Abstract

The current research investigated (a) if political identity predicts perceived truthfulness of and the intention to share partisan news, and (b) if a media literacy video that warns of misinformation (priming-video) mitigates the partisan bias by enhancing truth discernment. To evaluate if heightened salience of misinformation accounts for the effects of the media literacy intervention, we also tested if recalling prior exposure to misinformation (priming-question) would yield the same results as watching the literacy video does. Two web-based experiments were conducted in South Korea. In Study 1 (N = 384), both liberals and conservatives found politically congenial information more truthful and shareworthy. Although misinformation priming lowered perceived truthfulness and sharing intention of partisan news, such effects were greater for false, rather than true information, thereby improving truth discernment. Study 2 (N = 600) replicated Study 1 findings, except that the misinformation priming lowered perceived truthfulness and the sharing intention across the board, regardless of the veracity of information. Collectively, our findings demonstrate the robust operation of partisan bias in the processing and sharing of partisan news. Misinformation priming aided in the detection of falsehood, but it also induced distrust in reliable information, posing a challenge in fighting misinformation.

Harms of misinformation go well beyond ill-informed opinions and misperceptions. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, fake remedies and prevention measures abounded online, resulting in group infection and a poisoning outbreak (Forrest Citation2020). In this era of infodemic, media literacy education is often recommended as the last resort to fight misinformation. Underlying such a recommendation is the belief that by alerting news users to the prevalence and the dangers of misinformation, we may be able to alleviate, if not eliminate, fatal consequences of false information. Setting aside the potential risk of inadvertently blaming the victim (“You should’ve known better”), however, media literacy interventions might foster chronic and blind skepticism about the credibility of any information (Lee and Shin Citation2021). Furthermore, heightened awareness of misinformation might facilitate motivated use of the derogatory label, “fake news,” to delegitimize journalistic authority of news media and discredit information that contradicts one’s position (Egelhofer and Lecheler Citation2019).

Indeed, biased judgments of the veracity of information are well documented, notably in the form of both confirmation and disconfirmation bias (Taber, Cann, and Kucsova Citation2009; Taber and Lodge Citation2006). Motivated to bolster their own worldview, people tend to judge the information to be more truthful that confirms rather than disconfirms their beliefs. Even with COVID-19 information, the partisan division is evident in the public’s understanding of the pandemic and the news media’s reporting. 59% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents said the outbreak was a major threat to the health of the U.S. population, whereas only 33% of Republicans and Republican leaners reported the same (Tyson Citation2020). Likewise, 76% of Republicans and Republican leaners thought that news media were exaggerating the risks, with only 49% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents being in agreement (Jurkowitz and Mitchell Citation2020).

The current research aimed to examine (a) the extent to which confirmation bias accounts for individuals’ susceptibility to and sharing of partisan misinformation and (b) if exposure to a media literacy message that warns of misinformation mitigates the partisan bias by enhancing truth discernment. On the one hand, warning people of the perils and dangers of misinformation might have the effect of suppressing the partisan bias by encouraging people to make conscious efforts to accurately distinguish between truth from falsehood. However, heightened salience of misinformation might elevate the baseline suspicion, leading people to suspect even reliable information (i.e. deception default; Lee and Shin Citation2021). Alternatively, when primed with the notion of fake news, partisans might find it easier to discredit counter-attitudinal information by labeling it as such (i.e. fake news as a label, Egelhofer and Lecheler Citation2019), which would exacerbate the partisan bias. To evaluate these competing possibilities, two web-based experiments were conducted in South Korea. By replicating Study 1 with a separate sample, using different news topics and media literacy messages, Study 2 assessed the robustness of the Study 1 findings.

Partisan Bias in News Perception and Sharing

Reasoning can be motivated by one of the two distinct goals: accuracy vs. belief perseverance (Kunda Citation1990). While accuracy goals motivate people to seek out and scrutinize relevant evidence to arrive at the right conclusion, directional goals induce biased access to and evaluation of information to defend one’s existing beliefs and opinions. When individuals are motivated to maintain their views, evidence that confirms (vs. disconfirms) their current beliefs is more likely selected and accepted without due diligence. Although its robustness remains debatable, empirical findings support individuals’ preference for attitudinally congruent (vs. incongruent) evidence and heightened scrutiny in the processing of counter-attitudinal (vs. pro-attitudinal) information (Lord, Ross, and Lepper Citation1979; Taber, Cann, and Kucsova Citation2009; Taber and Lodge Citation2006). For gun control and affirmative action, for instance, even when repeatedly instructed to “set their feelings aside” and “rate arguments fairly (p.760),” people actively sought out attitude-congruent arguments and assessed their quality more favorably, while discounting and counterarguing attitude-incongruent evidence (Taber and Lodge Citation2006). Motivated processing explains the differential acceptance of corrective information as well. According to Walter and Tukachinsky's (Citation2020) meta-analysis, when one’s worldview is retracted by corrective information, people discount the correction and readily adopt attitudinally congruent, but factually incorrect information.

Among well-known predictors of motivated reasoning is political ideology or partisanship. Endorsement of political beliefs, rumors, or conspiracies readily occurs when people find them attitudinally congruent. In a post-election survey of Americans, respondents were more likely to believe negative rumors about the presidential candidate from the opposing (vs. their own) party (Weeks and Garrett Citation2014) and conservatives/Republicans were more likely than liberals/Democrats to hold the birther belief (i.e. Barack Obama was not born in the U.S.) (Pasek et al. Citation2015). Even in Uganda where partisan affiliation is considered relatively weak compared to established democracies, partisan bias was manifest in individuals’ evaluations of public health services and their attribution of unsatisfactory public services (Carlson Citation2016). Likewise, while South Korea has rather unstable party politics with high levels of public distrust in political parties, party identification was nonetheless found to bias individuals’ economic evaluations (Lee and Singer Citation2022) and affect their acceptance of partisan misinformation (Lee, Citation2020). Such a partisan divide was also evident in a recent national survey where 74% of liberals agreed that the Korean government effectively responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, with only 30% of conservatives reporting the same (Gallup Citation2022). Therefore, H1a-b were proposed to test if partisan identity biases individuals’ trust in partisan news in a controlled experiment.

H1a-b

Individuals rate partisan information to be more truthful that is congruent rather than incongruent with their political identity. That is, (a) liberals judge partisan news to be more truthful that is favorable (vs. unfavorable) to the liberal government, but (b) conservatives exhibit the opposite tendency.

As important, if not more, as truth judgment is social sharing of (mis)information. After all, it is the unprecedented speed and scale at which information spreads that caused the so-called infodemic. Among the key motivations behind social sharing of news, such as socializing and status-seeking (Lee and Ma Citation2012), is shaping public agenda (Bright Citation2016). By disseminating news that they find newsworthy within their social network, people enhance its visibility, and potentially, its influence (Singer Citation2014).

Similar to truth judgments, research suggests the operation of politically motivated partisan news sharing. A study of approximately 45,000 articles posted by over 12,000 users revealed a binomial distribution in political news shared on Facebook, indicating politically skewed news sharing. Such a tendency was more pronounced when politics was salient (e.g. during election) and among those with stronger political identity (An, Quercia, and Crowcroft Citation2014); conservatives (vs. liberals) shared more articles from fake news domains which produced most pro-Trump misinformation during the 2016 U.S. presidential election (Guess, Nagler, and Tucker Citation2019). Corrective information is no exception to selective sharing, as partisans preferred to share fact-checking information that was congruent with their partisanship (Shin and Thorson Citation2017).

Other than the defensive motivation, another explanation for partisan sharing concerns perceived truthfulness of information. Spreading what later turns out to be false news can hurt the sharer’s reputation, which cannot be easily remedied by sharing corrective information afterwards (Altay, Hacquin, and Mercier Citation2022). As such, when deciding what to share, people would naturally gauge its veracity, often by employing credibility indicators such as source credibility and fact checking results (Yaqub et al. Citation2020). If people ascribe higher levels of authenticity to messages that confirm, rather than violate, their expectancy (Lee, Citation2020), people might be more willing to share politically congruent (vs. incongruent) news, mostly because they genuinely perceive it to be more truthful and believable (Su, Liu, and McLeod Citation2019).

Still, perceived truthfulness may not be the only, or even the most influential, factor that guides individuals’ news sharing. For instance, when deciding whether or not to share information, people consider questions such as how interesting it is, how likely it is to stimulate conversation (Altay, Hacquin, and Mercier Citation2022; Bobkowski Citation2015), and how newsworthy it is in light of geographical and cultural proximity (Trilling, Tolochko, and Burscher Citation2017). In fact, Leeder (Citation2019) found that perceived believability of news negatively predicted college students’ intention to share it. Given the disconnect between what people believe is accurate and what they are willing to share on social media (Pennycook et al. Citation2021), we tested if people are more inclined to share politically congruent information and how perceived truthfulness of news is associated with the intention to share it on social media.

H2a-b

Individuals are more willing to share partisan news that is congruent rather than incongruent with their political identity. That is, (a) liberals are more willing to share partisan information favorable (vs. unfavorable) to the liberal government, whereas (b) conservatives exhibit the opposite tendency.

H3

Perceived truthfulness of partisan information positively predicts the intention to share it.

When Media Literacy Message Backfires

While partisan identity is often blamed for misguiding individuals’ truth judgments and spreading falsehood, media literacy, which refers to the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and create messages in various media (Aufderheide Citation1993), is as often invoked as a remedy to counter misinformation. Studies have investigated what specific approaches and strategies are more effective in inducing resistance to false information and/or minimizing its adverse effects. For instance, Guess et al. (Citation2020) provided people with specific “tips” (e.g. “Be skeptical of shocking headlines”) to identify problematic content and found that such intervention resulted in better discernment between reliable and false stories. Based on their analysis of cognitive biases conducive to the susceptibility to misinformation, Scheibenzuber, Hofer, and Nistor (Citation2021) developed an online course to educate students on the form and effects of fake news, focusing on framing research, which enhanced students’ ability to detect fake news. Going beyond truth judgments, inoculating participants against flawed argumentation techniques used in misinformation about climate change (e.g. false-balance, fake experts) mitigated the negative influence of misinformation on perceived consensus and policy support (Cook, Lewandowsky, and Ecker Citation2017).

There is no question that the specific content of literacy interventions matters. While the ability to discern valid (vs. unverified) information (i.e. information literacy) predicted how successfully people identified fake news, an advanced yet general understanding of news production and its social influence (i.e. news literacy) did not (Jones-Jang, Mortensen, and Liu Citation2021). Regardless of what specific strategies and skills are promoted, however, most literacy interventions have one thing in common: problematizing misinformation as an imminent threat to the society. Although raising the target audience’s awareness of the problem is a core component of any literacy intervention, it might incur some unintended consequences. In particular, the availability heuristic (Tversky and Kahneman Citation1973) posits that people infer the probability of events from “the ease of retrieval, or accessibility, of information from memory” (p.207). Given that the accessibility of particular information hinges on such factors as the recency and frequency of activation of construct as well as the vividness of events (Shrum Citation1996), exposure to a media literacy video that presents vivid examples of misinformation with its negative consequences would lead people to make higher estimates of misinformation. Heightened probability estimates of false information, or generalized skepticism about news (Lee and Shin Citation2021), then, would subsequently affect their evaluation of news they come across and the likelihood of sharing it.

Consistent with this conjecture, studies have documented how exposure to misinformation or public discourse about it escalates people’s distrust in news, and moreover, political systems. By exposing participants to elites’ tweets about either fake news or federal budget, van Duyn and Collier (Citation2019) found that those primed with fake news were less trusting of media and less accurate in identifying real news (i.e. false negatives). Similarly, a two-wave panel survey during the 2018 U.S. elections found that self-reported exposure to misinformation at Wave 1 elevated political cynicism at Wave 2 (Jones-Jang, Kim, and Kenski Citation2021). Directly germane to the current research, exposure to a general warning of misleading information on social media lowered perceived accuracy of true, as well as false headlines, indicating unintended spill-over effects (Clayton et al. Citation2020). Therefore, we predicted:

H4a-b

Participants who have watched a media literacy video that warns of misinformation (a) judge partisan news to be less truthful and (b) are less willing to share it, compared to those who have not.

If the hypothesized effects of a media literacy intervention indeed stem from the heightened accessibility of misinformation, simply priming people with misinformation should yield similar outcomes. Considering that the easier individuals retrieve relevant information from memory, the higher their estimates of the frequency and probability of the events (Tversky and Kahneman Citation1973; Shrum Citation1996), asking people to recall their prior exposure to misinformation might inflate their estimates of false news in social circulation and guide their subsequent judgments. For a direct test of potential priming effects, we included an additional condition where participants were asked how frequently they had seen fake news and examined how merely recalling one’s prior exposure alters participants’ evaluations of news and willingness to share it.

H5a-b

Participants who have been prompted to recall their past exposure to misinformation (a) judge partisan information less truthful and (b) are less willing to share it, compared to those who were not.

Heightened salience of misinformation, however, might also elevate the motivation to authenticate it. While acknowledging the operation of politically motivated reasoning, Pennycook and his colleagues (Bago, Rand, and Pennycook Citation2020; Pennycook and Rand Citation2019, Citation2021) proposed inattention and a lack of reasoning as major culprits that explain why people fall for misinformation. After reviewing the literature, Pennycook and Rand (Citation2021) conclude that it is the degree of reasoning, rather than political concordance, that affects truth discernment. Although people are more likely to believe politically concordant rather than discordant news, they are also better able to distinguish truth from falsity when dealing with politically concordant news, suggesting that the willingness to engage in careful message processing is a key to truth discernment. If alerting participants to the prevalence of misinformation heightens their motivation to authenticate information, then greater scrutiny might improve truth discernment. Moreover, just as shifting participants’ attention to accuracy by having them rate the accuracy of a news headline discouraged them from spreading misinformation, but not true information (Pennycook et al. Citation2021), misinformation priming might do the same. In testing these possibilities, we varied the veracity of partisan information to avoid the confound between distrust and judgment accuracy – if we only examine partisans’ assessments of false information, lower trust can also mean higher accuracy. By measuring individuals’ reactions to true and false information separately, we aimed to examine how misinformation priming affects false positives (trusting misinformation) and false negatives (rejecting reliable information), respectively.

RQ1a-b

Does (a) watching a media literacy video or (b) recalling their prior exposure to fake news help people discern between truth and falsehood?

RQ2a-b

Does (a) watching a media literacy video or (b) recalling their prior exposure to fake news make people less willing to share false, but not true, information?

Lastly, priming with misinformation might moderate the partisan bias. First, considering that the term ‘fake news’ is often arbitrarily invoked to delegitimize journalistic authority of hostile news media (Egelhofer and Lecheler Citation2019), the propensity to undermine belief-challenging information by calling it “fake news” might become stronger when the construct is “at the top of one’s memory” (van Duyn and Collier Citation2019, p.31); that is, partisan bias might be amplified in the priming conditions, as people can retrieve the notion of misinformation with greater ease. However, if biased assessment of information à la motivated reasoning is a deliberate cognitive process to defend one’s existing beliefs (Ditto et al. Citation2019, Taber, Cann, and Kucsova Citation2009; Taber and Lodge Citation2006), heightened accessibility of misinformation may not alter its operation. After all, the availability/accessibility heuristic is less likely to affect subsequent judgments when people engage in systematic processing (Shrum Citation2001). Yet another possibility is that priming might heighten the accuracy motivation. Considering that 65% of Korean respondents expressed concerns about the authenticity of information they find on the Internet (Korea Press Foundation Citation2021), a general warning of misinformation that resonates with their reality perception might activate the danger control process (Witte Citation1994), leading participants to process incoming information more critically. In such a case, partisan bias in the processing and sharing of information would lessen. Indeed, studies have reported that news media literacy messages can mitigate the partisan bias in terms of hostile media perceptions (Vraga and Tully Citation2015) and selective exposure, albeit contingent on factors such as party affiliation (Vraga and Tully Citation2019) and issue stance (van der Meer and Hameleers Citation2021). Given these competing theoretical possibilities, we asked:

RQ3a-b

How does watching a media literacy video that warns of misinformation moderate the extent to which partisan bias affects (a) perceived truthfulness of and (b) their intention to share partisan information?

RQ4a-b

How does recalling their prior exposure to misinformation moderate the extent to which partisan bias affects (a) perceived truthfulness of and (b) their intention to share partisan information?

Study 1

Method

Participants

384 participants (192 men; age M = 39.41, SD = 11.14) were recruited by a survey company in South Korea. Email invitations were sent to its national panel and participants were allowed to join the study until the predesignated quota was filled: gender (50% men, 50% women), age (25% each in their 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s), and political identity (50% liberals, 50% conservatives). They were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions: priming-video (i.e. watching a 3-minute media literacy video about “fake news”), priming-question (i.e. recalling prior “fake news” exposure), or no-priming control condition. Regarding the highest degree earned, 257 respondents indicated college (66.9%), 83 high school (21.6%), and 44 postgraduate school (11.5%).

Procedure

Upon accessing the study website, participants indicated gender, age, and political identity (1 = very conservative, 5 = very liberal). Self-identified moderates could not proceed, while the others were dichotomized (1 or 2 = conservatives, 4 or 5 = liberals). Participants in the priming-video condition then watched a 3-minute video that highlighted the challenges of discerning truth from falsehood and the importance of critical processing of media messages to combat misinformation (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xiWOAWFcjPs; see Appendix A for the entire script). Those in the priming-question condition were asked if they had seen or heard “fake news,” and if so, through which channel. They then read ten news articles, presented in random order. The control condition read the identical messages, but without watching a video or answering questions about fake news. After reading each article, they assessed its truthfulness and indicated their willingness to share it.

Construction of Stimuli

The news articles were retrieved from the SNU FactCheck (https://factcheck.snu.ac.kr), a leading fact-checking platform in South Korea. We collected ten articles concerning how the government responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, which were either verified or falsified. Five were favorable to the government and the other five were unfavorable. Among them, four contained verified information and six reported falsified information (see Appendix B).

A pilot study tested if the news slant was perceived as intended (N = 62, 33 men; age M = 37.44, SD = 10.46). Self-identified moderates were recruited and indicated their agreement with the following statements: (a) “this article is very unfavorable (1) or very favorable (7) to the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic” and (b) “this article is very negative (1) or very positive (7) about the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.” Scores were averaged, all rs(60) > .84, all ps < .01. A series of paired-samples t-tests confirmed that participants perceived each anti-government article to be more critical of the government’s responses to the pandemic (2.60 < Ms < 3.35), compared with any of the pro-government articles (3.98 < Ms < 5.43), all ts < −2.49, all ps < .05.

Measures

For perceived truthfulness of news, participants rated how accurate (1 = not accurate at all, 7 = very accurate) and believable (1 = not believable at all, 7 = very believable) each news article was (adapted from Appelman and Sundar Citation2016). Scores were averaged between the two, rs(382) > .91, ps < .001, and across news articles within each news category (i.e. false anti-government, true anti-government, false pro-government, true pro-government; see Appendix C). Intention to share news was measured by asking how willing they were to share the news on social media (1 = not at all willing, 7 = very much willing; Lee and Ma Citation2012). Scores were averaged across the articles within each news category. Lastly, for prior exposure to fake news, participants were asked (a) if they had heard of “fake news,” (yes = 93.6%) (b) whether they had ever personally encountered fake news (yes = 56.8%), and if so, (c) through which channels (news aggregator sites or SNSs: 76.3%, mainstream news media, such as newspaper or TV: 9.5%, friends or acquaintances: 7.6%, school or workplace: 4.4%, other: 2.2%). They were then asked to estimate (d) what percentage of news they consume everyday they would consider to be false (M = 25.64%, SD = 17.51). For the priming-question condition, these questions were asked before participants evaluated the news articles, whereas those in the other two conditions answered after they assessed news articles.

Results

Hypothesis Tests

Perceived Truthfulness

To examine how (a) participants’ political identity (H1a-b) and (b) watching a media literacy video (H4a) or recalling prior exposure to misinformation (H5a) affect perceived truthfulness of partisan information, independently and jointly with the veracity of information (RQ1a-b, RQ3a, RQ4a), a 3 (experimental condition: priming-video vs. priming-question vs. control) x 2 (political identity: conservative vs. liberal) x 2 (news stance: pro- vs. anti-government) x 2 (veracity of information: true vs. false) mixed ANOVA was performed on perceived truthfulness, with the last two as within-subjects factors.

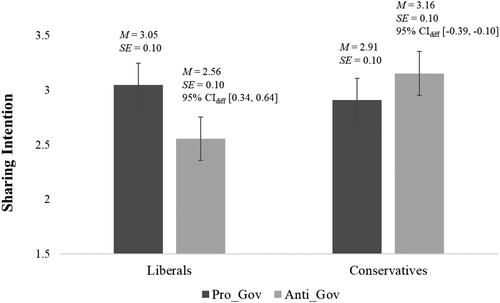

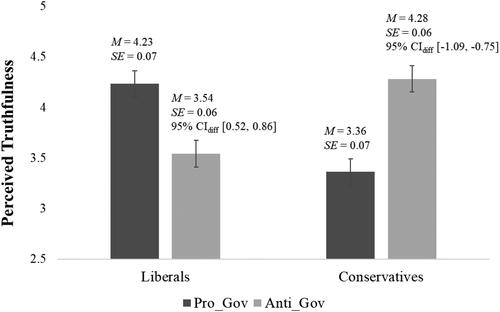

H1a predicted that liberals would rate pro-government (vs. anti-government) information to be more truthful, while H1b predicted the opposite for conservatives. A significant interaction confirmed that whereas liberals found pro-government news to be more truthful than anti-government news, conservatives judged anti-government news to be more truthful than pro-government news, F(1, 378) = 75.48, p < .001, ηp2 = .17 (see ). Therefore, both H1a and H1b were supported.

Figure 1. Interaction between political identity and news stance on perceived truthfulness of news (Study 1).

Consistent with H4a and H5a, there was a significant main effect of the experimental condition, F(2, 378) = 16.03, p < .001, ηp2 = .08. Those who watched a media literacy video (H4a; M = 3.99, SE =.07) or answered questions about prior exposure to fake news (H5a; M = 4.00, SE = .07) judged partisan information as significantly less truthful than those who did neither (M = 4.48, SE = .07), 95% CIdiff [-0.68, −0.30], p < .001, and 95% CIdiff [-0.68, −0.29], p < .001, respectively. There was virtually no difference between the priming-video condition and the priming-question condition in perceived truthfulness of information, p = .94.

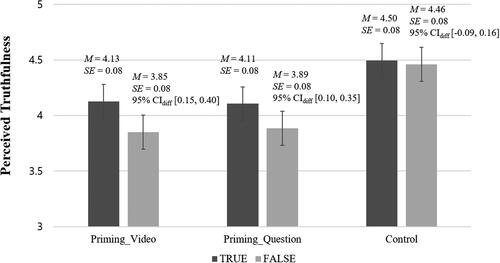

RQ1a-b addressed whether watching a video about fake news or recalling past exposure enhances truth discernment (see ). There was a significant interaction between the veracity of information and experimental condition, F(2, 378) = 4.04, p = .02, ηp2 = .02. Although the control condition did not perceive verified information to be any more truthful than falsified information, those in the priming-video condition and those in the priming-question condition rated true information as more truthful than false information. The significant main effect of actual veracity, with verified information (M = 4.24, SE = .04) being rated as more truthful than falsified information (M = 4.07, SE = .05), F(1, 378) = 23.63, p < .001, ηp2 = .06, should be interpreted in light of this interaction. Alternatively, misinformation priming, either via media literacy video or the prior exposure question, lowered perceived truthfulness of both truthful and false information, but such effects were more pronounced for false information (Mdiff = −.61, SE =.11, 95% CIdiff [-0.83, −0.40], p < .001 for priming-video vs. control; Mdiff = −.58, SE =.11, 95% CIdiff [-0.79, −0.36], p < .001 for priming-question vs. control), as compared to truthful information (Mdif = −.37, SE =.11, 95% CIdiff [-0.58, −0.16], p < .001 for priming-video vs. control; Mdiff = −.39, SE =.11, 95% CIdiff [-0.60, −0.18], p < .001 for priming-question vs. control).

Figure 2. Interaction between experimental condition and veracity of news on perceived truthfulness of news (Study 1).

Lastly, RQ3a and RQ4a addressed if the fake news prime would moderate the partisan bias in truth judgment. There was no significant omnibus interaction among political identity, news stance, and experimental condition, F(2, 378) = 1.54, p = .22. When the comparison was made between the priming-video and the control condition only (RQ3a), the three-way interaction was not significant, F(1, 252) = 1.15, p = .29. Neither was the three-way interaction involving the priming-question and the control condition (RQ4a), F(1, 252) = 0.51, p = .48.

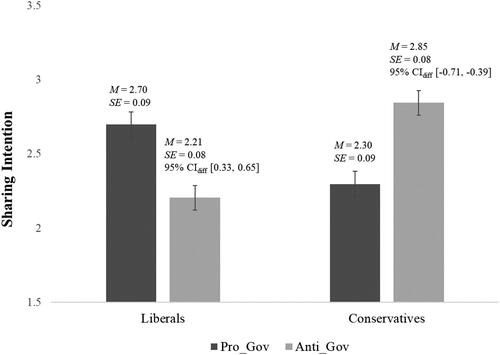

Sharing Intention

A 3 (experimental condition) x 2 (political identity) x 2 (news stance) x 2 (veracity of information) mixed ANOVA was conducted on the willingness to share the news, with the last two as within-subjects factors. Pertaining to H2a-b, which predicted that partisans would be more inclined to share politically concordant (vs. discordant) information, a significant two-way interaction emerged between news stance and political identity, F(1, 378) = 47.42, p < .001, ηp2 = .11 (see ). Liberals were more willing to share pro-government than anti-government news, whereas the opposite was true for conservatives. Therefore, both H2a and H2b were supported.

H3 predicted that perceived truthfulness of information would be positively associated with the sharing intention. Bivariate correlations were positive and statistically significant across all messages, supporting H3 (.45 < all rs < .63, ps < .001).

H4b and H5b each predicted that watching a media literacy video or recalling fake news exposure would lower the intention to share partisan news. Supporting both H4b and H5b, the intention to share partisan news significantly varied across experimental conditions, F(2, 378) = 14.30, p < .001, ηp2 = .07. Compared to the control condition (M = 3.41, SE = .12), the priming-video (M = 2.73, SE = .12) and the priming-question condition (M = 2.61, SE = .12) were less willing to share the information on social media, 95% CIdiff [-1.01, −0.37], p <. 001 and 95% CIdiff [-1.12, −0.48], p <. 001.

RQ2a-b addressed if misinformation priming would lead participants to share partisan information more discreetly, preferring verified rather than falsified information. The two-way interaction between experimental condition and the veracity of information was not significant, F(2, 378) = 1.13, p = .32.

Lastly, RQ3b and RQ4b concerned if misinformation priming would moderate partisan sharing. A three-way interaction between political identity, news stance, and experimental condition was not significant, F(2, 378) = 1.38, p = .25. Neither the three-way interaction involving the priming-video and the control conditions (RQ3a), F(1, 252) = 2.13, p = .15, nor the one involving the priming-question and the control condition (RQ4a), F(1, 252) = 0.002, p = .97, was statistically significant.

Discussion

Study 1 investigated if partisanship-based confirmation bias manifests itself in (a) perceived truthfulness of and (b) the intention to share partisan news. In so doing, we tested if heightened salience of misinformation, either as a result of watching a media literacy video or recalling prior experience with fake news, leads to different responses to partisan information, independently and/or jointly with the veracity of information. Overall, both conservatives and liberals judged COVID-19 news that confirmed their political identity to be more truthful and shareworthy. When primed with misinformation, they became more suspicious about information at hand and were less willing to share it with others, but such a tendency was more pronounced for false (vs. true) information. Consequently, participants were better able to discern between truth and falsehood, when alerted to or reminded of the prevalence of misinformation. These results are consistent with Guess et al.'s (Citation2020) findings that although exposure to some tips on how to spot fake news reduced people’s belief in both mainstream and false news headlines, it widened the gap in perceived accuracy (i.e. better discernment) between the two.

Although Study 1 confirmed the operation of partisan bias and uncovered priming effects, it employed a single media literacy video. Also, the news topic was limited to the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, to assess the robustness of the findings, Study 2 was conducted using two different media literacy videos and a range of news topics beyond COVID-19. In addition, the sample size was increased (600 vs. 384) to enhance statistical power.

Study 2

Method

Participants

600 participants (300 men, age M = 44.39, SD = 13.74) were recruited through the same survey company according to the predesignated quota in terms of gender, age, and political identity, as in Study 1. They were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions – priming-video, priming-question, or no-priming control condition. For the highest degree earned, 425 respondents indicated college (70.8%), 89 postgraduate school (14.8%), and 86 high school (14.3%).

Procedure & Stimuli

The study procedure and the measures were identical to those of Study 1, except that those in the priming-video condition watched one of the two 2.5 min video clips randomly assigned to them, which emphasized the harms of fake news and the importance of media literacy (see Appendix A for the script; Appendix E for descriptive statistics). For the prior exposure to fake news, 90.8% had heard of “fake news,” while 65.8% had personally encountered fake news (on news aggregator sites or SNSs: 53.5%, from friends or acquaintances: 5.2%, from mainstream news media: 3.5%, at school or workplace: 2.7%). On average, they estimated 31.92% of their daily news feed was false (SD = 19.62).

For news articles, we retrieved 12 articles from the same fact-checking platform used in Study 1. A pilot study with politically moderate participants (N = 175, 89 men; age M = 44.19, SD = 13.81) tested if the news slant was perceived as intended. Eight articles were selected crossing the news stance and the veracity of news (two anti-government/true, two pro-government/true, two anti-government/false, two pro-government/false; see Appendix D). Paired-samples t-tests confirmed that participants found each anti-government article more unfavorable to the government (2.93 < Ms < 3.03), compared to any of the four pro-government articles (4.47 < Ms < 4.97), all ts(174) < −8.77, all ps < .001.

Results

Hypothesis Tests

Perceived Truthfulness

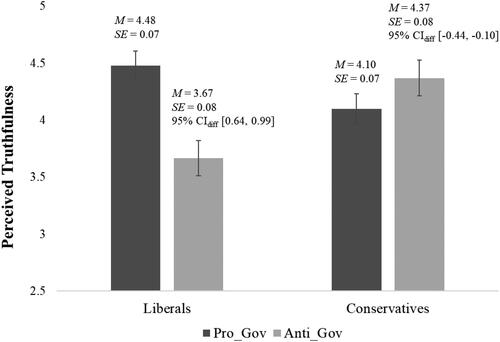

Replicating Study 1, a 3 (experimental condition) x 2 (political identity) x 2 (news stance) x 2 (veracity of information) mixed ANOVA yielded a significant interaction between political identity and news stance, F(1, 594) = 179.27, p < .001, ηp2 = .23 (see ). While liberals found pro-government (vs. anti-government) news more truthful, conservative exhibited the opposite tendency. Thus, both H1a and H1b were supported.

Figure 4. Interaction between political identity and news stance on perceived truthfulness of news (Study 2).

Supporting H4a and H5a, those who watched a media literacy video (H4a; M = 3.70, SE =.06) or recalled their prior exposure to fake news (H5a; M = 3.73, SE = .06) rated partisan news as less truthful than the control condition did (M = 4.13, SE = .06), 95% CIdiff [-0.60, −0.26], p < .001, and 95% CIdiff [-0.57, −0.23], p < .001, respectively.

RQ1a-b concerned if misinformation priming, either by watching a literacy video about fake news (RQ1a) or recalling past exposure (RQ1b) improves truth discernment. Unlike Study 1, the interaction between the veracity of information and experimental condition was not significant, F(2, 594) = 0.78, p = .46.

RQ3a and RQ4a tested if misinformation priming moderates the extent of partisan bias in truth judgments. The interaction between political identity, news stance, and experimental condition was not significant, whether the comparison was between the priming-video and the control conditions (RQ3a), F(1, 396) = 0.18, p = .67, or between the priming-question and the control conditions (RQ4a), F(1, 396) = 0.50, p = .48.

Sharing Intention

H2a-b predicted that partisans would be more willing to share information that aligns with their political identity. A 3 (experimental condition) x 2 (political identity) x 2 (news stance) x 2 (veracity of information) mixed ANOVA yielded a significant political identity by news stance interaction, F(1, 594) = 82.86, p < .001, ηp2 = .12. While liberals were more inclined to share pro-government (vs. anti-government) news, the opposite was true for conservatives (see ). Therefore, H2a-b were supported.

H3 predicted positive associations between perceived truthfulness of news and sharing intention. Supporting H3, bivariate correlations were positive and significant for all messages, .56 < all rs < .64, ps < .001.

Consistent with H4b and H5b, both the priming-video (H4b; M = 2.38, SE =.09) and the priming-question conditions (H5b; M = 2.38, SE = .09) were less willing to share information than the control condition was (M = 2.77, SE = .09), 95% CIdiff [-0.65, −0.14], p = .002, and 95% CIdiff [-0.65, −0.14], p = .002, respectively.

Lastly, RQ2a-b tested whether misinformation priming fosters more discreet sharing, but the interaction between experimental condition and the veracity of information was not significant, F(2, 594) = 0.49, p = .61. Similarly, RQ3b and RQ4b addressed if misinformation priming moderates the extent of partisan sharing. A three-way interaction between political identity, news stance, and experimental condition was not significant whether the comparison was made between the priming-video and the control conditions (RQ3b), F(1,396) = 0.06, p = .80 or between the priming-question and the control conditions (RQ4b), F(1, 396) = 0.03, p = .87.

Discussion

Replicating Study 1, confirmation bias was evident in (a) perceived truthfulness of and (b) the intention to share partisan news. Both liberals and conservatives were more likely to trust and share partisan news that comports well with their own view. Unlike Study 1, however, the fake news prime reduced participants’ trust in and intention to share partisan information, regardless of its veracity.

Albeit speculative, one explanation for the discrepancy concerns the plausibility of sampled news articles. For both studies, we sampled fact-checked information with a clear verdict (true vs. false) from a leading fact-checking platform, but not all verified/falsified information is equally plausible/dubious. In fact, additional analyses revealed that those in the control group in Study 1 rated the news articles to be more truthful than those in Study 2, whether they were falsified (4.46 vs. 4.13) or verified (4.40 vs. 4.14), both ts > 3.20, ps < .002. If verified news articles used in Study 2 were not considered plausible to begin with, heightened salience of misinformation was unlikely to elevate its truthiness.

Relatedly, while 56.8% of participants reported having seen or heard fake news in Study 1, 65.8% indicated as such in Study 2. If participants based their truth judgments, at least partly, on personal experiences, the baseline skepticism would have been higher among Study 2 participants than their Study 1 counterparts, which might account for the lower truthfulness ratings mentioned above. If so, the misinformation prime could have been particularly effective in lowering overall trust in news, due to its resonance with the participants’ reality perception.

General Discussion

Theoretical and Practical Implications

Replicating earlier studies that demonstrated the confirmation bias (Lord, Ross, and Lepper Citation1979; Taber and Lodge Citation2006), preference for politically concordant (vs. discordant) information was found for both liberals and conservatives alike. On the one hand, our findings that heightened salience of misinformation did not mitigate the partisan bias support the motivated reasoning account; that is, partisans seem to deliberately discredit counter-attitudinal information to preserve their existing beliefs. At the same time, a rival explanation cannot be ruled out that partisan bias emerged as a function of prior beliefs (Tappin, Pennycook, and Rand Citation2020a; Tappin, Pennycook, and Rand Citation2020b). Partisanship is frequently associated with divergent beliefs about a wide range of social issues, which affect how they process incoming information and update their worldviews. Considering that what conforms to existing knowledge and beliefs is processed more easily (i.e. processing fluency) and judged more favorably (Marsh and Yang Citation2018), the partisan bias observed herein may not necessarily reflect partisans’ conscious efforts to preserve their partisan beliefs, but occurs because “belief-confirming information feels just right” (Lee, Citation2020, p.63). Although it is challenging to empirically tease out the motivational and cognitive accounts, future research should compare relative contributions of political identity and prior beliefs to partisan bias in truth judgments, for example, by measuring individuals’ factual beliefs about the focal topic prior to the exposure to misinformation.

Thus far, media literacy education has been frequently invoked as an effective means to combat mis/disinformation. No matter what specific strategies and skills particular media literacy interventions promote, they all do one thing in common: problematizing misinformation. Extending previous research on the effectiveness of specific approaches (e.g. Cook, Lewandowsky, and Ecker Citation2017; Clayton et al. Citation2020; Guess et al. Citation2020), we tested how heightened accessibility of misinformation might moderate (a) the extent to which partisans engage in biased processing and sharing of news and (b) the likelihood that they fall for misinformation. Both studies found that partisan bias in truth judgments and information sharing is fairly robust, such that priming with misinformation failed to suppress it. One explanation for the null effect concerns the specific content of the media literacy videos. To assess the priming effect, we employed messages focusing mostly on the threats of misinformation with minimal additional content, but “general warning messages and forewarnings of misinformation…may be less effective than specific corrective responses” (Vraga, Bode, and Tully Citation2022, p.258). Had the literacy messages been tailored on message recipients’ characteristics (van der Meer and Hameleers Citation2021) or highlighted other aspects of news literacy education, like individual biases and citizen responsibilities (Vraga and Tully Citation2019), results might have been different.

As for the susceptibility to false information, while exposure to a short media literacy video reduced the likelihood of falling for misinformation, it also lowered their trust in reliable information. Consistent with the previous findings (Clayton et al. Citation2020; Guess et al. Citation2020), being warned against misinformation led individuals to question any information they come across (Lee and Shin Citation2021). Although Study 1 found that priming-induced suspicion was greater for falsified than verified information, no corresponding difference was observed in Study 2. Considering that blanket skepticism is no less problematic than naïve trust in this increasingly complex information environment (Acerbi, Altay, and Mercier Citation2022), these findings urge communication researchers to develop theory-grounded media literacy messages that reduce both false negatives and false positives.

Regarding selective sharing, both liberals and conservatives were more willing to spread politically congenial (vs. uncongenial) information. However, those primed with misinformation were less willing to share partisan news regardless of its stance, presumably due to heightened salience of the risks associated with sharing what might turn out to be false later. Similar to the “read before you retweet” campaign designed to “stop some of the knee-jerk reactions that can make misinformation viral” (Vincent Citation2020), simply alerting people to the pervasiveness of misinformation may keep people from unwittingly spreading inaccurate, misleading information.

To examine if mere salience of misinformation alters individuals’ assessments of information, we asked about participants’ previous encounter with fake news. In both studies, simply recalling one’s past exposure to misinformation yielded the same results as watching a media literacy video. These findings suggest that the effects of the media literacy intervention stem largely from heightened accessibility of misinformation. Interestingly, those who estimated the proportion of “fake news” in their daily news consumption prior to assessing individual news stories (priming-question) reported lower estimates (Study 1 M = 21.91, Study 2 M = 29.05) than those in the priming-video (Study 1 M = 28.19, Study 2 M = 33.05) or the control condition (Study 1 M = 27.20, Study 2 M = 33.66), who estimated the proportion of fake news after they had evaluated news articles. What deserves note is that watching the media literacy video did not increase the participants’ estimates of fake news beyond the control condition’s. Judging how truthful a given news story appears to have sufficiently raised the salience of misinformation in their mind, leaving little room for additional increases. As Shrum (Citation1996) put, “the more easily relevant instances of a particular construct come to mind, the higher are the estimates that subjects make” (p.486). Methodologically, such findings underscore the need to design the question order carefully.

Lastly, the choice of news articles might have contributed to the weak to null effect of misinformation priming on truth discernment. Although we selected only verified and falsified information by an established fact-checking platform, verified news was not rated as more truthful than falsified news by the control group, whose responses were not contaminated by the priming manipulation (4.46 vs. 4.50 in Study 1, 4.13 vs. 4.14 in Study 2). If it were fairly difficult to distinguish between truth and falsehood, simply raising the accuracy motivation could not improve judgment accuracy. To ensure generalizability of the findings and identify potential boundary conditions of priming effects, researchers should be more mindful in their selection of stimuli and employ a wide range of reliable and misleading messages.

Limitations & Directions for Future Research

In both experiments, the bivariate correlations between truth judgment and sharing intention were significant, but of moderate size. If perceived truthfulness is not the most important factor that determines individuals’ intention to share information (Bobkowski Citation2015; Trilling, Tolochko, and Burscher Citation2017), more systematic investigations are needed to identify what additional factors contribute to the virality of information.

Although both studies uncovered priming effects, such effects might dissipate over time. To evaluate their real-life implications, future research should investigate how long such effects last by employing follow-up measures. Moreover, it would be worthwhile to explore under what conditions priming elevates the accuracy motivation, and thereby systematic processing, which improves truth discernment (Bago, Rand, and Pennycook Citation2020; Pennycook and Rand Citation2019, Citation2021).

Lastly, our samples consisted of more highly educated individuals (78.4% holding college/post-graduate degrees in Study 1, 85.6% in Study 2), as compared to the national population, aged from 25 to 64 (51%). If the level of education is any indication of cognitive ability and/or motivation, perhaps the literacy intervention did not significantly affect truth discernment in Study 2, due to the overrepresentation of most educated individuals. Alternatively, one might consider it even more noteworthy that simple misinformation priming nonetheless altered the most educated individuals’ judgments and behavioral intention. Regardless, future research should investigate how news users’ characteristics, such as education and domain knowledge, interact with various attributes of literacy interventions.

In sum, the current research once again validated the robust operation of partisan bias in truth judgment as well as selective sharing. While research on misinformation tends to focus on “fighting misinformation,” as important, or even more important, is increasing the acceptance of reliable information (“fighting for information”), given the low base rate of online misinformation consumption (Acerbi, Altay, and Mercier Citation2022). If so, raising awareness of misinformation without plausible solutions could do more harm than good, as observed herein. Cultivating news users’ healthy skepticism without simultaneously fostering chronic distrust seems to be a daunting challenge we communication researchers are tasked with, which demands systematic, theory-grounded empirical investigations down the road.

supplemental_file_final.docx

Download MS Word (37 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acerbi, A., S. Altay, and H. Mercier. 2022. “Research Note: Fighting Misinformation or Fighting for Information?” Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 3 (1).

- Altay, S., A.-S. Hacquin, and H. Mercier. 2022. “Why Do so Few People Share Fake News? It Hurts Their Reputation.” New Media & Society 24 (6): 1303–1324.

- An, J., D. Quercia, and J. Crowcroft. 2014. Partisan Sharing: Facebook Evidence and Societal Consequences. Proceedings of the Second Edition of ACM conference on Online Social Networks, 13–24.

- Appelman, A., and S. Sundar. 2016. “Measuring Message Credibility: Construction and Validation of an Exclusive Scale.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 93 (1): 59–79.

- Aufderheide, P. 1993. Media Literacy: A Report of the National Leadership Conference on Media Literacy. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED365294.pdf

- Bago, B., D. G. Rand, and G. Pennycook. 2020. “Fake News, Fast and Slow: Deliberation Reduces Beliefs in False (but Not True) News Headlines.” Journal of Experimental Psychology. General 149 (8): 1608–1613.

- Bobkowski, P. S. 2015. “Sharing the News: Effects of Informational Utility and Opinion Leadership on Online News Sharing.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 92 (2): 320–345.

- Bright, J. 2016. “The Social News Gap: How News Reading and News Sharing Diverge.” Journal of Communication 66 (3): 343–365.

- Carlson, E. 2016. “Finding Partisanship Where we Least Expect It: Evidence of Partisan Bias in a New African Democracy.” Political Behavior 38 (1): 129–154.

- Clayton, K., S. Blair, J. A. Busam, S. Forstner, J. Glance, G. Green, A. Kawata, et al. 2020. “Real Solutions for Fake News? Measuring the Effectiveness of General Warnings and Fact-Check Tags in Reducing Belief in False Stories on Social Media.” Political Behavior 42 (4): 1073–1095.

- Cook, J., S. Lewandowsky, and U. K. H. Ecker. 2017. “Neutralizing Misinformation through Inoculation: Exposing Misleading Argumentation Techniques Reduces Their Influence.” Plos ONE 12 (5): e0175799.

- Ditto, P. H., B. S. Liu, C. J. Clark, S. P. Wojcik, E. E. Chen, R. H. Grady, J. B. Celniker, and J. F. Zinger. 2019. “At Least Bias is Bipartisan: A Meta-Analytic Comparison of Partisan Bias in Liberals and Conservatives.” Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science 14 (2): 273–291.

- Egelhofer, J. L., and S. Lecheler. 2019. “Fake News as a Two-Dimensional Phenomenon: A Framework and Research Agenda.” Annals of the International Communication Association 43 (2): 97–116.

- Forrest, A. 2020. Coronavirus: 700 Dead in Iran After Drinking Toxic Methanol Alcohol to ‘Cure COVID-19’. Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/coronavirus-iran-deaths-toxic-methanol-alcohol-fake-news-rumours-a9487801.html

- Gallup. 2022. Gallup Korea Daily Opinion Report, 479. https://www.gallup.co.kr/gallupdb/reportContent.asp?seqNo=1266

- Guess, A. M., M. Lerner, B. Lyons, J. M. Montgomery, B. Nyhan, J. Reifler, and N. Sircar. 2020. “A Digital Media Literacy Intervention Increases Discernment between Mainstream and False News in the United States and India.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117 (27): 15536–15545.

- Guess, A., J. Nagler, and J. Tucker. 2019. “Less than You Think: Prevalence and Predictors of Fake News Dissemination on Facebook.” Science Advances 5 (1).

- Jones-Jang, S. M., D. H. Kim, and K. Kenski. 2021. “Perceptions of Mis- or Disinformation Exposure Predict Political Cynicism: Evidence from a Two-Wave Survey during the 2018 U.S. Midterm Elections.” New Media & Society 23 (10): 3105–3125.

- Jones-Jang, S. M., T. Mortensen, and J. Liu. 2021. “Does Media Literacy Help Identification of Fake News? Information Literacy Helps, but Other Literacies Don’t.” American Behavioral Scientist 65 (2): 371–388.

- Jurkowitz, M., and A. Mitchell. 2020. “Fewer Americans Now Say Media Exaggerated COVID-19 Risks, But Big Partisan Gaps Persist.” Pew Research Center. https://www.journalism.org/2020/05/06/fewer-americans-now-say-media-exaggerated-covid-19-risks-but-big-partisan-gaps-persist/

- Korea Press Foundation. 2021. “Korea Ranked 38th Out of 46 Participating Countries in News Trust.” Media Issue 7. https://www.kpf.or.kr/synap/skin/doc.html?fn=1625731792833.pdf&rs=/synap/result/research/

- Kunda, Z. 1990. “The Case for Motivated Reasoning.” Psychological Bulletin 108 (3): 480–498.

- Lee, E.-J. 2020. “Authenticity Model of (Mass-Oriented) Computer-Mediated Communication: Conceptual Explorations and Testable Propositions.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 25 (1): 60–73.

- Lee, N. 2020. “Partisan Online Media Use, Political Misinformation, and Attitudes toward Partisan Issues.” The Social Science Journal. Advance online publication.1–14. doi: 10.1080/03623319.2020.1728508.

- Leeder, C. 2019. “How College Students Evaluate and Share “Fake News” Stories.” Library & Information Science Research 41 (3): 100967.

- Lee, C. S., and L. Ma. 2012. “News Sharing in Social Media: The Effect of Gratifications and Prior Experience.” Computers in Human Behavior 28 (2): 331–339.

- Lee, E.-J., and S. Shin. 2021. “Mediated Misinformation: Questions Answered, More Questions to Ask.” American Behavioral Scientist 65 (2): 259–276.

- Lee, H., and M. M. Singer. 2022. “The Partisan Origins of Economic Perceptions in a Weak Party System: Evidence from South Korea.” Political Behavior 44 (1): 341–364.

- Lord, C. G., L. Ross, and M. R. Lepper. 1979. “Biased Assimilation and Attitude Polarization: The Effects of Prior Theories on Subsequently Considered Evidence.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37 (11): 2098–2109.

- Marsh, E. J., and B. W. Yang. 2018. “Believing Things That Are Not True: A Cognitive Science Perspective on Misinformation.” In Misinformation and Mass Audiences, edited by B. G. Southwell, E. A. Thorson, and L. Sheble, 15–34. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Pasek, J., T. H. Stark, J. A. Krosnick, and T. Tompson. 2015. “What Motivates a Conspiracy Theory? Birther Beliefs, Partisanship, Liberal-Conservative Ideology, and anti-Black Attitudes.” Electoral Studies 40: 482–489.

- Pennycook, G., Z. Epstein, M. Mosleh, A. A. Arechar, D. Eckles, and D. G. Rand. 2021. “Shifting Attention to Accuracy Can Reduce Misinformation Online.” Nature 592 (7855): 590–595.

- Pennycook, G., and D. G. Rand. 2019. “Lazy, Not Biased: Susceptibility to Partisan Fake News is Better Explained by Lack of Reasoning than by Motivated Reasoning.” Cognition 188: 39–50.

- Pennycook, G., and D. G. Rand. 2021. “The Psychology of Fake News.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 25 (5): 388–402.

- Scheibenzuber, C., S. Hofer, and N. Nistor. 2021. “Designing for Fake News Literacy Training: A Problem-Based Undergraduate Online-Course.” Computers in Human Behavior 121: 106796.

- Shin, J., and K. Thorson. 2017. “Partisan Selective Sharing: The Biased Diffusion of Fact-Checking Messages on Social Media.” Journal of Communication 67 (2): 233–255.

- Shrum, L. J. 1996. “Psychological Processes Underlying Cultivation Effects: Further Tests of Construct Accessibility.” Human Communication Research 22 (4): 482–509.

- Shrum, L. J. 2001. “Processing Strategy Moderates the Cultivation Effect.” Human Communication Research 27 (1): 94–120.

- Singer, J. B. 2014. “User-Generated Visibility: Secondary Gatekeeping in a Shared Media Space.” New Media & Society 16 (1): 55–73.

- Su, M.-H., J. Liu, and D. M. McLeod. 2019. “Pathways to News Sharing: Issue Frame Perceptions and the Likelihood of Sharing.” Computers in Human Behavior 91: 201–210.

- Taber, C. S., D. Cann, and S. Kucsova. 2009. “The Motivated Processing of Political Arguments.” Political Behavior 31 (2): 137–155.

- Taber, C. S., and M. Lodge. 2006. “Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs.” American Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 755–769.

- Tappin, B. M., G. Pennycook, and D. G. Rand. 2020a. “Thinking Clearly about Causal Inferences of Politically Motivated Reasoning: Why Paradigmatic Study Designs Often Undermine Causal Inference.” Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 34: 81–87.

- Tappin, B. M., G. Pennycook, and D. G. Rand. 2020b. “Bayesian or Biased? Analytic Thinking and Political Belief Updating.” Cognition 204: 104375.

- Trilling, D., P. Tolochko, and B. Burscher. 2017. “From Newsworthiness to Shareworthiness: How to Predict News Sharing Based on Article Characteristics.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 94 (1): 38–60.

- Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman. 1973. “Availability: A Heuristic for Judging Frequency and Probability.” Cognitive Psychology 5 (2): 207–232.

- Tyson, A. 2020. “Republicans Remain Far Less Likely than Democrats to View COVID-19 as a Major Threat to Public Health.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/22/republicans-remain-far-less-likely-than-democrats-to-view-covid-19-as-a-major-threat-to-public-health/

- van der Meer, T. G. L. A., and M. Hameleers. 2021. “Fighting Biased News Diets: Using News Media Literacy Interventions to Stimulate Online Cross-Cutting Media Exposure Pattern.” New Media & Society 23 (11): 3156–3178.

- van Duyn, E., and J. Collier. 2019. “Priming and Fake News: The Effects of Elite Discourse on Evaluation of News Media.” Mass Communication and Society 22 (1): 29–48.

- Vincent, J. 2020. “Twitter Is Bringing its ‘Read Before You Retweet’ Prompt to All Users.” The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2020/9/25/21455635/twitter-read-before-you-tweet-article-prompt-rolling-out-globally-soon

- Vraga, E. K., L. Bode, and M. Tully. 2022. “Creating News Literacy Messages to Enhance Expert Corrections of Misinformation on Twitter.” Communication Research 49 (2): 245–267.

- Vraga, E. K., and M. Tully. 2015. “Media Literacy Messages and Hostile Media Perceptions: Processing of Nonpartisan versus Partisan Political Information.” Mass Communication and Society 18 (4): 422–448.

- Vraga, E. K., and M. Tully. 2019. “Engaging with the Other Side: Using News Media Literacy Messages to Reduce Selective Exposure and Avoidance.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 16 (1): 77–86.

- Walter, N., and R. Tukachinsky. 2020. “A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Continued Influence of Misinformation in the Face of Correction: How Powerful is It, Why Does It Happen, and How to Stop It?” Communication Research 47 (2): 155–177.

- Weeks, B. E., and K. R. Garrett. 2014. “Electoral Consequences of Political Rumors: Motivated Reasoning, Candidate Rumors, and Vote Choice during the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 26 (4): 401–422.

- Witte, K. 1994. “Fear Control and Danger Control: A Test of the Extended Parallel Process Model (EPPM).” Communication Monographs 61 (2): 113–134.

- Yaqub, W., O. Kakhidze, M. L. Brockman, N. Memon, and S. Patil. 2020. “Effects of Credibility Indicators on Social Media News Sharing Intent.” Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.