Abstract

News organizations increasingly depend on subscriptions, donations, memberships and audience engagement figures, calling up the question of what kind of journalism audiences would find so valuable that they might be willing to pay for it, in money or attention. To answer this question, I have fleshed out the concept of Valuable Journalism by performing a meta-analysis of the results of twenty-two audience research projects (2005–2020) involving 3068 informants. By focussing on what audiences experience as valuable journalism, rather than on its content or approach, I will demonstrate how Valuable Journalism crystallized over the years into three key experiences: Learning something new, Getting recognition and Increasing mutual understanding. In the final part of the paper, I address the challenges raised by Valuable Journalism for practicing journalists and journalism scholars.

What do you experience as valuable journalism? In countless variations this question has been asked to more than 3000 informants over the last fifteen years (see the Appendix). Since the digitalization of journalism caused news organizations increasingly to depend on subscriptions, donations, memberships and audience engagement figures, the question of what kind of journalism audiences would find so valuable that they might be willing to pay for it, in money or attention, has become ever more urgent. Current concepts assessing the news—quality journalism and popular journalism—may insufficiently cover what news users really appreciate. Early on it became clear that considering particular content important—quality journalism or public interest journalism—was not always an accurate indicator of actual use. Audiences tend to agree with the professionals on quality journalism’s norms and values and thus on what counts as good journalism, even though they may not consume it (Gil de Zúñiga and Hinsley Citation2013; Kunelius Citation2006; Van Der Wurff and Schoenbach Citation2014; Wendelin, Engelmann, and Neubarth Citation2017). On the other hand, the popularity of news seldom reflects actual user satisfaction (Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer Citation2017). Trending topics, top stories, clicks or most read do not necessarily indicate what news users appreciate the most (frequency fallacy). Likewise, the news items on which they spend most time do not automatically coincide with people’s most satisfying news experience (duration fallacy) (see Costera Meijer and Groot Kormelink Citation2021). Whether people will actually feel informed depends upon their situation, their specific mood, the qualities of the device or platform, the time of the day and so on. In other words, it may differ from one person to the next which modalities, topics, genres or approaches of journalism are experienced as valuable. Yet, as I will argue in this article, the particular sensation inherent in experiencing journalism as valuable appears to be articulated in similar terms.

The digitalization of journalism constitutes another reason to look for a concept that captures what audiences really value. The easy (or even free) access to news and its distribution through social media has been held responsible for societal problems such as fragmentation and polarization (Webster and Ksiazek Citation2012). Although journalism professionals and scholars came up with inspiring solutions, including public journalism (Glasser Citation1999) and constructive journalism (Hermans and Gyldensted Citation2019), they are designed to guide professional practices and standards rather than increase our understanding of the public's experiences.

These reasons indicate a need for a conceptual framework beyond the normative concept of “quality journalism” (Anderson, Williams, and Ogola Citation2013; Meier Citation2019; Picard Citation2000), its commercial counterpart “popular journalism” (Conboy Citation2002; Zelizer and Allan Citation2010) or specific journalistic approaches and genres. Consequently, such a concept should not be a priori reducible to people’s views or opinions about quality, certain news content (beats, genres, approaches), frequency of use or time spent. This is why I employed the notion of Valuable Journalism as an empirical, non-normative, sensitizing concept (Bowen Citation2006) to study what audiences actually experience as worthwhile.

As of 2008 we have explored the usefulness of the concept of Valuable Journalism in order to deepen our perception, analysis and understanding of how and when people actually used and articulated journalism as a sensory experience which truly enriched their everyday life. Valuable Journalism may not be unique to digital journalism, but it may provide its conditions, as I will explain in “Audience Attentiveness as Professional Practice” section below.

To discuss the notion of Valuable Journalism in more detail, this article comprises six sections. The first section outlines how to make sense of Valuable Journalism at a conceptual level. The second section explains the research approach. The third section analyses what our informants have actually experienced and articulated as such journalism over the years. Next, the fourth section explores how Valuable Journalism might be profitable for news organizations, while the fifth section examines how Valuable Journalism can be made relevant for journalists. In this context I argue for Audience Attentiveness as a guiding practice, inviting reflection on six professional virtues. In the final section I discuss how journalism scholars may counter the challenges raised by Valuable Journalism in future research.

Making Sense of Valuable Journalism

To make sense conceptually of what audiences experience as valuable journalism, journalism scholarship offers a limited repertoire. First, in the context of journalism, the notion of value has commonly been discussed in terms of newsworthiness: “news is a hybrid good, with both a price-tag and a symbolic/public worth” (De Maeyer Citation2020:124). The professional context, in which values are being attached to the product, makes them less suitable for operationalizing their impact as valuable user experiences. A second shortcoming pertains to the normative nature of several concepts intended to encourage journalists to reckon with the interests of the public. Dreher (Citation2009) and Wasserman (Citation2013) both emphasize how an “ethics of listening” can strengthen the voice of the people less heard in society. Silverstone (Citation2007) has called this ethos “media hospitality.” Listening and hospitality appear to be very relevant for improving the representational quality of journalism, because they encourage journalists to provide a platform for voices less heard or even invisible in mainstream journalism. Still, how precisely this fuller and more layered picture of society is meeting the needs and demands of citizens is still unclear.

Third, although the framework of audience engagement is empirical, it tends to be used for quantifying popularity, and this may not mirror what audiences actually value (see Costera Meijer and Groot Kormelink Citation2021, chapters 3 & 4).

A fourth limitation pertains to the applied character of the notions of value and experience in particular studies addressing the value of journalism from a user perspective. In a previous study (Costera Meijer Citation2013a) I suggested how news users value journalism more when it made better use of their individual and collective wisdom and when it took their concerns and views into account. News users also appreciate a captivating presentation, a gratifying narrative and layered information. But what constitutes a gratifying experience and which layers need to be addressed to truly satisfy people’s needs are issues which remained underconceptualized.

Finally, in this context, scholars have relied on the concept of “worthwhileness” over the years (Schrøder and Steeg Larsen Citation2010; Schrøder Citation2015). Referring to the outcome of a process of selection and calculation, “worthwhileness” involves weighing different options such as: is this content worth spending time on, is it affordable, does it fit the situation etcetera to determine “why some news media and not others are chosen to become parts of an individual’s news media repertoire” (Schrøder Citation2015: 63). Although this notion covers the cognitive process of news selection, it pays less attention to the experiential and emotional dimensions of news assessment.

These five limitations invite a look beyond Journalism Studies. Specifically, I will consider the potential merits here of Entertainment Studies, Narrative Studies and Human Computer Interaction studies (see Costera Meijer Citation2020a).

The formal definition of “user experience”—developed as product standard by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO DIS 9241-210, Citation2010)—may be more promising as conceptual tool because it emphasizes experience as an outcome of interaction rather than as a property of a product:

User experience includes all the user's emotions, beliefs, preferences, perceptions, physical and psychological responses, behaviours and accomplishments that occur before, during and after use. (.) User experience is a consequence of brand image, presentation, functionality, system performance, interactive behaviour and assistive capabilities of the interactive system, the user's internal and physical state resulting from prior experience, attitudes, skills and personality, and the context of use. (In Mirnig et al. Citation2015: 437)

Although this definition seems exhaustive in summing up the dimensions of user experience, it does not address the distinct sensation of a valuable news experience.

The dimension of value in a valuable user experience is better compared to “a meaningful media experience” (Oliver et al. Citation2018), a concept developed in entertainment research to describe “appreciation.” Appreciation is a more serious and lasting entertainment experience, involving less immediate and more reflexive gratification than media responses such as fun, relaxation, suspense or diversion, usually covered by the label “enjoyment” (Vorderer, Klimmt, and Ritterfeld Citation2004). Appreciation was first defined by Oliver and Bartsch (Citation2010: 76) as an “experiential state that is characterized by the perception of deeper meaning, the feeling of being moved, and the motivation to elaborate on thoughts and feelings inspired by the experience.” Appreciation was also linked to the sensation of experiencing an insight, (Bartsch and Hartmann Citation2017; Bartsch and Oliver Citation2011), a response motivated by a need to find truths, existential purposes or a meaning of life (Oliver and Raney Citation2011). As a reflective process it is characterized as “slower, more deliberative and interpretive” (Oliver and Bartsch Citation2010: 58). While fun is linked to recreation, “appreciation is linked to cognitive challenge and personal growth” (Bartsch and Hartmann Citation2017: 29). The concept of appreciation has also been explained in light of self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci Citation2000), as providing a means to satisfy fundamental human needs of autonomy, competence and social relatedness (Vorderer and Ritterfeld Citation2009). Although appreciation might be triggered through complex and challenging media content which may demand more effort in information processing, Roth et al. (Citation2018) suggest that people should be able to enjoy the media content in order to enable their appreciation.

Both the conceptual frameworks of user experience (HCI-studies) and appreciation (Entertainment and Narrative Studies) seem expedient to make further sense of Valuable Journalism as a range of appreciated subjective perceptions, reactions, sensations, emotions and feelings invoked by journalism in the user. In this article I explore whether it is possible to identify particular patterns or “key experiences” implied in the different variations in users’ articulations of value. How I addressed this concern is the topic of the next section.

Research Approach

The insights on Valuable Journalism presented here are based on a meta-analysis of twenty-two audience research projects (2004–2020, see the Appendix for overview). These projects captured people’s experience of Valuable Journalism by asking 3059 informants to supply concrete moments of news use which they experienced as enriching their lives. This group of informants covers a comprehensive spectrum in terms of age, gender, education and cultural background, and they were approached in various ways: through in-depth interviews, focus groups, street intercept interviews and (open-ended) surveys. Subsequently they were invited to explain what this experience meant to them. This article’s focus, then, is on making sense of the various articulations of these “enriching experiences” by using “Valuable Journalism” as a sensitizing concept. Sensitizing concepts, according to Charmaz (Citation2006),

offer ways of seeing, organizing, and understanding experience; they are embedded in our disciplinary emphases and perspectival proclivities. Although sensitizing concepts may deepen perception, they provide starting points for building analysis, not ending points for evading it. (p. 259)

The research presented here relied on different angles or lenses such as age (see Costera Meijer Citation2007), democracy (see Costera Meijer Citation2010), place as featured at the national, local and hyperlocal level (see Costera Meijer Citation2013b, Citation2020b, Citation2020c; Costera Meijer and Bijleveld Citation2016) and different devices or media such as television, newspapers, news apps and news sites (see Costera Meijer and Groot Kormelink Citation2021) to explore possible relative dimensions of Valuable Journalism.

Apart from relying on data from research I conducted earlier, I use data from master-level research which I supervised more recently and which pertains to the experience of truth, trust and distrust, people’s experience of representations of particular groups (Muslims, black people, supporters of populist parties), as well as studies of the avoidance and enjoyment of news use, including the experience of particular news genres: climate journalism, sports journalism, current affairs, political news and lifestyle journalism. In 2020 we also began to investigate why and when news users started to distrust “mainstream journalism” (their term), and this provided insights into people’s experience of and need for alternative news sources (see the Appendix for an overview of all research projects).

To identify the various experiential dimensions of Valuable Journalism, most of the research was grounded in a phenomenological approach (Wertz et al. Citation2011). Emphasizing people’s experiences of Valuable Journalism, instead of their opinions or views, is in line with the call by Oliver and Bartsch (Citation2010: 76) that “any such definition must resonate with empirical findings concerning how individuals ultimately experience their responses and the terms that they use to describe their experiences.” An additional reason for focussing on lived experience was tied to the fact that when asked for their opinion about news, informants tended to employ a limited (usually critical) repertoire. Inviting people to verbalize an experience, in particular one that was very much appreciated, encouraged them to find new words and concepts. Of course, informants still needed language to articulate an experience, but their choice of words to make sense of their appreciation appeared to be less predetermined.

To better understand which experiences were regarded as key to Valuable Journalism, I paid close attention to underlying patterns in language use as well as to variations in the ways these experiences were articulated, both within and across the transcripts of the research interviews, focus groups and street intercept interviews (cf. Costera Meijer Citation2016; Thomas Citation2006; Wetherell and Potter Citation1988). Informed by the protocol of grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss Citation1990), I looked for theoretical concepts which aptly named the user experiences after completing the research. This inductive approach to find so-called “key experiences” inspired me to use crystallization as methodological approach (see Richardson Citation2000), aiming to find new facets of valuable journalism and thus new dimensions to make sense of a valuable news experience until reaching the point of theoretical saturation (Lindlof Citation1995).

People’s Articulation of Their Experience of Valuable Journalism

Our informants agreed that journalism, in order to be valuable, should first of all be trustworthy and truthful. In the words of one informant: “If news cannot be trusted, is there anything left to be trusted?” However, from an audience perspective, truth and trust can cover various experiences in line with people’s shifting news habits: the younger the informants are, the less they seem to rely solely on truthfulness and reliability as characteristics of sources, journalists and news organizations. For younger people, truth and trust appear as a result of verification activities such as triangulating different news sources (cf. Tandoc et al. Citation2018) or by searching for additional perspectives (crystallization), including news sources found to be unreliable (cf. Tsfati and Cappella Citation2005). Whether news is true and can be trusted has to be proven. In line with approaching truth and trust as a continuous process of verification instead of being characteristics of news, almost all informants appreciated being presented with more than one perspective.

Other basic conditions mentioned by informants were ease of use, providing conversation topics and accessibility. Consistent with the suggestion of Roth et al. (Citation2018) that a moderate level of enjoyment is necessary in order to enable appreciation, some informants admitted that they may avoid particular news because of the limited quality of the visuals or when articles were too long and tedious. News can be considered important, but, as emphasized by Nina (age 25, TV-editor), design and narrative are crucial to make journalism valuable:

I recently read a very nice long-read from The New York Times. It came with sound and pictures (…) That made a lot of impression. Normally I will read about such news on NOS.nl (PSM news app), and then I tend to get barely drawn into it, for it feels too distant. But by reading such a well-made long-read it becomes a whole different experience, a whole lot more realistic. And that I find important and I also treasure it.

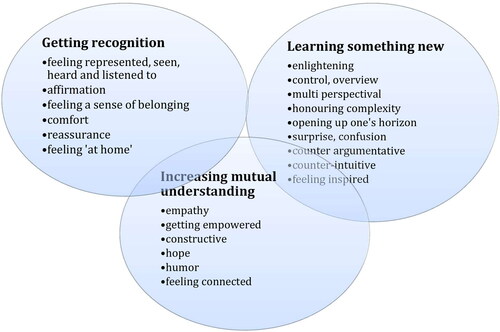

Meeting the qualities of trustworthiness, ease of use, accessibility, quality visuals and appropriate writing style, however, may still be insufficient to trigger a valuable news experience. Our informants emphasized that for that to happen, a news item will have to activate, evoke or elicit one or more of the following three key experiences: (1) Learning something new, (2) Getting recognition and (3) Increasing mutual understanding. All three experiences combine feelings of enjoyment with enlightenment illustrating how personal pleasure and civic interest are intertwined in Valuable Journalism.

Although our informants were aware of the hierarchy in societal importance associated with the different news genres, they claimed to appreciate similar experiences potentially evoked by any genre. For instance, both sports journalism, political journalism and lifestyle journalism could call up a feeling of empowerment (sub dimension of increasing mutual understanding), sometimes because these informants finally understood how provincial elections worked, at other times because they were encouraged to start jogging again or because they felt encouraged to clean up their cupboards.

provides a model which summarizes how people articulate their experience of journalism as enriching their lives. Each key experience refers to an underlying pattern consisting of a spectrum of emotions and sensations, resonating real pleasure and feeling truly informed.

Because the model of Valuable Journalism is meant to capture various user experiences empirically, it almost goes without saying that it will be impossible to meet these preferences in one “text,” one normative frame, one approach, one device, one genre, let alone one “single story” (cf. Adichie Citation2009). At the same time, it is doable—as I will show later on—to acknowledge in one news text “recognition” for one user, while enabling “learning something new” or “increasing mutual understanding” for another. The dynamics of these three key experiences will be described in more detail in the three sections below.

Getting Recognition

The satisfactory experience of being acknowledged, getting confirmation about the properness of one’s personal feelings and impressions, touches upon a fundamental need to be seen, heard and listened to and to count and qualify as a subject or even as a human being (Couldry Citation2015; O’Donnell, Lloyd, and Dreher Citation2009). This need is illustrated by Falko (age 63, voter populist party), who claimed "I read every morning that I am a jerk," and Mimoun (age 29), who said "If you want to win Muslims, you have to consider them as people and not as animals, with all due respect." When users felt that they were not addressed in a “proper” way, they realized how news is often functioning as second-order reality (cf. Silverstone Citation2007): others would know about them in as far as and how they appeared in news stories. The experience of recognition involves not only having a voice and being properly represented through the news media, but also, and more importantly, the fact that one’s voice is heard (Dreher Citation2009, Citation2012). The kind of pleasure “being heard” refers to, involves a sense of citizenship (agency, efficacy), in combination with the relief of being able to recognize other people’s experiences as similar to one’s own (I’m not a freak, I’m “normal”). An example of how journalism can trigger valued experiences of recognition was provided by a 53-year-old white resident of a multi-ethnic “problem neighbourhood”:

I saw a broadcast of Rondom Tien [serious talk show on national TV] a few weeks ago. It was about the last white residents in the neighbourhood. There were a few people who dared to tell how they felt as an immigrant in their own neighbourhood. And it made my heart break completely. There was a woman who said: “I step out of my home and after four or five blocks I arrive at my bakery. And only then someone will say ‘good morning’ to me for the first time.” That's how I feel it as well. And those people featured in Rondom Tien were not being prejudiced or so. They just said very calmly “I feel displaced and I would just love to hear Dutch around me again. Like ‘hey love, how are you doing?’. Well, I don't hear that here either.” (Quoted in: Costera Meijer Citation2013b)

The interviews illustrate Rantanen’s suggestion (Citation2009: 80) that “belonging has no meaning unless news offers readers a point of identification”. This sense of belonging, as testified by informants, is facilitated if residents are presented through the media with a “normal” basic identity, at least in the context of work and education (Flint Citation2002). According to Mehmet (age 34), his father, a long-time Turkish resident of Rotterdam, contributed substantively to the city’s urban renewal. Still, even though there have been many news items and documentaries about the post-war reconstruction and growth of Rotterdam, this narrative was never told from a Turkish perspective (cf. Oliver et al. Citation2012). Not recognizing the achievements of Turkish residents, Mehmet explained, might be an important reason why his father never felt that he truly belonged in the city where he lived and worked for more than fifty years.

Meeting people’s need for recognition is seldom acknowledged as a legitimate goal by journalists and journalism scholars. It may even be negatively framed as “confirmation bias” or “the postulation that individuals prefer messages that align pre-existing attitudes over those messages that challenge them” (Knobloch-Westerwick, Mothes, and Polavin Citation2020: 104). An explanation for the critical attitude of scholars towards “confirmation” may be tied to its political context, emphasizing political opinions and views, whereas our research uncovered people’s need for stories affirming their everyday experiences. This distinction may also explain—and this appears to conflict with research on “confirmation bias”—why getting recognition does not mean that news should confirm what people think. Rather, it should confirm that what they think makes sense. Although scholars and journalists would be the first to emphasize the importance of reliable and truthful representation, it is often overlooked how news can hurt if it ridicules or denies people’s everyday experiences (see Costera Meijer Citation2013b; Dreher Citation2009).

Learning Something New

Most people have a “tendency to engage in and enjoy thinking” (Lins de Holanda Coelho, Hanel, and Wolf Citation2020:1). As told by Leo (age 35): “If you have the idea that you have been able to learn something new, this momentarily gives you a sense of pure happiness.” Learning something new is used as label for those user experiences that open up the world for our informants, surprise them, provide them with counterarguments and offer them perspectives they were unaware of, broaden their horizon and enlighten them (cf. Gans Citation2011). Unlike “recognition,” providing the kind of pleasure learning something new elicits in people—or the satisfaction and appreciation one feels when receiving “food for thought” and being “moved to think” (Bartsch and Schneider Citation2014)—is seen as journalism’s core business.

One of the most intense and characteristic experiences of being encouraged to rethink one’s ideas and perspectives is the enlightening eye-opener experience: the joy of suddenly understanding a complex situation or topic. An example of this news experience is provided by Iňes (public servant, age 61). Recently, she watched a news show which made her aware of how building new nuclear plants may be a more sustainable solution to the planet’s climate crisis than other established technologies such as solar panels and windmills:

It turned my world upside down, realizing that my resistance against nuclear energy may be based on outdated information, while I overestimated the problem-solving ability of traditional ecological alternatives to our climate crisis.

Other informants, including so-called conspiracy thinkers, emphasized the sense of overview or control involved in this experience. As commented by Joop (age 67): “it is like when something is in the air that you have no control over, but that suddenly is a fact. You get a handle on it; it becomes tangible.”

Sceptics of “mainstream news” (their term) express a longing for alternative sources providing counter arguments to conventional news sources, such as why wearing masks doesn’t prevent Covid-19. Although the more sceptical informants regarded social media as an important source, these seldom functioned as substitute for regular news media. Some claimed that they did not want to end up in a so-called “bubble.” Xavia (age 61, academic), who reads a daily newspaper to keep up with mainstream news, is a case in point:

It's not like I'm just sitting in my own bubble or something. (…) People should think, I feel, whatever they want to think. As long as you can talk about it and discuss it and the facts become clear. (…) We do not all have to think the same way.

Although Tsfati and Cappella (Citation2005) suggest that an eagerness to learn something new is limited to a higher Need for Cognition, most informants at one time claimed to appreciate learning about new angles, getting surprised and being informed by strong counterarguments. This experience was particularly valued when new perspectives were provided by people one could identify with and when this cognitive learning experience touched an emotional nerve. McGoldrick and Lynch (Citation2016), when comparing the experience of war reporting and peace journalism, in fact demonstrated this point. Most people participating in their worldwide experiments appreciated the counter-intuitive stories about violence and war, in particular when they invited a form of identification with “the other side.” As argued by McGoldrick and Lynch (Citation2016: 635), these “evoked less anger and less disgust, while promoting hope and empathy, and enabling a cognitive engagement with the problems presented at multiple levels of causality, thus opening up receptiveness to a range of remedial measures.”

Increasing Mutual Understanding

The third key experience people distinguish as valuable journalism is labelled “increasing mutual understanding.” This experience involves becoming personally aware of one’s social relatedness and resonates with Michael Schudson’s (Citation1995) argument that journalists do not so much produce information but “public knowledge.” Like family life, work or the educational system, news media provide cultural, social and moral anchors. If there is no common source that people can draw on for telling and sharing stories, it is nearly impossible to build a cohesive community. By contributing to the ability of interpreting each other’s everyday habits, “public knowledge” can contribute to “what is recognised or accepted … given certain political structures and traditions” (Schudson Citation1995: 31). In line with James Carey (Citation2009: 63), mutual understanding presupposes learning “vital habits: the ability to follow an argument, grasp the point of view of another, expand the boundaries of understanding, debate the alternative purposes that might be pursued.”

Journalism is experienced as valuable when it deepens people’s comprehension of the world, their country, region, city or neighbourhood. On a hyper local level, one of our informants, Meg (age 71), wanted journalism to provide more information about Turkish residents: “how they cook, the kind of needlework they do, where exactly they come from.” But, as she added, “at the same time I am not assertive enough to knock on their door.”

Other informants illustrated how journalism may be valuable in the overlapping area of getting recognition, learning something new and increasing mutual understanding. Arnout, a mailman in one of the city’s problem neighbourhoods, actually received many reactions from residents after the broadcast in which he recited a poem written by him, “also from some of the neighbourhood’s Moroccan youngsters, as well as from other youngsters and other people who said to have seen me. Quite a few even. They liked it very much.” As librarian Emilie (age 48) commented on this item:

It is of course rather surprising; you see him walk by and you think, hey, there goes a mailman; you don’t think any further. But when you watched the item, you somewhat get to know the man behind the mailman, isn’t it? So, if you live here and you meet this man you have somewhat of an idea that you know him.

Living in a multi-ethnic urban problem area made residents appreciate stories that enable them to interpret each other’s behaviour, habits or responses more correctly (Costera Meijer Citation2013b). Becoming better able to figure out their fellow residents made them more predictable, which increased the neighbourhood’s and residents’ familiarity (feeling at home).

News may actually upset people when they realize that other news users trust some representation to be realistic which in their experience is at least ambiguous if not outright creating lots of misunderstanding. People value journalism which increases their understanding of the world (learning something new) on the condition that it also increases the world’s understanding of them (recognition) (cf. Coleman Citation2013). This may encourage one’s problem-solving ability and “civic imagination” and enables people to imagine themselves as actively participating in a larger democratic culture and “see oneself as a civic agent capable of making change”, as suggested by Jenkins, Shresthova, and Peters-Lazaro (Citation2020). Helen (age 65) voted for a populist party and experienced how its members were represented in talk shows as weirdos rather than as people with dissenting opinions. Show respect to everyone is her credo:

Interviewer: What effect do you think that could have when people watch a [respectful] item?

Helen: Mutual understanding. Cultivate understanding of the views of others. Surprise people without having to agree with these views.

Interviewer: To what should the journalist pay attention during such an interview?

Helen: Well, at least you treat the person you're interviewing seriously. And not in such condescending manner. Because everyone is entitled to their own opinion.

As Schudson (Citation1995: 8) put it: “Good journalism often is the means by which empathy is evoked.” This is particularly appreciated but not exclusively relevant in situations of conflict. Illustrative of peoples’ need for news facilitating mutual understanding was their response towards news about the various forms of political action around a major figure in the annual Dutch celebration of Saint Nicholas: Black Pete. It was remarkable how both black and white informants preferred those few news items which explained the range of emotions and viewpoints involved. Lowering the barrier for communication between opposing parties and thus discouraging unnecessary polarization was valued over exciting stories and (stock) images of activists in action, which merely added fuel to the fire. Similar results, if on a different subject, were provided by O’Neill et al. (Citation2013). Analysing the impact of news images in connection with the climate crisis, they found that people preferred imagery that leads to “understanding the situated meanings of carbon and energy in everyday life” (p. 420).

To facilitate understanding it is important, as suggested by O’Donnell (Citation2009: 510), to explore journalism-related listening practices, whereby audiences and users are invited to move beyond empathy and outside of their comfort zones by engaging with “unfamiliar and/or hostile perspectives.” Based on their experimental and comparative audience research in Australia, the Philippines, Mexico and South Africa, McGoldrick and Lynch (Citation2016: 643) concluded that many of the strongest effects came when dominant narratives justifying violence or perpetuating injustice were being challenged “by a ‘character’ whose personal story won attention and engagement by triggering empathy and hope.” This does not mean, as testified by informants of an urban problem neighbourhood, that residents only appreciate positive news. Illustrating the professional value of “proper distance” (Silverstone Citation2007, see section 3), they experienced both too good and too bad news about their neighbourhood as distorting one’s sense of reality: “It should just be realistic”, as one resident sighed. It is encouraging, as found by McGoldrick and Lynch (Citation2016), that people all over the world value stories which evoke their understanding of complex social situations (even though this does not always keep them from clicking on the more sensational ones (Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer Citation2018).

Styles of presentation, varying from constructive journalism (Hermans and Gyldensted Citation2019) to the use of humour, were also valued as adding to mutual understanding or easing tension. For instance, when hostilities in Amsterdam rose high between migrants and non-migrants after the murder of filmmaker Theo van Gogh, a local news item was made about an artist who had a T-shirt embroidered with the words “I love Holland” in Arabic. When the presenter asked passers-by to read the text aloud, he caused major hilarity, among the bystanders but also among the viewers. They suddenly realized that not all “Arabic-looking” people are actually capable of speaking or reading Arabic, and if they did, they had to say out loud—and most laughed while doing it—that they loved Holland, which in itself surprised viewers.

Defining Valuable Journalism

The argument presented here relies on analyzing personal user experiences by addressing the underlying patterns in language use, as well as the variations in the ways these experiences appeared to be key to actually use and appreciate journalism. The resulting three key experiences differ in orientation. The first key experience of getting recognition is oriented towards the self and creates a sense of belonging: feeling “at home.” The second key experience of learning something new is primarily geared towards society, invoking enlightenment and feeling inspired. The third key experience is linked to eliciting mutual understanding, or a “we”-perspective, which is mainly oriented towards others as part of “us” and invokes a common frame of reference: feeling connected.

Although all three experiences are equally important as articulations of valuable journalism, on a personal level, looking for balance appears to be the primary dynamic of actual appreciation and use. When people’s sense of belonging is secure, they appear to appreciate learning something new. However, when they experience themselves repeatedly as underrepresented or misunderstood, they tend to crave news that enhances their sense of being seen, heard and listened to. Recognition and confirmation may even function as conditional for news use as such. As Couldry (Citation2007) suggested, why would people still follow the news if journalists systematically ignore or poorly reflect their concerns, views, experiences and perspectives?

To answer the question of “what is Valuable Journalism,” I suggest to describe the concept as follows:

Valuable Journalism can be characterized as a meaningful, enlightening, surprising, empowering, comforting or reassuring experience which optimizes news enjoyment and civic empowerment and can be condensed into three key experiences: “Getting recognition,” “Learning something new” and “Increasing mutual understanding.” It satisfies fundamental human needs of autonomy, inspiration, sense of belonging, competence and social relatedness.

If Valuable Journalism refers to user experiences instead of particular genres, topics, beats or approaches, how can its conceptual framework be made relevant for journalism professionals and news organizations? This question will be addressed in the next two sections.

The Potential Profitability of Valuable Journalism

Christensen, Skok, and Allworth (Citation2012) suggested that an understanding of the key experiences of Valuable Journalism—and how these relate to time, place, need, habit, mood, device and platform—provides important clues for supplying a service people will actually spend their time and money on. Their claim is supported by a Dutch quality newspaper (De Volkskrant), which found that the issues most appreciated by a forum of subscribers were read over five times more than other articles (de Weerd Citation2020). In the same vein, a variety of newspapers—including local Norwegian newspapers, Dutch quality news media, the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter, the UK newspaper The Guardian and the American magazine The Atlantic—all got more subscribers if they paid more attention to what their audience experiences as valuable journalism.

The potential profitability of providing a valuable news experience was further firmed up by the results of an experiment of the Readership Institute (Citation2005). These suggested that a two-thirds majority of readers would spend more time and money on the version of the newspaper answering to (similarly worded) key experiences. These were labelled: “Gives me something to talk about”; “Looks out for my interests” (recognition); and “Turned on by surprise and humour” (learning something new and increasing mutual understanding). Although these experiences were sampled in the US more than fifteen years ago, among a specific (younger) age group and in relation to a particular product, namely newspapers, they were confirmed by research from Mersey, Malthouse, and Calder (Citation2012) and clearly resonate in the model of Valuable Journalism (see ).

Audience Attentiveness as Professional Practice

One of the main challenges of the contemporary news ecology is how to maintain professional standards of trustworthiness, accuracy and a firm commitment to finding truth in a world dominated by polarization, fragmentation and disinformation. Valuable Journalism calls up the question of how journalists can facilitate this experience in light of how people may articulate the same dimensions as valuable while simultaneously appreciating other journalism genres, stories or angles. Because the digitalization of journalism is accompanied by an increase of journalists—often freelancers—not working within the normative framework of a particular news organization (cf. Deuze and Witschge Citation2020), taking a neo-Aristotelian approach to journalism ethics may be part of the answer here. After all, these new news professionals have to carve out for themselves what kind of ethics they adhere to: what type of person would I need to be and what kinds of dispositions, habits and capacities (that is, “virtues”) would I need to have in order to act well as a journalist (and make good decisions) in particular situations (see Phillips et al. Citation2010: 52–53)? To professionally understand the (dynamics of) the key experiences of the empirical framework of Valuable Journalism, I introduce the normative concept of “Audience Attentiveness,” a professional practice inviting reflection on a series of six interrelated journalistic virtues (see Costera Meijer Citation2016).

Accuracy, Sincerity and Hospitality

In line with what the public experiences as the basic conditions of Valuable Journalism, truth and trust, Phillips et al. (Citation2010) suggest two professional, non-negotiable virtues of truth-telling, accuracy and sincerity:

Accuracy is the disposition to take the necessary care to ensure as far as possible that what one says is not false, sincerity is the disposition to make sure that what one says is what one actually believes. (p. 53)

The notion of hospitality (Silverstone Citation2007: 143) features as third virtue: “the baseline expectation is a willingness to ensure that the digital and analogue spectrum is available for minorities, the disadvantaged and for non-national transmission; (.) and that within news and current affairs the bodies and voices of those who might equally be otherwise marginalized will be seen and heard on their own terms.” For Phillips et al. (Citation2010: 54) hospitality is “a necessary part of any media ethics”.

As mentioned in the first section, a related “ethics of listening” (Dreher Citation2009; Wasserman Citation2013) may be identified as a fourth virtue here. Furthermore, I suggest two additional virtues inviting journalists to reflect on how they can be more attentive to audiences: being a good friend and keeping a proper distance (cf. Costera Meijer Citation2020a). After elaborating on these last four virtues below, I will discuss the kind of professional ambiguities and tensions they can cause for journalism and journalists.

Listening

Audience Attentiveness as a professional practice involves careful listening. This fourth virtue appears to be relevant for prompting each of the three key experiences. Dreher (Citation2009, Citation2010) and Wasserman (Citation2013) emphasize that listening is first of all meant to strengthen the voice of the people less heard in society (Getting Recognition). As argued by Wasserman (Citation2013: 79–80):

Journalists will have to learn to let go, to relinquish control. They will have to be prepared to let their own assumptions be challenged, to accept that the picture of reality that emerges during the process of listening might be more complex and incomprehensible than they thought, and that they themselves may be complicit in the very problems they seek to understand.

In this respect our informants demonstrated that these voices may not always be recognized as “victim” or “the underdog.” On the surface, for example, the only Dutch speaking resident of a multi-ethnic urban apartment building may be regarded as the most empowered person within this building because of her language advantage. But it was actually impossible for her to leave the baby phone with her neighbours because none of them was able to understand Dutch. When she complained about this, her concern was initially framed as an expression of “racism” in the regional newspaper. Only when the practical implications of her experience were clarified in a hyperlocal news story—as severely limiting this single mother’s mobility, including necessary tasks like grocery shopping but also going out in the evening once in a while—it became possible to comprehend her situation more fully (Increasing mutual understanding). Furthermore, it opened the eyes of people who were not living in such circumstances. Listening as facilitator of the valued experience of “Learning something new” may pertain to the same topic and frame, but the aim is to explain an issue in greater detail to “the other side.” The net result may be that the “other side” comes to realize that complaining about one’s non-Dutch neighbours should not be so easily dismissed as “racist.”

Dobson (Citation2012: 843) emphasized the virtue of listening as “helping to deal with deep disagreements, improving understanding and increasing empowerment” (Understanding). Silverstone (Citation2007: 137) has called this ethos “media hospitality,” which he considers the obligation to hear and to listen and to create a space for effective communication, “obligations which are imposed both on the media-weak as well as the media-powerful”. Ammar (age 47), a street vendor from a shelter for addicts, recognized this obligation to make oneself understandable. This even motivated him to participate in a local TV show:

I had the sense that people looked frowningly upon this building here. This whole idea of addicts and such. This I wanted to do away with. … For we are people, too; we are residents of Utrecht, fully integrated. If we use drugs, it does not yet mean that I am a monster or so.

After the item was aired, passers-by suddenly started addressing him “as a person”: “Hey, I saw you on TV last night.” When we talked to him later, he thought that his fellow residents’ idea of drug users appeared to have shifted somewhat, from being too frightening to even deal with towards being more approachable (understanding).

Being a Good Friend

Audience Attentiveness can also be compared to paying the kind of attention to readers, listeners and viewers which one would pay to a good friend (cf. Booth Citation1988). As with good friends, you may sometimes give them what they want—one more glass of wine, comfort and consolation—and at other times you may provide them with what they need: a comment urging them to sober up, a critical remark or a broadening of their horizon. Rather than looking for their attention, you give them your attention. As a journalist you want to find out what they need from you. Do they want to be surprised or learn something new about the world around them or the world at large? Or do you as a journalist receive signals that they need confirmation: a greater sense of being listened to and being taken seriously? Bugeja (Citation2009: 246) describes this kind of friendship as a “social contract.” He juxtaposes it with “a social contact,” which “can be added or deleted on demand with a mere click of the keys”. As Bugeja (Citation2009) puts it: “while it is true that friendship, in and of itself, may have little to do with the practice of journalism, the principles that define friendship—justice, responsibility, truth—relate directly to digital ethics” (246–247).

Keeping a Proper Distance

The final professional virtue identified that may help journalists to become more audience attentive is “proper distance.” Proper distance introduced by Silverstone (Citation2007)—both close and far—requires imagination, understanding and a duty of care (cf. p. 48). This includes winning and honouring people’s trust, which appears to be crucial to obtain “minority” stories as illustrated by a citizen journalist who got access to stories from residents of a trailer park. They told her candidly about life “at the park,” resulting in an item which illuminated this life from their point of view instead of from a distant outsider’s perspective (Costera Meijer Citation2013b). To get a handle on proper distance, Silverstone provides three examples of improper distance, all defying the call for journalism that users experience as valuable. An example of being “too close” perhaps pertains to embedded war journalism or the intrusion into the private lives of public figures, which may not teach people anything new. An example of being “too far” involves the practice of “othering” groups of people and thus preventing “common understanding.” As an example of being neither close nor far, Silverstone mentions celebrity journalism because it “destroys difference by exaggerating it (the ordinary made exceptional) as well as naturalizing it (the exceptional made ordinary).” This in turn can obstruct the need for mutual understanding, connection and identification.

Discussion: Valuable Journalism and Its Challenges for Journalism Scholarship

The six virtues of Audience Attentiveness—accuracy, sincerity, listening, hospitality, being a good friend and keeping a proper distance—invite professionals to facilitate experiences of valuable journalism. Because of its endless space digital journalism appears to create the material condition for providing valuable experiences for everyone by telling different news stories about important events or employing different angles to describe them. Just as “Getting recognition,” “Learning something new” and “Increasing mutual understanding” are distinctive experiences, the six virtues will not—at least not always—be compatible. This final section addresses four major challenges for journalism studies.

The first topic deserving attention from journalism scholars is how or even whether a specific angle, perspective or frame is as true as another. Our informants, in particular the ones not trusting “mainstream media,” sometimes demanded from journalism attention to perspectives and explanatory frames that speak against conventional (scientific) insights. Meeting preferences for “alternative” viewpoints may be incompatible with journalists’ primary virtues: accuracy and sincerity. In this respect it may help to distinguish informants’ opinions from their experiences. By approaching and explaining their underlying emotions, the gap between these virtues may be bridged. For example, while journalists are aware how members of a populist party may welcome journalism that put Moroccan adolescents away as petty criminals (in particular when they don’t know any Moroccans), our informants tend to value journalism if it acknowledges their underlying feelings of anger, loneliness or fear (cf. quote in “Getting Recognition” section).

The second challenge for journalism studies is how to tell stories that cater to different needs. Although the material condition is available in the digitized world, the endless space of digital journalism does not guarantee that particular valuable news stories can be found. This is where artificial intelligence (AI) may offer a way out, creating alternative news angles or access to “democratic algorithms” (Harambam, Helberger, and van Hoboken Citation2018: 1) to give people “more influence over the information news recommendation algorithms provide”. The idea of “algorithmic recommender personae” seems promising. As Harambam, Helberger, and van Hoboken (Citation2018) explain:

These are pre-configured and anthropomorphized types of recommendation algorithms from which people can choose from when browsing (news) sites. With one click, they get different sorts of (news) recommendations, enabling them to easily switch between different “versions of the world.” (p. 13)

These “versions of the world” are recommended by five personae: “the Explorer (news from unexplored territory), the Diplomat (news from the other side), the Wizard (surprising news), the Moral Vacationer (guilty pleasures), or the Expert (specialized news based on previous consumption)” (p. 14). Although the recommender personae potentially offer a solution to integrate multiple stories, multiple voices and viewpoints (listening and hospitality), it is questionable whether non-human agents like recommender systems or search engines can be held accountable to the truth-telling virtues, in particular sincerity. In this regard, Golebiewski and boyd (Citation2019) point to the existence of “data voids”, low-quality data situations in which “alternative facts” can take root and flourish.

The third challenge that may need more attention from journalism scholars is how mastering the art of “audience attentiveness” and integrating its virtues into everyday journalism practices may advance journalism’s contribution to the vitality of democracies. Referring to Schudson's (Citation2008) list of six or seven things news can do for democracy, some avenues for future research can be outlined. The vital information function of journalism may benefit from information studies’ distinction between being informed and actually feeling informed (facilitated by Listening, Keeping a proper distance and Being a good friend). Insights from Entertainment Studies may be explored to intensify the value of the investigation function. This can be done for instance by distinguishing hedonist experiences-such as fun, diversion or distraction—from eudaimonic experiences—such as feeling moved into an unknown world, flow, enchantment or enlightenment. Design thinking may assist journalism scholarship to improve the efficacy of analysis as democratic function: How can a particular design improve an inspiring and thought-provoking analysis which honours complexity? The likelihood of experiencing social empathy can be increased by expanding the scope of news literacy with James Carey's vital habits (cf. “People’s Articulation of Their Experience of Valuable Journalism” section). The Public forum function may profit from the potential of artificial intelligence to facilitate access, communication, findability, ease of use and thus a constructive participation in media culture (cf. second challenge). Journalism Studies can learn from Narrative Studies to increase Mobilization as democratic function, such as by exploring how to narrate the news in such a way that prompts audiences to think or to open up their horizon. And, finally, if we accept that journalism has to contribute to what is perhaps the most important societal function, Explaining how democracy works, scholars have to investigate more thoroughly how and when “explainers” as particular format are valued.

The dominant qualitative approach to Valuable Journalism is cause for a fourth challenge. The three key experiences invite quantitative experiments and surveys which may determine the frequency and the relative importance of their various sub-dimensions and their demographic or geographic distribution.

A final challenge for journalism scholars is related to the empirical character of Valuable Journalism. What has remained underresearched is the potential normative dimension of valuable journalism. Which ethical dimensions would news users appreciate in order to reflect on their personal news experiences? This gap should encourage journalism scholars to invent new concepts which foster normative reflection on people’s own news involvement: was it worth my time and clicks (see Costera Meijer Citation2016; Citation2020a)?

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful for the encouraging, timely and constructive feedback received from two anonymous reviewers. This article has also benefited immensely from Oscar Westlund's unwavering support, valuable feedback from Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, helpful comments from Ton Brouwers, and Bernadette van Dijck and fruitful conversations with Constanza Gajardo Leon and Tim Groot Kormelink.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. 2009. "The Danger of a Single Story." TEDGlobal July 2009. https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story/transcript.

- Anderson, P., M. Williams, and G. Ogola, eds. 2013. The Future of Quality News Journalism: A Cross-Continental Analysis. New York: Routledge.

- Bartsch, A., and T. Hartmann. 2017. “The Role of Cognitive and Affective Challenge in Entertainment Experience.” Communication Research 44 (1): 29–53.

- Bartsch, A., and M. B. Oliver. 2011. “Making Sense of Entertainment: On the Interplay of Emotion and Cognition in Entertainment Experience.” Journal of Media Psychology 23 (1): 12–17.

- Bartsch, A., and F. Schneider. 2014. “Entertainment and Politics Revisited: How Non-Escapist Forms of Entertainment Can Stimulate Political Interest and Information Seeking.” Journal of Communication 64 (3): 369–396.

- Booth, W. C. 1988. The Company We Keep: An Ethics of Fiction. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

- Bowen, G. A. 2006. “Grounded Theory and Sensitizing Concepts.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (3): 12–23.

- Bugeja, M. 2009. “Digital Ethics in Autonomous Systems.” In The Handbook of Mass Media Ethics, edited by. Lee Wilkins and Clifford G. Christians, 242–257. London: Routledge.

- Carey, J. W. 2009. Communication as Culture. Essays on Media and Society. Rev. ed., Orig. 1989. London: Routledge.

- Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications.

- Christensen, Clayton M., David Skok, and James Allworth. 2012. Breaking News. Mastering the Art of Disruptive Innovation in Journalism. Vol. 66, No. 3. Boston: The Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University.

- Coleman, S. 2013. “Debate on Television: The Spectacle of Deliberation.” Television & New Media 14 (1): 20–30.

- Conboy, M. 2002. The Press and Popular Culture. London: Sage.

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 1990. “Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria.” Qualitative Sociology 13 (1): 3–21.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2007. “The Paradox of Popularity: How Young People Experience the News.” Journalism Studies 8 (1): 96–116.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2010. “Democratizing Journalism? Realizing the Citizen's Agenda for Local News Media.” Journalism Studies 11 (3): 327–342.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2013a. “Valuable Journalism: The Search for Quality from the Vantage Point of the User.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 14 (6): 754–770.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2013b. “When News Hurts. The Promise of Participatory Storytelling for Urban Problem Neighbourhoods.” Journalism Studies 14 (1): 13–28.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2016. “Practicing Audience-Centred Journalism Research.” In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by T. Witschge, C. Anderson, D. Domingo, and A. Hermida, 546–561. London: Sage.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2020a. “Journalism, Audiences and News Experience.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanitzsch, 2nd ed., 730–761. London: Routledge.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2020b. “What Does the Audience Experience as Valuable Local Journalism? Approaching Local News Quality from a User’s Perspective.” In The Routledge Companion to Local Media and Journalism, edited by A. Gulyas and D. Baines, 357–367. London: Routledge.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2020c. “Understanding the Audience Turn in Journalism: From Quality Discourse to Innovation Discourse as Anchoring Practices 1995–2020.” Journalism Studies 21 (16): 2326–2342.

- Costera Meijer, I., and H. P. Bijleveld. 2016. “Valuable Journalism: Measuring News Quality from a User’s Perspective.” Journalism Studies 17 (7): 827–839.

- Costera Meijer, I., and T. Groot Kormelink. 2021. Changing News Use. Unchanged News Experiences? London, New York: Routledge.

- Couldry, N. 2007. “Media and Democracy: Some Missing Links.” In Inclusion through Media, ed. Tony Dowmunt, Mark Dunford, and Nicole Van Hemert, 254–264. London: Goldsmiths, University of London.

- Couldry, N. 2015. Listening Beyond the Echoes: Media, Ethics, and Agency in an Uncertain World. London: Routledge.

- de Weerd, F., ed. 2020. ‘Open redactie’ De Volkskrant (‘Open Editorial office’) personal communication.

- De Maeyer, J. 2020. “A Nose for News”: From (News) Values to Valuation. Sociologica 14 (2): 109–132.

- Deuze, M., and T. Witschge. 2020. Beyond Journalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Dobson, A. 2012. “Listening: The New Democratic Deficit.” Political Studies 60 (4): 843–859.

- Dreher, T. 2009. “Listening across Difference: Media and Multiculturalism beyond the Politics of Voice.” Continuum 23 (4): 445–458.

- Dreher, T. 2010. “Speaking up or Being Heard? Community Media Interventions and the Politics of Listening.” Media, Culture & Society 32 (1): 85–103.

- Dreher, T. 2012. “A Partial Promise of Voice: Digital Storytelling and the Limits of Listening.” Media International Australia 142 (1): 157–166.

- Flint, J. 2002. “Return of the Governors: Citizenship and the New Governance of Neighbourhood Disorder in the UK.” Citizenship Studies 6 (3): 245–264.

- Gans, H. J. 2011. “Multiperspectival News Revisited: Journalism and Representative Democracy.” Journalism 12 (1): 3–13.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., and Hinsley, A. 2013. The Press Versus the Public: What is “Good Journalism?” Journalism Studies 14 (6): 926–942.

- Glasser, T. L., ed. 1999. The Idea of Public Journalism. New York: The Guildford Press

- Golebiewski, M., and D. Boyd. 2019. Data Voids: Where Missing Data Can Easily Be Exploited. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/research/.

- Groot Kormelink, T., and I. Costera Meijer. 2017. “It’s Catchy, but It Gets You F*Cking Nowhere”: What Viewers of Current Affairs Experience as Captivating Political Information.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 22 (2): 143–162.

- Groot Kormelink, T., and I. Costera Meijer. 2018. “What Clicks Actually Mean: Exploring Digital News User Practices.” Journalism 19 (5): 668–683.

- Harambam, J., N. Helberger, and J. van Hoboken. 2018. “Democratizing Algorithmic News Recommenders: How to Materialize Voice in a Technologically Saturated Media Ecosystem.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 376 (2133): 20180088. doi:https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2018.0088.

- Hermans, L., and C. Gyldensted. 2019. “Elements of Constructive Journalism: Characteristics, Practical Application and Audience Valuation.” Journalism 20 (4): 535–551.

- ISO DIS 9241-210. 2010. “Ergonomics of Human System Interaction - Part 210: Human-Centred Design for Interactive Systems.” Tech. Rep., International Organization for Standardization, Switzerland.

- Jenkins, H., S. Shresthova, and G. Peters-Lazaro, eds. 2020. Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination. Case Studies of Creative Social Change. New York: New York University Press.

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S., C. Mothes, and N. Polavin. 2020. “Confirmation Bias, Ingroup Bias, and Negativity Bias in Selective Exposure to Political Information.” Communication Research 47 (1): 104–124.

- Kunelius, Risto. 2006. “Good Journalism.” Journalism Studies 7 (5): 671–690. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700600890323.

- Lindlof, T. R. 1995. Qualitative Communication Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lins de Holanda Coelho, G., H. P. P. Hanel, and L. Wolf. 2020. “The Very Efficient Assessment of Need for Cognition: Developing a Six-Item Version.” Assessment 27 (8): 1870–1885.

- Lynch, J., and A. McGoldrick. 2014. Peace Journalism. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Hawthorn Press.

- McGoldrick, Annabel, and Jake Lynch. 2016. “Audience Responses to Peace Journalism.” Journalism Studies 17 (5): 628–646.

- Meier, K. 2019. “Quality in Journalism.” In Vos, T.P., Hanusch, F. (eds), The international encyclopedia of journalism studies: 1–8. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Mersey, R. D., E. C. Malthouse, and B. J. Calder. 2012. “Focusing on the Reader: Engagement Trumps Satisfaction.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 89 (4): 695–709.

- Mirnig, A. G., A. Meschtscherjakov, D. Wurhofer, T. Meneweger, and M. Tscheligi. 2015. “A Formal Analysis of the ISO 9241-210 Definition of User Experience.” Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 437–450.

- O’Donnell, P. 2009. “Journalism, Change and Listening Practices.” Continuum 23 (4): 503–517.

- O’Donnell, P., J. Lloyd, and T. Dreher. 2009. “Listening, Pathbuilding and Continuations: A Research Agenda for the Analysis of Listening.” Continuum 23 (4): 423–439.

- Oliver, M. B., and A. A. Raney. 2011. “Entertainment as Pleasurable and Meaningful: Identifying Hedonic and Eudaimonic Motivations for Entertainment Consumption.” Journal of Communication 61 (5): 984–1004.

- Oliver, M., and A. Bartsch. 2010. “Appreciation as Audience Response: Exploring Entertainment Gratifications beyond Hedonism.” Human Communication Research 36 (1): 53–81.

- Oliver, Mary Beth, James Price Dillard, Keunmin Bae, and Daniel J. Tamul. 2012. “The Effect of Narrative News Formats on Empathy for Stigmatized Groups.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 89 (2): 205–224.

- Oliver, M. B., Raney, A. A., Slater, M. D., Appel, M., Hartmann, T., Bartsch, A., Schneider, F. M., et al. 2018. “Self-transcendent Media Experiences: Taking Meaningful Media to a Higher Level.” Journal of Communication 68 (2):380–389. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqx020.

- O’Neill, S. J., Boykoff, M., Niemeyer, S., and Day, S. A. 2013. “On the Use of Imagery for Climate Change Engagement.” Global Environmental Change 23 (2): 413–421.

- Phillips, Angela, Nick Couldry, and Des Freeman. 2010. “An Ethical Deficit? Accountability, Norms, and the Material Conditions for Contemporary Journalism.” In New Media, Old News: Journalism & Democracy in the Digital Age, edited by Fenton, Nathalie, 51–67. London: Sage.

- Picard, R. G., ed. 2000. Measuring Media Content, Quality, and Diversity Approaches and Issues in Content Research. Turku: Media Economics, Content and Diversity Project and Media Group, Business Research and Development Centre, Turku School of Economics and Business Administration.

- Rantanen, T. 2009. When News Was New. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

- Readership Institute. 2005. Reinventing the Newspaper for Young Adults. A Joint Project of the Readership Institute and Star Tribune. Evanston, IL: Media Management Center at Northwestern University.

- Richardson, L. 2000. “Writing: A Method of Inquiry.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by Norman K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 2nd ed., 923–948. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Roth, F. S., C. Weinmann, F. M. Schneider, F. R. Hopp, M. J. Bindl, and P. Vorderer. 2018. “Curving Entertainment: The Curvilinear Relationship between Hedonic and Eudaimonic Entertainment Experiences While Watching a Political Talk Show and Its Implications for Information Processing.” Psychology of Popular Media Culture 7 (4): 499–517.

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2000. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” American Psychologist 55 (1): 68–78.

- Schrøder, K. C. 2015. “News Media Old and New: Fluctuating Audiences, News Repertoires and Locations of Consumption. Journalism Studies.” Journalism Studies 16 (1): 60–78.

- Schrøder, K. C., and B. Steeg Larsen. 2010. “The Shifting Cross-Media News Landscape: Challenges for News Producers.” Journalism Studies 11 (4): 524–534.

- Schudson, M. 1995. The Power of News. Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press.

- Schudson, M. 2008. Why Democracies Need an Unlovable Press. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Silverstone, R. 2007. Media and Morality: On the Rise of the Mediapolis. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Tandoc, E. C., Jr., R. Ling, O. Westlund, A. Duffy, D. Goh, and L. Zheng Wei. 2018. “Audiences’ Acts of Authentication in the Age of Fake News: A Conceptual Framework.” New Media & Society 20 (8): 2745–2763.

- Thomas, D. R. 2006. “A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data.” American Journal of Evaluation 27 (2): 237–246.

- Tsfati, Y., and J. N. Cappella. 2005. “Why Do People Watch News They Do Not Trust? The Need for Cognition as a Moderator in the Association between News Media Skepticism and Exposure.” Media Psychology 7 (3): 251–271.

- Usher, N. 2018. “Re-Thinking Trust in the News: A Material Approach through ‘Objects of Journalism’.” Journalism Studies 19 (4): 564–578.

- Van Der Wurff, R., and Schoenbach, K. 2014. Civic and Citizen Demands of News Media and Journalists: What does the Audience Expect from Good Journalism? Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91 (3): 433–451.

- Vorderer, P., and U. Ritterfeld. 2009. “Digital Games.” In The Sage Handbook of Media Processes and Effects, edited by Vorderer, P., Ritterfeld, U., Nabi, R. L., and Oliver, M. B., 455–467. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Vorderer, Peter, Christoph Klimmt, and Ute Ritterfeld. 2004. “Enjoyment: At the Heart of Media, Entertainment.” Communication Theory 14 (4): 388–408.

- Wasserman, H. 2013. “Journalism in a New Democracy: The Ethics of Listening.” Communicatio 39 (1): 67–84.

- Webster, J. G., and T. B. Ksiazek. 2012. “The Dynamics of Audience Fragmentation: Public Attention in an Age of Digital Media.” Journal of Communication 62 (1): 39–56.

- Wendelin, M., Engelmann, I., and Neubarth, J. 2017. “User Rankings and Journalistic News Selection: Comparing News Values and Topics.” Journalism Studies 18 (2): 135–153.

- Wertz, F. J., K. Charmaz, M. McMullen, R. Josselson, R. Anderson, and E. McSpadden. 2011. Five Ways of Doing Qualitative Analysis Phenomenological Psychology, Grounded Theory, Discourse Analysis, Narrative Research, and Intuitive Inquiry. New York: Guilford Press.

- Wetherell, M., and J. Potter. 1988. “Discourse Analysis and the Identification of Interpretative Repertoires.” In Analysing Everyday Explanation: A Casebook of Methods, edited by C. Antaki, 168–183.

- Zelizer, B., and S. Allan. 2010. Keywords in News and Journalism Studies. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.