Abstract

As people increasingly rely on social media for news, it is important to understand what types of news media they are likely to come across in their social media environment. Exposure to news content in social media is the result of complex, interdependent systems driven by individuals, platforms, and institutions—among others—but an important element of exposure is what kind of news content engaged individuals tend to share with their peers. This study examines how partisan news media may be influential in social media by proposing that their content is shared more frequently and that they share more emotional content than non-partisan news media. This study examines more than 300,000 tweets and retweets from 22 news organizations to understand what type of political news is shared more widely in social media and how emotion in news content can influence political news sharing. The results suggest that partisan news media are shared more frequently in Twitter, and that partisan news content is more likely to express emotion compared with non-partisan news. Overall, partisan and emotional news media content is disproportionately amplified in social media, which may have important consequences for others who rely on social media for political news information.

Social media provide interested and engaged news consumers the ability to help shape the news environment of their peers by sharing content with their social networks (Thorson and Wells Citation2016; Zhang et al. Citation2018). As audiences for partisan news are among the most politically interested and engaged individuals (Stroud Citation2011; Wojcieszak et al. Citation2016), it is worth exploring how partisan news media are shaping the political information environment in social media. This study explores the idea that engaged news consumers function like radio repeaters—amplifying existing signals so that others are more likely to receive them.

The potential effect of this social amplification is that users of social media are more likely to be directly exposed to content that others have shared and endorsed (Zhang et al. Citation2018). In other words, people who rely on shared information in social media may be exposed to substantively more partisan news than if they sought news directly from news organizations (Bright Citation2016; Faris et al. Citation2017). This study first posits that tweets posted by partisan news outlets are more likely to be shared on social media, relative to tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets. Second, the study highlights emotional content as an important facilitator of news sharing online. Journalism scholars have called for greater need to understand how emotions shape engagement with news media (Lecheler Citation2020; Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2019, Citation2020), and it is known that emotions can both influence selection of news content (e.g., Soroka, Fournier, and Nir Citation2019) and motivate political information-sharing online (e.g., Hasell and Weeks Citation2016). This study therefore also posits that tweets shared by partisan news organizations are more likely to contain emotional content than tweets shared by non-partisan news organizations and that this emotional content will facilitate sharing in social media.

To examine these predictions, I use two datasets from the Twitter accounts of 22 prominent US news organizations, which include liberal, conservative, and non-partisan news media. The first dataset includes the meta-data of retweets and replies to each tweet posted by the 22 news organizations over the course of three months. The second uses a machine-learning algorithm to content analyze tweets and retweets of those 22 news organizations for the presence of emotion. Together, these data provide information about the frequency with which people share and reply to partisan and non-partisan news, and what type of emotional news content is most likely to be shared in social media. The results show that tweets posted by partisan news outlets were retweeted more and replied to more than were tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets. The findings also demonstrate that while the majority of tweets posted by all sampled news organizations were emotionally neutral, news content that expressed anger, anxiety, and enthusiasm is shared disproportionally more. Overall, the results show that emotional, partisan news content is disproportionately amplified in social media, which may have important consequences for the way people experience journalism in the United States.

News Exposure in Social Media

The contemporary media environment provides widespread availability of varying news media content, including more partisan media. The rise in the availability and popularity of partisan news over the last two decades speaks to two distinct, but highly interrelated phenomena; the effects of partisan selective exposure and of incidental exposure to news media.

With regards to partisan selective exposure, the measurable differences in partisan news media selection patterns can help explain changes in attitudes about politics and government, including increased polarization and negative views of the opposing party (e.g., Levendusky Citation2013; Stroud Citation2010, Citation2011; Wojcieszak et al. Citation2016). The direct audience for partisan news media may not be large (Prior Citation2013), but they tend to be made up of the most politically interested and engaged individuals. Exposure to partisan news media can result in more interest in politics (Coe et al. Citation2008), increased political participation (Stroud Citation2011; Wojcieszak et al. Citation2016), and increased information-sharing (Hasell and Weeks Citation2016). Because partisan news media are associated with these behaviors, it is likely that partisan news media have a significant influence on the political information environment despite their relatively small number of direct viewers and subscribers (Druckman, Levendusky, and McLain Citation2018; Leeper Citation2014; Prior Citation2013).

However, many people do not seek out news media but rely on others to share information with them (Gil de Zúñiga, Weeks, and Ardèvol-Abreu Citation2017). For these individuals, exposure to news media is incidental, rather than selective, and is heavily dependent on the behaviors of other actors in their social networks (Fletcher and Nielsen Citation2018; Tewksbury, Weaver, and Maddex Citation2001; Thorson and Wells Citation2016). There are some questions as to whether incidental exposure has similar effects to selective exposure (Bode Citation2016; Gil de Zúñiga, Weeks, and Ardèvol-Abreu Citation2017; Kim, Chen, and Gil de Zúñiga Citation2013), but audiences in social media are consistently more likely to trust and attend to news information shared with them by their peers (Anspach Citation2017; Sterrett et al. Citation2019; Turcotte et al. Citation2015). Because of this, individuals who actively engage with news content by sharing and replying to news media organizations in social media have the potential to influence the news content to which others are incidentally exposed.

Partisan news media users tend to be the most politically engaged, and it is likely that these individuals are also among the most active when it comes to sharing and responding to political news in social media. Studies have found that people who share political information online also consume partisan news media at significantly greater rates than those who do not share information (Pew Research Center Citation2013). Further, exposure to like-minded partisan news can increase information-sharing in social media (Hasell and Weeks Citation2016; Weeks, Lane, et al. Citation2017), and partisans tend to actively share content favorable to their views (Shin and Thorson Citation2017). There is also evidence that extreme partisans discuss politics more frequently in social media compared to people who hold more moderate political views (Barberá and Rivero Citation2015). In sum, users of partisan news media have been found to discuss politics in social media more frequently and share political information in social media more frequently than users of non-partisan news media.

Partisan news media play an important role in shaping the information environment in social media (Faris et al. Citation2017; Vargo and Guo Citation2017), in part because people who consume partisan news media are active and engaged. Because of the behaviors associated with exposure to partisan news media, it is likely that partisan news outlets will be associated with more engagement, in terms of sharing and responding to news items in social media. The first hypothesis states that tweets posted by partisan news outlets will receive more retweets (H1a) and more replies (H1b) than tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets.

Emotion and Information-Sharing

When examining what motivates sharing of partisan news media in social media, much of the research has focused on individual factors such as interest, perceived opinion leadership, and online networks (Kalsnes and Larsson Citation2018; Weeks, Ardèvol-Abreu, et al. Citation2017). However, researchers have also begun to explore the role of content in sharing and responding to political news media online and in social media (e.g., Himelboim et al. Citation2016; Kümpel, Karnowski, and Keyling Citation2015; Trilling, Tolochko, and Burscher Citation2017), including the influence of emotional content.

Emotions play an important role in politics (Brader Citation2006), and news media often use words and imagery that elicit specific emotional responses (Graber Citation1996; Peters Citation2011). Emotions are short-lived mental states that vary in intensity and are typically directed at external stimuli (Nabi Citation1999). Differing discrete emotions are associated with unique attitudinal and behavioral responses (e.g., Lazarus Citation1991; Nabi Citation1999, Citation2003; Valentino et al. Citation2011). In particular, anger, anxiety, and enthusiasm are frequently aroused by political information and have distinct, important political outcomes (Marcus, MacKuen, and Neuman Citation2011). For example, feelings of anger can increase participation in politics and strengthen objection to opposing views (MacKuen et al. Citation2010; Valentino et al. Citation2011; Wojcieszak et al. Citation2016). Meanwhile, anxiety can increase willingness to consider opposing views and encourage relevant information seeking (MacKuen et al. Citation2010; Valentino et al. Citation2008). Most of the research on positive emotion and political behavior focuses on enthusiasm because it is associated with participatory actions and mobilization (Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Citation2000; Valentino et al. Citation2011). Like anger, enthusiasm can also increase costly political participation (Valentino et al. Citation2011), though others have found that it can decrease political participation in some cases (Weber Citation2013). In sum, discrete emotions can have an important influence on political behaviors, including engagement with news.

Partisan news media are particularly suited to elicit emotional responses, and there is evidence that content provided by partisan news media is often emotional. Primetime content for partisan cable news consists of personality-based, commentary style shows that help drive ratings and profits. Often these shows are designed to specifically arouse emotions, such as anger (O’Reilly Citation2006). Research has found that partisan news blogs, talk radio, and cable news tend to focus on elements of politics that emphasize and encourage the arousal of anger and anxiety (Sobieraj and Berry Citation2011; Young Citation2019). Partisan news media also tend to focus on the negative aspects of opposing parties and candidates and often promote the merits of one ideology, while demeaning other views (Berry and Sobieraj Citation2013; Smith and Searles Citation2014). It is likely that these patterns of coverage extend to how partisan news outlets use social media, so the second hypothesis states that tweets posted by partisan news outlets will be more likely to express anger, anxiety, and enthusiasm than tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets (H2).

Partisan news coverage can also elicit emotional reactions in news users, especially when individuals have a strong partisan identity (Blanton, Strauts, and Perez Citation2012; Neuman, Marcus, and MacKuen Citation2018). Negativity in news media attracts more attention from audiences, who also tend to respond more strongly to negative news (Soroka, Fournier, and Nir Citation2019; Soroka and McAdams Citation2015). Given that partisan news is especially negative, it may elicit stronger emotional reactions. The arousal of emotional can lead people to share more information about politics in social media (Hasell and Weeks Citation2016) and emotional content within the news item itself can increase the likelihood that it will be shared (Al-Rawi Citation2019; Berger and Milkman Citation2012; Kilgo, Lough, and Riedl Citation2020; Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan Citation2013). However, it is unclear whether emotional valence matters; some research has found that positive news tends to be shared more (Al-Rawi Citation2019; Trilling, Tolochko, and Burscher Citation2017), while other work finds sharing to be more dependent on arousal than valence (Berger and Milkman, Citation2012). These studies demonstrate the emotions expressed in the content of political news can increase the likelihood that the news story will be shared, although it is still unclear how specific discrete emotions might influence news sharing in social media. Considering this, the final hypothesis posits that the retweets of partisan news will be more likely to express anger, anxiety, or enthusiasm than to be emotionally neutral (H3).

Method

To test these hypotheses, I conducted two analyses designed to evaluate which types of news outlets receive the most engagement on Twitter. Twitter has fewer users than Facebook and other platforms, however, discussions on Twitter often filter through mainstream news media and can be influential to public discourse beyond users of the platform (Chadwick Citation2013). Journalists, politicians, and other political actors tend to use and interpret Twitter discussions as representing public opinion and sentiment, frequently incorporating Twitter discussions and narratives into mainstream journalism and political messaging (Anstead and O’Loughlin Citation2015; Lukito et al. Citation2020; McGregor Citation2019; Mourão Citation2015). While journalists’ use of Twitter in this way raises a number of problems (see McGregor Citation2019), such processes help explain how engagement with news media on Twitter can have substantial impacts both within and beyond the platform itself. As a result, Twitter provides a useful platform to test this study’s hypotheses.

This study used Forsight by Crimson Hexagon, a machine-learning algorithm, to collect and analyze the Twitter content. Forsight provides access to an archive of all publicly available tweets posted to Twitter. It allows for Boolean searches and contains a machine-learning tool that allows the user to train the software to code content. I collected two separate samples, which are described briefly below and in more detail in Appendix A.

News Outlet Sample

To examine the first hypothesis, which posited that tweets posted by partisan news outlets will receive more retweets and replies than tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets, a sample of tweets posted by 22 news sources was collected. The news sources are a mix of popular print publications, television news, and political news sites that publish daily news and commentary on US domestic political events and post this news on Twitter. The sample balances the number and types of news sources across three ideological categories: liberal, conservative, and non-partisan news. Each outlet was the categorized into its respective ideological category after considering whether its published content systematically favors one ideology over another (Budak, Goel, and Rao Citation2016), whether the outlet explicitly claims a specific ideology (i.e., The Daily Kos), or whether its audience has a clear partisan leaning (Pew Research Center Citation2014). More information about how the sample was selected and categorized by ideology can be found in online Appendix A. The news sources and their respective partisan categorizations are shown in .

Table 1. News sources by partisan categorization.

The sample consists of every tweet posted from the main Twitter account of these sources from three randomly selected months in 2015. The analyses for Hypotheses 1a and 1b were conducted on every tweet posted from the 22 accounts during those three months. In the final dataset, each tweet is the unit of analysis and there are 123,770 total tweets. In sum, for each tweet posted from the 22 news outlets, the dataset includes the following variables:

Date. This is the date the tweet was posted. There are 89 possible dates within this sample from the respective months of February, June, and August in 2015.

News outlet. This is the individual news outlet that posted each tweet.

Ideology of news outlet. There are three categories of political ideology: non-partisan, liberal, and conservative. Each tweet is assigned to a category based on the news outlet from which it originated. The content of the tweet may or may not be consistent with the new outlet’s ideological categorization. For example, the content of a specific tweet posted by Fox News could be politically neutral, but all tweets from this outlet will be categorized as coming from a conservative news outlet.

Number of followers. This is the number of followers the account had on the day the tweet was posted. The number of followers for each day was collected at 11:59 pm of that day. It is also worth noting that the individual followers for each outlet are not mutually exclusive. An individual may be a follower of two or more of the news outlets included in this sample.

Retweets. This is the number of retweets each posted tweet receives. A “retweet” is a particular function in Twitter that involves sharing of someone else’s posted tweet with one’s own followers. The number of retweets received by any individual tweet in this sample ranged from 0 to 39,160 (M = 59.94, SD = 230.30).

Replies. This is the number of replies each tweet posted by a news outlet receives. Like retweets, a reply is a particular function within the Twitter interface that allows users to reply to a specific tweet posted by another user. Here, the number of replies refers to the number of replies each tweet posted by a news outlet receives, ranging from 0 to 2253 (M = 10.82, SD = 24.79). Information about the total number of tweets, retweets, and replies for each outlet is in .

Table 2. Total numbers of tweets, retweets, and replies by news outlet.

Emotion Sample

To examine Hypotheses 2 and 3, it was necessary to code the tweets for the presence of specific, discrete emotions of anger, anxiety, and enthusiasm. In this case, another sample of tweets was collected from the same news outlets used in the first sample. This second sample included only tweets related to three specific political events. For each topic, I looked at messages shared within a 40-day period: 10 days before and 30 days after the event. The first event is the announcement of President Obama’s executive action on immigration in November 2014, which protected undocumented immigrants from deportation and helped them to get permits to legally work in the United States. The second event is the announcement of the ban on hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, in New York State in December 2014. The final event is the announcement of the Supreme Court’s decision on the rights of LGTB individuals to marry in the United States in June 2015.

Looking at specific events allows for consistency of topics across all news outlets, which makes it easier to code for discrete emotions, for both the human coders and the computer algorithm. It also provides more context, making it easier to conceptually compare and make sense of results across outlets with different political orientations. I used three Boolean search strings of terms relevant to these events. The searches were also limited to include only tweets posted by the same news outlets used in the first sample of this study, and the retweets of those tweets posted by the included news outlets. The search resulted in 1348 tweets posted by the 22 news media outlets and 290,560 tweets that are retweets of those news outlets. It is also worth noting that when users retweet information, they have the option to add a comment on the original posted tweet, which could impact whether or not the tweet was coded as expressing anger, anxiety, enthusiasm, or emotionally neutral. The analyses here do not distinguish between retweets that have comments and retweets that do not. However, in randomly sampling 100 retweets of each of the three events, for 300 retweets total, only 38 (12.6%) of the retweets contained any additional comment, suggesting the majority of retweets in the sample do not contain additional comments.

From here, the Forsight algorithm was trained to code both the tweets posted by news outlets and their retweets, according to the discrete emotion expressed in the content of the message. I conducted the algorithmic training, coding messages for the presence of anger, anxiety, enthusiasm, and emotionally neutral messages according to the following definitions of discrete emotions. Anger is a negative emotion that is experienced when people perceive that their goals have been blocked or that some unfairness or injustice has occurred. It is associated with taking actions aimed to punish the perceived perpetrators of the injustice (Lazarus Citation1991; Nabi Citation2003). Tweets were coded as expressing anger if the content indicated that there is an injustice or violation in a situation or that a person’s or party’s goals have been thwarted or blocked (Lazarus Citation1991; Nabi Citation1999). Anxiety, like anger, is a negative emotion that is experienced when people perceive a threat or encounter novel or unknown stimuli (Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Citation2000). Tweets were coded as expressing anxiety if the content indicated that there is a potential threat to one’s goals or if it expressed uncertainty (Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Citation2000; Valentino et al. Citation2011). Enthusiasm is a positive, approach emotion experienced when people perceive that they are progressing toward a goal in a manner that is better or quicker than expected (Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Citation2000; Valentino et al. Citation2011). Tweets were coded as expressing enthusiasm if the content indicated that one was progressing toward a desired goal (Brader Citation2006; Lazarus Citation1991). Tweets that expressed no discernable emotion were coded as emotionally neutral. See Appendix Bfor the complete codebook.

After the training was complete, the algorithm coded the remaining tweets and retweets. To assess the reliability of the coding scheme and the algorithm’s coding, tests of intercoder reliability were conducted. Once the algorithm coded all the tweets, a random sample of 50 tweets related to each of the three events was collected, for a total of 150 tweets. The codebook was shared with three independent coders, and they coded this sample of 150 tweets. The reliability among the human coders and the algorithm resulted in a Krippendorf’s alpha of 0.78. More information about how the sample was selected and coded can be found in online Appendix A.

Results

News Outlet Results

Hypothesis 1a referred to the differences in the number of retweets among ideologically different news outlets. A one-way ANOVA, with the ideology of the news outlet as the independent variable and the number of retweets as the dependent variable, shows that tweets posted by partisan news outlets were retweeted more than tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets, F(2, 123,767) = 67.34, p < 0.000. The post-hoc Bonferroni planned comparison analyses were all significant (p < 0.000). Tweets posted by liberal news outlets were retweeted (M = 67.69, SD = 226.50) more than tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets (M = 50.51, SD = 281.20), as were tweets posted by conservative news outlets (M = 61.83, SD = 119.44). Tweets posted by liberal news outlets were also retweeted more than tweets posted by conservative news outlets (p < 0.000). Because the sample is so large, it is likely that any differences would be found to be statistically significant. Looking at the results in terms of percentages shows that the differences are meaningful in addition to being statistically significant. On average, tweets posted by liberal news outlets received 36% more retweets than tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets, and 9.7% more retweets than tweets posted by conservative news outlets. Tweets from conservative news outlets received 24% more retweets than tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets.

Hypothesis 1b referred to the differences in the number of replies among politically different news outlets. A one-way ANOVA, with the ideology of the news outlet as the independent variable and the number of replies as the dependent variable, demonstrates that tweets posted by partisan news were replied to more than tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets, F(2, 123,767) = 1362.73, p < 0.000. The post-hoc Bonferroni planned comparison analyses were all significant (p < 0.000). Tweets posted by conservative news outlets (M = 17.10, SD = 35.72) were replied to more than tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets (M = 7.56, SD = 22.43), as were tweets posted by liberal news outlets (M = 10.20, SD = 17.19). Tweets posted by conservative news outlets were also replied to more than tweets posted by liberal news outlets (p < 0.000). The percentages of these results show that the differences are also meaningful. On average, tweets posted by conservative news outlets received 112.5% more replies than tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets, and 70% more replies than tweets posted by liberal news outlets. Tweets posted by liberal news outlets received 25% more replies than tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets.

These results demonstrate that tweets posted by partisan news outlets generally received more retweets and replies than tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets, supporting Hypotheses 1a and 1b. To ensure these results are not simply reflective of the number of followers each outlet has, nor driven by a few outlets with large numbers of followers, I conducted two supplemental analyses. The first analyses used the number of retweets and replies per follower as the dependent variable, and the second used the same analyses but removed the outlet with the highest number of followers in each ideological category. For both analyses, the results were consistent with the findings presented here, partisan news media were retweeted and replied to more than non-partisan news media. See Appendix C for these supplemental analyses .

Emotion Results

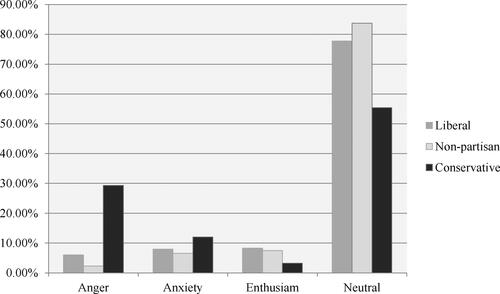

Hypothesis 2 refers to the emotions expressed in tweets posted by news outlets, positing that partisan news outlets would post more tweets that express anger, anxiety, and enthusiasm than non-partisan news outlets. In total, non-partisan news outlets posted 442 tweets about the three events, of which 16% expressed one of the three coded emotions. Liberal news outlets posted 565 tweets, of which 22% expressed emotion. Conservative news outlets posted 341 tweets, of which 45% expressed emotion. shows the total number of tweets posted by liberal, conservative, and non-partisan news outlets by topic and emotion. Liberal, conservative, and non-partisan news outlets all posted more tweets that were emotionally neutral than tweets that expressed any of the three coded emotions (see ), but partisan news outlets posted more tweets that express emotion compared to non-partisan news outlets. A chi-square test shows that liberal news outlets posted tweets that express emotion more frequently than non-partisan news outlets (χ2 = 5.67, df = 1, p < 0.05), as did conservative news outlets (χ2 = 75.40, df = 1, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 2. Conservative news outlets also posted tweets that express emotion more frequently than liberal news outlets (χ2 = 49.60, df = 1, p < 0.01).

Table 3. Total number of tweets posted by news outlets by emotion expressed and topic.

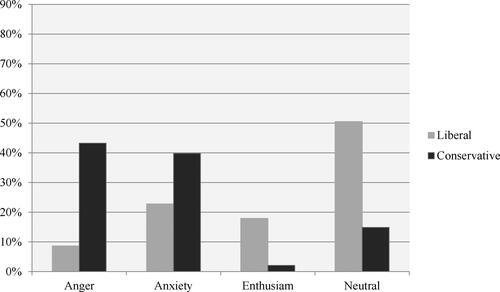

Hypothesis 3 posits that retweets of partisan news will be more likely to express anger, anxiety, or enthusiasm than to be emotionally neutral. The total number of retweets of partisan news can be found in . Emotionally neutral tweets from liberal news outlets were more likely to be shared than tweets that expressed emotion (χ2 = 12.17, df = 1, p < 0.01), with just over 50% of the retweets expressing no emotion. Tweets that express emotion from conservative news outlets were more likely to be shared than tweets that expressed no emotion (χ2 = 45,608.92, df = 1, p < 0.01), with 85% of the retweets expressing emotion. The proportion of emotion expressed in the retweets of partisan news is depicted in . In this case, Hypothesis 3 was supported for conservative news outlets only, but not for liberal news outlets.

Table 4. Total number of retweets of partisan news outlets by emotion expressed and topic.

The results show that the majority of messages posted by news outlets themselves are emotionally neutral, but partisan news outlets do post more tweets that express emotion than non-partisan news outlets, supporting Hypothesis 2. When looking at the retweets of partisan news outlets, retweets were more likely to express emotion but this finding was limited to conservative news only, providing partial support for Hypothesis 3.

Discussion

This study examined how individuals engage with news media content by specifically looking at whether partisan news media and emotional news content are amplified on Twitter. The results showed that tweets posted by partisan news media were on average retweeted more and replied to more than tweets posted by non-partisan news media. In other words, news users share and respond to partisan news media significantly more than they share and respond to non-partisan news media, amplifying partisan news media in social media networks.

The social amplification of partisan news media has potential consequences for the information environment. At a societal level, partisan news can have negative democratic effects on audiences by increasing polarization and feelings of dislike and distrust of those with opposing views (Garrett et al. Citation2014; Levendusky Citation2013; Stroud Citation2010). It may also be that partisan news content in social media has downstream effects by also influencing those who are not direct followers and audiences for partisan news media. At an individual level, people attend to, learn from, and trust political news shared by their peers, and this information can influence political behaviors (Anspach Citation2017; Bode Citation2016; Sterrett et al. Citation2019; Turcotte et al. Citation2015). This suggests news information shared by peers may have important effects on individuals especially if much of that information is partisan or biased toward one ideology over another.

While this study was not designed to test the effects of partisan information in social media, it does show how people might ultimately be exposed to partisan information without actively seeking or selecting it. Exposure to political news is the result of multiple interested entities (Thorson and Wells Citation2016); if news users interact with partisan news more frequently, these interactions may be influencing algorithmic rankings of news outlets and news stories in ways that increase the likelihood that others will see the news item (Zhang et al. Citation2018). The results demonstrate that partisan news media may have a disproportionate influence in a social media environment compared to non-partisan news media, both in terms of what news media people see in their personal networks and how algorithms respond to engagement with social media posts.

It is important to note that these data did not include information about who is sharing or replying to news. It is not possible to know whether the individuals are conservative or liberal or even whether they follow the news organization with which they are engaging. However, partisan news clearly elicits more responses from news users than does non-partisan news.

Future research should explore who might be driving this engagement with partisan news in social media. Research suggests that partisans tend to share information that supports their ideological worldview (Shin and Thorson Citation2017), though there is some evidence that liberals are more likely to disseminate cross-ideological information in social media than are conservatives (Barberá et al. Citation2015). Additionally, in the current media environment, politically motivated actors frequently employ bots to share and spread information favorable to one party or another (Bennett and Livingston Citation2018; Howard, Woolley, and Calo Citation2018). These data were collected before the 2016 US presidential election was underway, and these data only refer to tweets shared by professional news organizations, but it is possible that politically motivated bots were employed in amplifying specific partisan content. In any case, there are still many questions about who is driving the amplification of partisan news and what might be their motivations.

The results also demonstrate that the emotions expressed in news content can influence what political news information spreads in a social media environment. While the majority of tweets posted by all news outlets in this sample were emotionally neutral, partisan news outlets generally posted more tweets that expressed emotions compared to tweets posted by non-partisan news outlets. Emotional tweets posted by conservative news organizations tended to be shared more than tweets which expressed no emotion. The retweets of conservative news outlets more frequently expressed anger (43.28%) and anxiety (39.79%), while the retweets of liberal news outlets were mostly emotionally neutral (50.53%) (see ).

These findings do not necessarily suggest that conservative news media or those who share conservative news media are generally more angry or anxious; though there is evidence to suggest both that conservative news media purposefully cultivate anger and anxiety (Berry and Sobieraj Citation2013) and that their more conservative audiences are particularly drawn to that anger and anxiety (Young Citation2019). However, the results should be understood within the context of the events and issues used within the study. Of the events examined, the outcomes generally favored a politically liberal ideology or the goals of the Democratic Party. Such events might understandably lead to more anger and anxiety from conservative news media and their users. Because anger is an approach emotion associated with retributive action, it is reasonable that anger would spur information-sharing, as people seek to highlight injustices or punish the object of their anger. These data do not account for the emotion of the individual sharing the tweet, but pro-attitudinal news use does tend to increase anger in individuals, while the use of non-partisan news does not (Hasell and Weeks Citation2016; Lu and Lee Citation2019; Wojcieszak et al. Citation2016). Conservative news that expressed anxiety was also shared disproportionately more compared to what was posted. Studies have not found the same effect of pro-attitudinal news use on anxiety (Hasell and Weeks Citation2016; Wojcieszak et al. Citation2016), but there is evidence that fear in news information can increase the likelihood that it will be shared (Berger and Milkman Citation2012; Lu and Lee Citation2019). Further, anxiety is associated with information seeking (MacKuen et al. Citation2010; Valentino et al. Citation2008), and it may be that sharing messages in social media serves as a form of information seeking if individuals are seeking reassurance or explanations of events. It is also known that negatively valenced emotions in news media tend to elicit stronger responses (Soroka, Fournier, and Nir Citation2019; Soroka and McAdams Citation2015), and that the strength of emotion can increase information-sharing (Berger and Milkman Citation2012). Additionally, research has shown that negative news on Twitter is associated with increased anger (Park Citation2015) and that emotions expressed on Twitter tend to cluster in politically like-minded networks (Himelboim et al. Citation2016). Moving forward, future research could examine events in which the outcomes favor a conservative ideology or Republican Party position to understand if retweets of conservative news generally express more anger and anxiety, or if the particular context of the event matters.

These findings have implications for journalism and news media organizations as well. The asymmetries between what content is posted on Twitter and what content receives the most engagement from users, may—consciously or unconsciously—influence priorities of news organizations. Likes, shares, and replies provide quantified forms of feedback that journalists and editors use to inform future reporting practices (Hanusch and Tandoc Citation2019). As news organizations face more competition for increasingly smaller profit margins, some may seek to increase engagement and clicks by posting news content to which people are more likely to share and respond (Lee and Tandoc Citation2017). This could result in even more partisan, more emotional news content in the social media environment. Further, as journalists frequently use discussions and trending topics on Twitter as indicative of public opinion and sentiment (Anstead and O’Loughlin Citation2015; McGregor Citation2019), it may also lead them to perceive that audiences are also more partisan and emotional.

There are some other important limitations to this study that have not been discussed. First, the data reflect only a sample of news organizations that are influential on Twitter. More or different sources could conceivably lead to different results, although the study was designed to capture a range of influential political news sources and the results are consistent with theoretical expectations. Future research could examine a wider array of news sources. Additionally, these data were collected in a US context and may not applicable to patterns of news engagement in other countries. Finally, social media develop and change, and thus it may be that the patterns of usage, and the users themselves, will change over time. As noted, this study is not able to determine who these users are or how they might habitually relate to, interact with, or consume news media.

Still, there are strong justifications for why emotional, partisan news might be shared more widely in social media. Partisan news media tend to emphasize the negative aspects of politics, especially those of the opposing party (Berry and Sobieraj Citation2013; Smith and Searles Citation2014), and people attend to and react more strongly to negative news (Soroka, Fournier, and Nir Citation2019; Soroka and McAdams Citation2015). Further, politics can feel more personal and more emotional on social media (Wagner and Boczkowski Citation2019), and partisans tend to have the strongest emotional responses to political information (Neuman, Marcus, and MacKuen Citation2018). As scholars continue to examine the effects of partisan news media, it is increasingly important to examine how those effects may be socially amplified to a broader population.

rdij_a_1831937_sm8290.docx

Download MS Word (150.2 KB)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Bruce Bimber, Andrew Flanagin, and Miriam Metzger for their support and comments on this project. I would also like to thank Brian Weeks for his comments and insights, and the anonymous reviewers, whose thoughtful feedback very much improved this study.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Al-Rawi, Ahmed. 2019. “Viral News on Social Media.” Digital Journalism 7 (1): 63–79.

- Anspach, Nicolas M. 2017. “The New Personal Influence: How Our Facebook Friends Influence the News We Read.” Political Communication 34 (4): 590–606.

- Anstead, Nick, and Ben O’Loughlin. 2015. “Social Media Analysis and Public Opinion: The 2010 UK General Election.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20 (2): 204–220.

- Barberá, Pablo, John T. Jost, Jonathan Nagler, Joshua A. Tucker, and Richard Bonneau. 2015. “Tweeting from Left to Right: Is Online Political Communication More than an Echo Chamber?” Psychological Science 26 (10): 1531–1542.

- Barberá, Pablo, and Gonzalo Rivero. 2015. “Understanding the Political Representativeness of Twitter Users.” Social Science Computer Review 33 (6): 712–729.

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Steven Livingston. 2018. “The Disinformation Order: Disruptive Communication and the Decline of Democratic Institutions.” European Journal of Communication 33 (2): 122–139.

- Berger, Jonah, and Katherine L. Milkman. 2012. “What Makes Online Content Viral?” Journal of Marketing Research 49 (2): 192–205.

- Berry, Jeffrey M., and Sarah Sobieraj. 2013. The Outrage Industry: Political Opinion Media and the New Incivility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Blanton, Hart, Erin Strauts, and Marisol Perez. 2012. “Partisan Identification as a Predictor of Cortisol Response to Election News.” Political Communication 29 (4): 447–460.

- Bode, Leticia. 2016. “Political News in the News Feed: Learning Politics from Social Media.” Mass Communication and Society 19 (1): 24–48.

- Brader, Ted. 2006. Campaigning for Hearts and Minds: How Emotional Appeals in Political Ads Work. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Bright, Jonathan. 2016. “The Social News Gap: How News Reading and News Sharing Diverge.” Journal of Communication 66 (3): 343–365.

- Budak, Ceren, Sharad Goel, and Justin M. Rao. 2016. “Fair and Balanced? Quantifying Media Bias through Crowdsourced Content Analysis.” Public Opinion Quarterly 80 (S1): 250–271.

- Chadwick, Andrew. 2013. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Coe, Kevin, David Tewksbury, Bradley J. Bond, Kristin L. Drogos, Robert W. Porter, Ashley Yahn, and Yuanyuan Zhang. 2008. “Hostile News: Partisan Use and Perceptions of Cable News Programming.” Journal of Communication 58 (2): 201–219.

- Druckman, James N., Matthew S. Levendusky, and Audrey McLain. 2018. “No Need to Watch: How the Effects of Partisan Media Can Spread via Interpersonal Discussions.” American Journal of Political Science 62 (1): 99–112.

- Faris, Robert, Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. “Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election.” Berkman Klein Center Research Publication No. 6. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3019414

- Fletcher, Richard, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. “Are People Incidentally Exposed to News on Social Media? A Comparative Analysis.” New Media & Society 20 (7): 2450–2468.

- Garrett, R. Kelly, Shira Dvir Gvirsman, Benjamin K. Johnson, Yariv Tsfati, Rachel Neo, and Aysenur Dal. 2014. “Implications of Pro- and Counterattitudinal Information Exposure for Affective Polarization.” Human Communication Research 40 (3): 309–332.

- Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, Brian Weeks, and Alberto Ardèvol-Abreu. 2017. “Effects of the News-Finds-Me Perception in Communication: Social Media Use Implications for News Seeking and Learning about Politics.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 22 (3): 105–123.

- Graber, Doris A. 1996. “Say It with Pictures.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 546 (1): 85–96.

- Hanusch, Folker, and Edson C. Tandoc Jr. 2019. “Comments, Analytics, and Social Media: The Impact of Audience Feedback on Journalists’ Market Orientation.” Journalism 20 (6): 695–713.

- Hasell, Ariel, and Brian E. Weeks. 2016. “Partisan Provocation: The Role of Partisan News Use and Emotional Responses in Political Information Sharing in Social Media.” Human Communication Research 42 (4): 641–661.

- Himelboim, Itai, Kaye D. Sweetser, Spencer F. Tinkham, Kristen Cameron, Matthew Danelo, and Kate West. 2016. “Valence-Based Homophily on Twitter: Network Analysis of Emotions and Political Talk in the 2012 Presidential Election.” New Media & Society 18 (7): 1382–1400.

- Howard, Philip N., Samuel Woolley, and Ryan Calo. 2018. “Algorithms, Bots, and Political Communication in the US 2016 Election: The Challenge of Automated Political Communication for Election Law and Administration.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 15 (2): 81–93.

- Kalsnes, Bente, and Anders Olof Larsson. 2018. “Understanding News Sharing across Social Media: Detailing Distribution on Facebook and Twitter.” Journalism Studies 19 (11): 1669–1688.

- Kilgo, Danielle K., Kyser Lough, and Martin J. Riedl. 2020. “Emotional Appeals and News Values as Factors of Shareworthiness in Ice Bucket Challenge Coverage.” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 267–286.

- Kim, Yonghwan, Hsuan-Ting Chen, and Homero Gil de Zúñiga. 2013. “Stumbling upon News on the Internet: Effects of Incidental News Exposure and Relative Entertainment Use on Political Engagement.” Computers in Human Behavior 29 (6): 2607–2614.

- Kümpel, Anna Sophie, Veronika Karnowski, and Till Keyling. 2015. “News Sharing in Social Media: A Review of Current Research on News Sharing Users, Content, and Networks.” Social Media + Society 1 (2): 1–14.

- Lazarus, Richard S. 1991. “Cognition and Motivation in Emotion.” The American Psychologist 46 (4): 352–367.

- Lecheler, Sophie. 2020. “The Emotional Turn in Journalism Needs to Be about Audience Perceptions: Commentary-Virtual Special Issue on the Emotional Turn.” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 287–291.

- Lee, Eun-Ju, and Edson C. Tandoc Jr. 2017. “When News Meets the Audience: How Audience Feedback Online Affects News Production and Consumption.” Human Communication Research 43 (4): 436–449.

- Leeper, Thomas J. 2014. “The Informational Basis for Mass Polarization.” Public Opinion Quarterly 78 (1): 27–46.

- Levendusky, Matthew. 2013. “Partisan Media Exposure and Attitudes toward the Opposition.” Political Communication 30 (4): 565–581.

- Lu, Yanqin, and Jae Kook Lee. 2019. “Partisan Information Sources and Affective Polarization: Panel Analysis of the Mediating Role of Anger and Fear.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96 (3): 767–783.

- Lukito, Josephine, Jiyoun Suk, Yini Zhang, Larissa Doroshenko, Sang Jung Kim, Min-Hsin Su, Yiping Xia, Deen Freelon, and Chris Wells. 2020. “The Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing: How Russia’s Internet Research Agency Tweets Appeared in US News as Vox Populi.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 25 (2): 196–216.

- MacKuen, Michael, Jennifer Wolak, Luke Keele, and George E. Marcus. 2010. “Civic Engagements: Resolute Partisanship or Reflective Deliberation.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (2): 440–458.

- Marcus, George E., Michael MacKuen, and W. Russell Neuman. 2011. “Parsimony and Complexity: Developing and Testing Theories of Affective Intelligence.” Political Psychology 32 (2): 323–336.

- Marcus, George E., W. Russell Neuman, and Michael MacKuen. 2000. Affective Intelligence and Political Judgement. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- McGregor, Shannon C. 2019. “Social Media as Public Opinion: How Journalists Use Social Media to Represent Public Opinion.” Journalism 20 (8): 1070–1086.

- Mourão, Rachel Reis. 2015. “The Boys on the Timeline: Political Journalists’ Use of Twitter for Building Interpretive Communities.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 16 (8): 1107–1123.

- Nabi, Robin. 1999. “A Cognitive-Functional Model for the Effects of Discrete Negative Emotions on Information Processing, Attitude Change, and Recall.” Communication Theory 9 (3): 292–320.

- Nabi, Robin. 2003. “Exploring the Framing Effects of Emotion: Do Discrete Emotions Differentially Influence Information Accessibility, Information Seeking, and Policy Preference.” Communication Research 30 (2): 224–247.

- Neuman, W. Russell, George E. Marcus, and Michael B. MacKuen. 2018. “Hardwired for News: Affective Intelligence and Political Attention.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 62 (4): 614–635.

- O’Reilly, Bill. 2006. Culture Warrior. New York, NY: Broadway Books.

- Park, Chang S. 2015. “Applying ‘Negativity Bias’ to Twitter: Negative News on Twitter, Emotions, and Political Learning.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 12 (4): 342–359.

- Peters, Chris. 2011. “Emotion Aside or Emotional Side? Crafting an “Experience of Involvement” in the News.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 12 (3): 297–316.

- Pew Research Center. 2013. “The Role of News on Facebook: Common Yet Incidental.” http://www.journalism.org/2013/10/24/the-role-of-news-on-facebook/

- Pew Research Center. 2014. “Political Polarization and Media Habits.” http://www.journalism.org/2014/10/21/political-polarization-media-habits/

- Prior, Markus. 2013. “Media and Political Polarization.” Annual Review of Political Science 16 (1): 101–127.

- Shin, Jieun, and Kjerstin Thorson. 2017. “Partisan Selective Sharing: The Biased Diffusion of Fact-Checking Messages on Social Media.” Journal of Communication 67 (2): 233–255.

- Smith, Glen, and Kathleen Searles. 2014. “Who Let the (Attack) Dogs out? New Evidence for Partisan Media Effects.” Public Opinion Quarterly 78 (1): 71–99.

- Sobieraj, Sarah, and Jeffrey M. Berry. 2011. “From Incivility to Outrage: Political Discourse in Blogs, Talk Radio, and Cable News.” Political Communication 28 (1): 19–41.

- Soroka, Stuart, Patrick Fournier, and Lilach Nir. 2019. “Cross-National Evidence of a Negativity Bias in Psychophysiological Reactions to News.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116 (38): 18888–18892.

- Soroka, Stuart, and Stephen McAdams. 2015. “News, Politics, and Negativity.” Political Communication 32 (1): 1–22.

- Sterrett, David, Dan Malato, Jennifer Benz, Liz Kantor, Trevor Tompson, Tom Rosenstiel, Jeff Sonderman, and Kevin Loker. 2019. “Who Shared It? Deciding What News to Trust on Social Media.” Digital Journalism 7 (6): 783–801.

- Stieglitz, Stefan, and Linh Dang-Xuan. 2013. “Emotions and Information Diffusion in Social Media—Sentiment of Microblogs and Sharing Behavior.” Journal of Management Information Systems 29 (4): 217–248.

- Stroud, Natalie J. 2010. “Polarization and Partisan Selective Exposure.” Journal of Communication 60 (3): 556–576.

- Stroud, Natalie J. 2011. Niche News: The Politics of News Choice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Tewksbury, David, Andrew J Weaver, and Brett D Maddex. 2001. “Accidentally Informed: Incidental News Exposure on the World Wide Web.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 78 (3): 533–554. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900107800309.

- Thorson, Kjerstin, and Chris Wells. 2016. “Curated Flows: A Framework for Mapping Media Exposure in the Digital Age.” Communication Theory 26 (3): 309–328.

- Trilling, Damian, Petro Tolochko, and Björn Burscher. 2017. “From Newsworthiness to Shareworthiness: How to Predict News Sharing Based on Article Characteristics.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 94 (1): 38–60.

- Turcotte, Jason, Chance York, Jacob Irving, Rosanne M. Scholl, and Raymond J. Pingree. 2015. “News Recommendations from Social Media Opinion Leaders: Effects on Media Trust and Information Seeking.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20 (5): 520–535.

- Valentino, Nicholas A., Ted Brader, Eric W. Groenendyk, Krysha Gregorowicz, and Vincent L. Hutchings. 2011. “Election Night’s Alright for Fighting: The Role of Emotions in Political Participation.” The Journal of Politics 73 (1): 156–170.

- Valentino, Nicholas A., Vincent L. Hutchings, Antoine J. Banks, and Anne K. Davis. 2008. “Is a Worried Citizen a Good Citizen? Emotions, Political Information Seeking, and Learning via the Internet.” Political Psychology 29 (2): 247–273.

- Vargo, Chris J., and Lei Guo. 2017. “Networks, Big Data, and Intermedia Agenda Setting: An Analysis of Traditional, Partisan, and Emerging Online US News.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 94 (4): 1031–1055.

- Wagner, María Celeste, and Pablo J. Boczkowski. 2019. “Angry, Frustrated, and Overwhelmed: The Emotional Experience of Consuming News about President Trump.” Journalism 1–19.doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919878545

- Wahl-Jorgensen, Karin. 2019. Emotions, Media and Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, Karin. 2020. “An Emotional Turn in Journalism Studies?” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 175–194.

- Weber, Christopher. 2013. “Emotions, Campaigns, and Political Participation.” Political Research Quarterly 66 (2): 414–428.

- Weeks, Brian E., Alberto Ardèvol-Abreu, and Homero Gil de Zúñiga. 2017. “Online Influence? Social Media Use, Opinion Leadership, and Political Persuasion.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 29 (2): 214–239.

- Weeks, Brian E., Daniel S. Lane, Dam Hee Kim, Slgi S. Lee, and Nojin Kwak. 2017. “Incidental Exposure, Selective Exposure, and Political Information Sharing: Integrating Online Exposure Patterns and Expression on Social Media.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 22 (6): 363–379.

- Wojcieszak, Magdalena, Bruce Bimber, Lauren Feldman, and Natalie Jomini Stroud. 2016. “Partisan News and Political Participation: Exploring Mediated Relationships.” Political Communication 33 (2): 241–260.

- Young, Danna G. 2019. Irony and Outrage: The Polarized Landscape of Rage, Fear, and Laughter in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Zhang, Yini, Chris Wells, Song Wang, and Karl Rohe. 2018. “Attention and Amplification in the Hybrid Media System: The Composition and Activity of Donald Trump’s Twitter following during the 2016 Presidential Election.” New Media & Society 20 (9): 3161–3182.