Abstract

Journalism of Things (JoT) is a new paradigm in digital journalism where journalists co-create sensor technologies with citizens, scientists, and designers generating new kinds of data-based and community-driven insights to provide a novel perspective on matters of common concern. This study locates Journalism of Things in existing theory and elaborates on innovation practices with the analytical lenses of boundary work and objects of journalism. Three case studies on recent award-winning journalism projects in Germany include interviews, media content analyses, and observations. The findings suggest four typical phases in JoT projects: formation, data work, presentation, and ramification. Blurred boundaries of journalism towards science and activism become apparent when co-creative JoT teams apply scientific methods and technology design while mobilizing communities. The article discusses how things (or objects) of JoT have implications on the configuration for collaborative arrangements and audience relations. By creating and disseminating new local knowledge on matters of common concern, JoT is contributing to empowering both journalism and citizens.

Introduction

The Internet of Things is fundamentally changing the world. […] [T]his development changes how we see the world and what information is collected about us. We share the conviction that this development will have long-term consequences for society, the environment, and power distribution. To be able to both critically accompany and creatively use these developments, we need a new journalism. The journalism of things. (Journalism of Things manifesto, 2019, translated by the author)

The Internet of Things (IoT) refers to networked devices such as drones, voice assistants, fitness trackers, satellites, cameras equipped with microchips, sensors, and wireless communication capabilities. The term is related to several market developments. These include the massive increase in processing power, storage capacity, and networking capabilities, the miniaturization of chips and cameras, the digitization of data, and the development of large data repositories. These developments have dramatically reduced the cost of integrating microchips, sensors, and cameras into everyday devices and increased the use of IoT technologies in various domains (Rose, Eldridge, and Chapin Citation2015).

A group of German journalists has founded the “Journalism of Things” (JoT) as a new paradigm for journalism in increasingly networked societies (Vicari Citation2019). The community signed a manifestoFootnote1 in 2019 based on which they regularly organize a JoT conference (www.jot-con.de). Several JoT projects won journalism awards. They represent examples of establishing fields of pioneer journalism (Loosen Citation2019; Loosen, Reimer, and De Silva-Schmidt Citation2020), providing “models or imaginaries of new possibilities” (Hepp and Loosen Citation2021, 5). This study aims to bring journalists’ practical and technical insights on JoT approaches into scholarly discussions of digital journalism.

The emergence of JoT can be related to two more significant trends: (1) IoT technologies have become more accessible due to open software like Arduino. (2) The digitalization of journalism has likewise led to increasingly participatory (Singer Citation2011) and open innovation practices (Aitamurto and Lewis Citation2013) for reporting and storytelling, in particular, the collection of new data (“datafication”) (Baack Citation2018) and crowdsourcing (Aitamurto Citation2016). As a new paradigm for journalism, JoT leads to novel practices and new boundaries of journalism demanding further inquiry.

Increasingly important data practices in journalism raise questions about transforming competencies and new entrants in journalism (Usher Citation2016). Datafication and activism practices affect journalism and society (Baack Citation2015; Baack Citation2018). JoT is a new trend in journalism that stands in line with a history of journalism seeking factual knowledge and objective truth (Anderson Citation2018). JoT also concerns the actual meaning of quantification for our social lives (Lowrey and Hou Citation2021).

This study analyzes three award-winning German journalism projects as cases that emerged in the JoT community. This multiple-case study uses a grounded theory approach. It comprises semi-structured interviews with JoT journalists, content analyses of media articles, web applications, and non-public documents, and observations of public journalistic events. Drawing on previous studies on boundary work (Carlson and Lewis Citation2019; Usher Citation2018), this study analyses the three JoT cases regarding unprecedented practices in journalism. Findings show a blurring of scientific and activist practices according to four observed phases of JoT projects. Based on the findings, I offer the following definition: Journalism of Things (JoT) is a new paradigm in digital journalism where journalists co-create sensor technologies with citizens, scientists, and designers generating new kinds of data-based and community-driven insights to provide a novel perspective on matters of common concern. Through the lens of object-oriented journalism (Anderson and De Maeyer Citation2015; Moran and Usher Citation2021), findings are discussed concerning questions of collaborative arrangements, audience relations, and knowledge-based empowerment.

Theoretical Framework

Sensors, Participation, and Open Innovation in Journalism

The borders between sensor journalism, data journalism, and participatory journalism are fluid. Sensors are the technical interface through which data is collected and subsequently processed for journalistic investigations and coverage. In sensor journalism, journalists apply sensor technologies, or IoT technologies, to explore and produce data-supported stories (Schmitz Weiss Citation2016; Bui 2014). Data is often provided by non-journalists who use and adopt previously distributed sensor devices or existing mobile devices (e.g. geo-location data from mobile phones). Such participatory sensor journalism is often overlooked in studies of participatory journalism that usually explore audience participation via commentary sections and social media tools (see for example, Singer Citation2011). Through distributed IoT technologies, journalists can produce new kinds of stories based on collection or aggregations of (crowdsourced) data. These practices are part of a general journalistic turn toward more reciprocal practices of audience participation and community orientation (Gutsche et al. Citation2017; Lewis, Holton, and Coddington Citation2014). The audience here can be understood in a broader way, such as citizens or organizations located in the vicinity of a journalistic outlet or groups sharing more general public concerns.

JoT is broader than participatory and sensor journalism (Loosen Citation2019), because open innovation (Chesbrough Citation2003) practices are added to the production process. Audiences, citizens, and experts participate in different stages of news production. Practices like crowdsourcing and co-creation reduce the workload for journalists as journalistic tasks are split among several or numerous people. Crowdsourcing in journalism allows generating inputs to the journalistic production process by large numbers of volunteers from the audience (Aitamurto Citation2016). The management of co-creation processes in journalism is more complicated; it requires more resources to sustain (Aitamurto Citation2013). Co-creation means working in diverse teams where different backgrounds and competencies of individuals join to achieve a common goal (Ruoslahti Citation2020; Ruoslahti Citation2018). The benefit of a co-creation process is the early adoption of a user perspective on the final product, which aims to make the results more meaningful for various stakeholder demands (Ruoslahti Citation2018).

This study unpacks the practices of JoT projects under two lenses. (1) The study of boundary work investigates journalistic activities to understand how journalists in JoT react to pressure from other directions and how they position themselves. (2) The study of objects of journalism examines diverse technical artifacts or things that have implications on journalists and their work.

Though tightly interconnected, both theory fields are introduced separately in the following to better illustrate this study’s analysis directions.

Boundary Work

Boundary work is a sociological concept increasingly used in journalism studies to grasp how practices from other fields are changing journalism. Boundaries have shifted throughout the emergence of digital journalism (Carlson and Lewis Citation2019). The study of boundary work seeks to examine how diverse players compete or collaborate while striving to define the boundaries of journalism (Carlson Citation2018). For instance, interactive journalism describes how non-traditional journalists like technologists, hackers, and scientists enter news work and create a new journalistic identity (Usher Citation2016). As a “subspecialty of traditional journalism,” interactive journalism describes how programmers train to become journalists (Usher Citation2016). Technology-savvy journalists or hacker journalists experiment with data and program new applications for a journalistic purpose while imposing new needs of skills, organization, and thinking (Usher Citation2018). Such forms of collaborative production and co-creation set new boundaries of what journalism is and can achieve and how it can impact society.

Usher (Citation2016, Citation2018) describes routine interactivity between programming and journalism. Interactive journalists would sometimes already have a partial background in Computer Science. JoT represents a time-limited journalistic project on a particular topic (e.g. air pollution, insect mortality, and bicycle safety). JoT journalists work on such topics by using interconnected things. Scientists, engineers, and designers join the project to master the complexity of IoT devices and applications. They design innovative devices and collect unprecedented data for a journalistic purpose. Acquiring expertise in highly technical topics exceeds traditional forms of journalistic expertise. JoT can be understood as co-creation with handpicked experts from other domains. These experts contribute scientific and design knowledge to journalistic production, but these people do not become journalists themselves. In this way, JoT distinguishes itself from interactive and hacker journalism. These new IoT-related entrants to the field are pushing journalistic boundaries further (Usher Citation2018) and demand further investigation.

Community work is a crucial part of JoT. This work includes the distribution of the IoT technologies among the community and active community engagement on different levels. Such forms of commitment are similar to ICT interventions (see for example, Balestrini et al. [Citation2014] and Crivellaro et al. [Citation2016]). Journalists in JoT need to become involved with the communities they create and address.

Technology and community work require skills and different modes of work that do not always comply with journalistic logic and routines. The complex nature of collaboration in JoT raises questions about participation and openness in journalism, for example, how journalists establish co-creation modes with design experts and how they arrange community participation.

Objects of Journalism

New boundaries in JoT are strongly interlinked with various “objects of journalism,” like technical artifacts, that digital journalists interact with during their work (Steensen Citation2018). Such objects are indeterminate until they are co-produced and gain agency (Usher Citation2018, 568). The theory on objects of journalism highlights the necessity to investigate the things shaping journalism (Anderson and De Maeyer Citation2015). An object-oriented study of journalism can provide a nuanced analysis of power and offer a more relational understanding of technologies (Anderson and De Maeyer Citation2015, 4). Key questions are, for instance, how diverse objects enter and leave newsrooms while transforming journalistic practice (Anderson and De Maeyer Citation2015) and what kind of feelings and experiences journalists have about these objects (Moran and Usher Citation2021). For instance, Rodgers (Citation2015) describes content management systems (CMS) as an object having multifaceted implications on journalistic work since they have become installed in newsrooms. In particular, he finds that journalistic thinking becomes more computational when journalists have to continuously deal with computational tools in their daily routine (Rodgers Citation2015).

Objects powerfully shape JoT, in which co-creative teams develop and apply connected things for a journalistic purpose. The journalistic production includes various technical objects such as cameras, sensor devices, and the related software to manage these devices and create digital stories. Working with such objects confronts journalists in JoT with multiple new practices, such as designing, testing, and applying new hardware and software prototypes. The number of objects in JoT is immense, and each object implies its functions and limitations. They also require different skills and modes of thinking. Things like low-cost sensors, data maps, and participatory apps have existed before. They have been successfully used and adapted in various fields such as engineering, science, and activism. JoT seeks to adapt these objects for journalistic storytelling.

A lack of statistical skills and data literacy in journalism is a significant issue in increasingly quantified journalism that needs careful investigation (Usher Citation2018, 355). Lowrey and Hou (Citation2021) elaborate on the critical matter that arises when journalism does not have the means to deconstruct our quantified representations of the world. Such deficiency could prevent journalists from seeing through complex constructions of social data and prevent them from fulfilling their institutional role (Lowrey and Hou Citation2021). In their manifesto, the JoT journalists underscore that “[a]nyone who wants to put alternative views of the world and thus alternative decisions up for debate must do both reproduce the data collected and carry out alternative measurement methods.” The JoT manifesto demands to adjust false or misleading information with alternative views produced by journalistically led reasoning with the help of self-developed devices and data. It is of interest for journalism and journalism studies how JoT manages to deliver balanced views and how journalists in JoT develop innovative ways to catch the audience’s attention on selected topics.

The ambitions to present the world precisely accordingly to scientific standards date back to historical conceptions of journalism, such as precision journalism. Anderson (Citation2018) chronicles the development of precision journalism, including data journalism and computational journalism, over the past century. Understanding and interpretation of quantitative evidence in journalism changed over history while different kinds of ‘data’ have continuously been used to construct evidence-based narratives (C. W. Anderson Citation2018).

It is productive to understand sensor data as journalistic evidence that helps journalists generate technologically cross-verified knowledge (Godler and Reich Citation2017). The paradigm of social epistemology distinguishes between testimony-based and technology-based knowledge in journalism (Godler, Reich, and Miller Citation2020). The first relies on eyewitnesses and secondhand human observation and reporting (Godler, Reich, and Miller Citation2020, 217f.). The second depends on the analysis and calculations, which journalists could not have captured without using technologies (Godler, Reich, and Miller Citation2020, 221f.) Journalists can use digital material to verify contested topics lacking trustful information; it would, in such cases, also have a higher hierarchical status than less trustworthy testimonies (Seo Citation2020).

The line between data creation for journalistic purposes and data activism is thin and requires further investigation. Striving for previously invisible perspectives on contentious topics shows similarities to data activism (Baack Citation2015; Baack Citation2018). Data rarely speak for itself and has to be processed and interpreted for reporting to gain agency (Baack Citation2015). Baack (Citation2015; Citation2018) illustrates how datafication is related to activism when the gathered data counters predominant narratives from authorities and governments. Also, Anderson explains that journalists would incorporate certain biases into their articles and stories to guide the audience’s attention in specific directions (Anderson Citation2018). For journalism studies, it is essential to critically examine how data is generated and disseminated for journalistic purposes. In particular, scholars may examine its uses and meanings for the audience and the circumstances and motivations that have led to the data gathering.

This study will further look at the potential for journalism that IoT technologies and data hold. The lens of object-oriented journalism studies helps this study focus on underlying values and motivations that have led to turning towards IoT technology in journalism. It serves to approach how objects in JoT might reconfigure existing discourse and power structures. Building upon the presented theoretical framework of boundary work and objects of journalism, this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

Which innovation practices emerge in JoT? What kind of phases and practices of boundary work can be observed?

What broader implications do the objects of JoT have on journalism practice, audience and society, and power relations?

Cases and Methodology

This study applies an open, exploratory research design using grounded theory for analyzing the collected material (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998, 12f.). The aim is not to reconstruct subjective views but to make underlying (social) phenomena visible. The primary goal of this study is to understand JoT’s innovation practices and their entanglement with object-related implications and new boundaries of journalism. To do so, semi-structured interviews with the journalists leading these three JoT projects were conducted. The study applies a multiple-case study design that is especially appropriate in new topic areas (Eisenhardt Citation1989) and which is still used in journalism studies, for example, to study open journalism (e.g., Aitamurto Citation2016).

The selected cases share basic features such as IoT technology application, crowdsourcing and co-creation practices, and multiple elements of sensor, data, and participatory journalism. They differ in their regional focus, their matter of common concern (i.e. air pollution, insect mortality, and bicycle safety), the particular IoT technologies in use, chosen media outlets, and styles of co-creation and crowdsourcing.

The “Air” Case: Balancing the Public Debate through Knowledge Dissemination

Feinstaubradar (English: ‘particulate matter radar’) is a project by Stuttgarter Zeitung providing a local air pollution data map and an application for structured journalism, including (real-time) data from sensors in computer-generated journalistic texts. The project idea emerged from local journalists joining regular meetings of the civic tech initiative Luftdaten.info (now: Sensor Community), which collects air pollution data through a volunteer community of citizens and maintains an alternative data map. Feinstaubradar was implemented in 2017 to transparently share air pollution data and inform about sensors’ technical issues. Feinstaubradar enriched the available public information on air pollution with three different datasets from Luftdaten.info, the authorities, and private weather stations. They aimed at raising awareness about citizen-collected data among the broader public (Hamm Citation2020). The JoT project won the 2017 German Local Journalists Award in Data JournalismFootnote2.

The “Bees” Case: raising Awareness for Insect Mortality through Monitoring Beehives

Bienenlive (English: ‘bees live’) is an experimental journalistic project from 2018 planned in the context of increasing bee mortality in Germany. The journalists equipped beehives from volunteering beekeepers with multiple sensors and a 360° camera to collect unique insect data. They adapted and reused a self-created content management system from an earlier project, allowing them to process IoT data into diversified texts automatically. For the project, both journalists were under contract by the regional German public broadcaster WDR and collaborated with an educational TV format and a radio station. The data story was published via an educational website, including three blogs, WhatsApp conversations “with” three queen bees, and multiple TV and radio reports. Bienenlive disseminated research articles on insects and service news on bee-friendly places and behaviors. The JoT project won the 2019 German Reporter Award in Multimedia.Footnote3

The “Cyclists” Case: investigating Traffic Safety through Crowdsourced Data Collection

Radmesser (English: ‘bike meter’) was conducted in 2018 and affiliated with the Berlin-based national newspaper Tagesspiegel. Together with journalists, two scientists developed an ultrasonic sensor device attached to bicycles to measure the distance between bicycles and passing cars. The journalists involved 100 volunteers from their audience (selected by a catalog of specific criteria) to collect passing distance data while cycling through the city for two months. Being passed too closely by cars on the road constitutes one of the biggest threats to cyclists (Raetzsch and Brynskov Citation2018). The project contained a journalistic data story on bicycle traffic in Berlin, an extensive survey on urban bicycle riding, and the building and testing of sensor technology in a prototyping lab. The collected sensor data was cleaned, analyzed, and visualized on an interactive website, on a data map and charts, testimonials, media articles, and public talks. The JoT project won the 2018 German Reporter Award for Data Journalism.Footnote4

Methods, Data, and Analysis

In the “cyclists” case, three of four journalists from the core team (Hendrik Lehmann/HL, Helena Wittlich/HW, David Meidinger/DM) were interviewed. In the “bees” case, two journalists who were the key innovators (Bertram Weiß/BW, Jakob Vicari/JV) were interviewed. These group interviews took place virtually due to the Covid-19 pandemic conditions from January to February 2021. In the “air” case, the interview with one journalist (Jan-Georg Plavec/JP) was conducted by telephone in December 2019. Additional data not used in a previous study (see Hamm Citation2020) was used for studying the “air” case under a different lens. The questions in the interview scheme focused on questions about the devices built and data created, the challenges and benefits of the participatory and co-creative processes, general changes in journalistic practice, and perceived implications of the JoT projects. Interviews were conducted and transcribed in German. To address ethical concerns, I asked the JoT journalists for consent to record and transcribe the interview, which they granted. They also consented to deanonymize their names and publish translated direct quotes selected to be part of this article.

Additional data on the cases have been examined to support the interpretation of the findings and overcome shortcomings of the interview method, particularly the subjectivity of the views. Twelve related media articles, three media web applications, and four internal documents have been analyzed. Two related public events have been observed in a non-participatory fashion (i.e. the 2nd JoT conference on March 18, 2021, and the Podium Feinstaub [engl. ‘Particulate Matter Panel’] on April 29, 2021).

All textual datasets were analyzed accordingly to identify emerging themes using open, axial, and selective coding (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998; cf. Aitamurto Citation2016). Themes are identified analytically by open coding as categories, and their properties and dimensions are discovered in the data (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998, 101). Four phases emerged from all three cases representing the basic categories of the case analysis. The phases are introduced as an observation of the JoT field. Axial coding is when categories become related to their subcategories (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998, 123). The four phases have been enriched with details on practices and innovation techniques through axial coding. Two underlying dimensions became apparent, one describing the similarities between JoT practices and scientific practices and the other accounting for similarities between JoT practices and activist practices. Through selective coding, the analysis is integrated and refined (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998, 143). While the interview data has been most insightful for the first two phases, the dataset of media outputs and event observations provided information, particularly in the latter two phases.

After exploring the data, I selected theoretical conceptions on boundary work and objects of journalism as analytical lenses to understand better what is new about JoT and how these innovation practices can inform Digital Journalism studies. Findings are finally discussed regarding new collaborative arrangements, audience relations, knowledge generation, and power relations in JoT projects.

Findings and Discussion

Four Phases of Journalism of Things Projects

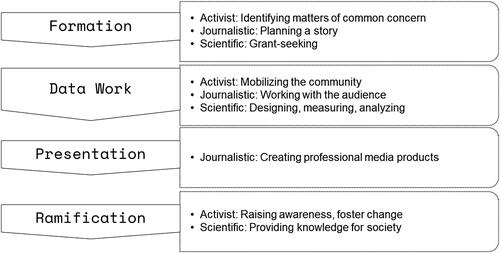

The data of the three cases reveal particular stages of journalistic production in JoT that can be summarized in four phases: formation, data work, presentation, and ramification. The phases represent working steps. Analyzed separately, they allow a more profound analysis of boundary work practices and further implications of things in journalism.

In the formation phase, the journalistic idea is developed by considering how a selected topic can be better reported using IoT technology and what kind of story can be told with IoT data. The formation phase is characterized by grant-seeking, reaching out to researchers to learn about types of data and sensor devices, and ensuring proper use of the technologies for storytelling. The JoT project is planned and organized in this phase, and the broader team joins, builds, and tests the technology.

In the data work phase, the actual content for the story is generated based on IoT data. The selected matters of common concern are approached by scientific methods, and stories become enriched with empirical data. The JoT journalists reach out to the audience and mobilize a community while co-creating with experts from science and design by adopting scientific practices. Practices include project design, prototyping, testing, data analysis, and visualization.

In the presentation phase, the story is prepared and published with the data as a crucial part. The results of IoT measurements are released in online and print format. Multimodal presentation forms can include the use of other technologies like web apps, maps, and automated texts. JoT journalists prepare the empirical data for storytelling in a professional and audience-focused manner.

Finally, the ramification phase is subsequent and does not belong to the core journalistic production process. This phase broadly encompasses audience behavioral changes and technology-based civic influence (Aragon et al. Citation2020). Ramifications can be understood as outcomes of circulations. In particular, journalistic texts are re-activated and re-contextualized after publication through digital circulation (Raetzsch and Bødker Citation2016). These may include policy changes, new regulations, and broader societal and civic awareness.

Journalistic Boundary Work

There are elements in JoT that use scientific practices and approaches but do not deal with scientific research questions. Instead, these elements involving digitally supported community mobilization deal with matters of common concern, and are thus more closely related to social activism (Hansson, Pargman, and Bardzell Citation2021). The resulting journalistic boundary work becomes increasingly blurred (Usher Citation2018) and shaped by scientific and activist practices.

Practices of journalism, science, technology design, and activism coalesce and complement each other around the emerging paradigm of JoT. Journalists in JoT seek to get to the bottom of phenomena that affect themselves and their readership. They employ scientific approaches together with domain experts from science and technology design. They design devices, the data collection process, and analysis methods, build prototypes, and interpret the data for a journalistic story. Their motivation has similarities with practices and intentions of social activism (Hansson, Pargman, and Bardzell Citation2021). The journalists identify themselves with a matter of common concern and aim at contributing to the debate moving forward. At the same time, JoT is fundamentally shaped by journalistic professionalism.

combines the four phases of JoT with insights on boundary work towards activist, scientific and design practices. In the following, both directions are elaborated in detail.

Figure 1. Blurring practices along the four observed phases of journalistic production in Journalism of Things. The phases include formation, data work, presentation, and ramification phase. The practices cover traditionally journalistic practices as well as activist and scientific practices.

Activist Practices

Journalists in JoT seek a much more active role in public discourse. It is no longer enough for them to “simply reproduce the statistics of others or quote individual interviewees” (HL). Nor is it a matter of more actively advocating their personal views. Instead, they seek to offer a novel data-driven perspective on complex matters of common concern while supporting less visible points of view.

Activist-like practices in JoT are related to journalists’ political engagement in matters of common concern. In the “cyclists” case, journalists had personal experiences with the danger posed by cars passing too closely:

“I myself ride my bike a lot in Berlin and was aware of this problem. I also feel it’s a pressing problem that there’s little measurable out there.” (“cyclists” case, HW, translated by the author)

It was “in a sense a political motivation” (“cyclists” case, HL) to carry out the JoT project. This motivation aligns with the editorial line of the Tagesspiegel that generally supports the interests of the Berlin cycling community.

In the “bees” case, journalists declared that bee or insect mortality existed for a long time, and it would be hard to tell new stories about it. To find new ways to raise awareness and support change, they focused on the question of how journalism can integrate this abstract theme into readers’ lives. Human practices like agriculture and gardening primarily cause bee and insect deaths. The project goal was to increase people’s knowledge of bee populations and their needs. This motivation results from a feeling of responsibility for the environment and its species.

Journalists in JoT created and partly mobilized a community around matters of common concern. They activate people from the audience to participate in the JoT project for a greater purpose, seeking to raise awareness, contribute to the public debate, and change people’s behavior (e.g. making their gardens bee-friendly). The participation of audiences creates added value for audiences and the broader society through the intervention of JoT journalists.

The line between JoT and activism is relatively thin. Reciprocal (Lewis, Holton, and Coddington Citation2014), advocate (Ferrucci and Vos Citation2017), and relational journalism (Lewis Citation2020) describe or demand a journalism that has a close relationship with people. Social activism describes people’s efforts to encourage social change (Hansson, Pargman, and Bardzell Citation2021). Digital technologies such as apps and sensor boxes build the backbone of the mobilized community and allow to make journalistic production more inclusive and decentralize pre-existing power structures. JoT contributes to datafication in terms of providing civic data (Hamm et al. Citation2021, 13), and journalists become “practically engaged” for data and knowledge distribution (Baack Citation2015; Baack Citation2018). JoT is collecting data together with citizens and for public needs, making the data accessible, and distributing them in society so that they can contribute to change.

Scientific and Design Practices

Scientific and design practices observed in JoT include grant-seeking, research methods, technology design, and prototyping.

In the “cyclists” case, a source of motivation was the technical challenge. The two scientists in the team wanted to answer the “nerdy question” (DM) if the passing distance of cars overtaking cyclists could be measured reliably and at scale by using a low-tech device that had not existed before. Such innovative practices in JoT show similarities to ICT interventions created by design researchers; see Balestrini et al. (Citation2017) as an example. The software and hardware design for a specific journalistic purpose requires the commitment to professional design work to ensure the quality and accuracy of the data-based sources. Lewis and Usher (Citation2013) observed elements from open-source culture to enter and transform newsrooms. Findings here show that JoT reproduces progressive principles from design research. For instance, device and data design comply with ethics (Floridi and Taddeo Citation2016) and norms of fairness (Albarghouthi and Vinitsky Citation2019), accountability (Kacianka and Pretschner Citation2021), and transparency (Eiband et al. Citation2018). Professional design and data practices are brought into journalism by domain experts and advance journalistic professionalism.

Designing new technologies and mastering existing ones requires journalists to apply for external support, particularly funding and material resources. The “cyclists” case would not have been possible without using external funding from a German organization for media innovation, the Medieninnovationszentrum Babelsberg. The grant of 30,000 EUR made it possible to temporarily employ two scientists on an hourly basis for the project period to work co-creatively with an experienced journalist and a trainee. Both scientists remained affiliated with their universities while one received a scholarship for seven months of work, the second got a fee contract for 112 working hours.

Journalists in the “bees” case obtained a grant for an earlier project in 2016 when equipping milk cows with sensors to measure their productivity and needs. The team reused the existing content management system for monitoring the bees. But even with the additional funding, the economic situation of freelancing journalists remains precarious:

If you tell someone: “we have 37,000 EUR to build hardware and software,” IT companies laugh at you because it’s just frighteningly little money. This project could only work because we put the money that we would have received as fees into software development so that it gets better. There is far too little funding for such self-developed products and technologies. (“bees” case, JV, translated by the author)

Writing a proposal includes planning a JoT project several months in advance, putting together a team of collaborators, setting a project timeframe, and eventually administering and using the funding. To emulate standard practices of scientific project planning and funding structures changes journalistic practices and institutions. Usually, journalism has been reliant on advertising revenue and subscription fees. Such transformation of revenue models from advertising to third-party funding raises questions about independence and autonomy in conceiving, selecting, reporting, and presenting news when journalism relies on third-party funding. The revenue models of journalism relate to freedom of the press and institutional functions of journalism. Journalistic performance can be partly shaped by revenue, mainly when specific funders underwrite specific projects (Ferrucci and Nelson Citation2019). The cases here did not indicate that the funding body directly influenced the topical choice of the projects. Still, the grant applications in the “bees” and the “cyclists” case have led to extraordinary innovative and technically challenging project proposals because the funding body for media innovation was calling for such.

D’Ignazio and Zuckerman (Citation2017, 206) describe speed as a significant challenge for sensor journalism. JoT requires journalists to decrease the output speed to a level comparable to producing outputs in scientific work. The planning and execution of JoT projects need institutional commitment and support, which stands in contrast to the event-driven routines of news work. Working steps like discussing with scientists, application programming, or soldering hardware parts are typically not part of news work. Media organizations need to relieve journalists from routine tasks to carry out JoT projects. Stories are published with fewer updates, and their production processes come to resemble scientific routines.

Implications of Objects in Journalism of Things

Collaborative Arrangements

The technological objects in JoT reconfigure collaborative arrangements in journalism and demand more time and new routines and knowledge from journalists. In particular, the data work phase in JoT is characterized by a strong emphasis on digital technologies and needs more in-depth discussion towards reconfiguring collaborative arrangements. In the “cyclists” case, the team realized that media offices were unsuitable for producing hardware devices and conducting test drives with 100 volunteer participants. The team moved to a co-working space for prototyping, where they could use rooms and technical equipment free of charge in turn for mentioning the location in their coverage. The co-creation with scientists to develop the IoT technology for journalism was a challenge:

To need so much lead time, to build something first before you can do journalistic work, is very unusual. […] [W]e were all involved in the hardware development at some point. Nobody else in journalism does that […] For me, another big difference was […] that two people had no idea about the [journalistic] production cycles, […] very unusual. (“cyclists” case, HL, translated by the author)

In the “bees” case, journalists have created their own media company, Sensorreporter, which employs developers and technology engineers for the more complicated technical tasks. The small company already embodies co-creation. The broadcaster engaged the company as an external service contractor for the production of the JoT project.

Sensor journalism only works if you have people on the team who are intrinsically motivated to deal with technology and who, at the same time, don’t find it difficult to talk to people for whom that might not be the case. […] My experience is that a sensor journalism project only works if you have people from both sides on the team. (“bees” case, BW, translated by the author)

Co-creation leads to a lengthy process that makes it hard and stressful to comply with journalistic publishing schedules. Sensor projects need much more time than usual journalistic projects, which leads to a clash of working routines (D’Ignazio and Zuckerman Citation2017). Such lengthy projects counter the general augmented speed in digital journalism which is described by Perreault and Ferrucci (Citation2020, 1306 f.). Journalists first need to learn and adopt certain scientific and design practices. Technical experts need to know about journalistic production. All of them depend on each other. The team of both journalists and experts is responsible for mobilizing the community and surveilling the participatory data gathering. Co-creation of three stakeholder groups (i.e. journalists, technical experts, and citizens) having multiple backgrounds and competencies seeks to achieve a common goal and provide more meaningful outputs for society (Ruoslahti Citation2020). These new collaborative arrangements are challenging initially, but they can become routine after organizing several projects in this way with the same people.

New collaborative arrangements even exceed the data work phase and lead to novel ways of working with audiences. For instance, in the “air” case, the lead journalist conceptualized and anchored a virtual discussion event related to air pollution in which diverse local stakeholders participated and debated. The local museum organized a designated exhibition on air pollution to make visitors aware of the matter’s complexity and contrast diverging interests as part of a democratic process. Such ramifications that continue bringing together different stakeholders also increase visibility towards broader audiences.

Audience Relations

Digital journalists are “not just giving the audience information […], but truly understanding what information the community needed” (Ferrucci and Vos Citation2017, 876). For example, in the “bees” case, the IoT data from the beehive was disseminated in a unique environment as one-to-one messages in WhatsApp conversations and on Instagram. Queen bee Ruby wrote messages like “The humidity makes the work really exhausting,” allowing the audience to feel sympathetic with the bees and potentially create a higher awareness of their needs. The communication via WhatsApp animated the audience to share their own experiences with bees and insects, like sending private photos from their bee-friendly garden. The journalists felt a solid connection to their audience and would have liked to continue the project with the bee community built over time. In this way, JoT is a reply to relational journalism’s demands that “puts the building and maintaining of relationships with publics it normatively serves at the center of its work” (Lewis Citation2020, 347 emphasis original).

Feedback and crowdsourcing elements of JoT allow audiences to partially shape the story from their view, similar to reciprocal journalism (Gutsche et al. Citation2017). A close relationship between journalists and readers can motivate future ties (Aitamurto Citation2013). Journalists are not acting as hard-to-reach news professionals but as people sharing the same interests with readers. Journalists are engaging in bringing matters of common concern to public attention through new modalities of digital technologies. These JoT projects found ways to realize a “hybrid resolution of the professional-participatory tension, that envisions audience integration as a normative goal of a truly digital journalism” (Lewis Citation2012, 851f.).

JoT in the present day is a continuation of a longstanding journalistic practice seeking to visualize information that dates back to old graphics in 19th-century newspapers. In the “bees” case, the monitoring of beehives created data (e.g. on kg of honey, humidity, and temperature) that makes previously invisible things visible with the help of new technologies. Such data allows catching the audience’s attention to a long-time existing topic – insect mortality. Anderson (Citation2018, 86) describes how journalists use quantitative graphic material (Dick Citation2020) to attract non-readers or speed up the information conveyance. Likewise, journalists in JoT use the unusualness and creative presentation of the IoT data to attract the audience’s attention. Continuous data updates on their devices nudge readers to keep in touch with the project.

Knowledge-Based Empowerment

The study of objects in journalism is related to questions of power and promotes a more relational understanding of technologies in and for journalism (Anderson and De Maeyer Citation2015). In politically charged debates, media can raise issues, create relevance, and provide lacking information. Often journalists rely on pre-structured data categories based on increased quantification of our social lives (Lowrey and Hou Citation2021). By reproducing “black box data categories” to which only insiders have access, potentially erroneous data categorization would become increasingly real (Porter Citation1995). However, such black boxes are not produced in JoT because the journalists empower themselves to control the technology and fully understand the data output. In this way, journalists in JoT fulfill the “epistemological responsibility of gaining a general understanding of the preconditions that have to be met in order for the technology to produce reliable outputs” (Godler, Reich, and Miller Citation2020, 222). Data in JoT designates self-produced journalistic evidence (Godler and Reich Citation2017), which journalists cross-verify by asking researchers and domain experts to evaluate the devices and the data.

For example, in the “air” case, the journalists engaged a previously non-involved research laboratory in Leipzig dedicated to air quality and air pollution to measure the reliability of the air pollution sensor device hanging in Stuttgart. Researchers confirmed that the devices have a particular deviation, and the measurements have a margin of error. They recommended several methods to clean and improve the meaning of the data. With this scientifically evaluated data product, the journalists in the “air” case aimed at calming down the heated local air pollution debate. By regularly informing on air pollution data, its construction, and meaning, they intended to reflect the complexity of the air pollution topic while not taking a position in the discussion and avoiding sensational reporting:

“The air quality issue was already highly charged in Stuttgart before Luftdaten.info started taking measurements. Car drivers were blamed, then car drivers blamed streetcars and public transport. Very politically charged. Media try to report neutrally.” (“air” case, JP, translated by the author)

The local online newspaper presented itself as a platform for public debate and tried to deescalate the discussion. The interviewed journalist was undecided if their reporting achieved this goal. The topic involved too many stakeholders, and many actions happened simultaneously. But the events convinced him that legacy media could help increase the distribution of the sensors among citizens. Because media still have an extensive range, they can appeal to local people and motivate them to hang a sensor in their homes.

The distinction between technology-based knowledge and testimony-based knowledge in journalism (Godler, Reich, and Miller Citation2020) becomes partly dissolved in JoT. Technologies and data are co-created by a journalistically led team. The JoT team takes their time designing, prototyping, and testing until the IoT technologies and applications deliver the desired outputs. Sensor devices generating evidence are distributed among citizens. Though being advised by the JoT teams, citizens have certain freedoms in using the sensor device to generate knowledge. Cyclists can choose routes perceived as more dangerous to make sure they collect insightful data on bicycle safety. Residents can decide if they hang the sensor in their yard or at the roadside windows, and thus, add their own slight bias to the overall dataset. People construct and apply IoT technology while infusing the data with their perspective.

Journalists in JoT professionally decide on the topic to cover, which strengthens journalistic independence in a democratic society while supporting the needs of citizens. Journalists conduct the JoT project with and for citizens. Both become empowered because, in JoT, citizens’ interests are covered more intensively by public media with the help of participatory IoT technologies. Journalism becomes empowered because it gains the ability to independently self-produce devices and data (with support from scientists and domain experts) to dutifully create suitable categories for adding new perspectives on matters of common concern.

Locally self-produced data in JoT can update journalism’s institutional role in society and journalists in JoT can unleash ramifications. Notably, the “cyclists” case ramified into traffic regulation changes and urban development processes about 1.5 years after the story. The StVO (German road traffic regulation) has included the explicit rule that the journalists continuously cited from case law into the regulatory text (i.e. car drivers must now respect a 1.5-meter passing distance in urban areas)Footnote5. Another ramification of this case happened during the Covid-19 pandemic when many German cities installed pop-up bicycle lanes. The authorities evaluated data from the “cyclists” case to rectify the appeal against Berlin’s Administrative Court’s ruling that declared several bike lanes illegal for lack of reasoning.Footnote6 Ultimately the case’s data contributed to some districts’ decision to turn pop-up lanes into permanent ones.Footnote7 In the “bees” case, the readers redesigned their gardens based on the service information sent together with the beehive data. Readers changed their behavior due to the JoT project on insect mortality. These ramifications show how JoT can impact society and foster behavioral and regulatory change while strengthening the societal representation of less-represented groups or species.

Conclusion

JoT emerged among developments of decreasing technology costs around the Internet of Things (Rose, Eldridge, and Chapin Citation2015) and tendencies in journalism becoming reciprocal and participatory (Gutsche et al. Citation2017; Singer Citation2011), more innovative (Aitamurto and Lewis Citation2013), and datafied (Baack Citation2015). A group of German journalists has created the term JoT and provided numerous practical and technical insights (Vicari Citation2019). Current cases of JoT represent field-making examples of journalism (Hepp and Loosen Citation2021).

In this study, I have investigated three cases of JoT. The study included interviews with journalists in JoT, observations of their public events, and reviews of related public articles and internal documents. This article translates the JoT paradigm to the scholarly discussion and offers the following extended definition: Journalism of Things (JoT) is a new paradigm in digital journalism where journalists co-create sensor technologies with citizens, scientists, and designers generating new kinds of data-based and community-driven insights to provide a novel perspective on matters of common concern. JoT is characterized by various technological objects confronting journalists with boundary work. It can be studied by considering four phases of journalistic production: formation, data work, presentation, and ramification. The phases include collaborative arrangements on different levels and result in newly created knowledge and empowerment. Practices in JoT show elements of social activism, science, and design. JoT addresses the needs of locally concerned people while borrowing methods and revenue models from science.

JoT is more complex than merely visualizing or analyzing (open) data or using social media for sourcing and audience interaction. Journalists in JoT are an essential part of the data gathering which means they are independent of other actors’ data (e.g. from research institutes and authorities). Journalists in JoT become engaged in leveraging technologies’ potential for “a better journalism.” (“bees” case, JV) The journalists are keen on novel kinds of exploring a story with data and self-built IoT boxes. Their basic idea is to provide a new perspective or understanding of a phenomenon. IoT technology is the instrument to deliver this new angle while keeping a reciprocal relationship with locally concerned people.

JoT appears to be part of a development that requires more complex forms of journalism being able to cover increasingly complex phenomena. Newly generated objects, such as devices, data, and web applications, help journalists in JoT to develop attention. JoT guides the audience’s attention in specific directions that would serve the local community and potentially the broader society. Journalists in JoT contribute to the empowerment of independent journalism and promote less visible contentious topics (e.g. air pollution, insect mortality, and bicycle safety). Journalists in JoT see a high potential in their practices to make journalism more valuable and constructive for their audience, covering matters of common concern independent of other sources and actors. While complying with codices of journalism, science, and design, journalists in JoT raise awareness through media stories and applications, which can even ramify to foster behavioral and regulatory change. The blurring of constructive activist and scientific practice is part of a general broadening of journalism.

JoT is broadening up journalism to related disciplines, fields, and systems (as suggested by Broersma Citation2018, 516), such as natural and social sciences, engineering, technology design and prototyping, social activism, and citizen engagement. Future research might focus on blurring fields and systems related to journalism because change is not limited to boundary work and objects of journalism. Change can happen in ideologies, media economic conditions, public discourse, and media ecosystems and is continuously embedded in a socio-cultural context. More case studies from different communities are needed to validate the theory on the JoT paradigm presented here. Especially, the four-phase model can benefit from a more extensive empirical base.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Christoph Raetzsch (Aarhus Universitet, Denmark) and Christoph Neuberger (Freie Universität Berlin, Germany) for their supervision and support. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive feedback.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Journalism of Things Manifesto signed by the interviewed journalists https://github.com/journalismofthings/manifesto, (last access: 03/05/2022)

2 https://www.stuttgarter-zeitung.de/inhalt.konrad-adenauer-preis-fuer-feinstaub-projekt-feinstaubradar-ausgezeichnet-big-data-im-lokalen.04739710-83ef-4b8f-94c1-29addc5f258d.html (last access: 03/05/2022)

3 2019 Archive of German Reporter Award Laureates: https://archiv.reporter-forum.de/index.php%3Fid=236.html (last access: 03/05/2022)

4 2018 Archive of German Reporter Award Laureates: https://archiv.reporter-forum.de/fileadmin/pdf/Reporterpreis_2018/RP2018_Sieger.pdf (last access: 03/05/2022)

5 https://www.pd-f.de/2020/03/09/stvo-aenderung-zehn-wichtige-punkte-fuer-radfahrer_14628 (last access: 02.12.2021)

References

- Aitamurto, Tanja. 2013. “Balancing between Open and Closed.” Digital Journalism 1 (2): 229–251.

- Aitamurto, Tanja. 2016. “Crowdsourcing as a Knowledge-Search Method in Digital Journalism.” Digital Journalism 4 (2): 280–297.

- Aitamurto, Tanja, and Seth C. Lewis. 2013. “Open Innovation in Digital Journalism: Examining the Impact of Open APIs at Four News Organizations.” New Media & Society 15 (2): 314–331.

- Albarghouthi, Aws, and Samuel Vinitsky. 2019. “Fairness-Aware Programming.” In Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 211–219. FAT* ’19. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Anderson, Christopher William. 2018. Apostles of Certainty: Data Journalism and the Politics of Doubt. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Anderson, Christopher William, and Juliette De Maeyer. 2015. “Objects of Journalism and the News.” Journalism 16 (1): 3–9.

- Aragon, Pablo, Adriana Alvarado Garcia, Christopher A. Le Dantec, Claudia Flores-Saviaga, and Jorge Saldivar. 2020. “Civic Technologies: Research, Practice and Open Challenges.” In Conference Companion Publication of the 2020 on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, 537–545. CSCW ’20 Companion. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Baack, Stefan. 2015. “Datafication and Empowerment: How the Open Data Movement Re-Articulates Notions of Democracy, Participation, and Journalism.” Big Data & Society 2 (2): 205395171559463.

- Baack, Stefan. 2018. “Practically Engaged: The Entanglements between Data Journalism and Civic Tech.” Digital Journalism 6 (6): 673–692.

- Balestrini, Mara, Jon Bird, Paul Marshall, Alberto Zaro, and Yvonne Rogers. 2014. “Understanding Sustained Community Engagement: A Case Study in Heritage Preservation in Rural Argentina.” In Proceedings of the 2014 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2675–2684. CHI ’14. Toronto, ON: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Balestrini, Mara, Yvonne Rogers, Carolyn Hassan, Javi Creus, Martha King, and Paul Marshall. 2017. “A City in Common: A Framework to Orchestrate Large-Scale Citizen Engagement around Urban Issues.” In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2282–2294. Denver, CO: ACM.

- Broersma, Marcel. 2018. “Epilogue: Situating Journalism in the Digital. A Plea for Studying News Flows, Users, and Materiality.” In The Routledge Handbook of Developments in Digital Journalism Studies, edited by Scott A. Eldridge and Bob Franklin, 1st ed, 515–526. London: Routledge.

- Carlson, Matt. 2018. “Boundary Work.” In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, edited by Tim P. Vos, Folker Hanusch, Dimitra Dimitrakopoulou, Margaretha Geertsema-Sligh, and Annika Sehl, 1st ed., 1–6. New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell.

- Carlson, Matt, and Seth C. Lewis. 2019. “Boundary Work.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Chesbrough, Henry William. 2003. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Crivellaro, Clara, Alex Taylor, Vasillis Vlachokyriakos, Rob Comber, Bettina Nissen, and Peter Wright. 2016. “Re-Making Places: HCI, ‘Community Building’ and Change.” In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2958–2969. CHI ’16. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery.

- D’Ignazio, Catherine, and Ethan Zuckerman. 2017. “Are We Citizen Scientists, Citizen Sensors or Something Else Entirely? Popular Sensing and Citizenship for the Internet of Things.” In International Handbook of Media Literacy Education, edited by Belinha S. De Abreu, Paul Mihailidis, Alice Y. L. Lee, Jad Melki, and Julian McDougall. New York ; London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Dick, Murray. 2020. The Infographic: A History of Data Graphics in News and Communications. Cambridge, Massachusetts/London, England: MIT Press.

- Eiband, Malin, Hanna Schneider, Mark Bilandzic, Julian Fazekas-Con, Mareike Haug, and Heinrich Hussmann. 2018. “Bringing Transparency Design into Practice.” In 23rd International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, 211–223. IUI ’18. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” The Academy of Management Review 14 (4): 532–550.

- Ferrucci, Patrick, and Jacob L. Nelson. 2019. “The New Advertisers: How Foundation Funding Impacts Journalism.” Media and Communication 7 (4): 45–55.

- Ferrucci, Patrick, and Tim Vos. 2017. “Who’s in, Who’s out?” Digital Journalism 5 (7): 868–883.

- Floridi, Luciano, and Mariarosaria Taddeo. 2016. “What is Data Ethics?” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 374 (2083): 20160360.

- Godler, Yigal, and Zvi Reich. 2017. “Journalistic Evidence: Cross-Verification as a Constituent of Mediated Knowledge.” Journalism 18 (5): 558–574.

- Godler, Yigal, Zvi Reich, and Boaz Miller. 2020. “Social Epistemology as a New Paradigm for Journalism and Media Studies.” New Media & Society 22 (2): 213–229.

- Gutsche, Robert E., Susan Jacobson, Juliet Pinto, and Charnele Michel. 2017. “Reciprocal (and Reductionist?) Newswork: An Examination of Youth Involvement in Creating Local Participatory Environmental News.” Journalism Practice 11 (1): 62–79.

- Hamm, Andrea. 2020. “Particles Matter: A Case Study on How Civic IoT Can Contribute to Sustainable Communities.” In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on ICT for Sustainability, 305–313. Bristol, United Kingdom: ACM.

- Hamm, Andrea, Yuya Shibuya, Stefan Ullrich, and Teresa Cerratto Cerratto Pargman. 2021. “What Makes Civic Tech Initiatives to Last over Time? Dissecting Two Global Cases.” In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–17. Yokohama, Japan: ACM.

- Hansson, Karin, Teresa Cerratto Pargman, and Shaowen Bardzell. 2021. “Materializing Activism.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 30 (5–6): 617–626.

- Hepp, Andreas, and Wiebke Loosen. 2021. “Pioneer Journalism: Conceptualizing the Role of Pioneer Journalists and Pioneer Communities in the Organizational Re-Figuration of Journalism.” Journalism 22 (3): 577–595.

- Kacianka, Severin, and Alexander Pretschner. 2021. “Designing Accountable Systems.” In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 424–437. FAccT ’21. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Lewis, Seth C. 2012. “The Tension between Professional Control and Open Participation.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (6): 836–866.

- Lewis, Seth C. 2020. “Lack of Trust in the News Media, Institutional Weakness, and Relational Journalism as a Potential Way Forward.” Journalism 21 (3): 345–348.

- Lewis, Seth C., Avery E. Holton, and Mark Coddington. 2014. “Reciprocal Journalism: A Concept of Mutual Exchange between Journalists and Audiences.” Journalism Practice 8 (2): 229–241.

- Lewis, Seth C., and Nikki Usher. 2013. “Open Source and Journalism: Toward New Frameworks for Imagining News Innovation.” Media, Culture & Society 35 (5): 602–619.

- Loosen, Wiebke. 2019. “Vorwort.” In Journalismus Der Dinge: Strategien Für Den Journalismus 4.0, edited by Jakob J. E. Vicari. Praktischer Journalismus 107. Köln: Herbert von Halem Verlag.

- Loosen, Wiebke, Julius Reimer, and Fenja De Silva-Schmidt. 2020. “Data-Driven Reporting: An on-Going (r)Evolution? An Analysis of Projects Nominated for the Data Journalism Awards 2013–2016.” Journalism 21 (9): 1246–1263.

- Lowrey, Wilson, and Jue Hou. 2021. “All Forest, No Trees? Data Journalism and the Construction of Abstract Categories.” Journalism 22 (1): 35–51.

- Moran, Rachel E., and Nikki Usher. 2021. “Objects of Journalism, Revised: Rethinking Materiality in Journalism Studies through Emotion, Culture and ‘Unexpected Objects.” Journalism 22 (5): 1155–1172.

- Perreault, Gregory P., and Patrick Ferrucci. 2020. “What is Digital Journalism? Defining the Practice and Role of the Digital Journalist.” Digital Journalism 8 (10): 1298–1316.

- Porter, Theodore M. 1995. Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Raetzsch, Christoph, and Henrik Bødker. 2016. “Journalism and the Circulation of Communicative Objects.” TECNOSCIENZA: Italian Journal of Science & Technology Studies 7 (1): 129–148.

- Raetzsch, Christoph, and Martin Brynskov. 2018. “Challenging the Boundaries of Journalism through Communicative Objects: Berlin as a Bike-Friendly City and #Radentscheid.” https://futuremaking.space/challenging-boundaries-journalism-communicative-objects-berlin-bike-friendly-city-radentscheid/.

- Rodgers, Scott. 2015. “Foreign Objects? Web Content Management Systems, Journalistic Cultures and the Ontology of Software.” Journalism 16 (1): 10–26.

- Rose, Karen, Scott Eldridge, and Lyman Chapin. 2015. The Internet of Things: An Overview. Reston, USA: The Internet Society (ISOC).

- Ruoslahti, Harri. 2018. “Co-Creation of Knowledge for Innovation Requires Multi-Stakeholder Public Relations.” In Public Relations and the Power of Creativity (Advances in Public Relations and Communication Management, edited by Sarah Bowman, Adrian Crookes, Stefania Romenti, and Øyvind Ihlen, vol. 3, 115–133. Bingley, West Yorkshire, England: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Ruoslahti, Harri. 2020. “Complexity in Project Co-Creation of Knowledge for Innovation.” Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 5 (4): 228–235.

- Schmitz Weiss, Amy. 2016. “Sensor Journalism: Pitfalls and Possibilities.” Palabra Clave - Revista de Comunicación 19 (4): 1048–1071.

- Seo, Soomin. 2020. “We See More Because We Are Not There’: Sourcing Norms and Routines in Covering Iran and North Korea.” New Media & Society 22 (2): 283–299.

- Singer, Jane B., ed. 2011. Participatory Journalism: Guarding Open Gates at Online Newspapers. Chichester, West Sussex, UK; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Steensen, Steen. 2018. “What is the Matter with Newsroom Culture? A Sociomaterial Analysis of Professional Knowledge Creation in the Newsroom.” Journalism 19 (4): 464–480.

- Strauss, Anselm L., and Juliet M. Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Usher, Nikki. 2016. Interactive Journalism: Hackers, Data, and Code. USA: University of Illinois Press.

- Usher, Nikki. 2018. “Hacks, Hackers, and the Expansive Boundaries of Journalism.” In The Routledge Handbook of Developments in Digital Journalism Studies, edited by Scott A. Eldridge and Bob Franklin, 1st ed., 348–359. London: Routledge.

- Vicari, Jakob J. E. 2019. Journalismus Der Dinge: Strategien Für Den Journalismus 4.0. Praktischer Journalismus 107. Köln: Herbert von Halem Verlag.