Abstract

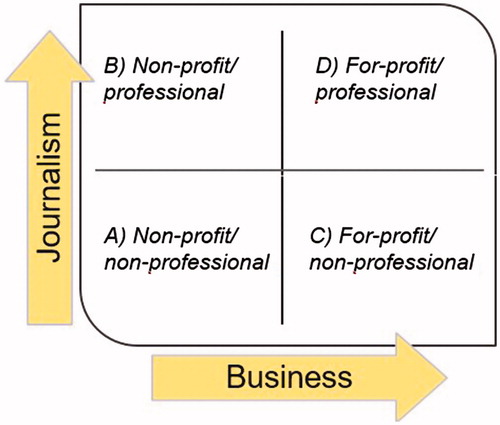

This study investigates how hyperlocal entrepreneurs interpret and undertake the role of accountable journalism, but it still acknowledges the many roles hyperlocal news may hold in a local community. The analysis is built on the approaches within this group toward (1) business and (2) journalism. The findings suggest that the focus of (A) nonprofit/nonprofessional could be to mirror community events, often as a “positive” counter-image. Within (B) nonprofit/professional, interrogative reporting could be viewed as a contribution to the common good. Niches of news alerts and partnership content are found within (C) for-profit/nonprofessional, while a full news standard is the (struggling) ambition within (D) for-profit/professional. The argument can be made that a deeper understanding of how media accountability can be addressed and/or promoted in this diverse sector of scarce resources is a vital question for policymakers, educational institutions and the public – as well as for the future of local journalism.

Introduction

Starting a news-based business has probably never been easier than in the digital age. Hyperlocal news is an emerging sector that offers both entrepreneurial possibilities such as interactivity, creativity and innovation as well as challenges such as funding, visibility and sustainability (Radcliffe Citation2012). Studies performed across countries show a diverse range of actors in terms of scale, location, driving forces, quality ambitions, funding and sustainability (e.g. van Kerkhoven and Bakker Citation2014; Williams et al. Citation2014). This diversity is also evident in Sweden (Leckner, Tenor, and Nygren Citation2017) and Finland (Lehtisaari et al. Citation2017). Categorization is difficult, and both the academic definitions and the sector itself are considered to be continuously evolving (Metzgar, Kurpius, and Rowley Citation2011). The plurality of professional backgrounds and orientation of the services hyperlocal news start-ups provide makes it difficult to assign them a single classification. As Cook, Geels, and Bakker (2016) summarizes “There is really no such thing as a typical hyperlocal media service” (7).

By tradition, media institutions hold a special position built on journalistic professionalism (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004), with the idea of public interest and social responsibility in the media leading to the concept of media accountability (McQuail Citation2010). The connection between strong local media, local identity, and local democratic participation has also been identified (e.g. Nygren Citation2005). Hyperlocal sites are often viewed as potential contributors to local democracy and media plurality (e.g. Barnett and Townend Citation2015; Harte, Turner, and Williams Citation2016; Nielsen Citation2015). It is still unclear, however, to what extent the small digital newcomers will be able to perform professional journalism (Sirkkunen and Cook Citation2012). Williams and Harte (Citation2016) point to the need to not only investigate the structural challenges of the sector but also the consequences of the on-going de-institutionalization and de-professionalization of local journalism. Increasing financial sustainability is regarded as a key aspect of independence, perseverance, and the possibility to serve the democracy as a fourth estate.

However, there are also social and cultural dimensions to local news, such as place making and community building (e.g. Harte, Williams, and Turner Citation2017; Hess Citation2014; Røe Mathisen Citation2015). Harte, Turner, and Williams (Citation2016) point to the risk of looking for an idealized “fictive” hyperlocal entrepreneur empowered by the digital age. If hyperlocals do not live up to expectations, both policymakers and scholars could lose interest. The sector is best considered on its own diverse terms, avoiding standardized solutions, states Radcliffe (Citation2012).

The 13 participants of this interview study represent a variety of business models and forms of professional knowledge. This article aims to recognize the diversity among hyperlocal news start-ups and many roles they may serve in a local community while still offering a normative vantage point to their journalism and thereby contribute to the research on the sustainability of hyperlocal news. If hyperlocal news is to be part of the future of local journalism, then an understanding of the professional norms and media accountability in this sector is vital for policymakers, educational institutions, and the local public. The purpose of this study is therefore:

to investigate how hyperlocal entrepreneurs interpret media accountability and undertake the role of professional journalism (autonomy, norms and ethics, fulfilment of a public interest) in relation to (a) journalistic skill set and (b) business orientation.

to investigate factors leading to changes and trajectories hyperlocals aim for.

Professional Journalism, Media Accountability, and the Hyperlocal Sector

Adopting certain standards of media ethics can be viewed as a prerequisite for the performance of professional journalism. Hallin and Mancini (Citation2004, 35) suggest the following three dimensions of journalistic professionalization: autonomy, distinct professional norms, and public service orientation. Autonomy means the ability to stand up to pressure from both internal and external stakeholders. Distinct professional norms are related to autonomy and exemplified by boundaries between advertising, editorial content, and ethical principles. Public service orientation is linked to the traditional role of journalism in society, which separates media institutions from other institutions and lends the authority of public trust. Barnett and Townend (Citation2015, 335) suggest the following four areas of democratic functions for the local media: informing, representing, campaigning, and interrogating (see also Sweden Citation1975).

The concept of media accountability develops the idea that media serve a public interest and carry a certain social responsibility; “that media can and should be held to account for the quality, means and consequences of their publishing activities to society in general and/or other interests that may be affected” (McQuail Citation2010, 562). This means that the media can be held to account directly and indirectly by both individuals and society for the quality of its performance.

Typically, in a democracy, news operations face few legal constraints on their published content. The Swedish media system is defined as democratic corporatist (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004). Sweden’s constitutional laws, the Freedom of the Press Act, and the Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression date back to 1766. National organizations for newspaper publishers and journalists founded the Swedish Press Council (Pressens Opinionsnämnd, PON), already in 1916, and there is a self-disciplinary Ethical Press System for complaints regarding breaches of “good journalistic practice” (Pressombudsmannen Citation2018).

However, the notion of media ethics is also affected by the digital revolution. Ward (Citation2014) raises questions about who is considered a journalist when citizens and nonprofessionals are reporting and analyzing events and if the same ideals of objectivity and editorial independence are applicable to them: “We witness the end of a tidy, pre-digital journalism ethics for professionals and the birth of an untidy digital journalism ethics for everyone” (456).

This challenge is also relevant in the hyperlocal news sector, where publishers come from different backgrounds. Hyperlocal news is also formulated as an “in-between sector” by Friedland (Citation2001), referring to a layer between legacy media and personal blogging. The sector is described as “messy” in a European study (Cook, Geels, and Bakker Citation2016, 9), with roots that are sometimes entrepreneurial, sometimes editorial (ibid., 23). Empirical studies include both for-profit and nonprofit initiatives with content produced by amateurs, citizen journalists, as well as professional journalists. In an interview study with 35 UK hyperlocal practitioners, initial motivations are described as civic, hobbyist, or commercial (Harte, Turner, and Williams Citation2016, 241). Even though there sometimes seems to be a certain “clash of discourses” in the attitudes to the economics, the findings suggest a dominant civic discourse for both voluntary and income-generating hyperlocals, with motivations such as participating in the community and filling the news gap. In contrast, one interviewee also views the “democratic deficit” as a commercial opportunity for local journalism (241). In a case study, Naldi and Picard (Citation2012) range three independent hyperlocal online news startups in the USA as more or less commercially oriented, as well as more or less civic activist oriented.

Method and Material

In 2015/2016, 89 independently owned and managed online news sites, with approximately 75 owners, were mapped in Sweden (Nygren, Leckner, and Tenor Citation2018; Tenor Citation2017a, Citation2017b). The results of a follow-up survey identified local identity and community building as the most common aims and reasons for starting a hyperlocal outlet but indicated different commercial and journalistic approaches (Leckner, Tenor, and Nygren Citation2017). Therefore, not viewing financial and civic motives as opposing forces, this model presupposes the hyperlocals’ engagement in (or benefits to) the local community but distinguishes between business models and professional journalistic skill sets. These two factors, which are keys for performing accountable journalism, were placed in a two-way matrix, thus creating the following four categories of hyperlocal entrepreneurs: (A) nonprofit/nonprofessional, (B) nonprofit/professional, (C) for-profit/professional, and (D) for-profit/nonprofessional (). These are regarded as four “ideal types”, drawing on Max Weber, as proposed by Esaiasson et al. (Citation2012, 139). Ideal types are not to be understood as representing an average but as hypothetical categories refined from typical factors, to be used as theoretical tools. Breaking down the participants into the category they most resemble, however roughly, provides a much-needed and useful analytic tool for investigating this heterogeneous field, as well as a structure when presenting the findings.

Using the results of the mapping and the follow-up survey, a sample (Larsson Citation2013, 61) of hyperlocal online news was selected by applying empirical methods to find as diverse operations as possible. The material consists of 13 semistructured interviews broken down into four categories (). This categorization should not be interpreted as definitive; the participants represent a variety of business models and professional backgrounds, from trained and/or experienced journalists to amateurs and semiprofessionals. Their operations also vary in scale and are spread throughout Sweden, including in both sparsely populated and urban areas.

Table 1 Participants of the study

Even though this sample represents approximately one-sixth of the independent hyperlocal online news operations in Sweden, the study cannot claim theoretical saturation given the unique character of many of these operations.

The design of the interview guide is similar to the European study of hyperlocal revenues (Cook, Geels, and Bakker Citation2016) with additional and more in-depth questions about the operations, self-definitions and experiences. These questions were divided into the following five sections: (1) background, (2) journalism, (3) organization, (4) finances, and (5) entrepreneurial skill set. All interviews were conducted over the telephone, taking approximately 2 hours each. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and later thematized under different headings.

Findings

Before presenting the experiences and interpretations of media ethics and accountability found in this study, let us look at some of the categories’ common features. Both the volunteer and the self-employed hyperlocal entrepreneurs often described their work as a lifestyle, firmly rooted in the local neighborhood and allowing the freedom to manage their own time, be creative, learn and build relationships. However, close relationships with people who are directly or indirectly affected by the news can be a double-edged sword: “When something bad happens and you have to write about it, you are likely to know the person. In everything you do, you are really close” (HL12). Regardless of where they fell in the matrix, the participants commented that it did not take long before their operations were receiving tips on both local events and possible improprieties. The interviews reveal skills and self-definitions from amateurs, semi-professionals and trained and experienced journalists. There is naturally a big difference in terms of business skills between the journalist-turned entrepreneur and the local entrepreneurs in PR or digital marketing testing a new business idea, perhaps only as a complement to an existing venture. Nonpaid work, even among nonprofit entrepreneurs, is often viewed as a temporary solution; by more commercially orientated business entrepreneurs as an investment for the future. While one hyperlocal entrepreneur is content with a modest, crowdfunded income, others are taking steps toward expansion. Some of the hyperlocals are run as sole proprietorships; others are teaming up with specialized partners in advertisement or journalism.

Even though the following material is broken down into four types, this should not be interpreted to be definitive labels or boxes but rather an analytic tool.

Nonprofit/Nonprofessional (A)

The nonprofit/nonprofessionals in this study view it to be a social responsibility to mirror local life, which is often contrasted by the absence of such reporting from traditional media (i.e. the local newspaper). Examples are found in both rural and metropolitan areas: “The people from the newspaper do not work weekends or evenings/…/. So, I am the only one showcasing events taking place” (HL11).

This self-defined social responsibility also provides a positive counter-image in areas where the regional newspaper is considered too negative: “In fact, when something is on the verge of being negative, we actually expend energy to find the positive aspects” (HL1).

For this group, objectivity is not always a goal; being part of the community and collaborating with stakeholders sometimes takes precedence. However, this lack of autonomy does not exclude the desire to achieve other traditional journalistic ambitions, such as rapid and accurate reporting on news events. Another participant calls his own reporting “too positive” and is aware he deviates from the professional norm: “I do not write about negative things; I disregard them. But, yes, this is clearly a problem if you are going to be a proper newspaper” (HL4).

Some would like to monetize their operations but continue to provide positive, patriotic news. Others express a wish to fulfill more of a professional journalistic role, such as explaining and investigating. Due to a lack of time and knowledge, the only sustainable way to move in this direction is through partnership. A compromise is to provide as a minimum an area for local debate. However, when one of the participants published a provocative debate article, he received reactions from the readership demanding media accountability: “I had to explain, that if we do not allow this [to be published], what will remain?/…/I had to defend myself very carefully on Facebook” (HL11).

Nonprofit/Professional (B)

The nonprofit/professionals in this study are grounded in community activism, one example being an association to save the local harbor. They focus on holding local power to account, thus using journalistic skills as their contribution to the common good. This is also motivated by how they perceive their local political culture, addressing corruption and power abuse, a lack of interrogative reporting, and the increasing PR resources at the municipality’s public communications department. A lack of resources, however, limits the ability to publish frequent updates, provide a debate forum and also maintain strict professional boundaries. The same journalist might both report (news) and write opinions (editorials) on public affairs.

The participants in this group rely on income from pensions or part-time jobs in other industries. Volunteer work is common: “It's a commitment, I'm also active in Amnesty, and I don’t charge them, either.” (HL8). Another participant hopes to increase sales to earn a living wage, for example through partnership with someone specialized in business. However, not making money is not always attributed to a lack of business skills, but rather to a deliberate disregard for market demands. This same participant was previously involved in a start-up of a local print product but soon discovered that the glossy magazine did not interest her.

For-Profit/Nonprofessional (C)

The for-profit/nonprofessionals in this study have focused on local news for two reasons: a perceived demand for journalism and a personal interest. They seem to be at an advantage in that they are generating revenue, and some pay journalists to do the professional reporting. However, they also evaluate the financial results and are prepared to lower their journalistic ambitions if necessary.

Even if this group is not knowledgeable about professional norms, being held accountable by partners can force them to take such a stance. One example can be found in the hyperlocal smartphone application created by two local entrepreneurs who worked in sales and IT. They had an idea to serve local advertisers and the local council, but they employed a local journalist after discovering a demand for local news in their product. When the journalist reported critically on local affairs, the municipality reacted, leading the owners to reflect on the autonomy and boundaries between sales and editorial content.

Learning by doing is another common approach. A sole proprietor got a call from a press officer at a big company asking for the responsible editor. He realized that this was expected from a professional publisher: “And then you simply register one [responsible editor]” (HL2). When individuals who felt that they had been targeted by news reporting demanded accountability, the participant changed his work routines and began to include fewer details in his reporting. Another strategy to avoid publicity damage is to consistently avoid establishing the causes of an accident, a fire or a crime. “I have drawn the limit there, we do not interrogate; we tell you what happened” (HL2). This means also underlining that the hyperlocal site only provides information on what is happening in this instant, but not “in the municipality building” (HL2).

For-Profit/Professional (D)

The last category is referred to as for-profit/professionals, but the participants still see a strong need to develop both business models and journalism skills, especially in terms of ethics and publishing. There is also a large income span; some are happy to earn a modest wage, while others feel that they probably should be making more money considering their digital reach.

Even though the readership might be happy with news alerts, it seems to be an important part of this group’s self-definition to provide some critical or interrogative reporting and also vital in the long run to gain public trust. There are several examples where negative reactions from local positions of power are mentioned with pride as a mark of autonomy. Familiarity with professional norms seems to make it easier to formulate autonomy toward stakeholders despite the changing role for a local journalist-turned entrepreneur. This familiarity also serves as a guideline when people demand accountability for an overly negative portrayal of the local community.

But we cannot ignore a smash and grab the other day, a shooting a few days earlier and a murder two weeks ago./…/Nine out of ten articles are probably positive news about local entrepreneurship, the municipality doing a good thing, about school, sports teams and so on – but the reality and the investigations must also be a part of the content. (HL6)

Hyperlocal News and the Ethical System

Even though the concept of responsibility is acknowledged in different ways, the possibilities to hold these digital operations to account can seem limited. Only a few have joined the Ethical Press System, which is managed by the Swedish Press Ombudsman, PO. In August 2017, PO had registered 26 hyperlocal online-only publications as members and 10 of them were titles from the same parent company, 24 Journalistik (Pressombudsmannen Citation2017). This means that many small, independent hyperlocal news sites are operating outside the democratic corporatist system for media accountability in Sweden.

At the time of the research interviews, four of the 13 participants of this study were members of the Ethical Press System and of these four all of them had previous work experience in legacy media journalism. However, only days after the research interview, we discovered that another participant joined the system, and later, in the spring 2017, another two. This suggests that being asked about membership may have prompted participants to join.

Some participants did not join the Ethical Press System because they considered it to be too expensive or unnecessary: “We follow the rules anyway” (HL 7). The more innovative online news services, though, were facing concrete obstacles: when content is also provided by partners, it is difficult to appoint a responsible editor who is expected to do the required preview of all content.

Discussion

Professional Journalism

The findings of this study support the hypothesis that serving the public interest is an ambition found among hyperlocals regardless of their approach to the professional norms of journalism and their business model. Previous research has also highlighted that the public expects local media to be a “good neighbor”, meaning it should care about and appreciate the community and focus on both solutions and problems (Heider, McCombs, and Poindexter Citation2005). The participants in this study consider themselves residents and members of the local community as well as publishers. They often define their site as a complement to other media, with the aim, of course, to be more local. This position often counterbalances perceived negative or submissive reporting, and they often feel a subsequent social responsibility to provide this counterbalance. They view their actions as a commitment to the local community: focusing on the positives to strengthen local confidence or scrutinizing maladministration to promote real changes.

Even when a hyperlocal is self-described as “too positive” compared to professional journalistic standards, the participant also thinks that the audience accepts the orientation and does not consider it to be a conflict of interest. Ward (Citation2014) also raises the question of whether objectivity ideals are even applicable to citizen and non-professional reporters.

The sites dedicated to investigative journalism are updated less frequently and can be contrasted with news alerts sites, which are sometimes combined with a side business of freelance photography for emergencies. There are also a few operations, however small, that aim for a full news standard, sometimes challenging established media and forcing them to enhance their digital reporting.

Altering the purpose of the website, for example from mainly providing a channel for local advertisements to providing original reporting, changes the self-definition and requires more knowledge about professional journalism practices. It also seems that participants with established skills and experience in journalism can be more confident when defending autonomy, for example the boundaries between editorial and advertised content. This possible re-negotiation of journalistic principles is addressed by Chadha (Citation2015). However, the findings of this study suggest that experienced journalist-turned entrepreneurs take pride in their autonomy from advertisers. Still, the need for resources limits how autonomous they can be, and highly skilled journalists can also depart from traditional notions of objectivity, motivated by the pursuit of causes they perceive as important.

The strategy to add competence by recruiting staff seems, not surprisingly, to be a more common approach for entrepreneurs with a developed business model. This differentiation of occupations has been seen as the very beginning of professional journalism (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004, 35). However, there are also examples of hiring and co-working with highly skilled journalists as a learning process, for example in methods of investigative journalism, but hyperlocal entrepreneurs can also share their knowledge, for example with volunteers, community journalists, trainees, and students – or in networks with other hyperlocals.

Media Accountability and the Hyperlocals

Working as a local publisher in the local neighbourhood gives a specific angle to media accountability. This can be explored with reference to the proximity dilemma, where journalists walk a fine line between patriotism and critical corrective (Røe Mathisen Citation2015). The dependency on local news sources is not new (Nielsen 2015), but running small businesses, even sole proprietorships, can put the hyperlocal entrepreneur in a vulnerable position. Reactions from partners or advertisers who feel unfairly represented in the reporting are common. External demands for accountability, both by individuals and society, force hyperlocals to articulate a stance and/or realise a lack of ethical considerations.

However, entrepreneurs who lack both prior journalism experience and tie to professional reporters are also demonstrating self-censorship and self-limitations. One example is the strategy to always refrain from explaining why something happened. By only describing what has occurred, and not trying to establish the causes leading up to this event, the risk for being held accountable by readers is minimized.

Promoting the Hyperlocal

From a normative point of view, hyperlocal operations that meet the traditional standards of journalism could be considered the most valuable for society. However, this would not only risk the omission of the value of everyday issues and collaboration in the community (Postill Citation2008), or cultural and social dimensions of place-making and community roles (Harte, Williams, and Turner Citation2017) but also the failure to recognize the possible trajectories within the individual operations, depending on both internal and external factors, as shown in this study. This tendency of hyperlocals to change is similar to former journalists facing new work roles (Chadha Citation2015) and hobbyists trying to turn their operations into business (Williams et al. Citation2014).

Hyperlocals are small enterprises with limited resources, which make them vulnerable in a swiftly changing media landscape. External demands on accountability sometimes lead to changed routines. Familiarity with professional norms can strengthen the ability to sustain autonomy and to take responsibility. Even when the operations have limited resources, online or offline networks could function as internal chains of control or back-up.

Conclusion

The conclusion of this study is that small hyperlocal entrepreneurs often limit their public service orientation in a way that is related to their skill set. In this study, the hyperlocals are broken down into four categories in order to deepen the understanding of challenges common to the entire group of hyperlocals as well as more specific challenges. This study shows that media ethics and accountability are recognized as important challenges facing hyperlocal entrepreneurs and that there is a broad recognition of traditional dimensions of professional journalism. Even though hyperlocal practitioners sometimes lack both time and knowledge or have to accept standards that are lower than they consider desirable, external demands on accountability, learning-by-doing, adding new team members, and/or recruiting staff are potential drivers of change.

Hyperlocals have the potential to hold significant roles in a local community and are characterized by a strong development potential. This implies the importance to continue investigating their journalistic performance, as well as the value of including all types of hyperlocal practitioners in research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to thank Gunnar Nygren, Södertörn University, and Sara Leckner, Malmö University, for their essential input into the organization of this article and the development of the ideas presented here.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

FUNDING

This work was supported by Jenz and Olof Hamrin's Foundation, Sweden.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carina Tenor

Carina Tenor, Department of Social Sciences, Södertörn University, Stockholm, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected].

REFERENCES

- Barnett, Steven , and Judith Townend. 2015. “Plurality, Policy and the Local.” Journalism Practise 9 (3): 332–349. doi:10.1080/17512786.2014.943930.

- Chadha, Monica . 2015. “What I AM VERSUS WHAT I do: Work and Identity Negotiation in Hyperlocal News Startups.” Journalism Practice, 10 (6): 697–714. doi:10.1080/17512786.2015.1046994.

- Cook, Clare , Kathryn Geels , and Piet Bakker. 2016. Hyperlocal Revenues in the UK and Europe – Mapping the Road to Sustainability and Resilience. London: Nesta. https://www.nesta.org.uk/sites/default/files/hyperlocal-revenues-in-the-uk-and-europe-report.pdf.

- Esaiasson, Peter , Mikael Gilljam , Henrik Oscarsson , and Lena Wängnerud. 2012. Metodpraktikan: konsten att studera samhälle, individ och marknad. 4. [Methods: the Art of Studying Society, Individuals and Market]. Stockholm: Norstedts juridik.

- Friedland, Lewis A . 2001. “Communication, Community, and Democracy: Towards a Theory of the Communicatively Integrated Community.” Communication Research 28 (4): 358–391.

- Hallin, Daniel C , and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three models of Media and Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Harte, Dave , Jerome Turner , and Andy Williams. 2016. “Discourses of Enterprise in Hyperlocal Community News in the UK.” Journalism Practice 10 (2): 233–250. doi:10.1080/17512786.2015.1123109.

- Harte, Dave , Andy Williams , and Jerome Turner. 2017. “Reciprocity and the Hyperlocal Journalist.” Journalism Practice 11 (2–3): 160–176. doi:10.1080/17512786.2016.1219963.

- Hess, Kristy . 2014. “Making Connections: ‘Mediated’ Social Capital and the Small-Town Press.” Journalism Studies 16 (4): 482–496. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2014.922293.

- Heider, Don , Maxwell McCombs , and Paula M. Pointdexter. 2005. “What the Public Expects of Local News: Views on Public and Traditional Journalism.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 82 (4): 952–967. doi:10.1177/107769900508200412.

- Larsson, Larsåke . 2013. “Intervjuer.” In Metoder i kommunikationsvetenskap [Methods in Communication Studies], edited by Mats Ekström and Larsåke Larsson, 53–86. Lund: Studentlitteratur [Interviews].

- Leckner, Sara , Carina Tenor , and Gunnar Nygren. 2017. “What About the Hyperlocals?” Journalism Practice, 1–22. Published online 07 November. doi:10.1080/17512786.2017.1392254.

- Lehtisaari, Katja , Jaana Hujanen , Mikko Grönlund , and Carl-Gustav Lindén. 2017. “New Forms of Hyperlocal Media in Finland: The Fifth Expansion Period.” Paper presented at Nordmedia, Tammerfors, August.

- McQuail, Denis . 2010. McQuail's Mass Communication Theory. 6th ed. London: SAGE.

- Metzgar, Emily T. , David D. Kurpius , and Karen M. Rowley. 2011. “Defining Hyperlocal Media: Proposing a Framework for Discussion.” New Media & Society 13 (5): 772–787. doi:10.1177/1461444810385095.

- Naldi, Lucia , and Robert G. Picard (2012). “‘Let’s Start an Online News Site’: Opportunities, Resources, Strategy, and Formational Myopia in Startups.” Journal of Media Business Studies 9 (4): 69–97.

- Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis . 2015. Local Journalism: The Decline of Newspapers and the Rise of Digital Media. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Nygren, Gunnar . 2005. Skilda medievärldar [Separate Media Worlds]. Stockholm: Symposion.

- Nygren, Gunnar , Sara Leckner , and Carina Tenor. 2018. "Hyperlocals and Legacy Media: Media Ecologies in Transition”. Nordicom Review 39 (1): 33–49. doi:10.1515/nor-2017-0419

- Postill, John . 2008. “Localizing the Internet Beyond Communities and Networks.” New Media & Society 10 (3): 413–431.

- Pressombudsmannen . 2017. “Anslutna nättidningar” [Associated online news outlets] (list). Accessed August 25 . http://www.po.se/kontakt/anslutna-nattidningar.

- Pressombudsmannen . 2018. “How Self-Regulation Works” Accessed September 13. https://po.se/about-the-press-ombudsman-and-press-council/how-self-regulation-works/

- Radcliffe, Damian . 2012. Here and Now: UK Hyperlocal Media Today. London: Nesta.

- Røe Mathisen, Birgit . 2015. Lokaljournalistikk [Local Journalism]. Oslo: IJ-forlaget.

- Sirkkunen, Esa , and Clare Cook. 2012. Chasing Sustainability on the Net. Tampere: Comet.

- SKL ( Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions ) . 2017 . “Classification of Swedish Municipalities 2017.” Accessed September 5, 2018. https://skl.se/download/18.6b78741215a632d39cbcc85/.

- Sweden. 1975. “SOU 1975:79. Svensk press – statlig presspolitik. Betänkande av 1972 års pressutredning [ Swedish Press , State Press Policies].” Report on the Public Inquiry of the Press from 1972].

- Tenor, Carina (2017a). “Analys: Här finns de hyperlokala sajterna [Analysis: Here Are the Hyperlocal Sites].” Medievärlden Premium , March 28. Accessed September 13, 2018. https://premium.medievarlden.se/analyser/motiven-bakom-de-hyperlokala-sajterna

- Tenor, Carina (2017b). “Analys: Hyperlokala sajter – fem typer att hålla koll på [Analysis: Hyperlocal Sites – Five Types You Need to Know About].” Medievärlden Premium , June 8. Accessed September 13 2018. https://premium.medievarlden.se/analyser/hyperlokala-sajter-fem-typer-att-halla-koll-pa

- van Kerkhoven, Marco , and Piet Bakker. 2014. “The Hyperlocal in Practice: Innovation, Creativity and Diversity.” Digital Journalism 2 (3): 296–309. doi:10.1080/21670811.2014.900236.

- Ward, Stephen J. A . 2014. “Radical Media Ethics.” Digital Journalism 2 (4): 455–471. doi:10.1080/21670811.2014.952985.

- Williams, Andy , Steven Barnett , Dave Harte , and Judith Townend . 2014. “The State of Hyperlocal Community News in the UK: Findings from a Survey of Practitioners.” Accessed September 5, 2018. http://www.communityjournalism.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Hyperlocal-Community-News-in-the-UK-Final-Final.pdf.

- Williams, Andy , and Dave Harte . 2016. “Hyperlocal News.” In SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by Tamara Witschge, Chris W. Anderson, David Domingo, and Alfred Hermida, 280–293. London: SAGE.