Abstract

This study investigates the degree of news avoidance during the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic in the Netherlands. Based on two panel surveys conducted in the period April–June 2020, this study shows that the increased presence of this behavior, can be explained by negative emotions and feelings the news causes by citizens. Moreover, news avoidance indeed has a positive effect on perceived well-being. These findings point to an acting balance for individual news consumers. In a pandemic such as Covid-19 news consumers need to be informed, but avoiding news is sometimes necessary to stay mentally healthy.

Introduction

The public has felt an extreme need to be informed during this Covid-19 crisis, leading to substantial rises in (digital) news consumption in the beginning of 2020 (Newman et al. Citation2020). Since the outbreak of Covid-19, public authorities and governments as well as public health experts have been providing the public with information, with news media playing a central role to reach the audience. In general, people depend on news media to be informed on what happens around them, especially in times of crisis (Ball-Rokeach Citation1985; Boukes, Damstra, and Vliegenthart Citation2021; Lee Citation2013). With highly changeable policies concerning measurements to control the outbreak of the Covid-19 virus and much uncertainty and insecurity on how the virus will develop, news media play a crucial role in helping people try to cope with the situation. Based on the uncertainty reduction theory, people feel the need to seek for information when they are uncertain about a specific situation or context (Boyle et al. Citation2004). However, at a certain stage, the news might also simply be “too much”, and can have negative consequences, such as harming people’s mental well-being, and therefore leading people to tune out from it. The current study explores this news avoidance: Who tends to avoid the news and how is this related to their well-being?

With a plethora of news, talk shows, current affairs programs and live blogs to follow the most recent developments while the news unfolds, the public with access to these channels does not have to worry about lacking the opportunity of being informed. In fact, the abundance of information during this pandemic has been described as an infodemic by the World Health Organization, describing the overload of information out there, including rumors and misinformation (Zarocostas Citation2020), as well as strongly varying opinions from politicians and experts. While news media are crucial in informing people during large crises, too much information can create negative emotional public reactions (Boyle et al. Citation2004). Earlier studies already show paradoxes of the high-choice media landscape (Chyi and Yang Citation2009; Prior Citation2007). The abundant presence of information and ample choices of news media, particularly in current digital media landscape, can lead to (temporarily) avoidance of (certain) news media or news coverage (Bos, Kruikemeier, and de Vreese Citation2016; Skovsgaard and Andersen Citation2020; Trilling and Schoenbach Citation2013).

In this study, we look at how news consumption has evolved during the first four months of the Covid-crisis. Can we speak of an increase in news avoiders and more importantly, what are the reasons for them to avoid the news? Previous research on news avoidance has shown that people who avoid the news say that news consumption is an “emotionally draining chore” (Palmer and Toff Citation2020, 1642): News demands too much mental effort and emotional energy.

Taking this a step further, we want to understand how news consumption—or more specifically, the avoidance of news—affects how people feel. Previous studies showed that consumption of news can have negative effects on, for example, people’s well-being and emotional state (Boukes and Vliegenthart Citation2017; Boyle et al. Citation2004; Newman et al. Citation2017). However, until now there is no study analyzing the relationship between news avoidance and people’s mental well-being, while a relationship between the two is often assumed (Woodstock Citation2014). This study is, therefore, twofold.

First, we aim to get a deeper understanding of the presence of news avoidance behavior while the pandemic evolved and potential antecedents of this behavior. Second, we examine the consequences of news avoidance, by investigating to what extent a causal relationship exists between news avoidance and well-being. Through two different panel surveys, this study focuses on the Netherlands as trust in news has been considerably high in 2020 (61%; Newman et al. Citation2020). This helps understanding how news avoidance evolves in a relatively high trust environment. The case of the Covid-19 pandemic and infodemic provides a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of news avoidance in an highly abundant digital news environment and the relationship between news and well-being of the public.

News Abundance and News Avoidance

The process of digitalization has dramatically changed the way people have consumed news in the past decennia. News can be consumed at anytime, anywhere and can even be tailored to the wishes of the consumer (Costera Meijer and Groot Kormelink Citation2015). News use has become more accessible and often intertwined with other daily activities. At the same time, in this high-choice media society, research has also shown that more people consciously decide to avoid the news, either completely (Newman et al. Citation2017) or to sometimes take a break from news (Palmer and Toff Citation2020).

If we zoom in on news behavior in times of crisis, previous research on news consumption shows that people are willing and in need for more information, such as was the case after the 9/11 terrorist attacks (Boyle et al. Citation2004). In line with uncertainty reduction theory (Berger and Calabrese Citation1975), the argument is that during crisis people try to reduce their uncertainty and negative feeling by seeking more information with the hope to learn more. People can seek for information directly at government, health or environment institutions, depending on the type of crisis, but more likely is that they first consult (news) media to learn more about the crisis and to make sense of what is happening around them. Actually, media dependency theory assumes that in an increasingly complex society, people depend and rely more on mass media than interpersonal relationships when seeking information (Lowrey Citation2004). During a crisis, such as the 9/11 attack, people do not tend to avoid the news, but seek for more information in the news media to try to get a better understanding of the situation (Boyle et al. Citation2004). In times of a societal lock-down where people lack many of such interactions with their peers, this could even more plausible. However, in current media landscape with an overload of digital channels to follow the news, people might also look for alternative channels to become informed and tune out from mass media.

The phenomenon of news avoidance has recently gained attention with a growing number of studies trying to understand it conceptually and empirically (Edgerly Citation2017; Skovsgaard and Andersen Citation2020; Toff and Kalogeropoulos Citation2020; Toff and Palmer Citation2019). Nevertheless, the concept still remains quite diffuse and fragmented as it has been operationalized in numerous ways using different methodological approaches, such as measuring news avoidance by the limited amount of news exposure compared to the standard (Edgerly Citation2015), or using a cut-off point, such as using news less than once a week (Shehata Citation2016; Schrøder and Blach-Ørsten Citation2016; Toff and Kalogeropoulos Citation2020). In this study, we operationalize news avoidance by explicitly asking respondents about how they perceive their own news avoidance behavior, similarly to what Newman et al. (Citation2020) ask in their survey, and so in the first wave we ask “Since Covid-19 I avoid the news more often” on a seven-point likert-scale (see methodology for all items). In the following waves we ask: “Since the past two weeks I avoid the news more often.”

The Reuters Institute has seen a general increase in active news avoidance, from 29% in 2017 to 32% in 2019 (Newman et al. Citation2017, Citation2019). Interestingly, country differences might be explained by specific incidents or crisis. The UK showed in increase of 11% in 2019 compared to 2017, due to Brexit. In 2017 Greece and Turkey showed the highest percentage of news avoidance compared to other countries, which might be explained by the political and economic turmoil in those countries at the time (Newman et al. Citation2017).

Recent research on news consumption and avoidance in six European countries during the Covid-19 crisis shows an increase in news consumption, particularly the television news and online sources are consulted to follow the news on the pandemic (Newman et al. Citation2020). While printed newspapers have seen a decrease, the use of social media has substantially increased. Following this upsurge, research focusing on the UK shows a significant increase in people avoiding the news actively, from 15% in mid-April to 22% in mid-May and if the people who say they sometimes avoid the news are included, there is a rise from 49% to 59% (Kalogeropoulos et al. Citation2020a).

The question then remains whether we can assume that the uncertainty reduction theory and media dependency theory can also be applied during a crisis in the current high-choice online media society? Or that we see an increase in news avoidance as a result of this information-overloaded media landscape. On the one hand, people need information to reduce their uncertainty and therefore might consume more news but, on the other hand, the infodemic might lead to people avoid news coverage all together, therefore we ask:

RQ1: How does the public's news consumption and avoidance develop during the pandemic?

News Avoiders and Their Motivations

After understanding how news use and avoidance develops during the pandemic, the question is who these people who choose to avoid the news are and why do they do so. Does the changing media landscape also lead to gaps between people who use and avoid news?

Studies on news use show different factors for people using and avoiding news, such as the role of age and socialization (Edgerly et al. Citation2018), gender norms (Toff and Palmer Citation2019) and political ideology (Toff and Kalogeropoulos Citation2020). Younger people and women tend to avoid the news more often, likewise left-wing are a little more likely to avoid the news (Toff and Kalogeropoulos Citation2020). Recent research on news use in the UK during Covid-19 pandemic showed similar results with women (26%) being more likely to avoid the news than men (18%) (Kalogeropoulos et al. Citation2020a).

Reasons for avoiding the news are numerous, such as the possible negative effect it can have on people’s moods (Kalogeropoulos Citation2017), the negativity of the news might be depressing (Schrøder and Blach-Ørsten Citation2016), lack of time to consume news (Toff and Palmer Citation2019), or the abundance of news that is out there leads to people not wanting to choose at all what to consume. A feeling of information overload is felt to create stress and anxiety (Eppler and Mengis Citation2004). Song, Jung, and Kim (Citation2017) show that receiving too much information can lead to fatigue and difficulties in information processing. A strategy for coping with the cognitive concern and information overload is to avoid the news. Recent research from the Reuters Institute on news consumption and avoidance among UK citizens during the Covid-19 crisis shows that people who say they always or often avoid news believe it might have an effect on their mood (66%), while 33% feel there is an overabundance of news and 28% feel that they cannot do anything with information (Kalogeropoulos et al. Citation2020b). In this study, we also want to understand who these people are who choose to avoid the news and why do they do so. Therefore, we formulate the following research questions:

RQ2: Who avoids the news during the pandemic Covid-19?

RQ3: Why do people avoid news during the pandemic Covid-19?

News Consumption and Well-Being

Following our understanding of news consumption and avoidance during the pandemic we subsequently want to understand how this might be related to people’s well-being. (News) media consumption may have uplifting effects for people’s mental well-being. This has already been found for television viewing in general (Zillmann Citation1991), but more specifically also entertainment experiences, such as binge-watching (as long as people don’t feel guilty about this, Granow, Reinecke, and Ziegele Citation2018). Similar to outdoor activities (Lades et al. Citation2020), positive effects of media consumption on well-being are explained by the energetic arousal and recovery experiences that is provides (i.e., “renewal of physical and psychological resources after phases of stress and strain”, Reinecke, Klatt, and Krämer Citation2011: 195). One might seriously doubt whether this potential also exists for the consumption of news coverage, in particular in the times of this all-overwhelming Corona pandemic. Arguably, news consumption does not provide the necessary relaxation and break-away from existing psychological concerns (Boczkowski and Mitchelstein Citation2010), but may actually strengthen the concerns that people have and be raising the negative emotions during this pandemic (Lades et al. Citation2020). Additionally, more studies show that emotions play a role in the (dis)engagement with news texts, (dis)trust in news media and selective exposure or news avoidance of the audience (Wahl-Jorgensen and Pantti 2021; Song Citation2017) and we therefore study the audiences' affective relations with news media.

Research on the consequences that news consumption had in the days following the terrorist attacks of 9/11 found that it was related to increasing stress reactions (Schuster et al. Citation2001). Accordingly, those that are heavy consumers of such a traumatic event run the risk of becoming a “secondary victim” (Shoshani and Slone Citation2008)—not because they are physically harmed, but due to the negative psychological consequences that they experience. If this was already found for news about an event for which closure more or less had taken place—the terrorist attack happened and most threat was gone—we may assume that such a negative impact of news consumption on well-being will also exist for a threat (both health and economic) that persists (Lades et al. Citation2020).

Conclusions from previous qualitative research pointed out that citizens are aware of this negative impact on their mental well-being that news exposure may have, and therefore is a reason for them to consciously avoid the news (Woodstock Citation2014). The main reason, found in this research, to avoid in the news is the feeling of powerlessness that it evokes among viewers. Although citizens could take personal measures to avoid being infected themselves during the first months of the pandemic, the news will have made them aware of the increasing infection rates in the country, overcrowded intensive care units, and little hope that this will improve in the time to come. As this was mostly framed in an abstract manner (i.e., numbers of victims, expected economic damage), this sense of powerlessness could also be a reason for citizens to tune out from the news in 2020. Avoidance might then be a conscious strategy to circumvent negative consequences.

The question that remains is whether news avoidance during the Covid-19 pandemic had indeed a positive influence on citizens’ well-being. Whereas we know that news consumption may have a repressive influence on positive developments of mental well-being (Boukes and Vliegenthart Citation2017)—with less news consumption leading to higher levels of well-being—it is still unknown whether the conscious avoidance of news may have a positive impact on people’s psychological state. If that would be the case—i.e., news avoidance positively affecting well-being—the question is whether these people would return to the news when their well-being is back on a higher level, and thus whether this results in a vicious circle of more/less news avoidance and better/worse mental well-being. Survey research seems to indicate that negative feelings do not relate to levels of news consumption in the American context (Edgerly Citation2021), but limited evidence is available for this relationship. Accordingly, we investigate the causality and direction of the relationship between these two variables using repeated measurements from a panel survey:

RQ4: What is the relationship between news avoidance and well-being during the pandemic?

Method

For this study, we rely on two different panel surveys conducted in the Netherlands. We focus on the Netherlands as a specific country study. The Reuters Institute analyzed news consumption patterns during the first pandemic wave in six different countries and consequently focused on the UK to understand news avoidance behavior (Newman et al. Citation2020). In this study, we focus on the Netherlands: a country that chose a more lenient policy instead of a strict lockdown in the first few months of the pandemic. Moreover, trust in news in the Netherlands is relatively high (61%) in 2020, while in the UK this is 39%. Studies have shown that news media distrust can lead to more consumption of non-mainstream news (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020). Skovsgaard and Andersen (Citation2020) even state that a cause for news avoidance is distrust in news. The first panel survey allows us to gain deeper insights in news avoiders and their reasons for not consuming the news (RQ 1, 2 and 3). The second panel survey, additionally, provides the necessary insights to disentangle the causal relationship between news avoidance and mental well-being (RQ 4). We now continue with Study 1, and afterwards discuss the methods and results of Study 2.

Study 1

The data for the first study were collected with a three-wave online panel survey during the first four months of the Covid-19 crisis in The Netherlands. The dates for the survey were carefully determined, based on new developments concerning the Dutch measures to stop the spread of the virus. The survey was conducted by I&O Research, an ISO-certified research company. The first wave was fielded on April 6, 2020, three weeks after the lockdown was introduced. A stratified sample from the I&O’s panel was drawn by gender, age, region and education level. Gross 3,517 panel members were invited. The questionnaire was fully completed by 1635 panel members, a response rate of 46.5%. The survey was closed on April 14, 2020. The second wave was fielded on May six and closed on May 25, during this period the primary schools were reopened. The second questionnaire was completed by 1,420 panel members, a retention of 87%. The third and final wave was sent on June 16, 2020 and closed June 26 and was completed by 1,173 panel members (83%); this wave took place two weeks after public buildings and restaurants re-opened and most of the lockdown was stopped and measurements were eased (on June 1).

Measures

In all three waves of the first panel survey, the same variables and questions were measured to investigate the development of news consumption behavior during the first months of the pandemic. Here, we focus on self-evaluation reports on news consumption during the corona-crisis to research how they experience news and their news consumption during the crisis.

The first question we consider is whether people report a change in news consumption. More specifically, respondents were asked to report whether, since the Covid-19 crisis started, they (1) avoided the news more often; (2) avoided the news related to Covid-19 more often; (3) take a break from news on Covid-19 once in a while and (4) want to avoid the news more often, but consider this difficult. We did not provide a more detailed explanation on how we define news avoidance or a specification of the term “news”, but straightforwardly asked them these questions. All items are measured on a 7-point Likert scale.

We used these four questions to construct a scale for news avoidance for each wave separately (Mwave1=3.13, SD wave1=1.44, α wave1=.85; Mwave2=3.20, SD wave2=1.50, α wave2=.87; Mwave3=3.15, SD wave3=1.47, α wave3=.89). While variation in individual items over time exists, mean scores are relatively stable.

The final question of substantial interest relates to the potential negative consequences of news consumption, that might simultaneously function as motivations for news avoidance. More specifically people were asked whether they agreed with the following statements:

News related to Covid-19 has a negative effect on my mental well-being;

News related to Covid-19 makes me feel emotionally charged;

News related to Covid-19 gives me the feeling there is little I can do (low efficacy);

News related to Covid-19 gives me the feeling there is something I can do (high efficacy);

I’d rather ignore the news related to Covid-19;

The news related to Covid-19 gives me the feeling getting overloaded with information.

We used those six items to assess the news-related well-being of respondents. The first, second, third, fifth and sixth item were reversely coded and mean scores per wave calculated (Mwave1=4.35, SD wave1=.96, α wave1=.74; Mwave2=4.47, SD wave2=.96, α wave2=.74; Mwave3=4.57, SD wave3=.96; α wave3=.75). Here, we see a slight overall increase in well-being over time. In the analyses, we initially use them as a scale, but also focus on separate items to assess their potentially different impact on news avoidance (RQ 3).

To answer the question who news avoiders are, we rely on background characteristics age (M = 54.1, SD = 15.7) gender (50.5% female) and education (seven categories, ranging from no/primary education to obtained university degree, M = 4.68, SD = 1.53) that the research company provided, as well as on the question “When you consider your own political views, where would you position yourself?” (10-point scale, ranging from left (1) to right (11), M = 5.92, SD = 2.39).

Study 2

The second panel survey was conducted by the same research company (see Bakker, van der Wal, and Vliegenthart Citation2020). The first wave was fielded on April 10, 2020, and sent out to 3,750 potential respondents, again stratified by gender, age, region and education level. Of these, 1,742 respondents completed the survey before April 20 (response rate= 49,8%). The second wave was in the field between April 30 and May 11 and yielded 1,423 responses (retention rate = 81.7%). The third wave (May 25 until June 3) resulted in 1,241 responses (retention rate = 87.2%). The final wave was in the field between June 29 and July seven had a retention rate of 87.3%. A total of 1,084 completed all four surveys of Study 2.

Measures

For the fourth research question, we rely on the data from the second panel survey. Here, news avoidance is measured with the following three items (seven point scale, second and third reversely coded to capture avoidance):

Since the start of the Corona-crisis I avoid the news more often;

Since the start of the Corona-crisis, I read, listen or watch more news;

Since the start of the Corona-crisis I use more different news sources.

(Mwave1=3.45, SD wave1=1.55, α wave1=.62; Mwave2=3.76, SD wave2=1.52, α wave2=.62; Mwave3=3.95, SD wave3=1.45; α wave3=.58; Mwave4=4.07, SD wave4=1.40, α wave4=.57).

Here we find a clear upward trend: while in the earlier weeks of the crisis, people reported to consume more news and refraing from news avoidance, we see a slight yet consistent increase in avoidance over time.

In this survey, we focused on perceived general well-being, instead of one that is explicitly related to news use. Inspired by the mental well-being subscale developed by Vander Zee et al. (Citation1996), we used the following four self-reported items to capture well-being (seven point scale, first and third question reversely coded):

How often during the past four weeks did you feel very nervous?

How often during the past four weeks did you feel calm and peaceful?

How often during the past four weeks did you feel down and gloomy?

How often during the past four weeks did you feel happy?

(Mwave1=5.06, SD wave1=.80, α wave1=.81; Mwave2=5.13, SD wave2=.80, α wave2=.81; Mwave3=5.20, SD wave3=.79; α wave3=.82; Mwave4=5.24, SD wave4=.82, α wave4=.83). Here, we find a slight and consistent increase in perceived well-being over time, which reflects that that the stress and uncertainty caused by the Covid-19 circumstances somewhat decreased in the summer when the number of infections was rather minimal.

Analysis and Models

RQ1 (Study 1)

To provide insights into the development of news consumption and avoidance, we present descriptive statistics and developments over-time from the first survey. Here, we rely on means and percentages for all questions. For illustrative purposes, in some instances we recoded our 7-point scales into three broader categories “disagree” (1–3), “neutral” (4), and “agree” (5–7).

RQ2 (Study 1)

To answer the question which people are more prone to avoid the news, we rely on the data from the first wave – using the news avoidance scale as a dependent variable and age, gender, education and political orientation as independent variables in an ordinary least squares regression model.

RQ3 (Study 1)

To assess the antecedents of news avoidance, we first estimate two OLS regression models where we predict news-related well-being and news avoidance, each based on its own value in the previous wave (lagged dependent variable) as well as the other variable, also from the previous wave. To account for heterogeneity, i.e., variance in the dependent variable that cannot be accounted by the included variables in the model, we add fixed effects for each respondent. In that way, we remove all inter-individual variance and focus on over-time, intra-individual variance. This provides a first indication whether, overall, the items that are grouped under news-related well-being are indeed antecedents, rather than consequences, of news avoidance.

In a second step, we add the separate items that compose the news-related well-being (lagged) to a random effects model including the same background characteristics as used to answer RQ 2 as well as a lagged dependent variable. This model demonstrates the potential impact of specific considerations and assesses the degree to which they improve our understanding of news avoidance beyond individuals’ background characteristics.

RQ4 (Study 2)

Looking at the relationship between news avoidance and general well-being, relying on the second panel survey, we use the fixed effects models as for the initial part of RQ 3.

Results

RQ1: How does the public's news consumption and avoidance develop during the pandemic?

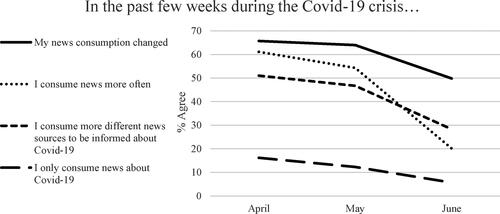

During the first four months of the Covid-19 crisis we studied the news consumption and avoidance behavior of the public in the Netherlands to understand how news consumption and avoidance develops during the pandemic. Consistent with our expectations—following media defense theory and the uncertainty reduction theory—people’s news consumption changed considerably in the beginning of the crisis. A large part of the panel members indicated that their news consumption changed in the first wave (65.7%) and actually increased: 61.1% stated they consumed news more often. Interestingly, not only did people consume more, but 51% stated they consumed a varied number of news sources. As the crisis developed, and policy on measurements to contain the virus softened, this tendency to consume more news decreased (see ).

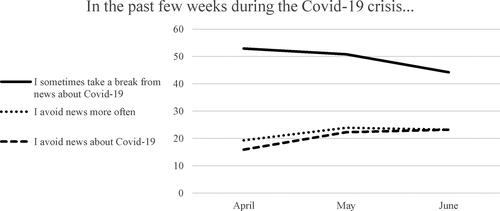

Simultaneously, we see that although some people say they use more news and sources in April, more than half of the participants (52.9%) also state they took a break from the news about Covid-19, but this decreases to 44.2% while the pandemic develops (see ). While one part of the public has a need to be informed in the beginning of the crisis, there is a similar share of the audience that feels the urge to take a break from all the news on the developments of Covid-19. At the same time, we see an increase in news avoiding behavior. Both general news avoidance (19.3%) and news avoidance on Covid-19 in April (15.9%) show an increase to 23.2 in June (see ).

Concluding, we can state that while there was initial increase in news consumption, and individuals consult a diverse range of news sources, following is a rise in news avoidance during the first few months of the Covid-19 pandemic.

RQ2 Who Avoids the News?

presents the results from the regression analysis that predicts the level of news avoidance. Results reveal that age affects news avoidance negatively: News avoidance occurs more often among younger people. Regarding gender, we find most news avoidance among females. Education has no effect. The influence of political orientation is only marginally significant and indicators that the more right-wing a person consider her/himself, the less (s)he avoids the news. It is important to note that effects are small and background characteristics can only account for a very limited share of the variance in news avoidance. This is clearly reflected in the low R2 (.02), as well as in the small standardized regression coefficients (beta’s).

Table 1. Explaining news avoidance.

RQ3 Why Do People Avoid the News?

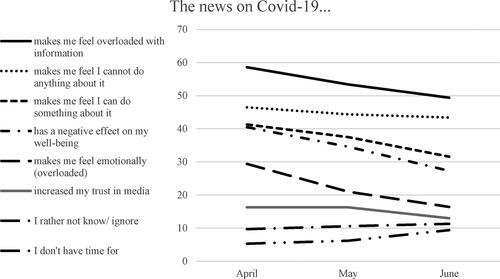

In all three panel surveys, respondents were asked how they felt about the news on Covid-19 (see ). Almost 60% of the people felt overloaded with information in the beginning of the crisis. However, while the crisis evolved this feeling somewhat weakend: By June, it is 49.4% of the sample who indicates to feel overloaded. The feeling of powerlessness (see also Nielsen et al. Citation2020; Toff and Palmer Citation2019) was also experienced by almost half of the respondents: Between 48 and 44% of the sample had the feeling they can’t do anything about the crisis (low efficacy). The feeling that news consumption has a negative effect on their well-being and they are emotionally overloaded, also both decreased as the crisis continues.

In , we present the results from our fixed-effects panel models that assess the mutual relationships between news avoidance and news-related well-being. We find evidence that well-being affects avoidance, and not the other way around. The negative coefficient (b = −.10) indicates that when people feel less well about news, they will avoid the news more often. Thus, when people have the impression that the news have a negative impact on their well-being or that it harms their efficacy, people may indeed decide to avoid this news coverage. The effect in the opposite direction (-.03) was not significant: Thus, news avoidance on itself does not affect the impressions people have of news media’s influence on their well-being. Note that the negative coefficients from the lagged dependent variables can be attributed to the simultaneous inclusion of fixed effects (dummies for each respondent), that correlate with those variables.

Table 2. The relationship between news avoidance and news-related well-being.

As we can indeed consider the items as grouped under news-related well-being antecedents, rather than consequences, the question how they individually impact news avoidance becomes relevant. We recoded items when needed to have higher scores reflecting higher levels of positivity. The random effects model presented in provides an answer.

Table 3. Understanding news avoidance.

We find that four considerations contribute significantly to news avoidance, all in the expected direction. When people feel emotionally charged, have lost trust in news media, feel the need to ignore news and feel overloaded, they are avoiding the news more in the subsequent period. Efficacy and more general well-being do not matter significantly. It seems to be direct considerations about news quality, and in particular emotions and feelings that the news yields make that people tune out. We see that, after including those items, the effects of individual background characteristics are insignificant, with the exception of age. The model provides a decent level of explained variance (R-squared is .52), though the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable is of key importance here and the explained variance only goes up .02 with the inclusion of the various considerations (from .50 to .52).

RQ4 the relationship between news avoidance and well-being during the pandemic

Finally, we present a model from our second panel survey to assess the relationship between news avoidance and general well-being. We find no effect of general mental well-being on news avoidance (): Thus, irrespective of people feel, this does not necessarily lead to more or less news avoidance. However, an effect in the opposite direction has been found: News avoidance affects well-being. The positive coefficient (b = .02) indicates that if people avoid the news more, their general well-being improves slightly. This finding shows that those who opt for news avoidance to protect their mental well-being might make the right choice: After all, those who did not avoid the news during the Corona pandemic, were confronted with relatively stronger decreases of mental well-being.

Table 4. The relationship between news avoidance and mental well-being.

Discussion

The Covid-19 pandemic has shown to not only be hazardous to people’s physical health but has also created an infodemic: An overload of information is shared online and might contain misinformation and even lead to the rise of possible conspiracy theories. At the same time, in a crisis people feel the need to become informed about the causes and consequences of the crisis. This study indeed shows that in the first few months of the pandemic in the Netherlands, people consumed more news and looked for information in a variety of sources, both offline- and online. However, while the news consumption increased, we also saw an increase in people avoiding the news, including news about the pandemic. Moreover, a large number of people also felt the need to take a break from the news. Reasons for this tuning out have largely to do with the overload of information that people are confronted with and in particular the negative feelings people experience when consuming the news. The findings are similar to an ongoing research on news consumption and news avoidance in the UK during the Covid-19 crisis (Kalogeropoulos et al. Citation2020b), where trends are observed of increasing news consumption while also increases in news avoidance. These findings show that indeed an information overload can lead to news fatigue, and, consequently, leads to news avoidance, while at the same time people feel a need for being informed (see also Song, Jung, and Kim Citation2017).

Our study takes a step further to understand how news avoidance is related to people’s mental well-being. It points to the notion that the abundance of news coverage on Covid-19 that is presented on a range of media platforms is sometimes just too much for people to still absorb. And the people who decide to tune out, subsequently, also experience a positive effect on their general mental well-being. This is a new insight that aligns with previous findings from other fields (e.g., Psychology) that news exposure about dramatic events may evoke stress reactions and negative emotions (Schuster et al. Citation2001; Shoshani and Slone Citation2008). Thus, it is not just that consuming news negative affects citizens’ mental well-being over time (Boukes and Vliegenthart Citation2017); the effects also works in the opposite direction with less news consumption enhancing levels of well-being. A concrete advice could thus be—for individual people, but also for public health officials—to encourage citizens to consume fewer news, or only at specific times (e.g., Only in the morning), in times of crises when they feel overwhelmed by the situation. Instead, they could tune in to entertainment programming that may achieve media-induced recovery, increased psychological well-being, and higher levels of vitality (Rieger et al. Citation2014).

These results point towards a dilemma for the citizen as to how much he or she should consume news during a crisis. It seems to be about striking a balance between consuming enough news to be well-informed while simultaneously not consuming too much to avoid detrimental effects on mental well-being. At the same time, this study might indicate that people are increasingly aware of the fact that news is out there all the time and that it might be healthy to sometimes take a break. In current online era, in which our media landscape is characterized by a high choice of mainly online channels and platforms, people might increasingly decide to not consume news or at least not all the time.

Uncertainty reduction theory has been clearly applicable during the crisis of the 9/11 attacks, which occurred at the beginning of the online era in which people felt the need to consume more news to inform themselves (Boyle et al. Citation2004). The Covid-19 pandemic is an enduring crisis that takes place in a more extreme version of the high-choice online media society and this might explain why people increasingly make the choice to sometimes take a break from the news. The more there is to choose from, the more people might decide not to consume. While this study shows that people are dependent of the news media to be informed, particularly in a crisis, the fact that this pandemic is more enduring over a longer period, this might also explain the increase in news avoidance over time. At the same time, we should also take into account that the act of news avoidance is not always an active or intentional behavior that people choose to do. As Skovsgaard and Andersen (Citation2020) point out, people might not have an aversion for news, but with so much to choose from, people might prefer other media content over news. And, in a crisis, this especially could be true.

While this study provides a better understanding on how news avoidance evolves over time, it does have some limitations. First, the study took place during the first four months of the pandemic. These four months or the first wave of infections disrupted everyone’s lives, threatening our health, economics and social life. News coverage was 24/7 with live blogs having a permanent place on the home page on practically every news site, press conferences broadcasted, and news media providing daily figures of the deaths and infections. While this study shows a trend of four months, it does not give a picture on how news use and avoidance evolve in concordance with how the full pandemic evolves. In other words, can we actually see a decrease in news avoidance in the summer of 2020 and increase in the fall in relation to the decline and rise of infections and to different government measures? Second, this study focuses on news behavior in one particular country, the Netherlands. While the study shows similarities with the news behavior in the UK (Kalogeropoulos et al. Citation2020b), the results do not give an overall picture of news avoidance behavior during the Covid-19 pandemic. Each country in Europe took different measures to fight the pandemic. While some countries had a complete lock down, the Netherlands took less drastic measures. Also, the number of deaths varied tremendously per country.

Nevertheless, this study does provide a better understanding of news avoidance behavior during such an impactful crisis as Covid-19. While up till now research on mental well-being was much correlated with news use, this study provides empirical causal relationship between news avoidance and mental well-being.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Bert Bakker and Amber van der Wal for their help with fielding the longitudinal survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bakker, B. N., A. van der Wal, and R. Vliegenthart. 2020. “COVID-19 Panel Study in The Netherlands.” Open science framework. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/KWZ7A.

- Ball-Rokeach, S. J. 1985. “The Origins of Individual Media-System Dependency: A Sociological Framework.” Communication Research 12 (4): 485–510.

- Berger, C. R., and R. J. Calabrese. 1975. “Some Explorations in Initial Interaction and beyond: Toward a Developmental Theory of Interpersonal Communication.” Human Communication Research 1 (2): 99–112.

- Boczkowski, P. J., and E. Mitchelstein. 2010. “Is There a Gap between the News Choices of Journalists and Consumers? A Relational and Dynamic Approach.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 15 (4): 420–440.

- Bos, L., S. Kruikemeier, and C. de Vreese. 2016. “Nation Binding: How Public Service Broadcasting Mitigates Political Selective Exposure.” PLoS One 11 (5): e0155112.

- Boukes, M., A. Damstra, and R. Vliegenthart. 2021. "Media effects across time and subject: How news coverage affects two out of four attributes of consumer confidence." Communication Research 48 (3), 454–476.

- Boukes, M., and R. Vliegenthart. 2017. “News Consumption and Its Unpleasant Side Effect: Studying the Effect of Hard and Soft News Exposure on Mental Well-Being over Time.” Journal of Media Psychology 29 (3): 137–147.

- Boyle, M. P., M. Schmierbach, C. L. Armstrong, D. M. McLeod, D. V. Shah, and Z. Pan. 2004. “Information Seeking and Emotional Reactions to the September 11 Terrorist Attacks.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 81 (1): 155–167.

- Chyi, H. I., and M. J. Yang. 2009. “Is Online News an Inferior Good? Examining the Economic Nature of Online News among Users.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 86 (3): 594–612.

- Costera Meijer, I., and T. Groot Kormelink. 2015. “Checking, Sharing, Clicking and Linking.” Digital Journalism 3 (5): 664–679.

- Edgerly, S. 2015. “Red media, blue media, and purple media: News repertoires in the colorful media landscape.” Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 59 (1): 1–21.

- Edgerly, S. 2017. “Seeking out and Avoiding the News Media: Young Adults’ Proposed Strategies for Obtaining Current Events Information.” Mass Communication and Society 20 (3): 358–377.

- Edgerly, S. 2021. “The Head and Heart of News Avoidance: How Attitudes about the News Media Relate to Levels of News Consumption.” Journalism. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849211012922.

- Edgerly, S., K. Thorson, E. Thorson, E. Vraga, and L. Bode. 2018. “Do Parents Still Model News Consumption? Socializing News Use among Adolescents in a Multi-Device World.” New Media & Society 20 (4): 1263–1281.

- Eppler, M. J., and J. Mengis. 2004. “The Concept of Information Overload: A Review of Literature from Organization Science, Accounting, Marketing, MIS, and Related Disciplines.” The Information Society 20 (5): 325–244.

- Granow, V. C., L. Reinecke, and M. Ziegele. 2018. “Binge-Watching and Psychological Well-Being: Media Use between Lack of Control and Perceived Autonomy.” Communication Research Reports 35 (5): 392–401.

- Kalogeropoulos, A. 2017. News Avoidance. In Reuters Digital News Report, 40–41. Accessed 21 October 2020. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital20News20Report20201720web_0.pdf.

- Kalogeropoulos, A., R. Fletcher, and R. Klein Nielsen. 2020a. Initial surge in news use around coronavirus in the UK has been followed by significant increase in news avoidance. UK COVID-19 news and information project (third factsheet). Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. May 19. Accessed 21 October 2020. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/initial-surge-news-use-around-coronavirus-uk-has-been-followed-significant-increase-news-avoidance

- Kalogeropoulos, A., R. Fletcher, and R. Klein Nielsen. 2020b. “News avoidance in the UK remains high as lockdown restrictions are eased.” July 28. Accessed October 21, 2020 https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2017/news-avoidance-2017/

- Lades, L., K. Laffan, M. Daly, and L. Delaney. 2020. “Daily Emotional Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” British Journal of Health Psychology 25 (4): 902–911.

- Lee, A. M. 2013. “News Audiences Revisited: Theorizing the Link between Audience Motivations and News Consumption.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 57 (3): 300–317.

- Lowrey, W. 2004. “Media Dependency during a Large-Scale Social Disruption: The Case of September 11.” Mass Communication and Society 7 (3): 339–357.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, and R. Kleis Nielsen. 2019. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-06/DNR_2019_FINAL_1.pdf.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, D. Levy, and R. Kleis Nielsen. 2017. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Available at https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital%20News%20Report%202017%20web_0.pdf; http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2017/.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, D. Levy, and R. Kleis Nielsen. 2017. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Schulz, S. Andi, and R. Kleis Nielsen. 2020. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/DNR_2020_FINAL.pdf.

- Nielsen, R. K., R. Fletcher, N. Newman, J. S. Brennen, and P. N. Howard. 2020. Navigating the ‘Infodemic’: How People in Six Countries Access and Rate News and Information about Coronavirus. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Palmer, R., and B. Toff. 2020. “What Does It Take to Sustain a News Habit? The Role of Civic Duty Norms and a Connection to a" News Community" among News Avoiders in the UK and Spain.” International Journal of Communication 14: 1634–1653.

- Prior, M. 2007. Post-Broadcast Democracy: How Media Choice Increases Inequality in Political Involvement and Polarizes Elections. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Reinecke, L., J. Klatt, and N. C. Krämer. 2011. “Entertaining Media Use and the Satisfaction of Recovery Needs: Recovery Outcomes Associated with the Use of Interactive and Noninteractive Entertaining Media.” Media Psychology 14 (2): 192–215.

- Rieger, D., L. Reinecke, L. Frischlich, and G. Bente. 2014. “Media Entertainment and Well-Being—Linking Hedonic and Eudaimonic Entertainment Experience to Media-Induced Recovery and Vitality.” Journal of Communication 64 (3): 456–478.

- Schrøder, K., and M. Blach-Ørsten. 2016. “The Nature of News Avoidance in a Digital World.” Reuters Digital News Report. https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/essays/2016/nature-news-avoidance-digital-world/.

- Schuster, M. A., B. D. Stein, L. Jaycox, R. L. Collins, G. N. Marshall, M. N. Elliott, A. J. Zhou, D. E. Kanouse, J. L. Morrison, and S. H. Berry. 2001. “A National Survey of Stress Reactions after the September 11, 2001, Terrorist Attacks.” The New England Journal of Medicine 345 (20): 1507–1512.

- Shehata, A. 2016. “News habits among adolescents: The influence of family communication on adolescents' news media use—evidence from a three-wave panel study.” Mass Communication and Society 19 (6): 758–781.

- Shoshani, A., and M. Slone. 2008. “The Drama of Media Coverage of Terrorism: Emotional and Attitudinal Impact on the Audience.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 31 (7): 627–640.

- Skovsgaard, M., and K. Andersen. 2020. “Conceptualizing News Avoidance: Towards a Shared Understanding of Different Causes and Potential Solutions.” Journalism Studies 21 (4): 459–476.

- Song, H., J. Jung, and Y. Kim. 2017. “Perceived News Overload and Its Cognitive and Attitudinal Consequences for News Usage in South Korea.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 94 (4): 1172–1190.

- Strömbäck, Jesper, Yariv Tsfati, Hajo Boomgaarden, Alyt Damstra, Elina Lindgren, Rens Vliegenthart, and Torun Lindholm. 2020. “News Media Trust and Its Impact on Media Use: Toward a Framework for Future Research.” Annals of the International Communication Association 44 (2): 139–156.

- Toff, B., and A. Kalogeropoulos. 2020. “All the News That’s Fit to Ignore: How the Information Environment Does and Does Not Shape News Avoidance.” Public Opinion Quarterly 84 (S1): 366–390.

- Toff, B., and R. A. Palmer. 2019. “Explaining the Gender Gap in News Avoidance: “News-is-for-Men” Perceptions and the Burdens of Caretaking.” Journalism Studies 20 (11): 1563–1579.

- Trilling, D., and K. Schoenbach. 2013. “Skipping Current Affairs: The Non-Users of Online and Offline News.” European Journal of Communication 28 (1): 35–51.

- Vander Zee, K. I., R. Sanderman, J. W. Heyink, and H. de Haes. 1996. “Psychometric qualities of the RAND 36-item health survey 1.0: A multidimensional measure of general health status.” International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 3 (2): 104–122. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0302_2

- Woodstock, L. 2014. “The News-Democracy Narrative and the Unexpected Benefits of Limited News Consumption: The Case of News Resisters.” Journalism 15 (7): 834–849.

- Zarocostas, J. 2020. “How to Fight an Infodemic.” The Lancet 395 (10225): 676.

- Zillmann, D. 1991. “Television Viewing and Physiological Arousal.” In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Responding to the Screen: Reception and Reaction Processes, 103–133. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.