Abstract

The consumption of news increasingly takes place in the context of social media, where users can personalize their repertoire of news through personal news curation practices such as following a journalistic outlet on Twitter or blocking news content from a Facebook friend. This article examines the prevalence and predictors of curation practices that have the potential to boost or limit social media news exposure. Results from a representative online survey distributed across thirty-six countries demonstrate that more than half of all news users on social media engage in such practices. Significant predictors of news-boosting curation are news interest and the willingness to engage in other news-related activities on social media. News-limiting practices on social media are linked to general news avoidance and, in the case of the US, political extremism, which might decrease the chances of incidental news exposure. News-boosting and news-limiting curation practices relate to a wider and more diverse repertoire of news sources online. Personal news curation practices can be conceptualized as forms of news engagement that have the potential to complement or counteract algorithmic news selection or partisan selective exposure, yet, these practices can also solidify existing divides in news use related to interest and avoidance.

Over the past two decades, social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have become an integral part of online news distribution and consumption. In response to calls for theoretical innovation following this development (e.g. Bennett and Iyengar Citation2008), Thorson and Wells (Citation2016) arrived at the concept of “curated flows” to conceptualize social media news exposure. They argue that on social media platforms processes of “curation”—the production, selection, filtering, annotation or framing of content—are undertaken by a variety of actors, not only conventional newsmakers and gatekeepers such as journalists, but also by other actors such as politicians, online social contacts, algorithms, and individual users.

This article focuses on the latter form of social media news curation that has been given scant attention and is intricately linked to the affordance of each digital platform: the personal curation practices of users. Users play a decisive role in customizing their information repertoires on social media. Users can subscribe to news organizations or hide user accounts, topics, and pages in their news feed and thereby have a certain kind of leverage in determining its composition.

Theoretically speaking, these curatorial practices are particularly striking in that they facilitate an “in-between of news exposure” (Stroud, Peacock, and Curry Citation2020, 1) situated between intentional and incidental exposure that can result in a certain “automated serendipity” (Fletcher and Nielsen Citation2018a, 977). Curating the news content in one’s social news feed is in some ways intentional, purposeful, and even selective: users decide to follow a news outlet or change their settings so that they might see less news. It is in some way incidental since users have no final control of if, where, and when this content is actually displayed in their newsfeed due to journalists’ gatekeeping practices and algorithmic filtering. Acts of personal news curation on social media have the potential to balance, counteract, or complement other mechanisms of content curation such as algorithmic filtering or social curation. Exploring these curatorial acts further can help us in disentangling the complexities inherent in social media news consumption especially in the context of the strong assumptions often made on the impact of such media use in terms of polarization and a lack of diversity (Zuiderveen Borgesius et al. Citation2016).

After summarizing Thorson and Wells’ (Citation2016) concept of personal curation and the characteristics of social media news use and discussing previous research on customization and selective exposure, I analyze the prevalence of and predictors for these practices relying on representative data from the 2017 Reuters Institute Digital News Survey that covered thirty-six countries (n > 2000 per country). This dataset includes information on general news consumption patterns and key demographic data that can be included in models to predict news-boosting and news-limiting curation. Multilevel logistic regression analyses indicate that predictors of news-boosting curation include a higher level of news interest, a wide repertoire of news sources online, and the willingness to engage in activities around news consumption such as news-sharing or commenting. News-limiting practices are linked to general news avoidance and, in the case of the US, a more extreme political ideology. Users who report that they engage in news-boosting and news-limiting activities also report a wider and more diverse repertoire of online sources. The insights into the practices and predictors of personal news curation displayed in this article can hopefully operate as another component in the development of our understanding of the dynamics of personalization and selective exposure in the context of social media news use.

Curated News Flows on Social Media

In the art world, curators have conventionally functioned as gatekeepers who recognize and nurture emerging trends. However, curation as a practice and as a concept steeped in ambiguity has long transcended museums and has drifted into the creative and information industries (Villi, Moisander, and Joy Citation2012). In an age of information abundance, efficient and effective selection has become one of the most viable business models for digital environments; search engines represent a particularly successful example of automated curation. Human-led aggregating, sharing, ranking, tagging, reposting, juxtaposing, and critiquing of content on a variety of platforms and validating this content through one’s media brand has also been proclaimed as a saving grace for legacy media’s online business opportunities (Clark and Aufderheide Citation2009). Consequently, Thorson and Wells (Citation2016, 310) refer to curation as “the fundamental action of our media environment”. They conceptualize additional sets of actors beyond journalists that shape individual publics in personalized news environments such as social media as a) strategic curators (for example, companies or politicians) who can now communicate directly to specific publics, b) social curators (such as contacts on the platform) that render news accessible by sharing, commenting or rating content in their digital social circle and c) algorithmic curation that builds upon the behavior of those human actors. Social media news curation practices carried out by strategic curators (i.e. Kreiss Citation2016), journalists (i.e. Ju et al. Citation2014), social contacts (i.e. Kaiser, Keller, and Kleinen-von Königslöw Citation2018), and those facilitated by algorithmic filtering (i.e. Zuiderveen Borgesius et al. Citation2016) have all been discussed extensively in recent communication research.

Another fundamental manifestation of news flows in personalized media environments, d) acts of personal news curation (Thorson and Wells Citation2016), have received less scholarly attention. For example, research on user preferences for news selection online covers algorithmic, social, and journalistic curation (Thurman et al. Citation2019; Fletcher and Nielsen Citation2019) but has not yet explored the user agency. In their use of social media, individual users can modify their information environment by including and excluding preferred sources, topics, or opinions. They also possess the agency to adjust various parameters of the news flows curated by other curatorial actors, either intentionally when following journalists, managing their own feed settings (for example, by prioritizing new messages or blocking social contacts) or less explicitly through the information they add to their social media profile and their overall behavior on the platform that allows for algorithmic inferences. This article focuses on the intentional acts of news curation and customization on social media platforms. While the specific software architecture differs from a social media platform to another, changes in the newsfeed can be achieved intentionally by either manipulating the network an individual is connected to (adding, following, or deleting and blocking users or an organization) or changing settings so that more or less content will be displayed from certain accounts. Depending on the affordances of the specific platform, two distinctive outcomes of personal news curation might be possible: Acts of personal news curation can be employed to pull in more content or to push content away. This article, therefore, distinguishes practices of curation along these two dimensions: news-limiting and news-boosting practices. Even though these practices are very distinct in their outcome, it does not necessarily mean that such acts of personal news curation are mutually exclusive.

Personal News Curation as Chance and Necessity

Selecting the news according to individual preferences has been possible and has been previously studied in a range of news environments (Donsbach Citation1991; Stroud Citation2008). But, in an age characterized by deep mediatization (Couldry and Hepp Citation2017), the amount of available and ubiquitous news content is invariably too vast to observe in its entirety, which nudges users to decide what kinds of content they wish to highlight, ignore, engage with, or remove from their news diet (Davis Citation2017).

The specific dynamics of the individualized social media news environments, where news exposure is often incidental, non-exclusive, and framed by social cues both necessitate and afford new selection possibilities (see Kümpel Citation2020a; Kümpel Citation2020b, Schmidt et al. Citation2019; Thorson and Wells Citation2016). Due to the affordances of social media platforms, the individual user is able to influence the quantity, the topics, and the political disposition of the news content they are exposed to in a novel and unique way. The personal curation of social media feeds has become a “practice of both necessity and motivation” (Davis Citation2017, 773).

Incidentiality: News exposure on social media is often not as intentional as watching a news broadcast or visiting a news outlet’s homepage. While a user just logged into Instagram to post a photograph of their evening meal they can stumble across a breaking news story posted by a contact. Due to the interplay of social and algorithmic curation, the social media news environment has been discussed as a “low choice media environment” (Bode Citation2016) where users may “encounter current affairs information when they had not been actively seeking it” (Tewksbury, Weaver, and Maddex Citation2001, 534). Incidental exposure on social media was envisioned as a means of mitigating existing gaps in news use since it might facilitate opportunities for news use, knowledge gain, and participation for citizens who would otherwise engage less or not at all with (traditional) news sources (Fletcher and Nielsen Citation2018b; Bode Citation2016; Valeriani and Vaccari Citation2016). However, an argument can also be made about social media platforms as a high choice environment (Prior Citation2007), where content preferences become more important: the chances of being exposed to and engaging with news content on social media are not balanced equally among social media users and are very much dependent on individual interests, practices of news consumption, and the algorithmic interferences that are made (Kümpel Citation2020a; Thorson Citation2020; Moeller et al. Citation2020). Acts of personal news curation can be a tool to either mitigate or increase the amount of news exposure one might have on these platforms. If a user does not follow any news organizations on Facebook and has blocked friends that share a lot of news content, stumbling into information on current events on their feed might not happen as often as it would for a person who has liked several news outlets and has interacted with such content in the past (Thorson et al. Citation2019). In addition, the platform affordances of the newsfeed architecture do not only facilitate unplanned news contact but also make it harder to receive news intentionally. Even if users follow news organizations on social media they cannot be sure if and what content journalists will post and that the content they post will be displayed in their newsfeed. Subscribing to a print newspaper or a news website’s RSS feed can result in the reasonable assumption that news will be consistently received from that outlet whereas following a news organization on Twitter has a less predictable outcome.

Sociality: In their interactions with news content on a platform by sharing or commenting, social contacts also influence which news content an individual user is exposed to. Additionally, their curation of news content can be a key criterion in determining an individual’s willingness to engage with that content (e.g. Kaiser, Keller, and Kleinen-von Königslöw Citation2018). Limiting or forging social contacts on social media can have consequences for individual news exposure. Users are able to add or block contacts so that they might be exposed to more or less news in their feeds. In contrast to other shared news environments, changing the social parameters of the news experience on social media can happen with very limited or no knowledge of the social contact. One can hide or block a user on Twitter without their knowledge but it might be more challenging to abandon a relative commenting on the evening news broadcast without them noticing.

Non-Exclusivity: Unlike a news broadcast or a newspaper edition, news content on social media is unbundled from discrete news packages with editorial framing and selection (Schmidt et al. Citation2019; Trilling Citation2019) and re-bundled together with non-news content through algorithmic selection. For example, news content on Facebook makes up only around four percent of the newsfeed and is invariably mixed with family photos and comedy videos (Zuckerberg Citation2018). Individuals watching a news broadcast or streaming a Netflix drama might receive more genre coherent content. If the algorithmically inferred mix of various content on social media does not fulfill user preferences, they are able to alter the balance by, for example, limiting or boosting news content. By curating one’s news repertoire on Twitter or Instagram individual users are able to select and filter their own “newspaper edition”, thereby becoming an editor or gatekeeper in their own right through practices of personal news curation.

Overall, the conditions of (partial) incidentiality, sociality, and non-exclusivity shape personalized news exposure and consumption on social media. Acts of personal news curation can influence how incidental, social, and exclusive news content finds its way to individuals through social media platforms. By engaging in these practices, users can determine, at least to some degree, whether or not they see news in their feed (e.g. by following a news outlet), the order in which it is presented (e.g. by changing settings to display entries from a particular account first) and its quantity (e.g. show less of this account). This is in stark difference to the amount of leverage they are able to determine through the use of a linear news broadcast or a newspaper edition.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Many scholars have found evidence that acts of news-boosting and news-limiting curation may affect the mix of content that is algorithmically selected to be displayed in a social media newsfeed. Based on the analysis of patents and press releases DeVito (Citation2017) identified nine newsfeed values that drive content selection through algorithms on Facebook. Among others, the selection appears to be based on explicit acts of personal curation such as expressed user interests or negative preferences, relationships to Facebook pages, and the prior engagement with similar content. Wells and Thorson (Citation2017) paired participants’ survey responses with measures of their Facebook use via a platform app to predict, among other variables, levels of news exposure. They found a positive influence of following civic and political pages, a potential practice of personal curation. In an experiment with a mock-up online website, Dylko et al. (Citation2017, Citation2018) demonstrated that the possibility of user-driven curation (modify the issue or ideology of news content consumed) can increase partisan selective exposure while at the same time it can also weaken the relationship between system-driven customizability (seeing only ideological content according to one’s orientation or previous behavior) and partisan selective exposure. Since partisan selective exposure is linked to political polarization (Stroud Citation2010) and, therefore, not necessarily preferable from a normative democratic standpoint, studying the prevalence and practice of user-driven personal news curation can also help us understand how the dynamics of selective exposure on social media can be minimized.

While Wells and Thorson (2017) theorized practices of personal curation and explored its relation to news interest and exposure in an exploratory sample of college students, this article intends to analyze these kinds of practices with representative samples in different countries. Furthermore, this research extends their previous work on news-boosting practices (following political/civic/news-related pages) by including news-limiting practices (for example, “unliking” an organization) and thus poses the following research question:

RQ1: How prevalent are practices of news-boosting and news-limiting curation on social media?

To understand the dynamics of personal news curation it is important to explore the antecedents of these practices. Relating to the theory of uses and gratifications and selective exposure, several possible factors come to mind: The most obvious one being a general (dis)interest in news content.

News Interest and News Avoidance

Following the audience-centered assumption that media selection is determined by individual needs and personal motivations (Ruggiero Citation2000), personal news curation can be driven by an interest or need for news, and potential gratifications can be sought and obtained. General interest in news and politics has been shown as a predictor of the probability of following political and news organizations on Facebook, a news-boosting form of personal news curation (Wells and Thorson Citation2017). Song, Jung, and Kim (Citation2017) found a negative relationship between news interest (“need for news”) and news avoidance. I, therefore, expect that users with a high level of news interest engage in more news-boosting activities.

H1: Users with a higher level of news interest are more likely to engage in news-boosting curation.

Despite the manifold availability of news content, the number of people who avoid news is increasing (Blekesaune, Elvestad, and Aalberg Citation2012), which is a potential societal problem since news use is related to political knowledge and participation (Delli Carpini and Keeter Citation1996). In their review of news avoidance, Skovsgaard and Andersen (Citation2019) differentiate between a) a lack of news exposure due to low levels of news interest and a preference for other media opportunities and b) the practice of consciously tuning out of news content due to skepticism, negative effects on their mood or feelings of news overload.

Through acts of personal news curation, personalized news environments can be intentionally changed and these practices could be related not only to (a lack of) news interest but also active avoidance of news content in general or specific sources and topics. Song, Jung, and Kim (Citation2017) found that the use of news aggregators that “screen out unwanted content, reducing the overall flow of information and making it more targeted to the end user’s interests” (1180) can reduce news avoidance related to news overload. I, therefore, assume that:

H2: Users who avoid news more frequently are more likely to engage in news-limiting curation.

By adopting the assumption that a greater need for personal curation is related to the supply of media offerings (Davis Citation2017; Song, Jung, and Kim Citation2017), I also want to explore whether or not the quantity of news sources users consume online is related to personal news curation.

Since social media represent an important source of online news (Newman et al. Citation2019), and acts of personal news curation result in the (dis)appearance of news sources in the newsfeed, one could hypothesize that personal news curation might correlate with the number of online news sources seen. News-boosting behavior could allow for larger quantities of online news sources for those who actively seek such content in their feed. Fletcher and Nielsen (Citation2018b) found that individuals who intentionally use social media intentionally for news report the highest number of online news sources than users who do not use social media for news at all or are just incidentally exposed. Acts of news curation could contribute to a larger news repertoire for individuals that use social media for news intentionally.

The relation between news-limiting practices and source quantity could be less clear-cut and related to the motivation for limiting the amount of news (sources) to which one is exposed. On the one hand, news limiting practices could be motivated by a general disinterest or dislike of news content or a preference for other content on social media (Prior Citation2007; Donsbach Citation1991). Users who already do not see and like news can curate news (sources) out of their feed because they are not interested. One the other hand, high levels of news consumption and news source quantity can also create a need for news-limiting curation. When the amount of available information exceeds the processing capacities of a user, a negative feeling of information overload can occur (Lee, Kim, and Koh Citation2016). Load adjustment strategies such as limiting the number of news sources can be a way to handle information overload (Song, Jung and Kim Citation2017). Lee, Kim, and Koh (Citation2016) found that the more attention participants paid to news through new media such as social media platforms and smartphones, the more news overload they perceived and, in addition, they found a positive relationship between the level of overload and tendencies of news avoidance or selective exposure. Curating sources out of one’s newsfeed could also be a strategy to reduce the amount of news in a feed that is full of sources. To explore this interplay further, the following RQ is posed:

RQ2: How are a) news-boosting and b) news-limiting curation related to the number of news sources consumed online?

Ideological Extremism

Through news curation practices on social media, users can not only influence the volume of news (sources) they see but they can also include or exclude users or organizations that share news that pertain to a certain political opinion or attitude. Selective exposure, the attraction to attitude-consistent information, and aversion to inconsistent information has been demonstrated for various issues and situational contexts (see Stroud Citation2008; Garrett and Stroud Citation2014).

Research by the Pew Institute (Mitchell et al. Citation2014) demonstrated that in the US, individuals that are more extreme in their political orientation (consistently conservative/liberal) engage in news-limiting behavior more often (block or unfriend someone on social media because they disagreed with something that person posted about politics) than less extreme social media users.

Wagner and Boczkowski (Citation2019) explore emotional coping strategies towards news about US President Donald Trump and describe how users unfriended or muted individuals on social media due to the distress of seeing cross-ideological content. These results seem to connect curatorial practices to debates on social media’s distortive and adverse effects concerning news diversity and polarization (Zuiderveen Borgesius et al. Citation2016). Longitudinal analyses of general media use indicate stronger evidence for partisan selective exposure leading to polarization, but some evidence supports the reverse causal direction (Stroud Citation2010). John and Dvir-Gvirsman (Citation2015) explored practices of Facebook unfriending during the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict and found such behavior more prevalent among more ideologically extreme users. Zhu, Skoric, and Shen (Citation2017) measured unfriending and the hiding of posts as selective avoidance in the context of the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement protests in 2014. In light of these findings, I hypothesize that those individuals with an extreme political position may be more prone to news-limiting practices on social media.

H3: Users with a higher level of ideological extremism are more likely to engage in news-limiting curation.

Social Media Skills and Activities

To engage in news curation practices, users need to possess the actual skills for such practices. For example, they need to know how to block other users or how to change settings to prioritize posts from preferred news accounts in their newsfeed. For other information-related activities carried out online, a digital literacy divide has been demonstrated (Hargittai and Litt Citation2013). Measuring digital literacy is a methodologically challenging process; however, previous work has found that asking people to rate their level of understanding of internet-related terms serves as a better proxy for actual digital literacy (as measured on performance tests) than measures of users’ self-perceived abilities, a proxy traditionally used (Hargittai Citation2005). While the Reuters Digital News Survey does not inquire into knowledge-related terms, it does query news-related activities on social media. Activities such as sharing or commenting on news on social media could not only be a proxy for social-media related literacy but can also be read as an active engagement with news on social media, similar to personal news curation. I anticipate, therefore, that overlaps will occur between the engagement with practices of personal news curation and the engagement with news-related activities on social media.Footnote1

H4: Users with a higher level of news-related social media activities are more likely to engage in a) news-boosting and b) news-limiting curation.

Method

Dataset

This analysis relies on data from the 2017 Reuters Institute Digital News Survey (Newman et al. Citation2017), an online survey conducted annually in thirty-six countries (n=72.920). The sample per country (n > 2000) is representative of each country’s online population aged eighteen years and older and is weighted towards targets on age, gender, and region.Footnote2 The questionnaire includes a series of items that allow for the inference of the prevalence of personal news curation practices and a full range of questions designed to discover patterns of news consumption and key demographic data that can be included in a model to predict such practices.

As discussed in previous research employing data from the Reuters Digital News Survey project (for example Fletcher and Park Citation2017) using the same questions at the same point in time across different territories allows for a comprehensive and comparative analysis through a pooled data set and conclusions can arise that transcend specific national contexts. The aim of this article is not necessarily one of a cross-country comparison but, rather, its intention is to identify a stable model beyond a single media environment and to avoid a bias toward research in the US or West European context only (Boulianne Citation2019). A drawback of the cross-sectional online panel data is that neither causation nor the views of persons without online-access can be deduced. While the latter aspect is not necessarily problematic for a paper with a focus specific on online practices, the fact that, since the Reuters Digital News Survey focuses on online news consumption, respondents who did not use news at least once a month were excluded from the survey should be noted as a limitation.

Measures

Practices of News Curation

To assess individual levels of personal curation, all survey participants that stated they had used social media for the consumption of news (between 814 and 1,819 per country, see ) were asked if they had carried out any of the following practices during the last year on any social network:

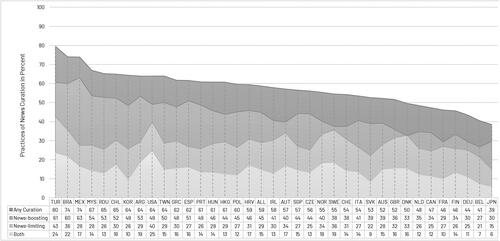

Figure 1. Prevalence of individual news curation of social media news users’ practices split by type of practice (question only posed to participants that use social media for news).

Notes. ALL = all countries combined (n = 49382), ARG = Argentina (n = 1707), AUS = Australia (n = 1125), AUT = Austria (n = 1051), BEL = Belgium (n = 1203), BRA = Brazil (n = 1770), CAN = Canada (n = 1595), CHE = Switzerland (n = 1631), CHL = Chile (n = 1802), CZE = Czech Republic (n = 1236), DEU = Germany (n = 904), DNK = Denmark (n = 990), ESP = Spain (n = 1527), FIN = Finland (n = 1013), FRA = France (n = 1230), GBR = Great Britain (n = 897), GRC = Greece (n = 1596), HKG = Hong Kong (n = 1629), HRV = Croatia (n = 1582), HUN = Hungary (n = 1574), IRL = Ireland (n = 1283), ITA = Italy (n = 1512), JPN = Japan (n = 814), KOR = Korea (n = 1204), MEX = Mexico (n = 1819), MYS = Malaysia (n = 1799), NLD = Netherlands (n = 1047), NOR = Norway (n = 1078), POL = Poland (n = 1500), PRT = Portugal (n = 1439), ROU = Romania (n = 1753), SGP = Singapore (n = 1606), SVK = Slovakia (n = 1451), SWE = Sweden (n = 1007), TUR = Turkey (n = 1702), TWN = Taiwan (n = 853), USA = USA (n = 1453).

Deleted or blocked another user or organization because of news they had posted or shared

Added, followed or became friends with a user or organization because of news items they had posted or shared

Changed their settings so that they would see more news from a user or organization

Changed their settings so that they would see less news from a user or organization.

In an explorative factor analysis these variables load significantly on one factorFootnote3 and at the same time can be conceptually distinguished between news-boosting (2, 3) and news-limiting practices (1, 4). To that effect significant correlations were found between these items (1 & 4: r = .266**; 2 & 3: r = .104**). Consequently, three binary variables were formed: overall news curation (engaging in any kind of news curation), news-boosting curation (engaging in one or both news-boosting practices), and news-limiting curation (engaging in one or both news-limiting practices).

Other Variables of Interest

All respondents were asked to provide information on their political leanings on a seven-point scale ranging from “very-left-wing” (1) to “very right-wing” (7) (M=3.84, SD = 1.480). Political extremism was measured by taking the absolute distance from the midpoint political position (1-4; M=2.12, SD = .955). News interest was measured on a five-point scale (recoded) ranging from “not at all interested” (1) to “extremely interested” (5) (M=3.87, SD = .823). Participants were also asked if they find themselves “actively trying to avoid news these days” often (recoded 4), sometimes, occasionally, or never (recoded as 1) (M=1.98, SD = .971).Footnote4 To generate data on the number of news sources consumed online participants were asked, “Which online brands have you used in the last week?” from a list of the most popular news organizations in each country (with the option to add additional brands) (M=4.19, SD = 3.443). Participants were presented with a list of several activities and asked, which activities related to news use on social media they employed during an average week such as liking a news item on Facebook or commenting on a storyFootnote5. The sum of these activities was subsequently calculated (M=1.75, SD = 1.721).

Since prior research has demonstrated that sociodemographic factors correlate with distinctive practices of news consumption (Blekesaune, Elvestad, and Aalberg Citation2012) the variables of gender (51.2% female), age (M=44, SD = 15.514) and level of education attained or to be attained (6-point scale ranging from some high school to Master or Doctoral degree, M=3.15, SD = 1.183) were included in the analysis. To account for the constantly changing affordances of the various social media platforms (Bucher and Helmond Citation2018), as well as differences in news-related social media usage per platform (Newman et al. Citation2019), actual use of the most prominent platforms was incorporated as well. Respondents were asked if they had used different social media platforms. Facebook (62.9%), YouTube (62.8%), Instagram (29.7%), and Twitter (24.6%) were the social media platforms most frequently used and were, therefore, included in the model.

Analysis

To answer the hypotheses and research questions related to predictors of curation three binomial models predicting the probability of overall, news-boosting, and news-limiting curation were compiled. I employed multilevel regression modeling with random intercept (Deleeuw and Meijer Citation2008) as carried out in a previous analysis of the Reuters Digital News Survey data (Thurman et al. Citation2019) to account for its nested structure (individuals nested in countries) and potential variations in news interest, avoidance, extremism, and news-related online activities between each countryFootnote6. The independent variables were standardized to allow for a comparison of effect sizes. In addition, to see if the model holds up for each country and to explore cross-national differences in the hypothesized relations, specific logistic regressions for each of the 36 countries were employed. The results are displayed in Tables 5–40 in the online appendix (supplementary material).

Findings

Prevalence of Personal News Curation

The percentage of social media news users per country that report practices of overall curation, news-boosting, and news-limiting behavior is reported in . Across the thirty-six countries, between 80 percent (Turkey) and 39 percent (Japan) of social media news users said that they had in one way or another curated their news content during the last year. News-boosting activities were more common than news-limiting activities. When analyzed in detail (see online appendix Table 3, supplementary material) it becomes apparent that adding a user or organization because of the news they have posted is the most prevalent curation activity in all countries surveyed, followed predominantly by the two news-limiting items (delete a user or organization, changing settings to see less news) and changing settings for more news content as the least frequent act of news curation. Also depicted in is the overlap between news-limiting and news-boosting behavior (“both”). Twenty-five percent of all users that employ any personal news curation report that they employ news-limiting and news-boosting activities.

Predictors of Personal News Curation

displays the results of the multilevel binomial regression models on overall, news-boosting, and news-limiting curation. As is often the case with samples of that size, even smaller effects in the model become statistically significant (Lin, Lucas, and Shmueli Citation2013). Consequently, emphasis is placed on the interpretation of the effect sizes instead. Overall, the multilevel model explains 25 percent (overall curation), 23 percent (news-boosting), and 12 percent (news-limiting) of variance in the practices of news curation when the random intercept for country effects is included (conditional R2). Without the country effects, the variance decreases by less than two percent (marginal R2).

Table 1. Predictors of personal news curation: Multilevel binomial regression model with random intercept for country effects.

Besides the hypothesized relations, age was a highly significant factor for the multilevel and all of the country models. The younger the user, the more likely they are to engage in news-limiting and news-boosting curatorial practices. In terms of platforms, the model did not conclude universal results across countries. The strongest relations in the multilevel model can be found between Twitter and Facebook use and news-boosting practices. Twitter use makes news-boosting behavior more likely in 13 country models and Facebook is a positive factor for news-boosting for nine countries. These results are consistent with previous research into Twitter and Facebook that concluded that they have a higher share of news-oriented use than other platforms (Newman et al. Citation2019).

H1: Users with a higher level of news interest are more likely to engage in news-boosting curation.

In the multilevel model, news interest positively predicts practices of news-boosting curation to a rather large effect. In addition, for twenty of the thirty-six country models a significant positive relationship between news interest and news-boosting activities was found.

H2: Users who avoid news more frequently are more likely to engage in news-limiting curation.

News avoidance significantly predicts news-limiting curation with one of the largest effects in the multilevel model and all of the thirty-six country models. Individuals who are actively trying to avoid news more often (independent of specific news sources) are more likely to employ practices on social media that reduce their news exposure. This result is, to some degree, detrimental to the hope that people who avoid news or have a low interest in news might receive news through incidental exposure on social media. There is a lower chance of incidental exposure if users employ practices to negate news in their social media feed. Even though age, news interest, a high quantity of news sources and news related activities have a larger effect in the prediction of news-boosting behavior, users who say that they avoid news are also more likely to practice news-boosting curation. This rather paradoxical result could point towards a share of individuals that hold a general willingness to manage their news repertoire while including a tendency to avoid certain news in tandem with the act of boosting other news content. This will be addressed in more detail in regard to H4 and RQ2 in the discussion section.

H3: Users with a higher level of ideological extremism are more likely to engage in news-limiting curation.

In the multilevel model, political extremism has one of the smallest effects of all the predictors on news-limiting curation. Focusing on the country models, only in the United States did extremism make news-limiting curation significantly more likely. In the country model for France ideological extremism made personal news-limiting significantly less likely. In five of the country models (Sweden, United States, Belgium, Greece, and Malaysia), higher levels of ideological extremism predicted the likelihood of engagement in news curation overall. Overall, H3 is not supported in most countries and evidence found in the multilevel model is weak compared to other factors.

H4: Users with a higher level of news-related social media activities are more likely to engage in a) news-boosting and b) news-limiting curation.

Engaging in other news-related activities on social media proved to be the predictor with the highest effect in the multilevel models of overall, news-limiting, and news-boosting curation. Individuals who, for example, rate, like, favorite, and comment on news stories, or share them via social media are more likely to employ curatorial practices. A highly significant relationship can also be identified in all thirty-six country models on overall curation, news-boosting, and news-limiting curation, apart from Mexico, where it was found to not be a significant predictor for news-limiting curation.

RQ2: How are a) news-boosting and b) news-limiting curation related to the number of news sources consumed online?

In twenty-nine country models, a higher source count is a significant predictor for news-boosting behavior; in fourteen country models it significantly predicts news-limiting practices. In the multilevel model, the relation between the quantity of sources and news-boosting behavior has a larger effect than the relation between the quantity of sources and news-limiting curation.

To further analyze these last ambiguous results, I compare the mean amount of reported online sources in different user groups in . The group of users that employ news-boosting and news-limiting practices have the highest mean source count, followed by users who engaged in news-boosting curation only and users who just engage in news-limiting curation. The group of respondents who do not engage in any curation report the lowest mean amount of online sources consumed.

Table 2. Mean amount of news brands used for users who report specific curation behavior and those who do not.

These results are particularly insightful in two ways. On the one hand, the fact that news-boosting curators report a higher number of sources than users who only engage in news-limiting techniques could indicate that curatorial activities are connected to a wider or narrower news repertoire. On the other hand, however, the fact that users who engage exclusively in news-limiting activities still have a higher online source count than non-curators and users who employ both practices report more sources than news-curation boosters indicates that even news-limiting practices seem to be connected to a certain level of engagement with or willingness to manage their news diet. News-limiting practices might not necessarily indicate a lack of exposure to news (sources). Rather, one could think of a scenario where social media users are so invested in their social media news consumption that they are just very selective about which sources they include in their social media repertoire. Furthermore, news sources and other content can only be hidden or blocked if it exists in the newsfeed. So, an interest in and activities around news on social media might be accompanied by more exposure to (dissonant) information and/or information overload which then increases the chance for news limiting behavior. This assumption resonates with the findings from H2 on the relationship between news avoidance and news-boosting behavior and H4 about the importance of news-related social media activities as a predictor of news-limiting curation. Future research should search for a factor that, at least to some extent, is a predictor of curation and a high source count and is not yet included in the model.

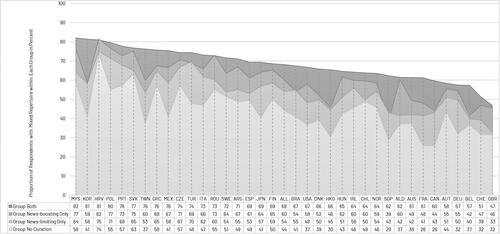

A greater number of sources used does not necessarily imply that those sources were particularly diverse. However, when the amount of used sources is relatively low and curation is associated with an increase in sources used (e.g. in Germany on average a step up from two to three weekly sources) one can adapt Fletcher and Nielsen’s argument (Citation2017) that any increase in the number of sources has the potential to lead to more diverse consumption. By assessing the partisan leanings of each outlet through their audience (audience-based ideology score, Fletcher and Nielsen Citation2018a), a proxy of the political diversity of each individual’s information repertoire can be measured. In , the four different groups with specific curatorial behavior are compared concerning the diversity of their repertoire. The share of users in each group with a “mixed repertoire”, meaning that they consume at least one source with a right-leaning audience and one source with a left-leaning audience, is displayed. Again, we can see that the highest share of users with a mixed repertoire can be found within the group of respondents that employ news-limiting and news-boosting techniques, followed by the group of news-boosting curators only. Within the group of news-limiting curators, the share of users with a diverse repertoire is higher than it is for the group of non-curators. So, even users who can potentially increase their selective exposure through news-limiting curation practices report a more diverse repertoire than non-curators did, which might ease concerns about potential polarization through curation.

Figure 2. Proportion of respondents who use both a news source with a left-leaning audience and a source with a right-leaning audience (“mixed repertoire”). The ideological leaning of each news source with more than 50 users is accessed through political orientation of its audience within the Reuters Digital News Survey.

Notes. ALL = all countries combined (n = 49382), ARG = Argentina (n = 1707), AUS = Australia (n = 1125), AUT = Austria (n = 1051), BEL = Belgium (n = 1203), BRA = Brazil (n = 1770), CAN = Canada (n = 1595), CHE = Switzerland (n = 1631), CHL = Chile (n = 1802), CZE = Czech Republic (n = 1236), DEU = Germany (n = 904), DNK = Denmark (n = 990), ESP = Spain (n = 1527), FIN = Finland (n = 1013), FRA = France (n = 1230), GBR = Great Britain (n = 897), GRC = Greece (n = 1596), HKG = Hong Kong (n = 1629), HRV = Croatia (n = 1582), HUN = Hungary (n = 1574), IRL = Ireland (n = 1283), ITA = Italy (n = 1512), JPN = Japan (n = 814), KOR = Korea (n = 1204), MEX = Mexico (n = 1819), MYS = Malaysia (n = 1799), NLD = Netherlands (n = 1047), NOR = Norway (n = 1078), POL = Poland (n = 1500), PRT = Portugal (n = 1439), ROU = Romania (n = 1753), SGP = Singapore (n = 1606), SVK = Slovakia (n = 1451), SWE = Sweden (n = 1007), TUR = Turkey (n = 1702), TWN = Taiwan (n = 853), USA = USA (n = 1453).

Discussion

This article has explored personal curatorial practices that complement and balance the selection of news stories through journalists, social contacts, and algorithms in the social media newsfeed, extending previous research related to news curation on social media (Wells and Thorson Citation2017; Song, Jung, and Kim Citation2017; Lee et al. Citation2019) by differentiating news-limiting and boosting practices, comparing practices and predictors across thirty-six countries and linking them to news repertoires. It finds that curatorial practices such as following a news organization on Twitter or hiding news content from a Facebook friend are common among news users on social media. Across all national samples, the respondents were more likely to engage in news-boosting than news-limiting practices which ties in with previous results in selective exposure literature that found a higher prevalence of selective exposure than selective avoidance online (Garrett, Carnahan, and Lynch Citation2013).

News Limiting Curation Beyond News Avoidance

Multilevel regression models demonstrated that practices of personal news curation are linked to a wider repertoire of news sources online and the willingness to engage in other news-related activities on social media. News interest is a significant predictor of news-boosting curation and news-avoidance is linked to news-limiting behavior on social media. The relations between news interest and avoidance and limiting and boosting practices can be seen as another indicator in the assumption that the mechanisms of social media news consumption solidify existing imbalances and inequalities in news use (Kümpel Citation2020a; Thorson Citation2020). If those who want to avoid news in general also shut out news content in their newsfeed, the potential of social media news consumption to overcome gaps in news use and incidentally expose citizens not interested in current events might decrease.

But even though users that find themselves actively trying to avoid the news more frequently report news-limiting practices in social media, additional group comparisons demonstrated that news-limiting curation is associated with a higher quantity of news sources online as well as a more diverse repertoire of sources compared to users who do not engage in curation at all. This dynamic might be explained by the underlying motivations for limiting behavior. Limiting news from the news feed might not necessarily signify a lack of interest. Attempting to reduce and control the amount of news one is exposed to, is often connected to mood management or a lack of trust (Toff and Nielsen Citation2018; Woodstock Citation2014), but not necessarily a lack of interest. In the binominal regression models, one can see that a high level of news interest predicts not only news-boosting curation and news curation overall but also, to a lesser extent, news-limiting behavior. If a user is interested in news and subsequently cares about their news repertoire on social media, this might also include acts of blocking and hiding news content.

The Lack of Binaries in Social Media News Use

These results can motivate us to think of practices of news-limiting activities not only in terms of news avoidance but, rather, as practices of news repertoire or media repertoire management which suggests that news-limiting and news-boosting are not two binary or discrete practices but different practices situated within the category of news engagement. In the current media environment where journalists move from a gatekeeping to a curating position (Thorson and Wells Citation2016), intentionally shaping one's social media feed can be seen as a way of building and managing individual news repertoires and, in a way, of becoming one’s own editor.

Discussing personal news curation represents a theoretical extension of past work because these practices have the potential to challenge assumptions about concepts of incidental versus intentional news exposure. Against the background of discussions on the benefits of incidental news exposure, this article demonstrates that curation has the potential to stabilize existing gaps in news use because users interested in news tend to boost news content and users who say they avoid news are also limiting news in their social media feed. In light of the individual differences in news exposure and consumption on social media, Kümpel (Citation2020a) argues that we should reconsider the notion of incidental exposure and proposes that we differentiate between various degrees of ‘incidental’ exposure. From the results of this article, we can assume that a large number of users proactively shape their news feeds through curation and it would be inadequate to characterize their exposure as completely non-intentional. An inclusion of measurements of personal news curation into studies on effects of incidental news exposure, as Kümpel argues, “might prove useful to determine the conditions under which learning or political participation is (not) to be expected” (Kümpel Citation2020a, 10).

While personal news curation can be theoretically conceptualized as a practice of selective exposure—a media use pattern discussed in the context of fragmentation and polarization (Mutz Citation2006; Sunstein Citation2001)—engaging in this kind of curation is associated with a higher quantity and diversity of news sources, news interest, and more news-related online activities. Concerns that news-limiting behavior might be linked to more extreme political attitudes were not substantiated for all countries apart from the US. Even though no statements about the exact influence of personal curatorial practices on the mix of content on social media newsfeeds can be made from this study, the results suggest that curatorial practices might act as a counterpoint to the possible constricting effects of system-driven customization caused by algorithmic filtering (Dylko et al. Citation2018). From a platform perspective, the software features that allow the blocking of contacts or offer the ability to reduce the amount of specific content could not only let users view the platform more favorably and avoid the cutting of ties but also prevent news fatigue or information overload.

Examining data gathered in many countries allowed for the exploration in different national contexts and to overcome a US or Eurocentric bias. Boulianne (Citation2019), as well as Rojas and Valenzuela (Citation2019), have shown that much current research in political communication is based on US samples and that these results are often treated as a contextless norm that shapes expectations for scholarship in other areas of the world.Footnote7 Employing cross-national research allows for the examination of the conditions under which news-related social media practices exist.

Towards a Coherent Theoretical Framework

By adopting the concept of curated flows, this exploration of secondary data has provided an insight into the patterns of curatorial practices and its predictors. These results provide a basis from which to test specific assumptions in future research. While this analysis allowed us to explore the patterns of curation thanks to a wide and representative dataset, the survey design of the Reuters Digital News Survey did not represent several aspects that might also influence these practices and should be considered for a coherent theoretical model that situates personal practices of news curation in the existing literature on selective exposure and incidental news exposure.

It should be noted that the practices of adjusting one’s network or settings on social media covered in the Reuters survey and this article are not the only ways of influencing exposure to news on social media. For example, even if users do not hide posts from a Facebook friend, they can still (decide to) ignore them. “People can consumptively curate both by manipulating the technology and selective practices of looking” (Davis Citation2017, 774). From the regression results, it emerges that other activities around social media news use and youth seem to be relevant factors in predicting curatorial activities while the level of education was not. A level of literacy that grasps the sheer technical ability differentiated by platforms can be approached as a determining factor and should be tested in future research. Furthermore, the motivational factors that determine a willingness to actively manage one’s news diet in the context of social media is a desideratum. Here the social media news efficacy concept (Park Citation2019) that describes news users’ confidence to the extent to which they are able to find their preferred news stories on social media and make sense of them could be a promising avenue for further study. Qualitative approaches such as post-exposure walkthroughs (Kümpel Citation2019), thinking aloud methods (Schmidt et al. Citation2019), or repertoire mapping techniques (Merten Citation2020) have proven fruitful in the exploration of (the existence of) individual strategies behind news-related social media practices. Overall, exploring the amount of intentionality that shapes news repertoires and the adoption of online intermediaries as news sources or, rather, the serendipity of these practices will remain a fascinating theoretical and methodological challenge.

rdij_a_1829978_sm3832.pdf

Download PDF (703.9 KB)Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Uwe Hasebrink, Sascha Hölig, Heidi Schulze, Michel Clement, Judith Moeller, the editors, and reviewers for their insightful and constructive feedback on earlier versions of this article and the data analysis. The paper is based on data from the Reuters Digital News Survey (2017) realized by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University in cooperation with other academic partners such as the Leibniz-Institute for Media Research in Germany.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Even though overlaps can be expected, other news-related social media activities and curatorial practices can also be differentiated theoretically. While engagement with news content through sharing or commenting on news is concentrated on a current interaction with news or phases of media appropriation and distribution, following a source or adjusting settings to see more or less news can be categorized as acts of media selection (Donsbach Citation1991; Hasebrink Citation2003). The potential impact of personal news curation on the news feed is often communicated directly by the platforms (e.g. hide all content from this organisation, see users x posts first in your newsfeed) and is, therefore, more obvious than the consequences of clicking links, liking, commenting, or sharing posts. While those actions might also have the potential to alter the composition of one’s own future newsfeed, users are not necessarily aware of the algorithmic inferences based on these actions (Schmidt et al. Citation2019; Bucher Citation2017).

2 For Brazil and Turkey, the samples are representative of the urban rather than the national population, which should be taken into account when interpreting the country-specific results in the online appendix.

3 If not otherwise noted, statistical figures are reported for the weighted sample of all participants across the thirty-six countries who stated that they use social media for news consumption and were, therefore, asked about their personal news curation practices (n=49.382). Bartlett: Chi2 = 6223.48***, KMO = .563, Variance = 35.478.

4 The Reuters Digital News Survey relied on self-identification of news avoidance instead of filtering participants with low news exposure. Such operationalization does not necessarily entail a lack of news consumption or news interest.

5 The following activities were part of our measure for news activities on social media (α = .66): Rate, like or favorite a news story; Comment on a news story in a social network (e. g. Facebook or Twitter); Share a news story via a social network (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn); Share a news story via instant messenger (e.g. WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger); Post or send a news-related picture or video to a social network site; Post or send a picture or video to a news website/news organization; Vote in an online poll via a news site or social network; Talk online with friends and colleagues about a news story (e.g. by email, social media, instant messenger).

6 Bryan and Jenkins (Citation2016) demonstrate that a minimum of thirty countries is required to derive accurate estimates for random coefficient variance in multilevel logistic models. Even though with thirty-six groups the model fulfills that recommendation in additional binomial regression with country variables as fixed effects was run that showed almost identical results (see Table 4 in the online appendix). In comparison of the multilevel and the fixed-term model the second decimal place varies in 8 of 39 effects sizes by 1 or 2 digits, otherwise significance levels and effect sizes are identical.

7 If this study would have only been carried out in a US context, the singular effects of political extremism would not have been contextualized and the study could have served as a basis for additional research in other countries utilizing US-specific results as its basis. Also for example, an analysis of just the US, British, Italian, German, Spanish and Danish samples of the Reuters Digital News Survey 2017 dataset would not have shown a significant effect of news interest in relation to news-boosting curation.

References

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Shanto Iyengar. 2008. “A New Era of Minimal Effects? The Changing Foundations of Political Communication.” Journal of Communication 58 (4): 707–731.

- Blekesaune, Arid, Eiri Elvestad, and Toril Aalberg. 2012. “Tuning out the World of News and Current Affairs – An Empirical Study of Europe’s Disconnected Citizens.” European Sociological Review 28 (1): 110–126.

- Bode, Leticia. 2016. “Political News in the News Feed: Learning Politics from Social Media.” Mass Communication and Society 19 (1): 24–48.

- Boulianne, Shelley. 2019. “US Dominance of Research on Political Communication: A Meta-View.” Political Communication 36 (4): 660–665.

- Bryan, Mark, and Stephen Jenkins. 2016. “Multilevel Modelling of Country Effects: A Cautionary Tale.” European Sociological Review 32 (1): 3–22.

- Bucher, Taina. 2017. “The Algorithmic Imaginary: Exploring the Ordinary Affects of Facebook Algorithms.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (1): 30–44.

- Bucher, Taina, and Anne Helmond. 2018. “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms.” In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media, edited by Jean Burgess, Thomas Poell, and Alice Marwick. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Clark, Jessica, and Patricia Aufderheide. 2009. Public Media 2.0: Dynamic, Engaged Publics. Washington, DC: Center for Social Media, School of Communication, American University.

- Couldry, Nick, and Andreas Hepp. 2017. The Mediated Construction of Reality. Cambridge, Malden, MA: Polity Press.

- Davis, Jenny. 2017. “Curation: A Theoretical Treatment.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (5): 770–783.

- Deleeuw, Jan, and Erik Meijer, eds. 2008. Handbook of Multilevel Analysis. New York: Springer.

- Delli Carpini, Michael, and Scott Keeter. 1996. What Americans Know about Politics and Why It Matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- DeVito, Michael. 2017. “From Editors to Algorithms.” Digital Journalism 5 (6): 753–773.

- Donsbach, Wolfgang. 1991. Medienwirkung Trotz Selektion: Einflussfaktoren Auf Die Zuwendung zu Zeitungsinhalten [Media Effects despite Selection: Factors Influencing Attention towards Newspaper Content]. Köln: Böhlau.

- Dylko, Ivan, Igor Dolgov, William Hoffman, Nicholas Eckhart, Maria Molina, and Omar Aaziz. 2017. “The Dark Side of Technology: An Experimental Investigation of the Influence of Customizability Technology on Online Political Selective Exposure.” Computers in Human Behavior 73 (8): 181–190.

- Dylko, Ivan, Igor Dolgov, William Hoffman, Nicholas Eckhart, Maria Molina, and Omar Aaziz. 2018. “Impact of Customizability Technology on Political Polarization.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 15 (1): 19–33.

- Fletcher, Richard, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018a. “Automated Serendipity. The Effect of Using Search Engines on News Repertoire Balance and Diversity.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 976–989.

- Fletcher, Richard, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018b. “Are People Incidentally Exposed to News on Social Media? A Comparative Analysis.” New Media & Society 20 (7): 2450–2468.

- Fletcher, Richard, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2019. “Generalised Scepticism: How People Navigate News on Social Media.” Information, Communication & Society 22 (12): 1751–1769.

- Fletcher, Richard, and Sora Park. 2017. “The Impact of Trust in the News Media on Online News Consumption and Participation.” Digital Journalism 5 (10): 1281–1299.

- Fletcher, Richard, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2017. “Using Social Media Appears to Diversify Your News Diet, Not Narrow It.” Nieman Lab. http://www.niemanlab.org/2017/06/using-social-media-appears-to-diversify-your-news-diet-not-narrow-it/.

- Garrett, R. Kelly, Dustin Carnahan, and Emily K Lynch. 2013. “A Turn toward Avoidance? Selective Exposure to Online Political Information, 2004–2008.” Political Behavior 35 (1): 113–134.

- Garrett, Kelly, and Natalie Jomini Stroud. 2014. “Partisan Paths to Exposure Diversity: Differences in Pro- and Counterattitudinal News Consumption.” Journal of Communication 64 (4): 680–701.

- Hargittai, Eszter. 2005. “Survey Measures of Web-Oriented Digital Literacy.” Social Science Computer Review 23 (3): 371–379.

- Hargittai, Eszter, and Eden Litt. 2013. “New Strategies for Employment? Internet Skills and Online Privacy Practices during People’s Job Search.” IEEE Security & Privacy 11 (3): 38–45.

- Hasebrink, Uwe. 2003. “Nutzungsforschung [Research on Media Use].” In Öffentliche Kommunikation: Handbuch Kommunikations- Und Medienwissenschaft, edited by Günter Bentele, Hans-Bernd Brosius, and Otfried Jarren, 101–127. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- John, Nicholas, and Shira Dvir-Gvirsman. 2015. “I Don’t like You Any More’: Facebook Unfriending by Israelis during the Israel–Gaza Conflict of 2014.” Journal of Communication 65 (6): 953–974.

- Ju, Alice, Sund Jeong, Jong Ho, and Hsiang I. Chyi. 2014. “Will Social Media save Newspapers? Examining the Effectiveness of Facebook and Twitter as News Platforms.” Journalism Practice 8 (1): 1–17.

- Kaiser, Johannes, Tobias Keller, and Katharina Kleinen-von Königslöw. 2018. “Incidental News Exposure on Facebook as a Social Experience: The Influence of Recommender and Media Cues on News Selection.” Communication Research (October 2018). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650218803529

- Kreiss, Daniel. 2016. “Seizing the Moment: The Presidential Campaigns’ Use of Twitter during the 2012 Electoral Cycle.” New Media & Society 18 (8): 1473–1490.

- Kümpel, Anna Sophie. 2019. “The Issue Takes It All?” Digital Journalism 7 (2): 165–186.

- Kümpel, Anna Sophie. 2020a. “Nebenbei, Mobil Und Ohne Ziel? Eine Mehrmethodenstudie Zu Nachrichtennutzung Und -Verständnis Von Jungen Erwachsenen [On the Side, Mobile and Aimless? A Multi-Method Study on News Usage and Understanding of Young Adults].” Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft 68 (1/2): 11–31.

- Kümpel, Anna Sophie. 2020b. “The Matthew Effect in Social Media News Use: Assessing Inequalities in News Exposure and News Engagement on Social Network Sites (SNS).” Journalism 21 (8): 1083–1098.

- Lee, Francis, Michael Chan, Hsuan-Ting Chen, Rasmus Nielsen, and Richard Fletcher. 2019. “Consumptive News Feed Curation on Social Media as Proactive Personalization: A Study of Six East Asian Markets.” Journalism Studies 20 (15): 2277–2292.

- Lee, Sun Kyong, Kyun Soo Kim, and Joon Koh. 2016. “Antecedents of News Consumers’ Perceived Information Overload and News Consumption Pattern in the USA.” International Journal of Contents 12 (3): 1–11.

- Lin, Mingfeng, Henry Lucas, and Galit Shmueli. 2013. “Research Commentary – Too Big to Fail: Large Samples and the p-Value Problem.” Information Systems Research 24 (4): 906–917.

- Merten, Lisa. 2020. “Contextualized Repertoire Maps: Exploring the Role of Social Media in News-Related Media Repertoires.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 21 (2). DOI:https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.2.3235

- Mitchell, Amy, Jeffrey Gottfried, Jocelyn Kiley, and Katerina Eva Matsa. 2014. “Political Polarization & Media Habits.” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project (blog). October 21, 2014. https://www.journalism.org/2014/10/21/political-polarization-media-habits/.

- Moeller, Judith, Robbert Nicolai van de Velde, Lisa Merten, and Cornelius Puschmann. 2020. “Explaining Online News Engagement Based on Browsing Behavior: Creatures of Habit?” Social Science Computer Review 38 (5): 616–632.

- Mutz, Diana C. 2006. Hearing the Other Side: Deliberative versus Participatory Democracy. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David Levy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2017. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2019. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Park, Chang Sup. 2019. “Does Too Much News on Social Media Discourage News Seeking? Mediating Role of News Efficacy between Perceived News Overload and News Avoidance on Social Media.” Social Media + Society 5 (3). Advance online publication. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119872956

- Prior, Markus. 2007. Post-Broadcast Democracy: How Media Choice Increases Inequality in Political Involvement and Polarizes Elections. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Rojas, Hernando, and Sebastián Valenzuela. 2019. “A Call to Contextualize Public Opinion-Based Research in Political Communication.” Political Communication 36 (4): 652–659.

- Ruggiero, Thomas E. 2000. “Uses and Gratifications Theory in the 21st Century.” Mass Communication and Society 3 (1): 3–37.

- Schmidt, Jan-Hinrik, Lisa Merten, Uwe Hasebrink, Isabell Petrich, and Amelie Rolfs. 2019. “How Do Intermediaries Shape News-Related Media Repertoires and Practices? Findings from a Qualitative Study.” International Journal of Communication 13: 853–873.

- Skovsgaard, Morten, and Kim Andersen. 2019. “Conceptualizing News Avoidance: Towards a Shared Understanding of Different Causes and Potential Solutions.” Journalism Studies 21 (4): 459–476.

- Song, Haeyeop, Jaemin Jung, and Youngju Kim. 2017. “Perceived News Overload and Its Cognitive and Attitudinal Consequences for News Usage in South Korea.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 94 (4): 1172–1190.

- Stroud, Natalie Jomini. 2008. “Media Use and Political Predispositions: Revisiting the Concept of Selective Exposure.” Political Behavior 30 (3): 341–366.

- Stroud, Natalie Jomini. 2010. “Polarization and Partisan Selective Exposure.” Journal of Communication 60 (3): 556–576.

- Stroud, Natalie Jomini, Cynthia Peacock, and Alexander L. Curry. 2020. “The Effects of Mobile Push Notifications on News Consumption and Learning.” Digital Journalism 8 (1): 32–48.

- Sunstein, Cass. 2001. Republic.Com. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Tewksbury, David, Andrew J. Weaver, and Brett D. Maddex. 2001. “Accidentally Informed: Incidental News Exposure on the World Wide Web.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 78 (3): 533–554.

- Thorson, Kjerstin. 2020. “Attracting the News: Algorithms, Platforms, and Reframing Incidental Exposure.” Journalism 21 (8): 1067–1082.

- Thorson, Kjerstin, Kelley Cotter, Mel Medeiros, and Chankyung Pak. 2019. “Algorithmic Inference, Political Interest, and Exposure to News and Politics on Facebook.” Information, Communication & Society (July 2019). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1642934.

- Thorson, Kjerstin, and Chris Wells. 2016. “Curated Flows: A Framework for Mapping Media Exposure in the Digital Age.” Communication Theory 26 (3): 309–328.

- Thurman, Neil, Judith Moeller, Natali Helberger, and Damian Trilling. 2019. “My Friends, Editors, Algorithms, and I: Examining Audience Attitudes to News Selection.” Digital Journalism 7 (4): 447–469.

- Toff, Benjamin, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. “I Just Google It’: Folk Theories of Distributed Discovery.” Journal of Communication 68 (3): 636–657.

- Trilling, Damian. 2019. “Conceptualizing and Measuring News Exposure as Network of Users and News Items.” In Measuring Media Use and Exposure Recent Developments and Challenges, edited by Christina Peter, Theresa Naab, and Rinaldo Kühne, 297–317. Köln: Halem.

- Valeriani, Augusto, and Cristian Vaccari. 2016. “Accidental Exposure to Politics on Social Media as Online Participation Equalizer in Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom.” New Media & Society 18 (9): 1857–1874.

- Villi, Mikko, Johanna Moisander, and Annamma Joy. 2012. “Social Curation in Consumer Communities: Consumers As Curators of Online Media Content.” Advances in Consumer Research 40: 490–495. Volume

- Wagner, María Celeste, and Pablo J. Boczkowski. 2019. “Angry, Frustrated, and Overwhelmed: The Emotional Experience of Consuming News about President Trump.” Journalism. Advance online publication. (September 2019). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919878545.

- Wells, Chris, and Kjerstin Thorson. 2017. “Combining Big Data and Survey Techniques to Model Effects of Political Content Flows in Facebook.” Social Science Computer Review 35 (1): 33–52.

- Woodstock, Louise. 2014. “The News-Democracy Narrative and the Unexpected Benefits of Limited News Consumption: The Case of News Resisters.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 15 (7): 834–849.

- Zhu, Qinfeng, Marko Skoric, and Fei Shen. 2017. “I Shield Myself from Thee: Selective Avoidance on Social Media during Political Protests.” Political Communication 34 (1): 112–131.

- Zuckerberg, Mark. 2018. “Continuing Our Focus for 2018 to Make Sure the Time We All Spend on Facebook is Time Well Spent.” Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10104445245963251

- Zuiderveen Borgesius, Frederik J., Damian Trilling, Judith Moeller, Balázs Bodó, Claes H. de Vreese, and Natali Helberger. 2016. “Should we Worry about Filter Bubbles?” Internet Policy Review 5 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.14763/2016.1.401