent groups was supported.

Table 3. Results of Finite Mixture Regression Models Predicting Life Satisfaction.

Next, this study examined the differences in the coefficients of the independent variables between two latent groups: Classes 1 and 2. Consequently, most directions of the independent variables’ coefficients were the same. Therefore, the social mechanisms producing life satisfaction in Classes 1 and 2 were not significantly different. Nevertheless, comparing the coefficients regarding life satisfaction for each independent variable revealed differences in the association with the independent variables and life satisfaction between the two latent groups.

This study focuses on household income and sense of freedom. For household income, the coefficient value in Class 1 (0.018, se = 0.002) was smaller than that in Class 2 (0.119, se = 0.003). This indicated that respondents belonging to Class 2 tended to consider household income when judging their life satisfaction. Conversely, although respondents belonging to Class 1 did not ignore household income when judging their life satisfaction, they were less likely to consider household income compared to those belonging to Class 2. This implied that the respondents of Class 2 tended to consider materialist values more than those of Class 1.

For sense of freedom, the coefficient value in Class 1 (0.951, se = 0.002) was larger than that in Class 2 (0.130, se = 0.004). This indicated that respondents belonging to Class 1 were more likely to emphasize their freedom while judging their life satisfaction. Conversely, although the respondents of Class 2 considered their freedom when judging their life satisfaction, they were less likely to emphasize it than those of Class 1. Put simply, respondents belonging to Class 1 tended to consider post-materialist values (Abramson and Inglehart Citation1987; Inglehart Citation1971; Inglehart Citation2008; Inglehart, Ponarin, and Inglehart Citation2017) more than those belonging to Class 2.

Finally, this study compared the demographic traits of the two latent groups: socioeconomic status, sense of freedom, and life satisfaction. presents descriptive statistics for each latent class. Between Classes 1 and 2, most variables (except for gender) exhibited significantly different means/ratios. However, demographic traits and socioeconomic status showed no large differences. In other words, Classes 1 and 2 exhibited similar demographic and socioeconomic structures. Nevertheless, the means of life satisfaction and sense of freedom were remarkably different between Classes 1 and 2. Class 1 displayed higher means of life satisfaction and a sense of freedom than Class 2.

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics by Latent Class.

Differences in the means of life satisfaction and sense of freedom between Classes 1 and 2 reflect differences in the associations with social values. Because respondents belonging to Class 2, who tended to consider materialist values, had a lower sense of freedom and life satisfaction, materialist values might be negatively correlated to their life satisfaction. Conversely, respondents belonging to Class 1, who tended to consider post-materialist values, had a higher sense of freedom and life satisfaction; thus, post-materialist values might be positively correlated to life satisfaction. As Classes 1 and 2 involved similar social class groups, the associations with social values (materialist values or post-materialist values) and life satisfaction were independent of demographic traits and socioeconomic status.

Results of fixed effects models

Concerning the results of the finite mixture regression models, this study analyzed the relationships with other variables at the country level (N = 149). shows how these variables at the country level are associated with each variable. At the country level, the sense of freedom and life satisfaction were significantly and positively associated with each country’s GDP per capita, LDI, and portion of Class 1. Moreover, portion of Class 1, GDP per capita, and LDI were significantly associated, except for the association with the portion of Class 1 and LDI. This implies that the associations with GDP per capita, LDI, portion of Class 1, and national life satisfaction may be overlapped by each factor.

Table 5. Correlation Matrix of Variables at the Country Level.

presents the results of fixed effects regression models on national life satisfaction. Based on Model 1 in , changes in portion of Class 1 were associated with changes in national life satisfaction. However, Model 2 in shows that the association with changes in portion of Class 1 and those in national life satisfaction is mediated by changes in GDP per capita. Moreover, Models 3 and 4 revealed that the association between changes in GDP per capita and changes in national life satisfaction weakened with increasing LDI. Based on the values of AIC and BIC, Model 3 was better fitted to the data from the EVS and WVS as a model predicting changes in national life satisfaction compared to Models 1, 2, and 4. Additionally, as the result of the Shapiro – Wilk normality test for Model 3 does not reject the null hypotheses (0.979, p > 0.100), the residuals of Model 3 are said to follow a normal distribution. Thus, Model 3 confirms that the coefficient of changes in LDI depends on changes in GDP per capita [log].

Table 6. Results of Fixed Effects Regression Models Predicting for Changes in Average Life Satisfaction at the Country Level.

illustrates the changes in marginal effects. The marginal effect of changes in LDI depending on GDP per capita [log] and the marginal effect of changes in GDP per capita [log] depending on LDI are estimated using Model 3 in . shows that the marginal effect of changes in LDI on changes in national life satisfaction declines with rising GDP per capita [log], although the marginal effect of changes in LDI is positive in non-economically growing countries. Put simply, democratization did not have the same meaning for European people across countries concerning subjective well-being. In economically developed countries, contrariwise to their economically developing counterparts, ceteris paribus, democratization did not significantly influence changes in national life satisfaction. Consequently, if the association between democratization and economic development were overlooked, democratization would not seem to be substantially correlated to changes in national life satisfaction. However, it was significantly correlated with changes in national life satisfaction in economically developing countries.

Figure 2. Marginal Effects of Changes in LDI and GDP per Capita on Changes in Average Life Satisfaction at the Country Level. X = LDI, Y = Marginal Effect of Changes in GDP per capita [log] (top). X = GDP [log], Y = Marginal Effect of Changes in LDI (bottom).

![Figure 2. Marginal Effects of Changes in LDI and GDP per Capita on Changes in Average Life Satisfaction at the Country Level. X = LDI, Y = Marginal Effect of Changes in GDP per capita [log] (top). X = GDP [log], Y = Marginal Effect of Changes in LDI (bottom).](/cms/asset/fc1fdd4f-6b71-457f-a2f1-b0dae5f58334/rdsr_a_2366251_f0002_oc.jpg)

Moreover, changes in the proportion of individuals with post-materialist values (Class 1) were observed to be associated with changes in national life satisfaction. However, after controlling for changes in economic prosperity and democratization, the significance of the association between shifting to post-materialist values and changes in national subjective life satisfaction disappeared (as shown in Models 1 and 2, ). These results imply not only that the association between post-materialist values and national subjective well-being is not simple but also that social changes mediate the connection between shifting to post-materialist values and changes in national life satisfaction. Unlike changes in LDI, those in economic prosperity had statistically significant associations with changes in national life satisfaction (Model 2, ). Therefore, a shift from materialist to post-materialist values is assumed to be directly associated with changes in a country’s economic prosperity. However, as the association between democratization and shifting from materialist to post-materialist values was statistically significant, democratization had an indirect association with shifting to post-materialist values (Models 3 and 4, ).

Summary

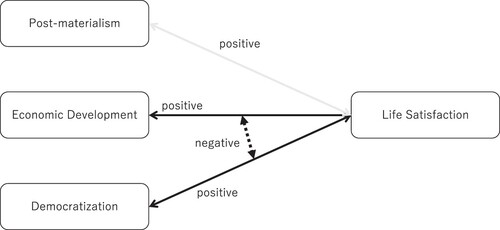

summarizes the analytical results regarding the factors related to national life satisfaction.

First, the results of the fixed effects models on changes in national life satisfaction indicated that respondents residing in economically growing countries were more likely to report higher levels of life satisfaction. Similarly, the findings revealed that residents of more democratic countries tended to experience greater average life satisfaction. These findings support Hypothesis 1. Both economic development and democratization were significantly associated with changes in national subjective well-being. However, the association between economic development and national life satisfaction and the association between democratization and national life satisfaction were negatively correlated.

Results of the fixed effects models predicting changes in national life satisfaction also demonstrate that the association between democratization and changes in national life satisfaction was negatively related to the association between economic development and changes in national life satisfaction. Consequently, the positive correlation between democratization and changes in national life satisfaction could not be observed in economically growing European countries. By contrast, this correlation was observed in non-economically growing countries. This finding supports Hypothesis 2.

Finally, the results of the finite mixture regression models predicting national life satisfaction revealed that the model assuming different latent groups was more suitable for data from the EVS and WVS Wave 7 than the model that did not assume differences between latent groups. Furthermore, members of one latent group were more likely to consider their socioeconomic status when judging their life satisfaction. Conversely, members of the other latent group were more likely to consider the sense of freedom and less likely to consider socioeconomic status when judging their life satisfaction. The former group could be characterized by materialist values, and post-materialist values could express the latter. However, the association between shifting to post-materialist values and changes in national life satisfaction disappeared after controlling for the correlation of economic development, democratization, and changes in national life satisfaction; thus, Hypothesis 3 was not supported.

Discussion and conclusions

This study examined the association between democracy, economic prosperity, and national life satisfaction based on data from the EVS and WVS Wave 7. The results of the analyses based on finite mixture regression models revealed that respondents of the EVS and WVS Wave 7 could be divided into two latent groups: one with materialist values and the other with post-materialist values. Moreover, the results of the analyses based on fixed effects regression models showed that the associations between emerging post-materialist values and changes in national life satisfaction had been correlated with economic development and democratization. Shifting from materialist to post-materialist values was positively related to changes in national life satisfaction. However, the association between having post-materialist values and enhancing national life satisfaction was mediated by social change.

The results of the fixed effects regression models, without considering the interaction between democratization and economic development, demonstrated that only economic development accounted for changes in national life satisfaction during the 1981–2022 period in European countries. Economic development had a statistically significant and positive association with changes in national life satisfaction. In the models considering the association between democratization and economic development, economic development and democratization showed a statistically significant and positive association with national life satisfaction. Accordingly, the positive association between democratization and national life satisfaction is canceled out by the negative association between democratization and economic development. Suppose that social researchers do not pay careful attention to the complicatedness of the relationships between democratization, economic development, and changes in national life satisfaction. In that case, they will overlook the role of democratization in changing national subjective well-being. Democratization has a significant positive correlation with changes in national life satisfaction; however, it can be offset by negative interaction with economic development. This implies that Europeans consider a sound democratic regime as a tool for their countries to become affluent. Therefore, after achieving sufficient economic development at the country level, democratization lost its significance for Europeans as a tool to become wealthy countries.

Conversely, the role of economic development on changes in average life satisfaction should not be overestimated. Although economic development is considerably correlated with national life satisfaction, this correlation is inconsistent. The association with economic development and changes in national life satisfaction differs between democratic and non-democratic countries (Böckerman, Laamanen, and Palosaari Citation2016; Zagrebina Citation2018). Furthermore, the degree of its association varies depending on social values and contexts (Delhey Citation2010). Therefore, economic development is just one of the many ways to improve the subjective quality of people’s lives (York and Bell Citation2014).

Similarly, the role of democracy pertaining to changes in national life satisfaction should not be underestimated. Without considering the negative interaction between economic development and democratization, the association with democratization and changes in national life satisfaction could be overlooked. However, considering their negative interaction, it is possible to find a considerable association between democratization and changes in national life satisfaction. The relationship between economic development and democratization is neither complementary nor competitive. Democracy, as a tool, is expected to improve the economic development of Europeans, but economic development is not likely to lead to a sound democratic regime. Therefore, the relationship between economic development, democratization, and changes in national life satisfaction becomes complicated.

Finally, the association with shifting to post-materialist values and changes in national life satisfaction should not be overlooked. Although the association between shifting to post-materialist values and changes in national life satisfaction is mediated by social changes such as economic development and democratization, these factors can still be correlated with improving people’s subjective well-being. Members of the group with post-materialist values, who tend to consider freedom rather than household income when deciding their life satisfaction, tend to be more satisfied with their lives than those with materialist values. In other words, as economic development weakens the association with changes in national life satisfaction, the appearance of post-materialist values might be correlated with improving people’s subjective well-being.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it focuses only on European countries where the idea of democracy has been relatively widely accepted. Therefore, this study’s findings cannot be applied to other countries in the same manner; for instance, future studies should examine whether they can be applied to East Asian countries, where authoritarianism is widespread. The possibility that different social mechanisms generate subjective national well-being in East Asian countries cannot be denied. Nevertheless, the negative relationships found in this study between economic development and democratization provide some critical insights into how national subjective well-being changes in other countries.

Second, although the EVS and WVS contain high-quality social survey data, they are incomplete datasets for European countries between 1981 and 2022. Specifically, the number of countries included in each wave differ. Therefore, while some countries have survey data for all six waves, many have survey data for fewer than six waves. To trace the changes in national life satisfaction between 1981 and 2022 among European countries, this problem cannot be overlooked. To correctly estimate changes in social values and subjective well-being in European countries, this study’s findings must be supported by the results of other social data related to European countries’ social values and subjective well-being.

Third, the social indicators used in this study may have been insufficient. In this study, only one item (i.e. life satisfaction) was used as an index of subjective well-being. Moreover, only GDP per capita was treated as an index of economic development, and only LDI was treated as an index of democratization. Owing to data restrictions, it was impossible to increase the social indicators in the models implemented in this study. Future studies should include more social indicators to specify the complicated relationships between economic development, democratization, and changes in national subjective well-being. By doing so, social researchers can contribute to the realization of high-quality national subjective well-being.

Lastly, the relationship between economic development, democratization, and national life satisfaction is also more complicated and depends on various social contexts, which are ignored in this study (social welfare regime, level of quality of healthcare service, international relationships, and so on). Therefore, in the future, it is important to specify the effects of confounding factors on their associations with economic development, democratization, and national life satisfaction.

Declarations

(i) There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

(ii) All procedures performed in this study was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

(iii) The European Values Study used in this study had been conducted by the European Values Study (https://europeanvaluesstudy.eu/) and opens to public by the European Values Study.

Availability of data used in this study

The EVS and WVS data are available to researchers via each official website (https://europeanvaluesstudy.eu, https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/) and are fully anonymized. The EVS data were accessed for research purposes on July 25, 2022, while the WVS data were accessed on April 22, 2024.

Availability of code used in this study

Contact the corresponding author. He will notify the GitHub repository to confirm the code.

7_Supplimental_Material

Download MS Excel (11.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abramson, Paul R, and Ronald Inglehart. 1987. “Generational Replacement and the Future of Post-Materialist Values.” The Journal of Politics 49 (1): 231–241. https://about.jstor.org/terms.

- Alderson, Arthur S., and Tally Katz-Gerro. 2016. “Compared to Whom? Inequality, Social Comparison, and Happiness in the United States.” Social Forces 95 (1): 25–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sow042.

- Berggren, Niclas, Christian Bjørnskov, and Therese Nilsson. 2018. “Do Equal Rights for a Minority Affect General Life Satisfaction?” Journal of Happiness Studies 19 (5): 1465–1483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9886-6.

- Böckerman, Petri, Jani Petri Laamanen, and Esa Palosaari. 2016. “The Role of Social Ties in Explaining Heterogeneity in the Association Between Economic Growth and Subjective Well-Being.” Journal of Happiness Studies 17 (6): 2457–2479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9702-0.

- Christmann, Pablo, and Mariano Torcal. 2017. “The Political and Economic Causes of Satisfaction with Democracy in Spain–a Twofold Panel Study.” West European Politics 40 (6): 1241–1266. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1302178.

- Clark, Andrew E, and Andrew J Oswald. 1994. “Unhappiness and Unemployment.” The Economic Journal 104 (424): 648–659. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2234639.

- Croissant, Yves, and Giovanni Millo. 2008. “Panel Data Econometrics in R: The Plm Package.” Journal of Statistical Software 27 (2): 1–43. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v027.i02.

- Daoust, Jean François, and Richard Nadeau. 2021. “Context Matters: Economics, Politics and Satisfaction with Democracy.” Electoral Studies 74 (December), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102133.

- Delhey, Jan. 2010. “From Materialist to Post-Materialist Happiness? National Affluence and Determinants of Life Satisfaction in Cross-National Perspective.” Social Indicators Research 97 (1): 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9558-y.

- Delhey, Jan, and Georgi Dragolov. 2014. “Why Inequality Makes Europeans Less Happy: The Role of Distrust, Status Anxiety, and Perceived Conflict.” European Sociological Review 30 (2): 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jct033.

- Diener, Ed, and Martin E.P. Seligman. 2004. “Beyond Money.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 5 (1): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00501001.x.

- Dorn, David, Justina A.V. Fischer, Gebhard Kirchgässner, and Alfonso Sousa-Poza. 2007. “Is It Culture or Democracy? The Impact of Democracy and Culture on Happiness.” Social Indicators Research 82 (3): 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-006-9048-4.

- Dorn, David, Justina A.V. Fischer, Gebhard Kirchgässner, and Alfonso Sousa-Poza. 2008. “Direct Democracy and Life Satisfaction Revisited: New Evidence for Switzerland.” Journal of Happiness Studies 9 (2): 227–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-007-9050-9.

- Easterlin, Richard A. 1974. “Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some Empirical Eevidence.” In Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramovitz, edited by P. A. David and, and M. W. Reder, 89–125. New York: Academic Press.

- Easterlin, Richard A. 1995. “Will Raising the Incomes of All Increase the Happiness of All?” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 27 (1): 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(95)00003-B

- Easterlin, Richard A. 2001. “Income and Happiness : Towards a Unified Theory.” The Economic Journal 111 (473): 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00646

- Easterlin, Richard A., Laura A. McVey, Malgorzata Switek, Onnicha Sawangfa, and Jacqueline S. Zweig. 2010. “The Happiness-Income Paradox Revisited.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (52): 22463–22468. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1015962107.

- Ekici, Tufan, and Selda Koydemir. 2014. “Social Capital, Government and Democracy Satisfaction, and Happiness in Turkey: A Comparison of Surveys in 1999 and 2008.” Social Indicators Research 118 (3): 1031–1053. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0464-y.

- European Values Study. 2022. European Values Study 2017: Integrated Dataset (EVS2017). Cologne: GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13897.

- Frey, Bruno S, and Alois Stutzer. 2000. “Happiness Prospers in Democracy.” Journal of Happiness Studies 1 (1): 79–102. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010028211269.

- Gardarsdottir, Ragna B., Rod Bond, Arndis Vilhjalmsdottir, and Helga Dittmar. 2018. “Shifts in Subjective Well-Being of Different Status Groups: A Longitudinal Case-Study during Declining Income Inequality.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 54 (June 2017): 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2018.03.002.

- Graafland, Johan. 2019. “When Does Economic Freedom Promote Well Being? On the Moderating Role of Long-Term Orientation.” Social Indicators Research 149: 127–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02230-9.

- Graafland, Johan, and Bart Compen. 2015. “Economic Freedom and Life Satisfaction: Mediation by Income per Capita and Generalized Trust.” Journal of Happiness Studies 16 (3): 789–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9534-3.

- Graafland, Johan, and Bjorn Lous. 2018. “Economic Freedom, Income Inequality and Life Satisfaction in OECD Countries.” Journal of Happiness Studies 19 (7): 2071–2093. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9905-7.

- Graham, Carol, and Stefano Pettinato. 2001. “Happiness, Markets, and Democracy: Latin America in Comparative Perspective.” Social Indicators Research 2: 237–268.

- Grün, Bettina, and Friedrich Leisch. 2007. “Fitting Finite Mixtures of Generalized Linear Regressions in R.” Computational Statistics and Data Analysis 51 (11): 5247–5252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2006.08.014.

- Grün, Bettina, and Friedrich Leisch. 2015. “FlexMix Version 2: Finite Mixtures with Concomitant Variables and Varying and Constant Parameters.” Journal of Statistical Software 28 (4): 1–35. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v028.i04.

- Haerpfer, C., R. Inglehart, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano , M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin, and B. Puranen. 2022. World Values Survey: Round Seven–Country-Pooled Datafile. Madrid, Spain & Vienna, Austria. https://doi.org/10.14281/18241.20.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1971. “The Silent Revolution in Europe: Intergenerational Change in Post-Industrial Societies.” American Political Science Review 65 (4): 991–1017. https://doi.org/10.2307/1953494

- Inglehart, Ronald F. 2008. “Changing Values among Western Publics from 1970 to 2006.” West European Politics 31 (1-2): 130–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380701834747.

- Inglehart, Ronald F., Eduard Ponarin, and Ronald C. Inglehart. 2017. “Cultural Change, Slow and Fast: The Distinctive Trajectory of Norms Governing Gender Equality and Sexual Orientation.” Social Forces 95 (4): 1313–1340. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sox008.

- Leisch, Friedrich. 2004. “FlexMix: A General Framework for Finite Mixture Models and Latent Class Regression in R.” Journal of Statistical Software 11 (8): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v011.i08.

- Loveless, Matthew, and Chiara Binelli. 2020. “Economic Expectations and Satisfaction with Democracy: Evidence from Italy.” In Government and Opposition. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2018.31.

- Minkov, Michael, Christian Welzel, and Michael Schachner. 2020. “Cultural Evolution Shifts the Source of Happiness from Religion to Subjective Freedom.” Journal of Happiness Studies, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00203-w.

- Orviska, Marta, Anetta Caplanova, and John Hudson. 2014. “The Impact of Democracy on Well-Being.” Social Indicators Research 115 (1): 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-9997-8.

- Ott, Jan C. 2010. “Good Governance and Happiness in Nations: Technical Quality Precedes Democracy and Quality Beats Size.” Journal of Happiness Studies 11 (3): 353–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-009-9144-7.

- Pacek, Alexander, Benjamin Radcliff, and Mark Brockway. 2019. “Well-Being and the Democratic State: How the Public Sector Promotes Human Happiness.” Social Indicators Research 143 (3): 1147–1159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2017-x.

- Quaranta, Mario, and Sergio Martini. 2016. “Does the Economy Really Matter for Satisfaction with Democracy? Longitudinal and Cross-Country Evidence from the European Union.” Electoral Studies 42 (June): 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.02.015.

- Quaranta, Mario, and Sergio Martini. 2017. “Easy Come, Easy Go? Economic Performance and Satisfaction with Democracy in Southern Europe in the Last Three Decades.” Social Indicators Research 131 (2): 659–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1270-0.

- R Core Team. 2018. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: http://www.R-project.org/. http://www.r-project.org/.

- Radcliff, Benjamin, and Gregory Shufeldt. 2016. “Direct Democracy and Subjective Well-Being: The Initiative and Life Satisfaction in the American States.” Social Indicators Research 128 (3): 1405–1423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1085-4.

- Rode, Martin. 2013. “Do Good Institutions Make Citizens Happy, or Do Happy Citizens Build Better Institutions?” Journal of Happiness Studies 14 (5): 1479–1505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9391-x.

- Schneider, Simone M. 2019. “Why Income Inequality Is Dissatisfying – Perceptions of Social Status and the Inequality-Satisfaction Link in Europe.” European Sociological Review 35 (3): 409–430. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcz003.

- Schröder, Martin. 2016. “How Income Inequality Influences Life Satisfaction: Hybrid Effects Evidence from the German SOEP.” European Sociological Review 32 (2): 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv136.

- Schyns, Peggy. 1998. “Crossnational Differences in Happiness: Economic and Cultural Factors Explored.” Social Indicators Research 43 (1/2): 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006814424293.

- Simone, Elina De, Lorenzo Cicatiello, Giuseppe Lucio Gaeta, and Mauro Pinto. 2022. “Expectations About Future Economic Prospects and Satisfaction with Democracy: Evidence from European Countries during the COVID-19 Crisis.” Social Indicators Research 159 (3): 1017–1033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02783-8.

- Spruk, Rok, and Aleskandar Kešeljević. 2016. “Institutional Origins of Subjective Well-Being: Estimating the Effects of Economic Freedom on National Happiness.” Journal of Happiness Studies 17 (2): 659–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9616-x.

- Stadelmann-Steffen, Isabelle, and Adrian Vatter. 2012. “Does Satisfaction with Democracy Really Increase Happiness? Direct Democracy and Individual Satisfaction in Switzerland.” Political Behavior 34 (3): 535–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-011-9164-y.

- Stevenson, Betsey, and Justin Wolfers. 2009. “The Paradox of Declining Female Happiness.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 1 (2): 190–225. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.

- Sullivan, Gail M., and Anthony R. Artino. 2013. “Analyzing and Interpreting Data From Likert-Type Scales.” Journal of Graduate Medical Education 5 (4): 541–542. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-5-4-18.

- The World Bank. 2022. “World Bank Open Data.” The World Bank Group. 2022.

- Varieties of Democracy. 2022. “V-Dem Dataset Version 12.” Https://Www.v-Dem.Net/Vdemds.Html. June 17, 2022.

- Waite, Linda, and Maggie Gallagher. 2000. The Case for Marriage: Why Married People Are Happier, Healthier, and Better Off Financially. New York: DoubleDay.

- Welsch, Heinz. 2003. “Freedom and Rationality As Predictors of Cross-National Happiness Patterns :.” Journal of Happiness Studies 4 (3): 295–321. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026249123711

- Wilkinson, Richard G. 2005. The Impact of Inequality: How to Make Sick Societies Healthier. New York: The New Press.

- Wilkinson, Richard, and Kate Pickett. 2010. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. London: Allen Lane.

- Wolbring, Tobias, Marc Keuschnigg, and Eva Negele. 2013. “Needs, Comparisons, and Adaptation: The Importance of Relative Income for Life Satisfaction.” European Sociological Review 29 (1): 86–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcr042.

- Yang, Yang. 2008. “Social Inequalities in Happiness in the United States, 1972 to 2004: An Age-Period-Cohort Analysis.” American Sociological Review 73 (2): 204–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240807300202

- York, Richard, and Shannon Elizabeth Bell. 2014. “Life Satisfaction across Nations: The Effects of Women’s Political Status and Public Priorities.” Social Science Research 48: 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.05.004.

- Zagrebina, Anna. 2018. “Ideas of Subjective Well-Being in Democratic and Nondemocratic Societies: A Comparative Study.” Comparative Sociology 17 (1): 70–99. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691330-12341450.