Abstract

Recent reports show that users increasingly use smartphone messenger applications such as WhatsApp for news. Media outlets have started to provide news via WhatsApp in addition to other platforms. In journalism scholarship, the routines of messenger app journalism are still little understood. Building on the Diffusions of Innovations theory, this paper explores whether newsrooms treat WhatsApp similar to other social media, which they have used for a longer period of time, or whether they have developed new practices that respect WhatsApp’s roots in mobile and interpersonal communication. Focusing on Germany as a case study and drawing on an analysis of 3745 messages sent to WhatsApp channels of news outlets and on an online survey of journalists working with social media (N = 111), this study shows that journalists utilize the innovative possibilities of WhatsApp for news to a varying degree. While some characteristics of mobile communication are considered in news outlets’ strategies, engagement with the audience is often neglected. The results highlight the challenges for relational innovations in the editorial process.

Introduction

WhatsApp is the most used messaging app for news, and numbers are already higher than for other social networks such as Instagram and Twitter (Newman et al. Citation2018, 52). While there is a decline in Facebook use for news and a stagnation in general Facebook use, WhatsApp use increases for both categories. WhatsApp use for news has almost tripled since 2014 and has overtaken Twitter’s importance in many countries (Newman et al. Citation2018, 12). Reuters Digital News Report found that half of the sample of online users in Malaysia and Brazil use WhatsApp for news and around a third in Spain and Turkey (Newman et al. Citation2018, 9). With growing userbases, WhatsApp news channels become relevant for journalism studies. Purposes of WhatsApp that have gained scholarly attention are the communication between journalists and sources (Belair-Gagnon, Agur, and Frisch Citation2016; Dodds Citation2019; McIntyre and Sobel Citation2019), and the communication within groups, e.g., journalists discussing their work (Baroni and Mayr Citation2018) or members of the audience talking about news (Swart, Peters, and Broersma Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Villi and Noguera-Vivo Citation2017; Goh et al. Citation2017). Our aim is to study how journalists use WhatsApp for news as a journalistic channel, i.e., as a tool for the communication between journalists and their audience.

Previous studies on WhatApp as a journalistic tool highlight two functions which are based on the characteristics of WhatsApp’s genuine purpose: mobile and interpersonal communication. A study on local news and their digital transition using interviews of European journalists and editors shows that news outlets have started to provide news via WhatsApp in addition to other platforms to compensate for the declining Facebook usage and especially to reach younger audiences (Jenkins and Nielsen 2018). This shows that there is a potential technological change for journalism. Angeluci, Scolari, and Donato (Citation2017) follow WhatsApp’s origin in interpersonal communication and describe how journalists use WhatsApp for engagement, which might be a relational change for journalism.

In this paper, we analyze and compare the innovativeness of both (or: the two fundamental) functions of WhatsApp, i.e., mobile and interpersonal communication, as a journalistic tool. In this regard, we consider both technological and relational aspects. We focus on WhatsApp for news as a distribution and an engagement channel. We define a distribution channel as a WhatsApp channel (also called broadcast list or newsletter) used by media outlets to share content with their audience. We define an engagement channel as a WhatsApp channel used by media outlets to engage with their audiences, which could include getting feedback, sourcing, and building a loyal user base by personal communication. Media outlets can use WhatsApp channels for one function only or for both. We are interested in studying to what extent journalists utilize WhatsApp’s technological affordances and how different forms of engagement with audiences are viewed and are borne out in practice.

Journalists’ adaption to innovations

Diffusion theory and social media

Innovation diffusion theory analyzes how an innovation is adapted within a social system (Rogers Citation2003). Rogers identifies several aspects that influence the diffusion and divides the process in phases. He describes the process of adoption as an S-curve and plots the cumulative number of adopters as well as the five categories of adopters (i.e., innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards). This approach has been very influential: Innovation diffusion theory has been used to describe how media innovations are adopted by users, for example, TV (Larsen Citation1962), the Internet (Zhu and He Citation2002), and mobile communication tools (Leung and Wei Citation1999). Criticism of innovation theory attributes its success to an uncomplicated theoretical base in the emerging communication science and describes it as over simplistic and too generalizing (Dearing and Singhal Citation2006; Karnowski, von Pape, and Wirth 2011). However, innovation diffusion theory has been very beneficial to comprehend innovation as a process and analyze the characteristics of its different stages. In addition to the individual level, the theory has been successful at identifying the innovation diffusion in organizations. It has shown to reveal different stages and degrees of embracing a new technology. Consequently, communication scholars apply innovation diffusion theory to newsrooms: Garrison (Citation2001) investigates how journalists use the Internet for reporting. Singer (Citation2004) examines newsrooms convergence. More recently, the framework has also been used to understand how newsrooms work with social media: Von Nordheim, Boczek, and Koppers (Citation2018) show that journalists’ use of social media as sources can be categorized into different phases of adaption. Ekdale et al. (Citation2015) analyze the change process of a media company, including the use of social media in the newsroom. They identify three aspects of newsroom innovation: technological, relational, and cultural innovation. Examples for technological innovations are multimedia storytelling, a digital-first publishing strategy, or the use of social media tools. They define relational innovation as changes related to audience relationships; which in practice could mean providing opportunities for the audience to influence coverage decisions. Cultural innovation includes the perceptions about the nature and goals of journalism. Ekdale et al. (Citation2015) find that in a newsroom undergoing change, technological innovation is faster than relational and cultural innovation, and observe that “questions about relational change showed considerable skepticism that new ways offered a relative advantage to old ones” (Ekdale et al. Citation2015, 948). Studying WhatsApp for news through the framework of innovation diffusion theory we examine whether technological innovation is preceding relational innovation. Cultural aspects are not considered.

As Paulussen (Citation2016) shows, journalism scholars have used alternative perspectives for the analysis of newsroom innovation. However, these studies also describe how innovation faces hindrances, especially relational innovation. Since analyses of WhatsApp for news are still scarce, we discuss the journalism research that focuses on the adaption of Twitter as a well-studied example for change. Lasorsa, Lewis, and Holton (Citation2012) find that journalists using Twitter adapt it to existing norms and that practices with old habits and conventional role perceptions stay in place. If these results are transferred to WhatsApp, we might speculate that WhatsApp is used similar to other social media. Thus it is necessary to investigate the characteristics of WhatsApp channels, especially those characteristics which would indicate an adaptation of new practices.

As Hermida (Citation2013) describes, studies investigating relational change found that journalists’ relationship with the audience has changed only gradually. As work of Cozma and Chen (Citation2013) and Noguera-Vivo (2013) shows, only few journalists use Twitter to collaborate with their audience on the production of news. Journalists largely view Twitter users as “active recipients” (Hermida et al. Citation2011), i.e., observers, idea generators, and sources at the start of the journalistic process, and commentators of the content published by journalists. Broersma and Graham (Citation2013) show that in about 20% of the stories with tweets the tweet had triggered the news story, highlighting that Twitter “broadens the entrance to the news and makes news coverage more diverse” (Broersma and Graham Citation2013, 461). For this WhatsApp study, we build on these studies and track traces of collaboration and other engagement of the audience.

In sum, from Rogers’ diffusion perspective, how newsrooms adapt social media is an example of a slow evolution with one few journalists being innovators as has been discussed above with regard to Twitter. However, there are multifaceted reasons for this. For example, Usher (Citation2014) points out how management strategies do not translate to the editors. We take the approach that cautious social media innovation has vises and virtues: With the “dislocation of news journalism” (Ekström and Westlund Citation2019) the power of social media platforms has become apparent. While using social media to successfully engage the audience might be a fruitful strategy for some media outlets, others might stay away to keep overall traffic or at least engagement at their proprietary platform. The purpose of this study is to assess the approaches of newsrooms.

Journalism and WhatsApp: distribution and engagement

WhatsApp as a mobile communication tool and its relevance for journalism

WhatsApp is a smartphone application that is originally intended only for interpersonal communication. It has a browser version for desktop computers but it was designed for use on mobile devices and is most frequently used on smartphones making it an inherently mobile communication tool. Because smartphones are ubiquitous and WhatsApp is a widely used application WhatsApp has become a relevant channel for digital journalism. To date, research has yet to define the exact characteristics of mobile devices for digital journalism production and consumption (Westlund and Quinn 2018) but the analysis of “locative media” is important, for example, the question whether “journalistic content is created uniquely by and for mobile devices” (Erdal et al. Citation2019). WhatsApp can be a tool for production and consumption of news: For journalists, WhatsApp is not only an application to reach sources but also to reach their audiences. In this paper, we set out to explore how newsrooms adapt to accommodate this new news mobility. We analyze WhatsApp channels, which are an off-label use by media outlets and combine the interpersonal communication function of WhatsApp with the distribution of content via a mobile app. We study the mobile news content of the channels and possible interactions between journalists and their audience.

So far, analyses of WhatsApp as a journalistic tool are scarce. Previous studies on WhatsApp and journalism mostly focus on WhatsApp as a tool to communicate. Several studies discuss WhatsApp from an audience perspective, analyzing how users use smartphone messenger applications for news (Newman et al. Citation2018; Swart, Peters, and Broersma Citation2017) and share and discuss news within a group of friends or colleagues (Swart, Peters, and Broersma Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Villi and Noguera-Vivo Citation2017; Goh et al. Citation2017). The Reuters Digital News Report describes how the dynamic that users rely less on Facebook and more on WhatsApp for news is driven by brand images: WhatsApp is associated with “best friend, fun, brings people together” (Newman et al. Citation2018, 13). Research mentioning WhatsApp as a communication tool for journalists focuses on the function of the messenger within the system of production of content, for example, journalists using the app to communicate among a network of reporters (Baroni and Mayr Citation2018) or with sources (Agur Citation2019; Dodds Citation2019; McIntyre and Sobel Citation2019; Belair-Gagnon, Agur, and Frisch Citation2016).

WhatsApp channels for the distribution of mobile news

Media outlets use WhatsApp to share their content (also called “newsletter”) with their audiences. Their audiences may have migrated from Facebook or Twitter and use WhatsApp to discuss and share news with friends. Another reason to set up a WhatsApp channel may be that media outlets want to reach younger audiences (Jenkins and Nielsen 2018). The proportion of users using smartphones for news is increasing: 62% of the Reuters Digital News Report sample across all 36 countries (case study country Germany: 47%) say they used their smartphones for news in the last week (Newman et al. Citation2018, 28).

Content shared in distribution channels is subject to the specifics of journalism via mobile communication. Previous research on mobile communication usage practices provides perspectives on how to analyze content distributed on WhatsApp channels. We will focus on two perspectives: ubiquity and news snacking.

One characteristic of mobile communication is the ubiquity of use. A study relying on the diary method found that people tended to squeeze mobile news consumption into otherwise unoccupied spaces in their day, referred to as “interstices” (Dimmick, Feaster, and Hoplamazian 2011). In addition to using mobile news in gaps, mobile phones and, to some extent, news have diffused throughout daily life and have become intertwined with other activities (Struckmann and Karnowski Citation2016; Westlund Citation2015; Wolf and Schnauber Citation2015). For WhatsApp distribution channels, these studies suggest that news outlets may adapt to these new patterns of ubiquitous use by posting content throughout the day.

WhatsApp’s affordances to users may make the mobile news use practice of “snacking” more frequent, which Costera Meijer and Groot Kormelink define as “grabbing ‘bits and pieces of information in a relaxed, easy-going fashion to gain a sense of what is going on’” (2015, 670). Van Damme et al. (Citation2015) show that mobile news use is characterized by frequent, brief checks to see what is new. Molyneux’s (Citation2018) results reveal that news sessions on smartphones are shorter than on other platforms. Furthermore, he links the concept of snacking to a lower quality of the content and to less knowledge on issues important for civic engagement. These results suggest analyzing WhatsApp content for their type (length and structure) and topics. Research on news websites shows that journalists and their audiences are divided between a “news gap” with journalists having a higher preference for public-affairs news (stories about politics, economics, and international matters) and their audiences favoring non-public-affairs news, e.g., crime, entertainment, sports (Boczkowksi and Mitchelstein Citation2013, 6). This gap might be relatively smaller for WhatsApp news channels.

WhatsApp channels for audience engagement

The engagement function of WhatsApp channels has been explored in newsrooms in Brazil, where WhatsApp use for news is among the highest in the world. Angeluci, Scolari, and Donato (Citation2017) found that journalists use WhatsApp channels to gain information from their audiences, for example, text, audio, and images in breaking news situations. In contrast to social media the information is exclusive to one media outlet. Furthermore, journalists use WhatsApp to make users feel closer to the newsroom, for example, by mentioning their messages in their content. A study of Rwandan journalists (McIntyre and Sobel Citation2019), which combines the analysis of production, distribution, and feedback via WhatsApp, shows how WhatsApp facilitates rich interactions with audience members and makes the news process more accessible to the public. Kligler-Vilenchik and Tenenboim (forthcoming) describe how an Israeli journalist uses WhatsApp to include his audience in several steps across the news-production process.

The present study shows that media outlets can use a WhatsApp channel for sourcing and discussions with their audience. Thus, audience engagement is an interesting perspective for research on WhatsApp for news. The term is used in varying ways and connected to concepts of participation and citizen journalism as well as more data-driven approaches such as audience metrics (Meier, Kraus, and Michaeler Citation2018; Lawrence, Radcliffe, and Schmidt Citation2018; Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc 2018; Cherubini and Nielsen 2016). Loosen (Citation2016) differentiates between three different ways of how journalists integrate the audience in the editorial process: as an economically motivated strategy to build audience loyalty (editorial analytics), as a chance to enrich diversity in public discourse (participation) and – becoming apparent more recently – as a challenge originating from hate speech, propaganda, and other unwanted content posted online. Quandt (Citation2018) describes this kind of user engagement with the concept of “dark participation”. However, the third perspective plays a minor role for WhatsApp. In contrast to other social media, subscribers’ messages to WhatsApp channels are not visible to other subscribers but only to the social media editors managing the WhatsApp channels.

Audience engagement is not a traditional pillar of journalism. Many journalists have limited skills and experience with it (Meier, Kraus, and Michaeler Citation2018; Loosen Citation2016). When integrating social media into the editorial process, although different variables significantly influence how journalists use it (Gulyas Citation2013), overall, traditional routines hinder the transformation of the relationship with the audience. Emerging after a phase of optimism, the research identifying reluctance in audience engagement has been described as “participatory disillusionment” (Lawrence, Radcliffe, and Schmidt Citation2018). Recent studies on audience engagement have underlined the challenges for journalists wanting to engage. Lawrence, Radcliffe, and Schmidt (Citation2018) identify that technology, economics, and organizational culture shape audience engagement. Meier, Kraus, and Michaeler emphasize that embracing all perspectives of audience engagement constitutes it a “paradigm change” (2018, 9) for journalism. These results suggest that for WhatsApp channels, audience engagement might be used only to a small extent.

Research questions

Our literature review leads us to the following research questions relating to how WhatsApp for news might be developing as a new practice of journalists. Based on Ekdale et al. (Citation2015) we analyze aspects of technological change (RQ1.1 and RQ1.2: WhatsApp used for distribution) and relational change (RQ2.1 and RQ2.2: WhatsApp used for audience engagement) separately to understand whether innovation in one area might have diffused more deeply.

RQ 1.1: To what degree are the topics posted on WhatsApp distribution channels different from news outlets’ social media channels on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram?

Previous results suggest that at the beginning of the diffusion of the innovation, journalists would treat WhatsApp for news similar to existing practices, i.e., they would send similar messages as via social media channels that they have used for a longer period of time. We explore the status of independence by exploring the number of crossposts, i.e., content posted on WhatsApp and on other social media.

RQ1.2: To what degree do journalists consider WhatsApp’s special characteristics as a mobile communication app (news snacking, ubiquity)?

RQ 1.2a: To what degree do journalists select non-public-affairs topics for WhatsApp and edit the content to short texts with media attachments (adaptions to news snacking practices)?

Since mobile news consumption is associated with news snacking (Molyneux 2018), we analyze whether news outlets have adapted by distributing short posts and predominantly non-public-affairs news. Furthermore, we explore whether the use of media attachments and links compensates for shorter messages.

RQ 1.2b: At what frequency and time of day are messages posted to WhatsApp distribution channels (ubiquity)?

We analyze the metrics of WhatsApp for news.

As a second element of the study we analyze whether the WhatsApp practices that journalists use show aspects of relational change.

We focus on WhatsApp’s specific advantage, namely that it can be used as a participation and audience engagement channel, due to its origin as a messenger app for interpersonal communication. Via WhatsApp journalists can easily get in touch with their users because all users are accustomed to use WhatsApp for interpersonal communication. They can ask for comments, questions, feedback, and media attachments making WhatsApp a potentially powerful inbox for letters to the editor, a polling, and a crowdsourcing tool. We ask:

RQ 2.1: How do journalists engage with their audience in messages sent to WhatsApp distribution channels?

We explore all requests for audience engagement by the journalists, for example, requests for feedback, crowdsourcing, opinions, as well as small talk, for example, asking the audience if they have plans for the weekend.

RQ 2.2: What do journalists say about the use of WhatsApp, especially how they interact with their audiences?

We draw on a survey of journalists working with social media to explore their audience engagement practices.

Methods

Data collection and case study structure

Germany is the largest state in the European Union and has a diverse media landscape including private and public service media outlets. German users are known for rather hesitant change in media habits, for example, social media is less commonly used for news (GER: 31%, the USA: 45%, Brazil: 66%, Newman et al. Citation2018, 11). However, the proportion of users using WhatsApp for news is 14% and thereby close to the international average of 16% (Newman et al. Citation2018, 52). The large range between countries (Brazil: 48%, the USA 4%, Newman et al. Citation2018, 12 and 52) makes Germany a sensible case study to gain knowledge about the overall trends regarding WhatsApp for news. German local news editors have already been interviewed about which digital transitions they use and have named WhatsApp newsletters as one example (Jenkins and Nielsen 2018).

To analyze all media types we conducted a case study of all newsrooms based on Germany’s largest state North Rhine-Westphalia (population: 17 million). The state contains 4 of Germany’s 10 largest cities, as well as rural areas, resulting in a diverse media landscape with 78 newsrooms of small regional newspapers as well as tabloid and national press, private and public service broadcasting. We included all independent newspapers (Zeitungsmap Citation2018), all general interest private radio stations (Die Medienanstalten ALM GbR 2017; Radio NRW GmbH Citation2018), and the regional studios as well as the central newsroom of the public service broadcaster (WDR). For every newsroom, we assessed whether it had a WhatsApp channel. In April 2018, half of the newsrooms in North Rhine-Westphalia used WhatsApp channels (39 out of 78). Sixteen out of 78 newsrooms had a WhatsApp distribution channel, which we subscribed to (see ). However, two news outlets (Aachener Nachrichten, Aachener Zeitung) sent out the exact same messages and hence only messages from Aachener Nachrichten were kept in the data set. Additionally, according to their websites, 23 out of 78 newsrooms in North Rhine-Westphalia had a WhatsApp number to receive user messages but did not use it as a channel distributing news (engagement only channels).

Table 1. Overview of the WhatsApp distribution channels of German media outlets in North Rhine-Westphalia that were analyzed.

To answer our research questions on distribution (RQ 1.1 and RQ 1.2), we analyzed the messages posted by the news outlets (in-depth plus computational methods content analysis). To answer our research questions on audience engagement (RQ 2.1 and RQ 2.2), we used the in-depth content analysis and conducted a survey among journalists.

Content analysis: in-depth human coding and computational methods approach

We examined all WhatsApp posts published in four consecutive months in 2018 (data set CM (computational methods), complete weeks from Monday, 9th April until Sunday, 12th August, NCM = 3745 messages). All WhatsApp messages posted in the second week of the time frame investigated were used for a human-coded in-depth analysis (data set HC (human coded), complete week from Monday, 16th April until Sunday, 22th April, NHC = 220 messages). Data were collected using the WhatsApp iPhone app and exported via the app function as text data. Photo captions and text messages that included photos had to be added manually because their export is not supported by the app. The data were analyzed using R (R Core Team Citation2018; Koppers et al. Citation2019).

Independence from other social media (RQ1.1) was operationalized by checking for crosspostings: Every topic of a message in data set HC was searched for in the texts and photos on the Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram pages of the media outlets. Relevant for a topic being labeled as a crosspost was the content and not the wording of the messages. We used topics of a message and not whole messages as units because several media outlets combined several topics into one WhatsApp message covering several issues, thus using it as a newsletter.

To determine whether WhatsApp content was selected and edited for news snacking (RQ1.2a) we analyzed the use of media attachments (photos, audios, videos) and links (data set CM) and studied the topics of the messages (human coding of every message in data set HC). The topics were coded using an extended version of Moon and Hadley’s coding instructions developed for news on Twitter (2014, 296), which are suitable for the short texts per topic sent to WhatsApp channels. Moon and Hadley’s definition originally contains 11 topics (politics, international affairs, economy, crime, disaster, weather, arts, sports, entertainment, life style, and science). We added three topics, which were defined after coding pretest data (transportation, prize competitions, and events calendars). Intercoder reliability between two coders was calculated using a 15% random sample of the messages resulting in a value of Krippendorff’s alpha of 0.883.

The ubiquity of WhatsApp news (RQ 1.2 b) was analyzed by identifying the average metrics of WhatsApp posts (frequency and time of day of messages, data set CM).

Whether journalists use WhatApp as an interpersonal communication app and engage with their users (RQ 2.1) was determined by coding every message in dataset HC for eight types of audience engagement requests (feedback, crowdsourcing, opinion, song request, and voice messages, prize competitions, small talk, other, none). The categories were defined after coding pretest data. Intercoder reliability between the two coders was calculated using a 15% random sample of the messages resulting in a value of Krippendorff’s alpha of 1.0.

Survey: Asking journalists about WhatsApp for news

In contrast to other social media, audience engagement in WhatsApp channels is not directly visible for other users. Thus, in addition to analyzing the content for audience engagement, we conducted a survey asking journalists working with WhatsApp about their practices (RQ 2.2). The survey was online from 29th June to 18th August and respondents were recruited mainly by requests via e-mail and social media. The data set (S) contains the answers of 111 completed surveys; 56 of the surveys were completed by female respondents, the mean age was 39.19 (median = 38.0, SD = 12.3) and 62 respondents worked in North Rhine-Westphalia. The high response rate among journalists from the state is probably due to their level of familiarity with the research institution, which is also located in the state.

The survey was aimed at journalists working with social media and asked questions about their use of social media as a distribution and engagement tool in the newsrooms they were working in. We inquired which social media they used, when and how they used them and we additionally asked about the reactions from their audiences to their social media activities.

All respondents stated that the newsrooms they work at use social media to distribute their content. Fifty percent use WhatsApp as a newsletter or engagement channel.

Results: characteristics of news outlets’ use of WhatsApp for news

Distribution: independence of WhatsApp from other social media (RQ1.1)

Among the newsrooms distributing news via WhatsApp, all use WhatsApp channels in addition to and depended on their other social media channels. The share of crossposts varies considerably between the news outlets and can be up to 100% (see ). Nevertheless, on average 25% of the topics are exclusively distributed via WhatsApp. Four out of 15 newsrooms have an exclusive ratio higher than 40%. Further evidence of new practices evolving can be seen analyzing an example message: On 19th April Mindener Tageblatt sends a WhatsApp message including an events calendar, things to do on the weekend, and news about the beginning of a trial involving drug abuse of a local sports hero. This WhatsApp exclusive message represents service orientation (events calendar, see results for RQ 1.2a on news snacking) and the avoidance of having to moderate comments of a topic that might spark controversy (trial), which would be necessary on other social media.

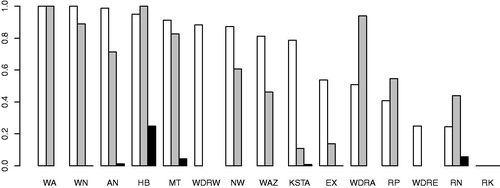

Figure 1. Share of topics in the messages of the human-coded dataset of WhatsApp distribution channels of German media outlets in North Rhine-Westphalia, which are crossposts, i.e., topics also posted to the Facebook (white), Twitter (gray), and Instagram (black) channels of the media outlet. Media outlets are sorted according to the share of crossposts with Facebook.

The content analysis of all topics in 220 messages (212 with text content) in the human-coded dataset shows that on average more than 44% of the WhatsApp topics (602) are also posted on news outlets’ Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram channels, usually as standalone message (one topic per message). The share of crossposts is highest for Facebook (72% of the topics were also sent to the news outlets’ Facebook pages), high for Twitter (57%) and very small for Instagram (2%). The small share of crossposts with Instagram for all newsrooms analyzed is due to the low use of Instagram (one-third of the news outlets have no Instagram account) and probably also due to Instagram’s focus on photos instead of text, which results in different topics and stories being selected by journalists.

Distribution: special characteristics as a mobile communication app? (RQ 1.2)

Length of messages

No overall WhatsApp standard message has developed yet but there are several distinct types that the different newsrooms have decided on. The main distinction is between posting short one-topic messages, often breaking news, and posting one or several longer news summaries with several topics.

In the human-coded data set we account for the different strategies by normalizing the length of a message to the number of topics. The average length per topic is 202 characters, including white spaces. This is the exact same length as the last two sentences above. The analysis excludes links and references to media attachments, which were added during the data export. The range between the average lengths per topic of the media outlets ranges from 86 to 416.

Due to the different strategies, the length of messages (in number of characters per message) in data set CM varies significantly between newsrooms. The average length of a message (without links and references to media attachments added when exporting the data) is 508 characters (median: 399, minimum 0, maximum 2027). Strategies of newsrooms vary: Some sent very standardized messages with little variation in length (less than 200 characters between 25% and 75% quantiles, WDRE public service broadcaster, TV & radio), while others have a large range of 800 characters between 25% and 75% quantiles (RP, regional newspaper).

Media attachments and links

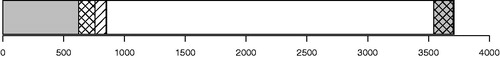

The shortness per topic is compensated by additional optional material. Seventy-seven percent of the messages contain a link (see ). Ten percent of all messages contain a media attachment, of which photos are most common (7.8%). Eighty-three of all messages contain a link or a media attachment. About 4% contain both. Although the overall trend is offering additional content for an audience that is news snacking (two-thirds of all outlets predominantly send messages with links), differences between the strategies of media outlets exist. Three outlets Handelsblatt (HB), Neue Westfälische (NW), Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (WAZ) send only one type of message (messages including links). Six outlets Aachener Nachrichten (AN), Express (EX), Mindener Tageblatt (MT), WDR Aktuell (WDRA), WDR Studio Essen (WDRE), WDR Studio Wuppertal (WDRW) send four or more different types of messages resulting in a broader mix of additional optional material.

Figure 2. Stacked barplot of all messages sent to WhatsApp distribution channels of German media outlets in North Rhine-Westphalia. Results from the computational methods data set. Gray messages were sent without attachment, hashed ones with photos, striped ones with audio and black ones with videos. All messages sent with links are white, and the gray hashed and small black areas on the right represent messages sent with link and photo, or link and video, respectively.

Topical differences

In the human-coded data set with 220 messages 602 topics were coded into 14 different categories. The most frequent topic was crime (34.4% of all topics). Other frequent topics are politics (10.6%), sports (10.5%), transportation (10.0%), entertainment (9.0%), and economy (5.6%). The dominant topics and the numbers of different topics distributed vary between newsrooms with the state level public service medium (WDRA) sending predominantly political news and a high number of messages on international affairs. The only national press outlet in the data set (HB) sends only political and economy news, while three regional newspapers publish news on 12 (KSTA, RP) and 13 different topics (NW), respectively. This indicates that some but not all outlets have reduced the “news gap” (Boczkowski and Mitchelstein Citation2013) and adjusted to news snacking practices.

Ubiquity and frequency of messages

WhatsApp distribution channels are not ubiquitous if focusing on the frequency of messages. On average news outlets sent 1.96 messages per day to their WhatsApp distribution channels. The smallest mean of an outlet is 1 and the highest 4.0. The highest number of messages sent per day is 18 from Aachener Nachrichten on 19th July, when an international horse show was held in Aachen.

WhatsApp distribution channels are ubiquitous if focusing on the hour of day that the messages were sent. Messages were sent throughout the time the audience is assumed to be awake (between 6 am and 10 pm in each hour more than 3.5% of the messages were sent). The period between 8 am and 9 pm had a higher number of messages (>5.5%). WhatsApp channel prime times were 10 am and 5 and 6 pm (>8%). WhatsApp distribution channels also sent messages at night, usually in breaking news situations, for example, storm warnings or fires.

Audience engagement in messages: little use of WhatsApp’s special characteristics as an interpersonal communication app (RQ 2.1)

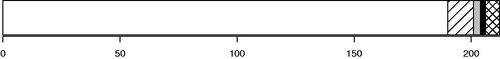

Analyzing the messages in the human-coded data set we searched for phrases indicating an interest by journalists to engage with their audience. Audience engagement was defined broadly as any requests for participation by the journalists or reactions to messages users had sent. Results show that journalists make little use of WhatsApp’s special characteristic as an interpersonal communication app and hardly engage with their audience. Engagement happens only at 5 of the 15 media outlets. On average 10.4% of the messages contain evidence of engagement (see ). These 22 messages predominantly contain small talk as a form of audience engagement (11), the other forms are opinion requests (3), requests to participate in a prize competition (9), and other requests (2). Among the 22 messages are three that contain two different types of engagement (small talk and a request to participate in a prize competition).

Figure 3. Stacked barplot of evidence of audience engagement in the human-coded data set. White messages were sent without evidence of audience engagement, striped ones with small talk, gray ones with crowdsourcing requests, black ones with opinion requests, hashed ones with requests to participate in a prize competition.

Journalists and audience engagement: survey indicates potentials and reluctance to embrace them (RQ 2.2)

Results of the survey indicate that journalists are rather reluctant to embrace the relational change associated with the WhatsApp engagement channel. However, the potential for a comprehensive change of the relationship with their audience exists.

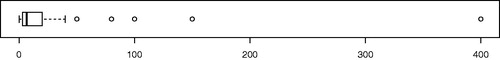

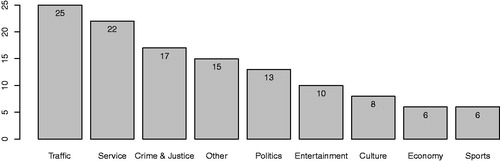

Journalists state that their newsrooms receive an average of 22.2 messages on a regular day (median = 6.5, SD = 55.9, N = 60, see ) of which they answer 78% (median = 90, N = 54). Journalists get the highest number of messages after content including traffic news and service (see ); for service the examples music requests and call-ins were given. Eighty-eight percent of the journalists receive feedback (defined as user opinion on the content and coverage) via WhatsApp (N = 56). Fifty-one percent state that sentiment of the feedback is predominantly positive, only 2% say predominantly negative and 45% state that it is even. Furthermore, they receive story pitches (66%, N = 56) – on average 4.5 in a regular week (median = 3, SD = 5.4, N = 35).

Figure 4. Number of messages the newsrooms receive on a regular day via their WhatsApp channels as given by journalists participating in the survey.

Figure 5. Issues that receive the most reaction to WhatsApp channels as stated by journalists participating in the survey. Multiple answers were possible (N = 56).

However, journalists say that in the last four weeks they included only 2.3 issues that were pitched via WhatsApp in their coverage (median = 1, SD = 2.5, N = 35). Only 59% of journalists stated that their newsrooms would actively ask users to send input via WhatsApp (N = 56). Only few respondents answered the question why they were not using WhatsApp as an engagement channel, which makes answers to this highly relevant question not generalizable. Those who answered gave the effort to answer and the lack of personnel as the main reasons (N = 5, N = 6) ().

Table 2. Overview of the findings giving the phase of innovation of WhatsApp for news for the WhatsApp distribution channels of German media outlets in North Rhine-Westphalia.

Conclusions and discussion

WhatsApp channels provide a potentially new way for journalists to communicate to and with their audiences. WhatsApp is an app designed for mobile and interpersonal communication and is commonly used in all age groups. WhatsApp channels could enable news outlets to be closer to their audience in two aspects: distribution and engagement. WhatsApp channels can be used as distribution channels to distribute content to the audience, in particular if the audience reduces the use of other ways of distribution (traditional print newspaper or broadcasting as well as social media brands that are becoming unpopular). Due to WhatsApp’s origin as a messenger few usability barriers exist and journalistic use has the potential to enlarge the group of people participating in the production of journalism. Our case study of German WhatsApp news channels examined the level of technological change (distribution) and relational change (engagement) of the approaches the different media outlets have taken. Ultimately, despite the innovative potential, the results of our German case study show that journalists only slowly develop new practices for WhatsApp channels. This result resembles the findings of studies on the adaption of Twitter (Lasorsa, Lewis, and Holton Citation2012; Bruns Citation2012; Hermida Citation2013).

With regard to technological change, news content distributed via WhatsApp already differs from other social media platforms (RQ 1.1). Twenty-five percent of topics are exclusively distributed via WhatsApp. Thus, WhatsApp for news is another example for the “dislocation of news journalism” (Ekström and Westlund Citation2019). The study shows how newsrooms partly employ a “platform-specific” (Erdal et al. Citation2019) approach, creating journalistic content uniquely for mobile, which highlights the importance of research into “locative media” (Erdal et al. Citation2019). Results regarding the adaption of the WhatsApp editorial process to the ubiquity of mobile communication and news snacking practices are mixed (RQ 1.2): There is no ubiquity in number of messages but ubiquity in time of day when the messages were sent. Outlets send short messages per topic usually combined with links or media attachments reporting on public-affairs and non-public-affairs news. Although the results of RQ1.1 and 1.2 show reluctance of journalists to innovate and adapt to common habits of mobile communication, it is subject to critical discussion whether newsrooms should adapt to these practices. Previous studies suggest the implications of ubiquity and snacking might be negative because less information is conveyed to the audience (Molyneux Citation2018).

Results on the engagement with the audience illustrate only small aspects of relational change (RQ 2.1 and 2.2). These findings are similar to the findings by Ekdale et al. (Citation2015), who found that technological change is faster than relational or cultural change in a newsroom. Just 8% of WhatsApp messages sent by outlets contain a dimension of audience engagement (RQ 2.1). This finding is in line with studies elaborating on the limited experiences of journalists with audience engagement and the challenges associated with it (Lawrence, Radcliffe, and Schmidt Citation2018; Meier, Kraus, and Michaeler Citation2018; Loosen Citation2016). In our survey only 59% of journalists stated that their newsrooms would actively ask users to send input via WhatsApp (RQ 2.2). Despite receiving messages, journalists say that in the last four weeks they included only 2.3 issues which were pitched via WhatsApp in their coverage. These results are in line with findings indicating that journalists view the audiences not as partners collaborating on news stories but as “active users” (Hermida et al. Citation2011; Cozma and Chen Citation2013; Noguera-Vivo 2013). Further, we find that the challenging perspective of “dark participation” (Quandt Citation2018) is a minor factor for WhatsApp, although it has become apparent for other social media (Loosen Citation2016). In contrast to other social media and news sites, journalists do not have to moderate comments sections when distributing news via WhatsApp. Only 2% of journalists say they receive predominantly negative feedback. Engagement in WhatsApp news channels can be seen as an example of “good participation” (Kligler-Vilenchik Citation2018) rather than Quandt’s (Citation2018) notion of “dark participation”. However, audience engagement returns to a more traditional setup with gatekeeping journalists and without direct interaction within the audience.

Some newsrooms use WhatsApp more independently from established social media than others and have higher percentages of messages with audience engagement. The findings indicate different levels of innovation diffusion in the newsrooms analyzed with yet only few accepting the relational change coming with the technological change. This could originate in path dependencies: journalists select and edit content for WhatsApp in a similar way as for other social media before and do not change their routines, which has been observed by Lasorsa, Lewis, and Holton (Citation2012), Ekdale et al. (Citation2015), and Broersma and Graham (Citation2013). However, for their audience WhatsApp is a mobile, interpersonal communication app, which is used differently than other social media. For journalists, not adapting to this could result in disappointment of their audiences, for example, members of the audience could be dissatisfied with the speed or frequency with which journalists get back to their messages. Further risks for newsrooms using WhatsApp originate in the potentially large engagement. Angeluci, Scolari, and Donato (Citation2017) explained how Brazilian news outlets had to find new practices for verifying material that was sent via WhatsApp.

With WhatsApp channels, journalists face additional challenges to bridge their different communities. They are a chance to win back users who might otherwise be lost for journalists because they do not use established journalistic channels anymore to engage with the news. This phenomenon has been described by Swart, Peters, and Broersma (Citation2018a, Citation2018b), who analyzed sharing and discussing news in private social media groups and by journalists who stated this as an argument to start a WhatsApp channel (Jenkins and Nielsen 2018). However, WhatsApp channels are an off-label use – the audience must be persuaded to allow news outlets into a more personal space and not all users might be accessible via WhatsApp channels. Studying Twitter, Bruns (Citation2012) found that individual accounts of journalists were more important than the ones of media outlets. This would suggest that setting up an individual journalist’s WhatsApp channel might be more successful to reach users than a WhatsApp channel for a media outlet. Ultimately, not using the full technological and relational innovation potential of WhatsApp news channels is also a deliberate choice media outlets can make. Considering the power of nonproprietary platforms (Ekström and Westlund Citation2019), the number of different social media channels, and limited resources, it may be sensible for newsrooms to employ a platform-agnostic approach (Erdal et al. Citation2019).

Our case study analyzed the technological innovations of WhatsApp news channels and shed some much needed light on audience engagement via WhatsApp. A limitation of this study is its focus on one country. Thus, results are not generalizable to other countries without additional analysis. The study was limited to a window of several months and changes over time were not analyzed. Results of the survey should be further validated with qualitative interviews to secure responses to all questions. Further research into factors influencing the innovativeness of newsroom’s WhatsApp channels and into the channels’ audiences is needed. Moreover, using the lens of domestication theory (Silverstone, Hirsch, and Morley Citation1991) could be helpful to better understand the complexity of WhatsApp’s adaption in the newsroom.

Acknowledgments

Part of the work on this paper was done at the Dortmund center for data-based media analysis, TU Dortmund University. The authors would like to thank Jonas Rieger for adapting our R package tosca for the analysis of WhatsApp content, the students of the summer 2018 journalism studies project at TU Dortmund University for suggesting questions for the survey and sending it out to media outlets, and the editor, guest editors, and anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Agur, Colin. 2019. “Insularized Connectedness: Mobile Chat Applications and News Production.” Media and Communication 7 (1): 179–188. doi:10.17645/mac.v7i1.1802

- Angeluci, Alan Cesar, Gabriela Scolari, and Rita Donato. 2017. “WhatsApp as an Actor: The Impact of the Interactive Application on Newsroom Journalism.” Revista Mediacao 19 (24): 195–214.

- Baroni, Alice, and Andrea Mayr. 2018. “Tightening the Knots’ of the International Drugs Trade in Brazil.” Journalism Practice 12 (2): 236–250. doi:10.1080/17512786.2017.1397528

- Belair-Gagnon, Valerie, Colin Agur, and Nicholas Frisch. 2016. “New Frontiers in Newsgathering: A Case Study of Foreign Correspondents Using Chat Apps to Cover Political Unrest.” https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/catalog/ac:wstqjq2bxt.

- Boczkowski, Pablo J., and Eugenia Mitchelstein. 2013. The News Gap: When the Information Preferences of the Media and the Public Diverge. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Broersma, Marcel, and Todd Graham. 2013. “Twitter as a News Source.” Journalism Practice 7 (4): 446–464. doi:10.1080/17512786.2013.802481

- Bruns, Axel. 2012. “Journalists and Twitter: How Australian News Organisations Adapt to a New Medium.” Media International Australia 144 (1): 97–107. doi:10.1177/1329878X1214400114

- Cherubini, Federica, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2016. Editorial Analytics: How News Media Are Developing and Using Audience Data and Metrics. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=2739328.

- Costera Meijer, Irene, and Tim Groot Kormelink. 2015. “Checking, Sharing, Clicking and Linking.” Digital Journalism 3 (5): 664–679. doi:10.1080/21670811.2014.937149

- Cozma, Raluca, and Kuan-Ju Chen. 2013. “What’s in a Tweet?” Journalism Practice 7 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1080/17512786.2012.683340

- Damme, Kristin Van, Cédric Courtois, Karel Verbrugge, and Lieven De Marez. 2015. “What’s APPening to News? A Mixed-Method Audience-Centred Study on Mobile News Consumption.” Mobile Media & Communication 3 (2): 196–213. doi:10.1177/2050157914557691

- Dearing, James W., and Arvind Singhal. 2006. “Communication of Innovations: A Journey with Ev Rogers.” In Communication of Innovations: A Journey with Ev Rogers, edited by Arvind Singhal and James Dearing, 15–28. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India Pvt.

- Die Medienanstalten ALM GbR, ed. 2017. Jahrbuch 2016/2017 – Landesmedienanstalten Und Privater Rundfunk in Deutschland. Leipzig: Vistas.

- Dimmick, John, John Christian Feaster, and Gregory J. Hoplamazian. 2011. “News in the Interstices: The Niches of Mobile Media in Space and Time.” New Media & Society 13 (1): 23–39. doi:10.1177/1461444810363452

- Dodds, Tomás. 2019. “Reporting with WhatsApp: Mobile Chat Applications’ Impact on Journalistic Practices.” Digital Journalism 7 (6): 725–45. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2019.1592693

- Ekdale, Brian, Jane B. Singer, Melissa Tully, and Shawn Harmsen. 2015. “Making Change: Diffusion of Technological, Relational, and Cultural Innovation in the Newsroom.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 92 (4): 938–958. doi:10.1177/1077699015596337

- Ekström, Mats, and Oscar Westlund. 2019. “The Dislocation of News Journalism: A Conceptual Framework for the Study of Epistemologies of Digital Journalism.” Media and Communication 7 (1): 259–270. doi:10.17645/mac.v7i1.1763

- Erdal, Ivar John, Kjetil Vaage Øie, Brett Oppegaard, and Oscar Westlund. 2019. “Invisible Locative Media: Key Considerations at the Nexus of Place and Digital Journalism.” Media and Communication 7 (1): 166–178. doi:10.17645/mac.v7i1.1766

- Ferrer-Conill, Raul, and Edson C. Tandoc. 2018. “The Audience-Oriented Editor: Making Sense of the Audience in the Newsroom.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 436–453. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1440972

- Garrison, Bruce. 2001. “Diffusion of Online Information Technologies in Newspaper Newsrooms.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 2 (2): 221–239. doi:10.1177/146488490100200206

- Goh, Debbie, Richard Ling, Liuyu Huang, and Doris Liew. 2017. “News Sharing as Reciprocal Exchanges in Social Cohesion Maintenance.” Information Communication & Society 22 (8): 1128–1144.

- Gulyas, Agnes. 2013. “The Influence of Professional Variables on Journalists’ Uses and Views of Social Media.” Digital Journalism 1 (2): 270–285. doi:10.1080/21670811.2012.744559

- Hermida, Alfred. 2013. “#Journalism.” Digital Journalism 1 (3): 295–313. doi:10.1080/21670811.2013.808456

- Hermida, Alfred, David Domingo, Ari Heinonen, Steve Paulussen, Thorsten Quandt, Zvi Reich, Jane B. Singer, and Marina Vujnovic. 2011. “The Active Recipient: Participatory Journalism through the Lens of the Dewey–Lippmann Debate.” #ISOJ Journal: The Official Research Journal of the International Symposium on Online Journalism 1 (2): 1–12. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/55727961.pdf.

- Jenkins, Joy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. “The Digital Transition of Local News.” http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/publications/2018/digital-transition-local-news/.

- Karnowski, Veronika, Thilo von, Pape, and Werner Wirth. 2011. “Overcoming the Binary Logic of Adoption: On the Integration of Diffusion of Innovations Theory and the Concept of Appropriation.” In The Diffusion of Innovations. A Communication Science Perspective, edited by Arun Vishwanath and George A. Barnett, 57–76. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Kligler-Vilenchik, Neta. 2018. “Why We Should Keep Studying Good (and Everyday) Participation: An Analogy to Political Participation.” Media and Communication 6 (4): 111–114. doi:10.17645/mac.v6i4.1744

- Kligler-Vilenchik, Neta, and Tenenboim, Ori. Forthcoming. “Sustained Journalist-Audience Reciprocity in a Meso-Newspace: The Case of a Journalistic WhatsApp Group.” New Media & Society.

- Koppers, Lars, Jonas Rieger, Karin Boczek, and Gerret von Nordheim. 2019. “tosca. Tools for Statistical Content Analysis.” https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tosca.

- Larsen, Otto N. 1962. “Innovators and Early Adopters of Television.” Sociological Inquiry 32 (1): 16–33. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682X.1962.tb00527.x

- Lasorsa, Dominic L., Seth C. Lewis, and Avery E. Holton. 2012. “Normalizing Twitter.” Journalism Studies 13 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2011.571825

- Lawrence, Regina G., Damian Radcliffe, and Thomas R. Schmidt. 2018. “Practicing Engagement.” Journalism Practice 12 (10): 1220–1240. doi:10.1080/17512786.2017.1391712

- Leung, Louis, and Ran Wei. 1999. “Who Are the Mobile Phone Have-Nots?: Influences and Consequences.” New Media & Society 1 (2): 209–226.

- Loosen, Wiebke. 2016. “Publikumsbeteiligung Im Journalismus.” In Journalismusforschung, edited by Klaus Meier and Christoph Neuberger, 2nd ed., 287–316. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- McIntyre, Karen, and Meghan Sobel. 2019. “How Rwandan Journalists Use WhatsApp to Advance Their Profession and Collaborate for the Good of Their Country.” Digital Journalism 7 (6): 705–724. doi:10.1080/21670811.2019.1612261

- Meier, Klaus, Daniela Kraus, and Edith Michaeler. 2018. “Audience Engagement in a Post-Truth Age.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 1052–1063. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1498295

- Molyneux, Logan. 2018. “Mobile News Consumption.” Digital Journalism 6 (5): 634–650. doi:10.1080/21670811.2017.1334567

- Moon, Soo Jung, and Patrick Hadley. 2014. “Routinizing a New Technology in the Newsroom: Twitter as a News Source in Mainstream Media.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 58 (2): 289–305. doi:10.1080/08838151.2014.906435

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018.”

- Noguera-Vivo, José Manuel. 2013. “How Open Are Journalists on Twitter? Trends towards the End-User Journalism.” Communication & Society/Comunicación y Sociedad 26 (1): 93–114. https://www.unav.es/fcom/communication-society/es/articulo.php?art_id=438.

- Nordheim, Gerret von, Karin Boczek, and Lars Koppers. 2018. “Sourcing the Sources.” Digital Journalism 6 (7): 807–828. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1490658

- Paulussen, Steve. 2016. “Innovation in the Newsroom.” In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by Tamara Witschge, C. W. Andersson, David Domingo, and Alfred Hermida, 192–206. London: SAGE.

- Quandt, Thorsten. 2018. “Dark Participation.” Media and Communication 6 (4): 36–48. doi:10.17645/mac.v6i4.1519

- Radio NRW GmbH. 2018. “Radio NRW: Sendegebiet.” https://radionrw.de/nrw-lokalradios/sendegebiet.html.

- R Core Team. 2018. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Wien: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/.

- Rogers, Everett M. 2003. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Silverstone, Roger, Eric Hirsch, and David Morley. 1991. “Listening to a Long Conversation: An Ethnographic Approach to the Study of Information and Communication Technologies in the Home.” Cultural Studies 5 (2): 204–227. doi:10.1080/09502389100490171

- Singer, Jane B. 2004. “Strange Bedfellows? The Diffusion of Convergence in Four News Organizations.” Journalism Studies 5 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1080/1461670032000174701

- Struckmann, Samson, and Veronika Karnowski. 2016. “News Consumption in a Changing Media Ecology: An MESM-Study on Mobile News.” Telematics and Informatics 33 (2): 309–319. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2015.08.012

- Swart, Joëlle, Chris Peters, and Marcel Broersma. 2017. “Navigating Cross-Media News Use.” Journalism Studies 18 (11): 1343–1362. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2015.1129285

- Swart, Joëlle, Chris Peters, and Marcel Broersma. 2018a. “Sharing and Discussing News in Private Social Media Groups.” Digital Journalism 7 (2): 187–205.

- Swart, Joëlle, Chris Peters, and Marcel Broersma. 2018b. “Shedding Light on the Dark Social: The Connective Role of News and Journalism in Social Media Communities.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 4329–4345. doi:10.1177/1461444818772063

- Usher, Nikki. 2014. Making News at the New York Times. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

- Villi, Mikko, and José-Manuel Noguera-Vivo. 2017. “Sharing Media Content in Social Media: The Challenges and Opportunities of User-Distributed Content (UDC).” Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies 6 (2): 207–223. doi:10.1386/ajms.6.2.207_1

- Westlund, Oscar. 2015. “News Consumption in an Age of Mobile Media: Patterns, People, Place, and Participation.” Mobile Media & Communication 3 (2): 151–159. doi:10.1177/2050157914563369

- Westlund, Oscar, and Stephen Quinn. 2018. “Mobile Journalism and MoJos.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, edited by Jon F. Nussbaum. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.841.

- Wolf, Cornelia, and Anna Schnauber. 2015. “News Consumption in the Mobile Era.” Digital Journalism 3 (5): 759–776. doi:10.1080/21670811.2014.942497

- Zeitungsmap 2018. “Tageszeitungen Mit Vollredaktionen.” 2018. www.zeitungsmap.de.

- Zhu, Jonathan J. H., and Zhou He. 2002. “Diffusion, Use and Impact of the Internet in Hong Kong: A Chain Process Model.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 7 (2). doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2002.tb00139.x