Abstract

Until recently, the notion of emotion in media studies and communication research was mostly examined through the lens of cultural studies, media effects, and visuals. Research on emotion in journalism has been slow to arrive, as Karin Wahl-Jorgensen shows in this special issue. However, this is radically changing. Contributions by Hassan, Kilgo, Lough, Riedl, Sanchez Laws, Waddell, and Zou highlight how the affordances of digital journalism have an impact on the space for emotion in evaluating the relationships between journalists, journalistic content and their audiences. Embracing emotions as a dimension in digital journalism studies contributes to opening up interesting approaches towards concepts such as objectivity, and for more nuanced research on the power hidden in the ‘taken for granted’ in classic liberal journalism. While highlighting the liberating and empowering potential in the inclusion of emotions in journalism, there is also a need to focus on how affective dynamics can be spurred by phenomena such as conflict and hate. When introducing emotions in the journalistic loop, new questions arise, and perspectives of power and negotiations must be included in these discussions.

Keywords:

Until recently, the notion of emotion in media studies and communication research was mostly examined through the lens of cultural studies, media effects, and visuals. Research on emotion in journalism has been slow to arrive, as Karin Wahl-Jørgensen (Citation2019) shows in this special issue. However, this is radically changing. Contributions by Hassan (Citation2019), Kilgo, Lough, and Riedl (Citation2017), Sánchez Laws (Citation2017), Waddell (Citation2017), and Zou (2018) highlight how the affordances of digital journalism have an impact on the space for emotion in evaluating the relationships between journalists, journalistic content and their audiences. Embracing emotions as a dimension in digital journalism studies contributes to opening up interesting approaches towards concepts such as objectivity, and for more nuanced research on the power hidden in the ‘taken for granted’ in classic liberal journalism. While highlighting the liberating and empowering potential in the inclusion of emotions in journalism, there is also a need to focus on how affective dynamics can be spurred by phenomena such as conflict and hate.

Emotions have traditionally been understood as private and highly personalized experiences and, as such, seen as out-of-place in public debate. Often overshadowed by more dominant ideas of objectivity and impartiality, emotions have – as Charlie Beckett reminds us – always been part of journalism: through “inspiration, creation, style, appeal and its resonance or impact” (Beckett Citation2015). Some scholars have argued that the quest for objectivity may itself be a frame, resulting in news stories that reflect particular criteria of newsworthiness. In the words of feminist scholar Donna Haraway, objectivity tends to privilege the views of dominant groups at the expense of others, as “only partial perspective promises objective vision” (Haraway Citation1988, 190). The absence or misrepresentation of women in mainstream news media may be seen as a result of such perceived objectivity, reproducing certain power structures. The #metoo campaign, which was enabled by hashtag activism, involves a change in public focus towards more open discussions about the experiences of victims of sexual assault or unwanted sexual attention. Hostile reactions to the campaign show how revolutionary it is to put the consideration of a vulnerable person’s emotions first.

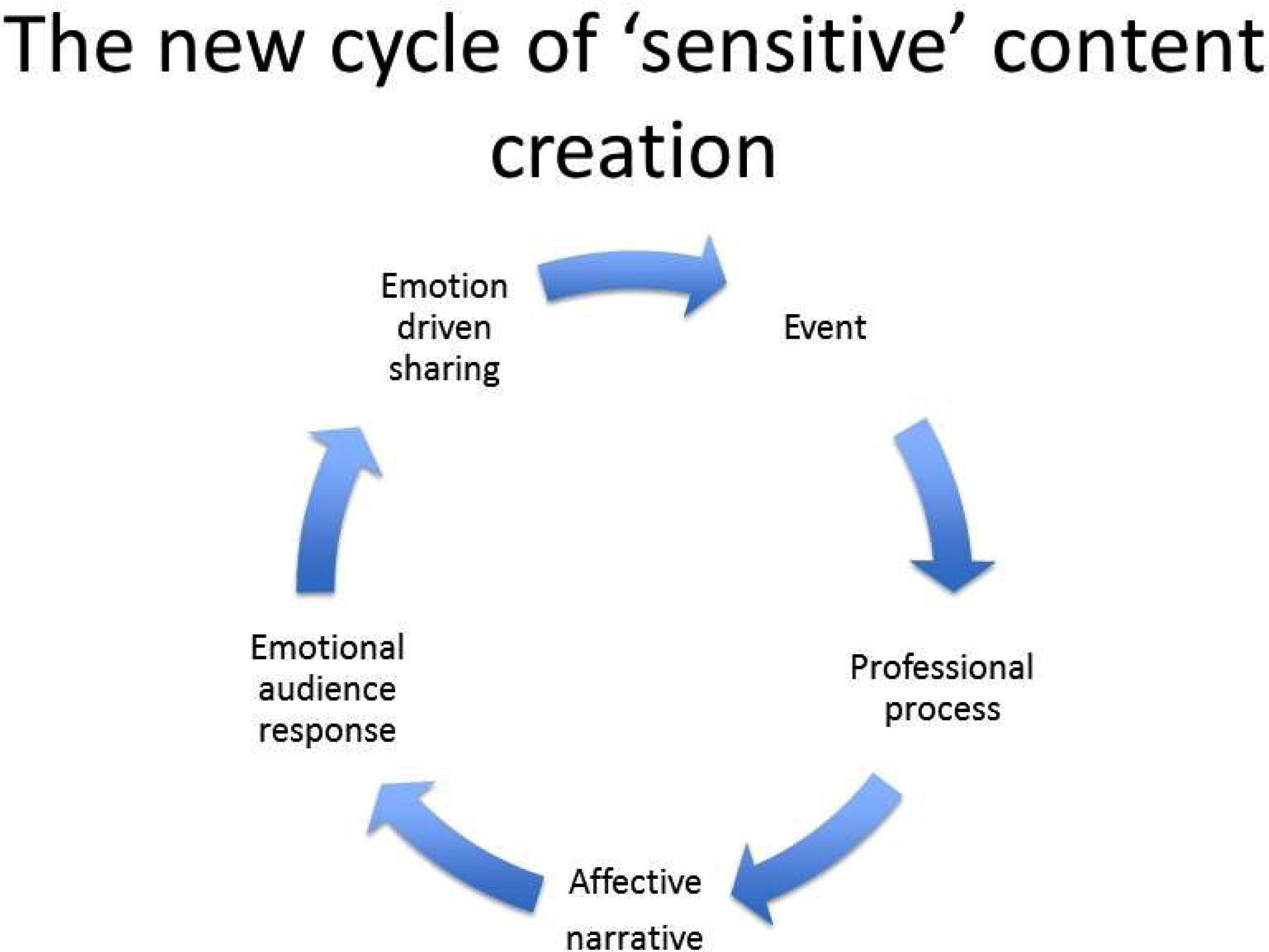

With the arrival of digital journalism emotions have gained significant new attention. Wahl-Jorgensen explains how “the expanded opportunities for participation have contributed to question traditional distinctions between news audiences and producers and have ushered in new and more forms of emotional expression that have spilled over into practices of news production” (Wahl-Jørgensen Citation2019). The current media landscape with its new “cycle of sensitive content creation” (Beckett Citation2015) is facilitating more personalized, participatory forms of journalism.

Beckett (Citation2015) describes how, with digital journalism, events are often reported and discussed on social media and journalists’ work is subject to comments and sharing – in fact, they share this process with the public, live, as they are working. As emotion becomes a more significant factor in this process for both the newsmaker and the news consumer or sharer, there is an interesting feedback loop to the profession that increasingly impacts on how future news is produced.

Emotional pressures of digital journalism practice

A focal aspect here is the emotional pressure the digital journalist is exposed to and what may be called the emotional pressures of work. As digital journalism is interactive, multi-platform, multi-linear and participatory, audiences’ emotions are projected back to the journalist more or less immediately. This may also include aggressive or violent emotions. Within the field of journalist safety, we see how an increasing number of reporters are attacked and how a rising number of journalists who are killed are reporters whose primary platform is internet based (Henrichsen, Betz, and Lisosky Citation2015). Journalists have become the customary target of online attacks and female journalists often face a double-burden: being attacked both as a journalist and as a woman. Threats of rape, physical violence and graphic imagery constitute a horrifying ‘new normal’ for female journalists worldwide, as reporting on digital platforms push journalists to be more personal. In addition, as journalists are often urged by their institutions to be visible and responsive to the audience as much as possible, they are ever more vulnerable to the emotions of readers. Therefore, it is important to be aware that the cycle of sensitive content creation may be used to spur hate and conflict, as well as more positive audience perspectives.

Lünenborg and Maier (Citation2018) show how current phenomena like hate speech and “shitstorms” via social media are to be understood as “explicit public articulations of emotions; at the same time they produce affective dynamics, which can be described as contagious and viral”. Hence, at the reverse side of the optimism surrounding the early days of digital media, many of the enthusiastic theoretical concepts on user engagement did not endure close empirical inspection (Quandt Citation2018). There is now an ever-increasing fear of populist turbulence, viral panics, experts under attack, and disinformation. Quandt introduces the concept of ‘dark participation’, where user engagement “instead of positive, or at least neutral contributions to the news-making processes” is characterized by “negative, selfish or even deeply sinister contributions” and how this development seems to grow parallel to the recent wave of populism in Western democracies (2018, 40). Some fear a perverted image of the new openness, where instinct and emotion overtake facts and reason in the digital age.

In particular, the combination of strong emotions and a lack of media and digital literacy may lead to populist turbulence. Ferdous (Citation2019) describes how millions of people in Bangladesh started to use the Internet without knowing much about fact-checking content or sources, making them easy targets for extremist Islamists. Instead of increasing freedom of expression through new media channels, these channels allowed for a rapid radicalization of people, and a quick erosion of moderate, knowledge-based and secular mentality. This is not unique to Bangladesh – rapid peer-to-peer information transmission has manufactured hate crimes in Germany, as well as resulted in ethnic violence in Sri Lanka, Myanmar and India. Journalists and other content producers need to be aware of the explosive potential of online rumours that may trigger physical mobilisations. As studies of Twitter content have confirmed, “emotive falsehood often travels faster than fact” (Davies Citation2018).

Chantal Mouffe’s (Citation2013) long-standing claim that democracies are in need of emotions and confrontations instead of just rationality and consensus – and how she draws on seventeenth century philosopher Spinoza’s two core emotions of fear and hope – gain new importance here. What we see with emotions in the digital sphere is that the confrontationally oriented content often wins terrain in the public sphere. As algorithms increasingly steer journalistic content to tap into readers’ emotions, values and identities, a central question for further research is whether this will lead to more bias and divide or to more engaging content and promote understanding.

Emotional intelligence and empathy

The algorithmic turn in digital news production was a key topic of the 2019 special issue of Digital Journalism, titled ‘Algorithms, Automation and News’. To continue to exist “outside the realm of what we can expect from robots”, Lindén believes journalists will be forced by algorithms “to think harder at defining their core human capabilities such as developing emotional and social intelligence, curiosity, authenticity, humility, empathy and the ability to become better listeners, collaborators and learners” (Lindén Citation2017, 71). The role of immersive virtual reality journalism in creating empathy is of great interest – as discussed by Sánchez Laws (2019) and Hassan (Citation2019) in this special issue. Feelings of concern and compassion are emphasized, reflecting the ‘hope’ side of Spinoza’s oppositional pair. However, a crucial topic, which is only mentioned in passing in the conclusion of Sánchez Laws’ article, is how internal representations of emotions can also involve negative ones where audiences respond “with hatred and anger towards the world within and outside virtual reality” (Sánchez Laws Citation2017, 11). The need to introduce a higher degree of conflict awareness to these discussion gains magnitude as the potential to create action in the real world potentially increases with immersive journalism. Other contributions place more emphasis on the perspective of fear or negativity, such as Zou (2018) when studying the role of fear as contributing to civic engagement and Waddell (Citation2017), who finds that audience feedback on news teasers on social media are often uncivil.

Continuing from this, we need to ask more nuanced questions related to whether a cycle of emotionally driven content creation will open up for a broader spectre of more diverse voices in the news or only give room to the loudest ones. And what happens to the ‘boring but important’ information in this process? Such discussions are so far largely missing.

Beckett’s (Citation2015) feedback loop says little about the relationship between emotion driven sharing and bringing involvement or action in the real world. Exploring the impact of different types of constructive news stories on readers’ motivation, Baden, Mcintyre, and Homberg (Citation2019) found that news stories that evoked negative emotions reduced intentions to take positive action to address the issues. In contrast, solution-framed stories that evoked positive emotions resulted in a more positive affect and higher intentions to take positive action. As an increasing number of scholars and journalists argue that remaining impartial is an inadequate response to challenges such as sexism, racism or climate change, I would argue that there is a vital need for more discussion of what an “innate sense of right and wrong” (Glück Citation2019) is involved in the context of emotionally driven, normative journalism.

Including perspectives of power and negotiations

Research in neuroscience and psychology shows that emotions are not the enemy of reason, but rather a crucial part of it (e.g. Bandes and Salerno Citation2014). As human beings we understand the world both cognitively and emotively. Therefore, it is both reasonable and commended to continue including emotions in the field of digital journalism studies (DJS), while at the same time arguing that values, such as accuracy and factuality, remain in a mix that can strengthen and safeguard the ever-important credibility of journalism. When introducing emotions in the journalistic loop, new questions arise, and I have emphasized the need to increasingly include perspectives of power and negotiations in these discussions. Future research questions may include, for example: Whose emotions are guiding the various phases of the cycle of content creation? How is power negotiated in this process? Perhaps Mouffe’s (Citation2013, 7) conflict model aimed at enabling a manageable conflict between opponents (agonism) instead of an out-of-control and irreparable enmity (antagonism) may gain new importance in further refinements of the field.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Baden, Denise , Karen Mcintyre , and Fabian Homberg . 2019. “The Impact of Constructive News on Affective and Behavioural Responses.” Journalism Studies 20 (13): 1940–1959.

- Bandes, Susan A. , and Jessica M. Salerno . 2014. “Emotion, Proof and Predjudice.” Arizona State Law Journal 1003.

- Beckett, Charlie. 2015. “How Journalism is Turning Emotional and What That Might Mean for News.” http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/63822/

- Davies, William. 2018. “How Feelings Took over the World.” The Guardian, 8 September.

- Ferdous, Jana Syeda Gulshan. 2019. “Bangladesh: Social Media, Extremism and Freedom of Expression.” In Transnational Othering. Global Diversities, edited by E. Eide and K. S. Orgeret 101–118. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Glück, Antje. 2019. “Should Journalists Be More Emotionally Literate?” European Journalism Observatory. https://en.ejo.ch/ethics-quality/should-journalists-be-more-emotionally-literate

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges. The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599.

- Hassan, Robert. 2019. “Digitality, Virtual Reality and the ‘Empathy Machine.” Digital Journalism 8 (2)

- Henrichsen, Jennifer R. , Michelle Betz , and Joanne M. Lisosky . 2015. Building Digital Safety for Journalism: A Survey of Selected Issues . Paris: UNESCO.

- Kilgo, Danielle K. , Kyser Lough , and Martin J. Riedl . 2017. “Emotional Appeals and News Values as Factors of Shareworthiness in Ice Bucket Challenge Coverage.” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 1–20.

- Lindén, Carl-Gustav. 2017. “Algorithms for Journalism; the Future of News Work.” The Journal of Media Innovations 4 (1): 60–76.

- Lünenborg and Maier . 2018. “The Turn to Affect and Emotion in Media Studies.” Media and Communication 6 (3): 1–4.

- Mouffe, Chantal. 2013. Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically . London: Verso.

- Quandt, Thorsten. 2018. “Dark Participation.” Media and Communication 6 (4): 36–48.

- Sánchez Laws, Ana Luisa. 2017. “Can Immersive Journalism Enhance Empathy?” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/216.70811.2017.1389286.

- Waddell, Franklin T. 2017. “The Authentic (and Angry) Audience.” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 236–255.

- Wahl-Jørgensen, Karin. 2019. “An Emotional Turn in Journalism Studies?” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 1–20.

- Zou, Cheng. 2018. “Emotional News, Emotional Counterpublic.” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 1–20.