Abstract

The study presented in this article demonstrates journalists’ abilities to debunk mis-, dis- and malinformation in everyday work situations. It shows how journalists use core skills and competencies to verify the information and it describes why false information evades the journalistic filter and gets published. We combined semi-structured interviews with a think-aloud method in which 20 Estonian journalists were shown constructed episodes of false information and then asked to discuss them. Based on the results, we argue that journalists use traditional fact-checking skills in specific combinations, which is usually sufficient to validate the information. However, when under time pressure, journalists tend to trust their professional experience and take the risk of publishing unchecked information. This risk is even higher when the source seems to be trustworthy and the information is presented on an official social media platform or on the journalist’s personal social media page, or if the journalist lacks more in-depth knowledge about a specific topic. Video manipulation (e.g. deep fake) and decontextualised photo presentations are the most difficult for journalists to verify, and that is similar regardless of the platform the journalist specialises in. The results of this study are useful for training journalism students and practicing journalists in how to debunk false information.

Introduction

In democratic countries, the decline in credibility conditioned by the lack of transparency and false information pervading the fact-checking procedures is often associated with the decline of journalism as an institution (Curry and Stroud Citation2021; Masullo et al. Citation2021). Journalism’s ability to provide factual and reliable information is based on journalists’ epistemological activities (Ekström and Westlund Citation2019). Scattered epistemologies and diversified understandings of truth have changed journalism’s role as the fact-checked gatekeeper (Capilla Citation2021; Waisbord Citation2018). Traditional fact-based media is trusted as a source for credible information, and journalism could cater more to audiences’ demands for more fact-based and less discussion-based content (Wagner and Boczkowski Citation2019). However, preparing publishable stories under tight deadlines increases the pressure placed on the performance of skills in online journalism, including discarding the fact-checking step before publishing (Harro-Loit and Josephi Citation2020; Himma-Kadakas Citation2018). The implications of different temporalities in news production may create epistemic dissonance that jeopardizes the authority of news media (Ekström, Ramsälv, and Westlund Citation2021). Under time pressure, ready-made multimedia or data content may decoy journalists to publish it without proper fact checking (Erkmen Citation2020; Kõuts-Klemm Citation2019; Reich and Godler Citation2014; Beiler, Irmer, and Breda Citation2020). Godler and Reich (Citation2013) have shown that journalists practice questioning tactics and choices of interrogative emphases as knowledge creation activities. Similarly, Graves (Citation2017) argues that in moments of institutional unsettlement, information verification relies on factual coherence rather than straightforward correspondence. Being exposed to numerous forms of information disorder—originating from biased PR materials to pre-framed data—demands complex skill practice from journalists. Nevertheless, do these skills somehow differ from the core journalistic skills outlined and defined in several studies (e.g. Lluis Citation2006; Fahmy Citation2008; Örnebring and Mellado Citation2016)?

The probability of false information passing the journalistic fact-checking filter refers back to the problem of not being able to detect and debunk false information. Thus, the present study investigates how journalists detect and debunk different types of false information. We investigate the fact-checking skills of journalists working for different platforms at Estonian Public Broadcasting and commercial media organisations. Although this is not a comparative study, the results are significant in several countries with similar media systems. Drawing from Hallin and Mancini’s (2004) model of media systems, Estonia’s media system can be described as the Nordic democratic corporatist model. Most countries using this model also belong to the media-supportive, more consensual cluster (Humprecht, Esser, and Van Aelst Citation2020) demonstrating high resilience to online disinformation. To date, the countries in this cluster have not been affected by the effects of information disorder. Hence, it becomes more important to study journalistic fact-checking as reporters in all countries are increasingly exposed to diverse forms of information disorder in the global information flow.

First, this study identifies the skills and competencies that journalists use to verify the information concerning different information disorder forms. Second, it describes the reasons why false information pervades the journalistic filter and gets published by linking the occurrence of information disorder to journalistic skill performance. The findings are useful in training journalists to recognise information disorder in news reporting.

Literature Review

Many studies have shown how the dwindling workforce and economic pressures create the conditions that influence the quality of journalism. Time, or more precisely the lack of it, is one of the key factors that influences how the ways in which information is acquired affects journalists’ working practices (Harro-Loit and Josephi Citation2020). Time pressure in production routines is frequently created by multitasking, which online journalists are particularly faced with (Fernandes and Jorge Citation2017).

Using data are becoming a natural part of the news-making process and it is considered an essential skill in a journalist’s toolbox. However, there are also obstacles in data journalism, such as the difficulties of accessing reliable data, the lack of investments into data journalism and limited professional collaboration (Erkmen Citation2020). Journalists perceive multimodal and data-driven disinformation as more credible than textual disinformation (Hameleers Citation2022 ; Wihbey Citation2017). Kõuts-Klemm (Citation2019) notes that a lack of resources in the newsrooms also results in a lack of skills for data analysis, which, in small media markets such as Estonian and many other Central and Eastern European countries, translates into an inability to conduct (big) data analysis. Overall, time-pressure and other constraining factors in newsroom practices may result in publishing a greater volume of materials and data prepared by public relations (PR) departments (Reich and Godler Citation2014; Beiler, Irmer, and Breda Citation2020).

In the academic literature, some studies focus on the factors influencing news production process, while others address the skills and competences related to fact-checking. Several studies have tried to outline and define the core journalistic skills (Lluis Citation2006; Fahmy Citation2008; Örnebring and Mellado Citation2016). These categorisations have formed a pattern in which the fact-checking skills—the central skills in debunking false information—are classified under back-stage news reporting processes. This, in turn, means that these skills are not explicitly visible in the outcome of the news story. However, fact-checking is an essential part of news reporting that prevents the spread of false information.

The gap in the literature between news production and skill performance needs to be bridged with studies that explain the factors that lead to publishing content that contributes to information disorder: the concept that embraces mis-, mal- and disinformation in its various forms (Tandoc, Jr et al. Citation2018; Wardle and Derakhshan Citation2017). Asak and Molale (Citation2020) show examples of how mainstream news organisations have published false information and corrected it at a later point. False information may enter the news reporting process through careless back-stage processes (Himma-Kadakas Citation2017). When those stories are published, misinformation or dis-information is legitimated (Tsfati et al. Citation2020).

The probability of false information passing the journalistic fact-checking filter refers back to the problem of not being able to detect and debunk false information. This study fills the gap in the literature by discussing journalistic fact-checking skills and investigating how journalists practice those skills to debunk false information.

Conceptual Matters

The different categorisations and definitions of information disorder reflect the complexity of this concept. It encapsulates the different forms of false information employed in the study, but different terms are also used in the article for a more precise denotation. Thus, the extensive array of information disorder terms deserves more in-depth insight.

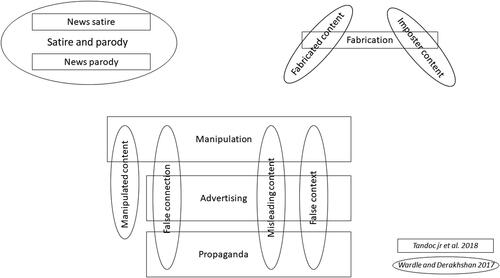

The European Union (EU) Commission (Citation2018, 10) advises using the term, disinformation, which “includes all forms of false, inaccurate, or misleading information designed, presented and promoted to intentionally cause public harm.” Although the EU report also refers to Wardle and Derakhshan (Citation2017), it does not consider their classification of information disorder. Wardle and Derakhshan (Citation2017) identify seven categories of information disorder, which overlap with Tandoc, Jr et al.’s (Citation2018) categorisation of “fake news” ().

Figure 1. Overlap in the categories of fake news discourse and information disorder presented by respectively Tandoc Jr et al. (Citation2018) and Wardle and Derakhshan (Citation2017).

Tandoc Jr et al. (Citation2018, 12) categorised “fake news” as a discourse in which the receiver has an essential role in interpreting the content. Wardle (Citation2018) and Wardle and Derakhshan (Citation2017) address the potential motivating factors for creating this type of content. However, there are significant overlaps in their substance. News that uses satire and parody is usually recognisable and can be differentiated from factually accurate content; that type of news does not usually pose a threat in terms of publishing false information. Fabricated, intentionally manipulated, imposter and misleading content are all categorised under disinformation, as their intent is to mislead (misinformation) and harm the subject and the receiver (malinformation). This sort of content is often disguised to resemble factual information and is presented as such; consequently, it has a higher probability of capturing the attention of journalists. These forms of misinformation are categorised as advertising and propaganda, which can be misleading, can be presented in a false content or can create false connections. In this study, we prefer the term, information disorder, initially introduced by Wardle and Derakhshan (Citation2017), because it covers several forms of false and misleading information that journalists need to process. We use the examples of misinformation and disinformation, and we discard the forms that contain satire and parody.

Kwanda and Lin (Citation2020) demonstrate that when “fake news” purportedly reports on factual scientific evidence, news organisations unanimously use the government statements to debunk the disinformation. The government is also treated as the authority to debunk false information. Kwanda and Lin (Citation2020) report on two significant aspects: 1) science literacy plays a significant role in fact-checking and 2) the authorities are trusted somewhat blindly, which, as Wintterlin (Citation2020) reveals, increases the risk of publishing disinformation. Some researchers have shown that emphasising fact-checking only has a positive effect when presented in combination with defending journalism (Pingree et al. Citation2018, 10). Others have indicated that increasing the transparency of news reporting is accompanied by an increase in the audience’s perception of its credibility (Curry and Stroud Citation2021; Masullo et al. Citation2021). Therefore, in addition to fact-checking, the transparency of the news increases the audience’s trust in the content and overall institutional practices.

Journalistic Fact-Checking Skills

Several attempts have been made to define core journalistic skills (Lluis Citation2006; Fahmy Citation2008; Örnebring Citation2016) since it has been a concern of both employers and educators. Örnebring and Mellado (Citation2016) and Carpenter (Citation2009) emphasise that most studies are based on the expectation of journalistic skills and competencies and they should not be transferred to skill practice. Skill practice is time- and context-related, which means that the scarcity of skills or the lack of time influences a journalist’s ability to, for example, verify the information and do fact-checking.

Journalists’ core skills are usually transferable, and journalists use them in multiple stages of news reporting. Fact-checking requires critical thinking skills while assessing the newsworthiness and origin of the material, verifying the evidence and deciding on how to truthfully report the information. Thus, the following fact-checking skills were derived from the studies on journalistic skills and competencies (Carpenter Citation2009; Örnebring and Mellado Citation2016):

Critical thinking (Carpenter Citation2009) is exercised while selecting and evaluating the sources and verifying the information. In the present study, critical thinking is also closely related to visual competence and data literacy. Critical thinking also enables journalists to comprehend more in-depth knowledge in a specific topical area.

Evaluating newsworthiness (Carpenter Citation2009). Although this may seem closely related to critical thinking, it is vital when journalists are exposed to information disorder. A significant amount of material that reaches the newsroom (e.g. reports or press releases from unauthorised shareholders) may appear newsworthy, but critical evaluation of its factual basis is required to determine whether it should be included or excluded from further processing.

Knowledge of topics outside the journalistic field (Carpenter Citation2009). Journalists often have to cover events outside their specific topical field in which they do not have an in-depth level of knowledge. While they do not have to know all the facts by heart, working with information outside the journalistic field requires comprehensive knowledge. A wider knowledge base supports journalists in recognising potentially false information. This skill can be applied to the recognition of photo manipulation due to the constantly evolving knowledge about the opportunities and dangers related to deep fake materials.

Advanced knowledge in information gathering and investigation (Carpenter Citation2009; Örnebring and Mellado Citation2016). Although these authors do not name information seeking as part of fact-checking, verifying information is an inevitable skill. It is essential to evaluate the source and find its origin, including the usage of databases and data analysis.

Knowledge of social media. Carpenter’s (Citation2009) study shows the importance of this knowledge as a viable platform for getting ideas for news. Today, social media has become an increasingly important environment for the derivation and distribution of timely information. It is essential to know how social media functions as a platform. This demands advanced information verification skills due to the amount of misinformation and disinformation spread on social media.

Misinformation that uses fake statistics, experts and evidence is more credible than misinformation without factual references (Hameleers Citation2022). This also illustrates how disinformation (intentionally created false information) becomes misinformation since journalists unintentionally distribute it. This could be avoided with fact-checking before, not after, publishing a news report (Asak and Molale Citation2020).

Neither Carpenter (Citation2009) nor Örnebring and Mellado (Citation2016) explicitly name data-literacy skills, which in their categorisations would be classified as reporting/research skills or editing skills. However, data literacy does not solely consist of the technical skill of data visualisation; journalists primarily deal with “ready-made data” provided by shareholders (e.g. statistical offices, survey data, etc.). This kind of data is already interpreted. For verification purposes, journalists must be able to assess the data’s origin and statistical accuracy.

Fact-checking skills and competencies evolve with technological development and are first adopted by fact-checkers and data activists. As Cheruiyot and Ferrer-Conill (Citation2018, 967) point out, these peripheral actors also train journalists to find the right data; they also explain statistics, give advice and provide technical tips for adapting the data into stories. Although there are a growing number of different examples of fact-checking tools and initiatives, journalists prefer convenient sources and tools to time-consuming investigative methods (Zhang and Li Citation2020, 10).

The results of these studies form the basis of Research Question 1 (RQ1).

(RQ1): What skills and competencies do journalists put into practice while performing fact-checking for different forms of information disorder?

We use fact-checking skills as a central term because it also forms the foundation for debunking information.

Factors Influencing Fact-Checking

Fact-checking is a broader term that signifies some stages of news reporting, a particular skill practice and a specific outcome of journalistic work (Himma-Kadakas Citation2018). Diverse factors influence these aspects; when combined, they function as a “cocktail” with an amplified effect. While fact-checking is usually described as part of the news-reporting process, we place it in the centre and use it to discuss these concepts and theories.

Fact-checking starts with the selection and verification of sources. Gans (Citation1979) states that sources cannot provide information to the audience until they contact a member of a news organisation. However, in practice, this approach is partly outdated. Social media and content marketing enable sources (e.g. political actors) to address audiences directly, leaving news organisations with the dilemma of either remediating this already mediated information or discarding the coverage. In this situation, decisions about publishing information are made under pressure exerted by several external factors: the relevance of the covered topic, its uniqueness and sensitivity, the availability of the sources and the reliability of the source (Shapiro et al. Citation2013; Wintterlin Citation2020). The unavailability of alternative sources and publication pressure from competitive news organisations contributes to time pressure, which, combined with the exposure to ‘easy-to-publish’ information, paves the way for publishing false information (Asak and Molale Citation2020; Himma-Kadakas Citation2017).

Time pressure deserves extra attention as it stands between selecting sources and verifying facts. Tuchman (Citation1978, 83-84) states that the verification of facts in journalism is a political and professional accomplishment, and viewing all sources as questionable is time-consuming. This implicitly refers to the embedded problem of time-dependency. Time pressure materialises in work practices as immediacy that shapes news values, the journalists’ role perceptions and newsroom routines, but it varies for print and online platforms (Usher Citation2014). For online newsrooms, immediacy promotes publish first, check facts later routines (Himma-Kadakas Citation2017). On platforms with a longer publishing cycle, the risks accompanied by immediate publishing may differ (Usher Citation2016); however, there is a gap in the literature that would show this from the perspective of fact-checking.

Another aspect that demands attention is the journalistic view on trust in sources and the endeavour for journalistic factuality. Journalistic factuality relies on the presumption that facts can be verified and information is processed according to the type of information (Tuchman Citation1978, 58) in a particular order (Gans Citation1979). However, the embeddedness of the source and the fact also creates a phenomenon that Tuchman (Citation1978, 89-91) describes as nonverifiable facts: the intermesh of source and fact that in practice means presenting a nonverifiable statement as fact. While journalists can distinguish between the source and the message’s credibility, in two-thirds of the cases, they rely on source credibility, enabling them to act on autopilot when verifying information (Barnoy and Reich Citation2022). Journalists put a high level of trust in public institutions and individuals, but this enables them to package disinformation on social media under the cover of a highly trusted source (Zhang and Li Citation2020).

While working with distant sources, reliability becomes a central issue that influences how information is considered, whether it is and cross-checked and how the journalist interacts with the source. Reliability is based on a journalist’s personal relationship with the source, which is also based on the reputation of the source, its institutional credibility, the source’s intentions and the qualities of the offered content (Wintterlin Citation2020, 141). If the information looks trustworthy, it passes the journalistic gatewatcher more quickly since it enables the journalist to economise his/her time, especially when fact-checking. This is noteworthy since intentionally distributed disinformation and malinformation is skilfully presented in a seemingly trustworthy form (Zhang and Li Citation2020).

To summarise, the factors behind fact-checking comprise the “cocktail” that, in every single case, inclines the reporter to either verify the sources and information or not verify them. This reveals the conceptual contradiction between the perceived information processing in news reporting and actual information verification routines.

Based on these findings, we formed Research Question 2 (RQ2) and Research Question 3 (RQ3):

(RQ2): What are the factors that journalists perceive to be influencing their skill performance of fact-checking?(RQ3): How does the specificity of the medium influence journalists’ perceived skill performance in fact-checking?

Methodology

This study combined semi-structured interviews with the think-aloud method. We conducted interviews with 20 reporters from online, radio and television newsrooms. We selected 11 reporters from the Estonian Public Broadcasting and nine reporters from commercial media organisations (Ekspress Meedia, Postimees Grupp and Äripäev). These four media organisations represent the majority of the Estonian news media market. The newspaper reporters were not categorised in this study for two reasons: in the converged newsroom, reporters work for both the newspaper and the digital platforms; in addition, in the newspaper, the back-stage processes, which includes fact-checking, are supported by other members of the editorial staff. The main criterion in the selection of the interviewees was that they cover the general news beat daily. Since the reporter’s gender was not relevant for achieving the research objectives, we did not include it as a variable. We excluded reporters with less than 3 years of experience to guarantee their competence to assess the organisational practices.

For exploratory qualitative interview studies, 10 to 15 interviews are sufficient (Kvale Citation1996). Since we aimed to possibly compare the types of platforms, we recruited 20 interviewees. The interviews took place between November 2019 and October 2020 via Skype, telephone and in-person meetings, and each interview lasted an average of 40 min. The interviews were audio-recorded and fully transcribed.

The interviews started with a fixed schedule of open questions concerning: 1) the usual process of putting together a news story (e.g. how reporters are exposed to news material; what fact-checking practices they use), 2) the experiences of being exposed to information disorder and 3) the reporter’s demographic and work-related background. The interview then followed the think-aloud reflection of four constructed episodes. The think-aloud method is often used for modelling the cognitive process since it registers the respondent’s reactions and reflections on a given task (van Someren et al. Citation1994). The study’s methodological challenge and its novel contribution to the field included constructing the episodes that would contain the markers of information disorder and journalistic skills needed to recognise and verify false information. The episodes were based on the types, categories and elements of information disorder outlined by Wardle (Citation2018), Tandoc Jr et al. (Citation2018), and the EU Commission’s (Citation2018) report on disinformation. The markers were partly developed based on previous studies on journalistic skills (Carpenter Citation2009; Kõuts-Klemm Citation2019; Örnebring and Mellado Citation2016) and complemented with the skill-markers that are essential for a specific episode.

The interviews and the constructed episodes were adjusted during a pilot test; thus, the wording was concretised so the wording of the instruction would not influence the respondent’s replies. The episodes were based on similar real-life situations of information disorder that journalists have been exposed to in their daily practice. The respondents were told that the study is about journalistic skills and information disorder. The assignment was to discuss their thoughts verbally, sharing what they would do if exposed to this type of information. The respondents were not informed that the cases represented different types of information disorder.

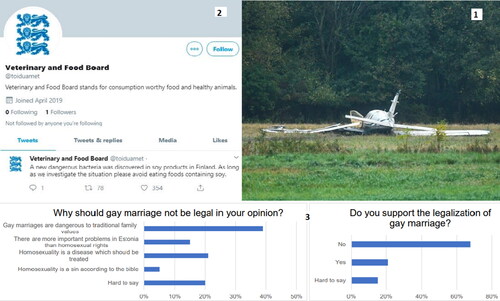

The first constructed episode contained manipulated and misleading content. It was presented as a short breaking news item containing the photo of a plane crash and the headline and a capture stating a plane had crashed in Latvia near the Estonian border and 30 people were dead. The second episode contained fabricated, imposter and manipulated content. It was a tweet referring to the Veterinary and Food Board’s official blog, which announced that hazardous bacteria was found in Finnish soy products and recommended avoiding foods containing soy. The third episode contained fabricated information with false context and a false connection with propagandistic objectives. It was a press release that was based on a fabricated social survey, but it contained a quote from a well-known sociologist; the press release also contained data visualisations that demanded simple mathematical skills to detect inconsistencies in the results. The fourth constructed episode was a short opinion article from a teenage climate activist. The text contained misinterpretations based on misleading content and false connections.

The episodes were constructed based on the literature referred to above. However, the part in the interview where the respondents described how false information might reach the newsroom also ensured that the journalists were exposed to forms of information disorder that are similar to the ones in our constructed episodes.

For the qualitative text analysis, we used the initial set of codes based on the literature. The iterative process of coding was used to improve the set of codes. Iterative coding is informed by the inductive approach in which the categories of analysis emerge from the data (Patton Citation1980; Srivastava and Hopwood Citation2009). Reflexive iteration is a systematic, repetitive and recursive process where the researcher repeatedly asks questions that serve as the framework for the data analysis; this task is carried out in the same manner each time and executed multiple times (Mills, Durepos, and Wiebe Citation2010). Through this process, we were able to add codes that reflect the journalists’ knowledge about the forms of information disorder (RQ1), collaborative fact-checking, (dis)trust in sources, transfer of responsibility and patterns of information flow (RQ2).

Findings

The presentation of the study’s results follows the order of the research questions. The findings show that while the conventional fact-checking skills may be sufficient to debunk information disorders, the work practices such as time pressure, blind trust in authorities and seemingly official communication channels may favour publishing false information. However, there are also newsroom practices that function as a back-up fact-checking support system. We begin by answering the questions about what skills and competencies journalists put into practice when doing fact-checking and debunking different forms of information disorder (RQ1).

Skills and Competencies Practiced in Fact-Checking

Based on the core journalistic skills related to information verification highlighted in the data and methods section, critical thinking is the first skill practice that was analysed; this skill is essential in selecting and verifying the information. The interview strategy did not foresee the need to define the forms of information disorder since it could have affected how the respondents analysed the constructed episodes. However, the respondents were asked about how different forms of false information might reach the newsroom. They mentioned forms of disinformation and malinformation sent by ordinary people or someone with an agenda to disseminate false information. Social media and emails in the press list were also mentioned forms of information disorder. Three respondents pointed out the propaganda that legitimates fabricated and imposter content by getting published by a journalistic platform. Propaganda was also related to advertising, which was interpreted as a sub-category of propaganda. The last types of information disorder were associated with information operations that, in Estonian cases, are often related to Russia. Journalists related this legitimation to media organisations, in general, which refers to a perceived pattern in practice.

Critical Evaluation of Tip-off

Journalists on all platforms, but especially those in online newsrooms, are exposed to tip-offs from readers and parties interested in getting their agenda published. The respondents expressed their doubts about the intentions behind the information sent to journalists. This indicates the competence related to critical thinking and enables the reporters to recognise the misinformation and malinformation. The following example shared by a newspaper and online reporter describes the pattern that is used to disseminate false information in traditional news media.

It was the time when the Conservative People’s Party of Estonia had a robust agenda against refugees. We saw that the tip-off email was flooded with links to untrustworthy pages. I didn’t even want to click on them. And then people started hysterically writing to us, asking: Why don’t you cover this? Behind the links is the real news, the mainstream media is biased, and journalists should cover the ‘real’ life. (Online reporter)

This type of example was prevalent in almost all the interviews. The respondents expressed strong distrust towards information that came from ordinary people, from tip-off emails, PR agents or activists. By default, the respondents preferred not to trust sources whose background and expertise they did not know. Most of the information that reaches the newsroom from this type of source is discarded. While distrust towards unfamiliar sources prevails, the trust towards established and well-known sources is blind. How ‘blind trust’ may facilitate the publication of false information is discussed in more detail under the results for RQ2. The trust, or distrust, towards sources is the most specific and primary performance indicator for critical thinking competence.

In this study, critical thinking is deeply integrated into visual competence and data literacy. Critical thinking is also put into practice in parallel with the evaluation of the newsworthy material. The respondents were given the constructed episode of a screen capture of a seemingly published news piece with a photo of a plane crash (marked 1 in ). The episode was presented to the respondent as if a competitive news organisation had already published it. The fact that information was already published referred to the presence of the news value (e.g. timeliness of breaking news, negativity). Although the journalists usually reconsidered the news value the moment the information turned out to be false, that initially required information verification.

Figure 2. Constructed episodes of forms of information disorder used in the think-aloud part of the interview.

The constructed episode enabled us to assess the journalists’ conduct under the time pressure conditioned by competitiveness. A clear distinction among the respondents appeared; we divided the journalists into two groups: the ‘fact-check first’ group and the ‘publish first’ group. The ‘fact-check first’ group of respondents consisted of journalists who discarded the impact of time pressure because the rival news portal had already published the information, which aligns with Usher’s (Citation2014; Citation2016) findings on the immediacy impact on content production in newspaper and online newsrooms. In doing so, they also had to re-evaluate the news values and prioritise the factualness of the news story. These respondents started to analyse the photo more critically and noted the contradictions between the visual and the textual information. They critically started to observe the photo’s details and, in the text, to look for inconsistencies in the logic. Since the text stated that there were 30 casualties, the respondents’ critical thinking quickly enabled them to recognise that the plane in the photo could not have accommodated that many people. The respondents noticed the discrepancy in the contextual information in the photo (the seasonal difference with the actual season at the time of the interview).

The ‘publish first’ group of journalists proceeded to immediate publishing the story due to the perception of time pressure. The conduct of the respondents was unusual among the journalists in our study. Still, their decision making enabled us to understand and synthesise the shortcomings in the fact-checking skill practice. The ‘publish first’ group of reporters stated that they would disseminate the information regarding the source if the source was reliable and the information was time-sensitive; in doing so, they transferred the responsibility of fact-checking to the source, enabling the journalists to gain additional time to verify the information later. The following quotes from reporters illustrate how the immediacy combined with transferring the responsibility for accuracy would be practised.

If I am the news presenter on the radio this day, I will read it with reference to the news portal where it was published. I would say that according to this news portal, there was a plane crash in this village, and up to 30 people may be dead. (Radio reporter)

If we consider this news portal trustworthy, we will publish an item referring to the initial source. (Online reporter)

The online and radio reporters made their decision to report on this news team based on the need to disseminate information immediately and in a short amount of time. This supports and supplements Usher’s (Citation2014) findings on the immediacy impact in platforms with a short publishing cycle, including radio news. Respondents mentioned that commercial media were more prone to publishing information even if it later turned out to be false or misleading; their objective for doing so is to obtain clicks even if there is a need for corrections later. This was acknowledged by both the public and commercial media journalists, and they referred to the practices of their own and other news organisations. Time pressure and the perception of competition are both dominant factors that impact the skill performance in verifying information. However, the respondents who were inclined towards ‘publishing first’ did not provide a reason for why they would analyse the photo or the text accompanying it. If the interviewer asked them to describe the possible reporting process after publishing, the respondents said they would call the police or rescue services to obtain information about the accident. This indicates the use of information verification skills by relying on human (expert) sources. Practicing critical thinking and applying visual literacy skills would have precluded the need for source verification. Postponing fact-checking may also indicate the possibility that time pressure and competition may be used as an excuse for not conducting fact-checking.

If the respondents described doing some form of fact-checking, they usually used search engines to find references to the event. This is a relatively reasonable performance of skills since it may result in finding the initial source for the information or detecting how other sources have verified the information. For this process, knowledge of foreign languages or the use of translation applications is useful. If the initial source was to be the only the source as determined by a Google search, the respondents in the ‘fact-check first’ group of journalists expressed some suspicions. Although using the Internet search engine for fact-checking may have been the starting point for finding the information and identifying the sources, the journalists in our study referred to that as not being entirely proper or trustworthy. This can be well illustrated by a quote of one online journalist in our study: “Google can be used for background information retrieval but not for verification of information.”

Based on this viewpoint and the previously highlighted practice of relying on well-informed and official human sources, it can be concluded that using traditional information verification skills is trusted and valued among journalists. With false information being spread primarily on digital platforms, the real-life human source verification method can function as a reliable back-up system.

Novel Fact-Checking Skills

In the interviews, the journalists indicated that their news organisation (employer) or media-related NGOs had provided lectures or seminars on information disorder. However, almost all of them also stated that the training usually took place during the working hours, so they could not participate. This is noteworthy since learning new skills for tackling information disorder requires actually participating in training sessions.

Since multiple forms of information disorder are mostly distributed via digital platforms (e.g. social media), it is natural to conclude that, to some extent, fact-checking on these platforms also requires new skills and competencies for information verification. Based on our results, this is only partly true. Our study’s constructed episodes enabled the respondents to use advanced technical skills for information verification (e.g. image recognition, identity verification, usage of social media functions). Nonetheless, none of the respondents considered using image verification tools (such as Google reverse image, geolocated photos of Flikr and Foto Forensics for identifying altered images) or identity verification tools (Hoverme, AnyWho, Pipl.com). The respondents did not even consider using these tools since they would not have used them in the newsroom. The interviews also revealed the respondents’ lack of awareness of the digital forensic tools and their lack of knowledge about and skills needed to use them. However, they substituted these tools with their logical deduction and critical evaluation skills, explaining the common ‘non-use’ practice in newsrooms.

Knowledge of Social Media

When a prominent person of power makes a statement on social media, it is a fact, which by its nature, is correct. However, this also enables the journalist to bypass the actual fact-checking of the statement author’s claims by presenting it as nonverifiable fact. Therefore, the prioritisation of newsworthiness may diminish the role of information verification in the actual work process. The respondents attributed very similar approaches to official institutions (e.g. state offices, government). The third constructed episode presented the respondents’ information in the form of a tweet and a blog post from the Estonian Veterinary and Food Board. The presented Twitter account had only one follower, but the tweet had 78 retweets, which demonstrates the spread of information on social media. The respondents who noticed the inconsistency would have continued looking up the initial tweet and verifying the information with the Board. This action would have resulted in recognising the manipulated content.

In particular, the deficiency of social media skills became evident in the limited perception that official accounts can be manipulated or contain fabricated or imposter content. This indicates that journalists possess knowledge of social media as users but they may not have the skill to apply this knowledge when fact-checking.

Knowledge of Topics outside the Journalistic Field

Critical thinking and the experience of working with text provide the competence needed to recognise the difference between advertising texts and journalistic texts. This is especially crucial in topics on health issues and when covering topics on finance and economy. It demands combining critical thinking with knowledge outside of the journalistic field. The fourth constructed episode was a short opinion article written by a senior in high school. The respondents evaluated the opinion story from the aspect of the source—who in their criteria were not prominent enough—and the quality of the text. One respondent analysed the information presented as facts and found the claims about environmental issues and carbon dioxide emissions to be questionable, which required knowledge outside the journalistic field. In contrast, the journalists stated that if the opinion piece had been authored by a prominent person and the quality of the text had been outstanding, the text’s factuality would not been questioned. The newsworthiness and transfer of responsibility to the author of the opinion article overshadowed and hindered the use of knowledge outside the field of journalism. We discuss the transfer of responsibility for fact-checking in more detail in the context of RQ2.

There are numerous ways to assess data-literacy skills. In this study, we limited the evaluation to assessing the quality of the presented ‘ready-made’ data and interpreting the information in a sociological study. These skills belong to the fields of sociology and statistics, which are only remotely related to journalistic knowledge. As Kõuts-Klemm (Citation2019) has pointed out, journalists lack knowledge about sociological studies and they do not have the mathematical skills to evaluate the data or its visual representations. Our results partly contradict these findings.

The respondents did a critical assessment of a press release containing the fabricated results of a sociological survey. Some of the journalists were critical of the sample, which was not representative of the entire population, and some of them were curious about the questions the survey was based upon. The ambiguity of the study was the main factor raising suspicion about its accuracy. The exclusion of a social survey due to the small sample size indicates some, but limited, science literacy knowledge in social sciences. In addition to the press release, the respondents were presented data visualisations that supported the text but contained inconsistencies in the graph (e.g. the proportion exceeded 100%) or contradicted the numbers in the text. The ability to apply a basic level of mathematics and to critically read the information would have revealed these inaccuracies. In our interviews, the journalists did not use the data-literacy skills necessary to read and understand graphs. Based on our data, it is impossible to say how or to what extent the journalists’ data-literacy skills would support their fact-checking because there are factors that incentivise the journalists to exclude this sort of information. It is also impossible to extend this finding to other countries due to the specific case of Estonia described earlier.

Summarising the skill practice analysis results, it is evident that recognising different forms of information disorder may not require unique or new skills or skills that would be far from the core journalistic skills. Instead, recognising false or misleading information requires the combined use of different skills and a self-reflexive approach to the information verification process. The perceived conduct in information verification can be influenced by several factors, which we analyse in the next section.

Factors Influencing Fact-Checking

The news reporting process contains several stages in which journalists put their skills into practice. This process is also impacted by many factors, such as time pressure in combination with the timeliness of the news, that can foster or hinder fact-checking. In previous studies, competition with other news organisations has also been highlighted as a factor that influences fact-checking (Ananny Citation2016; Himma-Kadakas Citation2017). The findings from the present study complement this knowledge in that the journalists also recognised the constructed nature of this competitiveness. In our study, one online journalist described this by connecting the factors of time pressure and competitiveness:

Timeliness is the most crucial factor since everyone wants to be first. But let’s be honest, for the reader, it does not matter which news portal publishes first. The reader does not care about it. The journalists create this so-called competition for publishing. (Online reporter)

This quote, as well as several similar interview responses, indicates the influence of newsroom practices on fact-checking. In one way or another, most of them are related to immediacy and time pressure, which we will address in the following subsections.

Conventional Patterns of Information Dissemination

The patterns of information dissemination characterise the different ways in which governmental and state institutions usually distribute information. The respondents indicated that the timing of when certain information reached the newsroom is meaningful. If the information had no connection to timely topics or events (e.g. publishing the results of scientific research), it raised the question of whose agenda was behind this information.

Journalists combined their previous experience with different skills (e.g. language skills to communicate with foreign sources in the human-to-human verification process). The analysis of the communication patterns is an important factor that implicitly gained prominence in the interviews. The journalists were familiar with how official information was usually disseminated, what channels were used to do so and which spokespersons were most likely to be informed and trustworthy. The deviation from this pattern raised suspicions and compelled the reporters to verify the source and information.

One of the television reporters whose everyday work routine did not include the time pressure for immediate publishing evaluated the visual information in more detail and instantly recognised the inconsistencies between the time of the year and the size of the plane in the first constructed episode. It is also noteworthy that the same reporter highlighted the unconventional presentation of the picture—only one picture instead of a gallery—which diverged from the usual information dissemination patterns of media organisations; this raised suspicion about the information’s truthfulness. Thus, a journalist’s knowledge of and experience with conventional information dissemination patterns is a vital supportive factor because it alerts them to a possible disturbance in the accuracy and leads to further investigation.

‘Blind Trust’ in Sources and the Transfer of Responsibility

While distrust towards unfamiliar sources is prevailing, trust towards established and well-known sources is somewhat ’blind’. In the second and third constructed episodes, the source’s official profile convinced some of the respondents that the source was trustworthy, which raised the possibility for the tweet and the press release to pass the publishing threshold. Since the tweet was published on the Veterinary and Food Board’s seemingly official Twitter account, the journalists trusted the information. The following quotes exemplify the trust in expert and institutional sources, without considering that the response that the media platform where the information was published could have been hacked or manipulated.

It is essential that the sociologist Juhan Kivirähk has commented on the results; it adds credibility to the whole study because he is a well-known sociologist. (Online reporter)

There are certain institutions that we trust./–/The Veterinary and Food Board is one of these authorities whose information we trust. But I think I would give them a call before publishing a story. (Television news reporter)

The respondents also explained that if they use secondary sources for publishing, they clearly refer to them and transfer the responsibility of factuality and accuracy to the initial source. The press release presenting the fabricated social survey data also contained a comment from a distinguished sociologist; because of that, some of the respondents considered publishing it. This shows the influence of expert source, which may promote publishing disinformation.

Based on the interviews, it can be concluded that the opinion articles from authors outside the newsroom are primarily evaluated based on the author’s public expertise and prominence. Verifying the information presented in the article is rare, or the information is treated similarly to social media posts in which the responsibility for the factuality of the information lies on the person whose opinion is presented. If the decision to publish is based on the source’s prominence and expertise, the assessment and verification may lead to disseminating false information. In the following quote from the newspaper reporter, the issue of the source’s authority—in this case, the author of an opinion article—becomes the factor that legitimatises false information.

One of the most problematic categories in Estonian newspapers is the op-ed pages where the excuse for publishing false facts is ‘the author’s opinion’. (Online reporter)

The transfer of responsibility was mentioned in all the reflections on the constructed episodes and in the examples the respondents shared in the interviews. This finding refers to the blurring of the boundaries of who is responsible for publishing false information. It is partly conditioned by the increased use of secondary sources combined with time pressure and constructed competitiveness with other media houses.

The Influence of the Platform on Skill Performance

The platform’s assets may have an impact on the journalist’s work process due to the time pressure aspect. In online and radio newsrooms, the immediacy of publishing and the pace of broadcasting set the conditions for fast publishing. This also decreases the ‘pairs of eyes’ that see, discuss and verify the information before publication. In television, there is always more than one person involved in processing the information; the editor, the cameramen, production assistants, editors and technical personnel are also exposed to the material and function as possible fact-checkers. Since television almost always needs video footage, it also means that even for a timely event, video footage from the scene is required. In the process of obtaining this footage, usually, entirely false information is excluded. The exception in television can only be when the information reaches the newsroom immediately before or during the broadcast. In this case, the lack of time is a central factor impacting the dissemination of possibly false information.

However, fabricated or manipulated video footage from foreign countries may seep into the broadcast since the editors may not verify the accuracy of the footage. In television newsrooms, to some extent, this risk is grounded in the preference for only using material from official news agencies, assessing third party material with multiple editors and searching for verification from at least two established news organisations. However, this does not apply to all forms of information disorder. As the following quote shows, the forms that are hard to verify are related to Tandoc Jr et al.’s (Citation2018) categories of propaganda and manipulation and Wardle and Derakhshan (Citation2017) categories of false connection, context and misleading context:

Let’s bring an example of Russia’s info operations. We outsource a lot of content from foreign news agencies. For example, Reuters provides all sorts of stories, pieces of information, and video footage from Russia. If the foreign news editor is there just on his own to decide, it is tough for him to distinguish what is accurate and what is false. This sort of fine-tuned disinformation aims to disseminate and get the dis- and malinformation published in mainstream media. (Online reporter)

The previous quote shows that journalists define different forms of information disorder based on the information they have been exposed to in media coverages. While Russia’s information operations have often been used as examples of disinformation, less attention has been focused on other forms of information disorder used to impact public opinion.

We can presume that television news reporters who work with video footage daily should also possess better visual information verification skills. A television news reporter described a case where a citizen source sent the newsroom a video of a fire accident on a Ferris wheel. This video turned out to be altered. Although this material would have been suitable for the television news, the information was first checked by calling the city fire department, who declared that it was fake. This example was well known among the respondents and functioned as a warning of their limited skills to recognise altered videos (and deep fakes) and photos. As online news portals are multimedia-rich environments, online reporters are equally exposed to publishing altered videos and photos. The risk increases as multimodal and data-driven content is considered more trustworthy per se (Hameleers Citation2022).

Online journalists who work under time pressure have developed creative coping mechanisms to compensate for fact-checking. Both online and newspaper reporters mentioned that they shared information with colleagues if they suspected it was inaccurate. One respondent who works for an online newsroom described this practice as a ‘collective brain’ that uses fact-checking as a task that consists of adding the roles of editors. The following quote shows how journalists practice team-work and collaboration:

It is easy to put the question in newsroom chat and ask if someone is familiar with the topic. Also, if you have worked long enough in the field you know colleagues, perhaps even from other media houses from whom you can ask. (Online reporter)

Respondents from different platforms noted that some editors are responsible for evaluating the accuracy of the information before publication on the first page of the online platform. Moreover, the fact-checking task is partly placed on the proof-readers and language editors.

The respondents indicated that the lack of time and the immediacy of the news were two factors that promoted the publishing of false information; these factors are mainly present in online and radio newsrooms. This finding is significant because it contributes to the scholarly knowledge about the differences in fact-checking practices across platforms by identifying the complexity of the conditions surrounding the fact-checking stage in news production.

Discussion and Conclusion

This article sheds light on how journalists use core skills and competencies to debunk information and it describes the reasons why false information evades the journalistic filter and gets published. Our findings show that journalists verify information by using conventional journalistic skills (e.g. verification of sources, critical thinking and knowledge of topics outside journalism). These skills are sufficient for detecting most forms of information disorder. Although critical thinking is the most crucial skill, the combination of different conventional skills bolster fact-checking.

While we argue that traditional skills (e.g. Carpenter Citation2009; Fahmy Citation2008; Lluis Citation2006; Örnebring and Mellado Citation2016) are sufficient to tackle various forms of information disorder, the question remains: what new skills and competencies should journalists obtain in changing circumstances? As multimodal and data-driven disinformation is perceived as more credible than textual disinformation (Hameleers Citation2022; Kwanda and Lin Citation2020), there is a growing need to use digital forensic tools to detect manipulated photos and videos. Our results indicate that journalists—regardless of their platform—need to become familiar with the practical features of digital tools in order to use them. Therefore, there is a need for training and a change in newsroom practices and attitudes towards the use of digital tools. This outcome should inspire journalism educators to collaborate with fact-checkers who use advanced techniques for information verification and are open-minded about collaborating with journalists, as was shown by Cheruiyot and Ferrer-Conill (Citation2018).

We identified the factors that prohibit, but also facilitate and support, the use of fact-checking skills. Regarding the prohibiting factors, a group of our respondents from different newsrooms would have easily set aside fact-checking skills while prioritising news values, such as timeliness and prominence (of the source). This finding enables us to conclude that prioritising news values, especially while working under time pressure, may overshadow the need for fact-checking. Studies on time pressure and immediacy have shown differences in newsroom practices based on the type of platform (Tsfati et al. Citation2020; Usher Citation2014; Citation2016). Our study contributes to the current body of literature by finding that the immediacy component of the publishing cycle is one of the central factors that influences fact-checking. Based on our interviews, online and radio newsrooms, with their shorter publishing cycle, were more prone to publishing misinformation and disinformation. In our sample, the journalists reporting for newspaper and television demanded more time and people and, in the production process, they executed several activities that also eliminated the possibility of publishing false information. This finding deserves further investigation in different national and cultural contexts to diversify the current knowledge about the platform’s effect on fact-checking and debunking of false information.

An important factor influencing the use of skills is the trust or distrust that occurs. Our respondents, by default, expressed distrust towards tip-offs from unfamiliar sources. This distrust usually leads to discarding the information or fact-checking it. However, our interviewees also showed blind trust in official sources or channels (e.g. social media accounts of state institutions). Similar to the findings in Wintterlin’s (Citation2020) study, the journalists’ trust in authorities ‘blinded’ them from questioning the accuracy of the information and increased the possibility of publishing unverified and false information. Trust in the official sources’ official communication channels revealed that the journalists presented information as nonverifiable facts (Tuchman Citation1978), which materialises in an effect we call the transfer of responsibility: interpreting the accuracy and truthfulness of information as the responsibility of the source.

In our study, the journalists acknowledged the decrease in trust towards journalism when false information is legitimised in the news. While increasing the transparency of news reporting could increase the audiences’ trust in journalism (Curry and Stroud Citation2021; Masullo et al. Citation2021), our study indicates a need for more research on the journalists’ skills and their willingness to ensure the transparency of their reporting. ‘Creating transparency’ with sources differs from ‘covering transparently on news reporting process’, which, in addition to journalistic skills, requires changes in attitudes and newsroom practices.

The discourse about trust leads to more discussion about the conceptual approaches of fact-checking as a stage in news reporting. The approaches used by Gans (Citation1979) and Tuchman (Citation1978) work well in the context of established legacy media, but the emerging conditions of information disorder and the abundance of information challenge their epistemologies of facts and news (Barnoy and Reich Citation2022). Our theoretical approach and empirical results support the demand to revisit the complexities of information verification routines.

Regarding the factors that facilitate and support the use of fact-checking skills, based on our results, we emphasise the conventional information dissemination patterns, which means that journalists are alerted if official or well-known sources disseminate information in unusual channels or forms. This condition is closely related to the journalists’ previous experience; therefore, it also relates to trust, which functions as a supporting factor in the information verification process.

Another supportive factor, or rather a best practice, is collaborative fact-checking in the form of peer-review, where colleagues help assess the accuracy of the information by sharing their skills and competencies (e.g. critical thinking, knowledge outside the journalistic field, social media skills). This practice can be reinforced in journalism training. Because there are clusters of countries that are more resilient to the occurrence of information disorder (Humprecht, Esser, and Van Aelst Citation2020), there may be similarities in journalistic training and practice that promote this resilience. Based on our results, we conclude that teamwork in the newsroom and high trust in reliable communication patterns may be two factors that support this resilience.

This study has some limitations. We attempted to construct an episode where journalists are exposed to fabricated sociological data. Unfortunately, our episode too closely resembled a real case in Estonia where a politically motivated NGO produced and disseminated biased sociological studies, and the participating journalists discarded the information as fabricated without further discussion. This also limited our ability to study the journalists’ data-literacy skill performance when exposed to pre-treated data and visualisations. Undoubtedly, the journalists’ knowledge about sociological studies and their ability to work with data are worth a detailed investigation in further studies.

Another limitation is conditioned by the study design. We did not want the respondents to know that we were going to determine their ability to detect false information. Therefore, we did not explicitly ask them to define the terms misinformation and disinformation. However, synthesising their answers, it can be concluded that their understanding of information disorder varies significantly and their interpretation of disinformation is drawn from its public conceptualisation in relation to Russian information operations. This side-line finding is significant as it indicates that journalists’ knowledge of disinformation comes from public communication. Nevertheless, it also indicates the need for more research on how journalists define the key concepts they need to tackle in the fact-checking process.

This study contributes to the current body of literatures by encouraging open theoretical discussion about how fact-checking, as the cornerstone of journalism, occurs under conditions of information disorder. While we offered a qualitative insight how journalists describe and rationalise their fact-checking practices and influencers of their approaches, future studies could combine quantitative and qualitative methods to investigate this complex practice in more detail in other national and cultural contexts.

Disclosure Statement

The empirical material of this article is also used in the thesis of Indrek Ojamets at the University of Tartu. The authors report no potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ananny, Mike. 2016. “Networked News Time.” Digital Journalism 4 (4): 414–431.

- Asak, Moses Ofome, and Tshepang Bright Molale. 2020. “Deconstructing De-Legitimisation of Mainstream Media as Sources of Authentic News in the Post-Truth Era.” Communicatio 46 (4): 50–74.

- Barnoy, Aviv, and Zvi Reich. 2022. “Trusting Others: A Pareto Distribution of Source and Message Credibility Among News Reporters.” Communication Research 49 (2): 196–220.

- Beiler, Markus, Felix Irmer, and Adrian Breda. 2020. “Data Journalism at German Newspapers and Public Broadcasters: A Quantitative Survey of Structures, Contents and Perceptions.” Journalism Studies 21 (11): 1571–1589.

- Capilla, Pablo. 2021. “Post-Truth as a Mutation of Epistemology in Journalism.” Media and Communication 9 (1): 313–322.

- Carpenter, Serena. 2009. “An Application of the Theory of Expertise: Teaching Broad and Skill Knowledge Areas to Prepare Journalists for Change.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 64 (3): 287–304.

- Cheruiyot, David, and Raul Ferrer-Conill. 2018. “Fact-Checking Africa.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 964–975.

- Curry, Alexander L., and Natalie Jomini Stroud. 2021. “The Effects of Journalistic Transparency on Credibility Assessments and Engagement Intentions.” Journalism 22 (4): 901–918.

- Ekström, Mats, Amanda Ramsälv, and Oscar Westlund. 2021. “The Epistemologies of Breaking News.” Journalism Studies 22 (2): 174–192.

- Ekström, Mats, and Oscar Westlund. 2019. Epistemology and Journalism. Oxford: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication.

- Erkmen, Özlem. 2020. “Reviewing the Relationship between Democracy and Data Journalism Practices in Turkey.” Connectist: Istanbul University Journal of Communication Sciences 0 (58): 65–103.

- EU Commission 2018. “Final Report of the High Level Expert Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation.” https://ec.europa.eu/digital-singlemarket/en/news/final-report-high-level-expert-group-fake-news-and-online-disinformation

- Fahmy, Shahira. 2008. “How Online Journalists Rank Importance of News Skills.” Newspaper Research Journal 29 (2): 23–39.

- Fernandes, Sarita González, and Thaïs de Mendonça Jorge. 2017. “Routines in Web Journalism: Multitasking and Time Pressure on Web Journalists.” Brazilian Journalism Research 13 (1): 20–37.

- Gans, Herbert J. 1979. Deciding What’s News. London: Constable.

- Godler, Yigal, and Zvi Reich. 2013. “How Journalists “Realize” Facts.” Journalism Practice 7 (6): 674–689.

- Graves, Lucas. 2017. “Anatomy of a Fact Check: Objective Practice and the Contested Epistemology of Fact Checking.” Communication, Culture & Critique 10 (3): 518–537.

- Hameleers, Michael. 2022. “Separating Truth from Lies: Comparing the Effects of News Media Literacy Interventions and Fact-Checkers in Response to Political Misinformation in the US and Netherlands.” Information, Communication & Society 25 (1): 110–126.

- Harro-Loit, Halliki, and Beate Josephi. 2020. “Journalists’ Perception of Time Pressure: A Global Perspective.” Journalism Practice 14 (4): 395–411.

- Himma-Kadakas, Marju. 2017. “Alternative Facts and Fake News Entering Journalistic Content Production Cycle.” Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 9 (2): 25–40.

- Himma-Kadakas, Marju. 2018. Skill Performance of Estonian Online Journalists: Assessment Model for Newsrooms and Research. Tartu: University of Tartu Press.

- Humprecht, Edda, Frank Esser, and Peter Van Aelst. 2020. “Resilience to Online Disinformation: A Framework for Cross-National Comparative Research.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 25 (3): 493–516.

- Kõuts-Klemm, Ragne. 2019. “Data Literacy among Journalists: A Skills-Assessment Based Approach.” Central European Journal of Communication 12 (3): 299–315.

- Kvale, Steinal. 1996. Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Kwanda, Febbie Austina, and Trisha T. C. Lin. 2020. “Fake News Practices in Indonesian Newsrooms during and after the Palu Earthquake: A Hierarchy-of-Influences Approach.” Information.” Communication & Society 23: 6, 849–866.

- Lluis, Micó Josep. 2006. Periodisme a la Xarxa. Vic: Eumo.

- Masullo, Gina M., Alexander L. Curry, Kelsey N. Whipple, and Caroline Murray. 2021. “The Story behind the Story: Examining Transparency about the Journalistic Process and News Outlet Credibility.” Journalism Practice 1–19.

- Mills, Albert J., Gabrielle Durepos, and Elden Wiebe. 2010. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research. (Vols. 1-0). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Örnebring, Henrik. 2016. Newsworkers: A Comparative European Perspective. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Örnebring, Henrik, and Claudia Mellado. 2016. “Valued Skills among Journalists: An Exploratory Comparison of Six European Nations.” Journalism 19 (4): 1–19.

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 1980. Qualitative Evaluation Methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Pingree, Raymond J., Brian Watson, Mingxiao Sui, Kathleen Searles, Nathan P. Kalmoe, Joshua P. Darr, Martina Santia, and Kirill Bryan. 2018. “Checking Facts and Fighting Back: Why Journalists Should Defend Their Profession.” PLoS One 13 (12): e0208600.

- Reich, Zvi, and Yigal Godler. 2014. “A Time of Uncertainty.” Journalism Studies 15 (5): 607–618.

- Shapiro, Ivor, Colette Brin, Isabelle Bédard-Brûlé, and Kasia Mychajlowycz. 2013. “Verification as a Strategic Ritual.” Journalism Practice 7 (6): 657–673.

- Srivastava, Prachi, and Nick Hopwood. 2009. “A Practical Iterative Framework for Qualitative Data Analysis.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8 (1): 76–84. ”

- Tandoc, Edson, Zheng Wei Lim, and Richard Ling. 2018. “Defining “Fake News.” Digital Journalism 6 (2): 137–153.

- Tsfati, Yariv, H. G. Boomgaarden, J. Strömbäck, R. Vliegenthart, A. Damstra, and E. Lindgren. 2020. “Rens Vliegenthart, Alyt Damstra, and Elina Lindgren. 2020.” Causes and Consequences of Mainstream Media Dissemination of Fake News: Literature Review and Synthesis.” Annals of the International Communication Association 44 (2): 157–173.

- Tuchman, Gaye. 1978. Making News: A Study in the Construction of Reality. New York: The Free Press.

- Usher, Nikki. 2014. Making News at the New York Times. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Usher, Nikki. 2016. “The Constancy of Immediacy: From Printing Press to Digital Age.” In: The Crisis of Journalism Reconsidered: Democratic Culture, Professional Codes, Digital Future, eds. Alexander, J.C., E. Breese, and M. Luengo, New York: Cambridge University Press, 170–189.

- van Someren, Maarten, Barnard Yvonne, and 1994. Jacobijn. and Sandberg The Think-Aloud Method: A Practical Approach to Modelling Cognitive. London: Academic Press.

- Wagner, María Celeste, and Pablo J. Boczkowski. 2019. “The Reception of Fake News: The Interpretations and Practices That Shape the Consumption of Perceived Misinformation.” Digital Journalism 7 (7): 870–885.

- Waisbord, Silvio. 2018. “Truth is What Happens to News.” Journalism Studies 19 (13): 1866–1878.

- Wardle, Claire. 2018. “The Need for Smarter Definitions and Practical, Timely Empirical Research on Information Disorder.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 951–963.

- Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakhshan. 2017. “Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policymaking.” Council of Europe.” Report 27: 1–108.

- Wihbey, John. 2017. “Journalists’ Use of Knowledge in an Online World.” Journalism Practice 11 (10): 1267–1282.

- Wintterlin, Florian. 2020. “Trust in Distant Sources: An Analytical Model Capturing Antecedents of Risk and Trustworthiness as Perceived by Journalists.” Journalism 21 (1): 130–145.

- Zhang, Xinzhi, and Wenshu Li. 2020. “From Social Media with News: Journalists’ Social Media Use for Sourcing and Verification.” Journalism Practice 14 (10): 1193–1210.