Abstract

With print circulations in decline and the print advertising market shrinking, newspapers in many countries are under pressure. Some—like Finland’s Taloussanomat and Canada’s La Presse—have decided to stop printing and go online-only. Others, like the Sydney Morning Herald, are debating whether to follow. Those newspapers that have made the switch often paint a rosy picture of a sustainable and profitable digital future. This study examines the reality behind the spin via a case study of The Independent, a general-interest UK national newspaper that went digital-only in March 2016. We estimate that, although its net British readership did not decline in the year after it stopped printing, the total time spent with The Independent by its British audiences fell 81%, a disparity caused by huge differences in the habits of online and print readers. This suggests that when newspapers go online-only they may move back into the black, but they also forfeit much of the attention they formerly enjoyed. Furthermore, although The Independent is serving at least 50% more overseas browsers since going online-only, the relative influence on that growth of internal organizational change and external factors—such as the “Trump Bump” in news consumption—is difficult to determine.

Introduction

Founded in 2007, Paul Gillin’s Newspaper Death Watch website 1 chronicles the decline of newspapers in the United States. Alongside a RIP memorial to newspapers that no longer exist in any form, Gillin has a WIP—Works in Progress—list of a dozen newspapers that have cut print editions and are hoping to survive as digital brands. Many commentators believe that if print circulations and advertising revenues continue to fall, more newspaper brands will join Gillin’s list (see, e.g., Cathcart Citation2016). There is, therefore, a need to build upon the small number of case studies of newspapers that have moved online-only.

In this article, we present a case study of The Independent, the first UK national newspaper brand to go online-only. In contrast to most previous studies, the impact of the transition on the brand’s audience is examined. Specifically, we use data from comScore, and from the UK’s National Readership Survey (NRS) and Audit Bureau of Circulations (ABC), to investigate changes in the title’s readership and in the attention it receives. Our primary focus is on The Independent’s British audience, but we also consider its overseas visitors.

The Independent

The Independent was a relatively late entrant into the British newspaper market, established in 1986 as a national daily broadsheet newspaper. A Sunday edition was launched 4 years later and a website in 1996. The brand was able to carve out a niche through a provocative editorial approach that involved the trumpeting of its political independence, and a focus on the arts, which proved particularly appealing to much-sought-after younger readers. In the early 1990s The Independent briefly surpassed The Times in weekday print distribution, with a circulation of close to 390,000 (Crewe and Gosschalk Citation1995, 135).

Despite a strong start, the fortunes of The Independent began to change following an economic downturn and a broadsheet newspaper price war, leading to a takeover from an Irish media group in the late 1990s. A succession of new editors and relaunches followed. In 2004 The Independent became the first British broadsheet to switch to a tabloid print format. Despite initial gains, print readership continued to decline, exacerbated by the wider newspaper crisis, and, in 2010, The Independent was purchased by Russian businessmen Alexander and Evgeny Lebedev for £1.

In the same year, a sister paper, the i, was launched. The i, with its significantly lower price, soon established a much higher print circulation than The Independent. There was some overlap in the content of the two titles’ daily print editions, and they operated a single website (www.independent.co.uk). Despite the success of the i, Independent Print Limited, the company behind the newspapers, lost an average of over £13 million a year between 2011 and 2015 (Companies House, n.d.-a) and was able to continue trading only due to the financial support of the Lebedevs.

In 2014 The Independent and the i launched an additional spin-off website, i100, devoted to digital-friendly, sharable content, and, although reliant on resources from the loss-making print titles, the online editions, which had become profitable in 2012/13, turned a profit of £1,272,556 in 2014/15 (Companies House, n.d.-b). By this time losses across the whole print/digital operation had been reduced but were still considerable, at close to £6 million annually. Facing another year of losses and with The Independent’s weekday print circulation down to under 60,000, the company decided in 2016 to stop printing both The Independent and the Independent on Sunday and move the titles online-only.

The last print edition of The Independent was published on 26 March 2016. The i, with its relatively successful print product, was sold off to regional publisher Johnston Press and remains in print as of April 2018. After the sale, the i100 website was retained by The Independent and rebranded as indy100. The i launched its own separate dedicated website—inews.co.uk—in April 2016.

A Note on Terminology

For the sake of brevity, the single term “The Independent” is used frequently in this article to refer to the multiplatform newspaper brand consisting of:

up to 26 March 2016, a Monday to Saturday print edition, The Independent;

up to 20 March 2016, a Sunday print edition, the Independent on Sunday; and

websites and apps, including www.independent.co.uk and i100/indy100.

Going Online-Only

Only a handful of studies have investigated what happens when newspapers cut their print editions (Thurman and Myllylahti Citation2009; Groves and Brown-Smith Citation2011; Usher Citation2012). Most are detailed ethnographies and contribute to the stream of journalism studies literature interested in institutional and professional transformations brought about by technological change. In her longitudinal study of the Christian Science Monitor, Nikki Usher (Citation2012) analyzed journalists’ opinions and behavior during the period the American title cut print editions. Among other changes, Usher observed that “what had been a peripheral awareness of [audience metrics] had transformed into an obsession” (1909), with journalists increasingly concerned that the focus on analytics was antithetical to both good journalism and to the specific mission of the newspaper.

In an earlier case study, Thurman and Myllylahti (Citation2009) described how Taloussanomat—a Finnish financial daily—fared following its transition to online-only in 2007. The authors described how cost savings associated with dropping the print edition improved the brand’s financial position. They too found an increased focus on audience metrics, with pressure to produce more populist, web-friendly articles that pulled in traffic. Unlike the other case studies, Thurman and Myllylahti’s also provided a brief analysis of audience change at Taloussanomat, showing that, although online audiences increased slightly post-print, the growth was smaller than at Taloussanomat’s direct competitor, which had retained a print edition. However, the study did not look at net (deduplicated) print and online readership before and after the move to online-only. Thurman and Myllylahti also produced a rough estimate of the change in attention received by Taloussanomat after it stopped printing (reporting a 75–80% reduction in time spent reading [704]).

For the attention given to newspaper brands in print not to transfer online might be said to go against displacement theories that have shown that online news consumption has displaced newspaper consumption, as audiences switch from one medium to the other (see, e.g., De Waal and Schoenbach Citation2010). However, these theories have mostly been based on analyses of periods during which two or more competing media co-existed rather than on the periods before and after the sudden disappearance of a medium.

On the other hand, some ‘uses and gratifications’ research suggests people might indeed abandon news brands that are no longer available in print. In the 1940s Bernard Berelson (Citation1949) observed that few people read newspapers solely to be informed about current events. Newspaper use was described as a deeply engrained habit, a social experience to be shared with others, and an enjoyable physical act—all aspects that people still valued at the turn of the millennium (Bentley Citation2001). Printed newspapers as objects can also form part of rituals, have symbolic value, and be used as tools (Barnhurst and Wartella Citation1991).

More recently, studies have found that some people are reluctant to move online when newspapers stop printing. When The Atlanta Journal-Constitution pulled its print edition from certain neighborhoods, researchers found that, although most people said they missed the newspaper, few turned to the web version as a substitute (Hollander et al. Citation2011).

Research Questions

This article extends, for the first time, the academic study of post-print newspapers to a national, generalist title. It develops Thurman and Myllylahti’s (2009) analysis by examining changes in The Independent’s readership, using a measure that accounts for the loss of print readers, avoids double-counting multiplatform consumers, and allows comparisons to be made with multiple other newspapers in the same market that have retained a print edition. Specifically, we ask:

RQ1: How did the net monthly British readership of The Independent change when it stopped printing and went online-only?

By answering RQ1 we will be able to interrogate The Independent’s claim of “significant digital audience growth” post-print (Independent Digital News and Media Citation2016, p 2).

Previous research (Thurman Citation2017) has shown fundamental differences in the way print and online editions are consumed, with the time spent reading a newspaper’s online editions being a fraction of that spent with its print products. To assess the effect of The Independent’s now total reliance on digital distribution we ask:

RQ2: How did the attention (expressed in time spent reading) received by The Independent from its British audience change after it stopped printing and went online-only?

Finally, we consider the impact of the transition on The Independent’s international audience through this research question:

RQ3: How has the international traffic (expressed in unique browsers and page impressions) attracted to The Independent’s online editions changed since the title went online-only?

By answering RQ3 we will be able to assess the extent to which the title has managed, as its management hoped, to “take advantage” of its online-only status to achieve its “global ambitions” (Sweney and Johnston Citation2016). Around the time of the switch, The Independent’s CEO said that he thought the brand’s editorial proposition was “perfectly suited to the global digital landscape” (Independent Citation2016a), and the company promised to invest in editorial bureaux in Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and the US (Sweney and Johnston Citation2016).

Data Sources and Methods

Readership

To answer RQ1, data was acquired from the UK’s National Readership Survey (NRS). Since 2012 the NRS has provided readership figures that reflect newspapers’ net (deduplicated) print and online audiences. Going under the name PADD (Print and Digital Data), the figures are produced by “fusing” data from the NRS’s representative survey (N = 33,225) of British print readers with data from comScore about online consumption.

Before the introduction of PADD, the NRS only produced readership data for newspapers’ print editions, and, although data on the number of visitors to those newspapers’ online editions was available from other sources, there was no way of knowing the degree of duplication across the data sets, that is, whether readers of newspapers’ print editions also read their online editions and vice versa. Although PADD reports net readership on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis, it is only the monthly data that includes mobile-only readers. We have chosen to focus on monthly readership because of the high proportion of readers who access newspapers via mobile devices.

Although top-level PADD data is available on the NRS website, these public reports have not always separated out The Independent from its one-time sister newspaper brand, the i—which continues in print—and do not properly account for readers of the Independent on Sunday. Therefore, the PADD data used in this study was the result of custom queries made to the underlying database by a specialist data bureau at our request.

Time Spent

The data sources used to answer RQ2—the NRS and comScore—are the same as those employed by the PADD data we queried to answer RQ1. However, in order to find out about changes in the time spent with The Independent after it went online-only, it was necessary to use different variables and combine the data in different ways. To calculate the time spent reading The Independent in print in the 12 months before it went online-only, two variables were used from the NRS print survey: time spent reading and readership. Calculations were made that involved the number of weekdays, Saturdays, and Sundays in the 12 months up to The Independent’s last print edition, the average number of readers on those days, and the average minutes of reading time per reader on those days. 2

It should be noted that print readership figures based on recall-based surveys, such as the NRS, may be subject to over-estimation, although Shepherd-Smith (Citation1999) believes that one cause—replication—is “less likely to occur for daily newspapers” and “worst with magazines”. Furthermore, the accuracy of self-reported data on time spent reading newspapers—as collected by the NRS—has been called into question, for example due to evidence that different measurement methods produce different results (Shoemaker, Breen and Wrigley Citation1997). comScore provided data on the total minutes spent by British adults with The Independent’s online editions (including i100/indy100) for the 12 months before and after the title quit paper and ink. comScore uses a methodology that integrates data collected from a sample of panellists—over 80,000 in the UK (Vit Smékal, personal communication, 20 July 2017)—with “server-centric census data” that is collected via the use of “tags” that publishers place on their websites and mobile apps (comScore Citation2013, 2). 3 Panellists’ online consumption—including time spent—is monitored by software installed on their PCs, smartphones, or tablets. Some of the limitations of comScore’s methodology are discussed in Thurman (Citation2017, p 1414–1415).

Our method of directly comparing data from the NRS and comScore, reflects worldwide trends in audience measurement. Integration of recall-based print survey data with online consumption data collected via online panels and tagging is now done in at least 23 countries by the market researchers responsible for the measurement of news and magazine brands (Page, Citation2017). We do not mean to imply that such comparisons and integrations—including ours—do not have shortcomings, but rather that many now agree that it is advantageous to utilize a combination of methods to measure the very different activities that are print and online reading.

International Appeal

To answer RQ3, data on The Independent’s international audience was acquired from the UK’s Audit Bureau of Circulations (ABC). The ABC publishes the number of UK and overseas unique browsers and page impressions recorded by some—but not all—UK newspapers. The data originates from publishers’ own server logs but is audited by the ABC to ensure it conforms to a common set of standards and is, therefore, comparable across outlets and longitudinally. For a discussion of limitations pertaining to the data ABC audits see Thurman (Citation2014, p 160). 4

Results

RQ1: How did the net monthly British readership of The Independent change when it stopped printing and went online-only?

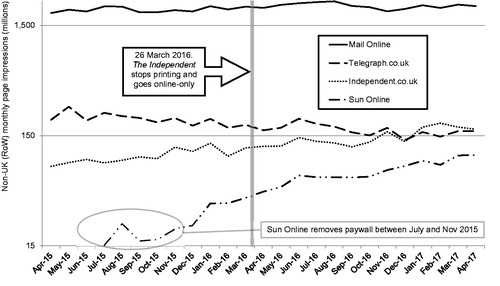

The results show a small increase 5 (of 7.7%) in net monthly readers in the 12 months after The Independent went online-only compared with the 12 months before (see ). Mobile-only readers dominate. They made up 62% of monthly readers in the 12 months before The Independent went online-only, and 77% in the 12 months after. Furthermore, the number of mobile-only readers has grown significantly since the title went online-only: by 31%. This increase more than made up for the loss of print-only readers.

Figure 1 Net (deduplicated) monthly British readership (aged 15+) of The Independent in the 12 months before and the 12 months after it stopped printing and went online-only. For the period April 2015–March 2016 a multiplatform reader is defined as one who read The Independent via print & PC, or print & mobile, or print, PC, & mobile, or PC & mobile. For the period April 2016–March 2017 a multiplatform reader is defined as one who read The Independent via PC & mobile. Source: NRS PADD

RQ2: How did the attention (expressed in time spent reading) received by The Independent from its British audience change after it stopped printing and went online-only?

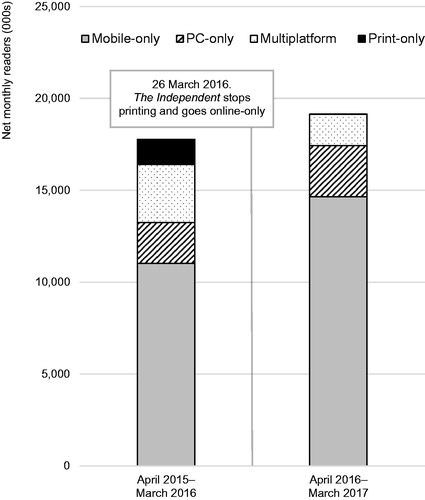

Despite increases in net monthly readership, our results show a dramatic drop in the attention received by The Independent from its British audience after it stopped printing and went online-only (see ). We estimate that, in the 12 months before the switch, its print editions were responsible for 81% of the time spent with the brand by its British readers, and the online editions just 19%. After the switch, the attention it received via PCs and mobiles changed little. Although there was a rise in attention in June and July 2016 likely due to the Brexit referendum and its aftermath—a pattern observed at other UK news sites—those gains fell away over the rest of 2016, only rising again in early 2017. Comparing the time spent with The Independent’s digital editions in the 12 months after its move to online-only against the 12 months before shows an increase of less than half a percent. We estimate the total attention received by the brand in the 12 months up to the cessation of its print editions was 5.548 billion minutes, compared with 1.056 billion minutes for the 12 months after, a fall of 81%. 6

Figure 2 Changes in the total attention (measured by time spent reading) received by The Independent from its British audience before and after it went online-only. Figures are for readers aged 15+. Print reading time is a monthly average for the period April 2015–March 2016. Online reading time includes both independent.co.uk and indy100/i100. For notes on the time spent online by Northern Irish users and by those aged 15–17 via mobile, see online Supplemental Data. Sources: NRS and comScore

RQ3: How has the international traffic (expressed in unique browsers and page impressions) attracted to The Independent’s online editions changed since the title went online-only?

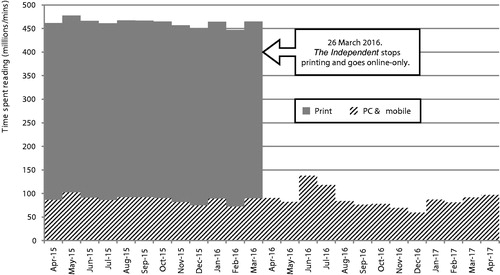

The Independent has achieved growth in unique browsers from overseas since its decision to go online-only. Its total was 50% higher in the 12 months after it went online-only, compared with the 12 months before. By comparison, The Telegraph 7 saw no significant change and The Mail 8 only registered a small increase (6.6%). There was also significant growth at the tabloid Sun, but its figures are not directly comparable, because of its decision to remove its paywall in 2015 (see ).

Figure 3 Number of monthly overseas unique browsers at four UK online newspapers, April 2015–April 2017. Source: ABC

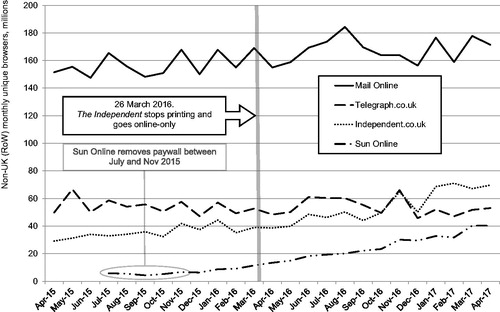

The Independent recorded a similar increase (47%) in non-UK page impressions over the same period. By comparison, The Telegraph recorded a drop, of 20%, and The Mail a modest increase, of 8% (see ).

Discussion

The modest rise in The Independent’s net British readership in its first year post-print was driven by a 31% rise in mobile-only readers. Can this rise in mobile-only readers be attributed to the move to online-only or is it part of a wider trend? The Independent’s owner, Evgeny Lebedev, appears to favor the former hypothesis, saying that “by going online-only we freed ourselves from the unwieldy infrastructure of print, and allowed ourselves to be far more flexible … nimble and digitally focused [to] better serve our new, much bigger audience online” (Bond Citation2016). To examine whether the rise in mobile-only readers at The Independent reflects its new online-only status or is part of a wider pattern, we analyzed changes at 12 other UK newspaper brands over the same time period (see Tables A and B in online Supplemental Material).

The results show that the growth in mobile-only readers at The Independent is actually lower than the average (143%) for the other dozen newspaper brands, all of which retained print editions. However, this average is raised by a large increase in mobile-only readers at The Sun (1073%) due to the removal of its paywall during this period. Nevertheless, The Mirror and The Standard have seen steeper rises in mobile-only readers, and four other newspaper brands, The Telegraph, The Express, The Mail, and The Metro, have seen similar rises. This comparison suggests that rises in mobile-only readers at The Independent are part of a general trend rather than the result of the increased “digital focus” and “flexibility” that Lebedev claims the newsroom now enjoys (Bond Citation2016).

Static Reach, Plummeting Attention

What does distinguish The Independent from its competitors is its now total reliance on online readers, in particular those accessing the brand from mobile devices. This reliance helps explain how, as we estimate, The Independent saw a small rise (7.7%) in monthly British readers in its first year post-print, at the same time as seeing the total time spent with the brand by those readers fall by 81%.

Although in its first year post-print The Independent had slightly more readers, the print readers lost were, compared to the online readers gained and retained, very much more frequent and attentive consumers. In the 12 months up to its final print edition, 50% of readers of The Independent’s Monday–Saturday print editions read them “almost always” (i.e. every day), with 35% reading them “quite often” (NRS Citation2016a). By contrast, in September 2016 online visitors to The Independent’s mobile apps and websites visited an average of just twice a month (comScore Citation2016). And, while The Independent gets an average of 4.6 min per month from every UK user of its online editions (ibid.), its weekday print edition was read for an average of 37 min per issue per reader, with longer durations for its Saturday and Sunday print editions: 48 and 50 min, respectively (NRS Citation2016b).

International Appeal

Counter-intuitively, perhaps, The Independent achieved more growth in non-UK unique browsers and page impressions after it went online-only than it did from its home market (see ), despite the fact that the print product was already unavailable overseas. 9 It might have been expected that greater online growth would have occurred in the market from which the print product disappeared than in the market where it was already absent. So, what might explain this overseas audience growth? One hypothesis is that the cause is organizational change within The Independent, related to its move to online-only. Another is that the change reflects wider patterns.

TABLE 1 Growth in unique browsers and page impressions from the UK and overseas registered by The Independent in the 12 months after it stopped printing compared with the 12 months before. Source: ABC

When announcing their decision to go online-only, The Independent’s management talked about their “global ambitions” for the title, saying that they really wanted to “take advantage” of their new status (Sweney and Johnston Citation2016). It has been reported that The Independent has “pledged” to open “new editorial bureaux in Europe, the Middle East and Asia” (ibid.) and that the size of its US editorial team would double “from six to 12” (Ponsford Citation2016).

In an attempt to analyze the plausibility of these hypotheses, we can look at the data presented in and in more detail. We see no immediate change in The Independent’s post-print international unique browsers. Browsers do rise, however, in June 2016. This is in line with trends at all three of the other UK online newspapers featured in , and is almost certainly a result of international audiences’ interest in the Brexit vote and its aftermath. The second significant jump in browser numbers is in November 2016, the month of the US presidential election. This “Trump Bump” (Bond Citation2017) is also evident at The Telegraph and The Sun, although not at The Mail (see ).

There is also no immediate change in The Independent’s post-print international page impressions. There is, as with unique browsers, a “Brexit Bump” in page impressions, in common with The Telegraph and The Sun, as well as a Trump Bump, although, compared with The Telegraph’s, The Independent’s Trump Bump starts earlier and is maintained longer after the quiet holiday month of December (see ).

There is, therefore, some evidence to suggest that The Independent, as its management hoped, has been able to go some way towards achieving its “global ambitions”. The extent to which the growth in its international audience can be attributed to any post-print overseas editorial expansion is something we are not able to answer, in part because we do not know if such an expansion has actually taken place. Even if it has, we would caution against crediting it as the sole cause of The Independent’s overseas audience growth.

One reason why The Independent may have benefited from the Trump Bump more than some of its UK rivals (such as The Telegraph) is the fact that it has long had a following in the US. For example, in the mid-noughties it had a higher proportion of online readers from the US (73%) than nine other UK online news outlets (Thurman Citation2007). Furthermore, its strong anti-Trump stance—in an editorial 3 days before the US presidential election it wrote that Donald Trump “is a man of breathtaking ignorance, vanity and shallowness” (Independent Citation2016b)—may have been a more successful strategy in the extremely polarized US media market than the ambiguous stance taken by The Telegraph (see, e.g., Telegraph Citation2016).

Conclusion

In this study we estimate that The Independent’s British readership grew 8% in the first 12 months after it went online-only, but also that the total time spent with the brand by those same readers fell 81%. Although, post-print, there was a dramatic fall in attention for The Independent from readers in its home market, there was also a 50% increase in overseas browsers. However, due to a general rise in news use over the same period, the effect—if any—of going online-only on The Independent’s international traffic is difficult to isolate.

One possible limitation of this study is the use of self-report data to measure print reading. Some studies (see, e.g., Prior Citation2009)—although not others (see, e.g., Pellegrini et al. Citation2015)—have found that people over-report their own news consumption. We do not believe, however, that any potential over-reporting changes the direction of the findings we present here. The change in time spent is so large—and the time spent online has changed so little—that attention almost certainly fell after the move to online-only.

Further research could investigate what print readers of The Independent did after the online-only switch. Given that net readership numbers have remained broadly static, it is possible that some former print readers of The Independent started using the brand online. But, given that the time spent with The Independent’s digital editions by its British audience barely changed post-print, any who did switch appear not to be using the brand’s digital products with anything like the same intensity as they used its printed editions. Another possibility is that some readers moved to The Guardian—the only other newspaper with a similar reader profile to The Independent that increased its print readership in the 12 months following The Independent’s move to online-only.

Post-print, The Independent’s reach has increased but the attention it receives has been decimated. What does this mean for its influence? Its ongoing broad reach means that The Independent is likely to continue to be a widely recognized news source. Politicians and others will carry on caring about the content it carries because of its ability to reach a large number of people, both at home and abroad. However, we believe that influence is also generated through the attention a newspaper brand can attract. The Independent may have more readers, but it also has fewer devotees, and is now a thing more glanced at, it seems, than gorged on. This moves The Independent closer to the sidelines than it used to be. It has sustainability but less centrality.

The case of The Independent is an extreme example of the wider decline in attention paid to newspapers as more and more news consumption takes place online (Thurman and Fletcher Citation2017). This matters both for newspapers’ influence and their profitability, but there are likely to be consequences for wider society too. Newspapers perform valuable democratic functions, including informing the public and, directly or indirectly, encouraging civic and political participation. It is difficult to see how these outcomes—which many would see as generally positive—can be achieved to the same degree if reading continues to be replaced by glancing and other low-intensity news consumption practices. We believe scholars, regulators, and politicians need to think carefully about the differences between print and online news consumption—and the societal role of newspapers—as print consumption and its attendant attention wanes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary material is available for this article at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/suppl/10.1080/21670811.2018.1504625?scroll=top.

Supplemental Data

Download MS Word (20.1 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Neil Thurman

Neil Thurman (author to whom correspondence should be addressed), Department of Communication Studies and Media Research, LMU Munich, Oettingenstr. 67, 80538 Munich, Germany; and Department of Journalism, City, University of London. E-mail: [email protected] Twitter: @neilthurman. Web: www.neilthurman.com

Richard Fletcher

Richard Fletcher, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford, UK. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

2 Because time spent reading is additive, there was no need to go through the fusion process adopted by PADD to eliminate the double-counting of print and online readers.

3 The Independent’s mobile apps appear not to carry comScore tags, which means comScore’s data on the use of The Independent’s mobile apps comes exclusively from its mobile panels.

4 Unlike the NRS PADD and comScore data, which is based on counts of known panellists, the ABC data on unique users may be subject to inflation due to cookie deletion and multidevice access. However, because we are interested in making comparisons between brands, and between home and overseas markets, any such inflation should not alter significantly the trends we find.

5 This initial gain appears to have been lost in the second year of The Independent’s online-only existence (Thurman and Fletcher Citation2018).

6 Thurman and Fletcher (Citation2018) estimate that in the second year of The Independent’s online-only existence time spent with the title rose but is still around 70 per cent below the level achieved during the brand’s final 12 months with both print and online editions.

7 Like The Independent a UK “quality” newspaper brand, although with a more conservative editorial stance.

8 A “mid-market” UK title that has a more conservative political stance than The Independent but publishes high volumes of celebrity news and other popular content online.

9 The Independent halted overseas print distribution in October 2011.

REFERENCES

- Barnhurst, Kevin G. , and Ellen Wartella. 1991. “Newspapers and Citizenship: Young Adults’ Subjective Experience of Newspapers.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 8 (2): 195–209.

- Bentley, Clyde . 2001. “No Newspaper Is No Fun—Even Five Decades Later.” Newspaper Research Journal 22 (4): 2–15.

- Berelson, Bernard . 1949. “What ‘Missing the Newspaper’ Means.” In Communication Research 1948–1949, edited by Paul F. Lazarsfeld and Frank N. Stanton , 111–129. New York: Harper.

- Bond, David . 2016. “Independent Returns to Profit after Axing Newspaper.” Financial Times, October 19. Retrieved from: https://www.ft.com/content/da99890a-91fb-11e6-a72e-b428cb934b78?mhq5j=e1.

- Bond, Shannon . 2017. “CNN and New York Times Boosted by ‘Trump Bump’.” Financial Times, May 3. Retrieved from: https://www.ft.com/content/99039bc0-3011-11e7-9555-23ef563ecf9a.

- Cathcart, Brian . 2016. “The Independent Ceasing to Print Would Be the Death of a Medium, Not of a Message.” Guardian. February 11. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/feb/11/independent-ceasing-print-death-medium-not-message.

- Companies House. n.d.-a. “Independent Print Limited.” Accessed 1 August 2017. https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/company/07148379/filing-history.

- Companies House. n.d.-b. “Independent Digital News and Media Limited.” Accessed 1 August 2017. https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/company/07320345/filing-history.

- comScore . 2013. “comScore Media Metrix Description of Methodology.” November. http://www.journalism.org/files/2014/03/comScore-Media-Metrix-Description-of-Methodology.pdf.

- comScore . 2016. Data downloaded from comScore website. Subscription only.

- Crewe, Ivor , and Brian Gosschalk , eds. 1995. Political Communications: The General Election Campaign of 1992. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- De Waal, Ester , and Klaus Schoenbach. 2010. “News Sites’ Position in the Mediascape: Uses, Evaluations and Media Displacement Effects Over Time.” New Media & Society 12 (3): 477–496.

- Groves, Jonathan , and Carrie Brown-Smith. 2011. “Stopping the Presses: A Longitudinal Case Study of the Christian Science Monitor Transition from Print Daily to Web Always.” #ISOJ 1 (2): 86–129.

- Hollander, Barry A. , Dean M. Krugman , Tom Reichert , and J. Adam Avant. 2011. “The E-Reader as Replacement for the Print Newspaper.” Publishing Research Quarterly 27 (2): 126–134.

- Independent . 2016a. “The Independent Becomes the First National Newspaper to Embrace a Global, Digital-Only Future.” Independent. February 12. Retrieved From: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/media/press/the-independent-becomes-the-first-national-newspaper-to-embrace-a-global-digital-only-future-a6869736.html.

- Independent . 2016b. “Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump? The Independent View on Who Should Win the US Presidential Election.” Independent. November 5. Retrieved from: http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/editorials/donald-trump-hillary-clinton-us-presidential-election-the-independent-view-editorial-a7399646.html.

- Independent Digital News and Media. 2016. Annual Report and Financial Statements 02 October 2016. https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/company/07320345/filing-history.

- NRS . 2016a. “Reading Frequency. April 2015–March 2016.” Excel file downloaded from NRS website. Subscription only.

- NRS . 2016b. “Source of Copy and Time Spent Reading. April 2015–March 2016.” Excel file downloaded from NRS website. Subscription only.

- Page, Katherine . 2017. “Latest Developments in Audience Measurement: The PDRF 2017 Review of Audience Research.” https://www.pdrf.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/papers/13_new.pdf

- Pellegrini, Pat , Debbie Bradley , Karen Swift , and TraShawna Boals. 2015. “Cross Platform Media Measurement: Mobile and Desktop Online Measurement Comparisons.” Paper presented at the PDRF 2015 Symposium, London, October. https://www.pdrf.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/10_Syn43Pellegrini.pdf.

- Ponsford, Dominic . 2016. “Editor Christian Broughton on Why the Future Is Finally Looking Bright for The Independent.” Press Gazette. May 9. Retrieved from: http://www.pressgazette.co.uk/editor-christian-broughton-on-why-the-future-is-finally-looking-bright-for-the-independent.

- Prior, Markus . 2009. “The Immensely Inflated News Audience: Assessing Bias in Self-Reported News Exposure.” Public Opinion Quarterly 73 (1): 130–143.

- Shepherd-Smith, Neil . 1999. “The Ideal Readership Survey.” Paper presented at the Worldwide Readership Research Symposium, Florence, Italy. https://www.pdrf.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/560.pdf

- Shoemaker, Pamela J. , Michael J. Breen , and Brenda J. Wrigley . 1997. “Measure for Measure: Comparing Methodologies for Determining Newspaper Exposure.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Israel, July 1998. https://dspace.mic.ul.ie/handle/10395/1428

- Sweney, Mark , and Chris Johnston. 2016. “Independent Aims to Keep Stars and Boost Quality in Digital Shift.” Guardian. February 12. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/feb/12/independent-aims-to-keep-stars-and-boost-quality-in-digital-shift.

- Telegraph . 2016. “A Weak White House Is Bad for the World.” Telegraph.co.uk, November 8 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/opinion/2016/11/08/a-weak-white-house-is-bad-for-the-world.

- Thurman, Neil . 2007. “The Globalization of Journalism Online: A Transatlantic Study of News Websites and their International Readers.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 8 (3): 285–307.

- Thurman, Neil . 2014. “Newspaper Consumption in the Digital Age: Measuring Multi-channel Audience Attention and Brand Popularity.” Digital Journalism 2 (2): 156–178.

- Thurman, Neil . 2017. “Newspaper Consumption in the Mobile Age: Re-assessing Multi-Platform Performance and Market Share Using ‘Time-Spent’.” Journalism Studies 19 (10): 1409–1429.

- Thurman, Neil , and Merja Myllylahti. 2009. “Taking the Paper Out of News: A Case Study of Taloussanomat, Europe’s First Online-Only Newspaper.” Journalism Studies 10 (5): 691–708.

- Thurman, Neil , and Richard Fletcher. 2017. “Has Digital Distribution Rejuvenated Readership? Revisiting the Age Demographics of Newspaper Consumption.” Journalism Studies. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1397532.

- Thurman, Neil , and Richard Fletcher . 2018. “Save Money, Lose Impact.” British Journalism Review 29 (3) 31–36.

- Usher, Nikki . 2012. “Going Web-First at The Christian Science Monitor: A Three-Part Study of Change.” International Journal of Communication 6: 1898–1917.