Abstract

Since its release in August 2009, WhatsApp has played a key role in the fast development and expansion of the contemporary polymedia environment within which humans interact with each other. Those in the media, and journalists in particular, have taken to this platform to use it as a way to share and receive information as well as to maintain regular, and sometimes more private, contact with their sources. The goal of this paper is to examine the incentives that underlie journalists’ decisions to turn to WhatsApp and the consequences that this mobile chat application has had on the newsmaking practices of reporters inside two Chilean newsrooms. Newsroom ethnography, including participant observation, is employed in this study to gain insight into journalists’ routines and their everyday usage of WhatsApp. The conclusions of this article suggest that the utilization of WhatsApp has impacted the relationship between journalists and sources both on a personal and professional level. New perceptions of intimacy and trust, camaraderie and obtainability, and temporality are observed among the journalists who use this application. These observations carry important professional and ethical implications for journalists navigating today’s media ecology, and show how technological and socioprofessional aspects are tightly interwoven.

Introduction

Mobile instant messaging (MIM) applications are now understood as an essential component of everyday communication routines (Andueza and Perez Citation2014). Unlike SMS or Short Message Service from 20 years ago, applications such as WhatsApp allow their users to send and receive not only text, but also to share real-time locations, images, voice recordings, documents, and videos (Church and de Oliveira Citation2013). These communication modalities are available both in one on one interactions or, just recently, within groups of up to 250 people. As a result of the former, the notion that WhatsApp is “‘just a few friends connecting’ […] seems to have gone out the window” (Armstrong Citation2018). Indeed, with the massification of personal mobile phones and the low cost of mobile data prices, WhatsApp should be considered as a social network that allows its users to access countless pieces of information very fast (Bouhnik and Deshen Citation2014). Yet, the rapid increase in the consumption of data produces tenseless conceptions of action, where the temporality of some activities gets reduced to an immediate and atemporal now.

MIM applications penetrated deep into the way we communicate with each other in what Malka, Ariel, and Avidar (Citation2015) have called a “unique combination of mass and interpersonal communication channels” (329). The intrusion in people’s lives has been so dire that a great deal of research has been conducted regarding the link between the use of this app and new types of addictions and disorders (van den Eijnden et al. Citation2016; Faye et al. Citation2016; Rajini et al. Citation2018). However, instead of working as a deterrent, the significant effect that WhatsApp has had seems to uniquely attract journalists. Those working in media are willingly agreeing to participate in these virtual relationships with sources. Indeed, WhatsApp has spread ubiquitously throughout countries and newsrooms. Some authors have produced meaningful research on the use of this MIM by journalists in nondemocratic contexts. Previous research has shown how WhatsApp has become a substantial tool for journalists and their sources in places in which if state agents were to access off the record conversations, reporters could face indefinite incarceration or even disappearance (Craig Citation2017). Similarly, Frère (2017) reports how “Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp have become the main conveyors of information and the location for debate” (6) in what she calls the impossibility of journalism in Burundi, a country where the situation for journalists continues to deteriorate and new sanctions against media organizations are enacted regularly.

WhatsApp might be perceived as a safe app because since 2014 the application has used end-to-end encryption (E2EE) technology, which allows for “data between communicating parties to be secure, free from eavesdropping, and hard to crack” (Endeley Citation2018, 96). WhatsApp users are also allowed to check if their messages have been received properly and read by the addressee when two blue check marks appear next to the sent information. Added to the improvements on the E2EE technology, keeping track of the delivery of the information allows senders to be sure that messages are received correctly and privately without fearing that anyone might have intercepted the communication. It should be noted, nonetheless, that this sentiment is not shared by all journalists (see Waters Citation2017).

However, despite previous studies, there is still much to examine about the use of this application by journalists in more democratic contexts: Why and with which purpose do journalists in Western democracies use this MIM? What are the advantages of using WhatsApp versus telephone calls or face to face conversations? An analysis of the existing literature shows that only a limited number of publications explore the interactions between journalists and their sources using this platform (e.g., Belair-Gagnon, Agur, and Frisch Citation2017; Negreira-Rey, López-García, and Lozano-Aguiar 2017; Belair-Gagnon, Agur, and Frisch Citation2018; Sedano and Palomo Citation2018). However, Negreira-Rey, López-García, and Lozano-Aguiar (Citation2017) examined only the strategies and content of the messages that Spanish media use to spread news via WhatsApp and Telegram, while Belair-Gagnon, Agur, and Frisch research (2017, 2018) dwelled on how WhatsApp is being used for reporting by foreign correspondents and how the relationships of trust between journalist and source are built. Thus, some questions arise concerning how digital tools such as WhatsApp have modified the relationship between journalists and their sources and how these new technologies have hindered or facilitated the routines with which news needs to be reported.

Therefore, in this paper I show that the widespread use of mobile chat applications by Chilean journalists has impacted the newsmaking process in at least three ways; (1) by transforming the temporality of the journalistic routine, under which (2) new relationships with high degrees of intimacy between journalists and sources have been created, and (3) new levels of mutuality and comradery in the communications between different journalists have been established.

Drawing on Ian Hodder’s human-thing entanglement theory (2011, 2014), this article proposes to think about this issue beyond the mere relationship between user and new technology. For Hodder (Citation2011), the relationship between people and things can create specific practical entrapments that occur because “we have come to depend on the positive benefits deriving from the greater flows of resources and information through the network” (164). In this case, Hodder’s theory sheds some light onto the asymmetrical and dependent relationship between journalists and WhatsApp, a social media platform that functions as a digital intermediary with an always growing number of performance characteristics. This approach is not to deny the possible positive outcomes of this link, but to be wary of the entrapments inherent in the individual-object relationship. For Hodder (Citation2014), “humans get caught in a double bind, depending on things that depend on human” (20), leading to a co-dependency between things and humans, where each one cannot carry on without each other, as in the case of WhatsApp. And the longer and deeper the relationship goes, the more difficult it is to detach itself from one another.

The Link between Technology and Journalism

Trist (1981) argues that media are a socio-technical system. For Trist, primarily socio-technical organizations, such as the media institutions journalists inhabit, rely mainly on their materiality and resources in order to produce their outputs. They can only function as the result of the relationship between a nonhuman system and a human system. That is, they ineluctably require a technological element to transform their input into output. And when those elements evolve, “values, cognitive structures, lifestyles, habitats and communications” (11) evolve as well. In his argument about the Actor-Network-Theory (ANT), Bruno Latour (Citation2005) endows these technological elements with agency: “any thing that does modify a state of affairs by making a difference is an actor—or, if it has no figuration yet, an actant” (71, emphasis in original). If action is only that which is intentional, he argues, then no thing would escape the material realm of human interactions. But if the limits of agency are broadened, then objects that participate in the modification of something else can be viewed in the domain of social relations. By using an approach based on ANT, previous studies have demonstrated “how change is a process of constant negotiation between the journalists, the tools they use and other members of news organisations in charge of strategic decisions, […] through everyday interactions and practices” (Domingo, Masip, and Costera Meijer Citation2015, 55). Indeed, as Domingo et al. continues, by putting the emphasis not on institutions but on the journalistic’ practices and the actors that interact with each other during the production of news, “the black boxes of normative definitions of journalism and democracy” (64) are open.

And thus, we arrive at the question of how the agency of humans and things condition such relations. For example, Chambers (Citation2017) wonders how services such as Facebook have changed the meaning of friendship and the nature of intimacy itself. In her article, she concludes that Facebook’s friendship narratives actually encourage its users to disclose sensitive and sometimes personal information. Given that the platform itself emphasizes users continuous’ self-disclosure, it is expected that certain intimate traits are offered via public connections. Turkle (Citation2011) goes even further and argues that under the bedazzling light of modern technological communication, our sense of intimacy and privacy are forever gone: “We need to put [technology] in its place. […] The prospect of loving, or be loved by, a machine changes what love can be” (295). But, then, what and where is the place of technology?

Hodder (Citation2014) reasons that our own evolution is conditioned by human dependency on technological innovations. Our relationship with things is inescapable, for our physical and cognitive capacities endlessly seek to entangle themselves with the surrounding world; “humans and things are relationally produced” (19), he argues. He describes the entanglement of human and technology as follows: (HT) + (TT) + (TH) + (HH). That is, humans depend on things (HT), things depend on other things (TT), things depend on humans (TH), humans depend on humans (HH). And it is precisely the concept of dependency—implying different degrees of asymmetry—that makes Hodder’s theory so adequate to study the technological transformation currently happening in journalism.

Technologies inside the newsrooms, those socio-technical organizations according to Trist, are changing, and journalism is changing with them. Some authors argue that the situation in journalism is “changing so rapidly that it is difficult to get a sure sense of what is going on” (Lemann Citation2013). As Peterson (Citation2003) suggests, it is the constant relationship between the context of production, that is, a particular time and place, and the characteristics of media technologies which end up mediating public and mass communication. That is, the way mass communication occurs is closely intertwined with the technological transformations and economic conditions in which the communication system operates. For example, Nielsen and Ganter (Citation2018) found that even though Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube were originally focused on user-generated content, today these social networks work effectively as “intermediaries” between the audience and well-established publishers.

The challenges that journalism is facing upon the introduction of new technologies has been described as sharply binary (Butler Breese Citation2016). On one hand, it has been argued that some journalists have “put up a furious resistance, adamantly refusing to subordinate their sacred professional ethics and idealistic civic morals to what they see as the profane, polluting logic of market and technology” (Alexander, Breese, and Luengo Citation2016, 13). It also has been argued that the inclusion of new technologies in the newsrooms is causing high levels of distress because they are constantly changing professional practices and blurring the lines between different journalistic genres (Erdal Citation2007). On the other hand, however, Boczkowski (Citation2005) has suggested that journalists who write for digital-only publications exhibit an “occupational identity that resembled the one of their print counterparts, as defined partly by a traditional gate-keeping function and a disregard for user-author content” (103). In the same line, Singer (Citation2005) concluded that journalists are normalizing new technologies during the newsmaking process, maintaining certain journalistic norms and practices. In some contexts, therefore, journalists might be abiding to the technological transformations happening around their ecosystem.

With new media also comes new economic structures. Livingston and Bennett (Citation2003) argue that the economic pressures imposed by this technological model of production is threatening “traditional gatekeeping based on reporter judgment and professional editorial standards that define the quality of news organizations” (364). As Cottle and Ashton (Citation1999) alerted, technological convergence inside media organizations is causing a drastic reconfiguration of broadcast newsrooms, at the same time that is transforming traditional professional practices. The allocation of resources has changed in recent years, creating new work teams within newsrooms and de-skilling or simply eliminating others.

New technologies might be threatening traditional journalism, as Livingston and Bennett suggest. But I will argue that journalism is often in a state of transition, of crisis, or under threat, for socio-technical organizations have always been shaped by the technologies on which they are based upon (Loosen Citation2015; Primo and Zago Citation2015). From industrial print, to radio waves, to WhatsApp groups, journalism cannot resist the impulse of occupying new spaces for mass communication; because journalism is in itself a synonym for mass communication. With the invention of each new information technology, apocalyptic critics have foretold the end of journalism. But in fact, as more and more information is available for consumption (Gynnild Citation2014), we rely more and more on modern news organizations (McNair Citation2006). And today, as Mitchelstein and Boczkowski (Citation2009) argue, online news media is at the core of the social, economic, and cultural life of many. Within this framework, journalists and reporters in contemporary societies play the role of chief sense-makers (Patterson Citation2013).

It is in this context that WhatsApp became the chat application du jour. According to the Global Digital Report of 2018 (Kemp Citation2018), WhatsApp has reached 1.3 billion users globally, which makes it the most used chat application along with Facebook Messenger. Particularly, and according to the same report, Chile is an interesting case since the active mobile social users in the country reaches 13 million people, out of 18 million. This represents a 72% penetration of mobile social media users in the country, statistically larger than the U.K. (57%), U.S. (61%), and China (65%). And yet, the specific patterns of use are invisible to an outsider. This increased in active mobile user correlates with the boom of WhatsApp as one of the top social media for news consumption in Chile. According to the Reuters Institute Digital Report 2018 (Newman et al. Citation2018), 36% of surveyed people in Chile said they were using WhatsApp for news consumption, compared with 4% in the United States or 5% in the United Kingdom.

Going inside the newsroom becomes imperative to observe how the ubiquitous global influence of WhatsApp is being adapted by journalists, and how this MIM is creating new forms of interdependencies through new innovations inside media organizations. After my arrival to the newsrooms where I conducted my ethnographic work, I started wondering if WhatsApp was a complement to the newsmaking machine, or it was now an essential part of it.

Methodological Approach

As Klinenberg (Citation2005) argued, unless scholars go inside the newsroom to observe how journalists construct their stories, all they can do is speculate about the processes that take place on the newsroom floor. For seven months,1 I worked, observed, and participated on a daily basis inside two newsrooms. The fieldwork took place in the newsrooms of La Tercera, the second biggest national newspaper in Chile, and Teletrece, the news department of Canal 13 television news. This decision was based on the opportunity to observe how both television and newspaper journalists work with this non-physical information technology. Both television reporters and newspaper journalists create news content, but they do so with different technological infrastructures, temporalities and forms.

But while access to the newsroom is one thing, much more complicated is to gain journalists’ trust. According to Reich (Citation2006) there is an obvious difficulty when academic interviewers are trying to interview professional interviewees. Journalists can easily predict which is the right answer that the interviewers are looking for and slide into certain degrees of heroism. Not only that, but the language or parlance used by social scientists such as “making the news” or “social construction of reality” often becomes offensive to journalists and others who work in media (Gieber Citation1964; Schudson Citation1989). This happens because the socially negative connotation might suggest journalists are interfering in a biased way with the construction of the news, which undermines some of the most important ethical standards in journalism such as professionalism, objectivism, detachment and non-involvement with the news (Hanitzsch et al. Citation2010).

According to Reich (Citation2006), another problem might be the demand for confidentiality inside the newsroom. This often translates in the denial from the editors in chief to allow an external investigator to wander freely inside the newsroom, especially since “it appears that mainstream news organizations increasingly refuse to open their gates to outsiders” (501). Hannerz (Citation2012) also noted this problem when interviewing foreign correspondents: “I have tried to make the point that I do not intend it as an attack on their work and its products. Indeed, journalists often have a reasonable suspicion that academics generally are inclined to be critical of news work and sometimes to forget the implications of such constrains as deadlines and space limits” (2004, 8). But the political overtones that this kind of research could have are inescapable. The researcher must be aware of the consequences and possible weaponization of this line of research.2

This research builds on previous news ethnographies such as Herbert Gans’ (Citation1979) Deciding What’s News and Gaye Tuchman’s (Citation1978) Making News. However, a very specific methodological difference between these studies and the one I present here should be noted. Unlike Gans, who looked at the unwritten rules journalists applied during the elaboration of news pieces, which he would later called considerations, Tuchman sat on the television stations and “watched the process of assigning tasks, sat in on editorial discussions, covered stories with reporters, and followed stories through their eventual dissemination” (10). But like Gans, she recognizes that at moments she was “barely tolerated” (11) in the press room. I argue that this happened because both of them observed, but neither participated. Inevitably, they were on the way, disrupting the normal pace of work and the dynamics with which journalists move within the newsroom. But this is where my position as a journalist with a background in news reporting was useful when building trusting relationships with editors and journalists. During the seven months of my fieldwork, I worked as a journalist; which included daily reporting, writing pieces for the web platform and the newspaper, cultivating relationships with sources, and chasing my own stories to include in the agenda. That also meant that, with time, I was seen less as an external researcher and more as peer. I was not only able to observe how journalists worked every day inside the newsroom, but I was also invited to join WhatsApp groups. Since I did not go into the newsrooms with the idea of researching the usage of the WhatsApp app in particular, it was here when I saw for the first time this app’s ubiquity, even over other platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, and how it was shaping Chilean journalists’ work. Within these groups, journalists from the media I was working for at the moment were made aware of my position as a researcher, which cannot be said for every other external journalist in those same WhatsApp groups. However, the data gathered from every group, either internal from the media or external, was treated with the same ethical considerations in order to protect the sources and its positions. The information I gathered from these groups was used later to shape the interviews I conducted towards the end of my stay in each of the newsrooms. The following sections present the results from field notes, interviews, and the everyday interactions observed within these groups and in the newsroom.

A New Temporality for Newsmaking

The double blue check marks in a WhatsApp message can save the day with the same ease that may ruin the night for a journalist. For a breaking-news journalist, some sources “send messages at unusual, ridiculous times. I do not know if it is an assistant, if they are the congressmen themselves … Sometimes 11 at night. I am not lying, 11 at night, 2 in the morning, a message. I do not even read them”3 (Interview, November 24, 2017). However, journalists are aware that not reading the messages could bring serious consequences for their jobs. Those working in media tend to try to ensure an exclusive relationship with a source: “If they have something to say, you want to be the one they tell it to” (Interview, November 24, 2017), a web journalist admitted. And missing a text, could mean that the source might turn to the competition.

Studying time inside a socio-technical organization such as media is always a complex endeavor. First, the concept of time, or what the temporalization of work is, needs to be defined. For Munn (Citation1992) the concept of temporalization sheds light onto the notion of time as a symbolic process which is to produce and reproduce continually in our everyday practices. She leans on this concept to argue that individuals are “in a sociocultural time of multiple dimensions (sequencing, timing, past-present-future relations, etc.)” (ibid). Following Durkheim, she points out the relevance of the study of activity rhythms where time is understood as a continuous process of unfolding activities4. The frenetic activity that the digital age demands from journalists is also cover in Nikki Usher’s (Citation2014) Making News at The New York Times. Usher observed how journalists inside The Times negotiate constantly the challenges of creating online and print content “according to emergent online journalism values: immediacy, interactivity, and participation” (4). She goes on to describe the online rhythms of news production, that is, the urgency for update and refresh the media website in a non-stop loop. Much like Sisyphus’ myth, during my ethnographic fieldwork I observed as well how digital technologies have taken news production to a state of never-ending rolling.

These temporalities and rhythms have been widely discussed in the journalistic field, particularly for the relation between journalism and memory. Souza Leal, Antunes, and Vaz (Citation2013) argue that “by considering journalism as a narrative aimed at presenting a piecemeal knowledge on the world’s current state of affairs […], the relation with the essential elements of the representation and experience of time—the notions of past, present and future—is immediately observed” (108). The authors, for example, argue that when newspapers report about deaths, they are not only talking about something that already has happened, but something that could happen to the reader in the present or describe “possible dying” in the future.

Temporality is central in the study of newsrooms since, as Tuchman claimed, “news media carefully impose a structure upon time and space to enable themselves to accomplish the work of any one day and to plan across day” (41), and where the social ordering of time and space “stands at the heart of organized human activity” (39). News is also a perishable commodity, where “yesterday’s events are washed over by today’s headlines, as the media pursue new news in the race to break a fresh story” (Newton Citation1999, 578). That is, temporality matters inside the newsrooms. And therefore, how WhatsApp might be changing the temporality of the newsmaking process falls equally within the purview of this research.

But there are different types of temporality. The study of time inside the newsroom also refers to that of the interaction between journalists and their audiences. For Gallo (Citation2004), the emergence of weblog journalism implied, between other things, the creation of a real-time virtual feedback loop that broke down the old frontiers that separated journalists and their audience. In journalism, back in the day, the possible response for a certain story could not happen until several days after its publication. However, journalists today live in a feedback rush where their audience comments, shares or expresses different types of emotions to their articles instantly (Thorsen and Jackson Citation2018).

WhatsApp is participating in the transformation of both the rhythm and structures of time. The hyper-speed ability of fiber-optic technology is directly threatening to erase certain journalistic traditions that today do not work fast enough (Willnat and Weaver Citation2018). WhatsApp groups, for example, are faster and more efficient than press conferences. The ability to ask follow-up questions, once considered a must for serious journalists, disappears in order to obtain information quickly and feed it to multiplatform systems awaiting to be refreshed instantaneously.

By conducting participant observation, one can not only watch journalists speed through articles in order to meet a deadline, but the researcher also gets to feel the pressure of time over their shoulders. And when the structure based upon time can be described as “we need to break with that story right now,” WhatsApp becomes a key ally.

Over and over again I saw how WhatsApp was the protagonist in many conversations between colleagues. Often, a journalist would jump into the air, brandishing their phones and screaming about a quote, statistic, or picture they have just received on the app. A scraping of chairs abnormally loud would fill the newsroom as journalists and editors gather around and debate about whether they were in front of another apocryphal story, as many circle around WhatsApp those days. Editors, as inveterate doubters, would grab their phones and reach out to their own sources for confirmation or denial. All of this would happen within minutes, for everybody knew that if they got that piece of information, then most likely than not, another journalist elsewhere might have gotten it as well. Being able to gather information quickly came with the price of transforming the rhythms and structures of time within the newsrooms, and WhatsApp is directly at the center of those changes.

But MIMs are also a reminder of the toll that immediacy takes in journalists’ personal lives. That is, because WhatsApp blurs the lines of intimacy and professional boundaries, and because interpersonal and mass communication are interchangeable concepts within this app, journalists are never off duty. It is a situation where journalists find themselves hostage to the technology they celebrate. Above all, the way the temporalization of journalism is able to change with the introduction of one MIM glaringly exposes the idea that a socio-technical organization depends on the technology itself is based on. It also sheds some light onto how vulnerable journalists confronted with the agency of the things they depend upon in order to report the news.

In the following sections, I will review how the rampant introduction of this MIM not only has impacted on the temporalization of the news production, but also has affected other spheres of journalism, such as intimacy and obtainability.

Intimacy and Mutuality

Soon after my arrival in the first newsroom, the content editor to whom I reported started sending me contacts over WhatsApp. People who I’ve never met or heard of were finding a place between friends and family in my phone. For every article I wrote, colleagues or editors would send me three or four more contacts to use as sources. It seemed to be a tradition to assist neophytes in their endeavor to put together their own pull of political, specialists, and academic sources. Wasting time trying to find a source for an article might exasperate senior colleagues trying to dispatch articles quickly for the web. The instruction was often the same: “send them a WhatsApp message first, if they don’t reply soon enough, well… then call them.” And so, I did. Shortly, responses started coming back. However, to my surprise, these replies contained a big number of smiley faces, thumbs-up, and praying hands (which people actually use to mean “please” or “thank you”). They conveyed the urgency of the topic we were working on or the source’s satisfaction with the article published. Weeks later, upon my request over WhatsApp for an interview, a campaign manager for a presidential candidate just responded with a short “I’m driving,” while a congresswoman simply replied: “Sure. But can we talk later? I’m in the chamber right now.” Two things caught my attention from these interactions. First, I was having access to people very quickly. Both had answered within seconds to my texts. Congressional sessions and road safety rules were not an excuse to miss the chance for an interview. Second, my overly formal texts seemed out of place confronted with such light responses decorated with what today we called emojis. Politicians and academics were responding as if they were texting a close friend. There was a tacit level of intimacy in every chat, very different from the fatigued voices that picked up the phone when I called or the e-mails signed with the perennial “regards.” The behavioural codes, or even the idiom, that ruled over a mobile chat platform like WhatsApp seemed to set the frame under which sources and journalists must interact. But how is this form of communication mediating the way journalists interact with their sources? And how is this affecting the newsmaking process as a whole?

As Kjeldskov et al. (Citation2004) argue, “people have always used artefacts to mediate their intimate relationships” (105). Either by material objects, cultural symbols or non-verbal signals, people have found a way to express an idea or a feeling. However, each medium—or channel of communication—produce different levels of intimacy between its participants. Specifically, research on computer-mediated communication (CMC) shows that people are more likely to engage in high-intimacy self-disclosures in text-based CMC interactions than over face-to-face communication (Tidwell and Walther Citation2002; Gibbs, Ellison, and Heino Citation2006; Jiang, Bazarova, and Hancock Citation2011). According to Walther’s (Citation1996) hyperpersonal model, the reason behind this effect is that “CMC partners may select and express communication behaviors that are more stereotypically desirable in achieving their social goals and transmit messages free of the ‘noise’ that otherwise comes with unintended appearance or behavior features” (28–29). That noise, or the unpredictability of the impulses surrounding interpersonal communication, is limited by the asynchronicity of the posted messages and the constrained number of cues that CMC communication, especially in MIMs, offers to its participants (see Boczkowski, Matassi, and Mitchelstein Citation2018). Partially, the later could explain the use of emojis in the exchanges between sources and journalists. That is, the use of compensatory mechanisms to bypass the limitations of the platform (Kaye, Malone, and Wall Citation2017).

It follows that a higher level of intimacy—or maybe a new kind of relationship—should be expected when journalists begin to interact with their sources not only through face-to-face communication, but also by using text-based mobile chat applications. On their study about journalistic trust-building with their sources over mobile applications, Belair-Gagnon, Agur, and Frisch (Citation2018) concluded that because of the complexity of online communication, mobile sourcing depends in a great deal on social factors. That is, the way in which both journalists and their sources understand the norms, codes, and practices on a given chat app. Indeed, according to a television political reporter, having journalists in their WhatsApp contacts list may present challenges for the sources themselves:

Sometimes [the politicians] believe you are their friend or they feel that they have an edge to pressure you or collect favours. They do not understand that this is journalism and that even if you are building trust with them, it’s a journalist-source relationship. Not a friendship. The format of the app blurs some professional boundaries. (Interview, November 16, 2017)

Political reporters, different from breaking-news reporters, are the ones who need to navigate WhatsApp conversations more carefully. According to the journalists I interviewed, it is not uncommon to build a close relationship with a source. That includes having long conversations where news topics remain untouched: “You have to chat with them, so you joke, they talk about their lives and kids, they ask you how you are doing outside work, and sometimes they really like you” (Interview, November 16, 2017). In that sense, WhatsApp just might be another way to maintain and secure pre-existing relationships with sources. This might contradict the idea that there is a new type of relationship between political journalists and sources. From the information gathered during my fieldwork, political reporters have always engaged with politicians beyond the professional topics of the day in order to gain their trust and hopefully receive exclusive information for a story. It is a relationship where the principle of mutuality, “You scratch my back, I scratch yours,” is better achieved when trust is built in a face-to-face relationship. Indeed, Reich (Citation2008) reports that some journalists preferred oral communication over textual when relating to human informants.

However, the case for web breaking-news journalists is quite different. Having very little time to leave the newsroom during work hours, these journalists often engage in long form conversations with sources they have never met or even talked to over the phone. According to a breaking-news journalist: “contacting them over WhatsApp is the fastest way to obtain quotes. It is very useful to us.” Yet, she admits that the line between what is on the record and what is off the record becomes blurry after long chat conversations.

You have to ask: “Senator, can I use this message as a quote?.” “Yeah, go ahead” [They respond]. But still, a new line between what is off and what is not off is drawn. Get it? The relationship with the source is … different. (Interview, November 24, 2017)

Technically, both journalists and sources (should) assume that every exchange of information or communication is on the record, unless the opposite is clearly stated beforehand (Elliott and Culver Citation1992). However, as noticed during our interviews, quite the opposite happens in WhatsApp: Everything is off the record, unless otherwise noted. The use of emojis in the texts, the informal tone of the responses, and the sense of exclusiveness that chatting with a source seems to have over journalists, confronts them with a myriad of subjective judgements every day. Publishing something from a WhatsApp chat without the source permission might cause the end of the journalist-source relationship even though no ethical rules were broken. Conversely, what would be broken is the tacit intimacy that chat participants assume hover over the platform.

Obtainability

The channels through which information is shared matters as it proscribes who is able to consume it. Even social media precludes those without a stable internet connection to access the information stored within its sites. Traditionally, in journalism there were only two options for a source to share information rapidly to a big number of journalists; a press release was drawn up and then e-mailed, faxed, or delivered to the newsroom (Walters and Walters Citation1992, and see Shoemaker Citation1989), or a source needed to call a press conference, to which journalists would travel to and step on each other in order to get some questions answered (Clayman Citation1993). However, according to the journalists I interviewed, both systems present immediate problems for attendees and sources alike. First, unless a reporter is expecting to receive a piece of information, press releases often get lost in a mountain of other e-mails waiting to be even opened. The communication manager sending the press release would then have to call to each newsroom asking if they had received it and if they had any questions about its content. Second, traveling to places outside the city where the newsroom is located means a lot of time and resources for the media. If the story was not “big enough,” then sending a crew far away cannot be justified. And so, many stories, although important, go by without any coverage. This also highlights the gap between traditional and more resourceful media, and newer and poorer media organizations in the country.

It is difficult to measure the impact that WhatsApp has had in the dynamic information ecosystem where data flows between sources and journalists, but it remains clear that many stories are covered today because they landed safely in a journalist’s phone. According to a web editor, the popularization of information via WhatsApp has several perks, but also presents some challenges:

The same information quickly reaches different media. Some which may have resources… From media with super-high budgets such as La Tercera or El Mercurio, which have 10 journalists covering politics, to media where a single person is the medium. So, I think that is very good. But of course, the risk is that many times because of the laziness, you could miss important information. For example, I remember that, I think it was Alejandro Guillier’s chat (a presidential candidate’s WhatsApp group for journalists), there was a journalist whining; “Hey, but they’re not going to send us quotes [from the candidate]?” When you start to see it that way, there is a problem. [WhatsApp] is an aid, it facilitates the solution to the problem, but it is not the only way to do journalism. (Interview, December 2, 2017)

Many things can be extrapolated from this anecdote. Firstly, MIMs are erasing economic and material limitations between newsrooms. That is not to say that economic and material conditions do not matter at all anymore for the sources, since it is more likely that they will trust a well-know, popular, established medium. But if small journalistic projects make their way to a WhatsApp group, then the likelihood for them to obtain relevant pieces of information increases considerably.5 Moreover, these pieces of information do not limit themselves to text. Because MIMs support audio-visual material as well, journalists can now create a different array of content and take full advantage of the web as a platform. In the same way, entire interviews can be held over WhatsApp, which reduce the technological requirements that small newsrooms need to have in order to gather new information. More than once, a source with which I was texting told me to send them the questions over WhatsApp and they replied later with voice messages and pictures. It felt like having sources on-demand. That is, only using a smartphone and a decent Wi-Fi connection, I was able to collect text and audiovisual material to create a well-informed multimedia article for the web in less than an hour.

Journalists in the two newsrooms where I conducted participant observation seemed to take full advantage of the WhatsApp groups. These were usually created and regulated by the communications manager of an institution or politician. And thus, journalists were able to navigate between the Congress group, the Presidential Palace (La Moneda) group, and the Senate group. Because I conducted my fieldwork in times of the presidential campaign of 2017, each of the candidates had their own WhatsApp group full of journalists, where press releases, information about activities, pictures, and even the candidate’s voice recordings were shared with 200 journalists at a time. As expected, NGOs and political parties also had their own groups, although I heard many conversations where journalists complained about the irrelevant information shared on those. A very interesting phenomenon occurring within these groups was that community managers were not the only ones sharing information. Journalists took it upon themselves to warn others, even though they were from different media organizations, when something important was already happening or about to happen. A serious level of camaraderie permeated the entire conversation. If a journalist missed a quote, another one would post it in the group. “Everyone is going to have it anyway” (Interview, December 2, 2017), a journalist shrugged when I asked. This companionship, however, does not inherently come with the application. Rather, it is forged between journalists who spend hours and hours waiting together when a news conference or briefing gets postponed. Some of them studied at the same university, some of them used to work together, and some met in the eternal vigils of news reporting. Previous studies have shown how journalists converse and develop some camaraderie over other social networks such as Twitter (Mourão Citation2015; Molyneux Citation2015). However, even though the interviewed journalists would never call another media to ask for information they missed, or openly Twitted for help, asking on a WhatsApp group didn’t seem as an inappropriate behaviour.

“Everyone is going to have it anyway” is also a quote that reflects on the changes of temporality within the newsroom. During the “paper days” as Chilean journalists called the time period before the irruption of the web, if a news organization got an exclusive or a scoop in any particular story, other media wouldn’t be able to replicate that information until the next day. Now, however, the very meaning of a “scoop” in journalism is measure in the seconds it takes the next media to replicate that story in their website.6

Finally, the content editor’s quote seems to describe the dependency that some journalists are starting to have towards WhatsApp. He later added that:

Sometimes an excess of information is shared. For example, in these same groups like the Congress one, someone asks for a number and people fight to give you the number. Get it? So, it’s fun. But there are also times where people complain because these are numbers that you may have struggled to get, that the source gave to you [after gaining their trust] and then someone goes and shares it in a group with 250 people. (Interview, December 2, 2017)

The criticism inside the newsroom was often directed towards younger and more inexperienced journalists. Media workers would regularly complain that newer generations would never know how difficult it was to get a source’s phone number. Journalists’ contacts and agendas were considered a treasure, for these contained the most valuable raw material for journalism; their sources. Now, in a media environment that privileges and rewards immediacy, collaboration in all its forms might be the only way to survive the transformations in the temporalities of the media ecology.

WhatsApp is also beneficial for multiplatform media. The television station where I conducted my fieldwork also hosted a web site for news articles and a radio station. This means three separate teams of journalists working on information they could use in their respective platforms. However, WhatsApp is building bridges between the different groups. A web editor makes the case for the this:

I have a WhatsApp group with the TV political reporters, where they will warn you: “I already have the quote of such person,” “I am in the president’s press conference and she said this,” or they even send you the audio immediately. […] I am also in a group with the radio journalists, and in that chat the people of the radio will tell you what’s coming [on their broadcast]. (Interview, December 2, 2017)

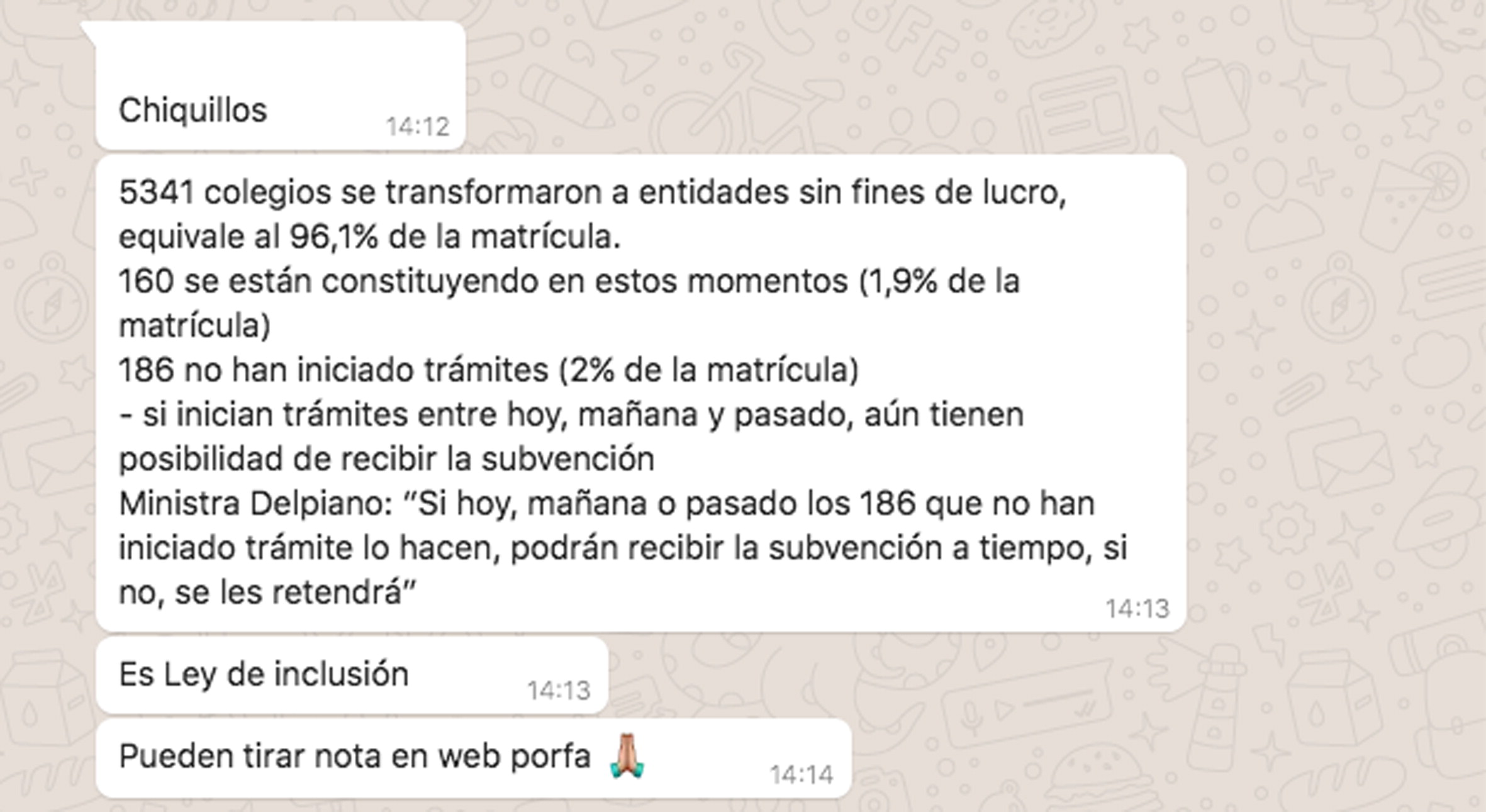

I saw the same behaviour multiple times. In Image 1 [in Spanish] we can see a newspaper journalist in the web journalists’ WhatsApp group sending information from the field and asking for someone to write a quick article of this data for the web.

Image 1. WhatsApp screenshot. April 4th, 2018.7,8

As Westlund (Citation2013) put it, “mobile devices have enhanced the possibilities for journalists to work and report from the field. They can be used for news reporting for mobile news platforms but also for the entire cross-media portfolio” (16), and as Image 1 shows, WhatsApp has indeed speed this process further along. However, as I mentioned above, WhatsApp groups can only host up to 250 journalists. This upper limit translates into an inclusion/exclusion process where the administrators of those groups needed to choose who remained and who was eliminated from those groups. I got eliminated from the internal groups as soon as I finished my field work in each newsroom. However, external groups’ administrators, such as the Congress or La Moneda groups, are constantly monitoring the comments of journalists from every media. If there is someone who commits serious ethical faults, or often sends spam messages, it would be very likely that the group administrator deletes them and adds someone else.

Technology: Choice and Coercion

This article has examined why journalists have chosen to turn to this MIM, what benefits they are obtaining from it, and what kind of impacts they are experiencing as a result of communicating through WhatsApp. I have said in this article that I sought to examine why journalists have chosen this MIM. The idea of choice in technology needs to be complicated here. I do not mean to start a techno-determinist debate at the end of this article. Rather, I simply wonder how free journalists really are to opt out of WhatsApp in an age where ever-present mobile communication is the norm. Some benefits of mobile phones and MIMs are easily observable. According to Ling and Donner (Citation2009), “mobile communication makes each of us directly addressable, regardless of where we may be,” (12), and only a few things can be more tempting for a journalist than always being able to reach a source, as I tested during my fieldwork. But the entrapments of technology should not be either forgotten or obviated. Hodder’s theory about the co-dependency between things and humans adds to a body of literature that sheds some light into the perils of the social adoption of technical innovations. As Herlihy-Mera (Citation2018) notes:

While the individual may have the ability to change devices or service providers, the structural role of e-experiences has become embedded into how people interact with one another and with the broader community, making the structural concerns that relate to culture of paramount importance. (144)

That is to say, journalists may choose today what phone model or telephone company they use, but whatever that choice is, WhatsApp need to be installed on there, for the structure of how news is reported is no longer up for choice and the audience’s new consumption routines dictates what tools should be use. Journalism has always been in a state of transition, for journalists have always been moving toward technological and digital innovations that make they work faster and more efficient. Journalists turned to WhatsApp because it seemed like the perfect tool to engage quickly and privately with their sources, and yet they did not anticipate the chain of consequences that followed.

As many applications before, WhatsApp might one day cease to exist, and it is yet to be seen how younger generations of journalists will carry their reporting when, as far as I see in this research, they have been trained in a “WhatsApp them first” context, where WhatsApp is a verb, and not a mere noun.

It is still too soon to tell the long-term consequences that WhatsApp has had on journalism and in the newsmaking process. But by affecting the temporality, that is to say, the rhythms and practices of news production, this MIM has already contributed to reshaping several aspects of newsgathering; intimacy and trust, camaraderie and obtainability are concepts with new meaning in today media ecology.

These observations should not be decontextualized from the history of journalism, at least in Chile. Journalists have entrapped themselves with technological objects since the very beginning of the profession as such. The changing nature of journalism, however, has establish traditional categories in every period of time under which new innovations are analyze and more often than not, criticize (De Maeyer and Le Cam Citation2015).

Conclusion

This study aimed to examine the incentives that motivated Chilean journalists’ decision to turn to WhatsApp and to shed some light onto the consequences that this mobile chat application has had on the newsmaking practices of Chilean reporters.

After spending seven months conducting participant observation, working as a journalist with other journalists, and interviewing reporters in a television station and in a newspaper, WhatsApp’s benefits and liabilities are discussed. In particular, this study observed the impact that WhatsApp has had in the intimacy between journalists and sources, the obtainability of information, and the reshaping in the temporalities of newsmaking. Overall, and despite the red flags that some of the literature is raising about the abusive use of this MIM, journalists seem likely to use this application on a regular basis.

This article drew on theoretical approaches that understand media as socio-technical organizations. That is, institutions based upon the relationship between nonhuman and human systems. The idea that humans not only depend on other humans, but they also create interdependencies with material things is particularly relevant to address the topic of this study. For contemporary journalists, WhatsApp offers the possibility to access faster and bigger amounts of information, but is also changing the way some journalists engage in the process of newsmaking and with their sources. Special attention should be placed on generational differences in these matters. Technologies such as MIM might be de-skilling older journalists and preventing newer generations from learning face-to-face tactics to gather information.

The transformations of the temporality within newsrooms are also studied and special attention is given to how WhatsApp is changing work rhythms. Because both journalists and sources seemed to be more willing to engage frequently over WhatsApp than any other communication platform, the time and monetary cost required to collect information has decreased considerably by using this application.

However, some negatives elements are also noted in this article. The ideas of privacy and intimacy are often conditioned by the informality that reigns over WhatsApp. In this context, journalists are confronted regularly with information that sways between being off and on the record. The virtual relationships in which journalists entangle themselves need to be addressed in order to prevent ethical lapses and lead to practices most closely related to the deontology of the profession.

The most worrying trend seems to be the inescapability that the journalists experience with this technology. MIMs in general and WhatsApp in particular have modified the state of affairs to a point where journalists depend heavily on these applications in order to do their job and face real consequences, both personal and professionally, if they detach themselves from it.

It should be noted that this study has been primarily concerned with newsrooms in democratic contexts where the use of WhatsApp is concerned with the facilitation of their everyday work and it does not involve life-threatening situations. In the same way, this analysis has concentrated on two Chilean newsrooms, selected for their size and influence over the country. Chile itself was chosen because of the immense penetration that mobile applications and the Internet in general has had over its citizens.

The findings of this study are restricted to WhatsApp. Further research should and must investigate the impact that platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat or other MIMs are having over journalists’ routines.

Notwithstanding its limitations, this study does suggest that journalism in Chile is turning towards a scenario where virtual relationships are privileged over face-to-face interactions. Moreover, the entanglement of humans and technologies, especially in journalism, should be thought from a critical perspective. We should wonder who is reaping the benefits from the heavy reliance that journalists and media workers are placing on technological innovations. The asymmetry in the balance of cost and benefits should warn us because, again, the longer and deeper the relationship between humans and technologies goes, the more difficult it is to detach from one another.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the reviewers and the editorial team for their detailed comments and suggestions toward improving this manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The fieldwork took place from August to November 2017 in Teletrece and from November to February 2018 in La Tercera. I worked full time in both newsrooms, sometimes changing shifts in order to observe better the routines of different media workers throughout the day.

2 Prior to my fieldwork there was no ethics committee at my current institution. Therefore, I weighed the ethical considerations carefully myself and I continue to do so today.

3 All the interviews and field notes have been translated from Spanish to English by the author.

4 In the same way, Hodges (2008) also argues that “human temporality, or temporalities if one considers its multiple dimensions, a symbolic process, is thus grounded in everyday social practices, and is the product of these practices, or what Munn also calls, in a phenomenological vein, ‘intersubjectivity’. It is simultaneously an inescapable dimension of these practices” (406).

5 Getting a spot in one of the WhatsApp group was not necessarily an easy endeavor. As in many other spheres of social life, acquaintanceship played a crucial role in this task. Journalists usually knew each other from physical encounters during press conferences and created a professional and social web that would later translate into the ability to help each other access physical and non-physical—such as WhatsApp groups—places.

6 The same does not happen with “exclusives”, where other media outlets, at least the ethical ones, would be required to quote the news organization that reported the information first and sometimes even create a hyperlink in their articles that takes the reader to the original piece.

7 Translation: “Guys (informal). 5341 schools are now non-for profit, which equals 96.1% of the total enrolment. 160 are being set up right now (1.9% of the total enrolment). 186 have not initiated the paper work (2% of the total enrolment).—If they initiate the paperwork between today, tomorrow and the day after, they still have a chance to receive the subsidies. Minister Delpiano (quote): ‘If today, tomorrow or the day after the 186 [schools] that have not yet started the paperwork do it, they could receive the subsidies in time, if not, they will not’. It’s the Inclusion Law. Could you upload the article to the web, please?”.

8 The article was later published on the web under the title “Ley de Inclusión: 186 establecimientos aún no inician proceso para ser sin fines de lucro” using the Minister’s quotes: http://www2.latercera.com/noticia/ley-inclusion-1-375-227-alumnos-estudian-gratis/

References

- Andueza, M. B., and R. Perez. 2014. “El móvil como herramienta para el perfil del nuevo periodista.” Historia y Comunicación Social 19: 591–602.

- Alexander, J. C., E. B. Breese, and M. Luengo, eds. 2016. The Crisis of Journalism Reconsidered. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Armstrong, P. 2018. “How to Run a Successful WhatsApp Group.” Forbes, April 29. https://www.forbes.com/sites/paularmstrongtech/2018/04/29/how-to-run-a-successful-whatsapp-group/.

- Belair-Gagnon, V., C. Agur, and N. Frisch. 2017. “The Changing Physical and Social Environment of Newsgathering: A Case Study of Foreign Correspondents Using Chat Apps During Unrest.” Social Media + Society 3 (1): 1–10.

- Belair-Gagnon, V., C. Agur, and N. Frisch. 2018. “Mobile Sourcing: A Case Study of Journalistic Norms and Usage of Chat Apps.” Mobile Media & Communication 6 (1): 53–70.

- Boczkowski, P. J. 2005. Digitizing the News: Innovation in Online Newspapers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Boczkowski, P. J., M. Matassi, and E. Mitchelstein. 2018. “How Young Users Deal With Multiple Platforms: The Role of Meaning-Making in Social Media Repertoires.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 23 (5): 245–259.

- Bouhnik, D., and M. Deshen. 2014. “WhatsApp Goes to School: Mobile Instant Messaging Between Teachers and Students.” Journal of Information Technology Education: Research 13 (1): 217–231.

- Butler Breese, E. 2016. “The Perpetual Crisis of Journalism: Cable and Digital Revolutions.” In The Crisis of Journalism Reconsidered, edited by J. C. Alexander, E. B. Breese, and M. Luengo. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Chambers, D. 2017. “Networked Intimacy: Algorithmic Friendship and Scalable Sociality.” European Journal of Communication 32 (1): 26–36.

- Church, K., and R. de Oliveira. 2013. “What’s Up with Whatsapp? Comparing Mobile Instant Messaging Behaviors with Traditional SMS.” In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, 352–361. ACM.

- Clayman, S. E. 1993. “Reformulating the Question: A Device for Answering/Not Answering Questions in News Interviews and Press Conferences.” Text-Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse 13 (2): 159–188.

- Cottle, S., and M. Ashton. 1999. “From BBC Newsroom to BBC Newscenter: On Changing Technology and Journalist Practices.” Convergence 5 (3): 22–43.

- Craig, I. 2017. “Closing Access to the Back Door: Investigative Journalists Working in Hostile Environments Need Encrypted Apps to Work More Safely. This is Being Forgotten in the Current Debate on Encryption.” Index on Censorship 46 (3): 60–62.

- De Maeyer, J., and F. Le Cam. 2015. “The Material Traces of Journalism: A Socio-Historical Approach to Online Journalism.” Digital Journalism 3 (1): 85–100.

- Domingo, D., P. Masip, and I. Costera Meijer. 2015. “Tracing Digital News Networks: Towards an Integrated Framework of the Dynamics of News Production, Circulation and Use.” Digital Journalism 3 (1): 53–67.

- Elliott, D., and C. Culver. 1992. “Defining and Analyzing Journalistic Deception.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 7 (2): 69–84.

- Endeley, R. E. 2018. “End-to-End Encryption in Messaging Services and National Security—Case of WhatsApp Messenger.” Journal of Information Security 9: 95–99.

- Erdal, I. J. 2007. “Researching Media Convergence and Crossmedia News Production.” Nordicom Review 28 (2): 51–61.

- Faye, A. D., S. Gawande, R. Tadke, V. C. Kirpekar, and S. H. Bhave. 2016. “WhatsApp Addiction and Borderline Personality Disorder: A New Therapeutic Challenge.” Indian Journal of Psychiatry 58 (2): 235–237.

- Frère, M. S. 2017. “‘I Wish I Could Be the Journalist I Was, But I Currently Cannot’: Experiencing the Impossibility of Journalism in Burundi.” Media, War & Conflict 10 (1): 3–24.

- Gallo, Jason. 2004. “Weblog Journalism: between infiltration and integration.” In Into the Blogosphere: Rhetoric, Community, and Culture of Weblogs, edited by Minnesota Blog Collective. http://blog.lib.umn.edu/blogosphere/weblog_journalism.html (accessed 17 December 2018).

- Gans, H. 1979. Deciding What’s News. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Gibbs, J. L., N. B. Ellison, and R. D. Heino. 2006. “Self-Presentation in Online Personals: The Role of Anticipated Future Interaction, Self-Disclosure, and Perceived Success in Internet Dating.” Communication Research 33 (2): 152–177.

- Gieber, W. 1964. “News Is What Newspapermen Make It.” In White, People, Society and Mass Communication, edited by L. A. Dexter and D. Manning. New York: Free Press.

- Gynnild, A. 2014. “Journalism Innovation Leads to Innovation Journalism: The Impact of Computational Exploration on Changing Mindsets.” Journalism 15 (6): 713–730.

- Hanitzsch, T., M. Anikina, R. Berganza, I. Cangoz, M. Coman, B. Hamada, F. Hanusch, et al. 2010. “Modeling Perceived Influences on Journalism: Evidence from a Cross-National Survey of Journalists.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 87 (1): 5–22.

- Hannerz, U. 2012. Foreign News: Exploring the World of Foreign Correspondents. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Herlihy-Mera, J. 2018. After American Studies: Rethinking the Legacies of Transnational Exceptionalism. New York: Routledge.

- Hodder, I. 2011. “Human‐Thing Entanglement: Towards an Integrated Archaeological Perspective.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 17 (1): 154–177.

- Hodder, I. 2014. “The Entanglements of Humans and Things: A Long-Term View.” New Literary History 45 (1): 19–36.

- Hodges, M. 2008. “Rethinking Time’s Arrow: Bergson, Deleuze and the Anthropology of Time.” Anthropological Theory 8 (4): 399–429.

- Jiang, L. C., N. N. Bazarova, and J. T. Hancock. 2011. “The Disclosure–Intimacy Link in Computer-Mediated Communication: An Attributional Extension of the Hyperpersonal Model.” Human Communication Research 37 (1): 58–77.

- Kaye, L. K., S. A. Malone, and H. J. Wall. 2017. “Emojis: Insights, Affordances, and Possibilities for Psychological Science.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21 (2): 66–68.

- Kemp, S. 2018. Global Digital Report. We Are Social. https://wearesocial.com/blog/2018/01/global-digital-report-2018.

- Kjeldskov, J., M. Gibbs, F. Vetere, S. Howard, S. Pedell, K. Mecoles, and M. Bunyan. 2004. “Using Cultural Probes to Explore Mediated Intimacy.” Australasian Journal of Information Systems 11 (2): 102–115.

- Klinenberg, E. 2005. “Convergence: News Production in a Digital Age.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 597 (1): 48–64.

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Clarendon Lectures in Management Studies). New York: Oxford.

- Lemann, N. 2013. “Does Journalism Have a Future?” The Times Literary Supplement. https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/public/does-journalism-have-a-future/.

- Ling, R., and Donner, J. (2009). Mobile Phones and Mobile Communication. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Livingston, S., and W. L. Bennett. 2003. “Gatekeeping, Indexing, and Live-Event News: Is Technology Altering the Construction of News?” Political Communication 20 (4): 363–380.

- Loosen, W. 2015. “The Notion of the ‘Blurring Boundaries’ Journalism as a (de-) differentiated phenomenon.” Digital Journalism 3 (1): 68–84.

- Malka, V., Y. Ariel, and R. Avidar. 2015. “Fighting, Worrying and Sharing: Operation ‘Protective Edge’ as the First WhatsApp War.” Media, War & Conflict 8 (3): 329–344.

- McNair, B. 2006. Journalism, News and Power in a Globalised World. New York: Routledge.

- Mitchelstein, E., and P. Boczkowski. 2009. “Between Tradition and Change: A Review of Recent Research on Online News Production.” Journalism 10 (5): 562–586.

- Munn, N. D. 1992. “The Cultural Anthropology of Time: A Critical Essay.” Annual Review of Anthropology 21 (1): 93–123.

- Molyneux, L. 2015. “What Journalists Retweet: Opinion, Humor, and Brand Development on Twitter.” Journalism 16 (7): 920–935.

- Mourão, R. R. 2015. “The Boys on the Timeline: Political Journalists’ Use of Twitter for Building Interpretive Communities.” Journalism 16 (8): 1107–1123.

- Negreira-Rey, M. C., X. López-García, and L. Lozano-Aguiar. 2017. “Instant Messaging Networks as a New Channel to Spread the News: Use of WhatsApp and Telegram in the Spanish Online Media of Proximity.” In World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, 64–72. Cham: Springer.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, D. A. L. Levy, and R. Kleis Nielsen. 2018. Reuters Institute Digital News Report. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Oxford: University of Oxford.

- Newton, K. 1999. “Mass Media Effects: Mobilization or Media Malaise?” British Journal of Political Science 29 (4): 577–599.

- Nielsen, K. R., and S. A. Ganter. 2018. “Dealing with Digital Intermediaries: A Case Study of the Relations Between Publishers and Platforms.” New Media & Society 20 (4): 1600–1617.

- Patterson, T. E. 2013. Informing the News. New York: Vintage.

- Peterson, M. A. 2003. Anthropology and Mass Communication: Media and Myth in the New Millennium. Vol. 2. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Primo, A., and G. Zago. 2015. “Who and What Do Journalism? An Actor-Network Perspective.” Digital Journalism 3 (1): 38–52.

- Rajini, S., K. Kannan, and P. Alli. 2018. “Study on Prevalence of Whatsapp Addiction among Medical Students in a Private Medical College, Pondicherry.” Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development 9 (7): 113–116.

- Reich, Z. 2006. “The Process Model of News Initiative: Sources Lead First, Reporters Thereafter.” Journalism Studies 7 (4): 497–514.

- Reich, Z. 2008. “The Roles of Communication Technology in Obtaining News: Staying Close to Distant Sources.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 85 (3): 625–646.

- Sedano, J., and M. B. Palomo. 2018. “Aproximación metodológica al impacto de WhatsApp y Telegram en las redacciones.” Hipertext. net: Revista Académica sobre Documentación Digital y Comunicación Interactiva 16: 61–67.

- Shoemaker, P. J. 1989. “Public Relations Versus Journalism: Comments on Turow.” American Behavioral Scientist 33 (2): 213–215.

- Singer, J. B. 2005. “The Political j-Blogger: ‘Normalizing’ a New Media Form to Fit Old Norms and Practices.” Journalism 6 (2): 173–198.

- Schudson, M. 1989. “The Sociology of News Production.” Media, Culture & Society 11 (3): 263–282.

- Souza Leal, B., E. Antunes, and P. B. Vaz. 2013. Narratives of Death: Journalism and Figurations of Social Memory, 106–118. Braga: CECS-Publicações/eBooks.

- Thorsen, E., and D. Jackson. 2018. “Seven Characteristics Defining Online News Formats: Towards a Typology of Online News and Live Blogs.” Digital Journalism 6 (7): 847–868.

- Tidwell, L. C., and J. B. Walther. 2002. “Computer‐Mediated Communication Effects on Disclosure, Impressions, and Interpersonal Evaluations: Getting to Know One Another a Bit at a Time.” Human Communication Research 28 (3): 317–348.

- Trist, E. L. 1981. The Evolution of Socio-Technical Systems: A Conceptual Framework and an Action Research Program. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Labour, Ontario Quality of Working Life Centre.

- Tuchman, G. 1978. Making News. New York: Free Press.

- Turkle S. 2011. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books.

- Usher, N. 2014. Making News at The New York Times. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Van den Eijnden, R. J., J. S. Lemmens, and P. M. Valkenburg. (2016). “The Social Media Disorder Scale.” Computers in Human Behavior 61: 478–487.

- Walters, L. M., and T. N. Walters. 1992. “Environment of Confidence: Daily Newspaper Use of Press Releases.” Public Relations Review 18 (1): 31–46.

- Walther, J. B. 1996. “Computer-Mediated Communication: Impersonal, Interpersonal, and Hyperpersonal Interaction.” Communication Research 23 (1): 3–43.

- Waters, S. 2017. “The Effects of Mass Surveillance on Journalists’ Relations with Confidential Sources: A Constant Comparative Study.” Digital Journalism 6 (10): 1294–1313.

- Westlund, O. 2013. “Mobile News: A Review and Model of Journalism in an Age of Mobile Media.” Digital Journalism 1 (1): 6–26.

- Willnat, L., and D. H. Weaver. 2018. “Social Media and US Journalists: Uses and Perceived Effects on Perceived Norms and Values.” Digital Journalism 6 (7): 889–909.