Abstract

Push notifications provide news outlets with direct access to audiences amid concerns around information overload, disinformation, and heightened competition for reader attention. Such news distribution is relevant because it (a) bypasses social media and news aggregators, reaching readers directly; (b) alters the agency and control of temporal news personalisation; and (c) reinforces mobile as the locus of contact between news organisations and audiences. However, push notifications are a relatively under-researched topic. We explore news organisations’ use of alerts, considering whether they attempt to integrate with existing mobile-user behaviour patterns or seek to be a disruptive element, garnering attention when audiences are not typically using devices. Through quantitative content analysis, this study examines the temporality of push notifications (n = 7092) from nine Northwestern European countries, comprising 34 news outlets. These data allow for comparisons at two levels: publisher type and national context. The study shows how the temporal patterns of push notifications’ dissemination align with existing news consumption behaviours; concepts of content-snacking and audiences’ rhythms and rituals are a useful lens through which these immediate, concise texts can be considered. Our findings show that news organisations use the mobile channel for attracting and maintaining users’ attention, with varying interpretations of temporal customisability.

Mobile Push Notifications as Personalised News Dissemination

As news consumption on mobile phones continues to grow (Newman et al. Citation2019), the convergence between broadcasting to all mobile users and personalising their content is still in its formative years. From the early approaches of push notification alerts via SMS and MMS (see Westlund Citation2013) to the deployment of news apps (see Schmitz Weiss Citation2013), news outlets continuously try to capture audience engagement with technological systems that produce short-term, fragmented information, connecting with what Elliot and Urry (Citation2010) call on-the-go lifestyles. In production terms, mobile technology has spurred the appearance of locative journalism (Nyre et al. Citation2012) and “MoJo” mobile journalists (Westlund and Quinn Citation2018). Mobile has also become an essential factor within the “cross-media news repertoires which individuals draw on as resources” (Schrøder Citation2015, 71) for everyday news consumption, often complementing news consumption, rather than substituting it. For example, Xu et al. found that “the adoption of a mobile news app significantly increases the probability of visiting the provider’s corresponding mobile website” (Citation2014, 109). This is also true for push notification alerts which is selected and directly “pushed” into users’ mobile phones (Fidalgo Citation2009).

The importance of push notifications is both journalistic and societal, as it restructures existing temporal and spatial conceptualisations within communication (Castells et al. Citation2007). To news organisations, the mobile device ubiquity affords media exposure beyond traditional conceptions of space and time (Peters Citation2012) providing direct access to news audiences, bypassing social media and news aggregators (Westlund Citation2015) whenever they want. Moreover, in a news media landscape where disinformation campaigns are difficult to control due to the prevalence of social media, news organisations try to regain relevance by bringing audiences back to proprietary platforms (Westlund and Ekström Citation2018). This means that news outlets can wait for news seekers to “pull” information, but outlets also have the ability to “push” content and directly engage with audiences. For the audience, this provides a way to receive news directly from trusted sources, with higher flexibility in where and when they access the news (Duffy et al. Citation2020). It also means introducing a layer of personalisation to news services, even potentially providing options for the time of day which audiences choose to receive alerts. We borrow Thurman and Schifferes’ definition of personalisation as “a form of user-to-system interactivity that uses a set of technological features to adapt the content, delivery, and arrangement of a communication to individual users’ explicitly registered and/or implicitly determined preferences” (2012, 776).

Considering the adoption of mobile use for news consumption varies according to national and cultural context (Westlund Citation2010), this study explores how news organisations in different countries integrate and deploy mobile notifications. Here, we adopt the common terminology such as mobile alerts or push notifications, but acknowledge alternative naming, such as push alerts or push messages, as part of an overarching trend of delivering news in short form, directly to mobile devices (Ling et al. Citation2020). Our purpose is to focus on the temporal aspect of push notifications and whether there are existing mobile-user behaviour patterns, and comparing how different news outlets use push notifications. We also investigate the temporal-based personalisation features which push notification services and apps offer consumers. We do so by analysing the push notifications (n = 7092) and distribution patterns of 34 news organisations in nine northwestern European countries. This study contributes to a surprisingly sparse body of knowledge on mobile notifications with a first glimpse of an increasingly strategic distribution channel.

We start by providing a literature review on the temporal aspects of news, the audience-orientation process of journalism, and the personalisation and customisation of mobile notifications. Then we outline the method and study rationale before presenting the results. This article concludes with a discussion on the meaning of push notifications while outlining a future research agenda.

The Flow of News Consumption? Time, Personalisation, and Audience Orientation

Research focussing on mobile notifications is scarce and has only partly studied push notifications as one of mobile journalism’s many components (see López-García et al. Citation2019). Fidalgo (Citation2009) mapped the Portuguese news media alerts service and found that personalisation of notification services resided within the paid options at a time when SMS was the predominant option. Fidalgo contends that due to the personalised mass communication nature of mobile phones, news organisations should be aware that “the amount, the kind and the frequency of the news individuals want to receive through push technology is totally dependent upon them” (2009, 120). Over the past decade, push notifications have been described as the “fastest-growing gateway to news” (Newman et al. Citation2018), leading to increased usage from news outlets as alerts grow in popularity, especially among younger audiences (Newman et al. Citation2019).

One difference between regular news and push notifications resides in the time and place of consumption: push notifications extend the exposure to cherry-picked news in spaces and moments which usually would not include news consumption. Newman proposes that mobile alerts are seen by publishers as a channel to attract attention and “rebuild direct relationships with users” (Citation2016, 7), but suggests news apps are involved in a “battle for the lockscreen,” ultimately fighting for audience attention. We believe push notifications are indicative of news organisations’ attempt to influence how and when audiences consume news, a task that has historically proven challenging. According to the 2018 Digital News Report (Newman et al. Citation2018), 16% of those surveyed had received a notification in the past week, ranging from 35% in Mexico to 5% in Czech Republic. However, 37% of users said nothing would encourage them to get notifications, while 18% said they would if they could assert some control over the number of alerts received. Brown (Citation2017) provides an overview on how US news outlets use mobile alerts, finding those organisations sent an average of 3.2 notifications per day, containing details and context of events, predominantly via plain text (only one-third of outlets used rich media). Additionally, Brown found that the reason behind push notifications is the intention to build and maintain brand loyalty, to drive audiences to their proprietary platforms (apps or websites), and to enhance segmenting and personalisation. In a follow-up study, Brown (Citation2018) noticed some strategic changes, suggesting there is no settled approach to push notification use. Although alerts are traditionally associated with breaking-news events and are considered an affordance of the constant-news-update environments of networked news outlets (Rom and Reich Citation2020; Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Neiger Citation2018), there may be a shift away from breaking news towards more exclusive brand content (Brown Citation2018). Finally, Stroud, Peacock, and Curry (Citation2020) found that while push notifications provide minimal increased learning about the news, they do increase news use among users who opt to receive push notifications more than those who have notifications disabled.

This study is interested in the three main features that these previous studies highlighted and which are vital to how news organisations deploy push notifications: the temporal aspect of news, the personalisation of news, and journalism’s audience-orientation.

Synchronising the Times of News Production and Consumption

Journalism can be considered a cultural practice dependent on a temporal and spatial context in which the relevance of news grows according to the temporal and geographical proximity of the events covered (Carlson Citation2016). Echoing Peters, “thinking ‘spatio-temporally’ helps us distinguish the unique from the routine, the extraordinary from the ordinary, the significant from the mundane” (2015, 10). However, the temporal dimensions of journalism go beyond story content (Tenenboim-Weinblatt Citation2014) as production and consumption times are also crucial when estimating the importance of journalism (Bødker and Brügger Citation2018) and how audiences engage with the news (Steensen, Ferrer-Conill, and Peters Citation2020). Ubiquitous mobile connectivity and multiplatform publishing outlets have led to hyper-immediacy where journalists, in the pursuit of breaking stories and providing constant updates, can produce confusing and misleading reporting (Karlsson Citation2011). And while the production of news may be continuous, its distribution often adheres to distinct time patterns (Wheatley and O’Sullivan Citation2017), as legacy printing/broadcasting follow sequential and programmatic schedules. News is made available to the public in a routine fashion, and even 24-h news channels follow scheduled cycles of headline summaries. However, as Lewis, Cushion, and Thomas (Citation2005) found, while allowing audiences to tune it at any time, 24-h news channels fail to provide context or analysis to breaking news and are less informative than regular news broadcasts on legacy media. Similarly, Nelson (Citation2020) found that while there are patterns of news consumption that change, such as time and space, other aspects, such as the sources audiences turn to for news, remain similar between mobile and desktop platforms.

Providing the public with constant news demonstrates the importance of time in news consumption. For networked audiences, the timeliness and rhythms of news consumption transcend the traditional temporalities of legacy news distribution, such as broadcasts and press cycles (Ananny Citation2016). News consumption is “increasingly temporally fragmented and/or unhinged from specific social situations” (Bødker Citation2017, 62). News organisations seek to capitalise on the fragmented form of news consumption and use push notifications to increase the ‘time spent’ on news during shorter, more frequent, moments. For example, Newman et al. (Citation2019, 56) identified four key moments of news consumption for young people: (a) dedicated moments where they give time to news (usually evenings and weekends), (b) a moment of update (usually the mornings), (c) time fillers (commuting or queuing), and (d) intercepted moments where they receive news notifications or messages from friends with news. Thurman (Citation2018) found that audience-time spent engaging with the news online is already higher via mobile than PC in the UK and has ample room to grow since they are important channels as time fillers, updates, and direct targets of news organisations. However, while Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer (Citation2020) find that time spent is not necessarily a good measure for the quality of news experience, studies in news consumption suggest that increased personalisation captures users’ attention by increasing their time spent engaging with news (Thurman Citation2018; Thurman and Schifferes Citation2012; Van Damme et al. Citation2015). Thus, we consider whether outlets are perhaps trying to extend the time audiences spent consuming content to better align with the all-day news publishing and production cycles which are an inherent part of contemporary news organisations’ practices.

Personalised News and the Agency over News Consumption

Networked mobile platforms and social media have caused “disruptive transformations on the underlying spatial and temporal formations of news” (Sheller Citation2015, 18) for traditional news organisations. This transition resulted in what Hermida calls ‘ambient journalism’ as a “broad, asynchronous, lightweight and always-on communication systems [that] are creating new kinds of interactions around the news, and are enabling citizens to maintain a mental model of news and events around them” (2010, 298). Extending the time in which the public has access to news is seen as a positive development by the industry. However, the constant presence of ambient journalism shifted the news consumption towards non-proprietary platforms, but letting news consumption exist outside traditional journalistic outlets further decreased news organisations’ authority and control (Westlund and Ekström Citation2018), including the rise of disinformation campaigns. To address this problem, news organisations have attempted to provide more direct and personalised news experiences. As mentioned, “news publishers’ primary motivation in pushing content out is to get those who receive or view it to click the embedded links, bringing them back to the publishers’ own outlets” (Thurman Citation2018, 1425).

In this study, we are particularly interested in the push notification features related to personalising temporal components of news consumption. Personalisation and push notifications are separate models that work well combined, as personalisation is supposed to allow audiences to customise their news experience. Indeed, mobile alerts and push notifications are part of the taxonomy of personalisation that news organisations are including in their distribution packages (Thurman and Schifferes Citation2012). However, personalisation of news presents several challenges to news organisations: (a) conflicting reading objectives; (b) difficulty of filtering information to fit user interests; (c) ways to generate a user profile; (d) novelty of information; and (e) the depth of personalisation (Lavie et al. Citation2010). However, the depth of personalisations is particularly problematic, as the range of news personalisation is diverse and allows topic and location customisation that is either human-driven or algorithmically driven (see Haim, Graefe, and Brosius Citation2018; Zuiderveen Borgesius et al. Citation2016). These tools and possibilities mean outlets have the ability to learn what people want to consume, and can then adapt and provide this content. This, therefore, suggests that there is more at stake from personalisation options than increased audience agency. Instead, the “news gap” (the difference between what news producers believe to be important, and what audiences actually want) could actually be slowly closing because of news personalisation (Boczkowski and Mitchelstein Citation2013).

Distinct Patterns of News Use? Adapting to the Audience

Time and personalisation are tactics that news organisations have always used to reach specific audiences. Historically, morning papers and evening papers often offered different types of content targeting different audiences. In west-northern Europe and the United States, morning papers were aimed at up-market readers, while evening tabloids offered more popular content (Westlund and Färdigh Citation2011). Newspapers and TV broadcasts had specific times of consumption connected to publication or broadcasting times. Audiences had to tune in to “catch” the news.

The transition to digital has seen stronger segmentations of newsreaders, spreading news consumption more evenly during the day, rising steadily from early morning until 2pm, flattening until a peak between 7pm and 9pm, then dropping for the rest of the night (Read Citation2017). Moreover, an analysis of time spent consuming news online showed that “for each hour of the day there is much less of a pattern with reach, with three distinct peaks of news consumption: 6–7pm, 4–5pm, and 12–1pm” (Read Citation2017, n.p.). However, mobile news consumption in isolation shows much flatter distribution from 6am until 12am, meaning mobile audiences consume news in spare moments throughout the day (Benton Citation2011). This is consistent with Molyneux’s (Citation2018) and Van Damme and colleagues’ (2015) assessment on mobile news consumption as a more frequent, brief check-ups to see what is new. This practice of “news snacking” is present on other platforms but more prevalent on mobile (Molyneux Citation2018). What remains unclear is whether push notifications attempt to fill those moments of snacking, or whether they are the actual reason for those brief check-ups.

Heinderyckx suggests that instant updates, regardless of one’s location, is “now in the DNA of the information society” (Citation2011, 112). Yet this was not always the case, nor has it always been audiences’ desire. Comparing 2011–2014 with 2004–2005, Costera Meijer and Groot Kormelink (Citation2015) find that idle “micro-periods” (e.g., bus stop, bathroom, waiting for appointments) were padded with news to a larger extent in 2011–2015. In 2004–2005, participants did not want news on their mobile phones (via SMS) as they interpreted it as an unwelcome interruption. While contemporary push notifications remain interruptive, the fact that users signed up for updates made them welcome the alerts, and news became integrated alongside other online activities. Costera Meijer and Groot Kormelink describe the “checking cycle,” in which people check email, social network apps, news, etc, in quick sessions: “The aim is to continuously stay on top of all that happens in your personal life and the world at large” (2015, 670).

The widespread use of readers’ metrics and analytics informs newsrooms about the patterns of audience consumption, allowing newsworkers to plan their distribution patterns (see Zamith Citation2018). This implies that news organisations follow a strategy that fits the consumption patterns of their readers when planning mobile alerts, strengthening outlets’ audience orientation (Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc Citation2018). However, we believe the increase of push notifications both follow traditional consumption temporalities by pushing news predominantly when audiences consume news, while at the same time capitalising on fragmented news “snacking” by reaching out at specific times and bringing users back to proprietary platforms, instead of letting users roam online.

Theoretical Synthesis and Research Questions

The complexity of news temporalities has shifted from a planned, almost rhythmical, news distribution to a more constant, ubiquitous ‘ambient journalism’ (Hermida Citation2010). Particularly with mobile, we see a convergence between how news is disseminated online and how news is consumed on mobile (Molyneux Citation2018). However, research tells us that the emergence of push notifications owes its expansion to brand loyalty and an attempt to bring audiences to news organisations’ proprietary platforms (Westlund Citation2015). Moreover, push notifications afford processes of news personalisation (Thurman and Schifferes Citation2012) which make it easier for the patterns of news dissemination to match the fragmented ‘snacking’ times. This would suggest the news gap might be shrinking as the current process of journalistic audience orientation becomes institutionalised (Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc Citation2018).

Keightley and Downey made a call “to pay attention to both the temporality of the news and audience temporalities and their interplay” (Citation2018, 106). We argue that push notifications are a channel used by news organisations to access news audiences directly and extend the time when they consume news. To support our argument, this study investigates the temporal patterns of push notification in mobile devices by Northwestern European news oganisations and whether those patterns match the identified patterns of mobile news consumption. The first research question focuses on these patterns:

RQ1: What are the times in which news organisations send push notifications to their mobile audiences?

Allowing personalisation on temporal aspects or not show who has control over the rhythms and rituals of mobile news consumption. If news organisations try to accommodate the patterns of audience consumption, we can assume push notification services should offer temporal personalisation features. The absence of these features may point to an attempt to impose the temporal framework that news organisations consider relevant. Our second research question focuses on personalisation features:

RQ2: What are the temporal personalisation options that news organisations offer in their push notifications services?

Mobile news consumption is contingent on national and cultural context (Westlund Citation2010) and different news organisations address their audiences differently. This means we have reasons to believe there are inherent differences in the distribution patterns of push notifications according to country and outlet type. However, the overarching temporalities of push notifications and the relative proximity of our countries might reveal a more unified practice. Our third research question investigates the study’s comparative aspect:

RQ3: How do news organisations compare in their use of push notification according to country, mode, and type of outlet?

Methods

Pilot Study

A pilot study was carried out in late 2017/early 2018 to determine the extent to which it was possible to gather and analyse the notifications. The research gap in this area meant there was much trial and error in setting up the tools to ensure the correct apps and settings were in place to harvest the notifications, making the pilot an invaluable stage. The pilot period lasted 4 months, with various tweaks throughout, and led to a number of changes for the second data collection: (i) when opening the app and checking the options, ensuring that only the default content settings in each news app were used for harvesting the notifications; (ii) changes in how the data was exported to ensure no issues with the multiple language characters present; (iii) changes in the sample countries and outlets. It also provided an estimate for the size of the dataset and allowed some tentative areas of interest to emerge, which helped shape the main study’s research design.

Sample and Context

Once the sample and collection method were refined, data collection began in October 2018 until April 2019. However, to avoid seasonal interference because of the holiday period, we decided the analysis would be limited to the first 3 months of 2019, from January 1 to March 31, 2019. This does not eliminate all seasonality concerns but was a necessary compromise. The nine countries were chosen for relative geographic and cultural proximity in Northwestern Europe. Alongside geographic proximity, we also chose these countries because push notifications are relatively popular in all: in another study, more than 10% of audiences in all our included countries claimed to have received a notification in the previous week (Newman et al. Citation2018).

lists each country and outlet by mode (legacy print brand, broadcast, online-only), and distinguishes between commercial outlets and public service broadcasters. These distinctions help delineate the sample and find commonalities between the outlets. The starting point for the selection of outlets within each country was the 2018 Reuters Digital News Report and its country-level results for “top brands: online,” identifying the most popular outlets. The aim was to have four outlets from each country: ideally this would be the four most popular online brands based on the Digital News Report data, but this was not always possible as (a) not all brands had news apps; and (b) not all apps use push notifications. Therefore, we chose the top four outlets in the list of popular brands that met our selection criteria. There are two countries in which only three outlets are used: first, the United Kingdom, in which there was no fourth brand deemed suitable. For example, the MailOnline/DailyMail outlet is popular but its app makes scant use of notifications (discovered during the pilot period) so would have skewed the sample, while other known brands such as the Daily Telegraph did not use alerts. Therefore, we stuck with the three most popular UK outlets: the BBC, Guardian, and Sky News. In Sweden, the pilot period and research design included the SVT public broadcaster, but a technical issue meant the notifications were not saved until near the end of the sample, so we had to exclude it from the study. A similar technical issue was identified with Norway’s VG which was unfortunate given it is the country’s most popular online brand; this was identified early in the process and a fourth replacement was used (Aftenposten).

Table 1. The 34 outlets and nine countries under study.

These issues demonstrate some of the pitfalls and limitations of such an exploratory project. Moreover, the variable and ephemeral nature of digital news is a challenge which most content analyses on digital news must address (see Karlsson and Sjøvaag Citation2016). Thus, we recognise that there can be no certainty that the content captured fully replicates the content received by other users with different devices, operating systems, app versions, or location-based settings. Furthermore, our data are based on free versions of the apps: subscribers may receive different options or additional notification content. It is, therefore, crucial to note that our empirical material comprises all the notifications we captured, but does not necessarily replicate what all users of these apps experienced during the same period.

Data Collection and Analysis

All 34 apps were downloaded via the Google Play store on an Android device (LG G3) located in Dublin, Ireland. When the apps were first opened and the settings reviewed, the available customisation options were audited and noted; attention was focussed on the temporal-based features, such as whether there were hours during which alerts could be turned on or off, or options of regular bulletin-type alerts at certain hours/certain days. None of the apps were adjusted in terms of which notification content to receive: the only changes were to accept alerts when prompted, or to turn the main “news” option on if the default was off. Another app, Notification Saver Pro, allowed saving and exporting all the push notifications to a spreadsheet. The database is limited to the alert’s text (and associated data such as timestamp) as it was not possible to save rich media, such as images, embedded in the notification. We collected 7092 push notifications, with the outlet, date, timestamp, and text all recorded.

Once exported, the database was refined and elaborated on to include additional assets for each notification (e.g., country, type and mode), while edits were also made such as adjusting the timestamp where needed to accurately display the time the notification was sent from its original country. For analytical purposes, it made sense to split the hours of the day into segments: (i) Overnight: 1am–6am; (ii) Morning commute: 6am–9am; (iii) Late morning: 9am–12pm; (iv) Lunchtime: 12pm − 2pm; (v) Late afternoon: 2pm–4pm; (vi) Evening commute: 4pm − 7pm; (vii) Late evening/night-time: 7pm–1am. This grouping allowed for a more conducive analysis given the study’s emphasis on times of day, rather than the specifics of each hour.

Results and Discussion

Time of Day for Push Notifications

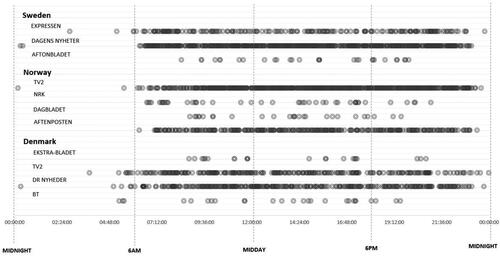

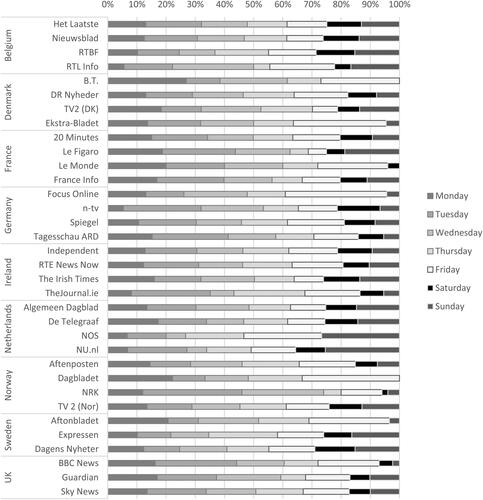

Our first research question addressed the times at which news organisations send push notifications to their mobile audiences. The first temporal distinction functioned as an important starting point, exploring the difference in usage patterns between the traditional working week and weekends. shows how, among all outlets, there was an even spread throughout the week, with a dip at weekends. Some outlets did not send a single notification during Saturday or Sunday (BT in Denmark, Dagbladet in Norway – both had low usage overall), while the weekend was less than 10% of output for Ekstra-Bladet (Denmark), Le Monde (France), Focus Online (Germany), NRK (Norway), Aftonbladet (Sweden), and BBC (UK). Conversely, weekends comprised more than 25% of output for 11 outlets. We typically see variety between organisations within each country, but there is one strong national-level/regional pattern: all four Dutch outlets, and three out of four Belgian outlets use notifications at a relatively high level at weekends.

Figure 1. The breakdown of notifications sent by each outlet by day of the week, highlighting the distinction between weekdays and weekends.

This daily breakdown suggests two things: there is day-to-day fluctuation in daily usage during the week, indicating no hard rules regarding the same number of notifications outlets send each day. Second, it highlights variation between organisations and, from a temporal consideration, indicates how some outlets may try to capitalise on weekend “down time.” We interpret this as an attempt to attract readers when they have more time to spend on their phones without the distractions of the work/school routines, while others, whether strategicly or incidentally, do not target and alert readers during this traditionally quieter time.

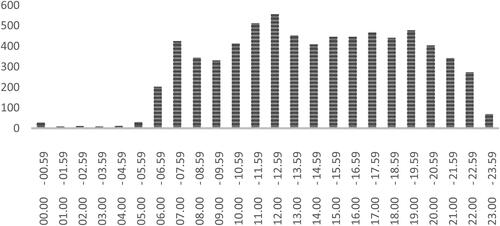

When looking at all outlets across 24 h of the day, there is scant use overnight, with showing 12pm–1pm as the most popular for push notifications among all 34 outlets. This midday hour is among the peaks identified by Read (Citation2017), alongside 4pm–5pm and 6pm–7pm hours also previously highlighted, but the key finding here is how activity is occurring throughout the day which may align with the frequent, brief cheques spread out over the day (Molyneux Citation2018).

Figure 2. The number of notifications, from all 34 outlets, sent each hour, showing relatively steady activity throughout the daytime hours.

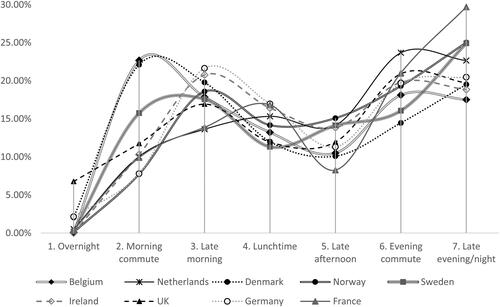

Grouping the hours of the day into segments allows for a clearer comparative picture, illustrated in . When grouped into seven segments, and highlighted by country, we see broadly similar patterns, with activity spikes in all countries during the morning commute following a typically quiet overnight period (the United Kingdom and Germany are the only countries with any notable overnight activity). Push notification activity in all countries apart from Belgium and Denmark continues to increase into the late morning, typically followed by a dip into lunchtime and the late afternoon (apart from in France and Netherlands where activity levels continue to increase into lunchtime). Following a late-afternoon dip, activity in all nine countries then spikes again, with strong usage of notifications during the evening commute and the late evening. It is worth noting that in the Scandinavian countries the spike starts earlier showing how the national context has an impact on news consumption patterns.

Figure 3. The fluctuation in each country by segment of the day, based on the percentage of each outlet’s output.

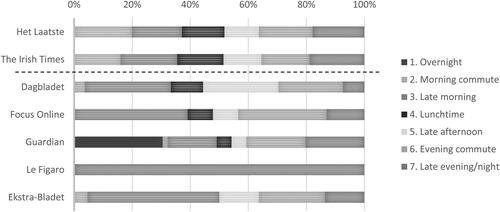

The country patterns are helpful for national comparison and it is also useful to remember the individual activity within each news organisation which varies within country. shows some of this variation: Het Laatste (Belgium) and The Irish Times (Ireland) both show the typical pattern outlined above, but Ekstra-Bladet (Denmark); Le Figaro (France); Focus Online (Germany); Guardian (UK); and Dagbladet (Norway) are all examples of divergence from this pattern. What is most notable is that those whose temporal patterns are atypical are among the same organisations which do not use push notifications heavily. This suggests that the outlets which have incorporated notifications as a regular daily routine have established similar distribution patterns that are replicated both intra-organisational and transnational.

Figure 4. The time segments notifications are sent at from selected outlets. Het Laatste and The Irish Times indicate the typical temporal pattern, while the others are more atypical.

The notifications’ content is beyond this study’s scope, but there is one outlet worth highlighting at this point: Le Figaro. Although 16 is a small number of alerts over the 90 days, it reveals a lot about the organisation’s strategy. All 16 notifications were sent between 7pm and 7.40pm on weekdays, and all contained the same text: “Discover the most-read articles of the day.” This replication of the same notification around the same time indicates a clear strategy, to nudge users in the evening and direct them towards the Le Figaro app. However, it was not an everyday occurrence and appears more sporadic in that regard, perhaps acting as an occasional nudge rather than anything more structured or forceful. Elsewhere, the temporal patterns do not appear to be tied to the format or mode of the outlets with little variation: the two online-only outlets have more activity in the latter part of the day.

To give further insight into the variations evident within countries, the strip chart in uses Sweden, Norway and Denmark to illustrate the time of day at which each notification was sent, presenting an overall visualisation of the density and hotspots throughout the day among these 11 outlets. For Dagens Nyheter, a Swedish daily, there is a heavy stream of activity between 6am and 11pm, a pattern mirrored by Aftenposten, a Norwegian afternoon paper and the Norwegian public broadcast NRK. The traditional timelines of distribution of their analogue media does not seem to be replicated in the notification distribution. Even among the outlets that use notifications more lightly, they are generally well-scattered throughout the day, but with some notable clusters, such as NRK sending notifications at around 7.30am or Ekstra-Bladet at around 5pm.

Personalisation Options and Temporal Settings

The second research question enquired about temporal personalisation options for push notifications as some outlets offered customisation settings within the apps to enhance user experience. Our audit of all apps allowed us to record the temporal options offered to users, rather than content-specific options. As with the general usage patterns, significant variation existed between outlets, but three patterns relating to temporality were identified: quiet modes, breaking news, and digests. First, some apps provided the opportunity to have explicit quiet times, typically overnight, but some allowed users to specify the exact time for sound and vibrations to be turned off (France Info, Spiegel in Germany, Focus Online in Germany, Aftenposten in Norway). Both De Telegraaf and Nu.nl offered “night modes” relating to visuals, inverting the app’s colour to be darker. In one version of the app, Dagens Nyheter in Sweden offered a “quiet time” option, but this feature was seemingly later removed. These options seem to acknowledge that notifications should not be too pervasive and intrusive, and there are times when audiences do not want to be disturbed, regardless of the notification’s content. Also, by allowing users to set the exact hours themselves, news outlets are recognising individuals’ own routines and granting them control.

Second, there is an inherent stress on immediacy built into the notion of breaking news, and many apps still draw on this immediacy element as the basis for notifications. The most common term was a general, catch-all “news” word (e.g., RTL News, RTBF, and Het Laatste in Belgium; Le Figaro in France; NOS and Algemeen Dagblad in Netherlands; TV2 and NRK in Norway; Aftonbladet and Dagens Nyheter in Sweden). Elsewhere, distinctions between news and breaking news were sometimes evident: RTÉ in Ireland has the option of both “Breaking News” and “News”; Germany’s Spiegel has options for “Breaking News” and “Important News”; DR in Denmark extricates “Breaking News” and “Top News Story.” For some, such as The Journal (Ireland) and Ekstra-Bladet (Denmark), “breaking news” is effectively the only option when turning push notifications on or off, suggesting alerts are ultimately a proxy for news that warrants immediate dissemination. Others do not ascribe any descriptive detail to a simple on/off notification setting (e.g., The Irish Times and Independent in Ireland; Dagbladet in Norway; BBC and Sky News in the United Kingdom) which may grant outlets more flexibility with what they push. This ultimately establishes two categories of news: (i) what is immediate, and (ii) what is perceived by newsworkers as most relevant, the latter category of which is deemed worthy enough to interrupt a day, even if there is no inherent immediacy.

The third pattern relates to established structures and how notifications are regularised with the aim of being incorporated into users’ daily rhythms of news consumption. This was evident in options that packaged the news for audiences at set times of the day and directed them to organisations’ proprietary platforms: for example, Le Figaro, highlighting its print background, offered a “tomorrow in Le Figaro” each night; TV2 in Denmark offered “Today’s overview”; Spiegel Daily in Germany had an evening update, NRK in Norway’s “morning summary”; and DR in Denmark had options for a 6.30am weekday/8.30am weekend daily briefing, five important updates at midday on weekdays, five important updates at 4pm on weekdays, and today’s most important stories at 9.30pm on weekdays. It makes clear to the user what time and days these notification updates will arrive, and these options serve as a reminder of how news, and news dissemination, remain aligned with routines and temporal rhythms prevailing in the freeflowing digital news space. Most of these additional notifications were not included in this sample as the default app settings had them turned off, but the options available show a willingness to allow audiences partial control over what and when content from news apps appears on their lockscreen.

Variation Between Countries and Outlets

The third research question asked about the comparison between countries, type/mode of news organisations. As demonstrated thus far, there are some variations identified within and between countries, and gives an overview of the frequency patterns across the nine countries.

Table 2. The frequency patterns of each outlet.

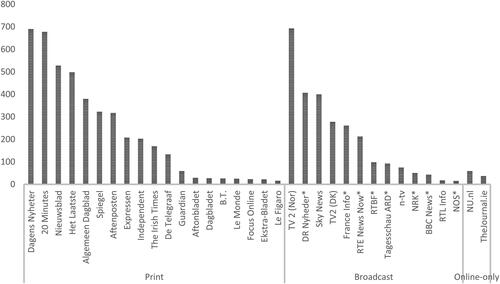

When looking at the total output of notifications from the 34 outlets, the variation is sizeable, from just 15 at NOS (Netherlands), to 693 at TV2 (Norway), with a mean use of 208 notifications over the 90 days, or 2.3 per day. Most countries appear to have one or two organisations which frequently use notifications, and then some organisations which use them much more lightly, suggesting no clear national patterns. Comparing outlets by mode (), we can see that the two online-only news outlets in the sample (NU.nl in the Netherlands, and TheJournal.ie in Ireland) are among the lowest users of push notifications. This suggests that, despite their association with networked communication, push notifications are not necessarily an intrinsic part of the digital-native output. We can also see that print brands are slightly heavier users than broadcast, but again, the difference appears modest. also indicates the distinction between commercial outlets and public service broadcasters; overall, commercial outlets are heavier users – perhaps indicating that notifications may be associated with a market-driven logic – but this is not universal.

Figure 6. The number of notifications sent by the outlets, categorised by mode. Public service broadcasters are marked with *.

The highest number of notifications sent by any outlet on an individual day was 20 (TV2 in Norway and Dagens Nyheter in Sweden), with 18 sent by Denmark’s TV2, suggesting an overall culture of heavy notification use among certain Nordic outlets. Four outlets sent a notification on every single day of the 90-day sample (Nieuwsblad in Belgium, TV2 in Norway, DR in Denmark, and 20 Minutes in France), while Sky News (United Kingdom) and Het Laatste (Belgium) had just one day without notifications. For these organisations, this suggests that notifications form a crucial part of the daily output, incorporated into the daily rhythm of news production and dissemination. For outlets at the other end of usage patterns, push notifications appear to play only a minor, sporadic role: NOS (Netherlands) only sent notifications on 14/90 days, with similar patterns from Le Figaro in France (16/90), RTL Info in Belgium (18/90 days), and Ekstra-Bladet in Denmark (19/90). Whether this light usage is strategic or incidental is impossible to tell from this data, but it illustrates the divergence in usage patterns both across Northwestern Europe and within individual countries.

Conclusion

The results show that mobile push notifications are a remarkably consistent part of news distribution channels among the European outlets studied. More concretely, three major conclusions emerge. First, news outlets try to gain access and attract audience attention throughout the day, as well as at key moments such as first thing in the morning from 7am, which is when the notifications typically start coming in. In Newman and colleagues’ (2019) proposition of four key “news moments,” it appears that push notifications fit most closely with the “updated” and “intercepted” categories. Although there were variations identified with specific outlets, the broad pattern suggests that news outlets are seeking to both integrate with, and disrupt, the audience’s activity. This implies that push notifications generally follow a hybrid temporal distribution that combines some timely spikes by targeting users during downtime, while commuting or in the evening, but – crucially – still spread notifications throughout the day as outlets maintaining activity while users are typically at work or in education. These notifications during “low consumption time” suggest that outlets are hoping to attract attention and capitalise on users’ “checking cycles” (Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer Citation2020) and their audience’s existence in an “ambient news” environment (Hermida Citation2010), and to embed themselves as part of the overall perpetual connectivity afforded by smartphone devices.

Second, the diversity of customisable temporal features offered by news outlets follow little consensus. The available options facilitate individual users’ “explicitly registered and/or implicitly determined preferences” (Thurman and Schifferes Citation2012, 776). It seems notifications can capture both the explicit and implicit: certain settings facilitate explicit preferences, while most outlets maintain temporal control over notifications, expecting their judgement of what is important and appropriate to align with audience demands. Little agency is given to the audience. This may be informed by data on audience consumption patterns or it may be more driven by newsroom-centric decision-making and practices with little awareness of user behaviours.

Third, there are similar patterns across national settings in which news outlets have varying degrees in push notifications use. Within each of the nine countries surveyed, the frequency of notifications demonstrated how typically there were one or two dominant outlets who use push notifications daily, while the others used them less frequently. Instead, we see more distinctions among mode/type of news outlets: commercial outlets tend to use push notifications more, which suggests that notifications follow a more market-focused logic, while legacy print outlets use more push notifications while online-only do not. This suggests that print outlets – which have typically lost more audience in recent decades – use push notifications to regain contact with the audience. While we have not explored notification content, examples like Le Figaro show that notifications invite users to check the news at the outlet’s proprietary platforms.

Following Keightley and Downey’s call to analyse the “interplay” between the temporality of news and the audience temporality (Citation2018, 106), this study contributes to journalism studies with an original insight into how news organisations are using push notifications and how this might relate to audience behaviour and activity. It offers the first empirical overview of push notification use across Northwestern European news outlets with a novel method for data collection. A focus on the temporality of push notifications also provides insights in the newsroom strategies (or lack of). Those outlets using notifications actively and consistently have incorporated them as part of the daily news output, whereas others use them more intermittently. Among outlets sending more notifications, the temporal patterns are surprisingly consistent, but those using notifications less frequently are less consistent in their distribution patterns. This suggests that increased use of notification is supported by some sort of planned strategy. In general, overnight notifications were rare, pointing to structural factors influencing push notification distribution. On the one hand, notifications are not necessarily driven by news events themselves and the exact moment of occurrence; rather, there is a prioritising and centring of when audiences are active, reinforcing the audience orientation. This is a structural disruption of traditional news selection processes as the apparent selection of personalised news is based on audience data. On the other hand, news production practicalities and staffing are central as, despite the potential of 24-hour news cycles, many newsrooms will still only be lightly staffed – if at all – overnight, thus potentially indicating that the sending of notifications is directly tied to the hours of newsroom activity. Yet given the possibility of automation for sending notifications, the avoidance of overnight alerts could also point to a strategic choice. Similarly, the general decline in notification use at weekends suggests an inherent routinisation to the notification dissemination: this could potentially be accounted for by a smaller newsroom staffing and general news slow-down at weekends, or perhaps news organisations taking a conscious decision to curtail the alerts during these 2 days.

This leads on to one major limitation of our empirical material: we cannot determine whether the patterns identified in this study are strategic or incidental. While outlets like the New York Times build staffing and strategies around push notifications (Brown Citation2018), we cannot assume that such resources are available to smaller and local European newsrooms, or that notifications are even prioritised in such a manner. Elsewhere, it should be noted that the countries studied here are not the same regions from which secondary data on audience usage patterns was obtained in our review of the literature, so there may be national variations which could provide further insight into mobile use at a country-by-country level.

We believe future research should pursue four major areas. First, special attention should be cast on the alerts through content analysis on data such as that used here: what issues and events are being pushed by news organisations, and the extent to which they remain committed to pushing alerts primarily about breaking news or whether there is a focus on promoting their own exclusive, non-breaking content in an effort to attract readers to their apps. Second, direct input from those involved in sending notifications and how the alerts fit with overall digital newsroom strategies. Third, there is the need to explore the mobile news eco-system more broadly, and the updates provided by aggregators such as Apple News and Google News. These have received scant scholarly attention thus far yet are an integral part of many users’ mobile news experiences that should be expanded beyond the Northwestern European context. And finally, we should investigate how news consumers navigate push notifications as a part of their daily practices. If this is part of the ways in which news organisations aim to regain the societal and commercial relevance of journalism, scholars should learn more about the dynamics that guide push notification use.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ananny, M. 2016. “Networked News Time: How Slow—or Fast—Do Publics Need News to Be?” Digital Journalism 4 (4): 414–431.

- Benton, J. 2011, November 18. “More Evidence That Different Devices Fuel News Consumption at Different Times.” Nieman Lab. Accessed 15 August 2019. https://www.niemanlab.org/2011/11/more-evidence-that-different-devices-fuel-newsconsumption-at-different-times/

- Boczkowski, P. J., and E. Mitchelstein. 2013. The News Gap: When the Information Preferences of the Media and the Public Diverge. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Bødker, H. 2017. “The Time(s) of News Websites.” In The Routledge Companion to Digital Journalism Studies, edited by Franklin B. and S. Eldridge (II), 55–63.New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bødker, H., and N. Brügger. 2018. “The Shifting Temporalities of Online News: The Guardian’s Website from 1996 to 2015.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 19 (1): 56–74.

- Brown, P. 2017. Pushed Beyond Breaking: US Newsrooms Use Mobile Alerts to Define Their Brand. New York, NY: The Tow Center for Digital Journalism.

- Brown, P. 2018. Pushed Even Further: US Newsrooms View Mobile Alerts as a Standalone Platform. New York, NY: The Tow Center for Digital Journalism.

- Carlson, M. 2016. “Metajournalistic Discourse and the Meanings of Journalism: Definitional Control, Boundary Work, and Legitimation.” Communication Theory 26 (4): 349–368.

- Castells, M., M. Fernández-Ardèvol, J. L. Qiu, and A. Sey. 2007. Mobile Communication and Society: A Global Perspective. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Costera Meijer, I., and T. Groot Kormelink. 2015. “Checking, Sharing, Clicking and Linking: Changing Patterns of News Use between 2004 and 2014.” Digital Journalism 3 (5): 664–679.

- Duffy, A. R. Ling, N. Kim, E. Tandoc, and O. Westlund. 2020. “News_ Mobiles, Mobilities, and Their Meeting Points.” Digital Journalism 8 (1): 1–14.

- Elliott, A., and J. Urry. 2010. Mobile Lives. London: Routledge.

- Ferrer-Conill, R., and E. C. Tandoc. 2018. “The Audience-Oriented Editor: Making Sense of the Audience in the Newsroom.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 436–453.

- Fidalgo, A. 2009. “Pushed News: When the News Comes to the Cellphone.” Brazilian Journalism Research 5 (2): 113–124.

- Groot Kormelink, T., and I. Costera Meijer. 2020. “A User Perspective on Time Spent: Temporal Experiences of Everyday News Use.” Journalism Studies 21 (2): 271–286.

- Haim, M., A. Graefe, and H.-B. Brosius. 2018. “Burst of the Filter Bubble? Effects of Personalisation on the Diversity of Google News.” Digital Journalism 6 (3): 330–343.

- Heinderyckx, F. 2011. “Striving for Noiseless Journalism.” In Critical Perspectives on the European Mediasphere, edited by N. Carpentier, H. Nieminen, and P. Pruulmann-Venerfeldt, 109–120. Ljubljana, Slovenia: Faculty of Social Sciences/Založba FDV.

- Hermida, A. 2010. “Twittering the News: The Emergence of Ambient Journalism.” Journalism Practice 4 (3): 297–308.

- Karlsson, M. 2011. “The Immediacy of Online News, the Visibility of Journalistic Processes and a Restructuring of Journalistic Authority.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 12 (3): 279–295.

- Karlsson, M., and H. Sjøvaag. 2016. “Content Analysis and Online News.” Digital Journalism 4 (1): 177–192.

- Keightley, E., and J. Downey. 2018. “The Intermediate Time of News Consumption.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 19 (1): 93–110.

- Lavie, T., M. Sela, I. Oppenheim, O. Inbar, and J. Meyer. 2010. “User Attitudes towards News Content Personalisation.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 68 (8): 483–495.

- Lewis, J., S. Cushion, and J. Thomas. 2005. “Immediacy, Convenience or Engagement? An Analysis of 24-Hour News Channels in the UK.” Journalism Studies 6 (4): 461–477.

- Ling, R., L. Fortunati, G. Goggin, S. S. Lim, and Y. Li, eds. 2020. The Oxford Handbook of Mobile Communication and Society. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- López-García, X., A. Silva-Rodríguez, Á.-A. Vizoso-García, O. Westlund, and J. Canavilhas. 2019. “Mobile Journalism: Systematic Literature Review.” Comunicar 27 (59): 9–18.

- Molyneux, L. 2018. “Mobile News Consumption: A Habit of Snacking.” Digital Journalism 6 (5): 634–650.

- Nelson, J. 2020. “The Persistence of the Popular in Mobile News Consumption.” Digital Journalism 8 (1): 87–102.

- Newman, N. 2016. News Alerts and the Battle for the Lockscreen. Oxford, UK: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, and R. K. Nielsen. 2018. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018. Oxford, UK: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, and R. K. Nielsen. 2019. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019. Oxford, UK: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Nyre, L., S. Bjørnestad, B. Tessem, and K. V. Øie. 2012. “Locative Journalism: Designing a Location-Dependent News Medium for Smartphones.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 18 (3): 297–314.

- Peters, C. 2012. “Journalism to Go: The Changing Spaces of News Consumption.” Journalism Studies 13 (5–6): 695–705.

- Peters, C. 2015. “Introduction: The Places and Spaces of News Audiences.” Journalism Studies 16 (1): 1–11.

- Read, M. 2017, July 31. “Analysis: The Reality of Online News Consumption.” Mediatel. Accessed 15 August 2019. https://mediatel.co.uk/newsline/2017/07/31/analysis-the-reality-of-online-news-consumption

- Rom, S., and Z. Reich. 2020. “Between the Technological Hare and the Journalistic Tortoise: Minimization of Knowledge Claims in Online News Flashes.” Journalism 21 (1): 54–72.

- Schmitz Weiss, A. 2013. “Exploring News Apps and Location-Based Services on the Smartphone.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 90 (3): 435–456.

- Schrøder, K. C. 2015. “News Media Old and New: Fluctuating Audiences, News Repertoires and Locations of Consumption.” Journalism Studies 16 (1): 60–78.

- Sheller, M. 2015. “News Now: Interface, Ambience, Flow, and the Disruptive Spatiotemporalities of Mobile News Media.” Journalism Studies 16 (1): 12–26.

- Steensen, S., R. Ferrer-Conill, and C. Peters. 2020. “(Against a) Theory of Audience Engagement with the News.” Journalism Studies. Advance online publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2020.1788414.

- Stroud, N. J., C. Peacock, and A. L. Curry. 2020. “The Effects of Mobile Push Notifications on News Consumption and Learning.” Digital Journalism 8 (1): 32–48.

- Tenenboim-Weinblatt, K. 2014. “Counting Time: Journalism and the Temporal Resource.” In Journalism and Memory, edited by B. Zelizer and K. Tenenboim-Weinblatt, 97–112. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tenenboim-Weinblatt, K., and M. Neiger. 2018. “Temporal Affordances in the News.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 19 (1): 37–55.

- Thurman, N. 2018. “Newspaper Consumption in the Mobile Age: Re-Assessing Multiplatform Performance and Market Share Using “Time-Spent”.” Journalism Studies 19 (10): 1409–1429.

- Thurman, N., and S. Schifferes. 2012. “The Future of Personalisation at News Websites: Lessons from a Longitudinal Study.” Journalism Studies 13 (5–6): 775–790.

- Van Damme, K., C. Courtois, K. Verbrugge, and L. De Marez. 2015. “What’s APPening to News? A Mixed-Method Audience-Centred Study on Mobile News Consumption.” Mobile Media & Communication 3 (2): 196–213.

- Westlund, O. 2010. “New (s) Functions for the Mobile: A Cross-Cultural Study.” New Media & Society 12 (1): 91–108.

- Westlund, O. 2013. “Mobile News: A Review and Model of Journalism in an Age of Mobile Media.” Digital Journalism 1 (1): 6–26.

- Westlund, O. 2015. “News Consumption in an Age of Mobile Media: Patterns, People, Place, and Participation.” Mobile Media & Communication 3 (2): 151–159.

- Westlund, O., and M. Ekström. 2018. “News and Participation through and beyond Proprietary Platforms in an Age of Social Media.” Media and Communication 6 (4): 1–10.

- Westlund, O., and M. A. Färdigh. 2011. “Displacing and Complementing Effects of News Sites on Newspapers 1998–2009.” International Journal on Media Management 13 (3): 177–194.

- Westlund, O., and S. Quinn. 2018. “Mobile Journalism and MoJos.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. Accessed 24 July 2019. https://oxfordre.com/communication/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-841

- Wheatley, D., and J. O’Sullivan. 2017. “Pressure to Publish or Saving for Print?” Digital Journalism 5 (8): 965–985.

- Xu, J., C. Forman, J. B. Kim, and K. Van Ittersum. 2014. “News Media Channels: Complements or Substitutes? Evidence from Mobile Phone Usage.” Journal of Marketing 78 (4): 97–112.

- Zamith, R. 2018. “Quantified Audiences in News Production: A Synthesis and Research Agenda.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 418–435.

- Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J., D. Trilling, J. Möller, B. Bodó, C. H. de Vreese, and N. Helberger. 2016. “Should We Worry about Filter Bubbles?” Internet Policy Review 5 (1): 1–16.