Abstract

Search engines are an absolutely central part of the web. Yet we know relatively little about how they shape news consumption. In this study, we use survey data from four countries (UK, USA, Germany, Spain) to compare the news repertoires of those who say they use search engines to search for news stories, and those that do not. In all four countries, and controlling for other factors, we show that those who find news via search engines (i) on average use more sources of online news, (ii) are more likely to use both left-leaning and right-leaning online news sources, and (iii) have more balanced news repertoires in terms of using similar numbers of left-leaning and right-leaning sources. We thus find little support for the idea that search engine use leads to echo chambers and filter bubbles. To the contrary, using search engines for news is associated with more diverse and more balanced news consumption, as search drives what we call “automated serendipity” and leads people to sources they would not have used otherwise.

Introduction

Historically, most news use was based on people going directly to television, print, or radio news sources. But online, people increasingly rely on distributed discovery and arrive at news content via various digital intermediaries, including search engines, social media, messenger apps, and news aggregators (Newman et al. Citation2017; Nielsen and Ganter Citation2018). The move from a world where most news consumption was based on self-selection, to one where news use is increasingly characterised by algorithmic selection, has prompted speculation about the potential for citizens to unwittingly find themselves in echo chambers and filter bubbles, with news audience fragmentation and political polarization among the possible consequences (Pariser Citation2011; Sunstein Citation2017). This narrative has had a profound impact upon the popular understanding of digital intermediaries. Yet an equally plausible, and not necessarily mutually exclusive scenario, is one where algorithmic selection exposes people to news and information they would not have come across had they been reliant on self-selection alone, with the effect of expanding their news repertoires, rather than narrowing them.

When considering how digital intermediaries and algorithmically-driven services are reshaping news use across the world, it is sometimes tempting to think primarily (or perhaps solely) about social media. Yet, search engines like Google, Yahoo!, and Bing are among the most widely-used web services in the world, and are used for news by a significant minority (between around 10 and 25%) in many countries (Newman et al. Citation2017). Just like social media, search engines rely on ranking algorithms that respond to users’ behaviour based on automated inferences about what they will find most relevant. This means that they also have the potential to trap people inside echo chambers and filter bubbles (Hannák et al. Citation2013; Puschmann Citation2017). Despite this, only a handful of recent studies have investigated the impact that using search engines might have on news use.

Here, we use 2017 Reuters Institute Digital News Report data from four countries (UK, USA, Germany, and Spain) to compare differences in individual news repertoires between two groups: those that use search engines to search for news topics, and those that do not. More specifically, we compare differences in the number of online news sources used by each group, differences in the proportion that consume news from both left-leaning and right-leaning sources, and differences in the balance between left-leaning and right-leaning sources. By focusing on the political leaning of different news sources, we more directly address the underlying concerns over echo chambers and filter bubbles. After all, using more sources of news is only an indication of a more diverse news repertoire if the sources in fact represent different views, rather than simply more of the same.

In all four countries, we find that people who use search engines for news: (i) on average use more sources of online news, (ii) are more likely to use both left-leaning and right-leaning online news sources, and (iii) in three out of four countries have more balanced news repertoires in terms of using similar numbers of left-leaning and right-leaning sources. We therefore argue that search engines, at least in their current form, are a source of what we call “automated serendipity.” By automated serendipity, we mean forms of algorithmic selection that expose people to news sources they would not otherwise have used. This concept is distinct from incidental exposure (where people are shown news whilst doing other things), because it describes what people are exposed to, rather than whether they are exposed to it or not, and because it can occur as part of intentional news exposure or when people are exposed to news incidentally.

Literature Review

Many social networks, search engines, and news aggregators, are heavily reliant on algorithms in order to make filtering decisions at a large scale. As Gillespie (Citation2014) has argued, using algorithms to filter information constitutes a new knowledge logic, where proceduralized choices are used as a proxy for human judgement. This can be contrasted with an editorial logic based on the individualised and institutionalised subjective judgements of experts. Different search engines deploy different proceduralized choices, and how they operate, display results, and are used, continues to evolve. Google Search, for example, uses many different signals to deliver personalized results, starting from the search query, the estimated “authority” of indexed web pages, and has—since the introduction of “personalized results” in 2005 (Google Citation2005)—increasingly integrated signals based on data specific to individual users, including preferences inferred from what they have clicked on in the past (Google n.Citationd.).

Such automated action at scale enables intermediaries like Facebook and Google to make billions of display decisions in real-time, thus making social media and search engines as we know them possible. But it has also prompted fears over the possible emergence of echo chambers and filter bubbles. Though these concerns are subtly different, both are rooted in the idea that ever more responsive algorithmic selection will narrow the range of information people are exposed to. With filter bubbles, the idea is that certain information will be hidden from people, either because it is deemed unpopular, of low quality, or does not match with the preferences, interests, and beliefs inferred from their past behaviour (Pariser Citation2011). Echo chambers, on the other hand, result from people being over-exposed to information due to the same mechanisms, with the effect of reinforcing their existing beliefs and creating a false impression of the extent to which those views are shared by the population as a whole. If realised, echo chambers and filter bubbles could produce or worsen outcomes—such as political polarization and the fragmentation of audiences—that most people think of as undesirable.

These concerns have prompted research into the influence of digital intermediaries on information exposure. The majority of these studies have focused on social media, and most have found that on average most people tend to be exposed to a relatively high degree of politically cross-cutting news, thus challenging the existence of filter bubbles or echo chambers (Zuiderveen Borgesius et al. Citation2016). One possible reason for this is that social media is associated with “incidental exposure” to news, where people use social media for reasons that have little to do with news, but while doing so are nonetheless exposed to news content (Boczkowski, Mitchelstein, and Matassi Citation2018). Fletcher and Nielsen (Citation2018) found that people who unintentionally use social media for news use more online news sources than people who do not use social media at all, with the boost from social media even stronger for younger people and those with low interest in news. Put differently, incidental exposure to news on social media expands people’s news repertoires.

A news repertoire is simply the set of news sources an individual uses on a regular basis. Media and communication scholars have long understood that people do not consume news from the full range of available outlets, but instead form repertoires consisting of a small subset of news sources they like, or are most readily available (see Taneja, Webster, and Malthouse Citation2012 for an overview). Repertoires are partly shaped by structural factors such as the availability of technologies, so as people change the ways they discover news online, changes to news repertoires are likely to follow.

There has been little research into how search engines shape news consumption, or more specifically, how they shape news repertoires. This is partly because studying search engines is particularly challenging (Ørmen Citation2015). One option is to examine search results. Studies typically find that search results generated by the same query often differ, but primarily because of geo-location (Hannák et al. Citation2013). Such differences can be important, but they are not directly related to concerns over political or ideological segregation that underpin talk of filter bubbles and echo chambers. Other studies have focused on the effects of search engine use. Flaxman et al. (Citation2016) analysed the web histories of 50,000 people in the US, and found that search engine (and social media) use was associated with increased individual exposure to material from the opposite side of the political spectrum. Nikolov et al. (Citation2015) examined more than 100 million clicks from over 100,000 users in the US from 2006 to 2010, finding that people access a significantly broader range of sources through search than through social media. Dutton et al. (Citation2017) used survey data from seven high income democracies to show that search is among an array of media consulted, especially by those interested in politics, and that most online news users are not trapped in a bubble on a single platform. There have been various other studies of the role of search in finding information about politicians and the like (e.g. Diakopoulos et al. Citation2018), as well of studies of related services such as Google News (e.g. Haim, Graefe, and Brosius Citation2017; Nechushtai and Lewis, Citationforthcoming), but no other studies of searching for news that we are aware of.

We aim to build upon research into the effects of using search engines for news by examining people’s news repertoires in more detail. We also use survey data to control for other factors including both socio-economic status indicators like age, gender, education, and income as well as attitudinal and behavioural variables like interest in news, political leaning, and use of other intermediaries like social media or news aggregators.

Hypotheses

First, because search engines offer the potential to expose users to additional news sources, we hypothesize that those who use search engines to search for news topics will end up using more sources of online news:

H1. Those who use search engines to search for news topics will use more sources of online news than those who do not.

Using more online news sources does not guarantee a more diverse news repertoire, particularly if people end up consuming more news from sources that have the same political perspective. However, because previous studies have shown that people who rely on digital intermediaries are in fact exposed to more politically cross-cutting news, we hypothesize that those who use search engines for news will be more likely to use at least one news source from both sides of the political spectrum:

H2. Those who use search engines to search for news topics will be more likely to use at least one left-leaning and one right-leaning online news source than those who do not.

Though we expect increased news exposure to increase diversity in this simple sense, it still seems probable that—because personalization based on past behaviour is an increasingly important part of how search functions—the increase in exposure would be biased towards individual preferences. In other words, though someone who uses search might indeed be exposed to some news from sources that do not match their preferences, they would be more exposed to news from sources that do. Therefore, we hypothesize that search engine users have more imbalanced news repertoires, meaning they use either disproportionately more right-leaning or left-leaning sources:

H3. Those who use search engines to search for news topics will be less likely to use a similar number of left-leaning and right-leaning online news sources than those who do not.

Data

Our data come from the 2017 Reuters Institute Digital News Report survey (Newman et al. Citation2017). The survey was conducted by YouGov in partnership with the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford in early February 2017. An online instrument was used to survey around 2000 people in 36 countries. Respondents were drawn from panels within each country, with people invited to complete the survey based on interlocking quotas for age group, gender, and region, to construct nationally representative samples. The strengths and weaknesses of this data have been described elsewhere (see e.g. Fletcher and Nielsen Citation2017, Citation2018). Here we have decided to focus on four countries (UK, USA, Germany, and Spain) because we did not anticipate important country differences. However, we have included a representative of each of Hallin and Mancini’s (Citation2004) media system types in order to check this assumption.

Measures

Our primary independent variable is the use of search engines to search for news topics. The question used was: “Thinking about how you got news online (via computer, mobile or any device) in the last week, which were the ways in which you came across news stories?” Respondents were able to select from a list of eight different discovery methods, including “Used a search engine (e.g. Google, Bing) and typed in a keyword about a particular news story.” The option was worded to be distinct from another option, which read: “Used a search engine (e.g. Google, Bing) and typed in a keyword for the name of a particular website.” These were separated because many people have search engines as their homepage, and people sometimes use “smart” address bars to search for news sources they know instead of typing in the full URL.

We use three different dependent variables. The first is the “number of online news sources used in the last week.” This was collected by asking respondents to select which online news sources they had used in the previous week from a list of around 30 in each country. The other two dependent variables are called “diversity” and “balance” for shorthand. Though these terms can be understood in many different ways, we focus here on political diversity and balance. We use diversity to refer to having used at least one left-leaning and one right-leaning online news source in the last week. This is therefore a measure of “horizontal” diversity, as it refers to diversity of news sources, rather than the “vertical” diversity that may be found within content from the same source (Hellman Citation2001). Balance refers to the ratio of left-leaning to right-leaning online news sources used in the previous week (or the ratio of right-leaning to left-leaning sources, depending on which is higher). Operationalized in this way, we can capture diversity (use of news sources with different political leanings) separately from balance (equal use of news sources with different political leanings) as both empirically and normatively distinct.

Both measures require each news source in the survey to be coded as either left-leaning or right-leaning. To do this, we used an “audience-based” measure of outlet ideology (Gentzkow and Shapiro Citation2011; Bakshy, Messing, and Adamic Citation2015; Flaxman, Goel, and Rao Citation2016). Under this approach, the political preferences of the source’s audience are used to estimate its “ideology” or “slant.” This is not a “content-based” measure of ideology, but the two approaches have been shown to produce similar results (Flaxman, Goel, and Rao Citation2016).

To code each source, we first computed the average political leaning of the population of each country by asking all survey respondents to place themselves on a seven-point scale ranging from “very left-wing” to “very right-wing,” with “centre” as the mid-point. To make responses from different countries more comparable, we reduced this to a three-point scale, with left-leaning responses coded -.5, right-leaning responses .5, and centre as 0. Then, the same process was repeated to produce the average political leaning of the audience for each news source. Sources with a “lower” average political leaning than the mean of the population were coded as left-leaning, and those with a higher figure right-leaning.

Diversity is a binary variable, with respondents coded 1 if they used both a left-leaning and a right-leaning online news source in the same week, and all others coded 0. Balance is the decimal ratio of the number of left-leaning to right-leaning news sources used in the previous week. This variable therefore ranges from 0, which indicates that a respondent used either no left-leaning, or no right-leaning sources, through .5, which indicates that a respondent used twice as many sources of a particular leaning, to 1, which indicates that a respondent used the same number of right-leaning and left-leaning sources.

We also use a number of demographic, news use, and news attitude variables as controls. They are: age (measured in years), gender (male/female), education (six-point scale), political leaning (three-point scale), trust in news (five-point scale), interest in news (five-point scale), frequency of internet use (eight-point scale), the use of news aggregators (yes/no), and the use of social media for news (yes/no). Descriptive statistics can be found in . Respondents were able to answer “Don’t know” to the questions on political leaning, interest in news, and frequency of internet use. These respondents were removed from the analysis.

TABLE 1 Descriptive statistics for the independent and control variables

Results

Descriptive Statistics

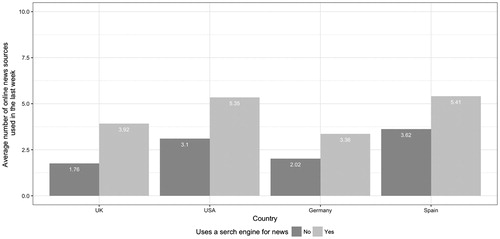

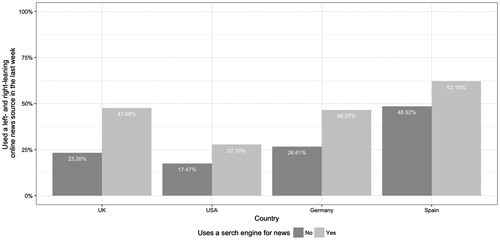

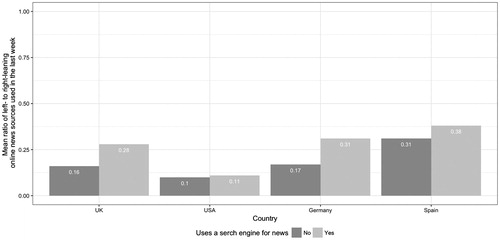

Before addressing our hypotheses, we offer some more descriptive statistics to help with the interpretation. The first of these is the average (mean) number of online news sources used in the previous week by people who use search engines for news, compared to those who do not. shows that in every country, those who use search engines to search for news topics use more online news sources than those who do not. Second, can we see that in every country the proportion of people who use a news source from both sides of the political spectrum is greater among those who use search engines to search for news topics (). In the UK and Germany, only 25% of people that do not use search engines for news consume news from both sides of the political spectrum, but that figure rises to just under half for those that do. Third, and contrary to expectations, we can see that in every country the ratio of left- to right-leaning sources is higher for users of search, meaning that those in this group have more balanced news repertoires on average (). In the UK and Germany, people that use search engines for news have news repertoires with a 3:1 ratio between sources from their preferred side of the spectrum and sources from the other side. For people that do not use search engines, the ratio is 6:1. However, in Spain and the US the difference between these two groups is much smaller.

Hypothesis Testing

We address our hypotheses using a series of regression models. To partially address the limitations of cross-sectional data, we performed propensity score matching using the MatchIt package for R. This process systematically removed respondents from the dataset so that the group that uses search engines for news was similar to the group that does not, in terms of the other variables used in the analysis. Doing so meant that the dataset contained fewer respondents, but any associations between search engine use and our dependent variables are less likely to be influenced by confounding factors.

H1 predicted that those who use search engines to search for news topics will use more sources of online news than those who do not. As the dependent variable for H1 is a count variable, we use a Poisson regression model. In every country, using search engines to search for news topics is significantly and positively associated with the number of online news sources used in the last week (see ). In other words, those who use search engines for news use more news sources than those that do not, even after controlling for a number of demographic, news consumption, and news attitude variables. H1 is therefore supported.

TABLE 2 Poisson regression models where the dependent variable is number of online news sources used in the last week

H2 predicted that those who use search engines to search for news topics will be more likely to use at least one left-leaning and one right-leaning online news source. As diversity is a binary variable, we use a series of binary logistic regression models. As we can see from , using a search engine to search for news is significantly and positively associated with using both a left-leaning and right-leaning news source in all four countries. H2 is therefore supported.

TABLE 3 Binary logistic regression models where the dependent variable is the proportion of people who used both a left-leaning and a right-leaning online news source in the last week

Last, we consider H3, which predicted that those who use search engines to search for news topics will be less likely to use a similar number of left-leaning and right-leaning online news sources than those who do not. Contrary to expectations, we see from that apart from in the US, using search engines to search for news topics is in fact positively associated with having a smaller gap between the number of left-leaning and right-leaning online news sources. H3 is therefore not supported. We therefore find little evidence to support the idea that those who use search engines for news will end up consuming disproportionally more online news sources with a particular political leaning.

TABLE 4 Poisson regression models where the dependent variable is the ratio of left-leaning and right-leaning online news sources used in the last week

Conclusion

Today, people increasingly come across news not only by going direct to preferred sources, but also through distributed discovery, where digital intermediaries including search engines, social media, messenger apps, and news aggregators help people find news, and as a consequence, reshape their news repertoires. This has led to concerns that the kinds of algorithmic filtering that enable companies like Facebook and Google to make billions of display decisions in real-time would lead users into echo chambers and filter bubbles.

In this article, we have shown that those who find news via search engines (i) on average use more sources of online news, (ii) are more likely to use both left-leaning and right-leaning online news sources, and (iii) have more balanced news repertoires in terms of using similar numbers of left-leaning and right-leaning sources. As anticipated, we did not find evidence of important country differences, with the key associations pointing in the same direction across the UK, the USA, Germany, and Spain.

The descriptive statistics show that most people—regardless of whether they use search engines or not—do not have particularly diverse news repertoires. This may partly explain why the filter bubble and echo chamber ideas often resonate with people’s personal experiences. Nonetheless, our analysis clearly shows that using search engines for news is associated with more diverse and more balanced news consumption because they are a source of what we have defined as “automated serendipity.” We use this term to refer to situations where automated news selection results in people being exposed to sources of news they would not normally use, and in such a way that this algorithmically driven boost has positive effects on their news repertoires. Despite fears of filter bubbles and echo chambers, we have found that search engines as they currently operate are drivers of automated serendipity.

Whether they will continue to be so as search results get increasingly personalized, results pages evolve, and search is increasingly based on voice-operated systems is an empirical question. It is clear that some forms of algorithmic ranking tend to offer items similar to those that a user has previously used, meaning that the risk of filter bubbles remains real. But it is also worth noting that those designing these systems are aware that users become bored with obvious recommendations, and that successful systems should offer “serendipitous suggestions” (Kotkov, Wang, and Veijalainen Citation2016) including items “significantly different” from those a user has already engaged with. “Diversity sensitive design” (Helberger, Karppinen, and D’Acunto Citation2018) is thus not only a normative ideal articulated by scholars, but also a practical goal sought by many engineers.

Perhaps the main limitation of this study is the reliance on a binary distinction between left- and right-leaning news sources. Though frequently used as a basis for measuring diversity, this distinction does not capture all the ways news can differ (Möller et al. Citation2018), and it may be that algorithmic selection by search engines homogenizes news repertoires in terms of topics, quality, target audience, and so on. Even if the focus is squarely on politics, some believe that the traditional left-right divide based on different economic views has become less important in recent years, accompanied now, for example, by cultural cleavages rooted in differences between the winners and losers of globalization (e.g. Kriesi et al. Citation2006). Future research could explore these factors, compare the performance of different search engines, or examine the issue at the level of news stories rather than news sources. As distributed discovery via digital intermediaries becomes more and more important, and the proceduralized choices that enable automated action at scale continue to evolve, it its critically important that independent researchers continually examine the implications for news use and civic engagement.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This work was conducted by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism with full independence. Data collection and research was supported by Google amongst 14 different funders. Funders have at no stage been involved in the analysis or writing and have not seen this work prior to publication. The article is entirely the responsibility of the authors. All underlying data is freely available for anyone interested in replicating or extending the analysis.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Richard Fletcher

Richard Fletcher (author to whom correspondence should be addressed), Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. E-mail: [email protected].

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. E-mail: [email protected].

REFERENCES

- Bakshy, Eytan , Solomon Messing , and Lada A. Adamic. 2015. “Exposure to Ideologically Diverse News and Opinion on Facebook.” Science 348: 1130–1132.

- Boczkowski, Pablo J. , Eugenia Mitchelstein , and Mora Matassi. 2018. “News Comes Across When I’m in a Moment of Leisure: Understanding the Practices of Incidental News Consumption on Social Media.” New Media & Society 1–17.

- Diakopoulos, Nicholas , Daniel Trielli , Jennifer Stark , and Sean Mussenden. 2018. “I Vote For—How Search Informs Our Choice of Candidate.” In Digital Dominance: The Power of Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple , edited by Martin Moore and Damian Tambini , 320–341. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dutton, William H. , Bianca Reisdorf , Elizabeth Dubois , and Grant Blank. 2017. “Social Shaping of the Politics of Internet Search and Networking: Moving Beyond Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Fake News.” Quello Centre Working Paper No. 2944191. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2944191.

- Flaxman, Seth , Sharad Goel , and Justin M. Rao. 2016. “Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Online News Consumption.” Public Opinion Quarterly 80: 298–320.

- Fletcher, Richard , and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2017. “Are News Audiences Increasingly Fragmented? A Cross‐National Comparative Analysis of Cross‐Platform News Audience Fragmentation and Duplication.” Journal of Communication 67 (4): 476–498.

- Fletcher, Richard , and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen . 2018. “Are People Incidentally Exposed to News on Social Media? A Comparative Analysis.” New Media & Society 20 (7): 2450–2468.

- Gentzkow, Matthew , and Jesse M. Shapiro. 2011. “Ideological Segregation Online and Offline.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126: 1799–1839.

- Gillespie, Tarleton . 2014. “The Relevance of Algorithms.” In Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society , edited by Tarleton Gillespie , Pablo J. Boczkowski , and Kirsten A. Foot , 167–194. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Google . 2005. “Personalized Search Graduates from Google Labs.” News from Google (blog). November 10, 2005. http://googlepress.blogspot.com/2005/11/personalized-search-graduates-from_10.html.

- Google . n.d. “How Google Search Works.” Accessed May 31, 2018. https://www.google.com/intl/en_uk/search/howsearchworks/.

- Haim, Mario , Andreas Graefe , and Hans-Bernd Brosius. 2018. “Burst of the Filter Bubble? Effects of Personalization on the Diversity of Google News.” Digital Journalism 6 (3): 330–343.

- Hallin, Daniel C. , and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hannák, Anikó , Piotr Sapieżyński , Arash Molavi Kakhki , Balachander Krishnamurthy , David Lazer , Alan Mislove , and Christo Wilson . 2013. “Measuring Personalization of Web Search.” In Procedings of the 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web, Rio de Janiero, May 13–17, 527–538.

- Helberger, Natali , Kari Karppinen , and Lucia D’Acunto. 2018. “Exposure Diversity as a Design Principle for Recommender Systems.” Information, Communication & Society 21 (2): 191–207.

- Hellman, Heikki . 2001. “Diversity – An End in Itself? Developing a Multi-Measure Methodology of Television Programme Variety Studies.” European Journal of Communication 16 (2): 181–208.

- Kotkov, Denis , Shuaiqiang Wang , and Jari Veijalainen. 2016. “A Survey of Serendipity in Recommender Systems.” Knowledge-Based Systems 111: 180–192.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter , Edgar Grande , Romain Lachat , Martin Dolezal , Simon Bornschier , and Timotheos Frey. 2006. “Globalization and the Transformation of the National Political Space: Six European Countries Compared.” European Journal of Political Research 45 (6): 921–956.

- Möller, Judith , Damian Trilling , Natali Helberger , and Bram van Es. 2018. “Do Not Blame It on the Algorithm: An Empirical Assessment of Multiple Recommender Systems and Their Impact on Content Diversity.” Information, Communication & Society 21 (7): 959–977.

- Nechushtai, Efrat , and Seth C. Lewis. Forthcoming. “What Kind of Gatekeepers Do We Want Mahcines to Be? Filter Bubbles, Fragmentation, and the Normative Dimensions of Algorithmic Recommendations.” Computers in Human Behavior .

- Newman, Nic , Richard Fletcher , Antonis Kalogeropoulos , David A. L. Levy , and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen . 2017. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017 . Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis , and Sarah Anne Ganter . 2018. “Dealing with Digital Intermediaries: A Case Study of the Relations between Publishers and Platforms.” New Media & Society 20 (4): 1600–1617.

- Nikolov, Dimitar , Diego F. M. Oliveira , Alessandro Flammini , and Filippo Menczer. 2015. “Measuring Online Social Bubbles.” PeerJ Computer Science 1 (e38): 1–14.

- Ørmen, Jacob . 2015. “Googling the News: Opportunities and Challenges in Studying News Events Through Google Search.” Digital Journalism 4 (1): 107–124.

- Pariser, Eli . 2011. Filter Bubbles: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. London: Penguin.

- Puschmann, Cornelius . 2017. “How Significant is Algorithmic Personalization in Searches for Political Parties and Candidates?” Algorithmed Public Spheres (blog). August 2, 2017. https://aps.hans-bredow-institut.de/personalization-google/.

- Sunstein, Cass R . 2017. Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Taneja, Harsh , James G. Webster , and Edward C. Malthouse. 2012. “Media Consumption Across Platforms: Identifying User-Defined Repertoires.” New Media & Society 14 (6): 951–968.

- Zuiderveen Borgesius , J. Frederick , Damian Trilling , Judith Möller , Balázs Bodó , Claes H. de Vreese , and Natali Helberger . 2016. “Should We Worry about Filter Bubbles?” Internet Policy Review 5 (1): 1–16.