Abstract

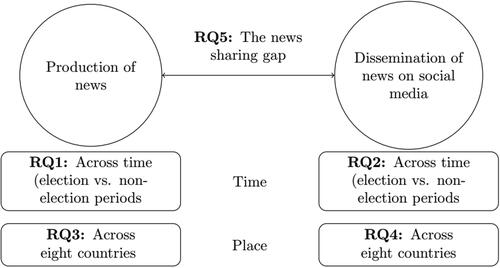

Are journalists and Facebook users equally interested in political news? Introducing the conceptualization and measurement of the “news sharing gap”, this study compares the sharing of political news by Facebook users to the production of political news by news media organizations. To paint a broad picture of these differences, we compare the news sharing gap (a) across election and routine periods and (b) across eight countries: Australia, Austria, Brazil, Germany, the Netherlands, Romania, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Analyzing 265,714 articles shared over 12 million times on Facebook, findings show that elections are broadly linked to increases in political news publication, but even larger increases in political news sharing. The study reveals how, overall, political news is shared more often than news publication patterns would suggest, proposing higher political interest by Facebook users than previously thought. In most cases, political news sharing far outpaces political news production in the form of a “negative” news sharing gap, with the relative demand for political news (in the form of news sharing) being higher than the supply. Lastly, building upon previous work, we propose and validate a distant supervised machine learning method for multilingual, large-scale identification of political news across distinct languages, contexts and time periods.

Introduction

Past work has argued that systematic differences exist in the interest afforded to political news by journalists and their audiences (Boczkowski and Mitchelstein Citation2013). Most of this work has focused on readership as the primary metric of audience demand for news; with the rise of social media, however, new forms of news engagement have emerged beyond readership. This is the case with news sharing—today, on social media, users can easily redistribute news items to extensive networks well beyond a news organization’s original and intended audience (Kümpel, Karnowski, and Keyling Citation2015). Because of the implications news sharing has for online information networks, it is paramount to understand not only differences between news publication and news readership but also differences with news sharing.

Therefore, in the current study, we explore whether journalists are more interested in publishing political news than social media users are in sharing it. Building on the idea of the “news gap” (Boczkowski and Mitchelstein Citation2013), de León, Vermeer and Trilling (Citation2021) examined what journalists choose to publish and what audiences choose to share on social media in Mexico. The results indicate that during election periods, political news was shared at a rate far outpacing political news publication. This raises questions on whether the traditional news gap, where journalists are understood as more interested in politics than the general public, can be directly extrapolated to alternative measures of audience engagement, such as news sharing. In this article, we examine how audiences on Facebook challenge the classical understanding of the “news gap.”

Expanding the work conducted by de León, Vermeer and Trilling (Citation2021), we propose the conceptualization and measurement of the news sharing gap—the extent to which the interest in political news diverges between journalists producing news and social media actors disseminating it. We argue that this gap is dynamic by nature, standing in stark contrast to the relative stability of institutionalised media companies. To understand these patterns, we make use of the useNews dataset (Puschmann and Haim Citation2020)—with 265,741 articles shared over 12 million times on Facebook—to estimate the prevalence and size of the news sharing gap in eight countries: Austria, Australia, Brazil, Germany, the Netherlands, Romania, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

In The News Gap, Boczkowski and Mitchelstein (Citation2013) showed that elections significantly reduce the differences between journalists’ and readers’ interest in political news. During these moments of heightened political attention, the gap between editorial and audience supply and demand for political news become more evenly matched, reducing the news gap. We pose that the news sharing gap might witness similar—if not greater—fluctuations, as past work has shown the outsized effect elections have on political news sharing (de León, Vermeer and Trilling Citation2021; de León and Trilling Citation2021). Therefore, for each country in our sample, we compare the development of the news sharing gap between election and routine periods.

By doing so, we contribute to our understanding of digital journalism in three critical ways. First, we aim to understand the extent to which engagement with political news differs across periods of varying political activity in relation to the attention afforded by journalists. Second, we contribute to comparative communication scholarship by extending the measure to eight countries in both the Global North and South. Finally, methodologically, studying news dissemination patterns is complex. We showcase how computational methods can help conduct large-scale analyses of the links between journalism and social media. We provide a methodological approach based on distant supervision machine learning to distinguish political from non-political news, allowing for automated classification of political content across languages, countries, and contexts. In doing so, we are not only able to provide sophisticated insights into news sharing patterns around the globe, but we also contribute to a research agenda on social media news engagement that allows for large scale country-period comparisons.

The News Gap: From Reading to Sharing

A significant stream of scholarship focuses on the gap in preferences between journalists and news consumers, where journalists consider stories about politics to be more newsworthy than others (Fishman Citation1980). Despite this ample supply of political news, citizens choose to read non-political news content instead (Prior Citation2007). As a result, Boczkowski and Mitchelstein (Citation2013) introduced the notion of the “news gap” between the publishing and reading of political news. Several studies have generated comparable evidence of a significant gap between consumers’ news preferences (as measured by the number of clicks, visits, or views) and the news items editors or journalists deem important (Boczkowski, Mitchelstein, and Walter Citation2011; Boczkowski and Peer Citation2011; Choi Citation2021). Recent work has expanded the conceptualization of the news gap to include moments of large-scale crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In their study of the pandemic coverage, Masullo, Jennings, and Stroud (Citation2021) identify key differences between the topics covered by news organization and individuals' self-reported preferences for news topics in the United States—what they term the “crisis coverage gap.” Their findings broadly support previous understanding of the news gap. They show that while consumers routinely voiced a preference for “soft” news focusing on measures taken by local grocery stores and fact-checking information, news outlets oversupplied “hard” COVID-19 topics on the economic impact of the virus and how measures were affecting businesses.

Today, journalists are no longer the sole gatekeepers of news—on social media, citizens are incidentally exposed to news shared by connections and can share news themselves (Nelson and Webster Citation2017). News sharing, therefore, impacts incidental exposure (Feezell Citation2018; Weeks et al. Citation2017); is tied to the normative echo chamber concerns (Thorson et al. Citation2021); and is a crucial element in the erosion of the gatekeeping function of the media, with social media actors empowered to shift attention and information beyond editorial preferences (Thorson and Wells Citation2016). While there is considerable research about why citizens choose to share news (Kümpel, Karnowski, and Keyling Citation2015), hardly any work has addressed whether there is a difference between the news that users share on social media and the news published by news media organizations. With its enhanced media choice and user selectivity (Bennett and Iyengar Citation2008; van Aelst et al. Citation2017), today’s digital news landscape may increase the likelihood of divergence between editors and news consumers. We, therefore, propose that to correctly understand the relationship between news production and distribution in today’s digital society, we must bring the role of news sharing into the folds of the news gap.

To understand the relationship between news sharing and publishing, we put forward the idea of a distinct “news sharing gap”—the difference between what journalists choose to publish and what social media audiences choose to redistribute. Such a gap needs to be understood in relation to the user environment provided by social media more broadly, and Facebook specifically, as its technical aspects and affordances shape how today’s online information flows occur. Platform affordances, the “perceived” and “actual” features of social media, “determine just how the thing could possibly be used” (Norman Citation1988, p. 9), therefore redefining the boundaries of how news can be engaged with and disseminated. This includes the availability of basic technical features, such as a “share” button (Gerlitz and Helmond Citation2013), as well as more abstract notions of scalability (Boyd Citation2010), and “affective” affordances that influence how users can engage emotionally with news content (de León and Trilling Citation2021; Sturm Wilkerson, Riedl, and Whipple Citation2021). News sharing is also shaped by the content incentives placed in the “Like economy” (Gerlitz and Helmond Citation2013) and internal algorithmic curation promoting specific material (dos Santos, Lycarião, and de Aquino Citation2019).

Sharing therefore needs to be understood as behaviour that is distinct to that of reading, and that is responsive to the constraints and opportunities presented by social media platforms. In the past, scholars have been normatively optimistic about online audiences, proposing that articles are not shared if they are not first read (Bright Citation2016). Today, we know that the affordances of these platforms allow this not to be the case: in 2020 Twitter introduced a “are you sure you don’t want to read this before sharing?” warning to users attempting to do so (Twitter Citation2020). Social media platforms allow consumers to decide whether they want to share a story by glancing at a headline (Mosleh, Pennycook, and Rand Citation2020), with stories dominating online attention when they previously had little traction, and despite being of low quality (Caldarelli et al. Citation2020; Qiu et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, algorithmic curation has meant that ideologically extreme news sites on Facebook are the ones being interacted with the most (Hiaeshutter-Rice and Weeks Citation2021), despite only receiving a fraction of the readership of established news organisations.

When thinking about the dissemination of news on social media, and its difference from news publishing, it is also essential to understand that citizens looking to be informed are not the only actors sharing political news, as is a common assumption in the literature (Woolley and Howard Citation2017). The ease of communication, engagement and dissemination provided by platform affordances mean political actors have much to gain from social media and the sharing of particular information on these platforms (Bradshaw et al. Citation2020; Caldarelli et al. Citation2020; Farkas and Bastos Citation2018). As a result, politicians, bots, organizations, pages monetizing heated partisan engagement on news, campaign strategists, and activists play a key role in political news dissemination (Bradshaw et al. Citation2020). This type of dissemination, which goes beyond the ideal of the “citizen trying to share news with their friends,” has been linked to both the spread of misinformation and political propaganda (Shao et al. Citation2018), as well as to the spread of mainstream news (Santini et al. Citation2020). This is especially the case during elections (Howard et al. Citation2017; Shao et al. Citation2018). Therefore, when engaging with the aggregate sharing counts that social media companies supply for these analyses, we cannot assume that it is conformed uniquely of engaged citizens.

Lastly, the high-choice media environment—which has long been the suspected culprit for decreasing political news readership (Prior Citation2007)—may very well have a different effect on political news sharing. Previous research focusing on the links between individual-level traits and news sharing has shown that it is those with high political interest that are most likely to share any kind of news (Karnowski, Leonhard, and Kümpel Citation2018; Wadbring and Odmark Citation2016). As such, these individuals have an outsized impact on what information is redistributed. Additionally, partisan strength has been shown to be a strong predictor of overall news sharing (Weeks and Holbert Citation2013). More recent work has confirmed this relationship, as well as in relation to misinformation, with partisan polarization being the main sharing driver (Osmundsen et al. Citation2020).

Taken together, the idea of the news sharing gap aims to conceptualize the diverging interests in news between journalists and consumers while recognizing that news sharing follows distinct patterns. The implications for journalism are straightforward: the existence of this gap should directly inform how media organizations are either over- or under-serving news to their publics. The ramifications, however, go beyond this. The existence and perpetuation of a news sharing gap has implications for our understanding of online audiences in dynamic democracies. Increasingly, work in the digital sphere has argued that the information people can counter online—whether selectively or incidentally—can influence their involvement in political processes. Significant discrepancies between journalists and what is being distributed on social media can have an impact on a citizen’s perception of what is important and what is currently happening in the world. More importantly, however, it links back to Prior’s ideas of information inequality. People who rely on social media platforms as their main access point to news may be presented with a distorted picture of the news agenda. It puts the media agenda into the hands of those most politically interested, the most vocal, and those who feel they have a stake in politics.

To understand the news sharing gap, it is necessary to look beyond a single time period and country. We focus on the political context, as de León, Vermeer, and Trilling’s (Citation2021) findings showed that different political seasons resulted in large changes in the differences between political news production and redistribution: election campaigns increase political news sharing to an extent that far outpaces its production by media organizations. We, therefore, explore whether this is a pattern that extends beyond a single case study.

Elections Periods vs. Routine Periods

First, to examine the dynamics of the news sharing gap, we compare routine and election periods for news production and dissemination.

The Production of Political News

First, we discuss the role of time periods, particularly how election campaign periods can impact news production. There are numerous reasons why election campaign periods are unique (van Aelst and de Swert Citation2009). On the supply side, political parties and candidates draw more media attention to reach voters. On the demand side, voters read more political news, hoping to determine which party is closest to their own political preferences. Since journalists are confronted with more active political parties and candidates, as well as a more attentive electorate, their importance increases during electoral campaigns (Druckman Citation2005) as they provide voters with sufficient political information (Strömbäck Citation2005).

However, not all elections are the same. Although it has since come under criticism (Nielsen and Franklin Citation2016), Reif and Schmitt (Citation1980) indicated differences between first-order elections (e.g. national parliamentary and presidential elections) and second-order elections (e.g. municipal elections and European elections), as there is less at stake during second-order elections. As a result, second-order elections are met with lower levels of participation and with voters who are less prepared to accept political news as important. Therefore, these types of elections might have a differential effect on political news production.

Few studies have compared election and routine periods to examine changes in political news coverage. According to van Aelst and de Swert (Citation2009) media coverage of political news differs substantially between these, with an upcoming election boosting the coverage of politics in the news. Vliegenthart, Boomgaarden, and Boumans (Citation2011) found a stronger primacy for political parties during election campaign periods compared to routine times. Zaller (Citation2003) argues that increased coverage of political news during election periods is a way of media adhering to “the Burglar Alarm standard,” according to which journalists “call attention to matters requiring urgent attention, […] in excited and noisy tones” (p. 122).

The question remains as to whether this is a pattern that can be traced across numerous contexts. Here, we aim to examine the extent to which the production of political news varies across routine and election periods, including general elections (e.g. in Brazil), legislative elections (e.g. in Austria), and provincial elections (e.g. in the Netherlands). We pose the following question:

RQ1: To what extent does the production of political news differ across time (election vs. routine periods)?

The Dissemination of Political News

To date, literature on news sharing in election periods is sparse. While previous research has examined citizens’ news sharing habits during elections (Ørmen, Citation2019), they do not address how these dissemination patterns differ from routine periods. It is essential to compare differences in dissemination patterns between election periods and routine periods because it can help understand the so-called audience turn in journalism (Meijer Citation2020). For instance, most news organization track how much time news consumers spent on which news and their engagement through clicking, sharing, and commenting. Building on the notion of the social news gap, de León, Vermeer, and Trilling (Citation2021) examined the gap between the production and the dissemination of political news on social media. Focusing on the context of Mexico, they found that a divergence exists between what journalists choose to publish and what audiences choose to share on social media, which is particularly true for political news. Interestingly, this gap dramatically reduces during election periods. In other words–during election periods–journalists’ interest in publishing political news increases but is far outpaced by the increase in political news sharing behaviour.

Taken together, the current study aims to examine to what extent the dissemination of political news varies across time. We aim to understand whether the findings of de León, Vermeer, and Trilling (Citation2021) might apply to other elections in the rest of the world. Therefore, we pose the following research question:

RQ2: To what extent does the dissemination of political news on Facebook differ across time (election vs. routine periods)?

Differences across Countries

Besides addressing the effect of political seasons, we address differences across countries. In this study, we focus on Austria, Australia, Brazil, Germany, the Netherlands, Romania, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

The Production of Political News

Election campaigns have attracted a great deal of attention in comparative communication research. Various scholars have examined how national election campaigns are portrayed across different news systems (Esser and Strömbäck Citation2013). With increased modernization and professionalization across the globe, there are disparate theoretical positions on whether journalistic practices and news media content have become similar or maintain distinctive characteristics. Some propose that news production has become increasingly homogenized across countries (due to the secularization of politics and transnational media conglomerates, see Kaid and Strömbäck Citation2009; Murray Citation2005; Swanson Citation2004). Empirically, scholars find that differences across countries have diminished: Shoemaker and Cohen (Citation2006) established that across ten countries, approximately two thirds of all news stories focused on the same topic, like Kaid and Strömbäck (Citation2009) study on 22 countries. Other scholars claim that notwithstanding the factors that might steer global journalism towards convergence, journalistic practices and news content differ because countries have distinct media cultures, influenced by political and legal systems (McQuail Citation1987; Merrill Citation2009). With this background, we ask:

RQ3: To what extent does the production of political news differ across countries?

The Dissemination of Political News

Country-differences might not only affect journalistic practices, but also news dissemination patterns. Yet, we have comparatively little evidence of this. Recently, Trilling et al. (Citation2022) examined news sharing behaviour in four multi-party systems covering significant variation across countries in Europe. They found that, despite their different media systems and political systems, the underlying processes and sharing patterns in the four countries are remarkably similar. In the current study, we extend the comparative analysis beyond a framework centered on merely European countries to understand the dissemination of political news. We pose the following research question:

RQ4: To what extent does the dissemination of political news on Facebook differ across countries?

RQ5: To what extent does the news sharing gap differ across (a) time (election vs. routine periods) and (b) countries?

Method

Data

We utilize the useNews dataset (Puschmann and Haim Citation2020) to examine how the publication and sharing of political news changed from routine to electoral periods in eight countries (see Table 1). The useNews dataset supplies (a) scraped news media content, and (b) Facebook engagement metrics for these. We focus on Austria, Australia, Brazil, Germany, the Netherlands, Romania, Spain, and the United Kingdom. In all countries, Facebook is the most popular social media platform for news (Newman et al. Citation2020).

Topic Classification

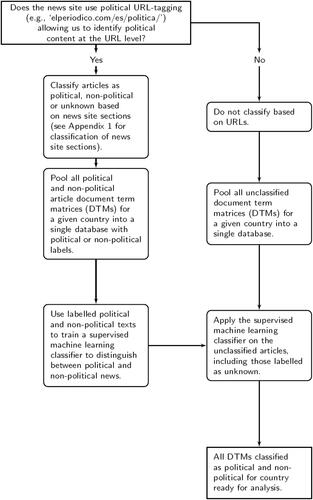

To classify the topic of news items as political or non-political, we use a three-step process to build supervised machine learning classifiers (see ; Flaxman, Goel, and Rao Citation2016; Guess Citation2021) that takes a distant supervision approach to training (Go, Bhayani, and Huang Citation2009). Instead of producing a training dataset based on manual classification of news articles, we rely on “distant” cues that are present in article-URLs. We exploit the fact that many news sites have explicit “political” and “non-political” sections that are reflected in each article URL (e.g. “www.elperiodico.com/es/politica/.” vs. “www.elperiodico.com/es/cultura/.”). We therefore use the signals provided by journalists themselves as our tool to decide whether an article is political or not. To maximize the number of articles used for training, we made use of the entire useNews dataset, which is split into two periods: from 01/09/2018 to 31/10/2019, and from 01/11/2019 to 01/09/2020.

First, we identified all news websites that have an explicit political section on their website that is reflected in the construction of the web page URLs. With these sites, we inductively annotated all sections that contained more than 200 articles, manually classifying each as either political (e.g. “/politics/”), non-political (e.g. “/celebrities/”), or unclear (e.g. “/national/”; see Appendix 1 for the full list of labelled sections). Using this process, a total of 154,832 political and 388,283 non-political articles were identified, while for 486,857 articles this was unclear. A total of 778,286 articles belonged to news sites without explicit political URL-tagging (see Appendix A, Table 3).

Second, news sites with political sections in their URLs served as the training material for the classifiers. Here the Quanteda R software package was used to work with the Document Feature Matrices (DFMs) provided by the useNews project. All articles were pre-processed by stop word removal and stemming. First, a keyness analysis was conducted to gauge the difference between the two political and non-political corpora, showing significant differences (Appendix 3). Next, classifiers were trained using the Naive Bayes algorithm. For each country period, articles were split into a training (75%) and test (25%) set, resulting in 16 classifiers (one for each country period), with performance above .82 F1-score for all models except for the Netherlands (see Appendix 2, Table 4 for details). To validate the classification method, for each country we withheld a URL-classified site, trained the classifier on the remaining sites, and then tested their performance against the withheld site, revealing F1-scores above .79 (Appendix B, Table 6). Classifiers were also validated on a stratified random sample of articles that were manually annotated as political or non-political, revealing F1-scores above .82, except for the Netherlands (Appendix 2, Table 5). We decided to keep the Netherlands in the sample despite low classifier performance because of the high precision.

Third, these trained classifiers were used to categorize (a) those articles in sections labelled as “unclear,” and (b) articles of websites that did not have explicit political sections in their URLs. An overview flow chart of the full approach is presented in .

As we are interested in election campaign periods as well as a comparable routine periods, a 67-day time-interval around each country’s election day (spanning from 60 days before the election to 7 days following the election), as well as a comparable 67-day routine period were selected (except for the Netherlands, Appendix 1, Table 1). In the selection of the 67-day comparison period, we ensured that the election and routine period contained a comparable number of news articles, that it took place before major developments of the COVID-19 crisis, and that there was not another election taking place. For our analysis, we sampled only those articles falling within these two time periods, resulting in 265,714 articles.

Analytical Strategy

Our analytical strategy is split into three parts. First, we provide an account of journalistic interest in politics, by describing the fluctuation of the total number of articles dedicated to politics relative to all other news articles.

Second, to assess how election periods impact the sharing of political news, we compare the sharing of political news during election periods to routine periods. We do so using two measures: first, the percent of total shares that were given to political news, and, second, by estimating what percent of political articles produced during the period were shared at least once. As a robustness check, we also construct a series of negative binomial regression models (one per country), predicting the amount of shares a given article will receive based on whether the article is political or not, and whether it was published during an election (see Appendix 5).

Third, we create an explicit measurement of the news sharing gap. This measurement takes a single day as the unit of analysis and is a three-step calculation: (1) calculating the percent of political articles published on a given day; (2) calculating the percent of shares given to political news in that day; and (3) subtracting the percent of political shares from the percent of political articles. This provides a number between −1 and 1, where all positive values represent days where journalists had a stronger focus on politics than Facebook users, while negative values represent days when Facebook publics had more interest in politics than journalists. This results in a news sharing gap per day, per country, per period. We explore changes in the gap by assessing its fluctuation across country-periods, as well as empirically evaluating changes between political periods using t-tests.

Results

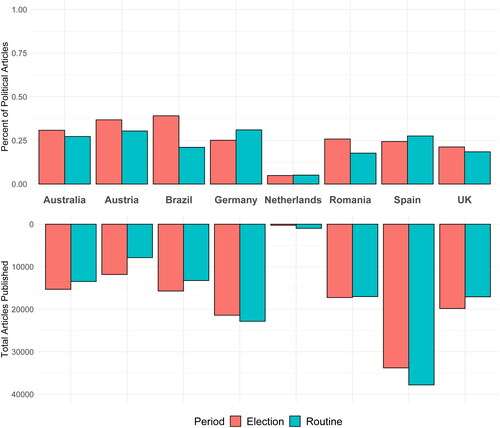

The Production of Political News

We begin by addressing the production of political news. We aim to understand to what extent the production of political news differs across time (routine vs. election periods) (RQ1) and countries (RQ3). The results are visualized in , with full descriptive statistics in Appendix 1, Table 2.

The top half of visualizes the percent of articles on the topic of politics, for both election and routine periods, while the bottom half visualizes the total number of articles available for each period. In five countries, the production of political news increased during election periods. This increase was quite small for three countries (Australia, Austria, and the United Kingdom +6%). The increase was somewhat larger for Romania (+8%) and Brazil (+18%). On the other hand, three countries witnessed a decrease in the share of political news (Germany −6%, Spain −3%, and the Netherlands −0.2%). Germany and the Netherlands are also the two countries in the sample with lower-level elections, with the Dutch provincial elections, and the European Parliament election in Germany. While the effects of elections on news production are not identical across different contexts, the shifts are not drastic: except for Brazil, all changes between political periods were below 8%. This speaks to the relative stability of political news publishing. Further to this point, we see that political news represents around 30% of news produced for most countries, across both periods. Exceptions are Brazil (39% for elections, 21% in the routine period), the United Kingdom (21%, 18%), and Romania in the routine period (18%). An extreme outlier here is the Netherlands with only 5.11% and 4.89% political news. This is likely a product of low recall.

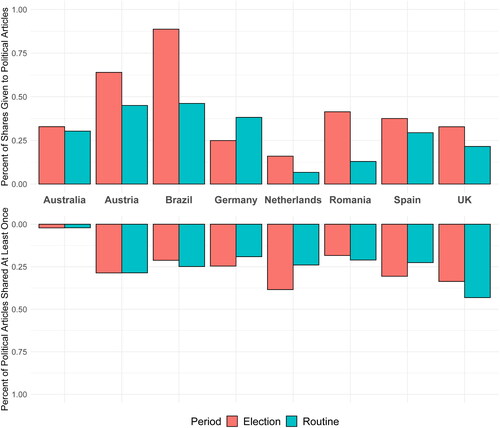

The Dissemination of Political News

We turn to the dissemination of political news (RQ2 and RQ4). The results are visualized in . The top row of shows what percent of news sharing was for political articles. Unlike political news publishing, which was relatively stable across both countries and time-periods, the sharing of political news in our sample varies drastically both across countries and time periods. Across countries, we see that political news represents as little as 7% of all news sharing in the Netherlands (routine period), and as much as 89% in Brazil (election period), with a lot of variation in between. This pattern stands in stark contrast to the cross-country stability present in political news publishing by journalists, where we consistently see that political news consistently represents around 30% of all articles published.

We now turn to changes across time periods, which also display much more variability than news publishing. The row of indicates that for seven countries, the dissemination of political news increases during the election period. For some, the difference is small (Australia +3%), but for most the change is substantial: the Netherlands +9%, Romania +29%, the United Kingdom +11%, Austria +19%, and Brazil +43% all increased their political news sharing by 9% or higher. While this follows the general pattern established for political news publishing—an increased focus on politics during elections—the rate of change is much higher for political news sharing.

Germany is the only country where we see a decrease in political news sharing (38% to 25%); however, it is also one of the countries which witnessed a decrease in relative political news production during elections. This points to a reduced interest in the political affairs taking place during the European Parliamentarian election by both journalists and Facebook users.

The bottom half of visualizes the percent of political news articles shared at least once. This analysis allows us to account for the influence that a handful of political articles “going viral” might have—at the aggregate level, one political article receiving tens of thousands of shares while the rest receive zero would make it seem like there is broad interest in political news, when there is not. By treating political articles on a binary “was shared or was not shared,” we can account for this. We observe that changes are not as strong in the bottom plot—overall, only around 25% of political articles were shared at least once, showing that during elections, we do not see an increase in the percent of articles shared. This tells us that even though not more political articles are shared, political articles represent a bigger portion of all the sharing taking place during elections. This means that the political articles that are shared received a much wider reach: increases in sharing during elections are due to specific political articles being shared more, and not more political articles being shared.

Lastly, as a robustness check, we modelled the effect of elections on political news sharing while controlling for the outlet-level effects and the attention given to politics in the week each article was published. Found in Appendix 5, the results generally confirm what is reported here, with election periods leading to drastic increases in political news sharing.

The News Sharing Gap

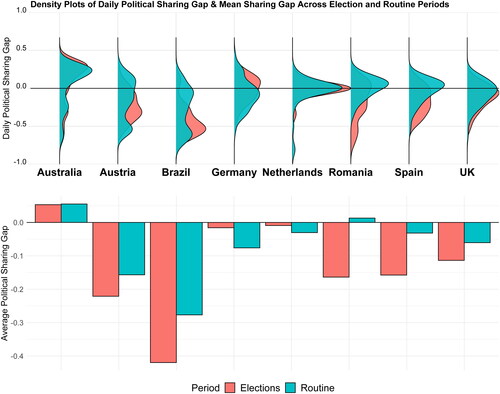

Finally, we address changes in the news sharing gap in response to RQ5. As the gap takes a single day as the unit of analysis, we can compute its concentration in density plots. We have done so in the top row of . The first observation we make is the spread distribution of the news sharing gap. Instead of converging around specific values across all countries, the news sharing gap is spread across numerous values throughout each period. It showcases how in some days, newspapers wrote up to 50% more about politics than people shared news about politics, while on others there was 90% more interest in sharing politics than there was news coverage. This spread distribution is the case for both routine and election periods. This speaks to an inherent fluctuation, where in no country we see that the gap is always favouring journalists or Facebook publics.

Figure 5. The news sharing gap across time and countries. Negative numbers indicate more sharing than publishing, while positive numbers indicate more publishing than sharing.

A second insight from is that in all (except three of 16 cases) the news sharing gap is either non-existent, or in most cases, negative. This suggests two things: First, in some cases, journalistic and publics’ interest in politics align quite well (the case for Germany and the Netherlands); second, that in most countries, Facebook publics were routinely more interested in sharing political news than journalists were in covering it. This is contrary to older accounts of diverging interest between journalists and readers, where journalists have been shown to over-emphasize political news. The evidence here suggests that across all countries in our sample (except Australia), Facebook publics are routinely as interested in political affairs as journalists, if not more so. Robustness checks using a more conservative estimation method confirmed results (Appendix 4).

A third main observation is that there is a pronounced shift in the size (and at times, direction) of the gap between election and routine periods: elections result in larger differences in political interest between Facebook publics and journalists. In most cases, the news sharing gap was larger during elections than during the routine period, with Facebook publics showing an even greater preference of political news.

To gauge whether these differences between election and routine periods are significantly different, we perform a series of t-test between the news sharing gap for each period within each country. These are reported in the bottom row of . Here, three countries (Brazil, Spain, Romania) see statistically significant changes (p < .001) in the news sharing gap, with the UK being significant at the p < .055 level. The biggest change comes from Romania, with a −.18 change in the news sharing gap, followed by Brazil (−.14), Spain (−.12), and the UK (−.05). Australia, Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands do not see any statistically significant changes from one period to the other. Austria witnessed an increase in interest by Facebook publics relative to journalists during elections (−.06). Interestingly, we observe the opposite pattern for Germany and the Netherlands, with Facebook publics being more interested in politics than journalists during routine periods as compared to elections. Lastly, while Germany follows the first pattern of a lower news sharing gap during elections, this country is the closest to completely not having a gap, both for routine and election periods.

Discussion

In the current study, we introduce the notion of the news sharing gap to conceptualize differences in interest in political news between journalists and publics on Facebook. To do so, we investigate changes between the news that users share on social media and the news published by news media organizations (a) across time (election vs. routine periods) and (b) across eight countries (Austria, Australia, Brazil, Germany, the Netherlands, Romania, Spain, and the United Kingdom). Using a sample of the useNews dataset (Puschmann and Haim Citation2020) consisting of 265,714 URLs shared over 12 million times on Facebook, this study adds to existing literature in two ways. First, by empirically exploring engagement with political news across periods of varying political activity in relation to the attention afforded by journalists. We show that the news sharing gap is mostly negative, with Facebook publics being more interested in sharing political news than journalists are in producing it, a relationship that is exacerbated during periods of elections. Second, we make a methodological contribution by providing a method for large-scale political news classification that allows for easier cross-country comparisons using distant supervision machine learning.

The results describe changes in political news publication during elections. Work on the journalistic coverage of politics during elections has argued that attention to politics increases during these key moments (Druckman Citation2005; Strömbäck Citation2005; Vliegenthart, Boomgaarden, and Boumans Citation2011; Zaller Citation2003). Here we find that the attention afforded by journalists to political news during elections varies significantly by country. In most cases, we do observe that elections are linked with a higher relative share of political news; however, we find that this change is more muted than normative accounts on the role of the press during elections suggest that it is. In our eight-country sample, we observe a range of change from routine to election periods—most countries witnessed increases in political coverage; in some, namely Romania and Brazil, this change was starker, while in others, the Netherlands, Spain and Germany, there was a decrease in relative news about politics. The picture painted by our results is one of stability rather than dynamism—there are little-to-no dramatic swings in the coverage of politics, with average political coverage being similar during elections and routine periods. Explanations for cases diverging from this pattern might lie in system-level variables: Brazil, with the biggest change between periods, stands out for its presidential political systems and lower professionalism in journalism, while Germany and the Netherlands, with the least change, both belong to the Democratic Corporatist media systems.

We also focus on political news sharing across countries and political periods. Here, there is much more variation in the amount of political news sharing from routine to election periods than there is variation in the publication of such. Elections have a strong influence on political news sharing, with these periods coinciding with spikes in the sharing of political news, supporting previous work in interest in political news sharing during elections (de León, Vermeer, and Trilling Citation2021; de León and Trilling Citation2021). This finding has consequences for our understanding of online public attention to elections: classical theories of public opinion, such as Zaller’s monitorial citizen (Zaller Citation2003), seem to be reflected in the sharing of political news on Facebook, with citizens becoming acutely engaged with politics in key periods. Nevertheless, we find that these increases in the sharing of political news are diverse and could be conditioned on country-level factors. Germany and the Netherlands, the countries with the least consequential elections in the sample, are also the countries where we see no significant change in political news sharing, for example.

Comparing the relative changes in publication and Facebook sharing patterns of political news we can address the overarching question of whether journalistic and Facebook user preferences diverge systematically in the form of a news sharing gap. Calculating the distance between journalist and sharing political interest, we explore how this gap varies along the lines of country and political periods. Previous work has signalled that a “news gap” exist between political news preferences between journalists and consumers, both in reading (Boczkowski and Mitchelstein Citation2012; Masullo, Jennings, and Stroud Citation2021) and sharing (de León, Trilling and Vermeer, Citation2021; Bright Citation2016) habits. The results presented here suggest that the news sharing gap follows quite different patterns, calling into question the extent to which traditional understanding of the news gap take place on sites such as Facebook. We find that in most countries, in both routine and election periods, the news sharing gap is negative, with Facebook audiences showing more interest in political news than media organizations. This stands in contrast with past accounts detailing how publics are less interested in “hard” news than journalists, both during routine times and elections (Boczkowski and Mitchelstein Citation2013), as well as during periods of crisis (Masullo, Jennings, and Stroud Citation2021). We also find that elections have a significant impact on the news sharing gap, increasing Facebook attention to political news at a speed that far outpaces its publication. This confirms what de Leon, Vermeer and Trilling (Citation2021) found previously, highlighting that audiences on Facebook are a lot more susceptible to large swings in topical attention than media organizations.

The fact that the gap is negative (with Facebook publics sharing more political news than journalists produce it) even during routine periods is a puzzling conclusion, considering past work showing journalists’ preference for political news, as well as the concerns over citizen disengagement with political reporting. We argue, however, that these results make sense once we reconceptualize political news sharing as a process that is distinct from other traditional forms of engagement that are usually measured through article clicks or self-reported interest. Here, the notion of virality plays a key role: with increasing polarization worldwide, it is easy for large scale indignation to spiral a political news article to an enormous audience as more people partake in the collective action of resharing news. Moreover, with the aggregate count of sharing, it is important to remember that mixed into these data are not only the shares awarded by common folk wishing to inform their group of friends of an issue they hold close at heart: these statistics also include redistribution by political actors themselves with massive following bases of like-minded partisans, as well as other actors (such as influencers, political commentators, and Facebook pages or governments themselves) with some vested interests in politics. Following this reasoning, we should understand that different actors have different weight on the Internet. While this might make sense for readership metrics, where one click on an article is the same regardless of who you are, this does not apply to news sharing. Instead, the relationship is closer to exponential: a share by someone with a large network of likeminded, politically interested people can generate much more consequent sharing than someone with only a couple of friends.

Lastly, we contribute to the field of digital journalism by showing how computational methods can be used to analyse and compare multilingual news content. To increase awareness of what computational methods have to offer, we use an automated content analysis approach and show how computational methods can aid journalism studies. More specifically, by using cues provided in the structure of news websites, we were able to classify political texts across eight countries and six different languages in an efficient and accurate manner.

Nonetheless, a few shortcomings should be noted. First, the CrowdTangle data provided in the useNews dataset only captures all shares of public posts. Therefore, our conclusions cannot be extended to include sharing of news articles directly by private profiles, or the sharing of news articles contained in a private post. Second, we have analysed a variety of elections (from presidential to provincial, and from federal to European)—a future avenue of research is to compare the same election types, in order to explore more specific case studies. Lastly, our results are influenced by our automated classifiers, as the crux of our empirical strategy hinges on the successful identification of political news. While we have taken numerous precautions to ensure that our classifiers perform at acceptable levels, it is nonetheless possible that miss-classification of articles plays a role in our final description and models.

appendix.pdf

Download PDF (371.2 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bennett, W. L., and S. Iyengar. 2008. “A New Era of Minimal Effects? The Changing Foundations of Political Communication.” Journal of Communication 58 (4): 707–731.

- Boczkowski, P. J., and E. Mitchelstein. 2012. “How Users Take Advantage of Different Forms of Interactivity on Online News Sites: Clicking, e-Mailing, and Commenting.” Human Communication Research 38 (1): 1–22..

- Boczkowski, P. J., and E. Mitchelstein. 2013. The News Gap: When the Information Preferences of the Media and the Public Diverge. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Boczkowski, P. J., E. Mitchelstein, and M. Walter. 2011. “Convergence across Divergence: Understanding the Gap in the Online News Choices of Journalists and Consumers in Western Europe and Latin America.” Communication Research 38 (3): 376–396.

- Boczkowski, P. J., and L. Peer. 2011. “The Choice Gap: The Divergent Online News Preferences of Journalists and Consumers.” Journal of Communication 61 (5): 857–876.

- Boyd, D. 2010. “Social Network Sites as Networked Publics: Affordances, Dynamics, and Implications.” In A Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network Sites, 47–66. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bradshaw, S., P. N. Howard, B. Kollanyi, and L.-M. Neudert. 2020. “Sourcing and Automation of Political News and Information over Social Media in the United States, 2016–2018.” Political Communication 37 (2): 173–193.

- Bright, J. 2016. “The Social News Gap: How News Reading and News Sharing Diverge.” Journal of Communication 66 (3): 343–365..

- Caldarelli, G., R. De Nicola, F. Del Vigna, M. Petrocchi, and F. Saracco. 2020. “The Role of Bot Squads in the Political Propaganda on Twitter.” Communications Physics 3 (1): 1–15.

- Choi, S. 2021. “News Gap in a Digital News Environment: Calibrating Editorial Importance from User-Rated News Quality and Identifying User Characteristics That Close the News Gap.” New Media & Society 23 (12): 3677–3701.

- de León, E., and D. Trilling. 2021. “A Sadness Bias in Political News Sharing? The Role of Discrete Emotions in the Engagement and Dissemination of Political News on Facebook.” Social Media + Society 7 (4): 20563051211059710.

- de León, E., Vermeer, S., & Trilling, D. (2021). “Electoral News Sharing: A Study of Changes in News Coverage and Facebook Sharing Behaviour During the 2018 Mexican Elections.” Information, Communication & Society. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2021.1994629

- dos Santos, M. A., Jr., D. Lycarião, and J. A. de Aquino. 2019. “The Virtuous Cycle of News Sharing on Facebook: Effects of Platform Affordances and Journalistic Routines on News Sharing.” New Media & Society 21 (2): 398–418.

- Druckman, J. N. 2005. “Media Matter: How Newspapers and Television News Cover Campaigns and Influence Voters.” Political Communication 22 (4): 463–481.

- Esser, F., and J. Strömbäck. 2013. “Comparing News on National Elections.” In The Handbook of Comparative Communication Research, 330–348. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Farkas, J., and M. Bastos. 2018. “Ira Propaganda on Twitter: Stoking Antagonism and Tweeting Local News.” Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Social Media and Society, 281–285.

- Feezell, J. T. 2018. “Agenda Setting through Social Media: The Importance of Incidental News Exposure and Social Filtering in the Digital Era.” Political Research Quarterly 71 (2): 482–494.

- Fishman, M. 1980. Manufacturing the News. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Flaxman, S., S. Goel, and J. M. Rao. 2016. “Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Online News Consumption.” Public Opinion Quarterly 80 (S1): 298–320.

- Gerlitz, C., and A. Helmond. 2013. “The like Economy: Social Buttons and the Data-Intensive Web.” New Media & Society 15 (8): 1348–1365.

- Go, A., R. Bhayani, and L. Huang. 2009. “Twitter Sentiment Classification Using Distant Supervision.” CS224N Project Report, Stanford 1 (12): 2009.

- Guess, A. M. 2021. “(Almost) Everything in Moderation: New Evidence on Americans’ Online Media Diets.” American Journal of Political Science 65 (4): 1007–1022.

- Hiaeshutter-Rice, D., and B. E. Weeks. 2021. “Understanding Audience Engagement with Mainstream and Alternative News Posts on Facebook.” Digital Journalism 9 (5): 1–30.

- Howard, P. N., G. Bolsover, B. Kollanyi, S. Bradshaw, and L.-M. Neudert. 2017. Junk News and Bots during the US Election: What Were Michigan Voters Sharing over Twitter. Oxford, UK: Computational Propaganda.

- Kaid, L. L., and J. Strömbäck. 2009. “Election News Coverage around the World: A Comparative Perspective.” In The Handbook of Election News Coverage around the World, 441–452. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Karnowski, V., L. Leonhard, and A. S. Kümpel. 2018. “Why Users Share the News: A Theory of Reasoned Action-Based Study on the Antecedents of News-Sharing Behavior.” Communication Research Reports 35 (2): 91–100..

- Kümpel, A. S., V. Karnowski, and T. Keyling. 2015. “News Sharing in Social Media: A Review of Current Research on News Sharing Users, Content, and Networks.” Social Media + Society 1 (2): 205630511561014..

- Masullo, G. M., J. Jennings, and N. J. Stroud. 2021. “‘Crisis Coverage Gap’: The Divide between Public Interest and Local News’ Facebook Posts about COVID-19 in the United States.” Digital Journalism: 1–22.

- McQuail, D. 1987. Mass Communication Theory: An Introduction. London: SAGE.

- Meijer, I. C. 2020. “Understanding the Audience Turn in Journalism: From Quality Discourse to Innovation Discourse as Anchoring Practices 1995–2020.” Journalism Studies 21 (16): 2326–2342..

- Merrill, J. C. 2009. “Introduction to Global Western Journalism Theory.” In Global Journalism: Topical Issues and Media Systems, edited by A. de Beer, 3–21. Pearson.

- Mosleh, M., G. Pennycook, and D. G. Rand. 2020. “Self-Reported Willingness to Share Political News Articles in Online Surveys Correlates with Actual Sharing on Twitter.” PLoS One 15 (2): e0228882.

- Murray, S. 2005. “Brand Loyalties: Rethinking Content within Global Corporate Media.” Media, Culture & Society 27 (3): 415–435.

- Nelson, J. L., and J. G. Webster. 2017. “The Myth of Partisan Selective Exposure: A Portrait of the Online Political News Audience.” Social Media + Society 3 (3).

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Schulz, S. Andı, and R. K. Nielsen. 2020. “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020.” Technical Report.

- Nielsen, J. H., and M. N. Franklin. 2016. Eurosceptic 2014 European Parliament Elections: Second Order or Second Rate?. London: Springer.

- Norman, D. A. 1988. The Psychology of Everyday Things. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Ørmen, J. 2019. “From Consumer Demand to User Engagement: Comparing the Popularity and Virality of Election Coverage on the Internet.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 24 (1): 49–68..

- Osmundsen, M., A. Bor, P. B. Vahlstrup, A. Bechmann, and M. B. Petersen. 2020. “Partisan Polarization is the Primary Psychological Motivation behind ‘Fake News’ Sharing on Twitter.”

- Prior, M. 2007. Post-Broadcast Democracy: How Media Choice Increases Inequality in Political Involvement and Polarizes Elections. Cambridge University Press.

- Puschmann, C, and M. Haim. 2020. UseNews..

- Qiu, X., D. F. Oliveira, A. S. Shirazi, A. Flammini, and F. Menczer. 2017. “Limited Individual Attention and Online Virality of Low-Quality Information.” Nature Human Behaviour 1 (7): 1–7.

- Reif, K., and H. Schmitt. 1980. “Nine Second-Order National Elections – A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results.” European Journal of Political Research 8 (1): 3–44.

- Santini, R. M., D. Salles, G. Tucci, F. Ferreira, and F. Grael. 2020. “Making up Audience: Media Bots and the Falsification of the Public Sphere.” Communication Studies 71 (3): 466–487.

- Shao, C., G. L. Ciampaglia, O. Varol, K.-C. Yang, A. Flammini, and F. Menczer. 2018. “The Spread of Low-Credibility Content by Social Bots.” Nature Communications 9 (1): 1–9.

- Shoemaker, P. J., and A. A. Cohen. 2006. News around the World: Content, Practitioners, and the Public. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Strömbäck, J. 2005. “In Search of a Standard: Four Models of Democracy and Their Normative Implications for Journalism.” Journalism Studies 6 (3): 331–345..

- Sturm Wilkerson, H., M. J. Riedl, and K. N. Whipple. 2021. “Affective Affordances: Exploring Facebook Reactions as Emotional Responses to Hyperpartisan Political News.” Digital Journalism 9 (8): 1040–1061.

- Swanson, D. 2004. “Transnational Trends in Political Communication: Conventional Views and New Realities.” In Comparing Political Communication. Theories, Cases, and Challenges, edited by F. Esser and B. Pfetsch, 45–63. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thorson, K., K. Cotter, M. Medeiros, and C. Pak. 2021. “Algorithmic Inference, Political Interest, and Exposure to News and Politics on Facebook.” Information, Communication & Society 24 (2): 183–200.

- Thorson, K., and C. Wells. 2016. “Curated Flows: A Framework for Mapping Media Exposure in the Digital Age.” Communication Theory 26 (3): 309–328.

- Trilling, D., J. Kulshrestha, C. de Vreese, D. Halagiera, J. Jakubowski, J. Moller, C. Puschmann, A. Stepinska, S. Stier, and C. Vaccari. 2022. “Is Sharing Just a Function of Viewing? Predictors of Sharing Political and Non-Political News on Facebook.” Journal of Quantitative Description: Digital Media 2. doi:10.31235/osf.io/am23n.

- Twitter. 2020. “Sharing an Article Can Spark Conversation, so You May Want to Read It before You Tweet It. [Excerpt from Tweet].”

- van Aelst, P., and K. de Swert. 2009. “Politics in the News: Do Campaigns Matter? A Comparison of Political News during Election Periods and Routine Periods in Flanders (Belgium).” Communications 34 (2): 149–168.

- van Aelst, P., J. Strömbäck, T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. de Vreese, J. Matthes, D. Hopmann, et al. 2017. “Political Communication in a High-Choice Media Environment: A Challenge for Democracy?” Annals of the International Communication Association 41 (1): 3–27.

- Vliegenthart, R., H. G. Boomgaarden, and J. W. Boumans. 2011. “Changes in Political News Coverage: Personalization, Conflict and Negativity in British and Dutch Newspapers.” In Political Communication in Postmodern Democracy, 92–110. Springer.

- Wadbring, I., and S. Odmark. 2016. “Going Viral: News Sharing and Shared News in Social Media.” Observatorio (OBS*) 10 (4): 132–149.

- Weeks, B. E., and R. L. Holbert. 2013. “Predicting Dissemination of News Content in Social Media: A Focus on Reception, Friending, and Partisanship.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 90 (2): 212–232.

- Weeks, B. E., D. S. Lane, D. H. Kim, S. S. Lee, and N. Kwak. 2017. “Incidental Exposure, Selective Exposure, and Political Information Sharing: Integrating Online Exposure Patterns and Expression on Social Media.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 22 (6): 363–379..

- Woolley, S. C., and P. Howard. 2017. “Computational Propaganda Worldwide: Executive Summary.”

- Zaller, J. 2003. “A New Standard of News Quality: Burglar Alarms for the Monitorial Citizen.” Political Communication 20 (2): 109–130..