Abstract

Digital first strategies at newspapers raise complex questions of temporality and scheduling. Yet there is a lack of ethnographic accounts for web-to-print newsmaking. While research has long been concerned with time in analog newspaper production, and online news time has mostly been studied through the prism of immediacy, almost nothing is known about dual-platform workflows. What happens to temporalities when web and print production factors and logics collide? Ethnographic research at legacy Swiss daily newspaper Le Temps provides a novel insight. Using a newsmaking reconstruction approach, we conducted an in-depth case study of a single day’s news production with a view to understanding publication times and scheduling. Despite their much-publicized shift to web-to-print production, the impetus for producing stories largely remained subordinate to filling the print pages via backwards scheduling. Tools, meetings and temporal labels defined broad categories of stories that reflected temporal publication objectives and associated production requirements. Many outside forces restricted scheduling options, while publication frequency invariably accelerated late in the day. When publication times were not imposed by external forces, the logics key newsworkers applied to scheduling involved smoothing the output curve, building sequences with variation in form and content, and catering to reader habits and preferences.

Introduction

Many journalists, editors and managing editors of dual-platform web-to-print newspapers may find the following exemplum reminiscent of their own experiences of digital first publishing:

Be fast and be first. Or dig deep and produce an in-depth story, rich in perspective and context. Cater to your online audience at the risk of annoying tomorrow’s print reader with facts already widely available. Or write for tomorrow’s print reader, but risk it feeling like ‘old news’ to your online audience. Do both and sacrifice considerable resources of a newsroom already stretched to its limit and whose finances are dire.

A dive into the literature fails to provide satisfactory answers. Furthermore, despite web-to-print becoming the norm in many newsrooms, underlying workflows and production logics have scarcely been theorized, let alone documented. Almost nothing is known about how print and web shape each other in digital first newsmaking. For the many newsrooms undergoing such radical changes to their production process, or on the verge of doing so, answers to these questions may provide useful insights.Footnote1

As we sought to address this research gap, we identified the reconfiguration of news temporalities as a key feature distinguishing dual platform publishing from print- and web-only news production. Over the years, print news temporalities have been extensively studied (Schlesinger Citation1977), while online news time has tended to be examined through the prism of immediacy (Usher Citation2016), often neglecting the study of less urgent news. What is undisputed is that these temporalities fit within the respective temporal affordances, which may be summarized as follows: choosing a publication time for a print story amounts to selecting among print issues separated by 24-hour increments, while online stories may be published asynchronously, offering limitless possibilities along a temporal continuum. By contrast, digital first temporalities are complex (English Citation2011; Wheatley and O’Sullivan Citation2017) because, as the exemplum above suggests, newsworkers apply different logics to web and print. However, stories are not only subjected to opposing platform-specific logics, but—we would soon discover—one article’s publication time may be impacted by those of others.

In seeking to understand how publication times are determined for web-print stories, this research uses newsmaking reconstruction to study one digital first newspaper in general, and a single day’s production in particular. Observation, content analysis and semi-structured interviews revealed publication times to be strongly subordinate to print production factors and logics, not all of which were temporal. Stories were subjected to forces originating inside and outside the newsroom, distributed among different newsworkers and production stages. Tools, meetings, and language all contributed to shared understandings of stories’ temporal requirements. Coordinating publication times involved strategic scheduling, which included negotiating sequences, sometimes by arbitrating between conflicting interests of multiple stories, advocated for by different newsroom workers. However, much of the schedule remained beyond the control of editorial management. This was particularly the case for hotter news late in the day.

Literature Review and Key Concepts

Digital first newsmaking practices remain a blind spot within Journalism Studies. Below we explain why, despite news having been published online for decades, integrated web-to-print production systems have only recently become widespread, and why temporality is reconfigured once print and web become tethered. Finally, we concern ourselves with the literature that may help us conceptualize digital first news time, paving the way for the method.

The Erosion of the Wall between Print and Web

According to Bødker and Brügger (Citation2018, 59) most early news websites inherited print-based temporal practices from the newspapers that spawned them. Early on, content was simply repurposed for the web, often thanks to automated systems dubbed shovelware (Deuze Citation1999). In parallel, many newspapers introduced web-desks covering breaking news more reactively. In ethnographies of Clarìn and Le Parisien, Boczkowski (Citation2010) and Cabrolié (Citation2010) describe new dedicated web teams sharing little with their newspapers’ more classic print-focused newsrooms. While the latter remained rooted in print temporalities (notably studied by Schlesinger Citation1977), the former were consumed by urgency. These logics of immediacy have been well documented, as have many of their consequences (Domingo and Paterson Citation2008; Karlsson Citation2011; Usher Citation2016). Without questioning its relevance as a research topic (especially from the normative standpoint of journalism’s democratic role), this focus nevertheless fed into a speed narrative that overshadowed an important reality: beyond specialized web-desks, newspaper websites and a majority of the production systems supporting them remained stuck in a print-based news cycle (Calmon Alaves and Schmitz Weiss 2004; Lim Citation2012).

This focus on immediacy likely obscured less obvious temporal reconfigurations related to two important changes occurring in the mid-2010s: the widespread adoption of mobile devices (see for example Westlund Citation2013; Pignard-Cheynel and van Dievoet Citation2019) and the (re)emergence of paywalls (Pickard and Williams Citation2014; Franklin Citation2014).Footnote2 Overall, the adoption of mobile devices created the possibility of accessing information anytime and anywhere, further stimulating demand for news that was not only more timely, but that took into account users’ daily routines. In parallel, paywalls helped resolve the problem of online readers freely accessing content before print subscribers, which English (Citation2011, 147) has referred to as the “print-web dilemma.” As they noted, “the decision over which platform to use first has become a major—and increasingly complex—issue for media outlets as they weigh up delivering immediate news online for free, while allowing the information to be available to readers and rival publications.” According to Sjøvaag (Citation2016, 306), the paywall “changes the way editors construct online editions, as it introduces new approaches to traditional conceptions of deadlines.” This double shift has allowed for ambitious subscription-based commercial strategies that seek to make better use of web potentialities and to conceive more fluid digital publication schedules.

Digital First: A Fuzzy Definition. Multiple Temporal Shifts

Although ubiquitous in news industry discourse, digital first lacks a single stable definition and its use can result in confusion within the newsroom (Hendrickx and Picone Citation2020). As for the literature, it has mostly sidestepped defining it, as illustrated by Dwyer’s (Citation2015) choice to use digital first more as a “rhetorical departure point” than as a “consensually embraced strategy.” Describing work at Die Welt, García-Avilés et al. (Citation2017, 454) provide the following account:

In December 2013, around 120 journalists moved into a large central newsroom geared to digital production. The motto 'online first' gave way to the 'digital to print' strategy: The journalists work for digital publishing first, and then produce daily papers out of what they had initially produced for digital channels.

Short of providing a stable definition of digital first, research has nevertheless been dedicated to documenting the changes it entails, including to temporalities. In their study of six European newsrooms, Menke et al. (Citation2018, 895) find that “profoundly rooted aspects, such as channel priorities and time allocation, tend to follow the dominant print culture.” Upon analysing four Irish newspapers, Wheatley and O’Sullivan (Citation2017) found that non-original content tended to be published during the daytime, while original in-house stories tended to appear online subsequent to their availability in print form.

Schlesinger and Doyle (Citation2015) study of the digital first strategies of The Telegraph and The Financial Times offers glimpses of the temporal challenges of web-to-print. The latter changed “from a 1-day print cycle to having journalists write more frequently ‘to keep the site dynamic’” (8). Work schedules and shift patterns also changed. Although weighed against other factors, data-driven knowledge of users’ habits was found to inform publication choices. At The Telegraph, stories generally went online first. However, the authors note that “the traditional routines and values associated with print production continue to exert a strong sway, as is evident from a mismatch at FT.com and other titles between recognized peak periods in online news readership and hourly patterns in online publication of stories by journalists” (18).

Concepts and Lay Terms for Digital News Temporalities

Research has yet to develop a specific framework for the temporalities of digital journalism. Perhaps tellingly, newsroom language has not settled on temporal labels that specifically apply to online news. The dreaded deadline remains widespread, including when referring to online stories. Franklin and Canter (Citation2019, 312) define the deadline as:

The latest time of day or night […] or the latest date, by which a news story or feature must be received by the newsdesk (or by sub-editors or the newsreader) if it is to be included in the next edition of a newspaper, magazine or the next broadcast bulletin.

Instead, we may borrow from the literature on the organization of time, and in particular Zerubavel’s (Citation1976) concept of scheduling, defined as the dynamic aspect of the negotiation of timetables. Parameters may include duration, sequence, timing, tempo and their linear or cyclical nature. Furthermore, three components are built into schedules: “a totally self-determined part, a totally environmentally determined part, and a socially negotiable part in-between” (Zerubavel Citation1976, 91). Ananny (Citation2016, 419) observes that “Many of the tensions of news time are about synchronizing inside-out and outside-in forces—making sure that sources, beats, journalists, advertisers, and audiences all share rhythms.” The value of thinking in terms of scheduling should be made clear: newsroom time management can be examined through the prism of an ongoing activity within which the different internal and external temporal forces of stories are constantly (re)negotiated.

By external, we mean located beyond the boundaries of the newsroom, whether upstream from production (e.g., sources), or downstream (e.g., audiences). A force should be understood as a contributory cause of a certain course of action. For practical purposes, we will divide forces into factors and logics in the ethnographic account below. Factors shall describe a more rigid or definitive effect whereas logics are mediated by newsworkers, according to explicit or implicit rules, or rationales evaluating the best course of action in view of a desired outcome.Footnote3 An example of a print production factor would be the maximum length of a story, defined by the print page’s template, or the last deadline set by the printer for receiving the print-ready page files. An example of a print logic would be ensuring that two interviews not be printed on the same double page. The distinction is empirical rather than absolute: a newspaper could hire more proofreaders or negotiate a later deadline, but this would require significantly more effort than printing a page with two interviews, however tedious to the end reader.

We suggest that newsrooms seem not to have developed temporal labels that relate to web publishing temporalities. As we will see, terminology used at Le Temps to frame stories within temporality belong to widespread newsroom language inherited from the print era. They fit Tuchman’s (Citation1973) concept of typification, defined as a “classification in which the relevant characteristics are central to the solution of practical tasks or problems at hand and are constituted in and grounded in everyday activity” (116). In her study, Tuchman showed how labels such as soft and hard have predictability and urgency of dissemination built into their meanings and are used for scheduling. The concept of typification carries theoretical implications: although the labels used may be common to a wider journalistic culture, they are associated with practical tasks and activities rooted within each newsroom. Accordingly, labels implicitly containing temporal reference were studied alongside the work being performed on the stories they describe. Rooted in practice, these typifications also helped define the temporal categories in the analysis below and played a key role in sampling.

Method: A Reconstruction of a Single Day’s Newswork

The present paper belongs to a broader ethnographic research project questioning the interconnectedness of print and digital news production in digital first publishing systems. At its core, it uses newsmaking reconstruction (Reich and Barnoy Citation2020), which considers specific features of news production (that which must be explained), as well as the ways in which these features came to be (the explanation). The explanation takes into account sources, technologies, as well as “more abstract and hidden practices such as the judgements and evaluations made on the way to publications” (Reich and Barnoy Citation2020, 967).

We used classic newsroom observation as a starting point. Having identified temporality as a key aspect of digital first news production, we then sought to identify temporal production factors and logics by (re)tracing the forces that (mutually) shape web and print production. This led us to study work as it occurred, as well as documents, tools, discourse and the news stories themselves, revealing a broad set of heterogeneous forces. While the differences to be explained of course included textual ones within news stories themselves, these were both rare and mostly easy to explain. Online publication times on the other hand (which we locate at the level of the meta-text), became a key concern, since they are necessarily different, and subject to multiple complex forces.

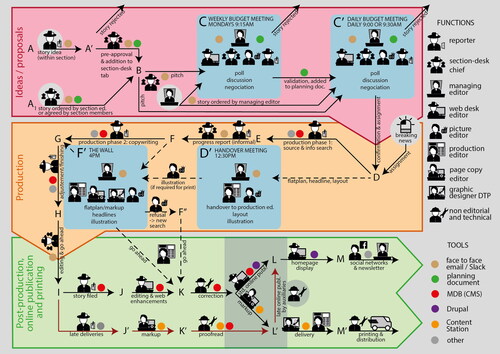

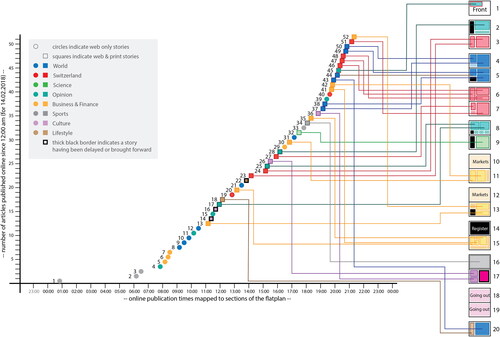

If certain types of factors and logics were confined within particular production stages, others were story specific. This led to the creation, from research notes and newsroom documents, of a detailed workflow diagram () allowing us to locate print/web differentiation, or unresolved tensions. Different types of stories revealed specific sets of forces. While some factors were non-human, including several inherent to the production system itself, others were rooted in practice. Again, of interest were not a particular newsworker’s idiosyncrasies, but for any given story the successive actions applied to each (type of) story as it moved down the production line.

Sampling was purposefully unorthodox: early observation had identified cases where platform-specific logics were applied differently according to topic/section. Furthermore, different articles from the same issue interfered with one another and could therefore not be studied in isolation. This was the starting point for an in-depth case study of a single (random) day’s news production. This heuristic was decisive: only once the data for a single day’s production was collected would we be able to study the relationships between temporal forces of multiple stories. Method shifted our focus beyond singular deadlines to scheduling.

The stories included in this case study include those published online on 14 February 2018 (n = 51), as well as all those appearing in the print issue of 15 February (39). Among these, there is an important overlap (30). The data for the specific edition includes the observation of work being carried out during the entire week between 12 and 18 February. All key editorial meetings were observed, recorded, transcribed and coded. Beyond meetings, we sought to “follow the footsteps” of articles as they came into being. For practical reasons, we selected three stories for further investigation that best reflected the temporal variation of a day’s work according to previously identified variables: their belonging to the commonly used typifications (breaking, cold and hot news), their production by different section-desks, and their online publication times. Shadowing these three stories amounted to choosing the best possible vantage point (Czarniawska-Joerges Citation2007, 91; Meunier and Vasquez Citation2008). Much data was collected subsequently, for example from change logs within the publishing system, which kept track of the parallel changes made to the web and print versions. Subsequent data collection involved working according to the empirical principle “follow the actors […] and the traces left behind by their activity” (Latour Citation2005, 29).

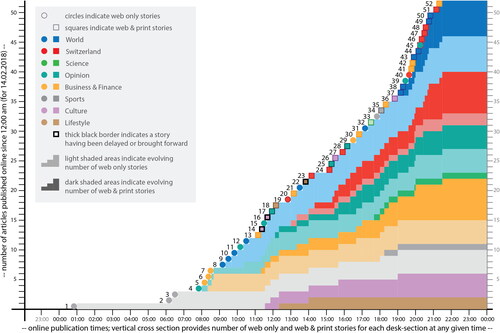

Wherever temporality was visible or discussed, we searched upstream. From this original data, as well as graphics of publication times (), we assembled temporal accounts for our chosen day’s newswork, complemented with semi-structured interviews. For the three chosen stories, interviews were conducted with eleven newsworkers involved in their production editing and publication.Footnote4 This final stage of our newsmaking reconstruction method sought to confirm previously identified factors and logics through triangulation (Cottle Citation2007), as well as identify new ones not visible in available data. Interviews used previously collected material for elicitationFootnote5, helping newsworkers provide accounts of general practices and specifically applied logics.

During interviews, newsworkers described their workday, as well as the specific actions and choices that were made during their work on the abovementioned stories. Reich and Barnoy (Citation2020, 974) note that specific story reconstructions provide “the contextual richness of particular stories presented to them, anchored in particular real-life circumstances, constraints, decisions, actions and thoughts.” Accounts shifted between generic routines, and specific actions pertaining to the day of 14 February and—at times—others. The two editors-in-chief were asked to comment and explain if and how the edition reflected editorial strategy or revealed unresolved production problems. Data was then reassembled on two levels. First, all information pertaining to each given story was combined to create accounts of how it came into being. Second, factors and logics were sorted by type and analysed.

The question of temporality guided our newsmaking reconstruction throughout, which we will explore in the results sections according to the following reframed research questions:

“What is the hierarchy of forces imposing themselves on these schedules (environmentally determined parts of scheduling)?”

“When scheduling options remain once these forces have been accounted for, what scheduling logics are applied (negotiated and self-determined parts)?”

Answers will come in two parts. First, we will provide an account of a day’s work at Le Temps and the temporal patterns it creates. Although some elements of explanation will become explicit, this descriptive account provides that which must be explained. Second, we identify those forces that structure the temporalities of news stories and seek to identify order and hierarchy. This second level of analysis provides the bulk of the explanation and, accordingly, of the answers to the above questions.

Results I: Print Hegemony and Evening Bottlenecks (An Ethnographic Thick Description of a Day’s Work at Le Temps)

The French-language Swiss daily newspaper Le Temps was born in 1998 from the merger between two historic daily newspapers. At the time of our fieldwork, it was owned by Ringier,Footnote6 one of the country’s two major publishers and had a circulation of 33,000 from a linguistic catchment area of two million. It defined itself as business friendly, economically liberal, and culturally and socially progressive. Typical readership was college educated and spanned the full political spectrum. Occasionally sensitive to breaking news, it privileged in-depth coverage, analysis and debate.

Although generalizing from ethnographic case studies is necessarily problematic, there are strong arguments in favour of looking into temporalities at Le Temps. When our fieldwork began in 2017, it was the only legacy newspaper to have switched to a fully integrated web-to-print system within the Swiss media landscape. As such, it offered an opportunity to observe a publishing system similar to those being adopted elsewhere in Switzerland and beyond, but that had become routine in this newsroom.Footnote7

The Production System and Its Workflows

In the autumn of 2015, Le Temps switched to a digital first production and publishing strategy underpinned by a new responsive mobile-friendly website. Journalists began writing their stories directly into the content management system (CMS), from which those destined for the newspaper were exported to print publishing tools, adjusted and placed into their respective pages. Access to the website was managed via a cookie-based metered paywall, allowing non-subscribers to read seven free articles per month, beyond which a subscription was required. Editorial management told staff stories should be made available in digital form prior to their availability in print. This was no longer be considered detrimental to (print) subscribers, since content was paywall protected and all subscriptions now included online access. Digital could and would come first.

Our observation began in late 2017, a little less than two years after the switch to digital first. The web-desk consisted of three full-time editors from a total editorial staff of about 70. Web-editors worked overlapping shifts from 7:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. and from 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. respectively. One was responsible for editing stories to web standards and placing them online, and a second for managing and updating the website’s homepage and looking for relevant newswire stories. On the rare occasions all three were available, the third concentrated on producing web-only stories.

Stories produced by Le Temps for dual print-web publication followed production stages common to most news outlets: the idea; the required proposal, argumentation (pitch) and validation in collective spaces (budget meetings); the search for facts, information and comment (gathering); the creative process (writing); editing, proofreading; final validation; publication. The workflow of the production diagram of reproduces, from research notes, the trajectories followed by stories.

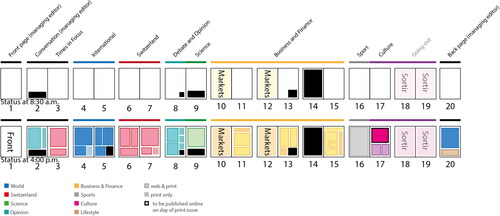

Budget Meetings and Scheduling

On 14 February at 9:00 a.m. the daily budget meeting began. Chaired by the managing editor, it unfolded similarly to most other days. The web production manager gave an update on the website (relevant breaking news and stories over- or underperforming). Section-desk chiefs then presented proposals of those stories set to appear in their respective pages of the following day’s print issue, and those to be published online until the following day. With a very high level of overlap, most would belong to both (24 of the 37 discussed). Section-desk chiefs usually present a list of stories by means of what we shall call reverse engineering.Footnote8 According to the space available within the pages allotted to them by the flatplan, which undergoes minor daily adjustments (), they evaluate the preferred number of stories, and define approximate target-lengths. This evaluation involves finding a suitable match between the available templates and their reporters’ story proposals, previously fished for informally or in separate section-desk meetings.

The print production manager is mainly concerned with spatial variables (length and number of items) and the web production manager with publication times. During meetings, the latter frequently urges for delivery times to be brought forward. “Could we have this one earlyish?” they asked the culture section-desk chief during the 14 February meeting regarding a story about a world-famous violinist [ and , story 26]. Pre-empting a similar request, the business and finance section-desk chief says of a Q&A interview with the CEO of a major Swiss company [story 30]: “Their PR team are always a bit complicated when it comes to approving quotations. I say this for [web production manager] who’s about to ask me when the interview will be ready.” A member of the web-desk inscribes confirmed stories into the “daily planning” tab of the editorial planning documentFootnote9, a multi-tab spreadsheet accessible to the entire newsroom. This “daily planning” table is not comprehensive. Stories breaking later in the day are rarely added, while those scrapped and replaced by others are often also unaccounted for. Although approximate times are indicated for some stories, no strict sequencing is inscribed here.

Figure 4. Online publication chronology, mapped to budget meeting and print flatplan, 14 February 2018.

There is also a weekly budget meeting held on Monday mornings, during which section-desk chiefs announce important events, significant planned stories, while the managing editor discusses the upcoming week’s Times in FocusFootnote10 stories. These are usually noted in one of the other tabs of the planning document before being added to the “daily planning” tab on its intended day of publication, often being scheduled at a time when feature stories achieve high audiences, and/or at times of low publication frequencies. One such story concerned the Jamaican Olympic bobsleigh team [34]. Having gathered his material from a press conference and written a first draft some days earlier, the reporter had inscribed his 10,000-character feature piece into the “sports” tab for publication on the day of the beginning of the Olympic bobsleigh event (15 February). During the 14 February daily budget meeting, the section-desk chief and web production manager agreed on a lunchtime publication time. However, with multiple references to the movie Cool Runnings, the video editor suggested making a video combining cuts from the 1993 blockbuster and press conference and training footage. They informed their colleagues that the video would not be ready before mid-afternoon. Those attending the budget meeting agreed that the benefits of offering an interactive online experience outweighed those of achieving the perfect publishing time. The web production manager inscribed a 6:30 p.m. publishing time in the “daily planning tab.”

The respective editorial planning documents and budget meetings help order stories according to their temporal specificities. Although timing may be discussed, the mere inclusion in a tab, or mention during a meeting already contributes to categorizing, while newsroom language includes labels that are implicitly associated with these documents. The stories inscribed in the long-term planning tabs of the editorial planning document are usually discussed in the weekly budget meeting and are referred to as magazine stories or cold news. Unless told otherwise, newsroom workers will assume the story need not be published within the next couple of days (but likely before the next weekly budget meeting). Stories discussed only during a daily budget meeting will have an ephemeral presence in the “daily planning” tab. Tacitly, everyone will understand that the story should be published in the upcoming print issue, while its online publication time is up for negotiation with the web production manager. Labels such as hot and hard news refer to such stories. Stories which break and are published within a single working day fall between budget meetings and are unlikely to be written into the planning document. Referred to as breaking news, these typically disrupt the workflow, interrupting work on less urgent stories.

Going Online

Online publication frequency is uneven over the course of the day. The irregular output, whether in terms of frequency or content-type, was both accounted for by the scheduling strategy and, according to newsroom staff, unsatisfactorily addressed by it. Charting the online publication times for 14 February according to the newspaper’s sections over the course of the day reveals periods with distinct patterns.

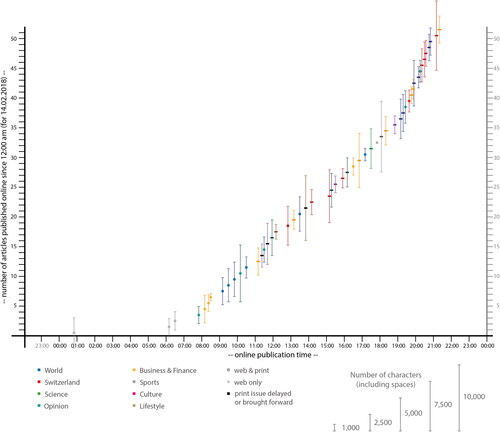

The morning was synonymous with scarcity, especially in terms of original content. and show that web-only sports [stories 1–3], business [5–7] and international [8–10, 12] stories dominated early on. These were mostly short breaking newswire reports placed online by web editors (for story lengths, see ), not printed in the following day’s paper. Newswire stories reporting overnight events in different time zones provided an overview of the latest international news and are typical of early to mid-mornings. Other contingent factors further explain some of the day’s oddities. The ongoing Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang and the announcements of several firms’ annual results explain the prevalence of morning sports and business stories. Notwithstanding newswire content, the earliest published story written in-house is generally the press review. A web-only story, on 14 February it provided a colourful Valentine’s Day press review [11].

The lunchtime period saw the publication of softer feature stories, actively promoted on the homepage. Two articles previewing the day’s cinema releases [14, 16] were placed online between 11:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m. as scheduled. These were joined by the daily recommendation (a review of a shop, a café or a restaurant) [18] as well as two opinion pieces [15, 17]. The early afternoon saw the usual slowdown in publication frequency, as the web-editors successively took lunch breaks. Heavy web-editing on the Times in Focus stories also slowed output [23, 24].

Mid-afternoon, much of the day’s harder news began to arrive at a pace the web editors could still cope with. Initially alternating topics, it came to be dominated by the day’s Swiss stories, followed by the international stories. Publication frequency increased markedly between mid-afternoon and the 9:00 p.m. print deadline. Throughout the day, members of the newsroom keep an eye on hot and breaking news in their newswire feeds. Mostly published online only (e.g., story 31), these occasionally dislodge or reconfigure stories in the print edition. A sudden breakthrough in a long-running child-abduction investigation illustrates how breaking news challenges workflows. The body of “Maëlys,” a child having disappeared seven months earlier, was found off a remote road in a French national park. Alerted by a web-editor who had spotted a newswire report, the managing editor decided to wait for further facts and comment. They ordered a web-print story from a correspondent, with a view of including details from a 6:00 p.m. press conference. It would arrive just in time for print deadline [44].

As the afternoon progressed, the stories going online began to change. Shorter, lesser stories became rarer (), as did colder feature stories. The Jamaican bobsleigh story [34] was placed online as scheduled, marking the inflection point for harder news and increased publication frequency. As per usual, headlines became closer or identical to the ones that will appear in the following day’s print issue. Hyperlinks, additional pictures and embedded web-content were reduced to a minimum. Two factors explain this shift, which occurs daily. First, as print deadline approaches, the frequency of incoming stories accelerates. Page copy editors place these into the layout. They enquire about undelivered stories, adjusting pages to expected lengths. They begin firing off reminders for those overdue. Web-editors have less editing time per story, and invariably a backlog of filed stories emerges. Second, just after 6:00 p.m. the last web-editor left the office. As usual, an auxiliary—a student without journalistic training—took over publication duties, placing all remaining stories online, except for those marked for delayed publication. Instead of the standard workflow of articles being formatted to web standards, then adjusted to print requirements by stripping them of web-only features, the workflow reverses (see arrows J’, K’ & L’ in ). Stories arriving very close to print deadline are immediately placed into awaiting pages via the desktop publishing tool. Proofreading occurs within the print page layout instead of the CMS. The auxiliary identifies unpublished stories in makeup and duplicates them for the web. We are now, in effect, operating according to a print-to-web workflow. , which maps article publication times with their location in the newspaper flatplan, is highly revealing of the many stories placed online by the auxiliary in the hours leading up to- and just after print deadline. Upon her leaving the office, all in-house stories from the following day’s issue were online, except for one culture story on page 17 (see ). All newswire reports of less than 1,500 characters are print only (see chequered areas, ). The following morning, as per usual, the web-desk editor spent some downtime making minor changes to the stories placed online by the auxiliary: adjustments to headlines and added context for three leads. One subheading was added, another was modified. Additional paragraph breaks distil the text for improved mobile readability.

Late in the day we find ourselves at the heart of the tension between digital scheduling strategies and production realities of print factors and web logics. Although we may seem to have artificially grouped “print” with “factors” and “web” with “logics,” this distinction reflects newsroom discourse and reveals the difference in resistance or durability of the two platforms. Similarly, online publication times are seldom referred to using the term deadline, with words such as “planned” or “scheduled” being more ubiquitous.

Results II: Hierarchy of Production Related Scheduling Forces

The above account offers a unique insight into how online publication scheduling occurs at Le Temps newspaper: which stories were published at what times, and their resulting temporal patterns. It identifies critical moments in the day, key temporal forces and their agents, locating these in relation to the production process. The following section further addresses the question of the hierarchy of forces imposing themselves on temporalities and, when scheduling options exist, how they are implemented. In doing so, it explores the strategic logics involved in online scheduling, and questions their operational limits.

Platform Neutral Production and Publishing Constraints

We observed how a wide range of forces constrain publishing possibilities, whether in determining the date or publication time. Most aspects of the human activity reported in the news escape the control of newsworkers, who can only account for them. Reduced newsworthy activity occurs during night-time. On the other hand, news peaks during the middle of the day, resulting in evening surges that frustrated editorial management, although they also accepted that only so much may be done about it. Commenting on publication times of 14 February, one of the editors in chief said:

There’s lots of stuff late in the evening, and I get the impression we are struggling to respect the scheduled publication times.

As usual, this is an online paper where not much happens in the morning, and then there is a lot going on at 3:00 p.m. and late in the day. We are still in a phase where we are not that good at bringing the website to life throughout the day with stories that would arrive regularly. You can see that in reality we are still very much leaning towards a print newspaper production.

When explaining the convergence of publication times towards the late afternoon and evening, the web production manager pointed to external factors:

You can’t really take it out on the reporters for this, as the day is what it is. […] It just occurs naturally. The day is rhythmed the way it is, you hand in your story in the evening. And then there’s the fact that news is news and things evolve and change. […] So, it’s just a fact that some things are easier than others to schedule. Obviously, science and culture, if there is no embargo, are easy. It gets tougher for Swiss and international news. Because the news is from the same day and will naturally be ready late in the day.

Print Production Enacts Daily Online Schedules

The spatial and temporal socio-technical networks of print production framed daily output (number and types of stories), which had important time-related consequences. A web copy editor described the powerful structuring effect of the daily print news-cycle:

The thing is that we pretty much have the exact resources to produce this newspaper [*points to newspaper in front of him*] on any given day. So, from the morning you are already focusing on your pages.

Of course, there are specific web contents such as long-reads that are planned ahead. But most of our stories and most of our days are defined by the contents of the following day’s print issue. […] So, web-first is a publication order logic rather than a production logic. We are not an online newspaper. We are a print newspaper which publishes online first.

Coordinating Publication Temporalities, and Evasive Tactics

Temporal properties of stories also translated into specific newsroom language, which immediately provided newsroom workers with shared understandings of production requirements, including temporal ones. This language allows for coordination and scheduling once production has been subjected to the most rigid temporal forces, outlined above.

Breaking, hot and cold and magazine meet the definitions of typifications as defined by Tuchman: they describe not the topic of a story, but rather temporalities in concrete production terms. Although they share certain similarities with the ones proposed by Tuchman (Citation1973), they reflect the affordances of hybrid print-digital news production and consumption. Interestingly, discussing the contemporary relevance of her typifications four decades later, she admitted that her original research had overlooked the ever-evolving nature production systems (Tuchman Citation2016). Changing technology may create new labels, or merely modify which production realities are associated with given labels. In our observation, we found that breaking, hot, cold reflected their presence or absence from meetings and the temporalities built into the tabs of the planning document. Other terms were loaded with temporal meanings and translated into production/publication realities. Hard news and magazine stories respectively aligned with hot and cold news.

The inscription of a story into the different tabs of the editorial planning document was performative: it enacted schedules, with implications for newsworkers. Discussing a story in the daily or weekly budget meetings was similarly performative: stories that went unmentioned in budget meetings and were absent from the planning document became less likely to achieve the ideal publication times and/or scheduling objectives set out for them. On several occasions we observed reporters or section-desk chiefs keeping a given story “off the radar.” One editor in chief suspected, as we had, that newsworkers developed tactics for maintaining independence from the web production manager’s schedule to regain control over a story’s publication time, or to pre-empt an undesired early delivery time.

From Ideal Publishing Times to Integrated Sequences

Each story appeared to inherit an “ideal” online publication time, determined according to specific logics. The reporter, and/or their section-desk chief would often lobby to enact these. On the other hand, we identified strategic logics applied by the web production manager for the scheduling of online publication times, some of which contradicted “story-level” ones. Although the reporter and the web production manager both advocated for audience-based online publication times, the latter weighed this against what we could call macro-logics, which aim for a smooth tempo and sequences that display contrast: stories should be published regularly and vary in terms of topics and formats (hard and soft; short and long; fact, analysis, opinion; bulletin, interview, reportage). With hotter Swiss and international stories often arriving late in the day, compromises become inevitable: either sacrifice contrast, or delay time-sensitive stories, thereby surrendering some degree of newness. Also, the web production manager made informed decisions according to data, which sometimes contradicted the conventional audience logics advocated by reporters and section-desk chiefs. Referring to an interview with a local government minister following a major announcement about a new strategy for tourism [51], they said:

You see this big interview of the politician here? I think unlike six months ago, today our reflex would typically be to withhold it and put it online at a time more suited for this type of content, let’s say at 8:00 a.m. the following morning.

Conclusion

The study of online scheduling at Le Temps unsurprisingly revealed a high degree of dependence on one external force in particular: the more or less predictable and (ir)regular occurrences of newsworthy events. These platform independent constraints originate outside the newsroom and obey multiple different temporalities, while translating into distinct production factors. Given the overlap of print and online stories, the print edition’s news cycle acts as a primary structuring force for online publishing. To a degree, this is consistent with findings by Menke et al. (Citation2018) and Schlesinger and Doyle (Citation2015). However, we believe that attribution of causality to a “print culture” may result in calls for a “web mindset,” neglecting the important fact that newsroom culture is embedded within the underlying production system. We found that print production enacts daily schedules. Beyond making schedules cyclical rather than linear, it also determines the number of print-web items to be scheduled. The switch from a bulk shovelware system for placing print content online to a digital first production system has not avoided an evening convergence of stories. Consistent with Wheatley and O’Sullivan (Citation2017), a large proportion of in-house stories went online late in the day. However, we do not believe print deadline to be solely responsible for this. Print logics, we believe, can only explain so much.

What if the idea of the print deadline causing a convergence of stories towards the end of the day was wrong? What if this convergence explained the evening deadline as much as it could be explained by it? At the very least, these questions merit further investigation.

In any case, the lack of print-web stories being published in the morning is highly revealing. Different stories constrain online publication possibilities to varying degrees. This is reflected in the distinct tools, meetings and language involved in coordinating work according to publication temporalities. Only once this full range of environmentally determined parts has been accounted for, may online scheduling be determined or negotiated. This involves weighing ideal publishing times against the logics the web production manager’s logics for building integrated sequences. Put differently, stories interfere with their respective publishing times. Journalists occasionally respond to scheduling that goes against their desired publishing times with evasive tactics. Although digital distribution facilitates rapid dissemination, gaining control over scheduling requires articles instilled with temporal flexibility. This may be found in stories that are exclusive and “outgoing” rather than “incoming” (Grevisse Citation2014); proactive rather than reactive. It is worth reaffirming that immediacy need not rule supreme when it comes to online news.

Beyond this case study, our research suggests that gaining a strong degree of control over scheduling times may be illusory, or simply just not worth it. Perceived failures to implement ambitious digital first strategies that misevaluate the full implications of the underlying production system may also create tension among newsroom workers, and with editorial management. It is revealing that since the fieldwork took place, Le Temps has begun to delay more (hotter) news until the following morning to reduce bottlenecks and avoid an overload of content coming online in the evening. Such adjustments reflect a certain temporal reflexivity, which Orlikowski and Yates (Citation2002) define as “being aware of the human potential for reinforcing and altering temporal structures.” Promoting temporal awareness within newsrooms may better equip them in view of aligning the scheduling of publication times with audience expectations and strategic considerations.

The limits of this research should be clear. Such a case study is by no means representative of the newspaper industry as a whole. It does however provide a rare account of a digital first publishing system, while shedding light on some of the tensions occurring between print and web. Using similar data collection methods, future research conducted on newspapers more concerned with breaking news may help achieve some degree of generalization. Questioning the effects of the dissolution of a single hard deadline on journalists’ work and on temporalities at the narrative/textual level would also constitute a promising line of inquiry.

Notes

1 While many large news media in northern and western Europe may have made the switch some years ago, many smaller ones elsewhere, comparable in scale to the one studied here, are yet fully implement a digital first production system. That this transition is taking this long may surprise certain readers. Indeed, the French language newspapers of Switzerland’s largest news publisher Tamedia only completed their transition to a fully integrated digital first publishing system in 2020!

2 Although these occurred at different speeds from one market to another and from one media outlet to another, the rapid adoption of smartphones following the release of the iPhone in 2007 may be seen as the starting point for mobile news (Westlund Citation2013), while 2013 has been referred to as “The year of the paywall” (Sjøvaag Citation2016).

3 Short of mobilizing a theoretical framework that defines practices in relation to (institutional) logics, while also accounting for non-human forces, we would direct interested readers to theory at the intersection of action theory and material semiotics, such as Lindberg (Citation2014).

4 Two reporters and one of the section-desk chiefs, the web production manager and one of his web-desk editors, the print-production manager and one of his print production editors, the on-duty managing editor, a second managing editor and the two editors in chief.

5 This included copies of the articles in question, hourly screen captures of the homepage, successive versions of the editorial planning document, tables indicating online stories’ publishing times, the day’s flatplan as well as other digital and physical documents provided during or immediately after observation.

6 In November 2020 Le Temps was acquired by Aventinus, a Geneva based non-profit foundation.

7 Willemin (Citation2018, 128–29) cites Le Temps as an “emblematic” example of a digital first model. The following French-language Swiss daily newspapers have since made the leap from print-to-web to web-first workflow or are currently engaged in the process of doing so (publishers in parenthesis): Le Nouvelliste (ESH), La Côte (ESH), Arcinfo (ESH), 24heures (Tamedia), Tribune de Genève (Tamedia).

8 In order to distinguish normal newsroom routines (observed between September 2017 and March 2018) and specific occurrences on 14 February 2018, we use the present tense for the former, and the past for the latter.

9 The main reference and most used document within the newsroom; the first tab, the ‘daily planning’ contains only those stories set to be produced on any given day.

10 A single or double page in each issue dedicated to a specific story or topic, usually planned a little over a week in advance.

References

- Ananny, Mike. 2016. “Networked News Time: How Slow—Or Fast—Do Publics Need News to Be?” Digital Journalism 4 (4): 414–431.

- Boczkowski, Pablo J. 2010. News at Work: Imitation in an Age of Information Abundance. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Bødker, Henrik, and Niels Brügger. 2018. “The Shifting Temporalities of Online News: The Guardian’s Website from 1996 to 2015.” Journalism 19 (1): 56–74.

- Bødker, Henrik. 2017. “The Time(s) of News Websites.” In The Routledge Companion to Digital Journalism Studies, edited by Bob Franklin and Scott A. Eldridge, 55–63. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Cabrolié, Stéphane. 2010. “Les Journalistes du Parisien.fr et le Dispositif Technique de Production de L’information.” Réseaux 160–161 (2): 79–100.

- Calmon Alaves, Rosental, and Amy Schmitz Weiss. 2004. ‘Many Newspaper Sites Still Cling to Once-a-Day Publish Cycle’. Online Journalism Review (blog). http://ojr.org/ojr/workplace/1090395903.php.

- Cottle, Simon. 2007. “Ethnography and News Production: New(s) Developments in the Field.” Sociology Compass 1 (1): 1–16.

- Czarniawska-Joerges, Barbara. 2007. Shadowing and Other Techniques for Doing Fieldwork in Modern Societies. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Deuze, Mark. 1999. “Journalism and the Web: An Analysis of Skills and Standards in an Online Environment.” International Communication Gazette 61 (5): 373–390.

- Domingo, David, and Chris Paterson. 2008. “When Immediacy Rules: Online Journalism Models in Four Catalan Online Newsrooms.” In Making Online News: The Ethnography of New Media Production, 113–126. New York: Peter Lang.

- Dwyer, Tim. 2015. “Surviving the Transition to “Digital First”: News Apps in Asian Mobile Internets.” Journal of Media Business Studies 12 (1): 29–48.

- English, Peter. 2011. “Online versus Print: A Comparative Analysis of Web-First Sports Coverage in Australia and the United Kingdom.” Media International Australia 140 (1): 147–156.

- Franklin, Bob, and Lily Canter. 2019. Digital Journalism Studies: The Key Concepts. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Franklin, Bob. 2014. “The Future of Journalism: In an Age of Digital Media and Economic Uncertainty.” Digital Journalism 2 (3): 254–272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.930253.

- García-Avilés, José A., Klaus Meier, Andy Kaltenbrunner, and Hilde Van den Bulck. 2017. “Converged Media Content: Reshaping the “Legacy” of Legacy Media in the Online Scenario.” In The Routledge Companion to Digital Journalism Studies, edited by Bob Franklin and Scott A. Eldridge, 449–458. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Grevisse, Benoît. 2014. Écritures Journalistiques: stratégies Rédactionnelles, Multimédia et Journalisme Narratif. Bruxelles: De Boeck Supérieur.

- Hendrickx, Jonathan, and Ike Picone. 2020. “Innovation beyond the Buzzwords: The Rocky Road Towardsa Digital First-Based Newsroom.” Journalism Studies 21 (14): 2025–2041.

- Karlsson, Michael. 2011. “The Immediacy of Online News, the Visibility of Journalistic Processes and a Restructuring of Journalistic Authority.” Journalism 12 (3): 279–295.

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Clarendon Lectures in Management Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lim, Jeongsub. 2012. “The Mythological Status of the Immediacy of the Most Important Online News: An Analysis of Top News Flows in Diverse Online Media.” Journalism Studies 13 (1): 71–89.

- Lindberg, Kajsa. 2014. “Performing Multiple Logics in Practice.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 30 (4): 485–497.

- Menke, Manuel, Susanne Kinnebrock, Sonja Kretzschmar, Ingrid Aichberger, Marcel Broersma, Roman Hummel, Susanne Kirchhoff, Dimitri Prandner, Nelson Ribeiro, and Ramón Salaverría. 2018. “Convergence Culture in European Newsrooms: Comparing Editorial Strategies for Cross-Media News Production in Six Countries.” Journalism Studies 19 (6): 881–904.

- Meunier, Dominique, and Consuelo Vasquez. 2008. “On Shadowing the Hybrid Character of Actions: A Communicational Approach.” Communication Methods and Measures 2 (3): 167–192.

- Orlikowski, Wanda J., and JoAnne Yates. 2002. “It’s about Time: Temporal Structuring in Organizations.” Organization Science 13 (6): 684–700.

- Pickard, Victor, and Alex T. Williams. 2014. “Salvation or Folly?: The Promises and Perils of Digital Paywalls.” Digital Journalism 2 (2): 195–213.

- Pignard-Cheynel, Nathalie, and Lara van Dievoet. 2019. “Journalisme Mobile: Usages Informationnels.” In Stratégies Édioriales et Pratiques Journalistiques. Bruxelles: De Boeck supérieur.

- Reich, Zvi, and Aviv Barnoy. 2020. “How News Become “News” in Increasingly Complex Ecosystems: Summarizing Almost Two Decades of Newsmaking Reconstructions.” Journalism Studies 21 (7): 966–983.

- Schlesinger, Philip, and Gillian Doyle. 2015. “From Organizational Crisis to Multi-Platform Salvation? Creative Destruction and the Recomposition of News Media.” Journalism 16 (3): 305–323.

- Schlesinger, Philip. 1977. “Newsmen and Their Time-Machine.” The British Journal of Sociology 28 (3): 336.

- Sjøvaag, Helle. 2016. “Introducing the Paywall: A Case Study of Content Changes in Three Online Newspapers.” Journalism Practice 10 (3): 304–322.

- Tuchman, Gaye. 1973. “Making News by Doing Work: Routinizing the Unexpected.” American Journal of Sociology 79 (1): 110–131.

- Tuchman, Gaye. 2016. “Réflexions à Propos de “Routinizing the Unexpected.” Temporalités (23): 120–122.

- Usher, Nikki. 2016. “The Constancy of Immediacy: From Printing Press to Digital Age.” In The Crisis of Journalism Reconsidered: Democratic Culture, Professional Codes, Digital Future, edited by Jeffrey C. Alexander, Elizabeth Butler Breese, and María Luengo, 170–189. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Westlund, Oscar. 2013. “Mobile News: A Review and Model of Journalism in an Age of Mobile Media.” Digital Journalism 1 (1): 6–26.

- Wheatley, Dawn, and John O’Sullivan. 2017. “Pressure to Publish or Saving for Print?: A Temporal Comparison of Source Material on Three Newspaper Websites.” Digital Journalism 5 (8): 965–985.

- Widholm, Andreas. 2016. “Tracing Online News in Motion: Time and Duration in the Study of Liquid Journalism.” Digital Journalism 4 (1): 24–40.

- Willemin, Nicolas. 2018. Médias Suisses, le Virage Numérique. Neuchâtel: Editions Livreo-Alphil.

- Zerubavel, Eviatar. 1976. “Timetables and Scheduling: On the Social Organization of Time.” Sociological Inquiry 46 (2): 87–94.