Abstract

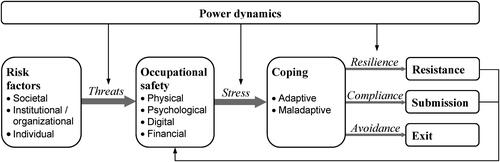

Killings, as the most extreme form of violence against journalists, receive considerable attention, but journalists experience a variety of threats from surveillance to gendered cyber targeting and hate speech, or even the intentional deprivation of their financial basis. This article provides a comprehensive, interdisciplinary framework of journalists’ safety, summarized in a conceptual model. The aim is to advance the study of journalists’ safety and improve safety practices, journalism education, advocacy, and policy making - vital as press freedom and fundamental human rights face multifaceted challenges, compromising journalists’ ability to serve their societies. Journalists’ occupational safety comprises personal (physical, psychological) and infrastructural (digital, financial) dimensions. Safety can be objective and subjective by operating on material and perceptional levels. It is moderated by individual (micro), organizational/institutional (meso), and systemic (macro) risk factors, rooted in power dynamics defining boundaries for journalists’ work, which, if crossed, result in threats and create work-related stress. Stress requires coping, ideally resulting in resilience and resistance, and manifested in journalists’ continued role performance with autonomy. Compromised safety has personal and social consequences as threats might affect role performance and even lead to an exit from the profession, thus also affecting journalism’s wider function as a key institution.

The year 2022 marks the tenth anniversary of the UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity. Since 1993, on average, one journalist has been killed every seven days for work-related reasons.Footnote1 As a consequence, the global monitoring of safety threats to journalists has strongly focused on physical safety, primarily documenting killings of reporters, imprisonments, forced exile, and legal restrictions. Safety has thus emerged as an important topic in academic and public discourse, given the issues journalists have encountered globally because of, among other things, covering topics that raise the ire of governments and drug lords, and reporting from conflict zones or, more recently, from places especially hit by Covid-19.

Journalists’ occupational safety, however, is jeopardized in many more ways these days – even in countries where the workforce is considered to be physically comparatively safe. For one, journalists experience a variety of psychological threats. Particular areas of concern include aggressions such as hate speech (Obermaier, Hofbauer, and Reinemann Citation2018) and sexual harassment (Ferrier and Garud-Patkar Citation2018; Idås, Orgeret, and Backholm Citation2020; Unaegbu Citation2017), often in digital environments (Adams Citation2018; Chen et al. Citation2020), losing a colleague to violence, and experiencing other multiple forms of job-related threats and aggressions on journalists’ mental and emotional wellbeing (Garcés-Prettel, Arroyave-Cabrera, and Baltar-Moreno Citation2020; Hughes and Márquez-Ramírez Citation2018; Osofsky, Holloway, and Pickett Citation2005; Parker Citation2015). The financial security of journalistic labor has also become an issue of increasing concern as dysfunctional media markets and political entanglements, advertisement cuts and, in conjuncture, the lack of strategies to monetize digital content jeopardize the continuous, professional performance of journalistic work all over the world (e.g., Hayes and Silke Citation2019; Matthews and Onyemaobi Citation2020).

Journalists’ safety not only affects individual journalists and the profession but, by threatening freedom of expression, also democracies and societies as a whole (Høiby and Ottosen Citation2019). A growing body of research is dealing with these issues, in large part prompted by the UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity (2012), but it still remains the case that the majority of studies focus on one context or a limited number of contexts/case studies and a specific aspect of safety (e.g., Garcés-Prettel, Arroyave-Cabrera, and Baltar-Moreno Citation2020; Hasan and Wadud Citation2020; Hughes and Márquez-Ramírez Citation2018; Kim Citation2010; Nyabuga Citation2016). Comparative studies are rare and mostly focus on specific regions (Asal et al. Citation2018; Bjørnskov and Freytag Citation2016; Chen et al. Citation2020; Hughes et al. Citation2017; Marcesse Citation2017). Despite large policy interest (Torsner Citation2017), this topic remains under- or unsystematically researched and there is, to date, no common definition of journalists’ safety upon which a conceptual framework can rest that relates the roots of the lack of safety to individual and societal consequences. A conceptual framework would capture, in a holistic way, the main factors posing threats to journalists’ occupational safety, the coping strategies for dealing with both the threats and the resulting stress and, depending on the support structures and resources available to help journalists cope, journalists’ differing responses and the final outcomes of these responses. Given the multifaceted issue at hand, this framework must be interdisciplinary, cover the totality of these complexities in a truly global way, and guide future investigations.

This article aims at providing such a conceptual framework by combining innovatively perspectives from the sociology of journalism, political theory, psychology, media economy, risk analysis, and wider safety research literature. We start by proposing a comprehensive definition of journalists’ safety built upon an understanding of the range of threats to safety since safety is mostly considered from the perspective of its absence. We continue by carving out what we diagnose as causes of threats – which we see rooted in power dynamics that play out between journalists and the political elite or specific social groups making claims to power but also in journalists’ responses and actions when they find themselves in unsafe situations and conditions. Power is the fundamental dynamic that undergirds journalists’ safety. Power manifests in factors that put journalists’ safety at risk, and these factors spawn threats, which in turn lead to stress, coping, self-preservation efforts, and actions. We propose a conceptual model of journalists’ safety as a methodological tool, thus offering potential directions for future research (). We conclude by discussing the implications of our contribution to journalism education, advocacy, and policy making.

Conceptualizing and Defining Journalists’ Safety

Safety research defines “workplace safety as an attribute of work systems reflecting the (low) likelihood of physical harm—whether immediate or delayed—to persons, property, or the environment during the performance of work” (Beus, McCord, and Zohar Citation2016, 353). While this conceptualisation provides a good starting point, our definition must detach itself from a concrete workplace and focus instead on work-related tasks because for journalists, workplaces include their offices, reporting sites, and their homes (especially for freelancers). Consequently, we propose to use the term occupational safety because journalists’ safety is linked to their occupational activities as journalists. In performing these tasks, the well-being of a journalist as a person as well as their autonomy as an institutional actor are interconnected and thus are integral to a journalist’s safety.Footnote2

In the literature, the issue of journalists’ safety is typically approached from the perspective of its absence. Research usually focuses on situations in which the likelihood of harm is high. As Workneh (Citation2022) explained, “in its most basic interpretation, particularly in authoritarian and semi-authoritarian contexts, safety denotes the absence of harm generated from the journalist’s reporting activities”. Existing research into the risks journalists face that can result in potential harm for them and the institution of journalism shows that not only journalists’ physical but also their psychological safety is at stake (). Scholars such as Frazier et al. (Citation2017), Edmondson (Citation1999), and Kahn (Citation1990) define psychological workplace safety as the belief that the workplace allows for risk-taking without the likelihood of severe harm within an organizational context, for example, in a team. In journalism research, a definition must also look beyond the organizational and institutional context. Journalists face scrutiny from a wider range of actors and the reactions to their work are often public. Hence, for journalists, psychological safety includes the possibility of risk-taking without the likelihood of harm from outside actors and institutions, too.

Table 1. Safety dimensions and related threats.

Further, the functioning of journalism is highly dependent on two types of infrastructure: financial and technological/digital. If these are torpedoed or the digital space rendered as threatening, journalistic performance is jeopardized. Thus, journalists must have what we term digital safety: the digitization of their work must not put the workforce at risk. They also need financial safety in terms of continuation of their employment and occupation, currently threatened by precarity in the form of low or reduced wages and job loss, resulting in a shrinking workforce and de-professionalization tendencies observed globally.

Therefore, we conceptualize journalists’ safety as the extent to which journalists can perform their work-related tasks without facing threats to their physical, psychological, digital, and financial integrity and well-being. Given that these threats are experienced in the course or as a result of performing their professional duties, all four dimensions – physical and psychological, digital, and financial – are part of journalists’ occupational safety. This definition captures both objective manifestations of threats in the real world (material level) and journalists’ subjective awareness thereof (perceptional level). We use the term threat instead of harm because threats can be both a stated intention by antagonists that harmful actions will be taken against an individual and the anticipation by the threatened individual of imminent harm. Thus, threat refers to anything with the potential to cause harm, while harm is the actual effect(s), which we include under dimensions of safety. Threats are harmful in their own right because they compromise journalists’ safety and their ability to perform their duties and serve their respective societies.

Conceptualizing and Defining Threats to Journalists’ Safety

We define threats to journalists’ safety as the actions and conditions that increase the risk of physical, psychological, digital, and financial harm to journalists as human beings and as institutional actors (Brambila and Hughes Citation2019). While safety research operates with the term likelihood, we propose the use of the term risk in the context of journalists’ safety. Both convey a similar meaning but the term risk bears more relevant, normative implications for what is “safe”. Drawing from the interdisciplinary field of risk analysis, risk can be defined “by the probability and severity of adverse effects” (Aven Citation2011, 515). Accordingly, risk is a combination of likelihood and the extent of harm that may follow as a consequence. Applied to journalism research, (high-)risk situations evolve if journalists face (existential) threats to themselves as individuals and institutional actors and to the viability and sustainability of journalism as an institution making a meaningful and vital contribution to social life. Here again, our definition aims to encompass both the objective manifestations of risk and threats, and journalists’ subjective perceptions of them (see also Hughes et al. Citation2021).

Existing research () revealed a diverse set of threats but our focus is on threats exerted intentionally.2 To start with, physical threats may lead to bodily harm. They include murder, beating, torture, sexual assault, and other work-related attacks, forced relocation, arrest, detention, imprisonment, abduction and disappearance as well as acute biological and weather-related threats, such as risks to health in the COVID-19 pandemic and from covering disasters. Psychological threats target emotional wellbeing. They include intimidation, coercion, extortion, sexual harassment, doxing (dissemination of personal information), demeaning and hateful speech, public ridicule and discrediting, citizen vigilantism, workplace bullying, and potentially traumatizing work assignments. Digital threats include various hacking and surveillance attacks as well as limiting or blocking access to information, sources, and audiences, thus pointing to the urgent need to study the “multifaceted chilling effects of online attacks” (Waisbord Citation2020, 1038). A chilling effect has also been detected in the study of financial threats leading to precarious work conditions (Hayes and Silke Citation2019). Precarity challenges the operational basis of journalism as an institution. On the individual level, precarity manifests in unemployment, the loss of income or position, professional standing, and reputation – or, in less well-equipped journalistic cultures, it characterizes work conditions that had never been economically stable (e.g., Matthews and Onyemaobi Citation2020). Freelance work, in particular, deprives a journalist of the support of a news organization that can implement safety precautions and training for reporting (Brambila Citation2018), or provide life insurance and access to good healthcare (Steiner and Chadha Citation2022). Freelance work may also increase the incentives to take risks because pay is determined by the number of stories produced as well as “scoops” that may require entering into dangerous scenarios.

These threats can originate from actors and groups within the state, but also from non-state and/or foreign actors (e.g., hacking or disinformation, see ). While not of primary focus, all four types of threats can also be directed at family and loved ones and cause risk of harm to their integrity and wellbeing. Moreover, while there are clear distinctions between the different dimensions and threats to safety, there are also significant overlaps. Digital, physical, and financial safety are clearly interlinked with psychological safety (e.g., online hate speech, physical attacks, and job instability could have psychological consequences). In spite of these overlaps, we classify into dimensions as an analytic exercise that will help us understand interactions between them and allow for tailored support systems.

All these threats by their nature compromise journalists’ occupational safety and potentially jeopardize the continuation of the performance of journalistic tasks, as well as journalists’ autonomy, performance and, fundamentally, journalists’ ability to fulfill their social functions. Threats are also a gross violation of individual human rights, and of transparency and accountability principles. They undermine people’s right to know that in turn reduces the level of trust in media and participation in public debate so essential for democracy (Hasan and Wadud Citation2020; Marino Citation2013). Thus, the safety of reporters is equally a problem for journalism, media freedom and freedom of expression, democracy, and society as a whole (Høiby and Ottosen Citation2019).

The Root of Safety Issues: Power Dynamics

By building on political and sociological theory, we argue that power dynamics are at the root of the described threats, therefore, undergirding journalists’ safety. While different ideas about power exist, we focus on conceptualizations of “power as domination, largely characterized as power over” (Haugaard Citation2012, 33). According to Weber (Citation1979), power can be understood as the probability of being able to carry out one’s own will (or agenda) despite resistance. More differentiated, power can be conceptualized as encompassing three dimensions (Lukes Citation1974/2005; Heywood Citation2015): it may, first, “involve the ability to influence the making of decisions; second, be reflected in the capacity to shape the political agenda and thus prevent decisions being made; and third, take the form of controlling people’s thoughts by the manipulation of their perceptions and preferences” (Heywood Citation2015, 110). The last form of power is also linked to ideological/symbolic or discursive power (115) as the “power to construct reality” (Bourdieu Citation1979, 79; see also Hayes and Silke Citation2019).

These power dimensions can refer to an individual or collective actors’ power over journalists, or conversely to the journalists’ power over these actors. In accordance with the three dimensions of power, while journalistic influence (1) does not comprise any kind of legislative authority, it can under certain circumstances (2) impact the political agenda and (3) shape individuals’ perceptions, attitudes, and public opinion (e.g., Levendusky and Malhotra Citation2016; Lohner and Banjac Citation2017; Van Dalen and Van Aelst Citation2014) and, thus, (4) construct reality. Journalists can have this influence because they have privileged access to two scarce resources: (a) information and (b) public attention. Independent of the political and media system under investigation, these resources are granted either on behalf of the state or in the interest of the general public. Journalists can thereby potentially threaten the interests of specific actors and groups. Triggers might be fear of being harmed physically or deprived materially due to journalistic coverage, but also concern that journalists’ reporting may publicly challenge the “integrity or validity of the ingroup’s meaning system” (Stephan, Ybarra, and Morrison Citation2009, 43). This can create a feeling of being “dishonored, disrespected, or dehumanized” by members of the journalistic corps (44). Accordingly, journalists are targeted not only because they might uncover illegitimate exertion of power, but also because of their (feared) influence over public opinion and, in the case of female and minority journalists, because they embody cultural challenges to systems of oppression that privilege certain groups or identities. To counter this influence, actors and groups apply means of power in a fight over dominance. Such direct or indirect attempts to limit the symbolic power and influence of journalists affect journalistic autonomy (Löfgren Nilsson and Örnebring Citation2016), i.e., their ability to self-govern, to make decisions in (moral) independence from internal (e.g., management, economic) and external (e.g., political, legislative) factors (e.g., Sjøvaag Citation2013; Reich and Hanitzsch Citation2013).

Use of power can create resistance (Weber Citation1979), which those in the position of power then have to cope with (see also, Barbalet Citation1985). Antagonists can resist journalistic power that creates the perceived and unwanted media effects by using (1) decision-making power to limit journalistic freedoms; (2) power to not make/allow a decision, such as (not) passing legislation for trespasses against journalists, or preventing the application of such laws, e.g., impunity; and (3) symbolic power to endorse ideologies antagonistic to journalism, e.g., establishing a delegitimizing “fake news” narrative (Lukes Citation1974/2005; see also Carlson, Robinson, and Lewis Citation2021). Connected to this, antagonistic forces can also exercise instrumental power (Popitz Citation2017), i.e., the power to ‘control’, conduct and safeguard conformity through “the ability to give and take … to be able to make arrangements concerning punishments and rewards that appear credible to those concerned” (12–13). Examples include economic pressure such as governments’ withdrawal of advertisements, media’s dependence on clientelistic quid-pro-quos with government, and other influence exerted through private sector advertisers’ interests (e.g., Guerrero and Márquez-Ramírez Citation2014; Hanusch, Banjac, and Maares Citation2020; Wright, Scott, and Bunce Citation2020). Societal pressure for journalists’ protection may be lacking where populist rhetoric or political instrumentalization of news has eroded trust; thus, governments, corporations, cartels, even some members of the public may join in harassment when the press system is perceived as acting against public or group interests (González Macias and Reyna García Citation2019).

The most intimidating power is the power of action that constitutes the “capacity to inflict harm on others” (Popitz Citation2017, 11). This form of power, exerted as psychological or physical violence (and captured by our psychological and physical dimensions of safety), is based on inequalities stemming from “inborn endowments, muscular strength … and, above all, from unequal control over contrived devices that enhance the efficiency of the harming action—weapons and the organizational arrangements for combat” (ibid., 11). Such violence is exerted by deviant, disinhibited individuals through misogynous or racist comments, including rape and death threats, but also strategically by members of deviant organizations (e.g., radical right-wing protesters) or by antagonists who constitute the ‘power elite’ in a country (e.g., Krøvel Citation2017; Preuß, Tetzlaff, and Zick Citation2017). When all these types of power coalesce in government, they can accumulate in their effect (Imbusch Citation2016).

Such power-based antagonistic political, ideological, legislative, economic, and public, i.e., societal, institutional/organizational, and group/individual pressures are the risk factors that create the threats classified in . They define the room for action within which journalists are expected to perform their work. If and when journalists maneuver to maximize performance and (intentionally or unintentionally) transgress this space beyond a threshold acceptable to antagonists, they become subject to threats and thereby expose themselves to risk. Given that safety is related to the absence, prevention and mitigation of risk that could lead to harm, we turn to a discussion of risk factors, which are rooted in the overriding power dynamics and are present at societal, institutional, organizational, and occasionally individual levels.

Risk Factors

Based on our definition of threats above, risk factors are able to influence whether, and thereby how likely, threats are to manifest in material or perceptional form (moderating factors). In statistical terms, risk factors determine to what extent threats (as independent variables) impact journalists’ safety (as dependent variable). We differentiate between individual (micro level), organizational or institutional (meso level), and societal (macro level) risk factors, and start with the latter, which comprise political, economic, and cultural risk factors.

Political risk factors determine journalists’ room to maneuver. In societies where the political system cannot guarantee the rule of law, crime, corruption, violence, and human rights abuses are frequently sources of threat (Hughes and Márquez-Ramírez Citation2018). Authoritarian controls reducing press freedom can also create threats that lead to serious harm to journalists, even in electoral democracies (Hamada Citation2022). This is especially true in hybrid democratic-authoritarian political systems where some journalists subscribe to norms that seek to restrain the power of the state, but they do so without the protection of the full rule of law (Hughes and Vorobyeva Citation2021). Closely related to political risk factors, we identify cultural risk factors which may be present in societies where racism, sexism, and homophobia prevail or at least find soil to thrive. Lastly, also closely related to political risk factors are economic risk factors, which include the condition of the journalistic labour market (e.g., O’Donnell and Zion Citation2019), and—from a political economy viewpoint—concentration of ownership, media owners, and collusion with the state (Garcés-Prettel, Arroyave-Cabrera, and Baltar-Moreno Citation2020). All macro level risk factors are interlinked. Thus, in a context such as Central and Eastern Europe, there have been recent democratic backslides, which include the problematic interlinking of political and economic interests and a worrying trend towards “media capture”, wherein “media outlets have been brought under direct or indirect government control”, including financially through the “weaponization” of government advertising revenue “to harm critical media and financially boost friendly outlets” (Selva Citation2020, 7–15).

Next, risk factors operate not only on the macro level but also on the meso level in the form of institutional and organizational risk factors. The rise of the platformisation of news and algorithm-mediated messages through social media as well as the blurred boundaries of journalistic workers with content providers pose threats in various ways, including digital hate and mob censorship (Waisbord Citation2020). Institutional and organizational risk factors may even interact with other risk factors, described above, because in more dangerous work environments they usually also manifest themselves at an institutional or organizational level. For instance, in societies where violence and suffering become frequent topics of coverage, safety risks for the journalists who cover them elevate (Backholm and Björkqvist Citation2012; Feinstein, Audet, and Waknine Citation2014; Flores Morales, Reyes Pérez, and Reidl Martínez Citation2012, Citation2014; Himmelstein and Faithorn Citation2002; Hughes et al. Citation2021; Høiby Citation2020; Newman, Simpson, and Handschuh Citation2003; Slavtcheva-Petkova Citation2018; Tumber Citation2006; Weidmann and Papsdorf Citation2010; Weidmann, Fehm, and Fydrich Citation2008). Consequently, certain newsbeats (e.g., crime, corruption, and politics) make these risks more salient in political systems that are authoritarian or mix democratic and authoritarian traits (Bromley and Slavtcheva-Petkova Citation2018; Garcés Prettel and Arroyave Cabrera Citation2017; Hughes and Vorobyeva Citation2021). Linked to journalistic routines, task-based risk factors can include witnessing violence and suffering or working in dangerous conditions while covering natural disasters, conflict or violence (Backholm and Björkqvist Citation2012; Feinstein, Audet, and Waknine Citation2014; Flores Morales, Reyes Pérez, and Reidl Martínez Citation2012, Citation2014; Himmelstein and Faithorn Citation2002; Hughes et al. Citation2021; Høiby Citation2020; Newman, Simpson, and Handschuh Citation2003; Slavtcheva-Petkova Citation2018; Tumber Citation2006; Weidmann and Papsdorf Citation2010; Weidmann, Fehm, and Fydrich Citation2008). Even within the organization, risk factors exist in the form of bullying bosses or colleagues, and sexual harassment.

On the micro level, we also evidence individual risk factors such as journalists’ personal and professional backgrounds, their occupational and political orientations, as well as personal role perceptions. Personality traits can be relevant as some might simply be willing to put themselves at risk, e.g., by reporting from specific situations or places hit by natural disasters or violent conflict (e.g., Dworznik-Hoak Citation2020; Feinstein Citation2006). Further, journalistic role perceptions can play a role, too. Journalists understanding themselves as watchdogs or critical change agents are more likely to pose a threat to business and political elites, and to influence public opinions or agendas, than journalists seeing themselves as opportunist facilitators or populist disseminators (Hanitzsch Citation2011, 485).

Interaction between the three forms of risk factors should also be taken into consideration. Examples abound - from the impact of intersectionality, for instance, being a female journalist in a “male” coded domain, and being female or a minority journalist and engaging online with audiences (e.g., Adams Citation2018; Chen et al. Citation2020) to challenging prevailing cultural norms through reporting on certain topics (e.g., immigration politics). Precarious working conditions have also been linked to the femininity of and in the workforce (Hayes and Silke Citation2019; Örnebring and Möller Citation2018).

All countries harbour such factors. In their positive form, e.g., constitutional guarantees of press freedom and labour security, these factors could be drivers of journalists’ safety; however, more often they are experienced as barriers to safety. For instance, even in countries where press freedom is enshrined in the constitution, the lack of independence, will, and capacity of judicial systems to enforce the rule of law, protect human rights, and respect press freedom become barriers to journalists’ safety (Waisbord Citation2002). They reflect the conflict between journalists’ attempts to act with autonomy and the aggressive means criminals, political factions, hate groups, and powerful officials use to try to silence them.

The Consequence of Safety Issues: Work-Related Stress

Antagonists’ threats emanate from a resistance to journalistic power (perceived or real), requiring journalists to react in self-defense. Socio-psychologically, the presence of threats creates work-related stress, particularly when resources to react (i.e., to cope) are insufficient. The psychologist Lazarus (Citation1990) conceptualized stress as a process occurring “when demands tax or exceed the person’s resources” (3), thus indicating a transactional model between an individual and their environment, and the idea of individual differences and variance in response to stress. According to Lazarus (Citation1990), “[t]ransaction implies that stress is neither in the environmental input nor in the person, but reflects the conjunction of a person with certain motives and beliefs (personal agendas, as it were) with an environment whose characteristics pose harm, threats, or challenges depending on these person characteristics” (3). Based on this, cognitive process models from psychology continue to suggest that journalists experience work-related stress when they perceive an imbalance between the potential harms of work-related risk and their resources, i.e., their ability to avoid or ameliorate these harms (Robinson Citation2018). Unattended work-related stress may harm journalists’ wellbeing and professional performance. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in journalists covering war, disaster, violence or suffering is frequently documented (Feinstein, Audet, and Waknine Citation2014; Flores Morales, Reyes Pérez, and Reidl Martínez Citation2012, Citation2014; Dworznik-Hoak Citation2020; Seely Citation2019). Harms from job stress may be similarly physiological as well as psycho-emotional, but less severe than PTSD. The range of harms from stress include physical symptoms, such as fatigue, numbness, exhaustion, headaches, insomnia, stomach ailments, and dermatological disorders as well as psychological and emotional symptoms such as depression, despondency, anxiety, sadness, shame, fear, and pessimism (Hughes et al. Citation2021). As Robinson (Citation2018) pointed out, the term stress is very contentious and “the ways in which the term stress [emphasis in original] is used in research is almost as subjective as an individual’s expression of a stress.”

Coping, Autonomy and Role Performance

The ability to cope successfully is critical for journalists to continue their work and stay in the profession and is related to power dynamics, i.e., the power vested in the institution of journalism in a country, the power exercised by the organization/its editors, and the professional and personal power of the journalists. According to Lazarus (Citation1990), once a person has appraised a transaction as stressful, they bring coping strategies into play. Coping strategies develop in two steps: an initial emotional appraisal of possible harm, followed by an appraisal of the resources available for coping (Folkman and Lazarus Citation1980; Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984).

Coping strategies may focus on fixing a problem (problem-oriented coping) or calming negative emotions, e.g., by reframing the situation (emotion-oriented coping), depending upon whether the person affected feels able to prevent or mitigate a potential harm (Alok et al. Citation2014; Alonso-Tapia et al. Citation2016). Coping strategies are not rooted solely in the psychological characteristics of the individual. Rather, coping also has a strong social component: people learn coping strategies from social support groups, such as friends, family, and co-workers. In collectivist cultures, norms, traditions and beliefs are also influential (Mesquita, Feldman Barrett, and Smith Citation2010). A body of work in multiple journalistic cultures and contexts has suggested that, when under duress, journalists form professional communities and display peer support, shared values, and teamwork (Dworznik-Hoak Citation2020; González Macías Citation2021; Hughes et al. Citation2021; Novak and Davidson Citation2013; Obermaier, Hofbauer, and Reinemann Citation2018; Osofsky, Holloway, and Pickett Citation2005). They turn to trusted communities of colleagues and evoke public service beliefs that anchor professional identities to support adaptive coping. In places where uneven rule of law leaves journalists without protection from police or the courts, collaborative reporting and forming alliances with civil society organizations to demand government protection seem to strengthen journalists’ safety (Cueva Chacón and Saldaña Citation2021; de León Vazquez et al. Citation2018; González Macías Citation2021; González de Bustamante and Relly Citation2021; Hughes et al. Citation2021). Studies documenting coping strategies thus suggest that professional solidarity, shared values, and teamwork elevate all dimensions of safety, by supporting physical safety through training for prevention and collaboration, and strengthening mental fortitude through camaraderie.

Coping strategies can be adaptive and maladaptive (Buchanan and Keats Citation2011). Adaptive coping strategies are typically problem-oriented and include active planning and seeking social support. Maladaptive coping is usually associated with avoidance (such as denial, suppression of emotions and thoughts, and social withdrawal) as well as alcohol and narcotics abuse. The coping approach adopted, therefore, can result in either resilience, compliance or avoidance with the ultimate outcomes being either resistance, submission or exit (see ). A problem-focused coping strategy that journalists resort to is to make changes to their reporting practices and overall role performance (Hughes et al. Citation2021). Several studies explore autonomy-reducing changes in journalists’ work performance as a response to stress-creating threats (Löfgren Nilsson and Örnebring Citation2016; Hasan and Wadud Citation2020; Hayes and Silke Citation2019; Hughes and Márquez-Ramírez Citation2017; Hughes et al. Citation2021; Adams Citation2018; Chen et al. Citation2020; Larsen, Fadnes, and Krøvel Citation2021). Such changes include self-censorship and curtailing reporting activities, examples of “compliance” responses that mitigate risk (e.g., Post and Kepplinger Citation2019) and whose outcome is submission. Another compliance response of sorts is minimizing risk, e.g., by limiting interactions with audiences or hiding one’s gender online. While these strategies may be functional and healthy for the person (adaptive), they can be considered dysfunctional for journalism’s performance (maladaptive). This two-faceted nature of journalists’ coping makes it a particularly relevant research subject. An extreme outcome of maladaptive coping is exiting the profession (see, e.g., Örnebring and Möller Citation2018 or Stahel and Schoen Citation2020 on exit).

Journalists’ individual coping responses have also been found to include tactics to safely continue to work with autonomy. Successful coping processes create resilience, defined as a sustained process of “adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress” or put simply, ‘bouncing back’ (American Psychological Association Citation2012). Resilience is, therefore, a sustainable and effective way of dealing with risk. Based on literature, Bergström, Van Winsen, and Henriqson (Citation2015) conceptualize resilience as the intra- and interpersonal ability to cope with adversity or to regain a previous state following a disturbance or abrupt shock, suggesting also that resilience can be practiced on both meso/organizational and macro/societal levels (see also Aven Citation2011). When journalists achieve resilience, the outcome is resistance.

Ultimately, journalists’ autonomy and performance can be affected to a higher or lower degree by the safety threats they experience and the resulting stress as well as their ability to cope with threats and reach resilience. Hence, it is important to study closely the interrelation between risk factors, safety, work-related stress, coping and resilience, and journalistic autonomy and performance.

Conclusion

The documentation of threats to the journalistic profession other than violence is infrequent, the exposition of journalists’ coping mechanisms to deal with work-related stress is somewhat incomplete (Hughes et al. Citation2021; Iesue et al. Citation2021; Monteiro, Marques Pinto, and Roberto Citation2016; Monteiro and Marques, Citation2017; Relly and González de Bustamante Citation2017), and the explication of risk factors that beget threats remains fragmented. Safety research does not often distinguish between causes and symptoms, state and non-state actors, and structural and individual factors; and it is rarely sensitive to issues of gender, race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation and to intersectionality in general. Herein lies the significance of advancing both theory and empirical knowledge on journalists’ safety.

Based on this diagnosis of a vivid, yet scattered research field, our aim is to offer a comprehensive and holistic conceptual framework for the study of journalists’ safety. Drawing on a vast array of literature across multiple disciplines, our framework explicates the roots, risks, consequences, and requirements to advance the safety of journalists, culminating in an integrative model that conceptualizes pathways for studying journalists’ safety (). The various aspects of journalists’ safety outlined in this model are ensconced within the dynamics of power.

Occupational safety comprises physical, psychological, digital, and financial threats. These threats are moderated by societal, institutional or organizational, and individual risk factors (macro, meso, and micro levels), influencing how safe journalists are/feel (material and perceptional levels). The threats, in turn, may lead to work-related stress, creating a need for coping. If successful, coping builds resilience and allows the journalists to prevail in a threatening situation, even if their perceived safety is continuously compromised. Depending upon whether coping strategies protect or reduce editorial autonomy, coping may allow journalists to continue performing their roles and serving their societies.

The literature highlighted a key essential for coping and building resilience: the social resources journalists gain from their occupational networks of solidarity, or their social capital as defined in Brambila (Citation2018). If systematic support is scarce, which is often the case, and because journalists at risk often share positions and occupational identities strengthened through adversity, the most important source of fortitude seems to be bonds of solidarity between colleagues in similar situations and sharing similar values. Other societal actors can also provide support. Journalism education and advocacy groups can support journalists in building peer-networks beyond workplaces and also include the issues outlined in this article in journalism curricula. In addition, policy makers can have an important voice in extending the space in which journalists can maneuver despite the fact that countries may differ in their willingness to support journalism, financially and otherwise. Journalists’ perception of how safe they feel, how they assess their resources for coping, and how much support they receive from education, advocacy, and policy-making groups is, for most countries, still an open empirical question to be investigated in future studies.

Based on our conceptual model, we assume that the more the power dynamics shift in the direction of journalistic voices, the more risk factors they face, the less safe their occupational activity, the more stress they will experience, and the more resources they will require for coping. Bearing in mind that our definition of safety comprises four aspects of occupational safety (see ), this implies a rather novel insight that journalists in liberal democracies, who place higher value on freedom of speech and economic liberalism, may be confronted with a less secure occupational situation - with an important exception: In regimes in which the power dynamics privilege the ruling elite, the occupational safety of critical change agents, and of interventionist and watchdog journalists will fall short of the safety levels of their colleagues in liberal democracies. The most desirable outcome of the process described in seems to be resistance. However, we have to bear in mind that the underlaying perspective is a profoundly Western one; it implies that ruling powers and journalists do not or should not collude. In cultures that highly value social harmony, compliance would be an equal or even a preferred strategy, as such a way of coping is beneficial to both journalists and society. This point illustrates how important it is to acknowledge the perspective through which one classifies a coping strategy as either adaptive or maladaptive, and we strongly encourage future studies to focus on how strategies can interact. Another important implication of concerns policy-making. When systems are in transition, decision-makers should be cognizant of the impact governance has on journalists’ safety, too. Since resources available for coping represent a pivotal point in our conceptual framework, decision-makers need to make sure such resources are provided.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Anne-Marie och Gustaf Anders Stiftelse för Mediaforskning.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See, for e.g., UNESCO, https://en.unesco.org/themes/safety-journalists/observatory?page=50; the Committee to Protect Journalists, https://cpj.org, or Reporters Without Borders, https://rsf.org/en.

2 Journalists’ safety can also be endangered as a result of routine organizational processes (Bergström Citation2015, 131) not specific to the journalistic profession, such as being in a car accident while executing work-related tasks. Such general work-related risks are not part of this paper’s scope.

References

- Adams, C. 2018. “They Go for Gender First”: The Nature and Effect of Sexist Abuse of Female Technology Journalists.” Journalism Practice 12 (7): 850–869.

- Alok, R.,S. Das,G. Agarwal,S. Tiwari,L. Salwahan, andR. Srivastava. 2014. “Problem-Focused Coping and Self-Efficacy as Correlates of Quality of Life and Severity of Fibromyalgia in Primary Fibromyalgia Patients.” Journal of Clinical Rheumatology 20 (6): 314–316. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000000130.

- Alonso-Tapia, J.,R. Rodríguez-Rey,H.Garrido-Hernansaiz,M. Ruiz, andC. Nieto. 2016. “Coping Assessment from the Perspective of the Person-Situation Interaction: Development and Validation of the Situated Coping Questionnaire for Adults (SCQA).” Psicothema 28 (4): 479–486. doi:10.7334/psicothema2016.19.

- American Psychological Association 2012. Building your resilience. https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience (Accessed 9 September 2020).

- Asal, V., M. Krain, A. Murdie, and B. Kennedy. 2018. “Killing the Messenger: Regime Type as a Determinant of Journalist Killing, 1992–2008.” Foreign Policy Analysis 14 (1): 24–43.

- Aven, T. 2011. “On Some Recent Definitions and Analysis Frameworks for Risk, Vulnerability, and Resilience.” Risk Analysis : An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis 31 (4): 515–522.

- Backholm, K., andK. Björkqvist. 2012. “Journalists’ Emotional Reactions after Working with the Jokela School Shooting Incident.” Media, War & Conflict 5 (2): 175–190. doi:10.1177/1750635212440914.

- Barbalet, J. M. 1985. “Power and Resistance.” The British Journal of Sociology 36 (4): 531–548.

- Bergström, J., R. Van Winsen, and E. Henriqson. 2015. “On the Rationale of Resilience in the Domain of Safety: A Literature Review.” Reliability Engineering & System Safety 141: 131–141.

- Beus, J. M., M. A. McCord, and D. Zohar. 2016. “Workplace Safety: A Review and Research Synthesis.” The British Journal of Sociology Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 6 (4): 352–381.

- Bjørnskov, C., and A. Freytag. 2016. “An Offer You Can’t Refuse: Murdering Journalists as an Enforcement Mechanism of Corrupt Deals.” Public Choice 167 (3-4): 221–243.

- Bourdieu, P. 1979. “Symbolic Power.” Critique of Anthropology 4 (13-14): 77–85.

- Brambila, J. A. 2018. “Reporting Dangerously in Mexico: Capital, Risks and Strategies among Journalists.” PhD thesis, University of Leeds.

- Brambila, J., and S. Hughes. 2019. “Violence against Journalists.” In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, edited by Vos, TP and F. Hanusch. Boston, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Bromley, M., and V. Slavtcheva-Petkova. 2018. Global Journalism: An Introduction. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave.

- Buchanan, M., and P. Keats. 2011. “Coping with Traumatic Stress in Journalism: A Critical Ethnographic Study.” International Journal of Psychology 46 (2): 127–135.

- Carlson, M., S. Robinson, and S. C. Lewis. 2021. “Digital Press Criticism: The Symbolic Dimensions of Donald Trump’s Assault on US Journalists as the “Enemy of the People.” Digital Journalism 9 (6): 737–754.

- Carlsson, U., and R. Pöyhtäri. 2017. “Words of Introduction.” In Carlsson, U. & Pöyhtäri, R. (Eds.) The Assault on Journalism: Building Knowledge to Protect Freedom of Expression. Sweden: Nordicom.

- Chalaby, J. K. 2000. “New Media, New Freedoms, New Threats.” Gazette 62 (1): 19–29.

- Chen, G. M., P. Pain, V. Y. Chen, M. Mekelburg, N. Springer, and F. Troger. 2020. “You Really Have to Have a Thick Skin”: A Cross Cultural Perspective on How Online Harassment Influences Female Journalists.” Journalism 21 (7): 877–895.

- Cueva Chacón, Lourdes M., and M. Saldaña. 2021. “Stronger and Safer Together: Motivations for and Challenges of (Trans) National Collaboration in Investigative Reporting in Latin America.” Digital Journalism 9 (2): 196–214. Published first online June 17

- De León Vázquez, Salvador, Alejandra Bravo Ponce, and E. Maritza Duarte Alcántara. 2018. “Entre Abrazos y Golpes… Estrategias Subpolíticas de Periodistas Mexicanos Frente al Riesgo.” [between Embrace and Strikes…. Mexican Journalists’ Subpolitical Strategies in the Face of Risk.].” Sur le Journalisme, about Journalism, Sobre Jornalismo 7 (1): 114–129.

- Díaz, N., and G. de Frutos. 2017. “Murders, Harassment and Disappearances. The Reality of Latin American Journalists in the XXI Century.” Revista Latina de Comunicación Social (1): 418–411. http://www.revistalatinacs.org/72. 434.

- Di Salvo, P. 2022. “We Have to Act like Our Devices Are Already Infected”: Investigative Journalists and Internet Surveillance.” Journalism Practice 16 (9): 1849–1866. ′

- Edmondson, A. 1999. “Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams.” Administrative Science Quarterly 44 (2): 350–383.

- Dworznik-Hoak, G. 2020. “Weathering the Storm: Occupational Stress in Journalists Who Covered Hurricane Harvey.” Journalism Studies 21 (1): 88–106.

- Feinstein, A., B. Audet, and E. Waknine. 2014. “Witnessing Images of Extreme Violence: A Psychological Study of Journalists in the Newsroom.” Journal of Royal Society of Medicine 5 (8): 1–7. DOI: 10.1177/2054270414533323.

- Feinstein, A. 2006. Journalists under Fire: The Psychological Hazards of Covering War. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Ferrier, M., and N. Garud-Patkar. 2018. “TrollBusters: Fighting Online Harassment of Women Journalists.” In Mediating Misogyny, 311–332. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Flores Morales, R., V. Reyes Pérez, and L. M. Reidl Martínez. 2012. “Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Mexican Journalists Covering the Drug War.” Suma Psicológica 19 (1): 7–17.

- Flores Morales, R., V. Reyes Pérez, and L. M. Reidl Martínez. 2014. “The Psychological Impact of the War against Drug-Trafficking on Mexican Journalists.” Revista Colombiana de Psicología 23 (1): 177–192.

- Folkman, S., and R. S. Lazarus. 1980. “An Analysis of Coping in a Middle-Aged Community Sample.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 21 (3): 219–239.

- Fox, J., C. Cruz, and J. Y. Lee. 2015. “Perpetuating Online Sexism Offline: Anonymity, Interactivity, and the Effects of Sexist Hashtags on Social Media.” Computers in Human Behavior 52: 436–442.

- Frazier, M. L., S. Fainshmidt, R. L. Klinger, A. Pezeshkan, and V. Vracheva. 2017. “Psychological Safety: A Meta‐Analytic Review and Extension.” Personnel Psychology 70 (1): 113–165.

- Garcés Prettel, M. E., andJ. Arroyave Cabrera. 2017. “Professional Autonomy and Security Risks for Journalists in Colombia.” Perfiles Latinoamericanos 25 (49): 35–53. doi:10.18504/pl2549-002-2017.

- Garcés-Prettel, M., J. Arroyave-Cabrera, and A. Baltar-Moreno. 2020. “Professional Autonomy and Structural Influences: Exploring How Homicides, Perceived Insecurity, Aggressions against Journalists, and Inequalities Affect Perceived Journalistic Autonomy in Colombia.” International Journal of Communication 14: 22.

- González Macías, R. A. 2021. “Mexican Journalism under Siege. The Impact of anti-Press Violence on Reporters, Newsrooms and Society.” Journalism Practice 15 (3): 308–328. doi:10.1080/17512786.2020.1729225.

- González de Bustamante, C., and J. E. Relly. 2021. Surviving Mexico: Resistance and Resilience among Journalists in the Twenty-First Century. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- González Macías, R. A., and V. H. Reyna García. 2019. “They Don’t Trust us; They Don’t Care If We’re Attacked’: Trust and Risk Perception in Mexican Journalism.” Communication & Society 32 (1): 147–160.

- Guerrero, M., and Márquez-Ramírez, M. (Eds.). 2014. Media Systems and Communication Policies in Latin America. New York: Palgrave.

- Hamada, B. I. 2022. “Determinants of Journalists’ Autonomy and Safety: Evidence from the Worlds of Journalism Study.” Journalism Practice 16 (8): 1715–1735.

- Hanitzsch, T. 2011. “Populist Disseminators, Detached Watchdogs, Critical Change Agents and Opportunist Facilitators: Professional Milieus, the Journalistic Field and Autonomy in 18 Countries.” International Communication Gazette 73 (6): 477–494.

- Hanusch, F., S. Banjac, and P. Maares. 2020. “The Power of Commercial Influences: How Lifestyle Journalists Experience Pressure from Advertising and Public Relations.” Journalism Practice 14 (9): 1029–1046.

- Hasan, M., and M. Wadud. 2020. “Re-Conceptualizing Safety of Journalists in Bangladesh.” Media and Communication 8 (1): 27–36.

- Haugaard, M. 2012. “Rethinking the Four Dimensions of Power: Domination and Empowerment.” Journal of Political Power 5 (1): 33–54.

- Hayes, K., and H. Silke. 2019. “Narrowing the Discourse? Growing Precarity in Freelance Journalism and Its Effect on the Construction of News Discourse.” Critical Discourse Studies 16 (3): 363–379.

- Henrichsen, J., M. Betz, and J. Lisosky. 2015. Building Digital Safety for Journalism: A Survey of Selected Issues. Paris: UNESCO.

- Henrichsen, J. R. 2020. “Breaking through the Ambivalence: Journalistic Responses to Information Security Technologies.” Digital Journalism 8 (3): 328–346.

- Heywood, A. 2015. Political Theory: An Introduction. 4th edition. London: Macmillan.

- Himmelstein, H., and E. P. Faithorn. 2002. “Eyewitness to Disaster: How Journalists Cope with the Psychological Stress Inherent in Reporting Traumatic Events.” Journalism Studies 3 (4): 537–555.

- Høiby, M. 2020. “Covering Mindanao: The Safety of Local vs. non-Local Journalists in the Field.” Journalism Practice 14 (1): 67–83.

- Høiby, M., and R. Ottosen. 2019. “Journalism under Pressure in Conflict Zones: A Study of Journalists and Editors in Seven Countries.” Media, War & Conflict 12 (1): 69–86.

- Hughes, S., and M. Márquez-Ramírez. 2017. “Examining the Practices That Mexican Journalists Employ to Reduce Risk in a Context of Violence.” International Journal of Communication 11 (23): 499–521.

- Hughes, S., and M. Márquez-Ramírez. 2018. “Local-Level Authoritarianism, Democratic Normative Aspirations, and Antipress Harassment: Predictors of Threats to Journalists in Mexico.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (4): 539–560.

- Hughes, Sallie, Claudia Mellado, Jesús Arroyave, José Luis Benitez, Arnold de Beer, Miguel Garcés, Katharina Lang, and Mireya Márquez-Ramírez. 2017. “Expanding Influences Research to Insecure Democracies: How Violence, Public Insecurity, Economic Inequality and Uneven Democratic Performance Shape Journalists’ Perceived Work Environments.” Journalism Studies 18 (5): 645–665.

- Hughes, S., and Y. Vorobyeva. 2021. “Explaining the Killing of Journalists in the Contemporary Era: The Importance of Hybrid Regimes and Subnational Variations.” Journalism 22 (8): 1873–1891.

- Hughes, S., L. Iesue, H. F. de Ortega Bárcenas, J. C. Sandoval, and J. C. Lozano. 2021. “Coping with Occupational Stress in Journalism: Professional Identities and Advocacy as Resources.” Journalism Studies 22 (8): 971–991.

- Idås, T., K. S. Orgeret, and K. Backholm. 2020. “# MeToo, Sexual Harassment and Coping Strategies in Norwegian.” Media and Communication 8 (1): 57–67.

- Iesue, Laura, Sallie Hughes, Sonia Virginia Moreira, and Monica Sousa. 2021. “Risk, Victimization, and Coping Strategies of Journalists in Mexico and Brazil.” Sur le Journalisme, about Journalism, Sobre Jornalismo 10 (1): 62–81. www.surlejournalisme.com/rev.

- Imbusch, P. 2016. “Lektion IX: Macht Und Herrschaft.” In H. Korte & B. Schäfers (Eds.), Einführung in Hauptbegriffe Der Soziologie. Einführungskurs Soziologie, 195–220. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Kahn, W. A. 1990. “Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work.” Academy of Management Journal 33 (4): 692–724.

- Kim, H. S. 2010. “Forces of Gatekeeping and Journalists’ Perceptions of Physical Danger in post-Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 87 (3-4): 484–500.

- Krøvel, R. 2017. “Violence against Indigenous Journalists in Colombia and Latin America.” In U. Carlsson & R. Pöyhtäri (Eds.), The Assault on Journalism. Building Knowledge to Protect Freedom of Expression, 191–203. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Larsen, A. G., Fadnes, I. & Krøvel, R. (Editors). 2021. Journalist Safety and Self-Censorship. London and New York: Routledge.

- Lazarus, R. S. 1990. “Theory-Based Stress Measurement.” Psychological Inquiry 1 (1): 3–13.

- Lazarus, R. S., and S. Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

- Levendusky, M., and N. Malhotra. 2016. “Does Media Coverage of Partisan Polarization Affect Political Attitudes?” Political Communication 33 (2): 283–301.

- Löfgren Nilsson, M., and H. Örnebring. 2016. “Journalism under Threat: Intimidation and Harassment of Swedish Journalists.” Journalism Practice 10 (7): 880–890.

- Lohner, J., and S. Banjac. 2017. “A Story Bigger than Your Life? The Safety Challenges of Journalists Reporting on Democratization Conflicts.” In U. Carlsson & R. Pöyhtäri (Eds.), The Assault on Journalism. Building Knowledge to Protect Freedom of Expression, 289–301. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Lukes, S. 1974/2005. Power: A Radical View. London: Macmillan.

- Marcesse, S. C. 2017. “The United Nations’ Role in Promoting the Safety of Journalists from 1945 to 2016.” In In: Carlsson, U. & Pöyhtäri, R. (Eds.) The Assault on Journalism: Building Knowledge to Protect Freedom of Expression. Sweden: Nordicom.

- Marino, C. B. 2013. Violence Against Journalists and Media Workers: Inter-American Standards and National Practices on Prevention, Protection and Prosecution of Perpetrators. Retrieved from http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/expression/docs/reports/2014_04_22_violence_web.pdf

- Matthews, J., and K. Onyemaobi. 2020. “Precarious Professionalism: Journalism and the Fragility of Professional Practice in the Global South.” Journalism Studies 21 (13): 1836–1851.

- Mesquita, B., L. Feldman Barrett, and E. R. Smith. 2010. The Mind in Context. New York: Guilford Press.

- Monteiro, S., and A. Marques Pinto. 2017. “Reporting Daily and Critical Events: Journalists’ Perceptions of Coping and Savouring Strategies, and of Organizational Support.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 26 (3): 468–480.

- Monteiro, S., A. Marques Pinto, and M. S. Roberto. 2016. “Job Demands, Coping, and Impacts of Occupational Stress among Journalists: A Systematic Review.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 25 (5): 751–772.

- Miller, K. S. 2021. “Hostility toward the Press: A Synthesis of Terms, Research, and Future Directions in Examining Harassment of Journalists.” Digital Journalism. Advance online publication.

- Newman, E., R. Simpson, and D. Handschuh. 2003. “Trauma Exposure and Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder among Photojournalists.” Visual Communication Quarterly 10 (1): 4–13.

- Novak, R. J., and S. Davidson. 2013. “Journalists Reporting on Hazardous Events: Constructing Protective Factors within the Professional Role.” Traumatology 19 (4): 313–322.

- Nyabuga, G. 2016. Supporting Safety of Journalists in Kenya: An Assessment Based on UNESCO's Journalists’ Safety Indicators. Paris, France: UNESCO Publishing.

- Obermaier, M., M. Hofbauer, and C. Reinemann. 2018. “Journalists as Targets of Hate Speech. How German Journalists Perceive the Consequences for Themselves and How They Cope with It.” Studies in Communication and Media 7 (4): 499–524.

- O’Donnell, P., and L. Zion. 2019. “Precarity in Media Work.” In M. Deuze & M. Prenger (eds.), Making Media: Production, Practices, and Professions, 223–234. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Osofsky, H. J., H. Holloway, and A. Pickett. 2005. “War Correspondents as Responders: Considerations for Training and Clinical Services.” Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes 68 (3): 283–293.

- Örnebring, H., and C. Möller. 2018. “In the Margins of Journalism. Gender and Livelihood among Local (Ex-)Journalists in Sweden.” Journalism Practice 12 (8): 1051–1060.

- Parker, K. N. 2015. "Aggression against Journalists: Understanding Occupational Intimidation of Journalists Using Comparisons with Sexual Harassment." diss., The University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma: USA.

- Popitz, H. 2017. Phenomena of Power: Authority, Domination, and Violence. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Post, S., and H. M. Kepplinger. 2019. “Coping with Audience Hostility. How Journalists’ Experiences of Audience Hostility Influence Their Editorial Decisions.” Journalism Studies 20 (16): 2422–2442.

- Preuß, M., F. Tetzlaff, and A. Zick. 2017. Hass im Arbeitsalltag Medienschaffender: “Publizieren wird zur Mutprobe”. Studie zur Wahrnehmung von und Erfahrungen mit Angriffen unter Journalist_innen, Expertise für den Mediendienst Integration. https://mediendienst-integration.de/fileadmin/Dateien/Studie-hatespeech.pdf

- Reich, Z., and T. Hanitzsch. 2013. “Determinants of Journalists’ Professional Autonomy: Individual and National Level Factors Matter More than Organizational Ones.” Mass Communication and Society 16 (1): 133–156.

- Relly, J. E., and C. González de Bustamante. 2017. “Global and Domestic Networks Advancing Prospects for Institutional and Social Change: The Collective Action Response to Violence against Journalists.” Journalism & Communication Monographs 19 (2): 84–152.

- Robinson, Alexandra M. 2018. “Let’s Talk about Stress: History of Stress Research.” Review of General Psychology 22 (3): 334–342.

- Seely, N. 2019. “Journalists and Mental Health: The Psychological Toll of Covering Everyday Trauma.” Newspaper Research Journal 40 (2): 239–259.

- Selva, M. 2020. Fighting Words: Journalism Under Assault in Central and Eastern Europe. Reuters Institute Report. Oxford, UK: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-01/MSelva-Journalism_Under_Assault_FINAL_0.pdf (Accessed 7/9/2022).

- Sjøvaag, H. 2013. “Journalistic Autonomy: Between Structure, Agency and Institution.” Nordicom Review 34 (s1): 155–166.

- Slavtcheva-Petkova, V. 2018. Russia’s Liberal Media: Handcuffed but Free. London/New York: Routledge.

- Stahel, L., and C. Schoen. 2020. “Female Journalists under Attack? Explaining Gender Differences in Reactions to Audiences’ Attacks.” New Media & Society 22 (10): 1849–1867.

- Steiner, L., and K. Chadha. 2022. “Introduction: Global Precarity’s Uneven Impacts on Journalism.” 1–11. In: Chadha, K., & Steiner, L. (Eds.). (2022). Newswork and Precarity. New York/London: Routledge.

- Stephan, W. G., O. Ybarra, and K. R. Morrison. 2009. “Intergroup Threat Theory.” In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination, 43–59. New York, Hove: Taylor & Francis.

- Sussman, L. 1991. “Dying (and Being Killed) on the Job: A Case Study of World Journalists, 1982-1989.” Journalism Quarterly, 68 (1-2): 195–199.

- Torsner, S. 2017. “Measuring Journalism Safety: Methodological Challenges.” In U. Carlsson & R. Pöyhtäri (Eds.), The Assault on Journalism: Building Knowledge to Protect Freedom of Expression, 129–138. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Tsui, L., and F. Lee. 2021. “How Journalists Understand the Threats and Opportunities of New Technologies: A Study of Security Mind-Sets and Its Implications for Press Freedom.” Journalism 22 (6): 1317–1339.

- Tumber, H. 2006. “The Fear of the Living Dangerously.” Journalists Who Report on Conflict. International Relations 20 (4): 439–451.

- Unaegbu, L. N. 2017. “Safety Concerns in the Nigerian Media.” In Carlsson, U. & Pöyhtäri, R. (Eds.) The Assault on Journalism: Building Knowledge to Protect Freedom of Expression, 171–184. Sweden: Nordicom.

- Van Dalen, A., and P. Van Aelst. 2014. “The Media as Political Agenda-Setters: Journalists’ Perceptions of Media Power in Eight West European Countries.” West European Politics 37 (1): 42–64.

- Waisbord, S. 2002. “Antipress Violence and the Crisis of the State.” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 7 (3): 90–109.

- Waisbord, S. 2020. “Mob Censorship: Online Harassment of US Journalists in Times of Digital Hate and Populism.” Digital Journalism 8 (8): 1030–1046.

- Weber, M. 1979. Wirtschaft Und Gesellschaft. Grundriss Der Verstehenden Soziologie. Mohr: Tübingen.

- Weidmann, A., F. Fehm, and T. Fydrich. 2008. “Covering the Tsunami Disaster: Subsequent Post‐Traumatic and Depressive Symptoms and Associated Social Factors.” Stress and Health 24 (2): 129–135.

- Weidmann, A., and J. Papsdorf. 2010. “Witnessing Trauma in the Newsroom: Posttraumatic Symptoms in Television Journalists Exposed to Violent News Clips.” The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 198 (4): 264–271.

- West, S. R. 2018. “Presidential Attacks on the Press.” Mo. L. Rev 83: 915.

- World Health Organisation n. d. Stress at the workplace. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/stressatwp/en/ (Accessed 9 September 2020).

- Workneh, T. W. 2022. “From State Repression to Fear of Non-State Actors: Examining Emerging Threats of Journalism Practice in Ethiopia.” Journalism Practice 16 (9): 1909–1926.

- Wright, K., M. Scott, and M. Bunce. 2020. “Soft Power, Hard News: How Journalists at State-Funded Transnational Media Legitimize Their Work.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 25 (4): 607–631.