Abstract

Social media have become conduits through which audiences can challenge elites in media and politics. Recent updates to cascading activation, originally developed to explain how frames flowing from powerful figures gain public dominance, give greater theoretical scope for audiences to exert influence. Yet empirical understanding of how and in what circumstances this happens with respect to agenda-setting—another core media effect—is not well-developed, especially given the affordances of digital technologies. We address this gap by connecting theorization on cascades to developments in intermedia agenda-setting. Specifically, we analyze the dynamics surrounding the perceived reluctance by ARD-aktuell, the newsroom of Germany’s public broadcasting consortium, to use its prime-time broadcast “Tagesschau” to report the arrest of a refugee accused of murdering a German woman in December 2016. By presenting finely grained timelines linking content analysis of 5,409 Facebook comments with Tagesschau editorial responses and parallel media coverage of this event, we contribute further conditions under which audience-informed cascades may occur: notably, when publicly funded news organizations are involved, and the issue at stake invokes both domestic and international aspects which sustain disagreement.

On December 5, 2016, the German Christian Democratic Union (CDU) met for a two-day party convention in Essen to re-elect Angela Merkel as its chair. The event was overshadowed by the recent arrest two days earlier of an Afghan refugee accused of murdering Maria Ladenburger, a university student, in October 2016. That evening, during the main evening broadcast (“Tagesschau”) of Germany’s regional public service network, Merkel was asked to comment on the significance of this event.Footnote1 She stated that, although the main suspect was a refugee, “we cannot reject an entire group because of this, just like we usually cannot infer anything about a group from an individual. It still remains a tragic case that has to be investigated and that we have to talk about openly” (Tagesschau Citation2016a). The case of “Maria L.” served as a lightning-rod for subsequent German press coverage and political rhetoric that has continued to emphasize the alleged threat of refugees to national security (Holzberg, Kolbe, and Zaborowski Citation2018).

Established concepts in press-state relations, notably “cascading activation” (Entman Citation2003), would prioritize elites’ dominant roles in shaping the kinds of news that audiences eventually encounter. Analyzing the dynamics of media coverage about “Maria L.” through this lens might suggest that the Tagesschau was independently eliciting Merkel’s position on an already-salient issue. While an agenda-setting analysis proceeding from this moment might provide valid evidence of this, we argue it would be incomplete. Crucially, this would downplay the possibility for, and significance of, audience-led debates occurring both online and through competing media before Merkel’s intervention on broadcast television.

Recent theoretical modifications to the cascading activation model (Entman and Usher Citation2018), as well as large-scale empirical research showing the dynamics of public attention to issues on social media (e.g., Boynton and Richardson, Jr. Citation2016), acknowledge that digital technologies and platforms open up alternative pathways whereby audiences contribute to public agendas that, in turn, might spill-over into more conventional cascades. Indeed, the reality of interaction among media types strongly characterizes these developments: there is growing consensus that the causal mechanisms implied by agenda-setting may be more mutual than originally theorized, especially in increasingly diverse media environments (Neuman et al. Citation2014). Yet understanding about how and under which circumstances such interaction might happen is limited, partly due to the lack of granular detail in existing empirical work that tends to focus on identifying macro-level media dynamics spanning months or years.

In response, we address two key questions: (1) how did the volume and content of online discussions about Tagesschau’s editorial policies towards the Maria L. case change between December 3-5, and (2) how did these shifts relate to the Tagesschau’s own actions? Drawing upon an original dataset of 5,409 Facebook comments made in response to Tagesschau news postings over these three days, we document the interactions between viewers and the broadcaster in minute-by-minute detail. We show how moderators addressed viewers’ initial online criticisms of the broadcaster’s decision not to cover this event on its televised newscast. Yet commenters perceived that the Tagesschau was mishandling the situation, which contributed to further expressions of dissatisfaction. This public reaction became a story itself, eventually being picked up and amplified by other press outlets that placed Tagesschau’s editorial policies under scrutiny. Tagesschau staff responded to criticism in increasingly visible ways, culminating in a Facebook Live question and answer session involving its editor-in-chief, as well as subsequently soliciting Merkel’s response to the issue. These decisions, we argue, were particularly tied to Tagesschau’s unique position as a public broadcaster funded by license fees: the combination of its legal responsibility to report in neutral and nonpartizan ways (Steiner, Magin, and Stark Citation2019) and continued status as the most-trusted media brand in Germany (Newman et al. Citation2021) likely contributed to Tagesschau editorial staff being especially sensitive to allegations and perceptions of biased reporting.

Our study contributes to a growing body of work that examines how digital media are changing existing press-state relationships, particularly those involving publicly funded news organizations (Cushion et al. Citation2018). Specifically, it develops understanding about the circumstances in which audiences contribute to agendas in directions theorized by cascading activation and in ways that involve multiple media. Moreover, we demonstrate how this process can happen very quickly—within 72 hours—and could be overlooked in larger-scale media studies that aggregate weeks, months, or even years of coverage. Finally, our results illustrate the importance of treating “media” as a heterogeneous group in empirical research, speaking to growing interest in intermedia agenda-setting (Guo and Vargo Citation2017).

Revisiting the Role of Audiences and Social Media in Cascading Activation

Our theoretical argument follows two lines. First, audiences can contribute to agenda-setting dynamics involving established media through their feedback on social media platforms. Second, this interaction is particularly, though not exclusively, salient in cases involving publicly funded media that is reliant on and sensitive towards being perceived as serving public rather than overtly political or commercial interests. Therefore, we develop understanding about the circumstances in which audiences use social media platforms to flatten press-state hierarchies expressed by models of cascading activation. By doing so, we aim to connect scholarship on cascades, which is usually concerned with the ways that elites set and convey dominant news frames (as opposed to agendas), to work on (intermedia) agenda-setting which does not use the language of cascades yet nevertheless attempts to document the dynamics among audiences and different media.

Until recently, scholarship on press-state relations tended to view audiences as mostly passive recipients of agendas originating from more powerful elites, be they in government or media organizations. When it comes to deciding which issues to cover (a form of agenda-setting), journalists pay particular attention to (or “index”) the range of perspectives expressed by official governmental sources (Bennett Citation1990). This is especially the case in domains with few alternative sources of information, such as coverage of foreign policy or international scandals (Althaus et al. Citation1996; Bennett, Lawrence, and Livingston Citation2006). Even in fast-moving situations involving live reporting, studies of legacy press outlets suggest that journalists still tend to prioritize government sources as “gatekeepers” (Livingston and Bennett Citation2003) of which kinds of statements are published. These assumptions suggest a relatively stable hierarchy, captured by the model of “cascading activation” (Entman Citation2003) in which information flows from elites through media organizations and onwards to audiences. Originally, Entman used this model with reference to framing (rather than agenda-setting) to highlight how the ability to successfully insert a preferred frame not only varies across distinct levels of media systems, but also primarily lies with elites who “possess the greatest strength” and “enjoy the most independent ability” (Entman Citation2003, 420) to do so.

However, more recent work has revised this model of cascades in response to changes brought about by social media. Specifically, audiences now have greater scope to exert influence upwards, even while political and legacy media elites sustain a given cascade in their roles as “pump-valves” (Entman and Usher Citation2018). To be clear, earlier work on cascading activation had left this possibility open, even if it downplayed the likelihood of audience-generated frames having larger impacts compared to elites’ own frames (Entman Citation2003). Now, however, there is an explicit acknowledgement that cascades may involve different points within, as well as flow in multiple directions across media systems that connect elites, media organizations, and audiences. What is more, users themselves can act as “secondary gatekeepers” (Singer Citation2014) of news content by selecting what to share and re-post—a process that is also marked by discoverability algorithms (Lee and Tandoc Citation2017) and the affordances of platforms themselves (e.g., Wallace Citation2018). While this theoretical development regarding directionality is welcome, it raises the question of how such cascades might travel.

Here, the concept of intermedia agenda-setting provides a potential answer by highlighting possible pathways for cascades. Specifically, social media platforms serve as conduits for viewers’ interests and perspectives, making them visible to competing media organizations as well as political elites (Boynton and Richardson, Jr. Citation2016). As such, they have become established players in their own rights insofar as they enable audiences to express themselves and react to legacy media coverage (Aruguete and Calvo Citation2018). Yet how and to what extent they actually impact broader news agendas likely depends on case-specific temporal, political, and media factors. For example, during the 2012 US Presidential election campaign, Conway, Kenski, and Wang (Citation2015) found clear relationships among Twitter and mainstream media agendas on several issues, whereas Skogerbø and Krumsvik (Citation2015) did not find substantial intermedia agenda-setting effects among candidates’ social media posts and regional newspapers during the 2011 Norwegian local election campaigns. This lends further reason for the kind of granular and case-specific analysis we present in this article.

These developments motivate us to revisit cascading activation, particularly its micro-level dynamics, by bringing its theoretical implications regarding the potential power of audiences into conversation with the concept of intermedia agenda-setting. After all, audience interactions are consequential for journalism practice in digital contexts (e.g., Heise et al. Citation2014; Loosen and Schmidt Citation2012; Peters and Witschge Citation2015). Yet there is a striking lack of understanding of how audience-led cascades might develop and travel across media, and which factors might support this process. Indeed, as Neuman et al. (Citation2014, 211) reflect on their own large-scale media analysis that uses 24-hour periods as the unit of analysis, they acknowledge how interactions among audiences and other actors “happen in a matter of minutes rather than days.” In response, our finely grained analysis demonstrates how audience engagement on social media platforms with legacy (public) broadcast media spills over to other competing media and contributes to decisions by that same broadcast media about its own news agenda. This extends existing theory by empirically developing further conditions for audience-driven cascades.

Study Context: Refugees in German Media and Public Opinion

Before we present our media analysis, it is important to briefly provide context about refugees in German media coverage and public opinion around the time of the “Maria L.” case. Public narratives within European media coverage of the “refugee crisis” shifted rapidly during 2015-16. Georgiou and Zaborowski (Citation2017) identified three periods of what they call “careful tolerance” (July September 2015), “ecstatic humanitarianism” (September-November 2015), and “fear and securitization” (November 2015 onwards). This broad comparative pattern—particularly the turn towards security concerns and negative framings of refugees and migrants—has been observed in the German press (Vollmer and Karakayali Citation2018) as well as countries such as Austria which display similarities in press-state relationships to Germany (Greussing and Boomgaarden Citation2017).

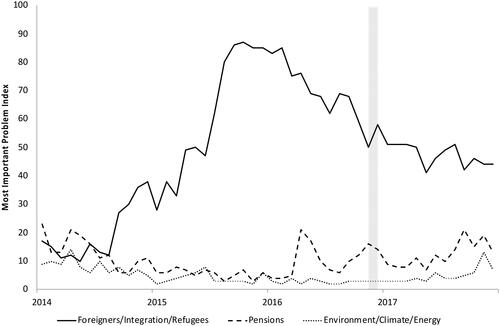

Meanwhile, public perceptions of refugees underwent significant change during this period. shows how concern about refugees dramatically rose between 2014-17 in relation to two of the other most-frequently named issues (pensions and the environment).Footnote2 In January 2014, 17% of Germans named “foreigners/integration/refugees” as one of the most important problems facing Germany—still within the top five, but not especially different from other salient issues. However, concern grew during 2015, most notably by 33 percentage points from June (47%) to August (80%). Specifically for our case, between November and December 2016 concern about refugees rose from 50% to 58% as indicated in the shaded area (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen Citation2020).

Figure 1. Most Important Problem Index (Germany), 2014-17.

Notes: MIP data come from “Wichtige Probleme in Deutschland,” Forschungsgruppe Wahlen Politbarometer (2020). When more than one survey was available in a given month, the latest one was used to represent that month. The shaded area indicates the study period of December 2016.

These dynamics in media coverage and public concern are important for building and contextualizing our story of how audiences relate to news producers in three ways. First, our focus on an ARD program highlights how differences among media organizations themselves matter for understanding the circumstances in which audiences might successfully initiate their own cascades. ARD holds a distinct position within the German media environment. In 2016, not only was it the only media brand that a majority of Germans reported using either on a weekly basis or as their main source of news (Newman et al. Citation2016), but it also had (and continues to have) unparalleled reach as the publicly funded consortium of regional broadcasters. Being primarily funded by license fees, these public broadcasters must offer basic provision to all citizens while representing diverse opinions and viewpoints across German society in their programming (Schulz et al. Citation2008; Steiner, Magin, and Stark Citation2019). These features present unique constraints on ARD’s editorial decisions while also opening opportunities and responsibilities for reaching all of Germany.Footnote3

Second, our case occurs within a context when audiences were already concerned about refugees’ impacts and media were producing largely negative coverage. This salience paralleled mostly negative attitudes towards refugees: in early 2016, nearly three-quarters (74%) of Germans considered refugees to represent more risks than opportunities in the short-term (Gerhards, Hans, and Schupp Citation2016). Meanwhile, experimental panel surveys conducted throughout 2015-16 indicated that Germans overwhelmingly disapproved of hypothetical refugees moving into their local neighbourhood (Liebe et al. Citation2018). Although we do not have individual-level data on commenters, we argue that the wider context represents a situation where audiences would be more likely to pay attention to—and, for some, engage with—news about refugees. This could be due to heightened anxiety about refugees’ impacts, a factor that studies into the psychological determinants of immigration attitudes identify as causing people to seek out (and tending to agree with) negative information (Gadarian and Albertson Citation2014).

Third, our case involves an intersection of domestic (crime and public safety) and international (refugee admission and integration) issues for German politics. Earlier press-state relations research tends to justify prioritizing elites’ roles in setting news agendas by focusing on foreign affairs reporting—a setting heavily reliant upon official sources with strong gatekeeping powers (Bennett, Lawrence, and Livingston Citation2006). By contrast, we show how audiences meaningfully interact and disagree with media organizations on issues like refugees that spam both domestic (i.e., crime and public safety) and international aspects (i.e., responses to conflict or crises). Indeed, the combination of domestic and international aspects may actually sustain further user engagement by generating tension between concerns for locally felt public order and globally orientated humanitarian norms: audiences can realistically invoke either or both priorities. We thereby echo the conclusions of recent research highlighting how the dynamics of agenda-setting, particularly the ways that media respond to each other as well as audiences and elites, likely vary among issues (Allen and Blinder Citation2018; Mulherin and Isakhan Citation2019; Neuman et al. Citation2014).

In summary, our case displays several characteristics that enable us to develop existing theories about how audiences, media, and elites relate: (1) a media organization with broad public familiarity as well as legally binding requirements for nonpartizan reporting and national reach; (2) a context in which public and media attention were already heightened, making user engagement more likely; and (3) an issue spanning domestic and international domains.

Methods and Data

Data Collection and Analysis Procedures

We analyze an original dataset of comments made in response to four Facebook posts by Tagesschau staff to the program’s Facebook page during December 3-5, 2016. Although the program hosts other online venues for discussion and comment, Facebook has remained its most popular platform: as of September 2021, over 1.9 million users “follow” its page. This mirrors broader trends in German media consumption preceding and following our study period: between 2013 and 2021, while the proportion of Germans accessing news via television declined slightly from 82% to 69%, the proportion using social media to access news grew from 18% to 31% (Newman et al. Citation2021). Within this, Facebook is the most popular (Steiner, Magin, and Stark Citation2019). What is more, around the time of our study, a sizeable proportion of German internet users (25%) reported posting comments to the Facebook sites of established media at least monthly, while 41% reported reading the Facebook comments of other users at least once a week (Ziegele et al. Citation2017).

We identified the posts by searching the Tagesschau’s Facebook posts using the keyword “Freiburg” and restricting the results to 2016. Manually inspecting the results enabled us to choose all of the posts specifically referencing this incident. Then, during March-May 2019, we collected all user comments made on these posts, their times of publication, and the number of “likes” each had received. This resulted in 5,997 comments, of which 5,409 (90.2%) were published during December 3-5 in response to the original Tagesschau posts. Our analysis focuses on this subset of comments.

To investigate how the volume and content of online discussions about the Tagesschau’s editorial stance towards the “Maria L.” case changed during this period, we used manual content analysis to identify two key aspects: whether comments were referencing Tagesschau coverage of the case, and, for comments that did, whether the comments were expressing support or disagreement with the broadcaster. The first author coded each comment as “coverage-related (1)” or “not coverage-related (0).” A further code of “supportive (1)” or “not supportive (0)” was applied to those comments initially coded as being related to coverage. Then, the second author independently coded a random sample of the comments (comprising 10% of the full sample, or 600 comments). This enabled calculation of intercoder reliability statistics, reported in . All estimates and associated 95% confidence intervals for Krippendorff’s alpha and Cohen’s kappa were above 0.80, which is a generally accepted threshold for very high levels of intercoder reliability after accounting for random agreement (O’Connor and Joffe Citation2020).Footnote4

Table 1. Intercoder reliability statistics.

Next, to address the question of how the dynamics of online comments related to Tagesschau editorial decisions, we produced a series of timelines that leveraged the high resolution of timestamps available with the dataset. Then, we overlaid the timings of known key events such as editorial statements and publications by competing media. Other scholars have used similar timelining techniques to study agenda-setting dynamics among social and legacy media (e.g., Boynton and Richardson Citation2016; Neuman et al. Citation2014). We complemented this analysis by selecting and qualitatively analyzing comments around each of these events, paying particular attention to the justifications, opinions, and claims being made. We supplemented our interpretation with additional media data, such as the contents of blogs and videos, when they were specifically referenced as part of the ongoing discussion.

Even so, our dataset has limitations arising from issues specific to doing digital media research (Zimmer Citation2010). Although we aimed to capture all comments made on Tagesschau posts regarding the “Maria L.” case before the December five newscast, we missed comments that were deleted before we collected the data. On the one hand, users may have removed their own posts. On the other hand, the Tagesschau’s own social media team may have deleted posts that it felt were offensive or otherwise violated community norms, a practice that has been documented in the German media context more broadly (Wintterlin et al. Citation2020).Footnote5 These comments’ removal likely means that we have slightly undercounted the number of negative comments. More broadly, doing digital research on and through Facebook groups (and online communities generally) introduces platform-specific challenges that can impact the scope of conclusions drawn from the data (see Rieder et al. Citation2015). Nevertheless, by focusing on concepts informed by prior theories, incorporating qualitative analysis that remained close to the data, and triangulating our results with other forms of information, we follow established practice in social scientific studies of online communication that reduces the likelihood of incorrect inference due to over-reliance on one particular form of data (Marres and Weltevrede Citation2013).

Documenting Audience Feedback with the Tagesschau on Facebook

Overall Trends in Facebook Comments

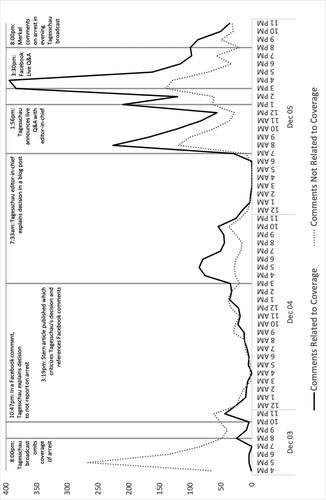

plots the number of unique comments made in response to the Tagesschau Facebook posts between December 3-5, subdivided into those referencing the organization’s editorial decisions and those referencing another aspect of the case. By this measure, engagement clearly varies during this period in ways that appear to relate to external events rather than merely capturing cyclical attention. Moreover, engagement focuses on the nature of Tagesschau coverage with the exception of the first few hours after a factual news story about the arrest of a suspect in the “Maria L.” case was published online at 4:29 PM. In the following sections, corresponding with each day of the coverage, we analyze the content and dynamics of these comments in greater detail to explore how commenters and Tagesschau staff interacted.

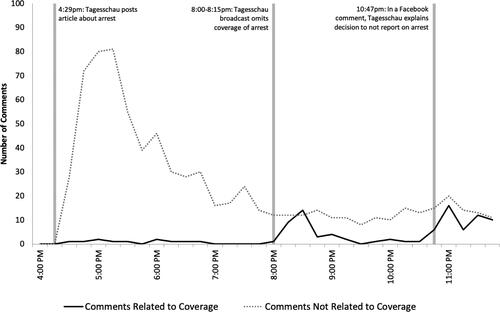

December 3: The Tagesschau Justifies Its Broadcast Silence on the “Maria L.” Case

Almost two months after the death of “Maria L.,” German police held a press conference announcing the arrest of a suspect. Private network stations, including N24 and N-TV, covered the event live (Maier Citation2016). At 4:29 PM, the Tagesschau posted an article on its website and its Facebook page (Tagesschau Citation2016b). The article, written by an ARD subsidiary SWR, included a short subheading stating that a refugee had been identified as the prime suspect. As seen in , initially there was little critique of the reporting itself in the first comments posted under the article. Rather, commenters mostly talked about the crime, expressed condolences to the parents, or praised the police for their investigative success. Debate about refugees broke out as well: while some commenters quickly blamed Merkel’s refugee-friendly policies during 2015-16 for Maria L.’s death, others argued it was impossible to draw conclusions about an entire population from a single crime.

Between 8:00-8:15 PM, during the prime-time Tagesschau broadcast which usually lasts about 15 minutes and ends with a weather report, the “Maria L.” case was not mentioned. Yet even while the Tagesschau was still covering the weather, commenters started to ask about this apparent omission. One user stated at 8:14 PM “I find it peculiar [merkwürdig] that this terrible tragedy did not find mention in today’s 8 pm edition of the television Tagesschau.” This quickly pivoted to possible political motivations: another user at 8:15 PM wrote “I find it alienating [befremdlich] that the Tagesschau did not mention the topic Freiburg with a single syllable. All major media are reporting! Why is this? Unpleasant reality [unliebsame Realität]?” Another comment posted at 8:16 PM accused the Tagesschau of “brainwashing [brainwashprogramm].”

Later that evening, at 10:47 PM in a comment to their original post, Tagesschau staff explained their decision citing four reasons: (1) the crime was only regionally relevant, and Tagesschau programming had a remit to report transregionally for all of German society, (2) the police were only reporting the arrest of a suspect, and the assumption of innocence until proven guilty applied, (3) the suspect himself was a minor, thereby requiring special protection in media coverage, and (4) the Tagesschau had already earlier reported on the press event via its website and social media pages. This reasoning sparked a wave of criticism in response that spilled over into the next morning: 171 coverage-related comments were made through 4:00 AM, of which 98.7% were critical of the editorial position. The comment attracting the most “likes” (916 in total) was posted only six minutes afterwards at 10:53 PM:

The case very well has more than regional significance since it shows that people are entering our country uncontrolled and raping and murdering. Special protection of teenagers? Which protection does a rapist and murderer deserve? It is much more the case that it doesn’t fit the image of traumatized refugees which the ARD tries to force on us.

Subsequent commenters echoed this conclusion, claiming that German public broadcasters try to frame refugees in an exclusively positive light for political gain. Other users pointed out how this perception of bias might lead to further disaffection with established news outlets and parties, and as a result motivate greater support for the AfD in the upcoming federal elections: one person said “thank you for campaigning for the AfD.”

The quantitative evidence corroborates these trends. Comments expressing views on the (lack of) coverage only rose after the initial broadcast and when Tagesschau staff explained their rationale. Moreover, the aggregate quantity of comments was relatively low compared to what would follow: only 27 unique users asked why the case was not covered. The dynamics and content of those comments point to two important observations: (1) this small group of users, who were probably already highly motivated, were able to stimulate a response from the Tagesschau’s social media team within hours, and (2) the discussion was already turning to consideration of why some stories warranted coverage over others. Perceptions of partisanship and “political correctness” would become especially salient in the coming days.

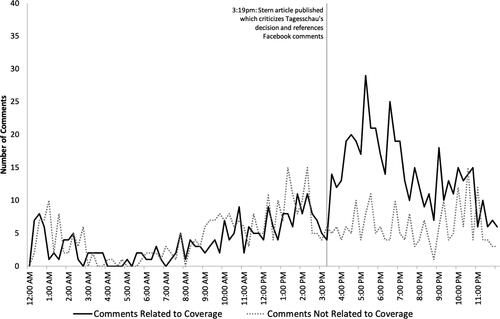

December 4: The Tagesschau Stays Silent as Cross-Media Criticism Mounts

The next day, criticism continued to grow. By 2 PM, users had posted over 200 comments critical of Tagesschau coverage. Importantly, as shown in , the proportion of comments related to the editorial decision was roughly equal to that of comments related to other aspects of the case: users were increasingly referencing the lack of coverage in the Tagesschau television segment rather than the case itself.

Then, a key moment occurred which accelerated this criticism. At 3:19 PM, the left-leaning magazine “Stern” published a story highlighting the unfolding debate on the Tagesschau’s Facebook page—the first of several media outlets to do so. Its headline stated “This is how the Tagesschau suits the fake-news instigators” (Maier Citation2016), going on to argue that the lack of coverage was only providing further fuel for right-wing populists. Soon, other German news outlets—Die Welt, Der Spiegel, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ)—followed suit with stories of their own (Frank Citation2016; Hanfeld Citation2016; Welt Citation2016). Even international press including The New York Times, The Daily Mail, and The Irish Times eventually covered the case, with the New York Times specifically referencing the Facebook comments (Eddy Citation2016; Scally Citation2016; Hall Citation2016).

These articles were significant not only because of their impact on the sheer number of comments, but also because they gave commenters external reputable sources to cite in support of their objection that the “Maria L.” case was more than just a regional issue as the Tagesschau had initially claimed. In total, users posted 58 links to other news media stories. Of these, nine comments shared links to each of the Stern and Daily Mail articles, and ten comments shared the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung article. After the Stern article’s publication, the number of comments relating to the Tagesschau’s coverage grew dramatically even while the frequency of other comments remained stable. This was facilitated by the inclusion of a link in the Stern article directly to the Tagesschau’s own Facebook post.

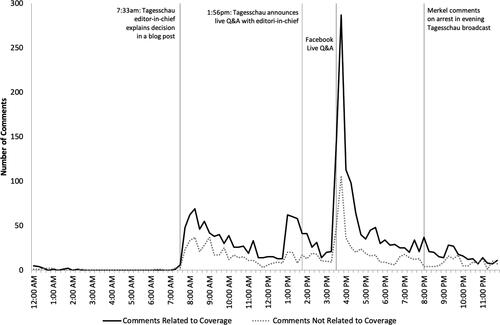

December 5: The Tagesschau Responds by Turning to Social Media

The next morning at 7:33 AM, Tagesschau staff posted a link to a blog written by its editor-in-chief Kai Gniffke. Although the blog itself is no longer available, it received a great deal of coverage in other outlets that enables us to reconstruct its main arguments (Hanfeld Citation2016). Gniffke re-iterated the main points of the original justification posted on December 3. On a practical level, he argued that Tagesschau broadcasts could not report on every homicide occurring in Germany. Moreover, as long as refugees did not stand out in crime statistics, he saw no reason to cover individual crimes such as the “Maria L.” case. He also defended Tagesschau policy of only mentioning the national origins or other identifying features of suspects if they are necessary to understand a crime.

As seen in , this statement generated further comments about the Tagesschau’s position. What is more, the level of direct engagement by Tagesschau social media staff running the Facebook page increased. On December 3, moderators had only commented three times, twice to remind users about the community standards. By contrast, moderators intervened 20 times on the post linking to Gniffke’s blog post. Qualitatively, some of these comments went beyond merely reminding users of guidelines. For example, one user commented “the people will love you again if you free yourself from the government and come back to the side of the people.” In response, a moderator stated that “we do not want to be loved, we don’t want to stand on anyone’s side. We report independently.”

With no abatement in criticism, and pressure continuing to grow, at 1:56 PM the Tagesschau announced that Gniffke would hold a Facebook live Q&A session later that afternoon at 3:30 PM. This session sparked high interest and prompted the greatest number of comments related to the coverage throughout the entire period—over eight times as many compared to the original critical response on December 3. The Facebook Live session opened with Gniffke giving an unscripted monologue:

Today, I would really really like to discuss a topic with you that deeply moved us the last couple of days since the weekend. On Saturday night, we had a Tagesschau-edition in which we didn’t mention that a suspect was arrested in Freiburg in the case of the killed student. Many people have written us since, reached out to us, other media took up the topic as well, why we didn’t report the suspect – his arrest. And, because these reactions were so intense and so numerous, we decided that we want to discuss this topic today again with you. In that sense, I ask you, send us questions, I will try to answer as many as possible in the next half-hour. And I am happy that we can have a discussion, despite all the justifiable criticism, which we have to endure. The least that you can expect from us is that we engage with it.

His statement, when placed alongside evidence of moderators’ responses in the previous hours, illustrates how Tagesschau editorial staff engaged with—and were likely impacted by—audience feedback delivered through social media as well as through parallel media coverage. Specifically, Gniffke appeared to soften the broadcaster’s original assertion that the “Maria L.” case had no national significance: now he spoke of “justifiable criticism,” and, when asked during the Q&A why the other public broadcaster Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (ZDF) had covered the case, he admitted “a different decision could have been made.” As the session ended, Gniffke announced that the “Maria L.” case would indeed be covered in that day’s Tagesthemen, but not during that evening’s Tagesschau program. He explained that Tagesthemen would cover the case “because by now such a great relevance emerged from this isolated case. Because so many people, politicians as well, spoke about it, took a stance on the issue of how to deal with refugees…now a threshold has been passed that we have a society-wide discussion.” As the case now fell within ARD’s remit, he concluded “maybe you will now think that this isn’t consistent or even that it is an admission of guilt. But we hope you don’t see it that way.”

Our analysis of these tumultuous 72 hours revealed several moments of feedback between Tagesschau staff and audiences who took to social media in expressing their views. Crucially, we found that audiences had a greater role in setting and maintaining the terms of the discussion as being squarely about the Tagesschau’s editorial policies rather than the details of the case itself. This contributes empirical evidence for the theoretical expectations about how and in which circumstances audience-led cascades might arise: although the initial number of commenters was strikingly small, the cascading process was amplified and accelerated by other media that began covering the debate, too. In other circumstances involving overtly partisan media, debates about editorial standards would not likely have mattered in the same way. However, owing to the ARD’s distinctive brand and legal obligations as a public broadcaster, these perceptions and allegations of bias—aired in an increasingly visible manner—demanded a response. Therefore, while the ARD and Tagesschau programming might be independent from political influence from above, our evidence shows how it nevertheless faces constraints from below (from audiences) and horizontally (from competing media).

Conclusion

Particularly in the absence of personal contact or experience, agendas are core means by which members of the public encounter politically consequential issues such as immigration and asylum (Blinder and Allen Citation2016). But the direction of influence has often been characterized as being mostly one-way, with audiences receiving information cascading downwards from more powerful individuals and organizations. By contrast, recent re-theorization (e.g., Entman and Usher Citation2018) acknowledges the possibility for audiences to generate their own cascades, particularly through digital means. Our study, by contributing finely grained documentation of audience interaction, provides further empirical evidence of how and in what circumstances this can occur. In our case, those circumstances involved a widely recognized public media organization bound by dual imperatives to achieve near-universal reach and to report in ways that are (at least perceived to be) nonpartisan; an ability for highly motivated users to directly engage with media staff via digital platforms, accompanied by an expectation on the part of staff to respond; and a high-salience issue spanning domestic and international domains, introducing tension as to who or what should be given authority and priority.

Furthermore, our analysis illustrates how “media organizations” mentioned within theories of press-state relations are plural, comprising heterogeneous sets of media that interact and compete. This observation has theoretical implications by providing a mechanism by which users—highly attuned and politically engaged ones, more likely than not (Ziegele et al. Citation2017)—can express and justify their dissatisfaction using feedback from other media sources. Not only does this fit with the theoretical revisions to cascading activation that give greater scope for audiences to exert influence (Entman and Usher Citation2018), but it also points to the need for distinguishing among different types of users within broad audiences (e.g., Brosius and Weimann Citation1996). Although we do not have individual-level features for commenters in our dataset, future research could productively link user characteristics with comment content and dynamics to understand which audiences are more likely to engage in this behavior—and with what motivations. Even so, our study contributes methodologically to studies of intermedia agenda-setting dynamics by illustrating the value of following arguments forwards and backwards across media types: a study focussing on coverage of “Maria L.” after it appeared on Tagesschau programming from December five would have missed the public reaction on social media that had preceding an editorial decision to place it on the program in the first place.

In our examination of how audiences might generate their own cascades, we have been careful to avoid strong claims about whether audience feedback alone caused the eventual shift in Tagesschau reporting. Indeed, possibly the key moment that accelerated criticism of the Tagesschau involved publication of the debate itself in competing news organizations. This firmly moved discussion onto editorial decision-making—both its appropriateness and motivation—and away from the details of the case. To use the alarm/patrol terminology of Amber Boydstun (Citation2013), one could argue that coverage of “Maria L.” in wider media functioned as an “alarm” that mobilized public attention around the case. Yet as we demonstrated in our analysis, part of the subsequent “patrol” activity actually involved audiences and other news organizations holding Tagesschau staff accountable for not raising their own alarm on its evening broadcast. This suggests that cascades can be sustained by groups operating at levels below and horizontal to a media organization—a conclusion that is consistent with expectations of intermedia agenda-setting.

Finally, it is worth reflecting on the practical implications and consequences of this moment in Tagesschau history, both for the news organization itself and for wider journalism practice. As of June 2021, the Tagesschau YouTube page (Tagesschau Citation2021) had displayed a pinned video that outlined its reporting criteria with explicit reference to the decision not to cover the “Maria L.” case (Tagesschau Citation2019). Yet even prior to 2016, the Tagesschau’s digital audience was already expressing its desires for both more transparency in the outlet’s news selection process and greater awareness of viewers’ own agendas of newsworthy items (Heise et al. Citation2014). After the events of the “Maria L.” case, Tagesschau staff undertook steps to engage with their critics in an initiative called “Tagesschau on Tour” (Welt Citation2018), which aimed to place key editorial staff in townhall-style conversations with members of the public. Although only two of these events took place—one in Mittweida, located in Saxony where AfD support has been especially strong, and one in Köthen, a place that had experienced heightened tensions over a number of competing immigration-related vigils and demonstrations—they were significant enough to warrant the presence of Gniffke and Jan Hofer (a main Tagesschau presenter). These events likely intended to address growing concerns over Tagesschau’s public image and relevance as a news source, a lack of credible strategies for sensitively dealing with immediate events like “Maria L.,” and longer-term disaffection among key segments of the German population—particularly those in East Germany.

Yet these concerns, and their relevance for publicly funded media, are not a uniquely German issue. Populism and anti-elite sentiment have been globally salient, particularly following the November 2016 US elections and the June 2016 UK referendum on EU membership, both of which captured international attention (Hobolt Citation2016; Rudolph Citation2021). The ARD’s decision to hold these events illustrates an awareness of how relationships between public broadcasters and audiences can quickly shift, although the long-term effectiveness of these particular initiatives in changing journalism practices is unclear.

Normatively, what does our analysis suggest for how public broadcasters should engage with audiences in a political moment characterized by affective polarization, growing skepticism towards mainstream media and outlets for expertise, and increasing segmentation of information sources? On the one hand, publicly funded media organizations potentially contribute to further polarization by choosing to cover controversial yet salient issues like asylum and refugee integration. This could endanger their existence in current form, especially in situations where they rely on broad public support through license fees. Yet on the other hand, public broadcasters’ persistence in covering these kinds of important topics maintains the possibility of presenting viewpoints that audiences may not otherwise demand. Going forward, public service media will have to continue negotiating interests and needs that sometimes conflict—with uncertain political consequences.

Acknowledgements

A version of this article was presented at the virtual 2021 International Communication Association Annual Conference (May 27-31) We would like to thank the panel members at that conference, the anonymous reviewers, and Scott Blinder for the helpful comments as the paper developed.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 “ARD aktuell” produces a bundle of news programs that include “Tagesschau,” “Tagesthemen,” and “Nachtmagazin,” all of which share staff. Since it uses the “Tagesschau” brand in its public presence, we use this name as shorthand to refer to ARD-aktuell’s national news reporting programs.

2 Although “most important issue/problem” questions are not measuring attitudes towards immigrants and refugees per se, empirical work demonstrates how (at least on immigration) both importance and problem-status are strongly correlated with negative attitudes, suggesting these indices are capturing hostility to immigrants (McLaren, Boomgaarden, and Vliegenthart Citation2018).

3 In their study of how immigration has been covered by UK media, Allen and Blinder (Citation2018) argue that non-partisan statistical agencies—part of the bureaucratic arm of the state—become intermediary “anchors” for news coverage that challenge the government. Our account differs from theirs by considering what happens when a media organization itself must act (and be seen to be acting) in non-partisan ways.

4 Best practice in calculating intercoder reliability for manual content analysis avoids relying on the percentage of agreement between two coders because some of that agreement will have happened by chance. For completeness, our percentage agreement for “related to coverage” was 0.93 (SE 0.01; 95% confidence interval of 0.91-0.95) and for “supportive or not supportive” was 0.97 (SE 0.02; 95% confidence interval of 0.93-1.00).

5 Qualitatively, we saw evidence of this (infrequent) practice: during the discussions, several commenters asked why their previous comments had been deleted.

References

- Allen, William, and Scott Blinder. 2018. “Media Independence through Routine Press-State Relations: Immigration and Government Statistics in the British Press.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (2): 202–226.

- Althaus, Scott L., Jill A. Edy, Robert M. Entman, and Patricia Phalen. 1996. “Revising the Indexing Hypothesis: Officials, Media, and the Libya Crisis.” Political Communication 13 (4): 407–421.

- Aruguete, Natalia, and Ernesto Calvo. 2018. “Time to #Protest: Selective Exposure, Cascading Activation, and Framing in Social Media.” Journal of Communication 68 (3): 480–502.

- Bennett, W. Lance. 1990. “Toward a Theory of Press-State Relations in the United States.” Journal of Communication 40 (2): 103–127.

- Bennett, W. Lance, Regina G. Lawrence, and Steven Livingston. 2006. “None Dare Call It Torture: Indexing and the Limits of Press Independence in the Abu Ghraib Scandal.” Journal of Communication 56 (3): 467–485.

- Blinder, Scott, and William Allen. 2016. “Constructing Immigrants: Portrayals of Migrant Groups in British National Newspapers, 2010-2012.” International Migration Review 50 (1): 3–40.

- Boydstun, Amber. 2013. Making the News: Politics, the Media and Agenda Setting. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Boynton, G. R., and Glenn W. Richardson. Jr. 2016. “Agenda Setting in the Twenty-First Century.” New Media & Society 18 (9): 1916–1934.

- Brosius, Hans-Bernard, and Gabriel Weimann. 1996. “Who Sets the Agenda: Agenda-Setting as a Two-Step Flow.” Communication Research 23 (5): 561–580.

- Conway, Bethany A., Kate Kenski, and Di Wang. 2015. “The Rise of Twitter in the Political Campaign: Searching for Intermedia Agenda-Setting Effects in the Presidential Primary.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20 (4): 363–380.

- Cushion, Stephen, Allaina Kilby, Richard Thomas, Marina Morani, and Richard Sambrook. 2018. “Newspapers, Impartiality and Television News.” Journalism Studies 19 (2): 162–181.

- Eddy, Melissa. 2016. “Refugee’s Arrest Turns a Crime Into National News (and Debate) in Germany.” The New York Times, December 9, 2016, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/09/world/europe/refugees-arrest-turns-a-crime-into-national-news-and-debate-in-germany.html.

- Entman, Robert M. 2003. “Cascading Activation: Contesting the White House’s Frame after 9/11.” Political Communication 20 (4): 415–432.

- Entman, Robert M., and Nikki Usher. 2018. “Framing in a Fractured Democracy: Impacts of Digital Technology on Ideology, Power and Cascading Network Activation.” Journal of Communication 68 (2): 298–308.

- Forschungsgruppe Wahlen. 2020. “Forschungsgruppe Wahlen: Politbarometer.” March 27, 2020. http://www.forschungsgruppe.de/Umfragen/Politbarometer/Langzeitentwicklung_-_Themen_im_Ueberblick/Politik_II/#Probl1.

- Frank, Arno. 2016. “Getötete Studentin: Warum Die ‘Tagesschau’ Nun Doch Über Den Mord in Freiburg Berichtet.” Spiegel Online, December 6, 2016, sec. Kultur. https://www.spiegel.de/kultur/tv/getoetete-studentin-maria-l-in-freiburg-warum-die-ard-nun-doch-ueber-den-mord-berichtet-a-1124574.html.

- Gadarian, Shana Kushner, and Bethany Albertson. 2014. “Anxiety, Immigration, and the Search for Information.” Political Psychology 35 (2): 133–164.

- Georgiou, Myria, and Rafal Zaborowski. 2017. “Media Coverage of the ‘Refugee Crisis’: A Cross-European Perspective.” Council of Europe Report DG1 (2017)03. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/faad/73c547dbfdfa951085055d9690fe0acbf322.pdf.

- Gerhards, Jürgen, Silke Hans, and Jürgen Schupp. 2016. “German Public Opinion on Admitting Refugees.” Deutsches Institut Für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW) Economic Bulletin 6 (21): 243–249.

- Greussing, Esther, and Hajo G. Boomgaarden. 2017. “Shifting the Refugee Narrative? An Automated Frame Analysis of Europe’s 2015 Refugee Crisis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (11): 1749–1774.

- Guo, Lei, and Chris J. Vargo. 2017. “Global Intermedia Agenda Setting: A Big Data Analysis of International News Flow.” Journal of Communication 67 (4): 499–520.

- Hall, Allan. 2016. “Pictured: The Migrant Who ‘Raped and Murdered’ German Teen.” Mail Online, December 6, 2016. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/∼/article-4004480/index.html.

- Hanfeld, Michael. 2016. “Tagesschau Berichtet Nicht Über Ermordete Studentin in Freiburg.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, December 5, 2016. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/medien/tagesschau-berichtet-nicht-ueber-ermordete-studentin-in-freiburg-14560129.html.

- Heise, Nele, Wiebke Loosen, Julius Reimer, and Jan-Hinrik Schmidt. 2014. “Including the Audience: Comparing the Attitudes and Expectations of Journalists and Users towards Participation in German TV News.” Journalism Studies 15 (4): 411–430.

- Hobolt, Sara B. 2016. “The Brexit Vote: A Divided Nation, a Divided Continent.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (9): 1259–1277.

- Holzberg, Billy, Kristina Kolbe, and Rafal Zaborowski. 2018. “Figures of Crisis: The Delineation of (Un)Deserving Refugees in the German Media.” Sociology 52 (3): 534–550.

- Lee, Eun-Ju, and Edson C. Tandoc. Jr. 2017. “When News Meets the Audience: How Audience Feedback Online Affects News Production and Consumption.” Human Communication Research 43 (4): 436–449.

- Liebe, Ulf, Jürgen Meyerhoff, Maarten Kroesen, Caspar Chorus, and Klaus Glenk. 2018. “From Welcome Culture to Welcome Limits? Uncovering Preference Changes over Time for Sheltering Refugees in Germany.” Plos One 13 (8): e0199923.

- Livingston, Steven, and W. Lance Bennett. 2003. “Gatekeeping, Indexing, and Live-Event News: Is Technology Altering the Construction of News?” Political Communication 20 (4): 363–380.

- Loosen, Wiebke, and Jan-Hinrik Schmidt. 2012. “(Re-)Discovering the Audience.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (6): 867–887.

- Maier, Jens. 2016. “Kein Wort Zu Freiburg: So Macht’s Die ‘Tagesschau’ Den Lügenpresse-Hetzern Recht | STERN.De.” Stern, December 4, 2016. https://www.stern.de/kultur/tv/kein-wort-zu-freiburg--so-macht-s-die--tagesschau--den-luegenpresse-hetzern-recht-7224360.html.

- Marres, Noortje, and Esther Weltevrede. 2013. “Scraping the Social?” Journal of Cultural Economy 6 (3): 313–335.

- McLaren, Lauren M., Hajo Boomgaarden, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2018. “News Coverage and Public Concern about Immigration in Britain.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 30 (2): 173–193.

- Mulherin, Peter E., and Benjamin Isakhan. 2019. “State–Media Consensus on Going to War? Australian Newspapers, Political Elites, and Fighting the Islamic State.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 24 (4): 531–550.

- Neuman, W. Russell, Lauren Guggenheim, S. Mo Jang, and Soo Young Bae. 2014. “The Dynamics of Public Attention: Agenda-Setting Theory Meets Big Data.” Journal of Communication 64 (2): 193–214.

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, Craig T. Robertson, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2021. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2021-06/Digital_News_Report_2021_FINAL.pdf.

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, David A. L. Levy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2016. “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2016.” Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. http://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital-News-Report-2016.pdf.

- O’Connor, Cliodhna, and Helene Joffe. 2020. “Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19: 160940691989922.

- Peters, Chris, and Tamara Witschge. 2015. “From Grand Narratives of Democracy to Small Expectations of Participation.” Journalism Practice 9 (1): 19–34.

- Rieder, Bernhard, Rasha Abdulla, Thomas Poell, Robbert Woltering, and Liesbeth Zack. 2015. “Data Critique and Analytical Opportunities for Very Large Facebook Pages: Lessons Learned from Exploring ‘We Are All Khaled Said.” Big Data & Society 2 (2): 205395171561498.

- Rudolph, Thomas. 2021. “Populist Anger, Donald Trump, and the 2016 Election.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 31 (1): 33–26.

- Scally, Derek. 2016. “Young Woman’s Killing in Germany Stokes Row about Refugee Policy.” The Irish Times, December 5, 2016. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/europe/young-woman-s-killing-in-germany-stokes-row-about-refugee-policy-1.2893708.

- Schulz, Wolfgang, Thorsten Held, Stephan Dreyer, and Thilo Wind. 2008. “Regulation of Broadcasting and Internet Services in Germany: A Brief Overview.” 13. Arbeitspapiere Des Hans-Bredow-Instituts. Hamburg: Verlag Hans-Bredow-Institut.

- Singer, Jane B. 2014. “User-Generated Visibility: Secondary Gatekeeping in a Shared Media Space.” New Media & Society 16 (1): 55–73.

- Skogerbø, Eli, and Arne H. Krumsvik. 2015. “Newspapers, Facebook and Twitter.” Journalism Practice 9 (3): 350–366.

- Steiner, Miriam, Melanie Magin, and Birgit Stark. 2019. “Uneasy Bedfellows: Comparing the Diversity of German Public Service News on Television and on Facebook.” Digital Journalism 7 (1): 100–123.

- Tagesschau. 2016a. “Sendung: Tagesschau 05.12.2016 20:00 Uhr.” 2016. https://www.tagesschau.de/multimedia/sendung/ts-17275.html.

- Tagesschau. 2016b. “Im Fall Der Toten Freiburger Studentin Hat Die Polizei Einen 17-Jährigen Festgenommen.” December 3, 2016. https://www.facebook.com/tagesschau/posts/10154820003414407.

- Tagesschau. 2019. “#kurzerklärt: Was Berichtet Die Tagesschau - Und Was Nicht?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hUur3brG7LE.

- Tagesschau. 2021. “Tagesschau.” 2021. https://www.youtube.com/user/tagesschau.

- Vollmer, Bastian, and Serhat Karakayali. 2018. “The Volatility of the Discourse on Refugees in Germany.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1-2): 118–122.

- Wallace, Julian. 2018. “Modelling Contemporary Gatekeeping.” Digital Journalism 6 (3): 274–293.

- Welt. 2016. “20-Uhr-Nachrichten: „Tagesschau“ Ließ Freiburg-Meldung Weg.” Welt, December 4, 2016. https://www.welt.de/vermischtes/article159963535/Darum-liess-die-Tagesschau-die-Freiburg-Meldung-weg.html.

- Welt. 2018. “‘Tagesschau on Tour’ in Köthen.” December 6, 2018. https://www.welt.de/regionales/sachsen-anhalt/article185113664/Tagesschau-on-Tour-in-Koethen.html.

- Wintterlin, Florian, Tim Schatto-Eckrodt, Lena Frischlich, Svenja Boberg, and Thorsten Quandt. 2020. “How to Cope with Dark Participation: Moderation Practices in German Newsrooms.” Digital Journalism 8 (7): 904–924.

- Ziegele, Marc, Nina Springer, Pablo Jost, and Scott Wright. 2017. “Online User Comments across News and Other Content Formats: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, New Directions.” Studies in Communication and Media 6: 315–332.

- Zimmer, Michael. 2010. “But the Data is Already Public’: On the Ethics of Research in Facebook.” Ethics and Information Technology 12 (4): 313–325.