Abstract

As data are becoming increasingly central to journalistic practice, a number of technology-driven approaches are emerging among data journalists. This article focuses on sensor journalism, which brings new practical and ethical concerns to journalism. By interviewing and working with data journalists and journalism scholars, we analyze the new technological and ethical challenges that sensors bring to journalism. The results contribute to the knowledge on how data journalists implicitly embed ethical values into their everyday work. Furthermore, they suggest that general ethical values are revisited and extended by the influence of sensors.

Introduction

For journalism practice, data are increasingly central. Data scientists, information designers and developers are becoming part of newsrooms, and reporters have come to value an open-source culture for its creative, accessible and transparent nature (Coddington Citation2015). New types of journalism linked to a particular technology or data-led approach, such as “algorithm journalism” or “augmented journalism,” are increasingly emerging as new figures and practices enter the newsroom (Loosen et al. Citation2022). Similarly, research describes sensor journalism as the journalistic practice of investigating stories by using devices capable of detecting and responding to some type of input from the physical environment (Schmitz Weiss Citation2016). It is a type of investigative journalism where reporters test their hypotheses against data collected through technical devices known as sensors (Pitt Citation2014, 10–12). Sensors provide data, the raw material for sensor journalism to happen (ibid.). More precisely, Bui (Citation2014) defines sensors as open-ended, low-budget technical devices capable of collecting environmental, personal and local data, with potential for new stories and areas of reporting (Moradi 2011). In the last decade, sensors have become increasingly popular among data journalists because of the sensors’ accessibility, and not only in terms of price. Reporters can access existing networks of sensors with varying degrees of freedom (Pitt Citation2014, 9), and journalists, often competing for fresh data to include in their stories (ibid.), are increasingly adopting them to cover a variety of topics. So far, journalists have used sensors to investigate environmental and health-related issues such as air quality, viral spreads, water and soil pollution (Moradi and Howard Citation2013). Personal and body-related data — collected, for example, through wearables such as fitness bracelets or phones — are also increasingly used by journalists used to author journalistic stories. This special category of sensors can be attached to various parts of the body and is capable of tracking different aspects, including movement in space, heart rate variations, and skin conductivity (Choe et al. Citation2014). Some major news outlets have published stories on topics such as protests (Bailey et al. Citation2020), private and collective commuting experiences (Tagesspiegel Wittlich et al. Citation2018), data breaches in major institutions (Hern Citation2018) or the development of data-based counter narratives (Tesla Citation2013). These types of stories make use of private and personal data in unprecedented ways by displaying one or more feeds of data collected by and belonging to individuals. Although a promising direction for data journalists, personal-sensor data challenge traditional ethical values (Howard Citation2013) and professional norms of journalism (Caswell Citation2019; Hepp and Loosen Citation2021); Schmitz Weiss Citation2016). Building on previous research, we denote the following ethical values as central for the study: reliability, verification, transparency, privacy, and source protection. Inspired by Rao and Lee (Citation2005), we discuss them together with the study’s participants through ethical considerations such as respect for others, tolerance for diversity, restrained truth-telling, freedom and independence, and privacy (Rao and Lee Citation2005).

Technologies (e.g., algorithms), and more generally datafication, have been scrutinized in previous research (see, for example, Dörr and Hollnbuchner Citation2017; Appelgren Citation2018; Anderson and Borges-Rey Citation2019; Porlezza and Eberwein Citation2022). Similarly, sensors have been scrutinized for how they impact journalism, from both a technological and an ethical perspective (Pitt Citation2014). However, it remains unclear how journalists deal in their day-to-day work with ethical concerns connected to sensing — especially when it comes to embodied sensing. Embodied sensing directly involves the sources of data (humans and their bodies) as active participants in the collection efforts, and self-tracking devices require bodies to collect data. This aspect challenges some central ethical rules of data journalism, leaving reporters to renegotiate them in order to properly carry out their work. For this reason, we decided to focus on embodied sensing. More in general, observing journalists working with sensors to freshly collect compelling data makes it an interesting case for analyzing how technologies shape and are shaped by journalists’ formal and informal ethical codes of conduct. As Diakopoulos (Citation2019) similarly argues on algorithms, the particular type of data collected through embodied sensing and their role within news-making should concern both journalists and scholars as this intersection between bodies, data, technology and journalism consistently shapes and impacts professional and ethical boundaries of the latter. The risk of underestimating how technologies impact a professional activity such as data journalism lies in the gradual shift toward a technically driven practice (Agre 1997), where choices are made and evaluated against the technology itself rather than human values (Friedman Citation1996).

This study aims to analyze ethical values embedded and shared by reporters when working with embodied sensing, and it contributes a compelling landscape of formal and informal rules, methods and ideas on how sensor journalism is carried out on a daily basis within newsrooms. Drawing on Value-Sensitive Design — a theory-based framework to critically assess how technological artifacts and practices should be designed according to central human values (Friedman Citation1996; Friedman and Kahn Citation2007) — we conducted a series of workshops and interviews with data journalists and scholars. We considered both professionals and researchers since these individuals can be considered parts of institutions that concur in forming “public subjects” (journalists and a broader citizenry) through the production of collective ethical norms (Nolan Citation2006). The article analyzes the conversations with these experts and contributes fundamental ethical considerations on using sensors in journalism with the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1. How do journalists apprehend and apply ethical values when working with sensors?

RQ2. What are existing and emerging ethical considerations for sensor technology in journalism?

Personal Data in Journalism

Self-tracking and personal analytics are well-recognized activities among the general public, activists, health enthusiasts and scientists (Choe et al. Citation2014). Collecting and using personal information as grounds for news-making is not new to either traditional reporting or data journalism. Social media is for example used to conduct research and obtain personal or private information on individuals, including pictures, names, interests or entire textual statements (Santana and Hopp Citation2016). Another example is journalistic interviews where journalists, with the help of focused questions, bring personal information and individuals to the center of their stories (Ekström, Kroon, and Nylund Citation2006). Interviews are one of the core practices for reporters and are thoroughly normed, especially given their sensible focus: individuals. Previous research has also found that the interview’s setting allows journalists to catch sources by surprise or persuade them to participate (Bakker et al.; 2013), and interviewees gradually turn over control of their stories to journalists while still remaining accountable to the public for how they are told (Palmer Citation2018). In an increasingly datafied society, interviews could also be subject to datafication, especially through personal sensing and individual tracking devices.

Ethical Values and Ethical Codes of Conduct

Kovach and Rosentiel (Citation2021) explain that ethics are woven into every element of journalism and every critical decision that journalists make (p. 273). Regarding data journalism, a transversal discipline where journalists turn to data and manipulate them through computational, statistical and design skills (Thurman Citation2019), data journalists have negotiated additional ethical standards within the data journalism community. This is partly because using data to provide depth to a story can bring about ethical problems, such as fear of consequences that can prompt a backlash against its use, problems of verifying public data sets and risks (actual or feared) of invasion of privacy (Craig, Ketterer, and Yousuf Citation2017). Furthermore, Dörr and Hollnbuchner (Citation2017) emphasize that the origin of data also relates to ethical values, such as reliability (accuracy), objectivity, responsibility, respect for privacy, methods of data collection, bias, data rights (data authority) and economic aims. Specifically for data journalists, ethics revolve around how data are collected, analyzed and presented. Bradshaw (Citation2014) argues that the context around the data introduces various uncertainties. For example, reporting on errors in public data and considering how to describe a data set, such as the origin and sampling or processing method. Additionally, data journalism often invites users to actively manipulate the product (Boyles and Meyer Citation2016) with interactive features, and by individual address (Widholm and Appelgren 2021). Boyles and Meyer (Citation2016) argue that data journalists take on the role of explainers of societal knowledge through making data conversational, yet keeping track of the story and not getting too distracted by the design elements of newswork. Despite these efforts, the ethical professional practice of data journalism is still relatively behind, as projects often present various shortcomings, especially in regard to privacy and transparency (Chaparro-Domínguez and Díaz-Campo Citation2021).

From a normative point of view, national and company-specific codes of ethics seldom contain references to specific technologies such as sensors. All codes of conduct agree on foundational aspects of journalism: striving to report the truth, minimizing harm, and being honest, transparent and fair (Society of Professional Journalists (US) Citation2014; NUJ, 2011). For example, the Swedish code of conduct — and other countries’ equivalent codes — specifies how to behave when interviewing, e.g., showing consideration to inexperienced interviewees and carefulness with social media content of non-public figures (Journalistförbundet Citation2020). Codes of conduct rarely include detailed criteria on how to work with personal and body-related data. As an exception, the Finnish code comes with an annex focused on user-generated content. Created in 2011, this annex calls on journalists to monitor user-generated content on media websites to avoid going public with content that harms human dignity (The Union of Journalists in Finland Citation2014). The German code of ethics also mentions the importance of preserving human dignity. In particular, this code states that reports on medical matters should not be of an unnecessarily sensationalist nature, and the location of people’s private addresses should enjoy special protection (Deutscher Presserat Citation2019).

Because codes of conduct do not specifically address the ethical challenges of using data, to sustain, repair and extend standards in data journalism, previous research has found that the data journalism community has discussed ethical issues online in specific forums for data journalists, such as NICAR-L (Craig, Ketterer, and Yousuf Citation2017), or dedicated Facebook groups where digital forums provide a space for this sub group of journalists to exchange knowledge (Appelgren Citation2016). Craig, Ketterer, and Yousuf (Citation2017) argue that these discussion forums function as moral communities, contributing to the practice’s development. In these forums, Craig, Ketterer, and Yousuf (Citation2017) found that the discourse involved members sanctioning those who violated standards regarding ethical values. The social community of data journalists have not yet however formulated explicit agreed-upon values in terms of ethics. In forums where data journalists discuss the profession alongside academics, such as the Data Journalism Handbook (Gray, Chambers, and Bounegru Citation2012; Bounegru and Gray Citation2021) ethics are by data journalists themselves described as central, yet not much different from general professional ethics for journalists, apart from the privacy of individuals specific to data.

From Journalism to Design: Understanding Technological Influences

Sensors in Journalism

According to Howard (Citation2013), sensors have been used to inform a variety of journalistic stories, especially when centered around environmental issues such as air or water quality. Similarly, Bui (Citation2014) defines an even broader landscape of possibilities for sensor journalism, such as data donation and personal sensing. By providing health and body-related data, citizens could support and inform stories on a variety of topics such as environmental wealth or stress. However, as noted by Pitt (Citation2014), the field of sensor journalism is still young, and practitioners, while conscious in treating and working with this kind of data, still have to deal with ethical challenges. In this regard, Schmitz Weiss (Citation2016), building on previous literature (Howard and Moradi 2013), openly questions the ethical side of these practices: “… there are several key questions a journalist must think about before starting a project: Who is going to collect the sensor data? Where will the sensor data be stored? What is the strategy for protecting the identities of those who are collecting the sensor data? What data is the sensor going to collect? How long will the sensors be deployed? How will the sensor data be presented? Each of these questions entails careful thought as to how the sensor is managed and is used” (p. 1056). German journalists Wittlich, Lehmann, and Vicari (Citation2019) drafted a written statement to define policies and goals —a manifesto — for sensor journalism with a clear focus on its ethical and practical boundaries. Specifically, the authors discuss how sensors are “[…] changing how we see the world and what information is collected about us. […] this development will have long-term consequences for society, the environment and the distribution of power.”

Technologies in Journalism

Several scholars have investigated technologies’ influence over journalism by drawing from various other domains. Primo and Zago (Citation2015) found that technologies are actively shaping journalism by influencing its practices and structure (ibid.). Similarly, Steen et al. (Citation2019) survey the strong influence of science and technology studies (STS) on journalism studies literature as well as the impact of broader frameworks, such as actor-network theory (ANT) (Latour Citation1992), in understanding the mutual shaping between technologies and journalism. Overall, new digital practices are not easily imported into news organizations (Appelgren and Nygren Citation2019). Ferrucci and Perreault (Citation2021, 1445) suggest three factors that make technological innovation particularly difficult in journalism: strong professional cultures; lack of training; and a practice of pushing back technologies because of a belief that they do not contribute to better journalism. Nevertheless, newsrooms still adopt new practices, and in such processes, certain journalists act as intermediaries of change, contributing to a gradual normalization by incorporating pioneering practices into existing organizational structures and routines (Heft and Baack Citation2021). Similarly, Molyneux and Mourão (Citation2019) state that journalists tend to map existing norms onto new technologies; however, as technology has developed and journalists have become more accustomed to technology, it has become part of their routines and as such normalized.

Technologies in Design

A few studies in journalism have used an HCI tradition. One prominent example is Anderson and Borges-Rey (Citation2019), who drew on the design and HCI tradition to combine qualitative and quantitative methods to untangle data journalism. However, outside of journalism studies, design theory has a long history of contributing to the discussion on how technologies, existing methodologies and practitioners influence each other (for example, see Bardzell Citation2010; Agre 1997). Sengers et al. (Citation2005) argues that technologies — regardless of the field they enter — should always be discussed and formalized according to how they impact explicit and implicit values. This resonates with Friedman’s (Citation1996) Value-Sensitive Design (VSD) framework. VSD is “a theoretically grounded approach to the design of technology that accounts for human values in a principled and comprehensive manner throughout the design process” (Friedman Citation1996), and it is often leveraged before starting the actual design process of computer systems and technologies. At the core of VSD lies the concept that technologies widely impact human lives and therefore need to be designed through human values (Friedman and Kahn Citation2007). This perspective allows for formal and informal decisions to emerge in relation to particular human values. Friedman, Kahn, and Borning (Citation2008) are doing so by iteratively thinking, discussing and designing technological products in three distinct phases: conceptual, empirical and technical investigations (ibid.). Conceptual investigations serve the purpose of exploring values and defining which are central to designing the technology at hand (ibid.). Conceptual investigations are designed to survey fundamental stakeholders and their values to determine friction points and complex aspects of technologies within their context. Conceptual investigations do not require costly empirical work; they can be carried out speculatively by scholars and designers (Friedman, Kahn, and Borning Citation2002). Empirical investigations specifically expand on questions generated by observing technologies’ context: they bring values into perspective by studying where the technological artifact is situated socially and culturally. In this phase, scholars can use quantitative and qualitative methods from social science research to document how stakeholders interact with technologies and their context (Friedman, Kahn, and Borning Citation2002; Friedman, Kahn, and Borning Citation2008). Lastly, technical investigations focus on existing technologies’ properties and how they hinder or favor certain values by design (Friedman, Kahn, and Borning Citation2008). While this framework is usually applied in the process of creating technologies, we use it in this study to unravel sensor journalism’s ethical considerations.

Approach

This study centers around the empirical investigation of personal sensing — as in using bodily sensors to collect personal data from consenting individuals — and builds on previously cited work that strived to conceptualize values, concerns and possibilities connected with sensors as a technology for data collection (Schmitz Weiss Citation2016; Kuznetsov et al. Citation2011; Morini et al. Citation2021). We asked the data journalists to speculate about the journalistic genre of interviews and imagine how sensors could change this common journalistic practice. VSD was used to assess how personal sensing potentially shapes interviews both ethically and practically, exploring more in depth and from different angles the day-to-day practices connected with sensing. In this sense, VSD helps in incrementally building constructing technologies: its modular structure allows planning for clear and purposeful steps.

Methodology

This study focuses on a western European context, and its structure is a combination of in-depth interviews and workshops with eleven key informants. The decision to focus on western Europe was out of convenience due to the authors’ familiarity with formal and informal codes of ethics and journalistic practices. We selected key informants based on their knowledge of the topics at hand: data journalism’s production cycles, sensor technology and ethical codes of conduct, whether pan-European or country-specific. In total, we asked seven data journalists working in the European countries Sweden, Germany, Italy, Finland and Switzerland to participate in this research. Nolan (Citation2006) states that journalism production and universities parallel one another, both being part of how norms and ethical values are formed. Furthermore, society can influence the development of journalism through education (Curran Citation2005), and therefore we also added interviews with four journalism scholars active in Norway, United Kingdom, Italy, Switzerland and Sweden. The two samples of journalists and scholars thus covered different roles: from freelance reporters (J1, J3), junior and senior journalists belonging to major news outlets (J2, J4), designers with previous experience in academia (J6), editors and editorial managers (J5, J7), and journalism scholars working in universities experienced in new technologies (S2, S4), traditional and innovative code of ethics (S1), and journalistic practices (S3). One scholar-participant (S3) has direct experience as a former reporter in her country.

We kept the empirical and conceptual investigations separate. We structured the in-depth interviews (Mears Citation2012) to survey compelling ethical values central to data journalism and more specifically sensing; later, small groups or individual hands-on exercises structured similarly to workshops (Rosner et al. Citation2016) served to conceptually explore the news value of sensor data and their impact on the reporters’ daily course of action. Both activities revolved around sensor journalism by focusing on practical strategies and reflexive exercises. We did not mix the groups of journalists and scholars, and they underwent similar yet different treatments: during interviews, journalists were asked about both their practical strategies in working with sensors and their opinion on which ethical values are central to this type of journalism, while scholars were only asked about the latter. Additionally, scholars did not take part in the follow-up conceptual investigation, which we constructed entirely around journalistic practice.

Interviews consisted of sixteen questions, starting with the journalistic interview as a genre and how sensors could be used to complement it. The final aim of this activity was to determine whether key ethical values of data journalism would inherently apply to sensor journalism as well. Therefore, we explicitly asked informants to speculate about ethics in relation to a specific genre. The choice of the term “speculation” is not casual here; it is central to critical design practice as a way of using imagination to open up new perspectives and create space for discussion (Dunne and Raby Citation2013). The initial questions were inspired by previous work on sensor-enhanced interviews and the possibility of using personal data as representations for humans in the journalistic context (Morini et al. Citation2021). Building on a study of traditional journalistic interviews by Bakker et al. (Citation2013), we asked participants to speculate how they would both prepare for a sensor interview and devise stories centered around personal data. For the interviews with scholars, we omitted the questions that focused exclusively on production practices. The central part of the interview was structured around a series of central ethical values emerging from Rao and Lee (Citation2005): respect for others, tolerance for diversity, restrained truth-telling, freedom and independence, and privacy. The questions openly focused on each of these values by challenging informants to discuss the values in relation to sensor technology and data. The last part of the interview focused on how data journalists interact with and use their formal and informal codes of ethics in everyday work routines.

By combining exercises with in-depth interviews, we were able to mutually engage social actors, shifting from “doing” to “knowing,” and focus first on a situated inquiry and then on a more sui generis reflection of ethical aspects (Rosner et al. Citation2016). The exercises fostered an open dialogue between participants and were carried out either in groups or pairs, with a maximum of three participants per group. During this activity, ethical values were not explicitly teased out, participants were asked to reason on three aspects: stories, audience, and practice. All three activities were consistent in terms of tools, structure, and moderation. The exercises took place online on the Web platform Miro, a collaborative tool for design thinking and brainstorming. The participants and authors connected via Zoom, a software for live conference calls. Informants were asked to think about sensor interviews and possible news angles and to put forward as many ideas as they could by reflecting on existing stories or devising entirely new ones. They were then asked to assign each story a category and a possible sensor. Participants had to assign story ideas a category (e.g., health, environment, culture, society) and a sensor that could monitor one or more parameters (e.g., proximity, heart rate, skin connectivity). Next, participants were asked to select a single story-pitch and define its potential audience by trying to describe who could read such stories and why they would be interested. Using empathy boards (Ferreira et al. Citation2015), journalists brought forward thoughts and impressions about their ideal readers. Finally, informants were asked to review their work and reflect on how sensors could either positively or negatively impact their everyday journalistic methods. By writing single aspects on separate Post-it notes, they were then asked to position them on a scale going from “negative impact” to “positive impact.”

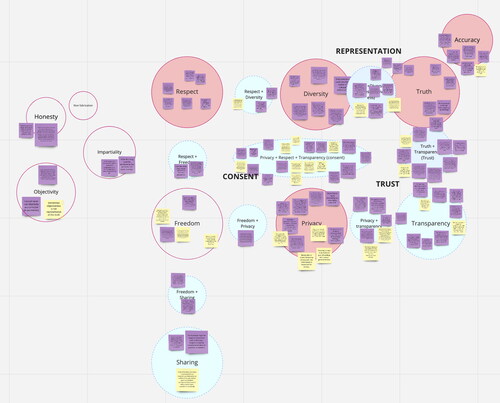

The analysis of the results were done with an inductive approach followed by affinity diagramming on isolated statements. Some initial categories and topics were extracted after transcribing and organizing the material. This initial categorization operated on the discursive meta-level of the transcriptions: great importance was given to the type of expressions (critiques, beliefs, opinions, etc.). Next, single statements were isolated and rearranged according to content. Statements were clustered around specific ethical values to visually define their prominence in the discourse, as in the example visible in . We arranged other statements that focused on data journalists’ community and production cycles separately, and we kept scholars’ and journalists’ statements visually distinct from each other to emphasize similarities and differences between the two groups. We also visually clustered and thematized the results of the workshops to explore sensor technology’s influence on journalists’ practice.

Figure 1. Raw excerpts from the in-depth interviews were imported into Miro. Each statement was copied onto a single note and arranged according to its content. Violet notes are from journalists, and yellow notes are from scholars. Red clusters signal ethical values that were explicitly identified through questions, while light blue clusters were added spontaneously by informants.

Results

In total, 298 individual statements were isolated and analyzed from transcriptions: 225 from journalists and 73 from scholars. Fifty-five of them originated from the workshops, and the remaining 243 were extracted from the in-depth interviews. Empirical findings concern both data journalists’ professional context when working with sensors and their ethical and practical influence on data journalism. During the workshops, journalists demonstrated how sensors widen the range of possible news stories. They speculated on how to possibly record climate change’s impact on humans (J2, J3, J6), how to measure physical reactions of political debates and protests (J1, J4), and how to monitor non-human bodies, for instance by following cats’ movements at night (J5) or measuring cows’ health in intensive breeding (J7). There was no unique strategy for working with sensors, and journalists’ individual skills and technological knowledge played a fundamental role in creating devices and designing stories. In-depth interviews partially confirmed these aspects: journalists described the community of data journalists as independent from traditional reporters and much more focused on experimenting with new technologies with limited interest in formalizing their practices and codes of conduct. However, when explicitly questioned on particular ethical values, journalists provided rich answers, referencing on multiple occasions their everyday practice, possible pitfalls and perks related to adopting this technology.

Tensions between Tradition and Innovation

“Even if I come from the data side, I am still making journalism.” With this brief statement, J3 summarized how all interviewed data journalists understood their work as being both tied and detached from traditional reporting. Interviewees were well aware of how traditional journalism provides them with a solid ground: they are often associated with or part of established newsrooms that make their work possible and provide them with resources, tools and ethical guidelines. However, they are also aware of how their practice differs from traditional journalism since they use different sources, often data sets that need to be discovered, extracted and verified. Procedural differences are often related to the usage of technologies and computational methods. Technology was key to this approach since it influences the data that could be collected, why and how. When asked how they would prepare to work with sensors for an interview, reporters described their process as different. They focused on other aspects, leaving the technology to fill the gaps:

I would use a data journalistic approach rather than a traditional one. I would be less concentrated on what is collected through the sensor. I would write what someone says, details and so on. I would use time and location as structural elements and, given the fact that the sensors are probably recording those, I would be less attentive to note down location or other parameters. (J7)

Sensors could influence storytelling techniques either positively or negatively. Journalists discussed how sensors could be useful to “add visual descriptions to scenes” (J6) or enhance “the ideation process by giving us the freedom to create our data” (J7). However, journalists also viewed sensors as an “awkward icebreaker that can hinder journalists’ chances of interviewing someone” (J1). Interestingly, sensors also influenced journalists’ conduct. According to participants, sensor data allowed for more transparency and closeness with the reader. At the same time, this transparency contained a negative aspect in that it forces journalists to strengthen their technological skills in order to protect interviewees’ privacy and motivate their work inside the newsroom (J7). This community appears to be shaped by the idea of technology as a driver for their work, putting them in discontinuity with traditional journalists (J3). Scholars described journalists as having “some self-established rules” (S2) that are directly influenced by their work. “However, up to a certain point, this is also a self-marketing strategy of data journalists […]” (S2).

Ethical Considerations as Practical Issues

The close relationship with technology influenced journalists regarding ethical values and their relationship with traditional codes of conduct throughout interviews and workshops. The interviewed scholars described how some journalists were seen as activists that center their practice around data: “Part of their goal is to establish widespread data practice where data is open, available to everybody” (S3). When it comes to transparency and open access in particular, “data journalists live to these rules of transparency from the beginning unlike many other journalists” (S2).

Journalists themselves were aware of their active role in establishing emerging practices:

[We] have done more than other kinds of journalists. We are often thinking about transparency, trustworthiness and accountability. I think it’s a kind of journalistic approach where those issues are clearer than in other approaches. Especially on the transparency side and data literacy — making it easy also to replicate methodologies — data journalism is very advanced. (J2)

Considering Ethics When Using Sensor Data

Interviewed journalists elaborated on ethics in relation to sensors by expanding existing values and making new cardinal values emerge. Journalists also considered ethics to avoid negative repercussions on individuals that wear bodily sensors and discussed ethical values in relation to how data journalists need to explain their intentions, methodologies and tools to people involved.

Privacy

Interviewees viewed privacy as central to sensor journalism, especially if individuals take part in the data collection as in the case of personal sensing or sensor-enhanced interviews. As J2 explains: “I would expect that thinking about privacy issues enables you to carry out work based on sensors. You have to be clear on boundaries and outcomes to get people to trust you and give you the data in the first place.” As individuals are increasingly concerned about privacy issues, resolving privacy concerns effectively “would be the greatest challenge in involving [participants]” (J1). The definition of privacy shifted away from the traditional definition to accommodate sensors. “Once you start using sensor-based digital storytelling, you are converting your passive subject into an active participant” (S5); hence, privacy becomes closely connected to consent.

Transparency

Both journalists and scholars remarked on how transparency is fundamental for data journalists: they asserted that they were not reluctant to publicly reveal their production process to participants, readers and even other journalists. This also holds true for sensor journalism. Journalists believe in being clear and rigorous in documenting their work:

I would personally approach the problem from a story point of view. I would explain what we are trying to accomplish with this story and then why we are doing this and why we are asking you these questions using sensors. I would motivate the person from the goal point of view, then we would share a goal. Then, I would move to technical details, explaining what we are going to do in terms of methodology. (J3)

Truth

Data journalists have to evaluate their position toward data: “[…] if there is something weird in the data, we have to find out why. In general, information shouldn’t be taken out of context; this applies to all types of journalism.” (J4) Informants stressed the central role of truth in sensor journalism. Bodily sensors quantify physical reactions and “might also reflect a specific reality. As a journalist, you have the responsibility to verify their truthfulness and be careful not to damage anyone in the process” (S2). Journalists need to “guarantee that the microdata is properly interpreted and represented, leading to a truth-based article” (J2). Most of the informants believe that this requires solid methodologies that take into account how participants’ bodies behave during data collection, data literacy and potential outcomes. Therefore, truth in sensor journalism becomes heavily mediated by transparency and respect for diversity.

Diversity

Especially for personal sensing, interviewees deemed diversity as inalienable. The individuals who yield data are different: different bodies, culture, social and physical skills. Sensors might behave differently in capturing information: “We should discuss how parameters that are collected can be different. Heartbeat can vary between people; it’s different for different groups of people. Older people have a different heartbeat compared to young people” (J5). Therefore, diversity stood out as a key value for sensor journalism: “trying and investing a lot of energy in figuring out technical settings that include and collect representative data is a very important thing” (J7). This aspect could even bring about new expertise in the newsrooms, for example health experts that could support the interpretation of such data for journalistic storytelling.

Respect

Our results indicate that diversity is closely bound to respect. “[Respect for diversity] depends on the composition of the sample of people you are taking data from” (S2). More specifically, when discussing the intersection of interviews and sensors, journalists touched upon all the aspects connected to making people feel safe and protected when putting their data up for grabs. Informants saw fostering safety as the first step toward trust, which would be key in convincing people to take part in investigations: “If you are using very personal data that collect private information, then you have created even more trust between you and the other person. And if it’s fun data — you might have to convince them less.” (J3). In this context, respect emerged as an underlying theme that is variably connected with other ethical values. “Respect is about people themselves” (J2), and since people are at the center of data collection, journalists should always act respectfully.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we investigated how data journalists understand and shape traditional and emergent ethical values when working with or speculating about embodied sensing. The results help us answer the initial questions that motivated this study. First, in relation to RQ1, our findings show that interviewed data journalists apprehended fundamental values for their work both formally and informally. By working at and receiving training in established newsrooms, they learned key values that allow them to carry out journalistic work. However, in accordance with the ethical considerations for data journalists suggested by Bradshaw (Citation2014), by independently exploring new technologies they also developed accessory knowledge and sensibility that update and enrich those values. This applies in particular with regard to issues of privacy and source protection but also the vulnerability of sources pointed out, for example, by Palmer (Citation2018). When tinkering with sensors, data journalists implicitly referenced general values and expanded them to fit their technological needs. A second look at offers a glimpse at how their practice is stratified and benefits from traditional training and newsroom work as well as individual experience with technologies. By centering our questions and analysis around making these values emergent, we were able to adapt the five central values by Rao and Lee (Citation2005) and expand them for sensor journalism. In the normative list below, we suggest a straightforward answer to RQ2:

Previous studies have largely identified privacy with the concept of protecting sources (Chaparro-Domínguez and Díaz-Campo Citation2021). For sensor journalism, we argue that apart from anonymizing data if they are potentially harmful to individuals, data ownership must be shared among the parties. This includes providing individuals with information regarding data storage and security. The reinforcement of privacy could occur at an early stage of the project, possibly through tight forms of informed consent, not only to reassure readers but also to act as a fundamental part of the project that begins with setting up data collection.

Transparency calls for journalists to be aware of how sensitive personal data are and to treat them in the most transparent way possible. According to Dörr and Hollnbuchner (Citation2017), automation has caused a shift in accountability. Journalists now depend on third parties and cannot be held fully accountable because they rely on non-journalistic figures or even machines. For sensors, similar problems could arise when readers are uncertain about how data have been collected and processed. This aspect of transparency appears in our findings: various informants stress the importance of describing their technical setting to interviewees and readers alike. Rather than prioritizing the publication of sensor data (which could also create additional privacy concerns), journalists could dedicate effort in explaining how data have been collected and transformed for the sake of the project. This includes sharing instructions and code to replicate the data collection setting.

Regarding diversity, we found that acknowledging and respecting differences among bodies was an important part of sensor journalism. For example, Rao and Lee (Citation2005) emphasize that journalists must acknowledge and respect their peers and readers’ cultural, religious and ethical values. Acknowledging the role of humans, when bodies produce data, journalists could attentively consider their sampling procedure and findings based on with whom they performed data collection, including diversity regarding gender, age or culture.

The fourth value, truth, concerns honesty on how and why journalists collect personal and sensitive data. Openness and honesty are key in ensuring participants understand what information is collected from their bodies. Truth is often discussed with regards to automation and journalistic accountability (e.g., Dörr and Hollnbuchner Citation2017). Informants stressed three additional aspects of truth: context, sources and data. Truth has to do with how results are presented to the audience in a realistic manner – without assumed objectivity and avoiding positivistic relations between collected data and reported events. Personal sensing shows how close sensor journalism can be with traditional interviews, where it is important to build mutual trust between the journalist and interviewee.

The fifth value, respect, regards protecting and respecting individuals who donate data, such as valuing individuals’ privacy and differences. Respect is linked to prolonged interaction with the audience to understand their needs and engage them in the project (Boyles and Meyer; 2016). Similarly, for journalists working with sensors, respect regards protecting and recognizing individuals who donate data, such as valuing individuals’ privacy and differences. In sensor journalism, the prolonged interaction between reporters and the subjects of data collection could foster respect between the parties and increase journalists’ accountability and trustworthiness.

The normative nature of our findings derives several points for discussion. First, confirming what several scholars already noted, data journalists understand themselves as an independent community of practitioners. These communities engage informally in knowledge-sharing activities across national borders and organizations as well as in data gathering (Appelgren Citation2016; Porlezza and Splendore Citation2019). Members of this broad community see themselves as journalists with enhanced technological skills and a more open mindset compared to traditional reporters. Some of them even actively advocate for ethical practices and open-source culture within newsrooms and among other practitioners. However, in terms of ethics, interviewed journalists did not see a need for updated codes of conduct, while scholars did. This could be related to how journalists have been found to normalize technological practices rather than disrupting routines (Molyneux and Mourão Citation2019; Heft and Baack Citation2021). Instead of explicitly working toward formalizing best practices, we found that interviewed data journalists gradually self-regulate the production process by either referencing informal rules or loosely basing their work on existing ones. When openly questioned about which ethical values are key for sensor journalism, journalists were able to redefine every single one of them according to the technology at hand. Privacy, transparency, truth, diversity, and respect emerged as distinct ethical challenges that practitioners often tackle with their practical knowledge and tools. Coddington (Citation2015) argues more generally, data journalists should engage firsthand in conversations about ethics and human values when using novel or unexplored technologies. As in the case of the sensor journalism manifesto by Wittlich, Lehmann, and Vicari (Citation2019), or as found in online discussion forums (Craig, Ketterer, and Yousuf Citation2017) cooperative work among journalists easily leads to useful and practical guidelines for everyday production by fostering the emergence of central ethical values, Lastly, since formalizing technology-specific ethical guidelines is not a trivial task, we argue, in line with Nolan (Citation2006), that active participation and interaction between journalists and journalism scholars could be a rather useful approach to put journalists in control through a novel form of expanding on norms, i.e., shared discussion and participatory work since both parties are already part of how norms and ethical values are formed in journalism. To this extent, VSD has proven to be particularly fruitful in giving journalists a participatory space to creatively discuss sensor journalism and its methodologies. Additionally, since it characterizes influence as a hermeneutic circle where technologies and practitioners shape each other (Willis Citation2006; O’Day, Bobrow, and Shirley Citation1996), VSD allowed for a thorough evaluation of the context in which data journalists operate when working with sensors. As a result, it is noticeable how this reciprocal influence is at work also in sensor journalism: bodily sensors prescribe certain behaviors to journalists by allowing collection of specific types of data. Journalists assume certain ethical concerns based on that. On the other hand, they often push the boundaries of technologies by inventing new combinations and ways of collecting data.

This study presents some limitations. First, we recognize that our investigation is limited to a western European context and our findings are narrowly localized. Moreover, the small sample of participants, while still being qualitatively relevant, could be seen as non-representative of the European data journalists’ scene. In the future, these types of investigation could benefit from larger discussions with more stakeholders. Lastly, our contributions are based on the first part of VSD: conceptual and empirical investigations. Whereas technical investigations are a fundamental component of VSD, we decided to limit our work to the first two phases.

This study thus contributes to widening the debate around the ethical impact of specific technologies on digital journalism and challenges the idea of maintaining neutral principles that fit any technology ascribed into journalistic codes of ethics. In conclusion, despite the discussed limitations, we are able to suggest an expansion of ethical values to sensor journalism and clarify how journalists apprehend and make them actionable in their everyday practices.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, B., and E. Borges-Rey. 2019. “Encoding the UX: User Interface as a Site of Encounter between Data Journalists and Their Constructed Audiences.” Digital Journalism 7 (9): 1253–1269.

- Appelgren, E. 2016. “Data Journalists Using Facebook.” Nordicom Review 37 (1): 156–169.

- Appelgren, E. 2018. “An Illusion of Interactivity.” Journalism Practice 12 (3): 308–325.

- Appelgren, E., and G. Nygren. 2019. “HiPPOs (Highest Paid Person’s Opinion) in the Swedish Media Industry on Innovation: A Study of News Media Leaders’ Attitudes towards Innovation.” The Journal of Media Innovations 5 (1): 45–60. https://doi.org/10.5617/jomi.6503.

- Bailey, H., M. Daniels, and A. Wattenberger. 2020. Reconstructing seven days of protests in Minneapolis after George Floyd’s death. The Washington Post. October 9. https://www.washingtonpost.com/2fgraphic/2020/national/live-stream-george-floyd-protests/

- Bakker, P., P. Broertjes, A. van Liempt, M. Prinzing, and G. Smit. 2013. “This is Not What WE Agreed.” Journalism Practice 7 (4): 396–412.

- Bardzell, S. 2010. “Feminist HCI: Taking Stock and Outlining an Agenda for Design.” In CHI ’10: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages 1301–1310. ACM.

- Bounegru, L., and J. Gray. 2021. The Data Journalism Handbook: Towards a Critical Data Practice, 415. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Boyles, J. L., and E. Meyer. 2016. “Letting the Data Speak.” Digital Journalism 4 (7): 944–954.

- Bradshaw, P. 2014. “Data Journalism.” In Zion L., and Craig D., Ethics for Digital Journalists, 214–232. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315761428

- Bui, L. 2014. A (working) typology of sensor journalism projects. Comparative Media Studies. October 7. http://cmsw.mit.edu/working-typology-sensor-journalism-projects/

- Caswell, D. 2019. “Structured Journalism and the Semantic Units of News.” Digital Journalism 7 (8): 1134–1156.

- Chaparro-Domínguez, M.-Á, and J. Díaz-Campo. 2021. “Data Journalism and Ethics: Best Practices in the Winning Projects (DJA, OJA and Sigma Awards).” Journalism Practice 1–19.

- Choe, E. K., N. B. Lee, B. Lee, W. Pratt, and J. A. Kientz. 2014. “Understanding Quantified-Selfers’ Practices in Collecting and Exploring Personal Data.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1143–1152).

- Coddington, M. 2015. “Clarifying Journalism’s Quantitative Turn.” Digital Journalism 3 (3): 331–348.

- Craig, D., S. Ketterer, and M. Yousuf. 2017. “To Post or Not to Post: Online Discussion of Gun Permit Mapping and the Development of Ethical Standards in Data Journalism.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 94 (1): 168–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016684796.

- Curran, J. 2005. “Foreword.” In Making Journalists, edited by H. de Burgh, xi–xv. London: Routledge.

- Deutscher Presserat. 2019, September 11. “Publizistische Grundsätze (Pressecodex): Richtlinien für die publizistische Arbeit nach den Empfehlungen des Deutschen Presserats.” Pressecodex, October 14, 2022. https://www.presserat.de/pressekodex.html

- Diakopoulos, N. 2019. Automating the News: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Media. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Dörr, K. N., and K. Hollnbuchner. 2017. “Ethical Challenges of Algorithmic Journalism.” Digital Journalism 5 (4): 404–419.

- Dunne, A., and F. Raby. 2013. Speculative Everything: design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Ekström, M., Kroon, Å., & Nylund, M. (Eds.). 2006. News from the Interview Society. Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:norden:org:diva-10023

- Ferreira, B., W. Silva, E. Oliveira, and T. Conte. 2015. “Designing Personas with Empathy Map.” Designing Personas with Empathy Maps 501–505. https://doi.org/10.18293/SEKE2015-152.

- Ferrucci, P., and G. Perreault. 2021. “The Liability of Newness: Journalism, Innovation and the Issue of Core Competencies.” Journalism Studies 22 (11): 1436–1449.

- Friedman, B. 1996. “Value-Sensitive Design.” Interactions 3 (6): 16–23.

- Friedman, B., P. Kahn, and A. Borning. 2002. “Value Sensitive Design: Theory and Methods.” University of Washington Technical Report 02-12-01, 2–12.

- Friedman, B, and P. H. Kahn. 2007. “Human Values, Ethics, and Design.” In The Human-Computer Interaction Handbook, edited by A. Sears, J. A. Jacko, J. A. Jacko, 1267–1292. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Friedman, B., P. H. Kahn, and A. Borning. 2008. The Handbook of Information and Computer Ethics, Chapter 4: Value Sensitive Design and Information Systems. John Wiley and Sons.

- Gray, J., L. Chambers, and L. Bounegru. 2012. The Data Journalism Handbook: How Journalists Can Use Data to Improve the News. O'Reilly Media, Inc.

- Heft, A., and S. Baack. 2021. “Cross-Bordering Journalism: How Intermediaries of Change Drive the Adoption of New Practices.” Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884921999540.

- Hepp, A., andW. Loosen. 2021. “Pioneer Journalism: Conceptualizing the Role of Pioneer Journalists and Pioneer Communities in the Organizational Re-Figuration of Journalism.” Journalism 22 (3): 577–595. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919829277.

- Hern, A. 2018. Fitness tracking app Strava gives away location of secret US army bases. Guardian. January 28. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jan/28/fitness-tracking-app-gives-away-location-of-secret-us-army-bases

- Howard, A. 2013. Sensoring the news. Radar. March 22. http://radar.oreilly.com/2013/03/sensor-journalism-data-journalism.html

- Latour, B. 1992. Where are the missing masses? the sociology of a few mundane artifacts. Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change, pages 225–258. http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/50-MISSING-MASSES-GB.pdf

- Loosen, W., L. Ahva, J. Reimer, P. Solbach, M. Deuze, and L. Matzat. 2022. “X Journalism’.Exploring Journalism’s Diverse Meanings through the Names we Give It.” Journalism 23 (1): 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920950090.

- Journalistförbundet 2020. Rules of professional conduct. https://www.sjf.se/yrkesfragor/yrkesetik/yrkesetiska-regler/rules-professional-conduct

- Kovach, B., and T. Rosentiel. 2021. The Elements of Journalism, Revised and Updated 4th Edition: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. 4th ed. New York. Crown Publishing Group.

- Kuznetsov, S., G. Davis, J. Cheung, E. Paulos. 2011. Ceci n'est pas une pipe bombe: authoring urban landscapes with air quality sensors. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '11), Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2375–2384. https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979290

- Mears, C. L. 2012. “In-Depth Interviews.” Research Methods and Methodologies in Education 19: 170–176.

- Molyneux, L., and R. R. Mourão. 2019. “Political Journalists’ Normalization of Twitter.” Journalism Studies 20 (2): 248–266.

- Moradi, J., and A. Howard. 2013. ‘What do sensors mean for news, society, and science?’ SXSW 2013. March 10. https://www.slideshare.net/javaun/what-do-sensors-mean-for-news-science-and-society

- Morini, F., J. Pomerance, A. Meide, T. Quân, T. Hönig, M. Dörk, and E. Appelgren. 2021. Digital Go-Alongs: Recounting Individual Journeys through Personal Data as Journalistic Stories [Conference Presentation]. Computation + Journalism 2021. Northeastern University, Boston, MA, United States.

- Nolan, D. 2006. “Media, Citizenship and Governmentality: Defining “the Public” of Public Service Broadcasting.” Social Semiotics 16 (2): 225–242.

- NUJ (National Union of Journalists) 2011. “Code of Conduct”. https://www.nuj.org.uk/about-us/rules-and-guidance/code-of-conduct.html

- O’Day, V. L., D. G. Bobrow, and M. Shirley. 1996. “The Social-Technical Design Circle.” CSCW 1996: Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, pages 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1145/240080.240246

- Palmer, R. 2018. Becoming the News. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Pitt, F. 2014. Sensors and Journalism. New York: Columbia Journalism School. https://towcenter.gitbooks.io/sensors-and-journalism/content/index.html

- Porlezza, C., and T. Eberwein. 2022. “Uncharted Territory: Datafication as a Challenge for Journalism Ethics.”. In: Karmasin, M., Diehl, S., Koinig, I. (eds) Media and Change Management. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86680-8_19

- Porlezza, C., and S. Splendore. 2019. “From Open Journalism to Closed Data: Data Journalism in Italy.” Digital Journalism 7 (9): 1230–1252.

- Primo, A., andG.Zago. 2015. “Who and What Do Journalism?.” Digital Journalism 3 (1): 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.927987.

- Rao, S., and S. T. Lee. 2005. “Globalizing Media Ethics? An Assessment of Universal Ethics among International Political Journalists.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 20 (2): 99–120.

- Rosner, D. K., S. Kawas, W. Li, N. Tilly, and Y. Sung. 2016. “Out of Time, out of Place: Reflections on Design Workshops as a Research Method.” In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, pp. 1131–1141.

- Santana, A. D., and T. Hopp. 2016. “Tapping into a New Stream of (Personal) Data: Assessing Journalists’ Different Use of Social Media.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 93 (2): 383–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016637105.

- Schmitz Weiss, Amy. 2016. “Sensor Journalism: Pitfalls and Possibilities.” Palabra Clave - Revista de Comunicación 19 (4): 1048–1071. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2016.19.4.5.

- Sengers, P., K. Boehner, S. David, and J. J. Kaye. 2005. “Reflective Design.” In Proceedings of the 4th Decennial Conference on Critical Computing: Between Sense and Sensibility, pages 49–58. ACM.

- Society of Professional Journalists (US). 2014. Society of Professional Journalists: Code of Ethics. Society of Professional Journalists. https://www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp

- Steen, S., A. M. Grøndahl Larsen, Y. Benestad Hågvar, and B. Kjos Fonn. 2019. “What Does Digital Journalism Studies Look like?” Digital Journalism 7 (3): 320–342.

- Tagesspiegel Wittlich, H., H. Lehmann, M. Gegg, and D. Meidinger. 2018. Radmesser: Spurensicherung, Wir messen, wo Autos Radfahrer eng überholen. Tagesspiegel. August 8. https://interaktiv.tagesspiegel.de/radmesser/kapitel3.html

- Tesla, Blog. 2013. A Most Peculiar Test Drive. February 13 https://www.tesla.com/blog/most-peculiar-test-drive

- The Union of Journalists in Finland 2014. Guidelines for journalists. https://journalistiliitto.fi/en/ground-rules/guidelines/

- Thurman, N. 2019. “Computational Journalism.” In Wahl-Jorgensen, K., & Hanitzsch, T. (Eds.). (2009). The Handbook of Journalism Studies. Milton Park: Routledge.

- Whitehouse, G. 2010. “Newsgathering and Privacy: Expanding Ethics Codes to Reflect Change in the Digital Media Age.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 25 (4): 310–327.

- Widholm, A., and E. Appelgren. 2022. “A Softer Kind of Hard News? Data Journalism and the Digital Renewal of Public Service News in Sweden.” New Media & Society 24 (6): 1363–1381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820975411.

- Willis, A. 2006. “Ontological Designing.” Design Philosophy Papers 4 (2): 69–92. https://doi.org/10.2752/144871306X13966268131514.

- Wittlich, H., H. Lehmann, and J. Vicari. 2019. Manifest für einen journalismus der dinge. Tagesspiegel. May 8. https://www.tagesspiegel.de/gesellschaft/medien/verkuendung-auf-der-re-publica-manifest-fuer-einen-journalismus-der-dinge/24316916.html